Abstract

The human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER)2 provides an excellent target for selective delivery of cytotoxic drugs to tumor cells by antibody-drug conjugates (ADC) as has been clinically validated by ado-trastuzumab emtansine (KadcylaTM). While selecting a suitable antibody for an ADC approach often takes specificity and efficient antibody-target complex internalization into account, the characteristics of the optimal antibody candidate remain poorly understood. We studied a large panel of human HER2 antibodies to identify the characteristics that make them most suitable for an ADC approach. As a model toxin, amenable to in vitro high-throughput screening, we employed Pseudomonas exotoxin A (ETA’) fused to an anti-kappa light chain domain antibody. Cytotoxicity induced by HER2 antibodies, which were thus non-covalently linked to ETA’, was assessed for high and low HER2 expressing tumor cell lines and correlated with internalization and downmodulation of HER2 antibody-target complexes. Our results demonstrate that HER2 antibodies that do not inhibit heterodimerization of HER2 with related ErbB receptors internalize more efficiently and show greater ETA’-mediated cytotoxicity than antibodies that do inhibit such heterodimerization. Moreover, stimulation with ErbB ligand significantly enhanced ADC-mediated tumor kill by antibodies that do not inhibit HER2 heterodimerization. This suggests that the formation of HER2/ErbB-heterodimers enhances ADC internalization and subsequent killing of tumor cells. Our study indicates that selecting HER2 ADCs that allow piggybacking of HER2 onto other ErbB receptors provides an attractive strategy for increasing ADC delivery and tumor cell killing capacity to both high and low HER2 expressing tumor cells.

Keywords: HER2, Pseudomonas exotoxin A, antibody-drug conjugate, cancer, monoclonal antibody

Introduction

The human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER)2 is a 185-kDa cell surface receptor tyrosine kinase and member of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) family that comprises four distinct receptors: EGFR/ErbB-1, HER2/ErbB-2, HER3/ErbB-3, and HER4/ErbB-4. Both homo- and heterodimers are formed by the four members of the EGFR family, with HER2 being the preferred and most potent dimerization partner for all other ErbBs.1,2 HER2 has no known ligand, but can be activated via homodimerization when overexpressed, or by heterodimerization with other, ligand-occupied ErbB receptors.3 Depending on the dimerization partner, HER2 induces activation of the MAPK pathway, thereby stimulating proliferation, or the PI3K-Akt pathway, which promotes cell survival.4 Overexpression of HER2 has been described in a wide variety of cancers, including breast, ovarian, gastric and non-small cell lung cancer.4

HER2 is a clinically well-validated target for antibody therapy and proven to be suitable for an antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) approach through ado-trastuzumab emtansine (KadcylaTM).5,6 Ado-trastuzumab emtansine, which is approved for therapy of metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer,7 consists of trastuzumab conjugated via a non-reducible thioether linker to the fungal toxin and tubulin inhibitor maytansine. This ADC was designed to release the drug upon complete degradation in the lysosomes of targeted cells, and demonstrated great efficacy against HER2 overexpressing tumors, without affecting healthy tissue with normal HER2 expression levels.5,6,8 The drug was found to retain the mechanisms of action of unconjugated trastuzumab, including inhibition of PI3K/AKT signaling and HER2 ectodomain shedding, and induction of antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC).9

While many antibody characteristics are taken into account when selecting a suitable antibody for HER2-targeted therapy, it is typically considered an advantage for an ADC approach if the HER2/antibody complex efficiently internalizes upon antibody binding. In healthy tissue, the intensity of ErbB receptor signaling in cells is controlled by accelerated receptor internalization and degradation upon ErbB ligand binding. However, for the orphan HER2 receptor, no such internalization mechanism exists and all expressed HER2 predominantly localizes to the plasma membrane.10-12 Notably, increased EGFR or HER3 expression results in increased endocytosis of HER2, especially in the presence of ligand.13,14

In this study, we analyzed a diverse panel of human HER2 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) for their suitability as an ADC. Internalization and cytotoxicity of HER2 antibodies were studied in an in vitro test system by generating non-covalently linked immunotoxins using a human kappa light chain-directed truncated version of Pseudomonas exotoxin A. Receptor internalization and cytotoxicity was correlated with expression and activation levels of different ErbB receptors on tumor cells to identify HER2 antibodies that both internalize efficiently and, as an ADC, kill cells with a range of HER2 expression levels. In particular, HER2 antibodies that can utilize HER2 heterodimer-driven internalization seem very attractive for future HER2-targeted ADC therapeutics, especially to target tumor indications with lower HER2 expression.

Results

Characterization of HER2 antibody cross-competition groups

A panel of 134 human HER2-specific antibodies was generated in human antibody transgenic mice using hybridoma technology.15 Based on apparent affinities and sequence diversity, 72 HER2 mAbs were selected for further characterization in a cross-competition ELISA with the HER2 extracellular domain (HER2ECDHis). Four distinct cross-competition groups of mAbs were defined (Table S1). Group 1 comprised 12 mAbs, including mAb-169 and trastuzumab (Herceptin®), which has previously been mapped to an epitope in domain IV of HER2.16,17 Group 2 comprised 17 mAbs, including mAb-025 and HEK-293-produced pertuzumab (TH-pertuzumab), which is known to recognize an epitope in domain II of HER2.18,19 mAb-169 and -025 were chosen as representative mAbs for their Group 1 and 2 respectively. Group 3 comprised 22 mAbs that did not compete for binding to HER2ECDHis with antibodies from other cross competition groups. Within Group 3 some variation was observed as some antibodies did not compete with each other for binding to HER2ECDHis, but did compete with the other Group 3 antibodies. Therefore we divided these antibodies in two subgroups, 3a and 3b, for which two representative antibodies, 098 and 153, were selected for further characterization. Finally, Group 4 comprised 21 mAbs that competed with each other for binding to HER2ECDHis, but not with any of the other cross-competition groups. mAb 005 was selected from Group 4 for further characterization.

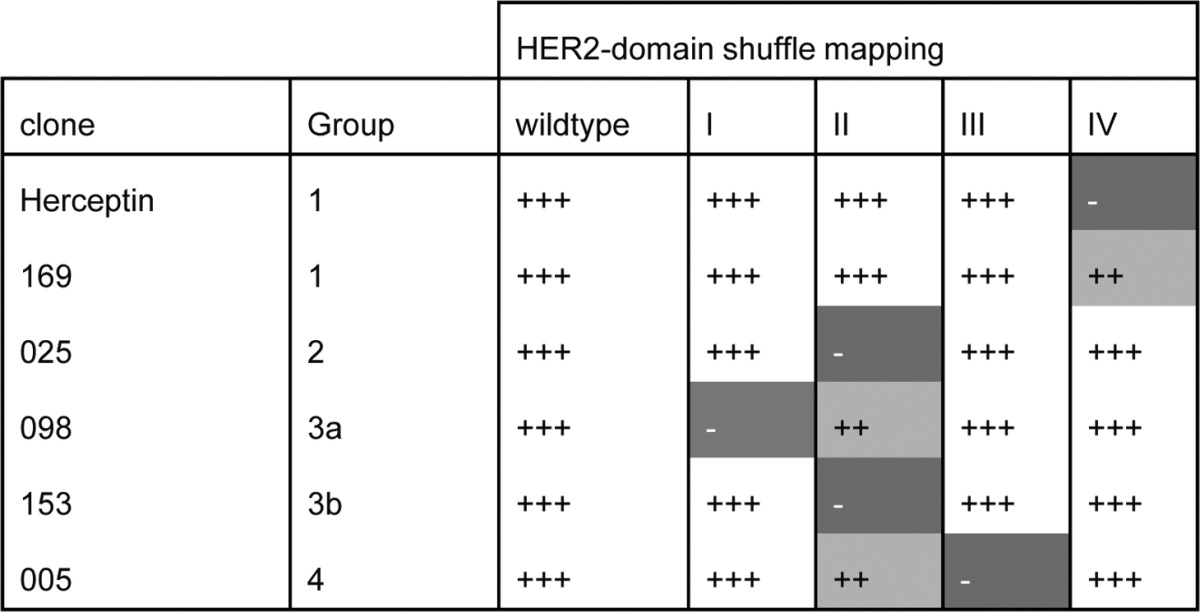

To map the regions recognized and characterize epitope diversity between the four different groups of mAbs, a HER2 ECD shuffle experiment was performed. Five constructs were generated by swapping the sequences of domain I, II, III, or IV of the extracellular domain of human HER2 with the corresponding sequence of chicken HER2. The wild-type construct is referred to as hu-HER2 and the mutants as hu-HER2-ch(I) to -(IV), respectively. The human and chicken HER2 orthologs show 67% homology in their ECD (62% homology in domain I, 72% in domain II, 63% in domain III and 68% in domain IV). The generated constructs were expected to result in a protein with domains that are sufficiently homologous to allow correct folding, but different enough to remove epitopes recognized by human HER2 specific mAbs. Group 1 mAbs trastuzumab and 169 showed loss of binding to Hu-HER2-ch(IV), but not to the other shuffle proteins, confirming that the epitopes of Group 1 mAbs reside in HER2 domain IV (Table 1; Fig. S1). Group 2 antibody 025 only showed loss of binding for Hu-HER2-ch(II), confirming that its epitope resides in HER2 domain II. The distinction between Group 3a and 3b mAbs 098 and 153 was confirmed in the shuffle experiment in which mAb 098 showed loss of binding to Hu-HER2-ch(I) and a small decrease in binding to Hu-HER2-ch(II), whereas mAb 153 only showed strong loss of binding to Hu-HER2-ch(II). The Group 4 mAb 005 showed loss of binding upon substitution of HER2 domain III, and partially decreased binding to Hu-HER2-ch(II) (Table 2).

Table 1. Summary of antibody binding to different HER2 receptor constructs.

Wild-type; hu-HER2, I; hu-HER2-ch(I), II; hu-HER2-ch(II), III; hu-HER2-ch(III), IV; hu-HER2-ch(IV) +++ Indicates wild-type binding or binding similar to wild-type binding, ++ indicates reduced EC50 but similar maximal binding compared with wild-type binding, - indicates no binding detected. See Figure S1 for dose-response binding curves.

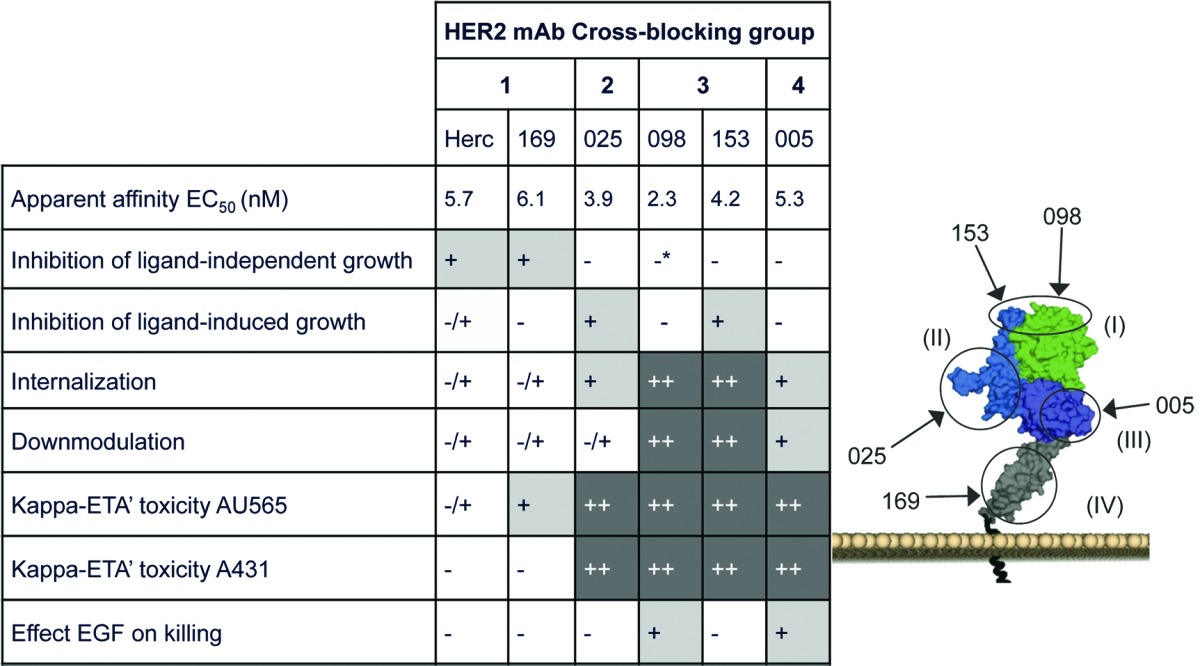

Table 2. Summary antibody characteristics.

Summary of the different antibody characteristics and representation of the different HER2 epitopes recognized. Flow cytometry was applied to determine the apparent antibody affinities on A431 cells which were depicted as EC50 value. HER2 structure was obtained from Franklin et al.18 *Significantly agonistic.

Next, the epitopes of HER2 antibodies 005 and 153 were predicted using Chemically Linked Immunogenic Peptides on Scaffolds (CLIPS™) technology.20,21 Antibody binding was tested on linear and looped CLIPS of 15 to 35 amino acids, which were designed to allow for mapping of conformational epitopes on the human HER2 extracellular domain. Group 3 mAb 153 demonstrated binding to peptides including sequence RCKGPLPTD, suggesting binding to domain II on top of HER2 (Fig. S2). For the Group 4 mAb 005, two distinct peptides were predicted to be part of the epitope (GISWLGLRSLREL and IHHNTHLCFVHTVPW), which both reside in domain III distant from the dimerization regions (Fig. S2). We were unable to map the representative mAbs from the other groups using the CLIPS approach.

Taken together, our data demonstrated that the HER2 mAbs could be divided in four major groups based on their binding sites on HER2, with Group 1 antibodies binding epitopes in HER2 domain IV, Group 2 binding epitopes in HER2 domain II, Group 3a and 3b antibodies binding epitopes in a region overspanning HER2 domain I/II, and Group 4 antibodies that recognized epitopes in HER2 domain III.

Proliferation inhibition by HER2 antibodies

Representative antibodies from each cross-competition group were tested for their ability to inhibit HER2-driven proliferation. Because HER2 is an orphan receptor, it normally requires ligand-induced heterodimerization with other ErbB family members for its signaling, such as EGF-induced EGFR/HER2 or heregulin-induced HER2/HER3 heterodimerization.1 However, when highly overexpressed, HER2 can signal as a homodimer in a ligand-independent fashion. HER2 homodimerization-induced signaling was distinguished from heterodimerization-induced signaling by analyzing ligand-independent and ligand-induced proliferation.

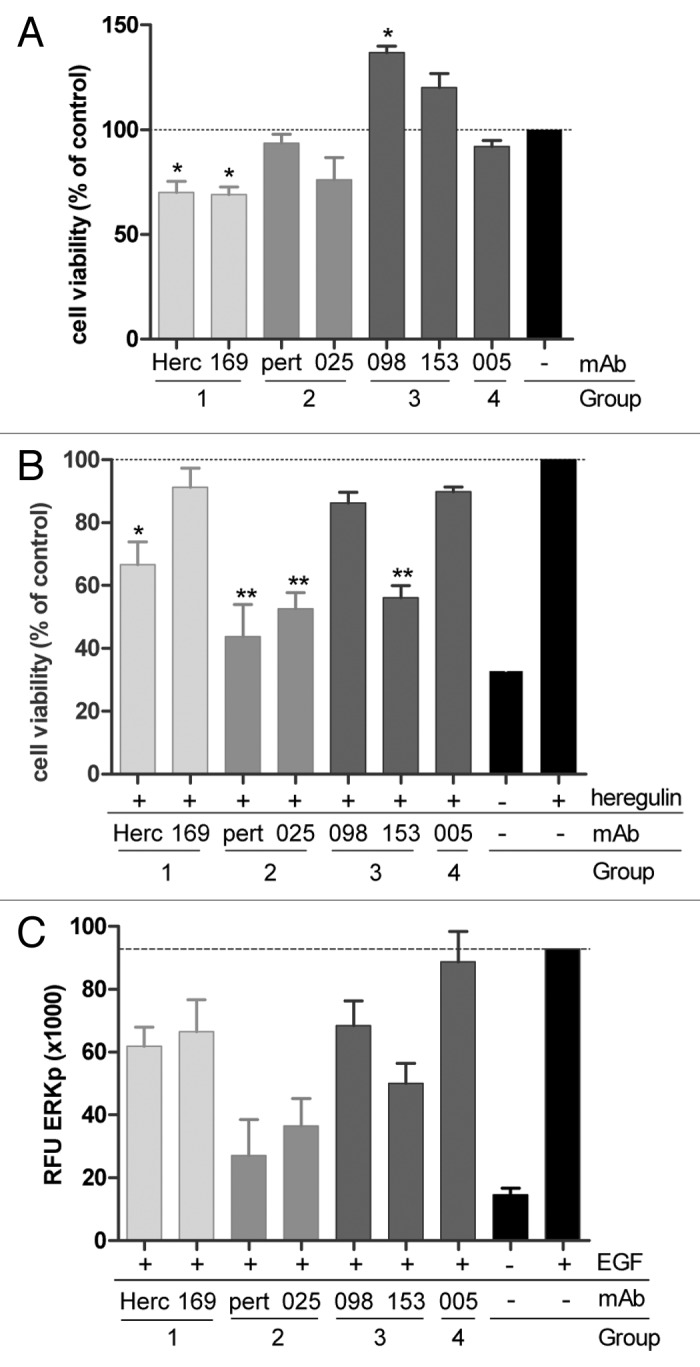

The ability of HER2 mAbs to inhibit ligand-independent proliferation was tested in AU565 cells, which express very high HER2 levels (Table S2). Group 1 antibodies demonstrated significant inhibition of AU565 cell proliferation (Fig. 1A), consistent with what has previously been described for trastuzumab.17 mAb from Group 2 or 4 did not show any effect on ligand-independent AU565 proliferation. In contrast, both Group 3 mAb enhanced proliferation of HER2-overexpressing AU565 cells. These data indicate that Group 1 mAb, which bind HER2 domain IV, can interfere with signaling induced by HER2 homodimerization when the receptor is highly overexpressed.

Figure 1. In vitro inhibition of proliferation and ERK phosphorylation by HER2 antibodies. (A) Inhibition of proliferation of AU565 cells. Cell viability is presented as a percentage relative to untreated cells (± SD, n = 3), (*P < 0.05). (B) Inhibition of proliferation of MCF7 Cell viability is presented as a percentage relative to cells stimulated with Heregulin-β1 only (± SD, n = 3), (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). (C) Inhibition of ERK phosphorylation in AU565. The amount of phosphorylated ERK was quantified using a phospho-ERK specific AlphaScreen® assay. Values depicted are the mean of at least two experiments ± SD.

The potential of HER2 mAbs to inhibit HER2 heterodimerization-driven proliferation was tested in MCF7 cells, which express comparable levels of HER2 and HER3 (Table S2) and are responsive to the HER3 ligand heregulin-β1.22 Figure 1B demonstrates that heregulin-β1-induced proliferation of MCF7 cells was inhibited by the HER2 domain II binding Group 2 mAbs and Group 3b mAb 153. The Group 3a mAb 098, for which the epitope was mainly defined to residues in HER2 domain I and only displayed limited binding to domain II, did not affect heregulin-β1-induced MCF-7 proliferation. Group 1 and 4 antibodies also had no effect on heregulin-β1-induced proliferation, with the exception of trastuzumab, which demonstrated some inhibitory effect, although with lower significance.

HER2 can also signal through ligand-activated EGFR.1 Therefore, our conclusions for HER2 heterodimerization-dependent signaling were confirmed by assessing EGF-induced EGFR/HER2 heterodimerization and downstream ERK phosphorylation in AU565 cells (Fig. 1C). Here again, Group 2 mAb inhibited ligand-dependent signaling most prominently. These data suggest that binding to HER2 domain II is critical for the ability of HER2 antibodies to interfere with ligand-induced HER2 heterodimerization and signaling, consistent with what has previously been described for pertuzumab.18,19

HER2 antibody-induced internalization and HER2 downmodulation

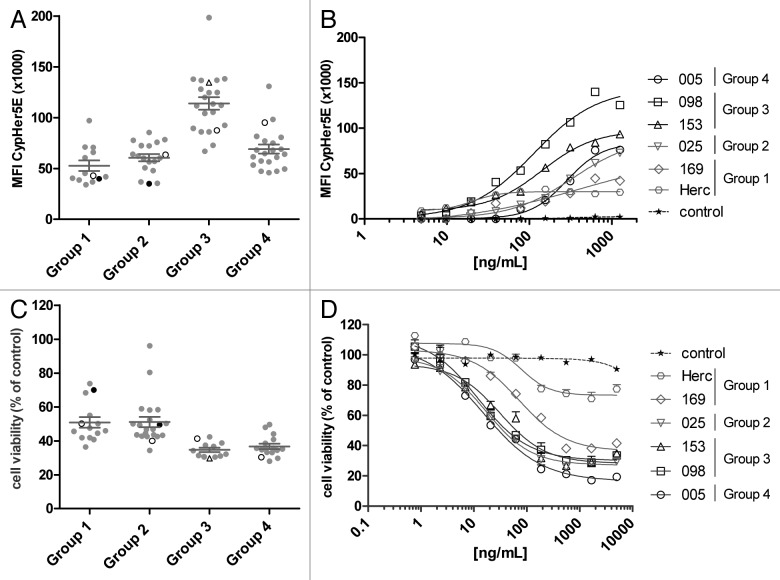

A prerequisite for an ADC approach is efficient internalization of the antibody-target complex. A CypHer5E-based internalization assay was performed to investigate the internalization capacity of the mAbs. All 72 HER2 mAbs of the four cross-competition groups described above were tested. AU565 cells were incubated with HER2 mAbs that were indirectly labeled with the pH-sensitive dye CypHer5E conjugated to Fab fragments of a goat anti-human IgG antibody, which becomes fluorescent in the acid environment of the endosomal/lysosomal compartments upon internalization (Fig. 2A and B). Group 3 mAbs clearly showed enhanced receptor internalization compared with the other cross-competition groups. Group 1 mAbs, in contrast, induced receptor internalization relatively poorly. This was further illustrated by the dose response curves generated for the representative mAbs of each cross-competition group (Fig. 2B). These data show that antibody internalization was strongly induced by Group 3 HER2 antibodies in particular, and to a lesser extent by antibodies from the other cross-competition groups.

Figure 2. Internalization and HER2-mAb α-kappa-ETA’ induced killing of AU565 cells. (A, B) Cells were seeded and incubated for 9 h at RT with CypHer5E-conjugated Fab fragments of goat anti-human IgG and serially diluted HER2 antibodies. (A) Maximal “counts × fluorescence” is plotted. Each dot represents a different antibody. In black are trastuzumab (Group 1) and TH-pertuzumab (Group 2). The open symbols represent the representative mAbs from each Group. Within Group 3, mAb 098 was depicted as triangle and mAb 153 as circle. Antibodies from Group 3 induced significantly more CypHer5E fluorescence compared with mAbs from Groups 1, 2 and 4 (P < 0.001). (B) Dose-response curves of mAbs representing each of the Groups (n = 2). (C, D) Viability of AU565 cells after 3 d incubation with HER2 antibodies pre-incubated with 0.1 µg/mL α-kappa-ETA’. Antibodies from Groups 3 and 4 induced significantly more cytotoxicity compared with mAbs from Groups 1 and 2 (P < 0.001). (C) Each dot represents the maximal reduction in cell viability induced by a different antibody. In black are trastuzumab and TH-pertuzumab. The open symbols represent the representative mAbs from each Group. (D) Dose-response curves of mAbs representing each of the Groups (± SD, n = 2). An isotype control mAb (control) was used as negative control.

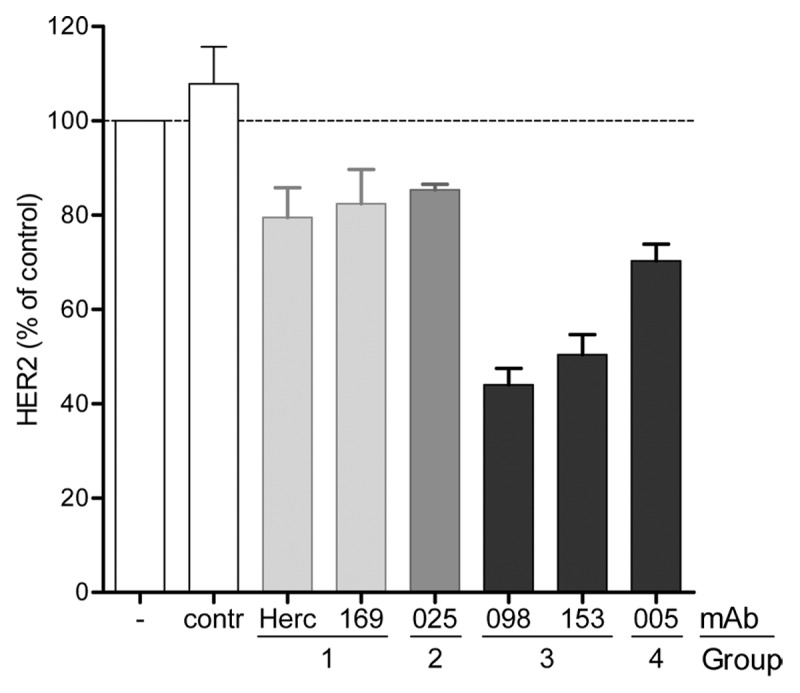

Upon internalization, antibody-target complexes enter the endosomal compartment, and are either transported to the lysosomes for degradation, or are recycled back to the plasma membrane. We investigated for representative mAbs of each cross-competition group whether HER2 mAb binding induced degradation of the HER2 target. The total amount of HER2 protein in AU565 cells was quantified by ELISA after a 3 d antibody treatment. AU565 cells were seeded to confluence at the beginning of the experiment to minimize antibody-induced effects on proliferation. Both Group 3 antibodies induced HER2 downmodulation (~50% of untreated cells; Figure 3). In contrast, Group 1 and 2 antibodies hardly induced any downmodulation, whereas Group 4 antibody 005 induced intermediate HER2 downmodulation. Except for the Group 2 HER2 mAb 025, these data are in line with the internalization results, suggesting that internalization upon HER2 mAb binding results in degradation of the antibody-target complexes for Group 1, Group 3, and Group 4 antibodies. HER2 antibody 025 behaved differently in that it showed internalization comparable to Group 4 mAb 005, but induced limited HER2 downmodulation. This might suggest that the antibody-target complex formed by mAb 025 is primarily directed toward the recycling pathway instead of the lysosomal degradation pathway.

Figure 3. Antibody induced downmodulation of HER2. Relative percentage of HER2 expressed in AU565 cell lysate after 3 d incubation 10 µg/mL HER2 mAb. The amount of HER2 was quantified using a HER2-specific capture ELISA and plotted as a percentage relative to untreated cells indicated with - (± SD, n = 3). An isotype control mAb (contr) was used as negative control.

HER2-mAb activity in an in vitro kappa-directed ETA’ killing assay

To further investigate which antibodies were suitable for an ADC approach, an in vitro cell-based killing assay using the Pseudomonas exotoxin A (ETA’) fused to an anti-kappa light chain domain antibody (α-kappa-ETA’) amenable to high throughput screening was used.23 This fusion protein allows formation of non-covalently-linked immunotoxins with antibodies containing human kappa light chains. The α-kappa-ETA’ fusion protein needs to undergo furin-mediated proteolytic cleavage in the endosomes to separate the catalytic exotoxin part from the antibody binding domain. The released toxin is then transported to the endoplasmic reticulum and redirected to the cytosol where it inhibits protein synthesis and induces apoptosis.24 We investigated whether there was a correlation between the efficiency of antibody-induced internalization, HER2-downmodulation and cytotoxicity mediated by immunotoxins derived from HER2 mAbs of the different cross-competition groups.

We screened our complete panel of 72 HER2 mAbs for inhibition of AU565 cell viability when pre-incubated with α-kappa-ETA’. In general, α-kappa-ETA’ pre-incubated Group 3 and Group 4 antibodies induced higher toxicity (lower cell viability) in AU565 cells compared with α-kappa-ETA’ pre-incubated antibodies from Group 1, including trastuzumab, and Group 2, including TH-pertuzumab, (Fig. 2C). Reduced cell viability was evidently due to cellular toxicity rather than inhibition of proliferation, as effects of unconjugated antibodies on proliferation in the 3 d assay were observed only at concentrations above 100 ng/mL (data not shown), at which α-kappa-ETA’ pre-incubated antibodies already demonstrated maximal efficacy (Fig. 2C). Moreover, microscopic inspection of the cells revealed morphologic characteristics typical for apoptotic cells, such as cell shrinkage, membrane blebbing and loss of membrane asymmetry. The dose-response curves of different mAbs of each cross-competition group again show that Group 1 antibodies induced less efficient cell killing than mAbs from the other cross-competition groups (Fig. 2D). The selected mAb from Group 2 (025) was one of the more effective antibodies from this group and thus also induced efficient dose-dependent cytotoxicity. These results were consistent with internalization data in AU565 cells for each antibody.

The effects of EGFR and its ligand EGF on HER2-mAb α-kappa-ETA’ induced toxicity

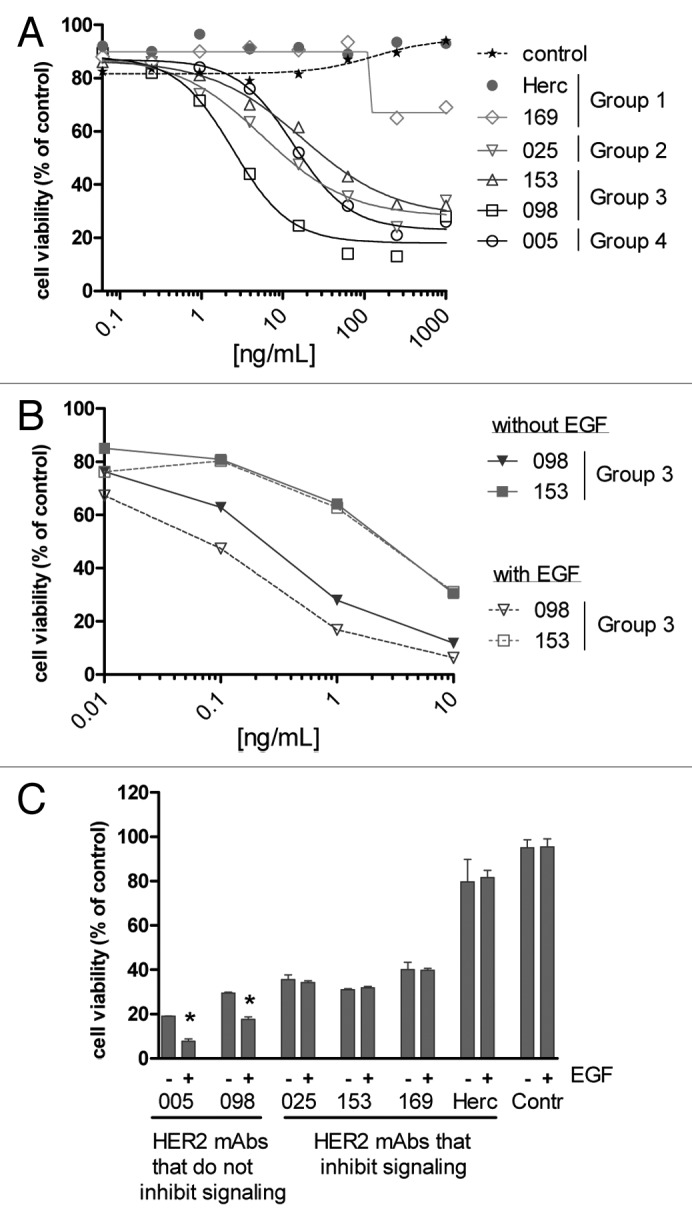

The efficacy of α-kappa-ETA’ pre-incubated HER2 mAbs was further investigated using the low-HER2 expressing cell line A431 (Table S2). After three days, cell viability was efficiently decreased by the Group 2, 3, and 4 antibodies, while Group 1 antibodies demonstrated minimal to no efficacy (Fig. 4A). These results were comparable to what was observed for AU565 cells; however, differences between mAbs from Group 1 and other Groups were much more pronounced in A431. Because A431 cells have very high EGFR expression (Table S2), resulting in EGFR/HER2 heterodimerization,25 we hypothesized that this might accelerate internalization of HER2, thereby increasing cell killing induced via α-kappa-ETA’ pre-incubated HER2 antibodies. Since Group 1 antibodies inhibit ligand-independent dimerization and thus also the formation of EGFR/HER2 heterodimers on A431 cells, these antibodies may not be able to benefit from this internalization route and therefore are reduced in their ability to induce ADC-mediated toxicity. Together, these data might then suggest that high EGFR expression and thus EGFR/HER2 heterodimerization in A431 cells is involved in increased α-kappa-ETA’-mediated cytotoxic efficacy of the HER2 mAbs of Group 2, 3 and 4 compared with AU565 cells with low EGFR expression.

Figure 4. The effect of EGFR and its ligand EGF on HER2-mAb α-kappa-ETA’ induced toxicity. (A) A431 cells were seeded in presence of HER2 antibodies pre-incubated with 0.1 µg/mL α-kappa-ETA’. After 3 d, cell viability was quantified using Alamarblue and plotted as a percentage relative to untreated cells (n = 2). (B, C) Colo 205 cells were seeded in presence or absence of HER2 antibodies pre-incubated with 0.25 µg/mL α-kappa-ETA’. After 30 min 1.5 ng/mL EGF (+) or medium (-) was added and after 3 d, cell viability was quantified using ATPlite and plotted as a percentage relative to untreated cells (n = 2). (C) The amount of viable cells after treatment with HER2 antibody pre-incubated with 0.25 µg/mL α-kappa-ETA’ was plotted. Dark gray bars represent cell viability after treatment with 100 ng/mL HER2 antibody. Increased cell survival after treatment with 10 ng/mL HER2 antibody was plotted as light gray bars. Ten μg/mL Staurosporin was used as positive control to determine 0% cell viability. * indicates that viability in presence of EGF was significantly lower compared with viability in absence of EGF (P < 0.05).

Ligand binding to EGFR typically causes accelerated internalization of the receptor.11,26-30 Therefore, we tested our hypothesis by assessing the cytotoxic capacity of α-kappa-ETA’ pre-incubated HER2 mAbs on Colo205 cells in the absence or presence of EGF. Colo205 cells show low levels of both EGFR and HER2 on the cell surface (Table S2), although the density of both receptors may be somewhat higher than expected due to the small size of these cells. More importantly, Colo205 cells are responsive to EGFR activation by EGF. Results with kappa-ETA’ pre-incubated HER2 mAbs on Colo205 cells in the absence of EGF were comparable to AU565 and A431 cells, i.e., Group 1 mAbs showed less cell killing than the representative mAbs from the other Groups (Fig. 4C). Upon EGF stimulation, only Group 3a HER2 mAb 098 and Group 4 mAb 005 showed enhanced α-kappa-ETA’-mediated cytotoxicity (Fig. 4B and C), whereas EGF did not affect α-kappa-ETA’-mediated cytotoxicity induced by Group 1 or 2 or the Group 3b mAb (153).

These results support our hypothesis that the formation of HER2/ErbB-heterodimers is beneficial for HER2 antibody-mediated drug delivery into target cells. Therefore, antibodies that inhibit the formation of ligand-induced or ligand-independent HER2/ErbB-heterodimers seem less suitable for an ADC approach compared with antibodies that do not interfere with HER2 heterodimerization.

Discussion

In the present study, we characterized a broad panel of human HER2 antibodies generated in human antibody transgenic mice and studied their effects on receptor signaling, internalization and downmodulation of antibody-receptor complexes. To investigate which HER2 antibodies were most suitable for an ADC approach, we used an assay sytem based on a high affinity kappa light chain-specific domain antibody fused to a truncated form of Pseudomonas exotoxin A (α-kappa ETA’).23 Toxicity induced by non-covalently linked toxin/HER2 antibody conjugates was tested on tumor cells with different expression levels of the ErbB receptors. Our results indicated that the formation of HER2/ErbB-heterodimers is beneficial to achieve sufficient HER2 antibody-mediated drug delivery into target cells. Especially on tumor cells that do not overexpress HER2 to extremely high levels, the formation of HER2/ErbB heterodimers may represent an attractive approach for HER2 antibodies to deliver an ADC.

Most ADCs, including ado-trastuzumab emtansine, make use of non-cleavable linkers, or linkers that require proteolytic cleavage in lysosomes for drug release, such as thioether, disulfide and peptide-based valine-citrulline (SGN-35) linkers.8,31 This differs from Pseudomonas exotoxin A-based conjugates, which are cleaved by furin in the endosomes, resulting in separation of the catalytic domain from the antibody-binding domain. Although the kinetics are not entirely understood, it should be noted that rapid lysosomal transport of Pseudomonas exotoxin A-based conjugates may hamper furin mediated cleavage and consequently reduce cytotoxicity.32 Antibodies that deliver kappa-ETA’ more effectively into the lysosome, might therefore induce a lesser degree of killing, because of toxin degradation. The kappa-ETA’ assay could therefore underestimate the potential value of such antibodies for an ADC approach. Nevertheless, in our panel of antibodies, we did not identify antibodies that were ineffective in the kappa-toxin assay while inducing rapid internalization as shown by strong CypHer5E fluorescence (Fig. S3). Furthermore, Pseudomonas exotoxin A has been used by a variety of investigators in preclinical and clinical testing to enhance the efficacy of antibody-based drugs,33-37 e.g., scFv[FRP5]-ETA (single chain Fv directed against HER2),37 VB4–845 (scFv targeting EpCAM),33 SS1P (dsFv directed against mesothelin)36 and CAT-8015 (stabilized Fv fragment targeting CD22).24 Therefore the exotoxin A-based screening system should reliably identify antibodies with favorable characteristics for ADC development.

Based on cross-competition ELISA, HER2 extracellular domain shuffle and CLIPSTM technology, a panel of 72 HER2 antibodies was divided into four different cross-competition groups. It was observed that antibodies from Groups 2, 3 and 4, which did not inhibit ligand-independent HER2 dimerization, induced enhanced internalization and α-kappa-ETA’-mediated cytotoxicity compared with antibodies from Group 1, which inhibited ligand-independent HER2 dimerization. This contrast was most prominent for cells with low HER2 expression but increased EGFR expression (AU565 cells -HER2 high, EGFR low- vs. A431 cells -HER2 low, EGFR high-), demonstrating that toxicity induced by α-kappa-ETA’ pre-incubated Group 1 antibodies, such as trastuzumab, cannot be enhanced via co-expression with EGFR. Due to overexpression of EGFR on A431 cells, internalization of HER2 was mostly driven by the formation of ligand-independent HER2/EGFR heterodimers. Various studies have demonstrated that internalization of HER2 is dependent on expression levels of other ErbB family members, especially EGFR,10,13,38 and that degradation of HER2 could be enhanced through co-expression of EGFR or HER3.14 However, no correlation has been observed thus far between cytotoxicity of anti-HER2 immunotoxins and the relative antibody affinities, epitopes recognized or amount of immunotoxin internalized.39 Also here, no correlation was observed between antibody affinities and toxicity induced in a α-kappa-ETA’ model system. However, a clear correlation was observed between the different HER2 cross-competition groups and the amount of toxicity induced in the α-kappa-ETA’ model system.

Trastuzumab’s ability to inhibit the formation of ligand-independent HER2/HER3 dimers has been described.17 It may very well be that trastuzumab also inhibits formation of ligand-independent EGFR/HER2 dimers. This could explain why antibodies from Groups 2, 3 and 4, which did not disrupt ligand-independent EGFR/HER2 dimerization on A431 cells, still induced efficient killing of these cells. It should be noted, however, that besides differences in ErbB expression levels, other differences caused by the distinct origins of A431 (epithelial carcinoma) and AU565 (breast cancer) may influence the outcome of the results as well. Moreover, Pseudomonas exotoxin A exerts its cytotoxic activity by inhibiting protein synthesis.40 Because Group 3 antibodies enhanced proliferation of high HER2 expressing tumor cells, this may also enhance the cytotoxic effects induced by ETA’. In addition, antibody-induced receptor activation has been demonstrated to enhance endocytic degradation of HER2.41,42 Antibody 005, however, had no effect on HER2-mediated proliferation, but demonstrated enhanced internalization and α-kappa-ETA’-mediated cell killing. This result indicates that receptor crosslinking may be favorable, but not crucial for enhancing receptor internalization.

The relevance of HER2 heterodimerization on internalization of antibody-receptor complexes was further supported by the observation that stimulation with EGF enhanced toxicity of α-kappa-ETA’ pre-incubated HER2 antibodies 005 and 098, which did not inhibit heterodimerization of HER2. Toxicity induced via antibodies 025 and 153, which do inhibit ligand induced HER2 heterodimerization, was unaffected. The observation that EGF-induced activation of HER2 can potentiate the action of a HER2-directed immunotoxin was also observed by Wels et al.43 Notably, toxicity induced by α-kappa-ETA’ pre-incubated antibodies 169 and trastuzumab was also unaffected upon EGF stimulation, supporting the findings that HER2 domain IV may be involved in stabilization of ligand-induced HER2/EGFR heterodimers.44 The possibility that differences observed between clinical grade trastuzumab and other HER2 antibodies were due to differences in the constant antibody domains, was excluded by comparing clinical grade trastuzumab with HEK-293-produced trastuzumab (TH-trastuzumab). No differences in toxicity were observed between the two batches when tested in the α-kappa-ETA’ toxin assay with AU565 cells (Fig. S4).

It is generally believed that trastuzumab drives internalized HER2 away from the recycling pathway toward the lysosomal degradation pathway, although the contribution of this mechanism to the anti-tumor effect of trastuzumab is not fully understood.10-12 We have demonstrated that antibodies that inhibit HER2/EGFR signaling, also showed reduced internalization, as observed with trastuzumab. By using antibodies that do not inhibit HER2 heterodimerization, it was possible to kill lower HER2-expressing tumor cells. This illustrates that the most effective unconjugated antibodies are not necessarily the most effective ADCs. Since HER2 expression and expression of other ErbBs is required to enhance the efficacy of these HER2-ADCs, they may be more tumor-specific while targeting a broader range of tumor indications. In this case, however, we were not able to demonstrate superiority of particular antibody groups in vivo because the non-covalent interaction of α-kappa-ETA’ with IgG does not hold in vivo and covalent conjugation of α-kappa-ETA’ to IgG failed.

In conclusion, these results demonstrate that maximum HER2-ADC delivery and tumor kill requires the formation of HER2/ErbB heterodimers. Therefore, inhibition of receptor signaling seems less favorable for an ADC approach. Especially on low-HER2 expressing tumors, piggybacking with other ErbBs may represent an attractive approach to increase intracellular delivery of an ADC.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies and cell lines

Human MCF7 and AU565 (breast cancer), NCI-H747 and Colo 205 (colon cancer) cells were from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Human A431 (epithelial squamous carcinoma) cells were from the Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen (DSMZ). MCF7 cells were cultured in MEM (Lonza, BE12-169F) containing 10% heat inactivated calf serum (Hyclone, SH30087.04) and 0.01 mg/mL bovine insulin (Sigma, I0516). Colo 205 and A431 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Lonza, BE12-115F) containing 10% heat inactivated calf serum. AU565 and NCI-H747 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640, containing 10% heat inactivated calf serum, 2% sodium bicarbonate (Lonza, BE17-613E), 1% sodium pyruvate (Lonza, BE13-115E), and 0.5% glucose (Sigma, G8769).

Human IgG1,ĸ HER2 mAb were generated by immunizing HuMAb® mice (Medarex)45 alternating with NS0 cells transiently expressing full-length HER2 (1255 aa, UniProt P04626) and a Keyhole Limpet Hemocyanin (KLH)-coupled C-terminal His6-tagged HER2 protein fragment comprising the HER2 extracellular domain (HER2ECDHis). mAb were obtained by fusing mouse splenocytes and lymph node cells with the mouse myeloma cell line SP2.0 (ATCC) by electrofusion using a CEEF 50 Electrofusion System (Cyto Pulse Sciences). Hybridomas were subcloned in semisolid medium using the ClonePix system (Genetix), and expanded and cultured based upon standard protocols.15 Antibodies that bound HER2 expressing cell lines selectively were molecularly cloned and produced by transient transfection in HEK-293 cells, purified using protein A affinity chromatography (MabSelect SuRe, GE-Healthcare) and formulated in PBS containing Tween 80 and mannitol.

The HER2ECDHis constructs contained an optimal Kozak sequence and were cloned in the mammalian expression vector pEE13.4 (Lonza Biologics),46,47 expressed in HEK-293F cells and purified using immobilized metal affinity chromatography. To allow a proper comparison, we also produced trastuzumab and pertuzumab in our transient HEK system. The variable region sequences of pertuzumab and trastuzumab described in US patents 6949245 and 7632924, respectively, were cloned and transfected in HEK-293 cells. Both were expressed as a human IgG1 (allotype f) antibody with a kappa light chain. These two mAb preparations are referred to as TH-pertuzumab and TH-trastuzumab, respectively. Clinical grade trastuzumab (Herceptin®) was purchased (Roche). Trastuzumab and TH-trastuzumab bound HER2 similarly (data not shown) and, as an additional control, Figure S4 illustrates that clinical grade trastuzumab and TH-trastuzumab induced similar efficacy in our in vitro kappa-directed ETA’ killing assay.

Cross-competition ELISA

ELISA plates were coated with HER2 antibodies at 4 °C, 6–0.5 μg/mL. After blocking with PBSTC (PBS supplemented with 0.5% Tween 20 [Riedel-de-Haen, 63158] and 2% chicken serum [Invitrogen, 16110082]) for 1 h at room temperature (RT), wells were incubated with 1 μg/mL soluble HER2ECDHis in the presence of an excess (10 μg/mL) of competitor HER2 antibody. Bound HER2ECDHis was detected with 0.5 μg/mL biotinylated rabbit-anti-6xhis antibody (Abcam, ab27025), followed by 0.1 μg/mL streptavidin-poly-HRP (Sanquin, M2032). The reaction was visualized using ABTS (Roche) and stopped with 0.2% oxalic acid. Fluorescence at 405 nm was measured on a microtiter plate reader (Biotek Instruments) and residual HER2ECDHis binding was expressed as percentage relative to maximal binding observed in absence of competitor antibody.

HER2 ECD domain shuffle

Sequences of domains I–IV of the human HER2 extracellular domain were exchanged one-by-one from human to chicken HER2 (Gallus gallus isoform B NCBI: NP_001038126.1), generating 5 different constructs: (1) fully human HER2 (UniProt P04626), hereafter named hu-HER2; (2) hu-HER2 with chicken domain I (replacing amino acids (aa) 1–203 of human Her2 with the corresponding chicken Her2 region), named hu-HER2-ch(I); (3) hu-HER2 with chicken domain II (replacing amino acids (aa) 204–330 of human Her2 with the corresponding chicken Her2 region), named hu-HER2-ch(II); (4) hu-HER2 with chicken domain III (replacing aa 331–507 of human Her2 with the corresponding chicken Her2 region), named hu-HER2-ch(III); and (5) hu-HER2 with chicken domain IV (replacing aa 508–651 of human Her2 with the corresponding chicken Her2 region), named hu-HER2-ch(IV). The constructs were transiently transfected in FreestyleTM CHO-S (Invitrogen) cells using Freestyle MAX transfection reagent (Invitrogen, K9000-20). After culturing for 20 h, HER2 antibody binding was analyzed by flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry

Binding of HER2 antibodies to membrane-bound HER2 on A431 cells was analyzed by flow cytometry as described.48 Phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated goat anti-human IgG (Jackson, 109-116-098) was used to detect binding of HER2 mAbs. EC50 values were determined by means of nonlinear regression using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software V4.03).

Proliferation assay

AU565 cells were seeded in serum-free culture medium, 9 000 cells per well, in 96-wells tissue culture plates (Greiner bio-one, 655180) in the presence of 10 μg/mL antibody. MCF7 cells were seeded in complete growth medium, 2 500 cells per well. After 4 h, medium was replaced with medium containing 1% serum, 10 μg/mL antibody and 1.5 ng/mL heregulin-β1 (PeproTech, 100-03). After 3 or 4 d incubation, 10% Alamarblue (Invitrogen, DAL110) was added, and fluorescence was monitored 4 h later using the EnVision 2101 Multilabel reader (PerkinElmer). The Alamarblue signal in antibody-treated wells was plotted as a percentage relative to the signal in wells without antibody.

ERK-phosphorylation Alphascreen assay

AU565 cells were cultured overnight in 96-wells plates (9 000 cells per well) in serum-free medium. The medium was replaced with DMEM (Sigma-Aldrich, D6546) and the cells were cultured 2 h. Ten µg/mL antibody dilutions (in DMEM) were added, 30 min prior to stimulation with 1.67 ng/mL EGF (Bioresource, PHG0311). After 10 min, the cells were washed twice with PBS, lysed and analyzed for the presence of phosphorylated ERK with the phospho-ERK specific AlphaScreen® assay, according to the manufacturer’s protocol (PerkinElmer, TGRES500). Fluorescent units at 570 nm were measured with the EnVision 2101 Multilabel reader (PerkinElmer) using standard AlphaScreen® settings.

CypHer5E internalization assay

Cells were seeded in 384-well plates, 3,000 cells/well, in normal cell culture medium, containing 240 ng/mL goat anti-human-IgG Fab fragments (Jackson, 109-007-003) conjugated to CypHer5E (GE Healthcare, PA15401). CypHer5E is a pH-sensitive dye that is non-fluorescent at basic pH (extracellular: culture medium) and fluorescent at acidic pH (intracellular: endosomes, lysosomes). Serially-diluted antibodies (range 2500–4.9 ng/mL) were added and plates were incubated at RT for 9 h. Mean fluorescent intensities (MFI) of intracellular CypHer5E were measured per well using homogeneous Fluorometric Microvolume Assay Technology (FMAT, Applied Biosystems). As read-out, fluorescence per cell was measured and multiplied with the number of positive cells per well (counts × fluorescence).

HER2 downmodulation ELISA

AU565 cells were seeded in 24-wells tissue culture plates (100 000 cells per well) in normal cell culture medium and cultured for 3 d at 37 °C in the presence of 10 μg/mL HER2 antibody. Cells were lysed by incubating 30 min at RT with 25 μL Surefire Lysis buffer (Perkin Elmer, TGRA2510K). Total protein levels were quantified using bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay reagent (Pierce, 23227). HER2 protein levels were analyzed using a HER2-specific sandwich ELISA. A 1000-fold dilution of rabbit anti-human HER2 intracellular domain antibody (Cell Signaling, 2165) was used to capture HER2 and 0.15 μg/mL biotinylated goat anti-human HER2 polyclonal antibody (R&D, BAF1129), followed by 0.1 μg/mL streptavidin-poly-HRP, were used to detect bound HER2. The reaction was visualized using ABTS and stopped with oxalic acid. Fluorescence at 405 nm was measured and the amount of HER2 was expressed as a percentage relative to untreated cells.

Cytotoxicity assay using α-kappa-ETA’ toxin

Antibodies were pre-incubated with a predetermined concentration of α-kappa-ETA’ (see Supplementary Methods for preparation of α-kappa-ETA’)23 that was not toxic for cells. This procedure allows formation of non-covalently linked immunotoxins, obviating the production of chemically conjugated toxins that may vary in toxin content and position of linkage. Cells were seeded in normal cell culture medium in 96-wells tissue culture plates and serially diluted antibodies were added. As negative control, cells were incubated without antibody or with an isotype control antibody. As a positive control for cytotoxicity, 10 μg/mL Staurosporin (Sigma, S6942) was added to cells without antibody. After 3 d, the amount of viable cells was quantified using Alamarblue or ATPlite (PerkinElmer, 6016941), both measured using the EnVision 2101 Multilabel reader. Viability was calculated according to (signal antibody-treated cells - signal positive control) / (signal untreated cells - signal positive control) × 100%.

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were done using GraphPad Prism 5 software. Group data were reported as mean ± SD. Dunett’s test was applied for statistical analysis.

Supplementary Material

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

De Goeij BECG, de Haij S, van den Brink EN, Riedl T, de Jong R, Vink T, Strumane K, Bleeker WK, and Parren PWHI are Genmab employees and own Genmab warrants and/or stock.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- ABTS

2,2'-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid

- ADC

antibody-drug conjugate

- ADCC

antibody dependent cellular cytotoxicity

- BCA

bicinchoninic acid

- CLIPSTM

chemically linked immunogenic peptides on scaffolds

- ECD

extracellular domain

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- ERK

extracellular-signal-regulated kinase

- ETA’

Pseudomonas exotoxin A

- FMAT

fluorometric microvolume assay technology

- HER

human epidermal growth factor receptor

- HRG

heregulin

- KLH

keyhole limpet hemocyanin

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinases

- MAB

monoclonal antibody

- PBSTC

phosphate buffered saline with 0.5% tween 20 and 2% chicken serum

- TH

transient human embryonic kidney 293 cells

- VMD

visual molecular dynamics

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/mabs/article/27705

References

- 1.Graus-Porta D, Beerli RR, Daly JM, Hynes NE. ErbB-2, the preferred heterodimerization partner of all ErbB receptors, is a mediator of lateral signaling. EMBO J. 1997;16:1647–55. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.7.1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tao RH, Maruyama IN. All EGF(ErbB) receptors have preformed homo- and heterodimeric structures in living cells. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:3207–17. doi: 10.1242/jcs.033399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riese DJ, 2nd, Stern DF. Specificity within the EGF family/ErbB receptor family signaling network. Bioessays. 1998;20:41–8. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199801)20:1<41::AID-BIES7>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baselga J, Swain SM. Novel anticancer targets: revisiting ERBB2 and discovering ERBB3. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:463–75. doi: 10.1038/nrc2656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lewis Phillips GD, Li G, Dugger DL, Crocker LM, Parsons KL, Mai E, Blättler WA, Lambert JM, Chari RV, Lutz RJ, et al. Targeting HER2-positive breast cancer with trastuzumab-DM1, an antibody-cytotoxic drug conjugate. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9280–90. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krop IE, Beeram M, Modi S, Jones SF, Holden SN, Yu W, Girish S, Tibbitts J, Yi JH, Sliwkowski MX, et al. Phase I study of trastuzumab-DM1, an HER2 antibody-drug conjugate, given every 3 weeks to patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2698–704. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.A P. F.D.A. Approves a new drug for advanced breast cancer. The New York Times. New York, 2013.

- 8.Senter PD. Potent antibody drug conjugates for cancer therapy. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2009;13:235–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Junttila TT, Li G, Parsons K, Phillips GL, Sliwkowski MX. Trastuzumab-DM1 (T-DM1) retains all the mechanisms of action of trastuzumab and efficiently inhibits growth of lapatinib insensitive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;128:347–56. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1090-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Austin CD, De Mazière AM, Pisacane PI, van Dijk SM, Eigenbrot C, Sliwkowski MX, Klumperman J, Scheller RH. Endocytosis and sorting of ErbB2 and the site of action of cancer therapeutics trastuzumab and geldanamycin. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:5268–82. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-07-0591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yarden Y, Sliwkowski MX. Untangling the ErbB signalling network. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:127–37. doi: 10.1038/35052073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Longva KE, Pedersen NM, Haslekås C, Stang E, Madshus IH. Herceptin-induced inhibition of ErbB2 signaling involves reduced phosphorylation of Akt but not endocytic down-regulation of ErbB2. Int J Cancer. 2005;116:359–67. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sorkin A, Goh LK. Endocytosis and intracellular trafficking of ErbBs. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314:3093–106. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pedersen NM, Breen K, Rødland MS, Haslekås C, Stang E, Madshus IH. Expression of epidermal growth factor receptor or ErbB3 facilitates geldanamycin-induced down-regulation of ErbB2. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:275–84. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yokoyama WM. Production of monoclonal antibodies. Curr Protoc Cytom. 2006;3(Appendix):3J. doi: 10.1002/0471142956.cya03js37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cho HS, Mason K, Ramyar KX, Stanley AM, Gabelli SB, Denney DW, Jr., Leahy DJ. Structure of the extracellular region of HER2 alone and in complex with the Herceptin Fab. Nature. 2003;421:756–60. doi: 10.1038/nature01392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Junttila TT, Akita RW, Parsons K, Fields C, Lewis Phillips GD, Friedman LS, Sampath D, Sliwkowski MX. Ligand-independent HER2/HER3/PI3K complex is disrupted by trastuzumab and is effectively inhibited by the PI3K inhibitor GDC-0941. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:429–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Franklin MC, Carey KD, Vajdos FF, Leahy DJ, de Vos AM, Sliwkowski MX. Insights into ErbB signaling from the structure of the ErbB2-pertuzumab complex. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:317–28. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(04)00083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landgraf R. HER2 therapy. HER2 (ERBB2): functional diversity from structurally conserved building blocks. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:202. doi: 10.1186/bcr1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teeling JL, Mackus WJ, Wiegman LJ, van den Brakel JH, Beers SA, French RR, van Meerten T, Ebeling S, Vink T, Slootstra JW, et al. The biological activity of human CD20 monoclonal antibodies is linked to unique epitopes on CD20. J Immunol. 2006;177:362–71. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Weers M, Tai YT, van der Veer MS, Bakker JM, Vink T, Jacobs DC, Oomen LA, Peipp M, Valerius T, Slootstra JW, et al. Daratumumab, a novel therapeutic human CD38 monoclonal antibody, induces killing of multiple myeloma and other hematological tumors. J Immunol. 2011;186:1840–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agus DB, Akita RW, Fox WD, Lewis GD, Higgins B, Pisacane PI, Lofgren JA, Tindell C, Evans DP, Maiese K, et al. Targeting ligand-activated ErbB2 signaling inhibits breast and prostate tumor growth. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:127–37. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(02)00097-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kellner C, Bleeker WK, Lammerts van Bueren JJ, Staudinger M, Klausz K, Derer S, Glorius P, Muskulus A, de Goeij BE, van de Winkel JG, et al. Human kappa light chain targeted Pseudomonas exotoxin A--identifying human antibodies and Fab fragments with favorable characteristics for antibody-drug conjugate development. J Immunol Methods. 2011;371:122–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2011.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kreitman RJ. Recombinant immunotoxins containing truncated bacterial toxins for the treatment of hematologic malignancies. BioDrugs. 2009;23:1–13. doi: 10.2165/00063030-200923010-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brennan PJ, Kumagai T, Berezov A, Murali R, Greene MI. HER2/neu: mechanisms of dimerization/oligomerization. Oncogene. 2000;19:6093–101. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cao Z, Wu X, Yen L, Sweeney C, Carraway KL., 3rd Neuregulin-induced ErbB3 downregulation is mediated by a protein stability cascade involving the E3 ubiquitin ligase Nrdp1. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:2180–8. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01245-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sundvall M, Korhonen A, Paatero I, Gaudio E, Melino G, Croce CM, Aqeilan RI, Elenius K. Isoform-specific monoubiquitination, endocytosis, and degradation of alternatively spliced ErbB4 isoforms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:4162–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708333105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baulida J, Carpenter G. Heregulin degradation in the absence of rapid receptor-mediated internalization. Exp Cell Res. 1997;232:167–72. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baulida J, Kraus MH, Alimandi M, Di Fiore PP, Carpenter G. All ErbB receptors other than the epidermal growth factor receptor are endocytosis impaired. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5251–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.9.5251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wiley HS, Herbst JJ, Walsh BJ, Lauffenburger DA, Rosenfeld MG, Gill GN. The role of tyrosine kinase activity in endocytosis, compartmentation, and down-regulation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:11083–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chiron MF, Fryling CM, FitzGerald DJ. Cleavage of pseudomonas exotoxin and diphtheria toxin by a furin-like enzyme prepared from beef liver. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:18167–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weldon JE, Pastan I. A guide to taming a toxin--recombinant immunotoxins constructed from Pseudomonas exotoxin A for the treatment of cancer. FEBS J. 2011;278:4683–700. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08182.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.MacDonald GC, Rasamoelisolo M, Entwistle J, Cuthbert W, Kowalski M, Spearman MA, Glover N. A phase I clinical study of intratumorally administered VB4-845, an anti-epithelial cell adhesion molecule recombinant fusion protein, in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Med Oncol. 2009;26:257–64. doi: 10.1007/s12032-008-9111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wayne AS, Kreitman RJ, Findley HW, Lew G, Delbrook C, Steinberg SM, Stetler-Stevenson M, Fitzgerald DJ, Pastan I. Anti-CD22 immunotoxin RFB4(dsFv)-PE38 (BL22) for CD22-positive hematologic malignancies of childhood: preclinical studies and phase I clinical trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1894–903. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Biggers K, Scheinfeld N. VB4-845, a conjugated recombinant antibody and immunotoxin for head and neck cancer and bladder cancer. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2008;10:176–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hassan R, Bullock S, Premkumar A, Kreitman RJ, Kindler H, Willingham MC, Pastan I. Phase I study of SS1P, a recombinant anti-mesothelin immunotoxin given as a bolus I.V. infusion to patients with mesothelin-expressing mesothelioma, ovarian, and pancreatic cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5144–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.von Minckwitz G, Harder S, Hövelmann S, Jäger E, Al-Batran SE, Loibl S, Atmaca A, Cimpoiasu C, Neumann A, Abera A, et al. Phase I clinical study of the recombinant antibody toxin scFv(FRP5)-ETA specific for the ErbB2/HER2 receptor in patients with advanced solid malignomas. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7:R617–26. doi: 10.1186/bcr1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hendriks BS, Opresko LK, Wiley HS, Lauffenburger D. Quantitative analysis of HER2-mediated effects on HER2 and epidermal growth factor receptor endocytosis: distribution of homo- and heterodimers depends on relative HER2 levels. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:23343–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300477200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boyer CM, Pusztai L, Wiener JR, Xu FJ, Dean GS, Bast BS, O’Briant KC, Greenwald M, DeSombre KA, Bast RC., Jr. Relative cytotoxic activity of immunotoxins reactive with different epitopes on the extracellular domain of the c-erbB-2 (HER-2/neu) gene product p185. Int J Cancer. 1999;82:525–31. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19990812)82:4<525::AID-IJC10>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pastan I, FitzGerald D. Pseudomonas exotoxin: chimeric toxins. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:15157–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klapper LN, Vaisman N, Hurwitz E, Pinkas-Kramarski R, Yarden Y, Sela M. A subclass of tumor-inhibitory monoclonal antibodies to ErbB-2/HER2 blocks crosstalk with growth factor receptors. Oncogene. 1997;14:2099–109. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guillemard V, Nedev HN, Berezov A, Murali R, Saragovi HU. HER2-mediated internalization of a targeted prodrug cytotoxic conjugate is dependent on the valency of the targeting ligand. DNA Cell Biol. 2005;24:350–8. doi: 10.1089/dna.2005.24.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wels W, Beerli R, Hellmann P, Schmidt M, Marte BM, Kornilova ES, Hekele A, Mendelsohn J, Groner B, Hynes NE. EGF receptor and p185erbB-2-specific single-chain antibody toxins differ in their cell-killing activity on tumor cells expressing both receptor proteins. Int J Cancer. 1995;60:137–44. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910600120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wehrman TS, Raab WJ, Casipit CL, Doyonnas R, Pomerantz JH, Blau HM. A system for quantifying dynamic protein interactions defines a role for Herceptin in modulating ErbB2 interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19063–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605218103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fishwild DM, O’Donnell SL, Bengoechea T, Hudson DV, Harding F, Bernhard SL, Jones D, Kay RM, Higgins KM, Schramm SR, et al. High-avidity human IgG kappa monoclonal antibodies from a novel strain of minilocus transgenic mice. Nat Biotechnol. 1996;14:845–51. doi: 10.1038/nbt0796-845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kozak M. Initiation of translation in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Gene. 1999;234:187–208. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(99)00210-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bebbington CR, Renner G, Thomson S, King D, Abrams D, Yarranton GT. High-level expression of a recombinant antibody from myeloma cells using a glutamine synthetase gene as an amplifiable selectable marker. Biotechnology (N Y) 1992;10:169–75. doi: 10.1038/nbt0292-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lammerts van Bueren JJ, Bleeker WK, Bøgh HO, Houtkamp M, Schuurman J, van de Winkel JG, Parren PW. Effect of target dynamics on pharmacokinetics of a novel therapeutic antibody against the epidermal growth factor receptor: implications for the mechanisms of action. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7630–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.