Abstract

The quality of spousal relationships has been related to physical health outcomes. However, most studies have considered relationship positivity or negativity in isolation despite the fact that many close relationships are characterized by both positive and negative aspects (i.e., ambivalence). In addition, most work has ignored the reciprocal nature of close relationships processes that can impact on health. Using a sample of 136 older married couples, we thus tested actor-partner models of relationships quality that were either primarily positive or ambivalent (i.e., both helpful and upsetting aspects) on measure of coronary artery calcification (CAC). Results revealed an actor X partner interaction where CAC scores were highest for individuals who both viewed, and were viewed by their spouse as ambivalent. These data were discussed in light of the importance of considering both positive and negative aspects of relationship quality and modeling the interdependence of close relationships.

Keywords: Relationships, actor-partner models, ambivalence, social support, cardiovascular disease

The quality of one’s social relationships is reliably related to physical health outcomes (Berkman, Glass, Brissette, & Seeman, 2000; DeVogli, Chandola, & Marmot, 2007). In a recent meta-analysis of 148 studies comprised of over 308,000 participants, Holt-Lunstad, Smith, and Layton (2010) found evidence that social support was related to a 50% increased survival rate. Of our close relationships, the quality of one's marriage appears particularly important. It is one of the most significant adult relationships and has been similarly linked to positive health outcomes (Robles, Slatcher, Trombello, & McGinn, 2013).

One important issue regards the underlying aspects of spousal relationship quality that contribute to disease risk. Most of the studies on relationships and health focus on the positive and / or negative aspects of relationship quality by focusing on only one aspect or statistically controlling for the other (Uchino et al., 2012). For instance, negativity in relationships has been linked to poorer physical health even when controlling for social support (DeVogli et al., 2007). However, relationships that are relied upon to be major sources of support are not uniformly positive and can add to a person’s distress during their time of need (e.g., feeling frustrated or let down by the support provider; Newsom, Nishishiba, Morgan, & Rook, 2003). It has thus been argued that positivity and negativity are not opposites on the same scale so relationships can be sources of both positivity and negativity, or what we have called "ambivalent” network ties (Uchino, Holt-Lunstad, Uno, & Flinders, 2001). Such ambivalent ties are a common feature of most individuals' social networks (Campo et al., 2009) and appear to have a basis in specific behavioral interactions stemming from criticism, less provided support, unsolicited advice, personality differences, child rearing disagreements, and past relationship problems (Birditt, Miller, Fingerman, & Lefkowitz, 2009; Pillemer & Suitor, 2002; Reblin, Uchino, & Smith, 2010).

Importantly, viewing a network member as a source of ambivalence has been linked to a number of health-related outcomes including increased cardiovascular reactivity, ambulatory blood pressure, inflammation, and cellular aging (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2003; Uchino et al., 2012; Uchino et al., 2013). However, this work has only focused on the prediction of health outcomes based on a participant’s own perception of their relationship quality and hence ignored the reciprocal nature of close relationships (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978; Rusbult & van Lange, 2008). Thus, it is important to also consider if a partner’s attributes or attributes of the dyad as a whole influence important outcomes (i.e., partner influences, actor X partner influences, Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). Such dyadic modeling is starting to elucidate how close relationships influence each other for better or worse (Butler, 2011). For instance, marriage is an important context characterized by mutual support-seeking, support provision, and social negativity that can have cascading influences on health-relevant outcomes (Pietromonaco, Uchino, & Dunkel-Schetter, 2013).

In the present study, we thus tested actor-partner models examining spouses that were viewed as either primarily helpful or both helpful and upsetting (i.e., ambivalent). These actor-partner relationship perceptions were used to predict measures of coronary artery calcification (CAC) which are correlated with the extent of plaque build-up in the coronary arteries and thus a robust predictor of cardiovascular risk (Pletcher, Tice, Pignone, & Browner, 2004). Given the health outcomes previously associated with ambivalent ties, we predicted that CAC scores would be highest when both members of a dyad viewed each other as ambivalent. We further predicted that this association would be independent of traditional risk factors such as age and smoking.

Methods

Participants

The Utah Health and Aging Study (Smith et al., 2007), approved by the University of Utah IRB, enrolled middle-age and older married couples from the Salt Lake City area with no history of cardiovascular disease. We report the results of 136 older couples with complete relationship data because detectable CAC was uncommon in the middle-aged couples. In the older couples, the average age was 63 years (sd=4.62) and the mean length of marriage was 36 years (sd=10.30). Median household income was $50,000 – 75,000 per year, and 96.7% were non-Hispanic white.

Procedures

As part of the larger project (Smith et al., 2007), couples independently completed the social relationships index to examine marital ambivalence. They also completed a questionnaire assessing basic demographics as well as a marital satisfaction scale. Participants then underwent medical clinic visits for biomedical and health behavior risk factors that included a blood draw and CAC measurement approximately one week later.

Measures

Social Relationships Index (SRI)

Individuals rated how helpful and upsetting (1 = not at all, 2=a little, 3=somewhat, 4=moderately, 5=very, 6 = extremely) they perceived their spouse when they needed support such as advice, understanding, or a favor. These helpful and upsetting items load on distinct factors and are characterized by good test-retest reliability (see Campo et al., 2009). Based on our model, we operationalized spouses’ relationships as purely positive or ambivalent (see Campo et al., 2009; Uchino et al., 2012; Uchino et al., 2013). Thus, a spouse viewed as a source of positivity only was rated as a "2" or greater on helpful and only a “1” on upset during support, whereas a spouse viewed as a source of ambivalence was rated a "2" or greater on both helpful and upset during support. In the present study, the mean level of spouse helpfulness was 5.31 (sd=0.97), whereas the mean level of spouse upset was 2.11 (sd=1.07). The correlation between the spouse helpfulness and upset scales was −.35. Based on our categorization procedure 30% of the individuals were viewed by their spouse as primarily a source of positivity, whereas 70% were viewed by their spouse as ambivalent.

An alternative analytic approach would be to model the actor-partner helpful X upset interactions using continuous ratings. There are several reasons why we have chosen our particular operationalization of ambivalent ties (Uchino et al., 2001; Uchino et al., 2012). First, there are typically no longer-term spouses rated as aversive (only negative). Thus, the testing of such an interaction would force individuals into aspects of our model that are not present in the study. Of course, with other relationships this might be appropriate (e.g., co-workers) in which one might expect the full range of relationships. Second, we have utilized this categorical approach in the past because the same operationalization can be used to examine specific relationships (e.g., perceptions of ambivalence in marriage) or across the network as a whole (e.g., total number of ambivalent network ties). Thus, our procedure is based directly on our model, has been used consistently across our program of research, and can be used to guide potential clinical screening procedures given the specificity of our approach. However, this raises the possibility that our classification might mean that spouses viewed as sources of ambivalence differ primarily from spouses viewed as sources of positivity in one of these ratings; thus we report analyses below aimed at addressing this issue by also statistically controlling for ratings of perceived relationship helpfulness and upset to test if there is something unique about the co-occurrence of these relationship dimensions.

Marital Adjustment Test (MAT)

The MAT contains 15 items and is a widely used measure of overall marital quality (Locke & Wallace, 1959; Beach, Fincham, Amir, & Leonard, 2005). Its psychometric properties are well documented and reliably distinguishes distressed from non-distressed couples (Beach et al., 2005).

Risk factors and coronary artery calcification

Glucose and plasma lipids were measured via fasting blood draws. Behavioral risk factors (i.e., smoking, alcohol use, activity level) were assessed via self-report. Participants underwent coronary artery scans on a multidetector scanner (Phillips MX8000, Philips Medical Systems, Cleveland, OH), using 2.5-mm collimation transverse slices obtained from 2-cm inferior to the carina to the inferior margin of the heart. On each gantry rotation four 2.5-mm slices were obtained. Scans were obtained in a single breath-hold using 500 msec exposure and axial (non-spiral) mode imaging. Using ECG-triggering, image acquisition was initiated during diastole corresponding to 50% of the R-R interval. Image reconstruction was performed using a 220-mm field of view and a 512 × 512 matrix with a standard reconstruction filter, giving a nominal pixel area of 0.18-mm2 and voxel volume of 0.46-mm3. To equate CAC scores to electron-beam scanners using the method of Agatston (Agaston et al., 1990), multidetector imaging scores were multiplied by 0.833 (2.5mm/3.0mm) to compensate for thinner collimation. CAC scores were transformed as nlog (CAC + 1; Reilly, Wolfe, Localio, & Rader, 2004).

Statistical Analyses

We utilized proc mixed (SAS institute) in order to examine these actor-partner models (Campbell & Kashy, 2002). All factors were treated as fixed (Nezlek, 2008) and proc mixed treats the unexplained variation within individuals as a random factor. We modeled the covariance structure for the repeated measures factors of dyad (i.e., husband, wife) using the compound symmetry structure (Campbell & Kashy, 2002). The outputs of these models were parameter estimates (b) using the Satterthwaite approximation to determine the appropriate degrees of freedom (Campbell & Kashy, 2002). The intraclass correlation for partners’ CAC scores was .15.

Results

Actor / Partner Influences on CAC

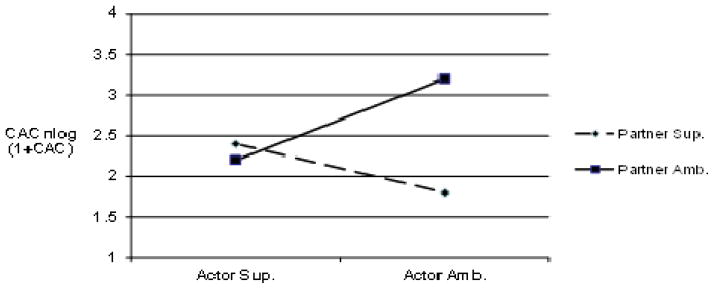

Our main analyses focused on actor-partner models linking views of spousal relationship ambivalence to CAC. In these models, we statistically controlled for age, gender, and body mass. Results revealed that actor and partner views of spousal ambivalence did not predict CAC scores (see Table 1, p’s>.10). However, consistent with the importance of modeling dyadic influences the actor X partner interaction was significant in predicting CAC (b=.40, SE=.15, p=.01). As shown in Figure 1, CAC scores were highest when both partners in the relationship viewed each other as ambivalent. Simple slope analyses showed that CAC scores in the actor ambivalence / partner ambivalence group was significantly greater than the actor ambivalence / partner support group (p=.001) as well as marginally different from the actor support / partner ambivalence group (p=.07). No other simple slope analyses approached significance. These links were not moderated by gender suggesting they were comparable for husbands and wives.

Table 1.

Main actor-partner analyses on CAC.*

| Variable | b | SE | t | p-level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | .11 | .03 | 3.88 | .0001 |

| Gender | .97 | .13 | 7.56 | .0001 |

| Body Mass | .02 | .01 | 1.67 | .10 |

| Actor Sup.-Amb. | .05 | .14 | .38 | .71 |

| Partner Sup.-Amb. | .24 | .14 | 1.64 | .10 |

| Actor X Partner | .40 | .15 | 2.58 | .01 |

Actor-partner main effects based on analyses without the cross-product term (Sup.=supportive, Amb.=ambivalent).

Figure 1.

Predicted CAC scores for actor and partner relationship quality (i.e., positive or ambivalent).

Ancillary Analyses and Alternative Explanations

We next evaluated several potential alternative explanations for our main results (see Supplementary Tables 1–3). Analyses were first conducted to examine if basic biomedical factors (e.g., cholesterol levels) and health behaviors were responsible for these links. Entering the variables that were related to CAC (p<.10; i.e., smoking status, triglycerides, and very low density lipoproteins) did not alter the actor X partner links to CAC (p=.03). We also evaluated whether our results were independent of continuous measures of actor-partner relationship helpful and upset ratings. Importantly, our results were unchanged (p=.01) suggesting there is something unique about the combination of helpful and upset ratings in predicting CAC. Finally, we evaluated the possibility that our results were driven by traditional assessments of marital satisfaction. Although actor and partner main effects of relationship ambivalence were found on marital satisfaction (Supplementary Table 4), the actor X partner interaction was not significant nor was our main result changed when statistically controlling for marital satisfaction (Supplementary Table 3). These data suggest that perceived spousal ambivalence is not simply a surrogate measure of overall marital satisfaction.

Discussion

The main aim of the study was to test if the perception of ambivalence towards a spouse was related to CAC using actor-partner analyses that model the interdependent nature of close relationships (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978; Rusbult & van Lange, 2008). Even when statistically controlling for traditional behavioral risk factors, CAC scores were highest if both individuals within a marriage viewed each other as relatively high in both helpfulness and upset during support. These results also did not reflect spousal helpfulness or upset ratings in isolation or traditional assessments of martial satisfaction. These data highlight the importance of considering positivity and negativity in relationships in the context of dyadic level processes.

One main contribution of this study is that most research on relationships and health focuses on the positive or negative aspects of relationships (Uchino et al., 2012). This work ignores the possibility that one can experience simultaneous feelings of positivity and negativity towards a specific relationship (i.e., ambivalence). These feelings of ambivalence are quite common in close relationships and may reflect past relationship difficulties, personality differences, and / or negative support exchanges (Birditt et al., 2009; Pillemer & Suitor, 2002; Reblin et al., 2010). Importantly, perceptions of ambivalence toward close relationships have been linked to a number of adverse outcomes relevant to physical health including ABP during daily life, inflammation, and cellular aging (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2007; Uchino et al., 2012; Uchino et al., 2013). We extend prior work by linking perceptions of ambivalence towards a spouse to noninvasive measures of the underlying extent of coronary artery disease as indexed by CAC (Plecther et al., 2004).

A second contribution of this study is that the inherent interdependence in close relationships was directly modeled using actor-partner models (Kenny et al., 2006). All of the prior work has focused on if a person’s perceptions of relationship ambivalence influences their own outcomes (i.e., actor influences). However, there is good reason to model actor-partner interactions especially in the context of cardiovascular disease using measures of CAC. Coronary atherosclerosis is a long-term process that takes decades to become clinically significant (Ferrari, Radaelli, & Centola, 2003). Long-term marriages thus provide an ideal context for examining such slowly unfolding disease processes and modeling the marital context as a dyad may produce more consistent links to long-term disease risk.

An important issue concerns the potential mechanisms responsible for these associations. We did not find that standard biomedical factors, separate helpful / upset ratings, or overall marital satisfaction were responsible for the actor X partner interaction on CAC. Our prior work with this sample has examined links between personality factors as well as marital behavior during a laboratory conflict / collaboration protocol and CAC (e.g., Smith et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2011). However, ancillary analyses statistically controlling for those variables examined in our prior published work did not alter the present findings. Hence, we believe that these results may reflect mutual support-related mechanisms. That is, perceptions of ambivalence towards a relationship are linked to less support-seeking (Holt-Lunstad, Uchino, Smith, & Hicks, 2007). Even when support is sought, ambivalent ties provide poorer quality social support (e.g., less emotional support, more criticizing) when individuals are under stress as rated by independent observers (Reblin et al., 2010). Thus, couples who perceive their spouse in ambivalent terms are less likely to seek support from each other and / or benefit from mutual support in an important relationship context (i.e., marriage). It is also possible that there is a more direct influence of ambivalent ties on health as the mere presence of such relationships is associated with greater cardiovascular activity (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2007). Thus, simply being in the same room as the spouse viewed as ambivalent may heighten physiological arousal which may be detrimental in the long-term.

There are several important limitations of this work. First, the cross-sectional design precludes causal conclusions. However, due to the exclusion of participants with cardiovascular disease, it seems unlikely that the observed associations reflect changes in couple’s relationship quality in reaction to cardiovascular conditions. Second, the sample is largely Caucasian and middle or upper-middle class, and heterosexual married couples. Generalization to other groups requires further research. Finally, this is one of the first studies examining actor-partner differences in relationship ambivalence so future work modeling such differences across different aspects of cardiovascular risk will be needed.

Supplementary Material

References

- Agatston AS, Janowitz WR, Hildner FJ, Zusmer NR, Viamonte M, Detrano R. Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1990;15:827–832. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)90282-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach SRH, Fincham FD, Amir N, Leonard KE. The taxometrics of marriage: Is marital discord categorical? Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:276–285. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, Seeman TE. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Social Science and Medicine. 2000;51:843–857. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birditt KS, Miller LM, Fingerman KL, Lefkowitz ES. Tensions in the parents and adult child relationship: Links to solidarity and ambivalence. Psychology and Aging. 2009;24:287–295. doi: 10.1037/a0015196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler EA. Temporal interpersonal emotion systems: The “TIES” that form relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2011;15:367–393. doi: 10.1177/1088868311411164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell L, Kashy DA. Estimating actor, partner, and interaction effects for dyadic data using PROC MIXED and HLM: A user-friendly guide. Personal Relationships. 2002;9:327–342. doi: 10.1111/1475-6811.00023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campo RA, Uchino BN, Holt-Lunstad J, Vaughn AA, Reblin M, Smith TW. The Assessment of Positivity and Negativity in Social Networks: The Reliability and Validity of the Social Relationships Index. Journal of Community Psychology. 2009;37:471–486. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Vogli R, Chandola T, Marmot MG. Negative aspects of close relationships and heart disease. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167:1951–1957. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.18.1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari AU, Radaelli A, Centola M. Aging and the cardiovascular system. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2003;95:2591–2597. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00601.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton B. Social Relationships and Mortality: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS Medicine. 2010;7:1–20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J, Uchino BN, Smith TW, Cerny CB, Nealey-Moore JB. Social Relationships and Ambulatory Blood Pressure: Structural and Qualitative Predictors of Cardiovascular Function During Everyday Social Interactions. Health Psychology. 2003;22:388–397. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.4.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad JL, Uchino BN, Smith TW, Hicks A. On the Importance of Relationship Quality: The Impact of Ambivalence in Friendships on Cardiovascular Functioning. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;33:278–290. doi: 10.1007/BF02879910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley HH, Thibaut JW. Interpersonal relations: A theory of interdependence. New York: Wiley-Interscience; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Analysis of dyadic data. New York: Guilford; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Locke HJ, Wallace KM. Short marital-adjustment and prediction tests: Their reliability and validity. Marriage and Family Living. 1959 Aug;21:251–255. doi: 10.2307/348022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newsom JT, Nishishiba M, Morgan DL, Rook KS. The relative importance of three domains of positive and negative social exchanges: A longitudinal model with comparable measures. Psychology and Aging. 2003;18:746–754. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.4.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nezlek JB. An introduction to multilevel modeling for social and personality psychology. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2008;2:842–860. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00059.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pietromonaco PR, Uchino BN, Dunkel-Schetter C. Close relationship processes and health: Implications of attachment theory for health and disease. Health Psychology. 2013;32:499–513. doi: 10.1037/a0029349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillemer K, Suitor JJ. Explaining mothers' ambivalence towards their adult children. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2002;64:602–613. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00602.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pletcher MJ, Tice JA, Pignone M, Browner WS. Using the coronary artery calcium score to predict coronary heart disease events: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2004;64:1285–92. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.12.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reblin M, Uchino BN, Smith TW. Provider and Recipient Factors that May Moderate the Effectiveness of Received Support: Examining the Effects of Relationship Quality and Expectations for Support on Behavioral and Cardiovascular Reactions. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2010;33:423–431. doi: 10.1007/s10865-010-9270-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly MP, Wolfe ML, Localio AR, Rader DJ. Coronary artery calcification and cardiovascular risk factors: impact of the analytic approach. Atherosclerosis. 2004;173:69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robles TF, Slatcher RB, Trombello JM, McGinn MM. Marital Quality and Health: A Meta-Analytic Review. Psychological Bulletin. 2013 Mar 25; doi: 10.1037/a0031859. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult CE, Van Lange PAM. Why we need interdependence theory. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2008;2/5:2049–2070. [Google Scholar]

- Smith TW, Uchino BN, Berg CA, Florsheim P, Pearce G, Hawkins M, Hopkins PN, Yoon HC. Hostile Personality Traits and Coronary Artery Calcification in Middle-Aged and Older Married Couples: Different Effects for Self-Reports versus Spouse Ratings. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2007;69:441–448. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3180600a65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TW, Uchino BN, Florsheim P, Berg CA, Butner J, Hawkins M, Henry NJM, Beveridge RM, Pearce G, Hopkins PN, Yoon H. Affiliation and control during marital disagreement, history of divorce and asymptomatic coronary artery calcification in older couples. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2011;73:350–357. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31821188ca. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN, Cawthon RM, Smith TW, Light KC, McKenzie J, Carlisle M, Gunn H, Birmingham W, Bowen K. Social Relationships and Health: Is Feeling Positive, Negative, or Both (Ambivalent) about your Social Ties Related to Telomeres? Health Psychology. 2012;31:789–796. doi: 10.1037/a0026836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN, Bosch JA, Smith TW, Carlisle M, Birmingham W, Bowen KS, Light KC, Heaney J, O’Hartaigh Briain. Relationships and cardiovascular risk: Perceived spousal ambivalence in specific relationship contexts and its links to inflammation. Health Psychology. doi: 10.1037/a0033515. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN, Holt-Lunstad J, Uno D, Flinders JB. Heterogeneity in the Social Networks of Young and Older Adults: Prediction of Mental Health and Cardiovascular Reactivity during Acute Stress. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2001;24:361–382. doi: 10.1023/A:1010634902498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.