Abstract

Purpose

To assess the effect of bevacizumab on connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) and VEGF in ocular fluids of patients with diabetic traction retinal detachment. To determine whether intra- and post-operative complications are decreased in eyes given adjunctive pre-operative bevacizumab.

Methods

Twenty eyes of 19 patients were randomized to receive intravitreal bevacizumab or sham 3–7 days prior to vitrectomy for severe proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Aqueous samples prior to injection and at time of surgery were collected. Undiluted vitreous samples were extracted.

Results

Five eyes had decreased vascularization of membranes from pre-injection to time of surgery (all in treatment arm). Median visual acuity was 20/400 in controls at baseline and 3 months post-op; counts fingers in the treated group at baseline and 20/100 at 3 months (p=0.30 between controls and treated at 3 months). All retinas were attached at post-operative month 3.

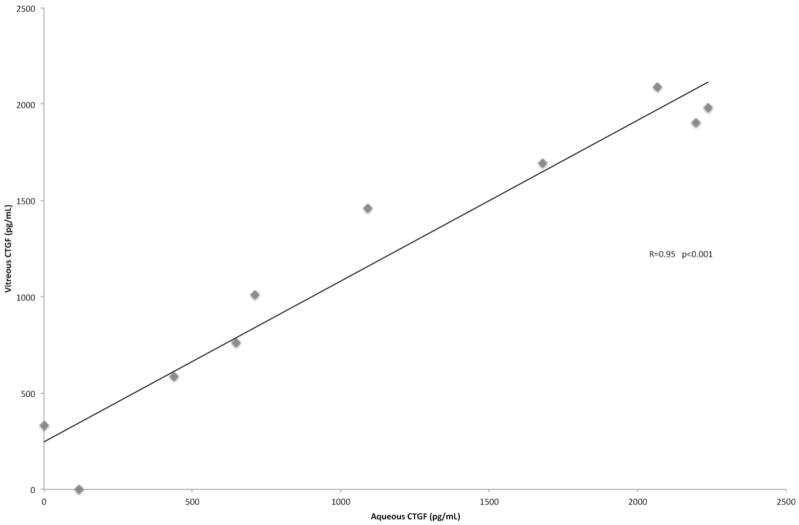

Vitreous levels of VEGF were significantly lower in the bevacizumab group than the control group (p-value=0.03). Vitreous levels of CTGF were slightly lower in the bevacizumab group compared to controls but this was not statistically significant (p-value=0.38). CTGF levels in the aqueous were strongly correlated to those in the vitreous of controls (Spearman correlation coefficient 0.95, p-value<0.001).

Conclusions

Intravitreal bevacizumab reduces vitreous levels of VEGF and produces a clinically observable alteration in diabetic fibrovascular membranes. Ocular fluid levels of CTGF are not significantly affected within the week following VEGF inhibition. Retinal reattachment rates and visual acuity are not significantly altered by pre-operative intravitreal bevacizumab at post-operative month 3.

Introduction

Diabetic retinopathy is the leading cause of blindness for working-age adults in the western world. Retinal detachment can occur in the advanced, proliferative form of diabetic retinopathy (PDR) when epiretinal fibrovascular membranes contract, resulting in traction retinal detachment (TRD).1 Traction retinal detachment requires surgical intervention when the macula is involved or threatened, there is a combined rhegmatogenous component (TRD/RRD), or neovascular glaucoma occurs secondary to TRD and ischemia.

Retinal neovascularization is driven in large part by vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF),2 and VEGF has been identified in aqueous,3 vitreous,4 epiretinal membranes,5 and whole retinas6 of eyes with diabetic retinopathy. Intraocular fibrogenic processes are characterized by inflammation, growth factor production, cellular proliferation and migration, and accumulation and contraction of extracellular matrix.7 However, the precise mechanism of fibrovascular membrane formation causing TRD in PDR is unknown. Recently, connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) has been identified as a mediator of intraocular fibrosis in proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR)8–11 and PDR.9,12,13

It has long been observed that in PDR, new vessels become fibrotic over time and this evolution appears accelerated in some eyes after panretinal photocoagulation. Similarly, intravitreal injection of bevacizumab has been observed to cause regression of neovascularization and accelerated fibrosis, leading to TRD in some patients with PDR.14 It has been proposed that this angiofibrotic ‘switch’ may be mediated by a shift in the balance between VEGF-mediated angiogenesis and pro-fibrotic CTGF.15,16

To better understand the crucial relationship between CTGF and VEGF, we sought to examine angiofibrotic growth factors before and after VEGF inhibition in a randomized, double masked, controlled translational study of patients with TRD due to PDR. It is not known how soon and to what degree ocular CTGF levels change after VEGF inhibition. Based on previous studies examining VEGF and CTGF levels in eyes with PDR,15,16 we expected vitreous CTGF levels to be higher in eyes treated with bevacizumab compared to untreated eyes. However, since we placed the stringent requirement to operate within 7 days of bevacizumab injection (to prevent TRD progression), it was plausible that CTGF levels would be unchanged in this early post-injection period.

The aims of this first report are to: 1) describe study design and summarize patient baseline characteristics; 2) provide early clinical results; 3) determine the levels of two key angiofibrotic growth factors, CTGF and VEGF, in eyes with severe TRD with and without VEGF inhibition and 4) examine the correlation of aqueous to vitreous levels of these growth factors.

Patients and Methods

This prospective, randomized, double-masked, interventional study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Doheny Eye Institute (DEI)/ University of Southern California (USC)+ Los Angeles County (LAC) Hospitals. Clinical trials registration was completed at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01270542). There were two treatment arms to the study: half of enrolled eyes were randomized to receive intravitreal bevacizumab injection (1.25 mg) and the other half received sham injection (controls).

Enrollment

Patients with traction retinal detachment (TRD) or combined traction-rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (TRD/RRD) secondary to PDR who were given anesthesia clearance for pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) at DEI/USC and LAC Hospitals qualified for enrollment. Indications for surgery included TRD involving the macula, TRD/RRD, and non-clearing or recurrent vitreous hemorrhage (VH) precluding complete pan-retinal photocoagulation (PRP) with TRD not necessarily involving the macula. Exclusion criteria were: history of PPV; dense vitreous hemorrhage preventing pre-operative grading of fibrovascular membranes; inability to return for surgery within 3–7 days after randomization; history of stroke, thromboembolic event, or heart attack within six months; age less than 18 years; and pregnancy. At baseline, known herein as the day of enrollment, informed written consent was obtained and the baseline pre-operative evaluation, randomization and intervention (detailed below) were performed.

Clinical assessment

Pre-operative (i.e. prior to randomization) and intra-operative assessments for all patients were performed by a single surgeon (EHS). Complete medical and ophthalmic history was obtained. Last hemoglobin A1C levels were recorded. Best-corrected distance visual acuity (VA) testing was performed by trained ophthalmic personnel using a Snellen chart, pinhole, and refraction. Detailed ophthalmic examination was performed.

Prior to randomization and at time of surgery, the RD was classified as TRD or TRD/RRD and graded based on the extent of hyaloidal attachment: mild (focal vitreoretinal attachment), moderate (broad vitreoretinal attachment), or severe (complete vitreous attachment). Fibrovascular epiretinal proliferative membranes (FVP) causing the TRD were also graded: predominantly neovascular, mixed neovascular and fibrotic, and predominantly fibrotic. At baseline, on the day of surgery, and at 3-months postoperatively, fundus photography and spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (OCT; Topcon 3D-1000) were performed. If clinically significant macular edema was present on slit-lamp biomicroscopy, fluorescein angiography was also performed.

Intervention

All patients were given a subconjunctival 2% lidocaine injection. For eyes randomized to receive intravitreal injection, 1.25 mg in 0.05 mL bevacizumab was administered. Eyes randomized to the control group had a syringe without a needle placed to simulate intravitreal injection. All patients received ocufloxacin eyedrops for 4 days.

Randomization

Both the patient and surgeon were masked to the subjects’ randomization group. At baseline evaluation, the appropriate intervention was performed by the injecting physician (different than the surgeon).

Surgery

Surgery was performed on all patients 3–7 days after baseline. Particular attention was given to changes in vascularity and extent of the FVP (using the same pre-operative grading system described above). Retino-hyaloidal attachments as well as any areas of increased subretinal fluid (i.e. worsening of retinal detachment) were compared to baseline. These findings were detailed in a comprehensive intra-operative record.

All patients had 20 gauge pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) using a combination of delamination and segmentation techniques.17 In some cases where FVP extended anterior to the equator, scleral buckling and/or pars plana lensectomy was performed.18 Extensive PRP was applied in all cases.

Intra-operative bleeding

Amount of bleeding was recorded in the intra-operative record using the following grading system: none, 1=minor bleeding, stopping either spontaneously or with transient bottle elevation, or 2=moderate to severe bleeding, requiring endodiathermy or with formation of broad sheets of clots.

Ocular samples for laboratory analysis

Immediately prior to intraocular injection of bevacizumab (or sham) and on the day of surgery, aqueous was sampled. Undiluted vitreous was also obtained for each patient at the start of surgery. Samples were promptly centrifuged at 10,000 rpm at 4°C, and the supernatants were frozen at −80°C until assayed. Fibrovascular membranes dissected during each vitrectomy were placed in iced balanced salt solution and stored for analysis.

ELISA

VEGF concentrations were assayed by ELISA (Quantikine human VEGF ELISA; R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. CTGF levels were obtained using the pre-coated human CTGF ‘Super X’ ELISA kit from Antigenix American Inc. For each assay, standard curves were performed to determine the appropriate dilution factor (1:5 for CTGF and 1:10 for VEGF).

Statistics

To study the difference between bevacizumab and control group median VEGF levels in the aqueous and vitreous, Wilcoxon Rank Sum test p-value (as distributions were not normal) was performed; independent samples t-test for mean CTGF levels was calculated. Spearman correlation coefficient analysis was done to correlate levels of CTGF and VEGF to each other and to compare the aqueous and vitreous concentrations of these growth factors.

Analysis of visual acuity only included subjects who had 3 months follow-up. Visual acuity was converted to logmar: for counts fingers the best-corrected VA was considered equivalent to 1/200 where logmar VA = 2.3. For hand motions VA, light perception and no light perception, logmar VAs were assigned 3.3, 4.3, 5.3 respectively. Wilcoxon Rank Sum test was used to compare median visual acuity at individual time points between treated and controls. Frequency of visual acuity change was determined with Fisher’s Exact test.

Data monitoring and safety

Periodic data monitoring and safety assessments were maintained on a regular basis by a clinical trials quality assurance coordinator.

Results

Clinical

Twenty eyes of 19 patients at LA County Hospital were enrolled in the study. The demographics and clinical information are listed in Table 1. Median age was 52 years. Twelve patients were male. All eyes had pan-retinal photocoagulation performed previously. Ten eyes received intravitreal bevacizumab and 10 were controls. Five eyes had moderate TRD, 8 had severe TRD, and 7 had combined TRD/RRD. Four of the five eyes with moderate TRD were randomized to the control group. Pre-operative best-corrected visual acuity (VA) ranged from 20/70 to hand motion in the bevacizumab group (median 8/200) and 20/150 to counting fingers in the control group (median 20/400). There was no statistically significant difference in pre-operative VA between the two arms. Additional details at are listed in Table 2.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical information of enrolled patients

| Age | Sex | Eye | Arm | Pre-op TRD severity | Inj->op | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 64 | F | OS | C | moderate TRD | 3 | |

| 2 | 42 | M | OS | B | severe TRD | 3 | |

| 3 | 47 | M | OS | B | TRD/RRD | 5 | |

| 4 | 31 | M | OD | C | moderate TRD | 4 | |

| 5 | 62 | M | OS | C | severe TRD | 6 | |

| 6 | 45 | M | OD | B | severe TRD | 6 | |

| 7 | 57 | F | OD | C | TRD/RRD | 4 | |

| 8 | 46 | F | OD | B | TRD/RRD | 4 | |

| 9 | 62 | M | OD | B | TRD/RRD | 4 | |

| 10 | 57 | M | OD | C | moderate TRD | 4 | |

| 11 | 54 | F | OD | C | severe TRD | 3 | |

| 12 | 38 | M | OD | B | TRD/RRD | 4 | |

| 13 | 62 | M | OS | B | severe TRD | 6 | |

| 14 | 53 | F | OD | C | TRD/RRD | 3 | |

| 15 | 43 | F | OD | C | TRD/RRD | 6 | |

| 16 | 56 | M | OD | B | severe TRD/SR bands | 3 | |

| 17 | 42 | M | OS | C | moderate TRD | 3 | |

| 18 | 43 | M | OD | B | severe TRD | 6 | |

| 19 | 54 | F | OS | C | severe TRD | 4 | OS of #11 |

| 20 | 51 | F | OD | B | moderate TRD | 4 |

M=male; F female; TRD=traction retinal detachment; RRD=rhegmatogenous retinal detachment

OS=left eye; OD=right eye; C=control; B=bevacizumab; SR=subretinal

IT=inferotemporal; Inj->op=days from injection to operation

Table 2.

Pre-operative, intra-operative, and post-operative month 3 results with vitreous VEGF and CTGF levels

| Arm | Pre-op TRD type | Intra-op TRD | Vitreous VEGF | Vitreous CTGF | Bleeding | Pre-op VA | POM3 VA | Gas or oil | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | C | fibrosis | fibrosis | 0 | 1983 | 1 | 20/150 | 20/150 | none |

| 2 | B | fibrosis | fibrosis | 0 | 268 | 2 | 8/200 | 20/50-1 | gas |

| 3 | B | mixed NV-fibrosis | all fibrosis | 0 | 1051 | 1 | HM | dropped out | oil |

| 4 | C | fibrosis | fibrosis | 660 | 1009 | 2 | 20/400 | 4/200 | none |

| 5 | C | fibrosis | fibrosis | 248 | 2089 | 1 | 4/200 | CF | oil |

| 6 | B | fibrosis | fibrosis | 0 | 522 | 1 | 5/200 | 20/80 | gas |

| 7 | C | fibrosis | fibrosis | 1031 | 0 | 2 | CF | LP | oil |

| 8 | B | fibrosis except NV in IT arcade | all fibrosis | 0 | 966 | 2 | CF | HM | oil |

| 9 | B | fibrosis except NV above disc | all fibrosis | 0 | 0 | 1 | HM | HM | gas |

| 10 | C | fibrosis | fibrosis | 268 | 331 | 2 | 20/400 | 20/400 | gas |

| 11 | C | fibrosis | fibrosis | 124 | 760 | 1 | 20/150 | 20/50-1 | gas |

| 12 | B | mixed NV-fibrosis | all fibrosis | 0 | 993 | 1 | 1/200 | 20/40-2 | gas |

| 13 | B | mixed NV-fibrosis | mixed | 0 | 440 | 2 | 20/70 | 20/30-2 | gas |

| 14 | C | fibrosis | fibrosis | 527 | 588 | 2 | 20/400 | dropped out | oil |

| 15 | C | fibrosis | fibrosis | 527 | 1694 | 1 | 8/200 | 20/400 | gas |

| 16 | B | fibrosis | fibrosis | 559 | 1300 | 2 | 20/400 | 20/400 | gas |

| 17 | C | fibrosis | fibrosis | 74 | 1460 | 1 | 20/400 | 20/40 | gas |

| 18 | B | mixed NV-fibrosis | all fibrosis | 85 | 1927 | 1 | 8/200 | 20/400 | gas |

| 19 | C | fibrosis | fibrosis | 1073 | 1903 | 1 | 20/150 | NLP | gas |

| 20 | B | fibrosis | fibrosis | 548 | 1595 | 2 | 20/150 | 20/100 | gas |

C=control; B=bevacizumab; NV=neovascularization; VA=best-corrected visual acuity; POM3=post-op month 3

- =minor bleeding stopping either spontaneously or with transient bottle elevation

- =moderate to severe bleeding requiring endodiathermy or with formation of broad sheets of clots extending from the bleeding sites

Attached=Retina attached or not at post-op month 3

Vitreous VEGF = level of vascular endothelial growth factor (pg/mL) at time of vitrectomy. 0 = undetectable with conditions applied

Vitreous CTGF = level of connective tissue growth factor (pg/mL) at time of vitrectomy. 0 = undetectable with conditions applied

All eyes underwent surgery within 7 days of randomization (median time to surgery was four days; Table 1). The majority of eyes had a predominantly fibrotic appearance to the fibrovascular proliferative membranes (FVP), indicating chronic disease (Table 2). Five eyes had an observable alteration (i.e. less vascularization and more fibrotic-appearing) in the FVP at the time of surgery when compared to pre-op; all of these patients had been randomized to the bevacizumab arm. Only one of these five eyes had severe bleeding requiring diathermy. No change in attachments of the hyaloid to the retina was observed on the day of surgery compared to pre-op. Moreover, no patient experienced a worsening of retinal detachment compared to pre-op. Two eyes (both in control arm) did not require gas or oil tamponade.

Two patients (one from each arm) were lost to follow-up, thus three month data (POM3) was not available on these patients (Table 2). Median VA at POM3 was 20/100 in the bevacizumab arm and 20/400 in the control arm (p-value=0.30). Eight eyes (88.9%) randomized to bevacizumab had the same or improved VA at POM3 compared to five (55.6%) in the control group. Median logmar change in BCVA from baseline to POM3 was −0.18 (range −2.0 to 1.0) in the treatment group and 0 (range −1.0 to 4.4) in the control group (p-value=0.15). All retinas were attached at POM3 but six eyes had decreased VA compared to baseline: two had visually significant cataract, two had worsening ischemia, one had severe NVG, and one had vitreous hemorrhage. As most of these patients were in the control arm, these factors likely contributed to worse VA compared to the bevacizumab arm. No patients reported systemic side effects.

Laboratory

Median VEGF levels in the vitreous were significantly higher in the control group (397 pg/mL, range 0–1073) compared to the treated group (undetectable with conditions applied, range 0–559; p-value=0.03) (Table 2). Median aqueous VEGF levels taken at baseline (13 pg/mL in bevacizumab group, range 0–1652, and 0 pg/mL in controls, range 0–868) and at the time of surgery were low in both groups and not statistically different between the two arms. Aqueous levels of VEGF did not correlate with those seen in the vitreous (p-value=0.19).

Levels of CTGF were detectable in the aqueous but were not significantly different between the two arms at the time of surgery. However, in the treatment group, median aqueous levels of CTGF were slightly higher at the time of surgery (1211 pg/mL, range 0–3020) compared to pre-injection (956 pg/mL, range 0–1890). Median levels of CTGF in the vitreous were 1235 pg/mL (range 0–2089) in the control arm and 980 pg/mL (range 0–1927) in those who received bevacizumab (p-value=0.38; Table 2). Median ratios of CTGF to VEGF vitreous levels were 39 in the bevacizumab group and 2.5 in the control group (Wilcoxon rank sum p-value=0.09).

Notably, with all 20 eyes combined, aqueous levels of CTGF were significantly correlated with vitreous levels (Spearman Correlation Coefficient [SCC] 0.72, p-value<0.001) (Figure 1). The SCC increased to 0.95 singling out the control group (n=10) but was not significant in the bevacizumab group alone (n=10, SCC 0.52, p-value 0.13), suggesting that VEGF inhibition does have an effect on CTGF. In addition, there was a statistically significant correlation between vitreous CTGF and VEGF levels that was observed in the bevacizumab group (SCC 0.75, p-value=0.01) and not the control group (SCC −0.31, p-value=0.38).

Figure 1.

Aqueous levels of CTGF are highly correlated with vitreous levels of CTGF

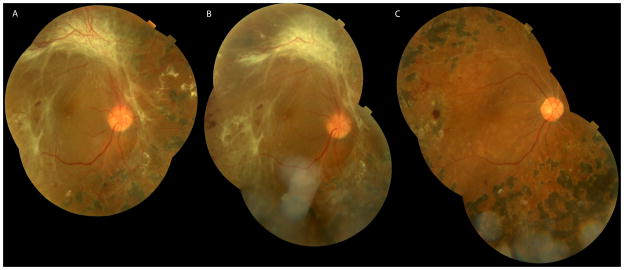

Case study patient #12

This 38 year old African-American gentleman with type 1 DM for 21 years previously had TRD repair of the left eye at an outside hospital. Visual acuity was 1/200 in the right eye and light perception in the left eye. The right eye had early cataract and a macula-off TRD/RRD (Figure 2A) with mixed neovascular-fibrotic FVP. The hyaloid was completely attached. He was randomized to the bevacizumab group. At surgery, decreased vascularization of the FVP was noted (Figure 2B). Pre-injection aqueous VEGF was 124 pg/mL and 34 pg/mL at surgery. Undiluted vitreous VEGF level was undetectable. Pre-injection aqueous CTGF was 452 pg/mL and 858 pg/mL at surgery. Vitreous CTGF level was 993 pg/mL. Vitrectomy, scleral buckle, and 14% C3F3 gas was performed. Three months after surgery visual acuity was 20/40-2 and the retina was attached (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Case 12, 38 year old monocular male presenting with visual acuity of 1/200 in the right eye due to a mac off TRD/RRD with mixed neovascular-fibrotic epiretinal proliferative membranes (A). On the day of surgery, four days after injection of intravitreal bevacizumab 1.25 mg, the neovascularization prominent along the superior arcade has regressed (B). 3 months after PPV the retina was attached with a visual acuity of 20/40 (C).

Discussion

In this randomized, controlled, reverse translational study of patients with TRD due to PDR, a clinically observable alteration in fibrovascular epiretinal membranes was noted and vitreous VEGF levels were suppressed after a single 1.25 mg intravitreal bevacizumab injection, given a median of 4 days prior to vitrectomy. Vitreous CTGF levels in the treated arm were lower but not significantly different between the controls and treated at time of vitrectomy; however several pieces of evidence suggest that VEGF inhibition does have an effect on CTGF in these eyes. First, there was a correlation between VEGF and CTGF levels that was statistically significant only in the bevacizumab group. Second, aqueous CTGF was highly correlated with vitreous CTGF levels only in the control group.

Effect of VEGF inhibition on angiofibrotic growth factors

Suppression of vitreous VEGF levels after intravitreal bevacizumab has been demonstrated previously.19–21 Similarly, we found that vitreous levels of VEGF were significantly lower in those treated with bevacizumab compared to controls. Unlike previous reports,22–25 a significant change was not seen in the aqueous of the treated group. As most of these uninsured, predominantly Hispanic patients at Los Angeles County Hospital had severe, predominantly fibrotic TRDs with no obscuring vitreous hemorrhage, these study eyes may represent a unique situation where VEGF levels have ‘burned out;’ thus, the concentration of VEGF is highest in the vitreous—closest to where it is produced. This could explain the relatively low levels of aqueous VEGF in patients at baseline (i.e. prior to injection) but relatively high levels in the vitreous at time of surgery.

There is evidence that CTGF plays an important pro-fibrogenic role in the body and eye and is induced in wound healing.26 It is upregulated by—and promotes—the fibrotic response induced by TGF-β.7,10,27 Dysregulation of CTGF expression has been implicated in abnormal fibroproliferative disease states of kidney, heart, liver, and skin diseases.28–31 Elevated levels of CTGF have been associated with proliferative vitreoretinopathy, choroidal neovascular membranes, and PDR.8,9,11,12,15,16,32

The precise relationship between VEGF and CTGF is unclear, but VEGF has been demonstrated to increase expression of CTGF.33,34 On the other hand, CTGF can also bind VEGF35 and thereby downregulate VEGF-induced angiogenesis. As CTGF levels are elevated in eyes with PDR,9,12,13,15,16,32 this may explain in part why eyes with predominantly dense fibrotic membranes do not tend to continue to develop epiretinal neovascularization.

The lack of a significant difference between vitreous CTGF levels in the control group and in those treated with bevacizumab could be explained by several reasons. One likely explanation is the number of eyes studied may be too small to detect a significant difference. Second, considering that VEGF can upregulate CTGF,33,34 decreased VEGF may downregulate CTGF, especially in the early phases of VEGF suppression. Lastly, it may be that vitreous samples were extracted too early to detect a significant alteration in CTGF. It is important to note that this study was designed to limit the potential for TRD progression observed by Arevalo and others that occurred a mean of 13 days after intravitreal bevacizumab.14 Thus, all patients underwent surgery within seven days. Since TRD progression is thought to occur by further contraction of fibrotic membranes, it may take more than 7 days for the downstream effects of contraction to occur.

Correlation of aqueous to vitreous concentrations of VEGF and CTGF

While there have been several studies analyzing vitreous19–21 and aqueous22–25 levels of VEGF independently, to date there has been no studies correlating aqueous to vitreous measurements of VEGF (or CTGF) after bevacizumab in patients with PDR. Aqueous VEGF did not correlate well with vitreous VEGF levels, probably due to the advanced stage of eyes studied in this trial. Low aqueous levels of VEGF were expected as most of these eyes did not have active neovascularization.36,37 The lack of correlation between aqueous and vitreous VEGF in severe PDR has not been previously demonstrated, and this merits further study.

On the other hand, aqueous CTGF is a good marker for vitreous CTGF in eyes not treated with VEGF inhibition. That this effect was not seen in the bevacizumab-treated group suggests that the reduction of VEGF has an effect on CTGF that was not borne out in the primary comparison of CTGF levels between the treated and controls. This effect may be better elucidated in subsequent analysis of membranes extracted from these eyes. As VEGF inhibition does appear to have some effect on CTGF, aqueous CTGF may not be substituted for vitreous CTGF in eyes treated within 7 days with bevacizumab. This may be useful in future studies when undiluted vitreous is not possible but the patient can undergo the less invasive aqueous paracentesis in the clinic.

Clinical response of TRD in PDR to VEGF inhibition

Regression of neovascularization in PDR after intravitreal bevacizumab was first demonstrated in 2006.38,39 Since then, pre-operative bevacizumab has been touted as an adjunct to decrease intraoperative bleeding,20,40 post-operative hemorrhage,40,41 surgical times;42,43 and to improve surgical outcomes.44 The efficacy of pre-operative adjunctive bevacizumab has been debated recently, especially with regard to incidence of post-operative vitreous hemorrhage.45,46 Many studies examining the effect of pre-operative bevacizumab were retrospective; those that were prospective and controlled included patients with vitreous hemorrhage that precluded grading of the fibrovascular tissue.

As expected with these patients with advanced disease, most eyes (75%) enrolled in this study had either severe TRD or TRD/RRD. Extension of FVP to the far periphery occurred in six eyes. Due to randomization, more eyes with severe TRD or TRD/RRDs were enrolled in the bevacizumab group, which could be associated with a bias toward worse results. However, overall there were no significant differences in anatomic or visual outcomes between the two groups at 3 months post-op.

Though most patients had predominantly fibrotic membranes, all six eyes judged pre-operatively to have continued vascularization (i.e. mixed neovascularization and fibrosis) were randomized to the bevacizumab group by chance. Under masked conditions, five (83%) had an alteration in the membrane to complete fibrosis noted intra-operatively. No eyes experienced an alteration in the retina-hyaloidal interface or progression of TRD within the seven day window after intravitreal bevacizumab. Interestingly, studies involving smaller doses of intravitreal bevacizumab (as low as 0.16 mg) have demonstrated similar clinical response and suppression of VEGF levels.20,25,38

The clinical observation of transitioning from a predominantly neovascular to a fibrotic epiretinal membrane in PDR over time is well known. The growth factors responsible for this transition are unclear. While the neovascularization that regresses with bevacizumab occurs relatively rapidly (as early as three days in this study), the persistently elevated CTGF levels in the face of low VEGF levels demonstrated in this study may foster a profibrotic environment. This balance between CTGF and VEGF has been termed the angiofibrotic ‘switch.’15,16 While we expected CTGF levels to be elevated after intravitreal bevacizumab, we found that they are unchanged or possibly lower in the 3–7 days after injection. Since CTGF has a heparin binding domain47 and binds to extracellular matrix in its native state, soluble CTGF that is freely circulating in ocular fluid may degrade. This may help explain the minimal change in CTGF fluid levels after VEGF inhibition. On the other hand, it is also possible that VEGF inhibition truly decreases levels of CTGF, at least in the short term.

In a retrospective analysis, Van Geest et al found higher CTGF levels and fibrosis in eyes with PDR that had undergone pre-vitrectomy intravitreal bevacizumab. While they had a subset of patients that had surgery within one week of injection, it was unclear what the levels of CTGF were in these patients.16 As illustrated in our case example, without careful comparison of neovascularization and fibrosis from pre-injection to time of surgery (which requires relatively clear media), one might overcall an increase in fibrosis when this change represents a regression of neovascularization in an area of pre-existing fibrosis. Since our patients had CTGF levels measured within 1 week of bevacizumab injection, it is possible that this angiofibrotic ‘switch’ begins with only decreased vascularization and VEGF within the first 7 days of injection.

On-going examination of the membranes extracted from eyes in our study should provide insight into the relation between VEGF inhibition and CTGF. Additional reports will also detail anatomic and long-term outcomes of the patients in this study.

At this time, we recommend cautious use of intravitreal bevacizumab as a pre-operative adjunct for diabetic PPV that may be most useful in eyes with predominantly neovascular membranes. The finding that levels of CTGF are still relatively low in the 3–6 days after intravitreal bevacizumab provides some rationale to perform traction detachment surgery during this early post-injection period.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Eugene de Juan, Jr. Award for Innovation (EHS), University of Iowa Department of Ophthalmology, Research to Prevent Blindness, NEI Core Grant EY03040 to the Doheny Eye Institute; The Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation (DRH)

Footnotes

Financial disclosures: Genentech ad hoc Consultant (DE), FibroGen Inc. Consultant (DRH)

References

- 1.Eliott D, Lee MS, Abrams GW. Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy: Principles and Techniques of Surgical Treatment. In: Ryan SJ, editor. Retina. 4. St. Louis: Elsevier Mosby; 2006. pp. 2413–2449. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller JW, Adamis AP, Aiello LP. Vascular endothelial growth factor in ocular neovascularization and proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Metab Rev. 1997 Mar;13(1):37–50. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0895(199703)13:1<37::aid-dmr174>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aiello LP, Avery RL, Arrigg PG, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor in ocular fluid of patients with diabetic retinopathy and other retinal disorders. N Engl J Med. 1994 Dec 1;331(22):1480–1487. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199412013312203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adamis AP, Miller JW, Bernal MT, et al. Increased vascular endothelial growth factor levels in the vitreous of eyes with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994 Oct 15;118(4):445–450. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)75794-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frank RN, Amin RH, Eliott D, Puklin JE, Abrams GW. Basic fibroblast growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor are present in epiretinal and choroidal neovascular membranes. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996 Sep;122(3):393–403. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)72066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amin RH, Frank RN, Kennedy A, Eliott D, Puklin JE, Abrams GW. Vascular endothelial growth factor is present in glial cells of the retina and optic nerve of human subjects with nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997 Jan;38(1):36–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saika S, Yamanaka O, Sumioka T, et al. Fibrotic disorders in the eye: targets of gene therapy. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2008 Mar;27(2):177–196. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He S, Chen Y, Khankan R, et al. Connective tissue growth factor as a mediator of intraocular fibrosis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008 Sep;49(9):4078–4088. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuiper EJ, de Smet MD, van Meurs JC, et al. Association of connective tissue growth factor with fibrosis in vitreoretinal disorders in the human eye. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006 Oct;124(10):1457–1462. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.10.1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khankan R, Oliver N, He S, Ryan SJ, Hinton DR. Regulation of fibronectin-EDA through CTGF domain-specific interactions with TGFbeta2 and its receptor TGFbetaRII. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011 Jul;52(8):5068–5078. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-7191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hinton DR, He S, Jin ML, Barron E, Ryan SJ. Novel growth factors involved in the pathogenesis of proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Eye (Lond) 2002 Jul;16(4):422–428. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hinton DR, Spee C, He S, et al. Accumulation of NH2-terminal fragment of connective tissue growth factor in the vitreous of patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 2004 Mar;27(3):758–764. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.3.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abu El-Asrar AM, Van den Steen PE, Al-Amro SA, Missotten L, Opdenakker G, Geboes K. Expression of angiogenic and fibrogenic factors in proliferative vitreoretinal disorders. Int Ophthalmol. 2007 Feb;27(1):11–22. doi: 10.1007/s10792-007-9053-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arevalo JF, Maia M, Flynn HW, Jr, et al. Tractional retinal detachment following intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) in patients with severe proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008 Feb;92(2):213–216. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.127142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuiper EJ, Van Nieuwenhoven FA, de Smet MD, et al. The angio-fibrotic switch of VEGF and CTGF in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. PLoS One. 2008;3(7):e2675. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Geest RJ, Lesnik-Oberstein SY, Tan HS, et al. A shift in the balance of vascular endothelial growth factor and connective tissue growth factor by bevacizumab causes the angiofibrotic switch in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012 Apr;96(4):587–590. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-301005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sohn E. Bimanual vitreoretinal surgery for tractional retinal detachment due to proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Retina Today. 2011 Jul-Aug;2011:42–44. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han DP, Pulido JS, Mieler WF, Johnson MW. Vitrectomy for proliferative diabetic retinopathy with severe equatorial fibrovascular proliferation. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995 May;119(5):563–570. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70213-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arimura N, Otsuka H, Yamakiri K, et al. Vitreous mediators after intravitreal bevacizumab or triamcinolone acetonide in eyes with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmology. 2009 May;116(5):921–926. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hattori T, Shimada H, Nakashizuka H, Mizutani Y, Mori R, Yuzawa M. Dose of intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) used as preoperative adjunct therapy for proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Retina. 2010 May;30(5):761–764. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181c70168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qian J, Lu Q, Tao Y, Jiang YR. Vitreous and plasma concentrations of apelin and vascular endothelial growth factor after intravitreal bevacizumab in eyes with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Retina. 2011 Jan;31(1):161–168. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181e46ad8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sawada O, Kawamura H, Kakinoki M, Sawada T, Ohji M. Vascular endothelial growth factor in aqueous humor before and after intravitreal injection of bevacizumab in eyes with diabetic retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007 Oct;125(10):1363–1366. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.10.1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsuyama K, Ogata N, Jo N, Shima C, Matsuoka M, Matsumura M. Levels of vascular endothelial growth factor and pigment epithelium-derived factor in eyes before and after intravitreal injection of bevacizumab. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2009 May;53(3):243–248. doi: 10.1007/s10384-008-0645-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Forooghian F, Kertes PJ, Eng KT, Agron E, Chew EY. Alterations in the intraocular cytokine milieu after intravitreal bevacizumab. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010 May;51(5):2388–2392. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamaji H, Shiraga F, Shiragami C, Nomoto H, Fujita T, Fukuda K. Reduction in dose of intravitreous bevacizumab before vitrectomy for proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011 Jan;129(1):106–107. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Igarashi A, Okochi H, Bradham DM, Grotendorst GR. Regulation of connective tissue growth factor gene expression in human skin fibroblasts and during wound repair. Mol Biol Cell. 1993 Jun;4(6):637–645. doi: 10.1091/mbc.4.6.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grotendorst GR. Connective tissue growth factor: a mediator of TGF-beta action on fibroblasts. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1997 Sep;8(3):171–179. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(97)00010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leask A. Signaling in fibrosis: targeting the TGF beta, endothelin-1 and CCN2 axis in scleroderma. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2009;1:115–122. doi: 10.2741/E12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okada H, Kikuta T, Kobayashi T, et al. Connective tissue growth factor expressed in tubular epithelium plays a pivotal role in renal fibrogenesis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005 Jan;16(1):133–143. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004040339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uchio K, Graham M, Dean NM, Rosenbaum J, Desmouliere A. Down-regulation of connective tissue growth factor and type I collagen mRNA expression by connective tissue growth factor antisense oligonucleotide during experimental liver fibrosis. Wound Repair Regen. 2004 Jan-Feb;12(1):60–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1067-1927.2004.012112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lang C, Sauter M, Szalay G, et al. Connective tissue growth factor: a crucial cytokine-mediating cardiac fibrosis in ongoing enterovirus myocarditis. J Mol Med (Berl) 2008 Jan;86(1):49–60. doi: 10.1007/s00109-007-0249-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuiper EJ, Witmer AN, Klaassen I, Oliver N, Goldschmeding R, Schlingemann RO. Differential expression of connective tissue growth factor in microglia and pericytes in the human diabetic retina. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004 Aug;88(8):1082–1087. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2003.032045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suzuma K, Naruse K, Suzuma I, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor induces expression of connective tissue growth factor via KDR, Flt1, and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-akt-dependent pathways in retinal vascular cells. J Biol Chem. 2000 Dec 29;275(52):40725–40731. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006509200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang H, Huang Y, Chen X, et al. The role of CTGF in the diabetic rat retina and its relationship with VEGF and TGF-beta(2), elucidated by treatment with CTGFsiRNA. Acta Ophthalmol. 2010 Sep;88(6):652–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2009.01641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Inoki I, Shiomi T, Hashimoto G, et al. Connective tissue growth factor binds vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and inhibits VEGF-induced angiogenesis. FASEB J. 2002 Feb;16(2):219–221. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0332fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Funatsu H, Yamashita H, Noma H, et al. Aqueous humor levels of cytokines are related to vitreous levels and progression of diabetic retinopathy in diabetic patients. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2005 Jan;243(1):3–8. doi: 10.1007/s00417-004-0950-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sharma RK, Rowe-Rendleman CL. Validation of molecular and genomic biomarkers of retinal drug efficacy: use of ocular fluid sampling to evaluate VEGF. Neurochem Res. 2011 Apr;36(4):655–667. doi: 10.1007/s11064-010-0328-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Avery RL, Pearlman J, Pieramici DJ, et al. Intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) in the treatment of proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmology. 2006 Oct;113(10):1695 e1691–1615. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.05.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mason JO, 3rd, Nixon PA, White MF. Intravitreal injection of bevacizumab (Avastin) as adjunctive treatment of proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006 Oct;142(4):685–688. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.04.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ahmadieh H, Shoeibi N, Entezari M, Monshizadeh R. Intravitreal bevacizumab for prevention of early postvitrectomy hemorrhage in diabetic patients: a randomized clinical trial. Ophthalmology. 2009 Oct;116(10):1943–1948. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lo WR, Kim SJ, Aaberg TM, Sr, et al. Visual outcomes and incidence of recurrent vitreous hemorrhage after vitrectomy in diabetic eyes pretreated with bevacizumab (avastin) Retina. 2009 Jul-Aug;29(7):926–931. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181a8eb88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rizzo S, Genovesi-Ebert F, Di Bartolo E, Vento A, Miniaci S, Williams G. Injection of intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) as a preoperative adjunct before vitrectomy surgery in the treatment of severe proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008 Jun;246(6):837–842. doi: 10.1007/s00417-008-0774-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.di Lauro R, De Ruggiero P, di Lauro MT, Romano MR. Intravitreal bevacizumab for surgical treatment of severe proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2010 Jun;248(6):785–791. doi: 10.1007/s00417-010-1303-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yeoh J, Williams C, Allen P, et al. Avastin as an adjunct to vitrectomy in the management of severe proliferative diabetic retinopathy: a prospective case series. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2008 Jul;36(5):449–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ahn J, Woo SJ, Chung H, Park KH. The effect of adjunctive intravitreal bevacizumab for preventing postvitrectomy hemorrhage in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmology. 2011 Nov;118(11):2218–2226. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith JM, Steel DH. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor for prevention of postoperative vitreous cavity haemorrhage after vitrectomy for proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(5):CD008214. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008214.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brigstock DR, Steffen CL, Kim GY, Vegunta RK, Diehl JR, Harding PA. Purification and characterization of novel heparin-binding growth factors in uterine secretory fluids. Identification as heparin-regulated Mr 10,000 forms of connective tissue growth factor. J Biol Chem. 1997 Aug 8;272(32):20275–20282. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.32.20275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]