Abstract

Objectives

Personalized normative feedback (PNF) interventions are generally effective at correcting normative misperceptions and reducing risky alcohol consumption among college students. However, research has yet to establish what level of reference group specificity is most efficacious in delivering PNF. This study compared the efficacy of a web-based PNF intervention employing eight increasingly-specific reference groups against a Web-BASICS intervention and a repeated-assessment control in reducing risky drinking and associated consequences.

Method

Participants were 1663 heavy drinking Caucasian and Asian undergraduates at two universities. The referent for web-based PNF was either the typical same-campus student, or a same-campus student at one (either gender, race, or Greek-affiliation), or a combination of two (e.g., gender and race), or all three levels of specificity (i.e., gender, race, and Greek-affiliation). Hypotheses were tested using quasi-Poisson generalized linear models fit by generalized estimating equations.

Results

The PNF intervention participants showed modest reductions in all four outcomes (average total drinks, peak drinking, drinking days, and drinking consequences) compared to control participants. No significant differences in drinking outcomes were found between the PNF group as a whole and the Web-BASICS group. Among the eight PNF conditions, participants receiving typical student PNF demonstrated greater reductions in all four outcomes compared to those receiving PNF for more specific reference groups. Perceived drinking norms and discrepancies between individual behavior and actual norms mediated the efficacy of the intervention.

Conclusions

Findings suggest a web-based PNF intervention using the typical student referent offers a parsimonious approach to reducing problematic alcohol use outcomes among college students.

Keywords: alcohol, social norms, personalized normative feedback, college students

Heavy drinking among college students is associated with a range of serious primary and secondary consequences (e.g., academic and psychological impairment, risky sexual behavior and victimization, car accidents, and violence ; Wechsler & Nelson, 2008; Hingson, Zha, & Weitzman, 2009). A considerable body of research confirms that behavioral decisions, such as the decision to drink heavily, are influenced by normative perceptions of significant referents’ behaviors and beliefs (Berkowitz, 2004; Borsari & Carey, 2003). For example, perceptions of peers’ drinking (descriptive norms) and attitudes toward drinking (injunctive norms) have been identified as among the strongest predictors of personal drinking behavior among college students (Neighbors, Lee, Lewis, Fossos, & Larimer, 2007; Perkins, 2002). Students commonly and consistently overestimate the amount of alcohol peers consume (Borsari & Carey, 2003; Lewis & Neighbors, 2004), with approximately seven in ten students overestimating the amount of alcohol consumed by typical students at their college (Perkins, Haines, & Rice, 2005).

Interventions to correct normative misperceptions can reduce drinking and negative consequences among college students (e.g., Bewick et al., 2010; LaBrie, Hummer, Neighbors, & Pedersen, 2008; Neighbors, Larimer, & Lewis, 2004; Walters, 2000). Personalized normative feedback (PNF) interventions, which attempt to correct normative misperceptions by presenting students with individually-delivered feedback comparing their personal drinking behavior, perceptions of peers’ drinking behavior (perceived descriptive norms), and peers’ actual drinking behavior (actual descriptive norms), have demonstrated considerable success in reducing normative perceptions and alcohol consumption in college student populations (Collins, Carey, & Sliwinsky, 2002; Cunningham, Humphreys, & Koski-Jannes, 2000; Lewis & Neighbors, 2006a; Murphy et al., 2004; Neighbors et al., 2004; Walters, 2000). In fact, several trials support the efficacy of stand-alone PNF interventions (for review, see Zisserson, Palfai, & Saitz, 2007), which have evidenced similar effect sizes compared to PNF delivered as part of multi-component interventions (Walters & Neighbors, 2005).

Despite the growing body of evidence in support of PNF-only interventions, questions remain regarding what level of specificity of referent is most effective. Moreover, limited data exists assessing the utility of web-based PNF outside of the laboratory, but the limited results suggest that this approach can lead to reductions in alcohol consumption (Bewick et al., 2010; Neighbors, Lewis, et al., 2010; Walters, Vader, & Harris, 2007). Web-based PNF has the potential to provide a cost-effective, standardized intervention that can be easily disseminated to large groups, while being appealing to college students who perceive this modality to be unobtrusive and convenient (Neighbors, Lewis et al., 2010; Riper et al., 2009). The current study aims to address this gap in the literature by examining the efficacy of web-based PNF using varying levels of reference group specificity.

Specificity of Normative Reference Group

The majority of PNF initiatives have used typical student normative referents (Collins et al., 2002; Murphy et al., 2004; Neighbors et al., 2004; Walters, 2000). However, recent research has indicated that increasing the specificity of normative reference groups (e.g., gender-specific) may enhance the efficacy of PNF interventions for certain individuals (Lewis & Neighbors, 2006a). This is consistent with theoretical perspectives that suggest more socially proximal and salient, as compared to more distal, social reference groups have a greater impact on an individual’s behavioral decisions (e.g., Social Comparison Theory, Festinger, 1954; Social Impact Theory, Latane, 1981). Indeed, researchers have found descriptive norms for more socially proximal referents (e.g., close friends, same-sex students) tend to be more strongly associated with alcohol consumption than those of “typical” or “average” students (Korcuska & Thombs, 2003; Lewis & Neighbors, 2004; Lewis, Neighbors, Oster-Aaland, Kirkeby, & Larimer, 2007). Furthermore, Larimer et al. (2009, 2011) reported that even at increasing levels of specificity (i.e., gender, ethnicity, residence), students overestimated descriptive normative drinking behaviors of proximal peers, and these misperceptions were uniquely related to personal drinking. Targeting more specific reference groups may be particularly effective in communicating feedback that closely resembles the individual respondent, thereby increasing the saliency, believability, and recognition of the information presented and, in turn, more strongly promoting positive behavioral change. The current study focused on normative reference groups derived from combinations of participants’ gender, race, and Greek status.

Gender and Greek specificity

Gender and Greek status are two levels of specificity that may influence the impact of PNF interventions. Men and women exhibit different drinking behaviors (Kypri, Langley, & Stephenson, 2005) and perceptions of normative beliefs (Lewis & Neighbors, 2004, 2006a; Suls & Green, 2003). Efficacy studies of gender-specific PNF have found inconsistent results. For example, Lewis and Neighbors (2007) did not find any overall differences in the short-term efficacy of gender-specific and non-gender specific PNF although both groups reported reductions in drinking compared to controls. However, gender-specific feedback worked better for women who identified more closely with their gender. Neighbors and Lewis et al. (2010) demonstrated PNF delivered biannually with gender-specific norms reduced weekly drinking, whereas non-gender specific and one-time only gender-specific norms did not.

Students affiliated with fraternities and sororities (Greek systems) hold significantly higher perceived and actual drinking norms (Carter & Kahnweiler, 2000) than non-Greek peers. Larimer et al. (2011) found Greek students’ perceived norms for referents that do not include Greek status tended to be close to, if not lower than, their own drinking behavior. However, Greek students presented with referents that did include Greek status overestimated normative drinking. As such, Greek-specific normative feedback may be particularly beneficial to Greeks, who appear amenable to normative feedback interventions (LaBrie et al., 2008; Larimer et al., 2001; Larimer, Turner, Mallett, & Geisner, 2004).

Ethnicity/race specificity

Currently, no studies have addressed the efficacy of race-specific PNF and limited data are available examining racial and ethnic differences in norms and their relationship to alcohol use (LaBrie, Atkins, Neighbors, Mirza & Larimer, 2012). The few studies that have examined ethnic- and race-specific reference groups suggest perceived norms vary based on the race specificity of the reference group (Larimer et al., 2009; Larimer et al., 2011) and perceived norms for same-ethnicity students are positively associated with drinking, particularly for those who identify most strongly with their ethnic group (Neighbors, LaBrie et al., 2010). The typical American college student is most often viewed as Caucasian, even among non-Caucasian students (Lewis & Neighbors, 2006b), thus perceived typical student norms may be less predictive of drinking among non-Caucasian students. Indeed, Stappenbeck, Quinn, Wetherill, and Fromme (2010) found that while Caucasian and Asian students do not differ in perceived typical student norms, generic norms were predictive of alcohol use and own social group norms for Caucasian, but not Asian students.

Taken together, these findings suggest that PNF interventions may benefit from providing race-specific feedback. The present study extends previous research by examining the impact of race-specific PNF among Caucasians students, the prototypical heavy drinking racial subgroup in college populations, and Asian American students. Although Asian Americans have higher rates of abstinence than other ethnic groups, Asian American adolescents who do drink have higher rates of binge drinking than any other ethnic group, and this racial subgroup exhibits escalating rates of heavy episodic drinking and alcohol abuse (Grant et al. 2004; Hahm, Lahiff & Guterman, 2004; Office of Applied Studies, 2008; Wechsler et al. 1998; 2002). These findings have led to calls for alcohol prevention efforts to specifically target this ethnic minority (e.g., Hahm et al., 2004; LaBrie, Lac, Kenney & Mirza, 2011). Thus, the current study focused on Asian students in order to contribute to prevention efforts for this understudied group, as well as to extend work of Stappenbeck and colleagues (2010) to evaluate the efficacy of typical student versus ethnic-specific feedback for diverse populations. We also selected Asian students, as they represent an ethnic minority population of sufficient size and with distinct drinking behavior and norms from the majority population to enable a strong test of our research questions.

Discrepancy of Actual Norm with Behavior and Perceptions

PNF approaches correct normative misperceptions by showing discrepancies between actual norms and students’ perceptions and behaviors in order to motivate behavior change (Rice, 2007). Presumably, for PNF to be effective, inaccurate beliefs must be present (Lewis & Neighbors, 2006a), and the greater the discrepancy between actual norms and perceived norms, and actual norms and behavior, the greater the potential impact of normative feedback (Larimer, Turner, Mallett, & Geisner, 2004). Larimer et al. (2011) examined the accuracy of students’ perceived norms using reference groups varying in similarity to the participant, including typical student and combinations of gender, race and Greek status. Participants rated the referent to have higher levels of alcohol consumption relative to their own drinking and, in general, as the referent became more similar, mean normative estimates generally decreased. Thus, the greatest discrepancy between perceived norms and actual norms occurred when the typical student referent was used. Although students may find specific normative information more relevant, compelling, and, therefore, motivating, the greater accuracy of descriptive norms for specific reference groups may reduce the discrepancy and decrease the motivating potential of normative feedback. The current study will examine whether intervention effects are mediated by discrepancies between actual norms, perceived norms, and drinking behavior.

Present Study

The current study compares the efficacy of web-based PNF using one of eight increasingly specific reference groups (typical student and gender-, race-, Greek status-, gender-race-, gender-Greek status-, race-Greek status-, gender-race-Greek status-specific) compared against a web-based motivational feedback intervention derived from the well-established BASICS intervention (Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students, Dimeff, Baer, Kivlahan, & Marlatt, 1999) and a generic feedback control. The Web-BASICS control provides an opportunity to examine whether addition of comprehensive feedback components offers any advantages over standalone PNF. While the generic control condition allows us to examine whether completing alcohol-related questionnaires and receiving non-alcohol related feedback could be responsible for intervention effects. We hypothesized that both PNF and Web-BASICS would outperform an assessment-only control condition in reducing risky drinking (number of weekly drinks, peak drinks in the past month, and days of drinking during the past month) and negative consequences of alcohol use. We further predicted that increasing levels of specificity of feedback would be more effective in reducing risky drinking and consequences such that PNF with 3-levels of specificity (same sex, same race, same Greek membership status) would outperform 2- and 1-levels and typical student feedback. Finally, we examined the role of discrepancy between drinking behavior, perceived descriptive norms and the actual drinking norm for each reference group as a mechanism of intervention efficacy.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Participants were undergraduate students from two west coast universities. A random list of enrolled students (N = 11,069; n1= 6495; n2=4574) was provided by the registrar’s office. Students were contacted via mail and email to participate in an online screening survey. Of participants contacted, 4,818 (43.5%) responded and completed the screening survey (60.2% female). Campus 1 (n1=3,034), a large, public university, has an enrollment of approximately 30,000 undergraduate students. Campus 2 (n2=1,784) is a mid-sized private university with enrollment of approximately 6,000 undergraduates. Participants were between 18–24 years old (M = 19.86, SD = 1.35). Racial composition was 50.7% Caucasian, 27.4% Asian, 10.7% Multiracial, 6.4% “Other”, 2.5% African American, 1.6% Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and 0.5% American Indian/Alaskan Native. Further, 10.9% self-identified as Hispanic. The screening samples were similar to the college populations from which they were drawn with respect to alcohol use. For example, a similar proportion of students reported that they did not drink on a typical week (Campus 1: 35.2% screening, 37.2% population; Campus 2: 25.7% screening sample and 27.7% population). In terms of demographics, females were slightly overrepresented in the screening sample (Campus 1: 56.7% screening, 51.6% population; Campus 2: 65.6% screening sample and 57.9% population), and White students were underrepresented in the Campus 1 sample (Campus 1: 45.7% screening, 56.6% population; Campus 2: 59.1% screening, 55.5% population).

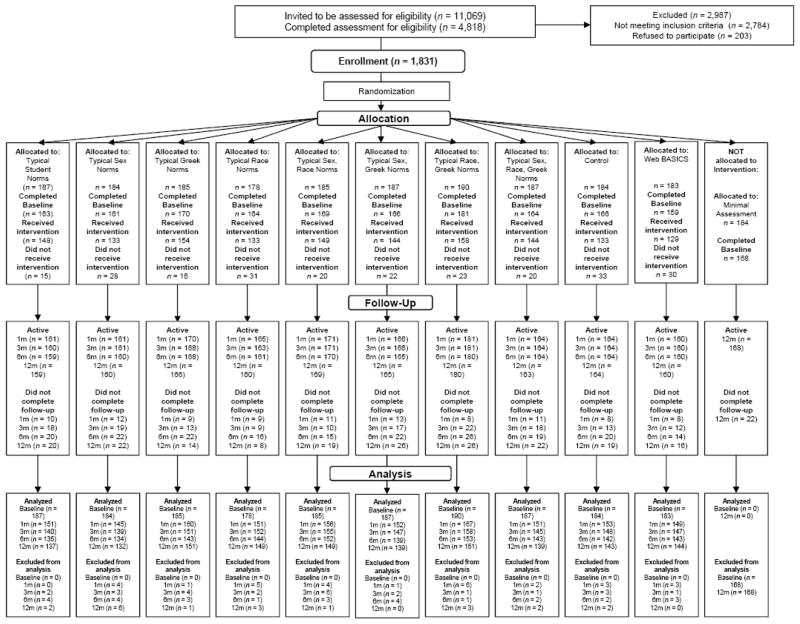

A total of 2,034 (42.2%) out of the 4,818 students who completed the screening survey met inclusion criteria for the current study. Inclusion criteria consisted of participants reporting a minimum of one past-month heavy episodic drinking event (HED; consuming at least four (for female) or five (for males) drinks during a drinking occasion), and identifying as either Caucasian or Asian. Of the 2,034 participants who met inclusion criteria, 1,831 (90%) students completed an online baseline survey and 1,663 were randomized to one of the 10 conditions reported on in this manuscript. Another condition (n = 168) was a minimal assessment control condition comprising students who did not participate in the 1-, 3- or 6-month follow-up periods and therefore was not included in the present analysis. Follow-up rates were 89.7% at one-month, 86.8% at three-months, 84% at 6-months, and 85.5% at 12-months. The final sample was 56.7% female, with a mean age of 19.92 years (SD = 1.3). The majority of the sample identified as Caucasian (75.7%) and did not belong to a sorority or fraternity (70.7%).

Study Design

The current study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of both participating universities and a Federal Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained to further protect research participants.

Screening

Students randomly selected from registrar rosters at both universities received mailed and emailed letters inviting their participation in a study of alcohol use and perceptions of drinking in college. The invitations included a URL to a 20-minute online screening survey, which gathered demographic, alcohol use, and descriptive and injunctive norms data. Screening survey completers received a $15 stipend.

Baseline

Students completing the screening survey who met inclusion criteria were immediately invited to participate in the longitudinal trial. Students were presented with a web invitation, which provided a URL directing them to the baseline survey. The baseline survey included additional measures related to study hypotheses such as an assessment of negative consequences of drinking. Baseline survey completers received a $25 stipend. Upon completion of the baseline survey, students were randomly assigned to one of the 10 treatment conditions using a web-based algorithm. A stratified, block randomization was used (Hedden, Woolson, & Malcolm, 2006), in which assignment was stratified by Greek organization membership (yes/no), sex (male/female), race (Asian/Caucasian), and total drinks per week (10 or less, 11 or more). Thus, each treatment condition was comprised of approximately 82 men and 100 women, 43 Asian-Americans and 139 Caucasians, and 55 Greek-affiliated students and 127 non-Greek students.

Personalized normative feedback intervention

Of the ten conditions examined in the present study, eight provided normative feedback based on differing levels of specificity of the reference group. Condition 1 was provided normative information about the typical student at the same university. Conditions 2 thru 4 were provided matched normative information at one level of specificity based on the participant’s gender, Greek status, or race. Conditions 5 thru 7 were presented two levels of specificity for students at the same university matched to participant’s gender and race (e.g., typical female Asian), gender and Greek status (e.g., typical male Greek-affiliated student), or race and Greek status (e.g., typical Caucasian Greek-affiliated student). The eighth condition provided participants with three levels of specificity for students at the same university matched to participant’s gender, race and Greek status (e.g., typical female, Asian, Greek-affiliated student). A ninth condition presented Web-BASICS (Dimeff et al., 1999). Finally, the tenth condition was a repeated assessment control group which received generic non-alcohol related normative feedback about the typical student’s frequency of text messaging, downloading music, and playing video games on their campus.

After completing the baseline survey, participants were immediately provided with Web-based feedback, depending on their randomized condition. Three feedback categories were used: Personalized Normative Feedback (PNF, conditions 1–8 described above), Web-BASICS (condition 9), and generic control feedback (condition 10). Participants were given the option to print their feedback.

Personalized normative feedback

The PNF contained four pages of information in text and bar graph format. Separate graphs, each including three bars, were used to present information regarding the number of drinking days per week, average drinks per occasion, and total average drinks per week for (a) one’s own drinking behavior, (b) their reported perceptions of the reference group’s drinking behavior on their respective campus, at the level of specificity defined by their assigned intervention condition, and (c) actual college student drinking norms for the specified reference group. Actual norms were derived from large representative surveys conducted on each campus in the prior year as a formative step in the trial. Participants were also provided with their percentile rank comparing them with other students on their respective campus for the specified reference group (e.g., “Your percentile rank is 99%, this means that you drink as much or more than 99% of other college students on your campus”).

Web-BASICS feedback

The Web-BASICS feedback contained a total of twenty-six pages of interactive comprehensive motivational information based on assessment results, modeled from the efficacious in-person BASICS intervention (Dimeff et al., 1999; Larimer et al., 2001). It addressed quantity and frequency of alcohol use, past month peak alcohol consumption, estimated blood alcohol content (BAC), and provided information regarding standard drink size, how alcohol affects men and women differently, oxidation, alcohol effects, reported alcohol-related experiences, estimated calories and financial costs based on reported weekly use, estimated level of tolerance, risks based on family history, risks for alcohol problems, and tips for reducing risks while drinking as well as alternatives to drinking. The feedback also included PNF utilizing typical student drinking norms. Participants were given the option to click links throughout the feedback to obtain additional information on standard drink size, sex differences and alcohol use, oxidation, biphasic tips, hangovers, alcohol costs, tolerance, and protective factors, as well as provided with a link to a BAC calculator.

Generic control feedback

The generic control feedback, which was presented to those in the assessment control condition, contained three pages of information in text and bar graph format. Separate graphs, each including two bars, were used to present information regarding the number of hours spent texting, number of hours spent downloading music, and number of hours spent playing video games per week for (a) one’s own behavior, and (b) actual college student behavior. Participants were also provided with their percentile rank comparing them with other students on their respective campus (e.g., “Your percentile rank is 60%, this means that you text as much or more than 60% of other college students on your campus”).

Follow-up

To assess intervention efficacy, participants were invited to take a series of online follow-up surveys at one-, three-, six-, and 12-month time-points after their online intervention. Participants received $30 for completing the one-, three- and six-month follow-up surveys and $40 for completing the 12-month follow-up survey. Additionally, students who completed all surveys received a bonus check of $30 at the end of the study.

Measures

All measures were completed at screening/baseline, one-, three-, six-, and 12-month follow-up. A standard drink definition was included for all alcohol consumption measures (i.e., 12 oz. beer, 10 oz. wine cooler, 4 oz. wine, 1 oz. 100 proof [1 ¼ oz. 80 proof] liquor).

Demographics

The initial section of the screening survey asked participants to report their birth sex, race and Greek status.

Alcohol consumption

The Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985; Kivlahan et al., 1990) measured one of the primary outcomes: the number of drinks per week. Students were asked to consider a typical week in the last month and indicate the number of drinks they typically consumed on each day of the week. Students’ responses were summed across each of the seven days to form a composite of total weekly drinks.

The Quantity/Frequency Index is an assessment of alcohol use (Baer, 1993) that measures participant’s drinking during the past month. Participants were asked to think about the occasion when they drank the most and to report how many drinks they consumed on that occasion. In addition, participants reported how many days they drank alcohol in the past month. Response options ranged from 0 (I do not drink at all) to 7 (Every day).

Descriptive norms

The Drinking Norms Rating Form (DNRF; Baer, Stacy, & Larimer, 1991) assessed participants’ perception of the number of drinks consumed each day of the week by a typical student at one’s university and at varying levels of reference group specificity. The levels of specificity referred to a typical student’s gender, race, and Greek status and all combinations of the tree, resulting in eight reference groups for each question.

Alcohol-related negative consequences

The 25-item Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI; White & Labouvie, 1989) assessed the frequency of alcohol-related negative consequences. Response options ranged from 0 (never) to 4 (10 or more times). The items included “Passed out or fainted suddenly”, “Caused shame or embarrassment to someone” and “Felt physically or psychologically dependent on alcohol”. Items were summed to create a composite score for the analysis.

Data Analyses

The first two hypotheses examining the efficacy of PNF compared to web-BASICS and Control conditions, and the efficacy of PNF conditions varying in specificity of feedback, were tested using a quasi-Poisson generalized linear model fit by generalized estimating equations (GEE; Liang & Zeger, 1986). The primary outcomes included number of drinks consumed per week, peak drinks in the past month, drinking days during the past month, and total number of alcohol-related problems. Each of these outcomes represents a type of count variable. Count variables have certain properties (e.g., bounded at zero, integer scaling) that make them ill-suited for statistical methods that assume normality and are more appropriately modeled by count regression methods (see Atkins & Gallop, 2007). Poisson GEE models are appropriate for clustered or longitudinal count data and control for correlated data through estimating a working correlation matrix of the residuals and using robust, cluster-adjusted SE. However, the basic Poisson GEE assumes that the mean of the outcome is equal to its variance (conditional on the covariates). This is often violated in real-world data, leading to a condition called over-dispersion, which yields biased standard errors and statistical tests (Hilbe, 2011). The quasi-Poisson GEE is a semi-parametric mean model that incorporates an over-dispersion parameter, yielding unbiased variance estimates in the presence of over-dispersion.

The predictors were connected to the outcome through a natural logarithm link function, which is the standard link function for Poisson models and other count regression methods. To interpret quasi-Poisson regression models, the coefficients are typically exponentiated (i.e., eB) to yield rate ratios (RR). Like odds-ratios in logistic regression, a value of one is a null value for RRs (i.e., no effect), and RRs larger than one are interpreted as a percentage increase in counts (for each unit increase in the predictor). Conversely, RRs less than one are interpreted as percentage decreases in the outcome (for each unit decrease in the predictor).

The basic quasi-Poisson model used to test primary hypotheses (using the DDQ outcome as an example) was:

| (1) |

As seen in Equation 1, the baseline level of the outcome was included as a covariate in all analyses, which increases the efficiency of the model (i.e., reduces SE for treatment contrasts and other terms), and a participant’s outcome in the regression models included their values of the outcome at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months post-baseline. Time was modeled as a linear association with outcomes, which was confirmed through sensitivity analyses that allowed more flexible, nonlinear associations. In Equation 1, a single treatment indicator is shown (Tx), but in analyses this was replaced by appropriate treatment contrasts, described below in Results. Randomization excluded the possibility of baseline confounders, and there were no concerns about treatment comparability at baseline. Hence, models did not adjust for additional covariates. The proportion of missing data were consistent across treatment conditions (see CONSORT chart), and sensitivity analysis found no differences based on missing data status. A priori power analyses given the current design indicated that treatment condition sample sizes of n = 141 or greater (accounting for planned attrition of 20%) would yield power of .80 or better to detect treatment contrasts of d = 0.20 (e.g., small effect sizes). All analyses were done in R v2.11.1 (R Development Core Team, 2010).

Results

Descriptive Analyses

Participants in the RCT sample reported consuming an average of 11.03 drinks (SD = 9.5; males M = 14.23, SD = 11.5; females M = 8.58, SD = 6.6) in a typical week. Further, on the occasion on which participants drank the most in the past month, they reported drinking an average of 8.77 drinks (SD = 4.1; males M = 10.68, SD = 4.3; females M = 7.31, SD = 3.2) on a single occasion. Table 1 has descriptive statistics for each of the 10 treatment conditions (i.e., all PNF conditions are reported separately).

Table 1.

Mean Drinking and Consequences Outcomes for Different Treatment Groups at 5 Time Points.

| Control | Web- BASICS | PNF Typ | PNF Ra | PNF Gn | PNF Gr | PNF Ra/Gr | PNF Gn/Ra | PNF Gn/Gr | PNF Gn/Ra/Gr | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak number of drinks | ||||||||||

| Baseline | 8.8 (3.9) | 8.6 (3.7) | 8.2 (3.8) | 8.8 (4.1) | 8.5 (4.1) | 8.8 (4.2) | 9.1 (3.8) | 8.5 (4.2) | 8.3 (3.7) | 8.5 (4.0) |

| 1 month | 7.4 (4.7) | 7.2 (4.2) | 6.6 (4.1) | 6.9 (4.3) | 7.8 (4.5) | 7.9 (4.2) | 7.7 (5.0) | 7.5 (4.7) | 7.2 (4.2) | 7.5 (4.6) |

| 3 months | 7.2 (4.2) | 7.0 (4.2) | 6.3 (3.4) | 7.0 (4.9) | 7.2 (4.4) | 8.1 (4.7) | 7.4 (4.3) | 7.5 (4.4) | 7.2 (4.6) | 6.7 (3.7) |

| 6 months | 7.4 (4.4) | 6.8 (4.2) | 6.2 (4.4) | 6.8 (4.9) | 7.6 (4.7) | 7.5 (4.4) | 7.3 (4.1) | 7.0 (4.7) | 6.6 (4.5) | 7.2 (4.2) |

| 12 months | 7.1 (3.9) | 7.0 (4.2) | 6.5 (4.2) | 6.7 (4.2) | 7.5 (4.3) | 7.8 (4.5) | 6.7 (4.3) | 7.0 (3.7) | 7.0 (4.7) | 6.6 (4.3) |

| Number of days drinking | ||||||||||

| Baseline | 6.3 (4.3) | 6.7 (4.7) | 6.5 (4.7) | 7. 6 (5.7) | 6.3 (4.6) | 6.9 (4.5) | 6.3 (4.1) | 6.4 (4.7) | 6.5 (4.8) | 6.5 (4.7) |

| 1 month | 6.1 (4.7) | 5.9 (4.8) | 5.2 (4.1) | 6.1 (4.9) | 5.5 (4.9) | 5.7 (4.4) | 5. 7 (4.1) | 5.6 (4.2) | 6.2 (5.0) | 6.0 (5.4) |

| 3 months | 5.9 (4.4) | 5.7 (4.3) | 5.3 (4.1) | 6.2 (5.5) | 5.5 (4.3) | 6.0 (4.4) | 5.3 (3.6) | 5.7 (4.3) | 6.3 (5.0) | 5.5 (4.4) |

| 6 months | 6.0 (4.5) | 5.9 (4.4) | 5.0 (3.8) | 6.1 (5.5) | 5.8 (4.6) | 6.0 (4.6) | 5.9 (4.9) | 5.8 (4.3) | 5.6 (5.3) | 6.2 (4.9) |

| 12 months | 6.2 (4.8) | 6.0 (4.7) | 5.8 (4.9) | 5.7 (5.1) | 5.8 (4.4) | 6.3 (4.9) | 6.2 (5.2) | 6.3 (5.1) | 5.8 (5.2) | 6.0 (5.1) |

| Total weekly drinks | ||||||||||

| Baseline | 10.4 (9.5) | 10.7 (8.1) | 10.3 (10.0) | 11.4 (9.8) | 10.2 (8.5) | 11.8 (9.4) | 11.5 (10.1) | 10.6 (9.1) | 9.9 (7.7) | 10.3 (9.4) |

| 1 month | 10. 1 (10.0) | 9.3 (7.9) | 8.4 (6.9) | 9.7 (9.4) | 9.4 (9.9) | 10.0 (8.0) | 9.7 (7.6) | 9.4 (8.6) | 8.8 (7.3) | 9.1 (8.3) |

| 3 months | 9.6 (9.6) | 9.0 (8.0) | 7.5 (6.5) | 8.8 (9.5) | 9.3 (9.1) | 9.8 (7.7) | 9.0 (7.8) | 9.5 (8.3) | 9.2 (9.1) | 8.4 (7.9) |

| 6 months | 9.4 (10.2) | 9.4 (8.3) | 7.5 (7.3) | 10.0 (10.9) | 10.5 (11.7) | 9.8 (8.2) | 9.4 (8.8) | 8.8 (8.1) | 7.8 (8.1) | 9.5 (9.1) |

| 12 months | 9.0 (8.4) | 8.5 (8.7) | 7.9 (6.9) | 8.4 (8.1) | 9.9 (9.2) | 9.9 (9.4) | 8.9 (7.8) | 8.7 (7.1) | 7.7 (6.4) | 8.5 (9.1) |

| Negative consequences | ||||||||||

| Baseline | 3.3 (3.4) | 4.4 (5.8) | 3.9 (5.1) | 3.8 (4.3) | 4.1 (4.7) | 4.8 (5.3) | 3. 9 (4.3) | 4.3 (5.7) | 4.1 (4.4) | 3.4 (3.6) |

| 1 month | 3.4 (6.1) | 4.0 (7.6) | 3.1 (5.9) | 3.9 (6.2) | 3.7 (5.7) | 3.3 (3.9) | 3.3 (4.5) | 4.3 (8.1) | 3.3 (5.0) | 3.2 (4.2) |

| 3 months | 4.3 (8.9) | 4.5 (8.5) | 3.7 (10.4) | 3.5 (6.3) | 3.6 (5.1) | 3.5 (4.8) | 3.7 (5.3) | 3.9 (6.8) | 4.0 (9.0) | 3.0 (6.2) |

| 6 months | 2.8 (5.4) | 4.8 (8.6) | 2.3 (4.3) | 4.3 (8.1) | 3.9 (6.5) | 4.4 (7.4) | 3.7 (7.0) | 3.8 (7.5) | 4.4 (11.5) | 2.6 (3.9) |

| 12 months | 2.6 (5.0) | 3.7 (7.6) | 2.4 (4.1) | 3.5 (7.5) | 2.6 (4.0) | 4.0 (8.5) | 3.3 (6.2) | 4.3 (9.2) | 3.4 (8.4) | 2.3 (4.5) |

Note. Standard deviations are presented in parentheses. Typ = Typical student referent; Ra = Race specific referent; Gn = gender specific referent; Gr = Greek specific referent; Ra/Gr = Race/Greek specific referent; Gn/Ra = Gender/Race specific referent; Gn/Gr = Gender / Greek specific referent; Gn/Ra/Gr = Gender / Race / Greek specific referent.

Quasi-Poisson GEE Analyses of Control vs. Web-BASICS vs. PNF

Initial inferential statistics focused on treatment comparisons between control, Web-BASICS, and PNF (considered as a single group). As noted earlier, a quasi-Poisson GEE model was fit that included time, indicator variables for Web-BASICS and PNF (compared to control), and the outcome measured at baseline. A model including interactions between time and treatment conditions was examined. These interactions were not significant indicating that all change occurred from baseline to one month with little change following that, and thus, the simpler model was retained including main effects for treatment and time. Moderation of intervention effects by demographic variable (e.g., race, gender and Greek membership) were also non-significant. RRs and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for RRs are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Rate Ratios (RR) and 95% Confidence Intervals for RR From Quasi-Poisson GEE Comparing Control, BASICS, and PNF Participants From One to Twelve Months

| RR | 95% CI

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||

| Peak number of drinks | |||

| Intercept | 7.093 | 7.071 | 7.114 |

| WebBASIC | 0.975 | 0.969 | 0.981 |

| PNF | 0.988 | 0.985 | 0.991 |

| Time (month) | 0.996 | 0.996 | 0.996 |

| Baseline peak drinks | 1.072 | 1.072 | 1.072 |

| Number of days drinking | |||

| Intercept | 1.433 | 1.428 | 1.438 |

| WebBASIC | 0.923 | 0.917 | 0.930 |

| PNF | 0.919 | 0.916 | 0.923 |

| Time (month) | 1.004 | 1.004 | 1.004 |

| Baseline days drinking | 1.356 | 1.356 | 1.356 |

| Total weekly drinks | |||

| Intercept | 8.706 | 8.640 | 8.773 |

| WebBASIC | 0.997 | 0.983 | 1.011 |

| PNF | 0.960 | 0.952 | 0.968 |

| Time (month) | 0.994 | 0.994 | 0.994 |

| Baseline total weekly drink | 1.044 | 1.044 | 1.044 |

| Negative consequences | |||

| Intercept | 3.523 | 3.410 | 3.641 |

| WebBASIC | 1.047 | 0.969 | 1.132 |

| PNF | 0.955 | 0.922 | 0.990 |

| Time (month) | 0.990 | 0.990 | 0.990 |

| Baseline consequences | 1.076 | 1.076 | 1.076 |

Note. Baseline = Pre-intervention value of the outcome for each outcome; CI = confidence interval.

Focusing on total weekly drinking, the intercept term is the estimate of drinking for control participants at baseline (i.e., time = 0) because of the coding of the indicator variables. The RR for that term provides the average outcome for this group (e.g., the mean total drinks per week is 8.7 in control group). The effect for time presents the adjusted common change across time (i.e., there is approximately 0.6% decrease in drinks per week every month post intervention in the control group). Compared to the control group, PNF participants showed a 4% reduction in average total drinks, significantly lower than control participants. The Web-BASICS and control conditions were not significantly different from one another. Findings for the other three outcomes are broadly similar: PNF participants reported significantly less peak drinking, drinking days, and drinking-related problems (RAPI) relative to control participants. However, in each case the differences are modest (between 1% and 8%). Web-BASICS participants reported significantly lower peak drinking and total drinking days relative to control, but RAPI scores were similar between the two groups. Finally, contrasts examined whether there were differences between the two active treatment groups (combined PNF = 0, web-BASICS = 1) and they revealed no significant differences for total weekly drinks (RR = 0.96, 95% CI: 0.85, 1.09), peak drinks (RR = 1.01, 95% CI: 0.94, 1.10), total drinking days (RR = 1.00, 95% CI: 0.91, 1.09), and drinking related problems (RR = 0.91, 95% CI: 0.67, 1.25).

Quasi-Poisson GEE of Individual PNF Conditions

We next examined whether a more specific comparison group with PNF might yield better treatment outcomes relative to a generic “typical” student comparison group. Using only the eight PNF conditions, a quasi-Poisson GEE examined whether greater specificity in the normative reference group would lead to greater reductions in drinking. Table 3 presents RR and 95% CI for RR for comparisons among PNF conditions. No PNF condition led to greater change over time in any of the four outcomes as compared to typical student feedback. Surprisingly, just the opposite was found: All RRs comparing more specific PNF references to typical student were greater than 1, and virtually all were significant. Thus, more specific PNF conditions achieved reliably worse results compared to typical student feedback.

Table 3.

Rate Ratios (RR) and 95% Confidence Intervals for RR From Quasi-Poisson GEE Comparing Typical Student PNF to More Specific PNF Conditions From One to Twelve Months

| Variable | RR | 95% CI

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||

| Peak number of drinks | |||

| Intercept | 6.526 | 6.512 | 6.541 |

| PNF Ra | 1.009 | 1.004 | 1.014 |

| PNF Gn | 1.131 | 1.126 | 1.137 |

| PNF Gr | 1.151 | 1.146 | 1.155 |

| PNF Ra/Gr | 1.061 | 1.057 | 1.066 |

| PNF Ra/Gn | 1.093 | 1.088 | 1.098 |

| PNF Gn/Gr | 1.085 | 1.079 | 1.091 |

| PNF Ra/Gn/Gr | 1.059 | 1.054 | 1.064 |

| Time (month) | 0.995 | 0.995 | 0.995 |

| Baseline peak drinks | 1.073 | 1.073 | 1.073 |

| Number of days drinking | |||

| Intercept | 1.224 | 1.219 | 1.230 |

| PNF Ra | 1.003 | 0.995 | 1.012 |

| PNF Gn | 1.082 | 1.074 | 1.091 |

| PNF Gr | 1.104 | 1.096 | 1.112 |

| PNF Ra/Gr | 1.122 | 1.114 | 1.131 |

| PNF Ra/Gn | 1.093 | 1.084 | 1.102 |

| PNF Gn/Gr | 1.113 | 1.101 | 1.125 |

| PNF Ra/Gn/Gr | 1.107 | 1.097 | 1.117 |

| Time (month) | 1.004 | 1.004 | 1.004 |

| Baseline days drinking | 1.354 | 1.354 | 1.355 |

| Negative consequences | |||

| Intercept | 2.712 | 2.624 | 2.803 |

| PNF Ra | 1.381 | 1.300 | 1.467 |

| PNF Gn | 1.214 | 1.155 | 1.276 |

| PNF Gr | 1.230 | 1.162 | 1.303 |

| PNF Ra/Gr | 1.272 | 1.208 | 1.338 |

| PNF Ra/Gn | 1.223 | 1.135 | 1.318 |

| PNF Gn/Gr | 1.338 | 1.257 | 1.425 |

| PNF Ra/Gn/Gr | 1.061 | 1.006 | 1.118 |

| Time (month) | 0.993 | 0.993 | 0.993 |

| Baseline Consequences | 1.078 | 1.078 | 1.078 |

| Total weekly drinks | |||

| Intercept | 7.022 | 6.959 | 7.086 |

| PNF Ra | 1.156 | 1.138 | 1.174 |

| PNF Gn | 1.340 | 1.317 | 1.363 |

| PNF Gr | 1.246 | 1.228 | 1.263 |

| PNF Ra/Gr | 1.141 | 1.121 | 1.161 |

| PNF Ra/Gn | 1.192 | 1.175 | 1.208 |

| PNF Gn/Gr | 1.193 | 1.176 | 1.210 |

| PNF Ra/Gn/Gr | 1.185 | 1.166 | 1.204 |

| Time (month) | 0.995 | 0.995 | 0.995 |

| Baseline total weekly drinks | 1.046 | 1.046 | 1.046 |

Note. CI = confidence interval; Ra = Race specific referent; Gn = gender specific referent; Gr = Greek specific referent; Ra/Gr = Race/Greek specific referent; Gn/Ra = Gender/Race specific referent; Gn/Gr = Gender / Greek specific referent; Gn/Ra/Gr = Gender / Race / Greek specific referent.

Treatment Mediators and Mechanisms

Several analyses examined possible mediators or mechanisms for why typical student feedback might be superior to feedback with more specific reference groups, focusing on total drinks per week during follow-up, as in the earlier PNF-focused treatment analyses. The perceived descriptive drinking norm (measured as the average rating on the DNRF across reference groups at each time) was considered as a mediator of treatment efficacy. The approach to mediation was similar to the classic approach to mediation, in which a total effect of treatment is decomposed into a direct effect of treatment and indirect effect through the mediator. However, we used a bootstrapped, nonparametric method for estimating the quantities (Imai, Keele, & Tingley, 2010). Table 4 shows results for mediation analyses, comparing each of the other seven PNF conditions to typical student PNF. The total effect column reports the estimated mean difference in total weekly drinks between typical student PNF and the specified treatment condition (i.e., basic treatment difference expressed as estimated mean difference), and the indirect effect column reports the amount of the total effect that can be explained by the indirect pathway through the DNRF. These results show that changes in the DNRF account for 11%–51% of the treatment superiority of the typical student PNF relative to other PNF conditions.

Table 4.

Mediation results for DNRF and two different types of discrepancy

| Variable | Total Effect | Indirect Effect | Pct. |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNRF | |||

| PNF Gn | 1.97 | 0.48 | 24% |

| PNF Ra | 0.96 | 0.12 | 13% |

| PNF Gr | 1.98 | 0.41 | 21% |

| PNF Gn/Ra | 1.12 | 0.13 | 11% |

| PNF Gn/Gr | 0.99 | 0.29 | 29% |

| PNF Ra/Gr | 0.98 | 0.32 | 33% |

| PNF Gn/Ra/Gr | 0.92 | 0.47 | 51% |

| Discrepency = Total weekly drinks − Norm | |||

| PNF Gn | 2.00 | 0.07 | 4% |

| PNF Ra | 0.91 | 0.04 | 5% |

| PNF Gr | 1.81 | 0.10 | 5% |

| PNF Gn/Ra | 1.12 | 0.06 | 5% |

| PNF Gn/Gr | 1.18 | 0.02 | 2% |

| PNF Ra/Gr | 0.89 | 0.09 | 11% |

| PNF Gn/Ra/Gr | 0.79 | 0.11 | 13% |

| Discrepency = DNRF − Norm | |||

| PNF Gn | 1.81 | 0.14 | 8% |

| PNF Ra | 0.76 | 0.01 | 1% |

| PNF Gr | 1.40 | 0.28 | 20% |

| PNF Gn/Ra | 0.90 | −0.12 | 13% |

| PNF Gn/Gr | 0.92 | 0.08 | 8% |

| PNF Ra/Gr | 0.67 | 0.09 | 14% |

| PNF Gn/Ra/Gr | 0.52 | 0.16 | 31% |

Note. Total effect is model based estimates of treatment differences in total drinks per week of each PNF condition relative to PNF typical student drinking condition. Indirect effect is the amount of the treatment difference attributable to the mediator. Pct. = Percent of total effect attributable to mediator (or indirect effect as a percentage of total effect); Ra = Race specific referent; Gn = gender specific referent; Gr = Greek specific referent; Ra/Gr = Race/Greek specific referent; Gn/Ra = Gender/Race specific referent; Gn/Gr = Gender / Greek specific referent; Gn/Ra/Gr = Gender / Race / Greek specific referent.

The putative mechanisms of personalized normative feedback include the discrepancy between the individual’s own drinking and the actual descriptive drinking norm they are provided during the feedback, as well as the discrepancy between their perception of the norm (i.e., DNRF) and the norm provided during feedback. Conceptually, we consider these to be treatment mechanisms, as opposed to mediators or moderators. They are not moderators as they are directly manipulated as part of the treatment, but they are also not traditional mediators because the treatment does not influence the discrepancy but rather the discrepancy is part of the intervention itself. However, if the pragmatic goal is to separate the effect of treatment content (i.e., discrepancy) and treatment type, then analytically, we can consider discrepancy as a mediator to achieve this aim. Results are shown in Table 4.

Approximately 5% of the total effect (i.e., estimated mean treatment difference) can be explained by the discrepancy with one’s own drinking and even less by the discrepancy with perceived norm. Thus, relative to the DNRF as a mediator, these treatment mechanisms appear somewhat weaker explanations for the treatment difference. Considering the indirect effect as a percentage change in the treatment difference, there is a 2.9% (CI: 2.4%–3.5%, p < .001) change in total drinks per week with each unit change in DNRF, a 14% (CI: 12%–18%, p < .001) change in total drinks per week with each unit change in discrepancy with one’s own drinking, and a 0.4% (CI: 0.0%–0.9% p = 0.57) change in total drinks per week with each unit change in discrepancy with perceived norm. Thus, in understanding the difference between typical student feedback vs. more specific PNF, both DNRF and discrepancy with own drinking appear to significantly affect the treatment differences. In summary, typical student PNF appears to yield greater changes in typical weekly drinking in part by having greater influence on perceptions of descriptive norms (i.e., DNRF) as well as generating a larger discrepancy with the student’s own drinking relative to other PNF conditions.

Discussion

The present study evaluated the efficacy of web-based PNF in reducing drinking and alcohol-related negative consequences relative to an active comparison condition (Web-BASICS) and a control condition. Relative to the control condition, PNF (considered as a single group) was associated with reductions in each of the four outcomes (number of weekly drinks, peak drinks, days of drinking, and number of alcohol-related problems). However, the effects of the web-based PNF were modest, with reductions ranging from a 1.0% decrease in number of drinking days to an 8.1% decrease in maximum number of drinks consumed on one occasion. PNF appeared to have more of an effect on the amount students drank (total drinks and peak drinks) than on drinking frequency. Further, compared to control, Web-BASICS was associated with a decrease in number of drinking days (2.5%) and peak number of drinks, but no change in number of alcohol-related negative consequences at the 12-month assessment.

Findings also indicated that the PNF (when considered as a single group) and Web-BASICS interventions did not differ significantly from each other, which suggests that a brief web-based PNF intervention with a focus only on normative comparisons is as efficacious as a more inclusive Web-BASICS intervention that focuses on normative comparisons in addition to a wide range of other feedback components (e.g., Blood Alcohol, Content, expectancies, protective behavioral strategies). Because both interventions were comparable at 12 months a more parsimonious PNF intervention might be a preference over a more inclusive BASICS intervention, at least with respect to web-based interventions. It is worth noting that Web-BASICS includes PNF feedback. The absence of differences may suggest that components within Web-BASICS other than PNF (e.g., expectancy information, review of risk factors, review of consequences experienced) may not offer unique impact over and above PNF.

The current study also extends existing research by examining the influence of specificity of normative referent group on the efficacy of web-based PNF. In contrast to expectations, the PNF intervention was most effective when the typical student (i.e., least specific normative referent) was used as the normative reference group. Thus, students who engaged in heavy episodic drinking and were given personalized information highlighting the discrepancy between their own drinking behavior, their perception of typical student drinking norms, and the actual drinking behavior of the typical student, reduced their drinking more and experienced fewer negative consequences than when they were given personalized information relative to the drinking behavior of more specific normative referent groups. For example, on average, heavy drinking Asian men and Greek women reduced their drinking more when they were compared with the typical student rather than with the typical Asian male student or the typical Greek female student.

Mediation analyses indicated that typical student PNF was associated with greater changes in typical weekly drinking, in part, by having a stronger influence on descriptive normative perceptions. Thus, typical student PNF resulted in a greater discrepancy with a student’s own drinking relative to other PNF conditions. One plausible explanation as to why PNF that utilized the typical student normative referent was more efficacious is that participants may be more likely to project characteristics that they felt were important or that generalize to a drinking college student onto the non-descriptive typical student referent rather than having those characteristics selected for them. Previous research has shown that students often perceive the typical student as different from themselves (Lewis & Neighbors, 2006b; e.g., the typical student is perceived as male and Caucasian). Greater discrepancies may arise from students’ inability to fully envision or define the “typical student.” Along with projecting characteristics onto this blank slate that may be important to the individual, students may also find it easy to project the highly salient and prototypical behavior of a heavy drinking college student (hence the largest perceived norms for this group). In this way, the discrepancy becomes larger as does the relative importance of the typical student. Students may be more likely to think about how their drinking relates to other students in general rather than other students who share their specific demographic characteristics. The combination of the two projection effects may result in more compelling feedback, thus promoting greater cognitive dissonance between perceived norms, actual norms and an individual’s own behavior. Under the tenets of social norms theory, this dissonance would produce greater change. In contrast, students’ schema for drinking norms may not extend to very specific subgroups and the additional complexity of proximally specific reference information may undermine the otherwise straightforward message conveyed by PNF. Students may feel more confident in their knowledge of the drinking norms of more specific groups, and the lack of a large discrepancy may further reduce the potential for change despite what is theoretically purported to be more meaningful and influential feedback.

While typical student PNF outperformed more specific PNF conditions in this trial, this does not rule out the importance of considering group characteristics or social identity in the context of norms-based interventions. Perhaps if the feedback highlighted the salience of the participant’s membership to the more relevant referent group it would have been more efficacious compared to PNF about the typical student. More specific reference groups may be more influential only when they are also accompanied by identification with those groups. Recent studies have shown that the association between perceived norms for specific reference groups and drinking behavior is moderated by degree of identification with, or feelings of connectedness to, the group in question (Hummer, LaBrie, & Pedersen, 2012; Reed, Lange, Ketchie, & Clapp, 2007; Neighbors, LaBrie et al., 2010). There is considerable variability in the extent to which individuals identify with others who share their demographic characteristics. Furthermore, individuals may identify strongly with one or two demographic dimensions and not at all with others. For example, an Asian sorority woman may strongly identify with her gender and sorority but not her race, or with her race but not her gender or sorority. Thus, specificity of the reference group in normative feedback may only matter to the extent that it is matched to group identification. This explanation is consistent with Lewis and Neighbors (2007) study in which gender specific normative feedback was only more effective than gender non-specific normative feedback for women who identified more strongly with their gender. Additional research is needed to evaluate the efficacy of self-defined important normative referents.

Another consideration is the feedback in this study was provided remotely on the web. Previous studies have demonstrated larger effects of computer based PNF when students are required to come in to the lab (Neighbors, Lewis et al., 2010). This may be due in part to competing demands for attentional resources while students consider estimates for drinking norms and/or review PNF. Students may pay less attention while completing web-based interventions; they may be simultaneously talking on the phone, texting, watching television, etc., whereas they would be less likely to engage in distracting activities in a lab-based intervention. If the influence of specificity of norms feedback requires more attention to the material, then we would expect a greater likelihood of effects in a more controlled setting.

Regardless of why we did not find strong effects for PNF that used more specific normative referents, the present findings suggest that web-based PNF that utilizes the typical student referent group may be an optimal choice and has the added advantage of being more parsimonious for college personnel in collecting norms and designing feedback interventions.

Clinical Implications

In the current study, both Web-BASICS and PNF interventions delivered via web are associated with reduced drinking through 12-month follow-up, and PNF is also associated with reduced negative consequences. Although these reductions are relatively small in magnitude, from a public health perspective the very low-cost and easy-to-implement typical student PNF is associated with sustained reductions and therefore has broad potential for large-scale implementation. This intervention can be implemented with comparable or fewer resources than are currently utilized for educational or awareness campaigns shown to be ineffective for college drinking prevention (Larimer & Cronce, 2007; Cronce & Larimer, 2011). In the current study, there was no significant advantage of the more comprehensive Web-BASICS intervention relative to PNF alone, providing additional evidence that more is not necessarily better (Kulesza, Apperson, Larimer, & Copeland, 2010; Wutzke, Conigrave, Saunders, & Hall, 2002). More research is needed to evaluate potential moderators of efficacy of web-BASICS and PNF, as well as moderators of more specific versus less-specific PNF feedback efficacy. Nonetheless, the current findings are encouraging, and provide further evidence that a low-cost, low-complexity PNF intervention can demonstrate lasting effects on student drinking.

Limitations/Future Directions

This study is not without limitations. One of the most notable limitations of this study is that we defined the specificity of the normative referent group in order to increase relevance to that group. It may be that students did not care or identify with a more specific normative referent group as we defined it. Future research should evaluate if PNF using self-defined normative referents is more efficacious than PNF using researcher-defined normative referents. For example, it would be interesting to also ask students to generate a list of groups with which they most strongly identify. It would also be feasible to allow students to select from a set of possible reference groups to whom their drinking might be compared. An additional limitation is that the present study was limited to Caucasians and Asians. It is unknown if findings would generalize to other racial/ethnic groups. Finally, the present study only evaluated specificity of the normative referent group relative to descriptive drinking norms. Future research is necessary to evaluate if more specific normative referent groups are more effective than less specific normative referent groups when presenting feedback based on injunctive drinking norms.

Conclusions

The present research extends previous implementation of social norms-based interventions for drinking in several ways. This is the first study to evaluate PNF based on specifying the normative referent in regards to race, gender, and Greek status, and to test a PNF intervention with a large sample of Asian ethnic minority students engaged in heavy episodic drinking. Asian students, as noted previously, are a growing risk group for heavy drinking and alcohol use disorders (Grant et al. 2004; Hahm et al., 2004; Office of Applied Studies, 2008; Wecshler et al.. 2002), and are often under-represented in alcohol research trials. Further, the study directly tests the extent to which increasing specificity of the reference group across multiple dimensions of demographic similarity improves (or fails to improve) efficacy of PNF, and tests the magnitude of the normative discrepancy as a potential mechanism explaining the advantage we found for typical student PNF in this context. This has both theoretical and practical significance, as it addresses a critical tension in the normative feedback literature between ostensibly enhancing relevance of the feedback through a focus on highly proximal/similar reference group norms, versus emphasizing the largest normative discrepancy which is generally represented by the typical student norm. Further, while typical student norms are often readily available through annual or routine campus AOD surveys, more specific normative information may be less readily available and entail considerable expense to collect. Thus, the benefit of using typical student normative feedback demonstrated in the current study has important implications for implementation of PNF interventions on college campuses. Additionally, this is the first study to evaluate a direct comparison between PNF and Web-BASICS. Inclusion of two meaningful comparison groups, the Web-BASICS condition and the non-alcohol feedback control condition, increases our understanding of the extent to which typical student PNF is an efficacious and parsimonious approach to reducing alcohol use among ethnic majority and Asian minority students, as well as both males and females and those in Greek organizations. This research extends a growing literature emphasizing the importance of normative comparisons in constructing brief single and multi-component interventions aimed to reduce drinking. The research further contributes to a small body of studies challenging the conventional wisdom that more comprehensive interventions are superior to minimal interventions in producing drinking reductions. We expect the current study will stimulate additional research in these areas. Based on these and previous findings, we would encourage the use of the typical normative referent group when constructing PNF for students identified as heavier drinkers and web-based delivery of feedback.

Figure 1.

Participant flow through the study.

Acknowledgments

Data collection and manuscript preparation were supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant R01AA012547-06A2.

References

- Atkins DC, Gallop RJ. Rethinking how family researchers model infrequent outcomes: A tutorial on count regression and zero-inflated models. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21(4):726–735. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS. Etiology and secondary prevention of alcohol problems with young adults. In: Baer JS, Marlatt GA, McMahon RJ, editors. Addictive behaviors across the life span: Prevention, treatment, and policy issues. Newbury Park: Sage; 1993. pp. 111–137. [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Stacy A, Larimer M. Biases in the perception of drinking norms among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1991;52(6):580–586. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz AD. The social norms approach: Theory, research, and annotated bibliography. 2004 [Electronic Version] from http://www.alanberkowitz.com/articles/social_norms.pdf.

- Bewick BM, West R, Gill J, O’May F, Mulhern B, Barkham M, Hill AJ. Providing web-based feedback and social norms information to reduce student alcohol intake: A multisite investigation. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2010;12(5):e59. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: A meta-analytic integration. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64(3):331–341. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter CA, Kahnweiler WM. The efficacy of the social norms approach to substance abuse prevention applied to fraternity men. Journal of American College Health. 2000;49(2):66–71. doi: 10.1080/07448480009596286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53(2):189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins SE, Carey KB, Sliwinski MJ. Mailed personalized normative feedback as a brief intervention for at-risk college drinkers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63(5):559–567. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronce JM, Larimer ME. Individual-focused approaches to the prevention of college student drinking. Alcohol Research and Health. 2011;34(2):210–221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham JA, Humphreys K, Koski-Jannes A. Providing personalized assessment feedback for problem drinking on the internet: A pilot project. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61(6):794–798. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA. Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS): A harm reduction approach. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Festinger L. A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations. 1954;7:117–140. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Pickering RP. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. 2004;74(3):223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahm HC, Lahiff M, Guterman NB. Asian American adolescents’ acculturation, binge drinking, and alcohol- and tobacco-using peers. Journal of Community Psychology. 2004;32(3):295–308. [Google Scholar]

- Hedden SL, Woolson RF, Malcolm RJ. Randomization in substance abuse clinical trials. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 2006;1:6. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbe J. Negative binomial regression. New York, NY: Cambridge; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Zha W, Weitzman ER. Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24, 1998–2005. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70(Supplement 16):12–20. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummer JF, LaBrie JW, Pedersen ER. First impressions on the scene: The influence of the immediate reference group on incoming first-year students’ alcohol behavior and attitudes. Journal of College Student Development. 2012;53(1):149–162. [Google Scholar]

- Imai K, Keele L, Tingley D. A general approach to causal mediation analysis. Psychological Methods. 2010;15:309–334. doi: 10.1037/a0020761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA, Fromme K, Coppel DB, Williams E. Secondary prevention with college drinkers: Evaluation of an alcohol skills training program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1990;58(6):805–810. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.6.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korcuska JS, Thombs DL. Gender role conflict and sex-specific drinking norms: Relationships to alcohol use in undergraduate women and men. Journal of College Student Development. 2003;44(2):204–216. [Google Scholar]

- Kulesza M, Apperson M, Larimer ME, Copeland AL. Brief alcohol intervention for college drinkers: How brief is? Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35(7):730–733. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kypri K, Langley J, Stephenson S. Episode-centered analysis of drinking to intoxication in university students. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2005;40(5):447–452. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Atkins DC, Neighbors C, Mirza T, Larimer ME. Ethnicity specific norms and alcohol consumption among Hispanic/Latino/a and Caucasian students. Additive Behaviors. 2012;37(4):573–576. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Neighbors C, Pedersen ER. Live interactive group-specific normative feedback reduces misperceptions and drinking in college students: A randomized cluster trial. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22(1):141–148. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.1.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Lac A, Kenney SR, Mirza T. Protective behavioral strategies mediate the effect of drinking motives on alcohol use among heavy drinking college students: Gender and race differences. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(4):354–361. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Cronce JM. Identification, prevention, and treatment revisited: Individual-focused college drinking prevention strategies 1999–2006. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(11):2439–2468. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer M, Kaysen D, Lee C, Kilmer J, Lewis M, Dillworth T, Neighbors C. Evaluating level of specificity of normative referents in relation to personal drinking behavior. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, Supplement. 2009;16:115–121. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Neighbors C, LaBrie JW, Atkins DC, Lewis MA, Lee CM, Walter T. Descriptive drinking norms: For whom does reference group matter? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72(5):833–843. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Turner AP, Anderson BK, Fader JS, Kilmer JR, Palmer RS, Cronce JM. Evaluating a brief alcohol intervention with fraternities. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62(3):370–380. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Turner AP, Mallett KA, Geisner IM. Predicting drinking behavior and alcohol-related problems among fraternity and sorority members: Examining the role of descriptive and injunctive norms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18(3):203–212. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.3.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latane B. The psychology of social impact. American Psychologist. 1981;36(4):343–356. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C. Gender-specific misperceptions of college student drinking norms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18(4):334–339. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C. Social norms approaches using descriptive drinking norms education: A review of the research on personalized normative feedback. Journal of American College Health. 2006a;54(4):213–218. doi: 10.3200/JACH.54.4.213-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C. Who is the typical college student? Implications for personalized normative feedback interventions. Addictive Behaviors. 2006b;31(11):2120–2126. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C. Optimizing personalized normative feedback: The use of gender-specific referents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68(2):228–237. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C, Oster-Aaland L, Kirkeby BS, Larimer ME. Indicated prevention for incoming freshmen: Personalized normative feedback and high-risk drinking. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(11):2495–2508. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang K, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Benson TA, Vuchinich RE, Deskins MM, Eakin D, Flood AM, Torrealday O. A comparison of personalized feedback for college student drinkers delivered with and without a motivational interview. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65(2):200–203. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Lewis MA, Lee CM, Desai S, Larimer ME. Group identification as a moderator of the relationship between social norms and alcohol consumption. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:522–528. doi: 10.1037/a0019944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Larimer ME, Lewis MA. Targeting misperceptions of descriptive drinking norms: Efficacy of a computer-delivered personalized normative feedback intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(3):434–447. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lee CM, Lewis MA, Fossos N, Larimer ME. Are social norms the best predictor of outcomes among heavy-drinking college students? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68(4):556–565. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lewis MA, Atkins DC, Jensen MM, Walter T, Fossos N, Larimer ME. Efficacy of web-based personalized normative feedback: A two-year randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:898–911. doi: 10.1037/a0020766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Applied Studies. Results from the 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National findings. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2008. (DHHS Publication No. SMA 08-4343, NSDUH Series H-34) [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW. Social norms and the prevention of alcohol misuse in collegiate contexts. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63(Supplement 14):164–172. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW, Haines MP, Rice R. Misperceiving the college drinking norm and related problems: A nationwide study of exposure to prevention information, perceived norms and student alcohol misuse. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66(4):470–478. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing [Software] Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2010. http://www.R-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- Reed MB, Lange JE, Ketchie JM, Clapp JD. The relationship between social identity, normative information, and college student drinking. Social Influence. 2007;2:269–294. [Google Scholar]

- Rice C. Misperception of college drinking norms. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 2007;14(4):17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Riper H, Kramer J, Conijn B, Smit F, Schippers G, Cuijpers P. Translating effective web-based self-help for problem drinking into the real world. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2009;33(8):1401–1408. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stappenbeck CA, Quinn PD, Wetherill RR, Fromme K. Perceived norms for drinking in the transition from high school to college and beyond. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;71:895–903. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suls J, Green P. Pluralistic ignorance and college student perceptions of gender-specific alcohol norms. Health Psychology. 2003;22(5):479–486. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.5.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST. In praise of feedback: An effective intervention for college students who are heavy drinkers. Journal of American College Health. 2000;48(5):235–238. doi: 10.1080/07448480009599310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters S, Neighbors C. Feedback interventions for college alcohol misuse: What, why and for whom? Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30(6):1168–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST, Vader AM, Harris TR. A controlled trial of web-based feedback for heavy drinking college students. Prevention Science. 2007;8:83–88. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Dowdall GW, Maenner G, Gledhill-Hoyt J, Lee H. Changes inbinge drinking and related problems among American college students between 1993 and1997. Results of the Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study. Journal of American college health. 1998;47:57–68. doi: 10.1080/07448489809595621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Seibring M, Nelson TF, Lee H. Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts. Journal of American College Health. 2002;50(5):203. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Nelson TF. What we have learned from the Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study: Focusing attention on college student alcohol consumption and the environmental conditions that promote it. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69(4):481–490. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1989;50(1):30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wutzke SE, Conigrave KM, Saunders JB, Hall WD. The long-term effectiveness of brief interventions for unsafe alcohol consumption: A 10-year follow-up. Addiction. 2002;97(6):665–675. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zisserson R, Palfai T, Saitz R. ‘No-contact’ interventions for unhealthy college drinking: Efficacy of alternatives to person-delivered intervention approaches. Substance Abuse. 2007;28(4):119–131. doi: 10.1300/J465v28n04_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]