Abstract

For many G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), including cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1R), desensitization has been proposed as a principal mechanism driving initial tolerance to agonists. GPCR desensitization typically requires phosphorylation by a G-protein-coupled receptor kinase (GRK) and interaction of the phosphorylated receptor with an arrestin. In simple model systems, CB1R is desensitized by GRK phosphorylation at two serine residues (S426 and S430). However, the role of these serine residues in tolerance and dependence for cannabinoids in vivo was unclear. Therefore, we generated mice where S426 and S430 were mutated to nonphosphorylatable alanines (S426A/S430A). S426A/S430A mutant mice were more sensitive to acutely administered delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC), have delayed tolerance to Δ9-THC, and showed increased dependence for Δ9-THC. S426A/S430A mutants also showed increased responses to elevated levels of endogenous cannabinoids. CB1R desensitization in the periaqueductal gray and spinal cord following 7 d of treatment with Δ9-THC was absent in S426A/S430A mutants. Δ9-THC-induced downregulation of CB1R in the spinal cord was also absent in S426A/S430A mutants. Cultured autaptic hippocampal neurons from S426A/S430A mice showed enhanced endocannabinoid-mediated depolarization-induced suppression of excitation (DSE) and reduced agonist-mediated desensitization of DSE. These results indicate that S426 and S430 play major roles in the acute response to, tolerance to, and dependence on cannabinoids. Additionally, S426A/S430A mice are a novel model for studying pathophysiological processes thought to involve excessive endocannabinoid signaling such as drug addiction and metabolic disease. These mice also validate the approach of mutating GRK phosphorylation sites involved in desensitization as a general means to confer exaggerated signaling to GPCRs in vivo.

Keywords: cannabinoid, CB1, desensitization, GPCR, THC, tolerance

Introduction

Psychoactive cannabinoids such as delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC) signaling through cannabinoid receptors [e.g., cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1R)] have therapeutic potential for many disorders, including neurodegeneration, perturbed GI motility, psychiatric illnesses, and chronic pain. One limitation of the therapeutic use of cannabinoids [and many other G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) agonists] is the development of tolerance following long-term administration (Bedi et al., 2010). Tolerance and dependence emerge during heavy cannabis use in humans (D'Souza et al., 2008) and could contribute to cannabis abuse. In preclinical rodent models, repeated administration of Δ9-THC causes rapid tolerance to Δ9-THC-mediated “tetrad” effects (i.e., antinociception, hypothermia, hypoactivity, and catalepsy; Nguyen et al., 2012) as well as dependence (Tsou et al., 1995).

Continuous agonist activation desensitizes G-protein-mediated responses of many GPCRs (Gainetdinov et al., 2004). Current dogma posits that desensitization of GPCRs, including CB1Rs, is a principal mechanism that drives tolerance to agonists by functionally uncoupling GPCRs from cognate G-proteins (Gainetdinov et al., 2004). Repeated in vivo treatment with cannabinoids including Δ9-THC causes CB1R desensitization, resulting in attenuated agonist-stimulated GTPγS binding in brain (Sim-Selley, 2003; Martin et al., 2004). Desensitization is often the consequence of GPCR kinase (GRK)-mediated phosphorylation of GPCRs and subsequent interaction with an arrestin protein, such as β-arrestin2 (DeWire et al., 2007; Moore et al., 2007). Mutant mice lacking β-arrestin2 exhibit enhanced acute responses to Δ9-THC, as well as altered tolerance and CB1R desensitization following repeated Δ9-THC treatment (Breivogel et al., 2008; Nguyen et al., 2012). Attenuated tolerance to Δ9-THC-mediated antinociception in β-arrestin2−/− mice was accompanied by decreased CB1R downregulation and impaired desensitization of agonist-stimulated GTPγS binding in the cerebellum, periaqueductal gray (PAG), and spinal cord (Nguyen et al., 2012).

Previous studies found that rapid desensitization of CB1R-activated, G-protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ channels (GIRKs; Kir 3.1 and 3.4) in Xenopus oocytes required coexpression of β-arrestin2 and GRK type 3 (Jin et al., 1999). Similarly, rapid desensitization of CB1R activation of GIRK channels was absent in AtT20 cells expressing CB1Rs with the S426A/S430A mutation. Subsequent work demonstrated that serines 426 and 430 were also required for rapid desensitization of CB1R-activated ERK 1/2 signaling (Daigle et al., 2008b). In addition, GRKs and β-arrestins appear to be involved in desensitizing cannabinoid-inhibited synaptic transmission (Kouznetsova et al., 2002). CB1Rs with S426A/S430A mutations internalize appropriately (Jin et al., 1999). However, CB1Rs where six distal C-terminal serines and threonines are mutated to alanines do not internalize, suggesting that distinct GRK phosphorylation sites underlie desensitization and internalization for CB1Rs (Hsieh et al., 1999; Daigle et al., 2008a).

To test the hypothesis that CB1R desensitization by phosphorylation of serines 426 and 430 drives tolerance to cannabinoids, we produced and characterized a “knock-in” mouse expressing CB1Rs with the putative GRK phosphorylation sites at residues 426 and 430 mutated to alanines (S426A/S430A). S426A/S430A mutant mice exhibited enhanced acute behavioral responses and physical dependence for Δ9-THC as well as delayed tolerance. Our mouse model thus represents a novel tool for studying the effects of chronically overactive endocannabinoid signaling on CB1R-mediated effects on metabolism, drug addiction, learning and memory, and emotive behavior.

Materials and Methods

Drugs.

URB597 and N-arachidonoyl ethanolamine [anandamide (AEA)] were obtained from Cayman Chemical. Δ9-THC and N-(piperidinyl)-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-1-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-4-methyl-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxamide [SR141716A (SR1)] were obtained from the National Institute on Drug Abuse Drug Supply. All drugs administered in vivo were dissolved in 0.9% saline, 5% Cremaphor EL, and 5% ethanol (18:1:1 v/v/v).

Generation of S426A/S430A mice.

The fragment containing the mutant CB1R was subcloned into the p4517D vector (a gift from Dr. Richard Palmiter, University of Washington, Seattle, WA) as follows. A CB1R fragment was cut out of BAC343L8 with KpnI/EcoRI and ligated into pcDNA3.0 to add an XhoI site 3′ to EcoRI. This was then cut with KpnI/XhoI and ligated into pSK+. A HA epitope sequence and S426A/S430A mutations were introduced into the mouse CB1R/pSK+ construct by subcloning and PCR site-directed mutagenesis, respectively. The S426A/S430A HA CB1R sequence was removed from pSK+ with KpnI/XhoI and ligated into p4517D cut with KpnI/SalI. The p4517D vector contains a neomycin phosphotransferase (NeoR) gene flanked by FLP recombinase sequences. The 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of CB1R was removed from BAC343L8 with EcoRI and ligated into pSK+ to add XhoI and NotI sites on the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively. This was then cut out of pSK+ and ligated into the CB1R/4517D construct just 3′ of the NeoR sequence (Fig. 1A).

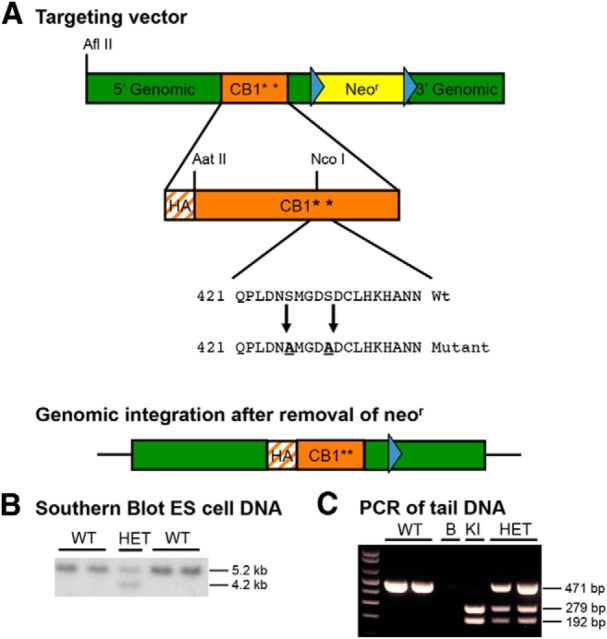

Figure 1.

Generation of S426A/S430A knock-in mice. A, Mice expressing a desensitization-resistant form of CB1R were produced using a targeting vector designed to mutate two putative GRK phosphorylation sites, serines 426 and 430, to nonphosphorylatable alanines. Additionally, the targeting vector introduced an N-terminal HA tag into CB1R and contained a NeoR gene flanked by FLP recombinase sites (blue triangles). B, Correct integration of the targeting vector was verified in ES cells by Southern blot analysis. A genomic DNA probe located outside of the targeting vector was used to detect a 5.2 kb WT fragment and a 4.2 kb mutant fragment after digestion of ES cell DNA with HindIII. C, PCR analysis of tail or ear DNA was used to determine the genotypes of offspring from heterozygous matings. NcoI digestion of the PCR of the mutant allele (KI) product produced two fragments, while the WT product produced a single band, and heterozygotes produced the predicted three bands. The no template control is shown in the lane labeled “B.”

The construct was electroporated into R1 embryonic stem (ES) cells, which subsequently underwent selection in G418. The presence of the transgene was confirmed via Southern blotting using a randomly primed DNA probe against sequence lying between the EcoRI and HindIII sites. The targeting vector for the S426A/S430A transgenic mouse introduced a HindIII site into the 3′ UTR of CB1R. This change resulted in a fragment of 4.3 kb for mice with the S426A/S430A mutation compared with 5.3 kb for the wild-type (WT) mice when genomic DNA was cut with HindIII (Fig. 1B).

Approximately 200 G418-resistant clones were screened by Southern blotting to identify ES cell clones with correct recombination. Additional screening of positive ES cell clones was performed using a nested PCR strategy with primers that overlaid within the 3′ genomic region of the targeting vector and the NeoR cassette. Three of the four doubly positive ES clones that were injected into blastocysts gave highly chimeric mice (up to 99% chimerism as determined by coat color). Offspring demonstrating germline transmission of the mutation were bred to Rosa26-FLPR mice (The Jackson Laboratory) to remove the NeoR gene (Fig. 1A). Mice lacking the NeoR gene were then subsequently bred to C57BL/6J mice, and the resulting heterozygotes were bred to obtain homozygous WT and S426A/S430A mice used in these experiments. Routine identification of WT, heterozygous, and homozygous S426A/S430A mice was performed using PCR analysis of tail DNA with primers 202-1-F (5′-CGACATGGTGTATGATGTCT-3′) and 202-2-R (5′-AGCACGGTGACAGTCACTAT-3′). PCR fragments were then digested with NcoI to identify fragments amplified from the mutant allele (Fig. 1C). All animal care and experimental procedures used in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the University of Washington, Indiana University, Penn State University College of Medicine, or Virginia Commonwealth University, and conform to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guidelines on the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All experiments conducted in this study were performed using male S426A/S430A mutant and WT littermate control mice.

Western blotting.

Mouse brain lysates (30 μg/well) were run on 4–12% Nu-PAGE gels (Invitrogen) and were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes as previously described (Nyíri et al., 2005). Blots were then incubated overnight with both rabbit anti-CB1R (Nyíri et al., 2005) and mouse anti-β-tubulin (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank at the University Iowa, Iowa City, IA) antibodies diluted in Odyssey blocking buffer (Li-Cor Biosciences) at 1:1000 and 1:20,000 dilutions, respectively. Secondary antibodies included a donkey anti-rabbit IR800 (Rockland). and a goat anti-mouse IR680 (Li-Cor Biosciences). Blots were incubated for 2 h in secondary antibodies and were then analyzed with the Li-Cor Biosciences Odyssey imaging system. Densities were determined using ImageJ software (NIH). Images of blots were inverted in Adobe Photoshop Elements 10, as shown (Fig. 2). Data were normalized to the intensity of the mouse monoclonal β-tubulin antibody.

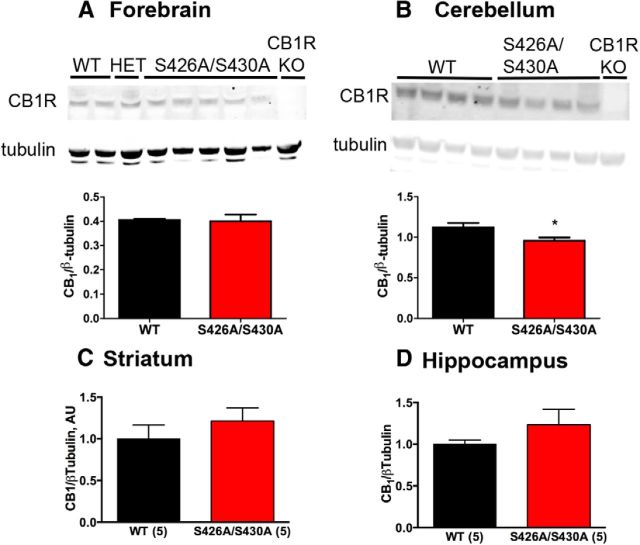

Figure 2.

CB1R protein levels are largely unchanged in S426A/S430A mutant brains. A–D, Western blot analysis of CB1R protein levels in forebrain (A), cerebellum (B), striatum (C), and hippocampus (D) of S426A/S430A mutant, WT, and CB1R KO mice. In A and B, the top bands are CB1R as detected by the L15 rabbit polyclonal antibody and bottom bands are β-tubulin (tubulin), used to normalize protein loading of individual samples. Average CB1R/tubulin density ratios shown for the forebrain (A), cerebellum (B), striatum (C), and hippocampus (D) were analyzed with unpaired t tests (WT, N = 2–5; S426A/S430A, N = 4–5). Also shown in A and B is the absence of CB1R immunoreactivity in equivalent brain regions from a CB1R KO mouse, demonstrating the specificity of the L15 antibody.

Materials for GTPγS and [3H]CP55,940 binding.

-(+)-[2,3-Dihydro-5-methyl-3-[(morpholinyl)methyl]pyrrolo[1,2,3-de]-1,4-benzoxazinyl]-(1-naphthalenyl)methanone mesylate [WIN55,2122-2 (WIN)], GTPγS, GDP, and bovine serum albumin (BSA) were purchased from Sigma. (−)-cis-3-[2-hydroxy-4-(1,1-dimethylheptyl)phenyl]-trans-4-(3-hydroxypropyl) cyclohexanol (CP 55,940), SR1, and [3H]CP55,940 (88.3 Ci/mmol) were obtained from the Drug Supply Program of the National Institute on Drug Abuse. [35S]GTPγS (1150–1300 Ci/mmol) was purchased from PerkinElmer. All other reagent grade chemicals were purchased from Sigma or Fisher Scientific.

Membrane preparation.

Mice were killed by decapitation, and spinal cords and PAG were dissected on ice and placed in 20 volumes of cold Buffer A (50 mm Tris-HCl, 3 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EGTA, pH 7.4). Tissue was homogenized, centrifuged at 48,000 × g at 4°C for 10 min, and then resuspended in Buffer B (50 mm Tris-HCl, 3 mm MgCl2, 0.2 mm EGTA, 100 mm NaCl, pH 7.4). The protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method using Bio-Rad dye reagent.

[3H]CP55,940 binding.

For saturation analysis, spinal cord membranes (30 μg) were incubated for 90 min at 30°C in Buffer B with 0.5% BSA, 0.06–2.5 nm [3H]CP55,940 in a total volume of 0.5 ml. For competition binding experiments, cerebellar membranes (15 μg) were similarly incubated with 1.5 nm [3H]CP55,940 and varying concentrations of AEA, Δ9-THC, or SR1. Nonspecific binding was assessed in the presence of 5 μm unlabeled CP55,940. Incubations were terminated by vacuum filtration through GF/B glass fiber filters, followed by three washes with ice-cold 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4. Bound radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation spectrophotometry at 45% efficiency for 3H after extraction of the filters in scintillation fluid.

Agonist-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding.

Membrane homogenates from cerebellum, PAG, spinal cord, or hippocampus were prepared in Buffer B and were preincubated for 10 min at 30°C with adenosine deaminase (4 mU/ml) to remove endogenous adenosine. Samples containing 6–8 μg of membrane protein were incubated for 2 h at 30°C in Buffer B with 30 μm GDP, 0.1 nm [35S]GTPγS, 0.1% BSA, and varying concentrations of CP55,940, AEA, or Δ9-THC. Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 20 μm unlabeled GTPγS. Reactions were terminated by rapid vacuum filtration through GF/B glass fiber filters, and the radioactivity was measured by liquid scintillation spectrophotometry at 95% efficiency for 35S after extraction of the filters in scintillation fluid.

Data analysis for [35S]GTPγS and [3H]CP55,940 binding.

All samples were incubated in duplicate ([3H]CP55,940 binding) or triplicate ([35S]GTPγS binding), and data are reported as the mean ± SEM. Net-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding is defined as stimulated minus basal (absence of agonist) binding. The percentage of stimulation is defined as (net-stimulated/basal [35S]GTPγS binding) × 100%. Concentration–effect curves in vehicle-treated or Δ9-THC-treated mice were initially analyzed by two-way ANOVA (drug treatment or genotype × CP55,940 concentration) to determine significant main effects or interactions between groups. Saturation binding and concentration–effect curves were analyzed by nonlinear regression to obtain Bmax and KD or Emax and EC50 values, respectively, using GraphPad Prism software. Values were analyzed to determine statistical significance using two-way ANOVA (genotype × drug treatment) followed by post hoc analysis with the Bonferroni test or by one-way ANOVA with the post hoc Bonferroni test.

Endocannabinoid quantification.

Anadamide-d4 was purchased from Tocris Bioscience. AEA, N-palmitoyl ethanolamine (PEA), and 2-arachidonoyl glycerol (2-AG) were purchased from Cayman Chemical. N-arachidonoyl glycine (NAGly) was purchased from Biomol. HPLC-grade water and methanol were purchased from VWR International. HPLC-grade acetic acid and ammonium acetate were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Lipid extracts of tissues were performed as previously described (Bradshaw et al., 2006). Samples were separated using a C18 Zorbax reversed-phase analytical column. Gradient elution (200 μl/min) was driven using two Shimadzu 10AdVP pumps. Eluted samples were analyzed by electrospray ionization using an Applied Biosystems/MDS Sciex API3000 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer. A multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) setting on liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) was then used to analyze the levels of each compound present in the sample injection. Synthetic standards were used to generate optimized MRM methods and standard curves for analysis.

Acute response to Δ9-THC.

Tail-flick antinociception and hypothermia were measured in mice given intraperitoneal injections of Δ9-THC. All injections were given in a volume of 10 μl/g body weight. Antinociceptive testing was conducted using a Columbus Instruments TF-1 tail-flick analgesia meter. The radiant heat source on the apparatus was calibrated to elicit a tail-flick latency of 3–4 s in untreated WT control mice. A 10 s cutoff was used for all testing sessions to avoid tissue damage to the tail. The tail-flick latency was measured before drug treatment and also 55 min after drug treatment to calculate the antinociceptive response as the percentage of the maximal possible effect (%MPE) with %MPE = (post-drug latency − pre-drug latency)/(10 − pre-drug latency) × 100. Drug-induced hypothermia was measured by taking body temperature using a mouse rectal thermometer (Physitemp). Body temperatures were taken 30, 60, 120, 180, 240, and 300 min after Δ9-THC. The percentage change in body temperature was calculated as ((pre-drug temperature − post-drug temperature)/pre-drug) temperature × 100.

Locomotor activity.

Open-field locomotor activity was measured for 90 min using photocell chambers equipped with infrared photobeam arrays (Accuscan Instruments). Spontaneous open field activity was calculated as the activity occurring during the first 30 min (t = 0–30 min) of the testing session. Habituated activity was calculated as the locomotor activity occurring during the last 30 min (t = 60–90 min) of the testing session.

Δ9-THC dose–response curves.

Both antinociception and hypothermia were measured in separate drug-naive mice given 0, 1, 10, 30, or 50 mg/kg doses of Δ9-THC. All injections were given intraperitoneally in an injection volume of 10 μl/g body weight. Tail-flick antinociception and hypothermia were measured at 55 and 60 min after each drug dose was administered, respectively.

Tolerance.

Tolerance was measured in mice given once-daily intraperitoneal injections of 10 mg/kg or 30 mg/kg Δ9-THC for 7 consecutive days. Tail-flick antinociception and body temperature were measured each day at 55 and 60 min after drug treatment, respectively.

Hippocampal cell culture and electrophysiology.

Hippocampal neurons isolated from the CA1–CA3 region were cultured on microislands as previously described (Straiker and Mackie, 2005). For desensitization experiments, neurons were treated overnight with 100 nm WIN55,212-2 (WIN) in vehicle (0.001% DMSO). We have previously found that overnight treatment with vehicle alone does not affect subsequent responses to cannabinoid agonists (Straiker et al., 2012). WIN washes out with a half-life of 5.5 min (Straiker and Mackie, 2005). Consequently, after overnight treatment with WIN, cultures were washed for at least 20 min before testing depolarization-induced suppression of excitation (DSE).

Because in these neurons an increasing duration of depolarizing stimulus results in progressively stronger inhibition via DSE, we have found that it is convenient to use depolarization duration (in seconds) as a “dose,” plotted on a log scale to obtain a log “stimulus duration–response curve” with properties similar to a classical dose–response curve. Taking the largest maximal slope of the curve in combination with observed baseline and maximal responses allows us to derive an ED50. This ED50 reflects the duration of depolarization required to induce a response halfway between the baseline and the maximum response.

Relative EPSC charge data are presented as proportions (relative to baseline). Nonlinear regression was used to fit the concentration response curves. Treatment effects were evaluated by testing for overlap of 95% confidence intervals (CIs). An exception was made in the case of desensitized responses, which have relatively flattened curves for which a reliable ED50 cannot be determined. In this case, we compared individual points using a two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple-comparison tests where indicated.

Δ9-THC dependence.

Precipitated withdrawal behaviors were measured in male S426A/S430A mutant and WT littermate mice that were administered twice daily subcutaneous injections (9:00 A.M. and 6:00 P.M.) of vehicle or 50 mg/kg Δ9-THC for a period of 5.5 consecutive days (Schlosburg et al., 2009). Withdrawal was precipitated 30 min after the last Δ9-THC injection with an intraperitoneal injection of vehicle or 10 mg/kg rimonabant (SR1), a CB1R inverse agonist. Physiological manifestations of withdrawal (paw tremors, diarrhea, and jumps) were recorded on video for 60 min following injection of rimonabant or vehicle. Withdrawal signs occurring in alternating 5 min intervals (5–10, 15–20, 25–30, 35–40, 45–50, and 55–60 min) were then scored by a trained observer blind to genotype. The following conditions were examined for each strain/genotype of mouse: 5.5 d of vehicle injections followed by an injection of vehicle on the sixth day, 5.5 d of vehicle injections followed by an injection of rimonabant on the sixth day, and 5.5 d of Δ9-THC injections followed by an injection of rimonabant on the sixth day.

Results

Generation of S426A/S430A mutant mice

To make a mouse expressing a desensitization-resistant form of CB1R, we produced a targeting vector designed to change two putative GRK phosphorylation sites, serines 426 and 430, to nonphosphorylatable alanines (Fig. 1A). Correct integration of the targeting vector in ES cells that were used to produce chimeras was verified by Southern blot analysis using a genomic DNA probe located outside of the targeting vector (Fig. 1B). A PCR genotyping strategy was used to identify S426A/S430A heterozygous and mutant mice (Fig. 1C). Homozygous S426A/S430A mutants were viable, fertile, and had grossly normal cage behaviors. Breeding of heterozygous S426A/S430A males and females produced the expected frequency of S426A/S430A homozygous mutants (N = 157/631; 25%).

CB1R expression

We sought to determine whether CB1R expression was altered as a consequence of mutating serines 426 and 430 to alanines using ex vivo preparations of tissues from male S426A/S430A and WT littermate mice. The amount of CB1R protein in brain regions from 12-week-old S426A/S430A mutant mice was determined by Western blot analysis of forebrain (Fig. 2A), cerebellum (Fig. 2B), striatum (Fig. 2C), and hippocampus (Fig. 2D). The level of CB1R protein observed in S426A/S430A mutant brains was largely unchanged with the exception of the cerebellum (Fig. 2B), where a 15% decrease was observed in mutant mice (Student's t test; *p < 0.01).

To determine whether the S426A/S430A mice had altered levels of endocannabinoids, a mass spectrophotometry lipidomics approach was used to examine the levels of AEA, 2-AG, PEA, and NAGly using quantitative LC-MS/MS. The only endocannabinoid level that was changed in the brains of S426A/S430A mutant relative to WT mice was 2-AG in the cortex (Table 1). However, no differences in 2-AG levels were detected in the striatum, hippocampus, cerebellum, midbrain, or forebrain of S426A/S430A mutant mice compared with WT mice. Together, these data suggest that the S426A/S430A mutation does not cause widespread dysregulation of brain endocannabinoid levels.

Table 1.

2-AG is decreased in the cortex of S426A/S430A mutants

| Mice | Location | AEA (pmol/g) | PEA (pmol/g) | NAGly (pmol/g) | 2-AG (nmol/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | Cortex | 14.98 ± 0.89 | 229 ± 27.9 | 26.7 ± 2.1 | |

| S426A/S430A | Cortex | 15.42 ± 1.77 | 255 ± 28.4 | 17.6 ± 1.1* | |

| WT | Striatum | 6.83 ± 0.13 | 274 ± 23.6 | 17.9 ± 1.5 | |

| S426A/S430A | Striatum | 6.84 ± 0.15 | 265 ± 24.3 | 15.1 ± 1.2 | |

| WT | Hippocampus | 6.82 ± 0.92 | 177 ± 37.7 | 11.8 ± 1.1 | 21.5 ± 1.1 |

| S426A/S430A | Hippocampus | 7.49 ± 0.54 | 177 ± 17.6 | 15.8 ± 0.7 | 26.4 ± 3.4 |

| WT | Cerebellum | 4.34 ± 0.35 | 297 ± 23.3 | 4.50 ± 0.26 | 45.1 ± 4.6 |

| S426A/S430A | Cerebellum | 5.39 ± 0.35 | 391 ± 28.6 | 7.31 ± 0.94 | 39.3 ± 2.8 |

| WT | Midbrain | 5.91 ± 0.46 | 362 ± 40.3 | 37.6 ± 3.8 | |

| S426A/S430A | Midbrain | 6.77 ± 0.28 | 383 ± 33.4 | 35.3 ± 3.2 | |

| WT | Forebrain | 11.68 ± 1.00 | 209 ± 40.2 | 17.5 ± 2.3 | |

| S426A/S430A | Forebrain | 14.00 ± 1.89 | 251 ± 22.9 | 22.0 ± 3.9 |

The amount of each lipid normalized to tissue weight in grams is presented as the average ± SEM, and the data were analyzed using unpaired Student's t test.

*p < 0.01. The amounts of AEA, PEA, NAGly, and 2-AG in the cerebellum, forebrain, hippocampus, striatum, midbrain, and cortex of five S426A/S430A mutants and six WT mice were quantified by LC-MS/MS.

The slightly lower CB1R protein levels in cerebellum of S426A/S430A mutant mice might indicate altered pharmacological sensitivity of cerebellar CB1Rs in the mutant mice. Therefore, to determine whether knockin of the mutant CB1R affected agonist efficacy or potency to activate G-proteins, agonist-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding was examined in cerebellar membrane preparations from male WT and S426A/S430A mutant littermate mice. These experiments examined three ligands differing in intrinsic efficacy, potency, and chemical structure: CP55,940, AEA, and Δ9-THC. There were no significant differences in the concentration–effect curves for these ligands between genotypes (data not shown), as indicated by two-way ANOVA (genotype × ligand concentration). Emax and EC50 values, derived by nonlinear regression analysis of the concentration–effect curves for each ligand, did not differ between genotypes (Table 2). Basal [35S]GTPγS binding also did not differ between genotypes (data not shown). These results indicate that replacement of WT CB1R with the S426A/S430A mutant form did not significantly alter ligand efficacy, potency, or the relatively efficacious relationship among high- and low-efficacy agonists.

Table 2.

Emax and EC50 values from concentration–effect curves of ligand-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding in cerebellum of WT and S426A/S430A CB1R knock-in mice

| Ligand | WT mice |

S426A/S430A mice |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emax (% Stimulation) | EC50 (nm) | Emax (% Stimulation) | EC50 (nm) | |

| CP55,940 | 247.9 ± 16.4 | 8.7 ± 1.3 | 235.5 ± 13.8 | 8.1 ± 1.1 |

| AEA | 244.4 ± 12.5 | 1038.4 ± 71.3 | 244.9 ± 9.2 | 1108.1 ± 109.5 |

| Δ9-THC | 104.1 ± 10.9 | 58.2 ± 5.9 | 92.4 ± 9.1 | 41.1 ± 7.1 |

Data are the mean ± SEM (n = 4). Cerebellar membranes from WT and S426A/S430A CB1 receptor knock-in mice were incubated with 30 μm GDP, 0.1 nm [35S]GTPγS, and varying concentrations of the indicated ligands, as described in Materials and Methods. Concentration–effect curves were fit by nonlinear regression. No significant differences were obtained between genotypes as determined by two-tailed Student's t test (p > 0.05).

The S426A/S430A mutation did not alter ligand potency to activate G-proteins, suggesting that the mutation did not affect ligand-binding affinity for the CB1R. To further test this hypothesis, ligand competition for [3H]CP55,940 binding was examined in cerebellar membranes from WT and S426A/S430A mutant mice. Specific [3H]CP55,940 binding densities in the absence of competitor ligand were 911 ± 104 and 810 ± 67 fmol/mg, respectively, in WT and S426A/S430A mutant mice, which were not significantly different between genotypes. As shown in Table 3, the Ki values of AEA, Δ9-THC, and the CB1 antagonist rimonabant also did not differ between genotypes. Although the Hill coefficient for AEA was approximately twofold greater in the mutant mice compared with WT mice, those of Δ9-THC and rimonabant did not differ between genotypes. These results indicate that ligand-binding affinities were not significantly affected, but the slope of the competition curve for AEA was increased by the S426A/S430A CB1R mutation.

Table 3.

Cannabinoid ligand binding affinities in cerebellum of WT and S426A/S430A CB1 receptor knock-in mice

| Ligand | WT mice |

Knock-in mice |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ki (nm) | nH | Ki (nm) | nH | |

| AEA | 27.26 ± 5.64 | 0.51 ± 0.07 | 52.58 ± 11.58 | 1.02 ± 0.15* |

| Δ9-THC | 5.19 ± 3.88 | 0.65 ± 0.26 | 9.52 ± 1.81 | 0.82 ± 0.09 |

| SR1 | 1.81 ± 0.81 | 0.73 ± 0.24 | 2.76 ± 0.74 | 0.64 ± 0.11 |

Data are mean Ki and Hill coefficient (nH) values ± SEM (n = 3–5). Cerebellar membranes from vehicle- and THC-treated WT and S426A/S430A CB1 receptor knock-in mice were incubated with 1.4 nm [3H]CP55,940 with and without varying concentrations of the indicated unlabeled competitor ligands, as described in Materials and Methods. Nonspecific binding was assessed with 5 μm unlabeled CP55,940. Competition binding data were subjected to Hill analysis.

*p < 0.05 different from WT mice by two-tailed Student's t test.

CB1R desensitization and downregulation

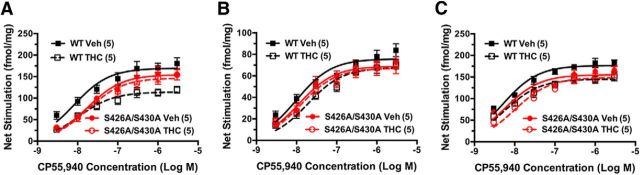

Desensitization of CB1R-mediated G-protein activation was assessed by examining CP55,940-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding in membrane homogenates from PAG, spinal cord, and hippocampus of male WT and S426A/S430A mutant littermate mice that were treated once daily for 7 d with either vehicle or 30 mg/kg Δ9-THC. In PAG, Δ9-THC treatment significantly decreased net CP55,940-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding (Fig. 3A) in WT mice (p < 0.0001, F = 72.1, df = 1) but not S426A/S430A mutant mice (p = 0.327, F = 0.978, df = 1), as determined by two-way ANOVA of the concentration–effect curves. Net-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding was also significantly different between genotypes (Fig. 3A) in both vehicle-treated (p = 0.0003, F = 14.87, df = 1) and Δ9-THC-treated mice (p = 0.0013, F = 11.54, df = 1). Nonlinear regression analysis of the concentration–effect curves revealed that Δ9-THC treatment decreased the Emax value of net CP55,940-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding by ∼34% compared with vehicle treatment in WT mice but not in S426A/S430A mutant mice (Table 4). In contrast, there was no significant effect of Δ9-THC treatment on CP55,940 EC50 values in either genotype. There was also no significant effect of genotype on CP55,940 Emax values, but the EC50 value was approximately twofold greater in vehicle-treated mutant mice, compared with WT mice.

Figure 3.

Desensitization of CB1R-mediated G-protein activation is attenuated in S426A/S430A mutants. A–C, Desensitization of CB1R-mediated G-protein activation was assessed using CP55,940-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding in membranes prepared from PAG (A), spinal cord (B), or hippocampus (C) from S426A/S430A mutant and WT mice. Data points represent mean net-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding ± SEM (n = 4–6).

Table 4.

Emax and EC50 values from concentration-effect curves of net CP55,940-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding in CNS regions of wild-type and S426A/S430A CB1 receptor knock-in mice

| Region | Treatment | WT mice |

S426A/S430A mice |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emax (fmol/mg) | EC50 (nm) | Emax (fmol/mg) | EC50 (nm) | ||

| PAG | Vehicle | 169.6 ± 13.8 | 8.6 ± 1.3 | 151.0 ± 15.9 | 17.4 ± 2.8* |

| PAG | Δ9-THC | 114.6 ± 8.5† | 11.8 ± 1.9 | 146.8 ± 11.6 | 18.6 ± 2.0 |

| Spinal cord | Vehicle | 75.8 ± 4.4 | 10.5 ± 1.1 | 69.0 ± 5.3 | 13.1 ± 2.3 |

| Spinal cord | Δ9-THC | 67.7 ± 4.0 | 20.3 ± 3.6† | 67.3 ± 6.1 | 14.3 ± 3.1 |

| Hippocampus | Vehicle | 177.0 ± 6.9 | 5.4 ± 0.9 | 155.5 ± 9.9 | 5.8 ± 0.9 |

| Hippocampus | Δ9-THC | 145.2 ± 9.0† | 6.1 ± 0.8 | 147.5 ± 8.4 | 11.1 ± 3.5 |

Data are mean Emax (net-stimulated fmol/mg) and EC50 values ± SEM (n = 5–6) derived from the concentration–effect curves from Figure 3, which were fit by nonlinear regression. Membranes from the indicated CNS regions of vehicle- and THC-treated WT and S426A/S430A CB1 receptor knock-in mice were incubated with 30 μm GDP, 0.1 nm [35S]GTPγS, and varying concentrations of CP55,940, as described in Materials and Methods.

*p < 0.05 different from wild-type mice of the same treatment group as determined by ANOVA and planned comparison with Bonferroni post hoc test.

†p < 0.05 different from vehicle-treated mice of the same genotype as determined by two-way ANOVA and planned comparison with Bonferroni post hoc test.

In the spinal cord, two-way ANOVA of the CP55,940 concentration–effect curves showed that Δ9-THC treatment significantly decreased net-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding (Fig. 3B) in WT mice (p < 0.0001, F = 22.0, df = 1) but not in S426A/S430A mutant mice (p = 0.555, F = 0.352, df = 1). There was no significant effect of Δ9-THC treatment on CP55,940 Emax values in this region, but the EC50 value was increased by approximately twofold in Δ9-THC-treated mice relative to vehicle-treated WT mice (Table 4). However, Δ9-THC treatment did not alter CP55,940 EC50 values in mutant mice. Likewise, there was no effect of genotype on either the Emax or EC50 values in either treatment group in this region.

In hippocampus, net CP55,940-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding (Fig. 3C) was significantly decreased by Δ9-THC treatment in both WT (p < 0.0001, F = 39.0, df = 1) and S426A/S430A mutant (p = 0.0004, F = 14.5, df = 1) mice, as indicated by two-way ANOVA of the concentration–effect curves. There was also a significant effect of genotype in this region such that net CP55,940-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding was lower in vehicle-treated (p < 0.0001, F = 22.6, df = 1), but not in Δ9-THC treated (p = 0.14, F = 2.24, df = 1) mice. The CP55,940 Emax value was significantly decreased by Δ9-THC treatment (Table 4) in hippocampus of WT, but not S426A/S430A mutant mice (Table 4); however, CP55,940 EC50 values were unaffected by Δ9-THC treatment. There was no effect of genotype on either Emax or EC50 values in this region. Overall, these results demonstrate that the S426A/S430A mutation prevented desensitization of CB1R-mediated G-protein activation by repeated Δ9-THC treatment in PAG and spinal cord, and attenuated this adaptation in the hippocampus. In addition, this mutation produced a modest but significant reduction in CB1R-mediated G-protein activation in PAG and hippocampus of vehicle-treated mice.

Differences in G-protein activation between genotypes were predominantly limited to CB1R-mediated activity because basal [35S]GTPγS binding did not differ between genotypes in any region examined, including PAG, spinal cord, and hippocampus, in vehicle- or Δ9-THC-treated mice (data not shown). To investigate potential indirect effects of the S426A/S430A CB1R mutation on another Gi/o-coupled receptor, we examined stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding by the μ-selective opioid agonist [d-Ala(2),N-Me-Phe(4),Gly(5)-ol]-enkephalin (DAMGO) in these CNS regions. Results showed no effect of genotype or Δ9-THC treatment on net DAMGO-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding in PAG and spinal cord (data not shown). In hippocampus, however, two-way ANOVA revealed a main effect of Δ9-THC treatment on net DAMGO-stimulated activity (p = 0.026, F = 6.21, df = 1), although no significant differences between treatment groups were detected in either genotype by post hoc analysis with the Bonferroni test. Net-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding by 10 μm DAMGO was 73.3 ± 8.8 and 106.0 ± 20.4 fmol/mg, respectively, in vehicle-treated and Δ9-THC-treated WT mice. However, there was no influence of the CB1R mutation, as similar results were obtained in S426A/S430A mutant mice, where net DAMGO-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding was 73.3 ± 8.3 fmol/mg in vehicle-treated mutant mice versus 104.3 ± 13.5 fmol/mg in Δ9-THC-treated mutant mice. Overall, these results indicate that genetic knockin of the S426A/S430A mutant CB1R does not affect basal or μ-opioid receptor-stimulated G-protein activation in these CNS regions.

To determine whether the S426A/S430A mutation might be involved in CB1R downregulation, saturation analysis of [3H]CP55,940 binding was examined in spinal cord membranes from male S426A/S430A mutant and WT littermate mice treated with vehicle or 30 mg/kg 9Δ-THC for 7 d (Table 5). Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of Δ9-THC treatment on [3H]CP55,940 Bmax values (p = 0.0042, F = 10.6, df = 1). In WT mice, Δ9-THC treatment reduced the [3H]CP55,940 Bmax value by 46%, which was determined to be significant by Bonferroni post hoc analysis. In contrast, no significant difference in Bmax value was observed between vehicle and Δ9-THC treatment in S426A/S430A mutant mice. Interestingly, two-way ANOVA also revealed a significant main effect of Δ9-THC treatment on [3H]CP55,940 KD values, indicating increased binding affinity in Δ9-THC-treated mice. However, post hoc analysis did not show a significant difference in KD values between vehicle- and Δ9-THC-treated mice in either genotype. These findings indicate that repeated treatment with 30 mg/kg Δ9-THC for 7 d is sufficient to produce significant CB1R downregulation in spinal cord of WT mice. Moreover, both Δ9-THC-induced downregulation and desensitization were attenuated in S426A/S430A mutant mice, suggesting that phosphorylation of the CB1R at S426 and/or S430 is required for agonist-induced downregulation and desensitization.

Table 5.

Bmax and KD values from [3H]CP55,940 saturation binding analysis in spinal cord of vehicle- and THC-treated wild-type and S426A/S430A CB1 receptor knock-in mice

| Ligand | WT mice |

S426A/S430A mice |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bmax (fmol/mg) | KD (nm) | Bmax (fmol/mg) | KD (nm) | |

| Vehicle | 426 ± 42 | 1.60 ± 0.29 | 406 ± 62 | 1.69 ± 0.33 |

| Δ9-THC | 231 ± 42* | 0.78 ± 0.23 | 253 ± 60 | 0.73 ± 0.28 |

Data are mean Bmax and KD values ± SEM (n = 5–6). Spinal cord membranes from vehicle- and THC-treated WT and S426A/S430A CB1 receptor knock-in mice were incubated with varying concentrations of [3H]CP55,940 with and without 5 μm unlabeled CP55,940 to measure nonspecific binding, as described in Materials and Methods. Saturation binding curves were fit by nonlinear regression.

*p < 0.05 different from vehicle-treated mice of the same genotype as determined by two-way ANOVA and planned comparison with Bonferroni post hoc test.

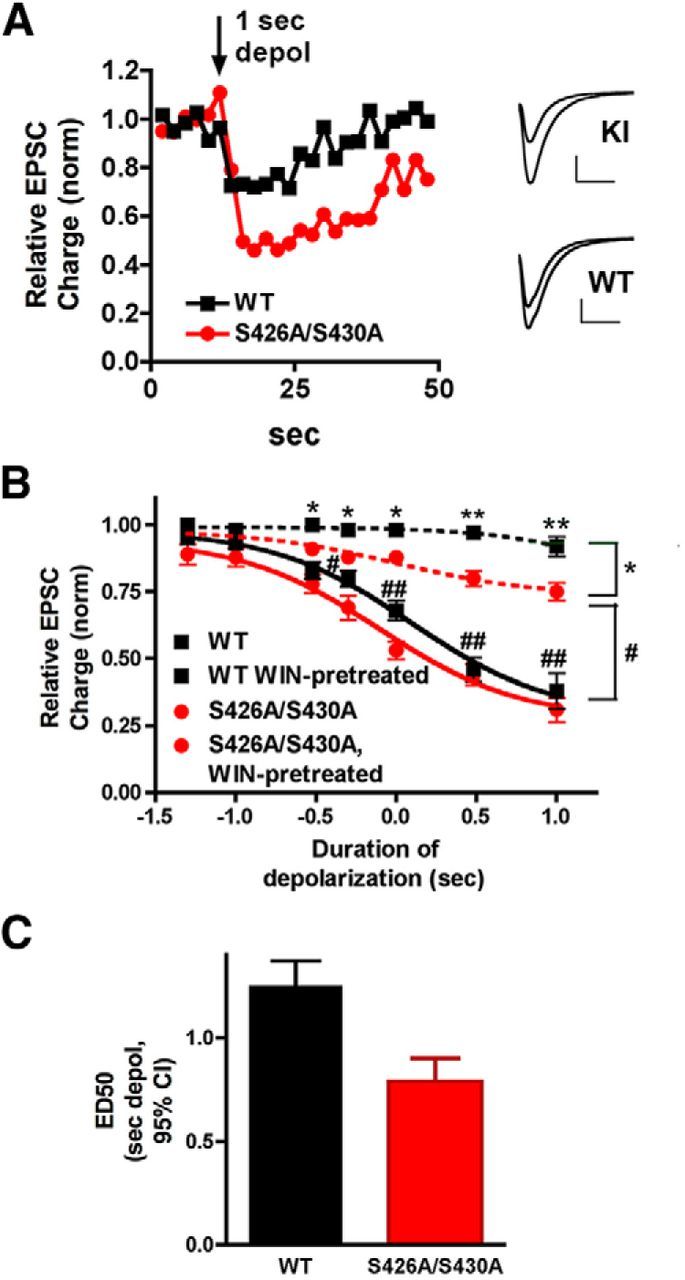

Neurons cultured from S426A/S430A mice show enhanced endocannabinoid-mediated synaptic plasticity and attenuated desensitization of CB1R-mediated signaling

To examine the functional role of the S426A/S430A mutation at the level of individual neurons, we examined cannabinoid signaling in autaptic hippocampal neurons cultured from S426A/S430A and WT mice. These cultured hippocampal neurons demonstrate robust CB1R-mediated DSE and are an excellent model system for studying endocannabinoid-mediated synaptic plasticity (Straiker and Mackie, 2005; Straiker et al., 2009, 2011).

We found that DSE for intermediate depolarizations was enhanced (Fig. 4A) and the depolarization-response curve was shifted to the left in neurons cultured from S426A/S430A mice (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, the ED50 (defined as the duration of depolarization required for 50% DSE) was shortened from 1.25 s (95% CI, 1.15–1.37 s) to 0.79 s (95% CI, 0.69–0.90 s; nonoverlapping 95% knock-in vs WT mice; Fig. 4C). Thus, neurons from S426A/S430A mice require less depolarization to produce a given amount of DSE. We also examined the relative desensitization of neurons from WT and S426A/S430A mice following overnight treatment with the CB1R agonist WIN55212–2 (100 nm). We have previously found that this treatment fully desensitizes CB1Rs (Straiker and Mackie, 2005). Interestingly, CB1Rs in S426A/S430A neurons only partially desensitized with this treatment (Fig. 4B). The reduced desensitization observed in S426A/S430A cultured hippocampal neurons is consistent with the finding that desensitization of CB1R-mediated G-protein activation was reduced, but not eliminated, in the hippocampus of S426A/S430A mutant mice treated repeatedly with Δ9-THC.

Figure 4.

S426A/S430A hippocampal neurons have enhanced DSE and desensitize more slowly. A, Sample DSE time courses in WT and S426A/S430A autaptic neurons in response to a 1 s depolarization. Inset shows sample EPSCs for S426A/S430A and WT neurons before and after the 1 s depolarization. B, Depolarization response curves in WT (black diamonds, solid line) and S426A/S430A neurons (red circles) show that the response in S426A/S430A neurons is shifted to the left. In addition, S426A/S430A neurons (red triangles, dotted lines) desensitize to a lesser extent after overnight treatment with the CB1 agonist WIN55,212-2 (100 nm) compared with WT neurons (black squares, dotted line). Brackets on right indicate grouping for statistical comparisons: top (*) compares WT-WIN-treated to S426A/S430A-WIN-pretreated; lower (#) compares WT to S426A/S430A-WIN-pretreated. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. C, Bar graph shows ED50 for “depolarization response curves” in WT vs S426A/S430A neurons derived from the solid curves in B. The ED50 refers to the duration of depolarization that is required to obtain a 50% maximal DSE inhibition. Values are in seconds with 95% CIs.

S426A/S430A mice are more sensitive to Δ9-THC

We next evaluated the behavioral responses of S426A/S430A mice to Δ9-THC. Male WT and S426A/S430A mutant male littermate mice have similar baseline tail-flick responses and body temperatures (Table 6). Furthermore, treatment with vehicle alone did not cause hypothermia or antinociceptive responses in either WT or S426A/S430A mutant mice. Body temperature changes following vehicle injection were −0.22 ± 0.31% in WT mice and −0.17 ± 0.14% in S426A/S430A mutants. The tail-flick response change after vehicle injection was 2.81 ± 2.03% in WT mice and −3.41 ± 3.52% in S426A/S430A mutant mice. Strikingly, the acute antinociceptive (Fig. 5A) and hypothermic (Fig. 5B) responses to 30 mg/kg Δ9-THC were increased in S426A/S430A mutant mice relative to WT littermates. Hypothermia was also prolonged after 30 mg/kg Δ9-THC injections in S426A/S430A mutant mice (Fig. 5B). Thus, we observed an increase in both the magnitude and duration of the effects of short-term administration of 30 mg/kg Δ9-THC in the mutant mice.

Table 6.

Basal body temperature, nociception, and open field activity is normal in S426A/S430A mutants

| Mice | Baseline tail-flick (s) | Body temperature (°C) | Spontaneous activity (cm) | Habituated activity (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 3.01 ± 0.09 | 37.9 ± 0.1 | 4331 ± 361 | 744 ± 160 |

| S426A/S430A | 3.34 ± 0.12 | 38.1 ± 0.1 | 3867 ± 376 | 855 ± 289 |

Data are presented as the averages ± SEM and were analyzed using unpaired Student's t test. No significant differences were found between the genotypes. Basal body temperature and baseline tail-flick response activity were measured in 49 S426A/S430A mutant and 55 WT mice. Spontaneous and habituated locomotor activity was examined in 12 S426A/S430A mutant and 17 WT mice.

Figure 5.

S426A/S430A mutants are more sensitive to the antinociceptive and hypothermic effects of Δ9-THC. A, B, S426A/S430A mutants (red bar or red lines with circles) exhibit increased antinociceptive (A) and hypothermic (B) responses to 30 mg/kg Δ9-THC relative to WT mice (black bar and black line with squares). C, D, The dose–response curves (1, 10, 30, and 50 mg/kg) for the antinociceptive (C) and hypothermic (D) effects of Δ9-THC were shifted to the left for S426A/S430A mutants (red lines and circles) relative to WT littermates (black lines and squares). Sample sizes for each group are in parentheses. Error bars represent the SEM, and data analyses were performed using unpaired Student's t tests (A) or two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc tests (B–D). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

A dose–response curve for Δ9-THC was generated to gain a better understanding of the pharmacological mechanism responsible for the enhanced responses to 30 mg/kg Δ9-THC. The antinociceptive and hypothermic effects of 1, 10, 30, and 50 mg/kg Δ9-THC were examined in drug-naive male S426A/S430A mutant and WT littermate mice. We found that dose–response curves for the antinociceptive (Fig. 5C) and hypothermic (Fig. 5D) effects of Δ9-THC were shifted to the left in the S426A/S430A mutant mice. Two-way ANOVA analysis indicated significant main effects of dose (F(3,138) = 18.98; p < 0.0001) on the dose response for the antinociceptive effect of Δ9-THC (Fig. 5C). Bonferroni post hoc tests indicated a significant increase in the antinociceptive effect of Δ9-THC in S426A/S430A mutant mice specifically at the 30 mg/kg dose (Fig. 5C). Two-way ANOVA also indicated significant main effects of genotype (F(1,135) = 23.02; p < 0.0001) and dose (F(3,135) = 51.30; p < 0.0001) on the dose response for the hypothermic effect of Δ9-THC (Fig. 3D). Bonferroni post hoc tests indicated that the hypothermic effects of 10, 30, and 50 mg/kg doses of Δ9-THC were significantly increased in the S426A/S430A mutant relative to WT mice (Fig. 5D).

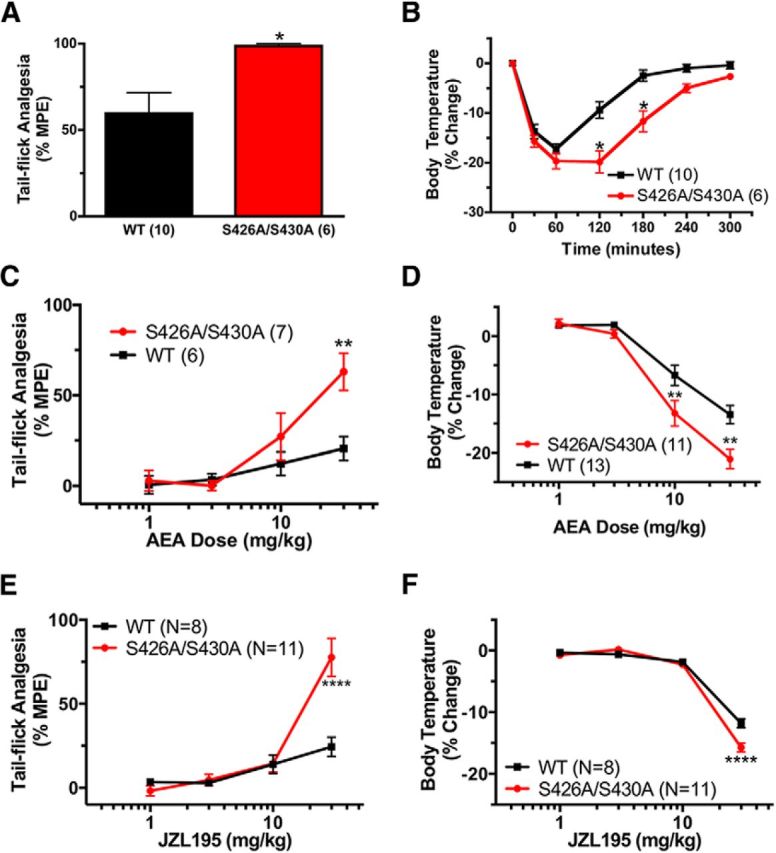

Enhanced response to endocannabinoids

Since the S426A/S430A mice were more sensitive to Δ9-THC, we next determined whether they were more sensitive to endogenous cannabinoids. This was done by intraperitoneal administration of either the endocannabinoid AEA or dual fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) and monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL) inhibitor JZL195 (to increase both AEA and 2-AG levels) to male S426A/S430A mutant and WT littermate mice and then examining antinociception and hypothermia. AEA is rapidly degraded by FAAH (Cravatt et al., 1996, 2001); therefore, mice that received exogenously administered AEA were pretreated with 10 mg/kg URB597 a FAAH inhibitor, to prevent rapid AEA hydrolysis (Fegley et al., 2005). Thirty minutes following URB597 treatment, mice were given 50 mg/kg AEA. S426A/S430A mutants treated with URB597 and AEA exhibited enhanced antinociceptive (Fig. 6A) and hypothermic (Fig. 6B) responses to AEA. Next, dose–response curves for the hypothermic and analgesic effects of 1, 3, 10, and 30 mg/kg AEA were performed in the presence of 10 mg/kg URB597. The antinociceptive response to 30 mg/kg AEA (Fig. 6C) and the hypothermic responses to 10 and 30 mg/kg AEA (Fig. 6D) were enhanced in the S426A/S430A mutant mice. Additionally, the dose–response curves for the antinociceptive (Fig. 6C) and hypothermic (Fig. 6D) effects of AEA were shifted leftward for the S426A/S430A mutant mice. Two-way ANOVA indicated significant main effects of genotype F(1,44) = 6.65; p = 0.0132), interaction (F(3,44) = 2.989; p = 0.0228), and dose (F(3,44) = 12.20; p < 0.0001) on antinociceptive responses to URB597 and AEA (Fig. 6C). There were also significant main effects of genotype (F(1,94) = 12.26; p = 0.0007), interaction (F(3,94) = 2.989; p = 0.0350), and dose (F(3,94) = 76.06; p < 0.0001) on the hypothermic dose response to URB597 and AEA (Fig. 6D). Sensitivity to 2-AG and AEA were also examined using JZL195. The dose–response curves for the antinociceptive and hypothermic responses to JZL195 were also shifted to the left for the S426A/S430A mutant mice (Fig. 6E,F). S426A/S430A mutants exhibited significantly enhanced antinociceptive and hypothermic responses to 30 mg/kg JZL195. Two-way ANOVA indicated the significant main effects of genotype (F(1,67) = 8.675; p = 0.0044), interaction (F(3,67) = 8.919; p < 0.0001), and dose (F(3,67) = 356.3; p < 0.0001) on the hypothermic dose response (Fig. 6F), and the effects of genotype (F(1,67) = 14.20; p = 0.0003), interaction (F(3,67) = 13.44; p < 0.0001), and dose (F(3,67) = 40.62; p < 0.0001) on the antinociceptive dose response for JZL195 (Fig. 6E). The maximal hypothermic and antinociceptive responses to 30 mg/kg JZL195 were increased for the S426A/S430A mutant mice, suggesting increased efficacy for endocannabinoids at the S426A/S430A mutant CB1R.

Figure 6.

S426A/S430A mutants are more sensitive to endocannabinoids. A, B, S426A/S430A mutants (red bars or lines with circles) exhibit increased antinociceptive (A) and hypothermic (B) responses to 50 mg/kg AEA that was administered 30 min after 10 mg/kg URB597 compared with WT mice (black bars or lines with squares). C, D, The dose–response curves for the antinociceptive (C) and hypothermic (D) effects of 10 mg/kg URB597 combined with 1, 3, 10, or 30 mg/kg AEA were shifted to the left in the S426A/S430A mutant mice. E, F, The dose–response curves for the antinociceptive (E) and hypothermic (F) effects of the dual FAAH and MAGL inhibitor JZL195 were also shifted to the left for S426A/S430A mutant mice. Error bars represent the SEM and data analyses were performed using unpaired Student's t test (A) and two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc tests (B–F). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001. Sample sizes for each group are in parentheses.

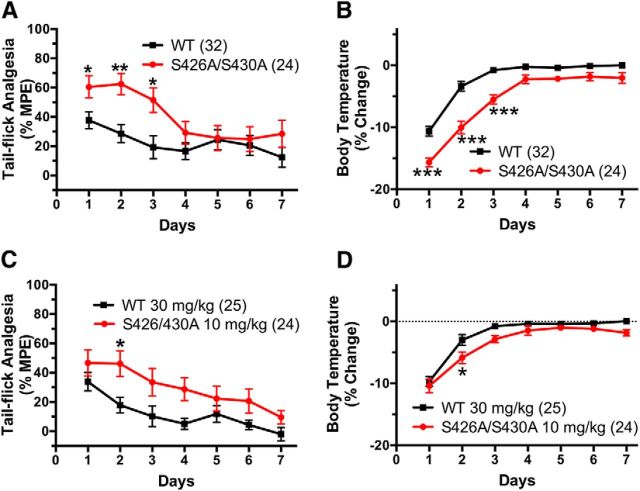

Delayed tolerance to Δ9-THC in S426A/S430A mice

Previous work has suggested that the decrease in agonist-stimulated CB1R activation associated with tolerance is due to CB1R receptor desensitization (Sim-Selley, 2003; Martin et al., 2004; McKinney et al., 2008; Nguyen et al., 2012). Therefore, we hypothesized that tolerance to the hypothermic and antinociceptive effects of cannabinoid agonists are reduced in desensitization-resistant S426A/S430A mice. Indeed, we found that the onset of tolerance to both the antinociceptive and hypothermic effects of 30 mg/kg Δ9-THC was delayed in S426A/S430A mutant mice relative to WT littermate controls (Fig. 7A,B). Two-way ANOVA indicated the significant main effects of genotype (F(1,396) = 23.99; p < 0.0001) and day (F(7,396) = 4.812; p < 0.0001) on tolerance to antinociceptive effects of Δ9-THC (Fig. 7A), and also the effects of genotype (F(1,396) = 114.4; p < 0.0001), interaction (F(7,396) = 4.298; p = 0.0001), and day (F(7,396) = 92.61; p < 0.0001) on tolerance to hypothermic effects of Δ9-THC (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7.

The development of tolerance is delayed in S426A/S430A mutants. A, B, S426A/S430A (red circles and line) and WT (black squares and line) mice were treated (intraperitoneal injection) daily with 30 mg/kg Δ9-THC for 7 d. A, C, Tail-flick antinociception was measured daily at 55 min after administration of Δ9-THC. B, D, Body temperature was measured daily at 60 min following Δ9-THC. C, D, S426A/S430A and WT mice were daily with 10 and 30 mg/kg Δ9-THC, respectively, and tail-flick antinociception and body temperatures were measured as above. Error bars represent the SEM and data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc tests. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Sample sizes for each group are in parentheses.

To determine whether the reduced tolerance to 30 mg/kg Δ9-THC observed in S426A/S430A mutants was merely due to the greater initial response to Δ9-THC in these mutant mice, responses were compared between WT mice treated daily with 30 mg/kg Δ9-THC to those of S426A/S30A mutant mice treated daily with a lower (10 mg/kg) dose of Δ9-THC. We previously determined that these doses of Δ9-THC produced acute antinociceptive and hypothermic responses of equal magnitude in S426A/S430A mutant and WT mice (Fig. 5C,D). In this experiment, S426A/S430A mutants exhibited slower development of tolerance to the antinociceptive effects of 10 mg/kg Δ9-THC relative to WT littermate controls given 30 mg/kg (Fig. 7C). This conclusion is supported by two-way ANOVA, which found significant main effects of genotype (F(1,325) = 24.47; p = 0.0001) and day (F(6,325) = 6.424; p = 0.0001) on tolerance to the antinociceptive effects of these equally active doses of Δ9-THC. Administration of 10 mg/kg Δ9-THC to the S426A/S430A mutants and 30 mg/kg Δ9-THC to WT mice caused equivalent acute hypothermic responses on the first day of drug treatment (Fig. 7D). Tolerance to the hypothermic effects of 10 mg/kg Δ9-THC was also significantly delayed in S426A/S430A mutants (Fig. 7D). Slower development of tolerance to the hypothermic effects of equally active doses of Δ9-THC is supported by two-way ANOVA, which detected significant main effects of genotype (F(1,325) = 17.85; p < 0.0001) and day (F(6,325) = 59.43; p < 0.0001). As an alternative measure of the rate of onset of tolerance, the half-time for hypothermic tolerance was determined by fitting the hypothermia data to a single-phase exponential decay curve. The half-time for the development of tolerance was increased in the S426A/S430A mutants (1.21 d; 95% CI, 0.97–1.60 d) compared with WT mice (0.51 d; 95% CI, 0.39–0.74 d) (data not shown).

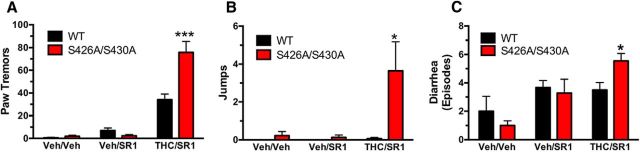

S426A/S430A mice show enhanced cannabinoid dependence

Physical dependence on drugs of abuse is often associated with the onset of somatic and affective withdrawal signs when drug consumption is abruptly discontinued and/or an antagonist is administered and is likely a central mechanism in the development of problem drug use (Koob, 2009). Physical dependence was assessed in S426A/S430A mutant and WT mice treated twice daily with vehicle or 50 mg/kg Δ9-THC for 5.5 d (injected subcutaneiously). Withdrawal was precipitated with an injection of 10 mg/kg rimonabant (SR1) (injected intraperitoneally) and the number of paw tremors, jumps, and diarrhea events were scored. S426A/S430A mutant mice exhibited more withdrawal-induced paw tremors, jumps, and diarrhea events than WT littermates (Fig. 8). In contrast, there were no differences in withdrawal symptoms between the genotypes when mice were treated daily with vehicle and withdrawal was precipitated by either vehicle or rimonabant (Fig. 8). As a negative control, we investigated rimonabant-precipitated withdrawal in CB1R−/− and WT mice. Similar to previous studies, we found no withdrawal symptoms in mice lacking CB1Rs that received Δ9-THC followed by acute rimonabant injection (data not shown). The increased severity of withdrawal symptoms in S426A/S430A mutant mice is consistent with our findings that these mutant mice show elevated acute responses to CB1R agonists and delayed tolerance.

Figure 8.

Δ9-THC dependence is increased in S426A/S430A mutant mice. A–C, Paw tremors (A), jumps (B), and diarrhea (C) were measured in S426A/S430A mutants (red bars) and WT (black bars) littermates to evaluate Δ9-THC dependence. Dependence to Δ9-THC was induced by 5.5 d of twice daily subcutaneous injections of vehicle (veh) or 50 mg/kg Δ9-THC. Withdrawal was precipitated by administering 10 mg/kg rimonabant (SR1). Withdrawal symptoms were scored for the following conditions: Veh/Veh (WT, N = 5; S426A/S430A, N = 8), Veh/SR1 (WT, N = 6; S426A/S430A, N = 8), and SR1/THC (WT, N = 10; S426/S430A; N = 11). *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001. Error bars represent the SEM, and data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc tests.

Discussion

Previous work in transfected cells and oocytes strongly suggests that desensitization of CB1R signaling requires phosphorylation at serine residues 426 and 430 by a GRK and interaction with β-arrestin2 (Jin et al., 1999; Daigle et al., 2008b). To elucidate the role of desensitization by S426 and S430 phosphorylation in the development of tolerance to cannabinoids in vivo, mice expressing the S426A/S430A mutation of CB1R were produced. These mice showed a markedly enhanced response to Δ9-THC and endogenous cannabinoids, increased antagonist-precipitated withdrawal following Δ9-THC treatment, and delayed development of tolerance to Δ9-THC. In this regard, the S426A/S430A mice exhibited some phenotypic similarity to mice lacking β-arrestin2. Deletion of β-arrestin2 enhances agonist-stimulated activation of cannabinoid and opioid receptors by agonists of low-to-moderate intrinsic efficacy, such as morphine and Δ9-THC (Bohn et al., 1999; Breivogel et al., 2008; Nguyen et al., 2012). The enhanced response to Δ9-THC previously observed in β-arrestin2-null mice is striking in its similarity to the increased response to 10 and 30 mg/kg Δ9-THC observed in the S426A/S430A mutant mice. These findings suggest that inhibition of GRK and β-arrestin2-mediated desensitization of the CB1R, either by deletion of β-arrestin2 or by removing two putative GRK phosphorylation sites on the CB1R C terminus, can confer dramatically increased pharmacological responses to Δ9-THC. They also suggest that peak pharmacological responses to at least some agonists are limited by GRK/β-arrestin2-mediated desensitization. S426A/S430A mutant mice also showed exacerbated withdrawal symptoms following Δ9-THC treatment. Administration of inhibitors for the hydrolytic enzymes that metabolize AEA and 2-AG demonstrate that S426A/S430A mutant mice are also more sensitive to endocannabinoids, as do the left-shifted depolarization–response curve for DSE in S426A/S430A autaptic hippocampal neurons.

We found that Δ9-THC dose–response curves for antinociception and hypothermia were shifted to the left in the S426A/S430A mice, suggesting that removal of GRK-mediated desensitization of CB1Rs confers increased the potency for these behavioral effects of cannabinoids. The maximal hypothermic effect of Δ9-THC, a low-efficacy partial agonist for CB1R-mediated G-protein activation, was increased in S426A/S430A mutant mice. However, the maximal antinociceptive effect of Δ9-THC was not increased. Interestingly, we observed a similar increase in maximal hypothermia, but not analgesia, with endocannabinoids in the S426A/S430A mutants. This finding suggests that the S426A/S430A mutation might selectively confer increased efficacy for a subset of endocannabinoid-induced physiological responses. One interpretation is that the increased efficacy for certain physiological responses might be due to differential effects of the S426A/S430A in CNS regions that mediate hypothermia [preoptic hypothalamus (Rawls et al., 2002) vs tail-flick antinociception (PAG, DRG, and spinal cord; Lichtman and Martin, 1991; Lichtman et al., 1996)]. However, the equivalent antinociceptive efficacy between genotypes could also be due to the nature of the tail-flick assay, in which a ceiling effect is imposed by the 10 s cutoff.

Tolerance to Δ9-THC-mediated antinociception was attenuated in β-arrestin2 knock-out (KO) mice that received repeated Δ9-THC treatment (Nguyen et al., 2012). This finding is consistent with our finding that tolerance is delayed in S426A/S430A mutant mice. Furthermore, it suggests that β-arrestin2 interacts with CB1 phosphorylated at serines 426 and 430. Together, the results of these studies indicate that either deletion of β-arrestin2 or mutation of putative GRK phosphorylation sites in the CB1R produces similar attenuation of Δ9-THC tolerance. However, these findings also highlight that mechanisms in addition to GRK/β-arrestin2-mediated desensitization are necessary to produce complete tolerance to Δ9-THC effects in vivo.

CB1R-mediated G-protein activity was assessed by measuring CP55,940-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding in PAG and spinal cord membranes from WT and S426A/S430A mutant mice. Chronic treatment with 30 mg/kg Δ9-THC produced CB1R desensitization in WT mice that was detected as a reduction in CP55,940-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding, whereas CB1R desensitization was not detected in tissue from S426A/S430A mutant mice. This result demonstrates that the S426A/S430A mutation blocks CB1R desensitization in these regions and is consistent with previous studies demonstrating the essential role for these residues in CB1R desensitization in cell culture models. Moreover, previous studies using β-arrestin2 KO mice revealed reduced Δ9-THC-induced desensitization of CB1R-mediated G-protein activation in both PAG and spinal cord (Nguyen et al., 2012). These results are consistent with studies that have shown the important role for GRK and β-arrestin in CB1R desensitization and suggest that this process is mediated by phosphorylation and β-arrestin recruitment at CB1R residues S426 and S430. Interestingly, desensitization of CB1R-mediated G-protein activation following repeated Δ9-THC treatment was reduced in the hippocampus of S426A/S430A mutant mice; however, β-arrestin2 deletion did not inhibit CB1R desensitization in this region (Nguyen et al., 2012). These results suggest that in some CNS regions CB1R phosphorylation at S426/S430 promotes desensitization through a mechanism that is independent of β-arrrestin2 or that other mechanisms downstream of CB1R phosphorylation can compensate for the absence of β-arrrestin2.

We observed CB1R downregulation in spinal cord membranes from WT mice following 7 d of treatment with 30 mg/kg Δ9-THC. In contrast, Δ9-THC treatment did not significantly downregulate CB1Rs in spinal cords from S426A/S430A mice, indicating that mutation of these residues inhibits agonist-induced CB1R downregulation. This finding demonstrates that while phosphorylation of S426 and S430 on the CB1R might not be required for internalization (Hsieh et al., 1999; Jin et al., 1999), they are involved in agonist-induced downregulation of this receptor. This finding also raises the possibility that receptor downregulation might be important for mediating the onset and early phase of tolerance to the hypothermic and antinociceptive effects of Δ9-THC. In agreement with this hypothesis, mice with genetic disruption of G-protein-associated sorting protein 1 (GASP1), which mediates agonist-induced lysosomal trafficking and degradation of CB1Rs, exhibit reduced tolerance to cannabinoid-mediated antinociception in the tail-flick test and lack CB1R downregulation in the spinal cord (Martini et al., 2010). In contrast, GASP1 deletion did not alter tolerance to cannabinoid hypothermia, suggesting that CB1R downregulation might not contribute to hypothermic tolerance. Repeated Δ9-THC treatment also modestly increased the affinity of [3H]CP55,940 for CB1Rs in the spinal cord of S426A/S430A mice. The mechanism underlying this effect is currently unclear, but it was independent of the S426A/S430A mutation, occurring in both knock-in and WT mice. Nonetheless, this finding suggests that Δ9-THC was adequately removed from CB1Rs before assay because residual Δ9-THC in the membrane preparation would have decreased the apparent affinity for [3H]CP55,940.

Δ9-THC dependence develops with repeated administration and can be precipitated by administration of a CB1R antagonist (Tsou et al., 1995). The number of withdrawal-induced paw tremors, jumps, and bowel elimination episodes was increased following administration of rimonabant (SR1) to S426A/S430A mutant mice (Fig. 8). Although jumping and diarrhea occur frequently during precipitated withdrawal from morphine in rodents, these behaviors are rarely observed during cannabinoid withdrawal in mice (Cook et al., 1998; Lichtman et al., 2001; Schlosburg et al., 2009). This finding raises the possibility that β-arrestin2 and GRK phosphorylation of CB1 receptors limits the magnitude of cannabinoid dependence.

In summary, CB1R S426A/S430A mice showed a markedly enhanced response to Δ9-THC and endogenous cannabinoids, increased antagonist-precipitated withdrawal following Δ9-THC treatment, and delayed development of tolerance to Δ9-THC. We suggest that this mouse model provides a novel tool for studying the consequences of enhanced CB1R signaling on endocannabinoid-influenced processes such as metabolism, drug addiction, synaptic plasticity, learning and memory, and emotive behavior. The advantage of this mutant compared with other approaches that enhance endocannabinoid signaling is that it ensures that effects of increased endocannabinoid signaling on behavior and physiology are mediated exclusively by CB1Rs. For example, FAAH inhibition using genetic or pharmacological approaches has the caveat that resulting AEA (and other acyl amides) can act through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α and transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 channels in addition to CB1Rs (Zygmunt et al., 1999; Melis et al., 2008). In contrast, S426A/S430A mutant mice allow the investigation of endocannabinoid-mediated effects directly at CB1Rs. Moreover, the phosphorylation-deficient mutant provides a model to investigate receptor regulation and tolerance after repeated cannabinoid treatment. Finally, our findings in the S426A/S430A mutant mice validate this novel approach of mutating C-terminal GRK phosphorylation sites involved in desensitization as a strategy to investigate enhanced GPCR signaling and mechanisms of GPCRs regulation in vivo.

Footnotes

This work has been supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DA011322, DA021696, DA014277, DA036385, and DA015916. Additional support was provided by the Indiana Academy of Sciences, the Indiana University METACyt Initiative (funded in part by a grant from the Lilly Foundation), and the Linda and Jack Gill Center for Biomolecular Science. We thank G. Stanley McKnight and Richard Palmiter for many helpful discussions; and Thong Su, Courtney Hatheway, Natalie Barker, Alex Hughes, Jordan Cox, Aaron Tomarchio, and Jill Farnsworth for technical assistance.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Bedi G, Foltin RW, Gunderson EW, Rabkin J, Hart CL, Comer SD, Vosburg SK, Haney M. Efficacy and tolerability of high-dose dronabinol maintenance in HIV-positive marijuana smokers: a controlled laboratory study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;212:675–686. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1995-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohn LM, Lefkowitz RJ, Gainetdinov RR, Peppel K, Caron MG, Lin FT. Enhanced morphine analgesia in mice lacking beta-arrestin 2. Science. 1999;286:2495–2498. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5449.2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw HB, Rimmerman N, Krey JF, Walker JM. Sex and hormonal cycle differences in rat brain levels of pain-related cannabimimetic lipid mediators. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291:R349–R358. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00933.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breivogel CS, Lambert JM, Gerfin S, Huffman JW, Razdan RK. Sensitivity to delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol is selectively enhanced in beta-arrestin2 -/- mice. Behav Pharmacol. 2008;19:298–307. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328308f1e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook SA, Lowe JA, Martin BR. CB1 receptor antagonist precipitates withdrawal in mice exposed to Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;285:1150–1156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cravatt BF, Giang DK, Mayfield SP, Boger DL, Lerner RA, Gilula NB. Molecular characterization of an enzyme that degrades neuromodulatory fatty-acid amides. Nature. 1996;384:83–87. doi: 10.1038/384083a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cravatt BF, Demarest K, Patricelli MP, Bracey MH, Giang DK, Martin BR, Lichtman AH. Supersensitivity to anandamide and enhanced endogenous cannabinoid signaling in mice lacking fatty acid amide hydrolase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:9371–9376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161191698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daigle TL, Kwok ML, Mackie K. Regulation of CB1 cannabinoid receptor internalization by a promiscuous phosphorylation-dependent mechanism. J Neurochem. 2008a;106:70–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05336.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daigle TL, Kearn CS, Mackie K. Rapid CB1 cannabinoid receptor desensitization defines the time course of ERK1/2 MAP kinase signaling. Neuropharmacology. 2008b;54:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWire SM, Ahn S, Lefkowitz RJ, Shenoy SK. Beta-arrestins and cell signaling. Annu Rev Physiol. 2007;69:483–510. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.022405.154749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Souza DC, Ranganathan M, Braley G, Gueorguieva R, Zimolo Z, Cooper T, Perry E, Krystal J. Blunted psychotomimetic and amnestic effects of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in frequent users of cannabis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:2505–2516. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fegley D, Gaetani S, Duranti A, Tontini A, Mor M, Tarzia G, Piomelli D. Characterization of the fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibitor cyclohexyl carbamic acid 3′-carbamoyl-biphenyl-3-yl ester (URB597): effects on anandamide and oleoylethanolamide deactivation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;313:352–358. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.078980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gainetdinov RR, Premont RT, Bohn LM, Lefkowitz RJ, Caron MG. Desensitization of G protein-coupled receptors and neuronal functions. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:107–144. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh C, Brown S, Derleth C, Mackie K. Internalization and recycling of the CB1 cannabinoid receptor. J Neurochem. 1999;73:493–501. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0730493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin W, Brown S, Roche JP, Hsieh C, Celver JP, Kovoor A, Chavkin C, Mackie K. Distinct domains of the CB1 cannabinoid receptor mediate desensitization and internalization. J Neurosci. 1999;19:3773–3780. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-10-03773.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF. Neurobiological substrates for the dark side of compulsivity in addiction. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56(Suppl 1):18–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouznetsova M, Kelley B, Shen M, Thayer SA. Desensitization of cannabinoid-mediated presynaptic inhibition of neurotransmission between rat hippocampal neurons in culture. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;61:477–485. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.3.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtman AH, Martin BR. Spinal and supraspinal components of cannabinoid-induced antinociception. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1991;258:517–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtman AH, Cook SA, Martin BR. Investigation of brain sites mediating cannabinoid-induced antinociception in rats: evidence supporting periaqueductal gray involvement. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;276:585–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtman AH, Sheikh SM, Loh HH, Martin BR. Opioid and cannabinoid modulation of precipitated withdrawal in delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol and morphine-dependent mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;298:1007–1014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin BR, Sim-Selley LJ, Selley DE. Signaling pathways involved in the development of cannabinoid tolerance. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:325–330. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martini L, Thompson D, Kharazia V, Whistler JL. Differential regulation of behavioral tolerance to WIN55,212-2 by GASP1. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:1363–1373. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney DL, Cassidy MP, Collier LM, Martin BR, Wiley JL, Selley DE, Sim-Selley LJ. Dose-related differences in the regional pattern of cannabinoid receptor adaptation and in vivo tolerance development to delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;324:664–673. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.130328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melis M, Pillolla G, Luchicchi A, Muntoni AL, Yasar S, Goldberg SR, Pistis M. Endogenous fatty acid ethanolamides suppress nicotine-induced activation of mesolimbic dopamine neurons through nuclear receptors. J Neurosci. 2008;28:13985–13994. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3221-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore CA, Milano SK, Benovic JL. Regulation of receptor trafficking by GRKs and arrestins. Annu Rev Physiol. 2007;69:451–482. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.022405.154712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen PT, Schmid CL, Raehal KM, Selley DE, Bohn LM, Sim-Selley LJ. beta-arrestin2 regulates cannabinoid CB1 receptor signaling and adaptation in a central nervous system region-dependent manner. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71:714–724. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyíri G, Cserép C, Szabadits E, Mackie K, Freund TF. CB1 cannabinoid receptors are enriched in the perisynaptic annulus and on preterminal segments of hippocampal GABAergic axons. Neuroscience. 2005;136:811–822. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawls SM, Cabassa J, Geller EB, Adler MW. CB1 receptors in the preoptic anterior hypothalamus regulate WIN 55212–2 [(4,5-dihydro-2-methyl-4(4-morpholinylmethyl)-1-(1-naphthalenyl-carbonyl)-6H-pyrr olo[3,2,1ij]quinolin-6-one]-induced hypothermia. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;301:963–968. doi: 10.1124/jpet.301.3.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlosburg JE, Carlson BL, Ramesh D, Abdullah RA, Long JZ, Cravatt BF, Lichtman AH. Inhibitors of endocannabinoid-metabolizing enzymes reduce precipitated withdrawal responses in THC-dependent mice. AAPS J. 2009;11:342–352. doi: 10.1208/s12248-009-9110-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim-Selley LJ. Regulation of cannabinoid CB1 receptors in the central nervous system by chronic cannabinoids. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 2003;15:91–119. doi: 10.1615/CritRevNeurobiol.v15.i2.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straiker A, Mackie K. Depolarization-induced suppression of excitation in murine autaptic hippocampal neurones. J Physiol. 2005;569:501–517. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.091918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straiker A, Hu SS, Long JZ, Arnold A, Wager-Miller J, Cravatt BF, Mackie K. Monoacylglycerol lipase limits the duration of endocannabinoid-mediated depolarization-induced suppression of excitation in autaptic hippocampal neurons. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;76:1220–1227. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.059030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straiker A, Wager-Miller J, Hu SS, Blankman JL, Cravatt BF, Mackie K. COX-2 and fatty acid amide hydrolase can regulate the time course of depolarization-induced suppression of excitation. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164:1672–1683. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01486.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straiker A, Wager-Miller J, Mackie K. The CB1 cannabinoid receptor C-terminus regulates receptor desensitization in autaptic hippocampal neurones. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;165:2652–2659. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01743.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsou K, Patrick SL, Walker JM. Physical withdrawal in rats tolerant to delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol precipitated by a cannabinoid receptor antagonist. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;280:R13–R15. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00360-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zygmunt PM, Petersson J, Andersson DA, Chuang H, Sørgård M, Di Marzo V, Julius D, Högestätt ED. Vanilloid receptors on sensory nerves mediate the vasodilator action of anandamide. Nature. 1999;400:452–457. doi: 10.1038/22761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]