Abstract

Background

Lifelong exercise training maintains a youthful compliance of the left ventricle (LV), whereas a year of exercise training started later in life fails to reverse LV stiffening, possibly because of accumulation of irreversible advanced glycation end products. Alagebrium breaks advanced glycation end product crosslinks and improves LV stiffness in aged animals. However, it is unclear whether a strategy of exercise combined with alagebrium would improve LV stiffness in sedentary older humans.

Methods and Results

Sixty-two healthy subjects were randomized into 4 groups: sedentary+placebo; sedentary+alagebrium (200 mg/d); exercise+placebo; and exercise+alagebrium. Subjects underwent right heart catheterization to define LV pressure–volume curves; secondary functional outcomes included cardiopulmonary exercise testing and arterial compliance. A total of 57 of 62 subjects (67±6 years; 37 f/20 m) completed 1 year of intervention followed by repeat measurements. Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure and LV end-diastolic volume were measured at baseline, during decreased and increased cardiac filling. LV stiffness was assessed by the slope of LV pressure–volume curve. After intervention, LV mass and end-diastolic volume increased and exercise capacity improved (by ≈8%) only in the exercise groups. Neither LV mass nor exercise capacity was affected by alagebrium. Exercise training had little impact on LV stiffness (training×time effect, P=0.46), whereas alagebrium showed a modest improvement in LV stiffness compared with placebo (medication×time effect, P=0.04).

Conclusions

Alagebrium had no effect on hemodynamics, LV geometry, or exercise capacity in healthy, previously sedentary seniors. However, it did show a modestly favorable effect on age-associated LV stiffening.

Keywords: aging, alagebrium, cardiac function tests, hemodynamics

Aging is associated with stiffening of the cardiovascular system.1 For example, in healthy sedentary humans, aging leads to left ventricular (LV) stiffening and atrophy, which may contribute to the substrate for syndromes such as heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.2,3 Lifelong intensive endurance exercise training prevents these age-associated changes in LV morphology and stiffness.4 However, these benefits were not observed when exercise training was started later in life,5 suggesting the need for an adjunctive therapy to improve LV stiffness in previously sedentary older individuals.

Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) are stable nonenzymatic crosslinks between glucose and amino groups.6 AGEs accumulate slowly on long-lived proteins such as collagen and elastin in the arterial wall and ventricles, contributing to arterial and ventricular stiffening with sedentary aging and diabetes mellitus.7–9 AGEs may also increase oxidative stress and inflammation, leading to endothelial dysfunction and modification of the extracellular matrix.10,11

A thiazolium derivative, alagebrium, breaks AGE crosslinks and prevents accumulation of collagen and AGEs in the LV,12 resulting in improved LV stiffness and LV-arterial coupling in animals.9,13 In humans, less dramatic effects of alagebrium on LV function have been reported. For example, relatively short duration alagebrium use had little effect on LV size and estimated LV filling pressure in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction,14 as well as on Doppler-derived LV early diastolic function in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.15 These findings suggest that short-term use of alagebrium alone might not be sufficient to alter LV diastolic function in hearts with decades of accumulation of AGEs. However, there has been no study that invasively evaluated the effect of alagebrium on LV stiffness in healthy aged individuals. Moreover, it is unclear whether a concurrent pharmacological therapy is required to observe an exercise effect in LV stiffness when significant AGE accumulation and AGE crosslinks are likely to have occurred.

Thus, we hypothesized that a combination of alagebrium and exercise training for 1 year would be the optimal strategy to reverse age-associated LV stiffening and atrophy compared with alagebrium or exercise alone in healthy older individuals. To investigate this hypothesis, we performed comprehensive and detailed measurements of hemodynamics and LV structure and function in healthy older individuals before and after 1 year of alagebrium combined with exercise training.

Methods

Subject Population and Study Design

This study was a prospective, controlled, randomized (for all subjects), double-blind placebo (alagebrium only) study for 1 year evaluating the efficacy of the combination of alagebrium or placebo (200 mg daily) and aerobic exercise training or contact control in healthy older individuals (≥60 years). Sixty-two healthy sedentary adults (40 women, 22 men; 67.1±6 years) were recruited from the Dallas Heart Study,16 the Cooper Center Longitudinal Study,17 and a random sample of all employees of Texas Health Resources.2 Subjects were randomly assigned to 4 groups: (1) sedentary+placebo (controls); (2) sedentary+alagebrium (alagebrium alone); (3) a year of aerobic exercise at moderate intensity+placebo (exercise alone); and (4) exercise training and alagebrium (exercise and alagebrium). Subjects who were randomized into the sedentary group underwent nonaerobic yoga or balance training as contact control for the year period. Subjects were excluded if they were exercising for >30 minutes 3 times/wk. All subjects were rigorously screened for comorbidities, including obesity, lung disease, diabetes mellitus, hypertension (24-hour blood pressure [BP] >140/90 mm Hg or on medical treatment for hypertension), coronary artery disease, or structural heart disease at baseline and postexercise transthoracic echocardiograms.2,4 All subjects signed an informed consent form approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas and Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas. All procedures conformed to the standards set by the Declaration of Helsinki.

Exercise Testing

All the subjects performed maximal exercise testing to measure maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max) as previously reported.2,4,5 A modified Astrand–Saltin incremental treadmill protocol was used. Measures of ventilatory gas exchange were made by use of the Douglas bag technique. Gas fractions were analyzed by mass spectrometry (Marquette MGA 1100) and ventilatory volumes were measured with a Tissot spirometer. The heart rate at the ventilatory threshold was defined as the heart rate at maximal steady state, which was generally equivalent to ≈80% to 85% of the maximal heart rate. Exercise testing was repeated at the end of the sixth month and after 1 year of the intervention.

Exercise Training Program

Subjects who were randomized into the exercise group participated in a 1-year training program with the goal of increasing duration and intensity. Initially, the subjects walked or jogged, 3 times/wk for 25 min/session, at the base pace, which targets heart rates equivalent to ≈70% to 80% of maximal heart rate. From the third month, base pace was gradually prolonged to 35 min/session. At the fourth month, 30 min/session of higher intensity maximal steady state was added monthly and the frequency of maximal steady state was increased to twice/mo from the fifth month. From the 6th to 12th month, subjects exercised 4 sessions/wk (3 base pace for 35–40 minutes and 1 maximal steady state for 40 minutes). The sedentary group underwent yoga or balance training 3 to 4 times/wk to control for the increased contact associated with monitoring the exercise training sessions.18

Cardiac MRI

Cardiac MRI images were obtained using a 1.5-tesla Philips NT scanner.19 LV mass and volumes were measured using QMass software (Medis, The Netherlands) as previously reported.4 LV mass was computed as the difference between epicardial and endocardial areas multiplied by the density of heart muscle, 1.05 g/mL.20 Papillary muscle mass was regarded as a fraction of LV mass.

Echocardiography

LV images were obtained by 3-dimensional echocardiography (iE33; Philips Medical System) at all loading conditions during the invasive study. LV end-diastolic volume (LVEDV) was analyzed offline with Qlab software (3DQA; Philips). Consistent with a previous report from our laboratory,21 LVEDV resulted in a good correlation with MRI values in this study, with a typical error expressed as a coefficient of variation of 10% (95% confidence interval, 8–12).

Experimental Protocol

Right heart catheterizations were performed before and after exercise training. A 6-Fr Swan-Ganz catheter was placed to measure pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) and right atrial pressure during end expiration. After the baseline measurements, lower-body negative pressure was used to decrease cardiac filling.4,5,22 Measurements including heart rate, PCWP, BP, LVEDV, and cardiac output (and therefore stroke volume) by acetylene rebreathing23 were performed after 5 minutes each of −15 and −30 mm Hg lower-body negative pressure. The lower-body negative pressure was then released. After repeat measurements confirmed a return to a steady state, cardiac filling was increased by rapid infusion (≈200 mL/min) of isotonic saline. Measurements were repeated after 10 to 15 and 20 to 30 mL/kg of saline infusion. Total arterial compliance was determined by the ratio of stroke volume and pulse pressure to evaluate central aortic function.24 Effective arterial elastance was defined as brachial systolic BP×0.9 divided by stroke volume.25,26

Assessment of Cardiac Catheterization Data

To evaluate LV stiffness, LV pressure–volume curves were constructed by relating LVEDV and PCWP.4,5,21 To characterize LV pressure–volume curves, we modeled the data obtained at baseline and during cardiac unloading and loading according to an exponential equation27: P=P∞(expa(V-V0)−1), where P is PCWP, P∞ is pressure asymptote of the curve, V is LVEDV, and V0 is the equilibrium volume at which P is assumed to be 0 mm Hg. For the purposes of this study, we characterized and explicitly define 4 different but related mechanical properties of the heart during diastole: (1) LV chamber stiffness, from here on called LV stiffness, was assessed from the LV stiffness constant “a” that describes the shape of the exponential pressure–volume curve, and which comprises the functional stiffness of the entire LV chamber within the range of preload studied; (2) as LV volume and pressure are influenced by external constraints,28 LV transmural filling pressure (TMP) was calculated as PCWP−right atrial pressure29 and used to construct LV TMP–volume curves to evaluate myocardial stiffness4,5,21; (3) Operating stiffness, reflecting the functional stiffness of the LV chamber at the baseline, supine, LVEDV was assessed by the changes in PCWP relative to those in LVEDV during cardiac unloading and loading3; (4) LV distensibility was defined as the absolute value of LVEDV for any given distending pressure (PCWP) independent of LV stiffness,3 independent of the overall shape of the p/v curve.

The PCWP and stroke volume were used to construct Starling (stroke volume index/PCWP) curves. LV stroke work was calculated as (mean BP−PCWP)×stroke volume. LVEDV/stroke work relationships were constructed, and the slopes of the relationship were used to assess LV systolic function.30

Assessment of Overall Cardiovascular Function

The primary outcome in the present study was a change in LV stiffness assessed by the LV stiffness constant derived from the pressure–volume curves, which reflects LV static diastolic function. Secondary outcomes included (1) functional responses during exercise as assessed by VO2max; (2) LV morphology by cardiac MRI to document the cardiac adaptation to the exercise training; (3) global LV performance assessed from Starling curves and preload-recruitable stroke work; (4) myocardial stiffness assessed from LV TMP–volume curves; (5) operating stiffness; (6) LV distensibility; and (7) global arterial function and ventricular-arterial coupling.

Sample Size Calculation

Sample size was estimated (α=0.05; β<0.20) based on previous data in aged animals,9 suggesting that alagebrium may improve LV stiffness by as much as 24 U, with a SD of 13. Thus, assuming the effect was equivalently potent in humans in an unpaired comparison, this effect could be detected with 13 subjects per group. Extrapolating this difference to humans, we expected that the same effect could be detected with 13 subjects per group. With an expected drop-out of 2 subjects in each group for 1 year, we planned to enroll 15 subjects per group.

Statistical Analysis

Measurements of LV volume by cardiac MRI and echocardiography and VO2max were performed by investigators blinded to the group assignment (alagebrium or placebo). After all the measurements and data analyses were completed, drug codes were broken and made available for statistical analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (Cary, NC). Continuous data were expressed as mean±SD except for graphics, in which SEM was used. Baseline data in 4 groups before intervention were compared using a 1-way ANOVA with post hoc analysis or nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test, depending on the outcome of tests for normality. A linear mixed model was used as the primary statistical analysis tool. Based on our study design, the main effects of alagebrium (medication×time) or exercise training (training×time) for 1 year were first assessed, followed by an interaction effect of alagebrium and training (medication×training×time) as the primary analysis. As a secondary analysis, differences in least square means were used for prepost multiple comparisons where either the main time effect of alagebrium or training or an interaction containing time achieved a P value <0.05. For pressure–volume curves, a multivariate regression analysis was conducted on the repeated measures data, modeling pressure by use of the covariates volume and subject group. A 2-way repeated measures ANOVA was used to evaluate the effects of intervention on variables at multiple loading conditions. A P value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Subject Characteristics

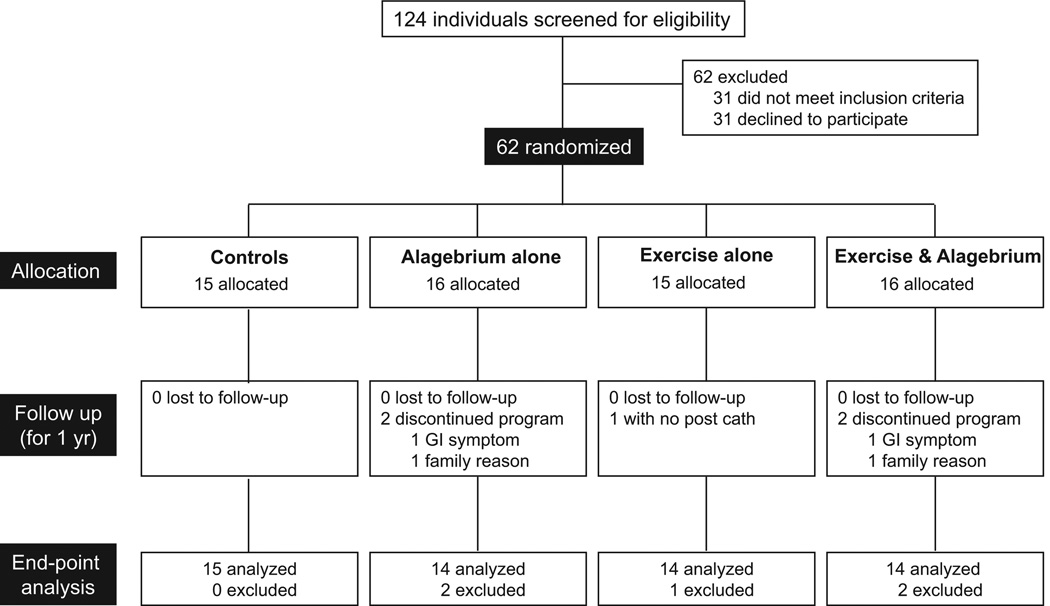

As shown in Figure 1, 58 subjects of 62 (94%) completed a year of intervention. One subject in the exercise alone group had no catheterization after intervention for technical reasons. Thus, hemodynamic data were analyzed in the remaining 57 subjects. There were no differences in clinical variables, including age, sex, heart rate, supine systolic BP, or VO2max among the 4 groups before intervention (Table 1). Resting heart rate tended to decrease in the exercise groups after 1 year of intervention (training×time, P=0.06). Body weight was unaffected by the intervention in both exercise and nonexercise groups (training×time, P=0.34 and training×medication×time, P=0.18). The 1 year of intervention had little impact on systolic BP, pulse pressure, cardiac index, or HbA1c (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Enrollment, randomization, and retention of the study participants. Exercise & Alagebrium indicates subjects in this group had exercise training and alagebrium (200 mg/d) during the 1-year intervention. GI indicates gastrointestinal.

Table 1.

Baseline Subject Characteristics

| Controls | Alagebrium Alone | Exercise Alone | Exercise & Alagebrium | ANOVA P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (female, %) | 15 (67) | 14 (64) | 14 (71) | 14 (57) | 0.88 |

| Age (range), y | 69 (60–88) | 65 (61–72) | 65 (62–80) | 67 (60–80) | 0.12* |

| Height, cm | 166 (154–184) | 167 (157–184) | 165 (157–182) | 168 (156–188) | 0.60* |

| Body weight, kg | 67±13 | 74±10 | 73±11 | 73±11 | 0.39 |

| Body surface area, m2 | 1.76±0.21 | 1.86±0.16 | 1.84±0.18 | 1.86±0.19 | 0.45 |

| Heart rate, beat/min | 65±9 | 63±7 | 65±9 | 61±7 | 0.52 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 122±13 | 117±10 | 118±11 | 114±11 | 0.34 |

| VO max, mL·kg−1·min−1 | 21.5±4.5 | 24.7±4.5 | 23.0±4.7 | 24.1±5.0 | 0.34 |

Values are mean±SD. VO2max indicates maximal oxygen uptake during at maximal exercise test.

Nonparametric analyses were used and median values were shown.

Table 2.

Resting Hemodynamics

| Controls | Alagebrium Alone | Exercise Alone | Exercise & Alagebrium |

Training× Time |

Medication× Time |

Training×Medication × Time |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate, beats/min | |||||||

| Pre | 65±9 | 63±7 | 65±9 | 61±7 | 0.06 | 0.37 | 0.78 |

| Post | 64±9 | 63±8 | 62±8 | 59±8 | |||

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | |||||||

| Pre | 122±14 | 117±10 | 118±11 | 114±11 | 0.60 | 0.07 | 0.38 |

| Post | 120±11 | 118±15 | 115±11 | 118±15 | |||

| Pulse pressure, mm Hg | |||||||

| Pre | 51±12 | 44±9 | 48±8 | 46±9 | 0.73 | 0.23 | 0.72 |

| Post | 51±13 | 47±16 | 46±10 | 48±15 | |||

| Cardiac index (reb), L·m−2 | |||||||

| Pre | 2.72±0.42 | 2.56±0.24 | 2.77±0.52 | 2.68±0.46 | 0.41 | 0.68 | 0.76 |

| Post | 2.72±0.47 | 2.58±0.21 | 2.64±0.41 | 2.65±0.30 | |||

| SV index (reb), mL·m−2 | |||||||

| Pre | 43.0±10.6 | 41.5±7.1 | 42.6±6.1 | 43.6±5.7 | 0.61 | 0.76 | 0.94 |

| Post | 42.7±7.6 | 41.9±7.4 | 43.4±8.0 | 45.3±7.0 | |||

| VO2max, mL·kg−1·min−1 | |||||||

| Pre | 21.5±4.5 | 24.7±4.5 | 23.0±4.7 | 24.1±5.0 | <0.001 | 0.82 | 0.41 |

| Post | 21.2±4.5 | 24.1±4.6 | 24.8±5.7* | 26.3±6.0* | |||

| PCWP, mm Hg | |||||||

| Pre | 11.2±2.2 | 10.9±2.0 | 11.7±1.9 | 10.4±2.6 | 0.60 | 0.07 | 0.70 |

| Post | 10.3±2.2 | 11.2±1.6 | 11.3±2.7 | 10.7±2.5 | |||

| RAP, mm Hg | |||||||

| Pre | 7.4±2.1 | 7.7±1.8 | 8.3±1.9 | 7.2±2.0 | 0.67 | 0.19 | 0.36 |

| Post | 7.1±2.1 | 8.3±1.5 | 8.6±1.9 | 7.7±2.2 | |||

| TMP, mm Hg | |||||||

| Pre | 3.8±1.1 | 3.2±1.4 | 3.4±1.0 | 3.2±1.1 | 0.84 | 0.37 | 0.64 |

| Post | 3.2±1.0 | 2.8±1.3 | 2.7±1.2 | 3.1±1.0 | |||

| HbA1c, % | |||||||

| Pre | 5.4±0.3 | 5.6±0.2 | 5.5±0.3 | 5.4±0.3 | 0.17 | 0.73 | 0.28 |

| Post | 5.7±0.2 | 5.7±0.2 | 5.6±0.3 | 5.6±0.3 |

Values are mean±SD. Medication×time indicates individual effect of alagebrium; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; RAP, right atrial pressure; reb, acetylene rebreathing technique; SV, stroke volume; TMP, left ventricular transmural pressure; training×medication×time, the interaction effects between exercise training and alagebrium; training×time, individual effect of exercise training; and VO2max, maximal oxygen uptake during at maximal exercise test.

P<0.01 vs before training.

Tolerability and Safety

Two subjects on alagebrium had gastrointestinal symptoms and dropped out at the third and sixth months. No other adverse events were observed in the alagebrium groups.

Effects of Exercise Training and Alagebrium on Exercise Capacity

By the end of a year of training, subjects in the 2 exercise groups achieved a similar duration of training (≈150 min/wk; P=0.91). As shown in Table 2, exercise training increased VO2max (training×time, P<0.001) by 8% to 9% (exercise alone: 23.0±4.7 versus 24.8±5.7 mL/kg per minute, P<0.001; exercise and alagebrium: 24.1±5.0 versus 26.3±6.0 mL/kg per minute, P<0.001). Conversely, no change in VO2max was observed in controls (P=0.46) or alagebrium alone (P=0.19). Compliance for alagebrium was >90% (pill counts), and all the subjects participated in >85% of training sessions.

Cardiac Size and Vascular Function

As shown in Table 3, exercise training increased LV mass index (training×time, P=0.02) and LVEDV index (training×time, P=0.04), with no changes in mass–volume ratio. Alagebrium did not affect LVEDV or mass assessed by cardiac MRI (medication×time, P≥0.13). Neither total arterial compliance nor effective arterial elastance was improved by alagebrium or exercise training after 1 year of intervention.

Table 3.

Ventricular and Vascular Function

| Controls | Alagebrium Alone | Exercise Alone | Exercise & Alagebrium |

Training× Time |

Medication× Time |

Training×Medication× Time |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ventricular function | |||||||

| LVEDV index (MRI), mL·m−2 | |||||||

| Pre | 56.9±10.1 | 60.4±13.2 | 58.4±11.2 | 61.8±9.3 | 0.04 | 0.23 | 0.65 |

| Post | 55.6±10.0 | 57.9±11.0 | 60.8±12.5 | 61.7±9.9 | |||

| LVESV index (MRI), mL·m−2 | |||||||

| Pre | 18.3±3.5 | 20.4±6.5 | 18.3±5.6 | 21.0±5.5 | 0.62 | 0.08 | 0.31 |

| Post | 19.0±4.9 | 20.6±5.1 | 20.1±6.3 | 20.8±6.0 | |||

| LVEF (MRI), % | |||||||

| Pre | 68±4 | 68±6 | 69±4 | 66±5 | 0.12 | 0.83 | 0.16 |

| Post | 66±6 | 65±3 | 67±5 | 66±5 | |||

| LV mass index (MRI), g·m−2 | |||||||

| Pre | 47.9±7.2 | 50.4±6.5 | 48.7±9.8 | 50.6±9.9 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.94 |

| Post | 46.8±6.2 | 50.3±6.4 | 49.2±10.1 | 52.1±10.4* | |||

| Mass–volume ratio, g·mL−1 | |||||||

| Pre | 0.85±0.09 | 0.86±0.14 | 0.84±0.13 | 0.82±0.12 | 0.63 | 0.10 | 0.41 |

| Post | 0.85±0.12 | 0.88±0.10 | 0.82±0.13 | 0.85±0.12 | |||

| LVEDV index (echo), mL·m−2 | |||||||

| Pre | 42.9±5.5 | 42.8±8.4 | 45.2±9.4 | 44.9±7.1 | 0.04 | 0.80 | 0.56 |

| Post | 42.5±5.6 | 42.6±7.9 | 46.8±10.7 | 45.8±7.0 | |||

| LV stiffness constant | |||||||

| Pre | 0.114±0.059 | 0.122±0.057 | 0.103±0.043 | 0.127±0.071 | 0.46 | 0.04 | 0.86 |

| Post | 0.128±0.053 | 0.105±0.045 | 0.104±0.056 | 0.102±0.031 | |||

| V0, mL·m−2 | |||||||

| Pre | 17.9±5.5 | 18.0±10.1 | 21.9±10.5 | 23.7±9.4 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.98 |

| Post | 19.5±8.4 | 16.5±11.3 | 26.7±11.6* | 25.2±4.6 | |||

| Pressure asymptote, mm Hg | |||||||

| Pre | 1.7±1.7 | 1.7±1.9 | 2.6±2.2 | 1.7±2.1 | 0.15 | 0.68 | 0.50 |

| Post | 1.4±1.9 | 1.7±1.6 | 4.1±4.6 | 2.3±2.3 | |||

| Operating stiffness during unloading, mm Hg·mL−1·m2 | |||||||

| Pre | 0.6±0.2 | 0.7±0.2 | 0.7±0.3 | 0.6±0.3 | 0.37 | 0.43 | 0.37 |

| Post | 0.6±0.4 | 0.7±0.3 | 0.7±0.3 | 0.7±0.4 | |||

| Operating stiffness during loading, mm Hg·mL−1·m2 | |||||||

| Pre | 2.1±1.3 | 2.1±0.7 | 2.2±1.0 | 2.4±1.4 | 0.23 | 0.11 | 0.13 |

| Post | 2.4±1.1 | 2.4±1.4 | 2.7±1.8 | 1.7±0.4 | |||

| LV stiffness constant (TMP) | |||||||

| Pre | 0.072±0.026 | 0.084±0.040 | 0.069±0.021 | 0.098±0.059 | 0.68 | 0.08 | 0.50 |

| Post | 0079±0.044 | 0.077±0.040 | 0.089±0.044 | 0.087±0.036 | |||

| V0 (TMP), mL·m−2 | |||||||

| Pre | 20.7±7.3 | 25.6±9.3 | 21.5±15.0 | 28.6±9.1 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.44 |

| Post | 22.7±8.3 | 24.1±8.7 | 27.8±16.1 | 26.8±7.3 | |||

| Vascular function | |||||||

| TAC index, mL·mm Hg−1·m2 | |||||||

| Pre | 2.9±1.4 | 3.4±1.4 | 3.2±1.2 | 3.4±0.8 | 0.57 | 0.79 | 0.74 |

| Post | 2.9±1.7 | 3.4±1.5 | 3.3±1.2 | 3.5±1.5 | |||

| Ea index, mm Hg·mL−1·m2 | |||||||

| Pre | 2.7±0.7 | 2.6±0.5 | 2.5±0.5 | 2.4±0.3 | 0.72 | 0.35 | 0.75 |

| Post | 2.6±0.6 | 2.6±0.6 | 2.5±0.6 | 2.4±0.5 |

Ea indicates effective arterial elastance; EDV (echo), end-diastolic volume by 3-dimensional echocardiography; ESV, end-systolic volume; LVEDV (MRI), left ventricular end-diastolic volume by cardiac MRI; LVEF, LV ejection fraction; TAC, total arterial compliance; TMP, LV transmural pressure, and V0, equilibrium volume.

P<0.05 vs before training.

Catheterization Data

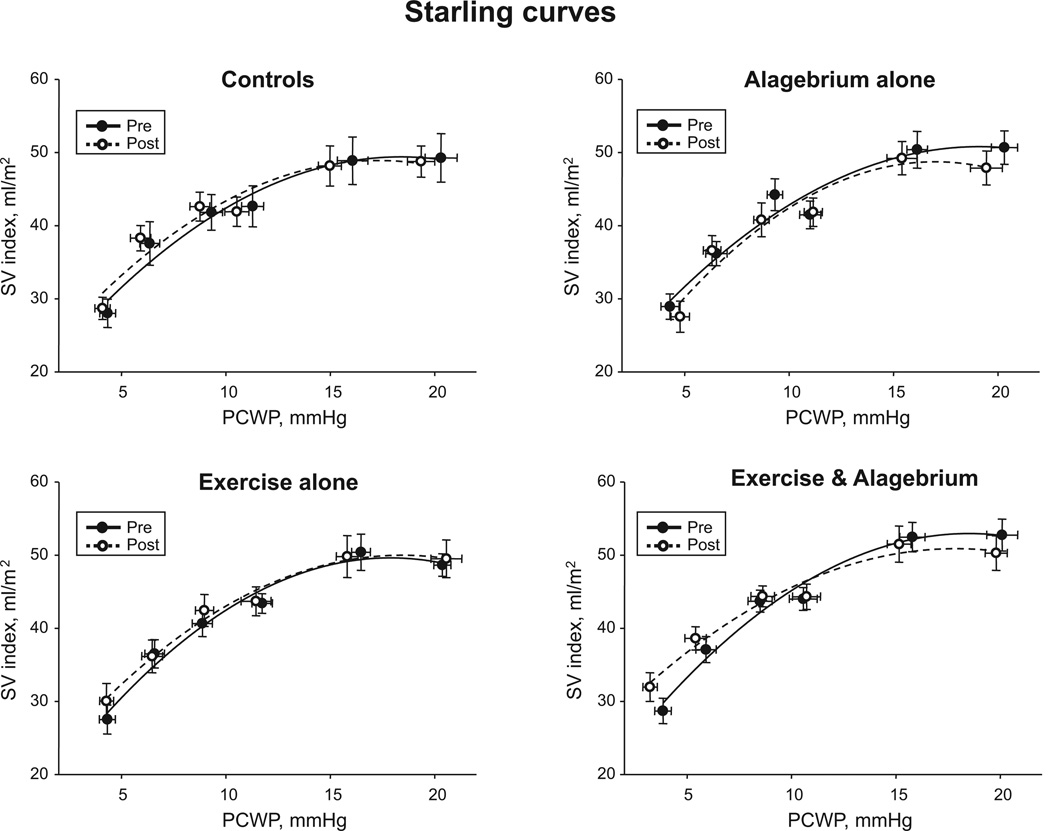

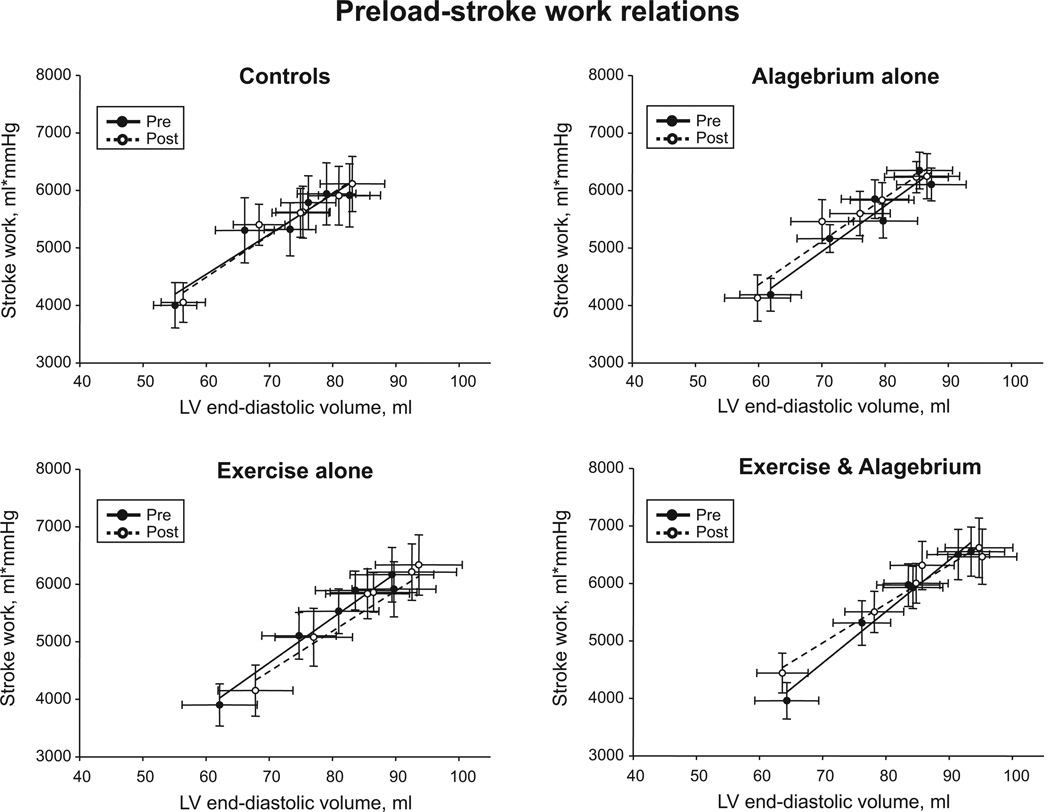

As shown in Figure 2A, the Starling curves were superimposable in all groups after the intervention. Stroke volume (P≥0.42) and PCWP (P≥0.09) were unaffected across all loading conditions in all 4 groups. The slopes of preload-recruitable stroke work relations after intervention were similar to those before intervention, suggesting unaltered LV systolic function in all 4 groups (Figure 3). There were no time effects of alagebrium and exercise training, or an interaction effect of alagebrium, training, and time for measures of LV systolic function.

Figure 2.

Frank Starling relationship. Systolic ventricular performance for controls, alagebrium alone, exercise alone, and exercise and alagebrium before and after the 1-year intervention. Note no differences in stroke volume (SV) index for any given pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) in any of the 4 groups before and after intervention.

Figure 3.

Preload-recruitable stroke work. Lines represent results of linear regression analyses for controls, alagebrium alone, exercise alone, and exercise and alagebrium before and after the intervention. Stroke work was unaffected across all loading conditions in all 4 groups after intervention (P=0.24). LV indicates left ventricle.

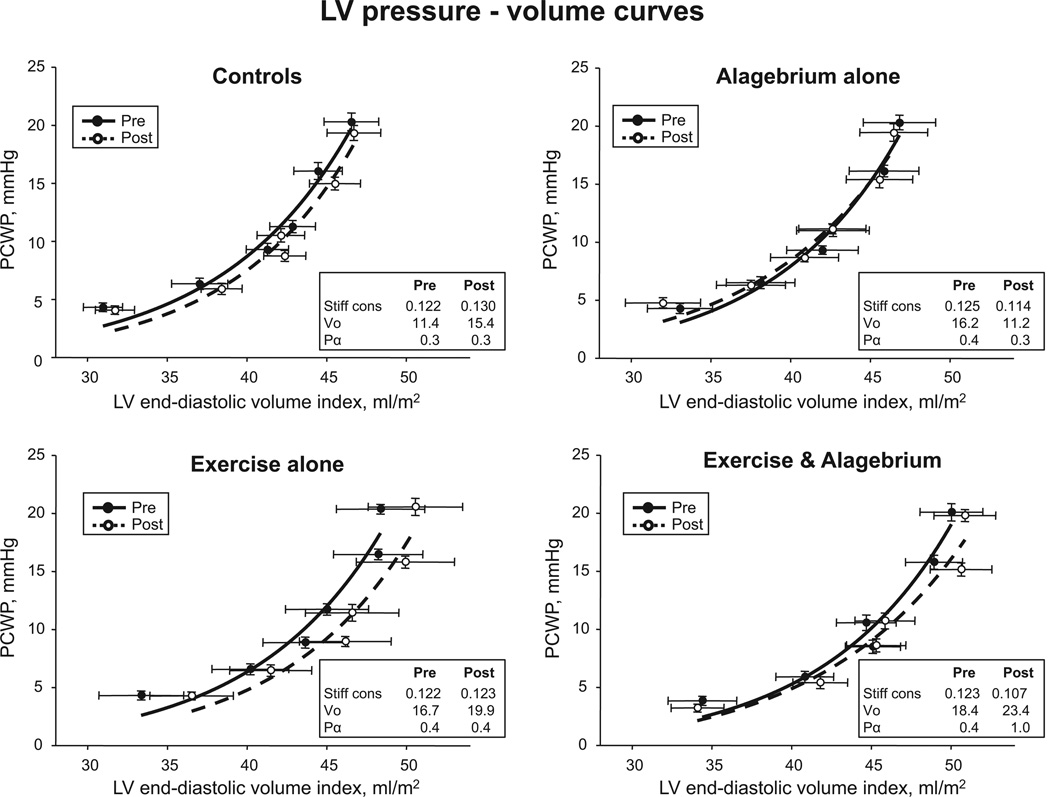

LV Pressure–Volume Curves

The group mean LV pressure–volume curve in exercise and alagebrium was modestly flattened, suggesting improved LV stiffness after the intervention (Figure 4). In alagebrium alone, LVEDV was unaffected at baseline and during saline infusion, but decreased slightly during −30 mm Hg lower-body negative pressure. No improvement in LV stiffness was observed in controls or exercise alone; however, the pressure–volume curve in exercise alone shifted rightward toward increased LV distensibility.

Figure 4.

Left ventricular (LV) diastolic pressure–volume relationships. Pressure–volume curves before and after 1 year of intervention. In exercise alone, LV pressure–volume curves were shifted rightwards with no changes in the slope of pressure–volume curves. In exercise and alagebirum, pressure–volume curves were modestly flattened after intervention. PCWP indicates pulmonary capillary wedge pressure.

An improvement in LV stiffness by alagebrium was observed after 1 year of intervention (medication×time, P=0.04). After adjustment for sex, the effect of alagebrium on LV stiffness was still observed (medication×time, P=0.02). Conversely, exercise training had no favorable effect on LV stiffness (training×time, P=0.46; medication×training×time, P=0.86; Table 3).

Given the significant main effect of alagebrium, further analysis showed that this effect was most prominent in the exercise and alagebrium group, which demonstrated a trend toward an improvement in LV stiffness (LV stiffness constant: 0.127±0.071 versus 0.102±0.031; P=0.07). Conversely, controls (placebo+yoga) tended to increase LV stiffness after 1 year of intervention (0.114±0.059 versus 0.128±0.053; P=0.12). No significant improvement in LV stiffness was observed in alagebrium alone (P=0.21) or exercise alone (P=0.94). Operating stiffness during cardiac loading tended to decrease only in exercise and alagebrium (2.4±1.4 versus 1.7±0.4 mm Hg·mL−1·m2; P=0.06; Table 3).

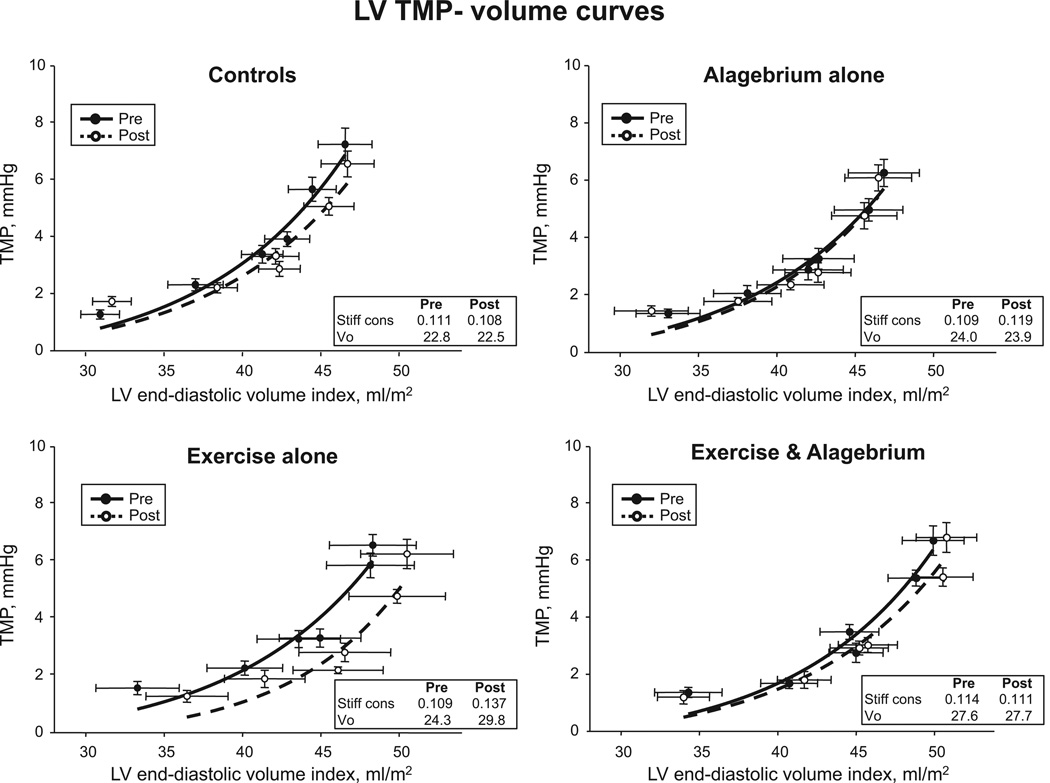

As shown in Figure 5, no changes in the slopes of LV TMP–volume curves were observed in any of the 4 groups after intervention. Myocardial stiffness was not improved in any of the 4 groups (medication×time, P=0.68; training×time, P=0.08; medication×training×time, P=50; Table 3).

Figure 5.

Left ventricular (LV) diastolic transmural pressure (TMP)–volume relationships. Transmural pressure–volume curves before and after 1 year of intervention. No changes were observed in the slopes of pressure–volume curves in the 4 groups.

Discussion

We report for the first time in healthy seniors that 1 year of alagebrium had no effect on LV hemodynamics and geometry, or exercise capacity. However, alagebrium produced a modest improvement of LV stiffness, assessed directly by the LV stiffness constant of invasively measured LV pressure–volume curves compared with placebo, which was most prominent when combined with exercise training.

Effects of a Year of Alagebrium and Exercise Training on LV Compliance

Healthy aging is characterized by a gradual increase in cardiovascular stiffness, which may be caused by collagen accumulation and AGE crosslinks in the interstitial space of the myocardium.9 Consistent with our previous report in mostly men,5 trained with longer duration and higher intensity exercise sessions, we observed that 1 year of exercise did not improve LV stiffness in our older subjects. These results confirm that exercise training started later in life is unlikely to exert favorable effects on LV stiffness in both men and women.

In animal models, alagebrium at the doses used in this study has been shown to decrease AGE deposition,12 lower LV end-diastolic pressure, and reverse age-associated LV stiffening.9 In aged rats, a combination of alagebrium and exercise training had a greater impact on LV stiffness than alagebrium or exercise training alone and essentially reversed many cardiovascular effects of sedentary aging.31 In the present study, alagebrium exerted only a modest effect on LV stiffness, mainly because of the improvement of operating stiffness during cardiac loading in the exercise and alagebrium group. As we did not measure AGE deposition in the interstitial space of the LV, we cannot be certain whether alagebrium broke down established AGE crosslinks.

In the present study, the exercise and alagebrium group demonstrated a trend toward improved LV stiffness by ≈20% after 1 year of intervention. To put these data into a physiologically relevant context, we recently reported in healthy sedentary humans that LV stiffening occurs during the transition between youth and early middle-age (42±4 years) and becomes manifest during late middle-age (57±4 years).2 In these healthy sedentary subjects, the LV stiffness constant obtained using exactly the same techniques as in the present study was greater in late middle-age than that in early middle-age by ≈20%, although this difference was not statistically significant.2 If age-associated LV stiffening develops continuously during the aging process, the 1-year intervention with alagebrium and exercise training might have reversed the age-associated LV stiffening by the equivalent of ≈10 to 15 years.

Although a small favorable effect of alagebrium on age-associated LV stiffening was observed, myocardial stiffness assessed from LV TMP–volume curves was not improved. Consequently, we speculate that alagebrium may have a more favorable effect on the pericardium than the myocardium in healthy older humans; this hypothesis is supported by the observation that operating stiffness was most prominently reduced during cardiac loading (when pericardial constraint is most prominent) in the exercise and alagebrium group.

In the present study, the small increase in LV distensibility (increase in volume for a given pressure without a change in LV stiffness) seen in exercise alone did not seem to be present in exercise and alagebrium. We speculate that alagebrium may have had a modifying effect on the physiological eccentric remodeling induced by this dose of exercise training.

Effects of a Year of Alagebrium and Exercise Training on Hemodynamics and LV Size

A previous study reported in older hypertensive patients with systolic BP of 159±12 mm Hg that 2 months of alagebrium (210 mg once daily) decreased pulse pressure and systolic BP, resulting in an improved arterial compliance.32 In older hypertensive patients with lower systolic BP (146±5 mm Hg), the same duration of alagebrium at a higher dose (210 mg twice daily) had no effects on systolic BP or pulse pressure.33 Thus, the magnitude of the reduction in systolic BP seems to be greater in patients with a higher baseline BP than those with a lower baseline BP.34 In the present study, we observed no effect of alagebrium on supine systolic BP, pulse pressure, or arterial compliance. In contrast to previous studies in hypertensives, we carefully enrolled subjects with no cardiovascular diseases including hypertension. These findings suggest that AGE accumulation might be smaller in the hearts of our healthy older subjects compared with previously examined hypertensive patients.

There has been little information about the effects of alagebrium on LV geometry in humans. In a small, open label pilot study in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and concentric LV hypertrophy, Little et al14 reported that alagebrium for 4 months had no impact on the primary (exercise capacity) or the secondary (aortic distensibility) study outcomes. However, LV mass decreased and LV early diastolic function assessed by Doppler echocardiography improved with no change in LV volumes. They concluded that alagebrium might induce regression of LV hypertrophy and lower estimated LV end-diastolic pressure. Conversely, we did not observe a reduction of directly measured PCWP in either of our alagebrium groups. Moreover, neither LV mass nor LVEDV was affected by alagebrium alone or a combination of alagebrium with exercise training.

Effects of a Year of Alagebrium and Exercise Training on Exercise Performance

We observed significant and similar increases in VO2max in the 2 exercise groups, suggesting that alagebrium does not have a unique effect on VO2max. The increases in VO2max after training in the present study were significantly smaller than that observed previously in another study of older individuals after 1 year of exercise training (19%, 22.8±3.4 versus 27.2±4.3 mL/kg per minute).5 In addition, in contrast to the previous study,5 neither total arterial compliance nor arterial elastance improved after training, resulting in no change in arterial function or stroke volume at least in the resting supine position during catheterization. In the present study, to maximize compliance with the training program, we did not prescribe interval training, which is reported to significantly increase VO2max35; we also did not include any long duration of activities >40 minutes. Therefore, the average duration of exercise training was shorter by ≈50 minutes/wk in the present study. We speculate that the discrepancy of the results between these 2 studies may be related to the lack of interval training and a lack of longer training sessions in this study.

Study Limitations

First, our study might be underpowered by the small number of subjects in each group. As mentioned in the methods section, sample size was estimated based on previous data in aged animals.9 We planned to enroll 15 subjects per group with an expected drop-out of 2 subjects in each group for 1 year and had excellent compliance for alagebrium and exercise training. However, the change in LV stiffness with alagebrium was smaller in healthy humans than reported previously in animal models. Given the small number of the subjects and large variability observed, we were powered to detect a true minimal difference of ±0.045 in LV stiffness constant with a probability of type II error at <20% in exercise and alagebrium. The difference of LV stiffness observed in exercise and alagebrium was 0.0249 (n=14; SD, 0.0555; 95% confidence interval, −0.0071 to 0.0570; power, 0.32) in the present study. These results allow us to exclude with a high degree of confidence, a large, clinically meaningful effect of alagebrium on LV stiffness in otherwise healthy elderly men and women. Second, LV pressure–volume curves were evaluated by the use of mean PCWP as a surrogate for LV end-diastolic pressure. We performed a rigorous screening for cardiovascular disease and excluded subjects who had valvular abnormalities such as mitral regurgitation or pulmonary disease, which might alter the relationship between PCWP and LV end-diastolic pressure. Third, no myocardial biopsy was performed to measure AGEs or AGE-induced collagen crosslinking because of possible risks related to the procedure; therefore, we cannot be certain that alagebrium had the desired effect in our population. However, the basic science underpinning alagebrium is robust, and we used doses that have been well tolerated and documented to be effective in animal and human studies.

Conclusions

Alagebrium had no effect on LV hemodynamics and geometry, or exercise capacity, but produced a modest favorable effect on LV stiffness particularly when combined with exercise training in healthy, previously sedentary seniors.

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE.

Lifelong exercise training maintains a youthful compliance of the left ventricle (LV), whereas a year of exercise training started later in life fails to reverse LV stiffening, possibly because of accumulation of irreversible advanced glycation end products. Alagebrium is a novel drug that breaks advanced glycation end product crosslinks and improves LV stiffness in aged animals. In this study, we prescribed alagebrium (200 mg daily) or placebo combined with aerobic exercise training or contact control in healthy, sedentary older individuals for 1 year. We evaluated overall cardiac function by the use of several modalities, including invasive pressure–volume measurements, exercise testing, and cardiac MRI before and after the training. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the effects of alagebrium and exercise training in healthy aged humans. After intervention, exercise training significantly increased exercise capacity, LV mass, and LV end-diastolic volume. Conversely, alagebrium had little effect on exercise capacity or LV geometry. However, alagebrium showed a modest improvement in LV stiffness compared with placebo. This favorable effect of alagebrium on LV stiffness was most prominent in individuals with combined alagebrium and exercise training. These results show that alagebrium had no effect on hemodynamics, LV geometry, or exercise capacity in previously sedentary seniors. However, alagebrium did show a modest favorable effect on age-associated LV stiffening.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ted Pettle, Olaya Avilez, D’Ann Arthur, and Crystal Dobson for their laboratory assistance.

Sources of Funding

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grant AG17479.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Lakatta EG, Levy D. Arterial and cardiac aging: major shareholders in cardiovascular disease enterprises: Part I: aging arteries: a “set up” for vascular disease. Circulation. 2003;107:139–146. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000048892.83521.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fujimoto N, Hastings JL, Bhella PS, Shibata S, Gandhi NK, Carrick-Ranson G, Palmer D, Levine BD. Effect of ageing on left ventricular compliance and distensibility in healthy sedentary humans. J Physiol. 2012;590(pt 8):1871–1880. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.218271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prasad A, Hastings JL, Shibata S, Popovic ZB, Arbab-Zadeh A, Bhella PS, Okazaki K, Fu Q, Berk M, Palmer D, Greenberg NL, Garcia MJ, Thomas JD, Levine BD. Characterization of static and dynamic left ventricular diastolic function in patients with heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2010;3:617–626. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.867044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arbab-Zadeh A, Dijk E, Prasad A, Fu Q, Torres P, Zhang R, Thomas JD, Palmer D, Levine BD. Effect of aging and physical activity on left ventricular compliance. Circulation. 2004;110:1799–1805. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000142863.71285.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fujimoto N, Prasad A, Hastings JL, Arbab-Zadeh A, Bhella PS, Shibata S, Palmer D, Levine BD. Cardiovascular effects of 1 year of progressive and vigorous exercise training in previously sedentary individuals older than 65 years of age. Circulation. 2010;122:1797–1805. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.973784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brownlee M, Cerami A, Vlassara H. Advanced glycosylation end products in tissue and the biochemical basis of diabetic complications. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:1315–1321. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198805193182007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aronson D. Cross-linking of glycated collagen in the pathogenesis of arterial and myocardial stiffening of aging and diabetes. J Hypertens. 2003;21:3–12. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200301000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zieman SJ, Kass DA. Advanced glycation endproduct crosslinking in the cardiovascular system: potential therapeutic target for cardiovascular disease. Drugs. 2004;64:459–470. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200464050-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asif M, Egan J, Vasan S, Jyothirmayi GN, Masurekar MR, Lopez S, Williams C, Torres RL, Wagle D, Ulrich P, Cerami A, Brines M, Regan TJ. An advanced glycation endproduct cross-link breaker can reverse age-related increases in myocardial stiffness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:2809–2813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040558497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yan SF, Ramasamy R, Naka Y, Schmidt AM. Glycation, inflammation, and RAGE: a scaffold for the macrovascular complications of diabetes and beyond. Circ Res. 2003;93:1159–1169. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000103862.26506.3D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yan SD, Schmidt AM, Anderson GM, Zhang J, Brett J, Zou YS, Pinsky D, Stern D. Enhanced cellular oxidant stress by the interaction of advanced glycation end products with their receptors/binding proteins. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:9889–9897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Candido R, Forbes JM, Thomas MC, Thallas V, Dean RG, Burns WC, Tikellis C, Ritchie RH, Twigg SM, Cooper ME, Burrell LM. A breaker of advanced glycation end products attenuates diabetes-induced myocardial structural changes. Circ Res. 2003;92:785–792. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000065620.39919.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vaitkevicius PV, Lane M, Spurgeon H, Ingram DK, Roth GS, Egan JJ, Vasan S, Wagle DR, Ulrich P, Brines M, Wuerth JP, Cerami A, Lakatta EG. A cross-link breaker has sustained effects on arterial and ventricular properties in older rhesus monkeys. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:1171–1175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.3.1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Little WC, Zile MR, Kitzman DW, Hundley WG, O’Brien TX, Degroof RC. The effect of alagebrium chloride (ALT-711), a novel glucose crosslink breaker, in the treatment of elderly patients with diastolic heart failure. J Card Fail. 2005;11:191–195. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hartog JW, Willemsen S, van Veldhuisen DJ, Posma JL, van Wijk LM, Hummel YM, Hillege HL, Voors AA. BENEFICIAL Investigators. Effects of alagebrium, an advanced glycation endproduct breaker, on exercise tolerance and cardiac function in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13:899–908. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Victor RG, Haley RW, Willett DL, Peshock RM, Vaeth PC, Leonard D, Basit M, Cooper RS, Iannacchione VG, Visscher WA, Staab JM, Hobbs HH. Dallas Heart Study Investigators. The Dallas Heart Study: a population-based probability sample for the multidisciplinary study of ethnic differences in cardiovascular health. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:1473–1480. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.02.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen J, Das S, Barlow CE, Grundy S, Lakoski SG. Fitness, fatness, and systolic blood pressure: data from the Cooper Center Longitudinal Study. Am Heart J. 2010;160:166–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blumenthal JA, Emery CF, Madden DJ, Coleman RE, Riddle MW, Schniebolk S, Cobb FR, Sullivan MJ, Higginbotham MB. Effects of exercise training on cardiorespiratory function in men and women older than 60 years of age. Am J Cardiol. 1991;67:633–639. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(91)90904-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hundley WG, Li HF, Willard JE, Landau C, Lange RA, Meshack BM, Hillis LD, Peshock RM. Magnetic resonance imaging assessment of the severity of mitral regurgitation. Comparison with invasive techniques. Circulation. 1995;92:1151–1158. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.5.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katz J, Milliken MC, Stray-Gundersen J, Buja LM, Parkey RW, Mitchell JH, Peshock RM. Estimation of human myocardial mass with MR imaging. Radiology. 1988;169:495–498. doi: 10.1148/radiology.169.2.2971985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hastings JL, Krainski F, Snell PG, Pacini EL, Jain M, Bhella PS, Shibata S, Fu Q, Palmer MD, Levine BD. Effect of rowing ergometry and oral volume loading on cardiovascular structure and function during bed rest. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2012;112:1735–1743. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00019.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levine BD, Lane LD, Buckey JC, Friedman DB, Blomqvist CG. Left ventricular pressure-volume and Frank-Starling relations in endurance athletes. Implications for orthostatic tolerance and exercise performance. Circulation. 1991;84:1016–1023. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.84.3.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laszlo G. Respiratory measurements of cardiac output: from elegant idea to useful test. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2004;96:428–437. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01074.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chemla D, Hébert JL, Coirault C, Zamani K, Suard I, Colin P, Lecarpentier Y. Total arterial compliance estimated by stroke volume-to-aortic pulse pressure ratio in humans. Am J Physiol. 1998;274(2 pt 2):H500–H505. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.2.H500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen CH, Nakayama M, Nevo E, Fetics BJ, Maughan WL, Kass DA. Coupled systolic-ventricular and vascular stiffening with age: implications for pressure regulation and cardiac reserve in the elderly. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:1221–1227. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00374-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelly RP, Ting CT, Yang TM, Liu CP, Maughan WL, Chang MS, Kass DA. Effective arterial elastance as index of arterial vascular load in humans. Circulation. 1992;86:513–521. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.2.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mirsky I. Assessment of diastolic function: suggested methods and future considerations. Circulation. 1984;69:836–841. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.69.4.836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dauterman K, Pak PH, Maughan WL, Nussbacher A, Ariê S, Liu CP, Kass DA. Contribution of external forces to left ventricular diastolic pressure. Implications for the clinical use of the Starling law. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:737–742. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-10-199505150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belenkie I, Kieser TM, Sas R, Smith ER, Tyberg JV. Evidence for left ventricular constraint during open heart surgery. Can J Cardiol. 2002;18:951–959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glower DD, Spratt JA, Snow ND, Kabas JS, Davis JW, Olsen CO, Tyson GS, Sabiston DC, Jr, Rankin JS. Linearity of the Frank-Starling relationship in the intact heart: the concept of preload recruitable stroke work. Circulation. 1985;71:994–1009. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.71.5.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steppan J, Tran H, Benjo AM, Pellakuru L, Barodka V, Ryoo S, Nyhan SM, Lussman C, Gupta G, White AR, Daher JP, Shoukas AA, Levine BD, Berkowitz DE. Alagebrium in combination with exercise ameliorates age-associated ventricular and vascular stiffness. Exp Gerontol. 2012;47:565–572. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kass DA, Shapiro EP, Kawaguchi M, Capriotti AR, Scuteri A, deGroof RC, Lakatta EG. Improved arterial compliance by a novel advanced glycation end-product crosslink breaker. Circulation. 2001;104:1464–1470. doi: 10.1161/hc3801.097806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zieman SJ, Melenovsky V, Clattenburg L, Corretti MC, Capriotti A, Gerstenblith G, Kass DA. Advanced glycation endproduct crosslink breaker (alagebrium) improves endothelial function in patients with isolated systolic hypertension. J Hypertens. 2007;25:577–583. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328013e7dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bakris GL, Bank AJ, Kass DA, Neutel JM, Preston RA, Oparil S. Advanced glycation end-product cross-link breakers. A novel approach to cardiovascular pathologies related to the aging process. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17(12 pt 2):23S–30S. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wisløff U, Støylen A, Loennechen JP, Bruvold M, Rognmo Ø, Haram PM, Tjønna AE, Helgerud J, Slørdahl SA, Lee SJ, Videm V, Bye A, Smith GL, Najjar SM, Ellingsen Ø, Skjaerpe T. Superior cardiovascular effect of aerobic interval training versus moderate continuous training in heart failure patients: a randomized study. Circulation. 2007;115:3086–3094. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.675041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]