Abstract

Hypodontia is the congenital absence of one or more teeth and may affect permanent teeth. Several options are indicated to treat hypodontia, including the maintenance of primary teeth or space redistribution for restorative treatment with partial adhesive bridges, tooth transplantation, and implants. However, a multidisciplinary approach is the most important requirement for the ideal treatment of hypodontia. This paper describes a multidisciplinary treatment plan for congenitally missing permanent mandibular second premolars involving orthodontics, implantology and prosthodontic specialties.

Keywords: Hypodontia, Dental implants, Dental prosthesis design

INTRODUCTION

The congenital absence of teeth can seriously affect a young person, both physically and emotionally, especially when the missing tooth is located in the anterior region of the mouth. Hypodontia is the congenital absence of teeth and refers to the condition where there is an absence of one or a few teeth21. In addition, hypodontia of permanent teeth is fairly common in contemporary populations11 and is the most common human malformation. It occurs without any other signs or symptoms of developmental disorders7,17,22. Both genetic4,9 and environmental2,10 components are involved in the etiology of hypodontia3, and several genetic and syndromic conditions are currently known to increase the risk of hypodontia19; nonetheless, congenitally missing teeth are commonly found in healthy people17,22.

The prevalence of hypodontia ranges from 1% in African Negroes and Australian aborigines to 30% in Japanese people21, and studies of white subjects have reported higher frequencies of hypodontia among females (a female-to-male ratio of approximately 3:2)11. The third molars are the most frequently missing teeth, but they do not need to be replaced; however, mandibular second premolars (2.8%), maxillary lateral incisors (1.6%), and maxillary second premolars and mandibular incisors (0.23%-0.08%)5 are the most frequently missing teeth that require some type of treatment.

Hypodontia usually requires extensive and complex treatments, ranging from single restorations to surgery and multiple restorations, associated with lifelong maintenance12. Several treatment solutions have been presented in the dental literature1,16,20,23. In broad terms, the necessary treatment depends on the pattern of tooth absence, the amount of residual spacing, the presence of malocclusion and patient attitudes. One of the key factors for the successful treatment of patients with hypodontia is the interdisciplinary intervention, which involves the close work of a committed team (general dental practitioner, pediatric dentist, orthodontist, implantologist and prosthodontist), where each member contributes with a different expertise to achieve an optimal outcome for the patient21. The purpose of this article is to present a case of hypodontia in which the treatment plan consisted of the association of orthodontic, implantology, and prosthetic specialties.

CASE REPORT

A 17-year-old male patient in the final stage of orthodontic treatment presented with the primary second molars in position for space maintenance. Hypodontia had been previously diagnosed by the orthodontic team (Figure 1), and the patient was referred to the Oral Rehabilitation Clinic (FOB/USP) for extraction of those teeth and rehabilitation of the area. Analyses of the occlusal condition revealed the presence of both canine and protrusive guidance achieved by orthodontic therapy and that the deciduous second molars were in infraocclusion (Figure 2). The patient did not present with any systemic or genetic disorder that could be associated with hypodontia, and the oral hygiene status was satisfactory.

Figure 1.

Preorthodontic panoramic radiograph

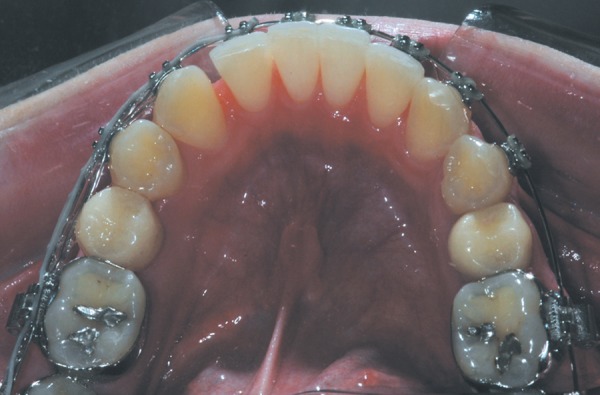

Figure 2.

Initial aspect showing infra-occlusion of the primary mandibular right and left second molars

Several treatment options were considered, including adhesive or conventional fixed bridges and implants, because there were radiographic signs of root resorption in the primary teeth. Considering the consecutive cephalometric analyses, which demonstrated that the patient had reached physical maturity, the bone availability, the absence of medical contraindications, and the patient consent, the treatment comprised the extraction of primary teeth and placement of immediate load implants. However, the mesiodistal dimensions of the primary teeth were larger than that required to restore the anatomy of the mandibular second premolar but insufficient to restore the dimensions of a mandibular first molar. Thus, the only option was to reduce the mesiodistal distance by orthodontic therapy before implant placement. To plan the prosthetic space and at the same time to guide the orthodontic movement, the occlusal surfaces of the primary teeth were marked according to the mesiodistal dimension of a mandibular second premolar (Figure 3), and the distal surfaces were reduced without changing the infraosseous anatomy to acquire space to fabricate the provisional crowns with anatomic characteristics of mandibular second premolars (Figure 4). This step of prosthetic planning was fundamental to the accomplishment of the orthodontic treatment.

Figure 3.

Occlusal view of the mandibular primary teeth showing the delimitation mark for the proximal reduction

Figure 4.

Occlusal view showing the distal space after cementation of the provisional crown

After the planned space closure (Figure 5), the teeth were extracted, and external hex implants with a 4.1 mm rectangular platform were immediately placed (Master Porous Grip, Conexão Sistemas de Implante, São Paulo, SP, Brazil) with immediate load (Figures 6). The Ceraone abutment was selected (Conexão Sistemas de Implante) and placed at a torque of 32 N. The provisional crown was then adapted, cemented with temporary cement (RelyX Temp; 3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA) and maintained in infra-occlusion for 4 months. During this period, the orthodontic appliance was maintained for retention of the orthodontically moved mandibular molars. The implants were considered clinically acceptable after clinical (absence of pain, infection, mobility, or any other signal of pathology into the soft tissues) and radiographic (no signs of periimplant radiolucency) examinations.

Figure 5.

Occlusal view after the planned space closure between the molars and the provisional crowns

Figure 6.

Occlusal view of the provisional crowns after placement of the immediate load implants

An impression of the Ceraone abutment was taken with the emergence profile customization technique with silicone (Optosil® and Optosil Xantopren®; Heraeus Kulzer GmbH & Co. KG, Germany). The metal-ceramic crowns were cemented with glass-ionomer cement (Relay X Luting 2; 3M ESPE). The patient was given maintenance therapy every 6 months during a 2-year period.

The final outcome reflected the care taken, especially during the planning of the prosthetic space to be restored (Figure 7). The 2-year follow-up revealed maintenance of orthodontic treatment, occlusal plane and oral hygiene, esthetics (Figures 8a and 8b), and the stability of the bone level (Figure 9). No mechanical (ceramic fracture, screw loosening, and loss of retention) and/or biological complications (periimplantitis) were recorded.

Figure 7.

Final occlusal aspect after cementation of metal-ceramic crowns of the mandibular right and left second premolars

Figure 8.

Proximal view after 2 years of follow-up

Figure 9.

Panoramic radiograph after 2 years of follow-up

DISCUSSION

The multidisciplinary approach associated with early diagnosis in individuals with hypodontia of permanent teeth is related to treatment success14. However, definitive treatment of the missing teeth is often performed only after eruption of all permanent teeth or completion of orthodontic treatment. The oral patient's hygiene status and socioeconomic conditions as well as the maintenance therapy should also be considered6.

Multidisciplinary treatment is usually initiated upon the diagnosis of hypodontia, often by the pediatric dentist or general practitioner. The main contribution of these professionals is the prevention of carious lesions and maintenance of the primary teeth in the oral cavity for space maintenance and preservation of alveolar bone for future implant therapy6. Orthodontic treatment allows for the creation or redistribution of spaces for later rehabilitation8. If the primary teeth had not been maintained in the present case, the final prosthetic spaces would not have been large enough for the placement of crowns with the dimensions of mandibular second premolars. The greatest challenge in the treatment of hypodontia is related to treatment planning, which usually depends on the severity of the hypodontia6. The treatment options available for these cases are the maintenance of the primary teeth; orthodontic space closure; space maintenance; restoration with adhesive or fixed dentures, tooth transplantation or dental implants; or orthodontic space redistribution to facilitate the prosthetic treatment13.

Maintenance of the primary teeth should be considered if root resorption has not affected their stability24. When extraction of the primary teeth is indicated, orthodontic treatment should be performed to prevent migration of the adjacent and antagonist teeth and to allow for adequate space for prosthetic rehabilitation. In the present case, besides the maintenance of the primary teeth throughout the orthodontic treatment, the prosthetic spaces preserved by provisional crowns were also important because if they had not been completely closed, the Class I angle could not have been achieved, possibly causing occlusal and facial alterations14, while the maintenance of the original space would require prosthetic crowns with different characteristics than those observed on either first molars or second premolars.

The treatment with dental implants may be the best option for patients with hypodontia because this procedure is predictable, stable and provides excellent esthetic results18. Other treatment options, such as conventional partial fixed dentures, may cause biological damage due to the need to reduce the intact tooth structure; in young patients, the risk of pulp damage is high due to the large volume of the pulp chamber8,15. When treatment with dental implants is indicated, the possible postpubertal vertical growth of the facial skeleton should be considered14, and consecutive cephalometric analyses should be performed to establish the period of growth. These analyses revealed completion of physical growth of our patient; thus, restoration of the prosthetic space with implants was the treatment of choice.

The implant therapy in individuals with hypodontia may be complex due to the limitations caused by the reduced bone thickness8,15, impairing the ideal positioning of implants or requiring the use of implants with a small platform. For this reason, bone grafting is often indicated to compensate for this deficiency. Implants with a small platform prevent the achievement of an adequate emergence profile for wide teeth, such as the posterior teeth. In this case, the maintenance of the primary teeth during orthodontic treatment favors the maintenance of the bone architecture, allowing for the placement of implants with a regular platform.

CONCLUSION

The successful management of hypodontia in this case was achieved by a multidisciplinary treatment. Maintenance of the primary teeth combined with orthodontic treatment allowed for the placement of endosseous implants to replace the missing teeth, enhancing the esthetics and function.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbo B, Razzoog ME. Management of a patient with hypodontia, using implants and all-ceramic restorations: a clinical report. J Prosthet Dent. 2006;95(3):186–189. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boruchov MJ, Green LJ. Hypodontia in human twins and families. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1971;60:165–174. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(71)90032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brook AH. A unifying aetiological explanation for anomalies of human tooth number and size. Arch Oral Biol. 1984;29:373–378. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(84)90163-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burzynski NJ, Escobar VH. Classification and genetics of numeric anomalies of dentition. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1983;19:95–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cameron J, Sampson WJ. Hypodontia of the permanent dentition. Case reports. Aust Dent J. 1996;41(1):1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1996.tb05645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhanrajani PJ. Hypodontia: etiology, clinical features, and management. Quintessence Int. 2002;33(4):294–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Egermark-Eriksson I, Lind V. Congenital numerical variation in the permanent dentition. D. Sex distribution of hypodontia and hyperodontia. Odontol Revy. 1971;22(3):309–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forgie AH, Thind BS, Larmour CJ, Mossey PA, Stirrups DR. Management of hypodontia: restorative considerations. Part III. Quintessence Int. 2005;36(6):437–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grahnen H. Hypodontia in the permanent dentition. A clinical and genetical investigation. Odontol Revy. 1956;7(3):1–100. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gravely JF, Johnson DB. Variation in the expression of hypodontia in monozygotic twins. Dent Pract Dent Rec. 1971;21:212–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris EF, Clark LL. Hypodontia: an epidemiologic study of American black and white people. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;134(6):761–767. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hobkirk JA, Brook AH. The management of patients with severe hypodontia. J Oral Rehabil. 1980;7(4):289–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.1980.tb00447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hobson RS, Carter NE, Gillgrass TJ, Jepson NJ, Meechan JG, Nohl F, et al. The interdisciplinary management of hypodontia: the relationship between an interdisciplinary team and the general dental practitioner. Br Dent J. 2003;194(9):479–482. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4810184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holst S, Geiselhoringer H, Nkenke E, Blatz MB, Holst AI. Update implant-retained restorative solutions in patients with hypodontia. Quintessence Int. 2008;39(10):797–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jepson NJ, Nohl FS, Carter NE, Gillgrass TJ, Meechan JG, Hobson RS, et al. The interdisciplinary management of hypodontia: restorative dentistry. Br Dent J. 2003;194(6):299–304. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4809940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kinzer GA, Kokich VO., Jr Managing congenitally missing lateral incisors. Part II: tooth-supported restorations. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2005;17(2):76–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.2005.tb00089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larmour CJ, Mossey PA, Thind BS, Forgie AH, Stirrups DR. Hypodontia-a retrospective review of prevalence and etiology. Part I. Quintessence Int. 2005;36(4):263–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lazzara R, Siddiqui AA, Binon P, Feldman SA, Weiner R, Phillips R, et al. Retrospective multicenter analysis of 3i endosseous dental implants placed over a five-year period. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1996;7(1):73–83. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.1996.070109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lucas J. The syndromic tooth--the aetiology, prevalence, presentation and evaluation of hypodontia in children with syndromes. Ann R Australas Coll Dent Surg. 2000;15:211–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murdock S, Lee JY, Guckes A, Wright JT. A costs analysis of dental treatment for ectodermal dysplasia. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005;136(9):1273–1276. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2005.0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nunn JH, Carter NE, Gillgrass TJ, Hobson RS, Jepson NJ, Meechan JG, et al. The interdisciplinary management of hypodontia: background and role of paediatric dentistry. Br Dent J. 2003;194(5):245–251. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4809925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Polder BJ, Van't Hof MA, Van der Linden FP, Kuijpers-Jagtman AM. A meta-analysis of the prevalence of dental agenesis of permanent teeth. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2004;32(3):217–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2004.00158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Savarrio L, McIntyre GT. To open or to close space--that is the missing lateral incisor question. Dent Update. 2005;32(1):16–25. doi: 10.12968/denu.2005.32.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sletten DW, Smith BM, Southard KA, Casko JS, Southard TE. Retained deciduous mandibular molars in adults: a radiographic study of long-term changes. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2003;124(6):625–630. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]