To the Editor:

Spirometry, the traditional method for grading disease severity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), has limitations as FEV1 correlates poorly with clinically relevant outcomes such as health-related quality of life, breathlessness, and exercise capacity (1). Since 2011, the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) has recommended that decisions regarding COPD management and treatment should consider future risk of exacerbations (determined by exacerbation history or airflow obstruction) and disease impact on symptoms (using either the modified Medical Research Council dyspnea score [mMRC] or the COPD Assessment Test [CAT]). Hence, patients can be classified into four GOLD categories comprising A: low risk, fewer symptoms; B: low risk, more symptoms; C: high risk, fewer symptoms; and D: high risk, more symptoms. GOLD classifies a higher level of symptoms using the following cut points: mMRC ≥ 2 or a CAT score ≥ 10, with a preference for the CAT as it gives a more comprehensive assessment of the symptomatic impact of the disease.

In the most recent 2013 update to the GOLD document, the Clinical COPD Questionnaire (CCQ) was suggested as an alternative to the CAT. The CCQ is a simple, 10-item questionnaire, and there is increasing data supporting its reliability, validity, and responsiveness (2, 3). GOLD suggested an arbitrary cut point of ≥1 for the CCQ but acknowledged that little data exists to support this. The aim of our study was to estimate the cut point for the CCQ that is equivalent to current GOLD-recommended cut points for the CAT and mMRC.

We analyzed baseline data from 788 patients participating in an ongoing longitudinal observational study to determine whether physical performance measures predict adverse outcomes in COPD. Patients were recruited from primary and secondary care clinics in northwest London. Inclusion criteria included a diagnosis of COPD, according to GOLD criteria, and no exacerbation in the previous 6 weeks. Exclusion criteria included any condition that might make exercise unsafe (e.g., unstable cardiac disease) or predominant neurological limitation to walking. The study was approved by an ethics research committee, and all patients gave informed consent. Measurements included the CAT, the CCQ, the mMRC, the incremental shuttle walk (4), the 4-m gait speed (5), and the five-repetition sit-to-stand (6).

Pearson’s correlation was used to determine the interrelationship between CCQ, CAT, and mMRC. We then used linear regression to determine the mean equivalent CCQ cut point to a CAT score of 10 and an mMRC score of 2; a priori criteria for validity were that there had to be a statistically significant (P < 0.05) and strong (r ≥ 0.7) correlation between CCQ and the symptom assessment instrument.

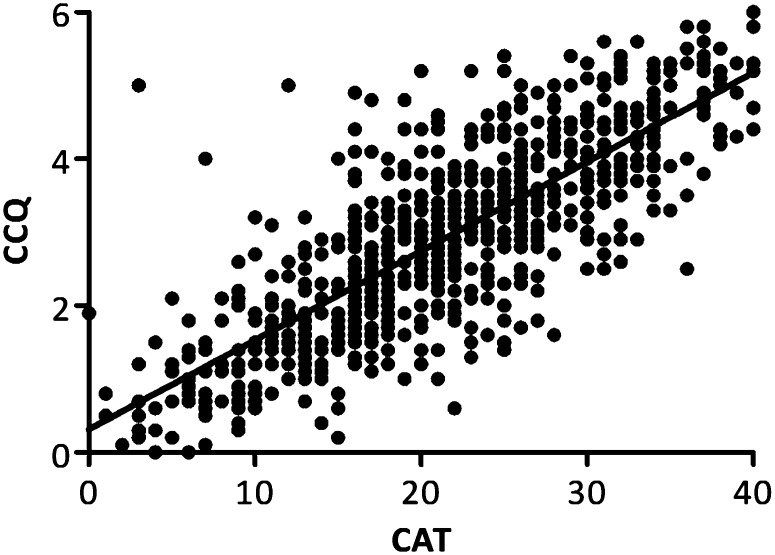

Baseline characteristics (mean [95% confidence intervals (CIs)]) of the cohort are shown in Table 1. CCQ correlated significantly with CAT (R2 = 0.63; P < 0.001) and mMRC (R2 = 0.26; P < 0.001). Figure 1 shows the relationship between CCQ and CAT. The linear regression demonstrated a mean (95% CI) slope of 0.121 (0.115–0.128) and a mean (95% CI) y-intercept of 0.318 (0.169–0.468). For the CAT cut point of 10, the equivalent mean (95% CI) cut point for the CCQ was 1.5 (1.3–1.7). As the CCQ did not correlate strongly to the mMRC, we did not apply linear regression. However, the mean (95% CI) CCQ and CAT scores for patients who reported an mMRC of 2 were 2.9 (2.7–3.0) and 21.0 (20.0–22.0), respectively. The mean (95% CI) scores for patients who reported an mMRC of 1 were 2.1 (1.9–2.2) and 16.3 (15.3–17.3) for the CCQ and CAT.

Table 1:

Baseline Characteristics

| Characteristic | Sample Size or Mean (95% Confidence Interval) |

|---|---|

| Sex, male/female | 440/348 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.8 (28.3–29.3) |

| FEV1% predicted | 53.6 (52.0–55.2) |

| CAT | 21.2 (20.6–21.8) |

| mMRC | 2.3 (2.2–2.4) |

| CCQ | 2.9 (2.8–3.0) |

| ISW, m | 217 (205–228) |

| 4MGS, m/s | 0.89 (0.87–0.91) |

| 5STS, s | 15.4 (14.9–16.0) |

Definition of abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; CAT = COPD Assessment Test; mMRC = Modified Medical Research Council dyspnea score; CCQ = Clinical COPD Questionnaire; ISW = incremental shuttle walk; 4MGS = 4-m gait speed; 5STS = five-repetition sit-to-stand.

n = 788.

Figure 1.

Relationship between the Clinical Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Questionnaire (CCQ) and COPD Assessment Test (CAT) (R2 = 0.63; P < 0.001).

To our knowledge, this is the largest cohort of patients with COPD to record the CAT, CCQ, and mMRC concurrently, and provides initial evidence to suggest that the currently suggested cut point for the CCQ (≥1) by GOLD is not equivalent to the GOLD-recommended cut points for the CAT or mMRC. A limitation of the new GOLD combined COPD assessment classification system is that it produces very different categories, depending on the instrument used (e.g., CAT or mMRC) (7, 8). This is partly due to the mMRC and CAT measuring different constructs; whereas the mMRC focuses on breathlessness according to ability to perform physical activities, the CAT is a multidimensional instrument. However, it is also increasingly recognized that the current GOLD mMRC cut point of ≥2 may be set too high and underestimate the number of symptomatic patients with COPD (7, 8), a finding observed by recent evidence-based pulmonary rehabilitation guidelines (9).

Like the CAT, the CCQ is a multidimensional instrument that is quick to complete. The y-intercept suggests that a zero score on the CAT is not equivalent to a zero score on the CCQ. This reflects the fact that although measuring similar constructs, there are differences between the instruments. Although some questions are similar to both questionnaires, the CCQ does not contain questions relating to energy or sleep, and the CAT does not contain items related to mental functioning or more detailed questions on breathlessness as seen in the CCQ.

Our data demonstrated a strong relationship between CAT and CCQ and suggest that the current GOLD-suggested cut point of 1.0 for the CCQ is set too low and that 1.5 may be a more appropriate cut point. Our data also corroborate previous findings that the current GOLD cut points for CAT and mMRC are not equivalent (7, 8). We propose that the current GOLD cut points to assess symptom burden require reassessment and modification.

Footnotes

S.S.C.K. is supported by the Medical Research Council (MRC). W.D.-C.M. is supported by the National Institute for Health Research and the MRC. This project was undertaken at the NIHR Respiratory Biomedical Research Unit at the Royal Brompton and Harefield NHS Foundation Trust and Imperial College London; J.L.C.’s, S.E.J.’s, and M.I.P.'s salaries are wholly or partly funded by the NIHR Biomedical Research Unit. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, The National Institute for Health Research, or the Department of Health.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Cazzola M, MacNee W, Martinez FJ, Rabe KF, Franciosi LG, Barnes PJ, Brusasco V, Burge PS, Calverley PM, Celli BR, et al. American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society Task Force on outcomes of COPD. Outcomes for COPD pharmacological trials: from lung function to biomarkers. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:416–469. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00099306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Molen T, Willemse BW, Schokker S, ten Hacken NH, Postma DS, Juniper EF. Development, validity and responsiveness of the Clinical COPD Questionnaire. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:13. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kon SS, Dilaver D, Mittal M, Nolan CM, Clark AL, Canavan JL, Jones SE, Polkey MI, Man WD.The Clinical COPD Questionnaire: response to pulmonary rehabilitation and minimal clinically important difference Thoraxonline ahead of print] 22 Oct 201310.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-204119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh SJ, Morgan MD, Scott S, Walters D, Hardman AE. Development of a shuttle walking test of disability in patients with chronic airways obstruction. Thorax. 1992;47:1019–1024. doi: 10.1136/thx.47.12.1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kon SS, Patel MS, Canavan JL, Clark AL, Jones SE, Nolan CM, Cullinan P, Polkey MI, Man WD. Reliability and validity of 4-metre gait speed in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2013;42:333–340. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00162712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones SE, Kon SS, Canavan JL, Patel MS, Clark AL, Nolan CM, Polkey MI, Man WD. The five-repetition sit-to-stand test as a functional outcome measure in COPD. Thorax. 2013;68:1015–1020. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-203576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones PW, Adamek L, Nadeau G, Banik N. Comparisons of health status scores with MRC grades in COPD: implications for the GOLD 2011 classification. Eur Respir J. 2013;42:647–654. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00125612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han MK, Muellerova H, Curran-Everett D, Dransfield MT, Washko GR, Regan EA, Bowler RP, Beaty TH, Hokanson JE, Lynch DA, et al. GOLD 2011 disease severity classification in COPDGene: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1:43–50. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(12)70044-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bolton CE, Bevan-Smith EF, Blakey JD, Crowe P, Elkin SL, Garrod R, Greening NJ, Heslop K, Hull JH, Man WD, et al. British Thoracic Society Pulmonary Rehabilitation Guideline Development Group; British Thoracic Society Standards of Care Committee. British Thoracic Society guideline on pulmonary rehabilitation in adults. Thorax. 2013;68:ii1–ii30. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-203808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]