Abstract

We have developed a class of replicable unnatural DNA base pairs formed between d5SICS and either dMMO2, dDMO, or dNaM. To explore the use of these pairs to produce site-specifically labeled DNA, we report the synthesis of a variety of derivatives bearing propynyl groups, an analysis of their polymerase-mediated replication, and subsequent site-specific modification of the amplified DNA via Click chemistry. We find that with the d5SICS scaffold, a propynyl ether linker is accommodated better than its aliphatic analog, but not as well as the protected propargyl amine linker explored previously. We also find that with the dMMO2 and dDMO analogs, the dMMO2 position para to the glycosidic linkage is best suited for linker attachment, and that while aliphatic and ether-based linkers are similarly accommodated, the direct attachment of an ethynyl group to the nucleobase core is most well tolerated. To demonstrate the utility of these analogs, a variety of them are used to site-selectively attach a biotin tag to the amplified DNA. Finally, we use d5SICSCO-dNaM to couple one or two proteins to amplified DNA, with the double labeled product visualized by atomic force microscopy. The ability to encode the spatial relationships of arrayed molecules in PCR amplifiable DNA should have important applications, ranging from SELEX with functionalities not naturally present in DNA to the production, and perhaps “evolution” of nanomaterials.

Keywords: nucleic acids, DNA replication, nanomaterial, bioconjugation, unnatural base pair

Introduction

DNA is receiving increasing attention for different in vitro applications ranging from aptamer and DNAzyme evolution [1] to nanomaterial development.[2] The utility of DNA for these applications follows from two unique properties, its template-directed amplification and its predictable structure that with site-specific modification offers unprecedented nanometer-scale spatial control that could be used to array small molecules or proteins in specific patterns or spatial relationships. However, current applications fail to take advantage of both of these properties, because the product of template directed (i.e. PCR) amplification cannot be site-specifically modified, while site-specifically modified synthetic fragments cannot be PCR amplified. One approach toward circumventing this limitation is rooted in efforts to expand the genetic alphabet[3] and thus provide unnatural nucleotides with unique functionality as potential sites for site-specific modification within an oligonucleotide.[3e, 4] For example, Hirao and coworkers have used an unnatural base pair and Click chemistry[5] to site-specifically attach a single small molecule biotin tag or fluorophore to PCR amplified DNA.[4c]

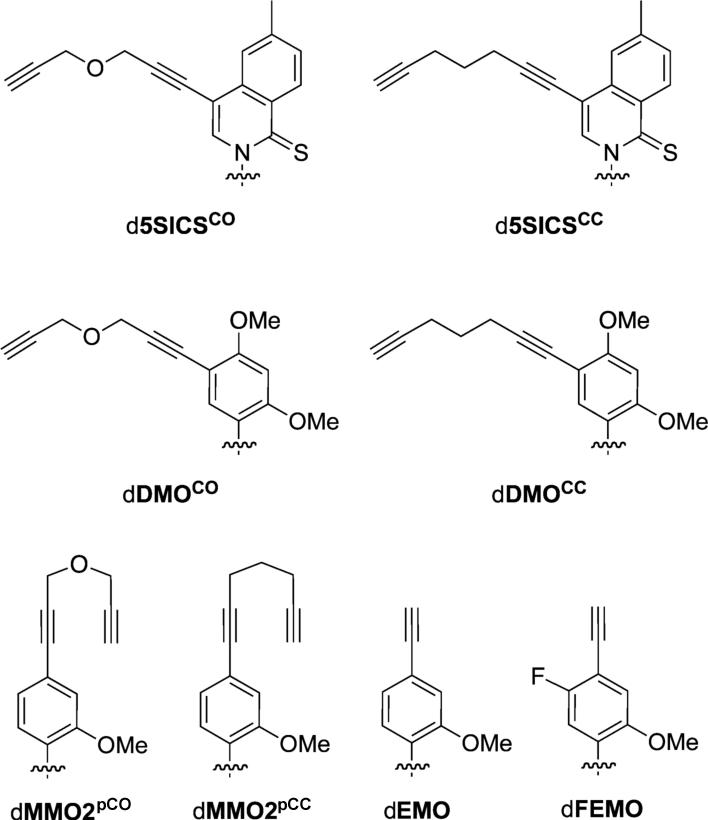

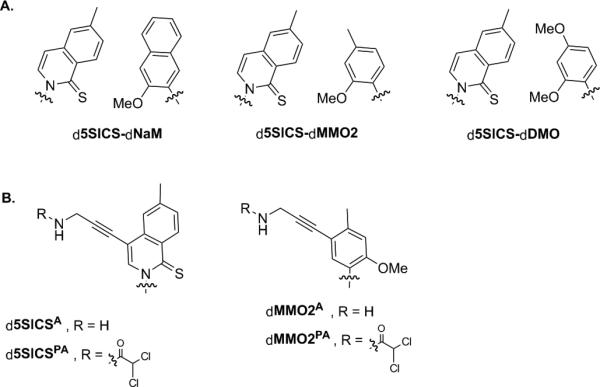

As part of an effort to expand the genetic alphabet, we have developed a class of unnatural base pairs formed between d5SICS and either dMMO2, dDMO, or dNaM (Figure 1A). Pairing of these unnatural nucleotides is mediated only by packing and hydrophobic forces, but nonetheless DNA containing them is efficiently PCR amplified [3b, 6]and transcribed,[7] and linkers may be attached that allow for further, site-specific modification [4a]. While we have shown that d5SICS-dNaM is more efficiently replicated and transcribed than d5SICS-dMMO2, early efforts toward linker-derivatized nucleotides focused on d5SICS and dMMO2, in part because they both may be modified at positions analogous to the C5 position used to attach linkers to the natural pyrimidine triphosphates.[8] A variety of d5SICS and dMMO2 analogs bearing propargyl amine-based linkers were examined and several were identified that allowed for PCR amplification and transcription and shown to allow for the site-specific modification of the resulting oligonucleotide (Figure 1B), however, the dMMO2 analogs were generally replicated less efficiently than the d5SICS analogs. As part of a continued optimization effort we synthesized dEMO and dFEMO (Figure 2), which both possess an ethynyl group as part of their core structure that might also be used for derivatization via Click chemistry.[5] Interestingly, we found that DNA containing either d5SICS-dEMO or d5SICS-dFEMO is more efficiently PCR amplified than DNA containing d5SICS-dMMO2,[9] suggesting that they might provide routes for the efficient production of site-specifically modified DNA.

Figure 1.

(A) Parental unnatural base pairs and (B) previously reported linker modified analogs. Sugar and phosphate backbone are omitted for clarity.

Figure 2.

Linker modified analogs examined in this study (including previously reported dEMO and dFEMO[9]). Sugar and phosphate backbone are omitted for clarity.

Results and Discussion

To explore the use of an unnatural base pair to site-specifically modify DNA with multiple small molecules and/or proteins, we synthesized six analogs of d5SICSTP, dMMO2TP and dDMOTP (Figure 2 and Supporting Information). Along with dFEMO and dEMO, these analogs provide a variety of aliphatic or ether-based linkers with propynyl groups that might be used to site-specifically label PCR amplified DNA via Click chemistry.

We first determined the efficiency with which the Klenow fragment of E. coli DNA polymerase I (Kf) inserts each derivatized triphosphate opposite its cognate nucleotide in template DNA under steady-state conditions (Table 1). The insertion efficiency of d5SICSCOTP opposite dNaM is better than that of d5SICSCCTP, due to both an elevated kcat and a decreased KM. Insertion of d5SICSCOTP opposite dNaM is also more efficient than insertion of d5SICSATP (kcat/KM = 4.4 × 103 M−1 min−1), although it is slightly less efficient than insertion of d5SICSPATP (kcat/KM = 8.3 × 106 M−1 min−1).[4a] For comparison, Kf inserts dATP opposite dT and d5SICSTP opposite dNaM with second-order rate constants of 7.7 × 108 M−1min−1 and 2.1 × 108 M−1min−1, respectively.[3b] Both dMMO2pCOTP and dMMO2pCCTP are equally well inserted opposite d5SICS in the template and are inserted significantly more efficiently than either dDMOCCTP or dDMOCOTP (Table 1), or even dMMO2PATP or dMMO2ATP (kcat/KM = 7.2 × 105 and 9.7 × 104 M−1min−1, respectively). For comparison, Kf inserts dMMO2TP opposite d5SICS with an efficiency of 4 × 105 M−1min−1.[6a]

Table 1.

Steady state kinetic data for Kf-mediated insertion of modified triphosphates (dYTP) opposite their cognate nucleotide in the template (X).

| 5′-d(TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGA) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3′-d(ATTATGCTGAGTGATATCCCTCTXGCTAGGTTACGGCAGGATCGC) | ||||

| dX | dYTP | kcat (min−1) | KM (μm) | kcat/KM × 105 (m−1 min−1) |

| T | A[a] | 4.1 ± 0.3 | 0.0053 ± 0.0004 | 7700 |

| NaM | 5SICS a | 8.3 ± 1.1 | 0.039 ± 0.004 | 2100 |

| 5SICSCC | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 12.3 ± 1.9 | 0.49 | |

| 5SICSCO | 4.9 ± 1.0 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 23 | |

| 5SICS | MMO2a | 13.7 ± 2.0 | 35.8 ± 0.6 | 3.8 |

| DMOa | 27.0 ± 1.5 | 12.2 ± 1.5 | 22 | |

| DMOCC | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 36.4 ± 8.5 | 0.49 | |

| DMOCO | 0.5 ± 1.1 | 13.0 ± 2.8 | 0.38 | |

| MMO2pCC | 12.1 ± 0.8 | 10.7 ± 1.3 | 11 | |

| MMO2pCO | 11.4 ± 1.4 | 10.1 ± 2.4 | 11 | |

Ref. [3b].

To characterize the effects of the appended linkers on the efficiency and fidelity of replication, we used OneTaq polymerase and 16 PCR cycles to amplify a 149-mer duplex containing a single, centrally located unnatural base pair (Table 2). For reference, under these conditions, DNA containing d5SICS-dNaM is amplified with a fidelity of 99.8%, and DNA containing d5SICS-dEMO and d5SICS-dFEMO are replicated with slightly less fidelity.[9] In agreement with the incorporation kinetics described above, d5SICSCO-dNaM is replicated with higher fidelity than d5SICSCC-dNaM, but still lower than d5SICSPA-dNaM (>99.7%) [4a]. Also in agreement with the insertion kinetics, d5SICS-dMMO2pCO and d5SICS-dMMO2pCC are both amplified better than d5SICS-dDMOCO or d5SICS-dDMOCC, and d5SICS-dDMOCC is actually lost during amplification.

Table 2.

PCR fidelities and amplification efficiencies.[a]

| dXTPs incorporated | Amplification | Fidelity[b] |

|---|---|---|

| 5SICS and NaM | 240 | 99.80 ± 0.02 |

| 5SICS and MMO2[c] | 620 | 97.49 ± 0.01 |

| 5SICSCO and NaM | 106 | 99.43 ± 0.01 |

| 5SICSCC and NaM | 49 | 97.0 ± 0.2 |

| 5SICS and DMOCO | 189 | 91 ± 2 |

| 5SICS and DMOCC | 171 | – [d] |

| 5SICS and MMO2pCO | 323 | 98.5 ± 0.4 |

| 5SICS and MMO2pCC | 248 | 98.7 ± 0.3 |

| EMO and NaMc | 710 | 98.48 ± 0.04 |

| FEMO and NaMc | 750 | 98.6 ± 0.4 |

Calculated as average fidelities per doubling from sequencing in both directions (see Supporting information).

Amplified with a different template as described in Ref. [9].

Unnatural base pair lost during amplification.

Overall, with the d5SICS scaffold, the data demonstrate that the propynyl ether linker is accommodated better than its aliphatic analog, but not as well as the protected propargyl amine linker explored previously.[4a] With the dMMO2 and dDMO scaffolds, the data reveal that dMMO2 is better suited for linker attachment, that the position para to the glycosidic linkage dMMO2 is more tolerant than the meta position, and that while aliphatic and ether-based linkers are similarly accommodated, the direct attachment of a ethynyl group to the nucleobase core is most well tolerated.

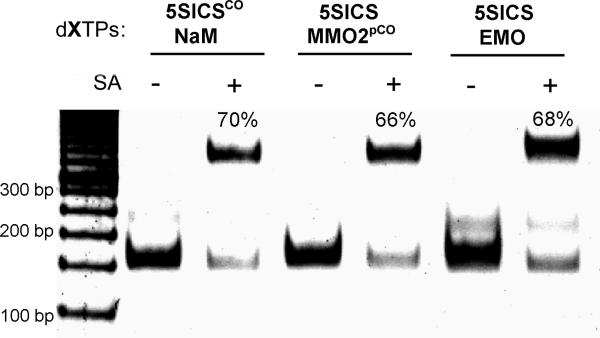

To examine the use of an unnatural base pair and Click chemistry to site-specifically label DNA with a small molecule, we first amplified the 149mer DNA containing a single centrally located d5SICSCO-dNaM, d5SICS-dMMO2pCO, or d5SICS-dEMO. PCR products (30 ng) were reacted with biotin azide (Click Chemistry Tools Bioconjugate Technology Company, AZ) and the Cu2+-stabilizing ligand (BimC4A) [10]3 in a mixed DMSO/H2O system (2:1) containing sodium ascorbate (5 mm) for 2 hr at 37 °C. Under these conditions, streptavidin gel-shift revealed that each duplex was similarly labeled with an efficiency of ~70% (Figure 3). It is particularly noteworthy that the direct attachment of the ethynyl group to the nucleobase scaffold (i.e. dEMO), where steric and electrostatic effects are likely more acute, is as efficiently labeled as with the longer linkers where the alkyne is further removed from the duplex.

Figure 3.

Determination of post-amplification DNA labeling efficiency via streptavidin (SA) gel shift. The biotin incorporation level is 70% for d5SICSCO-dNaM, 66% for d5SICS-dMMO2pCO, and 68% for d5SICS-dEMO. A 50 bp DNA ladder is included in the leftmost lane of the gel. The faster migrating band corresponds to dsDNA, while the slower migrating band corresponds to the 1:1 complex between dsDNA and streptavidin.

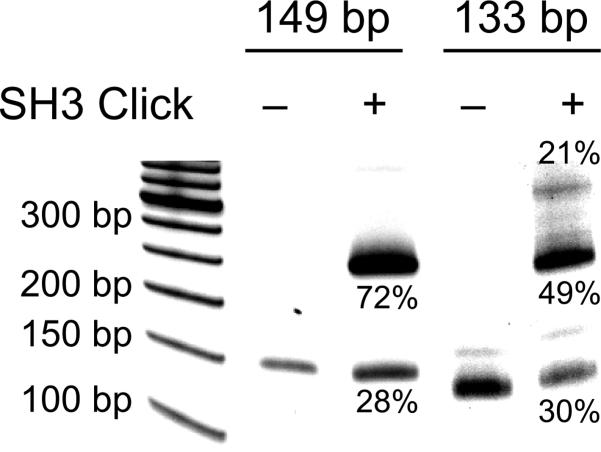

One potentially important property of DNA that has received much recent attention is its ability to act as a scaffold for the display of proteins with nanometer length-scale control.[11] However, previous studies have focused only on attaching a single protein to small synthetic DNA, and it thus remained unclear if steric and/or electrostatic interactions would preclude attachment to larger DNA or the attachment of multiple proteins, as required for arraying applications. To begin to explore the use of d5SICSCO-dNaM to couple one or more proteins to a large, PCR amplified fragment of DNA, we focused on the N-terminal Src homology 3 domain from the human CrkII adaptor protein (nSH3). In general, SH3 domains bind proline-rich ligands and are commonly assembled in tandem to mediate protein assembly via avidity effects that then control localization and/or activity of a wide variety of proteins, especially within signaling pathways.[12] nSH3 was synthesized with an N-terminal azide attached via a PEG4 linker (N3-nSH3) using standard solid phase peptide synthesis methods (Ref. [13] and Supporting Information). A 149 bp DNA duplex containing one centrally located d5SICSCO-dNaM, or a 133 bp duplex containing two d5SICSCO-dNaM pairs (at positions 51 and 97), were generated by PCR (Supporting Information). The amplified DNA (30 ng) was reacted with N3-nSH3 (2 mm), CuSO4 (0.2 mm), sodium ascorbate (5 mm), (BimC4A)3 (0.4 mm ) in 1× phosphate buffer (50 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl) supplemented with 20% DMSO. After 90 min at 37 °C, the DNA was purified (Clean & Concentrator-5, Zymo Research, Irvine, CA), subjected to non-denaturing PAGE, and visualized with Sybr Gold (Invitrogen) (Figure 4). Under these conditions, >70% of the DNA with a single unnatural base pair showed a significant shift, migrating as a slower band, suggesting that it had been covalently modified with an nSH3 domain. As conformation, products were also digested with trypsin before loading on the gel, which resulted in abatement of the shift (Figure S14). When DNA containing two d5SICSCO-dNaM pairs was reacted with N3-nSH3 under identical conditions, three bands were apparent (Figure 4), one corresponding to unmodified DNA (30%), one showing the same gel shift as the sample with a single d5SICSCO-dNaM (49%), and one with an even greater shift (21%). Trypsin digestion resulted in the disappearance of both shifted bands (Figure S14). Thus the two shifted bands are assigned as singly- and doubly-nSH3 modified DNA. The yields suggest that the second labeling is slightly less efficient than the first, likely due to steric and/or electrostatic effects. While this could likely be optimized, it is unlikely to be a major limitation as the doubly labeled product may be easily purified.

Figure 4.

PAGE analysis showing the modification of DNA containing a single d5SICSCO-dNaM pair (149 bp) or two d5SICSCO-dNaM pairs (133 bp) with N3-nSH3. A 50 bp DNA ladder is included in the leftmost lane of the gel. Percentage of total DNA associated with each band is indicated. See text for details.

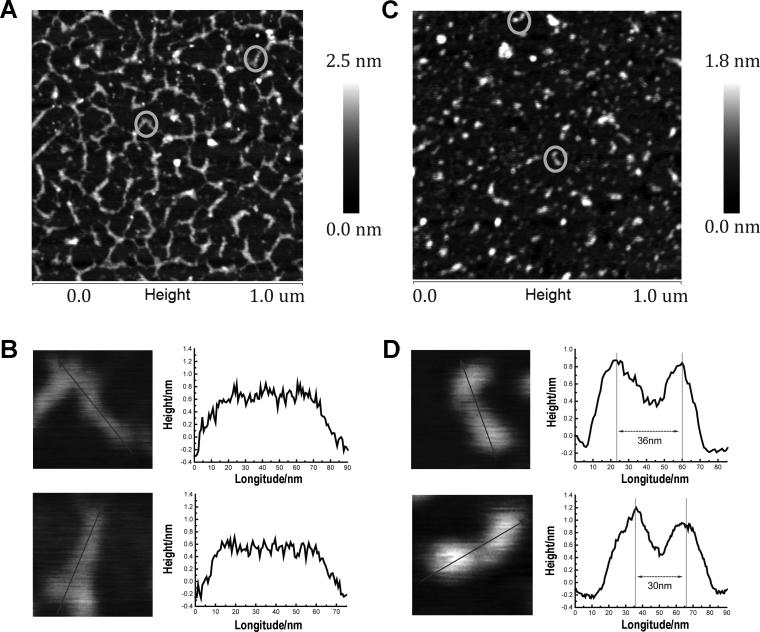

To visualize the arrayed proteins, we employed atomic force microscopy (AFM). The double labeled product was first gel purified and then quantified by fluorescent dye binding. To a solution of 0.1 ng/μL of this DNA, or to a control sample of 1 ng/μL of unmodified DNA, NiCl2 was added (10 mm final concentration) and 10 μL was transferred onto freshly cleaved mica, incubated for 10 min, washed with 2 mL of 5 mm NiCl2 solution, and dried under a stream of compressed air.[14] AFM topographic images of DNA in the unlabeled sample (Figure 5A,B) clearly shows DNA spreading on the mica substrate, and the commonly observed end-to-end contacts.[15] The average duplex length is 55 nm based on the full-width-half-maximum of the cross section profiles, which is in good agreement with the expected length of 44 nm, and the average height is 0.51 nm, consistent with previous studies of duplex DNA.[16] Note that the apparent length and width of each DNA is convoluted by the imaging AFM tip radius of ~15 nm. Significantly, the nSH3 domains in the labeled sample were readily apparent and appeared as spherical objects with an average height of ~1 nm (Figure 5C,D). Importantly, a significant number of the nSH3 domains appear as pairs separated by ~30 nm by a DNA linker of ~0.5 nm height. Given the expected radius of nSH3, the distance between unnatural base pair sites of attachment, and the structure of the linkers, these observations confirm that the DNA is labeled with two nSH3 domains.

Figure 5.

AFM images of unmodified DNA (A and B) and of double-nSH3 labeled DNA (C and D; 10-fold lower concentration). The circled objects in panels A and C are magnified in panels B and D, respectively, and the corresponding height profiles are included.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have identified unnatural base pairs, including d5SICSCO-dNaM and d5SICS-dMMO2pCO/dEMO/dFEMO, that are efficiently replicated and which provide sites for further, site-specific modification via Click chemistry. Indeed, using d5SICSCO-dNaM we have demonstrated the attachment of a small molecule biotin tag, and for the first time a protein to a large, PCR amplified fragment, as well as the arraying of two proteins on the same duplex. Moreover, the orthogonal reactivity of the two linkers of d5SICSCO-dMMO2PA/dMMO2A or d5SICSPA-dMMO2pCO should allow for the arraying of different moieties on the same duplex. The ability to encode the spatial relationships of arrayed molecules in PCR amplifiable DNA should have important applications, ranging from SELEX with functionalities not naturally present in DNA to the production, and perhaps “evolution” of nanomaterials. Efforts toward these goals are currently in progress.

Experimental Section

The stereochemistry of all nucleotides was confirmed via NOE experiments. Kinetics were performed and kcat and KM were determined as described previously (see Supporting Information for details).[3b] PCR amplification efficiency was determined by normalizing the amount of product produced after 16 PCR cycles and fidelity was determined from the retention level of the unnatural base pair, with retention quantified by amplicon sequencing (Figure S15). AFM images were acquired in ambient air on a Veeco Nanoscope IV multi-mode AFM in tapping mode using silicon probes with force constant of 5 N/m and resonant frequency ~ 150 kHz (Ted Pella, Inc.).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Support was provided by the National Institutes of Health (GM60005 to F.E.R.). We thank Prof. M. G. Finn for supplying the (BimC4A)3 ligand.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.chemeurj.org/ or from the author.

References

- 1.a Hollenstein M, Hipolito CJ, Lam CH, Perrin DM. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1638–1649. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Keefe AD, Cload ST. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2008;12:448–456. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a Seeman NC. Ann. Rev. Biochem. 2010;79:65–87. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060308-102244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Wang H, Yang R, Yang L, Tan W. ACS Nano. 2009;3:2451–2460. doi: 10.1021/nn9006303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Chen T, Shukoor MI, Chen Y, Yuan Q, Zhu Z, Zhao Z, Gulbakan B, Tan W. Nanoscale. 2011;3:546–556. doi: 10.1039/c0nr00646g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a Malyshev DA, Dhami K, Quach HT, Lavergne T, Ordoukhanian P, Torkamani A, Romesberg FE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:12005–12010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205176109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lavergne T, Malyshev DA, Romesberg FE. Chem. Eur. J. 2012;18:1231–1239. doi: 10.1002/chem.201102066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Yang Z, Chen F, Alvarado JB, Benner SA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:15105–15112. doi: 10.1021/ja204910n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Kaul C, Muller M, Wagner M, Schneider S, Carell T. Nat. Chem. 2011;3:794–800. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Kimoto M, Kawai R, Mitsui T, Yokoyama S, Hirao I. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:e14. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a Seo YJ, Malyshev DA, Lavergne T, Ordoukhanian P, Romesberg FE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:19878–19888. doi: 10.1021/ja207907d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Yamashige R, Kimoto M, Takezawa Y, Sato A, Mitsui T, Yokoyama S, Hirao I. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:2793–2806. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Ishizuka T, Kimoto M, Sato A, Hirao I. Chem. Comm. 2012;48:10835–10837. doi: 10.1039/c2cc36293g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a Hong V, Presolski SI, Ma C, Finn MG. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2009;48:9879–9883. doi: 10.1002/anie.200905087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Gierlich J, Burley GA, Gramlich PM, Hammond DM, Carell T. Org. Lett. 2006;8:3639–3642. doi: 10.1021/ol0610946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a Leconte AM, Hwang GT, Matsuda S, Capek P, Hari Y, Romesberg FE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:2336–2343. doi: 10.1021/ja078223d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Malyshev DA, Pfaff DA, Ippoliti SI, Hwang GT, Dwyer TJ, Romesberg FE. Chem. Eur. J. 2010;16:12650–12659. doi: 10.1002/chem.201000959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seo YJ, Matsuda S, Romesberg FE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:5046–5047. doi: 10.1021/ja9006996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a Gourlain T, Sidorov A, Mignet N, Thorpe SJ, Lee SE, Grasby JA, Williams DM. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:1898–1905. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.1898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Kuwahara M, Nagashima J, Hasegawa M, Tamura T, Kitagata R, Hanawa K, Hososhima S, Kasamatsu T, Ozaki H, Sawai H. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:5383–5394. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Held HA, Benner SA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:3857–3869. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Lee SE, Sidorov A, Gourlain T, Mignet N, Thorpe SJ, Brazier JA, Dickman MJ, Hornby DP, Grasby JA, Williams DM. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:1565–1573. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.7.1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Sakthivel K, Barbas CF., III Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1998;37:2872–2875. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19981102)37:20<2872::AID-ANIE2872>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lavergne T, Degardin M, Malyshev DA, Quach HT, Dhami K, Ordoukhanian P, Romesberg FE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:5408–5419. doi: 10.1021/ja312148q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodionov VO, Presolski SI, Gardinier S, Lim YH, Finn MG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:12696–12704. doi: 10.1021/ja072678l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.a Nojima T, Konno H, Kodera N, Seio K, Taguchi H, Yoshida M. PLoS One. 2012;7:e52534. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Nakata E, Liew FF, Uwatoko C, Kiyonaka S, Mori Y, Katsuda Y, Endo M, Sugiyama H, Morii T. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2012;51:2421–2424. doi: 10.1002/anie.201108199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Erkelenz M, Kuo CH, Niemeyer CM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:16111–16118. doi: 10.1021/ja204993s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Kukolka F, Niemeyer CM. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2004;2:2203–2206. doi: 10.1039/b406492e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Niemeyer CM. Chem. Eur. J. 2001;7:3189–3195. [Google Scholar]; f Niemeyer CM, Bürger W, Peplies J. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1998;37:2265–2268. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980904)37:16<2265::AID-ANIE2265>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Niemeyer CM, Koehler J, Wuerdemann C. ChemBioChem. 2002;3:242–245. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20020301)3:2/3<242::AID-CBIC242>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a Pawson T, Nash P. Science. 2003;300:445–452. doi: 10.1126/science.1083653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Nguyen JT, Turck CW, Cohen FE, Zuckermann RN, Lim WA. Science. 1998;282:2088–2092. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cremeens ME, Zimmermann J, Yu W, Dawson PE, Romesberg FE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:5726–5727. doi: 10.1021/ja900505e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lyubchenko YL, Shlyakhtenko LS, Ando T. Methods. 2011;54:274–283. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maffeo C, Luan B, Aksimentiev A. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:3812–3821. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schaper A, Pietrasanta LI, Jovin TM. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:6004–6009. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.25.6004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.