Abstract

Rationale: In patients with pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (PAP) syndrome, disruption of granulocyte/macrophage colony–stimulating factor (GM-CSF) signaling is associated with pathogenic surfactant accumulation from impaired clearance in alveolar macrophages.

Objectives: The aim of this study was to overcome these barriers by using monocyte-derived induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells to recapitulate disease-specific and normal macrophages.

Methods: We created iPS cells from two children with hereditary PAP (hPAP) caused by recessive CSF2RAR217X mutations and three normal people, differentiated them into macrophages (hPAP-iPS-Mφs and NL-iPS-Mφs, respectively), and evaluated macrophage functions with and without gene-correction to restore GM-CSF signaling in hPAP-iPS-Mφs.

Measurements and Main Results: Both hPAP and normal iPS cells had human embryonic stem cell–like morphology, expressed pluripotency markers, formed teratomas in vivo, had a normal karyotype, retained and expressed mutant or normal CSF2RA genes, respectively, and could be differentiated into macrophages with the typical morphology and phenotypic markers. Compared with normal, hPAP-iPS-Mφs had impaired GM-CSF receptor signaling and reduced GM-CSF–dependent gene expression, GM-CSF– but not M-CSF–dependent cell proliferation, surfactant clearance, and proinflammatory cytokine secretion. Restoration of GM-CSF receptor signaling corrected the surfactant clearance abnormality in hPAP-iPS-Mφs.

Conclusions: We used patient-specific iPS cells to accurately reproduce the molecular and cellular defects of alveolar macrophages that drive the pathogenesis of PAP in more than 90% of patients. These results demonstrate the critical role of GM-CSF signaling in surfactant homeostasis and PAP pathogenesis in humans and have therapeutic implications for hPAP.

Keywords: alveolar macrophage, receptor, genetic disease, granulocyte-macrophage colony–stimulating factor, surfactant

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Hereditary pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (hPAP) is a pediatric lung disorder of impaired granulocyte-macrophage colony–stimulating factor dependent surfactant clearance by alveolar macrophages for which the pathogenesis is poorly understood and no pharmacologic therapy exists. Poor access to patients because of low disease prevalence and difficulty in the long-term culture of patient-derived primary alveolar macrophages pose significant hurdles to research and therapeutic development for hPAP.

What This Study Adds to the Field

Patient/lung disease–specific (or normal) inducible pluripotent stem (iPS) cells were created, differentiated into macrophages, and evaluated. Results demonstrate that patient-specific, iPS cell–derived macrophages accurately reproduced the molecular and cellular defects of alveolar macrophages that drive the pathogenesis of PAP in more than 90% of patients. Lentiviral-mediated correction of granulocyte-macrophage colony–stimulating factor signaling restored surfactant clearance. Patient iPS cell–derived macrophages faithfully recapitulated the abnormal lung disease–specific phenotype of alveolar macrophages from children with hPAP.

Hereditary pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (hPAP) and autoimmune PAP (aPAP) are myeloid cell diseases with primary pulmonary manifestations from surfactant accumulation caused by impaired alveolar macrophage clearance (1–8). Current therapy for these diseases is whole-lung lavage, an invasive procedure requiring general anesthesia in which one lung is mechanically ventilated while simultaneously filling and draining the other repeatedly and percussing the chest to emulsify and physically remove surfactant (2, 7). Rational pharmacotherapeutic development requires knowledge of the mechanism driving abnormal alveolar surfactant accumulation. Surfactant homeostasis is critical for alveolar stability and maintained by balanced production and clearance in alveoli. Approximately half of alveolar surfactant is cleared in alveolar macrophages under regulatory control of granulocyte-macrophage colony–stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (9). Disruption of GM-CSF signaling by GM-CSF autoantibodies in aPAP or CSF2RA or CSF2RB mutations in hPAP (or by ablation of the genes encoding Csf2 or Csf2rb in mice) causes foamy, lipid-laden alveolar macrophages (due to impaired lipid clearance) and other defects including reduced GM-CSF–dependent gene expression, and impaired functions (e.g., proinflammatory cytokine signaling) (10). GM-CSF receptor dysfunction in hPAP also impairs GM-CSF clearance and phosphorylation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (STAT5) (1, 2, 4, 5). However, the molecular mechanism by which loss of GM-CSF signaling impairs surfactant clearance is unknown.

Limited patient access and difficulty maintaining primary cells in long-term culture are hurdles to research on rare diseases including hPAP. The ability to create induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS cells) (11) and their differentiation into various cell types including macrophages (12) has addressed this challenge. However, despite significant progress (13), the differentiation of cells and engineering of tissues accurately recapitulating the critical mechanisms driving disease pathogenesis remain challenges to realizing the full potential of applying iPS cell technology to the study of lung diseases (14).

In this study, we showed that hPAP patient–specific iPS cell–derived macrophages had phenotypic and functional abnormalities similar to alveolar macrophages from children with hPAP including impaired surfactant clearance and other molecular and functional defects. These effects were mediated by a single point mutation (CSF2RA649C>T) disrupting the GM-CSF receptor. Our results demonstrate the successful use of patient-specific iPS cells to recapitulate the lung disease–specific abnormalities of alveolar macrophages that cause hPAP in children. An abstract of this study was recently presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Thoracic Society (15).

Methods

Normal and hPAP Patient Blood Leukocytes

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated as described (2) from two children with hPAP caused by homozygous-recessive CSF2RA mutations (c.649C>T; p.R217X) and three healthy individuals (NL-1, NL-2, NL-3, respectively) using study protocols approved by the institutional review board of the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. The participants or their parents gave written informed consent. Case histories of the two children with hPAP have been previously reported (subjects B and C of reference [2] are hPAP-1 and hPAP-2, respectively, in this report).

Preparation, Culture, and Characterization of Patient/Lung Disease–specific iPS Cells

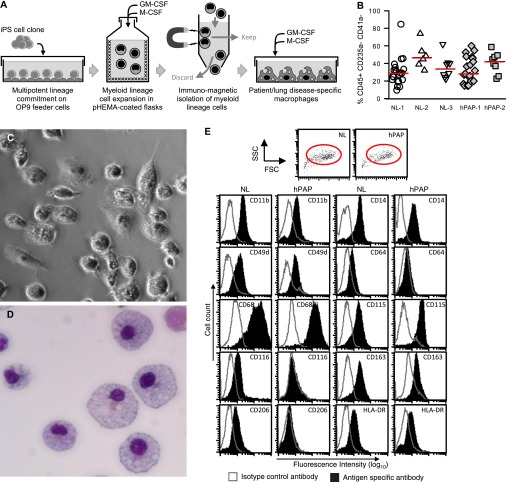

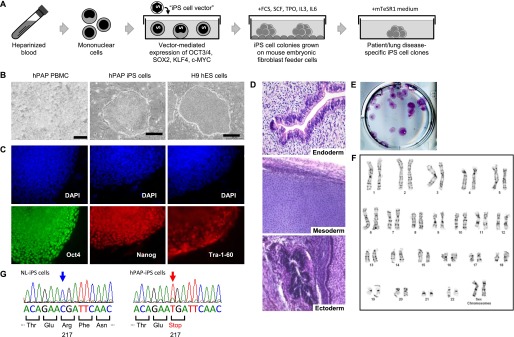

PBMCs were used to develop iPS cell colonies by transduction with a polycistronic lentiviral vector expressing OCT3/4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC as shown (Figure 1A). The creation of iPS cells and their evaluation by routine phase-contrast, immunofluorescence, and light microscopy, clinical karyotyping, teratoma formation, and nucleotide sequencing are described in the online supplement.

Figure 1.

Characterization of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS cells) from hereditary pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (hPAP) and healthy individuals (NL). (A) Generation of patient/lung disease–specific iPS cells. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy individuals or patients with hPAP were transduced to express iPS cell-inducing factors (indicated) and sequentially grown in specialized culture media and then on feeder cells to create cell clones as described in the Methods. Results for one iPS cell clone from a healthy individual (NL-iPS cells) and/or from a patient with hPAP homozygous for CSF2RAR217X mutations (hPAP-iPS cells) are shown. (B) iPS cell colony morphology. hPAP PBMCs, hPAP-iPS cell colonies, and human embryonic stem cell colonies (H9 hES) were examined by phase-contrast microscopy at low power (×10, ×5, ×5, left, center, right, respectively). Bars represent 200, 500, and 500 μm (left, center, and right, respectively). (C) Expression markers of pluripotency. Undifferentiated hPAP-iPS cell colonies were examined by immunofluorescence microscopy to detect protein markers of pluripotency (indicated) or cell nuclei (DAPI) (×20). Immunofluorescence analysis of NL-iPS cell colonies (not shown) was similar to that of hPAP-iPS cell colonies. (D) Teratoma formation assay analysis. Undifferentiated hPAP-iPS cell colonies were injected into immunodeficient mice permitting the formation of iPS cell–derived tumors, which were then removed and examined histopathologically. The pluripotency of the hPAP-iPS cells was confirmed by the formation of teratoma containing tissue elements derived from all three germ layers including respiratory epithelium (endoderm), cartilage (mesoderm), and neural epithelium (ectoderm) (hematoxylin and eosin). (E) Alkaline phosphatase activity. Undifferentiated hPAP-iPS cell colonies were evaluated for alkaline phosphatase, a pluripotent cell marker, by routine histochemical methods as described in the Methods. One 35-mm-diameter well containing multiple positively stained hPAP-iPS cell colonies is shown. Histochemical analysis of NL-iPS cell colonies (not shown) was similar to that of hPAP-iPS cell colonies. (F) Karyotype analysis. Undifferentiated hPAP-iPS cell colonies were evaluated by routine clinical karyotyping analysis, which confirmed a normal complement of morphologically normal-appearing chromosomes. (G) CSF2RA gene nucleotide sequencing. Routine polymerase chain reaction–based nucleotide sequencing of genomic DNA confirmed homozygous normal or R217X sequences for the CSF2RA gene in NL-iPS cell and hPAP-iPS cell colonies, respectively.

Preparation of iPS Cell–derived Macrophages

Directed differentiation of iPS cells into macrophages was achieved by coculture on mouse bone marrow stromal cells as described (16) with minor modifications as shown (Figure 2A) and described in detail in the online supplement.

Figure 2.

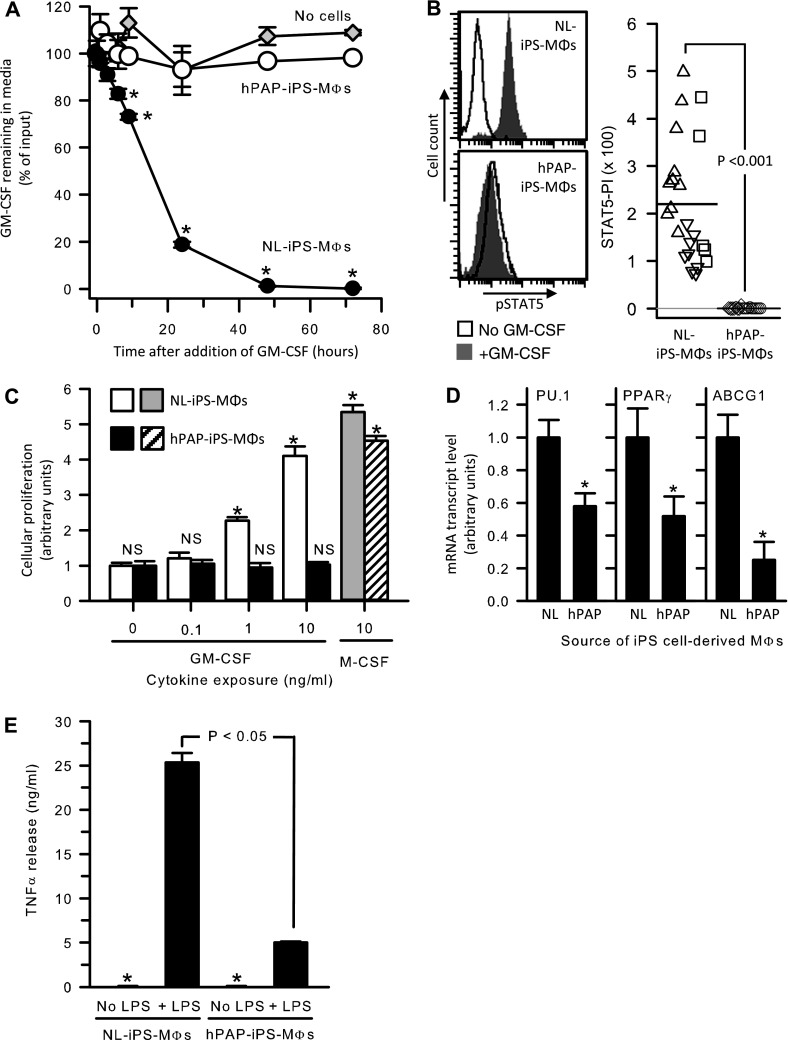

Directed differentiation of macrophages from hereditary pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (hPAP) induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS cells) and iPS cell clones from healthy individuals (NL). Undifferentiated hPAP-iPS or NL-iPS cell colonies were differentiated into macrophages (hPAP-iPS-Mφs or NL-iPS-Mφs, respectively) as described in the Methods and the online supplement. (A) Generation of iPS cell–derived macrophages. Independent iPS cell clones were cultured on OP9 mouse bone marrow stromal feeder cells to direct multipotent lineage commitment and expanded in suspension culture in media containing macrophage colony–stimulating factor (M-CSF) and granulocyte-macrophage colony–stimulating factor (GM-CSF) to expand myeloid lineage cells. Immunomagnetic separation was used to isolate CD45+/CD235a−/CD41a− macrophage precursors, which were expanded and differentiated in media containing M-CSF and GM-CSF. (B) Evaluation of the myeloid cell expansion efficiency. The efficiency of myeloid lineage cell expansion from iPS cells was evaluated for iPS cell clones from three different healthy individuals (NL-1, -2, -3) and two patients with hPAP (hPAP-1, -2) by measuring the percentage of CD45+/CD235a−/CD41a− cells. Each symbol indicates a separate determination. (C) Morphology of live hPAP-iPS cell-derived macrophages. Cells were examined by phase-contrast microscopy (original photomicrograph ×20). (D) Morphology of sedimented hPAP-iPS cell–derived macrophages. Cells were sedimented onto slides (Cytospin), stained (Diff-Quick), and examined by light microscopy (original photomicrograph ×20). (E). Phenotypic marker analysis. Cells were immunostained with specific antibodies to various phenotypic markers (shaded histograms) or isotype control antibodies (clear histograms) as indicated and evaluated by flow cytometry as described in the Methods. Shown is gating strategy (red ovals in top panels) used and phenotypic assessment (lower panels) for one normal (NL-1) and one hPAP (hPAP-1) clone. The percentage (±SEM) of differentiated macrophages that were CD68+ was 98 ± 0.8% for all clones evaluated (NL-1, -2, -3, and hPAP-1, -2). Additional results for NL-2, NL-3, and hPAP-2 are included in Figure E3.

Functional Evaluation of Normal and hPAP Patient iPS Cell–derived Macrophages

Cell morphology was assessed by phase-contrast and light microscopy. Immunophenotyping was done by flow cytometry on a BD FACSCalibur (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA) and analyzed using BD CellQuest Pro software. Measurement of macrophage mRNA transcript levels (by polymerase chain reaction amplification), cell-based receptor-mediated GM-CSF clearance, and GM-CSF–mediated intracellular phosphorylation of STAT5 were done as previously reported (1, 2, 4). Cytokine-stimulated cellular proliferation was measured by culturing cells (2.5 × 104 per well) for 72 hours in serum-free medium (Macrophage-SFM; Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) with or without added human GM-CSF or M-CSF using an XTT assay (Cell Proliferation Kit II; Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) with results expressed as the fold-increase in absorbance for cells cultured without added cytokine. Proinflammatory cytokine secretion capacity was measured after culturing cells (as above for the proliferation assay) in the absence or presence of LPS (Escherichia coli 055:B5 Sigma, 100 ng/ml) for 24 hours and then measuring tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α released into the media using ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). To measure intracellular lipid accumulation, cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium with 10% fetal bovine serum, 10 ng/ml GM-CSF, and 25 ng/ml M-CSF with patient’s surfactant material from bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (whole-lung lavage) in a 20:1 (vol/vol) ratio in 12-well plates. Cytospin slides were prepared from cells without surfactant loading, immediately after loading, and 24 hours after careful washing, and stained with oil red O.

Lentiviral Vector–mediated Restoration of GM-CSF Signaling in hPAP-iPS Cells

A lentiviral vector carrying the cDNA for CSF2RA (LV-hCSF2RA) was used to express the normal human GM-CSF receptor α in hPAP-iPS-Mφs as described in the online supplement.

Statistical Analysis

Numeric data were evaluated for normality and equal variance using the Shapiro-Wilk and Levene median tests, respectively, and presented as the mean ± standard error (parametric data), or median and interquartile range (nonparametric data). Statistical comparisons were made with Student t test, one-way analysis of variance, and Mann-Whitney rank sum test as appropriate; P values less than 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. Analysis was performed using SigmaPlot software (version 12; Systat Software, San Jose, CA). All experiments were repeated at least three times, with similar results.

Online Supplement

Additional details regarding participants, other data, and methods cited throughout the text can be found in the online supplement.

Results

Generation of Patient-Specific and Normal iPS Cells

To create iPS cells, PBMCs from two children with hPAP caused by CSF2RAR217X mutations and three unrelated healthy people were transduced with a lentiviral vector expressing OCT3/4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC (Figure 1A). In total, 18 independent iPS cell clones were derived from two patients with hPAP (12 from hPAP-1, 6 from hPAP-2), and 22 independent iPS cell clones were derived from three healthy people (13 from NL-1, 5 from NL-2, 4 from NL-3) and are referred to as hPAP-iPS or NL-iPS cells, respectively, in this report. Colonies of hPAP-iPS and NL-iPS cells were morphologically indistinguishable from each other or human embryonic stem cell colonies (Figure 1B; see Figure E1 in the online supplement). Both hPAP-iPS and NL-iPS cells expressed pluripotency markers (Oct4, Nanog, and Tra-1–60) (Figure 1C), alkaline phosphatase (Figure 1E), and formed teratomas containing tissues derived from all three germ cell layers (Figure 1D; see Figure E1). Both hPAP-iPS and NL-iPS cells had a normal karyotype (Figure 1F; see Figure E2). Nucleotide sequencing confirmed homozygous CSF2RA mutations in hPAP-iPS cells identical to the mutations identified in these patients and a normal CSF2RA sequence in NL-iPS cells (Figure 1G). These results demonstrate pluripotency, chromosomal stability, and preservation of the genetic identity of hPAP patient and normal iPS cells generated from human PBMCs.

Directed Differentiation of iPS Cells into Macrophages

To reproduce the molecular defects in the cells driving the pathogenesis of hPAP (i.e., alveolar macrophages), iPS cell clones were induced to hematopoietic lineage commitment, expanded in number, and differentiated as described (16) except that both GM-CSF and M-CSF were included in the medium during myeloid expansion and macrophage culture steps (Figure 2A). This modification was made to promote hPAP patient–derived myeloid lineage growth because in preliminary studies using the reported method (16), patient-derived myeloid cells expanded poorly after iPS cell/OP9 coculture when only GM-CSF was included (not shown). However, in the presence of both M-CSF and GM-CSF, the efficiency of myeloid cell expansion from both patient-derived and normal iPS cell lines was similar as demonstrated by quantifying CD45+/CD235a−/CD41a− cells (Figure 2B). hPAP-iPS cell–derived macrophages (hPAP-iPS-Mφs) had typical macrophage morphology including a rounded shape (Figure 2C; see Figure E3) and high cytoplasm-to-nuclear ratio (Figure 2D). NL-iPS cell–derived macrophages were similar by phase contrast (see Figure E3) and light microscopy (not shown). The proliferative capacity of iPS-derived macrophages lasted for approximately 1 week, whereas their morphologic appearance was maintained for at least 1 month by changing the media every 4–6 days. The normal morphology of hPAP-iPS-Mφs indicates that the foamy appearance of alveolar macrophages in PAP is not an intrinsic consequence of GM-CSF signaling deficiency but rather is more likely a consequence of lipid accumulation from constant exposure to surfactant lipids in the context of impaired clearance capacity. This is consistent with morphologically normal macrophages in other tissues in mice and humans with PAP caused by disruption of GM-CSF signaling.

Molecular and Functional Characterization of iPS Cell–derived Macrophages

To define the phenotype of iPS cell–derived macrophages, cell surface marker analysis was done as previously reported for patients with PAP (17). Markers present on mature macrophages (e.g., CD11b, CD14, CD49d, CD64, CD68, CD115, CD116, CD163, CD206, HLA-DR) were detected on NL-iPS-Mφs from all three normal individuals (Figure 2E; see Figure E3C). In contrast, CD116 and CD206 were absent; CD49d, CD64, CD163, CD11b, CD14, and HLA-DR were markedly reduced; and CD68 and CD115 were unchanged in hPAP-iPS-Mφs compared with NL-iPS-Mφs (Figure 2E; see Figure E3C). Minor variation was noted for some (CD11b, CD115, CD116) but not other (CD14, CD49d, CD64, CD68, CD163, CD206, HLA-DR) markers among NL-iPS-Mφs from different healthy individuals (NL-1, NL-2, NL-3) (compare Figure 2E with Figure E3C). In hPAP-iPS-Mφs, the reduction in levels of some (CD11b, CD14, HLA-DR) showed minimal variability, whereas the others were consistently reduced or absent (compare Figure 2E with Figure E3C).

GM-CSF receptor function was evaluated by measuring GM-CSF clearance and GM-CSF–dependent STAT5 phosphorylation as we reported in patients with PAP (1, 2, 4). Compared with NL-iPS-Mφs that rapidly cleared GM-CSF from the cell culture media, hPAP-iPS-Mφs did not clear GM-CSF even after 48 hours (98.8 ± 0.2% vs. 3.3 ± 1.0%, respectively) (Figure 3A). These results are similar to data for primary cells from patients with hPAP and for human embryonic kidney 293 cells expressing cloned normal or mutant CSF2RA/CSF2RB (1, 2, 4). GM-CSF markedly increased phosphorylated STAT5 levels in NL-iPS-Mφs but not in hPAP-iPS-Mφs (Figure 3B). These results indicate that NL-iPS-Mφs and hPAP-iPS-Mφs expressed functional and dysfunctional GM-CSF receptors, respectively.

Figure 3.

Granulocyte-macrophage colony–stimulating factor (GM-CSF) receptor function in hereditary pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (hPAP) induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS cells) and healthy individuals (NL)–iPS cell–derived macrophages. (A) Cell/receptor-mediated GM-CSF clearance. GM-CSF was added at time zero to the media of culture dishes containing NL-iPS-Mφs (closed circles), hPAP-iPS-Mφs (open circles) or media without cells (gray diamonds). At subsequent times, GM-CSF in the culture media was measured by ELISA and the amount remaining was compared with the initial concentration. Using analysis of variance, subsequent values differing significantly from initial values are indicated (*P < 0.001). (B) Receptor-mediated signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (STAT5) phosphorylation. NL-iPS-Mφs or hPAP-iPS-Mφs were incubated for 30 minutes with or without 10 ng/ml GM-CSF as indicated and then phosphorylated STAT5 immunostaining and flow cytometry were used to measure the STAT5 phosphorylation index (STAT5-PI) as described in the Methods. Each symbol indicates a separate expansion of iPS cell–derived Mφs from one clone from one of the three normal individuals and two patients with hPAP (different symbol types represent results for cells from each individual; NL = upright triangles, downward triangles, squares; hPAP = circles, diamonds). (C) CSF-stimulated cellular proliferation. NL-iPS-Mφs or hPAP-iPS-Mφs were cultured with or without GM-CSF or M-CSF at the indicated concentrations for 72 hours and then cellular proliferation was measured by the XTT assay as described in the Methods. Bars represent the mean (±SEM) of four determinations on one clone each from NL-1 and hPAP-1. The cellular proliferation rate at various CSF concentrations was compared with that of unexposed cells by analysis of variance; values differing significantly are indicated (*P < 0.001). (D) Gene expression in hPAP-iPS-Mφs and NL-iPS-Mφs. Levels of mRNA transcript for several key genes regulated by GM-CSF in macrophages were measured in total RNA from NL-iPS-Mφs (NL) or hPAP-iPS-Mφs (hPAP) after conversion to cDNA by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction as described in the Methods. Transcript levels were normalized to the mean value in NL-iPS-Mφs for each gene. Bars represent the mean (±SEM) of four determinations on one clone each from NL-1 and hPAP-1. Comparisons between hPAP-iPS-Mφs and NL-iPS-Mφs were made using Student t test; values differing significantly are indicated (*P < 0.05). (E) Host defense-related proinflammatory signaling by hPAP-iPS-Mφs and NL-iPS-Mφs. NL-iPS-Mφs or hPAP-iPS-Mφs were cultured with or without LPS (100 ng/ml) for 24 hours and then tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α released into the medium was measured by ELISA. Bars represent the mean (±SEM) of four determinations on one clone each from NL-1 and hPAP-1. TNF-α levels in unstimulated cells (*) were minimal (90.90 ± 8.56 and 58.58 ± 22.14 pg/ml in NL- and hPAP-iPS-Mφs, respectively). LPS stimulated TNF-α release was markedly reduced in hPAP-iPS-Mφs compared with NL-iPS-Mφs (Mann-Whitney rank sum test, P < 0.05).

Because M-CSF and GM-CSF receptors mediate the proliferation of normal macrophages (18), we measured the effects of both on iPS cell–derived macrophages. GM-CSF stimulated a dose-dependent proliferation of NL-iPS-Mφs but no change in hPAP-iPS-Mφs (Figure 3C). In contrast, M-CSF stimulated proliferation of NL-iPS-Mφs and hPAP-iPS-Mφs (Figure 3C). Thus, the disruption of receptor function in hPAP-iPS-Mφs is cytokine specific.

GM-CSF regulates multiple genes of critical functional importance in alveolar macrophages including SPI1 (encoding PU.1, a transcription factor regulating macrophage differentiation), PPARγ (a transcription factor important in lipid metabolism), and ABCG1 (a transporter important for export of neutral lipids from macrophages) (19–22). In humans, nonhuman primates, and mice, disruption of GM-CSF signaling reduces mRNA for each gene (8, 20–23). Compared with NL-iPS-Mφs, mRNA for all three genes was reduced in hPAP-iPS-Mφs by 42.1, 48.1, and 74.9%, respectively (Figure 3D). Because GM-CSF also regulates genes determining proinflammatory signaling in alveolar macrophages (8, 19, 21), we measured endotoxin-stimulated TNF-α release. Compared with NL-iPS-Mφs, hPAP-iPS-Mφs had markedly reduced TNF-α release (25.4 ± 1.0 vs. 5.0 ± 0.1 ng/ml at 24 h) (Figure 3E). These results indicate that hPAP-iPS-Mφs recapitulate the same pattern of abnormal GM-CSF–dependent gene expression and impaired cytokine signaling that occurs as a consequence of disrupting GM-CSF signaling in multiple species.

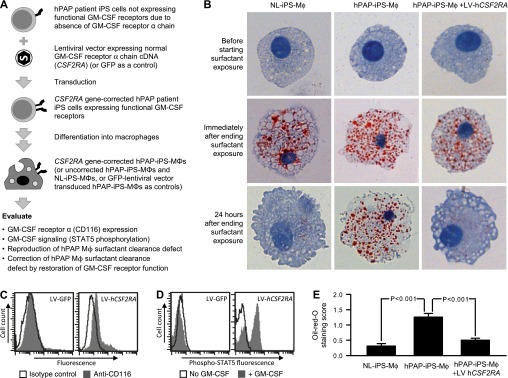

To test the hypothesis that the development of foamy alveolar macrophages in PAP is caused by impaired GM-CSF–dependent surfactant clearance in the context of unimpaired uptake and ongoing surfactant exposure, iPS cell–derived macrophages were exposed to pulmonary surfactant from the lungs of patients with PAP (Figures 4A and 4B). As expected, both NL-iPS-Mφs and hPAP-iPS-Mφs readily internalized pulmonary surfactant as shown by intense oil red O staining (Figure 4B, left and middle; see Figure E4A). Importantly, 24 hours after discontinuing surfactant exposure, oil red O staining was negligible in NL-iPS-Mφs but remained abundant in hPAP-iPS-Mφs (Figure 4B, lower left and middle). To confirm that impaired pulmonary surfactant clearance was caused by disruption of GM-CSF signaling in hPAP-iPS-Mφs, GM-CSF receptor α expression was restored by transduction with LV-hCSF2RA, followed by directed differentiation into gene-corrected macrophages (Figure 4A). Gene-corrected hPAP-iPS-Mφs had detectable cell-surface GM-CSF receptor α (Figure 4C) and GM-CSF–stimulated STAT5 phosphorylation (Figure 4D) in contrast to control (GFP) vector transduced cells for which both assays were negative. Importantly, pulmonary surfactant clearance was restored in gene-corrected hPAP-iPS-Mφs as demonstrated by minimal oil red O staining 24 hours after surfactant exposure (Figure 4B, lower right; see Figure E4A). Measurement of the oil red O staining score revealed a marked increase in lipid accumulation in hPAP-iPS-Mφs (Figure 4E; see Figure E4B), and that gene-correction normalized this defect (Figure 4E; see Figure E4B). These results demonstrate that disruption of GM-CSF signaling to macrophages directly causes impaired clearance of pulmonary surfactant.

Figure 4.

Impaired pulmonary surfactant clearance in hereditary pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (hPAP) induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS cells) Mφs and correction by gene transfer-mediated restoration of granulocyte-macrophage colony–stimulating factor (GM-CSF) receptor function. (A) Schematic of evaluation of cells before and after correction of GM-CSF signaling. Lentiviral-mediated transfer of the normal CSF2RA cDNA expressing the GM-CSF receptor α into hPAP-iPS cells was performed as described in the Methods and the gene-corrected cells (or uncorrected hPAP-iPS cells or NL-iPS cells) were differentiated into macrophages as shown in Figure 2 and evaluated as indicated. (B) Oil red O staining of iPS cell–derived macrophages. NL-iPS-Mφs, hPAP-iPS-Mφs, or gene-corrected hPAP-iPS-Mφs (hPAP-iPS-Mφs+LV-hCSF2RA) (top panels) were exposed to surfactant for 24 hours (middle panels) and then washed with phosphate-buffered saline and cultured 24 hours more in the absence of surfactant (lower panels). Cells were sedimented onto slides (Cytospin), stained (oil red O) and examined by light microscopy and photographed. (C) Evaluation of CD116 on gene-corrected hPAP-iPS-Mφs. Cells were immunostained with anti-human CD116 antibodies (shaded) or isotype control antibodies (open) and cell surface CD116 levels were evaluated by measuring fluorescence by flow cytometry. LV-GFP and LV-hCSF2RA indicate control and hCSF2RA vectors, respectively. (D) GM-CSF receptor-signaling in gene-corrected hPAP-iPS-Mφs. Cells were incubated for 30 minutes with or without 10 ng/ml GM-CSF, immunostained with anti–phospho–signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (STAT5) specific antibody, and then intracellular phospho-STAT5 levels were measured by flow cytometry as described in the Methods. (E) Measurement of lipid accumulation in iPS cell–derived macrophages. Macrophages were cultured in the presence and then absence of surfactant followed by washing and staining with oil red O as described (Figure 4B) and evaluated by light microscopy using a visual grading scale (the oil red O staining index) to measure the degree of staining as previously described (8). Bars represent the mean (±SEM) oil red O staining score for 10 high-power fields for one clone each from NL-1 and hPAP-1. Results shown are from one of three representative experiments with these clones. Similar results were obtained in three experiments with additional clones (see Figure E4).

Discussion

We created PBMC-derived iPS cells from two children with hPAP and three healthy individuals; directed iPS cell differentiation into macrophages; and then evaluated macrophage phenotypic markers, GM-CSF signaling, and macrophage functions. Patient iPS cell–derived macrophages proliferated well in response to M-CSF but had impaired GM-CSF clearance, altered cell-surface markers, reduced GM-CSF–dependent gene expression, impaired proinflammatory cytokine signaling, and impaired surfactant clearance compared with iPS cell–derived macrophages from healthy control subjects. Furthermore, restoration of GM-CSF signaling corrected surfactant clearance in iPS cell–derived macrophages from both patients with hPAP. The abnormalities observed are similar to those of primary alveolar macrophages from humans, nonhuman primates, and mice with PAP caused by GM-CSF signaling disruption (8, 9, 22). Thus, our study successfully addresses an important hurdle for the use of iPS cells to study lung diseases: faithful recapitulation of the pathogenic molecular and cellular abnormalities in the lung cells that drive disease pathogenesis (14).

Implications for PAP Pathogenesis

The iPS cells developed here comprise new tools to study human macrophages in health and disease. The observation that hPAP-iPS-Mφs accurately reproduced the abnormalities seen in alveolar macrophages from patients with PAP (and Csf2rb-deficient mice) is an important finding because recent reports identify alveolar macrophages as the lung cell in which loss of GM-CSF signaling drives pathogenesis in aPAP and hPAP (1, 2, 7, 8, 24–26). Furthermore, that the GM-CSF receptor-deficient iPS cells could not be differentiated into functionally normal macrophages supports the concept that GM-CSF is required for terminal differentiation of macrophages in humans as in mice (21). This hypothesis is also supported by our report that human alveolar macrophages require GM-CSF for expression of PU.1, a master transcriptional regulator of macrophage terminal differentiation (23). The observation that hPAP-iPS-Mφs had reduced ABCG1 expression and increased oil red O staining (a marker of neutral lipid accumulation) suggests the specific physiologic defect in alveolar macrophages in PAP may not be impaired catabolism of surfactant as suggested (27) but, rather, reduced cholesterol export as seen in ABCG1-deficient mice (28). Further studies should help elucidate the mechanism of abnormal lipid handling central to PAP pathogenesis. The observation that hPAP-iPS-Mφs developed a foamy appearance only after exposure to surfactant suggests that hPAP-iPS-Mφs can be used to study primary abnormalities caused by disruption of GM-CSF signaling independent of the confounding secondary abnormalities that arise because of being stuffed with surfactant (7).

The observation that hPAP and NL iPS cell–derived Mφs proliferated in response to M-CSF but only the latter proliferated in response to GM-CSF has implications for the presence of alveolar macrophages in individuals with PAP caused by disruption of GM-CSF signaling (e.g., aPAP and hPAP). Pulmonary levels of M-CSF are increased in these patients compared with healthy people (1, 7) (and in mice deficient in GM-CSF or its receptor compared with control animals [1]) and measurement of M-CSF in bronchoalveolar lavage is a useful biomarker (10). Notwithstanding, the biologic significance of increased M-CSF in PAP has not been established. In the context of these prior observations, our data suggest that increased pulmonary M-CSF comprises a compensatory molecular mechanism for alveolar macrophage survival in the absence of GM-CSF signaling. Further studies of these iPS-derived Mφs should be helpful in delineating the functional overlap of these two important myeloid cytokines in regulation of macrophages in health and disease. However, the requirement of M-CSF for expanding hPAP-iPS-Mφs places limitations on the methods that can be used to generate these cells and on interpretation of data from experiments with them. Importantly, expansion of myeloid lineage cells from both hPAP and NL iPS cell clones was similar as determined by measurement of CD45+/CD235a−/CD41a− cells in multiple experiments. Furthermore, another group has reported the successful use of both GM-CSF and M-CSF in expanding macrophages from iPS cells (29).

The potential to develop other lung cell types from these iPS cells has implications for research on surfactant homeostasis. For example, although disruption of GM-CSF signaling is necessary for hPAP, another factor is important in determining disease severity (2). By directing differentiation of hPAP- and NL-iPS cells into other types of respiratory cells and studying them or mixed cultures of iPS cell–derived macrophages and epithelial cells, it may be possible to elucidate mechanisms regulating the rate of production, recycling, and/or clearance of surfactant and the potential effects caused by disruption of GM-CSF signaling. The recent development of methods to direct differentiation of pluripotent stem cells into respiratory cells and tissues supports such an approach (30, 31).

Implications for Pharmacotherapy of hPAP

The observation that lentiviral vector–mediated, unregulated, constitutive expression of a cDNA encoding the normal GM-CSF receptor α restored normal GM-CSF signaling and simultaneously rescued the key pathogenic driver of hPAP (i.e., impaired surfactant clearance in macrophages) supports the use of hPAP-iPS-Mφs in developing gene therapy of hPAP at several levels. First, they have practical use in preclinical studies to evaluate the efficacy and safety of lentiviral vector–mediated restoration of GM-CSF signaling to patient-derived myeloid cells. Indeed, such studies are underway (32). Second, the gene-corrected, autologous hPAP-iPS-Mφs could be used as therapy directly, for example as we have done in Csf2rb-deficient mice using bone marrow transplantation with gene-corrected macrophages (33). An interesting alternative delivery approach is pulmonary macrophage transplantation of mature macrophages, which we have recently demonstrated is highly efficacious as therapy of hPAP in Csf2rb-deficient mice (34, 35). The rationale for therapeutic pulmonary macrophage transplantation is supported by fate mapping studies reporting that alveolar macrophages (and other tissue-resident macrophage populations) are established before birth and maintained in steady state throughout life independent of replenishment by blood monocytes (36, 37). This therapeutic approach of using pulmonary macrophage transplantation with gene-corrected or normal iPS cell–derived macrophages can be tested using a recently established murine PAP model in which human GM-CSF and IL-3 were “knocked in” to their corresponding loci in mice also harboring Rag2 and IL-2Rγ “knock out” mutations (C;129S4-Rag2tm1.1FlvCsf2/ll3tm1.1(CSF2,IL3)Flv/Il2rgtm1.1Flv/J) that permit xenograft transplantation of human cells (38). PAP develops because human and murine GM-CSF does not cross-react functionally. Although the method we used to create iPS cells (11) is relatively efficient, from the therapeutic product development perspective, use of a lentiviral vector to express the reprogramming factors has limitations. First, lentiviral vector integration increases the risk of insertional mutagenesis and cancer development. Second, although the integrated transgenes are silenced during reprogramming, reactivation can occur and result in tumor formation (39). Such concerns have spurred the development of alternative methods for creating human iPS cells including nonviral expression of the required factors using plasmids (40), DNA minicircles (41), Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen–based episomes (42), or synthetic mRNA (43). The recent description of a method for reprogramming mouse cells using only small molecules (44) suggests that it may be feasible to generate human iPS cells with more favorable safety profiles for use in regenerative medicine.

Patient-specific iPS-Mφs might also be useful in future studies to identify small molecule therapies. For example, they could be used in high-throughput screening studies to identify novel medicinal compounds capable of modulating GM-CSF signaling or evaluating the therapeutic potential of currently approved drugs as recently done successfully for a patient with a genetic cardiac disorder (45). Future applications might also include organ- and cell-type specific safety evaluations (i.e., hepatotoxicity, cardiotoxicity studies), or for patient-specific (customized) therapy to identify the optimal therapeutic regime.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Patricia Fulkerson, Division of Allergy and Immunology, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, and Igor Slukvin, University of Wisconsin-Madison, for providing the OP9 feeder cells; James Wells, Division of Developmental Biology, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, for helpful discussions during the course of these studies; and the Pluripotent Stem Cell Facility for help in generating and characterizing induced pluripotent stem cells.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants 1R21HL106134 and 2R01HL085453 (B.C.T.) and 1 ULRR026314 (T.S.) and by the Division of Pulmonary Biology, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Flow cytometric data were acquired using equipment maintained by the Research Flow Cytometry Core in the Division of Rheumatology at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, supported in part by NIH AR-47363, NIH DK78392, and NIH DK90971.

Author Contributions: T.S., study concept and design, data acquisition and analysis, manuscript preparation. C.M., development of iPS cells, manuscript preparation. A.S. and C.C., data acquisition, manuscript preparation. B.C.C., coordination of clinical research, manuscript preparation. P.M., development of lentiviral vector, manuscript preparation. R.E.W., clinical care of study participants, manuscript preparation. B.C.T., study design, data analysis, manuscript preparation.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201306-1039OC on November 26, 2013

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Suzuki T, Sakagami T, Rubin BK, Nogee LM, Wood RE, Zimmerman SL, Smolarek T, Dishop MK, Wert SE, Whitsett JA, et al. Familial pulmonary alveolar proteinosis caused by mutations in CSF2RA. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2703–2710. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suzuki T, Sakagami T, Young LR, Carey BC, Wood RE, Luisetti M, Wert SE, Rubin BK, Kevill K, Chalk C, et al. Hereditary pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: pathogenesis, presentation, diagnosis, and therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:1292–1304. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201002-0271OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinez-Moczygemba M, Doan ML, Elidemir O, Fan LL, Cheung SW, Lei JT, Moore JP, Tavana G, Lewis LR, Zhu Y, et al. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis caused by deletion of the GM-CSFRalpha gene in the X chromosome pseudoautosomal region 1. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2711–2716. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suzuki T, Maranda B, Sakagami T, Catellier P, Couture CY, Carey BC, Chalk C, Trapnell BC. Hereditary pulmonary alveolar proteinosis caused by recessive CSF2RB mutations. Eur Respir J. 2011;37:201–204. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00090610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanaka T, Motoi N, Tsuchihashi Y, Tazawa R, Kaneko C, Nei T, Yamamoto T, Hayashi T, Tagawa T, Nagayasu T, et al. Adult-onset hereditary pulmonary alveolar proteinosis caused by a single-base deletion in CSF2RB. J Med Genet. 2011;48:205–209. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2010.082586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kitamura T, Tanaka N, Watanabe J, Uchida, Kanegasaki S, Yamada Y, Nakata K. Idiopathic pulmonary alveolar proteinosis as an autoimmune disease with neutralizing antibody against granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J Exp Med. 1999;190:875–880. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.6.875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trapnell BC, Whitsett JA, Nakata K. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2527–2539. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra023226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakagami T, Beck D, Uchida K, Suzuki T, Carey BC, Nakata K, Keller G, Wood RE, Wert SE, Ikegami M, et al. Patient-derived granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor autoantibodies reproduce pulmonary alveolar proteinosis in non-human primates. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:49–61. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201001-0008OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trapnell BC, Whitsett JA. GM-CSF regulates pulmonary surfactant homeostasis and alveolar macrophage-mediated innate host defense. Annu Rev Physiol. 2002;64:775–802. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.090601.113847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carey B, Trapnell BC. The molecular basis of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Clin Immunol. 2010;135:223–235. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2010.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park IH, Arora N, Huo H, Maherali N, Ahfeldt T, Shimamura A, Lensch MW, Cowan C, Hochedlinger K, Daley GQ. Disease-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell. 2008;134:877–886. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Somers A, Jean JC, Sommer CA, Omari A, Ford CC, Mills JA, Ying L, Sommer AG, Jean JM, Smith BW, et al. Generation of transgene-free lung disease-specific human induced pluripotent stem cells using a single excisable lentiviral stem cell cassette. Stem Cells. 2010;28:1728–1740. doi: 10.1002/stem.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kotton DN. Next-generation regeneration: the hope and hype of lung stem cell research. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:1255–1260. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201202-0228PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suzuki T, Mayhew C, Chalk C, Sallese T, Carey BC, Wood RE, Trapnell BC. Induced pluripotent stem cell-derived macrophages from children with hereditary pulmonary alveolar proteinosis recapitulate the disease phenotype and provide a novel tool for therapeutic discovery. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:A3800. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi KD, Vodyanik M, Slukvin II. Hematopoietic differentiation and production of mature myeloid cells from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Protoc. 2011;6:296–313. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uchida K, Beck DC, Yamamoto T, Berclaz PY, Abe S, Staudt MK, Carey BC, Filippi MD, Wert SE, Denson LA, et al. GM-CSF autoantibodies and neutrophil dysfunction in pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:567–579. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakata K, Akagawa KS, Fukayama M, Hayashi Y, Kadokura M, Tokunaga T. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor promotes the proliferation of human alveolar macrophages in vitro. J Immunol. 1991;147:1266–1272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berclaz PY, Carey B, Fillipi MD, Wernke-Dollries K, Geraci N, Cush S, Richardson T, Kitzmiller J, O’connor M, Hermoyian C, et al. GM-CSF regulates a PU.1-dependent transcriptional program determining the pulmonary response to LPS. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;36:114–121. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0174OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonfield TL, Farver CF, Barna BP, Malur A, Abraham S, Raychaudhuri B, Kavuru MS, Thomassen MJ. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma is deficient in alveolar macrophages from patients with alveolar proteinosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;29:677–682. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0148OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shibata Y, Berclaz PY, Chroneos ZC, Yoshida M, Whitsett JA, Trapnell BC. GM-CSF regulates alveolar macrophage differentiation and innate immunity in the lung through PU.1. Immunity. 2001;15:557–567. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00218-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomassen MJ, Barna BP, Malur AG, Bonfield TL, Farver CF, Malur A, Dalrymple H, Kavuru MS, Febbraio M. ABCG1 is deficient in alveolar macrophages of GM-CSF knockout mice and patients with pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. J Lipid Res. 2007;48:2762–2768. doi: 10.1194/jlr.P700022-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bonfield TL, Raychaudhuri B, Malur A, Abraham S, Trapnell BC, Kavuru MS, Thomassen MJ. PU.1 regulation of human alveolar macrophage differentiation requires granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;285:L1132–L1136. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00216.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sakagami T, Uchida K, Suzuki T, Carey BC, Wood RE, Wert SE, Whitsett JA, Trapnell BC, Luisetti M. Human GM-CSF autoantibodies and reproduction of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2679–2681. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0904077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uchida K, Nakata K, Trapnell BC, Terakawa T, Hamano E, Mikami A, Matsushita I, Seymour JF, Oh-Eda M, Ishige I, et al. High-affinity autoantibodies specifically eliminate granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor activity in the lungs of patients with idiopathic pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Blood. 2004;103:1089–1098. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berclaz PY, Shibata Y, Whitsett JA, Trapnell BC. GM-CSF, via PU.1, regulates alveolar macrophage Fcgamma R-mediated phagocytosis and the IL-18/IFN-gamma -mediated molecular connection between innate and adaptive immunity in the lung. Blood. 2002;100:4193–4200. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ikegami M, Ueda T, Hull W, Whitsett JA, Mulligan RC, Dranoff G, Jobe AH. Surfactant metabolism in transgenic mice after granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor ablation. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:L650–L658. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.270.4.L650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kennedy MA, Barrera GC, Nakamura K, Baldán A, Tarr P, Fishbein MC, Frank J, Francone OL, Edwards PA. ABCG1 has a critical role in mediating cholesterol efflux to HDL and preventing cellular lipid accumulation. Cell Metab. 2005;1:121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Senju S, Haruta M, Matsumura K, Matsunaga Y, Fukushima S, Ikeda T, Takamatsu K, Irie A, Nishimura Y. Generation of dendritic cells and macrophages from human induced pluripotent stem cells aiming at cell therapy. Gene Ther. 2011;18:874–883. doi: 10.1038/gt.2011.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Longmire TA, Ikonomou L, Hawkins F, Christodoulou C, Cao Y, Jean JC, Kwok LW, Mou H, Rajagopal J, Shen SS, et al. Efficient derivation of purified lung and thyroid progenitors from embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:398–411. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mou H, Zhao R, Sherwood R, Ahfeldt T, Lapey A, Wain J, Sicilian L, Izvolsky K, Musunuru K, Cowan C, et al. Generation of multipotent lung and airway progenitors from mouse ESCs and patient-specific cystic fibrosis iPSCs. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:385–397. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suzuki T, Maik P, Sallese T, van der Loo JD, Black D, Carey BC, Chalk C, Wood RE, Trapnell BC. Macrophage-mediated lentiviral gene therapy of hereditary pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (hPAP): preclinical efficacy and safety studies. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:A2897. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kleff V, Sorg UR, Bury C, Suzuki T, Rattmann I, Jerabek-Willemsen M, Poremba C, Flasshove M, Opalka B, Trapnell B, et al. Gene therapy of beta(c)-deficient pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (beta(c)-pap): studies in a murine in vivo model. Mol Ther. 2008;16:757–764. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suzuki T, Sakagami T, Carey BC, Chalk C, Wood RE, Trapnell BC. Preclinical evaluation of pulmonary macrophages transplantation therapy of hereditary pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:A2505. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suzuki T, Chalk C, Black D, Sallese T, Carey BC, Wood RE, Trapnell BC. Pulmonary macrophage transplantation therapy of hereditary pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: long-term pre-clinical evaluation of pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, efficiency, safety, and durability. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:A3799. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yona S, Kim KW, Wolf Y, Mildner A, Varol D, Breker M, Strauss-Ayali D, Viukov S, Guilliams M, Misharin A, et al. Fate mapping reveals origins and dynamics of monocytes and tissue macrophages under homeostasis. Immunity. 2013;38:79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hashimoto D, Chow A, Noizat C, Teo P, Beasley MB, Leboeuf M, Becker CD, See P, Price J, Lucas D, et al. Tissue-resident macrophages self-maintain locally throughout adult life with minimal contribution from circulating monocytes. Immunity. 2013;38:792–804. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Willinger T, Rongvaux A, Takizawa H, Yancopoulos GD, Valenzuela DM, Murphy AJ, Auerbach W, Eynon EE, Stevens S, Manz MG, et al. Human IL-3/GM-CSF knock-in mice support human alveolar macrophage development and human immune responses in the lung. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:2390–2395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019682108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okita K, Ichisaka T, Yamanaka S. Generation of germline-competent induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2007;448:313–317. doi: 10.1038/nature05934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Si-Tayeb K, Lemaigre FP, Duncan SA. Organogenesis and development of the liver. Dev Cell. 2010;18:175–189. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jia F, Wilson KD, Sun N, Gupta DM, Huang M, Li Z, Panetta NJ, Chen ZY, Robbins RC, Kay MA, et al. A nonviral minicircle vector for deriving human iPS cells. Nat Methods. 2010;7:197–199. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu J, Hu K, Smuga-Otto K, Tian S, Stewart R, Slukvin II, Thomson JA. Human induced pluripotent stem cells free of vector and transgene sequences. Science. 2009;324:797–801. doi: 10.1126/science.1172482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Warren L, Manos PD, Ahfeldt T, Loh YH, Li H, Lau F, Ebina W, Mandal PK, Smith ZD, Meissner A, et al. Highly efficient reprogramming to pluripotency and directed differentiation of human cells with synthetic modified mRNA. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:618–630. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hou P, Li Y, Zhang X, Liu C, Guan J, Li H, Zhao T, Ye J, Yang W, Liu K, et al. Pluripotent stem cells induced from mouse somatic cells by small-molecule compounds. Science. 2013;341:651–654. doi: 10.1126/science.1239278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Terrenoire C, Wang K, Tung KW, Chung WK, Pass RH, Lu JT, Jean JC, Omari A, Sampson KJ, Kotton DN, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells used to reveal drug actions in a long QT syndrome family with complex genetics. J Gen Physiol. 2013;141:61–72. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201210899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]