Abstract

Rationale: Emerging evidence suggests a restrictive phenotype of chronic lung allograft dysfunction (CLAD) exists; however, the optimal approach to its diagnosis and clinical significance is uncertain.

Objectives: To evaluate the hypothesis that spirometric indices more suggestive of a restrictive ventilatory defect, such as loss of FVC, identify patients with distinct clinical, radiographic, and pathologic features, including worse survival.

Methods: Retrospective, single-center analysis of 566 consecutive first bilateral lung recipients transplanted over a 12-year period. A total of 216 patients developed CLAD during follow-up. CLAD was categorized at its onset into discrete physiologic groups based on spirometric criteria. Imaging and histologic studies were reviewed when available. Survival after CLAD diagnosis was assessed using Kaplan-Meier and Cox proportional hazards models.

Measurements and Main Results: Among patients with CLAD, 30% demonstrated an FVC decrement at its onset. These patients were more likely to be female, have radiographic alveolar or interstitial changes, and histologic findings of interstitial fibrosis. Patients with FVC decline at CLAD onset had significantly worse survival after CLAD when compared with those with preserved FVC (P < 0.0001; 3-yr survival estimates 9% vs. 48%, respectively). The deleterious impact of CLAD accompanied by FVC loss on post-CLAD survival persisted in a multivariable model including baseline demographic and clinical factors (P < 0.0001; adjusted hazard ratio, 2.73; 95% confidence interval, 1.86–4.04).

Conclusions: At CLAD onset, a subset of patients demonstrating physiology more suggestive of restriction experience worse clinical outcomes. Further study of the biologic mechanisms underlying CLAD phenotypes is critical to improving long-term survival after lung transplantation.

Keywords: lung transplantation, spirometry, chronic lung allograft dysfunction, bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Recent studies suggest that distinct phenotypes might exist among pulmonary transplant recipients with chronic lung allograft dysfunction (CLAD), particularly related to the presence of restriction, and that these phenotypes influence prognosis. The approach to differentiation of a restrictive CLAD phenotype, however, remains controversial and no strategy has yet been developed that can be prospectively applied at CLAD onset to confer meaningful prognostic information.

What This Study Adds to the Field

We demonstrate that CLAD can be categorized to discrete physiologic phenotypes at its onset using spirometric measures routinely obtained in all lung recipients. Patients with a loss of FVC at CLAD onset, which may suggest a restrictive ventilatory defect, have significantly worse survival after CLAD when compared with those with preserved vital capacity in whom restriction is unlikely.

Lung transplantation is an established therapy for a range of end-stage pulmonary diseases. Long-term survival, however, remains limited primarily because of the development of chronic lung allograft dysfunction (CLAD) (1). Although the term CLAD has not yet been formally defined, it has been adopted by recent publications in the field to reflect a condition of sustained lung function impairment (2). Previously, bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS) was the most widely described phenotype of CLAD. BOS is a well-established condition specifically defined by the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) as an irreversible decline in the FEV1 relative to the highest post-transplant baseline and is generally thought to correlate with histologic findings of BO, or small airways fibrosis (3).

Although BOS has served as an important descriptor of allograft dysfunction, it is increasingly recognized that some lung recipients develop progressive allograft dysfunction with clinical features atypical for BOS. Consequently, there is a pressing need to differentiate and more precisely define CLAD phenotypes to understand their underlying mechanisms, identify treatment targets, increase the homogeneity of patient populations for clinical research, and provide more accurate outcomes prognostication for patient care.

Recent studies suggest a form of CLAD exists that is characterized by restrictive lung function, radiographic infiltrates, or acute fibrinoid organizing pneumonia that in some analyses is associated with worse survival (4–7). Although there is no single accepted approach to distinguish this subset of CLAD patients, prior studies have used longitudinal TLC measurements or multimodal strategies considering a combination of spirometric, radiographic, and histologic findings (4–7). Unfortunately, TLC is not routinely performed as part of lung recipient follow-up at most transplant centers and radiographic and pathologic descriptions can vary depending on the timing or extent of sampling. Additionally, it remains uncertain whether this restrictive CLAD phenotype is distinct from other CLAD phenotypes previously associated with poor clinical outcome, such as early-onset (EO) or severe-onset (SO) forms (8).

To develop a more generalizable and clinically applicable approach to differentiate CLAD phenotypes and better understand their clinical impact, we reviewed our single-center experience of 566 adult first bilateral lung recipients transplanted during a 12-year timeframe. We sought to determine if classification based only on spirometric pattern present at the time of CLAD onset could distinguish clinically meaningful patient subgroups. We hypothesized that patients with spirometric patterns more suggestive of a restrictive ventilatory defect, such as a decrement in FVC and/or increased FEV1/FVC ratio at CLAD onset, would have distinct clinical characteristics, including worse post-CLAD survival, when compared with those with a preserved FVC in whom restriction is unlikely and as is characteristic of BOS. Additionally, we sought to describe the radiographic and histologic findings associated with the observed physiology. These study results were initially presented as an oral abstract at the 2013 American Thoracic Society International Conference (9).

Methods

Study Cohort

Between January 1, 1998 and December 31, 2010, 682 adults (≥18 yr old) received a first bilateral lung transplant at Duke University Medical Center. Excluded from the analysis were recipients not consented for clinical research (n = 24), recipients who survived less than or equal to 90 days (n = 41), recipients with less than or equal to five post-transplant pulmonary function tests (PFTs) (n = 28), and recipients with a decline in lung function attributable to a confounding clinical condition (n = 23). The remaining 566 CLAD-eligible patients were followed to death, retransplantation, or the time of last PFT before May 31, 2012 (mean follow-up, 4.7 ± 3.0 yr). During this time period, 216 of the 566 recipients (38%) developed CLAD, defined as a sustained greater than or equal to 20% decline in FEV1 as compared with the average of the two best post-transplant FEV1 measured at least 3 weeks apart in the absence of other clinical confounders. The final study cohort consisted of these 216 recipients with CLAD. All patients received standardized immunosuppression, PFT follow-up, surveillance bronchoscopies, and other clinical management as described in the online supplement. This study was approved under Duke Institutional Review Board Pro00029129.

CLAD Phenotype Classification

We considered approaches to distinguish spirometric patterns more suggestive of a restrictive ventilatory defect based on the presence of FVC loss at CLAD onset either alone or in association with an elevated FEV1/FVC ratio (>0.8). Patients were considered to have FVC loss if the CLAD onset FVC/FVCBest was less than 0.8, where FVCBest was the average of the two FVC measurements that paired with the two best post-transplant FEV1 used in the CLAD calculation. As detailed in the online supplement, this analysis determined that FVC loss, irrespective of FEV1/FVC ratio, was the spirometric parameter most likely to differentiate a phenotype with homogenous observed clinical outcome. Thus, at CLAD onset, patients were considered to have restrictive CLAD (R-CLAD) if the CLAD onset FVC/FVCBest was less than 0.8; or if this condition was not met, BOS.

Radiology Review

Chest computed tomography (CT) scans performed 30 days before and up to 90 days after CLAD onset were eligible for inclusion. For subjects with multiple eligible CTs, the scan performed nearest to the time of CLAD onset was selected (in the event of equal temporal distribution, the post-CLAD CT was selected). Fifty-two patients with R-CLAD and 69 patients with BOS (80 and 46%, respectively) had an eligible chest CT. Radiology reports were reviewed by a masked pulmonologist. The following findings were systematically noted and characterized: pleural effusion, ground-glass opacities, nodular or tree-in-bud infiltrates, consolidative opacities, bronchiectasis or bronchial wall thickening, septal thickening or reticular opacities, and air trapping. Air trapping was considered assessable only if the CT was performed with both inspiratory and expiratory imaging.

Pathology Review

Lung tissue specimens obtained through videoscopic-assisted thoracoscopy 30 days before or at any time after the onset of CLAD and pneumonectomy samples procured at the time of retransplantation for advanced CLAD were independently reviewed by a masked pathologist. Seven R-CLAD (11%) and 18 BOS (12%) patients had an eligible specimen for review. A, B, C, and D grade rejection, acute lung injury, acute pneumonia, organizing pneumonia, and patterns of parenchymal fibrosis were systematically noted and characterized. All rejection scores were assigned according to the 1996 ISHLT criteria (10).

Allograft Assessments

Acute cellular rejection was defined as the presence of perivascular lymphocytic infiltration noted on pathology and was subsequently graded according to 1996 ISHLT criteria (10). Normalized acute rejection score was calculated as the sum of acute rejection grades before CLAD onset divided by the number of biopsies. Cytomegalovirus pneumonitis was determined by prospective immunohistochemistry staining of all transbronchial lung biopsies before CLAD onset. Primary graft dysfunction (PGD) grade 3 at 72 hours post-reperfusion was evaluated according to ISHLT guidelines (11). Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) specimens were assessed for culture growth of any bacterial, fungal, or mycobacterial organism. The BAL samples were also evaluated for community-acquired respiratory viral pathogens by polymerase chain reaction. EO-CLAD was defined according to prior literature as the onset of CLAD within 2 years of transplantation, whereas SO-CLAD was defined as a decline in FEV1 to less than or equal to 65% of the post-transplant baseline at CLAD onset (8).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize cohort demographics with standard deviation or interquartile range (IQR) given to describe the variance around the mean or median, respectively. Nonparametric Wilcoxon t tests (two-tailed P value) were used to assess group mean differences for demographic and time-independent baseline characteristics; chi-square or Fisher exact tests, as appropriate, were used to evaluate frequency differences. Descriptive survival curves depicting survival days after the onset of CLAD were generated with Kaplan-Meier analysis. The impact of R-CLAD (considered as a time-independent variable) on survival after CLAD (time to death or retransplantation) was estimated using multivariable Cox proportional hazards, adjusted for baseline demographics including age, restrictive native disease, white race, female sex, and early transplant era. In addition to demographics, variables included in the final multivariate model included those related to the timing and severity of CLAD onset, EO-CLAD, and SO-CLAD (8). All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (Cary, NC).

Results

Cohort Phenotypic Distribution and Clinical Characteristics

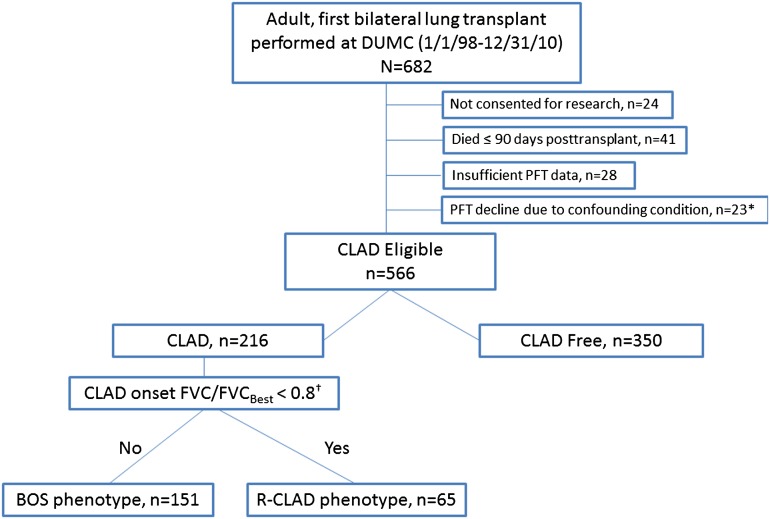

Figure 1 depicts the derivation and phenotypic classification of the patient cohort. Within this cohort of first bilateral lung recipients with CLAD, 30% (65 of 216) of patients met the spirometric criteria for R-CLAD, as assessed by the degree of FVC loss from baseline at CLAD onset, whereas the remaining 70% (151 of 216) were BOS. There was no significant difference in the time to CLAD onset between the groups; with a median time to R-CLAD of 2.82 year (IQR, 1.25–4.17) versus 3.26 year (IQR, 1.53–5.42) for BOS (P = 0.14). The median FEV1/FVC ratio at CLAD onset in the R-CLAD group was 80%; as expected, this was considerably higher than in BOS (65%). Compared with patients with BOS, those with R-CLAD were more likely to be female (R-CLAD, 55% vs. BOS, 36%; P = 0.01) and have SO-CLAD (R-CLAD, 48% vs. BOS, 17%; P < 0.0001). In contrast, PGD grade 3 at 72 hours was more commonly observed in patients with BOS rather than R-CLAD phenotype (8% vs. 0%; P = 0.02), although overall PGD rates were low. Notably, there were no apparent differences in other clinical characteristics, for example native disease, age, donor sex, and frequency of EO-CLAD (Table 1).

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram describing study cohort derivation and physiologic CLAD phenotype classification. BOS = bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome; CLAD = chronic lung allograft dysfunction; DUMC = Duke University Medical Center; PFT = pulmonary function test; R-CLAD = restrictive chronic lung allograft dysfunction. *Malignancy coincident with PFT decline (n = 13), significant airway stenosis (n = 1), uncontrolled infection (n = 3), significant pleural disease (n = 5), unreliable PFT data (n = 1). †Criteria applied to CLAD onset PFT, FVCBest is defined as the average of the two FVCs associated with the two PFTs used in FEV1 baseline calculation for CLAD diagnosis.

Table 1:

Clinical Characteristics of Patients with CLAD, Stratified by Physiologic CLAD Phenotype

| Characteristic | Restrictive CLAD (n = 65) | BOS (n = 151) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recipient sex, female | 36 (55%) | 55 (36%) | 0.01 |

| Donor sex, female | 24 (37%) | 60 (40%) | 0.70 |

| Race | |||

| White | 60 (92%) | 130 (86%) | 0.20 |

| African American | 5 (8%) | 19 (13%) | 0.29 |

| Other | 0 (0%) | 2 (1%) | 1.0 |

| Age at transplant, yr* | 55 (40–62) | 55 (40–61) | 0.71 |

| Transplanted before March 1, 2002† | 18 (28%) | 49 (32%) | 0.49 |

| Native disease category | |||

| Obstructive | 22 (34%) | 59 (39%) | 0.47 |

| Restrictive | 29 (45%) | 56 (37%) | 0.30 |

| Cystic | 13 (20%) | 30 (20%) | 0.98 |

| Other‡ | 1 (2%) | 6 (4%) | 0.68 |

| PGD grade 3 at 72 h | 0 (0%) | 12 (8%) | 0.02 |

| Early onset CLAD§ | 22 (34%) | 49 (32%) | 0.84 |

| Severe-onset CLAD§ | 31 (48%) | 25 (17%) | <0.0001 |

Definition of abbreviations: BOS = bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome; CLAD = chronic allograft dysfunction; PGD = primary graft dysfunction.

Median (interquartile range).

This date reflects the change in standardized immunosuppression from a cyclosporine-based regimen (before March 1, 2002) to a tacrolimus-based regimen (after March 1, 2002).

Vascular and uncategorized.

Early onset CLAD and severe-onset CLAD were defined according to prior literature as the onset of CLAD within 2 years of transplantation (early onset) or as a decline in FEV1 to ≤65% of the post-transplant baseline at CLAD onset (severe onset) (8).

From the time of transplantation to CLAD onset all patients in the CLAD cohort underwent a similar number of bronchoscopies (median, 10 bronchoscopies [IQR 7 and 15]). Over this timeframe all patients, irrespective of physiologic CLAD phenotype, experienced similar rates of acute cellular rejection (measured as normalized acute rejection score), cytomegalovirus pneumonitis, and positive BAL cultures for a bacterial, fungal, mycobacterial, or community-acquired respiratory viral organism (see Table E1 in the online supplement). Additionally, when interventions after the onset of CLAD were evaluated, there were no significant differences noted in the use of antithymocyte globulin, alemtuzumab, or gastric fundoplication between patients with R-CLAD or BOS; however, azithromycin was more commonly prescribed to patients with BOS phenotype (BOS, 73% vs. R-CLAD, 57%; P = 0.02) (see Table E2).

Impact of Physiologic Phenotype on Survival after CLAD Onset

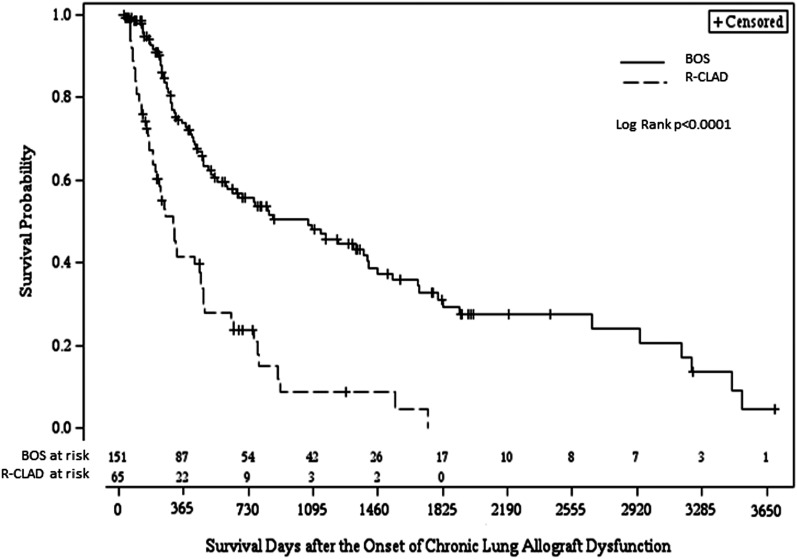

Patients with a spirometric pattern of FVC loss, which could suggest a restrictive ventilatory defect at CLAD onset, experienced significantly worse post-CLAD survival when compared with patients with BOS (P < 0.0001; unadjusted hazard ratio, 3.01; 95% confidence interval, 2.07–4.37). One- and 3-year Kaplan-Meier post-CLAD survival estimates for the R-CLAD group were 40 and 9% in contrast to 73 and 48% for the BOS group; P < 0.0001 (Figure 2). Median survival after CLAD onset for those with R-CLAD and BOS was 309 (IQR, 209–462) and 1,070 (IQR, 605–1,402) days respectively. The adverse impact of R-CLAD on post-CLAD survival remained significant when adjusted for demographic and baseline clinical factors (P < 0.0001; adjusted hazard ratio, 2.73; 95% confidence interval, 1.86–4.04).

Figure 2.

A spirometric pattern characterized by loss of forced vital capacity, which may be suggestive of restrictive physiology (R-CLAD), on the onset of CLAD was associated with worse survival, compared with BOS physiology. One- and 3-year survival estimates for R-CLAD and BOS were 40 and 9% in contrast to 73 and 48%, respectively. Median time to death in the R-CLAD and BOS groups was 309 and 1,070 days, respectively. BOS = bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome; CLAD = chronic lung allograft dysfunction; R-CLAD = restrictive chronic lung allograft dysfunction.

Relationship of CLAD Phenotype to EO- or SO-CLAD

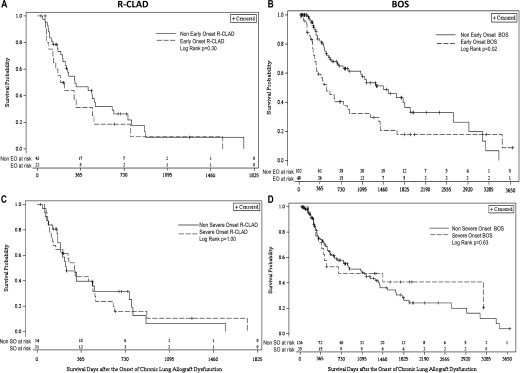

Because our previous work has demonstrated that the severity or timing of CLAD onset impacts survival after its development (8), we sought to evaluate the influence of these factors on survival within patients with R-CLAD or BOS phenotype. When EO- or SO-CLAD was considered only within patients presenting with R-CLAD physiology, neither EO nor SO had an impact on survival after CLAD onset (Figures 3A and 3C). In contrast, when EO- or SO-CLAD was considered within patients with BOS phenotype we found that EO-, but not SO-CLAD was associated with significantly worse post-CLAD survival (Figures 3B and 3D). Similarly, when EO- and SO-CLAD were considered in a multivariable survival model that also included physiologic CLAD phenotype, both R-CLAD and EO-CLAD were independent risk factors for increased mortality after CLAD onset, whereas SO-CLAD was not (see Table E3).

Figure 3.

Unadjusted Kaplan-Meier curves for survival after CLAD by severity and timing of CLAD onset within each of the physiologic phenotypes. Early-onset CLAD was not associated with worse survival after CLAD onset within R-CLAD (A), but did have a significant deleterious impact on post-CLAD survival among patients presenting with BOS physiology (B). The severity of CLAD onset did not impact survival within either the R-CLAD (C) or BOS (D) groups. BOS = bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome; CLAD = chronic lung allograft dysfunction; R-CLAD = restrictive chronic lung allograft dysfunction.

CLAD Phenotype Radiographic and Pathologic Correlates

Radiology

Median time from CLAD onset to CT scan was similar in both physiologic CLAD subgroups (6 d [IQR, 0–22] for R-CLAD and 7 d [IQR, 0–39] for BOS). Radiographic findings are described in Table 2. Notably, alveolar or interstitial changes were nearly twice as common within the R-CLAD group, whereas air trapping (when assessed) was more frequently noted for those with BOS and was generally distinctly absent in those with R-CLAD. Although we did not specifically assess for lobar predominance, within patients with R-CLAD the alveolar or interstitial findings involved the upper lobes to some extent in most cases (32 [80%] of 40).

Table 2:

Radiographic Findings on Chest CT Scan Concurrent with CLAD Onset

| Characteristic | Restrictive CLAD (n = 52) | BOS (n = 69) |

|---|---|---|

| Nodular or tree-in-bud infiltrate | 16 (31%) | 19 (28%) |

| Bronchiectasis/bronchial wall thickening | 12 (23%) | 19 (28%) |

| Air trapping, assessed and noted* | 1 (2%) | 12 (17%) |

| Air trapping, assessed and not noted* | 5 (10%) | 4 (6%) |

| Bronchiectasis/bronchial thickening or air trapping | 12 (23%) | 27 (39%) |

| Alveolar or interstitial changes† | 40 (77%) | 32 (47%) |

Definition of abbreviations: BOS = bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome; CLAD = chronic lung allograft dysfunction; CT = computed tomography.

As assessed by expiratory imaging on high-resolution chest CT scan.

Defined as the presence of consolidative opacities, ground-glass, septal thickening, or reticulation.

Histology

Findings of B-grade rejection and pathologically active constrictive bronchiolitis were much more likely in the BOS group, whereas D-grade rejection, organizing pneumonia, and interstitial fibrosis were noted with increased frequency in those with R-CLAD (Table 3). When present, interstitial fibrosis was more often assessed as moderate or severe in R-CLAD and mild in BOS. Interestingly, findings of histologically inactive constrictive bronchiolitis were present in most (4 [67%] of 6) assessable tissue specimens from patients with R-CLAD.

Table 3:

Histologic Findings on Surgical Lung Biopsy Concurrent with CLAD or Pneumonectomy Specimens Procured at the Time of Retransplantation for Advanced CLAD

| Characteristic | Restrictive CLAD (n = 7) | BOS (n = 18) |

|---|---|---|

| A grade ≥ 1* | 4 (67%)† | 11 (61%) |

| B grade ≥ 1* | 0 (0%)† | 12 (67%) |

| Ca* | 0 (0%)† | 12 (67%) |

| Cb* | 4 (67%)† | 6 (33%) |

| D grade rejection* | 4 (57%) | 7 (39%) |

| Organizing pneumonia | 3 (43%) | 6 (33%) |

| Interstitial fibrosis | 5 (71%) | 8 (44%) |

Definition of abbreviations: BOS = bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome; CLAD = chronic lung allograft dysfunction.

A, B, C, and D rejection graded according to 1996 International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation criteria (10).

One sample unassessable because of confounding from extent of associated organizing pneumonia or fibrosis. Denominator represents only assessable samples (n = 6).

Discussion

We demonstrate for the first time that CLAD can be categorized to discrete, clinically meaningful physiologic phenotypes at the time of its onset using routinely available spirometric data. Notably, patients with an FVC decrement at CLAD onset, which may be more suggestive of a restrictive ventilatory defect (R-CLAD), had significantly worse survival after CLAD when compared with patients with preserved FVC (BOS), in whom restriction is unlikely. The deleterious impact of R-CLAD on post-CLAD survival was independent of clinical or demographic characteristics. Although there were no differences in native disease or infection and acute rejection rates before CLAD onset between the R-CLAD and BOS groups, R-CLAD patients were more likely to be female. Radiographic findings of alveolar or interstitial changes and pathologic findings of moderate to severe interstitial fibrosis correlated with the spirometric physiology in patients with R-CLAD, whereas patients with BOS physiology were more likely to have air trapping on CT scan and histologically active constrictive bronchiolitis.

We considered physiologic CLAD phenotype in the context of the timing or severity of CLAD onset given our prior results that suggested both EO and SO forms of CLAD are associated with worse survival after its onset. This analysis provided several insights into the relationship of these previously identified phenotypes to the phenotypes of R-CLAD and BOS. Interestingly, in our current analysis SO was not associated with worse survival after the onset of either R-CLAD or BOS. This in part may reflect a lack of power, with a smaller number of SO patients in each physiologic subgroup as compared with our prior study, which considered SO within all patients with CLAD (8). More importantly, however, given the disproportionate number of patients with SO-CLAD in the R-CLAD group, it is likely that R-CLAD overlaps with the SO phenotype. In contrast, the timing of CLAD onset remained a significant independent predictor for worse survival after CLAD, with the impact of EO-CLAD being greatest in patients presenting with BOS physiology. These results reinforce the idea that clinically important phenotypes exist within CLAD, based on the timing of onset and presenting physiologic pattern, with a worse prognosis associated with either R-CLAD or EO-BOS as compared with later-onset BOS.

Previous studies developed the term restrictive allograft syndrome (RAS) to describe lung recipients with a decline in FEV1 accompanied by a greater than 10% sustained decline in TLC (4, 5). We believe that our spirometric definition of R-CLAD identified a similar patient subset to that previously characterized as RAS. RAS has been described to account for 25–35% of patients with CLAD and has been associated with radiographic changes of interstitial lung disease, pathologic findings of diffuse alveolar damage or interstitial fibrosis, and poor survival after CLAD (4, 5, 12). Notably, we found a comparable percentage of patients with a spirometric pattern more suggestive of a restrictive ventilatory defect in our cohort and many of the radiographic, pathologic, and clinical findings associated with R-CLAD parallel these prior descriptions. For example, we found patients with R-CLAD were more likely to have moderate or severe interstitial fibrosis on lung pathology than those with BOS. Lesions of (inactive) BO were also present in many cases, however, similar to previous reports of RAS (5, 12). Additionally, we observed a median survival after R-CLAD of 309 days, which is within the range reported in three prior studies evaluating survival after RAS (240–541 d) (4, 5, 13).

Our methodologic approach to identify patients with physiology more suggestive of restriction and classify CLAD phenotypes differs from that applied in previous studies evaluating RAS (4, 5), which have relied on TLC. Although TLC verifies the presence of restriction, it is not consistently performed as part of post-transplant follow-up at many lung transplant centers, which has hampered the applicability of the RAS definition. Our approach also differs from the multimodal strategy for CLAD classification recently published by Paraskeva and colleagues (7). Although spirometric indices comprised a part of their approach, the greatest weighting was placed on histopathologic findings, which as a result often dictated final CLAD assignment. Importantly, because these previously described methodologies used either longitudinal physiologic data obtained after CLAD onset or subsequent pathology (even autopsy) to arrive at a final CLAD phenotype their ability to be applied prospectively may be limited.

Although the results of our analysis complement the rapidly growing body of literature related to CLAD phenotypes and substantiate the idea that a restrictive phenotype of CLAD exists and is associated with significantly worse survival, in contrast to these prior studies there are important novelties to our approach to CLAD classification. Namely, our approach uses only spirometric measures routinely obtained in all lung recipients and assigns physiologic phenotypic classifications in all patients at CLAD onset rather than based on retrospective review of serial follow-up data. Furthermore, we consider the R-CLAD phenotype within the context of prior literature and reconcile previously described phenotypes associated with poor outcome caused by early onset or SO within the current R-CLAD and BOS nomenclature. Thus, our study provides a path to further advance the understanding of post-transplant allograft dysfunction by building on, rather than further compartmentalizing, CLAD classification.

Although the biologic mechanisms that predispose to the development of R-CLAD or RAS are unknown, the correlative histologic patterns of lung injury, including diffuse alveolar damage, interstitial fibrosis, and acute fibrinoid organizing pneumonia (in the case of the Paraskeva study) at times accompanied by typical BO pathology may provide some insight. Although speculative, patients who develop restriction might have cellular or humoral responses that directly target alveolar in addition to bronchial antigens as opposed to patients with BOS where antigenic targets are confined to the airways. Given that females are more likely to have circulating anti-HLA antibodies (14) and were overrepresented in the R-CLAD group, we performed a preliminary analysis examining sensitization in this cohort. Notably, patients with R-CLAD were more likely than those with BOS to have newly detected HLA antibodies, some of which were donor specific, temporally associated with CLAD onset (data not shown). Given the evolution of antibody detection technology and variable surveillance over the study period, however, and the emergence of non-HLA antigenic targets, further studies are needed to better address this point.

Although this study included a large cohort of lung recipients rigorously characterized with respect to CLAD phenotypes, it has certain inherent limitations. We recognize our results are retrospective and single center in nature and should be validated in other centers; however, this now can be readily performed given that our approach relies on simple spirometry at CLAD onset. An additional consideration is that our analysis is limited to bilateral lung recipients. Given our center’s preference for bilateral transplantation, our sample size is inadequate to ascertain whether these results may apply to single lung recipients. We also recognize our histologic and radiologic analyses included only a subset of all R-CLAD and BOS patients and as such may have been prone to selection bias. However, because our phenotypic definition was derived strictly from spirometry, this additional histologic analysis is only descriptive, intended to highlight features that may correlate with the observed physiology. Finally, although the spirometric criteria we used to define CLAD and subsequently differentiate R-CLAD were based on scientific and clinical rationale, we recognize the inherent limitations of spirometry, and specifically our approach using FVC loss alone, in determining restriction. However, as described in the online supplement, incorporating FEV1/FVC ratio in the R-CLAD definition did not enhance the ability to distinguish distinct phenotypes with differential prognosis.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that spirometric patterns present at CLAD onset can distinguish physiologic CLAD phenotypes and provide clinically meaningful prognostic information. A novelty of our results includes reliance on commonly assessed spirometric indices to allow identification of patients with R-CLAD at the onset of chronic lung dysfunction. This approach, therefore, can be immediately validated and widely adopted across lung transplant centers. Ultimately, given the lack of effective treatments for chronic allograft dysfunction after lung transplantation, improved phenotypic homogeneity is critical to better understand the mechanisms that contribute to CLAD development and uncover novel treatment or preventive strategies.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: J.L.T., manuscript preparation, data analysis. R.J. and C.A.F.C., data analysis, manuscript review. E.N.P., pathology review, manuscript review. J.M.R., contextual relevance, manuscript review. L.D.S. and S.M.P., concept design, manuscript review.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201306-1155OC on December 10, 2013

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Christie JD, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, Benden C, Dipchand AI, Dobbels F, Kirk R, Rahmel AO, Stehlik J, Hertz MI International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: 29th adult lung and heart-lung transplant report-2012. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2012;31:1073–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sato M. Chronic lung allograft dysfunction after lung transplantation: the moving target. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;61:67–78. doi: 10.1007/s11748-012-0167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Estenne M, Maurer JR, Boehler A, Egan JJ, Frost A, Hertz M, Mallory GB, Jr, Snell GI, Yousem S. Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome 2001: an update of the diagnostic criteria. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2002;21:297–310. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(02)00398-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verleden GM, Vos R, Verleden SE, De Wever W, De Vleeschauwer SI, Willems-Widyastuti A, Scheers H, Dupont LJ, Van Raemdonck DE, Vanaudenaerde BM. Survival determinants in lung transplant patients with chronic allograft dysfunction. Transplantation. 2011;92:703–708. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31822bf790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sato M, Waddell TK, Wagnetz U, Roberts HC, Hwang DM, Haroon A, Wagnetz D, Chaparro C, Singer LG, Hutcheon MA, et al. Restrictive allograft syndrome (RAS): a novel form of chronic lung allograft dysfunction. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2011;30:735–742. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2011.01.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woodrow JP, Shlobin OA, Barnett SD, Burton N, Nathan SD. Comparison of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome to other forms of chronic lung allograft dysfunction after lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29:1159–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paraskeva M, McLean C, Ellis S, Bailey M, Williams T, Levvey B, Snell GI, Westall GP. Acute fibrinoid organizing pneumonia after lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:1360–1368. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201210-1831OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finlen Copeland CA, Snyder LD, Zaas DW, Turbyfill WJ, Davis WA, Palmer SM. Survival after bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome among bilateral lung transplant recipients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:784–789. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201002-0211OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Todd JL, Jain R, Pavlisko EN, Finlen Copeland CA, Snyder LD, Palmer SM. Restrictive spirometry at bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome onset predicts worse survival. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:A3779. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yousem SA, Berry GJ, Cagle PT, Chamberlain D, Husain AN, Hruban RH, Marchevsky A, Ohori NP, Ritter J, Stewart S, et al. Revision of the 1990 working formulation for the classification of pulmonary allograft rejection: Lung Rejection Study Group. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1996;15:1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christie JD, Carby M, Bag R, Corris P, Hertz M, Weill D ISHLT Working Group on Primary Lung Graft Dysfunction. Report of the ISHLT working group on primary lung graft dysfunction part II: Definition. A consensus statement of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24:1454–1459. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2004.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ofek E, Sato M, Saito T, Wagnetz U, Roberts HC, Chaparro C, Waddell TK, Singer LG, Hutcheon MA, Keshavjee S, et al. Restrictive allograft syndrome post lung transplantation is characterized by pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis. Mod Pathol. 2013;26:350–356. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sato M, Ohmori-Matsuda K, Saito T, Matsuda Y, Hwang DM, Waddell TK, Singer LG, Keshavjee S. Time-dependent changes in the risk of death in pure bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS) J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32:484–491. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2013.01.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Snyder LD, Wang Z, Chen DF, Reinsmoen NL, Finlen-Copeland CA, Davis WA, Zaas DW, Palmer SM. Implications for human leukocyte antigen antibodies after lung transplantation: a 10-year experience in 441 patients. Chest. 2013;144:226–233. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-0587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]