Abstract

Periodontal regeneration is defined as the reproduction or reconstitution of a lost or injured part to restore the architecture and function of the periodontium. The ultimate goal of periodontal therapy is to regenerate the lost periodontal tissues caused by periodontitis. The most positive outcome of periodontal regenerative procedures in intra bony defect has been achieved with bone grafts. For complete regeneration, delivery of growth factors in a local environment holds a great deal in adjunct to bone grafts. Platelet rich fibrin (PRF) is considered as second generation platelet concentrate, consisting of viable platelets, releasing various growth factors. Hence, this case report aims to investigate the clinical and radiological (bone fill) effectiveness of autologous PRF along with the use of alloplastic bone mineral in the treatment of intra bony defects.

KEY WORDS: Alloplast, chronic periodontitis, intra bony defects, platelet rich fibrin

Periodontal regeneration is a multifactorial process and requires a multi-dependent sequence of biological events including cell-adhesion, migration, proliferation and differentiation.[1] The ultimate goal of periodontal therapy is to regenerate the lost periodontal tissues caused by periodontitis.[2] Various controlled clinical trials have demonstrated that some of the available grafting procedures may result in periodontal regeneration in intrabony defects, but complete and predictable reconstruction of periodontal tissues is still difficult to obtain.[3] The reason is that periodontium, once damaged has a limited capacity for regeneration.[4] The most positive outcome of periodontal regeneration procedures in intrabony defect has been achieved with a combination of bone graft and guided tissue regeneration.[5,6]

The complex series of events associated with periodontal regeneration involves recruitment of locally derived progenitor cells subsequently differentiated into periodontal ligament forming cells, cementoblasts or bone forming osteoblasts. Therefore, the key to periodontal regeneration is to stimulate the progenitor cells to reoccupy the defects.

Growth factors are the vital mediators during this process which can induce the migration, attachment, proliferation and differentiation of periodontal progenitor cells. Platelet rich fibrin (PRF) may be considered as a second generation platelet concentrate, using simplified protocol, is a recently innovative growth factor delivery medium. In an article in 2008 Carroll et al., in vitro study demonstrated that the viable platelets released six growth factors like platelet derived growth factor (PDGF), vasculo endothelial growth factor, transforming growth factor (TGF), insulin such as growth factor, epidermal growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor in about the same concentration for 7 day duration of their study.[7]

PRF described by Choukroun et al.[8] allows one to obtain fibrin mesh enriched with platelets and growth factors, from an anticoagulant free blood harvest without any artificial biochemical modification. The PRF clot forms a strong natural fibrin matrix which concentrates almost all the platelets and growth factors of the blood harvest and shows complex architectures as a healing matrix, including mechanical properties, which no other platelet concentrate can offer.

It has been recently demonstrated to stimulate cell proliferation of the osteoblasts, gingival fibroblasts and periodontal ligament cells but suppress oral epithelial cell growth. In an article in 2011, Lekovic et al. demonstrated that PRF in combination with bovine porous bone mineral had the ability to increase the regenerative effects in intrabony defects.[9]

In this report, we present the clinical and radiographic changes of a patient using PRF along with alloplast as grafting material in the treatment of periodontal intrabony defect with endodontic involvement.

Case Report

The present case report is about a 29-year-old man who was referred to Department of Periodontics, Saveetha Dental College, India, with a complaint of pain in relation to the left lower tooth. On examination, the patient was systemically healthy and had not taken any long-term anti-inflammatory medications or antibiotics.

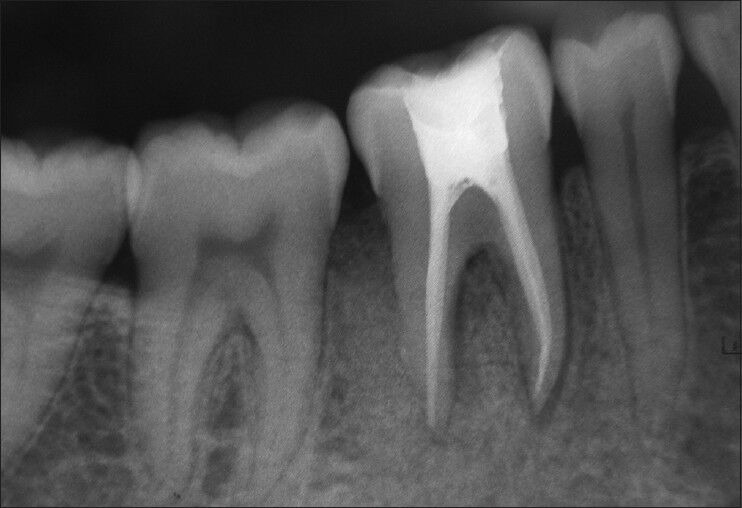

On periodontal examination and radiographic evaluation, the patient presented with an intrabony defect extending up to apical third of the mesial root [Figure 1] of left mandibular first molar (#36) with a probing depth of 8 mm using William's periodontal probe [Figure 2]. The patient also presented with pain in relation to #36 tooth and had pain on percussion. There was a lingering type of pain when subjected to heat test using a heated gutta-percha point. The diagnosis was made to be primary chronic periodontitis with secondary endodontic involvement in relation to left mandibular first molar (#36).

Figure 1.

Pre-operative radiograph

Figure 2.

Pre-operative view

Initial therapy consisted of oral hygiene instructions, which were repeated until the patient achieved an O’Leary plaque score of 20% or below.[10] Scaling and root planning of the teeth were performed. Patient was referred to Department of conservative dentistry and endodontics for root canal therapy in relation to #35 and #36 teeth (which were symptomatic to the heat test).

At 4 weeks following phase 1 therapy, a periodontal re-evaluation was performed to confirm the suitability of #36 tooth for this periodontal surgical procedure. Clinical measurements were made using William's periodontal probe with graduation to a precision of 1 mm.

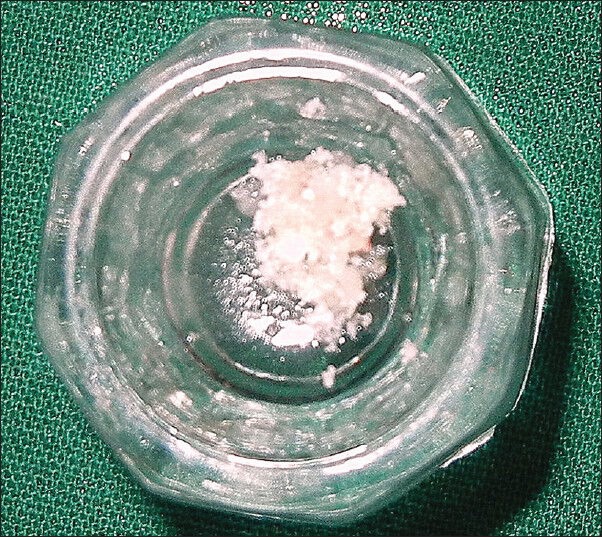

Blood sample was taken on the day of the surgery according to the PRF protocol with a REMI 3000 centrifuge and collection kits. Briefly, 6 ml blood sample was taken from the patient without an anti-coagulant in 10 ml glass test tubes and immediately centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 12 min. A fibrin clot was formed in the middle of the tube, whereas the upper part contained acellular plasma and the bottom part contained red corpuscles. The fibrin clot was easily separated from the lower part of the centrifuged blood. The PRF clot was gently pressed between two sterile dry gauges to obtain a membrane, which was later minced and added to the graft material (OSSIFI™) [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Platelet rich fibrin mixed with alloplast

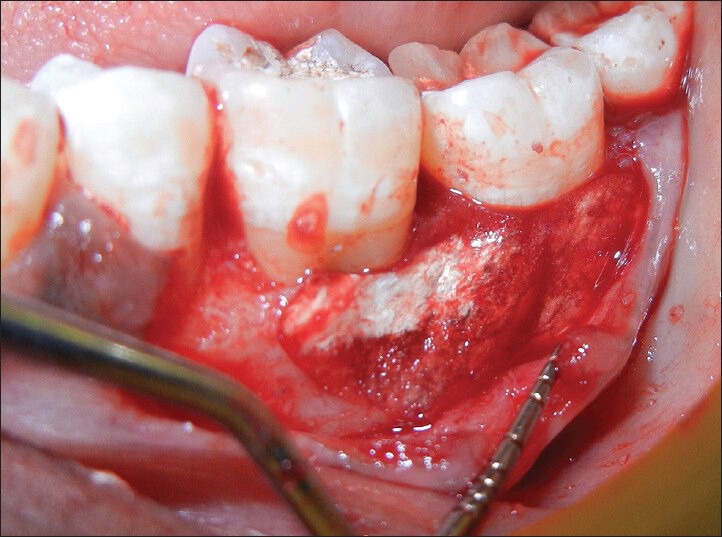

An intrasulcular incision was made on buccal and lingual aspect of the tooth of left mandibular teeth (#35, 36 and 37) along with a vertical incision, extending to the muco gingival junction in relation to the distal aspect of #35. A full thickness triangular flap was raised and inner surface of the flap was curetted to remove the granulation tissue. Root surfaces were thoroughly planned using hand instruments and ultrasonic scalers. The left mandibular first molar demonstrated mesial intrabony defect. After removing granulation tissue thoroughly, mesial intrabony defect was found to extend in buccal and apical aspect [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Intra-operative view

Briefly, alloplast (OSSIFI™) and was applied to the defect walls and root surfaces [Figures 3, 5 and 6]. The alloplast with PRF was then condensed using amalgam condensers. The flap were repositioned to their pre-surgical levels and sutured with silk utilizing an interrupted technique [Figure 7].

Figure 5.

Platelet rich fibrin with alloplast condensed in place

Figure 6.

Adaptation of guided tissue regeneration barrier membrane

Figure 7.

Flap approximated and sutures placement

After the operation, the patient was prescribed systemic antibiotics (amoxicillin 500 mg tid, 3 days), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (combiflam tid, 3 days) and 0.12% chlorhexidine rinse (twice a day for 4 weeks). Sutures were removed after 7 days. Clinical healing was normal with neither infectious episodes nor untoward clinical symptoms. The patient was seen at 1st week, 2nd week, 1st month, 3rd and 6th month.

Periapical intraoral radiographs were obtained from the periodontal defect site at baseline, 3 months and 6 months after surgery [Figure 8]. The radiographs were obtained with paralleling technique using film holders. To standardize, putty index was made and patient was asked to bite on it along with that of the holder.

Figure 8.

Post-operative radiographs after 6 months

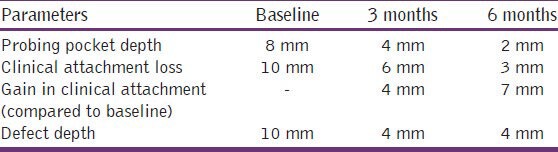

In this case report, the greater reduction in pocket depth and gain in clinical attachment were found after 6 months of the follow-up [Table 1]. These are the important clinical outcomes for any periodontal regenerative procedures. Radiographs revealed significant bone fill in the intrabony defect compared with measurements at baseline [Table 1].

Table 1.

Comparison of clinical and radiological parameters at various time intervals

Discussion

PRF by Choukran's technique is prepared naturally without addition of thrombin and it is hypothesized that PRF has a natural fibrin framework and can protect growth factors from proteolysis.[11] Thus, growth factors can keep their activity for a relatively longer period and stimulate tissue regeneration effectively. The main characteristics of PRF compared with other platelet concentrates, including platelet rich plasma (PRP), are that it does not require any anti-clotting agent.[12] The naturally forming PRF clot has a dense and complex 3-D architecture and this type of clot concentrates not only platelet but also leukocytes. PRF is simpler and less expensive to prepare, as well as being less risky to the patients. Owing to its dense fibrin matrix, PRF takes longer to be resorbed by the host, which results in slower and sustained release of platelet and leukocyte derived growth factors in to the wound area.[13,14]

In this case report, the decision to utilize minced PRF as defect fillers in combination with alloplast was made due to its ease of manipulation and delivery to the surgical site. The intended role of the minced PRF in the intrabony defect was to deliver the growth factors in the early phase of healing.

Despite of the fact that PRF is a denser and firmer agent than other biological preparations, such as PRP and enamel matrix derivative (EMD), it is still non-rigid to a degree that its space maintaining ability in periodontal defects is non-ideal. It has been reported that the combination of a mineralized, rigid bone mineral, with a semi fluid, non-rigid agent, such as EMD, significantly enhanced the clinical outcome of intrabony defects than treated without the addition of bone mineral.[15] In another study, PRF in combination in with bone mineral had the ability in increasing the regenerative effects in intrabony defects.[9] For that reason, we chose alloplast (OSSIFI™), hypothesizing that it could enhance the effect of PRF by maintaining the space for tissue regeneration to occur. Amorphous PRF when used along with bio-oss for augmentation in maxillary atrophic cases showed reduced healing time and favorable bone regeneration.[16]

In this case report, the reduction in pocket depth and gain in clinical attachment were found after 6 months follow-up. These are the important clinical outcomes for any periodontal regenerative procedures. Radiographs revealed significant bone fill in the intrabony defect compared to measurements at baseline.

PRF could improve the periodontal osseous defect healing, as PRF can up regulate phosphorylated extracellular signal regulated protein kinase expression and suppress the osteoclastogenesis by promoting secretion of osteoprotegerin (OPG) in osteoblasts cultures.[17] PRF also demonstrates to stimulate osteogenic differentiation of human dental pulp cells by upregulating OPG and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) expression.[18]

Furthermore, many growth factors are released from PRF as PDGF, TGF and have slower and sustained release up to 7 days[19] and up to 28 days,[20] which means PRF stimulates its environment for a significant time during remodeling. Moreover, PRF increase cell attachment, proliferation and collagen related protein expression of human osteoblasts.[21] PRF also enhances phosphorylated – extracellular signal regulated kinases, OPG and ALP expression which benefits periodontal regeneration by influencing human periodontal ligament fibroblasts.[22]

Conclusion

According to the results obtained in this case report, it could be concluded that the positive clinical impact of additional application of PRF with alloplastic graft material in treatment of periodontal intrabony defect is based on

Reduction in probing pocket depth.

Gain in clinical attachment level.

Significant radiographic defect bone fill.

Improved patient comfort.

Early wound healing process.

However, long-term, multicenter randomized, controlled clinical trial will be required to know its clinical and radiographic effect over bone regeneration.

Acknowledgments

We thank Department of Endondontics, H.O.D, Dr. Niveditha and my Co-Pg Dr. Surendar for their support.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Giannobile WV. The potential role of growth and differentiation factors in periodontal regeneration. J Periodontol. 1996;67:545–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Froum SJ, Gomez C, Breault MR. Current concepts of periodontal regeneration. A review of the literature. N Y State Dent J. 2002;68:14–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trombelli L. Which reconstructive procedures are effective for treating the periodontal intraosseous defect? Periodontol 2000. 2005;37:88–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2004.03798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartold PM, Shi S, Gronthos S. Stem cells and periodontal regeneration. Periodontol 2000. 2006;40:164–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2005.00139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McClain PK, Schallhorn RG. Long-term assessment of combined osseous composite grafting, root conditioning, and guided tissue regeneration. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1993;13:9–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guillemin MR, Mellonig JT, Brunsvold MA. Healing in periodontal defects treated by decalcified freeze-dried bone allografts in combination with ePTFE membranes (I). Clinical and scanning electron microscope analysis. J Clin Periodontol. 1993;20:528–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1993.tb00402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carroll RJ, Amoczky SP, Graham S, O’Connell SM. Edison, NJ: Musculoskeletal Transplant Foundation; 2005. Characterization of Autologous Growth Factors in Cascade Platelet Rich Fibrin Matrix (PRFM) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choukroun J, Adda F, Schoeffler C, Vervelle A. The opportunity in perio-implantology: The PRF. Implantodontie. 2001;42:55–62. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lekovic V, Milinkovic I, Aleksic Z, Jankovic S, Stankovic P, Kenney EB, et al. Platelet-rich fibrin and bovine porous bone mineral vs. platelet-rich fibrin in the treatment of intrabony periodontal defects. J Periodontal Res. 2012;47:409–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2011.01446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Leary TJ, Drake RB, Naylor JE. The plaque control record. J Periodontol. 1972;43:38. doi: 10.1902/jop.1972.43.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lundquist R, Dziegiel MH, Agren MS. Bioactivity and stability of endogenous fibrogenic factors in platelet-rich fibrin. Wound Repair Regen. 2008;16:356–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dohan DM, Choukroun J, Diss A, Dohan SL, Dohan AJ, Mouhyi J, et al. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): A second-generation platelet concentrate. Part I: Technological concepts and evolution. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:e37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dohan DM, Choukroun J, Diss A, Dohan SL, Dohan AJ, Mouhyi J, et al. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): A second-generation platelet concentrate. Part II: Platelet-related biologic features. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:e45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dohan DM, Choukroun J, Diss A, Dohan SL, Dohan AJ, Mouhyi J, et al. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): A second-generation platelet concentrate. Part III: Leucocyte activation: A new feature for platelet concentrates? Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:e51–5. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lekovic V, Camargo PM, Weinlaender M, Nedic M, Aleksic Z, Kenney EB. A comparison between enamel matrix proteins used alone or in combination with bovine porous bone mineral in the treatment of intrabony periodontal defects in humans. J Periodontol. 2000;71:1110–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.7.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tatullo M, Marrelli M, Cassetta M, Pacifici A, Stefanelli LV, Scacco S, et al. Platelet rich fibrin (P.R.F.) in reconstructive surgery of atrophied maxillary bones: Clinical and histological evaluations. Int J Med Sci. 2012;9:872–80. doi: 10.7150/ijms.5119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang IC, Tsai CH, Chang YC. Platelet-rich fibrin modulates the expression of extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase and osteoprotegerin in human osteoblasts. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010;95:327–32. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang FM, Yang SF, Zhao JH, Chang YC. Platelet-rich fibrin increases proliferation and differentiation of human dental pulp cells. J Endod. 2010;36:1628–32. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mazor Z, Horowitz RA, Del Corso M, Prasad HS, Rohrer MD, Dohan Ehrenfest DM. Sinus floor augmentation with simultaneous implant placement using Choukroun's platelet-rich fibrin as the sole grafting material: A radiologic and histologic study at 6 months. J Periodontol. 2009;80:2056–64. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsai CH, Shen SY, Zhao JH, Chang YC. Platelet-rich fibrin modulates cell proliferation of human periodontally related cells in vitro. J Dent Sci. 2009;4:130e5. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu CL, Lee SS, Tsai CH, Lu KH, Zhao JH, Chang YC. Platelet-rich fibrin increases cell attachment, proliferation and collagen-related protein expression of human osteoblasts. Aust Dent J. 2012;57:207–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2012.01686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang YC, Zhao JH. Effects of platelet-rich fibrin on human periodontal ligament fibroblasts and application for periodontal infrabony defects. Aust Dent J. 2011;56:365–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2011.01362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]