Abstract

Here we report that cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) cells and tissues ubiquitously express the immunosuppressive cell-surface protein CD80 (B7-1). CD80 expression in CTCL cells is strictly dependent on the expression of both members of STAT5 family: STAT5a and STAT5b and their joint ability to transcriptionally activate the CD80 gene. In the IL-2-dependent CTCL cells, CD80 expression is induced by the cytokine in the Jak1/3 and STAT5a/b-dependent manner, while in the CTCL cells with the constitutive STAT5 activation, CD80 expression is also STAT5a/b-dependent but independent of Jak activity. While depletion of CD80 expression does not affect the proliferative rate and viability of the CTCL cells, induced expression of the cell-inhibitory receptor of CD80; CD152 (CTLA-4), impairs growth of the cells. Co-culture of CTCL cells with normal T lymphocytes comprised of either both CD4+ and CD8+ populations, or the CD4+ subset alone, transfected with CD152 mRNA, inhibits proliferation of the normal T-cells in the CD152- and CD80-dependent manner. These data identify a new mechanism of immune evasion in CTCL and suggest that the CD80-CD152 axis may become a therapeutic target in this type of lymphoma.

Abbreviations used in this paper: Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, CD80 (B7-1), STAT5a, STAT5b, CD152 (CTLA-4)

Introduction

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (CTCL) are the most common type of T-cell lymphomas (TCL) (1–3), the clinically and biologically diverse group of malignant lymphoproliferative disorders. CTCL tend to have a progressive course with the early, typically indolent lesions presenting as limited and superficial skin patches or plaques, while the more advanced and clinically aggressive lesions forming intradermal tumors. The CTCL patients frequently display evidence of immunosuppression, in particular at the later stages of the lymphoma (2, 3).

CD80 (B7-1) is a member of the structurally-related family of cell-surface proteins involved in regulation of immune responses (4–6). CD80 expression has been identified not only on activated dendritic cells, B lymphocytes and other types of antigen-presenting cells (4, 5) but also on activated T lymphocytes as well as diverse group of lymphoid and non-lymphoid malignancies (6). There are two functionally distinct types of receptors for CD80 on normal immune T lymphocytes. The first is CD28, a co-stimulatory receptor capable of generating cell-activating signals, together with the T-cell receptor (TCR)-CD3 complex, expressed predominantly on naive and early activated T cells (4, 5). In contrast, the other CD80 receptor, CD152 (CTLA-4) expressed by the subset of late- and post-activated T lymphocytes delivers growth inhibitory co-signal (4, 5).

Here we report that CTCL cells ubiquitously express the CD80 ligand and that its expression is induced by STAT5a and STAT5b, acting together as transcriptional activators of the CD80 gene. The CD80 protein expressed by CTCL cells is functionally active and capable of inhibiting growth of T lymphocytes expressing CD152. These studies suggest that CD80 expression on CTCL cells plays a role in evasion of the tumor’s escape from the immune surveillance and, consequently, CD80 may be a novel therapeutic target in this type of lymphoma.

Materials and Methods

Cells and Tissue Samples

IL-2-dependent T cell lines Sez-4 and SeAx and IL-2-independent MyLa2059, MyLa3675 were derived from CTCL and PB-1, 2A, and 2B were derived from a patient with a primary skin CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorder (7, 8). NPM-ALK-expressing SUDHL-1, SUP-M2, JB6, L82, Karpas 299, and SR786 cell lines were derived from ALK+ TCL patients (9, 10). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) harvested from de-identified healthy adults were isolated by Ficoll/Paque centrifugation and either used directly or stimulated in vitro for 72 h with a mitogen (PHA; Sigma). In some experiments, purified human CD4+ T cells or total CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were obtained from the Human Immunology Core of the University of Pennsylvania under an IRB approved protocol. CD4+ T cells were activated by adding CD3/28 beads at a cell:bead ratio of 1:3. The cell cultures were performed at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in RPMI medium 1640, supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 10% heat-inactivated FBS (FBS), 1% penicillin/streptomycin mixture and, for the Sez-4 and SeAx cell lines, IL-2 (200 U/mL). CTCL tissues were obtained as excisional biopsies obtained for diagnostic purposes and used in this study under the protocol approved by the institutional IRB (protocol #706169). Diagnosis was established by standard morphological and immunohistochemical criteria.

DNA Oligonucleotide Array

Analysis was performed as described previously (8, 10). In brief, total RNA from SUDHL-1, SUP-M2, Sez-4, SeAx, MyLa2059, and MyLa3675 cells was reverse-transcribed, biotin-labeled, and hybridized to a U133 Plus 2.0 or Human gene 1.0 ST array (Affymetrix). The array hybridization data were normalized using Expression Console (Affymetrix) and further statistically analyzed with Partek GS 6.6 (Partek Inc.), and Gene notating with DAVID bioinformatics resources.

RNA isolation and RT-qPCR

Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Protect Mini kit (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription to obtain cDNA was performed using High Capacity RNA-to-cDNA Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Quantitative (“real-time”) PCR was performed using ABI PRISM 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). TaqMan® Gene Expression Assay was used for CD80 mRNA detection (Hs00175478 with control actin, Hs9999903). All amplifications were performed in duplicate. The fold difference in RNA levels was calculated on the basis of the difference between Ct values obtained for control and individual mRNA (dCt).

Western Blot

These experiments were performed using ECL chemiluminescence and antibodies against p-Jak3, p-Stat3, p-Stat5 (Cell Signaling Technology), Jak3, Stat3, Stat5a, Stat5b, and Actin (Santa Cruz), according to standard protocols (9, 10).

Short interfering RNA assay

A mixture of four siRNAs specific for CD80, Stat3, Stat5a, Stat5b, or control, nontargeting siRNAs (all from Dharmacon) was introduced into cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (9, 11).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA

Nuclear proteins and incubated with biotin-labeled DNA probe 5'-AGCCCTTCCATGAAAAGGC-3' corresponding to the CD80 gene promoter region that contains STAT5 binding sites. The protein-DNA complexes were separated by gel electrophoresis and transferred to membranes as described (9). Protein bands were visualized using HPR system (Pierce). In the “supershift” EMSA, the protein extracts were preincubated for 30 min with antibodies against STAT5a, STAT5b, or IgG (R&D).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays

Lysates isolated from formaldehyde-fixed and sonicated cells were incubated with antibodies against STAT5a, STAT5b, and IgG (R&D). DNA–protein immunocomplexes were precipitated with protein A–agarose beads, treated with RNase A and proteinase K. DNA was extracted with phenol-chloroform, precipitated with ethanol and q-PCR-amplified using primers specific for the CD80 gene promoter (5'-CCAAATCTTCACCCCACCTA-3’ and 5’-CTGAGGAAAAGCGAATGGAA-3').

Flow Cytometry

The cells were incubated with the PE-conjugated anti-CD80 (Biolegend), -CD28, -CD152 or control IgG antibody (BD Biosciences) for 30 min at room temperature. After washing in PBS, flow cytometry (FACSCalibur; BD Biosciences) analysis was performed using the CellQuest Pro software.

Immunohistochemical tissue analysis

The analysis was performed using the Dako’s Envision Flex System (DakoCytomation). The sections were deparaffinized in xylene and alcohol. Before staining, heat-induced antigen retrieval by boiling slides in 10mM citrate buffer pH 6 for 20 min and cooling for 20 min was employed. The sections were then blocked with Dako’s (Carpinteria, CA) Peroxidase blocking system for 10 minutes. Sequential incubations included the following: primary anti-CD80 rabbit monoclonal antibody (Abcam, MA) at 1:200 dilution for 30 min at room temperature. After washing with buffer, slides were incubated with Envision Flex Rabbit Linker for 30 minutes at room temperature. The slides were washed, incubated with Envision Flex/HRP polymer for 30 min at room temperature, washed, exposed to DABplus substrate-chromagen solution for 5 min at room temperature, and counterstained with hematoxylin.

MTT enzymatic conversion assay

The cells were cultured at 37°C in microtiter plates at 2 X 104/well for up to three days, labeled with 10 µl MTT (Promega) at 5 mg/ml for 4 h and solubilized overnight with 10% SDS in 0.01 M HCl. The absorbance was determined at 570 nm a Titertek Multiskan reader.

Cell proliferation (BrdU incorporation) assay

Cell proliferation was evaluated by detection of 5'-bromo-2'-deoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation using the commercially available Cell Proliferation ELISA kit (Cell Signaling) according to the manufacturer's protocol. In brief, the cells were seeded in 96-well plates (Corning) at a concentration of 2 × 104 cells/well in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% FBS and labeled with BrdU for 24. After the culture plate centrifugation (10 min at 300 g), supernatant removal and the plate drying, the cells were fixed and DNA denaturated by adding 200 ml FixDenat reagent. The amount of incorporated BrdU was determined by incubation with a specific antibody conjugated to peroxidase followed by colorimetric conversion of the substrate and OD evaluation using an ELISA plate reader at 405 nm absorbance.

Plasmid construction and RNA synthesis

RT-PCR was used to obtain the complete coding region of the human CD152/CTLA4 cDNA with primers (5’-ATATAAGCTTAACACCGCTCCCATAAAG-3’ and ATAAGGTACCCAATTGATGGGAATAAAATA-3’). Each primer contains a tail that includes a specific restriction enzyme sequence (HindIII in 5’ primer and Kpn1 in the 3’ primer. Then a 672-base-pair human CTLA4 fragment was cloned at HindIII (upstream) and Kpn1 (downstream) sites into pcDNA3 vector (Invitrogen). CTLA4 cDNA integrity was confirmed by sequence analysis. The pcDNA3-CTLA4 plasmid was linearized with Kpn1 and purified with the Qiagen DNA purification kit before serving as templates for in vitro transcription using the mMESSAGE mMACHINE T7 Kit (Ambion). After RNA synthesis was complete, the in vitro transcription reaction was treated with 1 µl of RNase-free DNase (Ambion) at 37°C for 15 min to degrade the DNA templates, and the RNA was then purified by RNeasy kit (Qiagen).

RNA electroporation

CD3/CD28-preactivated CD4+ or total T cells were washed twice with Hank's Buffered Salt Solution (Cellgro Mediatech, Herndon, VA), and resuspended in 100 µl of PBS. The cells were transferred to a 2 mm gap electroporation cuvette (Molecular Bio Products, San Diego, CA). Five µg of CTLA4 RNA was added to a cuvette and electroporated with pulse at 500 V, 700um using an ECM630 Electroporator (BTX Molecular Delivery Systems, Holliston, MA). After electroporation, the cells were allowed to recover at room temperature for 5 min, resuspended in 5 ml of complete growth media. Cells were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 24 h, and examined in the proliferative rate evaluation assay.

Cell proliferative rate evaluation assay

CD3/CD28-preactivated, CFSE-labeled CD4+ or total T lymphocytes were co-cultured for 2 days in duplicate with the irradiated CD80 positive MyLa3675 or 2A cells at the cell ratio of 1:1 and analyzed by FACS for the CFSE labeling pattern of the responder cells. In some experiments the co-cultures were performed in the presence of the anti-CD80 or CD152 blocking antibody.

Results

CTCL cells and tissues express CD80

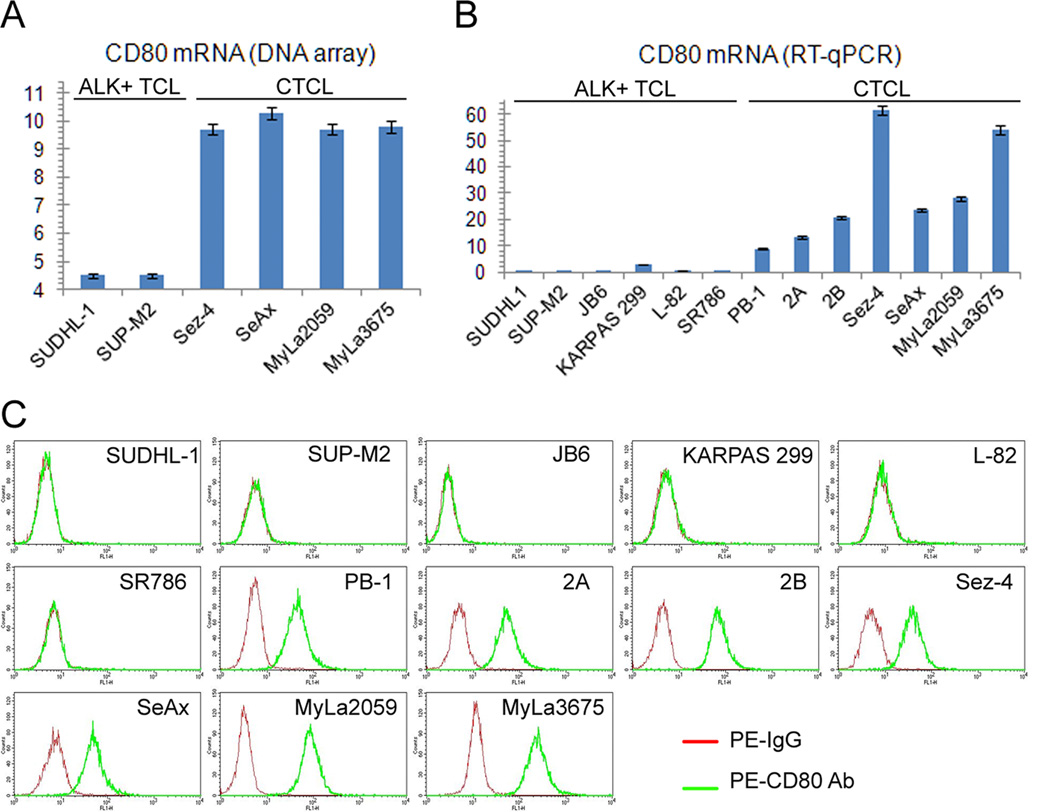

To identify genes protein products of which may play a role in the pathogenesis of CTCL and another type of T-cell lymphoma, characterized by expression of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK+TCL), we performed genome-scale gene expression profiling in four CTCL and two ALK+TCL cell lines. We have noticed that while the ALK+TCL lines failed to express CD80 mRNA, all four CTCL lines strongly expressed the CD80 transcript (Fig. 1A). To verify these results by a more standard and quantitative method using a larger cell population pool, we performed RT-PCR on seven CTCL and six ALK+TCL cell lines (Fig. 1B). Whereas all seven CTCL lines expressed CD80 mRNA to various degrees, the all ALK+TCL lines were essentially negative. This striking dichotomy was also confirmed on the protein level as determined by flow cytometry. As shown in Figure 1C, all seven CTCL cell lines highly expressed CD80 at their cell surface and none of the six ALK+ TCL cell lines expressed the protein.

Figure 1.

CD80 expression in CTCL cell lines. A, The relative expression of CD80 in the depicted ALK+TCL and CTCL cell lines detected by genome-scale DNA oligonucleotide array. B, Expression of CD80 mRNA in the ALK+TCL and CTCL cell lines determined by RT-quantitative (q)PCR. C, Expression of the CD80 protein on cell surface of the ALK+TCL and CTCL cell lines determined by flow cytometry. The depicted data are representative of 3-4 independent experiments.

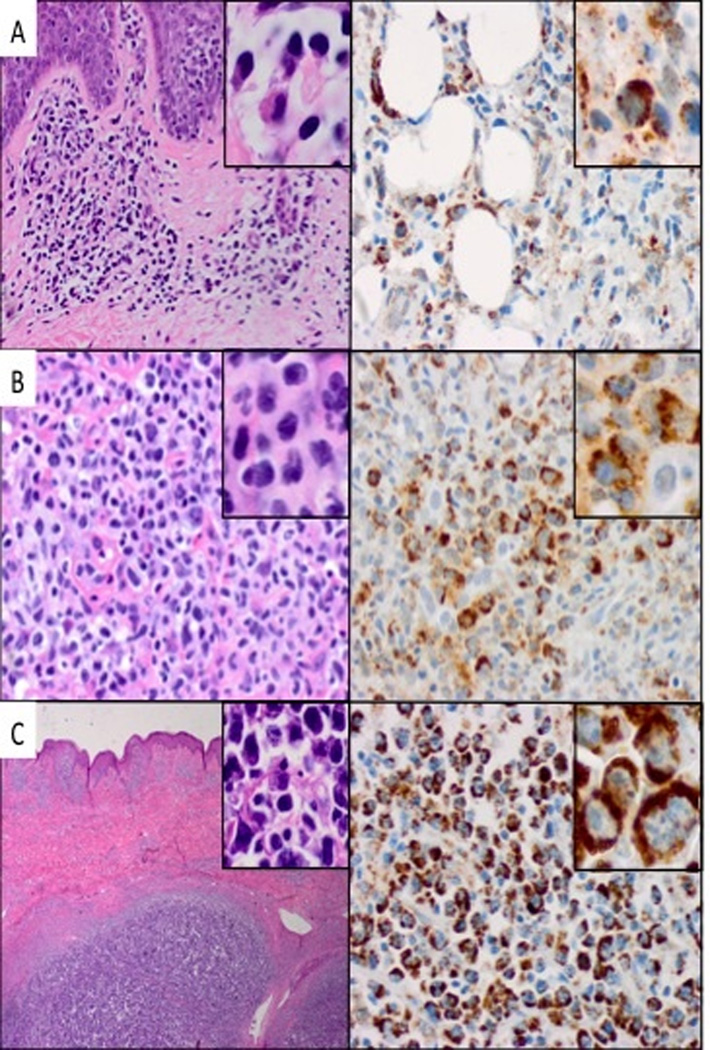

To evaluate CD80 expression in CTCL tissues, we examined by immunohistochemistry formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue samples from twenty-nine cases of CTCL representing various histological stages of the lymphoma. The CD80 expression was present at all stages of CTCL (Fig. 2). Accordingly, we detected CD80 expression in six out of seven cases with the clinically indolent path/plaque stage of CTCL (Fig. 2A). Similarly, ten out of eleven cases of tumor stage (Fig. 2B) and also ten out of eleven cases of large cell transformation (Fig. 2C) displayed strong CD80 expression. The staining was seen predominantly in the transformed cells, with small lymphocytes typically appearing negative, indicating that the CD80 expression occurs in the malignant CTCL cells.

Figure 2.

CD80 expression in CTCL tissues. A, Patch/plaque stage: H&E 20x (inset 100x) and CD80 40x (inset 100x). B, Tumor stage: H&E and CD80, 40x (inset 100x). C, Large cell transformation: H&E 20x (inset 40x) and CD80 40x (inset 100x). The depicted data are representative of the tissue biopsies obtained from 29 CTCL patients.

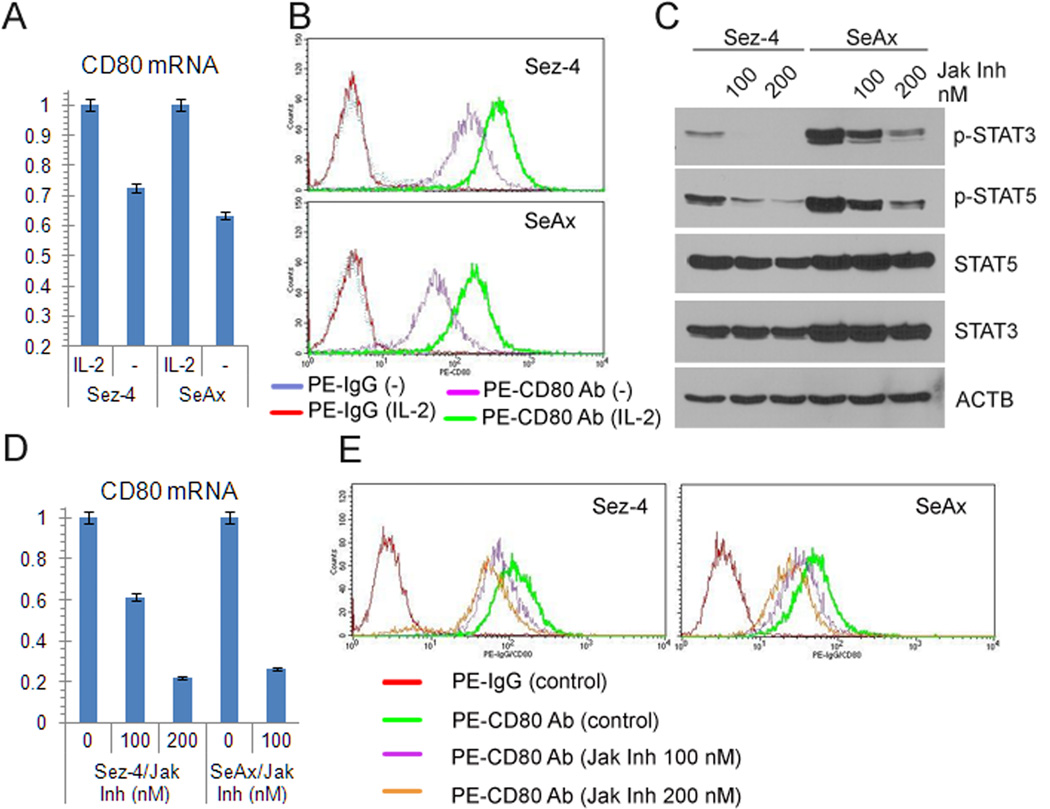

IL-2 induces CD80 expression in the cytokine-dependent CTCL cells

Because two of the CTCL cell lines examined: Sez-4 and SeAx require IL-2 for their growth and phenotype (7, 8, 11) with the cytokine regulating expression of a large set of genes in these cells (8), we examined next if IL-2 plays a role in the ability of the CTCL cells to express CD80. As shown in Figure 3A, CD80 expression is, indeed, IL-2-dependent in these CTCL cells, since withdrawal of the cytokine markedly diminished in them the concentration of CD80 mRNA. We have confirmed the IL-2-dependence of CD80 expression in Sez-4 and SeAx cells by examining also CD80 protein expression (Fig. 3B). Because IL-2-induced signaling is in these CTCL cells strictly dependent on the enzymatic activity of the Jak1/Jak3 kinase complex (7, 8, 11) required to phosphorylate and, consequently, activate the IL-2 receptor complex, we evaluated next the effect of Jak inhibition on CD80 expression. Not surprisingly, a small molecule Jak inhibitor capable to efficiently supress phosphorylation of two Jak1/Jak3 targets STAT3 and STAT5 at the quite low, nM doses (Fig. 3C), inhibited CD80 expression in the dose-dependent manner on both mRNA (Fig. 3D) and protein (Fig. 3E) levels.

Figure 3.

CD80 expression in IL-2-dependent CTCL cells is induced by the cytokine. A, CD80 mRNA expression in the IL-2-dependent CTCL cell lines Sez-4 and SeAx after IL-2 stimulation or starvation (-) detected by RT-qPCR. B, Cell-surface expression of CD80 protein by IL-2-stimulated and deprived Sez-4 and SeAx cells detected by flow cytometry. C, expression of phospho(p)-STAT5, p-STAT3, and control total proteins in the cells treated with Jak inhibitor (Calbiochem) detected by Western blot. D, CD80 mRNA expression in the cells treated with Jak inhibitor detected by RT-qPCR. E, CD80 protein expression in the Jak inhibitor-treated cells detected by flow cytometry. The depicted results are representative of 3-5 independent experiments.

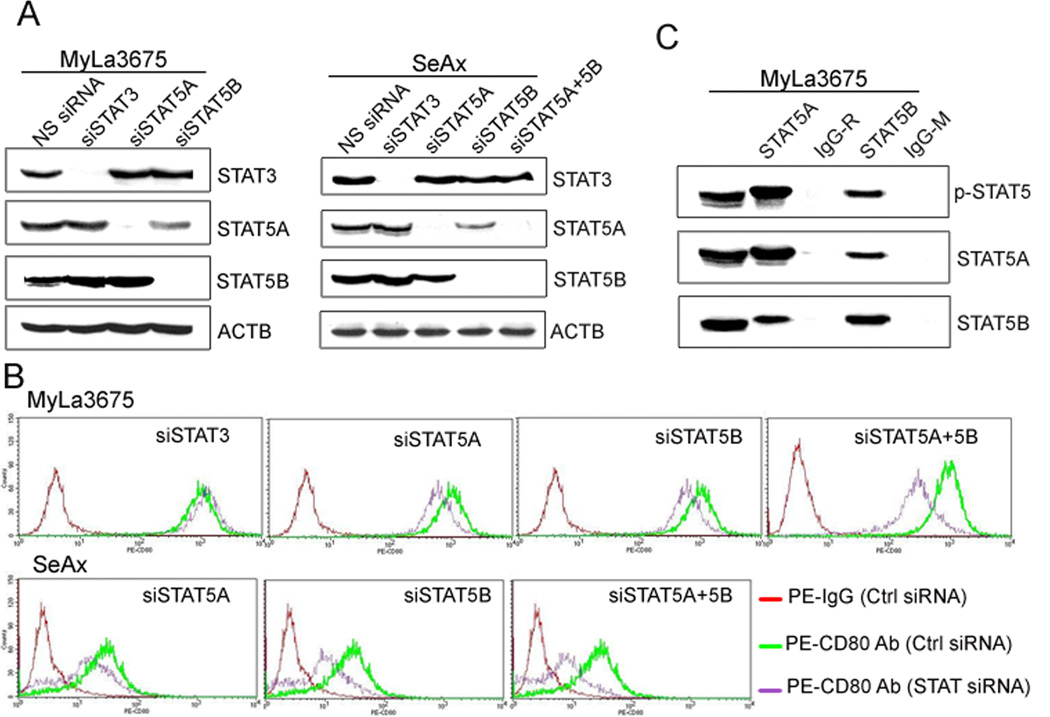

STAT5A and STAT5B induce expression of CD80

Given that STAT5, and more specifically STAT5A and STAT5B; two structurally highly related transcription factors activated by IL-2 in the cytokine-dependent CTCL cells and persistently active in the IL-2-independent CTCL cells (7, 8, 11), we next tested their involvement in regulation of the CD80 expression. SiRNA-mediated depletion of STAT5A and STAT5B, performed alone and in combination (Fig. 4A), markedly decreased expression of CD80 protein in both IL-2-independent (MyLa3675) and IL-2-dependent (SeAx) CTCL cell lines, in particular when both STAT5A and STAT5B were no longer expressed (Fig. 4B). The inhibition was STAT5 specific, since depletion of STAT1 or NF-kB or inhibition of mTORC1 by rapamycin had no effect on CD80 expression (data not shown). Because STAT proteins are capable of forming heterodimers to exert their activity, we examined if STAT5A and STAT5B are associated with each other in the CTCL cells. They, indeed, co-associated as determined in the co-precipitation study using MyLa3675 cells (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

CD80 expression is induced by STAT5A and STAT5B. A, STAT5A- and STAT5B-specific siRNA depletion in MyLa3675 and SeAx cells as determined by Western blotting. B, Effect of the siRNA-mediated STAT5A depletion on CD80 expression detected by flow cytometry. C, STAT5A and STAT5B in vivo co-association detected by co-immunprecipitation assay. The depicted data are representative of at least 3 independent experiments.

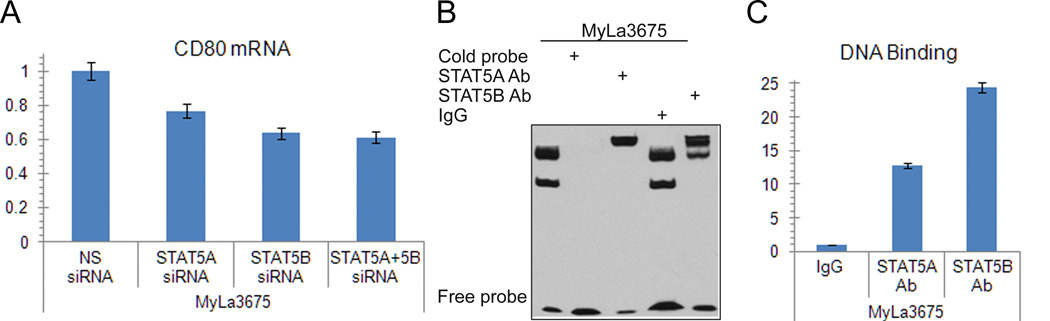

STAT5A and STAT5B transcription activator complex induces expression of CD80 gene

To document that involvement od STAT5 proteins in the CD80 expression induction was through their regulation of the CD80 gene, we performed several different experiments. First, we demonstrated that siRNA-mediated depletion of STAT5A and STAT5B markedly decreased expression of CD80 mRNA (Fig. 5A). Next, our in silico sequence analysis of the CD80 gene promoter identified a potential STAT5 binding site. An electromobility shift assay (EMSA) with a 23-mer DNA oligonucleotide corresponding to this identified site showed binding of the probe to protein extract from MyLa3765 cells (Fig. 5B, first lane). The protein binding was specific as demonstrated by abrogation of binding by addition of an unlabelled (cold) probe (Fig. 5B, second lane). The binding protein complex contained both STAT5A and STAT5B as determined in the EMSA super-shift assay in which pre-incubation of the protein extract with the antibody specific for STAT5A or STAT5B resulted in formation of the “shifted”, slower-migrating protein aggregate (Fig. 5B, third and fifth lanes). To show that STAT5A and STAT5B bind to the CD80 promoter also in vivo, in intact CTCL cells, we performed chromatin precipitation (ChIP) assay using STAT5A and STAT5B antibodies and PCR primers specific for the CD80 promoter. Binding of the STAT5A and STAT5B antibodies to the promoter was 10- and 25-fold higher, respectively, than binding of control IgG as determined by qPCR (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

STAT5A and STAT5B complex activates CD80 gene. A, Effect of STAT5A- and STAT5B-specific siRNA depletion on CD80 mRNA expression detected by RT-qPCR. B, Binding of STAT5A and STAT5B to the CD80 gene promoter in vitro detected by EMSA and super-shift EMSA with STAT5A- and STAT5b-specific antibodies. C, Binding of STAT3 to the CD80 gene promoter in vivo detected by ChIP assay. The depicted results are representative of at least 2 independent experiments.

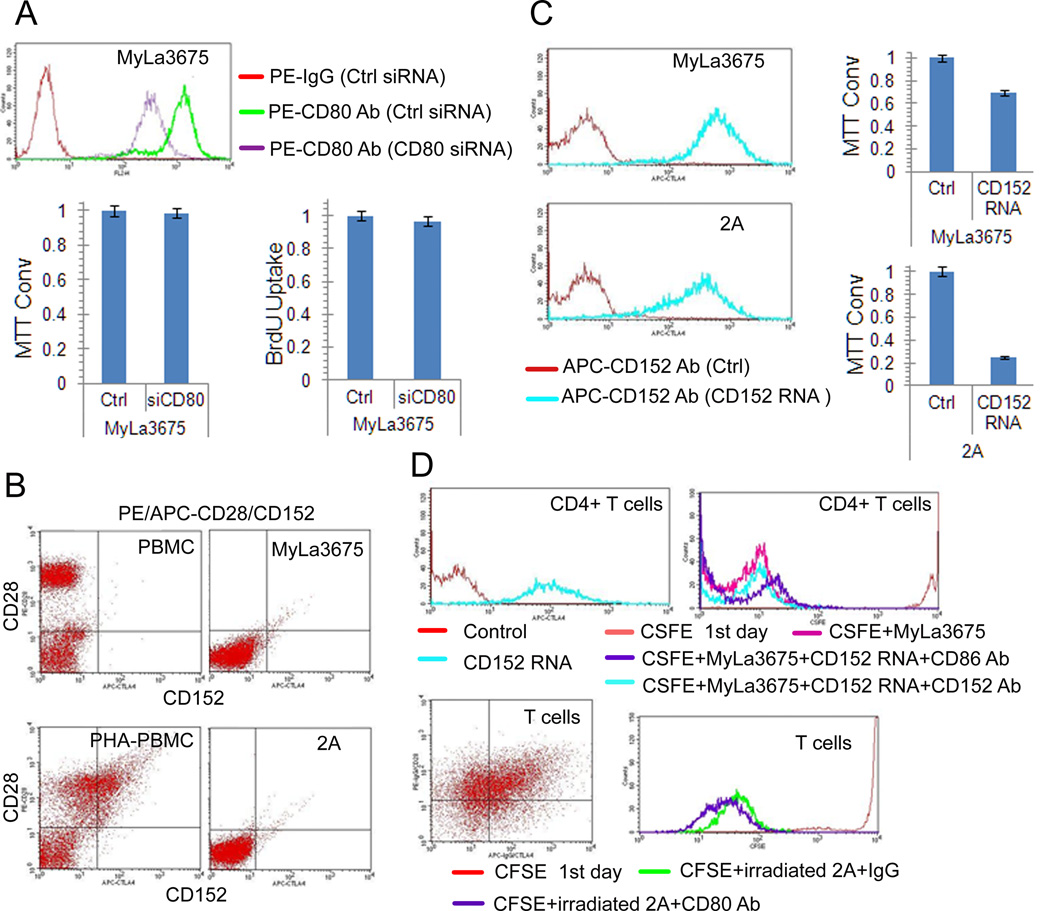

Engagement of CTCL CD80 inhibits growth of CD152-expressing T cells

Given the described both stimulatory and inhibitory nature of CD80, we examined its potential role in the growth of CTCL cells. However, siRNA-mediated depletion of CD80 in MyLa3675 cells (Fig. 6A, left panel) did not affect their growth and viability as determined by the MTT conversion assay (Fig. 6A, middle panel) or proliferation as established in the BrdU uptake assay (Fig. 6A, right panel). Because cell-stimulatory CD28 and cell-inhibitory CD152 (CTLA-4) proteins have been described as receptors for CD80, we analyzed by flow cytometry the available seven CTCL cell lines for their expression using peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC), both resting and mitogen (PHA)-activated PBMC, as controls. While a large subsets of resting PBMC strongly expressed CD28 and PHA-stimulation induced in these cells also CTLA4 expression, all seven CTCL cell lines were negative for CD152 and, with exception of MyLa2059, CD28 (Fig. 6B; representative images). To determine if CD80 expressed by the CTCL is functionally active, we transfected two CTCL cell lines MyLa3675 and 2A with the mRNA encoding its main receptor of CD80, CD152. As shown in Figure 6C, the effective transfection (left panels) resulted in significantly inhibited growth of both cell lines (right panels). To determine if the CD80-expressing cells are able to inhibit proliferation of the normal immune cells, we purified CD4+ T cells or purified total T cells containing both CD4+ and CD8+ cells, pre-activated with immobilized CD3/CD28 antibodies and transfected with CD152 (Fig. 6D, left panels). Exposure to the irradiated CD80-expressing CTCL cells significantly impaired proliferative rate of the CD152-expressing normal T cells, both CD4 and total (Fig. 6D, right panels). Of note, addition of blocking antibodies against CD152 (Fig. 6D, upper right panel) or CD80 (Fig. 6D, lower right panel) completely restored the proliferative capacity of the normal T-cells confirming that the inhibition is mediated by the CD80-CD152 interaction.

Figure 6.

CD80 expressed by CTCL cells suppresses growth of CD152-expressing malignant and normal T lymphocytes. A, Lack of impact of siRNA-mediated CD80 depletion (left panel) on growth of CTCL cells as detected by MTT enzymatic conversion assay (middle panel) and proliferation as determined by BrdU incorporation assay (right panel). B, Lack of expression of the CD28 and CD152 proteins by CTCL cells determined by flow cytometry. Freshly isolated PBMC and PBMC stimulated for 4 days with PHA mitogen (PHA-PBMC) served as controls. C, Effect of CD152 mRNA transfection of the depicted CTCL cells on their CD152 cell-surface protein expression (left panels) and growth rate determined by MTT conversion. D, Effect of co-culture of CD152 mRNA-transfected, CFSE-labeled normal CD4+ T cells (upper panels) and non-separated CD4+ and CD8+ T cell population (lower panels) with irradiated CTCL cells on proliferation of the normal T lymphocytes as determined by FACS for the cell CSFE labeling pattern. Impact of the blocking antibodies against CD152 (upper right panel) or CD80 (lower right panel) on the normal T-lymphocyte proliferation co-cultured with CTCL cells was also determined. The depicted results are representative of 2-3 independent experiments.

Discussion

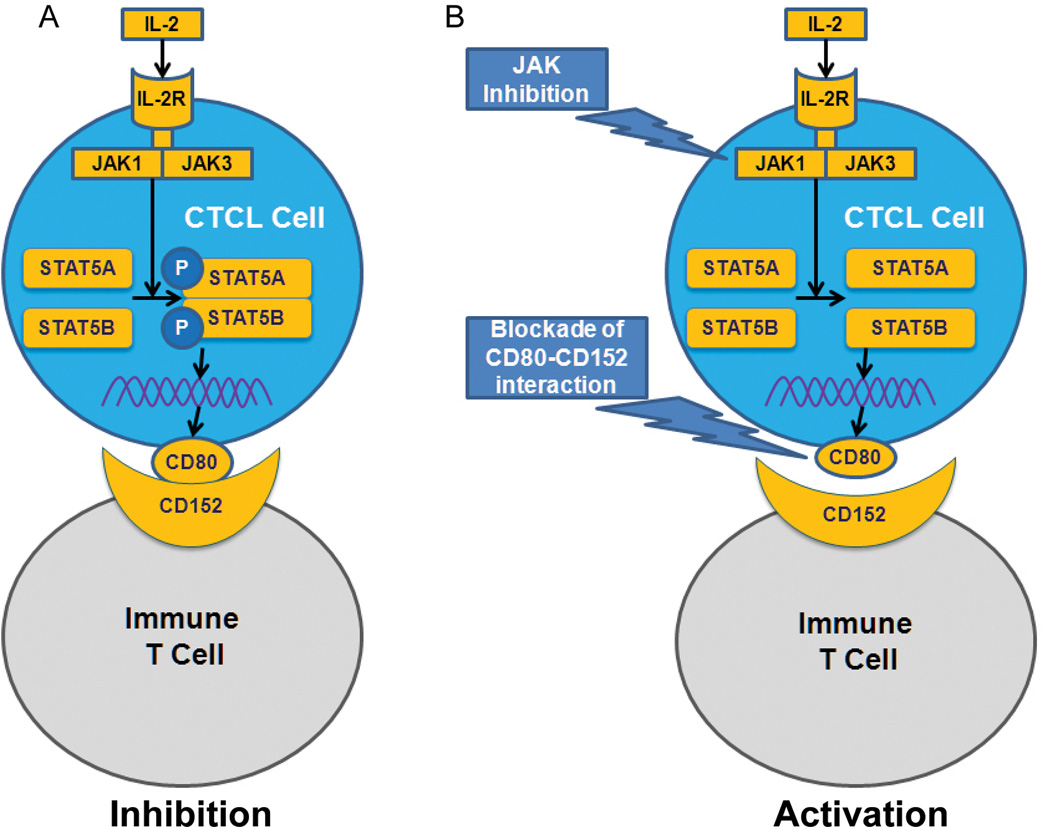

As summarized schematically in Figure 7A, CTCL cells ubiquitously express CD80 and that the expression of CD80 is induced by STAT5a/STAT5b transcription factor complex. In the IL-2-dependent CTCL cells, STAT5a/STAT5b activation and CD80 expression are induced by the cytokine in the Jak-dependent manner, in the IL-2-independent cells the CD80 expression is Jak-independent but dependent on STAT5a/STAT5b transcriptional activity. CD80 expressed by CTCL cells is capable of inhibiting growth of normal immune T lymphocytes, providing they express CD80 receptor CD152, strongly suggesting that CD80 plays an immunosuppressive role in CTCL.

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of CD80 expression induction and inhibition of immune response in CTCL. A, STAT5a and STAT5b activated by Jak1/3-containing IL-2R complex induce in CTCL cells expression of CD80 (B7-1) by triggering transcription of CD80 gene. CD80 inhibits anti-CTCL immune response by engaging CD152 (CTLA4) expressed by normal T lymphocytes. B, Targeting the key nodes of CD80 expression and CD80-CD152 interaction by, respectively, Jak inhibition or antibody-mediated blockade may prove therapeutically beneficial.

Since its discovery over two and half decades ago (12), CD80, the founding member of the B7 cell-surface co-signaling protein family, has been studied extensively in regard to its expression and function in normal immune cells as well as various malignancies (4–6). However, the mechanisms controlling CD80 expression remain essentially unknown. Here we show that the gene coding for CD80 is induced by STAT5a and STAT5b, two closely related transcription factors, known to form active heterodimers. Of note, in the IL-2-dependent CTCL cells, STAT5 activation, and the ensuing CD80 gene induction, occurs in response to IL-2, the key STAT5 activator in general, strongly suggesting that similar mechanism of CD80 gene induction may occur also in the normal immune cells. It may be relevant in this context that CD80 expression by immune cells is not constitutive but requires cell pre-activation suggesting that IL-2, or a similar cytokine, may be involved. Of note, previous studies showed that STAT5 is responsible for induction of FoxP3 in both normal regulatory T cells (13) and CTCL cells (7), with the former study documenting involvement of both STAT5a and STAT5b. Our finding demonstrating its key role in induction on CTCL of CD80 displaying immunosuppressive properties expands the role of IL-2 as the cytokine involved in down-regulation of immune response and, in the case of malignancy, immune evasion.

Although CD80 is frequently described as seemingly functionally redundant with CD86 (B7-2), given that both interact with the same receptors CD28 and CD152, several lines of recent evidence suggest that CD80 and CD86 play functionally diverse roles, at least in some circumstances. While expression of CD86 is abundant on resting antigen-presenting cells, these cells require activation to express CD80 (4–6). Similarly, the co-stimulating receptor CD28 is expressed on naive T lymphocytes, whereas high CD152 expression occurs late after antigenic stimulation and its appearance is associated with the steady loss of CD28 by the effector T cells entering the post-activation, quiescent phase (4). This differential temporal expression of the B7 proteins and their receptors results in the involvement of CD86-CD28 axis in initiation and augmentation of the immune response, while CD80 and CD152 participate in the response later, including its terminal down-regulation. Furthermore, CD86 preferentially binds CD28 and the avidity of CD80 is higher for CD152 within the immunological synapse (14), further functionally differentiating these B7 molecules from each other. Therefore, based on the differential temporal expression and the receptor binding strength dichotomy of CD86 and CD80, the former seems preferentially engaged in generation of the immune response, while the latter in its down-regulation. These observations combined with ubiquitous expression of CD80 by the CTCL cells, supports the notion that the lymphoma cells subvert normal function of the immune system and utilize this cell-surface protein to actively inhibit the anti-tumor response.

Previous studies in a whole spectrum of lymphomas and other malignancies have identified marked diversity in CD80 expression (15–18). While some tumors, such as Burkitt lymphoma and plasma cell myeloma lack CD80 expression, many other including follicular lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, classical and lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma, and mantle cell lymphoma express CD80, albeit at various concentration. The causes as well as the functional consequences of this diversity are currently unclear. It is possible that the malignant T lymphocytes simply recapitulate the phenotype of their normal cell counterparts. However, we find it much more likely that the observed diversity reflects complexity of interactions of the malignant cells with its microenvironment, foremost the tumor-infiltrating normal immune cells and, possibly, tumor-type specific mechanisms of immune evasion.

Our showing that CD80 expressed by CTCL is capable of inhibiting growth of CD152-expressing normal immune cells may have clinical implications (Fig. 7B). Thus, antibody-induced blockade of the CD80 may boost immune response against CTCL cells. Similarly, antibody-mediated inhibition of CD152 may increase the number and effectiveness of the tumor-specific immune T cells. Blocking antibodies targeting either CD80 or CD152 have already been tested in clinical trials in a few lymphoid and non-lymphoid malignancies. While antibody galiximab targeting CD80 showed clinical efficacy in follicular lymphoma (19) and, too much lesser degree, Hodgkin lymphoma (20), the results with blocking CD152 with ipilimumab have been effective in follicular lymphoma (21) and melanoma (22), leading to the FDA approval of ipilimumab for treatment of the latter. Our finding that STAT5a and STAT5b jointly induce CD80 gene expression, due to IL-2 stimulation in some instances, suggests that targeting these STAT5 family members or, where applicable, Jak1/Jak3 complex with small molecule inhibitors, may be an attractive alternative to the antibody-based treatment protocols.

It is also possible that the ultimate effect of the CD80-directed therapy may depend on other aspects of the malignant cell phenotype. CTCL cells display remarkable plasticity in this regard (2). As mentioned, through activation of STAT5a and STAT5b, IL-2 will induce expression of not only CD80 but also FoxP3 (7) the CTCL cells are capable of expressing cytokines from the IL-17 family (23) as well as the strongly immunosuppressive B7-type cell surface protein CD274 (PD-L1) (24), induced by STAT3, in at least some type of malignant T cells (2, 10). These cells also strongly express another B7 type co-stimulatory factor ICOS (25); its function in CTCL cells remains unclear but in T-cell lymphomas expressing ALK, ICOS generates. Therefore, it is likely that simultaneous inhibition of several members of the B7 family and, possibly, other co-signaling molecules for the immunotherapy to be ultimately successful. An in-depth and comprehensive understanding of the immune dysregulation in cancer based on the already existing and future data would be required to rationally design such combined, multi-targeted therapies. The evidence provided in this manuscript regarding the mechanism of CD80 gene induction and identification of CD80 a potential therapeutic target in CTCL may represent another step towards achieving this goal.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the NCI grants R01-CA89194, R01-CA96856 and R01-CA147795, Leukemia and Lymphoma Society grant 6100-09 and Fran and Jim Maguire Fund.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Contribution: Q.Z. designed research, analyzed data, and performed research. H.W. analyzed genomic data and performed research. F.W. and X.L., R. P., and J.C.P. performed research. D.R. and D. M. interpreted immunohistochemical staining. A. P. and S.J. S. designed research. N.O. contributed reagents and designed research. T. M. and J. R. designed research. M.A.W. designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

References

- 1.Hwang ST, Janik JE, Jaffe ES, Wilson WH. Mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. Lancet. 2008;371:945–957. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60420-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abraham RM, Zhang Q, Odum N, Wasik MA. The role of cytokine signaling in the pathogenesis of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Cancer Biol. & Ther. 2011;12:1019–1022. doi: 10.4161/cbt.12.12.18144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Willerslev-Olsen A, Krejsgaard T, Bonefeld LM, Wasik MA, Koralov SB, Geisler C, Kilian M, Iversen L, Woetmann A, Odum N. Bacterial toxins fuel disease progression in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Toxins. 2013;5:1402–1421. doi: 10.3390/toxins5081402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen L, Flies DB. Molecular mechanisms of T cell co-stimulation and co-inhibition. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013;13:227–242. doi: 10.1038/nri3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ceeraz S, Nowak EC, Noelle RJ. B7 family checkpoint regulators in immune regulation and disease. Trends Immunol. 2013;34:556–563. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greaves P, Gribben JG. The role of B7 family molecules in hematologic malignancy. Blood. 2013;121:734–744. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-10-385591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kasprzycka M, Zhang Q, Witkiewicz A, Marzec M, Potoczek M, Liu X, Wang HY, Milone M, Basu S, Mauger J, Choi JK, Abrams JT, Hou JS, Rook AH, Vonderheid E, Woetmann A, Odum N, Wasik MA. Gamma c-signaling cytokines induce a regulatory T cell phenotype in malignant CD4+ T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 2008;181:2506–2512. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.4.2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marzec M, Halasa K, Kasprzycka M, Wysocka M, Liu X, Tobias JW, Baldwin D, Zhang Q, Odum N, Rook AH, Wasik MA. Differential effects of interleukin-2 and interleukin-15 versus interleukin-21 on CD4+ cutaneous T-cell lymphoma cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1083–1091. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Q, Wang HY, Liu X, Wasik MA. STAT5A is epigenetically silenced by the tyrosine kinase NPM1-ALK and acts as a tumor suppressor by reciprocally inhibiting NPM1-ALK expression. Nat. Med. 2007;13:1341–1348. doi: 10.1038/nm1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marzec M, Zhang Q, Goradia A, Raghunath PN, Liu X, Paessler M, Wang HY, Wysocka M, Cheng M, Ruggeri BA, Wasik MA. Oncogenic kinase NPM-ALK induces through STAT3 expression of immunosuppressive protein CD274 (PD-LI, B7-H1) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:20852–20857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810958105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marzec M, Liu X, Kasprzvcka M, Witkiewicz A, Raghunath PN, El- Salem M, Robertson E, Odum N, Wasik MA. IL-2- and IL-15-induced activation of the rapamycin-sensitive mTORC1 pathway in malignant CD4+ T lymphocytes. Blood. 2008;111:2181–2189. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-095182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freedman AS, Freeman G, Horowitz JC, Daley J, Nadler LM. a B-cell-restricted antigen that identifies preactivated B cells. J Immunol. 1987;139:3260–3267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yao Z, Kanno Y, Kerenyi M, Stephens G, Durant L, Watford WT, Laurence A, Robinson GW, Shevach EM, Moriggl R, Hennighausen L, Wu C, O'Shea JJ. Nonredundant roles for Stat5a/b in directly regulating Foxp3. Blood. 2007;109:4368–4375. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-055756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pentcheva-Hoang T, Egen JG, Wojnoonski K, Allison JP. B7-1 and B7-2 selectively recruit CTLA-4 and CD28 to the immunological synapse. Immunity. 2004;21:401–413. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vyth-Dreese FA, Boot H, Dellemijn TA, Majoor DM, Oomen LC, Laman JD, Van Meurs M, De Weger RA, De Jong D. Localizationin situ of costimulatory molecules and cytokines in B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Immunology. 1998;94:580–586. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chaperot L, Plumas J, Jacob MC, Bost F, Molens JP, Sotto JJ. Functional expression of CD80 and CD86 allows immunogenicity of malignant B cells from non- Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Exp. Hematol. 1999;27:479–488. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(98)00059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dakappagari N, Ho SN, Gascoyne RD, Ranuio J, Weng AP, Tangri S. CD80 (B7.1) is expressed on both malignant B cells and nonmalignant stromal cells in non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cytometry B Clin. Cytom. 2012;82:112–119. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.20631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Delabie J, Ceuppens JL, Vandenberghe P, DeBoer M, Coorevits M, De Wolf-Peeters C. The B7/BB1 antigen is expressed by Reed-Sternberg cells of Hodgkin’s disease and contributes to the stimulating capacity of Hodgkin’s disease-derived cell lines. Blood. 1993;82:2845–2852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leonard JP, Friedberg JW, Younes A, Fisher D, Gordon LI, Moore J, Czuczman M, Miller T, Stiff P, Cheson BD, Forero-Torres A, Chieffo N, McKinney B, Finucane D, Molina A. A phase I/II study of galiximab (an anti-CD80 monoclonal antibody) in combination with rituximab for relapsed or refractory, follicular lymphoma. Ann. Oncol. 2007;18:1216–1223. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith SM, Schöder H, Johnson JL, Jung SH, Bartlett NL, Cheson BD. Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology. The anti-CD80 primatized monoclonal antibody, galiximab, is well-tolerated but has limited activity in relapsed Hodgkin lymphoma: Cancer and Leukemia Group B 50602 (Alliance) Leuk. Lymphoma. 2013;54:1405–1410. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2012.744453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ansell SM, Hurvitz SA, Koenig PA, LaPlant BR, Kabat BF, Ferando D. Phase I study of ipilimumab, an anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibody, in patients with relapsed and refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009;15:6446–6453. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, Gonzalez R, Robert C, Schadendorf D, Hassel JC, van den Eertwegh AJ, Lutzky J, Lorigan P, Vaubel JM, Linette GP, Hogg D, Ottensmeier CH, Lebbé C, Peschel C, Quirt I, Clark JI, Wolchok JD, Weber JS, Tian J, Yellin MJ, Nichol GM, Hoos A, Urba WJ. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krejsgaard T, Litvinov IV, Wang YA, Xia L, Willerslev-Olsen A, Koralov SB, Kopp KL, Bonefeld CM, Wasik MA, Geisler C, Woetmann A, Zhou Y, Sasseville D, Odum N. Elucidating the role of interleukin-17F in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2013;122:943–950. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-480889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kantekure K, Yang Y, Raghunath P, Schaffer A, Woetmann A, Zhang Q, Odum N, Wasik MA. Expression patterns of the immunosuppressive proteins PD-1/CD279 and PD-L1/CD274 at different stages of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma/mycosis fungoides. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2012;34:126–128. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e31821c35cb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Q, Wang H, Kantekure K, Paterson JC, Liu X, Schaffer A, Paulos C, Milone MC, Odum N, Turner S, Marafioti T, Wasik MA. Oncogenic tyrosine kinase NPM-ALK induces expression of the growthpromoting receptor ICOS. Blood. 2011;118:3062–3071. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-332916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]