Abstract

Objectives

To determine the 99th percentile upper reference limit for the highly sensitive cardiac troponin T assay (hs-cTnT) in three large independent cohorts.

Background

The presently recommended 14 ng/L cutpoint for the diagnosis of myocardial infarction using the hs-cTnT assay was derived from small studies of presumably healthy individuals, with relatively little phenotypic characterization.

Methods

Data were included from three well characterized population-based studies: the Dallas Heart Study (DHS), the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study, and the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS). Within each cohort, reference subcohorts were defined excluding individuals with recent hospitalization, overt cardiovascular disease and kidney disease (subcohort 1) and further excluding those with subclinical structural heart disease (subcohort 2). Data were analyzed stratified by age, sex and race.

Results

The 99th percentile values for the hs-cTnT assay in DHS, ARIC and CHS were 18, 22 and 36 ng/L respectively (subcohort 1) and 14, 21 and 28 ng/L respectively (subcohort 2). These differences in 99th percentile values paralleled age differences across cohorts. Analyses within sex/age strata yielded similar results between cohorts. Within each cohort, 99th percentile values increased with age and were higher in men. More than 10% of men aged 65–74 with no cardiovascular disease in our study had cTnT values above the current myocardial infarction threshold.

Conclusions

Use of a uniform 14 ng/L cutoff for the hs-cTnT assay may lead to over-diagnosis of myocardial infarction, particularly in men and the elderly. Clinical validation is needed of new age- and sex-specific cutoff values for this assay.

Keywords: myocardial infarction, diagnosis, population, troponin

Introduction

The recently developed high sensitivity assay for cardiac troponin T (hs-cTnT) has been implemented in many countries for the diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction (MI), and will likely be introduced in the United States in the near future (1–5). By convention, the upper reference limit for high sensitivity troponin assays is defined as the 99th percentile value from a normal reference population (6,7). However, no clear consensus exists regarding the composition of a “normal population” in this context (3,5,8). Given the central role of troponin measurement in MI diagnosis, accurate determination of the upper reference limit is critically important for the use and interpretation of troponin assays.

The presently accepted 99th percentile upper reference limit for the hs-cTnT assay (14 ng/L) was initially derived from a study of 616 “apparently healthy” volunteers and blood donors, with little information reported regarding subject selection (6), and then confirmed by a study of 533 individuals selected based primarily on a standardized questionnaire (9). Other studies in smaller cohorts, with varying degrees of phonotypical characterization, reported 99th percentiles ranging from 14.4 ng/L to 16.9 ng/L (8,10-12).

Clinical use of the present cutoff for the hs-cTnT assay does not take into account patient sex, age and race. However, sex differences in the 99th percentile values for both hs-cTnT and hs-cTnI assays have been reported in a number of small studies (8–15), with a trend for higher values in men, leading to a statement in the most recent Universal Definition of MI that sex-dependent upper reference limits for hs-cTn assays may be recommended in the future (7). A numeric trend towards higher 99th percentiles for the hs-cTn assay in older individuals was also reported in some, but not all studies, based on very few subjects in older age strata (9,11,13,14). Finally, whether the 99th percentiles for hs-cTn assays are influenced by race is unclear. Presently available data are insufficient to derive sex-, age-, or race-specific upper reference limits.

To address this critical knowledge gap, we analyzed cTnT values measured with the hs-cTnT assay in three large independent community-based cohorts: the Dallas Heart Study (DHS) (16), the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study (17), and the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) (18). We determinined 99th percentile values for the hs-cTnT assay in clearly defined subcohorts of DHS, ARIC and CHS, with sequential exclusion of “non-healthy” participants and those with subclinical cardiovascular disease, and with additional stratification by age, sex and race. Compared with previous studies of the hs-cTnT assay upper reference limit, the present study of 12,618 adults benefits from a much larger size, unambiguous selection process, detailed phenotypic characterization, and broader representation of different age ranges.

Methods

Study design and populations

Cross-sectional analyses were performed in three independent community-based cohorts: the Dallas Heart Study (DHS), the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study, and the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS). The DHS is a probability-based sample of 6101 adults enrolled between 2000–2002 from Dallas County, Texas, with intentional oversampling of black individuals to constitute approximately 50% of the cohort (19). cTnT was measured in 3546 DHS participants between 30–65 years of age. The cohort component of the ARIC study comprises a total of 15,792 individuals 45 to 64 years old, randomly selected from Forsyth County, North Carolina; suburban Minneapolis, Minnesota; Jackson, Mississippi; and Washington County, Maryland (approximately one quarter of the cohort from each region) (20). For ARIC, cTnT was measured during visit 4 of the study (1996–1998), in 11,271 eligible individuals (17). The CHS is a sample of 5,888 community-dwelling adults 65 years or older recruited from four communities: Forsyth County, North Carolina; Hagerstown, Maryland; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; and Sacramento, California (21). Of the CHS cohort, 5,201 individuals were enrolled in 1989–1990 (main cohort), and 687 additional black subjects were enrolled in 1992–1993 (supplemental cohort). cTnT was measured in 4,221 participants from CHS. Detailed descriptions of the design, objectives and examinations performed for each of the three cohort studies have been previously published (19–21). The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki, all participants in DHS, ARIC and CHS provided written informed consent, and approval for the study was obtained from the institutional review boards at all participating institutions.

Definition of subcohorts /exclusion criteria

Because the 99th percentile upper reference limit for cTnT is by convention established in a normal reference population (6,7), we restricted our analyses to two prospectively defined subcohorts selected from each of the three studies. Subcohort 1 was defined as individuals free from recent hospitalization of any cause (6 months prior to blood collection for the study), with no clinical cardiovascular disease (coronary heart disease, chronic heart failure, atrial fibrillation, prior stroke) or stage III or greater chronic kidney disease (estimated GFR < 60 mL/min/1.73m2). Subcohort 2 further excluded from subcohort 1 those individuals with subclinical structural heart disease, defined as left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy (LVH) by ECG (ARIC and CHS) or MRI (DHS), LV ejection fraction (LVEF) < 55% by echocardiogram (CHS, ARIC) or MRI (DHS), or N-terminal Pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) > 450 ng/L. Subjects with missing or exhausted biorepository samples were also excluded from both subcohorts, and subjects with missing imaging or ECG data were excluded from subcohort 2.

Laboratory measurements

cTnT was measured in sample aliquots previously stored at −70°C using a highly sensitive automated immunoassay (Troponin T hs STAT, Elecsys-2010, Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, Indiana), with a limit of detection of 5 ng/L and a limit of blank of 3 ng/L. The lowest cTnT concentration that can be measured with a coefficient of variation ≤ 10% with this assay is 13 ng/L (22). The assay lot numbers used were 153401 for DHS, 153401 and 154102 for ARIC, and 153401 for CHS. None of these lots were affected by problems reported by the manufacturer with other lot numbers (23,24). NT-proBNP levels were measured as described (25). Glomerular filtration rate was estimated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) formula (26).

Statistical analyses

The 99th percentile values and corresponding 95% confidence intervals were calculated for subcohorts 1 and 2 of DHS, ARIC and CHS, with further stratification by sex, age and race. Distribution-free confidence intervals were used because of the skewed distribution of cTnT. Specifically, rank order statistics were used for the bounds on the confidence limit such that the difference in the cumulative binomial probabilities satisfied the coverage probability requirement of 0.95. The 95% confidence interval for a given 99th percentile indicates that the 99th cTnT percentile of a general population sample with similar baseline characteristics as the respective subcohort or sex/age/race stratum has a 95% probability of falling within the calculated confidence interval. Within the DHS cohort only, sensitivity analyses were performed to determine the impact of assumptions made in determining the composition of subcohort 2. In these sensitivity analyses, the impact of various inclusion/exclusion criteria (including imaging, ECG and NT-proBNP criteria) on the 99th percentile cTnT value was assessed.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

Baseline demographic, clinical and laboratory characteristics of the study subcohorts are presented in Table 1. A total of 12,618 adults were analyzed across the three studies. The median age was lowest in DHS and highest in CHS.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study subcohorts.

| DHS | ARIC | CHS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subcohort 1* (N=2955) |

Subcohort 2† (N=1978) |

Subcohort 1 (N=7788) |

Subcohort 2 (N=7575) |

Subcohort 1 (N=1875) |

Subcohort 2 (N=1374) |

|

| Median age (interquartile range) | 43.3 (9.8) | 43.2 (9.6) | 61 ( 9) | 61 (9) | 73 (6) | 72 (6) |

| Female, % | 54.5 | 55.9 | 61.2 | 60.8 | 62.9 | 64.4 |

| Race / ethnicity, % | ||||||

| Black | 49.4 | 41.5 | 21.1 | 20.9 | 18.2 | 20.6 |

| White | 30.5 | 36.1 | 78.9 | 79.1 | 81.5 | 79.8 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 17.9 | 20.1 | N/A‡ | N/A | N/A‡ | N/A |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1.9 | 2.1 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Native American | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Other | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Smoking, % | 27.8 | 24.7 | 12.8 | 12.8 | 10.5 | 10.1 |

| Hypertension, % | 29.8 | 24.4 | 41.6 | 40.8 | 53.4 | 52.3 |

| Diabetes mellitus, % | 9.9 | 8.3 | 9.9 | 9.8 | 12.4 | 11.6 |

| GFR < 90 mL/min/1.73m2 | 33.2 | 35.6 | 20.9 | 20.7 | 90.3 | 89.2 |

| LVH or LVEF < 55% | 10.3 | 0 | 2.42 | 0 | 7.7 | 0 |

| NT-proBNP > 450 ng/L | 0.8 | 0 | 1.1 | 0 | 5.4 | 0 |

| Detectable cTnT, % (hs-cTnT assay) | 23.9 | 21.1 | 37.9 | 38.2 | 56.1 | 52.3 |

Subcohort 1: Subjects free from recent hospitalization (6 months), clinical CVD (CHD, CHF, atrial fibrillation, prior stroke), and stage III or greater CKD (eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73m2).

Subcohort 2: Subjects free from recent hospitalization (6 months), clinical CVD (CHD, CHF, atrial fibrillation, prior stroke), subclinical CVD (LVH or LVEF < 55% by echo or MRI, LVH by ECG, NT-proBNP > 450 ng/L), and stage III or greater CKD (eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73m2).

In ARIC and CHS race and ethnicity were recorded separately, and thus Hispanic/Latino subjects self-reported their race separately from their Hispanic/Latino ethnicity.

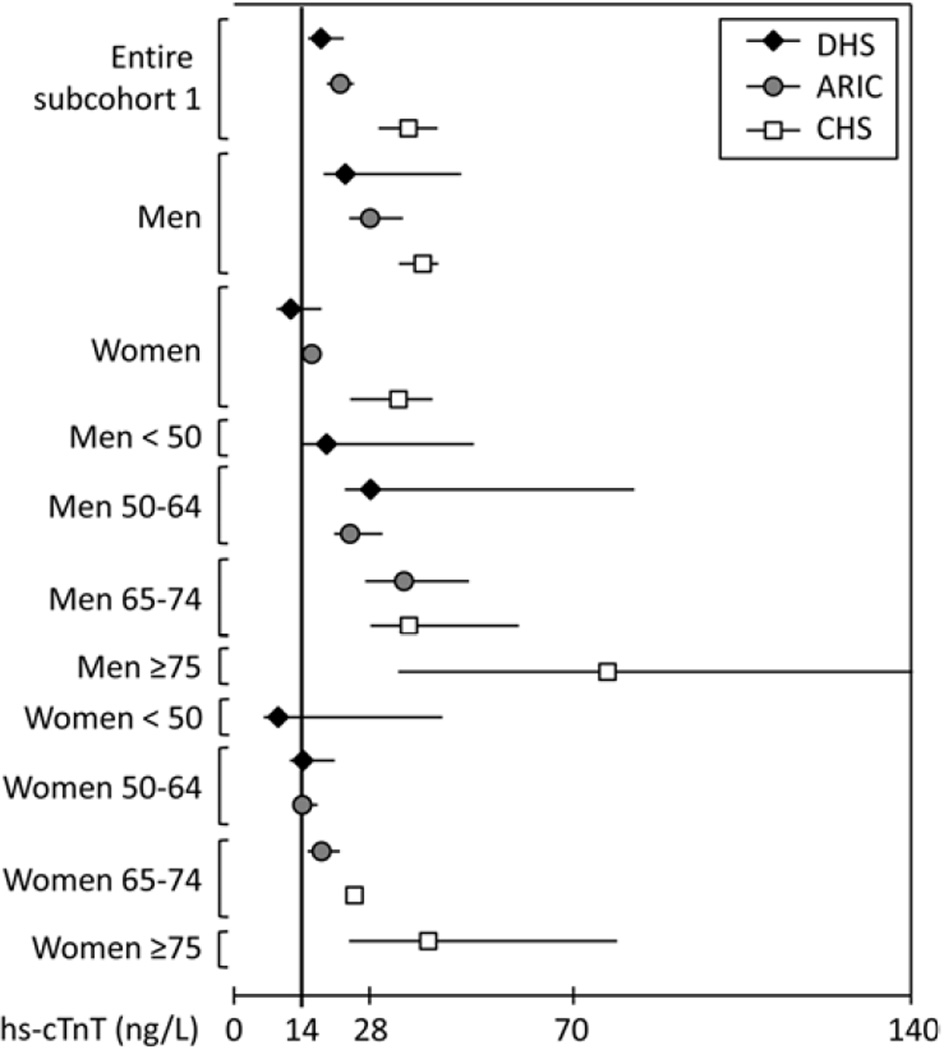

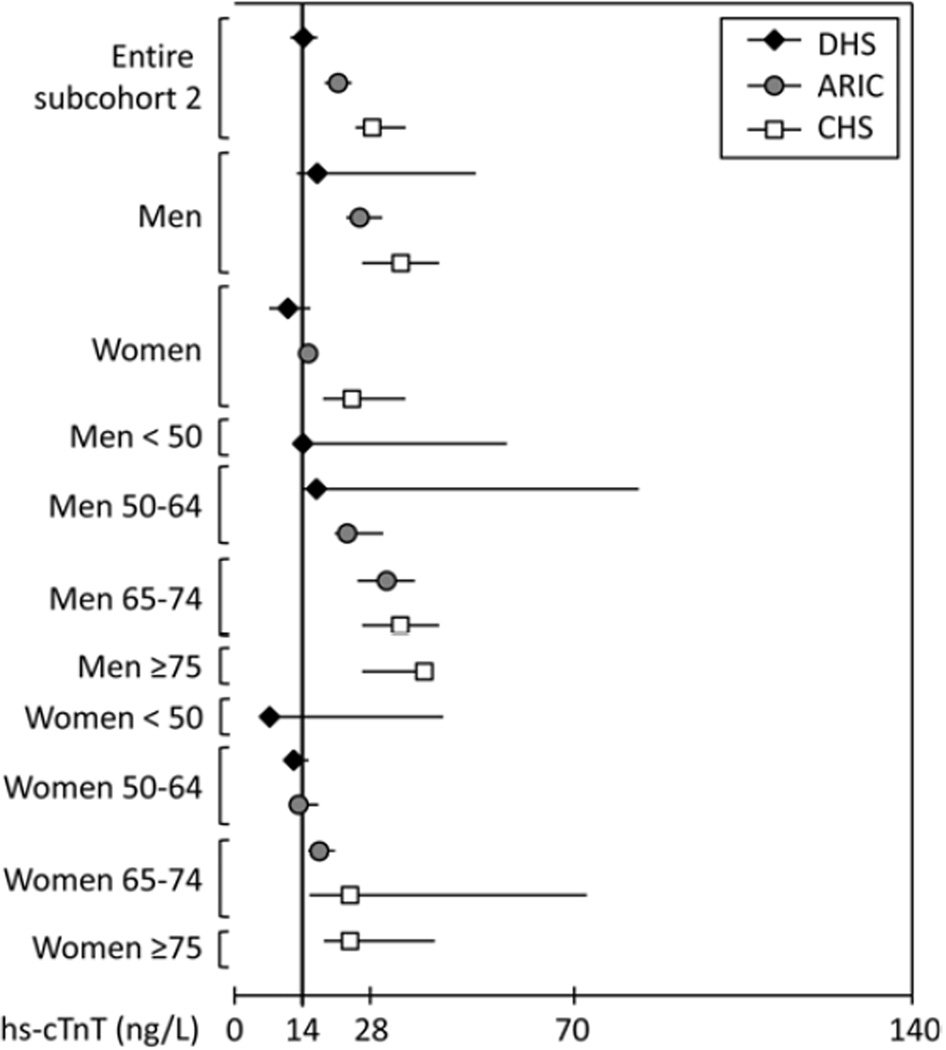

99th percentile values for the hs-cTnT assay

The 99th percentile values for subcohort 1 (representing adults without clinically overt cardiovascular disease or impaired renal function) are presented in Table 2 and Figure 1, with data for subcohort 2 (those additionally free from subclinical structural heart disease or an elevated NT-proBNP) correspondingly shown in Table 3 and Figure 2. The 99th percentile values were significantly higher than 14 ng/L (95% confidence intervals do not cross 14 ng/L) in subcohort 1 for all three studies, and in subcohort 2 for all studies except DHS. Moreover, the 99th percentile values were significantly > 14 ng/L in all strata of men ≥ 50 years and women ≥ 65 years. Importantly, 99th percentile values were consistent across cohorts within age and sex strata.

Table 2.

The 99th percentile values and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) for hs-cTnT and percentiles corresponding to cTnT = 14 ng/L in subcohorts 1* of DHS, ARIC and CHS, with further stratification by sex, age and race.

| DHS | ARIC | CHS | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 99th hs- cTnT percentile [95% CI] (ng/L) |

Percentile for hs- cTnT 14 ng/L |

N | 99th hs- cTnT percentile [95% CI] (ng/L) |

Percentile for hs- cTnT 14 ng/L |

N | 99th hs- cTnT percentile [95% CI] (ng/L) |

Percentile for hs- cTnT 14 ng/L |

||

| Entire subcohort 1 | 2955 | 18 [16, 23] | 98.3 | 7788 | 22 [20, 24] | 95.8 | 1875 | 36 [30, 42] | 90.9 | |

| Stratified by sex | ||||||||||

| Men | 1346 | 23 [19, 47] | 97.1 | 3023 | 28 [24, 35] | 91.7 | 695 | 39 [34, 44] | 83.5 | |

| Women | 1609 | 12 [9, 18] | 99.2 | 4765 | 16 [15, 17] | 98.4 | 1180 | 34 [24, 41] | 95.3 | |

| Stratified by sex and age | ||||||||||

| Men <50 | 992 | 19 [14, 50] | 98.2 | 0 | N/A | N/A | 0 | N/A | N/A | |

| Men 50–64 | 339 | 28 [23, 83] | 94.0 | 2030 | 24 [21, 31] | 93.3 | 0 | N/A | N/A | |

| Men 65–74 | 15 | N/A | N/A | 992 | 35 [27, 49] | 88.4 | 404 | 36 [28, 59] | 87.5 | |

| Men ≥75 | 0 | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A | 291 | 77 [34, 173] | 77.7 | |

| Women <50 | 1149 | 9 [7, 43] | 99.3 | 0 | N/A | N/A | 0 | N/A | N/A | |

| Women 50–64 | 448 | 14 [12, 21] | 99.2 | 3246 | 14 [13, 17] | 99.0 | 0 | N/A | N/A | |

| Women 65–74 | 12 | N/A | N/A | 1519 | 18 [15, 21] | 88.4 | 695 | 25 [17, 45] | 96.9 | |

| Women ≥75 | 0 | N/A | N/A | 0 | N/A | N/A | 485 | 40 [24, 79] | 92.7 | |

| Stratified by sex, age and race | ||||||||||

| Men <50, Black | 445 | 20 [17, 87] | 97.4 | 0 | N/A | N/A | 0 | N/A | N/A | |

| Men <50, Non-black | 547 | 14 [11, 17] | 99.0 | 0 | N/A | N/A | 0 | N/A | N/A | |

| Men 50–64, Black | 175 | 28 [23, 31] | 91.0 | 389 | 31 [24, 53] | 89.7 | 0 | N/A | N/A | |

| Men 50–64, Non-black | 164 | 29 [12, 83] | 97.5 | 1641 | 22 [19, 29] | 94.2 | 0 | N/A | N/A | |

| Men 65–74, Black | 8 | N/A | N/A | 119 | 37 [37, 79] | 78.2 | 66 | 35 [19, 35] † | 83.5 | |

| Men 65–74, Non-black | 7 | N/A | N/A | 873 | 30 [24, 47] | 89.9 | 338 | 36 [28, 59] | 88.3 | |

| Men ≥75, Black | 0 | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A | 52 | 73 [26, 73]† | 80.5 | |

| Men ≥75, Non-black | 0 | N/A | N/A | 0 | N/A | N/A | 239 | 46 [32, 71] | 77.1 | |

| Women <50, Black | 584 | 15 [8, 20] | 99.0 | 0 | N/A | N/A | 0 | N/A | N/A | |

| Women <50, Non-black | 565 | 7 [5, 19] | 99.4 | 0 | N/A | N/A | 0 | N/A | N/A | |

| Women 50–64, Black | 241 | 13 [12, 21] | 99.2 | 837 | 14 [13, 50] | 99.0 | 0 | N/A | N/A | |

| Women 50–64, Non-black | 207 | 14 [09, 15] | 99.0 | 2409 | 14 [13, 17] | 99.0 | 0 | N/A | N/A | |

| Women 65–74, Black | 7 | N/A | N/A | 298 | 17 [15, 21] | 96.6 | 131 | 58 [15, 72] | 95.9 | |

| Women 65–74, Non-black | 5 | N/A | N/A | 1221 | 18 [16, 24] | 97.5 | 564 | 24 [17, 36] | 97.1 | |

| Women ≥75, Black | 0 | N/A | N/A | 0 | N/A | N/A | 93 | 79 [20, 79] † | 91.0 | |

| Women ≥75, Non-black | 0 | N/A | N/A | 0 | N/A | N/A | 392 | 35 [23, 53] | 93.0 | |

Subcohort 1: Subjects free from recent hospitalization (6 months), clinical CVD (CHD, CHF, atrial fibrillation, prior stroke), and stage III or greater CKD (eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73m2).

99th percentile is equivalent to maximum observed value.

Figure 1. The 99th percentile values for the hs-cTnT assay in subcohorts 1 of DHS, ARIC and CHS, with further stratification by sex and age.

Subcohorts 1 include subjects free from recent hospitalization (6 months), clinical CVD (CHD, CHF, atrial fibrillation, prior stroke), and stage III or greater CKD (eGFR < 60 cc/min/1.73m2). Whiskers represent 95% confidence intervals.

Table 3.

The 99th percentile value for the hs-cTnT assay, with 95% confidence intervals (CI), and percentiles corresponding to cTnT = 14 ng/L in subcohorts 2* of DHS, ARIC and CHS, with further stratification by sex, age and race.

| DHS | ARIC | CHS | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 99th hs- cTnT percentile [95% CI] (ng/L) |

Percentile for hs- cTnT 14 ng/L |

N | 99th hs- cTnT percentile [95% CI] (ng/L) |

Percentile for hs- cTnT 14 ng/L |

N | 99th hs- cTnT percentile [95% CI] (ng/L) |

Percentile for hs- cTnT 14 ng/L |

||

| Entire subcohort 1 | 1978 | 14 [12, 17] | 99.0 | 7575 | 21 [19, 22] | 95.9 | 1374 | 28 [25, 35] | 93.5 | |

| Stratified by sex | ||||||||||

| Men | 873 | 17 [13, 5] | 98.5 | 2972 | 26 [23, 30] | 91.9 | 489 | 34 [26, 42] | 87.4 | |

| Women | 1105 | 11 [7, 15] | 99.4 | 4603 | 15 [14, 17] | 98.6 | 885 | 24 [18, 35] | 96.8 | |

| Stratified by sex and age | ||||||||||

| Men <50 | 651 | 14 [12, 56] | 98.8 | 0 | N/A | N/A | 0 | N/A | N/A | |

| Men 50–64 | 216 | 17 [14, 83] | 98.1 | 2000 | 23 [21, 30] | 93.5 | 0 | N/A | N/A | |

| Men 65–74 | 6 | N/A | N/A | 971 | 31 [25, 37] | 88.7 | 297 | 34 [26, 42] | 89.5 | |

| Men ≥75 | 0 | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A | 192 | 39 [26, 39] | 83.9 | |

| Women <50 | 790 | 7 [5, 43] | 99.4 | 0 | N/A | N/A | 0 | N/A | N/A | |

| Women 50–64 | 310 | 12 [11, 15] | 99.3 | 3154 | 13 [13, 17] | 99.1 | 0 | N/A | N/A | |

| Women 65–74 | 5 | N/A | N/A | 1449 | 17 [15, 21] | 97.6 | 551 | 24 [15, 73] | 97.7 | |

| Women ≥75 | 0 | N/A | N/A | 0 | N/A | N/A | 334 | 24 [18, 41] | 95.2 | |

| Stratified by sex, age and race | ||||||||||

| Men <50, Black | 232 | 23 [14, 87] | 97.9 | 0 | N/A | N/A | 0 | N/A | N/A | |

| Men <50, Non-black | 419 | 13 [9, 56] | 99.3 | 0 | N/A | N/A | 0 | N/A | N/A | |

| Men 50–64, Black | 90 | 21 [16, 21] † | 95.6 | 378 | 31 [24, 53] | 89.7 | 0 | N/A | N/A | |

| Men 50–64, Non-black | 126 | 12 [12, 83] | 99.2 | 1622 | 21 [18, 29] | 94.5 | 0 | N/A | N/A | |

| Men 65–74, Black | 1 | N/A | N/A | 113 | 37 [37, 79] | 78.8 | 50 | 35 [20, 35] † | 83.8 | |

| Men 65–74, Non-black | 5 | N/A | N/A | 858 | 27 [23, 35] | 90.1 | 247 | 32 [26, 42] | 90.6 | |

| Men ≥75, Black | 0 | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A | 49 | 25 [22, 25] † | 81.7 | |

| Men ≥75, Non-black | 0 | N/A | N/A | 0 | N/A | N/A | 153 | 39 [26, 39] | 84.4 | |

| Women <50, Black | 355 | 6 [5, 51] | 99.4 | 0 | N/A | N/A | 0 | N/A | N/A | |

| Women <50, Non-black | 435 | 7 [5, 51] | 99.5 | 0 | N/A | N/A | 0 | N/A | N/A | |

| Women 50–64, Black | 141 | 12 [11, 12] | N/A ‡ | 802 | 13 [12, 49] | 99.1 | 0 | N/A | N/A | |

| Women 50–64, Non-black | 169 | 15 [09, 15] | 98.8 | 2352 | 13 [13, 17] | 99.1 | 0 | N/A | N/A | |

| Women 65–74, Black | 2 | N/A | N/A | 288 | 17 [15, 21] | 96.5 | 114 | 66 [15, 73] | 95.3 | |

| Women 65–74, Non-black | 3 | N/A | N/A | 1161 | 17 [15, 21] | 97.9 | 437 | 18 [13, 36] | 98.3 | |

| Women ≥75, Black | 0 | N/A | N/A | 0 | N/A | N/A | 70 | 20 [13, 20] † | 96.0 | |

| Women ≥75, Non-black | 0 | N/A | N/A | 0 | N/A | N/A | 264 | 28 [18, 41] | 94.6 | |

Subcohort 2: Subjects free from recent hospitalization (6 months), clinical CVD (CHD, CHF, atrial fibrillation, prior stroke), subclinical CVD (LVH or LVEF < 55% by echo or MRI, LVH by ECG, NT-proBNP > 450 ng/L), and stage III or greater CKD (eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73m2).

99th percentile is equivalent to maximum observed value.

There was no hs-cTnT value ≥ 14 ng/L in this subgroup.

Figure 2. The 99th percentile values for the hs-cTnT assay in subcohorts 2 of DHS, ARIC and CHS, with further stratification by sex and age.

Sucohorts 2 include subjects free from recent hospitalization (6 months), clinical CVD (CHD, CHF, atrial fibrillation, prior stroke), subclinical CVD (LVH or LVEF < 55% by echo or MRI, LVH by ECG, NT-proBNP > 450 pg/mL), and stage III or greater CKD (eGFR < 60 cc/min/1.73m2). Whiskers represent 95% confidence intervals.

The 99th percentile cutpoints were higher in men compared with women, and increased in subgroups of increasing age among both men and women. Analyses stratified by race showed generally higher 99th percentile values for black versus non-black individuals, particularly among men and older women (≥ 65 years).

Percentiles corresponding to cTnT = 14 ng/L

Tables 2 and 3 also include the percentiles corresponding to a cTnT level of 14 ng/L in each subcohort and sex/age/race stratum. These percentiles were numerically lower than the 99th percentile in all overall subcohorts except subcohort 2 of DHS. Moreover, the percentile values corresponding to 14 ng/L were consistently lower in men compared with women, decreased with increasing age in both men and women, and were lower in black versus non-black men and older women.

Sensitivity analyses in DHS

To determine the sensitivity of our findings to components used for the definition of the subcohort free from clinical or subclincal cardiovascular disease, we performed sensitivity analyses by modifying individual exclusion criteria for DHS subcohort 2, with additional stratification by sex, race and age. As shown in Table 4, no major differences were observed in the 99th percentile cTnT values when the NT-proBNP exclusion cutoff for subcohort 2 was changed from 450 ng/L to 125 ng/L, or when the NT-proBNP or ECG exclusion criteria were removed. In contrast, when exclusions based on cardiac imaging for LVH or LV systolic dysfunction were removed, the 99th percentile values increased among men, older individuals, and black participants (Table 4).

Table 4.

The 99th percentile values for the hs-cTnT assay (ng/L) stratified by sex, age and race in DHS subcohort 2*: Sensitivity analyses.

| DHS Subcohort 2 |

Change NT-proBNP exclusion cutoff from 450 ng/L to 125 ng/L |

Remove NT- proBNP Exclusion |

Remove ECG LVH exclusion |

Remove exclusions based on cardiac imaging for LVH or LVEF < 55% |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 14 (N = 1978) | 14 (N = 1872) | 14 (N = 1981) | 14 (N = 2121) | 14 (N = 2703) | |

| Men | 17 (N = 873) | 17 (N = 861) | 17 (N = 873) | 17 (N = 957) | 23 (N = 1205) | |

| Women | 11 (N = 1105) | 9 (N = 1011) | 12 (N = 1108) | 11 (N = 1164) | 11 (N = 1498) | |

| Age <50 | 13 (N=1441) | 13 (N = 1384) | 13 (N=1441) | 13 (N = 1538) | 14 (N = 1985) | |

| Age 50–64 | 15 (N=526) | 15 (N = 480) | 15 (N=529) | 15 (N = 570) | 21 (N = 697) | |

| Black | 16 (N = 821) | 16 (N = 789) | 16 (N = 823) | 17 (N = 931) | 21 (N = 1261) | |

| Non-black | 13 (N=1157) | 13 (N = 1083) | 13 (N=1158) | 13 (N = 1190) | 14 (N = 1442) | |

Subcohort 2: Subjects free from recent hospitalization (6 months), clinical CVD (CHD, CHF, atrial fibrillation, prior stroke), subclinical CVD (LVH or LVEF < 55% by MRI, LVH by ECG, NT-proBNP > 450 ng/L), and stage III or greater CKD (eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73m2).

Discussion

The key finding from this study is that a uniform upper reference limit for the hs-cTnT assay of 14 ng/L, as currently recommended for MI diagnosis, does not reflect the 99th percentile value of a reference population with diverse demographic characteristics. This study unequivocally demonstrates in a very large and well-characterized population that 99th percentile values for the hs-cTnT assay are greater in men and rise notably with increasing age in both men and women. New sex- and age- specific cutoff values for the hs-cTnT assay are proposed, and will require clinical validation. We also found that 99th percentile values are generally higher in black compared with non-black individuals. Although no race-specific cutoff values can be reliably derived from the present dataset, our findings clearly indicate that race may influence hs-cTnT assay cutoff values.

The upper reference limit for the hs-cTnT assay

By convention, an increased cardiac troponin concentration is defined as a measurement exceeding the 99th percentile value for the specific assay within a normal reference population (6,7). However, there is no consensus with regard to the criteria for selecting a reference population, and the definition of “normal” in this context remains a matter of continuing debate (3,5,8).

A recent statement by the International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine Task Force on Clinical Applications of Cardiac Biomarkers (3) recommended that “normal” populations used to derive the 99th percentile of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin assays should ideally be selected by detailed physician evaluation, including electrocardiogram, echocardiogram and NT-proBNP measurement, and should include both younger and older subjects. The present report is the first to meet (and surpass) these recommendations, far exceeding the size and thus the statistical power of any previous study that determined the 99th percentile upper reference limit of the hs-cTnT assay.

Importantly, 99th percentile values for the hs-cTnT assay were lower in this study when participants with subclinical structural heart disease were excluded (subcohort 2), compared with the use of less stringent exclusion criteria (subcohort 1). These differences were magnified in older individuals, who are more likely to have subclinical cardiovascular disease. Taken together with the results of our sensitivity analyses, these findings support assessment of subclinical structural heart disease to further characterize the reference population in future studies.

The case for sex- and age-specific hs-cTnT cutoff values

Several small studies have previously reported trends towards higher 99th percentile values for both the hs-cTnT and hs-cTnI assays in men (8–15) and in the elderly (9,11,14), but small sample sizes and inconsistent phenotype characterization preclude the derivation of sex- and age-specific clinical cutoff values from these studies. The most recent update to the consensus definition of MI suggested that sex-dependent cutoff values may be endorsed in the future for hs-cTn assays (7), but in the absence of reliable data, no specific numeric recommendation was made.

Based on our findings, the cutoff value for the hs-cTnT assay should remain 14 ng/L only for men younger than 50 years and for women younger than 65 years. Of note, the true 99th percentile cTnT value for women younger than 50 may be lower than 14 ng/L, but validating a lower cutoff is not feasible with the current assay because the coefficient of variation of the assay exceeds 10% at values of 13 ng/L and lower. Utilizing the most conservative estimates from our study (i.e. the lowest reported 99th percentile value from multiple studies with data for subcohort 2 within a given age/sex strata, as shown in Table 3), we propose that cutoff values for the hs-cTnT assay be increased to 17 ng/L for men aged 50–64 and for women aged 65 or older, and to 31 ng/L for men aged 65 or older.

Further research is imperative to determine whether these age- and sex-specific cutoff values improve diagnostic performance for MI, both in prospective studies and in post-hoc analyses of existing databases. In addition, further studies are necessary to determine whether age- and sex-specific cutoffs should also be considered for hs-cTnI assays.

Limitations

This was a retrospective study, but selection bias is unlikely given the population-based nature of DHS, ARIC and CHS. Nevertheless, prospective validation of the revised cutoff values proposed in this study is critically important. Race and ethnicity were not uniformly recorded for Hispanic/Latino individuals across the three cohorts, and there was a low number of black individuals in several age and race strata, thus precluding the derivation of race-specific cutoff values for the hs-cTnT assay. Measurements were performed in sample aliquots stored at −70°C for a variable amount of time, and some cTnT loss is possible with long term freezing (27). However, any such loss would have led to an underestimation, not overestimation of the 99th percentiles. Because of this potential for underestimation, our recommendations to increase cutoff values for the hs-cTnT assay in men and the elderly may in fact be too conservative, and the values may be upwardly revised in the future as more data become available. For example, a recent study of 406 consecutive patients over 70 years of age with symptoms suggestive of acute MI reported that the optimal hs-cTnT assay cutoff for early diagnosis of MI was 54 ng/L, as determined by Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis. This value is higher than our age-specific recommendations, and is almost four times higher than the presently recommended “one size fits all” upper reference limit (28).

Clinical Implications

More than 10% of men older than 65 years in our study who were free from clinical or subclinical cardiovascular disease had cTnT values above the current MI threshold. This suggests that clinical use of the hs-cTnT assay with the currently recommended cutpoint may result in over-diagnosis of MI, particularly in elderly men.

The Universal Definition of MI recommends performing serial measurements of troponins and emphasizes the importance of rising and/or falling levels to distinguish acute MI from other sources of troponin elevation (7). When considered together with baseline levels, moderate changes in cTnT over serial timepoints improve specificity for MI with the hs-cTnT assay (29). However, it is important to note that the operating characteristics of changes in cTnT values are contingent on whether baseline cTnT is above the MI detection threshold. Thus, an inaccurate upper reference limit for the hs-cTnT assay would be expected to impact the performance of all algorithms for MI diagnosis

Use of more accurate, sex- and age-specific 99th percentile values for the hs-cTnT assay would be expected to decrease false positive MI diagnosis with the hs-cTnT assay, a problem with major clinical and public health ramifications (30,31).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff and participants of the DHS, ARIC and CHS studies for their important contributions.

Sources of funding: The Dallas Heart Study was supported by the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation (Las Vegas, NV) and by grant UL1-TR000451 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study is carried out as a collaborative study supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) contracts HHSN268201100005C through HHSN268201100012C. The Cardiovascular Health Study was supported NHLBI grant HL080295 and by NHLBI contracts N01-HC-85239, N01-HC-85079 through N01-HC-85086; N01-HC-35129, N01 HC-15103, N01 HC-55222, N01-HC-75150, and N01-HC-45133, with additional support from the National Institute of Aging (AG-023629, AG-15928, AG-20098, and AG-027058). M.O. Gore is supported by training grant T32-HL007360 from the NHLBI.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure: Drs. Seliger, deFilippi, Nambi, Christenson, Ballantyne, Hoogeveen and de Lemos received grant funding from Roche Diagnostics. Dr. Seliger and Dr. de Lemos have received consulting fees from Roche Diagnostics. Dr. deFilippi has received honoraria and consulting fees from Roche Diagnostics.

References

- 1.Wu AH, Jaffe AS. The clinical need for high-sensitivity cardiac troponin assays for acute coronary syndromes and the role for serial testing. Am Heart J. 2008;155:208–214. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reichlin T, Hochholzer W, Bassetti S, et al. Early diagnosis of myocardial infarction with sensitive cardiac troponin assays. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:858–867. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Apple FS, Collinson PO. Analytical characteristics of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin assays. Clin Chem. 2012;58:54–61. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2011.165795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thygesen K, Mair J, Giannitsis E, et al. How to use high-sensitivity cardiac troponins in acute cardiac care. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2252–2257. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Korley FK, Jaffe AS. Preparing the United States for High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin Assays. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:1753–1758. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giannitsis E, Kurz K, Hallermayer K, Jarausch J, Jaffe AS, Katus HA. Analytical validation of a high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T assay. Clinical Chem. 2010;56:254–261. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.132654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1581–1598. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collinson PO, Heung YM, Gaze D, et al. Influence of population selection on the 99th percentile reference value for cardiac troponin assays. Clin Chem. 2012;58:219–225. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2011.171082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saenger AK, Beyrau R, Braun S, et al. Multicenter analytical evaluation of a highsensitivity troponin T assay. Clin Chim Acta. 2011;412:748–754. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mingels A, Jacobs L, Michielsen E, Swaanenburg J, Wodzig W, van Dieijen-Visser M. Reference population and marathon runner sera assessed by highly sensitive cardiac troponin T and commercial cardiac troponin T and I assays. Clin Chem. 2009;55:101–108. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.106427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chenevier-Gobeaux C, Meune C, Blanc MC, Cynober L, Jaffray P, Lefevre G. Analytical evaluation of a high-sensitivity troponin T assay and its clinical assessment in acute coronary syndrome. Annals of clinical biochemistry. 2011;48:452–458. doi: 10.1258/acb.2011.011019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Apple FS, Ler R, Murakami MM. Determination of 19 cardiac troponin I and T assay 99th percentile values from a common presumably healthy population. Clin Chem. 2012;58:1574–1581. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.192716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Apple FS, Simpson PA, Murakami MM. Defining the serum 99th percentile in a normal reference population measured by a high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I assay. Clin Biochem. 2010;43:1034–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKie PM, Heublein DM, Scott CG, et al. Defining high-sensitivity cardiac troponin concentrations in the community. Clin Chem. 2013;59:1099–1107. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.198614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keller T, Ojeda F, Zeller T, et al. Defining a reference population to determine the 99th percentile of a contemporary sensitive cardiac troponin I assay. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:1423–1429. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Lemos JA, Drazner MH, Omland T, et al. Association of troponin T detected with a highly sensitive assay and cardiac structure and mortality risk in the general population. JAMA. 2010;304:2503–2512. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saunders JT, Nambi V, de Lemos JA, et al. Cardiac troponin T measured by a highly sensitive assay predicts coronary heart disease, heart failure, and mortality in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Circulation. 2011;123:1367–1376. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.005264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.deFilippi CR, de Lemos JA, Christenson RH, et al. Association of serial measures of cardiac troponin T using a sensitive assay with incident heart failure and cardiovascular mortality in older adults. JAMA. 2010;304:2494–2502. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Victor RG, Haley RW, Willett DL, et al. The Dallas Heart Study: a population-based probability sample for the multidisciplinary study of ethnic differences in cardiovascular health. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;93:1473–1480. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.02.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The ARIC investigators. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: design and objectives. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129:687–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fried LP, Borhani NO, Enright P, et al. The Cardiovascular Health Study: design and rationale. Ann Epidemiol. 1991;1:263–276. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(91)90005-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Troponin T hs and Troponin T hs STAT Product Information Brochure, Elecsys 2010 System, Roche Diagnostics. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hallermayer K, Jarausch J, Menassanch-Volker S, Zaugg C, Ziegler A. Implications of adjustment of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T assay. Clin Chem. 2013;59:572–574. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.197103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Apple FS, Jaffe AS. Clinical implications of a recent adjustment to the high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T assay: user beware. Clin Chem. 2012;58:1599–1600. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.194985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barnes SC, Collinson PO, Galasko G, Lahiri A, Senior R. Evaluation of N-terminal pro-B type natriuretic peptide analysis on the Elecsys 1010 and 2010 analysers. Ann Clin Biochem. 2004;41:459–463. doi: 10.1258/0004563042466848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:461–470. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Basit M, Bakshi N, Hashem M, et al. The effect of freezing and long-term storage on the stability of cardiac troponin T. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:164–167. doi: 10.1309/LR7FC0LUGLHT8X6J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reiter M, Twerenbold R, Reichlin T, et al. Early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction in the elderly using more sensitive cardiac troponin assays. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1379–1389. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reichlin T, Irfan A, Twerenbold R, et al. Utility of absolute and relative changes in cardiac troponin concentrations in the early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2011;124:136–145. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.023937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Lemos JA, Morrow DA, deFilippi CR. Highly sensitive troponin assays and the cardiology community: a love/hate relationship? Clin Chem. 2011;57:826–829. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2011.163758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Lemos JA. Increasingly sensitive assays for cardiac troponins: a review. JAMA. 2013;309:2262–2269. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.5809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]