Abstract

Background

Alcohol potentiates GABAergic neurotransmission via action at the GABAA receptor. α1 subunit-containing GABAA receptors have been implicated as mediators, in part, of the behavioral and abuse-related effects of alcohol in rodents.

Methods

We systematically investigated the effects of one α1-preferring benzodiazepine agonist, zolpidem, and two antagonists, βCCT and 3-PBC, on oral self-administration of alcohol (2% w/v) or sucrose solution and observable behavior in rhesus macaques. We compared these effects to those of the nonselective benzodiazepine agonist triazolam, antagonist flumazenil, and inverse agonist βCCE.

Results

Alcohol and sucrose solutions maintained reliable baseline drinking behavior across the study. The α1-preferring compounds did not affect intake, number of sipper extensions, or blood alcohol levels at any of the doses tested. Zolpidem, βCCT, and 3-PBC increased latency to first sipper extension in animals self-administering alcohol, but not sucrose, solution. Triazolam exerted biphasic effects on alcohol drinking behavior, increasing intake at low doses but decreasing BAL and increasing latency at higher doses. At doses higher than those effective in alcohol-drinking animals, triazolam increased sucrose intake and latency. Flumazenil non-systematically increased number of extensions for alcohol but decreased BAL, with no effects on sucrose drinking. βCCE decreased sipper extensions for alcohol and increased latency for first sucrose sipper extension, but full dose-effect relationships could not be determined due to seizures at higher doses.

Conclusions

Alcohol-drinking animals appeared more sensitive to the effects of GABAergic compounds on drinking behavior. However, these results do not support a strong contribution of α1GABA receptors to the reinforcing effects of alcohol in primates.

Keywords: GABAA receptors, alcohol, self-administration, monkey, pharmacotherapy

INTRODUCTION

Alcohol abuse and dependence are highly prevalent and problematic for society, yet at this time, there are no universally effective FDA-approved pharmacotherapies available to treat alcohol abuse and dependence. The behavioral effects of alcohol are due, in part, to its potentiating actions at the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)A receptor (Boehm et al., 2004, Kumar et al., 2009). The GABAA receptor is a pentamer consisting of different subunits from eight different families, with the most abundant form in the mammalian brain composed of a combination of α, β, and γ subunits (Sieghart and Sperk, 2002). Each of these subunits exists in multiple isoforms (e.g., α 1–6, β1–3, γ1–3). The α-subunit subtypes in particular may contribute differentially to the diverse behavioral and abuse-related effects of alcohol (Boehm et al., 2004), which raises the possibility for development of targeted therapeutic compounds to treat alcohol dependence. For example, we have demonstrated recently a critical role for α5GABAA subunit-containing receptors in alcohol drinking in monkeys (Ruedi-Bettschen et al., 2013); however, the role of the other α-subunit containing receptors remains to be explored in this model.

α1GABAA subunit-containing receptors are widely expressed and comprise the most abundant form of GABAA receptors in the brain (Sieghart and Sperk, 2002, Pirker et al., 2000). Recently, studies have suggested an important role for this receptor subtype in mediating the abuse-related effects of alcohol. Mice lacking the α1GABAA receptor subunit show reduced preference for alcohol (Blednov et al., 2003), while systemic injection of α1GABAA receptor-preferring benzodiazepine-type antagonists is able to attenuate alcohol, but not sucrose, self-administration in rats (Harvey et al., 2002). In addition, microinfusions of α1GABAA receptor-preferring antagonists into the amygdala and ventral pallidum, but not the caudate-putamen or nucleus accumbens of rats, also produce this attenuation (Foster et al., 2004, Harvey et al., 2002, June et al., 2003). Interestingly, mice with alcohol-insensitive α1GABAA receptors showed no alteration in alcohol consumption or preference (Werner et al., 2006), suggesting that the effects of α1GABAA receptor modulation reported in previous rodent studies may indeed be due to action at the benzodiazepine, and not the alcohol, binding site on these receptors. However, genetic studies in humans only report a link between the gene encoding the α1 subunit and a high reward-dependent phenotype and not specifically alcoholism (Dick et al., 2002, Song et al., 2003). Furthermore, α1GABAA receptor-preferring benzodiazepine-type antagonists are unable to block the discriminative stimuli of alcohol in squirrel monkeys, although α1GABAA receptor-preferring agonists are able to partially or fully substitute, but likely through a non-α1 mechanism (Platt et al., 2005). Together, these studies suggest that α1GABAA subunit-containing receptors contribute to alcohol’s abuse-related effects, although the relationship is complex.

Therefore, in the present study, we hypothesized that α1GABAA receptor modulation may be able to selectively alter alcohol-drinking behavior such that selective agonists would increase and selective antagonists would decrease (or functionally attenuate) drinking. To elucidate the relationship between modulation of this receptor subtype and drinking, we evaluated an α1GABAA receptor-preferring benzodiazepine agonist and two antagonists for selective effects on alcohol drinking using a rhesus monkey model (Ruedi-Bettschen et al., 2013) and compared them with a nonselective benzodiazepine agonist, antagonist, and inverse agonist. As α1GABAA receptors also have been implicated in mediating the ataxic effects of alcohol (Boehm et al., 2004, June et al., 2003), we conducted behavioral observations in order to assess the behavioral effects of the different compounds following alcohol or sucrose drinking sessions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Eleven adult male rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta), weighing between 9–14 kg, served as subjects. Monkeys were individually housed in a colony room with a 12:12hr light/dark cycle and were fed monkey chow (Harlan Teklad Monkey Diet, Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI) once daily after the conclusion of the day’s experimental session. Diets were supplemented with fresh fruit. Each animal received an additional two chow biscuits after the second hour of the three hour daily drinking session. Six monkeys participated in the alcohol self-administration studies and a separate cohort of 5 monkeys participated in the sucrose self-administration studies. All animals had been previously trained to self-administer alcohol or sucrose using an operant panel (Vallender et al., 2010, Ruedi-Bettschen et al., 2013). The sole exception was one sucrose drinker who had prior experience in operant i.v. cocaine self-administration procedures and was naïve to the oral self-administration procedures. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Committee on Animals of the Harvard Medical School and the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Publication No. (NIH) 85-23, revised 1996). Research protocols were approved by the Harvard Medical School Animal Care and Use Committee.

Self-administration procedures

Drinking sessions occurred 5 days per week in the animal’s home cage. Each session lasted 3 hours. Access to water (via the standard cage-associated sipper) was restricted beginning 1 hour prior to the start of the day’s experimental session and restored 1 hour post-session. Animals were trained to drink either alcohol (2%, w/v; n = 6) or sucrose solution (0.3 or 1%, w/v, depending on the animal; n = 5) using an operant drinking panel mounted on the side of the home cage. The alcohol concentration was chosen because it maintained intake significantly above water levels and is on the ascending limb of the concentration-effect curve (see Ruedi-Bettschen et al., 2013), thus allowing us to detect either increases or decreases in drinking. The sucrose concentrations were chosen because they maintained approximately equivalent levels of intake to ethanol under baseline conditions.

The panel contained two retractable sippers (Med Associates, Inc., Georgia, VT) equipped with solenoids to minimize dripping and connected with tygon tubing to stainless steel reservoirs mounted outside of the cage. A response lever (Med Associates) was positioned below each sipper and a set of colored lights positioned above. Each lever press resulted in an audible click and served as a response. In these experiments, only one side of the panel was active. Daily, illumination of white lights signaled the start of the session and alcohol or sucrose availability. Every 10 responses resulted in a switch from illumination of the white light to illumination of a red light and extension of the drinking spout for 30s. Depression of the spout during extension resulted in fluid delivery, continuing as long as the sipper was both depressed and extended. Thus, both the actual duration (up to 30s) and volume of intake were controlled by the subject. A brief (1 s) time out followed each spout extension, in which all stimulus lights were dark and responding had no programmed consequences. Responses were recorded and outputs controlled by a software program (MedPC, Med Associates). At the end of each session, reservoirs were drained and the amount of liquid consumed (mls) measured.

Experimental compounds were administered as an intramuscular pretreatment 10 min before the start of a self-administration session. A range of doses was studied for each compound. Each dose of each compound was studied for a minimum of 5 consecutive sessions and until intake was stable, which was defined as no upward or downward trend in amount consumed (mls) over three consecutive days. Following evaluation of each dose, monkeys were returned to baseline self-administration conditions (i.e, with no pretreatment injection) until intake stabilized again. Doses were randomized within each treatment condition and all doses of a particular compound were generally completed before beginning a new compound.

Observable behavior

The behavior of each monkey was recorded for 5 min each day immediately following the conclusion of the day’s self-administration session, using a focal animal approach as described in Platt et al., (2000, 2002) and modified for the rhesus monkey (see Ruedi-Bettschen et al., 2013; Table 1). Briefly, a trained observer blind to the drug treatments watched a specific monkey for 5 minutes and recorded each instance that a particular behavior (as defined in Ruedi-Bettschen et al., 2013; Table 1) occurred during 15-second intervals. Scores for each behavior were calculated as the number of 15-second bins in which the behavior occurred (e.g. a maximum score would be 20). The order in which animals were observed and the observer performing the scoring each day was randomized. Twelve observers participated in the scoring throughout the duration of the study; each observer underwent a minimum of 20 hours of training and met an inter-observer reliability criterion of ≥90% agreement with all other observers.

Table 1.

Behavioral categories, abbreviations, and definitionsa.

| SPECIES-TYPICAL: | ||

| Passive visual | (VIS) | Animal is standing or sitting motionless with eyes open |

| Rest/Sleep posture | (RSP) | Idiosyncratic posture adopted by monkeys during rest or sleep; eyes closed, easily roused by external stimulation (e.g., tapping on cage) |

| Locomotion | (LOC) | At least two directed steps in the horizontal and/or vertical plane |

| Tactile/oral exploration | (TAC) | Any tactile or oral manipulation of the cage or environment |

| Forage | (FOR) | Sweeping and/or picking through wood chip substrate |

| Self-groom | (GRM) | Picking, scraping, spreading or licking of an animal’s own hair |

| Scratch | (SCR) | Vigorous strokes of the hair with the finger or toenails |

| Vocalization | (VOC) | Species-typical sounds emitted by monkey (not differentiated into different types) |

| Yawn | (YWN) | To open mouth wide and expose teeth |

| Present | (PRE) | Posture involving presentation of rump, belly, flank, and/or neck) to observer or other monkey |

| Threat/aggress | (THR) | Multifaceted display involving one or more of the following: open mouth stare with teeth partially exposed, eyebrows lifted, ears flattened or flapping, rigid body posture, piloerection, attack (e.g., biting, slapping) of inanimate object or other monkey |

| Fear grimace | (FGR) | Grin-like facial expression involving the retraction of the lips exposing clenched teeth; may be accompanied by flattened ears, stiff, huddled body posture, screech/chattering vocalizations |

| Body spasm | (BSP) | An involuntary twitch or shudder of the entire body; also “wet dog” shake |

| Lip smack | (LIP) | Pursing the lips and moving them together to produce a smacking sound; often accompanied by moaning |

| Cage shake | (CSH) | Any vigorous shaking of the cage that may or may not make noise |

| Stereotypy | (STY) | Any repetitive, ritualized pattern of behavior that serves no obvious function |

| Other | (OTH) | Any notable behavior not indicated above (e.g., masturbation, nose rub, lip droop, vomit/retch) |

| PROCEDURE-RELATED: | ||

| Lever press | (LVR) | Depression of lever manipulanda on the drinking panel |

| Drink | (DRI) | Mouth contact to fluid delivery sippers |

| DRUG-INDUCED: | ||

| Ataxia | (ATX) | Any slip, trip, fall or loss of balance |

| Procumbent posture | (PRO) | Loose-limbed posture (sitting or lying on cage bottom) accompanied by eye closure; not easily aroused by external stimulation (e.g., tapping on cage) |

Adapted from Ruedi-Bettschen et al., 2013; Novak et al., 1992; Weerts et al., 1998; Platt et al., 2000, 2002

Blood alcohol levels (BALs)

BALs were determined for monkeys self-administering alcohol once stable self-administration was achieved at each dose of the drug treatments. Monkeys were anesthetized with ketamine (10 mg/kg, i.m.) immediately following the day’s self-administration and behavioral observation sessions and 3–5 mls of blood collected in a sterile 10ml tube (BD Vacutainer, sodium heparin 158 USP, BD Franklin Lakes, NJ USA) from the femoral vein. Samples were then centrifuged at 3200 rmp for 8–12 minutes. The plasma was transferred to polypropylene tubes and frozen at −80C for later analysis. Analysis was conducted using a rapid high performance plasma alcohol analysis using alcohol oxidase with an AM1 series analyzer and Analox Kit GMRD-113 (Analox Instruments USA, Lunenberg, MA). This process reliably detects BALs ranging from 0 – 350 mg/dl with an internal standard of 100 mg/dl. BALs were determined in triplicate.

Drugs

Alcohol (95%; Pharmco Products. Brookfield, CT) was diluted to 2% w/v using tap water. Sucrose solutions were also prepared using tap water. The short-acting, nonselective benzodiazepine agonist triazolam (Huang et al., 2000, Ziegler et al., 1983), and the α1GABAA -preferring agonist zolpidem (Crestani et al., 2000) were obtained from Sigma/RBI., St. Louis, MO. The nonselective benzodiazepine antagonist flumazenil (Hunkeler et al., 1981), α1GABAA-preferring antagonist b-carboline-3-carboxylate-tert-butyl ester (βCCT)(Yin et al., 2010, Cox et al., 1995), and nonselective benzodiazepine inverse agonist ethyl β-carboline carboxylate (βCCE)(Cowen et al., 1981) were either purchased from Sigma/RBI or provided by Dr. Jim Cook. The α1GABAA -preferring antagonist 3-propoxy-β-carboline hydrochloride (3-PBC) was provided by Dr. Cook (Yin et al., 2010). All drugs were administered via intramuscular injection. All drugs except 3-PBC and βCCE were dissolved in propylene glycol and then diluted to desired concentration using a 50% propylene glycol, 50% sterile water solution. 3-PBC required ethanol in order to be solubilized (final concentration 10% ethanol, 50% propylene glycol, 40% sterile water) while βCCE was dissolved in a 20% emulphor, 10% ethanol, and 70% water vehicle.

Doses for triazolam (0.001–1.0 mg/kg), zolpidem (0.1 – 10.0 mg/kg), βCCT (0.3–3.0 mg/kg), and 3-PBC (0.03–10.0 mg/kg) were chosen based on previous studies in squirrel monkeys (Lelas et al., 2002, Rowlett et al., 2003, Platt et al., 2002). Flumazenil doses (0.01–10 mg/kg) were chosen based on the dose range needed to shift the ethanol dose-response function in cynomolgous macaques (Helms et al., 2009). βCCE doses (0.3–3.0 mg/kg) were chosen based on previous studies (e.g. McMahon et al., 2006) but tests were halted at the appearance of seizures in one animal (see Results.) The appearance of behavioral effects in the observational measures was considered in determining doses for all compounds.

Data analysis

The alpha level for all statistical analyses was set at 0.05. Daily volumes (mls) served as the measure of intake for individual subjects. Dose was calculated as: [volume consumed (mls) × alcohol concentration (g/ml)]/weight (kg). Data are expressed as mean intake over three sessions. To compare the effects of the test compounds on alcohol and sucrose self-administration, intakes were converted to percent baseline intake. Baseline intake was considered to be the mean amount of alcohol or sucrose consumed across the three days immediately prior to beginning pretreatment tests with a given dose of a compound. Separate one-way repeated measures ANOVAs followed by Bonferroni t-tests compared the effects of the pretreatment drugs to the effect of vehicle on intake and BALs.

Given that self-administration sessions lasted 3 hours, we also characterized the pattern of drinking within session using latency to first sipper extension and total number of sipper extensions. Latencies and sipper extensions were recorded by the MedPC software system (MedAssociates, St Albans, VT, USA) and later extracted manually from each day’s data file using cumulative records generated by SoftCR software (MedAssociates). Latencies and extensions are expressed as mean latency or extensions across the treatment and compared using separate one-way repeated measures ANOVAs followed by Bonferroni t-tests to evaluate the effects of the pretreatment drugs compared to vehicle.

Frequency scores for each observed behavior were averaged separately for the alcohol and sucrose groups and plotted as a function of dose for each of the α1GABAA-preferring compounds. Normally-distributed data (as determined by the Shaprio-Wilk test) were analyzed using a separate one-way repeated measures ANOVA (within group factor: dose) for each behavior. Bonferroni-corrected post hoc t-tests were used where appropriate.

RESULTS

Drinking behavior

Baseline drinking behavior

The data for this study were collected over a 3–4 year period depending on the animal. All animals reliably self-administered consistent amounts of alcohol or sucrose during the baseline periods preceding each drug test, with no differences in intake across the different treatment baseline periods within individual, except for two individuals (Table 2). For these individuals, differences in baseline were not systematic and post-hoc tests indicated significant differences in only one to three comparisons. In addition, there were no significant differences in the quantity consumed between the alcohol and sucrose groups (Table 2). Under vehicle conditions, monkeys regularly drank to BALs over 80 mg/dl, which would be considered over the legal driving limit in humans (zolpidem veh: 82.8 ± 9.4 mg/dl; βCCT veh: 93.6 ± 6.1 mg/dl; 3-PBC veh: 99 ± 20.4 mg/dl; triazolam veh: 88.1 ± 13.6 mg/dl; flumazenil 87.6 ±9.3 mg/dl; βCCE veh: 97.8 ± 8.3 mg/dl). There were no significant differences in BALs across the difference vehicle conditions.

Table 2.

Average baseline intake for each monkey across the duration of the study. Values are presented as mean (standard error).

| Monkey | Group | Average intake (mls) |

Average intake (g/kg) |

p-value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MM-98 | Alcohol | 730.1 (24.9) | 1.3 (0.05) | 0.12 |

| MM-71 | Alcohol | 629.4 (43.2) | 1.2 (0.09) | 0.009* |

| MM-267 | Alcohol | 902.8 (44.2) | 1.5 (0.09) | 0.138 |

| MM-247 | Alcohol | 606.0 (30.1) | 1.6 (0.08) | 0.059 |

| MM-162 | Alcohol | 652.6 (20.9) | 1.3 (0.04) | 0.314 |

| MM-33 | Alcohol | 821.5 (35.5) | 1.5 (0.06) | 0.495 |

| MM-488 | Sucrose | 512.3 (29.8) | N/A | 0.559 |

| MM-201 | Sucrose | 720.4 (46.9) | N/A | 0.101 |

| MM-106 | Sucrose | 1612 (177.6) | N/A | 0.001** |

| MM-167 | Sucrose | 684.3 (56.3) | N/A | 0.061 |

| MM-354 | Sucrose | 554.7 (64.9) | N/A | 0.393 |

| Ethanol group total | 723.74 (48.1) | |||

| Sucrose group total | 816.9 (202.7) | 0.637 | ||

p-value reflects results of one-way ANOVAs for individual animals and results of t-test for group value

N/A: not applicable

post-hoc tests indicate significant difference between 3-PBC and triazolam baseline intake

post-hot tests indicate significant difference in flumazenil versus βCCT, 3-PBC, and triazolam baseline intakes

α1-preferring compounds

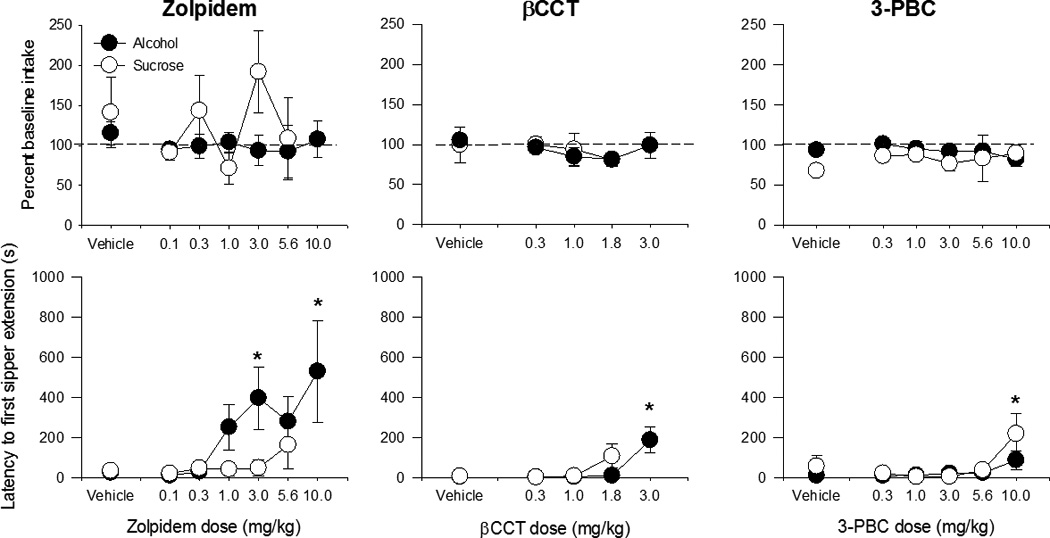

The effects of all α1-preferring compounds on drinking behavior are summarized in Table 3. Daily pretreatment with the α1-preferring agonist zolpidem (0.1 – 10.0 mg/kg), or the α1-preferring antagonists βCCT (0.3–3.0 mg/kg) and 3-PBC (0.03–10.0 mg/kg), did not result in significant alterations in alcohol intake (Fig 1 top, closed symbols), BALs, or number of sipper extensions compared to vehicle at any of the doses tested (Table 3). However, all three of the drugs increased latency to first sipper extension for alcohol (Fig 1 bottom; zolpidem: F(6,23)=4.06, p< 0.01; βCCT: F(4,19)= 7.51, p <0.001; 3-PBC: F(5,25)= 3.13, p < 0.05). Post-hoc tests indicated that zolpidem significantly increased latency at 3.0 (in 4/5 monkeys) and 10.0 mg/kg (in 3/3 monkeys tested at this dose), while 3-PBC significantly increased latency at 10mg/kg (6/6 monkeys) and βCCT significantly increased latency at 3.0 mg/kg (6/6 monkeys). Similarly, none of the compounds affected sucrose drinking behavior (Fig 1 top, open symbols; Table 3), indicating that the effects of the α1GABAA-preferring drugs on latency are specific to alcohol under the current conditions.

Table 3.

The effects of benzodiazepine-type compounds on alcohol and sucrose drinking parameters. Direction of significant effects are indicated by ↓ (decrease), ↑ (increase) or = (no change). Doses at which significant effects occur are indicated in parentheses and reported in mg/kg.

| α1-preferring compounds | Nonselective compounds | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zolpidem | 3-PBC | βCCT | Triazolam | Flumazenil | βCCE | ||

|

Ethanol |

Intake | = | = | = | ↑(0.003) | = | ↓ (0.3) |

| Extensions | = | = | = | = | ↑ (3.0) | ↓ (0.18)* | |

| Latency | ↑ (3.0, 10.0) | ↑ (10.0) | ↑ (3.0) | ↑ (0.056) | = | =* | |

| BAL | = | = | = | ↓ (0.056) | ↓ (1.0, 3.0) | =* | |

| Sucrose | Intake | = | = | = | ↑ (0.1) | = | = |

| Extensions | = | = | = | = | = | = | |

| Latency | = | = | = | ↑ (0.56) | = | ↑ (0.3) | |

No blood draws, extensions, or latency recorded for 0.3 mg/kg due to presence of seizures

Figure 1.

The effects of varying doses of α1GABAA-preferring compounds on intake (top) and latency to first sipper extension (bottom) for alcohol (closed symbols) and sucrose (open symbols). None of the α1GABAA-preferring compounds significantly affected intake for either alcohol or sucrose. * indicates p < 0.05 compared to respective vehicle baseline.

Nonselective benzodiazepine compounds

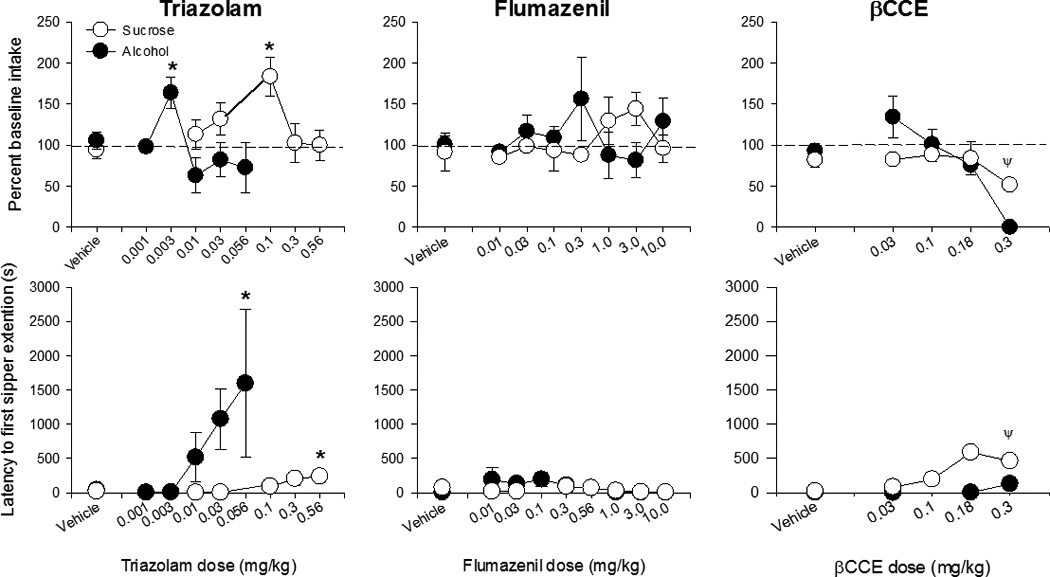

The effects of all nonselective compounds on drinking behavior are summarized in Table 3. Daily pretreatment with the nonselective benzodiazepine agonist triazolam (0.001–1.0 mg/kg) resulted in significant increases in alcohol intake (Fig 2 top, closed symbols; F(5,23)= 4.91, p<0.005) at 0.003 mg/kg (5/6 monkeys), but significantly increased latency to first sipper extension (Fig 2 bottom; F(5,23) = 2.66, p<0.05; 5/5 monkeys) and decreased end-of-session BAL (veh: 88.1 ±13.6 mg/dL, triazolam: 27.3±12.4 mg/dL; F(5,20) = 3.29, p < 0.05; 4/5 monkeys) at the higher dose of 0.056 mg/kg. Triazolam also significantly affected measures of sucrose drinking behavior at higher doses than those that affected alcohol drinking, increasing sucrose intake (Fig 2 top, closed symbols; F(5,17) = 3.66, p<0.05) at 0.1 mg/kg (4/5 monkeys) and latency to first sipper extensions (Fig 2 bottom; F(5,17) = 5.26, p<0.005) at 0.56 mg/kg (5/5 monkeys). No effects on number of sipper extensions for either alcohol or sucrose were seen at the doses tested (Table 3).

Figure 2.

The effects of varying doses of nonselective benzodiazepine compounds on intake (top) and latency to first sipper extension (bottom) for alcohol (closed symbols) and sucrose (open symbols). None of the α1GABAA-preferring compounds significantly affected intake for either alcohol or sucrose. * indicates p < 0.05 compared to respective vehicle baseline. Ψ indicates data for 0.3 mg/kg βCCE was not included in statistical analyses due to the presence of seizures in one animal at this dose.

Daily pretreatment with the nonselective benzodiazepine antagonist flumazenil (0.01–10 mg/kg) did not significantly affect ethanol intake or latency to first sipper extension (Fig 2, center), but increased the number of extensions (F(7,26) = 2.68, p<0.05) at 3.0 mg/kg (5/5 monkeys) and decreased overall BAL (F(7,19) = 4.38, p=0.005) at 1.0 and 3.0 mg/kg, albeit non-systematically (veh: 87.6 ± 9.3 vs 1.0 mg/kg: 30.0 ± 9.5 and 3.0 mg/kg: 39.1 ± 11.4 mg/dl; 4/5 monkeys showed decreases at both doses). Flumazenil treatment did not significantly affect sucrose drinking measures at any of the doses tested (Table 3). The inverse agonist βCCE (0.03–0.18 mg/kg) significantly decreased the number of sipper extensions for ethanol at 0.18 mg/kg (F(3,12) = 7.92, p=0.004; 4/5 monkeys) but did not significantly affect other measures of alcohol drinking behavior (Table 3). βCCE increased latency to first sipper extension for sucrose (Fig 2, bottom; F(4,10) = 5.75, p<0.01) but did not affect other measures of sucrose drinking behavior at any of the doses tested. Two animals received 0.3 mg/kg (1 sucrose drinker, 1 ethanol drinker). The sucrose-drinking animal completed the course of treatment but testing at this dose was discontinued following the occurrence of a seizure in the ethanol-drinking animal on day 1 of testing. Therefore, doses higher than 0.18 mg/kg were not included in the analyses.

Observable behavior

α1-preferring compounds

Observation data are only presented for the novel α1GABAA-preferring compounds, in order to confirm that doses were behaviorally active. Significant effects are summarized in Table 4. Zolpidem significantly increased frequency scores for ataxia (F(6,23) = 13.25, p<0.001; Table 4) at 3.0 (4/5 monkeys) and 10.0 mg/kg (3/3 monkeys) in alcohol- but not sucrose-drinking animals. No other behavioral categories were significantly affected by zolpidem at the doses tested.

Table 4.

Summary of drug effects on selected observable behaviors. Direction of significant effects are indicated by ↓ (decrease), ↑ (increase) or = (no change). Doses are which these effects occur are indicated in parentheses and reported in mg/kg.

| Behavior | Ethanol | Sucrose | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zolpidem | 3-PBC | βCCT | Zolpidem | 3-PBC | βCCT | |

| Ataxia | ↑ (3.0, 10.0) | = | = | = | = | = |

| Tac/oral | = | = | ↓ | = | = | = |

| Self-directed | = | ↑ (10.0) | ↑ | = | = | = |

| Forage | = | ↓ (10.0) | = | = | ↓ | ↓ (0.3, 3.0) |

| Yawn | = | = | = | = | ↑ (10.0) | = |

| Visual explore | = | = | = | = | ↑ (5.6, 10.0) | = |

βCCT significantly decreased frequency scores for tac/oral behaviors (F(4,20) = 2.96, p<0.05; no significant post-hoc comparisons but 3/6 animals showed a decrease at 0.3 mg/kg, none at 1 mg/kg, 4/6 at 1.8 mg/kg, and 6/6 at 3.0 mg/kg; Table 4) while increasing scores for self-directed (aggregated self-groom and scratch) behaviors (F(4,19) = 4.68, p < 0.01; Table 4) at 3.0 mg/kg (5/6 monkeys) compared to vehicle in alcohol-drinking animals. In sucrose-drinking animals, βCCT significantly decreased foraging behavior (F(3,10) = 10.54, p<0.01) at 0.3 (4/4 monkeys) and 3.0 mg/kg (5/5 monkeys) but did not significantly affect tac/oral or self-directed behaviors. 3-PBC also significantly increased self-directed behaviors in alcohol-drinking animals only (F(5,24) = 7.48, p<0.001; Table 4) at 10.0 mg/kg (5/6 monkeys) compared to vehicle. In contrast, 3-PBC significantly decreased foraging behavior in both alcohol- and sucrose-drinking animals (F(5,24) = 3.38, p<0.05 and F(5, 13) = 3.12, p<0.05, respectively). However, post-hoc tests indicated a significant decrease compared to vehicle at 10.0 mg/kg (5/6 monkeys) in alcohol-drinking animals but no significant comparisons in sucrose-drinking animals (although 3/4 animals showed a decrease at doses 1.0–10.0 mg/kg; Table 4). 3-PBC also significantly increased yawning (F(5,13) = 3.96, p<0.05) at 10.0 mg/kg (3/4 animals) versus vehicle and passive visual behavior (F(5,13) = 3.16, p<0.05) at 5.6 and 10.0 mg/kg (4/4 animals for both doses) compared to vehicle in sucrose-drinking but not alcohol-drinking animals (Table 4). Neither βCCT nor 3-PBC significantly altered any other behavioral categories. Together, these behavioral changes indicate that the doses used were behaviorally active, and that sensitivity to their specific effects may differ slightly between alcohol- and sucrose-drinking animals.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, α1GABAA receptor-preferring compounds significantly increased time to complete the first FR10 in alcohol-drinking monkeys but had no other significant effects on alcohol- or sucrose-drinking behavior. These findings are in contrast to findings in rodents, in which α1GABAA-preferring antagonists are able to attenuate alcohol self-administration. In comparison, the nonselective agonist triazolam increased alcohol and sucrose consumption but had effects consistent with motor-sedative effects at higher doses. The nonselective antagonist flumazenil and inverse agonist βCCE did not affect alcohol or sucrose intake at the doses tested despite altering some measures of drinking behavior.

Alcohol interacts directly with the GABAA receptor at a binding site distinct from the benzodiazepine site (Mihic et al., 1997). Thus, the compounds used in the present study likely do not directly interfere with alcohol’s effects at the receptor, although the concentrations of alcohol reached during the drinking sessions (≥80 mg/dl) are pharmacologically relevant and would be considered legally intoxicating levels in humans. However, these compounds may be able to functionally antagonize the effects of alcohol by modulating its effects on GABAergic transmission, regardless of whether those effects are achieved via direct modulation through alcohol binding at the GABAA receptor, or through upstream modulation of GABAergic drive through alcohol binding to other receptors. Indeed, there is precedent for taking this approach to modulating alcohol’s effects (e.g., Helms et al., 2009; June et al., 1998). However, the present study was not designed to distinguish between sites of action of the drugs, but to assess whether these compounds may possess therapeutic potential in regards to their ability to reduce aspects of alcohol drinking behavior, including but not limited to intake, relative to their ability to induce non-alcohol related behavioral effects.

Both βCCT and 3-PBC significantly increased latency to first extension in alcohol-drinking animals, but failed to modify other aspects of drinking behavior such as intake, number of sipper extensions, and BAL. The finding that α1GABAA-preferring antagonists did not modulate the majority of drinking behavior measures is surprising, given the positive findings in previous studies (e.g. Harvey et al., 2002, June et al., 2003, but c.f. Werner et al., 2006). One study in nonhuman primates also reported reductions in alcohol drinking following 3-PBC administration, but at higher doses (18 mg/kg) than the doses used in the present study (Kaminski et al., 2012). We chose not to test higher doses due to the emergence of behavioral effects on the observation measures, which indicated the doses were behaviorally active and possibly anxiogenic (Major et al., 2009, Ruedi-Bettschen et al., 2013), but likely not sedative. This study also reported a significant reduction in number of alcohol drinks in the initial 20 minutes of each daily session, corroborating our observation of increased latency to sipper extension (3-PBC: 9 vs 86 sec; βCCT: 4 vs 187 sec). It is possible we saw no significant reduction in total intake due to the length of our self-administration sessions (3hrs), which may have allowed the animals to compensate for this initial decrease over the remainder of the session. Thus, the increase in latency suggests that these compounds may have potential to reduce relapse (i.e. delay initiation of drinking) and suggests that they should be examined in reinstatement paradigms to investigate this possibility.

Additionally, our study has several important differences from previous studies that may explain our contradictory results with α1GABAA-preferring antagonists. Aside from the study by Kaminski et al. (2012) in baboons, these studies were performed in rodents which had been specifically bred for high drinking behavior (HAD) or alcohol preference (P). Both of these rat strains demonstrate different responses than alcohol-nonpreferring rats to GABAergic compounds and alcohol in the open field and elevated plus maze tests (June et al., 1998). Thus, these animals may have alterations in the GABAergic system that could affect the actions of GABA subunit-specific compounds. Furthermore, our study used a repeated dosing paradigm, while the rodent studies generally used single-day dosing (Harvey et al., 2002), and in many cases, region-specific infusions into the brain (Harvey et al., 2002, June et al., 2003, Foster et al., 2004). As the α1GABAA receptor is widespread in the brain and we administered our test drugs systemically, it may be possible that effects of the antagonists in our study were offset by the actions of the drugs in other brain regions.

Neither 3-PBC nor βCCT increased latency in sucrose-drinking animals in the present study, suggesting the effects of these compounds may be specific to alcohol. This effect of 3-PBC is in contrast to previous studies which have reported that the effects may not be specific to alcohol. Baboons tended to drink less sucrose solution overall and drank significantly less during the initial 20 minutes of each session following 3-PBC treatment at doses similar to the dose highest dose (10mg/kg) used in our study (Kaminski et al., 2012). In addition, 3-PBC was able to reduce sucrose drinking in rats (Harvey et al., 2002), and mice lacking the α1GABAA receptor showed reduced sucrose self-administration in addition to reduced alcohol drinking behavior (Blednov et al., 2003). In contrast, βCCT administration is able to selectively attenuate alcohol drinking in rats (Foster et al., 2004, June et al., 2003) as well as aspects of alcohol drinking in our monkeys. The differences between these compounds observed in other studies may be due to the subtle difference in binding profile between the two compounds. 3-PBC has modest selectivity (approximately 10×) for the α1GABAA receptor over α2GABAA, α3GABAA, and α5GABAA receptors, and thus may act at these other receptors as well at higher doses (Harvey et al., 2002, Yin et al., 2010). βCCT has higher selectivity for the α1GABAA receptor over the other subunit-containing receptors (approximately 100×)(Harvey et al., 2002, Yin et al., 2010). Thus, the nonspecific effects of 3-PBC on sucrose drinking in previous studies at high doses may be due to action at α2/3/5GABAA receptors. However, the results reported in the present study agree with the reported selectivity data for both compounds (Yin et al., 2010, Cox et al., 1995). Importantly, we did not observe any signs of ataxia following 3-PBC or βCCT administration at the doses that increased latency in alcohol drinkers in the present study, suggesting that the observed effects are not due to nonspecific muscle-relaxant or motor-sedative effects (Tan et al., 2011, Licata et al., 2005, Rowlett et al., 2005).

Fewer studies have examined the effects of α1-preferring agonists on alcohol drinking. If α1GABAA receptor antagonists were able to decrease alcohol drinking, we would expect an α1GABAA agonist to facilitate or potentiate the effects of alcohol. However, zolpidem did not affect most measures of drinking behavior, including intake. This is, in fact, consistent with results of a study in humans that examined the subjective effects of zolpidem-alcohol combinations, which reported no change in measures of drug liking compared to the drug alone (Wilkinson, 1998). Zolpidem did produce an increase in latency to first sipper extension in the alcohol group at the higher doses tested (3.0 and 10.0 mg/kg), which also produced observable ataxia in our animals and are comparable to doses that reduced lever pressing and locomotor behavior in other studies in nonhuman primates (e.g. Rowlett et al., 2011, Rowlett et al., 2005). This effect thus may reflect zolpidem’s well-known sedative properties.

Unlike the α1GABAA-preferring compounds, triazolam, a nonselective benzodiazepine agonist, had complex effects on drinking measures. At lower doses, triazolam increased alcohol intake, possibly reflecting potentiation of the reinforcing effects of alcohol, without effects on BAL. At higher doses, triazolam did not decrease total intake or sipper extensions, but did decrease BAL at the end of the session. Together, this suggests a pattern of drinking behavior compressed into the first portion of the drinking session, possibly reflecting concurrent interactions between the reinforcing and sedative effects of triazolam and alcohol (e.g. triazolam enhances drinking behavior, but also enhances the sedative effects of alcohol; thus the animals drink more earlier in the session but then fail to maintain that level across the remainder of the 3hr session due to increased sedative effects.) In addition, alcohol is able to mildly inhibit metabolism of triazolam in liver microsomes (Tanaka et al., 2005), which may result in continued higher concentrations of active triazolam later in the session. The effects of triazolam were not completely specific to alcohol drinking, as approximately ten-fold higher doses of triazolam also increased sucrose consumption. Triazolam also increased latency to first sipper extension for both alcohol and sucrose, although there was almost a log-unit difference in the doses needed to engender this effect. Thus, it is possible that the delay to first extension occurred as a result of triazolam’s acute motor sedative effects, particularly since these doses have been shown to suppress lever responding in rhesus monkeys (Fischer and Rowlett, 2011). These differences in potency in alcohol- vs. sucrose-drinking monkeys could reflect common GABAergic mechanisms underlying the motor effects of the experimental compounds and alcohol, which do not occur with sucrose.

Neither the nonselective benzodiazepine antagonist, flumazenil, or inverse agonist, βCCE, decreased alcohol intake, although flumazenil decreased BALs. This is consistent with data showing that flumazenil is not able to reduce alcohol intake in 10min or 240min drinking sessions in rats (June et al., 1996, June et al., 1994), although no end-of-session BAL levels were presented in those studies for comparison. Although seemingly contradictory, the decrease in end-of-session BAL coupled with no change in total intake may reflect of shift of drinking behavior towards earlier in the session. Flumazenil has been shown to attenuate the discriminative stimulus effects of alcohol in cynomologous monkeys at similar doses to those tested in the present study, although this effect was surmountable with increased doses of ethanol (Helms et al., 2009). This finding supports the suggestion that flumazenil shifted drinking behavior towards the beginning of the session as a possible compensatory mechanism for reduced discriminative stimulus effects. Flumazenil also failed to significantly alter sucrose intake, in contrast to rodent studies showing a small but significant decrease in sucrose consumption (June et al., 1996). The nonselective benzodiazepine inverse agonist, βCCE, decreased the number of alcohol sipper extensions at the doses tested, but we were not able to complete the dose-response curve due to the occurrence of seizures in one monkey at the 0.3 mg/kg dose. Thus, nonselective neutral allosteric modulation (i.e., antagonism) of the GABAA receptor does not appear to significantly modify drinking behavior. Although nonselective negative modulation (i.e., inverse agonism) of the GABAA receptor was able to alter drinking behavior, these drugs are often hampered by the emergence of side effects. Notably, inverse agonist modulation at the α5GABAA receptor has been shown to selectively reduce alcohol drinking in the absence of severe side effects while a neutral α5GABAA-selective antagonism did not (Ruedi-Bettschen et al., 2013).

It is worth noting that alcohol-drinking animals appeared more sensitive to the effects of the nonselective agonist and inverse agonist. Higher doses of triazolam were needed to modify parameters of sucrose drinking behavior versus alcohol drinking behavior; in fact, doses that displayed sedative-like effects (e.g. increases in latency to first lever press, which occurs in the absence of any alcohol) in alcohol drinkers did not affect any behavioral parameters in sucrose drinkers. Similarly, the single sucrose-drinking monkey that received 0.3 mg/kg of βCCE tolerated the dose for the whole treatment course, whereas the ethanol-drinking animal presented a seizure on day 1. Chronic intermittent alcohol exposure in rodents induces a down-regulation of α1GABAA receptors and a shift towards α4GABAA-mediated neurotransmission (Cagetti et al., 2003, Olsen and Spigelman, 2012). However, we did not observe this difference in sensitivity between the two groups to the α1-preferring compounds. Benzodiazepine ligands do not bind to α4GABAA receptors, so increases in α4GABAA are unlikely to be responsible for the increased sensitivity in alcohol-drinking animals. Region-specific studies of mRNA in monkeys suggest that chronic alcohol self-administration in primates may alter less α1GABAA and α4GABAA, but instead down-regulate α2GABAA and α3GABAA (Hemby et al., 2006, Floyd et al., 2004). Thus, the differing sensitivity between the two groups is not explained by current understanding of the effects of chronic alcohol exposure on GABAA receptors, and suggests that the α2, α3, and α5 subunits may be affected.

Overall, our results do not support a strong contribution of the α1GABAA receptor to the reinforcing effects of alcohol. However, preferential antagonists were able to increase latency, suggesting that their effects may not be due to modification of alcohol’s direct reinforcing properties, but rather another psychological process such as motivation. Therefore, we propose that they may warrant investigation in abstinence maintenance and/or relapse paradigms. As a nonselective positive allosteric modulator was able to affect measures of drinking, these results suggest that GABAA receptor subtypes other than the α1GABAA subtype may be more promising targets for future medications to reduce alcohol drinking.

Acknowledgments

Supported by: AA16179, RR00168, OD11103

REFERENCES

- Blednov YA, Walker D, Alva H, Creech K, Findlay G, Harris RA. GABAA receptor alpha 1 and beta 2 subunit null mutant mice: behavioral responses to ethanol. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;305:854–863. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.049478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehm SL, 2nd, Ponomarev I, Jennings AW, Whiting PJ, Rosahl TW, Garrett EM, Blednov YA, Harris RA. gamma-Aminobutyric acid A receptor subunit mutant mice: new perspectives on alcohol actions. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68:1581–1602. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagetti E, Liang J, Spigelman I, Olsen RW. Withdrawal from Chronic Intermittent Ethanol Treatment Changes Subunit Composition, Reduces Synaptic Function, and Decreases Behavioral Responses to Positive Allosteric Modulators of GABAA Receptors. Molecular Pharmacology. 2003;63:53–64. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowen PJ, Green AR, Nutt DJ, Martin IL. ETHYL BETA-CARBOLINE CARBOXYLATE LOWERS SEIZURE THRESHOLD AND ANTAGONIZES FLURAZEPAM-INDUCED SEDATION IN RATS. Nature. 1981;290:54–55. doi: 10.1038/290054a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox ED, Hagen TJ, McKernan RM, Cook JM. Bz(1) receptor subtype specific ligands. Synthesis and biological properties of BCCt, a Bz(1) receptor subtype specific antagonist. Med. Chem. Res. 1995;5:710–718. [Google Scholar]

- Crestani F, Martin JR, Möhler H, Rudolph U. Mechanism of action of the hypnotic zolpidem in vivo. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2000;131:1251–1254. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Nurnberger J, Jr, Edenberg HJ, Goate A, Crowe R, Rice J, Bucholz KK, Kramer J, Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Porjesz B, Begleiter H, Hesselbrock V, Foroud T. Suggestive linkage on chromosome 1 for a quantitative alcohol-related phenotype. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2002;26:1453–1460. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000034037.10333.FD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer BD, Rowlett JK. Anticonflict and reinforcing effects of triazolam + pregnanolone combinations in rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;337:805–811. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.180422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd DW, Friedman DP, Daunais JB, Pierre PJ, Grant KA, McCool BA. Long-term ethanol self-administration by cynomolgus macaques alters the pharmacology and expression of GABAA receptors in basolateral amygdala. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;311:1071–1079. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.072025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster KL, McKay PF, Seyoum R, Milbourne D, Yin W, Sarma PV, Cook JM, June HL. GABA(A) and opioid receptors of the central nucleus of the amygdala selectively regulate ethanol-maintained behaviors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:269–284. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey SC, Foster KL, McKay PF, Carroll MR, Seyoum R, Woods JE, 2nd, Grey C, Jones CM, McCane S, Cummings R, Mason D, Ma C, Cook JM, June HL. The GABA(A) receptor alpha1 subtype in the ventral pallidum regulates alcohol-seeking behaviors. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2002;22:3765–3775. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-09-03765.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helms CM, Rogers LSM, Grant KA. Antagonism of the Ethanol-Like Discriminative Stimulus Effects of Ethanol, Pentobarbital, and Midazolam in Cynomolgus Monkeys Reveals Involvement of Specific GABAA Receptor Subtypes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2009;331:142–152. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.156810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemby SE, O'Connor JA, Acosta G, Floyd D, Anderson N, McCool BA, Friedman D, Grant KA. Ethanol-induced regulation of GABA-A subunit mRNAs in prefrontal fields of cynomolgus monkeys. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2006;30:1978–1985. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q, He X, Ma C, Liu R, Yu S, Dayer CA, Wenger GR, McKernan R, Cook JM. Pharmacophore/receptor models for GABA(A)/BzR subtypes (alpha1beta3gamma2, alpha5beta3gamma2, and alpha6beta3gamma2) via a comprehensive ligand-mapping approach. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2000;43:71–95. doi: 10.1021/jm990341r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunkeler W, Mohler H, Pieri L, Polc P, Bonetti EP, Cumin R, Schaffner R, Haefely W. Selective antagonists of benzodiazepines. Nature. 1981;290:514–516. doi: 10.1038/290514a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- June HL, Devaraju SL, Eggers MW, Williams JA, Cason CR, Greene TL, Leveige T, Braun MR, Torres L, Murphy JM. Benzodiazepine receptor antagonists modulate the actions of ethanol in alcohol-preferring and -nonpreferring rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998;342:139–151. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01489-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- June HL, Foster KL, McKay PF, Seyoum R, Woods JE, II, Harvey SC, Eiler WJA, II, Grey C, Carroll MR, McCane S, Jones CM, Yin W, Mason D, Cummings R, Garcia M, Ma C, Sarma PVVS, Cook JM, Skolnick P. The Reinforcing Properties of Alcohol are Mediated by GABAA1 Receptors in the Ventral Pallidum. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:2124–2137. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- June HL, Greene TL, Murphy JM, Hite ML, Williams JA, Cason CR, Mellon-Burke J, Cox R, Duemler SE, Torres L, Lumeng L, Li TK. Effects of the benzodiazepine inverse agonist RO19-4603 alone and in combination with the benzodiazepine receptor antagonists flumazenil, ZK 93426 and CGS 8216, on ethanol intake in alcohol-preferring (P) rats. Brain Res. 1996;734:19–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- June HL, Hughes RW, Spurlock HL, Lewis MJ. Ethanol self-administration in freely feeding and drinking rats: effects of Ro15-4513 alone, and in combination with Ro15-1788 (flumazenil) Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1994;115:332–339. doi: 10.1007/BF02245074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski B, Linn M, Cook J, Yin W, Weerts E. Effects of the benzodiazepine GABAA α1-preferring ligand, 3-propoxy-β-carboline hydrochloride (3-PBC), on alcohol seeking and self-administration in baboons. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2946-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Porcu P, Werner D, Matthews D, Diaz-Granados J, Helfand R, Morrow A. The role of GABA(A) receptors in the acute and chronic effects of ethanol: a decade of progress. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;205:529–564. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1562-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lelas S, Rowlett JK, Spealman RD, Cook JM, Ma C, Li X, Yin W. Role of GABAA/benzodiazepine receptors containing alpha 1 and alpha 5 subunits in the discriminative stimulus effects of triazolam in squirrel monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;161:180–188. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1037-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licata SC, Platt DM, Cook JM, Sarma PV, Griebel G, Rowlett JK. Contribution of GABAA receptor subtypes to the anxiolytic-like, motor, and discriminative stimulus effects of benzodiazepines: studies with the functionally selective ligand SL651498 [6-fluoro-9-methyl-2-phenyl-4-(pyrrolidin-1-yl-carbonyl)-2,9-dihydro-1H-py ridol[3,4-b]indol-1-one] J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;313:1118–1125. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.081612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major CA, Kelly BJ, Novak MA, Davenport MD, Stonemetz KM, Meyer JS. The anxiogenic drug FG7142 increases self-injurious behavior in male rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) Life sciences. 2009;85:753–758. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon LR, Gerak LR, France CP. Efficacy and the Discriminative Stimulus Effects of Negative GABAA Modulators, or Inverse Agonists, in Diazepam-Treated Rhesus Monkeys. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006;318:907–913. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.103168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihic SJ, Ye Q, Wick MJ, Koltchine VV, Krasowski MD, Finn SE, Mascia MP, Valenzuela CF, Hanson KK, Greenblatt EP, Harris RA, Harrison NL. Sites of alcohol and volatile anaesthetic action on GABAA and glycine receptors. Nature. 1997;389:385–389. doi: 10.1038/38738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen RW, Spigelman I. In: GABAA receptor plasticity in alcohol withdrawal, in Series GABAA receptor plasticity in alcohol withdrawal, Jasper's Basic Mechanisms of the Epilepsies. Noebels JL, Avoli M, Rogawski MA, et al., editors. Bethesda, MD: National Center for Biotechnology Information (US); 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirker S, Schwarzer C, Wieselthaler A, Sieghart W, Sperk G. GABA(A) receptors: immunocytochemical distribution of 13 subunits in the adult rat brain. Neuroscience. 2000;101:815–850. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00442-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt DM, Duggan A, Spealman RD, Cook JM, Li X, Yin W, Rowlett JK. Contribution of α1GABAA and α5GABAA Receptor Subtypes to the Discriminative Stimulus Effects of Ethanol in Squirrel Monkeys. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2005;313:658–667. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.080275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt DM, Rowlett JK, Spealman RD. Dissociation of cocaine-antagonist properties and motoric effects of the D1 receptor partial agonists SKF 83959 and SKF 77434. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;293:1017–1026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt DM, Rowlett JK, Spealman RD, Cook J, Ma C. Selective antagonism of the ataxic effects of zolpidem and triazolam by the GABAA/alpha1-preferring antagonist beta-CCt in squirrel monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;164:151–159. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1189-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowlett J, Kehne J, Sprenger K, Maynard G. Emergence of anti-conflict effects of zolpidem in rhesus monkeys following extended post-injection intervals. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;214:855–862. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2093-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowlett JK, Platt DM, Lelas S, Atack JR, Dawson GR. Different GABAA receptor subtypes mediate the anxiolytic, abuse-related, and motor effects of benzodiazepine-like drugs in primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:915–920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405621102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowlett JK, Spealman RD, Lelas S, Cook JM, Yin W. Discriminative stimulus effects of zolpidem in squirrel monkeys: role of GABA(A)/alpha1 receptors. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;165:209–215. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1275-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruedi-Bettschen D, Rowlett JK, Rallapalli S, Clayton T, Cook JM, Platt DM. Modulation of alpha5 subunit-containing GABAA receptors alters alcohol drinking by rhesus monkeys. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2013;37:624–634. doi: 10.1111/acer.12018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieghart W, Sperk G. Subunit composition, distribution and function of GABA(A) receptor subtypes. Curr Top Med Chem. 2002;2:795–816. doi: 10.2174/1568026023393507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J, Koller DL, Foroud T, Carr K, Zhao J, Rice J, Nurnberger JI, Jr, Begleiter H, Porjesz B, Smith TL, Schuckit MA, Edenberg HJ. Association of GABA(A) receptors and alcohol dependence and the effects of genetic imprinting. American journal of medical genetics. Part B. Neuropsychiatric genetics : the official publication of the International Society of Psychiatric Genetics. 2003;117B:39–45. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.10022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan KR, Rudolph U, Luscher C. Hooked on benzodiazepines: GABAA receptor subtypes and addiction. Trends Neurosci. 2011;34:188–197. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka E, Nakamura T, Terada M, Shinozuka T, Honda K. A study of the in vitro interaction between ethanol, and triazolam and its two metabolites using human liver microsomes. Journal of Clinical Forensic Medicine. 2005;12:245–248. doi: 10.1016/j.jcfm.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallender EJ, Ruedi-Bettschen D, Miller GM, Platt DM. A pharmacogenetic model of naltrexone-induced attenuation of alcohol consumption in rhesus monkeys. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2010;109:252–256. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner DF, Blednov YA, Ariwodola OJ, Silberman Y, Logan E, Berry RB, Borghese CM, Matthews DB, Weiner JL, Harrison NL, Harris RA, Homanics GE. Knockin Mice with Ethanol-Insensitive α1-Containing γ-Aminobutyric Acid Type A Receptors Display Selective Alterations in Behavioral Responses to Ethanol. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006;319:219–227. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.106161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson CJ. The Abuse Potential of Zolpidem Administered Alone and With Alcohol. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1998;60:193–202. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(97)00584-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin W, Majumder S, Clayton T, Petrou S, VanLinn ML, Namjoshi OA, Ma C, Cromer BA, Roth BL, Platt DM, Cook JM. Design, synthesis, and subtype selectivity of 3,6-disubstituted β-carbolines at Bz/GABA(A)ergic receptors. SAR and studies directed toward agents for treatment of alcohol abuse. Bioorg Med Chem. 2010;18:7548–7564. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.08.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler WH, Schalch E, Leishman B, Eckert M. Comparison of the effects of intravenously administered midazolam, triazolam and their hydroxy metabolites. British journal of clinical pharmacology. 1983;16(Suppl 1):63S–69S. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1983.tb02272.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]