Abstract

Pre–B cell colony-enhancing factor (PBEF) is a highly conserved 52-kDa protein, originally identified as a growth factor for early stage B cells. We show here that PBEF is also upregulated in neutrophils by IL-1β and functions as a novel inhibitor of apoptosis in response to a variety of inflammatory stimuli. Induction of PBEF occurs 5–10 hours after LPS exposure. Prevention of PBEF translation with an antisense oligonucleotide completely abrogates the inhibitory effects of LPS, IL-1, GM-CSF, IL-8, and TNF-α on neutrophil apoptosis. Immunoreactive PBEF is detectable in culture supernatants from LPS-stimulated neutrophils, and a recombinant PBEF fusion protein inhibits neutrophil apoptosis. PBEF is also expressed in neutrophils from critically ill patients with sepsis in whom rates of apoptosis are profoundly delayed. Expression occurs at higher levels than those seen in experimental inflammation, and a PBEF antisense oligonucleotide significantly restores the normal kinetics of apoptosis in septic polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Inhibition of apoptosis by PBEF is associated with reduced activity of caspases-8 and -3, but not caspase-9. These data identify PBEF as a novel inflammatory cytokine that plays a requisite role in the delayed neutrophil apoptosis of clinical and experimental sepsis.

Introduction

Sepsis is a complex clinical syndrome that results from an activated systemic host inflammatory response to infection (1, 2). It affects almost 800,000 North Americans each year, resulting in more than 200,000 deaths annually (3). Sepsis is the leading cause of morbidity for patients admitted to a contemporary intensive care unit (ICU) through the development of a syndrome of disseminated organ injury known as the multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (4). Although sepsis can develop in neutropenic patients (5), it is much more commonly associated with an exaggerated innate immune response that includes neutrophilia, endothelial activation, microvascular thrombosis, and evidence of intravascular neutrophil activation (6, 7). Activated neutrophils have been implicated in the increased microvascular permeability of systemic inflammation (8) and in the pathogenesis of inflammatory injury to the lung (9), liver (10), gastrointestinal tract (11), and kidney (12).

As nonspecific cellular effectors of the innate response to infection and tissue injury, neutrophils occupy a key role in normal immune homeostasis. Their deficiency predisposes one to infection (5); however, their excess can also produce inflammatory tissue damage (13, 14). Neutrophil numbers and activity are tightly regulated by a constitutive apoptotic program that limits the lifespan of the resting neutrophil to 5–6 hours in vivo and 24–36 hours in vitro (15). Neutrophil apoptosis is exquisitely sensitive to modulation by stimuli from the inflammatory microenvironment, including microbial factors such as LPS, formylated bacterial peptides, and host-derived inflammatory cytokines such as TNF and G-CSF (16). Even more profound suppression of apoptosis is apparent in neutrophils isolated from the systemic circulation (17, 18) or lungs (19) of critically ill septic patients, suggesting that the prolonged survival of activated neutrophils contributes to the inflammatory injury of sepsis.

The inhibition of neutrophil apoptosis by LPS or inflammatory cytokines is an active process that requires new gene expression and protein synthesis and is dependent on the release of IL-1 from the neutrophil (20). We analyzed the differential pattern of gene expression in neutrophils stimulated by IL-1β using suppressive subtractive hybridization (21). Among the transcripts upregulated by IL-1β was that for pre–B cell colony-enhancing factor (PBEF). The PBEF gene, located on the long arm of chromosome 7 between 7q22.1 and 7q31.33, encodes a 52-kDa cytokine-like molecule, originally isolated as a secreted factor that synergizes with IL-7 and stem cell factor to promote the growth of B cell precursors (22). A highly conserved protein, PBEF has been identified in fish (23), invertebrate sponges (24), and bacteria (25) and has been postulated to play a role in innate immunity (24). The biologic activity of PBEF is poorly understood. It is secreted by activated lymphocytes (22), and recombinant PBEF stimulates the expression of IL-6 and IL-8 in amniotic cells (26). Its bacterial homolog is a nicotinamide phosphoribosyl transferase (25); however, an activity recently demonstrated for murine PBEF (27), and its predominantly nuclear location and increased cytoplasmic expression in proliferating cells suggest a role in cell cycle regulation (28).

We show here that PBEF is also synthesized and released by neutrophils in response to inflammatory stimuli and that it plays a requisite role in the inhibition of apoptosis that results from diverse inflammatory stimuli. In addition, PBEF is expressed at high levels in neutrophils harvested from septic critically ill patients and contributes to prolonged neutrophil survival in clinical sepsis.

Results

IL-1 modulates neutrophil gene expression.

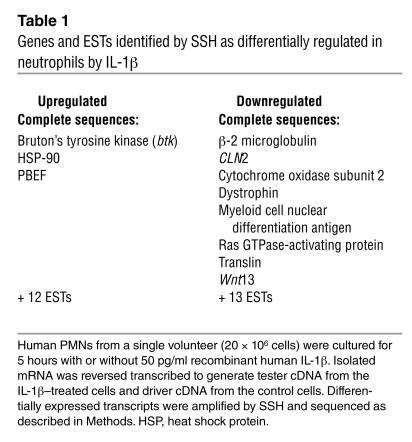

We have previously shown that the antiapoptotic activity of a microbial product, LPS, and a host-derived cytokine, GM-CSF, on the neutrophil were mediated through the synthesis and caspase-1–dependent processing of IL-1β (20). We used suppressive subtractive hybridization (SSH) to detect transcripts that were either upregulated or downregulated in the neutrophil by IL-1β. Following incubation with recombinant IL-1β (50 pg/ml), neutrophils from a single healthy donor showed de novo expression of transcripts for three known genes and inhibition of the transcription of a further eight genes (Table 1). In addition, expressed sequence tags (ESTs) for eight unknown genes were found to be upregulated, while 13 unknown genes were found to be downregulated by IL-1β. Among the transcripts found to be induced by IL-1β was that for PBEF (22).

Table 1.

Genes and ESTs identified by SSH as differentially regulated in neutrophils by IL-1β

PBEF is induced in neutrophils and monocytes in response to inflammatory stimuli.

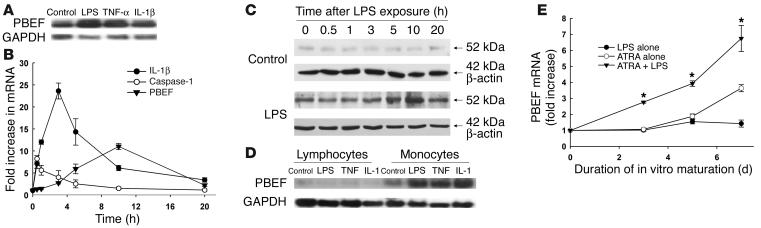

Constitutive neutrophil apoptosis can be inhibited by multiple inflammatory mediators of microbial or host origin, including LPS, IL-1β, TNF-α, GM-CSF, and IL-8 (16, 29). Neutrophils from healthy volunteers expressed PBEF mRNA transcripts in response to LPS (1 ∝g/ml), IL-1β (100 pg/ml), or TNF-α (40 ng/ml) (Figure 1A). Conversely, PBEF mRNA expression was reduced following treatment of polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) with an agonistic anti-CD95 Ab or following phagocytosis of heat-killed Candida albicans, two stimuli that accelerate neutrophil apoptosis (30) (data not shown). Evaluation by real-time PCR of the time course of gene expression showed early upregulation of transcripts for IL-1β and its processing enzyme, caspase-1, and later expression of PBEF, reaching maximal levels at 10 hours after LPS stimulation (Figure 1B). Protein expression as evaluated by Western blot analysis mirrored the temporal changes in mRNA expression (Figure 1C). PBEF transcripts could also be detected in peripheral blood monocytes following LPS stimulation, but not in lymphocytes (Figure 1D), as well as in promyelocytic HL-60 cells that were induced to undergo neutrophilic differentiation by incubation with all-trans retinoic acid (Figure 1E).

Figure 1.

PBEF is expressed in neutrophils and monocytes exposed to inflammatory stimuli. (A) Neutrophils expressed mRNA transcripts for PBEF in response to LPS, TNF-α, and IL-1β, stimuli that inhibit neutrophil apoptosis. (B) LPS (1 ∝g/ml) induced transcripts for caspase-1 (open circles), reaching maximal concentrations by 1 hour, IL-1β (filled circles) peaking at 3 hours, and PBEF (filled triangles) reaching maximal levels at 10 hours. The mRNA expression was quantified by real-time PCR; data are expressed as fold increase over basal levels of expression for each mRNA species; n = 4. (C) Western blot analysis showed low-level expression of PBEF in control cells, while LPS (1 ∝g/ml) increased PBEF protein, with maximum expression evident 10 hours after exposure. Blots were reprobed with β-actin to confirm equal loading; data are representative of three separate experiments. (D) PBEF mRNA transcripts were also expressed in peripheral blood monocytes, but not lymphocytes, in response to LPS, TNF, and IL-1. Blots are representative of three separate experiments; corresponding mRNA for GAPDH is shown to evaluate sample loading. (E) HL-60 cells induced to granulocytic differentiation by 1 ∝M all-trans retinoic acid showed increased message for PBEF, and transcript levels evaluated by real-time PCR were further increased by exposure of differentiated HL-60 cells to LPS (1 ∝g/ml) added to cultures with all-trans retinoic acid at day 0. Data are normalized to levels of PBEF transcripts in undifferentiated HL-60 cells; *P < 0.05 versus all-trans retinoic acid alone; n = 4. ATRA, all-trans retinoic acid.

Inhibition of neutrophil apoptosis by inflammatory stimuli is PBEF dependent.

Translation of PBEF mRNA was blocked using a phosphorothioate-modified antisense oligonucleotide (31). Following 21 hours of in vitro culture with LPS (1 ∝g/ml), IL-1β (100 pg/ml), GM-CSF (20 ng/ml), IL-8 (250 ng/ml), or TNF-α (40 ng/ml), rates of neutrophil apoptosis were significantly reduced; the inhibitory influence of each could be completely abrogated by blocking the translation of PBEF with an antisense oligonucleotide; PBEF sense and nonsense controls were without activity (Figure 2A). The antisense oligonucleotide, but not its sense control, significantly reduced PBEF protein expression in response to LPS exposure (Figure 2B). Apoptosis was also detected as the exteriorization of membrane phosphatidylserine using FITC-labeled annexin V. As shown in Figure 2C, the PBEF antisense oligonucleotide also prevented the LPS-induced inhibition of annexin V binding to exteriorized phosphatidylserine.

Figure 2.

Prevention of PBEF translation with an antisense oligonucleotide blocks inhibition of apoptosis in response to inflammatory stimuli. (A) Neutrophil apoptosis, assessed as the nuclear uptake of propidium iodide, was significantly inhibited by coincubation with LPS (1 ∝g/ml), IL-1β (100 pg/ml), GM-CSF (20 ng/ml), IL-8 (250 ng/ml), or TNF-α (40 ng/ml). *P < 0.05 compared with control rates. Prevention of PBEF translation using an antisense oligonucleotide prevented this inhibitory effect; the corresponding sense or scrambled nonsense controls were without effect. Data are mean ± SD of six separate studies. (B) Antisense treatment of resting or LPS-stimulated (1 ∝g/ml) neutrophils inhibited the translation of PBEF as detected by Western blot analysis. Blot is representative of three separate studies. (C) Both LPS (1 ∝g/ml) and recombinant PBEF (50 ng/ml) inhibited phosphatidylserine exteriorization detected by the binding of FITC-labeled annexin V, an effect that was specifically blocked when neutrophils were pretreated with PBEF antisense; n = 4, *P < 0.05. rPBEF, recombinant PBEF.

Recombinant PBEF protein inhibits apoptosis of unstimulated neutrophils.

Several lines of investigation suggested that the antiapoptotic activity of PBEF depends on its secretion from the neutrophil. While conditioned medium from LPS-stimulated neutrophils alone or previously incubated with a sense oligonucleotide control inhibited the constitutive apoptosis of control neutrophils, conditioned medium from antisense-treated LPS-stimulated cells had no effect (Figure 3A), indicating that LPS induces a secreted, PBEF-dependent suppressive activity in neutrophils. When a PBEF/c-myc construct was transfected into CHO cells, the resulting protein could be demonstrated by immunoprecipitation from both CHO cell lysates and the supernatant of cultured CHO cells (Figure 3B); successful transfection was confirmed by immunofluorescence microscopy using a FITC-labeled anti–c-myc Ab (data not shown). Supernatants from CHO cell PBEF transfectants inhibited the apoptosis of resting neutrophils; supernatants from cells transfected with plasmid containing c-myc alone were without effect (Figure 3C). Similarly, a PBEF/glutathione S-transferase (PBEF/GST) fusion protein expressed in Escherichia coli induced dose-dependent inhibition of the apoptosis of control neutrophils (Figure 3D). GST protein alone was without effect (data not shown). Because the fusion protein was raised in E. coli, the potential confounding effects of contaminating endotoxin were evaluated. Using the chromogenic limulus amebocyte lysate assay, endotoxin levels were elevated to 6.0 endotoxin units (EU) (approximately 600 pg/ml) in crude fractions; Triton-X114 treatment as described in Methods reduced endotoxin contamination to 0.05 EU (approximately 5 pg/ml). Moreover, addition of polymyxin B to crude preparations of PBEF/GST at a dose of 10 ∝g/ml — a dose that preliminary studies showed could completely block the antiapoptotic activity of 1 ∝g/ml LPS — failed to block the antiapoptotic activity of PBEF (Figure 3D). Finally, the antiapoptotic effects of the PBEF/GST fusion protein could be blocked by the addition of polyclonal anti-PBEF Ab to the culture medium, although the Ab failed to inhibit the antiapoptotic effects of LPS (Figure 3E). Taken together, the results of these studies indicate that PBEF is a secreted protein and that its antiapoptotic activity arises, at least in part, from its role as a secreted cytokine.

Figure 3.

PBEF exerts its antiapoptotic activity as a secreted factor. (A) Naive neutrophils were incubated for 21 hours with conditioned medium from resting or LPS-stimulated neutrophils, with or without prior transfection with PBEF antisense oligonucleotide or the sense control. Conditioned medium from resting neutrophils did not alter apoptotic rates in comparison with untreated controls (white bar). Conditioned medium from neutrophils incubated with LPS inhibited the apoptosis of naive neutrophils (*P < 0.05 versus control cell supernatants). Pretreatment with an antisense PBEF oligonucleotide, but not with the sense control, blocked this inhibitory activity (#P < 0.05 versus sense control). Data are means ± SD of n = 6 experiments. (B) Culture supernatants or whole cell lysates from CHO cells transfected with a pCDNA3.1 vector carrying a PBEF/c-myc construct were immunoprecipitated with anti_c-myc. PBEF could be detected by Western blot analysis with anti-PBEF Ab in both lysates and supernatants from transfected cells, but not in those from nontransfected cells or cells transfected with plasmid containing c-myc alone. (C) Supernatants from transfected CHO cells suppressed the apoptosis of resting neutrophils as measured by propidium iodide uptake, whereas supernatants from vector-treated controls were without effect; *P < 0.05 versus control or empty vector, n = 4. (D) A recombinant PBEF/GST fusion protein added to cultures of control neutrophils induced dose-dependent inhibition of apoptosis; polymyxin B (10 ∝g/ml) was added to cultures to neutralize any contaminating LPS. Recombinant GST alone was without effect (data not shown). Apoptosis was measured by propidium iodide uptake at 21 hours; results are means ± SD of n = 3 studies.

Because PBEF has been described as having activity both as a secreted cytokine (22, 26) and as an intracellular phosphoribosyl transferase (27), and because it has been proposed that delayed neutrophil apoptosis in inflammation is a consequence of secreted mediators from contaminating monocytes (32), we sought to better characterize the mechanism of PBEF action on neutrophils. The antiapoptotic effects of PBEF/GST fusion protein added to cultures of naive neutrophils could be blocked by anti-PBEF Ab; however, the Ab did not inhibit the antiapoptotic effect of LPS (Figure 4A). On the other hand, preincubation of conditioned medium from LPS-stimulated PMN cultures with anti-PBEF significantly attenuated its suppressive activity (Figure 4B), suggesting that the affinity of the polyclonal Ab is low. Finally, while recombinant PBEF/GST fusion protein inhibited the apoptosis of control neutrophils, it was not inhibitory when expression of endogenous PBEF was blocked by antisense pretreatment (Figure 4C). Taken together, these data suggest that while secreted PBEF is necessary for the inhibition of neutrophil apoptosis, suppressive activity requires the presence of endogenous PBEF.

Figure 4.

Both extracellular and endogenous PBEF contribute to the inhibition of neutrophil apoptosis. (A) Polyclonal anti-PBEF Ab (1:500) added to the culture medium neutralized the antiapoptotic effects of recombinant PBEF/GST, but in contrast to the effects of inhibition of PBEF translation with antisense, oligonucleotide did not block the antiapoptotic effects of LPS; n = 4, *P < 0.05 versus controls. (B) Anti-PBEF Ab (1:500), however, significantly blocked the inhibitory activity of conditioned medium (CM) from LPS-treated neutrophils. Mean ± SD, n = 3, *P < 0.05 versus controls, **P < 0.05 versus conditioned medium alone (no anti-PBEF Ab added). (C) While antisense pretreatment prevented the inhibitory effects of LPS exposure, addition of inhibitory concentrations of rPBEF/GST was unable to restore the inhibitory effect, suggesting that inhibition of apoptosis requires both extracellular and intracellular or endogenous PBEF; n = 3.

PBEF inhibits apoptosis by reducing the enzymatic activities of caspase-8 and caspase-3.

Apoptosis is effected through an intracellular cascade of cysteine proteases known as caspases (33, 34). Apoptosis can be initiated by signals delivered at the cell membrane through receptors of the Fas family, leading to cleavage and activation of caspase-8 (35) or by stimuli that increase mitochondrial permeability, resulting in translocation of cytochrome c to the cytosol and activation of caspase-9 (36). Both pathways result in catalytic cleavage and activation of caspase-3, the final effector caspase whose targets include the DNA nuclease responsible for the characteristic nuclear degradation of apoptosis (37).

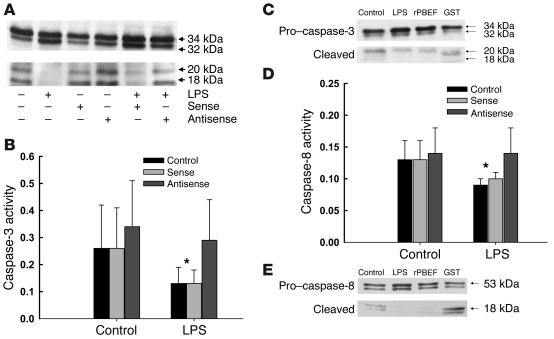

LPS pretreatment resulted in reduced activation of caspase-3, reflected in reduced levels of the active cleaved product by Western blot analysis (Figure 5A) and reduced in vitro enzymatic activity (Figure 5B). Pretreatment of neutrophils with the antisense oligonucleotide abrogated this effect, whereas the sense control was without biologic activity. Recombinant PBEF/GST, but not GST alone, also blocked the cleavage of caspase-3 (Figure 5C). LPS further reduced the activity of caspase-8, an effect that was similarly reversed by the antisense, but not the sense, oligonucleotide (Figure 5D), and PBEF/GST, but not GST alone, inhibited the cleavage of caspase-8 (Figure 5E), suggesting that the target of PBEF activity may be early membrane-linked events associated with caspase-8 activation. The antisense had no effect on the activity of the mitochondrial-dependent caspase, caspase-9 (data not shown).

Figure 5.

PBEF inhibits the cleavage and catalytic activity of caspase-3 and blocks the activity of caspase-8. (A) Caspase-3 is cleaved to yield active 18- to 20-kDa fragments in constitutively apoptotic neutrophils; LPS inhibits the activational cleavage of this effector caspase, as evaluated by Western blot analysis following 6 hours of in vitro culture. PBEF antisense prevented the inhibitory effects of LPS, while the sense control did not. Blot shown is representative of three separate studies. (B) Caspase-3 activity, measured colorimetrically in arbitrary units as the cleavage of the tetrapeptide Ac-DEVD-pNA was also reduced in neutrophils following exposure to LPS; PBEF antisense, but not the sense control, prevented this reduction in caspase-3 activity. Results are means ± SD of six separate studies; *P < 0.05 versus control levels or activity levels in neutrophils treated with PBEF antisense. (C) Cleavage of pro_caspase-3 to active caspase-3 (20 kDa) was reduced in neutrophils incubated with LPS (1 μg/ml) or rPBEF (50 ng/ml); Western blot is representative of 3 separate experiments. (D) Caspase-8 activity, measured colorimetrically in arbitrary units as the cleavage of the caspase-8 tetrapeptide target Ac-IETD-pNA was reduced by exposure to LPS and restored by pretreatment of neutrophils with PBEF antisense. Results are means ± SD of six separate studies; *P < 0.05, control or sense-treated cells versus antisense-treated neutrophils or neutrophils cultured in the absence of LPS. (E) Cleavage of pro_caspase-8 (53 kDa) to its active form (18 kDa) was also inhibited by exposure of neutrophils to LPS or rPBEF; Western blot is representative of 3 separate experiments.

PBEF is expressed in neutrophils from patients with sepsis and contributes to inhibition of apoptosis.

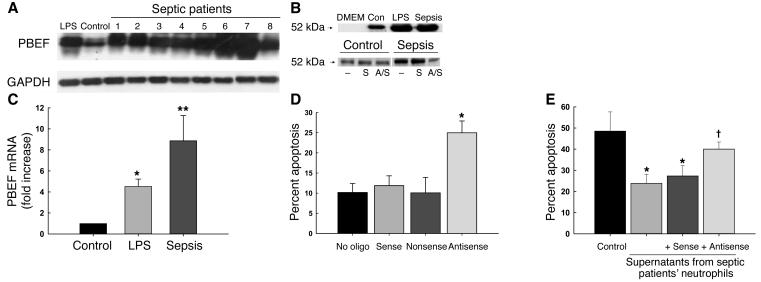

We evaluated the expression of PBEF in neutrophils harvested from 16 critically ill septic patients in the ICU. Patients were acutely ill, as reflected in a mean APACHE II score (38) of 21.1 ± 2.4 and showed evidence of the multiple organ dysfunction (MOD) syndrome, with a mean MOD score (39) of 6.6 ± 1.0; mortality at 28 days was 25% (four patients).

Neutrophils from septic critically ill patients showed marked expression of PBEF message (Figure 6A). As quantified by real-time PCR, PBEF expression was significantly greater in neutrophils from septic patients than in resting neutrophils or LPS-stimulated neutrophils from healthy volunteers (Figure 6B). Supernatants from in vitro cultures of septic patient neutrophils contained immunoreactive PBEF, and antisense treatment of these cells resulted in reduced PBEF release (Figure 6C). Moreover, incubation of patient neutrophils with a PBEF antisense oligonucleotide resulted in a greater than twofold increase in rates of apoptosis; the sense and nonsense controls were without activity (Figure 6D). Finally, antisense treatment also blocked the suppressive activity of supernatants from septic patient neutrophils (Figure 6E), and addition of anti-PBEF to the supernatant of PMN cultures from a single septic patient almost completely eliminated the inhibitory activity of the supernatant on control neutrophils (data not shown). Taken together, these data implicate secreted PBEF in the inhibition of apoptosis that occurs in patients with sepsis.

Figure 6.

PBEF is expressed and is biologically active in neutrophils harvested from critically ill septic patients. (A) PBEF mRNA in neutrophils from eight critically ill septic patients was expressed at higher levels than in control (Con) or LPS-stimulated neutrophils. Blots were reprobed with GAPDH to confirm comparability of loading. (B) Expression of PBEF mRNA transcripts in septic and LPS-treated neutrophils was evaluated by real-time PCR, normalizing expression to that for GAPDH. Expression was induced by LPS (*P < 0.05 versus unstimulated cells) and even more in septic neutrophils (**P < 0.05 versus both LPS-stimulated cells and unstimulated cells). (C) Immunoreactive PBEF was detectable by Western blot in supernatants from LPS-treated and septic neutrophils following 21 hours of in vitro culture in serum-free medium; antisense pretreatment blocked the secretion of PBEF. DMEM denotes medium only; studies were repeated three times, and a representative blot is shown. S, sense; A/S, antisense. (D) Neutrophils from 16 septic critically ill patients were incubated for 5 hours with PBEF antisense or the sense or nonsense controls, and apoptosis was evaluated 21 hours later. Antisense treated cells, but not controls, showed increased rates of apoptosis (*P = 0.002 versus no oligonucleotide [no oligo]; ANOVA). (E) Supernatants from control PMN had minimal effects on the apoptosis of resting PMN (black bar). In contrast, supernatants from septic PMN or septic PMN incubated with PBEF sense oligonucleotides, significantly inhibited the apoptosis of control PMN (*P < 0.05), whereas supernatants from antisense-treated septic PMNs induced significantly less inhibition ( P < 0.05 versus sense or no oligonucleotide; P = NS versus controls, n = 5).

Discussion

PBEF was originally isolated from a cDNA library derived from activated peripheral blood lymphocytes as a factor that synergizes with IL-7 to promote the differentiation of B cell precursors (22). The gene for PBEF comprises 11 exons and ten introns, with binding sites for NF-1, AP-1, AP-2, CREB, NF–IL-6, and NF6B in the 5′-flanking region (40). The amino acid sequence for PBEF is highly conserved in both eukaryotic and prokaryotic organisms. PBEF homologs have been identified in the carp (23), in invertebrate mollusks (24), and in bacteria (25), as well as in vertebrates, including humans and the mouse. In humans, PBEF has been shown to be upregulated in distended fetal membranes (41), in denervated muscle (42), and in colorectal cancers (43). The advent of microarray techniques that permit the simultaneous analysis of changes in the expression of hundreds or thousands of genes has generated a number of reports showing that PBEF is upregulated in neutrophils and monocytes following exposure to inflammatory stimuli (44–46). It is significantly upregulated during chorioamnionitis, where it has been localized to both the fetal and maternal membranes and to invading neutrophils (40). Its expression is induced in mammals by LPS and proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 (40), but also by the nonspecific immunostimulators, sodium alginate and scleroglucan in the carp (23), and by xenogeneic sponge molecules in the mollusk (24), suggesting that it plays a highly conserved role in innate immunity. Its presence in invertebrates further suggests biologic function beyond its previously documented role in the promotion of B cell proliferation.

PBEF lacks homology with any other known mammalian protein, and the mechanism of its biologic activity is unknown. The bacterial homolog of the PBEF gene encodes a phosphoribosyl transferase that permits bacterial survival in the absence of exogenous nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) (25). Rongvaux and colleagues reported that murine PBEF functions as a nicotinamide phosphoribosyl transferase involved in NAD biosynthesis (27). Moreover Kitani and coworkers concluded, based on the subcellular localization of rat PBEF in the nucleus of confluent cells but the cytoplasm of proliferating cells, that PBEF is an intracellular protein associated with the cell cycle (28). On the other hand, studies by Samal (22), as well as the data presented here, indicate that even though the protein lacks a signal peptide, it functions as a secreted factor. Specifically, we show that biologically active PBEF is present in supernatants of LPS-stimulated neutrophils and neutrophils from patients with sepsis (Figures 3A, 6C), as well as in the supernatant of CHO cells transfected with a c-myc–tagged PBEF construct (Figure 3B); that recombinant PBEF induces dose-dependent inhibition of the apoptosis of resting neutrophils (Figure 3D); and that the inhibitory activity of conditioned medium from LPS-stimulated neutrophils can be blocked by coincubation with anti-PBEF Ab (Figure 4B). This putative dual activity of PBEF as a cell cycle regulatory protein and a secreted inflammatory cytokine is reminiscent of that recently described for another late-expressed inflammatory mediator, high-mobility group box 1 (47–49). Whether PBEF exerts its antiapoptotic effects through engagement of a receptor is unknown. Alternatively, our observation that PBEF inhibits the activity of the apical caspase, caspase-8, suggests the possibility that PBEF acts directly at the cell membrane, either through a membrane-associated inhibitor of apoptosis such as FLICE-like inhibitory protein (FLIP) (50) or by interactions with regulatory phosphatases in the plasma membrane (51, 52).

If the principal activity of PBEF derives from its role as a secreted factor, it is possible that the monocyte, rather than the neutrophil, is the primary cell involved in PBEF biosynthesis. It has been reported that delayed neutrophil apoptosis following exposure to inflammatory stimuli is a consequence of the activity of contaminating monocytes (32).

Innate immunity in higher vertebrates is mediated through the coordinated action of phagocytic cells and their soluble products. The regulation of innate immunity is complex, but its persistence or termination results, at least in part, from the prolonged survival, on the one hand, or the apoptosis, on the other, of its cellular effectors (53, 54). Quiescent neutrophils are constitutively apoptotic cells. During an inflammatory response, however, the survival of the neutrophil can be prolonged by a variety of mediators of microbial or host origin or accelerated by the phagocytosis of whole organisms (30, 55, 56). Prolonged neutrophil survival during inflammation results from active inhibition of apoptosis, a process that requires new gene expression and the synthesis of survival factors, including IL-1β (20) and poorly characterized intracellular inhibitors of apoptosis. Our findings suggest that PBEF is a common effector of the inhibition of neutrophil apoptosis that follows exposure to divergent inflammatory stimuli. PBEF expression is induced at a much later time point than expression of IL-1 (Figures 1, B and C), and prevention of its translation using an antisense oligonucleotide completely blocks the antiapoptotic activity of a bacterial product, LPS, and a variety of host-derived inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, GM-CSF, IL-8, and TNF-α (Figure 2A).

A central role for PBEF in the expression of inflammation is suggested by its high degree of conservation during evolution. We show here that PBEF is upregulated in cells of the innate immune system, including neutrophils and macrophages, by a variety of proinflammatory stimuli of both host and microbial origin and that this cytokine plays a requisite role in inhibiting the apoptosis of neutrophils exposed to these inflammatory stimuli, as well as in neutrophils harvested from the circulation of critically ill patients with systemic inflammation or sepsis. Multiple lines of investigation implicate activated neutrophils in the pathogenesis of acute organ injury in sepsis (9) and in a variety of chronic disorders including inflammatory bowel disease, arthritis, and Alzheimer disease (13, 57). Yet strategies that block neutrophil activation have proven to be of limited efficacy, in part because they inhibit neutrophil-mediated defenses against an acute infectious challenge (14). In contrast, targeting the biologic processes that mediate the resolution of inflammation represents a rational and attractive therapeutic strategy based on hastening the resolution of inflammation rather than inhibiting its initial expression. Moreover, the disappointing results of interventions that target early mediators of the septic response, such as TNF and IL-1 (58), have led to an interest in identifying mediators of the later stages of the systemic inflammatory response (47, 59), and based on the time course of its appearance, PBEF appears to be one of these.

In health, approximately 1010 neutrophils are released from bone marrow stores each day (60); an equal number die an apoptotic death, thus the numbers of circulating cells remain constant. The biologic demands of inflammation require the ability to increase cell numbers rapidly in response to an acute threat, but also to remove those activated cells once the threat has passed. Thus the regulation of neutrophil survival must be tightly controlled. Neutrophils are constitutively apoptotic, but they also have the ability to subvert their programmed cell death in response to stimuli from the microenvironment of inflammation. Our observations add to an understanding of the mechanisms of this prolonged survival by identifying PBEF as a novel mediator in a common pathway resulting in prolonged neutrophil survival through the inhibition of apoptosis.

Methods

Patient population.

We studied critically ill patients meeting criteria for sepsis syndrome (4) and having a sepsis score (61) of 3 or higher. The study protocol was approved by the Human Ethics Review Board of the University Health Network, and written informed consent was obtained from each subject or a surrogate. Healthy laboratory volunteers served as the source of normal neutrophils.

Materials and reagents.

DMEM, penicillin/streptomycin solution, L-glutamine, PBS, and FCS were purchased from Invitrogen (Burlington, Ontario, Canada). LPS from E. coli 0111:B4 was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Canada Ltd. (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). Recombinant human IL-8 was purchased from Calbiochem-Novabiochem Corp. (San Diego California, USA), while TNF-α, IL-1β, and GM-CSF were from BioSource International (Camarillo California, USA). A rabbit polyclonal Ab raised against a PBEF/bovine growth hormone fusion protein was a kind gift of Baru Samal (Amgen Inc., Thousand Oaks California, USA); mAb to β-actin was from Sigma-Aldrich Canada Ltd. Anti-CD95 (Fas) mAb was purchased from Immunotech (Miami, Florida, USA). Monoclonal murine Ab to caspase-8 was from Oncogene (San Diego California USA), and rabbit polyclonal Ab to caspase-3 was from StressGen Biotechnologies Corp. (Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada). Other chemicals, unless otherwise noted, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Canada Ltd.

Cell isolation and culture.

Up to 20 ml blood was collected in heparinized tubes. Circulating neutrophils (PMNs) and PBMCs were isolated by dextran sedimentation and centrifugation through a discontinuous Ficoll gradient (20). PMNs were resuspended in polypropylene tubes at a concentration of 106 cells/ml in supplemented DMEM (Invitrogen); PBMCs were resuspended in supplemented RPMI-1640 and separated by differential adherence following overnight culture into monocytes and lymphocytes. The purity of neutrophil, lymphocyte, and monocyte populations as assessed by size and granularity was consistently greater than 95%.

HL-60 cells.

HL-60 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Maryland, USA) were maintained in suspension in RPMI supplemented with 10% FCS and used at passage 20–25. Neutrophilic differentiation was induced with 1 ∝M all-trans retinoic acid (62). Cell numbers were counted using a hemocytometer, and cell viability was assessed by trypan blue dye exclusion.

Quantification of apoptosis by flow cytometry.

PMN apoptosis was quantified by flow cytometry as the percentage of cells with hypodiploid DNA reflected as nuclear uptake of propidium iodide by permeabilized cells (20, 63) and as exteriorization of membrane phosphatidylserine, detected by the binding of annexin V (64). Triton X-100–permeabilized cells were incubated with propidium iodide (50 ∝g/ml) prior to analysis with a Coulter Epics XL-MCL cytofluorometer (Coulter Electronics Ltd., Hialeah, Florida, USA). A minimum of 5,000 events were collected and analyzed. Annexin V binding was detected using a commercially available kit (TACS-annexin V-FITC, TA4638; R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Caspase activity assay.

Assay of caspase activity was performed using a caspase assay kit (BioSource International). Cell lysates were incubated with 25 ∝l of a specific substrate for caspase-3 (Ac-DEVD-pNA), caspase-8 (Ac-IETD-pNA), or caspase-9 (Ac-LEHD-pNA) in a 96-well plate. Following overnight incubation, plates were read using a colorimetric plate reader (Titertek Instruments Inc., Huntsville, Alabama, USA) at 409 nm.

Real-time PCR.

RNA was extracted from neutrophils and HL-60 cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). A total of 1 ∝g RNA was reverse transcribed to first-strand DNA using the SuperScript II system (Invitrogen) employing primers for PBEF designed and evaluated using Primer Express software (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA) as follows: forward 5′-ATGTTCTCTTCACGGTCGAAAAC-3′ and reverse 5′-GGCCACTTTGATTGGATACCA-3′. Real-time PCR was performed as described (65, 66) using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems, Warrington, United Kingdom) and amplifying cDNA with an ABI PRISM 7700 Sequence Detection System (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems) under universal thermal cycling conditions. Experimental results were normalized to the threshold cycle (CT) of GAPDH, and CT values were converted to relative transcript copy numbers by comparison with the appropriate standard curves.

Northern blot analysis.

RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), and 5 ∝g/ml of denatured RNA was electrophoresed through a 1.3% formaldehyde-agarose gel, and transferred to nylon membrane (New England Nuclear Labs; Life Science Products Inc., Boston, Massachusetts, USA). A probe for PBEF was synthesized from a 500-bp cDNA fragment digested using HindII from a pCDNA3.1/PBEF recombinant plasmid using the random primer method (T7 Quick Primer kit; Amersham Biosciences Corp., Piscataway, New Jersey, USA). Hybridization was performed at 42°C for 18 hours, and the final stringency wash in 0.1 ∞ SSC, 0.1% SDS, was performed at 65°C for 6 minutes. Autoradiography was carried out at –70°C using Kodak Scientific Imaging Film (Eastman Kodak Co., Rochester, New York, USA). Membranes were stripped and hybridized to a human GAPDH cDNA probe as an internal standard.

Western blot analysis.

PMNs (2 ∞ 106) were lysed in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 10 ∝g/ml leupeptin, 10 ∝g/ml aprotinin). Samples were run on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to nitrocellulose (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Filters were probed with anti-PBEF polyclonal Ab (a gift of Amgen Inc.) at 1:500 dilution or with other Ab as indicated and detected with a HRP-conjugated second Ab at a dilution of 1:4,000 using the ECL Western blotting detection system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Blots were stripped and reprobed with a mAb to β-actin at 1:4,000 dilution to confirm equal loading of the gels.

SSH.

cDNA for SSH (21) was synthesized using a SMART PCR cDNA Synthesis Kit (CLONTECH Laboratories Inc., Palo Alto, California, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 1 ∝g total RNA from 20 ∞ 106 neutrophils, either quiescent or incubated for 5 hours with 50 pg/ml IL-1β, was used to generate a tester cDNA from the IL-1β–treated cells and a driver cDNA from the control cells. PCR was performed on the GeneAmp 2400 (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, Connecticut, USA) for 18 cycles. SSH was performed using the PCR-Select cDNA subtraction kit (CLONTECH Laboratories Inc.). Differentially expressed transcripts were selectively amplified by suppression PCR as described in the user manual, and amplified cDNA’s were ligated into a 3.9-Kb pT-Adv vector (CLONTECH Laboratories Inc.) for transformation and blue-white selection. Forty plasmid colonies were analyzed by restriction enzyme mapping and sequencing.

Sequencing analysis.

The nucleotide sequence of isolated cDNA clones was determined using the dRhodamine Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems), running samples in an ABI Prism 377 (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems). The resulting sequences were compared with sequences in the GenBank database using the BLAST homology search program from the National Center for Biotechnical Information (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

PBEF antisense oligonucleotides.

An antisense oligonucleotide designed to target the translation initiation site of PBEF was constructed at the Hospital for Sick Children (Toronto, Ontario, Canada) and modified with phosphorothioated backbones to activate RNAse H and modified 5′ and 3′ terminal bases to resist nuclease attack; the sequence for the antisense was 5′-TTCTGCCGCAGGATTCATCTCGGG-3′. Phosphorothioated control oligonucleotides included a sense oligonucleotide based on the translation initiation site of PBEF (5′-CCCGAGATGAATCCTGCGGCCCAGAA-3′) and a nonsense oligonucleotide incorporating the same nucleic acids as the antisense probe, but in a scrambled sequence (5′-GTCATGCCAAGTCGTTCGTGCGGT-3′). Specificity of each probe was confirmed by BLAST analysis. PMNs (106) were incubated for 5 hours in 1 ml DMEM with 10 ∝M sense, antisense, or nonsense oligonucleotide prior to study.

Construction of PBEF plasmids.

Total RNA from control PMNs was extracted using TRIzol reagent and 1 ∝g RNA transcribed to first-strand cDNA using the SuperScript II system (Invitrogen). The cDNA was amplified with the upstream primer, 5′-GCGAATTCGCCACCATGAATCCTGCGGCAGAAGC-3′, containing an EcoRI restriction site and a Kozak sequence for eukaryotic transfection, and 5′-GCGAATTCCCCACCCAACACAAGCAAAG-3′, containing an EcoR1 restriction site for prokaryotic transfection. The downstream primer for both was 5′-GCCTCGAGATGATGTGCTGCTTCCAGTTC-3′, containing an XhoI restriction site. Full-length PBEF fragments, including the signal sequence and fragments encoding the mature PBEF peptide sequence, were cloned into pCDNA3.1/myc-his vector or the GST-Gene Fusion system pGEX-4T-3 vector. The recombinant plasmids were transfected into DH5α-competent cells (Invitrogen) and colonies identified by restriction enzyme digestion and sequencing.

Transfection and immunoprecipitation.

PBEF/pCDNA3.1-myc recombinant plasmids (2.5 μg) were transfected into 2 ∞ 105 CHO cells with 10 ∝l Fugene 6 (Roche Diagnostic Systems, Summerville, New Jersey, USA). Cultures were maintained for 1 day, then washed and recultured for an additional 24 hours. Conditioned medium was collected and concentrated 30-fold with a centrifugal filter device (Millipore Corp., Bedford, Massachusetts, USA); transfectants were lysed with lysis buffer (100 mM NaCl, 50 mM HEPES, 20 mM NaF, 1 mM EDTA, and 1% Triton X-100). Anti–c-myc Ab (16 ∝l; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, California, USA) was added to the supernatants from cell lysates or conditioned medium and incubated for 1 hour at 4°C. Protein G beads (40 ∝l) were added for an additional 1 hour, spun and washed three times in PBS, and boiled with loading buffer for 5 minutes prior to SDS-PAGE.

Purification and identification of PBEF/GST fusion protein.

E. coli transfected with the GST-PBEF/pGEX-4T-3 plasmid were cultured in Luria-Bertani medium with 2% glucose and 100 ∝g/ml ampicillin at 37°C to an A600 (absorption at 600 nm) of 0.8–1.0, then induced with 0.1 mM isopropyl-β D-thiogalactopyranoside for 1 hour at 25°C. Pelleted cells were resuspended in cold STE buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl) with lysozyme (100 ∝g/ml). After 30 minutes of incubation at 4°C, lysates were mixed with glutathione Sepharose 4B beads (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature. Eluted proteins were dialyzed for 48 hours against PBS, and contaminating endotoxin was removed by phase separation with Triton X-114. Residual Triton X-114 was removed using S/D solvent detergent removal resin (Sigma-Aldrich) as described (67). The resulting preparation was probed with anti-GST Ab (StressGen Biotechnologies Corp.) and anti-PBEF Ab to confirm the identity of the product.

Chromogenic limulus amebocyte lysate assay for endotoxin.

Purified PBEF-GST fusion protein was tested for endotoxin contamination using the chromogenic modification of the limulus amebocyte lysate assay (BioWhittaker Inc., Walkersville, Maryland, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis.

Unless otherwise noted, data are expressed as means ± SEM. Continuous data were analyzed by ANOVA with post hoc Student-Neuman-Keuls test; categorical data were evaluated using chi square (χ2) or Fisher exact tests as appropriate. Significance was assumed for P values less than 0.05.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge with gratitude the efforts of Marilyn Steinberg in identifying and following patients for clinical studies and Jakov Moric for early technical assistance. We are also grateful to Baru Samal and Chris Saris, Amgen Ltd., for providing polyclonal Ab to PBEF and PBEF mRNA, as well as for helpful discussions. This work was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, MOP-36053 and MOP-62908 (to J.C. Marshall).

Footnotes

Nonstandard abbreviations used: pre–B cell colony-enhancing factor (PBEF); expressed sequence tag (EST); FLICE-like inhibitory protein (FLIP); glutathione S-transferase (GST); multiple organ dysfunction (MOD); nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD); polymorphonuclear neutrophil (PMN); suppressive subtractive hybridization (SSH); threshold cycle (CT).

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Riedemann NC, Guo R-F, Ward PA. The enigma of sepsis. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;112:460–467. doi:10.1172/JCI200319523. doi: 10.1172/JCI19523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen J. The immunopathogenesis of sepsis. Nature. 2002;420:885–891. doi: 10.1038/nature01326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angus DC, et al. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit. Care Med. 2001;29:1303–1310. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bone RC, et al. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Chest. 1992;101:1644–1655. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.6.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lekstrom-Himes JA, Gallin JI. Immunodeficiency diseases caused by defects in phagocytes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000;343:1703–1714. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012073432307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beutler B, Poltorak A. Sepsis and evolution of the innate immune response. Crit. Care Med. 2001;29(Suppl.):S2–S7. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marie C, et al. Presence of high levels of leukocyte-associated interleukin-8 upon cell activation and in patients with sepsis syndrome. Infect. Immun. 1997;65:865–871. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.3.865-871.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gautam N, et al. Heparin-binding protein (HBP/CAP37): a missing link in neutrophil-evoked alteration of vascular permeability. Nat. Med. 2001;7:1123–1127. doi: 10.1038/nm1001-1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee WL, Downey GP. Leukocyte elastase. Physiological functions and role in acute lung injury. Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care Med. 2001;164:896–904. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.5.2103040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ho JS, Buchweitz JP, Roth RA, Ganey PE. Identification of factors from rat neutrophils responsible for cytotoxicity to isolated hepatocytes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1996;59:716–724. doi: 10.1002/jlb.59.5.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kubes P, Hunter J, Granger DN. Ischemia/reperfusion induced feline intestinal dysfunction: importance of granulocyte recruitment. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:807–812. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90010-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lauriat S, Linas SL. The role of neutrophils in acute renal failure. Semin. Nephrol. 1998;18:498–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weiss SJ. Tissue destruction by neutrophils. N. Engl. J. Med. 1989;320:365–376. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198902093200606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith JA. Neutrophils, host defense, and inflammation: a double-edged sword. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1994;56:672–686. doi: 10.1002/jlb.56.6.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Savill JS, Wyllie AH, Henson JE, Henson PM, Haslett C. Macrophage phagocytosis of aging neutrophils in inflammation. J. Clin. Invest. 1989;83:865–875. doi: 10.1172/JCI113970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee A, Whyte MKB, Haslett C. Inhibition of apoptosis and prolongation of neutrophil functional longevity by inflammatory mediators. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1993;54:283–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jimenez MF, et al. Dysregulated expression of neutrophil apoptosis in the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) Arch. Surg. 1997;132:1263–1270. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1997.01430360009002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keel M, et al. Interleukin-10 counterregulates proinflammatory cytokine-induced inhibition of neutrophil apoptosis during severe sepsis. Blood. 1997;90:3356–3363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matute-Bello G, et al. Modulation of neutrophil apoptosis by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor during the course of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit. Care Med. 2000;28:1–7. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200001000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watson RWG, Rotstein OD, Parodo J, Bitar R, Marshall JC. The interleukin-1 beta converting enzyme (caspase-1) inhibits apoptosis of inflammatory neutrophils through activation of IL-1β. J. Immunol. 1998;161:957–962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diatchenko L, et al. Suppressive subtractive hybridization: a method for generating differentially regulated or tissue-specific cDNA probes and libraries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996;93:6025–6030. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.6025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Samal B, et al. Cloning and characterization of the cDNA encoding a novel human pre-B-cell colony-enhancing factor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994;14:1431–1437. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.2.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fujiki K, Shin D-H, Nakao M, Yano T. Molecular cloning and expression analysis of the putative carp (Cyprinus carpio) pre-B cell enhancing factor. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2000;10:383–385. doi: 10.1006/fsim.2000.0263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muller WE, et al. Increased gene expression of a cytokine-related molecule and profilin after activation of Suberites domuncula cells with xenogeneic sponge molecule(s) DNA Cell Biol. 1999;18:885–893. doi: 10.1089/104454999314746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin PR, Shea RJ, Mulks MH. Identification of a plasmid-encoded gene from Haemophilus ducreyi which confers NAD independence. J. Bacteriol. 2001;183:1168–1174. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.4.1168-1174.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ognjanovic S, Bryant-Greenwood GD. Pre-B cell colony-enhancing factor, a novel cytokine of human fetal membranes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002;187:1051–1058. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.126295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rongvaux A, et al. Pre-B cell colony-enhancing factor, whose expression is up-regulated in activated lymphocytes, is a nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase, a cytosolic enzyme involved in NAD biosynthesis. Eur. J. Immunol. 2002;32:3225–3234. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200211)32:11<3225::AID-IMMU3225>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kitani T, Okuno S, Fujisawa H. Growth phase-dependent changes in the subcellular localization of pre-B-cell colony-enhancing factor. FEBS Lett. 2003;544:74–78. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00476-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marshall, J.C., Jia, S.-H., and Taneja, R. 2002. Dysregulated neutrophil apoptosis in the pathogenesis of organ injury in critical illness. In Mechanisms of organ dysfunction in critical illness. M.P. Fink and T.W. Evans, editors. Springer-Verlag. Berlin, Germany. 110–123.

- 30.Rotstein D, Parodo J, Taneja R, Marshall JC. Phagocytosis of Candida albicans induces apoptosis of human neutrophils. Shock. 2000;14:278–283. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200014030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bennett CF, Chiang MY, Chan H, Shoemaker JE, Mirabelli CK. Cationic lipids enhance cellular uptake and activity of phosphorothirate antisense oligonucleotides. Mol. Pharmacol. 1992;41:1023–1033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sabroe I, Jones EC, Usher LR, Whyte MK, Dower SK. Toll-like receptor (TLR)2 and TLR4 in human peripheral blood granulocytes: a critical role for monocytes in leukocyte lipopolysaccharide responses. J. Immunol. 2002;168:4701–4710. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thornberry NA, Lazebnik YA. Caspases: enemies within. Science. 1998;281:1312–1316. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hengartner MO. The biochemistry of apoptosis. Nature. 2000;407:770–776. doi: 10.1038/35037710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chinnaiyan AM, O’Rourke K, Tewari M, Dixit VM. FADD, a novel death domain-containing protein, interacts with the death domain of Fas and initiates apoptosis. Cell. 1995;81:505–512. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90071-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Susin SA, et al. Mitochondrial release of caspase-2 and -9 during the apoptotic process. J. Exp. Med. 1999;189:381–393. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.2.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Enari M, et al. A caspase-activated DNase that degrades DNA during apoptosis, and its inhibitor ICAD. Nature. 1998;391:43–50. doi: 10.1038/34112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit. Care Med. 1985;13:818–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marshall JC, et al. Multiple organ dysfunction score: A reliable descriptor of a complex clinical outcome. Crit. Care Med. 1995;23:1638–1652. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199510000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ognjanovic S, et al. Genomic organization of the gene coding for human pre-B-cell colony enhancing factor and expression in human fetal membranes. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2001;26:107–117. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0260107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nemeth E, Millar LK, Bryant-Greenwood G. Fetal membrane distention: II. Differentially expressed genes regulated by acute distention in vitro. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002;182:60–67. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(00)70491-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tang H, Cheung WM, Ip FC, Ip NY. Identification and characterization of differentially expressed genes in denervated muscle. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2000;16:127–140. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2000.0864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Beijnum JR, et al. Target validation for genomics using peptide-specific phage antibodies: a study of five gene products overexpressed in colorectal cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 2002;101:118–127. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Subrahmanyam YVBK, et al. RNA expression patterns change dramatically in human neutrophils exposed to bacteria. Blood. 2001;97:2457–2468. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.8.2457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nau GJ, et al. Human macrophage activation programs induced by bacterial pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:1503–1508. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022649799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu L-G, Wu M, Hu J, Zhai Z, Shu H-B. Identification of downstream genes up-regulated by the tumor necrosis factor family member TALL-1. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2002;72:410–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang H, et al. HMG-1 as a late mediator of endotoxin lethality in mice. Science. 1999;285:248–251. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5425.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park JS, et al. Activation of gene expression in human neutrophils by high mobility group box 1 protein. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2003;284:C870–C879. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00322.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brezniceanu ML, et al. HMGB1 inhibits cell death in yeast and mammalian cells and is abundantly expressed in human breast carcinoma. FASEB J. 2003;17:1295–1297. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0621fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Irmler M, et al. Inhibition of death receptor signals by cellular FLIP. Nature. 1997;388:190–195. doi: 10.1038/40657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Daigle I, Yousefi S, Colonna M, Green DR, Simon H-U. Death receptors bind SHP-1 and block cytokine-induced anti-apoptotic signaling in neutrophils. Nat. Med. 2002;8:61–67. doi: 10.1038/nm0102-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gardai S, et al. Activation of SHIP by NADPH oxidase-stimulated Lyn leads to enhanced apoptosis in neutrophils. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:5236–5246. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110005200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Savill J. Apoptosis in resolution of inflammation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1997;61:375–380. doi: 10.1002/jlb.61.4.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Savill J, Fadok V. Corpse clearance defines the meaning of cell death. Nature. 2000;407:784–788. doi: 10.1038/35037722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee A, Whyte MKB, Haslett C. Inhibition of apoptosis and prolongation of neutrophil functional longevity by inflammatory mediators. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1993;54:283–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Watson RWG, Redmond HP, Wang JH, Condron C, Bouchier-Hays D. Neutrophils undergo apoptosis following ingestion of Escherichia coli. J. Immunol. 1996;156:3986–3992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nicholson DW. From bench to clinic with apoptosis-based therapeutic agents. Nature. 2000;407:810–816. doi: 10.1038/35037747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marshall JC. Such stuff as dreams are made on: mediator-targeted therapy in sepsis. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2003;2:391–405. doi: 10.1038/nrd1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bernard GR, et al. Efficacy and safety of recombinant human activated protein C for severe sepsis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;344:699–709. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103083441001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reed JC. Apoptosis-based therapies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2002;1:111–121. doi: 10.1038/nrd726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Marshall JC, Sweeney D. Microbial infection and the septic response in critical surgical illness. Sepsis, not infection, determines outcome. Arch. Surg. 1990;125:17–23. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1990.01410130019002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Watson RWG, et al. Granulocytic differentiation of HL-60 cells results in expression of caspase-dependent programmed cell death. FEBS Lett. 1997;412:603–606. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00779-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nicoletti I, Migliorati G, Pagliacci MC, Grignani F, Riccardi C. A rapid and simple method for measuring thymocyte apoptosis by propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry. J. Immunol. Methods. 1991;139:271–276. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(91)90198-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Homburg CH, et al. Human neutrophils lose their surface Fc gamma RIII and acquire Annexin V binding sites during apoptosis in vitro. Blood. 1995;85:532–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bustin SA. Absolute quantification of mRNA using real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction assays. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2000;25:169–193. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0250169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Johnson MR, Wang K, Smith JB, Heslin MJ, Diasio RB. Quantitation of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase expression by real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. Anal. Biochem. 2000;278:175–184. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Aida Y, Pabst MJ. Removal of endotoxin from protein solutions by phase separation using Triton X-114. J. Immunol. Methods. 1990;132:191–195. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(90)90029-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]