Abstract

Background:

Hypertension is a silent killer, a time bomb in both the developed and developing nations of the world. It is one of the most significant risk factors for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality resulting from target-organ damage to blood vessels in the heart, brain, kidney and eyes. Adherence to long-term therapy for chronic illnesses like hypertension is an important tool to enhance the effectiveness of pharmacotherapy.

Objective:

The two objectives of this study were to evaluate the extent and reasons of non-adherence in patients attended National Health Service (NHS) Hospital, Sunderland.

Materials and Methods:

The study was conducted for 4 months in the out-patient department of NHS Hospital. A total of 200 patients were selected randomly for this study. Morisky's Medication Adherence Scale was used to assess the adherence rate and the reason of non-adherence. Data were entered and analyzed using Microsoft Excel 2010.

Results:

The overall adherence rate was found to be 79% (n = 158). Adherence rate in females were low was compared with their male counterparts (74.7% vs. 85.7%). The higher rate of adherence was found in age group of 30-40 years (82%, n = 64). The major intentional and non-intentional reason of non-adherence was side-effects and forgetfulness respectively.

Conclusion:

Overall, more than three-fourth of the hypertensive participants were found to be adherent to their treatment. On the basis of factors associated with non-adherence, it is analyzed that suitable therapy must be designed for patients individually to increase medication adherence and its effectiveness.

KEY WORDS: Adherence, barriers, hypertension

Medication adherence is generally defined as the extent to which patient takes medication as prescribed by the medical practitioner.[1] Adherence depends on many factors as its prevalence has been shown by many studies in range from 0% to 100% respectively.[2,3] Non-adherence to prescribed medications has been a global problem as studies have shown that it has affected the most in patients with chronic illness such as diabetes and hypertension.[4,5] It is therefore an important issue which is directly linked with the management of chronic diseases as it has been established that the medication non-adherence lowers the treatment effectiveness and raises medication cost.[6] All stakeholders in healthcare system concerns the problem of non-adherence the most due to the scarcity of healthcare resource. The prevalence of non-adherence is affected by the choice of drug, use of concomitant medications, tolerability of drug and duration of drug treatment, which concludes from the analysis of multiple patient population.[7]

Hypertension is a devastating chronic disease which has affected patients from every part of the world and is rank third as a cause of disability adjusted life years.[8] Joint National Committee VII states that there are more than 1 billion hypertensive patients world-wide.[9] In Britain, however, prevalence of hypertension is 11.7% for ages; 14.4% for those aged more than 16 years; and 46% in those over 65 years of age.[10] Another study showed that age and sex-adjusted prevalence of hypertension was 28% in the North American countries and 44% in the European countries at the 140/90 mm Hg threshold.[11] In Asian country like Pakistan it was estimated that hypertension affects 18% of adults and 33% of adults above 45-year-old. In another report, it was shown that 18% of people in Pakistan suffer from hypertension with every third person over the age of 40 becoming increasingly vulnerable to a wide range of diseases.[12] With respect to gender, from 1999 to 2004, blood pressure control increased in men from 39% to 51% (P < 0.05) but did not change significantly in women (35-37%).[13] An important aspect in the treatment of hypertension is that patients who start with treatment should be prepared to take antihypertensive drugs for a life-long period. Imperfect execution of the dosing regimen or discontinuation of treatment because of, for example, side-effects of drugs will lead to a less effective treatment. Execution of the dosing regimen reflects the extent to which a patient takes his medication as prescribed and can be expressed by the term adherence or compliance.[14]

Medication non-adherence among hypertensive patients leads to severe consequences as it leads to poor controlled blood pressure, which increases the probability of cardiovascular (CV) problems.[15] Beta blockers and lipid lowering agents are most commonly prescribed drugs in hypertensive patient and it has been reported that low adherence to these agents increase the risk of death in hypertensive patients.[16] Similarly it has also been noted that the adherence rate of less than 75% with short acting anti-hypertensive drugs such as captopril and quinapril increases the risk of CV problems.

Many researchers have tried to explore the complex relationship of medication adherence and its responsible factors. It has been mentioned that the association of medication adherence and socio demographic factors such as age, gender, ethnicity, education is weak and inconsistent.[17] However, recent evidences have shown the phenomenon could be understand by the conceptual distinction of intentional and unintentional medication non-adherence.[18] Health care society of almost every country is affected by this problem and it is important to identify this problem in one's community and evaluate its risk factors so that necessary interventions could be made to counter this rapidly rising problem. The objectives of this study were to evaluate the extent of non-adherence to antihypertensive medications and the reasons of non-adherence in patient registered with National Health Service (NHS) Hospital, Sunderland.

Materials and Methods

Study design and site

A prospective cross-sectional study was conducted in a NHS Hospital Sunderland. It is a community hospital located at the central region of the city. This is an Acute Trust providing a wide range of hospital services such as A and E, surgical and medical specialties, therapy services, maternity and pediatric care.

Study participants

Patients aged between 18 and 60, who have been diagnosed hypertension and are on anti-hypertensive (at least one) for last 6 months are included in this study. Pregnancy induced hypertension patients were excluded from the study. Patients diagnosed with hypertension but of less than 6 months duration were also excluded. Patients taking other drugs along with anti-hypertensive were not included in this study. Furthermore excluded were hypertensive patients in an inpatient setting. Written consent was obtained prior to enroll participants in the study.

Sample size and sampling technique

The sample size was calculated as two by using Raosoft sample size calculator.[19] Convenience sampling technique was used to select participants. Respondents were selected daily by convenience sampling from the hypertensive patients who attended outpatient clinic at NHS hospital.

Study instrument

The data collection tool used was a questionnaire adapted from Morisky self - reported medication adherence questionnaire relating to medication use and major reasons for non-adherence. It is 4-item questionnaire with a high reliability and validity, which has been particularly useful in chronic conditions like hypertension. It measures both intentional and unintentional adherence based on forgetfulness, carelessness, stopping medication when feeling better and stopping medication when feeling worse. The scale is scored 1 point for each “no” and 0 points for each “yes”. The total score ranges from 0 (non-adherent) to 4 (adherent).[20]

Study duration

The study was conducted for 4 months on participants who consented to participate in the study. It is important to consider the rights of respondents in every research; therefore the rights of respondents during the interviews were well-respected.

Data analysis

In Morisky's medication adherence scale questionnaire, a NO answer was allocated a score of 1 while a YES answer was given a score of 0. Hence a score of 4 would designate patient as fully adherence while a score of 0 would tag him as fully non-adherent. Similarly, a score of 1, 2 and 3 would specify patient as 25%, 50% and 75% adherent respectively. Patients who score 75% or more were considered as adherent while those who score less than 75% were termed as non-adherent.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the institutional research Ethics Committee. Furthermore, written consent was obtained from the respondents prior to participation in the study.

Results

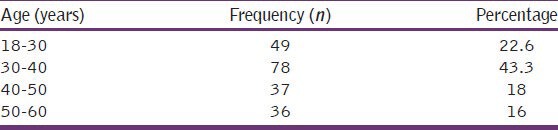

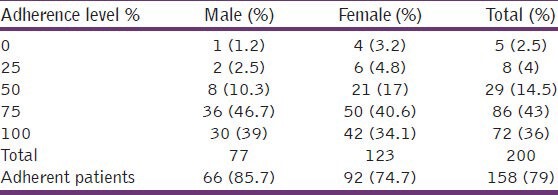

A total of 200 participants were included in this study. The age of majority of the participants were between 30 and 40 (n = 78, 43.3%) while only 36 participants (16%) belonged to the age group of 50-60 [Table 1]. The result also showed that majority of the participant were female (n = 123, 61.5). The overall adherence rate was found to be 79% (n = 158), however only 36% (n = 72) of participants were fully adhering to the prescribed medications. The results showed that women were higher in numbers but their adherence rate was low was compared to their male counterparts as only 74.7% (n = 92) females were complying with the physicians order, of which those of fully adhere to the medicines were only 34.1% (n = 42). Conversely, the rate of adherence among males were high (85.7%, n = 66) although those of completely adhere to antihypertensive medicines were moderate in numbers (39%, n = 30) as shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Age distribution of study participants

Table 2.

Estimation of Morisky's medication adherence scale by participants’ gender

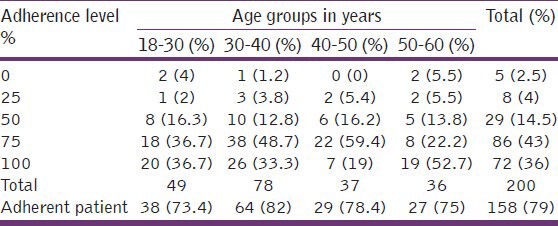

Moreover, when medication adherence was linked with age groups of participants it was revealed that majority of participants aged between 30 and 40 and this class of age also possesses the higher rate of adherence (82%, n = 64). The least adhered age group was 18-30 (73.4%, 38). Interestingly, it was noted that participant who showed 100% adherence were mainly the oldest ones (i.e. 50-60 years) where 52.7% of participants of that group were absolutely adherent. The age group where absolute adherence was minimum was 40-50 years (19%, n = 7) as mentioned in Table 3.

Table 3.

Estimation of Morisky's medication adherence scale by participants’ age

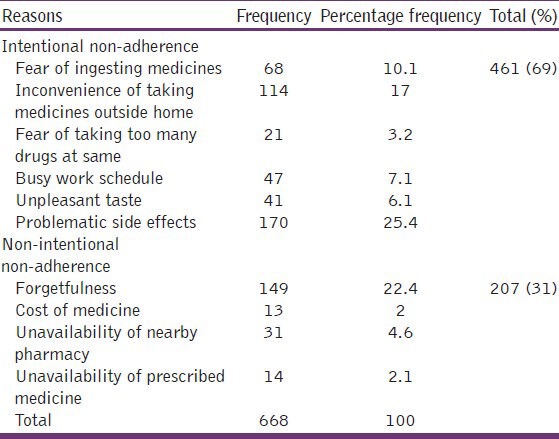

The summary of the reasons of non-adherence is shown in Table 4. The reasons were divided into intentional and non-intentional non-adherence. 69% (n = 461) reasons mentioned by the participants who did not adhere to anti-hypertensive medicines were from intentional non-adherence and the major reason was the fear of side-effects (25.4%, n = 170) followed by inconvenience of taking medicines outside home (17%, n = 114). The least affecting intentional reason was fear of taking too many drugs at the same time (3.2%, n = 21). Furthermore, unintentional reasons account for 31% (n = 207) of non-adherence among hypertensive patients. The non-intentional reason which is most frequently quoted by the patients was forgetfulness (22.4%, n = 149) while the reason which is least mentioned by the participants was cost of medicines (2%, n = 13).

Table 4.

Reason of non-adherence to anti-hypertensive medication

Discussion

Medication adherence is an important tool that can increase treatment effectiveness, however literature has shown that the rate of adherence in chronic disease like hypertension is very low and thus it is an important problem in the management of diseases which require long-term treatments.[21] The study revealed that the adherence rate is 79% with respect to antihypertensive treatment. It is higher than the medication adherence to antihypertensive medications reported in Egypt (74.1%), Malaysia (44.2%), Gambia (27%), Pakistan (57%) and Korea (61.1%) respectively.[22,23,24,25,26] However it is lower than the medication adherence reported in Scotland (91%).[27] The difference is adherence rate could be due to cost of medical care and drugs, better care services and patient awareness about medication adherence.[28]

Majority of the subjects participated in this study was between 30 and 40 years of age and the same age group shows maximum adherence (n = 64, 82%) to antihypertensive medications. However study conducted in North America showed that participants aged 30-40 years have low adherence when compared to elder ones. This discrepancy in result could be due to the reason that people of old generation have strong false belief such as fear of taking medication, side-effects of medication and so they are more often surrounded by the myths about their disease and medicines which could enhance rate of non-compliance.[29] Another possible reason for this difference in results could be due to the poor understanding of hypertension by this age group and the reluctance of accepting hypertension as a major threatening disease. Furthermore, in developing countries like Pakistan it was reported that older patient showed better compliance and it was mainly due to better social support structure supported by extended family system which have resulted in improved medication adherence.[25] Another study reported that inadequate health literacy, impaired cognition and decline in functions make elderly patients more prone to non-adherence.[30]

This study also focused on associating medication adherence with gender and it was found that in male patients adherence to anti-hypertensive medications was on higher side as compared to their female counterparts (87.7% vs. 74.7%). This finding is in line with a study conducted in US, where sex was a significant predictor of adherence and men were more likely to be adherent then women.[31] In contrast, another study reported that the adherence rate between men and women were almost equal (61.4% vs. 60.9).[26] Similarly, few researches have shown that women are more likely to adhere to anti-hypertensive medications as most men are unaware to their hypertension and those whose who are aware are less likely to be taking their medication in a way as prescribed to them.[32] Furthermore, another study conducted on Chinese hypertensive participants showed that female patients were positively associated with anti-hypertensive mediations.[33] The disparity of results among studies highlights the issue of sex differences in barriers to anti-hypertensive medication adherence. Poor sexual functioning and body mass index of 25 kg/m2 or more are the factors associated with low medication adherence to anti-hypertensive medications in males while dissatisfaction with communication with health care provider and depressive symptoms were associated with low adherence in females.[34]

The study revealed that side-effect of medications, a form of intentional non-adherence, was the most common factor reported by participants. Many studies have supported this result by reporting that side-effect is one of the most important determinants of adherence in hypertensive patient.[35,36] It is therefore needed that health care provider must increase patients’ knowledge and understanding about the disease and the pharmacotherapy to increase the likelihood of medication adherence. The other approach could be to design a regime which caters an individual need of a patient in terms of affectivity and tolerability.

Forgetfulness was the most reported non-intentional non-adherence factor. This result was consistent with the study conducted in US which reported the same. This could sometimes prove to be very hazardous for patients as they often rely on self-thought approaches and try to double the dose to compensate for the missed dose. This could amplify the danger of potential adverse effects of an individual drug. Necessary interventions must be made to overcome this issue. The possibilities could be a regular follow-up with effective counseling and by using real time medication monitoring system.[37]

The urbanization effect has also influenced medication adherence as busy work schedules often force patient to omit doses while at work due to busy schedules and hence inconvenience is what they face while they are outside home. This study supports this statement as inconvenience of taking medicines outside home was the second most reported reason of intentional non-adherence. This result is also uniform with another past research which has shown that busy life-style is an important barrier to medication adherence in hypertensive population.[38]

This study has some limitations such as; self-reporting was the only method employed in this study which is subjective in nature and may have under estimated the status of non-adherence when compared to objective measures of non-adherence such as pill count and prescription refills. However, Morisky et al. have reported that the self-report approach of measuring adherence is simple, inexpensive and useful way of identifying non-adherence in clinical setting.[20] This study did not include hypertensive patient from in-patient setting and also excluded those who are taking medication for other co-morbidities. Hence the extent of generalizability is limited to similar patients; nonetheless the study provides some useful results which would be helpful in improving the rate of medication adherence in hypertensive population.

Conclusion

Overall, more than three-fourth of the hypertensive participants were found to be adherent to their treatment. The study also revealed major factors such as side-effects, forgetfulness, busy schedule, inconvenience of taking medicine outside home are major barriers to anti-hypertensive medications. There is a need to tailor the therapy according to individual need of the patients to maximize the adherence and accomplish the eventual goal of controlling blood pressure.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:487–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hashmi SK, Afridi MB, Abbas K, Sajwani RA, Saleheen D, Frossard PM, et al. Factors associated with adherence to anti-hypertensive treatment in Pakistan. PLoS One. 2007;2:e280. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haynes RB, McDonald HP, Garg AX. Helping patients follow prescribed treatment: Clinical applications. JAMA. 2002;288:2880–3. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sackett LD, Haynes RB, Gordon HG, Tugwell P. Textbook of Clinical Epidemiology. 2nd ed. London: Little, Brown and Company; 1991. Clinical Epidemiology. A basic science for clinical medicine; pp. 249–77. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Durán-Varela BR, Rivera-Chavira B, Franco-Gallegos E. Pharmacological therapy compliance in diabetes. Salud Publica Mex. 2001;43:233–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McElnay JC, McCallion CR, al-Deagi F, Scott M. Self-reported medication non-compliance in the elderly. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;53:171–8. doi: 10.1007/s002280050358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gottlieb H. Medication non-adherence: Finding solutions to a costly medical problem. Drug Benefit Trends. 2000;12:57–62. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Muntner P, Whelton PK, He J. Global burden of hypertension: Analysis of worldwide data. Lancet. 2005;365:217–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17741-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: The JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–72. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Standing P, Deakin H, Norman P, Standing R. Hypertension - its detection, prevalence, control and treatment in a quality driven British general practice. Br J Cardiol. 2005;12:471–6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolf-Maier K, Cooper RS, Banegas JR, Giampaoli S, Hense HW, Joffres M, et al. Hypertension prevalence and blood pressure levels in 6 European countries, Canada, and the United States. JAMA. 2003;289:2363–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.18.2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saleem F, Hassali AA, Shafie AA. Hypertension in Pakistan: Time to take some serious action. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60:449–50. doi: 10.3399/bjgp10X502182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karagiannis A, Hatzitolios AI, Athyros VG, Deligianni K, Charalambous C, Papathanakis C, et al. Implementation of guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. The impulsion study. Open Cardiovasc Med J. 2009;3:26–34. doi: 10.2174/1874192400903010026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Urquhart J. The electronic medication event monitor. Lessons for pharmacotherapy. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1997;32:345–56. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199732050-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Munger MA, Van Tassell BW, LaFleur J. Medication nonadherence: An unrecognized cardiovascular risk factor. MedGenMed. 2007;9:58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rasmussen JN, Chong A, Alter DA. Relationship between adherence to evidence-based pharmacotherapy and long-term mortality after acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2007;297:177–86. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ockene IS, Hayman LL, Pasternak RC, Schron E, Dunbar-Jacob J. Task force #4 – Adherence issues and behavior changes: Achieving a long-term solution. 33rd Bethesda Conference. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:630–40. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02078-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Concordance, adherence and compliance in medicine taking. Report for the National Coordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organization R and D (NCCSDO) 2005. [Last cited on 2013 May 12]. Available from: http://www.sdo.lshtm.ac.uk/files/project/76-final report.pdf .

- 19.Raosoft: An online sample size calculator, Inc; c2008. [Last cited on 2013 May 12]. Raosoft.com. Available from: http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html . [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care. 1986;24:67–74. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diehl AK, Sugarek NJ, Bauer RL. Medication compliance in non-insulin-dependent diabetes: A randomized comparison of chlorpropamide and insulin. Diabetes Care. 1985;8:219–23. doi: 10.2337/diacare.8.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Youssef RM, Moubarak II. Patterns and determinants of treatment compliance among hypertensive patients. East Mediterr Health J. 2002;8:579–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dessie A, Asres G, Meseret S, Birhanu Z. Adherence to antihypertensive treatment and associated factors among patients on follow up at University of Gondar Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:282. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Sande MA, Milligan PJ, Nyan OA, Rowley JT, Banya WA, Ceesay SM, et al. Blood pressure patterns and cardiovascular risk factors in rural and urban Gambian communities. J Hum Hypertens. 2000;14:489–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fogarty J, Youngs GA., Jr Psychological reactance as a factor in patient noncompliance with medication taking: A field experiment. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2000;30:2365–91. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park KA, Kim JG, Kim BW, Kam S, Kim KY, Ha SW, et al. Factors that affect medication adherence in elderly patients with diabetes mellitus. Korean Diabetes J. 2010;34:55–65. doi: 10.4093/kdj.2010.34.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inkster ME, Donnan PT, MacDonald TM, Sullivan FM, Fahey T. Adherence to antihypertensive medication and association with patient and practice factors. J Hum Hypertens. 2006;20:295–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yiannakopoulou ECh, Papadopulos JS, Cokkinos DV, Mountokalakis TD. Adherence to antihypertensive treatment: A critical factor for blood pressure control. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2005;12:243–9. doi: 10.1097/00149831-200506000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacLaughlin EJ, Raehl CL, Treadway AK, Sterling TL, Zoller DP, Bond CA. Assessing medication adherence in the elderly: Which tools to use in clinical practice? Drugs Aging. 2005;22:231–55. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200522030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chapman RH, Benner JS, Petrilla AA, Tierce JC, Collins SR, Battleman DS, et al. Predictors of adherence with antihypertensive and lipid-lowering therapy. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1147–52. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.10.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Degoulet P, Menard J, Vu HA, Golmard JL, Devries C, Chatellier G, et al. Factors predictive of attendance at clinic and blood pressure control in hypertensive patients. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1983;287:88–93. doi: 10.1136/bmj.287.6385.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Management of patient compliance in the treatment of hypertension. Report of the NHLBI Working Group. Hypertension. 1982;4:415–23. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.4.3.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wong MC, Jiang JY, Griffiths SM. Factors associated with antihypertensive drug compliance in 83,884 Chinese patients: A cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010;64:895–901. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.091603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holt E, Joyce C, Dornelles A, Morisky D, Webber LS, Muntner P, et al. Sex differences in barriers to antihypertensive medication adherence: Findings from the cohort study of medication adherence among older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:558–64. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bloom BS. Continuation of initial antihypertensive medication after 1 year of therapy. Clin Ther. 1998;20:671–81. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(98)80130-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nelson EC, Stason WB, Neutra RR, Solomon HS. Identification of the noncompliant hypertensive patient. Prev Med. 1980;9:504–17. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(80)90045-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vervloet M, van Dijk L, Santen-Reestman J, van Vlijmen B, Bouvy ML, de Bakker DH. Improving medication adherence in diabetes type 2 patients through Real Time Medication Monitoring: A randomised controlled trial to evaluate the effect of monitoring patients’ medication use combined with short message service (SMS) reminders. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:5. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nair KV, Belletti DA, Doyle JJ, Allen RR, McQueen RB, Saseen JJ, et al. Understanding barriers to medication adherence in the hypertensive population by evaluating responses to a telephone survey. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2011;5:195–206. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S18481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]