Abstract

The extracellular proteome, or secretome, of phytopathogenic fungi is presumed to be a key element of their infection strategy. Especially interesting constituents of this set are those proteins secreted at the beginning of the infection, during the germination of conidia on the plant surfaces or wounds, since they may play essential roles in the establishment of a successful infection. We have germinated Botrytis cinerea conidia in conditions that resemble the plant environment, a synthetic medium enriched with low-molecular weight plant compounds, and we have collected the proteins secreted during the first 16 hours by a double precipitation protocol. 2D electrophoresis of the precipitated secretome showed a spot pattern similar for all conditions evaluated and for the control medium without plant extract. The proteins in 16 of these spots were identified by PMF and corresponded to 11 different polypeptides. Alternative determination of secretome composition by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry of tryptic fragments rendered a much larger number, 105 proteins, which included all previously identified by PMF. All proteins were functionally classified according to their putative function in the infection process. Key features of the early secretome include a large number of proteases, the abundance of proteins involved in the degradation of plant defensive barriers, and plenty of proteins with unknown function.

Keywords: Botrytis, Host-pathogen interactions, Secretome

1. Introduction

Botrytis cinerea is a phytopathogenic filamentous fungus capable of infecting more than two hundred plant species [1], including a wide range of plants important in agriculture. This pathogen attacks not only plants growing in the field or in the greenhouse, but also the produce at post-harvest, usually beginning with a latent infection in the field and developing later during harvest, transport and storage [2]. Its invasion strategy is the typical of a necrotroph, killing the cells surrounding the infection area and then obtaining nutrients from the dead tissue [3, 4].

As all phytopathogenic cellular organisms, B. cinerea secretes a vast array of proteins with a variety of functions in the infection process, which has been the subject of study in search of virulence factors [5]. Most secreted proteins studied so far in B. cinerea are involved in the degradation of different plant structures/components like cellulose [6], hemicellulose [7], cutin [8], pectin [9, 10], lipids [11], proteins [12, 13], are involved in the production of active oxygen species [14], or display necrotizing activity [15]. Some of the genes corresponding to these extracellular proteins have also been knocked-out in order to gather information, from the phenotype of the mutants, about the role of the proteins in the infection process. Unfortunately, only partial requirement for virulence has been reported in a few cases [7, 16], sometimes with varying results for different strains [9, 17]. The lack of phenotype in most of these mutants has usually been explained assuming that Botrytis cinerea and other fungi often secrete multiple redundant enzymes with the same or similar function, so that the lack of one of them will go unnoticed. The genomes of two different strains of Botrytis cinerea, T4 [18] and B05.10 [19], have now been sequenced and have actually confirmed that this organism contains redundant genes for most of the extracellular enzymes. However, it is not known yet if these redundant genes are really simultaneously expressed, generating a redundant set of secreted proteins.

Proteomic tools are increasingly important in the quest for virulence factors in pathogenic fungi. New developments in experimental methods, software, and algorithms, have contributed to make this technique an effective tool for the description of fungal secretomes. The availability of the B. cinerea genome sequence now makes possible the identification of the individual components of the secretome by proteomic analysis. Similar approaches to study the array of secreted proteins and its variation under different conditions have been already used in B. cinerea [20, 21] and in other ascomycetes [22-27], reviewed by Bouws et al. [28]. The secretome of B. cinerea has been studied in two different experimental setups. The first of them [20] was aimed at the identification of proteins induced by different plant extracts in fully mature mycelium, and maybe called the “late secretome”, in contrast with the “early secretome” reported here. The second study was aimed at the identification of proteins induced by pectin, and no plant extracts were used for induction [21].

In this paper we report a new method to induce and collect extracellular proteins from Botrytis cinerea, in conditions that resemble the plant environment but do not result in contamination with host proteins. We apply this method to the identification of individual components of the protein pool secreted during the first 16 hours after inoculation, under induction with different plant extracts, by using two alternative methods, 2D electrophoresis followed by peptide mass fingerprinting on one hand, and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry of tryptic fragments, on the other.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Strains and growth conditions

The two B. cinerea strains used in this work, the wild-type strain B05.10 [19] and the aspartic protease BcAP8 mutant Δ8.9 [12], were maintained as conidial suspensions in 15% glycerol at -80°C for long storage. For routine use, fungal strains were maintained in silica gel at 4°C [29]. The silica stock was used to inoculate tomato agar plates (25% tomato extract, 2% agar, pH 5.5) with the purpose of obtaining conidia as described by Benito and associates [30]. To obtain the secretome in a given condition, 4 1-liter Erlenmeyer flasks were prepared containing 250 ml of germination medium (0.3% Gamborg´s B5, 2 mM sucrose, 10 mM KH2PO4, 0.05% Tween 80) and a dialysis bag (Sigma-Aldrich D0530, molecular weight cut-off of 12,400) enclosing 15 ml of the same germination medium plus 15 ml of plant extract (plant tissue ground thoroughly in liquid nitrogen and let thaw). The medium outside the bag was inoculated with conidia to give a final concentration of 7×106 conidia/ml and the flasks were incubated at 22°C for 16 hours in a rotary shaker set at 120 rpm. Four different germination conditions were used in this study, three of them contained different fruit extracts inside the dialysis bag (tomato, kiwi-fruit, or strawberry) and the fourth was a control medium that lacked any dialysis bag with plant extract, and contained 1% glucose instead of 2 mM sucrose.

2.2. Isolation of extracellular proteins

The culture medium was separated from the germinating conidia by centrifugation (15,000xg, 4°C, 10 min) and then filtered through several layers of filter paper (Whatman No. 1). The sample was then frozen at -20°C overnight to encourage polysaccharide precipitation, and the following day the thawed medium was filtered again through filter paper and TCA was added to a final concentration of 6% (v/v) to precipitate the proteins. After 1-hour incubation on ice, the precipitate was collected by centrifugation (15,000xg, 4°C, 10 min). The pellet was then washed three times with 96% ethanol, and resuspended in 8 M urea. After recentrifugation at 15,000xg for 5 min to eliminate the insoluble material, the supernatant was divided in four aliquots and the proteins were precipitated again with methanol-chloroform according to Wessel and Flugge [31] and stored dry at -20°C until use. One of the resulting fractions was resuspended in SDS-PAGE sample buffer and aliquots were loaded to a 12% acrylamide SDS gel electrophoresis [32] along with known amounts of bovine serum albumin (routinely 0.2 – 5 μg) to estimate the concentration of proteins in the sample. The Coomassie Blue-stained gels were analyzed with the software Quantity One (BIORAD) to calculate the amount of protein in the most intense band of the sample lane (aspartic protease BcAP8, in the case of the strain B05.10) and the whole amount of proteins in the lane. Typically, from one of the above 1-liter cultures, 4 tubes of dry secretome sample were obtained containing altogether 55-70 μg of total protein and 16-20 μg of the most abundant one.

2.3. 2D-electrophoresis

All reagents and equipment for 2D electrophoresis were from BIORAD and were used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Dry protein samples were dissolved in the appropriate volume of ReadyPrep sequential extraction Reagent 2 to achieve a concentration of 0.04 mg/ml of the most abundant protein, so that the volume loaded to the 2D electrophoresis, 125 μl, contained 5 μg of that protein. These 125 μl were used to rehydrate the 7-cm pH 4-7 IPG strips on the PROTEAN IEF cell under active conditions (50 V, 20°C, 12 hours). The protein mixture was then focused using a fast ramp to achieve a maximum of 4,000 V until 9,000 V/h were reached. Focused strips were equilibrated first in equilibration buffer (6 M Urea, 2% SDS, 0.05 M Tris/HCl pH 8.8, 20% glycerol) with 20 mg/ml DTT, for 10 min, and then in equilibration buffer with 25 mg/ml iodoacetamide, for another 10 min. The strips were then applied to a 12% acrylamide SDS gel, sealed with 0.5% low melting point agarose in SDS-PAGE running buffer containing bromophenol blue, and run at 200 V. 2D gels were finally stained with the colloidal Coomassie stain [33] and scanned with a desktop scanner (Epson perfection 1240U). All gels were repeated at least three times with secretome samples obtained from independent cultures, and similar results were obtained.

2.4. Identification of proteins by peptide mass fingerprinting (PMF)

Protein spots were excised manually from stained gels, and subjected to in-gel digestion with trypsin and desalting in 96-well ZipPlates (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions. The resulting peptides were mixed with 1 μl of 1 mg/ml α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid and spotted on Anchorchip plates as described by the manufacturer (Bruker-Daltonics). PMF spectra were measured on an Autoflex MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometer (Bruker-Daltonics) in a positive ion reflection mode at 20 kV accelerating voltage and spectra in the range 900-3200 Da were recorded. For one main spectrum, 30 subspectra with 30 shots per subspectrum were accumulated. A pepmix calibration kit (Bruker Daltonics) was used for calibration and the standard mass deviation was less than 10 ppm. The peak lists were created with Flex Analysis (V2.4) software. Selected settings were: SNAP peak detection algorithm, S/N ratio of 10, Quality factor threshold of 30, and a maximum of 100 peaks per spot. The PMFs were rechecked manually and submitted to the MASCOT search engine for protein identification using a database containing all proteins predicted from the genome sequences of the B. cinerea strains T4 (urgi.versailles.inra.fr) and B05.10 (www.broadinstitute.org). The searching parameters were set up as follows: carbamidomethyl (C) for fixed modifications, oxidation (M) for variable modifications, and ±100 ppm for peptide ion mass tolerance.

2.5. Identification of proteins by LC MS/MS

The dried secretome protein mixture prepared as explained above was resuspended in 30 μl of deionized water and mixed with 30 μl of 2X Laemmli buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA). 10 μl were then boiled at 95°C for 5 min before loading onto the gel. Proteins were separated on a 4-12% Bis-Tris precast gel (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) using the 1x MOPS SDS buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as running buffer. SeeBlue® Plus2 Prestained Standard molecular weight markers (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were used. After electrophoresis, proteins were visualized by staining with Coomassie blue. Each gel lane was excised into three sections of equal length. Excised bands were first cut into smaller pieces (1 × 1 mm), destained, dried by vacuum centrifugation, and reduced by submerging the gel pieces in 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate solution containing 10 mM dithiothreitol for 1 h at 55°C. Excess dithiothreitol/ammonium bicarbonate was removed and the same volume of 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate containing 55 mM iodoacetamide was added and incubated for 45 min in the dark. After alkylation, the gel pieces were treated with 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate and acetonitrile sequentially and then dried by vacuum centrifuge. To the dried gel pieces, 2 μg of trypsin were added in sufficient 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate solution to submerge the gel pieces in the solution. Digestion was carried out at 37°C overnight. The gel was washed once with ammonium bicarbonate followed by acetonitrile, and twice with 5% formic acid followed by acetonitrile. Peptides were collected from the washings, dried by vacuum centrifugation, and resuspended in 0.1% formic acid solution for mass spectrometric analysis.

The peptides from each sample were analyzed in duplicate. An Agilent 1100 capillary LC (Palo Alto, CA) was attached to the mass spectrometer via a T splitter to allow infusion at μl flow rates. 5-μm diameter C18 beads (Rainin, Woburn, MA) were packed into a pulled fused silica capillary (10.5 cm × 100 μm ID) under 1000 psi pressure using nitrogen gas. Peptide samples were loaded onto the column for 45 min under the same pressure. Peptides were then eluted with a gradient using 0.1% formic acid (buffer A) and 99.9% acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid (buffer B). Following the initial wash with 95% buffer A for 10 min, peptides were eluted from the column with a 90 min linear gradient of 5-60% of buffer B at a flow rate of ∼200 μl/min directly into a LTQ linear ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher, San Jose, CA) using a voltage of 2500V. The instrument was set to acquire MS/MS spectra on the nine most abundant precursor ions from each MS scan with a repeat count set of 3 and repeat duration of 5 sec. Dynamic exclusion was enabled for 160 sec. Raw tandem mass spectra were converted into a peak list using ReAdW followed by mzMXL2Other algorithms [34]. The peak lists were then searched using Mascot 1.9 (Matrix Science, Boston, MA).

For database searching and protein identification, a target database was created containing all proteins predicted for the two B. cinerea strains with sequenced genomes, B. cinerea BO5.10 (www.broadinstitute.org) and B. cinerea T4 (urgi.versailles.inra.fr). A decoy database was then constructed by reversing the sequences in the normal database. Searches were performed against the target and decoy databases using the following parameters: 1) fully tryptic enzymatic cleavage with two possible missed cleavages, 2) peptide tolerance of 800 parts-per-million, 3) fragment ion tolerance of 0.8 Da, and 4) variable modifications due to carboxyamidomethylation of cysteine residues (+ 57 Da) and deamidation of asparagine residues (+1 Da). Following the database searches, statistically significant proteins were determined for each sample at a 1% protein false discovery rate using the Provalt algorithm [35] as implemented in ProteoIQ (BioInquire, LLC, Athens, GA). Provalt parsimoniously clusters non-redundant peptides falling within the user defined criteria to protein homology groups based upon sequence homology of identified peptides. The protein with the most sequence coverage is reported as the top scoring protein.

3. Results

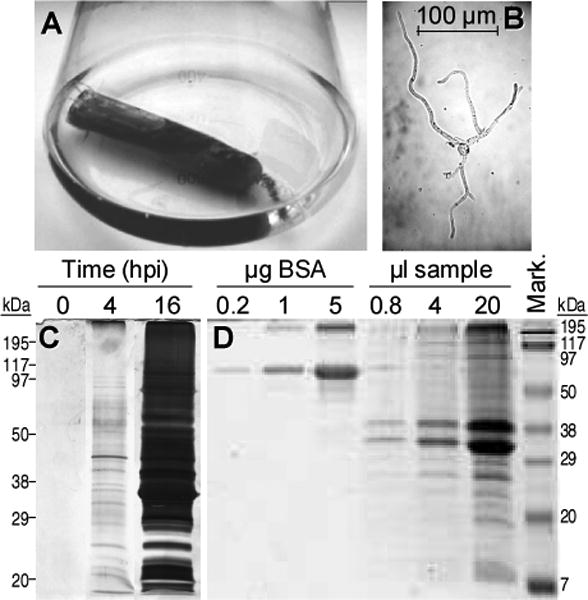

3.1. Preparation of the secretome

The aim of this work was to study the composition of the soluble protein pool secreted by Botrytis cinerea during the germination of conidia in conditions that resemble, as much as possible, those found by the fungal spores when germinating in nature on a plant. To achieve this goal, we germinated conidia at a high concentration, to maximize the amount of proteins secreted, in flasks containing germination medium plus a dialysis bag enclosing 50% plant extract (Fig. 1A). The idea behind this approach is that the small molecular weight signals that germinating conidia detect in planta will be able to cross the dialysis membrane and will also be present in the germination media, but the host proteins that could contaminate the fungal secretome, will not. Preliminary experiments showed that, although protein secretion was detectable as soon as 4 hpi, a better collection time was 16 hours, with enough proteins in the media for further experiments but still relatively short germinating tubes in the conidia (Fig. 1B and C). An added complication with the extracellular fraction of Botrytis cinerea is the high amount of polysaccharides that this fungus secretes even shortly after germination, and that resulted in a big colored pellet difficult to dissolve when the proteins were precipitated by any of the commonly used precipitation techniques. Therefore, we developed a double precipitation method in which the proteins were fist precipitated with TCA, then dissolved in 8M urea, and then reprecipitated with methanol-chloroform. In this way, the final protein preparation was quite cleaner and appropriate for 2D electrophoresis. To measure the amount of proteins in the precipitated sample, part of the pellet was usually dissolved in SDS-PAGE sample buffer and various volumes loaded to a 1D gel along with known amounts of bovine serum albumin (Fig. 1D). To check that the system was actually preventing the plant proteins from contaminating the secretome, controls were made in which the flasks were not inoculated with conidia but otherwise treated in the same way as those inoculated. No proteins could be precipitated from these media for any of the plant extracts used in this work, strawberry, tomato or kiwi-fruit (not shown).

Figure 1.

Collection and quantification of the early secretome. (A) Experimental setup to prepare the secretome. Erlenmeyer flasks containing 250 ml of germination medium, plus a dialysis bag enclosing 50% plant extract, were inoculated with B. cinerea conidia. (B) Sample picture of the typical germination state found at the secretome collection time (16 h). (C) Time course of the protein secretion. Each lane contains the proteins precipitated from 40 ml of supernatant from a culture made with strawberry extract inside the dialysis bag. Proteins were stained with silver. (D) Example of protein concentration estimation in secretome samples. Protein mixtures were loaded to an electrophoresis gel for quantification by comparison with known quantities of bovine serum albumin (BSA). 1 μl of sample corresponds approximately to 6.25 ml of supernatant from a culture made with tomato extract inside the dialysis bag.

3.2. 2D electrophoresis of the extracellular proteins

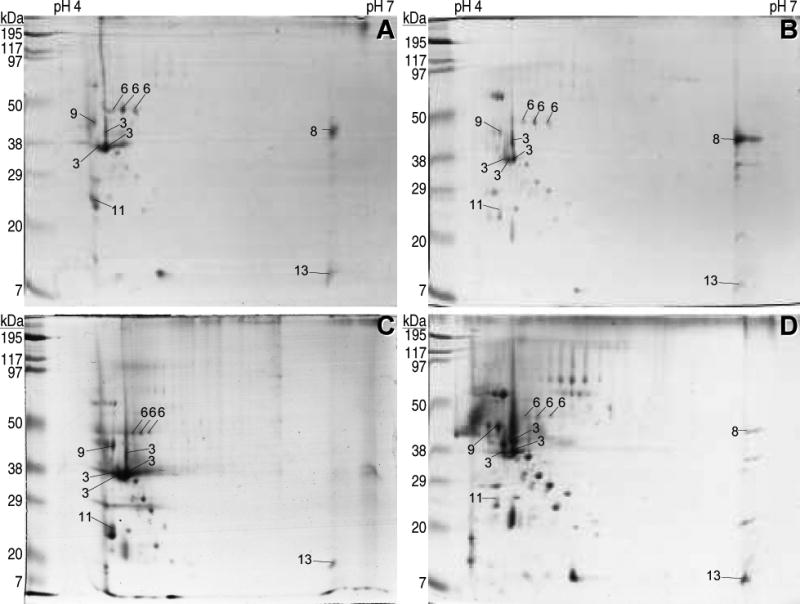

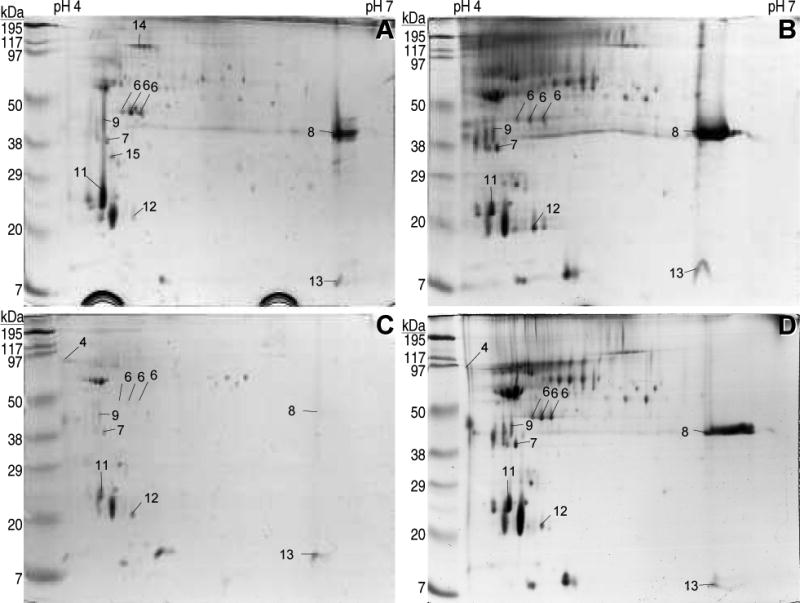

The above method was used to collect the proteins secreted during the germination of conidia from the wild-type Botrytis cinerea B05.10 strain in four different media: a control synthetic medium with glucose as the carbon source, and three other media with strawberry, tomato fruit, or kiwifruit extract inside the dialysis bag. Initial trials with 2D gels in which the first dimension was done with IPG strips spanning a pH range of 3-10 showed no major spots outside the pH range 4-7 (not shown), and therefore this latter range was chosen for all subsequent experiments. For each of the four conditions three gels were generated, and in all cases the repetitions showed a consistent and reproducible spot pattern. The complexity of the protein mixture was relatively low for the four samples, and a maximum of 56 spots could be identified, which were distributed in a pattern that was similar for the four conditions studied (Fig. 2). In these four conditions, it was also observed a big variation in spot intensity, with just a few spots showing high intensity and the rest being quite faint. The pattern seems to have a considerable number of spots common to all conditions, and only a few spots that are clearly differentially represented in some of the gels; the most evident being spot number 8, which is almost undetectable in the secretome induced with strawberry but is one of the most intense in the other three. The most abundant protein in the early secretome, constituting about 23% of the protein mass in the extracellular fraction, had already been identified as the aspartic protease BcAP8 in a previous work [12], and two independent knock-out mutants were already available. The most intense spot in the 2D gels in Fig. 2, in all four conditions, was a protein with about the size (35-38 kD) and pI (4.5-4.8) expected for the mature BcAP8 [12], and its abundance posed a limit to the amount of protein that could be loaded to the 2D gels. We therefore used a BcAP8 mutant to prepare the early secretome in order to be able to load higher quantities of protein. In the resulting 2D gels (Fig. 3) the most intense spot had disappeared, unambiguously assigning it to BcAP8, and a higher number of low intensity spots could be seen. The patterns of spots were again similar for the four germination conditions used.

Figure 2.

2D electrophoresis of the B. cinerea B05.10 early secretome. Conidia were germinated for 16 hours in the glucose control medium with no plant extract (A), or in media containing a dialysis bag enclosing 50% tomato (B), strawberry (C) or kiwifruit (D) extract. Extracellular proteins were then collected from the media by precipitation and separated on a 4–7 IPG strip, followed by 12% w/v SDS-PAGE. Numbers on the spots refer to proteins identified by PMF and are explained in Table 1.

Figure 3.

2D electrophoresis of the B. cinerea Bcap8 mutant A9 early secretome. Proteins secreted by the aspartic protease BcAP8 mutant were prepared and separated as described in the legend to Fig. 2.

3.3. Identification of the proteins spots in the 2D gels

A total of 86 spots obtained from the secretome samples of Fig. 2 and 3 were excised from the gels and the identification of the proteins was attempted by PMF. Only 16 spots were positively identified corresponding to 11 different proteins (Table 1). The most abundant protein in all gels was again identified as BcAP8 (spots 3), which appeared as four independent spots, three of them forming a charge train, and the fourth as a retarded spot which is probably a consequence of the high amount loaded for this protein. Although variable from sample to sample, the second most abundant protein was generally the endopolygalacturonase BcPG1 (spot 8), which was especially evident when the most abundant one, BcAP8, was absent (Fig. 3). BcPG1 has been shown to be required for virulence [16], emphasizing the importance of proteins secreted shortly after germination.

Table 1.

Composition of the B. cinerea early secretome.

| Putative protein - gene ID(s)a) | Spotb) | S.P.c) | Spectral countsd) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glc | Tom | Kiwi | |||

| Cuticle degradation | |||||

| Cutinase (CE5) - BC1G_06369.1; BofuT4_P062500.1 | Y | 10 | 2 | 7 | |

| Cutinase (CE5) - BC1G_02936.1; BofuT4_P003950.1 | 12 | Y | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Pectin degradation | |||||

| Endopolygalacturonase BcPG1 (GH28) [16] - BC1G_11143.1; BofuT4_P089370.1 | 8 | Y | 69 | 238 | 81 |

| Endopolygalacturonase BcPG2 (GH28) [52] - BC1G_13367.1; BofuT4_P089000.1 | Y | 118 | 80 | 9 | |

| Pectate lyase (PL1) - BC1G_12017.1; BofuT4_P032630.1 | Y | 0 | 38 | 0 | |

| Pectin methylesterase BcPME2 (CE8) [9] - BC1G_00617.1; BofuT4_P021040.1 | Y | 15 | 0 | 4 | |

| Pectin methylesterase (CE8) - BC1G_11144.1; BofuT4_P089390.1 | Y | 4 | 3 | 3 | |

| Pectin methylesterase BcPME1 (CE8) [9, 17] - BC1G_06840.1; BofuT4_P131540.1 | Y | 2 | 1 | 5 | |

| Exopolygalacturonase (GH28) - BC1G_01617.1; BofuT4_P043000.1 | Y | 2 | 0 | 3 | |

| Exo-arabinanase (GH93) - BC1G_13938.1; BofuT4_P067660.1 | Y | 0 | 0 | 4 | |

| Pectin lyase (PL1) - BC1G_12517.1; BofuT4_P012320.1 | Y | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Rhamnogalacturonase (GH2) - BC1G_03464.1; BofuT4_P132940.1 | Y | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Endopolygalacturonase BcPG3 (GH28) [41] - BC1G_04246.1; BofuT4_P094200.1 | Y | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Rhamnogalacturonan acetylesterase (CE12) - BC1G_14009.1; BofuT4_P102210.1 | Y | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Endo-α-1,5-arabinase (GH43) - BC1G_10322.1; BofuT4_P092330.1 | Y | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Exopolygalacturonase (GH28) - BC1G_13970.1 | Y | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hemicellulose degradation | |||||

| Xyloglucan specific endo-β-1,4-glucanase (GH12) - BC1G_00594.1; BofuT4_P021270.1 | Y | 15 | 16 | 0 | |

| Endo-β-1,4-xylanase Xyn11A (GH11) [7] - BofuT4_P011980.1 | Y | 1 | 27 | 0 | |

| α-L-arabinofuranosidase (GH54) with an arabinose binding domain (CBM42) - BC1G_04994.1; BofuT4_P038970.1 | Y | 0 | 1 | 8 | |

| Acetyl xylan esterase (CE1) with a cellulose binding domain (CBM1) - BC1G_07768.1; BofuT4_P006820.1 | Y | 2 | 0 | 1 | |

| Cellulose Degradation | |||||

| β-glucosidase (GH3) - BC1G_10221.1; BofuT4_P086700.1 | Y | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| β-glucosidase (GH1) - BC1G_14786.1 | Y1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Cellobiohydrolase (GH6) with a cellulose binding domain (CBM1) - BC1G_08989.1 | Y | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Other polysaccharide hydrolases | |||||

| Glucoamylase (GH15) with a starch binding domain (CBM20) - BC1G_04151.1; BofuT4_P095270.1 | 4 | Y | 438 | 63 | 118 |

| β-1,3-endoglucanase (GH17) with a GPI anchor - BC1G_09079.1; BofuT4_P100330.1 | 7 | Y | 372 | 71 | 33 |

| Invertase (GH32) - BC1G_10247.1; BofuT4_P086450.1 | Y | 28 | 0 | 5 | |

| Glucoamylase (GH15), starch binding domain (CBM20) - BC1G_08755.1; BofuT4_P000210.1 | Y | 30 | 2 | 4 | |

| α-amylase (GH13) - BC1G_02623.1; BofuT4_P108490.1 | Y | 0 | 8 | 18 | |

| Glucoamylase (GH15) - BC1G_13215.1; BofuT4_P104660.1 | Y | 7 | 0 | 1 | |

| Swollenin (expansin-like endoglucanase) - BofuT4_P160720.1 | Y | 0 | 7 | 0 | |

| Glycosyl hydrolase (GH76) - BofuT4_P027070.1 | Y | 4 | 0 | 0 | |

| β-galactosidase (GH35) - BC1G_03567.1; BofuT4_P120610.1 | Y | 1 | 0 | 3 | |

| β-1,3-glucosidase (GH17) - BC1G_11898.1; BofuT4_P026990.1 | Y | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| Endo-α-1,6-mannosidase (GH76) with a GPI anchor - BC1G_11018.1; BofuT4_P155200.1 | 15 | Y | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| exo-β-1,3-glucanase (no GH match) - BC1G_02731.1; BofuT4_P118750.1 | Y | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| α-1,2-mannosidase (GH47) - BC1G_00455.1; BofuT4_P045420.1 | Y | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| α-galactosidase (GH27) - BC1G_06546.1; BofuT4_P052080.1 | Y | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| α-glucosidase (GH31) - BC1G_12859.1; BofuT4_P089770.1 | Y | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Glycosyltransferases | |||||

| Mannosyltransferase (GT1) - BC1G_12272.1; BofuT4_P009350.1 | Y2 | 40 | 0 | 0 | |

| Glucanosyltransferase (GH16) - BC1G_00409.1; BofuT4_P045990.1 | Y | 5 | 1 | 1 | |

| β-1,3-Glucanosyltransferase (GH72) with a carbohydrate binding domain (CBM43) - BC1G_14030.1; BofuT4_P102430.1 | Y | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| β-1,3-Glucanosyltransferase (GH72) - BC1G_01903.1; BofuT4_P136550.1 | Y | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Proteases | |||||

| Aspartic protease BcAP8 (Merops A01A) [12] - BC1G_03070.1; BofuT4_P134040.1 | 3 | Y | 1252 | 1040 | 207 |

| Serine protease (Merops S53) - BC1G_02944.1; BofuT4_P003860.1 | 6 | Y | 356 | 51 | 47 |

| Glutamic protease (Merops G01) - BC1G_14153.1; BofuT4_P004950.1 | Y | 32 | 85 | 7 | |

| Metalloprotease (Merops M35) - BC1G_09180.1; BofuT4_P112580.1 | Y | 78 | 7 | 3 | |

| Serine protease (Merops S53) - BC1G_01026.1; BofuT4_P031460.1 | Y | 69 | 0 | 2 | |

| Serine protease (Merops S33) - BC1G_03976.1; BofuT4_P035810.1 | Y | 42 | 15 | 6 | |

| Serine protease (Merops S53) - BC1G_12776.1; BofuT4_P104230.1 | Y | 42 | 3 | 11 | |

| Serine protease (Merops S28) - BC1G_09564.1; BofuT4_P130720.1; BC1G_09565.1 | Y | 33 | 0 | 4 | |

| Aspartic protease BcAP5 (Merops A01A) [13] - BC1G_01794.1; BofuT4_P135550.1 | Y | 7 | 0 | 15 | |

| Serine protease (Merops S53) - BC1G_00978.1; BofuT4_P031950.1 | Y | 11 | 0 | 5 | |

| Serine protease (Merops S10) - BC1G_14591.1; BofuT4_P119560.1 | Y | 5 | 1 | 4 | |

| Aspartic protease (Merops A01A) - BC1G_07521.1; BofuT4_P083940.1 | Y | 7 | 1 | 0 | |

| Serine protease (Merops S28) - BC1G_09182.1; BofuT4_P112600.1 | Y | 2 | 0 | 1 | |

| Serine protease (Merops S10) - BC1G_01286.1; BofuT4_P028820.1 | Y | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Serine protease (Merops S10) - BC1G_03710.1; BofuT4_P022270.1 | Y | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Metalloprotease (Merops M14A) - BC1G_08658.1; BofuT4_P123410.1 | Y | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Lipases | |||||

| Lipase - BC1G_00003.1 | Y | 54 | 3 | 16 | |

| Phospholipase B - BC1G_12914.1; BofuT4_P160550.1 | Y | 12 | 2 | 1 | |

| Lipase - BC1G_02656.1; BofuT4_P119480.1 | Y | 10 | 1 | 3 | |

| Phospholipase C - BC1G_00879.1; BofuT4_P018540.1 | Y | 4 | 0 | 2 | |

| Oxidoreductases | |||||

| Glyoxal oxidase with 3 chitin binding domains (CBM18) - BC1G_01204.1; BofuT4_P029600.1 | 14 | Y | 17 | 11 | 2 |

| Quinoprotein glucose dehydrogenase - BC1G_08739.1; BofuT4_P000390.1 | Y3 | 10 | 2 | 10 | |

| Laccase - BC1G_08553.1; BofuT4_P058130.1 | Y | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Glucose oxidase - BC1G_11888.1; BofuT4_P027100.1 | Y | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Cellobiose dehydrogenase - BC1G_03188.1; BofuT4_P082390.1 | Y | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Phosphatases | |||||

| Acid phosphatase - BC1G_02965.1; BofuT4_P003570.1 | Y | 14 | 0 | 6 | |

| Histidine acid phosphatase - BC1G_02314.1; BofuT4_P141580.1 | Y | 8 | 0 | 0 | |

| Other | |||||

| Cerato-platanin family protein BcSpl1 [48] - BC1G_02163.1; BofuT4_P011930.1 | Y | 42 | 78 | 8 | |

| Ribonuclease - BC1G_11698.1; BofuT4_P015850.1 | Y | 3 | 4 | 3 | |

| Actin - BC1G_08198.1; BofuT4_P033890.1 | N | 9 | 0 | 0 | |

| Necrosis and ethylene inducing protein NEP2 [50] - BC1G_10306.1; BofuT4_P066710.1 | Y | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Ribonuclease - BC1G_14317.1; BofuT4_P096150.1 | Y | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| Polyubiquitin - BC1G_06122.1; BC1G_09783.1; BC1G_14930.1; BofuT4_P017280.1; BofuT4_P116400.1; BofuT4_P153100.1 | N | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Mitochondrial ATP synthase beta chain - BofuT4_P005390.1 | N | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Mitochondrial aconitase - BC1G_16294.1 | N | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Unknown | |||||

| Unknown, similar to IgE binding proteins - BC1G_12374.1; BofuT4_P023950.1 | 11 | Y | 516 | 176 | 4 |

| Unknown - BofuT4_P024480.1 | 13 | N | 133 | 70 | 1 |

| Unknown - BC1G_01393.1; BofuT4_P040770.1 | Y | 102 | 0 | 2 | |

| Unknown, similar to E. coli SurE and to yeast phosphatases - BC1G_11134.1; BofuT4_P089270.1 | 9 | Y | 34 | 25 | 1 |

| Unknown - BC1G_06314.1; BofuT4_P070400.1 | Y | 32 | 1 | 0 | |

| Unknown - BC1G_00198.1; BofuT4_P048190.1 | Y | 12 | 0 | 6 | |

| Unknown - BC1G_05134.1; BofuT4_P099240.1 | Y | 2 | 12 | 0 | |

| Unknown - BC1G_10379.1; BofuT4_P083380.1 | Y | 2 | 6 | 3 | |

| Unknown - BC1G_13960.1; BofuT4_P067420.1 | Y | 8 | 1 | 1 | |

| Unknown - BC1G_04742.1 | Y | 5 | 5 | 0 | |

| Unknown - BC1G_07073.1; BofuT4_P054310.1 | Y | 6 | 2 | 0 | |

| Unknown - BC1G_04328.1; BofuT4_P126060.1 | N | 5 | 3 | 0 | |

| Unknown, similar to members of the yeast SUN family - BC1G_12627.1; BofuT4_P142980.1 | Y | 2 | 0 | 3 | |

| Unknown - BC1G_07275.1; BofuT4_P138400.1 | Y | 4 | 0 | 0 | |

| Unknown, similar to oxidoreductases with a FAD binding domain - BC1G_05523.1; BofuT4_P106840.1 | N | 4 | 0 | 0 | |

| Unknown, similar to oxidoreductases with a FAD binding domain - BC1G_11556.1; BofuT4_P066110.1 | Y | 1 | 0 | 3 | |

| Unknown, similar to 3-carboxymuconate cyclase and 6-phosphogluconolactonase - BC1G_15041.1; BofuT4_P105290.1 | Y | 1 | 0 | 3 | |

| Unknown, similar to yeast spore wall proteins - BC1G_10630.1; BofuT4_P115530.1 | Y | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| Unknown, similar to oxidoreductases with a FAD binding domain - BC1G_09125.1; BofuT4_P100850.1 | Y | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| Unknown, similar to oxidoreductases with a FAD binding domain - BC1G_07482.1; BofuT4_P001770.1 | Y | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Unknown - BC1G_06114.1; BofuT4_P017380.1 | Y | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Unknown - BC1G_02154.1; BofuT4_P011810.1 | Y | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Unknown - BC1G_05726.1; BofuT4_P111000.1 | Y | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Unknown - BC1G_10475.1; BofuT4_P033240.1 | Y | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Unknown, similar to phosphatases - BC1G_12522.1; BofuT4_P012280.1 | Y | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Unknown ,Ser/Thr rich protein - BC1G_03951.1; BofuT4_P035550.1 | Y | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Unknown - BC1G_02492.1; BofuT4_P109890.1 | Y | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Unknown - BC1G_08184.1; BofuT4_P033740.1 | Y | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

Individual proteins were classified in families (inverse text) according to their putative function. In the case of glycosyl hydrolases, the CAZY family code (www.cazy.org) is included in brackets following the protein name. Merops codes (merops.sanger.ac.uk) are given for putative proteases. References are given for B. cinerea proteins previously published. Gene IDs indicate the code for each gene in the B. cinerea B05.10 (BC1G…) or B. cinerea T4 (BofuT4…) genome databases.

S.P. indicates the identification (Y) or not (N) of signal peptide in silico.

Spectral counts obtained for each protein in the three induction condition: control media with glucose (Glc), and media with tomato (Tom) or kiwi extract inside a dialysis bag.

Sequence lacks amino terminus, but most fungal homologues have signal peptide.

A signal peptide was found moving the start codon 36 nucleotides forward.

A signal peptide was found moving the start codon 15 nucleotides backward.

3.4. Identification of proteins in the secretome by LC MS/MS

Since only a low number of the spots excised from the 2D gels could be identified, we attempted to determine the composition of the early secretome by an alternative approach, liquid chromatography – tandem mass spectrometry (LC MS/MS). In this approach three different secretome samples were obtained by germinating the wild-type strain Botrytis cinerea B05.10 in three different media: a control medium with glucose as carbon source and two media with tomato or kiwifruit extracts inside the dialysis bag. The collected extracellular protein samples were loaded to a one-dimension SDS-PAGE, in-gel digested with trypsin, and the proteolytic fragments were then analyzed by LC MS/MS. The overall number of proteins identified by this approach, with a 1% protein false discovery rate, was 105 (Table 1, Supplementary Table 1). From these, 11 were found only in one of the two B. cinerea strains, 5 only in T4 (BofuT4_P005390.1; BofuT4_P011980.1; BofuT4_P024480.1; BofuT4_P027070.1; BofuT4_P160720.1) and 6 only in B05.10 (BC1G_00003.1; BC1G_04742.1; BC1G_08989.1; BC1G_13970.1; BC1G_14786.1; BC1G_16294.1). The reason for this is, in all cases, a consequence of the sequence of these two genomes not being 100% complete. For example, the code BofuT4_P011980.1 corresponds to the endo-β-1,4-xylanase Xyn11A [7], whose gene can be found intact in T4 but appears in B05.10 as a fusion with an unrelated gene (BC1G_02167.1) probably as a consequence of a bad assembly. On the contrary, the code BC1G_00003 appears only in B05.10, which is expected since the corresponding region in T4 is lacking from the genome sequence.

All the proteins identified by either PMF or LC/MSMS were further analyzed by signalP [37] in search of additional in silico evidences of extracellular localization. In some instances where the gene models were different for B05.10 and T4, in that they had different initiation codons, we manually inspected both genes and assigned a correct AUG based on similarity to other fungal proteins, and that was the one used for the signalP prediction. From the 105 proteins identified by either PMF or LC MS/MS, the vast majority did indeed look as secreted (Table 1), and only 7 were not predicted to be extracellular.

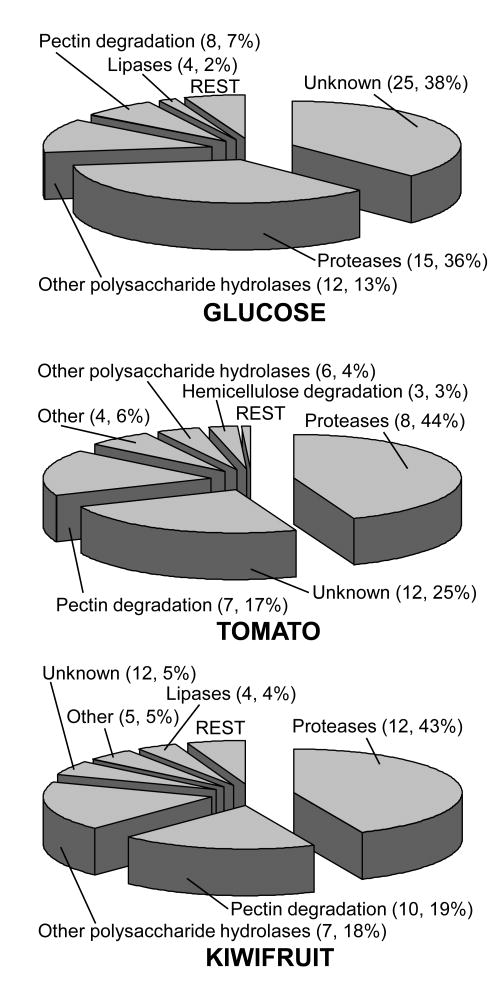

Proteins were then classified in families (Table 1) according to their putative function inferred from their sequence similarity with proteins of known function available in protein databases via the software BLAST. A total of 10 families were devised according to the contribution of the group to the infection process. The proteins not included in them were classified in two additional families, one containing proteins with putative function not fitting into any of the other families and the other containing proteins with unknown function. Four families refer to proteins that presumably degrade one of the four plant defense physical barriers, cuticle, pectin, cellulose and hemicellulose. Another four families contain other hydrolases that were not included in previous families: other polysaccharide hydrolases, proteases, lipases, and phosphatases, whose primordial function could be the breaking down of complex plant molecules into smaller compounds able to be assimilated by the fungal cells. Four proteins were classified as glycosyltransferases, with a putative function in the metabolism of the cell wall or extracellular matrix, and five proteins catalyzing oxidation/reduction reactions on diverse substrates were all put together in the family oxidoreductases.

4. Discussion

The early stages of Botrytis cinerea development in planta are crucial in the establishment of a successful infection, and can result in either a victorious penetration of the plant tissues, extending the lesions, or a necrotic spot to which the plant restricts the pathogen. In this battle, the main ammunition that the fungus can use is the set of proteins secreted at this point. Here we describe the composition of this group of proteins, or the early secretome, collected under different growing conditions.

Interestingly, the composition of the early secretome is not as variable as one could expect (Fig. 2 and 3), so that Botrytis cinerea seems to secrete during germination a common set of proteins in every situation, which is completed by a lower number of proteins specific for certain conditions. The most prominent example of the latter group, in our conditions, was the endopolygalacturonase BcPG1 (spot 8), for which big differences in spot intensity could be observed (Fig. 2 and 3).

The two alternative approaches that have been used here for protein identification match nicely between them. All proteins identified by PMF from the 2D electrophoresis gels were included among the proteins identified by the LC-MS/MS approach and, as expected, most of the proteins coming from the first approach were those with the highest spectral counts in the second. However, the number of spots that could be identified by PMF was disappointingly low, what is probably related to the fact that common post-translational modifications in secreted proteins effectively reduce the sequence coverage making identification harder. These modifications that can alter the mass of the theoretical tryptic peptides include removal of short fragments (signal peptides, propeptides), glycosylation, and even unspecific degradation by proteases. With respect to this last possibility, it is interesting to observe some differences introduced by the mutation of the aspartic protease gene BcAP8 in the pattern of bands/spots observed in the 1D [12] or 2D (Fig. 2 and 3) electrophoresis gels. The absence of the most abundant protease in the extracellular fraction, and the concomitant decrease of up to 90% in the secreted protease activity [12], cause in the 1D gels an increase in the intensity of the high molecular weight protein bands and a decrease, or even disappearance, of the smaller ones, suggesting that B. cinerea´s own abundant secreted proteases are causing significant cleavage of the secreted proteins, rendering smaller fragments that, having smaller sequence coverage, are more difficult to identify. Although deglycosylating the protein mixture prior to the 2D-electrophoresis, or protease inhibition, could be seen as ways to fix this problem, LC-MS/MS is definitely a much better option, since post-translational modifications or partial degradation have a minor influence in this technique because what has to be recognized to identify a given protein is a single peptide and not a peptide family. This fact, along with other differences such as the higher dynamic range of LC-MS/MS, made this last technique to identify, in our hands, about ten times more proteins that PMF. Contrary to previous studies of the B. cinerea secretome [20, 21] the number of proteins found in the extracellular medium which are not predicted to have signal peptide is very low, 7 out of 105 (6.6%) in this study, compared to 32% in the two previous. We attribute this success to the short time at which samples were collected, what most probably reduces greatly cell lysis and therefore contamination with intracellular proteins.

The identification of proteins by LC-MS/MS allows the semiquantitative estimation of their relative abundance in the sample, following the basic principle that the more times a given protein is detected (number of spectra, or spectral counts), the higher its abundance is. Thus, especially when its value is high, spectral counts can be used to estimate relative abundance of a protein in a mixture [36], and this can be compared for different samples to estimate the differential abundance of a given protein in, for example, different culture conditions. Table 1 shows the spectral counts for all proteins identified by LC MS/MS in the three samples. In order to derive percentage abundances from these values, spectral counts were first normalized against the size (number of amino acids) of each protein to compensate the fact that longer proteins would give more spectral counts than smaller proteins at the same concentration. The percentage of normalized spectral counts for a given protein, relative to the sum of normalized spectral counts for all the proteins identified in a given sample, was taken as an estimation of the abundance of that protein in that sample. Table 2 shows the proteins with higher abundances, more than 2% in any of the three media assayed. It is worth to note that in all three conditions there are always a small number of proteins which are highly expressed. According to this estimation, in every case 2–7 proteins constitute 50% of the protein in the sample, and a single protein, the aspartic protease BcAP8 [12], constitutes 20% or more of the total protein. This same principle was also used to estimate the abundance of each family in each condition studied (Fig. 4), this time calculated as the percentage of spectral counts (normalized against number of amino acids) in each family, relative to the total for each condition. This abundance can be contributed to by each member of the family in a very different amount, as is the case of the proteases family, in which case a single protein, the aspartic protease BcAP8, always makes up more than 50% of the family.

Table 2.

Percentage abundance of individual proteins in the early secretome.

| Putative protein - gene ID(s) | Abundancea) (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Glc | Tom | Kiwi | |

| Aspartic protease BcAP8 (Merops A01A) [12] - BC1G_03070.1; BofuT4_P134040.1 | 25,2 | 37,5 | 31,1 |

| Unknown, similar to IgE binding proteins - BC1G_12374.1; BofuT4_P023950.1 | 21,6 | 13,2 | 1,3 |

| Endopolygalacturonase BcPG1 (GH28) [16] - BC1G_11143.1; BofuT4_P089370.1 | 1,4 | 8,7 | 12,4 |

| Unknown - BofuT4_P024480.1 | 8,6 | 8,1 | 0,5 |

| Glucoamylase (GH15) with a starch binding domain (CBM20) - BC1G_04151.1; BofuT4_P095270.1 | 5,1 | 1,3 | 10,3 |

| Endopolygalacturonase BcPG2 (GH28) [52] - BC1G_13367.1; BofuT4_P089000.1 | 5,5 | 6,7 | 3,2 |

| β-1,3-endoglucanase (GH17) with a GPI anchor - BC1G_09079.1; BofuT4_P100330.1 | 6,4 | 2,2 | 4,3 |

| Cerato-platanin family protein BcSpl1 [48] - BC1G_02163.1; BofuT4_P011930.1 | 1,4 | 6,2 | 3,4 |

| Serine protease (Merops S53) - BC1G_02944.1; BofuT4_P003860.1 | 4,8 | 1,2 | 4,7 |

| Glutamic protease (G01) - BC1G_14153.1; BofuT4_P004950.1 | 1,0 | 4,6 | 1,6 |

| Unknown - BC1G_01393.1; BofuT4_P040770.1 | 4,3 | 0,0 | 0,6 |

| Lipase - BC1G_00003.1 | 1,3 | 0,1 | 2,9 |

The values were derived from data in Table 1 by calculating the percentage of normalized spectral counts for each protein with respect to the sum of normalized spectral counts of all proteins in one specific condition. Spectral counts were normalized simply by dividing by the number of amino acids in each protein. Only proteins showing an abundance higher than 2% in at least one condition are shown.

Figure 4.

Abundance of proteins families in the early secretome. Percentage abundances were estimated from data in Table 1 by calculating the percentage of normalized spectral counts in one family to the sum of normalized spectral counts in one specific condition. Abundances, as well as the number of proteins, are shown in brackets for each families. Only those families with abundances higher than 2% are shown, the rest are grouped in the slice with that name.

It is worth to note, and unexpected, the high amount of proteases that were found in the secretome. These enzymes have received little attention so far as potential virulence factors for fungi, but they comprise most of the secretome in the conditions that we have examined. Apart from their obvious role in generating amino acids to sustain fungal growth, proteases may also have important roles in two other aspects of fungal virulence. In first place, plant cell walls contain proteins such as extensins [38], whose degradation by fungal proteases could potentially contribute to cell wall softening and therefore to fungal hyphal penetration. In second place, plants secrete a vast array of defense proteins [39] in the battle against the fungal invader, and the degradation of these by fungal proteases could undermine plant defenses and increase the chances for a successful infection. The high diversity of the proteases found could also be mirroring the diverse nature of their substrates. Unlike polysaccharides, with a more fixed structure, plant proteins have by nature an incredible diversity of structures and may need a diverse pool of proteases for its degradation.

The high abundance of proteins involved in the degradation of pectin was, however, completely expected. B. cinerea shows preference for dicotyledonous plants rich in pectin and has long been assumed to have an effective pectin degradation system [3]. Moreover, pectin is particularly abundant in the anticlinal cell walls of plant epidermal cells through which B. cinerea has been shown to grow early in the infection [3]. Among the pectinolytic enzymes reported here for the early secretome, there were 3 of the 6 endopolygalacturonases previously characterized [40, 41]. Interestingly, the two endoPGs that have been reported to be required for full virulence, endoPG1 [16] and endoPG2 [40], were the two most abundant in the group, pointing to the rest of the highly expressed proteins in the early secretome as promising candidates in the search for virulence factors. The case of endoPG1 is especially interesting because it exemplifies the adaptable nature of the secretome, as it is highly expressed in three of the conditions tested, glucose, tomato or kiwifruit, but it is almost absent in strawberry (Fig. 1 and 2). This absence clearly does not hamper Botrytis cinerea virulence on strawberry, one of its favorite hosts, and allows to predict that the reduction of virulence of the endoPG1 mutant on tomato and apple [16] should not be observed for strawberries. This example emphasizes the diversity of the Botrytis cinerea armament resulting in an “overkill” strategy [3], so that an arm that is required for full virulence in one host is not even used in a different one.

Among the proteins classified as other polysaccharide hydrolases and glycosyl transferases we found several enzymes that could be involved in the metabolism of β-1,3-glucans, such as those included in the fungal cell wall and cinerean. This polysaccharide is a β-(1,3)(1,6)-D-glucan secreted by B. cinerea in high amounts to the medium for which several functions have been proposed, including extracellular energy storage or the adhesion of the conidia to the plant surface during germination [42]. The β-1,3-Glucanosyltransferases found in the secretome (BC1G_14030.1/BofuT4_P102430.1; BC1G_01903.1/BofuT4_P136550.1; and possibly BC1G_00409.1/BofuT4_P045990.1) could participate in the synthesis or remodeling of either the cell wall or the extracellular sugar matrix, but it is intriguing that enzymes potentially involved in the degradation of this polymer, like β-1,3-endoglucanase (BC1G_09079.1/BofuT4_P100330.1), β-1,3-glucosidase (BC1G_11898.1/BofuT4_P026990.1), and exo-β-1,3-glucanase (BC1G_02731.1/BofuT4_P118750.1), were secreted so early in development. On the other hand, it may also be possible that these enzymes may contribute to active induction of programmed cell death in plant cells [3, 4] by generating elicitors in the form of β-(1-3, 1-6)-oligomers [43].

The active generation of an oxidative burst by B. cinerea during infection, which adds to the defensive oxidative burst generated by the plant, has also been considered a key component of its invasion strategy, having a prominent role during the first stages of infection [3, 4]. Previously, several enzymes have been studied as potential sources of reactive oxygen species, such as a Cu-Zn-superoxide dismutase (BcSOD1), whose mutation results in reduced virulence in several different hosts, and a glucose oxidase (BcGOD1) [14]. None of them was found in the early secretome, but three other extracellular enzymes were found that could fulfill this function and that have been previously characterized as potential ROS generators in fungi [44, 45]: Glyoxal oxidase (BC1G_01204.1/BofuT4_P029600.1), whose mutation renders Ustilago maydis completely non-pathogenic and reduces H2O2 production by about 60-80% [46], quinoprotein glucose dehydrogenase (BC1G_08739.1/BofuT4_P000390.1), and cellobiose dehydrogenase (BC1G_03188.1/BofuT4_P082390.1). These three proteins therefore appear to be good candidates in the search for the proteins responsible for the ROS generation by B. cinerea.

B. cinerea has been proposed to take advantage of the plant defense response known as the hypersensitive response (HR) for its own benefit [3, 4, 47]. HR is a form of programmed cell death (PCD) that can effectively defend plants against biotrophs, but can render them more susceptible to necrotrophs such as B. cinerea. Two proteins were found in the early secretome that can help induce HR in plants. The first one is BcSpl1 (BC1G_02163.1/BofuT4_P011930.1) [48], a member of the hydrophobin-like cerato-platanin family, similar to a phytotoxic protein first identified in Ceratocystis fimbriata that induced cell necrosis and autofluorescence when infiltrated in tobacco leaves [49], both reminiscent of the HR. BcSpl1 has been shown to be induced by ethylene in B. cinerea [48]. The second one is the necrosis and ethylene inducing protein NEP2 (BC1G_10306.1/BofuT4_P066710.1) [50], a protein that has been shown to kill plant cells in all dicotyledonous plants tested.

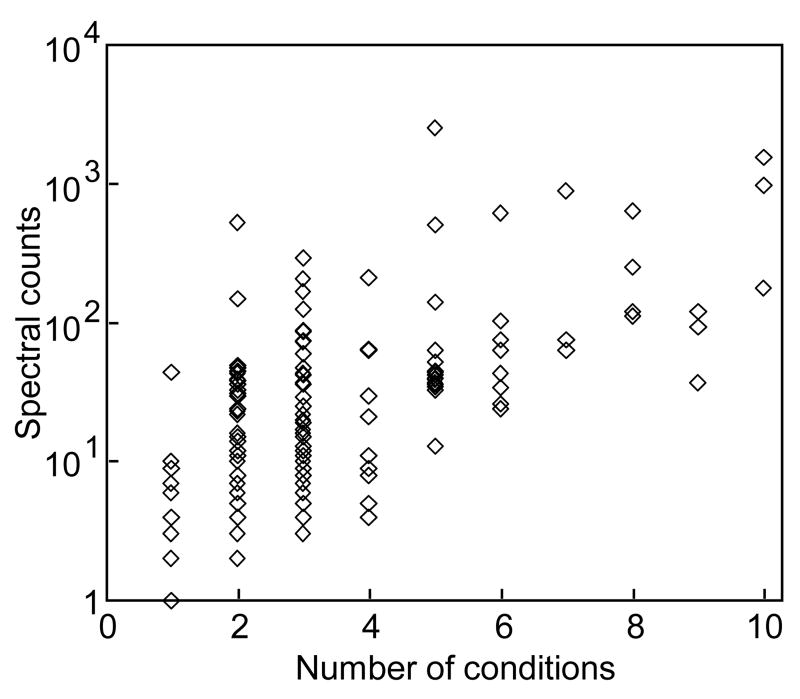

Recently, two other studies of the B. cinerea secretome have been published [20, 21] in which 89 and 131 proteins were identified. Although the conditions used to prepare the secretome samples were completely different in the methodology used to isolate the proteins and, more important, in the fungal growth conditions, the availability of these sets of data gives us the opportunity to compare the B. cinerea secretome in quite different conditions (Supplementary Table 2). A total of 236 proteins have been identified in the ten different growing conditions comprised by the three studies, from which only three appeared in every case: the candidate phytotoxic protein BcSpl1 [48], of the cerato-platanin family, the pectin methyl esterase 1 [9, 17], and a protein of unknown function that has been usually classified as IgE binding protein, probably a common fungal allergen, distantly related to the Saccharomyces cerevisiae protein Cwp1p [51]. The comparison of these sets of data seems to imply, at first glance, that the B. cinerea secretome is highly adaptative, in the sense that very different sets of proteins are secreted when the grow conditions, or the age of the mycelium, differ. The fact that only three proteins from the total number of 238 are present in the ten conditions, or that only 21 are represented in more that 5 of the 10 conditions, or that 80% of the 238 proteins are represented in only 1 to 3 conditions, all seem to imply that B. cinerea greatly alters the composition of the secreted protein pool to meet the requirement of the different growing needs. However, a close analysis of the relationship between the spectral counts obtained for each protein and its appearance in the different conditions (Fig. 5), reveals a general trend indicating that the higher the spectral counts are for a given protein, the more conditions in which it appears. This may indicate simply that proteins highly abundant in the secretome, being more easily detectable, tend to appear in more conditions than those less abundant. Low abundance proteins would therefore appear in one condition or another just by chance, and not as a consequence of regulation of their expression by the fungus. This would imply that much of the observed differences in secretome composition discussed above obey to statistical reasons, so that differential regulation of secreted protein expression may not be as high as initially suspected. There are plenty of examples among the 238 proteins, however, for which big differences in spectral counts cannot be accounted for by the mere chance, and for these proteins differential regulation of gene expression from one condition to another can be further investigated. The most clear example in this respect is the case of the aspartic protease BcAP8, a protein with the highest spectral counts in the early secretome (this study), but with low or no spectral counts in the culture medium of mature mycelium [20, 21], in good agreement with the fact that the level of Bcap8 mRNA is the highest at 12 hours after germination and decreases thereafter [12]. The gene coding for this protease has been disrupted, and the phenotype of the mutant has been studied. Apart from a great decrease in the protease activity detected in the extracellular fraction, no other obvious phenotypic changes caused by the mutation could be observed, including no change in pathogenicity.

Figure 5.

Relationship between total number of spectra for each protein and number of samples in which it appears. The data in this study and in the two previous about the B. cinerea secretome [20, 21] were used to calculate, for the total number of 238 proteins reported in the three studies, the total number of spectral counts for each protein and the number of condition in which each appears from the total of ten growing conditions comprised in the three works. Each protein (◊) was then represented in the graph according to these values.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided by grants from Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia (AGL2006-09300), Gobierno de Canarias (PI2007/009), DOE “Structures and Functions of Oligosaccharins” (DE-FG02-96ER20221), and the NIH/NCRR Integrated Technology Resource for Biomedical Glycomics (P41 RR018502). J.J.E. was supported by Gobierno de Canarias.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: Ron Orlando is a co-inventor of Provalt, which has been licensed to BioInquire LLC; and Dr. Orlando is a co-founder and partial owner of this company.

References

- 1.Elad Y, Williamson B, Tudzynski P, Delen N. In: Botrytis: Biology, Pathology and Control. Elad Y, Williamson B, Tudzynski P, Delen N, editors. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Dordrecht/Boston/London: 2004. pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Droby S, Lichter A. In: Botrytis: Biology, Pathology and Control. Elad Y, Williamson B, Tudzynski P, Delen N, editors. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Dordrecht/Boston/London: 2004. pp. 349–367. [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Kan JA. Licensed to kill: the lifestyle of a necrotrophic plant pathogen. Trends Plant Sci. 2006;11:247–253. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williamson B, Tudzynski B, Tudzynski P, Van Kan JAL. Botrytis cinerea: the cause of grey mould disease. Mol Plant Pathol. 2007;8:561–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2007.00417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Staples RC, Mayer AM. Putative virulence factors of Botrytis cinerea acting as a wound pathogen. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;134:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Espino JJ, Brito N, Noda J, Gonzalez C. Botrytis cinerea endo-β-1,4-glucanase Cel5A is expressed during infection but is not required for pathogenesis. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 2005;66:213–221. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brito N, Espino JJ, González C. The endo-β-1,4-xylanase Xyn11A is required for virulence in Botrytis cinerea. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2006;19:25–32. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Kan JAL, van't Klooster JW, Wagemakers CAM, Dees DCT, van der Vlugt-Bergmans CJB. Cutinase A of Botrytis cinerea is expressed, but not essential, during penetration of gerbera and tomato. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1997;10:30–38. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1997.10.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kars I, McCalman M, Wagemakers L, Van Kan JAL. Functional analysis of Botrytis cinerea pectin methylesterase genes by PCR-based targeted mutagenesis: Bcpme1 and Bcpme2 are dispensable for virulence of strain B05.10. Mol Plant Pathol. 2005;6:641–652. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2005.00312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu J, Prade R, Mort A. Expression and action pattern of Botryotinia fuckeliana (Botrytis cinerea) rhamnogalacturonan hydrolase in Pichia pastoris. Carbohydr Res. 2001;330:73–81. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)00268-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reis H, Pfiffi S, Hahn M. Molecular and functional characterization of a secreted lipase from Botrytis cinerea. Mol Plant Pathol. 2005;6:257–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2005.00280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.ten Have A, Espino JJ, Dekkers E, Sluyter SCV, et al. The Botrytis cinerea Aspartic Proteinase family. Fungal Genet Biol. 2010;47:53–65. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.ten Have A, Dekkers E, Kay J, Phylip LH, Van Kan JAL. An aspartic proteinase gene family in the filamentous fungus Botrytis cinerea contains members with novel features. Microbiology. 2004;150:2475–2489. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rolke Y, Liu SJ, Quidde T, Williamson B, et al. Functional analysis of H2O2-generating systems in Botrytis cinerea: the major Cu-Zn-superoxide dismutase (BCSOD1) contributes to virulence on French bean, whereas a glucose oxidase (BCGOD1) is dispensable. Mol Plant Pathol. 2004;5:17–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2004.00201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schouten A, van Baarlen P, van Kan JAL. Phytotoxic Nep1-like proteins from the necrotrophic fungus Botrytis cinerea associate with membranes and the nucleus of plant cells. New Phytol. 2008;177:493–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.ten Have A, Mulder W, Visser J, van Kan JA. The endopolygalacturonase gene Bcpg1 is required for full virulence of Botrytis cinerea. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1998;11:1009–1016. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1998.11.10.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valette-Collet O, Cimerman A, Reignault P, Levis C, Boccara M. Disruption of Botrytis cinerea pectin methylesterase gene Bcpme1 reduces virulence on several host plants. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2003;16:360–367. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2003.16.4.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levis C, Fortini D, Brygoo Y. Transformation of Botrytis cinerea with the nitrate reductase gene (niaD) shows a high frequency of homologous recombination. Curr Genet. 1997;32:157–162. doi: 10.1007/s002940050261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Büttner P, Koch F, Voigt K, Quidde T, et al. Variations in ploidy among isolates of Botrytis cinerea: implications for genetic and molecular analyses. Curr Genet. 1994;25:445–450. doi: 10.1007/BF00351784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shah P, Atwood JA, Orlando R, El MH, et al. Comparative Proteomic Analysis of Botrytis cinerea Secretome. J Proteome Res. 2009 doi: 10.1021/pr8003002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shah P, Gutierrez-Sanchez G, Orlando R, Bergmann C. A proteomic study of pectin-degrading enzymes secreted by Botrytis cinerea grown in liquid culture. Proteomics. 2009;9:3126–3135. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oda K, Kakizono D, Yamada O, Iefuji H, et al. Proteomic Analysis of Extracellular Proteins from Aspergillus oryzae Grown under Submerged and Solid-State Culture Conditions. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:3448–3457. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.5.3448-3457.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Medina ML, Kiernan UA, Francisco WA. Proteomic analysis of rutin-induced secreted proteins from Aspergillus flavus. Fungal Genet Biol. 2004;41:327–335. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2003.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Medina ML, Haynes PA, Breci L, Francisco WA. Analysis of secreted proteins from Aspergillus flavus. Proteomics. 2005;5:3153–3161. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suarez MB, Sanz L, Chamorro MI, Rey M, et al. Proteomic analysis of secreted proteins from Trichoderma harzianum - Identification of a fungal cell wall-induced aspartic protease. Fungal Genet Biol. 2005;42:924–934. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yajima W, Kav NN. The proteome of the phytopathogenic fungus Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Proteomics. 2006;6:5995–6007. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsang A, Butler G, Powlowski J, Panisko EA, Baker SE. Analytical and computational approaches to define the Aspergillus niger secretome. Fungal Genet Biol. 2009;46:S153–S160. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2008.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bouws H, Wattenberg A, Zorn H. Fungal secretomes, nature's toolbox for white biotechnology. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;80:381–388. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1572-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delcan J, Moyano C, Raposo R, Melgarejo P. Storage of Botrytis cinerea using different methods. J Plant Pathol. 2002;84:3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benito EP, ten Have A, van't Klooster JW, Van Kan JAL. Fungal and plant gene expression during synchronized infection of tomato leaves by Botrytis cinerea. Eur J Plant Pathol. 1998;104:207–220. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wessel D, Flügge UI. A method for the quantitative recovery of protein in dilute solution in the presence of detergents and lipids. Anal Biochem. 1984;138:141–143. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(84)90782-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, et al. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Hoboken, NJ: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neuhoff V, Arold N, Taube D, Ehrhardt W. Improved staining of proteins in polyacrylamide gels including isoelectric focusing gels with clear background at nanogram sensitivity using Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 and R-250. Electrophoresis. 1988;9:255–262. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150090603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pedrioli PG, Eng JK, Hubley R, Vogelzang M, et al. A common open representation of mass spectrometry data and its application to proteomics research. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:1459–1466. doi: 10.1038/nbt1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weatherly DB, Atwood JA, III, Minning TA, Cavola C, et al. A Heuristic Method for Assigning a False-discovery Rate for Protein Identifications from Mascot Database Search Results. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:762–772. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400215-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu H, Sadygov RG, Yates JR. A Model for Random Sampling and Estimation of Relative Protein Abundance in Shotgun Proteomics. Anal Chem. 2004;76:4193–4201. doi: 10.1021/ac0498563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Emanuelsson O, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. Locating proteins in the cell using TargetP, SignalP and related tools. Nat Protocols. 2007;2:953–971. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jamet E, Canut H, Boudart G, Pont-Lezica RF. Cell wall proteins: a new insight through proteomics. Trends Plant Sci. 2006;11:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferreira RB, Monteiro S, Freitas R, Santos CN, et al. The role of plant defence proteins in fungal pathogenesis. Mol Plant Pathol. 2007;8:677–700. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2007.00419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kars I, Krooshof GH, Wagemakers L, Joosten R, et al. Necrotizing activity of five Botrytis cinerea endopolygalacturonases produced in Pichia pastoris. Plant J. 2005;43:213–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wubben JP, Mulder W, ten Have A, van Kan JA, Visser J. Cloning and partial characterization of endopolygalacturonase genes from Botrytis cinerea. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1596–1602. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.4.1596-1602.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stahmann KP, Pielken P, Schimz KL, Sahm H. Degradation of Extracellular {beta}-(1,3)(1,6)-D-Glucan by Botrytis cinerea. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:3347–3354. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.10.3347-3354.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamaguchi T, Yamada A, Hong N, Ogawa T, et al. Differences in the recognition of glucan elicitor signals between rice and soybean: β-glucan fragments from the rice blast disease fungus Pyricularia oryzae that elicit phytoalexin biosynthesis in suspension-cultured rice cells. Plant Cell. 2000;12:817–826. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.5.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baldrian P, Valaskova V. Degradation of cellulose by basidiomycetous fungi. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2008;32:501–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ander P, Marzullo L. Sugar oxidoreductases and veratryl alcohol oxidase as related to lignin degradation. J Biotechnol. 1997;53:115–131. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(97)01680-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leuthner B, Aichinger C, Oehmen E, Koopmann E, et al. A H2O2-producing glyoxal oxidase is required for filamentous growth and pathogenicity in Ustilago maydis. Mol Genet Genomics. 2005;272:639–650. doi: 10.1007/s00438-004-1085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Choquer M, Fournier E, Kunz C, Levis C, et al. Botrytis cinerea virulence factors: new insights into a necrotrophic and polyphageous pathogen. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2007;277:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chague V, Danit LV, Siewers V, Gronover CS, et al. Ethylene sensing and gene activation in Botrytis cinerea: A missing link in ethylene regulation of fungus-plant interactions? Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2006;19:33–42. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pazzagli L, Cappugi G, Manao G, Camici G, et al. Purification, Characterization, and Amino Acid Sequence of Cerato-platanin, a New Phytotoxic Protein from Ceratocystis fimbriata f. sp. platani. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:24959–24964. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.35.24959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Staats M, Van Baarlen P, Schouten A, Van Kan JAL, Bakker FT. Positive selection in phytotoxic protein-encoding genes of Botrytis species. Fungal Genet Biol. 2007;44:52–63. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shimoi H, Iimura Y, Obata T. Molecular cloning of CWP1: a gene encoding a Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell wall protein solubilized with Rarobacter faecitabidus protease I. J Biochem. 1995;118:302–311. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.ten Have A, Breuil WO, Wubben JP, Visser J, van Kan JAL. Botrytis cinerea endopolygalacturonase genes are differentially expressed in various plant tissues. Fungal Genet Biol. 2001;33:97–105. doi: 10.1006/fgbi.2001.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.