Abstract

Background

To examine temporal trends in emergency departments (ED) visits for bronchiolitis among US children between 2006 and 2010.

Methods

Serial, cross-sectional analysis of the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample, a nationally-representative sample of ED patients. We used ICD-9-CM code 466.1 to identify children <2 years of age with bronchiolitis. Primary outcome measures were rate of bronchiolitis ED visits, hospital admission rate, and ED charges.

Results

Between 2006 and 2010, weighted national discharge data included 1,435,110 ED visits with bronchiolitis. There was a modest increase in the rate of bronchiolitis ED visits, from 35.6 to 36.3 per 1000 person-years (2% increase; Ptrend=0.008), due to increases in the ED visit rate among children from 12 months to 23 months (24% increase; Ptrend<0.001). By contrast, there was a significant decline in the ED visit rate among infants (4% decrease; Ptrend<0.001) Although unadjusted admission rate did not change between 2006 and 2010 (26% in both years), admission rate declined significantly after adjusting for potential patient- and ED-level confounders (adjusted OR for comparison of 2010 with 2006, 0.84; 95%CI, 0.76-0.93; P<0.001). Nationwide ED charges for bronchiolitis increased from $337 million to $389 million (16% increase; Ptrend<0.001), adjusted for inflation. This increase was driven by a rise in geometric mean of ED charges per case from $887 to $1059 (19% increase; Ptrend<0.001).

Conclusions

Between 2006 and 2010, we found a divergent temporal trend in the rate of bronchiolitis ED visits by age group. Despite a significant increase in associated ED charges, ED-associated hospital admission rates for bronchiolitis significantly decreased over this same period.

Keywords: bronchiolitis, emergency department, incidence, hospitalization, charge

Introduction

Bronchiolitis is a major public health problem in the United States. Almost all children are exposed to respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and other causes of bronchiolitis1 and approximately 40% of children develop clinical bronchiolitis during the first two years of life.2,3 The majority of children with bronchiolitis have mild illness, but some children present to the emergency department (ED), and others require hospitalization.4,5 In 2009, bronchiolitis led to approximately 130,000 hospitalizations, with total direct cost of $550 million.6

For the last two decades, ED visit rates in the US have increased by more than a third as EDs have increasingly served as an acute diagnostic and treatment center, a primary safety net, and a 24/7 portal for rapid hospital admission.7,8 For children with bronchiolitis, a previous study estimated a stable temporal trend in national ED visit rates between 1992 and 2000.9 More recent studies demonstrated increasing trends in the early 2000's, however, within a local population,10 and within patients with RSV only.11 Although RSV is the most common cause of bronchiolitis, many other infectious agents are associated with bronchiolitis.12-14 Therefore, estimates derived from samples of RSV bronchiolitis would underestimate health care utilization and expenditures.15 Since there have been no recent efforts to assess temporal trends in the rate of bronchiolitis-related ED visits, hospital admission rate, and ED charges, we used a nationally-representative study to examine temporal trends in ED visits in children with bronchiolitis between 2006 and 2010,

Materials and Methods

Study design and setting

We conducted a serial cross-sectional analysis of data from the 2006-2010 Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS),16 a component of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The HCUP-NEDS is nationally representative of all community hospital-based EDs in the United States, which is defined by the American Hospital Association as all nonfederal, short-term, general, and other specialty hospitals.16 The NEDS was constructed by using administrative records from the HCUP State Emergency Department Databases and the State Inpatient Databases. The State Emergency Department Databases capture information on ED visits that do not result in an admission (i.e., treat-and-release visits or transfers to another hospital); the State Inpatient Databases contain information on patients initially seen in the ED and then admitted to the same hospital. Taken together, the resulting NEDS represents all ED visits regardless of disposition and contains information on short-term outcomes for patients admitted through the ED. The NEDS is the largest all-payer ED and inpatient database in the United States. The NEDS represents an approximately 20% stratified sample of US hospital-based EDs, containing more than 28 million records of ED visits from approximately 1,000 hospitals each year. Weights are available to obtain national estimates at the ED visit and hospital level, pertaining to nearly 130 million ED visits. Additional details of the NEDS can be found elsewhere.16 The institutional review board of Massachusetts General Hospital approved this analysis.

Study population

ED visits for patients age <2 years who had an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code for bronchiolitis (466.1) in the primary or secondary diagnosis fields were eligible for our analysis. We included children with bronchiolitis in the secondary diagnosis field to avoid underestimation of this clinical diagnosis. Prior work shows potential overlap with pneumonia and potential difficulty distinguishing between bronchiolitis and early asthma in children aged <2 years.17

Patient- and ED-level variables

The NEDS contains information on patient demographics, ED visit day, diagnoses and procedures, total charge for ED and/or inpatient services, ED disposition, and hospital disposition. Socioeconomic status was estimated using national quartiles for median household income based on the patient's ZIP code and primary insurance (payer).16 We grouped primary payer into public sources (Medicaid and Medicare), private payers, self-pay, and other types. Diagnoses and procedures were available using ICD-9-CM and Clinical Classifications Software (CCS), a methodology developed by AHRQ to group ICD-9-CM codes into clinically sensible and mutually exclusive categories. High-risk medical condition was defined as history of prematurity (i.e., ≤36 weeks of gestation) or at least 1 complex medical condition, previously defined using ICD-9-CM codes in 9 categories of illness (e.g., neuromuscular, cardiovascular, and respiratory).18

Hospital characteristics include annual visit volume, US region, urban-rural status, and teaching status. Annual volume of bronchiolitis cases for each ED was calculated; EDs in the top quartile of bronchiolitis volume were labeled as high-bronchiolitis-volume ED. Geographic regions (Northeast, South, Midwest, and West) were defined according to Census Bureau boundaries.19 Urban-rural status of the ED was defined according to the Urban Influence Codes.20

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measures were rates of bronchiolitis-related ED visits, hospital admission rates, and charges for ED services. Other outcomes of interest included in-hospital (ED and inpatient) use of mechanical ventilation, hospital length of stay, and in-hospital all-cause mortality. Admission rate was defined as proportion of hospital admissions among all bronchiolitis ED visits. Total ED charges reflected the total facility fees reported for each discharge record. In-hospital all-cause mortality was defined as the number of deaths divided by total number of bronchiolitis. Use of mechanical ventilation (non-invasive or invasive) was identified with CCS code 216.

Statistical analysis

We described changes in the outcomes from 2006 through 2010. We calculated the rate of ED visits using population estimates obtained from the US Census Bureau.21 ED visit rates were expressed as the number of estimated ED visits per 1000 children of the corresponding age group per year. Additionally, to address a possibility that diagnostic transfer may partially explain the temporal trend in the rate of bronchiolitis ED visits, we also examined temporal trends for pneumonia and asthma by using CCS code 122 and 128 in the primary or secondary diagnosis field, respectively. To test for temporal trend in the ED visit rates, we used Poisson regression models.

To facilitate direct comparisons between years for ED and overall charges, we converted all charges to 2010 US dollars using the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index.22 Because charges were not normally distributed, we calculated the weighted geometric mean and median of charges.23 The geometric mean is the average of the logarithmic values of a data set, which is then converted back to a base-ten number; it is less influenced by extreme values than the arithmetic mean. We estimated total charges as a weighted sum of case-level charges. We used linear regression models for log-transformed charges to test for temporal trends.

To examine temporal trends in admission rate and charges for ED services, we fit two analytical models. First, we developed an unadjusted model that included only calendar year as the independent variable. Second, we examined the association between calendar year and each outcome using multivariable logistic regression. We adjusted for both patient-level variables (i.e., age, sex, quartiles for median household income, primary payer, admission day, and high-risk medical conditions) and ED-level (annual volume of bronchiolitis cases, region, urban and rural distinction, and hospital teaching status). The model was fit by using generalized estimating equations to account for clustering of discharges within hospitals. Incorporating sampling weight is generally not advised for multi-level modeling in the HCUP data because it complicates an already-complicated estimation procedure, possibly for little or no gain.24 Thus, the unweighted bronchiolitis cohort was analyzed in the multivariable models.

We then conducted a series of sensitivity analyses to assess the consistency of temporal trend in each outcome among diagnostic subgroups. First, to minimize the potential misclassification of asthma, we repeated the analysis in cases with bronchiolitis in children <12 months of age (infants). Second, we conducted the analysis for cases with both primary diagnosis of bronchiolitis aged <12 months and no high-risk conditions.

All analyses used SUDAAN version 11.0 (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC) to obtain descriptive statistics accounting for the complex sampling design, and SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) for multi-level modeling. Two-sided P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient and ED characteristics

We identified a total of 313,566 ED visits for bronchiolitis in US, corresponding to a weighted estimate of 1,435,110 ED visits between 2006 and 2010. This accounted for 4.3% (95% confidence interval [CI], 4.2%-4.5%) of all ED visits for children <2 years. Between 2006 and 2010, the annual proportion of bronchiolitis ED visits among the total ED visits was relatively constant (Ptrend=0.20).

The patient and ED characteristics of the population of children with bronchiolitis are shown in Table 1. Infants accounted for three-fourths of bronchiolitis ED visits; most were male. Patients with the lowest quartile for median household income contributed one-third of ED visits. In more recent years, children with bronchiolitis were less likely to be age <12 months, and more likely to have a public insurance (both Ptrend ≤0.01). Children with public insurance contributed two-thirds of bronchiolitis ED visits in 2010.

Table 1. Patient and Emergency Department Characteristics of US Children Presenting to the ED with Bronchiolitis, 2006-2010.

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | P for Trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unweighted sample, N | 59,462 | 63,319 | 64,296 | 63,194 | 63,295 | |

| Weighted sample, N | 284,959 | 293,046 | 286,986 | 283,204 | 286,915 | |

| Percentage (95% confidence interval) unless otherwise indicated | ||||||

| Patient-level variable | ||||||

| Age (month) | <0.001 | |||||

| 0-11.9 | 78 (76-79) | 77 (76-78) | 76 (74-77) | 75 (73-76) | 73 (72-74) | |

| 12-23.9 | 22 (21-24) | 23 (22-24) | 24 (23-26) | 26 (24-27) | 27 (26-28) | |

| Male sex | 58 (58-59) | 59 (58-59) | 59 (58-59) | 59 (58-59) | 59 (58-59) | 0.58 |

| Quartile for median household income of patient's ZIP code | ||||||

| 1 (lowest) | 34 (30-38) | 36 (33-40) | 35 (31-38) | 37 (33-41) | 33 (29-38) | 0.44 |

| 2 | 27 (25-29) | 28 (26-30) | 30 (28-33) | 30 (27-33) | 30 (27-33) | 0.23 |

| 3 | 22 (20-25) | 22 (20-24) | 22 (19-24) | 20 (18-22) | 23 (20-26) | 0.46 |

| 4 (highest) | 16 (14-20) | 14 (12-16) | 14 (11-16) | 13 (11-15) | 14 (12-17) | 0.28 |

| Type of health insurance | ||||||

| Medicaid and Medicare | 62 (60-64) | 60 (57-64) | 59 (55-63) | 64 (61-67) | 66 (63-68) | 0.01 |

| Private | 29 (27-31) | 30 (26-34) | 31 (27-34) | 28 (25-30) | 26 (24-29) | 0.22 |

| Self-pay | 6 (5-7) | 6 (5-6) | 8 (6-9) | 6 (5-7) | 5 (4-6) | 0.009 |

| Other | 4 (2-6) | 3 (2-4) | 4 (3-5) | 3 (2-4) | 3 (3-4) | 0.41 |

| ED visit day | 0.06 | |||||

| Weekday* | 68 (67-68) | 69 (68-69) | 68 (68-69) | 68 (67-68) | 68 (67-68) | |

| Weekend | 32 (32-33) | 31 (31-32) | 32 (31-32) | 32 (32-33) | 32 (32-33) | |

| High-risk condition† | 2 (2-3) | 3 (2-3) | 3 (2-3) | 2 (2-3) | 3 (2-3) | 0.31 |

| Emergency Department-level variable | ||||||

| Total ED visit volume, median (IQR) | 53,931 (37,799-76,627) | 51,753 (34,124-70,204) | 55,322 (38,081-80,803) | 54,771 (37,721-81,889) | 55,724 (36,223-84,958) | 0.14 |

| High-bronchiolitis-volume ED | 82 (79-86) | 82 (78-85) | 83 (79-86) | 82 (72-84) | 81 (77-84) | 0.93 |

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast | 16 (11-22) | 15 (11-20) | 15 (11-20) | 18 (14-23) | 15 (11-19) | 0.68 |

| Midwest | 24 (17-32) | 23 (16-32) | 24 (18-31) | 23 (18-29) | 19 (15-24) | 0.71 |

| South | 36 (28-44) | 35 (28-42) | 35 (29-43) | 40 (33-47) | 39 (32-47) | 0.77 |

| West | 25 (17-35) | 27 (20-36) | 26 (18-35) | 19 (15-25) | 27 (20-36) | 0.24 |

| Location/teaching status | ||||||

| Metropolitan teaching | 59 (51-67) | 53 (45-61) | 52 (45-60) | 51 (45-58) | 52 (44-60) | 0.59 |

| Metropolitan non-teaching | 28 (22-34) | 33 (27-40) | 33 (27-40) | 33 (28-39) | 33 (27-39) | 0.64 |

| Non-metropolitan | 13 (10-26) | 14 (11-17) | 14 (12-18) | 15 (12-19) | 16 (13-19) | 0.62 |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; IQR, interquartile range.

ED visit on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday.

High-risk medical condition was defined as history of prematurity or at least 1 complex medical condition, previously defined using ICD-9-CM codes in 9 categories of illness (i.e., neuromuscular, cardiovascular, respiratory, renal, gastrointestinal, hematology or immunologic, metabolic, malignancy, and other congenital or genetic defect disorders).

Temporal trends in rates of bronchiolitis ED visits

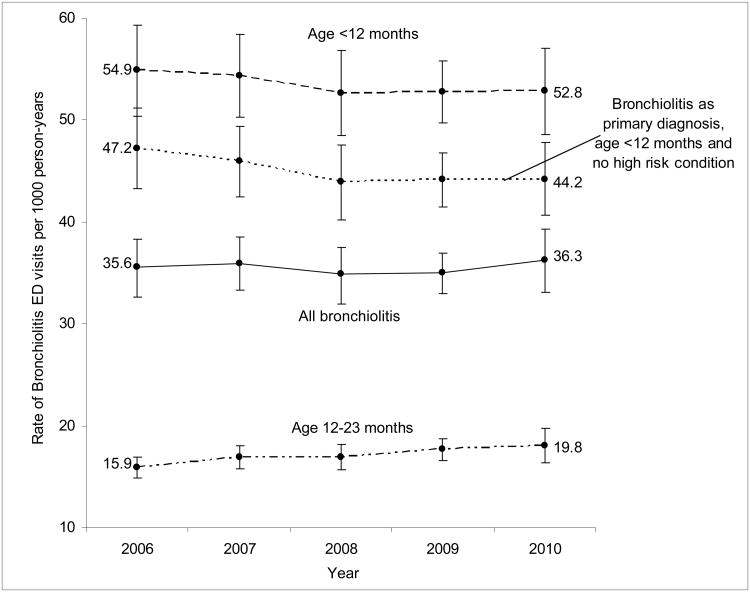

Between 2006 and 2010, there was a modest increase in the rate of bronchiolitis ED visits, from 35.6 (95%CI, 32.9-38.5) to 36.3 (95%CI, 33.3-39.5) per 1000 person-years (2% increase; Ptrend=0.008; Figure). This finding was due largely to an increase in the ED visit rate among children from 12 months to 23 months (24% increase; Ptrend<0.001). By contrast, there was a significant decline in the ED visit rate among infants (4% decrease; Ptrend<0.001).

Figure. Rates of US ED Visits for Bronchiolitis per 1000 Children, According to Age Group and Different Definitions; 2006-2010.

Between 2006 and 2010, there was a significant increase in the overall rate of bronchiolitis ED visits among children age <2 years (2% increase; Ptrend=0.008), and the subgroup of children from 12 months to 23 months (24% increase; Ptrend<0.001). By contrast, there was a significant decline in the rate among children age <12 months (4% decrease; Ptrend<0.001), and the subgroup of children age <12 month with bronchiolitis as the primary diagnosis and no high-risk medical conditions (6% decrease; Ptrend<0.001). I bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

To determine if a shift in diagnostic preference could have played a role in the increase in bronchiolitis ED visit rate, pneumonia and asthma ED visits were examined. Among children from 12 months to 23 months, the increase in bronchiolitis ED visit rate was mirrored by decreases in that for pneumonia and asthma (all Ptrend≤0.01; see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/INF/B674). By contrast, among infants, the decrease in bronchiolitis ED visits was paralleled by decreases in that for pneumonia and asthma (all Ptrend<0.001; see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/INF/B675).

Temporal trends in hospital admission and clinical outcomes for bronchiolitis

Between 2006 and 2010, the unadjusted hospital admission rate after an ED visit for bronchiolitis did not change significantly (26% both in 2006 and 2010; odds ratio [OR] for comparison of 2010 with 2006, 0.98; 95%CI, 0.82-1.17; Table 2 and Table 3). By contrast, the multivariable-adjusted admission rate declined significantly (adjusted OR for comparison of 2010 with 2006, 0.84; 95%CI, 0.76-0.93; P<0.001; Table 3). Patient-level risk factors for hospital admission were younger age, female sex, higher household income, having public and private insurance (compared to self-pay), ED visits on weekdays, and presence of high-risk medical conditions; ED-level factors were EDs with high bronchiolitis volume, in northeast or west regions, and with metropolitan teaching or non-metropolitan status. Similarly, we observed a consistent, significant decline in adjusted admission rate across all diagnostic subgroups (Table 4). Use of non-invasive or invasive mechanical ventilation did not change (Ptrend=0.41; Table 2). Likewise, hospital length of stay and overall mortality did not change significantly during the study period.

Table 2. Clinical Outcomes and Charges for Emergency Department Services among US Children Presenting to the Emergency Department with Bronchiolitis, 2006-2010.

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | P for Trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 284,959 | 293,046 | 286,986 | 283,204 | 286,915 | |

| Admission, % (95% CI) | 26 (24-28) | 28 (25-30) | 25 (22-28) | 24 (22-27) | 26 (23-28) | 0.06 |

| Mechanical ventilation, % (95% CI) | 4 (3-7) | 4 (2-6) | 4 (2-6) | 6 (4-9) | 5 (3-8) | 0.41 |

| Length of stay (day), median (IQR) | 3 (1-5) | 2 (1-4) | 2 (1-5) | 3 (1-6) | 3 (1-5) | 0.52 |

| Overall mortality, % (95% CI) | 0.02 (0.01-0.03) | 0.01 (0.00-0.03) | 0.01 (0.00-0.02) | 0.01 (0.00-0.02) | 0.01 (0.00-0.02) | 0.31 |

| Charge for ED services per visit $, geometric mean (95% CI) | 887 (824-950) | 933 (872-991) | 933 (875-991) | 1048 (979-1116) | 1059 (971-1147) | <0.001 |

| Total charges $ (millions), 95%CI | 337 (315-358) | 357 (333-381) | 356 (318-395) | 389 (364-413) | 389 (359-419) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; CI, confidence interval; IQR, interquartile range

Table 3. Unadjusted and Multivariable Models of Hospital Admission Rates and Charge for Emergency Department Services among Children Presenting to Emergency Department with Bronchiolitis, 2006-2010.

| Admission Rate | Charges for ED services* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted model | Multivariable model | Unadjusted model | Multivariable model | |||||

| Variable | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | % change (95% CI) | ||||||

| Calendar year | ||||||||

| 2006 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 2007 | 1.09 (0.94 to 1.27) | 0.96 (0.90 to 1.02) | 5 (-3 to 14) | 9 (6 to12) | ||||

| 2008 | 0.96 (0.80 to 1.14) | 0.92 (0.85 to 0.99) | 5 (-3 to 13) | 15 (11 to 19) | ||||

| 2009 | 0.92 (0.79 to 1.07) | 0.89 (0.82 to 0.97) | 17 (8-25) | 23 (19 to 27) | ||||

| 2010 | 0.98 (0.82 to 1.17) | 0.84 (0.76 to 0.93) | 18 (7-28) | 25 (20 to 29) | ||||

| Age (month) | ||||||||

| 0-11.9 | - | 1.41 (1.36 to 1.46) | - | -2 (-1 to -3) | ||||

| 12-23.9 | - | Reference | - | Reference | ||||

| Female sex | - | 1.03 (1.00 to 1.05) | - | -1 (-1 to -2) | ||||

| Quartile for median household in come of patient's ZIP code | ||||||||

| 1 (lowest) | - | Reference | - | Reference | ||||

| 2 | - | 1.07 (1.03 to 1.14) | - | 0 (-1 to 1) | ||||

| 3 | - | 1.15 (1.09 to 1.20) | - | 0 (-1 to 1) | ||||

| 4 (highest) | - | 1.29 (1.22 to 1.38) | - | 1 (-0 to 3) | ||||

| Type of health insurance | ||||||||

| Medicaid and Medicare | - | 2.00 (1.75 to 2.27) | - | 25 (20 to 29) | ||||

| Private | - | 2.00 (1.73 to 2.32) | - | 6 (3 to 8) | ||||

| Self-pay | - | Reference | - | Reference | ||||

| Other | - | 1.58 (1.27 to 1.97) | - | 5 (1 to 8) | ||||

| ED visit day | ||||||||

| Weekday (vs. weekend) | - | 1.16 (1.14 to 1.19) | - | 2 (1 to 2) | ||||

| High-risk condition† | 7.84 (7.14 to 8.61) | 16 (11 to 20) | ||||||

| High-bronchiolitis-volume ED | - | 1.95 (1.68 to 2.27) | - | -14 (-7 to -22) | ||||

| Region | ||||||||

| Northeast | - | 1.51 (1.27 to 1.79) | - | 2 (-4 to 8) | ||||

| Midwest | - | Reference | - | Reference | ||||

| South | - | 1.02 (0.88 to 1.18) | - | 6 (1 to 11) | ||||

| West | - | 1.27 (1.08 to 1.50) | - | 6 (-4 to 15) | ||||

| Location/teaching status | ||||||||

| Metropolitan teaching | - | 1.23 (1.10 to 1.37) | - | 8 (2 to 13) | ||||

| Metropolitan non-teaching | - | Reference | - | Reference | ||||

| Non-metropolitan | - | 1.53 (1.32 to 1.77) | - | -37 (-33 to -29) | ||||

Abbreviations: CI confidence interval; ED emergency department.

Bold results are statistically significant.

Linear regression models of log-transformed charges for ED services.

High-risk medical condition was defined as at least 1 complex medical condition, previously defined using ICD-9-CM codes in 9 categories of illness (i.e., neuromuscular, cardiovascular, respiratory, renal, gastrointestinal, hematology or immunologic, metabolic, malignancy, and other congenital or genetic defect disorders).

Table 4. Clinical Outcomes among US Children Presenting to the Emergency Department with Bronchiolitis, According to Different Definitions; 2006-2010.

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | P for Trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age <12 months | ||||||

| Number of patient | 221,889 | 225,462 | 217,711 | 211,099 | 208,815 | |

| Admission, % (95% CI) | 28 (25-30) | 30 (27-32) | 27 (24-30) | 27 (24-29) | 27 (25-30) | 0.28 |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI)* | Reference | 0.95 (0.89-1.02) | 0.91 (0.84-0.98) | 0.89 (0.81-0.97) | 0.82 (0.74-0.90) | |

| Mechanical ventilation, % (95% CI) | 4 (3-7) | 3 (2-6) | 4 (2-6) | 6 (4-10) | 5 (3-8) | 0.39 |

| Length of stay (day) median (IQR) | 3 (1-6) | 2 (1-4) | 2 (1-5) | 3 (1-6) | 3 (1-5) | 0.47 |

| Overall mortality, % (95% CI) | 0.02 (0.01-0.04) | 0.01 (0.00-0.02) | 0.01 (0.01-0.03) | 0.01 (0.00-0.02) | 0.01 (0.00-0.03) | 0.51 |

| Charge for ED services per visit ($), geometric mean (95% CI) | 890 (826-954) | 939 (874-1004) | 934 (874-994) | 1055 (982-1127) | 1066 (975-1157) | <0.001 |

| Adjusted % change (95% CI)* | Reference | 10 (6-13) | 15 (11-19) | 23 (19-28) | 25 (20-29) | |

| Total charges $ (millions), (95% CI) | 264 (247-281) | 276 (257-296) | 271 (243-299) | 292 (273-311) | 286 (263-309) | |

| Bronchiolitis as primary diagnosis, age <12 months and no high risk condition | ||||||

| Number of patient | 190 814 | 190 513 | 181 457 | 176 636 | 174 650 | |

| Admission, % (95% CI) | 27 (25-29) | 29 (27-31) | 25 (22-28) | 25 (22-27) | 25 (22-27) | 0.11 |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI)* | Reference | 0.97 (0.89-1.05) | 0.85 (0.78-0.92) | 0.83 (0.75-0.90) | 0.74 (0.65-0.83) | |

| Mechanical ventilation, % (95% CI) | 4 (3-7) | 3 (2-6) | 3 (2-5) | 6 (4-10) | 5 (3-8) | 0.36 |

| Length of stay (day) median (IQR) | 3 (1-6) | 2 (1-4) | 2 (1-5) | 3 (1-6) | 3 (1-5) | 0.44 |

| Overall mortality, % (95% CI) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Charge for ED services per visit ($), geometric mean (95% CI) | 892 (828-956) | 938 (872-1004) | 926 (865-988) | 1051 (978-1124) | 1062 (967-1156) | <0.001 |

| Adjusted % change (95% CI)* | Reference | 10 (6-13) | 15 (11-19) | 23 (18-27) | 24 (19-29) | |

| Total charges $ (millions), (95% CI) | 226 (212-240) | 232 (216-249) | 225 (199-251) | 243 (227-260) | 239 (219-259) | |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; IQR, interquartile range

−, not reported as the number of observations in each year is less than or equal to 10.

Models adjusting for the following patient and hospital characteristics: sex, median household income, insurance status, ED visit day, presence of high-risk medical condition, high-bronchiolitis-volume ED, US region, urban/rural status, and teaching status.

Temporal trends in ED charges

Between 2006 and 2010, the total national charges for bronchiolitis ED visits increased from approximately $337 million (95%CI, $315-$358 million) to $389 million (95%CI, $359-$419 million), adjusted for inflation (16% increase; Ptrend<0.001; Table 2). Infants accounted for three-fourths of this annual charge ($286 million in 2010; 95%CI, $263-$309 million; Table 4). The geometric mean of ED charges per case increased from $887 (95%CI, $824-$950) to $1059 (95%CI, $971-$1147; 19% increase; Ptrend<0.001).

Table 3 demonstrates multivariable regression results for predictors of ED charges. In particular, the mean charge per ED visit was higher for more recent years (25 % higher for comparison of 2010 with 2006; 95%CI, 20%-29%; P<0.001) and children with public insurance (25% higher; 95%CI, 20%-29%; P<0.001). By contrast, the mean charge was lower for patients seen in EDs with high bronchiolitis volume (14% lower; 95%CI, 7%-22%; P<0.001).

Dicussion

In a nationally-representative sample of more than 300,000 actual ED visits by children with bronchiolitis, we found a divergent temporal trend in the rate of bronchiolitis ED visits between 2006 and 2010. Concurrent with these trends were a significant decrease in hospital admission rates and an increase in ED charges. The observed increase in ED charges was partially explained by differences in comorbidities; however, multivariable analysis demonstrated that insurance status and several ED characteristics were strong predictors of ED charges in children with bronchiolitis.

Previous studies reported an increase in rates of bronchiolitis ED visits in the early 2000s within the Tennessee Medicaid population10 and among patients with RSV infection.11 The NEDS provides a nationally-representative sample that better addresses the public health burden of bronchiolitis in US children. Between 2006 and 2010, our study demonstrated an increased ED visit rate among children from 12 months to 23 months and a decline among infants. The reasons for these temporal trends are unclear and likely multifactorial. Changes in the rate of ED visits could reflect true trends in disease incidence and severity. Alternatively, non-biological factors may have contributed, such as altered access to primary care, healthcare-seeking behaviors, and changes in the organization of medical services that favor rapid diagnostic technologies and early treatment available in the ED. Furthermore, the observed increase in bronchiolitis ED visit rate among older children was mirrored by decreases in that for pneumonia and asthma. Therefore, it is possible that diagnostic transfer explains, at least in part, the increase in bronchiolitis ED visit rates in this subgroup. By contrast, we found a significant decline in the ED visit rate in infants, paralleled by decreases in that for pneumonia and asthma. Thus, it is difficult to postulate that diagnostic transfer fully explains the decrease in infants.

A recent study reported a decrease in the incidence of bronchiolitis hospitalizations through the 2000s in US.6 Similarly, we found a significant decline in the adjusted hospital admission rate among US children with bronchiolitis across different definitions of the disease. This temporal trend occurred without an increase in mortality, and has many possible contributing factors, including changes in the criteria for hospitalizations, availability and utilization of healthcare in the community, use of supplemental oxygen at ED discharge, and severity of disease.25 Additionally, a previous study reported a decrease in use of chest x-rays for ED patients with the availability of the 2006 American Academy of Pediatrics practice guidelines,26 which might have led to fewer diagnoses of pneumonia and hospitalizations. Alternatively, the decline may have been driven by alterations in coding practice, with less severe cases of bronchiolitis being recognized and coded in more recent years. However, the concurrent decrease in the rate of ED visits and admission among infants and patients with “classic” bronchiolitis (i.e., primary diagnosis of bronchiolitis in infants without high-risk medical conditions) argues against this possibility.

We also demonstrated significant contributions of socioeconomic status to hospital admission rates among US children with bronchiolitis. This finding was consistent with prior studies reporting higher admission rates associated with Medicaid-insured patients.27,28 By contrast, and inconsistent with the previous investigations,29-31 we found a novel association between higher household incomes and higher admission rates. Furthermore, we believe our study is the first to demonstrate significant variation in hospital admission rate across US regions. This degree of variation is not unique to bronchiolitis, in that substantial variation in rates have documented for number of diseases.32,33 The previous investigations within local populations reported possible contributing factors, such as differences in environmental factors, physician density, practice patterns, and healthcare access.30,31,34,35

We are struck by the finding that national ED charges related to bronchiolitis increased over time, even after adjusting for inflation. Despite the public health burden of bronchiolitis, there have been no recent studies examining temporal trends in ED charges. Using different definitions of bronchiolitis (i.e., infants with primary diagnosis of bronchiolitis or pneumonia), a previous study estimated annual national ED costs of $50 million in 2001 US dollars, although the ED charges would be considerably larger.28 We observed a 16% increase in national charges from $337 million in 2006 to $389 million in 2010. This increase was driven by increases in the average ED charge per case because the volume of bronchiolitis ED visits remained constant during the study period. The reasons for increasing charges per case are likely multifactorial. Potential explanations include changes in disease severity, more ED resource use, overuse of medications and chest x-rays, and changes in hospital billing practices.36-38 Additionally, a wide variation in diagnosis and management for bronchiolitis among clinicians might, in part, contribute to this phenomenon.9,17,36,38 In our study, the ED charges were partly explained by annual bronchiolitis volume within the ED after adjusting for case-mix and other ED characteristics. Thus, the association between the EDs with higher bronchiolitis volume and lower charges might result from the factors other than patient and ED characteristics, such as greater provider experience and streamlined systems of care contributing to less routine use of bronchodilators, radiographs, and laboratory tests.

Potential limitations

These findings should be interpreted in the context of the study design. First, our study was ED-based and not population-based; many individuals may report to non-ED settings for bronchiolitis, such as outpatient office visits.10,11 Therefore, our observations do not represent the true incidence of the disease but rather the incidence of ED visits for bronchiolitis. Second, we used an administrative database of discharge-level data, without clinical information beyond that captured in ICD-9-CM codes. We might have underestimated or overestimated the frequency of bronchiolitis ED-visits due to potential overlap with pneumonia, and potential difficulty distinguishing between bronchiolitis and early asthma.17 However, we conducted sensitivity analyses to address this issue. Third, a lack of patient identifiers precluded us from examining longer-term outcomes, such as return ED visits. It is possible that a small proportion of patients might have reported to EDs multiple times in the same year. Lastly, as with any observational study, the observed decline in hospital admission rate might be confounded by unmeasured factors, such as disease severity; maternal age and infant birth weight; favorable changes in household crowding, or parental smoking; and immunoprophylaxis with palivizumab for high-risk children.39-43

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Rates of US ED Visits for Bronchiolitis, Pneumonia, and Asthma per 1000 Children From 12 Months to 23 Months; 2006-2010 We identified children from 12 months to 23 months with pneumonia using the Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) code 122 and those with asthma using CCS code 128 in the primary or secondary diagnosis fields. Between 2006 and 2010, there was a significant increase in the rate of bronchiolitis ED visits among children from 12 months to 23 months (24% increase; Ptrend<0.001). By contrast, there was a significant decline in the rate of pneumonia ED visits (1% decrease; Ptrend=0.01) and asthma ED visits (5% decrease; Ptrend<0.001). I bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Figure S2. Rates of US ED Visits for Bronchiolitis, Pneumonia, and Asthma per 1000 Children Younger Than 12 Months; 2006-2010 We identified children <12 months with pneumonia using the CCS code 122 and those with asthma using CCS code 128 in the primary or secondary diagnosis fields. Between 2006 and 2010, there was a significant decline in the rate of bronchiolitis ED visits among children age <12 months (4% decrease; Ptrend<0.001). Similarly, there was a significant decline in the rate of pneumonia ED visits (5% decrease; Ptrend<0.001) and asthma ED visits (19% decrease; Ptrend<0.001). I bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding: Dr. Hasegawa was supported, in part, by Eleanor and Miles Shore Fellowship Program (Boston, MA). Dr. Tsugawa was supported, in part, by St. Luke's Life Science Institute (Tokyo). Drs. Mansbach and Camargo were supported, in part, by NIH U01 AI- 87881 (Bethesda, MD). The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Glezen WP, Taber LH, Frank AL, Kasel JA. Risk of primary infection and reinfection with respiratory syncytial virus. Am J Dis Child. 1986;140(6):543–546. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1986.02140200053026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levine DA, Platt SL, Dayan PS, et al. Risk of serious bacterial infection in young febrile infants with respiratory syncytial virus infections. Pediatrics. 2004;113(6):1728–1734. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.6.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yorita KL, Holman RC, Sejvar JJ, Steiner CA, Schonberger LB. Infectious disease hospitalizations among infants in the United States. Pediatrics. 2008;121(2):244–252. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bialy L, Foisy M, Smith M, Fernandes RM. The Cochrane Library and the treatement of bronchiolitis in Children: an overview of reviews. Evid-Based Child Health. 2011;6:258–275. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robbins JM, Kotagal UR, Kini NM, Mason WH, Parker JG, Kirschbaum MS. At-home recovery following hospitalization for bronchiolitis. Ambul Pediatr. 2006;6(1):8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hasegawa K, Tsugawa Y, Brown DF, Mansbach JM, Camargo CA., Jr Trends in bronchiolitis hospitalizations in the United States, 2000-2009. Pediatrics. 2013 Jun 6; doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schuur JD, Venkatesh AK. The growing role of emergency departments in hospital admissions. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):391–393. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1204431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang N, Stein J, Hsia RY, Maselli JH, Gonzales R. Trends and characteristics of US emergency department visits, 1997-2007. JAMA. 2010;304(6):664–670. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mansbach JM, Emond JA, Camargo CA., Jr Bronchiolitis in US emergency departments 1992 to 2000: epidemiology and practice variation. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2005;21(4):242–247. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000161469.19841.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carroll KN, Gebretsadik T, Griffin MR, et al. Increasing burden and risk factors for bronchiolitis-related medical visits in infants enrolled in a state health care insurance plan. Pediatrics. 2008;122(1):58–64. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall CB, Weinberg GA, Iwane MK, et al. The burden of respiratory syncytial virus infection in young children. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(6):588–598. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zorc JJ, Hall CB. Bronchiolitis: recent evidence on diagnosis and management. Pediatrics. 2010;125(2):342–349. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mansbach JM, Piedra PA, Teach SJ, et al. Prospective multicenter study of viral etiology and hospital length of stay in children with severe bronchiolitis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(8):700–706. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mansbach JM, McAdam AJ, Clark S, et al. Prospective multicenter study of the viral etiology of bronchiolitis in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15(2):111–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2007.00034.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pelletier AJ, Mansbach JM, Camargo CA., Jr Direct medical costs of bronchiolitis hospitalizations in the United States. Pediatrics. 2006;118(6):2418–2423. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; [Accessed April 1, 2013]. HCUP Nationwide Emergency Department Sample. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nedsoverview.jsp. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mansbach JM, Espinola JA, Macias CG, Ruhlen ME, Sullivan AF, Camargo CA., Jr Variability in the diagnostic labeling of nonbacterial lower respiratory tract infections: a multicenter study of children who presented to the emergency department. Pediatrics. 2009;123(4):e573–581. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feudtner C, Hays RM, Haynes G, Geyer JR, Neff JM, Koepsell TD. Deaths attributed to pediatric complex chronic conditions: national trends and implications for supportive care services. Pediatrics. 2001;107(6):E99. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.6.e99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.United States Bureau of the Census. Census regions and divisions of the United States. [Accessed April 1, 2013]; http://www.census.gov/geo/www/us_regdiv.pdf.

- 20.United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. The 2003 Urban Influence Codes. [Accessed April 1, 2013]; http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/urban-influence-codes.aspx.

- 21.US Census Bereau. Population estimates. [Accessed April 1, 2013]; http://www.census.gov/popest/

- 22.Consumer Price Index. United States Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. [Accessed April 1, 2013]; http://www.bls.gov/cpi/home.htm.

- 23.Lagu T, Rothberg MB, Shieh MS, Pekow PS, Steingrub JS, Lindenauer PK. Hospitalizations, costs, and outcomes of severe sepsis in the United States 2003 to 2007. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(3):754–761. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232db65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hierarchical modeling using HCUP data Report no 2007-01. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; [Accessed February 15, 2013]. HCUP Methods Serias. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/methods/2007_01.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Halstead S, Roosevelt G, Deakyne S, Bajaj L. Discharged on supplemental oxygen from an emergency department in patients with bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e605–610. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson LW, Robles J, Hudgins A, Osburn S, Martin D, Thompson A. Management of bronchiolitis in the emergency department: impact of evidence-based guidelines? Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):S103–109. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1427m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sangare L, Curtis MP, Ahmad S. Hospitalization for respiratory syncytial virus among California infants: disparities related to race, insurance, and geography. J Pediatr. 2006;149(3):373–377. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leader S, Kohlhase K. Recent trends in severe respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) among US infants, 1997 to 2000. J Pediatr. 2003;143(5 Suppl):S127–132. doi: 10.1067/s0022-3476(03)00510-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jansson L, Nilsson P, Olsson M. Socioeconomic environmental factors and hospitalization for acute bronchiolitis during infancy. Acta Paediatr. 2002;91(3):335–338. doi: 10.1080/08035250252834021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson DW, Adair C, Brant R, Holmwood J, Mitchell I. Differences in admission rates of children with bronchiolitis by pediatric and general emergency departments. Pediatrics. 2002;110(4):e49. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.4.e49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McConnochie KM, Roghmann KJ, Liptak GS. Hospitalization for lower respiratory tract illness in infants: variation in rates among counties in New York State and areas within Monroe County. J Pediatr. 1995;126(2):220–229. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(95)70548-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pilote L, Califf RM, Sapp S, et al. Regional variation across the United States in the management of acute myocardial infarction. GUSTO-1 Investigators. Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(9):565–572. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199508313330907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nichol G, Thomas E, Callaway CW, et al. Regional variation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest incidence and outcome. JAMA. 2008 Sep 24;300(12):1423–1431. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.12.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Connell FA, Day RW, LoGerfo JP. Hospitalization of medicaid children: analysis of small area variations in admission rates. Am J Public Health. 1981;71(6):606–613. doi: 10.2105/ajph.71.6.606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holman RC, Curns AT, Cheek JE, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus hospitalizations among American Indian and Alaska Native infants and the general United States infant population. Pediatrics. 2004;114(4):e437–444. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Christakis DA, Cowan CA, Garrison MM, Molteni R, Marcuse E, Zerr DM. Variation in inpatient diagnostic testing and management of bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2005;115(4):878–884. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knapp JF, Simon SD, Sharma V. Quality of care for common pediatric respiratory illnesses in United States emergency departments: analysis of 2005 National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey Data. Pediatrics. 2008;122(6):1165–1170. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Plint AC, Johnson DW, Wiebe N, et al. Practice variation among pediatric emergency departments in the treatment of bronchiolitis. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11(4):353–360. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mansbach JM, Clark S, Christopher NC, et al. Prospective multicenter study of bronchiolitis: predicting safe discharges from the emergency department. Pediatrics. 2008;121(4):680–688. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marlais M, Evans J, Abrahamson E. Clinical predictors of admission in infants with acute bronchiolitis. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96(7):648–652. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.201079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McConnochie KM, Roghmann KJ. Parental smoking, presence of older siblings, and family history of asthma increase risk of bronchiolitis. Am J Dis Child. 1986;140(8):806–812. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1986.02140220088039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.The IMpact-RSV Study Group. Palivizumab, a humanized respiratory syncytial virus monoclonal antibody, reduces hospitalization from respiratory syncytial virus infection in high-risk infants. Pediatrics. 1998;102(3 Pt 1):531–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mansbach JM, Piedra PA, Stevenson MD, et al. Prospective multicenter study of children with bronchiolitis requiring mechanical ventilation. Pediatrics. 2012;130(3):e492–500. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Rates of US ED Visits for Bronchiolitis, Pneumonia, and Asthma per 1000 Children From 12 Months to 23 Months; 2006-2010 We identified children from 12 months to 23 months with pneumonia using the Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) code 122 and those with asthma using CCS code 128 in the primary or secondary diagnosis fields. Between 2006 and 2010, there was a significant increase in the rate of bronchiolitis ED visits among children from 12 months to 23 months (24% increase; Ptrend<0.001). By contrast, there was a significant decline in the rate of pneumonia ED visits (1% decrease; Ptrend=0.01) and asthma ED visits (5% decrease; Ptrend<0.001). I bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Figure S2. Rates of US ED Visits for Bronchiolitis, Pneumonia, and Asthma per 1000 Children Younger Than 12 Months; 2006-2010 We identified children <12 months with pneumonia using the CCS code 122 and those with asthma using CCS code 128 in the primary or secondary diagnosis fields. Between 2006 and 2010, there was a significant decline in the rate of bronchiolitis ED visits among children age <12 months (4% decrease; Ptrend<0.001). Similarly, there was a significant decline in the rate of pneumonia ED visits (5% decrease; Ptrend<0.001) and asthma ED visits (19% decrease; Ptrend<0.001). I bars represent 95% confidence intervals.