Abstract

Background: Bisphenol A (BPA) is used to produce polycarbonate plastics and epoxy resins that are widely used in everyday products, such as food and beverage containers, toys, and medical devices. Human biomonitoring studies have suggested that a large proportion of the population may be exposed to BPA. Recent epidemiological studies have reported correlations between increased urinary BPA concentrations and cardiovascular disease, yet the direct effects of BPA on the heart are unknown.

Objectives: The goal of our study was to measure the effect of BPA (0.1–100 μM) on cardiac impulse propagation ex vivo using excised whole hearts from adult female rats.

Methods: We measured atrial and ventricular activation times during sinus and paced rhythms using epicardial electrodes and optical mapping of transmembrane potential in excised rat hearts exposed to BPA via perfusate media. Atrioventricular activation intervals and epicardial conduction velocities were computed using recorded activation times.

Results: Cardiac BPA exposure resulted in prolonged PR segment and decreased epicardial conduction velocity (0.1–100 μM BPA), prolonged action potential duration (1–100 μM BPA), and delayed atrioventricular conduction (10–100 μM BPA). These effects were observed after acute exposure (≤ 15 min), underscoring the potential detrimental effects of continuous BPA exposure. The highest BPA concentration used (100 μM) resulted in prolonged QRS intervals and dropped ventricular beats, and eventually resulted in complete heart block.

Conclusions: Our results show that acute BPA exposure slowed electrical conduction in excised hearts from female rats. These findings emphasize the importance of examining BPA’s effect on heart electrophysiology and determining whether chronic in vivo exposure can cause or exacerbate conduction abnormalities in patients with preexisting heart conditions and in other high-risk populations.

Citation: Posnack NG, Jaimes R III, Asfour H, Swift LM, Wengrowski AM, Sarvazyan N, Kay MW. 2014. Bisphenol A exposure and cardiac electrical conduction in excised rat hearts. Environ Health Perspect 122:384–390; http://dx.doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1206157

Introduction

Bisphenol A (BPA) is one of the most widely used chemicals worldwide, with > 8 million pounds produced each year (Vandenberg et al. 2010). BPA is a component of polycarbonate plastics and epoxy resins, which are used in many plastic consumer products, including food and drink containers, water pipes, thermal paper and paper products (e.g., receipts, paper towels), toys, safety equipment, electronics, dental monomers, and medical equipment and tubing. Vandenberg et al. (2007) reported that BPA can leach from these products under normal conditions. Despite the increasing popularity of BPA-free plastics, BPA is still found in many consumer products. Indeed, human biomonitoring studies suggest that a large proportion of the population may be exposed to BPA, including both children and adults (Calafat et al. 2005, 2008). BPA exposure rates range dramatically depending on lifestyle factors, with neonates in intensive care units (4.4 nM–4 μM) and industrial workers (0.024–8.5 μM) having overall higher urinary BPA concentrations (Calafat et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2012). Human serum BPA levels are actively debated, with estimates ranging from 0.001 to 0.3 μM for adults (Kaddar et al. 2009; Lee et al. 2008; Padmanabhan et al. 2008; Schönfelder et al. 2002; Vandenberg et al. 2010). Patients undergoing multiple medical interventions, such as neonates in intensive care, may have even higher levels of BPA in the blood. However, BPA serum levels have not been measured in this patient population.

There is evidence that increased exposure to endocrine disruptors such as BPA might contribute to the onset and progression of disease (Braun and Hauser 2011; Chapin et al. 2008; Diamanti-Kandarakis et al. 2009; Richter et al. 2007; Vandenberg et al. 2007; vom Saal et al. 2007). Recent epidemiological studies have shown an association between BPA exposure and cardiovascular disease. For example, higher urinary concentrations of BPA have been associated with an increased risk of coronary artery disease (Melzer et al. 2010, 2012), hypertension (Shankar et al. 2012), carotid atherosclerosis (Lind and Lind 2011), angina and myocardial infarction (Lang et al. 2008), and a decrease in heart rate variability (Bae et al. 2012). Although the latter is primarily attributed to neuronal influences, decreased heart rate variability can also indicate alterations in ion channel currents that drive pacemaker depolarization (Papaioannou et al. 2013). In addition, in vitro experimental studies have shown that higher BPA exposure concentrations modify heart rate in isolated atrial preparations (Pant et al. 2011). Both of these observations suggest alterations of ionic currents in nodal cells, which can influence nodal and bundle branch conduction. Moreover, if BPA induces ion channel alterations in atrial tissue, exposure will likely affect ion channels in other tissue compartments. Importantly, the effect of BPA on heart electrophysiological function has not been examined. We aimed to systematically study the effect of BPA on cardiac conduction by conducting controlled experiments on excised whole rat hearts. These experiments provide new measurements for important electrophysiological parameters, including atrioventricular (AV) conduction and ventricular conduction velocity.

Materials and Methods

Animals. Experiments were conducted using excised hearts from adult female Sprague-Dawley rats (2–3 months of age; body weight, 200–300 g; n = 12), purchased from Hilltop Lab Animals (Scottsdale, PA). Studies were limited to females because previous reports (Belcher et al. 2012; Yan et al. 2011) have claimed that the cardiac effects of BPA are sex specific due to its estrogenic properties. To account for the possible effects of estrous cyclicity on cardiac electrophysiology, each animal served as its own control, with all BPA measurements computed as a percent change from the control (no BPA). Animals were housed in The George Washington University (GWU) animal care facility under standard environmental conditions [12:12 hr light:dark cycle, 64–79°C, 30–70% humidity, corn cob bedding (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN)] with free access to food (2018 Teklad Global rodent chow; Harlan Laboratories) and carbon-filtered tap water. Animals were housed in groups of 2 or 3 animals per cage for 2 weeks prior to experimentation. All animals were treated humanely and with regard for alleviation of suffering. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at GWU.

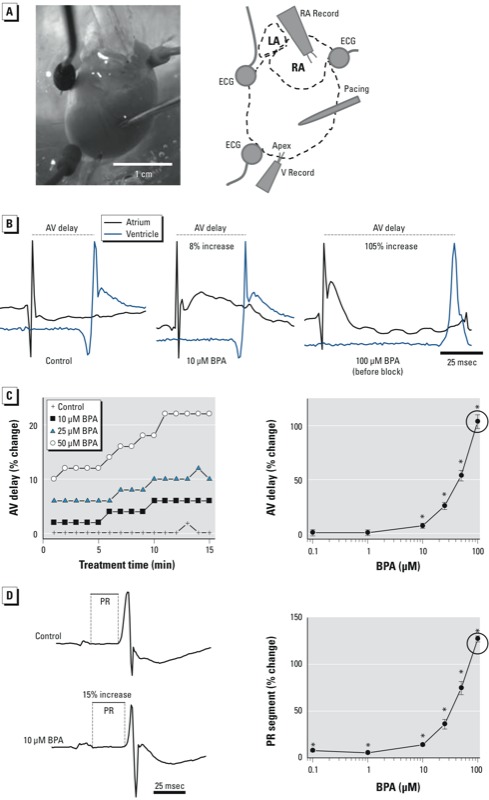

Excised heart preparation. Hearts were excised and Langendorff-perfused with a modified Krebs Henseleit buffer (Gillis et al. 1996), as previously described (Mercader et al. 2012). Hearts were placed in a temperature-controlled chamber (Figure 1A) for electrical measurements. To reduce motion, the perfusate was supplemented with 10 μM blebbistatin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Figure 1.

BPA exposure and prolonged AV conduction and ECG segments in excised rat hearts. (A) Heart preparation and electrode placement. Abbreviations: LA, left atrium; RA, right atrium; RA Record, right atrium recording electrode; V Record, ventricle recording electrode. (B) AV conduction delay after exposure to control media or BPA at 10 or 100 μM. (C) AV delay after BPA exposure over time (left), and by dose (0.1–100 μM) measured 15 min after exposure (right). (D) PR segment elongation after exposure to 10 μM BPA (left), and PR segment prolongation measured 15 min after exposure to BPA (0.1–100 μM; right). Measurements for 100 μM BPA were performed prior to the onset of AV block (indicated by circle). Values shown in (C,D) are mean ± SE; n ≥ 3 for each measurement. *p < 0.05. p‑Values for dose response were determined by one-way ANOVA; the lowest dose with statistical significance was determined by paired t-tests.

General protocol. BPA (> 99% purity; Sigma-Aldrich) stock solution was prepared fresh for each experiment. For the stock solution, BPA was dissolved in 100% ethanol. The final dilutions were prepared by adding stock solution directly to the perfusate media to obtain BPA concentrations of 0 (control) to 100 μM, with total ethanol concentrations ranging from 0.01% for the control to 0.02% for 100 μM BPA. Precautions were maintained throughout the study to prevent BPA contamination from external sources [i.e., solutions mixed and stored in glass bottles, or in BPA-free Tygon and C-Flex tubing (Cole Parmer, Vernon Hills, IL) used for Langendorff-perfusion]. However, we did not analyze the perfusate media for BPA contamination.

Excised hearts maintained electrophysiological function for > 3 hr with control media perfusion (no BPA). Each study began midday and was completed in 1–2 hr. The procedure included the following steps: a) The excised heart was perfused with control media; b) electrodes and electrocardiogram (ECG) leads were positioned (5–10 min); c) ECG and AV conduction signals during sinus rhythm were recorded (15-min equilibration period); d) the pacing protocol was implemented and optical signals were acquired; e) BPA was diluted directly in perfusate media to achieve the appropriate final concentration; f ) ECG and AV conduction signals during sinus rhythm were recorded (15 min); and g) the pacing protocol was implemented and optical signals acquired. Steps e–g were repeated for each BPA concentration.

For each preparation, the heart was exposed to an average of three BPA concentrations added incrementally to the perfusate media (i.e., animal 1: control media → 0.1 μM → 1 μM → 10 μM BPA; animal 2: control media → 1 μM → 10 μM → 25 μM BPA); each exposure lasted 15 min. Each animal served as its own control, with measurements normalized to control perfusion in the same heart and expressed as a percent change. This allowed us to account for variations in electrode position for each experiment and to reduce any influence of estrous cyclicity on cardiac conduction measurements.

The epicardial pacing protocol consisted of pacing the heart with 2 mA pulses (5 msec duration) for ≥ 5 sec at 5–15 Hz pacing frequencies (incremented stepwise by 1 Hz). There was a 30-sec interval after each pacing sequence before beginning the next.

Electrical measurements. AV conduction was measured as the time difference between activation recorded by each electrode (right atrium and ventricular apex) during sinus rhythm (Figure 1A,B), as determined by the maximum signal derivative. For the dose–response analysis, we measured the AV delay during sinus rhythm after 15 min exposure to control or BPA-containing media. The sinus heart rate remained stable during perfusion with control media (4.1 ± 1 Hz) but slowed after exposure to 50 and 100 μM BPA (3.6 ± 1 Hz and 3.3 ± 1 Hz, respectively). However, this slowing did not reach significance until the onset of the AV block. All electrical signals were amplified using a Dagan EX4-400 differential amplifier (Dagan Corporation, Minneapolis, MN) and recorded using a PowerLab data acquisition system (ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO). Electrical signals, including AV delay and ECG segments, were analyzed using LabChart software (ADInstruments; n ≥ 4 signals per concentration for each independent experiment).

Epicardial conduction velocity (CV) measurements. We examined the effect of BPA on CV using epicardial electrodes and optical mapping. CV is rate dependent and decreases at high pacing frequencies; such rate-dependent changes are referred to as “CV restitution” (Kleber and Rudy 2004; Qu et al. 2004). Therefore, we implemented a pacing protocol that gradually increased pacing frequencies (5–15 Hz) to reveal the effect of BPA on CV. Epicardial conduction time (seconds) was computed as the difference between the onset of the pacing pulse and the activation time measured from the apical recording electrode (Figure 1A). Epicardial CV (centimeters per second) was computed by dividing conduction time by electrode separation distance. CVs were calculated for each pacing frequency (5–15 Hz). Measurements were normalized to corresponding controls at 5-Hz pacing frequency (near the intrinsic rate). Electrical signals were analyzed using LabChart software (n ≥ 4 signals per concentration for each independent experiment).

Optical mapping of wavefront propagation. Optical mapping is a powerful technique for studying cardiac electrical conduction, which has been used for more than a decade to reveal mechanisms of arrhythmia (Laughner et al. 2012). We used optical mapping of a potentiometric dye (RH237; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) to study alterations in electrical conduction using techniques developed in our laboratory (Asfour et al. 2011; Kay et al. 2006; Swift et al. 2008). RH237 dye kinetics are faster than changes in transmembrane potential during an action potential (Rosenbaum and Jalife 2001), and RH237 has been used successfully in our laboratory to study cardiac electrical activity. We administered RH237 to the aorta (5 mL of a 10-μM solution) before beginning a pacing protocol (described above). To record optical action potentials, the epicardium was illuminated using an LED spotlight (530/35 nM; Mightex, Pleasanton, CA). RH237 fluorescence was longpass filtered at 680 nm and imaged using a CCD (charge-coupled device) camera (Ixon DV860; Andor Technology, Belfast, UK), as described previously by Mercader et al. (2012). At each pacing frequency, optical signals were acquired and mapping data was quickly viewed to verify continuous elliptical wavefront propagation originating from the pacing electrode. Activation times were identified for each pixel, and local CVs were computed (Bayly et al. 1998) to generate isochronal maps. We computed an average CV by averaging the values of individual CV vectors across the epicardial field of view. Optical action potentials were analyzed using custom Matlab software (MathWorks, Natick, MA) to measure action potential duration at 90% (APD90) and depolarization and repolarization times.

Statistical analysis. All values are presented as mean ± SE, unless otherwise noted, with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Mean values are expressed as a percentage of baseline during perfusion with control media before the addition of BPA. The lowest dose showing a statistically different effect (p < 0.05) was determined according to one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by paired t-tests (Bokkers and Slob 2005). All results were computed from a minimum of three independent experiments (animals) for each BPA dose examined (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of statistical significance for each measured electrophysiological parameter.

| Measurement | 0.1 μM BPA (n = 3) | 1.0 μM BPA (n = 4) | 10 μM BPA (n = 4) | 25 μM BPA (n = 7) | 50 μM BPA (n= 7) | 100 μM BPA (n = 7) | Potential primary mechanisms of result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sinus rate slowing | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | Reduced Ca2+ current in SA node cells |

| AV delay | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Reduced Ca2+ current in AV node cells |

| Prolonged PR segment | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Impaired conduction in atria, AV node, and bundle branches |

| Reduced ventricular CV | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Reduced Na+ current and gap junction conductance |

| Prolonged APD | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Reduced K+ and Ca2+ currents during repolarization |

| Reduced maximum paced frequency | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Increased ventricular refractoriness due to long APD |

| Abbreviations: Ca2+, calcium ion; K+, potassium ion; Na+, sodium ion. Y denotes significant changes (p < 0.05) in parameter differences from control/untreated, and N denotes insignificant changes. Potential primary mechanisms for the effect of BPA on measured parameter differences are shown in the right-hand column. BPA dose ranges correspond to clinical levels in blood (0.1–1 μM) and in urine (0.1–10 μM), as well as to concentrations typically used in toxicological studies (0.1–100 μM). n indicates the number of independent experiments/animals examined is shown for each dose. | |||||||

In addition, one-way ANOVA was performed to ensure that significant differences in cardiac conduction (including maximum pacing frequency and conduction velocity) were not present between control animals during control media perfusion (p > 0.05; data not shown).

Results

Effect of BPA exposure on AV conduction delay. We measured AV conduction delay throughout sinus rhythm, during both control and BPA exposures. AV conduction delay remained stable during control perfusion but lengthened significantly after BPA exposure, beginning at 10 μM (Figure 1B,C). For example, AV conduction increased by 7.5% and 26% after exposure to 10 μM and 25 μM BPA, respectively. Exposure to 100 μM BPA resulted in sustained and complete AV block (see Supplemental Material, Figure S1). Therefore, at 100 μM BPA, conduction delays were computed immediately before the onset of AV block, which usually happened within minutes. We confirmed AV conduction delays by measuring the PR segment time in the ECG, which lengthened after 15 min of exposure to BPA at all concentrations. For example, PR segment time increased by 8% for 0.1 μM BPA and 14% for 10 μM BPA (Figure 1D).

Heart block after exposure to high BPA concentrations. Exposure to 100 μM BPA resulted in third-degree AV block. This was detected by dropped ventricular beats, in which atrium impulses failed to propagate to the ventricles (see Supplemental Material, Figure S1). Ventricular activation then resumed and was driven by an accessory pacemaker; changes in QRS morphology and lengthening were also detected in ECG recordings.

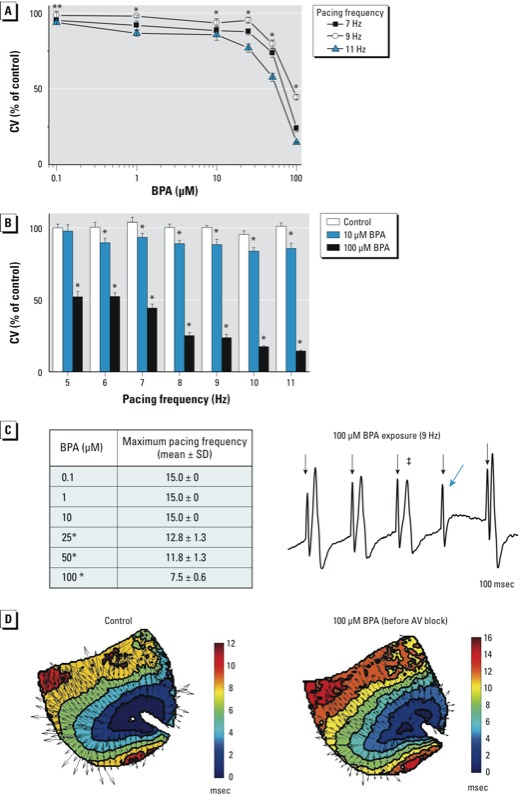

Effect of BPA exposure on ventricular CV. Two-way ANOVA indicated significant reductions in CV with both pacing frequency and BPA exposure, compared with control (p < 0.0001). The interaction of BPA and pacing frequency was also significant (p < 0.001), indicating that BPA altered the CV restitution properties of the tissue. At lower BPA concentrations (0.1–50 μM), significantly reduced CVs were observed at high pacing rates (Figure 2A). For example, while pacing at 11 Hz, the CV for 0.1 μM BPA was 94% of control. For 10 μM BPA, the CV was 94% of control at 7 Hz, and dropped to 86% at 11 Hz. We observed no significant reduction in CV between pacing frequencies during control perfusion (Figure 2B). In contrast, CVs were significantly reduced during BPA exposure, even at pacing frequencies near the intrinsic heart rate (Figure 2B). Each stimulus pulse for pacing rates from 5 to 15 Hz initiated a beat (1:1 capture) during purfusion with control media and 0.1–10 μM BPA. However, the maximum frequency of 1:1 capture was reduced with exposure to higher BPA concentrations (25–100 μM) (Figure 2C, left), indicating an increased refractory period. In these instances, CV was calculated using the last captured signal from a train of successfully propagated impulses (Figure 2C, right). Importantly, we did not detect significance in maximum pacing frequency or CV measurements between animals during control perfusion (ANOVA, p > 0.05; data not shown).

Figure 2.

BPA exposure and reduced ventricular CV. (A) Reduction in CV at high pacing frequencies (7–11 Hz) 15 min after exposure to BPA (0.1–100 μM). (B) Reduction in CV with increasing pacing frequency after exposure to 10 or 100 μM BPA. (C) Maximum rate of ventricular activation 15 min after exposure to BPA (left), and example for CV calculation using the last captured signal (denoted by ‡) (right); pacing spikes are indicated by down arrows (↓), and the blue arrow indicates loss of capture. (D) Wavefront propagation across the ventricular epicardium at 9 Hz pacing frequency after exposure to control media (left) or 100 μM BPA for 1 min (right); arrows indicate local CVs. Values shown in (A–C) are mean ± SE; n ≥ 3 for each measurement. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.05 at 9 and 11 Hz, but not 7 Hz. p‑Values for dose response were determined by one- or two-way ANOVA; the lowest dose with statistical significance was determined by paired t-tests.

Optical mapping data confirmed that paced beats propagated as elliptical wavefronts that emanated from the pacing electrode, even at high BPA concentrations. An example of this is shown in Figure 2D, which illustrates reduction in CV after only 1 min exposure to 100 μM BPA. Averaging the lengths of individual CV vectors across the epicardial field of view revealed a reduction of ventricular CV by 21% across the epicardial surface.

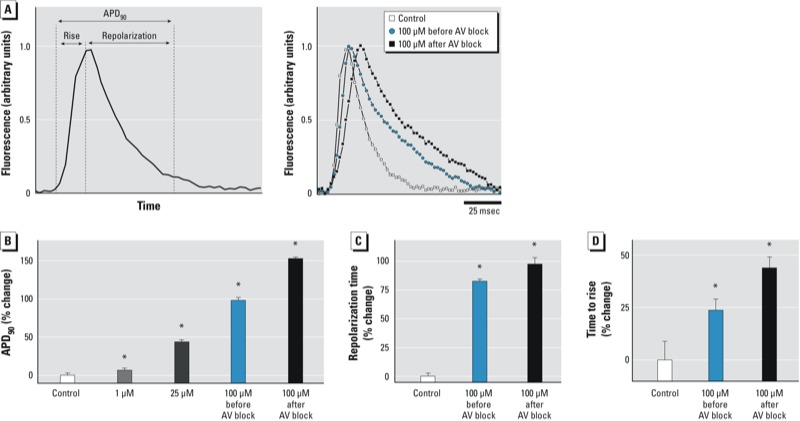

BPA exposure and prolonged ventricular APD. Exposure to increasing BPA concentrations resulted in slowed CV in a rate-dependent manner, suggesting alterations in the kinetics of membrane depolarization and/or repolarization. Time intervals of depolarization and repolarization were measured using optical action potentials (Figure 3A). We found that APD90 was significantly prolonged in hearts exposed to 1–100 μM BPA, in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 3B). For example, APD90 increased by 7% for 1 μM BPA and 44% for 25 μM BPA. Results from 100 μM BPA revealed a larger relative change in repolarization time (98% after third-degree AV block; Figure 3C) than depolarization time (44% after third-degree AV block; Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

BPA exposure and prolonged ventricular APD90. (A) Optical action potentials from ventricular tissue (8 Hz); (left) how mearurements were made, and (right) examples of optical action potentials. (B) APD90 was prolonged after BPA exposure, likely due to longer repolarization (C) and depolarization (D) times. Dose response determined by one-way ANOVA; lowest dose with significance was determined by paired t-tests. Values shown are mean ± SE; n ≥ 3 for each measurement. *p < 0.05. p‑Values for dose response were determined by one-way ANOVA; the lowest dose with statistical significance was determined by paired t-tests.

Discussion

Although toxic effects of BPA on reproduction and development have been reported (Vandenberg et al. 2007), a link between BPA exposure and cardiovascular disease was found more recently (Lang et al. 2008; Lind and Lind 2011; Melzer et al. 2010, 2012; Shankar et al. 2012). Only a few studies have examined BPA’s adverse cardiac effects and none have described the adverse effects of BPA on electrical conduction within intact hearts. In a study using isolated atrial preparations, Pant et al. (2011) observed that exposure to high concentrations of BPA decreased heart rate via a nitric oxide–dependent signaling mechanism. In another study using isolated ventricular myocytes, Yan et al. (2011) found that BPA exposure (0.001–1 nM), coupled with 17β-estradiol treatment, modified calcium handling.

Our experiments were designed to show the dose–response relationship of BPA on whole-heart conduction abnormalities in female rats. We observed changes in cardiac conduction beginning at 0.1 μM BPA. This concentration is within the range of previously reported human urinary concentrations (0.024–8.5 μM; Table 1) and is within the upper limit of measured human serum levels (0.001–0.3 μM) in high-risk populations (Calafat et al. 2009; Kaddar et al. 2009; Lee et al. 2008; Padmanabhan et al. 2008; Schönfelder et al. 2002; Vandenberg et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2012). Such concentrations may be present in individuals chronically exposed to high levels of BPA (i.e., industrial workers) and those with reduced metabolic capacities (i.e., fetuses and infants). Although BPA is not considered a persistent compound, there is controversy regarding whether or not BPA is immediately cleared from the body (Teeguarden et al. 2012; vom Saal et al. 2012). Importantly, in the present study, we observed changes in cardiac conduction after acute (≤ 15 min) BPA exposure, a time frame that is significantly less than BPA’s reported half-life (Shin et al. 2004; Volkel et al. 2002).

In the present study, we observed significant, although modest, changes in cardiac conduction beginning at 0.1 μM BPA. Notably, small changes in ion channel expression and/or electrical conduction can lead to pathological outcomes (Amin et al. 2010; Grant 2009). At low micromolar concentrations of BPA (10 μM), we observed a concentration-dependent slowing of AV conduction that began within 15 min of exposure (Table 1). AV conduction delay was confirmed by measuring PR segment time, with delays found at BPA doses as low as 0.1 μM BPA. We also found that BPA exposure resulted in prolonged APD90 and slowed ventricular CV beginning at 1 μM and 0.1 μM, respectively. CV is rate dependent and is reduced at high pacing frequencies, a phenomenon known as CV restitution that is primarily established by the recovery kinetics of sodium channels (Kleber and Rudy 2004; Qu et al. 2004). We observed CV slowing at high pacing rates in control measurements, as well as a significantly greater slowing of CV after BPA exposure. High pacing frequencies mimic increased heart rates, which could result from increased work/exercise or stress. When heart rates are elevated, individuals with increased BPA exposure could be susceptible to adverse cardiac effects, including electrical conduction that is slower than normal. In our study we also observed that the maximum heart rate that could be achieved was significantly reduced after BPA exposure. For example, at 25 μM BPA, maximum pacing frequency was reduced from 15 Hz to 12.8 Hz. This result indicates an increased refractory period, which could be caused by prolonged sodium channel inactivation resulting from reduced potassium current and longer action potential duration (Jalife et al. 2009).

The cardiac effects of BPA were pronounced at high concentrations. Exposure to 100 μM BPA resulted in complete AV block and QRS interval widening, which is consistent with slowed ventricular conduction that may be attributed to reduced gap junction conductance (Gillum et al. 2009), reduced sodium channel activity, and activations that originate outside the specialized conduction system. We also detected a lengthening in APD90, with a larger relative change in repolarization time than in depolarization time. This indicates that BPA-induced tissue refractoriness could be the dominant mechanism of conduction failure at high concentrations and pacing rates. We recognize that cardiac exposure to 100 μM BPA exceeds a clinically relevant exposure concentration; however, these observed effects may provide a hint to the underlying mechanisms of BPA on the conduction system, which can be examined further, and also allow for direct comparison with previously reported mechanical effects (Pant et al. 2011).

Our results are significant because altered electrical conduction is a mechanism of reentrant arrhythmias (Roden 1996), which can cause tachycardia and fibrillation in both the atria and ventricles. The effects of BPA exposure—even at low BPA concentrations—that we observed in the present study, could be symptomatic at high heart rates, particularly in elderly patients whose hearts tend to be larger and more fibrotic (Biernacka and Frangogiannis 2011). In addition, action potential prolongation is a common mechanism of conduction block, particularly at high heart rates (rate-dependent block), and is known to be a trigger for reentrant arrhythmias (Rosenbaum et al. 1973). Reduced CV may also cause reentrant arrhythmias, particularly in patients with dilated hearts (Akar et al. 2004). These adverse effects are important, even though we did not observe such arrhythmias in our studies, which is most likely the result of the small size of the rat heart and its intrinsically low susceptibility to arrhythmias.

The present study compliments previous studies of the effect of BPA on mechanical function. For example, two studies reported that BPA-induced mechanical dysfunction was sex-specific because of BPA’s estrogenic properties (Belcher et al. 2012; Yan et al. 2011). In our study, as in these previous studies, each animal served as its own control to minimize any potential effects of estrous cyclicity. This reduced the influence of the estrous cycle on measurements of cardiac conduction, as evidenced by a lack of statistical significance in measurements between animals during control perfusion (ANOVA, p > 0.05; data not shown). As a result, in our paired-animal controlled study using excised hearts, we observed slowing of cardiac electrical conduction after BPA exposure.

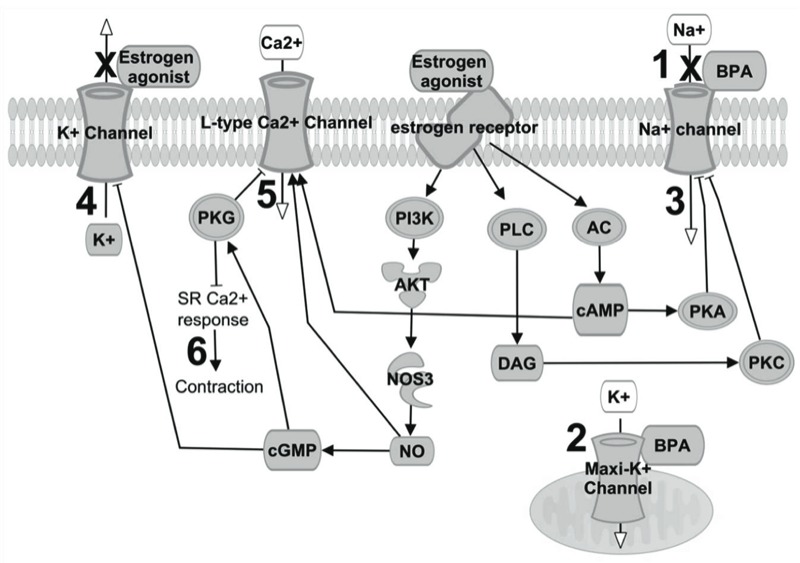

Such impaired electrical conduction may potentially be attributed to BPA’s interaction with ion channels and/or estrogen receptors (Figure 4; see also Supplemental Material, Table S1). BPA can bind directly to and block the Nav1.5 sodium channel (O’Reilly et al. 2012), which is responsible for phase 0 depolarization in ventricular myocytes (Figure 4, mechanism 1). Inhibition of the fast sodium current by BPA would certainly reduce ventricular CV. BPA can also activate Maxi-K channels in coronary smooth muscle (mechanism 2; Asano et al. 2010). A similar interaction with sarcolemma potassium channels could hyperpolarize cardiomyocytes and decrease cardiac excitability. Modifications in either sodium or potassium channel current could also explain the increased tissue refractoriness we observed at high pacing frequencies.

Figure 4.

Possible mechanisms underlying BPA’s impairment of cardiac conduction. Abbreviations: AC, adenylate cyclase; AKT, protein kinase B; Ca2+, calcium; cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate; cGMP, cyclic guanosine monophosphate; DAG, diacylglycerol; ER, estrogen receptor; K+, potassium; maxi-K+ channels, Ca2+-activated K+ channels; Na+, sodium; NO, nitric oxide; NOS3, nitric oxide synthase 3; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; PKA, protein kinase A; PKC, protein kinase C; PKG, protein kinase G; PLC, phospholipase C. BPA binding can (1) block voltage-gated Na+ channels or (2) activate maxi-K+ channels (located in the mitochondria of cardiomyocytes, or in sarcolemma of cardiac neurons and endothelial cells). ER agonists can (3) inhibit Na+ current via activation of the PKC–PKA pathway, (4) inhibit the K+ current, and (5) inhibit the L-type Ca2+ current via the NO/cGMP/PKG pathway, which acts as an antagonist to cAMP activation. This effect is concentration dependent because NO can activate Ca2+ channels at basal concentrations. (6) BPA can reduce cardiac contractility, an effect that is also dependent on NO concentration (see Supplemental Material, Table S1).

Because BPA is classified as a xenoestrogen, it is plausible that the impaired cardiac conduction we observed was mediated by its interaction with estrogen receptors (ERs) and the resultant downstream pathways. Animals that undergo ovariectomy have shortened PR intervals and shorter ventricular refractory periods (Saba et al. 2002), which can be explained by the effects of ER agonists on multiple ion currents. ER agonists can inhibit voltage-gated sodium current (mechanism 3; Wang et al. 2013) and decrease potassium current, which can prolong APD and repolarization time (mechanism 4; Berger et al. 1997; Kurokawa et al. 2008; Nakajima et al. 1999; Tanabe et al. 1999). ER agonists can also decrease L-type calcium current (mechanism 5; Jiang et al. 1992; Meyer et al. 1998; Nakajima et al. 1999), which can prolong ventricular APD (Berger et al. 1997; Tanabe et al. 1999). Because the L-type calcium current is the primary depolarizing current in sinoatrial and AV nodal cells, a reduction in calcium current can lead to AV block (Hancox and Mitcheson 1997; Kawai et al. 1981). Similar to other ER agonists (Jiang et al. 1992; Liew et al. 2004), BPA has also been found to decrease cardiac contractility, possibly through its interaction with ERs and/or activation of the nitric oxide/cGMP (cyclic guanosine monophosphate) pathway (mechanism 6; Belcher et al. 2012; Pant et al. 2011). An increase in nitric oxide levels can also attenuate the L-type calcium current (Han et al. 1997), which could be an important mechanism for dropped beats and AV block at high BPA concentrations.

Conclusion

Our results show that acute BPA exposure alters electrical conduction in excised hearts from female rats. This could be the result of a block in the Nav1.5 sodium channel, a reduction in gap junction conductance, a reduction in calcium channel opening due to a nitric oxide/cGMP pathway, and/or inhibition of potassium channels via the estrogenic properties of BPA. Because of the complex interactions between these pathways (Figure 4), additional studies are needed to fully identify the mechanisms responsible for BPA’s effects, and to determine whether these mechanisms differ by exposure levels and treatment time.

One limitation of the present study is that we examined the effects of BPA on cardiac conduction after acute ex vivo exposure. Whether such conditions are relevant to chronic in vivo exposure is not yet known and requires additional studies. These additional experiments are important because BPA may motivate conduction abnormalities in individuals with preexisting heart conditions, such as AV conduction dysfunction, disease of the cardiac electrical conduction system, or fibrosis of the atria and/or ventricles. Other high-risk populations, such as industrial workers, prenatal and neonatal patients with reduced metabolic capacity, and elderly patients with substantial cardiac fibrosis may also be affected. Overall, our findings emphasize the importance of examining how BPA exposure affects heart electrophysiology and determining whether chronic in vivo exposure can cause or exacerbate conduction abnormalities in patients with preexisting heart conditions and in other high-risk populations.

Supplemental Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge S. March and N. Serafino for technical assistance, A. Arutunyan for helpful discussions, and H. Mahmoud for statistical advice.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants F32ES019057 and K99ES023477 to N.G.P. and grant R01HL095828 to M.W.K.).

The authors declare they have no actual or potential competing financial interests.

References

- Akar FG, Spragg DD, Tunin RS, Kass DA, Tomaselli GF. Mechanisms underlying conduction slowing and arrhythmogenesis in nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2004;95(7):717–725. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000144125.61927.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin AS, Tan HL, Wilde AA. Cardiac ion channels in health and disease. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7(1):117–126. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asano S, Tune JD, Dick GM. Bisphenol A activates maxi K (Kca1.1) channels in coronary smooth muscle. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160(1):160–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00687.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asfour H, Swift LM, Sarvazyan N, Doroslovacki M, Kay MW. Signal decomposition of transmembrane voltage-sensitive dye fluorescence using a multiresolution wavelet analysis. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2011;58(7):2083–2093. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2011.2143713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae S, Kim JH, Lim YH, Park HY, Hong YC. Associations of bisphenol A exposure with heart rate variability and blood pressure. Hypertension. 2012;60(3):786–793. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.197715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayly PV, KenKnight BH, Rogers JM, Hillsley RE, Ideker RE, Smith WM. 1998Estimation of conduction velocity vector fields from epicardial mapping data. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 455563–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belcher SM, Chen Y, Yan S, Wang HS. Rapid estrogen receptor-mediated mechanisms determine the sexually dimorphic sensitivity of ventricular myocytes to 17β-estradiol and the environmental endocrine disruptor bisphenol A. Endocrinology. 2012;153(2):712–720. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger F, Borchard U, Hafner D, Putz I, Weis TM. Effects of 17beta-estradiol on action potentials and ionic currents in male rat ventricular myocytes. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1997;356(6):788–796. doi: 10.1007/pl00005119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biernacka A, Frangogiannis NG. Aging and cardiac fibrosis. Aging Dis. 2011;2(2):158–173. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokkers BG, Slob W. A comparison of ratio distributions based on the NOAEL and the benchmark approach for subchronic-to-chronic extrapolation. Toxicol Sci. 2005;85(2):1033–1040. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun JM, Hauser R. Bisphenol A and children’s health. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2011;23(2):233–239. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3283445675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calafat AM, Kuklenyik Z, Reidy JA, Caudill SP, Ekong J, Needham LL.2005Urinary concentrations of bisphenol A and 4-nonylphenol in a human reference population. Environ Health Perspect 113391–395.; 10.1289/ehp.7534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calafat AM, Weuve J, Ye X, Jia LT, Hu H, Ringer S, et al. 2009Exposure to bisphenol A and other phenols in neonatal intensive care unit premature infants. Environ Health Perspect 117639–644.; 10.1289/ehp.0800265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calafat AM, Ye X, Wong LY, Reidy JA, Needham LL.2008Exposure of the U.S. population to bisphenol A and 4-tertiary-octylphenol: 2003–2004. Environ Health Perspect 11639–44.; 10.1289/ehp.10753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapin RE, Adams J, Boekelheide K, Gray LE, Jr, Hayward SW, Lees PS, et al. NTP-CERHR expert panel report on the reproductive and developmental toxicity of bisphenol A. Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol. 2008;83(3):157–395. doi: 10.1002/bdrb.20147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Bourguignon JP, Giudice LC, Hauser R, Prins GS, Soto AM, et al. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: an Endocrine Society scientific statement. Endocr Rev. 2009;30(4):293–342. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis AM, Kulisz E, Mathison HJ. Cardiac electrophysiological variables in blood-perfused and buffer-perfused, isolated, working rabbit heart. Am J Physiol. 1996;271(2 pt 2):H784–H789. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.2.H784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillum N, Karabekian Z, Swift LM, Brown RP, Kay MW, Sarvazyan N. Clinically relevant concentrations of di (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) uncouple cardiac syncytium. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2009;236(1):25–38. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant AO. Cardiac ion channels. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2(2):185–194. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.108.789081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X, Kobzik L, Zhao YY, Opel DJ, Liu WD, Kelly RA, et al. Nitric oxide regulation of atrioventricular node excitability. Can J Cardiol. 1997;13(12):1191–1201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancox JC, Mitcheson JS. Ion channel and exchange currents in single myocytes isolated from the rabbit atrioventricular node. Can J Cardiol. 1997;13(12):1175–1182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalife J, Delmar M, Anumonwo J, Berenfeld O, Kalifa J. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009. Basic Cardiac Electrophysiology for the Clinician. 2nd ed. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C, Poole-Wilson PA, Sarrel PM, Mochizuki S, Collins P, MacLeod KT. Effect of 17β-oestradiol on contraction, Ca2+ current and intracellular free Ca2+ in guinea-pig isolated cardiac myocytes. Br J Pharmacol. 1992;106(3):739–745. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14403.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaddar N, Bendridi N, Harthe C, de Ravel MR, Bienvenu AL, Cuilleron CY, et al. Development of a radioimmunoassay for the measurement of bisphenol A in biological samples. Anal Chim Acta. 2009;645(1–2):1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2009.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai C, Konishi T, Matsuyama E, Okazaki H. Comparative effects of three calcium antagonists, diltiazem, verapamil and nifedipine, on the sinoatrial and atrioventricular nodes. experimental and clinical studies. Circulation. 1981;63(5):1035–1042. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.63.5.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay MW, Walcott GP, Gladden JD, Melnick SB, Rogers JM. Lifetimes of epicardial rotors in panoramic optical maps of fibrillating swine ventricles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291(4):H1935–H1941. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00276.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleber AG, Rudy Y. Basic mechanisms of cardiac impulse propagation and associated arrhythmias. Physiol Rev. 2004;84(2):431–88. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00025.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurokawa J, Tamagawa M, Harada N, Honda S, Bai CX, Nakaya H, et al. Acute effects of oestrogen on the guinea pig and human IKr channels and drug-induced prolongation of cardiac repolarization. J Physiol. 2008;586(pt 12):2961–2973. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.150367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang IA, Galloway TS, Scarlett A, Henley WE, Depledge M, Wallace RB, et al. Association of urinary bisphenol A concentration with medical disorders and laboratory abnormalities in adults. JAMA. 2008;300(11):1303–1310. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.11.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laughner JI, Ng FS, Sulkin MS, Arthur RM, Efimov IR. Processing and analysis of cardiac optical mapping data obtained with potentiometric dyes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;303(7):H753–H765. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00404.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YJ, Ryu HY, Kim HK, Min CS, Lee JH, Kim E, et al. Maternal and fetal exposure to bisphenol A in Korea. Reprod Toxicol. 2008;25(4):413–419. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2008.05.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liew R, Stagg MA, MacLeod KT, Collins P. Raloxifene acutely suppresses ventricular myocyte contractility through inhibition of the L-type calcium current. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;142(1):89–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lind PM, Lind L. Circulating levels of bisphenol A and phthalates are related to carotid atherosclerosis in the elderly. Atherosclerosis. 2011;218(1):207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melzer D, Osborne NJ, Henley WE, Cipelli R, Young A, Money C, et al. Urinary bisphenol A concentration and risk of future coronary artery disease in apparently healthy men and women. Circulation. 2012;125(12):1482–1490. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.069153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melzer D, Rice NE, Lewis C, Henley WE, Galloway TS.2010Association of urinary bisphenol A concentration with heart disease: evidence from NHANES 2003/06. PLoS One 51e8673; 10.1371/journal.pone.0008673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercader M, Swift L, Sood S, Asfour H, Kay M, Sarvazyan N. Use of endogenous NADH fluorescence for real-time in situ visualization of epicardial radiofrequency ablation lesions and gaps. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302(10):H2131–H2138. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01141.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer R, Linz KW, Surges R, Meinardus S, Vees J, Hoffmann A, et al. Rapid modulation of L-type calcium current by acutely applied oestrogens in isolated cardiac myocytes from human, guinea-pig and rat. Exp Physiol. 1998;83(3):305–321. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1998.sp004115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima T, Iwasawa K, Oonuma H, Morita T, Goto A, Wang Y, et al. Antiarrhythmic effect and its underlying ionic mechanism of 17β-estradiol in cardiac myocytes. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;127(2):429–440. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly AO, Eberhardt E, Weidner C, Alzheimer C, Wallace BA, Lampert A.2012Bisphenol A binds to the local anesthetic receptor site to block the human cardiac sodium channel. PLoS One 77e41667; 10.1371/journal.pone.0041667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padmanabhan V, Siefert K, Ransom S, Johnson T, Pinkerton J, Anderson L, et al. Maternal bisphenol-A levels at delivery: a looming problem? J Perinatol. 2008;28(4):258–263. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pant J, Ranjan P, Deshpande SB. Bisphenol A decreases atrial contractility involving NO-dependent G-cyclase signaling pathway. J Appl Toxicol. 2011;31(7):698–702. doi: 10.1002/jat.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papaioannou VE, Verkerk AO, Amin AS, de Bakker JM. Intracardiac origin of heart rate variability, pacemaker funny current and their possible association with critical illness. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2013;9(1):82–96. doi: 10.2174/157340313805076359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Z, Karagueuzian HS, Garfinkel A, Weiss JN. Effects of Na+ channel and cell coupling abnormalities on vulnerability to reentry: a simulation study. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286(4):H1310–H1321. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00561.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter CA, Birnbaum LS, Farabollini F, Newbold RR, Rubin BS, Talsness CE, et al. In vivo effects of bisphenol A in laboratory rodent studies. Reprod Toxicol. 2007;24(2):199–224. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roden DM. Ionic mechanisms for prolongation of refractoriness and their proarrhythmic and antiarrhythmic correlates. Am J Cardiol. 1996;78(4A):12–16. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00448-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum DS, Jalife J. Armonk, NY: Futura Publishing Company Inc; 2001. Optical Mapping of Cardiac Excitation and Arrhythmias. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum MB, Elizari MV, Lazzari JO, Halpern MS, Nau GJ, Levi RJ. The mechanism of intermittent bundle branch block: relationship to prolonged recovery, hypopolarization and spontaneous diastolic depolarization. Chest. 1973;63(5):666–677. doi: 10.1378/chest.63.5.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saba S, Zhu W, Aronovitz MJ, Estes NA, III, Wang PJ, Mendelsohn ME, et al. Effects of estrogen on cardiac electrophysiology in female mice. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2002;13(3):276–280. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2002.00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönfelder G, Wittfoht W, Hopp H, Talsness CE, Paul M, Chahoud I. Parent bisphenol A accumulation in the human maternal–fetal–placental unit. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110:A703–A707. doi: 10.1289/ehp.110-1241091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar A, Teppala S, Sabanayagam C.2012Bisphenol A and peripheral arterial disease: results from the NHANES. Environ Health Perspect 1201297–1300.; 10.1289/ehp.1104114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin BS, Kim CH, Jun YS, Kim DH, Lee BM, Yoon CH, et al. Physiologically based pharmacokinetics of bisphenol A. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2004;67(23–24):1971–1985. doi: 10.1080/15287390490514615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift L, Martell B, Khatri V, Arutunyan A, Sarvazyan N, Kay M. Controlled regional hypoperfusion in Langendorff heart preparations. Physiol Meas. 2008;29(2):269–279. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/29/2/009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe S, Hata T, Hiraoka M. Effects of estrogen on action potential and membrane currents in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1999;277(2 pt 2):H826–H833. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.2.H826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teeguarden JG, Calafat AM, Doerge DR. Adhering to fundamental principles of biomonitoring, BPA pharmacokinetics, and mass balance is no “Flaw”. Toxicol Sci. 2012;125(1):321–325. [Letter] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg LN, Chahoud I, Heindel JJ, Padmanabhan V, Paumgartten FJ, Schoenfelder G.2010Urinary, circulating, and tissue biomonitoring studies indicate widespread exposure to bisphenol A. Environ Health Perspect 1181055–1070.; 10.1289/ehp.0901716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg LN, Hauser R, Marcus M, Olea N, Welshons WV. Human exposure to bisphenol A (BPA). Reprod Toxicol. 2007;24(2):139–177. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkel W, Colnot T, Csanady GA, Filser JG, Dekant W. Metabolism and kinetics of bisphenol A in humans at low doses following oral administration. Chem Res Toxicol. 2002;15(10):1281–1287. doi: 10.1021/tx025548t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vom Saal FS, Akingbemi BT, Belcher SM, Birnbaum LS, Crain DA, Eriksen M, et al. Chapel Hill bisphenol A expert panel consensus statement: integration of mechanisms, effects in animals and potential to impact human health at current levels of exposure. Reprod Toxicol. 2007;24(2):131–138. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vom Saal FS, Prins GS, Welshons WV. Report of very low real-world exposure to bisphenol A is unwarranted based on a lack of data and flawed assumptions. Toxicol Sci. 2012;125(1):318–320. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr273. [Letter] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Hua J, Chen M, Xia Y, Zhang Q, Zhao R, et al. High urinary bisphenol A concentrations in workers and possible laboratory abnormalities. Occup Environ Med. 2012;69(9):679–684. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2011-100529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Cao J, Hu F, Lu R, Wang J, Ding H, et al. Effects of estradiol on voltage-gated sodium channels in mouse dorsal root ganglion neurons. Brain Res. 2013;1512:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan S, Chen Y, Dong M, Song W, Belcher SM, Wang HS.2011Bisphenol A and 17β-estradiol promote arrhythmia in the female heart via alteration of calcium handling PLoS One 69e25455; 10.1371/journal.pone.0025455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.