Abstract

The MHC class I family–like Fc receptor, FcRn, is normally responsible for extending the life span of serum IgG Ab’s, but whether this molecule contributes to autoimmune pathogenesis remains speculative. To determine directly whether this function contributes to humoral autoimmune disease, we examined whether a deficiency in the FcRn heavy chain influences autoimmune arthritis in the K/BxN mouse model. FcRn deficiency conferred either partial or complete protection in the arthritogenic serum transfer and the more aggressive genetically determined K/BxN autoimmune arthritis models. The protective effects of an FcRn deficiency could be overridden with excessive amounts of pathogenic IgG Ab’s. The therapeutic saturation of FcRn by high-dose intravenous IgG (IVIg) also ameliorated arthritis, directly implicating FcRn blockade as a significant mechanism of IVIg’s anti-inflammatory action. The results suggest that FcRn is a potential therapeutic target that links the initiation and effector phases of humoral autoimmune disease.

Introduction

At the inductive phase of a humoral autoimmune response, B cells, after encounter with APCs and T cells, undergo antigen-driven proliferation and differentiation into Ab-secreting plasma cells. During the effector phase, Ab’s bind autoantigen leading to downstream events such as activation of complement, recruitment of inflammatory cells, and the engagement of stimulatory Fc receptors (1). Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is one of several autoimmune diseases with an humoral component (2). RA is the result of a productive collaboration of autoreactive T and B cells leading to synovitis, immune infiltration, and chaotic bone destruction and remodeling (3). Conventional approaches to treatment of such autoimmune diseases include nonspecific immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory agents, which are encumbered by the need to balance efficacy with unwanted side effects (4). There is a considerable need for the identification of selective therapeutic targets that link critical events in disease progression.

A key control point for the elaboration of humorally mediated autoimmune diseases would be one that couples the initiation of the Ab response from the effector phase. The Fc receptor, FcRn, is a distant member of the MHC class I protein family, which, like other class I proteins, forms an obligate heterodimer with β2-microglobulin (β2m), the common light chain for all MHC class I family proteins (5). FcRn is the Fc receptor responsible for perinatal IgG transport and for IgG homeostasis in adults (6, 7). Mice deficient in the FcRn heavy chain have a reduced half-life and reduced levels of circulating IgG (7) and albumin (8), but are otherwise immunologically normal, including their T cell and B cell response (7). Since FcRn controls serum IgG levels, a key issue is whether it impacts humoral autoimmune disease. β2m-deficient mice been used as a model for addressing this question with mixed results (refs. 9–16; D. Roopenian, unpublished observations). This is not surprising because β2m controls many immunological and nonimmunological processes, including the development and function of CD8 T cells, natural T cells, conventional NK cells (17), and iron homeostasis (18). Whether autoimmune phenotypes are dependent on FcRn thus remains to be clearly delineated.

While not considered an exact prototype for human RA, K/BxN murine model of autoimmune arthritis has a IgG Ab-mediated etiology and recapitulates much of the severe pathophysiology associated with human RA (19, 20). Disease is caused by the productive collaboration of T cells and B cells directed against glucose 6-phosphate isomerase (GPI) protein (21). Arthritis is dependent on elaboration of pathogenic anti-GPI IgG autoAb’s, which inflict joint damage through the alternative complement pathway (22) and additionally require inflammatory FcγRs (22, 23), inflammatory cytokines (24), mast cells (25), and neutrophils (26). Since these mechanisms are dependent on the availability of pathogenic Ab’s and FcRn is the receptor primarily responsible for extending IgG’s life span, we examined whether FcRn contributes to the pathogenesis of K/BxN autoimmune arthritis. Moreover, since the administration of high doses of IgG has been shown to abrogate arthritis induced by K/BxN serum (27), we investigated whether the anti-inflammatory action of intravenous IgG (IVIg) is dependent on FcRn.

Methods

Mice and genotyping.

Mice deficient in the α chain of FcRn were produced and phenotypically verified as described (7). For the serum-transfer recipients, the FcRn-null allele was backcrossed a minimum of ten generations onto C57BL/6J (B6) mice. FcRn–/– mice were identified using PCR primer pairs designed to distinguish the WT and targeted alleles (7). To produce K/BxN mice deficient in FcRn, KRN T cell receptor (TCR) transgenic mice (mostly a B10.BR [B10] background) were partially backcrossed to B6 and bred with B6-FcRn–/– mice to produce B6/B10-background KRN TCR transgene-positive FcRn+/– and FcRn–/– mice. Mice carrying this TCR transgene were genotyped by PCR (20). The resulting KRN TCR-positive B6/B10 background progeny were then intercrossed with NOD/LtJ-FcRn+/– or NOD/LtJ-FcRn–/– mice (N6-7), and KRN TCR-positive K/BxN-FcRn+/– and K/BxN-FcRn–/– littermates were identified. These mice should be heterozygous for the great majority of alleles distinguishing B6/B10 from NOD mice. In other cases, the experimental cohorts were sex and age matched and ranged from 8 to 18 weeks of age. B6-Fcγr2b–/– mice were obtained from Taconic Farms (Germantown, New York, USA). B6-FcRn+/+ and B6-FcRn–/– mice homozygous for the Fcγr2b-null allele were identified by flow-cytometric analysis of peripheral blood leukocytes, as described (28).

Serum-induced inflammatory arthritis and arthritis scoring.

Sera for transfer experiments were pooled from frankly arthritic K/BxN mice, typically older than 10 weeks of age. For induction of arthritis, animals were given a single intraperitoneal injection of 250 to 1,000 ∝l of serum (diluted to 50% in PBS). Ankles were inspected by two independent observers, blinded to the mouse genotypes and experimental manipulations. Ankles were measured axially across the joint, using calipers as described (19). Triplicate measurements for each rear ankle were averaged to produce an average ankle width for each mouse. Variation was always less than or equal to 0.2 mm. Overall arthritis scores, monitoring inflammation and redness, were scored as follows: 0, no arthritis; 1, questionable arthritis; 2, overt arthritis in one rear leg; and 3, clear arthritis in both rear legs (19).

Histology and photographs.

Histological sections were prepared from hind limbs in Bouin’s fixative, decalcified, and stained with H&E. Images of anesthetized mice were obtained using a Minolta DIMAGE7 digital camera. Except for scaling, the images were digitized and displayed without editing.

ELISA.

Anti-GPI Ig activity in a 1:50 dilution of serum was measured using rabbit GPI (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) coated at 5 ∝g/ml to capture the anti-GPI Ig. Anti-GPI Ig was measured using goat anti-mouse kappa and lambda antisera conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, Alabama, USA). Activity was reported at 405 nm after development of the colorimetric substrate pNPP (Sigma-Aldrich). Total IgG titer was measured at 1:100,000 dilution of serum captured by goat anti-mouse IgG (Sigma-Aldrich) and revealed by the same detection reagents as in the anti-GPI Ig ELISA.

Flow cytometry.

Popliteal LNs were teased into PBS-FBS buffer, and single cell suspensions of 1 ∞ 106 to 2 ∞ 106 from each LN were stained with B220-APC versus CD3e-phycoerythrin (CD3e-PE), Ly77-FITC versus B220-APC, CD4-CY3 versus CD4-CY5 versus CD8a-PE, CD11b-biotin/PECy5-streptavidin versus CD86 (PharMingen, San Diego California, USA) as described (29). For viable cell gating, propidium iodide was used as a third color. The data were acquired using a FACScalibur (Becton-Dickinson and Co., Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, USA) and analyzed using Cell-Quest software.

Gene-expression profiling.

To minimize sample preparation variation, all samples were processed in parallel. Contralateral popliteal LNs from the same mice used for flow-cytometric analysis were collected into RNAlater (Ambion Inc., Austin, Texas, USA), total RNA was purified using the RNAqueous-4PCR kit (Ambion Inc.), and DNase treated. RNA quality was confirmed by chromatography using an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100, and cDNA synthesis from 5-10 ∝l total RNA was carried out using the RETROscript kit (Ambion Inc.). The ImmunoQuantArray consists of customized oligonucleotide primers verified to specifically amplify the target gene cDNAs listed in Supplementary Figure S1 (supplemental material available at http://www.jci.org/cgi/content/full/113/9/1328/DC1) under identical thermocycler conditions (30). Quantitative expression analysis was performed essentially as described, using Applied Biosystems RealTime technology with an ABI 7900 thermocycler (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City California, USA) (30). Amplification was monitored by SYBR Green detection (Applied Biosystems Inc.). The global pattern recognition (GPR) algorithm (30) was used to identify significant changes in gene expression. GPR compares cycle threshold values and identifies genes whose expression does not differ between experimental cohorts. The unchanged genes then qualify as normalizers to rank the genes whose expression have significantly changed. This global normalization feature circumvents the ambiguities caused by reliance on a single normalizer, such as 18S rRNA. A conservative GPR cutoff score of greater than or equal to 0.400 was used. This indicates that the comparative cohorts show significant expression changes when compared with at least 40% of the qualified normalizer genes. Fold expression changes up or down are reported based on a single qualified normalizer, TATA box–binding protein (TBP) for the data reported.

IVIg therapy.

Mice were injected intraperitoneally multiple times with purified human IgG (GammaGuard; Baxter Healthcare Corp., Deerfield Illinois, USA) or HSA (Sigma-Aldrich) diluted in PBS. Twenty-five–milligram doses (1 ± 0.1 g/kg based on body weight) were administered intraperitoneally on days –1, 1, 2, and 3.

Results

FcRn-deficient mice are resistant to serum transfer-induced arthritis.

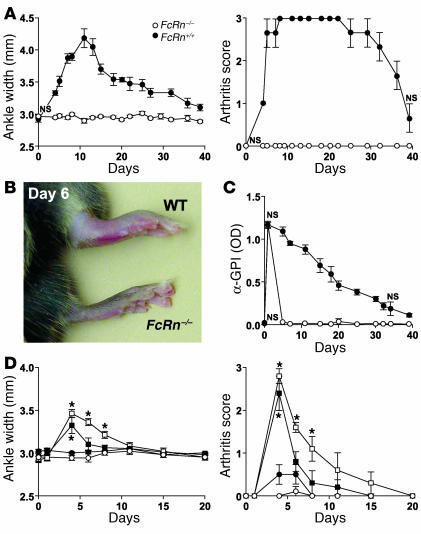

The passive transfer of serum from frankly arthritic K/BxN animals into normal mice results in a transient inflammatory arthritis in which anti-GPI Ab’s bind extracellular GPI accumulated on the joint articular surface (21, 31) and thereby initiate the aforementioned cascade of effector events. To determine whether a deficiency of FcRn impacts this transient disease, we transferred 250 ∝l of serum from arthritic K/BxN mice into B6-FcRn–/– and B6-FcRn+/+ WT mice. While WT mice underwent a typical transient arthritic episode, FcRn–/– mice were completely resistant to serum-induced arthritis (Figure 1, A–C). Moreover, FcRn–/– mice rapidly cleared arthritogenic anti-GPI Ig from the circulation following serum transfer while WT mice maintained appreciable anti-GPI levels over an extended period of time (Figure 1D). These results indicate that FcRn is responsible for maintaining concentrations of pathogenic Ab’s sufficient to promote inflammatory arthritis. The protective effect of an FcRn-deficiency could be partially overcome, however, when larger doses (500 or 1,000 ∝l) of K/BxN serum were transferred (Figure 1E). Thus, excessive concentrations of pathogenic Ab’s can override the protection conferred by an FcRn deficiency.

Figure 1.

FcRn-deficient mice are resistant to serum-transfer arthritis. Data represented as the mean ± SE. (A_C) A single injection of 250 ∝l of sera pooled from 6- to 20-week-old arthritic K/BxN animals was injected intraperitoneally into three FcRn_/_ (open circles) and three FcRn+/+ (filled circles) B6 control mice. (A) Ankle width determinations and overall arthritis scores are as described (19). All time points except day 0 were significant at P < 0.05. (B) Digital images of representative ankles of FcRn_/_ and WT mice 6 days after serum transfer. (C) Serial serum samples from A were analyzed for anti-GPI Ig by ELISA (21). Data are representative of two independent experiments. NS, not significant. All other time points were significant at P < 0.05. (D) Ankle width and arthritis scores of B6-FcRn_/_ mice (n = 4_5) injected intraperitoneally with 250 (filled circles), 500 (filled squares), or 1,000 (open squares) ∝l arthritogenic K/BxN or 1,000 ∝l normal B6 mouse serum (open circles). *Ankle width and arthritis score time points were P _ 0.004 and P < 0.01 versus B6 serum, respectively. Other time points versus B6 serum were not significant at P < 0.05.

FcRn-deficiency either retards or prevents the onset of arthritis in K/BxN mice.

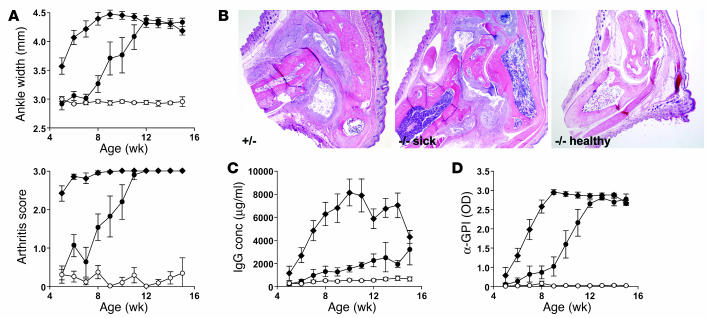

To determine whether an FcRn deficiency alters the progression of the severe arthritis that occurs with 100% penetrance in K/BxN mice, we crossed the FcRn-null mutation onto K/BxN and analyzed disease incidence and severity. While all K/BxN-FcRn+/– mice developed disease predictably by 4–5 weeks of age, K/BxN-FcRn–/– mice displayed two distinct phenotypes. Approximately half of these animals showed only intermittent ankle inflammation but failed to develop overt arthritis at least until the termination of the experiment at 15–16 weeks of age. This was confirmed by histopathological analysis (Figure 2, A and B). The other half of the animals developed disease with a highly significant, approximately 4-week delay (P < 0.0001), but ultimately were indistinguishable from their FcRn heterozygous littermates (Figure 2, A and B). The IgG titers were reduced substantially in all K/BxN-FcRn–/– mice throughout the disease course, showing the importance of FcRn in facilitating hypergammaglobulinemia consequent with humoral autoimmune disease. There was a bifurcation among the sick and healthy FcRn-deficient cohorts, however, in that IgG levels increased in the sick FcRn–/– mice but remained at predisease levels in the healthy FcRn–/– mice. Strikingly, the anti-GPI activity most closely paralleled disease onset and severity in all mouse groups, implying a cause-and-effect relationship (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

FcRn-deficient K/BxN mice are protected from genetically-induced arthritis. (A) Ankle width measurements and overall arthritis scores (mean ± SE) were performed as in Figure 1. All WT FcRn+/_ littermates (filled diamonds; n = 21; 13 males and 8 females) showed rapid disease onset. Of 21 FcRn_/_ littermates, the mice that remained healthy (open circles; n = 10; 4 males and 6 females) at approximately the 16-week duration of the experiment are plotted separately from FcRn_/_ mice (n = 11; 3 males and 8 females) that became sick (filled circles). The time of disease onset of healthy mice versus WT FcRn+/_ littermates versus FcRn_/_ sick mice was significant at P < 0.0001 by the ANOVA repeated measures test. (B) H&E sections of representative 16-week K/BxN-FcRn+/_ (+/_), sick FcRn_/_ (_/_ sick), and healthy FcRn_/_ (_/_ healthy) mice at ∞20 magnification. (C) Total serum IgG and (D) anti-GPI activity of each cohort from A was measured by ELISA at the weekly time points indicated. IgG levels of FcRn_/_ healthy versus WT FcRn+/_ mice and FcRn_/_ sick versus WT FcRn+/_ mice was significant at P _ 0.0001 by the Scheffe test. FcRn_/_ healthy versus FcRn_/_ sick (filled circles) mice did not differ significantly by the Scheffe test. Anti-GPI levels of FcRn_/_ healthy mice versus WT FcRn+/_ mice versus FcRn_/_ sick mice was significant at P _ 0.0004 by the Scheffe test. conc, concentration.

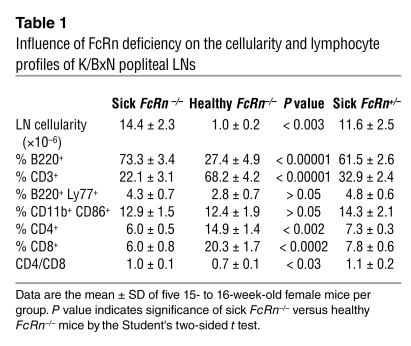

X-rays of sick and healthy cohorts revealed that by week 12 the popliteal LNs were considerably enlarged both in sick FcRn–/– and FcRn+/– animals as compared with healthy FcRn–/– animals (not shown). To gain an understanding of their cytological status, popliteal LNs from 15- to 16-week-old sick and healthy FcRn–/– animals and their sick FcRn+/– littermates were analyzed by flow cytometry. The sick mice (both FcRn–/– and FcRn+/–) showed identical profiles and a 12- to 14-fold increase in cellularity compared with the healthy FcRn–/– mice (Table 1). Accompanying this dramatic increase in cellularity was a substantial shift in the cellular context to an overabundance of B cells and a consequent reduction in T cell frequency.

Table 1.

Influence of FcRn deficiency on the cellularity and lymphocyte profiles of K/BxN popliteal LNs

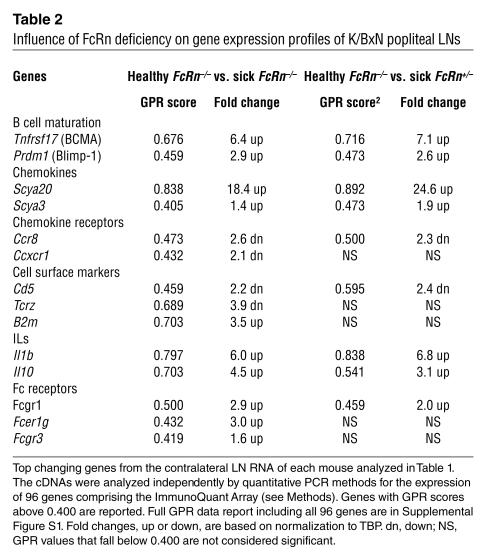

We then employed gene expression profiling to characterize the transcriptional status of the contralateral popliteal LNs from the above-mentioned groups of K/BxN mice. RNA isolated from each LN was analyzed independently for the quantitative expression of 96 genes selected to survey a spectrum of immunological processes (30) (genes listed in online supplementary material Figure S1). The data were then processed by the global pattern recognition (GPR) analytical algorithm, which computes expression changes based on biological replicate consistency and multigene normalization comparisons (30). Remarkably, similar gene expression changes were observed when either sick FcRn+/– or sick FcRn–/– mice were compared with the healthy FcRn–/– cohort, including upregulation of the B cell maturation markers (Pdrm1 and Tnfrsf17), Th2 cytokines (Il1b and Il10), chemokines (Scya20 and Scya3), and Fcγ receptors (Table 2; Figure S1, B and C). No significant gene expression changes were observed when the 15- to 16-week old sick FcRn+/– and sick FcRn–/– were compared (Figure S1C). Thus, while FcRn deficiency can rescue some mice from disease and substantially retard disease development in others, those that eventually succumb demonstrate molecular profiles indicative of substantial germinal B cell activation and differentiation, virtually indistinguishable from the WT K/BxN disease.

Table 2.

Influence of FcRn deficiency on gene expression profiles of K/BxN popliteal LNs

Therapeutic efficacy of IVIg can be explained by FcRn saturation.

Despite the fact that high-dose IVIg is used as a palliative therapy for multiple autoimmune diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus, myasthenia gravis, immune thromobocytopenic purpura (ITP), Kawasaki disease, Guillain-Barré syndrome, multiple autoimmune skin-blistering diseases, and autoimmune neurological diseases, the mechanism(s) by which IVIg ameliorates disease remain poorly understood (32–36). Therapeutic benefits of IVIg therapy in an ITP model and in the K/BxN serum transfer model have been attributed the engagement of the Fcgr2 inhibitory receptor (27, 37). FcRn’s ability to protect IgG is saturable, however, in that IgG concentration of approximately 10 mg/ml (rodents) and approximately 35 mg/ml (humans) are sufficient to functionally ablate FcRn’s ability to protect IgG (38, 39). It therefore remained possible that conventional high-dose IVIg regimes also exert their therapeutic benefits by saturating FcRn, resulting in the enhanced clearance of endogenous pathogenic IgG (40–45).

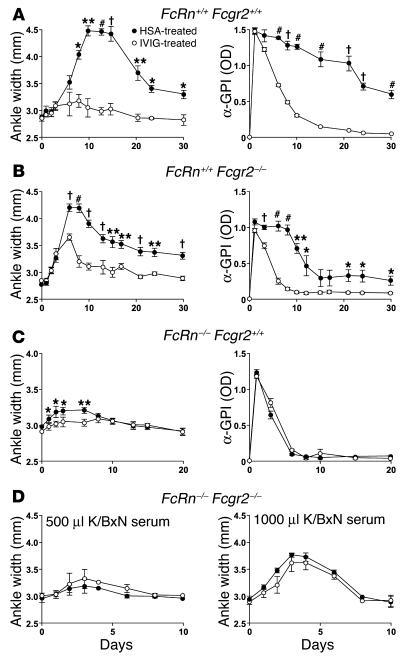

To assess and compare the requirements for FcRn and Fcgr2 in conferring a therapeutic benefit of IVIg, we first determined whether repeated 1 g/kg dosages of IVIg affected inflammation in B6 mice with WT alleles for both FcRn and Fcgr2. While mice treated with control HSA developed arthritic lesions rapidly, mice treated intraperitoneally with IVIg developed minimal disease (Figure 3A, left panel). The therapeutic benefits of IVIg were also realized in mice lacking Fcgr2 (but sufficient in FcRn), indicating that IVIg can ameliorate arthritis independently of this Fcg receptor (Figure 3B, left panel). In both cases, the fact that IVIg-treated mice also showed a precipitous decline in serum anti-GPI levels (Figure 3, A and B, right panels) was consistent with IVIg saturating FcRn. To determine the extent to which the therapeutic benefits of IVIg are realized in the absence of FcRn, mice deficient in FcRn (but sufficient in Fcgr2) were injected with a volume (1,000 ∝l) of K/BxN serum sufficient to reliably induce joint inflammation in FcRn–/– mice, and then treated with IVIg or HSA. Only a low level of inflammation occurred (Figure 3, left panel), presumably owing to the rapid clearance of anti-GPI Ab’s in the absence of FcRn (Figure 3C, right panel). IVIg was capable of abrogating this low level of inflammation in a significant manner, however (days 2, 3, and 6; P < 0.02) (Figure 3C, left panel). In contrast, IVIg treatment was unable to ameliorate the inflammation induced by 500 and 1,000 ∝l of arthritogenic serum in FcRn–/– Fcgr2–/– mice (Figure 3D). These combined data suggest that the therapeutic benefits of IVIg in this model can be fully explained by FcRn and Fcgr2. One component is dependent on FcRn but independent of Fcgr2, and a second component is dependent on Fcgr2 but independent of FcRn. Expression of both Fc receptors results in considerable synergism of the anti-inflammatory effects of IVIg.

Figure 3.

Both FcRn and Fcgr2 are required for IVIg to ameliorate arthritis. Mice were injected intraperitoneally with K/BxN serum on day 0 and treated intraperitoneally on days _1, 1, 2, and 3 with 25 mg (1 ± 1 g/kg/mouse) IVIg (open circles) or HSA (filled circles). (A) K/BxN serum (500 ∝l) was injected into B6-FcRn+/+ Fcgr2+/+ mice (n = 3). Left panel, ankle width; right panel, anti-GPI Ab’s. Representative of two independent experiments. (B) K/BxN serum (500 ∝l) injected into B6-FcRn+/+ Fcgr2_/_ mice (n = 5). Left panel, ankle width; right panel, anti-GPI Ab’s. Representative of four independent experiments using either 250 or 500 ∝l K/BxN serum. (C) K/BxN serum (500 ∝l) injected into B6-FcRn_/_ Fcgr2+/+ mice (n = 4). Left panel, ankle width; right panel, anti-GPI Ab’s. Representative of two independent experiments. (D) K/BxN serum (500 ∝l; left panel) or (1,000 ∝l; right panel) injected into FcRn_/_ Fcgr2_/_ mice (n = 3_4). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, P < 0.001, #P < 0.0001. All other time points were not significant at P < 0.05.

Discussion

FcRn is the MHC class I family molecule responsible for the unusually long half-life of IgG (6, 7). This extension results in the maintenance of much higher serum IgG concentrations compared with other Ig isotypes. As a humoral line of defense against infectious disease, this selective maintenance is beneficial in that IgG Ab’s are the major product of affinity maturation and memory B cell responses. The results described here show that this same IgG preservation function can lead to serious consequences in mice prone to develop autoimmune arthritis. By extending the life span of IgG, concentrations of pathogenic IgG Ab’s are allowed to achieve a threshold that enables a cascade of downstream effector mechanisms. In this way, FcRn couples the initiation to the effector phases of humorally mediated autoimmune disease. Blockade of FcRn, therefore, is a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of autoimmune diseases with an IgG etiology.

There are clearly autoimmune situations in which the benefits conferred by an FcRn deficiency are overcome, however. High doses (500 and 1,000 ∝l) of K/BxN serum were able to induce ankle swelling, albeit in an attenuated and transient manner, when transferred into B6-FcRn–/– mice (Figure 1D). Moreover, while half of the K/BxN-FcRn–/– mice in Figure 2 developed only sporadic ankle inflammation, never culminating in arthritis, the remaining K/BxN-FcRn–/– mice eventually overcame the protective effect of an FcRn deficiency and developed severe disease, with both cellular and phenotypes indistinguishable from the prototypic K/BxN disease. This bifurcation between K/BxN-FcRn–/– mice correlated well with their anti-GPI levels in that those that eventually developed disease had the highest anti-GPI levels and a tendency to show hypergammaglobulinemia. At present, we cannot distinguish whether the bifurcation is genetic (a consequence of residual genetic variation among the K/BxN cohorts) or epigenetic (stochastic variation in pathogenic IgG levels). The correlation of anti-GPI levels with disease onset suggests, however, that arthritis in this model is highly sensitive to a threshold concentration of these pathogenic Ab’s. When an FcRn deficiency is able to restrain pathogenic Ab’s below this threshold, disease does not occur. When the threshold is exceeded, however, these Ab’s precipitate a cascade of events that eventually results in severe disease.

Despite its increasing usage, the track record for IVIg is mixed (34) and the mechanisms by which it operates remain controversial (36, 44, 46, 47). While clinical data support the efficacy of IVIg in the treatment of certain autoimmune diseases, positive effects in the treatment of diseases such as RA and systemic lupus erythematosus are anecdotal and not supported by controlled clinical studies (33). A better understanding of how IVIg exerts its palliative effects is thus critical to its intelligent use. Recruitment of the inhibitory Fcgr2 receptor has been proposed as an explanation for the anti-inflammatory effects of Fcgr2 in both ITP and the K/BxN serum transfer models (27, 37). Our studies, which employed multiple dosages of IVIg to ensure FcRn saturation, clearly indicate that the palliative effects of IVIg can be substantially dependent on FcRn, regardless of whether the engagement of Fcgr2 is possible. When doses of IVIg are sufficient to induce the saturation of FcRn, clearance of endogenous pathogenic IgG is substantially accelerated (40–45). This acceleration reduces the availability of pathogenic IgG for downstream effector events, including those that are counteracted by Fcgr2 engagement. The benefits of IVIg acting through FcRn, however, would be realized only in patients whose diseases have a strong IgG component and whose endogenous IgG falls below levels that already have saturated FcRn. Many patients with humoral autoimmunity fall into this category. In such situations, the Fcgr2 inhibitory and FcRn saturation pathways would operate synergistically. These findings provide a more logical footing for the judicious use of IVIg.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Diane Mathis and Christophe Benoist for generously providing KRN transgenic mice, Ralph Bunte and Lia Avanessian for histological interpretations, Jason Stockwell for statistical analyses, Lori Goodwin for technical assistance, and Theodore Duffy for flow cytometry assistance. This work was supported by the Alliance for Lupus Research and NIH grant DK-056597. S. Akilesh was supported by a Fellowship from the Shelby Cullom Davis Foundation. S. Petkova was supported by NIH Postdoctoral Fellowship AR049695.

Footnotes

Shreeram Akilesh and Stefka Petkova contributed equally to this work.

Shreeram Akilesh’s present address is: Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri, USA.

Nonstandard abbreviations used: B10.BR (B10); β2-microglobulin (β2m); C57BL/6J (B6); global pattern recognition (GPR); glucose 6-phosphate isomerase (GPI); human serum albumin (HSA); immune thromobocytopenic purpura (ITP); intravenous IgG (IVIg); phycoerythrin (PE); rheumatoid arthritis (RA); T cell receptor (TCR); TATA box–binding protein (TBP).

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Takai T. Roles of Fc receptors in autoimmunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002;2:580–592. doi: 10.1038/nri856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benoist C, Mathis D. A revival of the B cell paradigm for rheumatoid arthritis pathogenesis? Arthritis Res. 2000;2:90–94. doi: 10.1186/ar73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feldmann M, Brennan FM, Maini RN. Rheumatoid arthritis. Cell. 1996;85:307–310. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81109-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee DM, Weinblatt ME. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 2001;358:903–911. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simister NE, Mostov KE. An Fc receptor structurally related to MHC class I antigens. Nature. 1989;337:184–187. doi: 10.1038/337184a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghetie V, Ward ES. Multiple roles for the major histocompatibility complex class I-related receptor FcRn. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2000;18:739–766. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roopenian DC, et al. The MHC class I-like IgG receptor (FcRn) controls perinatal IgG transport, IgG homeostasis and the fate of IgG-Fc coupled drugs. J. Immunol. 2003;170:3528–3533. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chadhury C, et al. The MHC-related Fc Receptor (FcRn) binds albumin and prolongs its lifespan. J. Exp. Med. 2003;197:315–322. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moses E, Kohn LD, Hakim F, Singer DS. Resistance of MHC class -I deficient mice to experimental systemic lupus erythematosus. Science. 1993;261:91–93. doi: 10.1126/science.8316860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christianson GJ, et al. β2 microglobulin dependence of lupus-like autoimmune syndrome of MRL-lpr mice. J. Immunol. 1996;176:4933–4939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christianson GJ, et al. β2-microglobulin-deficient mice are protected from hypergammaglobulinemia and have defective antibody responses because of increased IgG catabolism. J. Immunol. 1997;159:4781–4792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maldonado MA, Eisenberg RA, Roper E, Cohen PL, Kotzin BL. Greatly reduced lymphoproliferation in lpr mice lacking major histocompatibility complex class I. J. Exp. Med. 1995;181:641–648. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.2.641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mixter PF, Russell JQ, Durie FH, Budd RC. Decreased CD4-CD8- TCR-alpha beta + cells in lpr/lpr mice lacking β2-microglobulin. J. Immunol. 1995;154:2063–2074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohtelki T, Iwamoto M, Izui S, MacDonald HR. Reduced development of CD4-8-B220+ T cells but normal autoantibody production in mice lacking major histocompatibility complex class I molecules. Eur. J. Immunol. 1995;25:37–41. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shenoy M, Kaul R, Goluszko E, David C, Christadoss P. Effect of MHC class I and CD8 cell deficiency on experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis pathogenesis. J. Immunol. 1994;153:5330–5335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan OT, et al. Deficiency in β2-microglobulin, but not CD1, accelerates spontaneous lupus skin disease while inhibiting nephritis in MRL-Fas(lpr) mice: an example of disease regulation at the organ level. J. Immunol. 2001;167:2985–2990. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.5.2985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raulet DH. MHC class 1-deficient mice. Adv. Immunol. 1994;55:381–421. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60514-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santos M, et al. Defective iron homeostasis in beta 2-microglobulin knockout mice recapitulates hereditary hemochromatosis in man. J. Exp. Med. 1996;184:1975–1985. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Korganow AS, et al. From systemic T cell self-reactivity to organ-specific autoimmune disease via immunoglobulins. Immunity. 1999;10:451–461. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80045-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kouskoff V, et al. Organ-specific disease provoked by systemic autoimmunity. Cell. 1996;87:811–822. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81989-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsumoto I, et al. How antibodies to a ubiquitous cytoplasmic enzyme may provoke joint-specific autoimmune disease. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3:360–365. doi: 10.1038/ni772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ji H, et al. Arthritis critically dependent on innate immune system players. Immunity. 2002;16:157–168. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00275-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Corr M, Crain B. The role of FcgammaR signaling in the K/B x N serum transfer model of arthritis. J. Immunol. 2002;169:6604–6609. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.11.6604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ji H, et al. Critical roles for interleukin 1 and tumor necrosis factor α in antibody-induced arthritis. J. Exp. Med. 2002;196:77–85. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee DM, et al. Mast cells: a cellular link between autoantibodies and inflammatory arthritis. Science. 2002;297:1689–1692. doi: 10.1126/science.1073176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wipke BT, Allen PM. Essential role of neutrophils in the initiation and progression of a murine model of rheumatoid arthritis. J. Immunol. 2001;167:1601–1608. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bruhns P, Samuelsson A, Pollard JW, Ravetch JV. Colony-stimulating factor-1-dependent macrophages are responsible for IVIG protection in antibody-induced autoimmune disease. Immunity. 2003;18:573–581. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takai T, Ono M, Hikida M, Ohmori H, Ravetch JV. Augmented humoral and anaphylactic responses in Fc gamma RII-deficient mice. Nature. 1996;379:346–349. doi: 10.1038/379346a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi EY, et al. Real-time T cell profiling identifies H60 as a major minor histocompatibility antigen in murine graft-vs-host disease. Blood. 2002;100:4259–4264. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akilesh S, Shaffer DJ, Roopenian DC. Customized molecular phenotyping by quantitative gene expression and pattern recognition analysis. Genome Res. 2003;13:1719–1727. doi: 10.1101/gr.533003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wipke BT, Wang Z, Kim J, McCarthy TJ, Allen PM. Dynamic visualization of a joint-specific autoimmune response through positron emission tomography. Nat. Immunol. 2002;18:18. doi: 10.1038/ni775. (Abstr.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dalakas MC. Mechanism of action of intravenous immunoglobulin and therapeutic considerations in the treatment of autoimmune neurologic diseases. Neurology. 1998;51(Suppl.):S2–S8. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.6_suppl_5.s2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pyne D, Ehrenstein M, Morris V. The therapeutic uses of intravenous immunoglobulins in autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2002;41:367–374. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/41.4.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Lederman HM. Supply, use, and abuse of intravenous immunoglobulin. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 1999;11:533–539. doi: 10.1097/00008480-199912000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hansen RJ, Balthasar JP. IVIG effects on antiplatelet antibody levels and on platelet opsonization in ITP. Blood. 2003;101:1659. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crow AR, Song S, Semple JW, Freedman J, Lazarus AH. IVIG induces dose dependent amelioration of ITP in rodent models. Blood. 2003;101:1658–1659. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Samuelsson A, Towers TL, Ravetch JV. Anti-inflammatory activity of IVIG mediated through the inhibitory Fc receptor. Science. 2001;291:484–486. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5503.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Junghans RP. IgG biosynthesis: no “immunoregulatory feedback”. Blood. 1997;90:3815–3818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Waldmann TA, Jones EA. The role of cell-surface receptors in the transport and catabolism of immunoglobulins. Ciba Found. Symp. 1972;9:5–23. doi: 10.1002/9780470719923.ch2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Masson PL. Elimination of infectious antigens and increase of IgG catabolism as possible modes of action of IVIg. J. Autoimmun. 1993;6:683–689. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1993.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu Z, Lennon VA. Mechanism of intravenous immune globulin therapy in antibody-mediated autoimmune diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999;340:227–228. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901213400311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pierangeli SS, Espinola R, Liu X, Harris EN, Salmon JE. Identification of an Fc gamma receptor-independent mechanism by which intravenous immunoglobulin ameliorates antiphospholipid antibody-induced thrombogenic phenotype. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:876–883. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200104)44:4<876::AID-ANR144>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bleeker WK, Teeling JL, Hack CE. Accelerated autoantibody clearance by intravenous immunoglobulin therapy: studies in experimental models to determine the magnitude and time course of the effect. Blood. 2001;98:3136–3142. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.10.3136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hansen RJ, Balthasar JP. Intravenous immunoglobulin mediates an increase in anti-platelet antibody clearance via the FcRn receptor. Thromb. Haemost. 2002;88:898–899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hansen RJ, Balthasar JP. Effects of intravenous immunoglobulin on platelet count and antiplatelet antibody disposition in a rat model of immune thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2002;100:2087–2093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mouthon L, et al. Mechanisms of action of intravenous immune globulin in immune-mediated diseases. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1996;104(Suppl. 1):3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kekow J, Reinhold D, Pap T, Ansorge S. Intravenous immunoglobulins and transforming growth factor beta. Lancet. 1998;351:184–185. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)78212-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.