Abstract

Objective

To analyze the post-effects of a single bout of resistance exercise on cardiovascular parameters in patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD).

Design

Randomized cross-over.

Methods

Seventeen PAD patients performed two experimental sessions: control (C) and resistance exercise (R). Both sessions were identical (8 exercises, 3 × 10 reps), except that R session was performed with intensity between 5–7 in the OMNI-RES scale and the C session was performed without any load. Systolic blood pressure (BP), diastolic BP, heart rate (HR), and rate pressure product (RPP) were measured for one hour after the interventions in the laboratory, and during 24-hour using ambulatory BP monitoring.

Results

After the R session, systolic BP (greatest reduction: −6±2 mmHg, p<0.01) and RPP (greatest reduction: −888±286 mmHg*bpm; p<0.01) decreased until 50 minutes after exercise. From the second hour until 23-hour after exercise BP, HR and RPP product were similar (p>0.05) between R and C sessions. Blood pressure load, nocturnal blood pressure fall and morning surge were also similar between R and C sessions (p>0.05).

Conclusion

A single bout of resistance exercise decreased BP and cardiac work for one hour after exercise in clinical conditions, and did not modify ambulatory cardiovascular variables during 24-hours in patients with PAD.

Keywords: Peripheral Vascular Disease, Exercise, Blood Pressure, Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring

INTRODUCTION

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) refers to an occlusion of artery blood flow [1], mainly caused by an atherosclerotic process located in the lower limbs [2]. This occlusion promotes an imbalance between the oxygen demand and supply to lower limbs [3], leading to pain in the legs during effort, known as intermittent claudication. PAD affects between 3 and 10% of the general population, and more than 20% of the population above 70 years [4]. In Brazil, PAD affects 10.5% of the population over 18 years [5]. In addition, 10–35% of the PAD patients have intermittent claudication symptom [6].

Hypertension affects more than 80% of PAD patients, which partially explains the elevated rates of cardiovascular mortality observed in these patients [7–8]. A previous study observed that in PAD patients, the risk of cardiovascular mortality increases 32% for each 10mmHg increase in blood pressure (BP) [9]. Therefore, interventions aiming to decrease BP and cardiovascular risk are desirable for PAD patients [10–12].

Lifestyle modification including smoking cessation and physical activity practice has been recommended for improving walking capacity and controlling cardiovascular risk factors in PAD patients [13–17]. In addition, resistance exercise has been recommended for PAD patients because they are known to have decreased leg strength and muscle atrophy [8, 18–20]. A single bout of resistance exercise promotes an acute decrease in BP among individuals with hypertension [21–25]. This decrease ranges from 8.0 to 12.6 mmHg and from 4.6 to 9.0 mmHg for systolic and diastolic BP, respectively, and it can be maintained for up to 10 hours after exercise while subjects perform daily activities [21–25]. Therefore, this response has been considered clinically significant since it reduces BP for a prolonged period of time after exercise [24]. However, whether similar cardiovascular responses are observed in PAD patients is still unknown.

In a previous study [12], we observed that a single bout of resistance exercise (6 upper and lower limbs exercises, 3 sets of 12, 10, 8 repetitions, perceived exertion between 11 and 13 on the Borg scale) decreased systolic and diastolic BP during the recovery period in medicated and non-obese PAD patients of both genders with mean age of 64.4±6.6 years. This reduction was observed for one hour after the exercise while the patients were seated in the laboratory. However, whether this hypotensive response is maintained under daily activities has not been established yet, limiting the clinical applicability of this finding. Long-term hypotensive effects have been observed following resistance exercise in non-obese hypertensive women receiving antihypertensive drugs after performing 3 sets of 20 repetitions at 40% of 1 maximal repetition (1RM) in 6 resistance exercises for the entire body [24]. Since most of the PAD patients are hypertensive and receive anti-hypertensive therapy, it is possible that they also present a long-term reduction in BP after a single bout of resistance exercise.

Heart rate is typically increased until 90 minutes after a single bout of resistance exercise [26–28], due to a resetting of baroreceptors [26]. Although this is a physiological response, the post-exercise tachycardia may increase myocardial oxygen demand and trigger cardiac events in predisposed patients [27], which may be important in PAD patients, since coronary artery disease is highly prevalent in PAD patients [28]. However, heart rate response after exercise depends on exercise intensity [29–30], and thus after low intensity resistance exercise should have a minimal influence on heart rate and myocardial oxygen demand. Thus, the understanding of the effects of resistance exercise on rate pressure product is clinically relevant and positive effects on this variable might influence the cardiovascular risk of PAD patients. Interestingly, no previous study has analyzed the effects of a single bout of resistance exercise on 24-hour heart rate and rate pressure product in PAD patients.

The aim of this study was to analyze the post-effects of a single bout of resistance exercise on cardiovascular parameters in patients with PAD. The hypothesis was that a single bout of resistance exercise would reduce BP and increase heart rate for several hours after exercise, however, the rate pressure product would remain reduced, indicating that resistance exercise decreased myocardial oxygen demand in PAD patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Recruitment

Patients with PAD were recruited from public hospitals and private vascular clinics. Patients with PAD and symptoms of claudication were included if they: (a) had an ankle-brachial index (ABI) ≤ 0.90, (b) had a graded treadmill test limited by claudication, (c) were nonobese, (d) were not performing any regular exercise program, (e) were not using antihypertensive medications that affects heart rate responses to exercise (β-blockers and non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers), (f) systolic BP < 160 mmHg and diastolic BP < 105 mmHg; and (g) had no symptoms of myocardial ischemia during the treadmill test. Seventeen patients were deemed eligible for the study. However, only fifteen of them agreed to use the ambulatory BP monitor. This study was approved by the Joint Committee on Ethics of Human Research of the University (process 0134/09). Each patient was informed of the risks and benefits involved in the study, and signed a written informed consent before participation.

Subjects screening and preliminary testing

Before the study, patients BP was measured in both arms to determine in which arm the ambulatory BP monitor would be placed. In addition, all the patients performed a progressive cardiopulmonary treadmill test until maximal claudication pain, as previously described for these patients [31]. During the test, electrocardiogram was continuously monitored. Claudication onset time and peak walking time were defined, respectively, as the time walked until the patient first reported pain in the leg, and the time they were unable to continue exercise due to leg pain.

Familiarization to resistance exercises

Prior to the experiments, patients underwent two familiarization sessions designed to standardize resistance exercises. In each session, patients executed the following exercises: bench press, knee extension, seated row, knee curl, frontal rise and standing calf raise. In each exercise, they performed 3 sets of 10 repetitions with the minimum load allowed by the machines.

Identification of the loads used in the experimental sessions

After familiarization, subjects underwent up to four sessions to identify the load that would be used in the experimental sessions. During these sessions, the load corresponding to a rate of perceived exertion between 5 and 7 on the OMNI resistance exercise scale (OMNI-RES) [32] was determined for each exercise, as previously described [33]. The OMINI-RES has a direct relationship with the Borg scale that has been widely used to assess rate of perceived exertion [34]. Briefly, OMNI–RES was composed by 10 levels of perceived exertion defined by the subjective intensity of effort, strain, discomfort, and/or fatigue experienced during the exercise task. The levels of 5 to 7 on the OMNI scale corresponded to moderate exertion [32].

Once the workload for an exercise was determined in one session and confirmed in the next one, this exercise was not performed anymore until the experimental sessions. In scientific literature, exercise intensity is usually determined based on a % of 1RM instead of OMNI scale. Thus, to compare the correspondence between the exercise intensity established by 5 to 7 in the OMNI scale and the % of 1RM, a subset of 8 patients underwent a 1 RM test following the Clarke protocol [35] in four of the proposed exercise (bench press, knee extension, seated row, and frontal rise). In this exercises, the workloads corresponded, respectively, to 68.2, 68.7, 64.9, and 76.5 % of 1RM.

Experimental protocol

Patients underwent two experimental sessions in a random order: control (C) and resistance exercise (R). Each session initiated between 7 and 8 a.m., and an interval of 7 days was kept between them. Patients were instructed to have a light meal before the experiments, to avoid physical exercise and alcohol ingestion for at least the preceding 48 hours, and to avoid caffeine in the preceding 24 hours and smoking before experiments.

In each experimental session, patients rested in the seated position for 20 minutes (pre-intervention) in a quiet room. During this period, clinic BP and heart rate were measured in the laboratory by the same observer, who was blinded to which session the subject was going to perform. Auscultatory BP was assessed using a mercury column sphygmomanometer (Unitec, Brazil) and a stethoscope (BIC, Brazil). Phases I and V of the Korotkoff sounds were established as the systolic and diastolic BP, respectively. At each time point, BP was assessed three times, and the mean value was used for analysis. Heart rate was assessed immediately after BP measurement using a heart rate monitor (RS 800, Polar, United States). Rate pressure product was obtained multiplying systolic BP by heart rate.

Patients then performed the interventions in an exercise room. Patients were blinded to which session they were going to perform until the beginning of the intervention. In the R session, patients performed 3 sets of 10 repetitions in the 6 resistance exercises aforementioned with a workload of 5–7 in the OMNI-RES scale. Intervals of 2 min were interspersed between the sets and exercises. The C session was similar to R session, however, in this session, resistance exercises were performed without any load.

After the interventions, patients returned to a quiet room, where they remained seated for 60 minutes. BP and heart rate were obtained every 15 minutes using the same procedures of the pre-experimental period. Afterwards, an ambulatory BP monitor programmed to take measurements every 15 minutes for 24 hours (Dynamapa, Cardios, Brazil) was attached to the patients’ arm with the higher BP, and a pedometer (DigiWalker SW-700, Japan) was placed on their waist to assess cardiovascular responses and physical activity during 24-hours daily activities.

Ambulatory blood pressure variables measurements

Mean BP for 24 hour, awake and sleep periods reported by the patients were calculated. Nocturnal BP fall was calculated in absolute values (mean awake – mean asleep BP). Morning surge was defined as the difference between means of BP values obtained in the last two hours of sleeping and the first two hours after awakening.

Statistical analyses

The sample size was statistically calculated based on a previous study [12] that observed a difference in systolic BP of 14±5mmHg between C and R sessions, and considering a power of 80% and an alpha error of 5%, was calculated to be 11 subjects.

The Gaussian distribution and the homogeneity of variance of the data were analyzed by the Shapiro–Wilk and Levene tests. To analyze the changes in clinical cardiovascular variables after the interventions, the changes in variables measured at laboratory were calculated (post – pre-intervention), and a two-way ANOVA for repeated measures was employed, establishing sessions (C and R) and time (pre and post-intervention) as the main factors.

Cardiovascular variables data during daily activities were averaged in hours and compared between the sessions by a two-way ANOVA for repeated measures, establishing sessions (C and R) and hours (1 to 24) as the main factors. To compare the mean ambulatory BP values (24-hour, awake, asleep, nocturnal BP fall, and BP morning surge) a paired Student t test was used.

For all analyses, P<0.05 was accepted as statistically significant, and post-hoc comparisons were performed by Newman-Keuls test whenever necessary. Data are presented as mean ± standard error.

RESULTS

The characteristics of the PAD patients are shown in Table 1. They were mostly elderly, female and hypertensives. Their mean systolic and diastolic BP levels were 135±3 and 77±3 mmHg, respectively, and 70.6% of them were receiving anti-hypertensive medication, with 4 patients taken 2 drugs simultaneously.

Table 1.

Physical and functional characteristics of the peripheral artery disease patients included in the study (n=17)

| Values | |

|---|---|

| Male/female | 7/10 |

| Age (years) | 58.2 ± 3.7 |

| Weight (kg) | 64.1 ± 2.7 |

| Height (m) | 1.58 ± 0.02 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 25.7 ± 0.8 |

| Ankle brachial index | 0.67 ± 0.03 |

| Claudication onset time (sec) | 287 ± 32 |

| Total walking time (sec) | 766 ± 82 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 135 ± 3 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 77 ± 3 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 82 ± 3 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |

| Hypertension (%) | 80.0 |

| Diabetes (%) | 53.3 |

| Current smokers (%) | 33.3 |

| Medications | |

| Inhibitors of angiotensin-converting enzyme (n=3, %) | 17.6 |

| Angiotensin receptor antagonist (n=2, %) | 11.8 |

| Diuretics (n=2, %) | 11.8 |

| Calcium channel blocker and diuretics (n=2, %) | 11.8 |

| Angiotensin receptor antagonist and calcium channel blocker (n=2, %) | 11.8 |

| Inhibitors of angiotensin-converting enzyme and diuretic (n=1, %) | 5.9 |

| Angiotensin receptor antagonist and diuretics (n=1, %) | 5.9 |

| Non-medicated (n=4, %) | 23.5 |

Values are means ± SE

Eight patients initiated the protocol with the C session, and nine with the R session. In the R session, the loads corresponding to a rate of perceived exertion of 5–7 in OMNI-RES were 23.2±2.1 kg for bench press, 17.8±1.2 kg for knee extension, 32.9±1.9 kg for seated row, 5.9±0.7 kg for knee curl, 4.9±0.4 kg for frontal rise and 6.7±1.0 kg for standing calf raise.

Systolic BP, diastolic BP, heart rate and rate-pressure product measured before the interventions were similar between the C and R sessions (123.6±2.5 vs 128.8±2.8 mmHg, 79.5±5.2 vs 78.6±4.6 mmHg, 82.8±3.1 vs 85.4±3.8 bpm, 10203±374 vs 10922±408 mmHg.bpm, respectively, p>0.05).

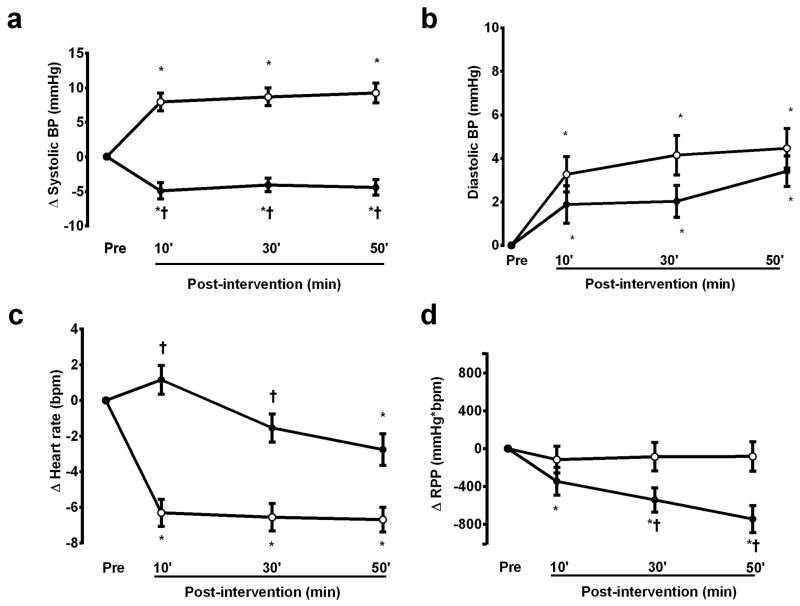

Cardiovascular responses measured in the laboratory during the first hour after the C and R sessions are presented in Figure 1. In comparison with the pre-intervention values, systolic BP increased after the C session (p<0.01) and decreased after the R session (p<0.01), while diastolic BP increased similarly after both sessions (p<0.01). Heart rate decreased after the C session throughout the recovery period (p<0.01), and decreased at 50 min of recovery after the R session (p<0.01). Thus, rate pressure product did not change after the C session (p>0.05), and decreased after the R session (p<0.01).

Figure 1.

Systolic blood pressure (BP) (A), diastolic blood pressure (B), heart rate (C) and rate pressure product (RPP) (D) measures after the control (white circle) and the resistance exercise (black circle) sessions (n=17). * significantly different from the pre-intervention value; † significantly different from the control session.

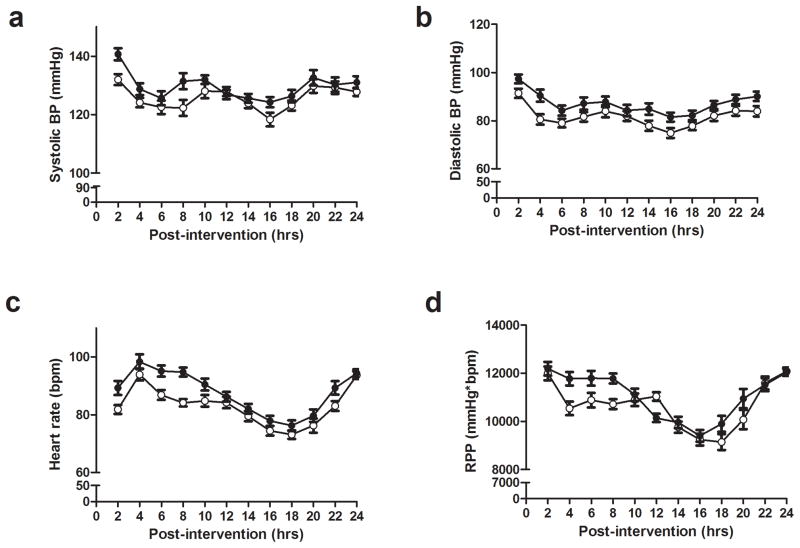

Figure 2 presents the hour-to hour cardiovascular responses after the experimental sessions. From the second hour until 23-hour after exercise BP, heart rate and rate pressure product were similar between R and C sessions (p>0.05). Awake, asleep and 24 hours systolic and diastolic BP, as well as nocturnal BP fall and morning surge after the sessions were also similar between the R and C sessions (table 2).

Figure 2.

Ambulatory systolic blood pressure (BP) (A), diastolic blood pressure (B), heart rate (C) and rate pressure product (RPP) (D) measured for 24 hours after the control (white circle) and the resistance exercise (black circle) sessions (n=15).

Table 2.

Cardiovascular variables measured after the resistance exercise (R), and the control (C) sessions (n=15) during daily activities.

| Control session | Strength session | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 hours | |||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 127.4 ± 2.4 | 126.8 ± 2.8 | 0.817 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 83.4 ± 3.0 | 83.9 ± 3.2 | 0.856 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 84.1 ± 2.9 | 85.9 ± 3.1 | 0.910 |

| Rate pressure product (mmHg*bpm) | 10722 ± 377 | 10677 ± 316 | 0.874 |

| Awake | |||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 129.6 ± 3.0 | 129.3 ± 3.2 | 0.904 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 55.0 ± 2.8 | 65.0 ± 3.1 | 0.776 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 88.5 ± 2.9 | 88.9 ± 3.7 | 0.859 |

| Rate pressure product (mmHg*bpm) | 11419 ± 392 | 11395.7 ± 337 | 0.941 |

| Asleep | |||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 123.7 ± 3.0 | 122.7 ± 3.0 | 0.640 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 78.7 ± 3.5 | 78.8 ± 3.5 | 0.541 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 75.7 ± 2.8 | 75.3 ± 3.2 | 0.887 |

| Rate pressure product (mmHg*bpm) | 9364 ± 304 | 9239 ± 320 | 0.901 |

| Nocturnal blood pressure fall | |||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | −4.1 ± 2.7 | −4.8 ± 2.3 | 0.650 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | −8.6 ± 2.6 | −9.0 ± 2.9 | 0.786 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | −14.5 ± 1.6 | −14.9 ± 2.6 | 0.814 |

| Morning surge | |||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | +3.7 ± 5.0 | +8.4 ± 3.8 | 0.454 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | +6.8 ± 3.6 | +4.2 ± 3.0 | 0.574 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | +9.2 ± 2.3 | +2.5 ± 2.1 | 0.069 |

| Number of steps performed after the experimental sessions | 6307 ± 202 | 6554 ± 209 | 0.614 |

Values are means ± SE

These similar cardiovascular responses after the interventions were not caused by the different amount of physical activity performed after the interventions (table 2), since the daily number of steps performed by the patients was also similar between the R and the C sessions (p>0.05).

DISCUSSION

The main findings of this study are that, in PAD patients: (i) a single bout of resistance exercise decreased systolic BP, increased heart rate, and decreased rate pressure product for the first hour of recovery in the laboratory; (ii) this session of resistance exercise did not alter cardiovascular variables during daily activities. Therefore, the acute cardiovascular benefits of resistance exercise in PAD patients were only short term, and were not maintained under ambulatory conditions.

In regard to the decrease in clinic BP after resistance exercise, in a previous study with PAD patients [12], we also observed a similar decrease in systolic BP during 60 min after exercise while the subjects were sitting at the laboratory. Thus, the replication of these results with a different sample and exercise protocol strengthens the post-hypotensive effects of resistance exercise in PAD patients. In previous studies, the decrease in BP after resistance exercise when the subjects were in the laboratory has been attributed to a decrease in venous return [30, 36] that leads to an increase in heart rate. In addition, the reduction on BP deactivates baroreflex, also increasing heart rate. Thus, both of these mechanisms may explain the maintenance of tachycardia in the first 30 min of recovery. Besides this increase, rate pressure product, an important marker of myocardial oxygen demand [31, 37] decreased after exercise, indicating a beneficial effect of resistance exercise while the patients were in the laboratory.

Although post-exercise hypotension was observed inside the laboratory, it was not maintained under ambulatory conditions. Previous studies have observed that the hypotensive effect of resistance exercise was maintained for several hours during daily activities in medicated hypertensives [24–25]. Melo et al. [24], analyzing the effects of a single bout of resistance exercise on BP in hypertensive women using angiotension-converting enzyme inhibitors, observed a decrease in systolic BP until 10 hours after a resistance exercise bout. Mota et al. [25] also observed a decrease in systolic BP until 7 hours after a resistance exercise bout during a workday in hypertensive subjects receiving beta-blockers or calcium antagonists associated with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor. On the other hand, a maintenance of BP after resistance exercise during daily activities was observed in hypertensive patients not receiving anti-hypertensive drug therapy [22]. These results suggest that drug therapy is important to a long-term post-exercise hypotensive effect. Considering that most of the patients with PAD were hypertensives and were under current anti-hypertensive drug therapy (table 1), we expected them to present a long hypotensive response, which did not occur.

The causes of the absence of ambulatory BP decrease after resistance exercise in PAD patients during daily activities were not assessed in this study. However, it is possible that the episodes of ischemia produced by walking throughout the monitoring period have influenced this response. Previous studies showed that PAD patients have exaggerated cardiovascular responses during walking [38–39], which have been attributed to an activation of pressor reflex caused by ischemia in lower limbs. This response might oppose the hypotensive effect of previous exercise. In addition, it is possible that daily walking activities also increased the systemic levels of inflammatory cytokines [40], which stimulates vasoconstriction, also inhibiting the ambulatory hypotension. These possible mechanisms should be directly addressed in future studies.

The effects of resistance exercise on other parameters obtained from the ambulatory BP monitoring (nocturnal blood pressure fall, mean blood pressure, and morning surge) were assessed, and none of them were significantly different between the C and the R sessions. To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe the patterns of cardiovascular responses during 24-hour after a resistance exercise session in patients with PAD, and future studies should be designed to understand the altered ambulatory pattern in these patients.

Patients with PAD present increased cardiovascular risk [7]. Previous studies have reported a tachycardia after resistance exercise in healthy and hypertensive subjects [30, 41–42], which might be related to an increase in cardiovascular risk after exercise. In the present study, heart rate and rate pressure product remained similar between C and R sessions during the ambulatory period. Considering that resistance exercise improves walking capacity [8, 43], quality of life [44] and muscle strength [8, 43] of PAD patients, the decrease in clinic and the maintenance of ambulatory myocardial oxygen demand after resistance exercise is relevant, supporting the safety of the resistance exercise for these patients.

Normotensive and hypertensive subjects were included in the study since post-exercise hypotension has been reported in both groups. We performed an additional analysis comparing the changes observed after exercise in the normotensive and hypertensive patients, and the results showed no significant differences between groups. This study included individuals with PAD from both genders, with different physical characteristics and who were taking various antihypertensive therapies, and these factors may have influenced the responses observed in this study. However, patients with PAD have different characteristics, and hypertension and the use of antihypertensive therapy are frequent in clinical practice. Thus, including this variety of patients in the present study increased the possibility of practical applicability of the results. However, future studies should investigate these responses in specific subpopulations of PAD patients.

Patients were submitted to some familiarizations sessions before the experiments, which might have produced some training effect. However, the exercise stimulus was very low during familiarization, and both control and exercise sessions were conducted after this familiarization. Thus, it is unlikely that the familiarization sessions elicited a training effect. Ambulatory BP was assessed in the arm with higher BP instead of the non-dominant arm as usual. This procedure was taken to reduce the probability of having atherosclerosis in the arm of measurement. As the same arm was used in both experimental sessions, and as ambulatory data was only accepted if more than 85% of the measures were successfully taken, it is unlikely that the arm used to measure BP influenced the study results. Finally, the duration of drug therapy before the study was not controlled in this study, thus, whether the cardiovascular responses after resistance exercise was affected for the time under drug therapy cannot be determined. However, drug therapy was not changed after study enrollment, which means that medication was kept stable by all the subjects for at least three weeks.

In conclusion, a single bout of resistance exercise decreased BP, heart rate and myocardial oxygen demand until one hour post-exercise in clinical conditions, but it did not modify ambulatory cardiovascular variables during 24-hours in patients with PAD.

Acknowledgments

This study was founded by grants of CAPES and FACEPE. We want to thank CARDIOS company for their support.

References

- 1.Norman PE, Eikelboom JW, Hankey GJ. Peripheral arterial disease: prognostic significance and prevention of atherothrombotic complications. Med J Aust. 2004;181:150–4. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2004.tb06206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meijer WT, Hoes AW, Rutgers D, Bots ML, Hofman A, Grobbee DE. Peripheral arterial disease in the elderly: The Rotterdam Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:185–92. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Munger MA, Hawkins DW. Atherothrombosis: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and prevention. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2004;44:S5–12. doi: 10.1331/154434504322904569. quiz S-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Selvin E, Erlinger TP. Prevalence of and risk factors for peripheral arterial disease in the United States: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2000. Circulation. 2004;110:738–43. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000137913.26087.F0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Makdisse M, da Pereira AC, de Brasil DP, Borges JL, Machado-Coelho GL, Krieger JE, et al. Prevalence and risk factors associated with peripheral arterial disease in the Hearts of Brazil Project. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2008;91:370–82. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2008001800008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, Bakal CW, Creager MA, Halperin JL, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): a collaborative report from the American Association for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Peripheral Arterial Disease): endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Society for Vascular Nursing; TransAtlantic Inter-Society Consensus; and Vascular Disease Foundation. Circulation. 2006;113:e463–654. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.174526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weitz JI, Byrne J, Clagett GP, Farkouh ME, Porter JM, Sackett DL, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of chronic arterial insufficiency of the lower extremities: a critical review. Circulation. 1996;94:3026–49. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.11.3026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ritti-Dias RM, Wolosker N, de Moraes Forjaz CL, Carvalho CR, Cucato GG, Leao PP, et al. Strength training increases walking tolerance in intermittent claudication patients: randomized trial. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.07.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jelnes R, Gaardsting O, Hougaard Jensen K, Baekgaard N, Tonnesen KH, Schroeder T. Fate in intermittent claudication: outcome and risk factors. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986;293:1137–40. doi: 10.1136/bmj.293.6555.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Izquierdo-Porrera AM, Gardner AW, Powell CC, Katzel LI. Effects of exercise rehabilitation on cardiovascular risk factors in older patients with peripheral arterial occlusive disease. J Vasc Surg. 2000;31:670–7. doi: 10.1067/mva.2000.104422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins EG, Langbein WE, Orebaugh C, Bammert C, Hanson K, Reda D, et al. Cardiovascular training effect associated with polestriding exercise in patients with peripheral arterial disease. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2005;20:177–85. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200505000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cucato GG, Ritti-Dias RM, Wolosker N, Santarem JM, Jacob Filho W, Forjaz CL. Post-resistance exercise hypotension in patients with intermittent claudication. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2011;66:221–6. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322011000200007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quick CR, Cotton LT. The measured effect of stopping smoking on intermittent claudication. Br J Surg. 1982;69 (Suppl):S24–6. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800691309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ericsson B, Haeger K, Lindell SE. Effect of physical training of intermittent claudication. Angiology. 1970;21:188–92. doi: 10.1177/000331977002100306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirsch AT, Treat-Jacobson D, Lando HA, Hatsukami DK. The role of tobacco cessation, antiplatelet and lipid-lowering therapies in the treatment of peripheral arterial disease. Vasc Med. 1997;2:243–51. doi: 10.1177/1358863X9700200314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schlager O, Hammer A, Giurgea A, Schuhfried O, Fialka-Moser V, Gschwandtner M, et al. Impact of exercise training on inflammation and platelet activation in patients with intermittent claudication. Swiss Med Wkly. 2012;142:w13623. doi: 10.4414/smw.2012.13623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDermott MM, Ades P, Guralnik JM, Dyer A, Ferrucci L, Liu K, et al. Treadmill exercise and resistance training in patients with peripheral arterial disease with and without intermittent claudication: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301:165–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDermott MM, Criqui MH, Greenland P, Guralnik JM, Liu K, Pearce WH, et al. Leg strength in peripheral arterial disease: associations with disease severity and lower-extremity performance. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39:523–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2003.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGuigan MR, Bronks R, Newton RU, Sharman MJ, Graham JC, Cody DV, et al. Muscle fiber characteristics in patients with peripheral arterial disease. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33:2016–21. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200112000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Askew CD, Green S, Walker PJ, Kerr GK, Green AA, Williams AD, et al. Skeletal muscle phenotype is associated with exercise tolerance in patients with peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41:802–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fisher MM. The Effect of Resistance Exercise on Recovery Blood Pressure in Normotensive and Borderline Hypertensive Women. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2001;15:210–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hardy DO, Tucker LA. The effects of a single bout of strength training on ambulatory blood pressure levels in 24 mildly hypertensive men. Am J Health Promot. 1998;13:69–72. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-13.2.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mediano MFF, Paravidino V, Simão R, Pontes FL, Polito MD. Comportamento subagudo da pressão arterial após o treinamento de força em hipertensos controlados. Revista Brasileira de Medicina do Esporte. 2005;11:337–40. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Melo CM, Alencar Filho AC, Tinucci T, Mion D, Jr, Forjaz CL. Postexercise hypotension induced by low-intensity resistance exercise in hypertensive women receiving captopril. Blood Press Monit. 2006;11:183–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mbp.0000218000.42710.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mota MR, Pardono E, Lima LC, Arsa G, Bottaro M, Campbell CS, et al. Effects of treadmill running and resistance exercises on lowering blood pressure during the daily work of hypertensive subjects. J Strength Cond Res. 2009;23:2331–8. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181bac418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kingsley JD, Panton LB, McMillan V, Figueroa A. Cardiovascular autonomic modulation after acute resistance exercise in women with fibromyalgia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90:1628–34. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Albert CM, Mittleman MA, Chae CU, Lee IM, Hennekens CH, Manson JE. Triggering of sudden death from cardiac causes by vigorous exertion. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1355–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011093431902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hirsch AT, Criqui MH, Treat-Jacobson D, Regensteiner JG, Creager MA, Olin JW, et al. Peripheral arterial disease detection, awareness, and treatment in primary care. JAMA. 2001;286:1317–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.11.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pescatello LS, Guidry MA, Blanchard BE, Kerr A, Taylor AL, Johnson AN, et al. Exercise intensity alters postexercise hypotension. J Hypertens. 2004;22:1881–8. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200410000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rezk CC, Marrache RC, Tinucci T, Mion D, Jr, Forjaz CL. Post-resistance exercise hypotension, hemodynamics, and heart rate variability: influence of exercise intensity. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2006;98:105–12. doi: 10.1007/s00421-006-0257-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gardner AW, Skinner JS, Cantwell BW, Smith LK. Progressive vs single-stage treadmill tests for evaluation of claudication. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1991;23:402–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gearhart RE, Goss FL, Lagally KM, Jakicic JM, Gallagher J, Robertson RJ. Standardized scaling procedures for rating perceived exertion during resistance exercise. J Strength Cond Res. 2001;15:320–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Noble B, Robertson R. Perceived exertion. In: Champaign I, editor. Human Kinetics. 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lagally KM, Robertson RJ. Construct validity of the OMNI resistance exercise scale. J Strength Cond Res. 2006;20:252–6. doi: 10.1519/R-17224.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clarke DH. Adaptations in strength and muscular endurance resulting from exercise. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 1973;1:73–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Teixeira L, Ritti-Dias RM, Tinucci T, Mion Junior D, Forjaz CL. Post-concurrent exercise hemodynamics and cardiac autonomic modulation. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2011;111:2069–78. doi: 10.1007/s00421-010-1811-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gobel FL, Norstrom LA, Nelson RR, Jorgensen CR, Wang Y. The rate-pressure product as an index of myocardial oxygen consumption during exercise in patients with angina pectoris. Circulation. 1978;57:549–56. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.57.3.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bakke EF, Hisdal J, Jorgensen JJ, Kroese A, Stranden E. Blood pressure in patients with intermittent claudication increases continuously during walking. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;33:20–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2006.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ritti-Dias RM, Meneses AL, Parker DE, Montgomery PS, Khurana A, Gardner AW. Cardiovascular responses to walking in patients with peripheral artery disease. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011 doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31821ecf61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Palmer-Kazen U, Religa P, Wahlberg E. Exercise in patients with intermittent claudication elicits signs of inflammation and angiogenesis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;38:689–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heffernan KS, Kelly EE, Collier SR, Fernhall B. Cardiac autonomic modulation during recovery from acute endurance versus resistance exercise. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2006;13:80–6. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000197470.74070.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lima AH, Forjaz CL, Silva GQ, Meneses AL, Silva AJ, Ritti-Dias RM. Acute effect of resistance exercise intensity in cardiac autonomic modulation after exercise. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2011;96:498–503. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2011005000043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McGuigan MR, Bronks R, Newton RU, Sharman MJ, Graham JC, Cody DV, et al. Resistance training in patients with peripheral arterial disease: effects on myosin isoforms, fiber type distribution, and capillary supply to skeletal muscle. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:B302–10. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.7.b302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Regensteiner JG, Steiner JF, Hiatt WR. Exercise training improves functional status in patients with peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg. 1996;23:104–15. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(05)80040-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]