Review on the reciprocal stimulatory effects of proinflammatory Th17 cells, wth immunosuppressive Treg cells.

Keywords: Foxp3, IL-17, TNF, TNFR2, immunosuppression, inflammation

Abstract

Identification of CD4+Foxp3+ Tregs and Th17 modified the historical Th1–Th2 paradigm. Currently, the Th17–Tregs dichotomy provides a dominant conceptual framework for the comprehension of immunity/inflammation and tolerance/immunosuppression in an increasing number of diseases. Targeting proinflammatory Th17 cells or immunosuppressive Tregs has been widely considered as a promising therapeutic strategy in the treatment of major human diseases, including autoimmunity and cancer. The efficacy and safety of such therapy rely on a thorough understanding of immunobiology and interaction of these two subsets of Th cells. In this article, we review recent progress concerning complicated interplay of Th17 cells and Tregs. There is compelling evidence that Tregs potently inhibit Th1 and Th2 responses; however, the inhibitory effect of Tregs on Th17 responses is a controversial subject. There is increasing evidence showing that Tregs actually promote the differentiation of Th17 cells in vitro and in vivo and consequently, enhanced the functional consequences of Th17 cells, including the protective effect in host defense, as well as detrimental effect in inflammation and in the support of tumor growth. On the other hand, Th17 cells were also the most potent Th subset in the stimulation and support of expansion and phenotypic stability of Tregs in vivo. These results indicate that these two subsets of Th cells reciprocally stimulate each other. This bidirectional crosstalk is largely dependent on the TNF–TNFR2 pathway. These mutual stimulatory effects should be considered in devising future Th17 cell- and Treg-targeting therapy.

Introduction

Th cells play central roles in orchestrating innate as well as adaptive immune responses [1]. The Th1–Th2 paradigm, proposed more than 25 years ago [2], has evolved with the identification of distinct additional lineages of immunosuppressive CD4+Foxp3+ Tregs and proinflammatory Th17 cells. Tregs are crucial for immunological homeostasis and play an important role in preventing immune responses to autoantigens [3], while they also dampen host immune responses against pathogens [4] and tumor antigens [5]. Up- or down-regulation of Treg activity has clear, beneficial effects in various animal models, including autoimmune disorder [6] and cancer [7], suggesting a considerable potential for therapeutically targeting Tregs in the treatment of major human diseases. Indeed, ex vivo-expanded human Tregs have the capacity to inhibit the rejection of skin and islet allografts in humanized mouse models [8–10]. Ex vivo-expanded antigen-specific human Tregs hold the promise to prevent GvHD in the treatment of leukemia, while maintaining graft-versus-malignancy capacity [11–14]. On the other hand, immunotherapy by targeting Tregs, including depletion of Tregs, is currently being tested in tumor patients [15].

In contrast to Tregs, Th17 cells have been found to be major stimulatory participants in the pathogenesis of autoimmune disease [16, 17]. Increasing numbers of chronic inflammatory disorders, which were previously attributed to Th1 cells, were found to be caused by Th17 cells [18]. Although Th17 cytokines may provide proinflammatory support of tumor development [19], Th17 cells also contribute to anti-tumor immune responses [19, 20]. Consequently, Th17 cells have been considered to be a promising target in the treatment of autoimmune disorders [21, 22], as well as cancer [19, 20]. For example, treatment with secukinumab, a highly selective human anti-IL-17A mAb, resulted in rapid and sustained reductions of symptoms in patients with psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis [23]. In contrast to its pathogenic role in autoimmune disorders, the contribution of Th17 cells to anti-tumor immunity was recapitulated by a recent report showing that the anti-tumor effect of cyclophosphamide critically depended on Th17 cells, which were induced by intestinal microbiota [24]. In mouse tumor models, infusion of in vitro-differentiated Th17 cells achieved a marked anti-tumor effect, which was even superior to the infusion of in vitro-differentiated Th1 cells [25, 26]. Thus, the targeting of Th17 cells holds promise for the treatment of human cancers.

The differentiation programs of Tregs and Th17 cells are reciprocally interconnected and are probably competitive in using naive CD4 T cells as precursors and TGF-β as a differentiation factor [27–29]. Currently, the Th17–Treg dichotomy tends to become a dominant conceptual framework for comprehending the relationship of immunity/inflammation and tolerance/immunosuppression in a wide spectrum of diseases [30–36]. However, recent studies reveal that Th17 cells and Tregs do not always antagonize each other. Abundant numbers of Th17 cells and Tregs frequently colocalize in the same compartments. Importantly, these two populations of Th cells, although functionally opposite, can actually positively stimulate and support each other. The interplay of Th17 cells and Tregs can be complicated further by their phenotypic plasticity, which has been well-reviewed previously [37] and will not be discussed further in this article. In addition to Foxp3-expressing CD4 Tregs, it is known that other subsets of T cells with immunosuppressive capacity are differentiated from naive CD4 cells during immune responses, including IL-10-producing type 1 Tregs [38] and TGF-β-producing Th3 cells [39]. We will focus our discussion in this article on naturally occurring, thymic-derived, suppressive CD4+Foxp3+ Tregs.

Th17 CELLS AND Tregs FREQUENTLY COLOCALIZE IN THE SAME ANATOMIC COMPARTMENTS

Most Th17 cells in the body reside in the barrier tissues, including intestinal tracts and skin [18]. Interestingly, Tregs are also abundant in these interfaces of host and microbiota [40, 41]. It has been reported that the members of commensal microbiota can induce the generation of Tregs and Th17 cells [42–46]. Interestingly, a recent study showed that the up-regulation of Foxp3 expression by Tregs and increase of Th17 cells simultaneously occurred in NOD mice fed acidic water, which was associated with an alteration in the gut microbiome and a decreased risk of diabetes [47]. However, Th17 cells and Tregs are also frequently most abundant in other anatomical compartments, such as inflamed synovial fluids [48], and in cancerous tissues, such as aggressively growing breast cancer [49], uterine cervical cancer [50], colorectal cancer [51], gastric cancer [52], and malignant pleural effusion [53] in humans, as well as a number of mouse tumor models, including gliomas [54]. Therefore, the physiological relevance of colocalization of these two subsets of CD4 cells likely does more than maintain defense against invading pathogen and tolerance to self-tissues.

Th17 and Tregs intriguingly share many similarities, which may contribute to their colocalization. Th cells, in addition to their distinct cytokine profiles, express characteristic chemokine receptors that direct them to traffic to lymphoid or peripheral tissues. For example, naive Th cells express CCR7, whereas Th1 cells express CXCR3 and CCR5, and Th2 cells express CCR3 and CCR8 [55]. CCR6 is the predominant chemokine receptor shared by Th17 cells and Tregs [56]. Expression of this chemokine receptor was reported to recruit Th17 cells and Tregs simultaneously to inflammatory sites [57] or barrier tissues [58].

It was also clearly demonstrated that the differentiation of Th17 and Tregs requires TGF-β [27–29]. Th17 and Tregs highly express the AHR, which can promote the generation of both cell types by integrating environmental stimuli [59, 60]. Thus, it is likely that Th17 and Tregs could be generated at the sites enriched in TGF-β and respective AHR ligands. However, emerging evidence also favors the idea that these two subsets of Th cells mutually promote each other's generation and expansion, which would contribute to the colocalization of abundant Th17 and Tregs in the same anatomic compartments.

Tregs PROMOTE THE DIFFERENTIATION OF Th17 CELLS

Tregs have clearly been shown to inhibit the activation of Th1 and Th2 cells [61, 62]. Although a certain subset of CD39+Foxp3+ Tregs was reported to inhibit Th17 cells [63], the susceptibility of Th17 cells to Treg-mediated inhibition is still controversial. For example, in experimental mouse gastritis, Tregs markedly inhibited Th1 cell- and Th2 cell-mediated pathogenesis but had no effect on Th17 cell-mediated pathogenesis [64]. In contrast, the majority of studies shows that Tregs actually promote the differentiation as well as function of Th17 cells, as discussed below.

Tregs promote differentiation of Th17 cells in vitro

The first evidence showing the stimulatory effect of Tregs on Th17 cells was actually a study revealing the biological signals for de novo generation of Th17 cells. In this study, Veldhoen and colleagues [29] showed that IL-17-producing T cells were differentiated from naive CD4 cells when cocultured with Tregs in the presence of TLR3, TLR4, or TLR9 stimuli. This led to the finding that TGF-β1, which could be a substitute for Tregs, and IL-6, which was produced by TLR stimuli, were able to induce the differentiation of Th17 cells. Subsequently, Xu and colleagues [65] reported that in the presence of IL-6, Tregs not only induced IL-17 expression by Teffs but themselves also expressed IL-17. Coculturing of Teffs with Tregs inhibited production of the Th1 cytokine (IFN-γ) and Th2 cytokine (IL-4), whereas IL-17 family cytokines, including IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-21, and IL-22, were markedly enhanced [66, 67]. This in vitro effect of Tregs in promoting Th17 differentiation was reportedly mediated by providing TGF-β [65] and consumption of IL-2 [67].

Cotransfer of Tregs promotes differentiation of Th17 cells and inhibits colitis in lymphopenic mice

The critical role of functional Tregs in immune homeostasis can be demonstrated in a mouse colitis model induced by transfer of naive CD4 T cells into Rag1−/− mice [68]. After transfer into Rag−/− mice, naive CD4 cells can be differentiated into Th1 and Th17 cells in the colon [69]. Thus, this model provides a system to evaluate the in vivo effect of Tregs on the differentiation of Th17 and Th1 cells. Sujino and colleagues [70] found three types of Th1 (IL-17A−IFN-γ+) cells to be generated in this system: RORγt− classic Th1 cells that were differentiated directly from naive cells; RORγt+ Th1-like cells and RORγt− alternative Th1 cells that were terminally differentiated from RORγt+ cells via Th17 (IL-17A+IFN-γ−); and Th17/Th1 (IL-17A+IFN-γ+) or Th1-like (IL-17A−IFN-γ+) cells. Tregs not only suppressed Th1 cells but also suppressed the transition of Th17/Th1 cells into alternative Th1 cells, resulting in an accumulation of Th17 and Th17/Th1 cells in mice with inhibition of colitis [70].

Systemic autoimmune disease can be generated in this model by transferring CD4 T cells from the DO11.10 TCR transgenic mouse, specific for the OVA323–339 peptide, into a Rag−/− host, expressing OVA as a secreted antigen [71]. With the use of this model, Lohr and colleagues [71] showed that transfer of OVA-specific Tregs prevented weight loss and skin inflammation, which were associated with the inhibition of T cell accumulation, as well as complete suppression of the proportion of Th1 cells. In contrast, Tregs increased the proportion of IL-17-expressing cells.

In the polyclonal system, e.g., transfer of WT naive CD4 T cells and WT Tregs into Rag−/− mice, we also found that Tregs markedly inhibited development of colitis, accompanied by an inhibition of IFN-γ-producing cells, while increasing IL-17A-producing cells [69]. Th17 cells exhibited a tissue-protective and immunosuppressive effect and consequently, suppressed colon inflammation by multiple mechanisms, including inhibition of pathogenic Th1 responses [72], increase of barrier function of intestinal epithelial cells [73], up-regulation of polymeric IgR and intestinal IgA [74, 75], and production of protective IL-22 [76]. Thus, the Th17-promoting effect of Tregs may contribute to the inhibitory effect on the development of colitis and other inflammatory responses in this model.

Depletion of Tregs inhibits generation of antigen-specific Th17 cells

Chen and colleagues [77] examined the role of Tregs in the in vivo development of antigen-specific Th17 cells. They transferred OT-II T cells into Foxp3.luciDTR4 mice, which were immunized with OVA peptide and CFA. Tregs were depleted by administering diphtheria toxin. Depletion of Tregs at the time of immunization, but not at later time-points, reduced the number of antigen-specific IL-17-producing cells and consequently, reduced inflammatory skin responses [77]. This Th17-promoting effect of Tregs was found to be mediated by consumption of IL-2 [77], a cytokine critical for the maintenance and expansion of Tregs [78] and for the inhibition of differentiation of Th17 cells [79].

Tregs promote beneficial host defense function of Th17 cells against fungal infections

Th17 cells and IL-17 cytokines are critical for oral fungicidal immune responses, based on the recruitment of neutrophils to the oral mucosa and induction of salivary antimicrobial factors [80]. Patients with impaired Th17 responses [81] or lacking Tregs [82] were more susceptible to Candida albicans infection. Pandiyan and colleagues [67] reported that Tregs potently promoted the differentiation of naive CD4 cells into Th17 cells capable of producing the full suite of characteristic cytokines in vitro and in vivo. Tregs did not suppress but actually promoted IL-17A-dependent clearance of fungi during acute C. albicans infection. This is demonstrated by the fact that depletion of Tregs in WT B6 mice resulted in a reduced level of Th17 cells and increased the fungal burden. In addition, in the Rag[−/−] mice cotransfer of Tregs with Teffs resulted in an increase in Th17 cells and enhanced fungal clearance and recovery from C. albicans infection [67]. Therefore, in addition to maintaining immune homeostasis and preventing autoimmunity, Tregs play a positive role in host defense and in clearance of fungal infections, by promoting Th17 responses. Tregs have also been shown to confer protection against viral infections [83, 84]. Whether this effect of Tregs was achieved by collaboration with Th17 cells should be clarified further.

Tregs enhance Th17 cell-mediated immunopathogenesis during intracellular bacterial injections

More recently, it has been shown that upon intracellular Chlamydia muridarum infection, Tregs not only promoted Th17 differentiation from conventional CD4+ T cells but also themselves converted into proinflammatory Th17 cells in in vitro and in vivo settings [66]. Intriguingly, partial depletion of Tregs markedly reduced the Th17 responses, as shown by the attenuated neutrophil infiltration and reduced severity of oviduct inflammation after C. muridarum genital infection [66]. Thus, Tregs play a critical role in the immunopathogenesis in this model, which is completely contradictory to their well-documented immunosuppressive activity. It is worth noting that Th17 responses, enhanced by Tregs, strengthen host resistance to C. albicans infection [67], whereas the same action causes the immunopathology in C. muridarum infection [66], suggesting that the biological outcome of interplay of Tregs and Th17 may be dependent on the specific pathogen.

Allograft rejection triggered by Th17 cells is fueled by Tregs

Tregs are considered as a therapy to induce immune tolerance in clinical transplantation [3]; thus, their interaction with rejection-inducing Th cells should be clarified. Vokaer and colleagues [85] reported that T cell-derived IL-17 was critical for the neutrophil infiltration and rejection of minor antigen-mismatched skin grafts. In this model, depletion of Tregs resulted in a marked reduction of IL-17A mRNA within the grafts and draining LNs, with a marginal increase of IFN-γ mRNA, consistent with the results of a study on silica-induced lung fibrosis [86]. Furthermore, cotransfer of Tregs together with anti-donor naive T cells into Rag−/− mice not only enhanced Th17 differentiation by Teffs, but a considerable number of Tregs by themselves also became IL-17 producers [85]. Thus, the potential of Tregs to promote Th17-mediated, neutrophil-dependent rejection of graft should be considered in Treg-based therapy in bone marrow transplantation and solid organ transplantation.

Tregs increase inflammatory support of tumor growth by Th17 cells

Th17 cells have been reported to play dual roles in tumors: they promote inflammatory support of tumor growth and contribute to the immune surveillance against tumor [19]. In the mouse glioma model, IL-10-producing Th17 cells appeared to support tumor growth [54]. In this model, an elevated number of Tregs promoted the generation of IL-10-producing Th17 cells, while inhibiting IFN-γ-producing Th17 cells [54]. Therefore, multiple mechanisms may be attributed to Tregs in promoting cancer immune evasion, including direct inhibition of anti-tumor Th1 responses and stimulation of tumor-supporting Th17 responses.

Taken together, recent studies do not support the view that Th17 cells are a cellular target of Treg-mediated inhibition. Instead, there is clear in vitro and in vivo evidence that Tregs actually promote the differentiation of Th17 cells and consequently, enhance the beneficial as well as detrimental functions of Th17 cells.

Th17 CELLS PROMOTE THE EXPANSION AND PHENOTYPE STABILITY OF Tregs

In the past decade, extensive study of Tregs greatly improved our understanding of the effect of Tregs on Teffs; however, much less is known about the effect of Teffs on Tregs. Accumulating evidence indicates that in addition to being the cellular target for suppression by Tregs, Teffs can have a marked impact on Tregs. More specifically, Teffs are important in support of sustained suppressive function of Tregs. Among Th subsets, Th17 cells are the most potent stimulators of Tregs, as shown by our recent results. The interactions of Th17 cells and Tregs are bidirectional, and Th17 cells have a considerable effect on Tregs.

Activation of Tregs requires stimulation by Teffs

Tregs constitutively express high levels of functional cytokine receptors, such as CD25 [87, 88] and TNFR2 [89–91], but do not have the capacity to produce ligands for these receptors. This suggests that Tregs may rely on the cytokine producers, such as activated Teffs, for the maintenance of their function.

Thornton and colleagues [92] found that Tregs did not suppress the initial activation of Teffs but exerted their suppressive effects only after production of IL-2 by Teffs, resulting in the expansion of Tregs and the induction of their suppressor function. Early evidence of the in vivo-supportive effect of Teffs for Tregs was shown by Curotto de Lafaille and colleagues [93]. They found that CD25 expression on donor Tregs, defined by CD4+CD25+, was not stable after transfer into recipient mice. However, cotransferred Teffs, by producing IL-2, could maintain the expression of CD25 on Tregs [93]. Furthermore, the same group also showed that IL-2 from Teffs was required for the function of Tregs in the inhibition of EAE [94].

We found previously that the number of Tregs was reduced in mice with EAE, and PTX, contained in the immunogen used to induce EAE, was responsible for the reduction of Tregs [95]. Injection of PTX into a WT mouse resulted in a marked reduction of Tregs [95, 96]. To our surprise, in the absence of IL-6, PTX treatment had the opposite effect and expanded Tregs in vitro [97] and in vivo (data not shown). We therefore tested the effect of proinflammatory cytokines elicited by PTX on Tregs. This led us to find that TNF, though TNFR2, preferentially activated, expanded, and promoted the phenotypic stability of Tregs [69, 89, 98]. Although counterintuitive and contradictory to a previous report [99], our observation is supported by increasing evidence from other investigators [100–103].

TNF–TNFR2 pathways actually also enable Teffs to activate Tregs in vivo, as shown by an elegant study performed by Grinberg-Bleyer and colleagues [104]. They initially found that Tregs proliferated significantly more when coinfused into mice with activated T cells. When islet-specific Teffs were transferred alone, they induced diabetes, whereas mice injected with Tregs alone or Tregs plus Teffs did not develop diabetes. However, upon a second injection of activated Teffs, 3 weeks after the initial injection, mice that had received a first injection of Tregs alone developed diabetes, whereas mice that originally had been injected simultaneously with Tregs and Teffs were protected from diabetes. Thus, the Teffs were indirectly protective by stimulating Treg expansion and suppressive activity. The results of the RNA microarray indicated that TNF/TNFR2 but not IL-2/CD25 was the pathway responsible for the Treg-stimulatory effect of Teffs [104].

Th17 cells produce high levels of TNF: perhaps they should be termed Th-TNF

We determined the identity of the subset of Teffs that was a major TNF producer. We compared Th0, Th1, Th2, and Th17 subsets in vitro, differentiated from naive CD4 cells under standard respective polarized culture conditions. Th17 cells expressed the highest level of TNF (46%), followed by Th1 cells (26%) and Th0 (14%), whereas Th2 cells (6%) expressed the lowest levels of TNF. The TNF expression by Th subsets was stable and remained largely unchanged 5 weeks after transfer into Rag−/− mice [105]. Interestingly, although named for the production of IL-17, Th17 cells also expressed similar or even higher levels of TNF than IL-17A in vitro and in vivo [105]. In addition to being expressed by in vitro-differentiated mouse Th17 cells [106], TNF is expressed by natural Th17 cells present in human patients [107, 108]. Recently, it was reported that the pathogenic effect of Th17 cells was actually mediated by its TNF expression [109]. Thus, this subset of Th cells could also be renamed “Th-TNF”.

Th17 cells stimulate expansion and promote stability of the Treg phenotype, mainly depending on the TNF–TNFR2 pathway

As Th17 cells expressed the highest levels of TNF among Th subsets, they have the potential to stimulate Tregs in vivo. To test this idea, freshly isolated, highly purified Tregs (CD4+Foxp3/gfp+ cells) were transferred alone or cotransferred with Th subsets into Rag−/− mice. After 5 weeks, the number and level of Foxp3 expression by Tregs were determined. The results showed that, when transferred alone, Tregs did not proliferate well in a lymphopenic environment and a majority of them lost Foxp3 expression, which is consistent with our previous report [69]. All types of Th subsets, including Th0 cells, were able to support expansion and phenotypic stability of Tregs in vivo. Among tested Th subsets, Th17 cells were the most potent stimulators of Tregs, resulting in markedly more Tregs with the highest levels of Foxp3 expression. This was followed, in order, by Th1, Th2, and Th0 cells [105]. The potency of the Treg-stimulatory effect of Th subsets (Th17>Th1>Th0) correlated with their capacity to express TNF (Th17>Th1>Th0) but not with their capacity to express IL-2, as Th17 cells are poor producers of IL-2 [110]. Nevertheless, IL-2 also played a role, as the neutralizing antibody against IL-2 partially blocked the stimulatory effect of Th17 cells on Tregs. Other cytokines, in addition to TNF and IL-2, may also contribute to this effect, as Th2 cells expressed relatively lower levels of TNF and IL-2, while having more potent Treg-stimulatory activity than Th0 cells. However, the TNF–TNFR2 pathway appears to be dominant, as the effect of Th17 cells on Tregs was largely abolished when cotransferred with TNFR2-deficient Tregs. Intriguingly, expression of IL-17A and TNF by WT Th17 cells was reduced by up to 80% when cotransferred with Tregs deficient in TNFR2 [105]. Based on these observations, we favor the idea that the TNF–TNFR2 signal is crucial for the reciprocal stimulatory effect of proinflammatory Th17 cells and immunosuppressive Tregs.

Why are Th17 cells most able to stimulate Tregs?

Distinct effector functions of Th subsets have evolved presumably to protect the host efficiently against myriad offending pathogens by mounting a robust immune response. However, excessive and prolonged activation of Th cells can result in the severe inflammation and collateral damage to normal tissues. The capacity of activated Teffs to stimulate Tregs is likely to represent a major mechanism by which a dynamic equilibrium is established between Teffs and Tregs in an ongoing immune or inflammatory response to avoid damage to self. Th17 cells have stem cell-like features [26, 111] and can mediate sustained autoimmune inflammation [112]. It is reasonable to hypothesize that the potent Treg-stimulatory activity of Th17 cells coevolved to counter their robust and prolonged proinflammatory effector function. Th17 cells not only produce TNF by themselves, but the IL-17 cytokine is also able to stimulate the production of TNF from macrophages [113], which can further amplify the Treg-stimulatory effect. Therefore, Th17 cells exert critical functions in host defense, immune responses, and inflammation and together with Tregs, orchestrate the maintenance of immunological homeostasis. Presumably, expanded and activated Tregs are responsible to attenuate and eventually quench the inflammatory cascade induced by Th17 cytokines. For example, activation of neutrophils by Th17 cells [114] could be inhibited by Tregs [115].

CONCLUDING REMARKS

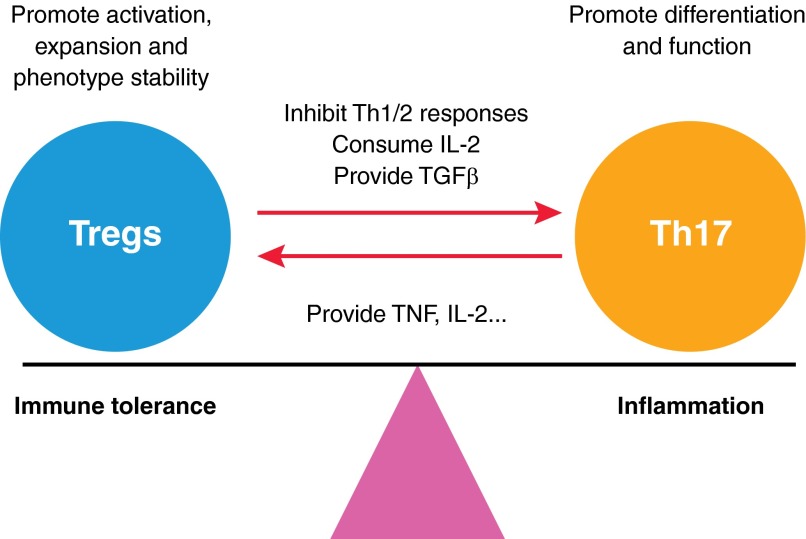

Extensive study of Tregs and Th17 cells has established a critical role of these two subsets of Th cells in the pathogenesis of major human diseases. Consequently, targeting Th17 cells and Tregs, by up-regulating or down-regulating their respective function, can be considered a promising means of treating autoimmune disorders and tumors [21, 22, 116]. However, recent evidence shows that Th17 cells and Tregs do not simply antagonize each other, but instead, they stimulate each other reciprocally (Fig. 1). It is likely that therapeutic manipulation of one of these subsets would have an impact on the other. The complexity of their interactions should be considered carefully when designing therapeutic strategies. For example, increasing Treg activity, by stimulating in vivo expansion of Tregs or adoptive transfer of ex vivo-expanded Tregs, has become a strategy in the treatment of autoimmunity, allograft rejection, and GvHD [116]. Although current data from studies on humanized mice and human patients suggest that such an approach is effective and safe [117, 118], the potential risk of developing acute and chronic Th17-mediated inflammation by such Treg-based treatment, as has occurred in mouse models [85, 86], should be closely monitored. Another possibility—that Th17 cells generated by Tregs can actually promote Treg activity further and that Th17 and Tregs may collaboratively inhibit autoimmunity, allograft rejection, and GvHD—should also be investigated. On the other hand, caution should be used when targeting Th17 cells in the treatment of autoimmunity, as it may reduce immunosuppressive Treg activity as a side-effect. However, the interplay of Th17 and Tregs may also provide new avenues to up- or down-regulate their function therapeutically. For example, although the beneficial effect of Treg depletion in experimental tumor models has been clearly shown [119], complete depletion of Tregs is difficult and risks the development of autoimmune responses in cancer patients. Tumor-infiltrating Tregs expressed markedly higher levels of TNFR2 [90], and abundant Tregs and Th17 cells frequently colocalized in tumors [49–54]; thus, therapeutically targeting Th17 cells may reduce the suppressive activity of tumor-associated Tregs and mitigate the autoimmune risk. Furthermore, Th17 cell-derived TNF may be considered a means to activate and expand Tregs. For example, Treg expansion is usually achieved through agents, such as IL-2 and rapamycin [120–123]. Recently, Okubo and colleagues [100] reported that a TNFR2 agonist had a superb effect on causing homogenous expansion of human Tregs with potent suppressive capacity. Thus, it is worthwhile—using a TNF–TNFR2 pathway-based Th17–Treg interaction or in conjunction with additional Treg-activating agents—in the treatment of autoimmunity, GvHD, and allograft rejection by up-regulation of Treg activity. It is known that Th17 cells and Tregs are not homogenous. For example, a subset of Th17 cells is immunosuppressive [124, 125], whereas a subset of Tregs has the capacity to produce proinflammatory cytokines [126]. Therefore, the interactions between Th17 subsets and Treg subsets merit future investigation. Furthermore, the role of antigenic DCs, which have a major impact on the differentiation, expansion, and function of Tregs [127, 128] and Th17 cells [129, 130] in the reciprocal stimulation of these two Th subsets, also needs to be defined further.

Figure 1. Reciprocal stimulation of Tregs and Th17 cells.

Tregs are able to promote the differentiation and function of Th17 cells, through a mechanism involving the supply of TGF-β, which is required for Th17 differentiation, or inhibition of Th1 and Th2 cytokines and IL-2, which are known to block Th17 differentiation. Induced and natural Th17 cells also stimulate the activation and expansion and promote Foxp3 expression of Tregs by producing TNF, IL-2, or other mediators required for the survival and activation of Tregs. Therefore, the immunosuppressive Tregs and proinflammatory Th17 cells reciprocally stimulate and temper each other, resulting in a dynamic equilibrium in an ongoing immune/inflammatory response.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project has been funded, in whole or in part, with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, U.S. National Institutes of Health, under contract HHSN26120080001E. This research was supported, in part, by the Intramural Research Program of the U.S. National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

Footnotes

- AHR

- aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- EAE

- experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

- Foxp3

- forkhead box p3

- GvHD

- graft-versus-host disease

- Rag−/−

- RAG-deficient

- RORγ

- RAR-related orphan receptor γ

- Teff

- effector T cell

- Th cell

- CD4+ Th cell

- Th17

- IL-17-producing CD4+ T cell

- Treg

- regulatory T cell

AUTHORSHIP

X.C. and J.J.O. contributed to the writing of this review.

DISCLOSURES

The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. government. The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Zhu J., Yamane H., Paul W. E. (2010) Differentiation of effector CD4 T cell populations (*). Annu. Rev. Immunol. 28, 445–489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mosmann T. R., Cherwinski H., Bond M. W., Giedlin M. A., Coffman R. L. (1986) Two types of murine helper T cell clone. I. Definition according to profiles of lymphokine activities and secreted proteins. J. Immunol. 136, 2348–2357 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sakaguchi S., Yamaguchi T., Nomura T., Ono M. (2008) Regulatory T cells and immune tolerance. Cell 133, 775–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Belkaid Y., Rouse B. T. (2005) Natural regulatory T cells in infectious disease. Nat. Immunol. 6, 353–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kryczek I., Wei S., Zou L., Altuwaijri S., Szeliga W., Kolls J., Chang A., Zou W. (2007) Cutting edge: Th17 and regulatory T cell dynamics and the regulation by IL-2 in the tumor microenvironment. J. Immunol. 178, 6730–6733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen X., Oppenheim J. J., Winkler-Pickett R. T., Ortaldo J. R., Howard O. M. (2006) Glucocorticoid amplifies IL-2-dependent expansion of functional FoxP3(+)CD4(+)CD25(+) T regulatory cells in vivo and enhances their capacity to suppress EAE. Eur. J. Immunol. 36, 2139–2149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Onizuka S., Tawara I., Shimizu J., Sakaguchi S., Fujita T., Nakayama E. (1999) Tumor rejection by in vivo administration of anti-CD25 (interleukin-2 receptor α) monoclonal antibody. Cancer Res. 59, 3128–3133 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Issa F., Hester J., Goto R., Nadig S. N., Goodacre T. E., Wood K. (2010) Ex vivo-expanded human regulatory T cells prevent the rejection of skin allografts in a humanized mouse model. Transplantation 90, 1321–1327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wu D. C., Hester J., Nadig S. N., Zhang W., Trzonkowski P., Gray D., Hughes S., Johnson P., Wood K. J. (2013) Ex vivo expanded human regulatory T cells can prolong survival of a human islet allograft in a humanized mouse model. Transplantation 96, 707–716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Issa F., Chandrasekharan D., Wood K. J. (2011) Regulatory T cells as modulators of chronic allograft dysfunction. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 23, 648–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pidala J., Anasetti C. (2010) Can antigen-specific regulatory T cells protect against graft versus host disease and spare anti-malignancy alloresponse? Haematologica 95, 660–665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Veerapathran A., Pidala J., Beato F., Yu X. Z., Anasetti C. (2011) Ex vivo expansion of human Tregs specific for alloantigens presented directly or indirectly. Blood 118, 5671–5680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Veerapathran A., Pidala J., Beato F., Betts B., Kim J., Turner J. G., Hellerstein M. K., Yu X. Z., Janssen W., Anasetti C. (2013) Human regulatory T cells against minor histocompatibility antigens: ex vivo expansion for prevention of graft-versus-host disease. Blood 122, 2251–2261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Di Ianni M., Falzetti F., Carotti A., Terenzi A., Castellino F., Bonifacio E., Del Papa B., Zei T., Ostini R. I., Cecchini D., Aloisi T., Perruccio K., Ruggeri L., Balucani C., Pierini A., Sportoletti P., Aristei C., Falini B., Reisner Y., Velardi A., Aversa F., Martelli M. F. (2011) Tregs prevent GVHD and promote immune reconstitution in HLA-haploidentical transplantation. Blood 117, 3921–3928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nishikawa H., Sakaguchi S. (2014) Regulatory T cells in cancer immunotherapy. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 27C, 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Park H., Li Z., Yang X. O., Chang S. H., Nurieva R., Wang Y. H., Wang Y., Hood L., Zhu Z., Tian Q., Dong C. (2005) A distinct lineage of CD4 T cells regulates tissue inflammation by producing interleukin 17. Nat. Immunol. 6, 1133–1141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Harrington L. E., Hatton R. D., Mangan P. R., Turner H., Murphy T. L., Murphy K. M., Weaver C. T. (2005) Interleukin 17-producing CD4+ effector T cells develop via a lineage distinct from the T helper type 1 and 2 lineages. Nat. Immunol. 6, 1123–1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Weaver C. T., Elson C. O., Fouser L. A., Kolls J. K. (2013) The Th17 pathway and inflammatory diseases of the intestines, lungs, and skin. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 8, 477–512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wilke C. M., Bishop K., Fox D., Zou W. (2011) Deciphering the role of Th17 cells in human disease. Trends Immunol. 32, 603–611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Martin-Orozco N., Muranski P., Chung Y., Yang X. O., Yamazaki T., Lu S., Hwu P., Restifo N. P., Overwijk W. W., Dong C. (2009) T helper 17 cells promote cytotoxic T cell activation in tumor immunity. Immunity 31, 787–798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Maddur M. S., Miossec P., Kaveri S. V., Bayry J. (2012) Th17 cells: biology, pathogenesis of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, and therapeutic strategies. Am. J. Pathol. 181, 8–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Miossec P., Kolls J. K. (2012) Targeting IL-17 and TH17 cells in chronic inflammation. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 11, 763–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Patel D. D., Lee D. M., Kolbinger F., Antoni C. (2013) Effect of IL-17A blockade with secukinumab in autoimmune diseases. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 72 (Suppl. 2), ii116–ii123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Viaud S., Saccheri F., Mignot G., Yamazaki T., Daillere R., Hannani D., Enot D. P., Pfirschke C., Engblom C., Pittet M. J., Schlitzer A., Ginhoux F., Apetoh L., Chachaty E., Woerther P. L., Eberl G., Berard M., Ecobichon C., Clermont D., Bizet C., Gaboriau-Routhiau V., Cerf-Bensussan N., Opolon P., Yessaad N., Vivier E., Ryffel B., Elson C. O., Dore J., Kroemer G., Lepage P., Boneca I. G., Ghiringhelli F., Zitvogel L. (2013) The intestinal microbiota modulates the anticancer immune effects of cyclophosphamide. Science 342, 971–976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Muranski P., Boni A., Antony P. A., Cassard L., Irvine K. R., Kaiser A., Paulos C. M., Palmer D. C., Touloukian C. E., Ptak K., Gattinoni L., Wrzesinski C., Hinrichs C. S., Kerstann K. W., Feigenbaum L., Chan C. C., Restifo N. P. (2008) Tumor-specific Th17-polarized cells eradicate large established melanoma. Blood 112, 362–373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Muranski P., Borman Z. A., Kerkar S. P., Klebanoff C. A., Ji Y., Sanchez-Perez L., Sukumar M., Reger R. N., Yu Z., Kern S. J., Roychoudhuri R., Ferreyra G. A., Shen W., Durum S. K., Feigenbaum L., Palmer D. C., Antony P. A., Chan C. C., Laurence A., Danner R. L., Gattinoni L., Restifo N. P. (2011) Th17 cells are long lived and retain a stem cell-like molecular signature. Immunity 35, 972–985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bettelli E., Carrier Y., Gao W., Korn T., Strom T. B., Oukka M., Weiner H. L., Kuchroo V. K. (2006) Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature 441, 235–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mangan P. R., Harrington L. E., O'Quinn D. B., Helms W. S., Bullard D. C., Elson C. O., Hatton R. D., Wahl S. M., Schoeb T. R., Weaver C. T. (2006) Transforming growth factor-β induces development of the T(H)17 lineage. Nature 441, 231–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Veldhoen M., Hocking R. J., Atkins C. J., Locksley R. M., Stockinger B. (2006) TGFβ in the context of an inflammatory cytokine milieu supports de novo differentiation of IL-17-producing T cells. Immunity 24, 179–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Xu R. C., Zhu H. Q., Li W. P., Zhao X. Q., Yuan H. J., Zheng J., Pan M. (2013) The imbalance of Th17 and regulatory T cells in pemphigus patients. Eur. J. Dermatol. 23, 795–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Huang H., Lu Z., Jiang C., Liu J., Wang Y., Xu Z. (2013) Imbalance between Th17 and regulatory T-cells in sarcoidosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 21463–21473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bas H. D., Baser K., Yavuz E., Bolayir H. A., Yaman B., Unlu S., Cengel A., Bagriacik E. U., Yalcin R. (2014) A shift in the balance of regulatory T and T helper 17 cells in rheumatic heart disease. J. Investig. Med. 62, 78–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chen Z., Ding J., Pang N., Du R., Meng W., Zhu Y., Zhang Y., Ma C., Ding Y. (2013) The Th17/Treg balance and the expression of related cytokines in Uygur cervical cancer patients. Diagn. Pathol. 8, 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Li Q., Wang Y., Yu F., Wang Y. M., Zhang C., Hu C., Wu Z., Xu X., Hu S. (2013) Peripheral Th17/Treg imbalance in patients with atherosclerotic cerebral infarction. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 6, 1015–1027 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhang G. L., Xie D. Y., Lin B. L., Xie C., Ye Y. N., Peng L., Zhang S. Q., Zhang Y. F., Lai Q., Zhu J. Y., Zhang Y., Huang Y. S., Hu Z. X., Gao Z. L. (2013) Imbalance of interleukin-17-producing CD4 T cells/regulatory T cells axis occurs in remission stage of patients with hepatitis B virus-related acute-on-chronic liver failure. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 28, 513–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhao L., Yang J., Wang H. P., Liu R. Y. (2013) Imbalance in the Th17/Treg and cytokine environment in peripheral blood of patients with adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Med. Oncol. 30, 461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kleinewietfeld M., Hafler D. A. (2013) The plasticity of human Treg and Th17 cells and its role in autoimmunity. Sem. Immunol. 25, 305–312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Roncarolo M. G., Gregori S., Battaglia M., Bacchetta R., Fleischhauer K., Levings M. K. (2006) Interleukin-10-secreting type 1 regulatory T cells in rodents and humans. Immunol. Rev. 212, 28–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Weiner H. L. (2001) Induction and mechanism of action of transforming growth factor-β-secreting Th3 regulatory cells. Immunol. Rev. 182, 207–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hirahara K., Liu L., Clark R. A., Yamanaka K., Fuhlbrigge R. C., Kupper T. S. (2006) The majority of human peripheral blood CD4+CD25highFoxp3+ regulatory T cells bear functional skin-homing receptors. J. Immunol. 177, 4488–4494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Littman D. R., Rudensky A. Y. (2010) Th17 and regulatory T cells in mediating and restraining inflammation. Cell 140, 845–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Round J. L., Mazmanian S. K. (2010) Inducible Foxp3+ regulatory T-cell development by a commensal bacterium of the intestinal microbiota. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 12204–12209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ivanov I. I., Atarashi K., Manel N., Brodie E. L., Shima T., Karaoz U., Wei D., Goldfarb K. C., Santee C. A., Lynch S. V., Tanoue T., Imaoka A., Itoh K., Takeda K., Umesaki Y., Honda K., Littman D. R. (2009) Induction of intestinal Th17 cells by segmented filamentous bacteria. Cell 139, 485–498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lathrop S. K., Bloom S. M., Rao S. M., Nutsch K., Lio C. W., Santacruz N., Peterson D. A., Stappenbeck T. S., Hsieh C. S. (2011) Peripheral education of the immune system by colonic commensal microbiota. Nature 478, 250–254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Atarashi K., Tanoue T., Shima T., Imaoka A., Kuwahara T., Momose Y., Cheng G., Yamasaki S., Saito T., Ohba Y., Taniguchi T., Takeda K., Hori S., Ivanov I. I., Umesaki Y., Itoh K., Honda K. (2011) Induction of colonic regulatory T cells by indigenous Clostridium species. Science 331, 337–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Atarashi K., Tanoue T., Oshima K., Suda W., Nagano Y., Nishikawa H., Fukuda S., Saito T., Narushima S., Hase K., Kim S., Fritz J. V., Wilmes P., Ueha S., Matsushima K., Ohno H., Olle B., Sakaguchi S., Taniguchi T., Morita H., Hattori M., Honda K. (2013) Treg induction by a rationally selected mixture of Clostridia strains from the human microbiota. Nature 500, 232–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wolf K. J., Daft J. G., Tanner S. M., Hartmann R., Khafipour E., Lorenz R. G. (2014) Consumption of acidic water alters the gut microbiome and decreases the risk of diabetes in NOD mice. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 10.1369/0022155413519650 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Grose R. H., Millard D. J., Mavrangelos C., Barry S. C., Zola H., Nicholson I. C., Cham W. T., Boros C. A., Krumbiegel D. (2012) Comparison of blood and synovial fluid Th17 and novel peptidase inhibitor 16 Treg cell subsets in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 39, 2021–2031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Benevides L., Cardoso C. R., Tiezzi D. G., Marana H. R., Andrade J. M., Silva J. S. (2013) Enrichment of regulatory T cells in invasive breast tumor correlates with the upregulation of IL-17A expression and invasiveness of the tumor. Eur. J. Immunol. 43, 1518–1528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hou F., Li Z., Ma D., Zhang W., Zhang Y., Zhang T., Kong B., Cui B. (2012) Distribution of Th17 cells and Foxp3-expressing T cells in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in patients with uterine cervical cancer. Clin. Chim. Acta 413, 1848–1854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tosolini M., Kirilovsky A., Mlecnik B., Fredriksen T., Mauger S., Bindea G., Berger A., Bruneval P., Fridman W. H., Pages F., Galon J. (2011) Clinical impact of different classes of infiltrating T cytotoxic and helper cells (Th1, Th2, Treg, Th17) in patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 71, 1263–1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Maruyama T., Kono K., Mizukami Y., Kawaguchi Y., Mimura K., Watanabe M., Izawa S., Fujii H. (2010) Distribution of Th17 cells and FoxP3(+) regulatory T cells in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, tumor-draining lymph nodes and peripheral blood lymphocytes in patients with gastric cancer. Cancer Sci. 101, 1947–1954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ye Z. J., Zhou Q., Zhang J. C., Li X., Wu C., Qin S. M., Xin J. B., Shi H. Z. (2011) CD39+ regulatory T cells suppress generation and differentiation of Th17 cells in human malignant pleural effusion via a LAP-dependent mechanism. Respir. Res. 12, 77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cantini G., Pisati F., Mastropietro A., Frattini V., Iwakura Y., Finocchiaro G., Pellegatta S. (2011) A critical role for regulatory T cells in driving cytokine profiles of Th17 cells and their modulation of glioma microenvironment. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 60, 1739–1750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ebert L. M., Schaerli P., Moser B. (2005) Chemokine-mediated control of T cell traffic in lymphoid and peripheral tissues. Mol. Immunol. 42, 799–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Comerford I., Bunting M., Fenix K., Haylock-Jacobs S., Litchfield W., Harata-Lee Y., Turvey M., Brazzatti J., Gregor C., Nguyen P., Kara E., McColl S. R. (2010) An immune paradox: how can the same chemokine axis regulate both immune tolerance and activation?: CCR6/CCL20: a chemokine axis balancing immunological tolerance and inflammation in autoimmune disease. Bioessays 32, 1067–1076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Turner J. E., Paust H. J., Steinmetz O. M., Peters A., Riedel J. H., Erhardt A., Wegscheid C., Velden J., Fehr S., Mittrucker H. W., Tiegs G., Stahl R. A., Panzer U. (2010) CCR6 recruits regulatory T cells and Th17 cells to the kidney in glomerulonephritis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 21, 974–985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tesmer L. A., Lundy S. K., Sarkar S., Fox D. A. (2008) Th17 cells in human disease. Immunol. Rev. 223, 87–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Veldhoen M., Hirota K., Westendorf A. M., Buer J., Dumoutier L., Renauld J. C., Stockinger B. (2008) The aryl hydrocarbon receptor links TH17-cell-mediated autoimmunity to environmental toxins. Nature 453, 106–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Singh N. P., Singh U. P., Singh B., Price R. L., Nagarkatti M., Nagarkatti P. S. (2011) Activation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) leads to reciprocal epigenetic regulation of FoxP3 and IL-17 expression and amelioration of experimental colitis. PLoS One 6, e23522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Venuprasad K., Kong Y. C., Farrar M. A. (2010) Control of Th2-mediated inflammation by regulatory T cells. Am. J. Pathol. 177, 525–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Koch M. A., Thomas K. R., Perdue N. R., Smigiel K. S., Srivastava S., Campbell D. J. (2012) T-bet(+) Treg cells undergo abortive Th1 cell differentiation due to impaired expression of IL-12 receptor β2. Immunity 37, 501–510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Fletcher J. M., Lonergan R., Costelloe L., Kinsella K., Moran B., O'Farrelly C., Tubridy N., Mills K. H. (2009) CD39+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells suppress pathogenic Th17 cells and are impaired in multiple sclerosis. J. Immunol. 183, 7602–7610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Stummvoll G. H., DiPaolo R. J., Huter E. N., Davidson T. S., Glass D., Ward J. M., Shevach E. M. (2008) Th1, Th2, and Th17 effector T cell-induced autoimmune gastritis differs in pathological pattern and in susceptibility to suppression by regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. 181, 1908–1916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Xu L., Kitani A., Fuss I., Strober W. (2007) Cutting edge: regulatory T cells induce CD4+CD25−Foxp3− T cells or are self-induced to become Th17 cells in the absence of exogenous TGF-β. J. Immunol. 178, 6725–6729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Moore-Connors J. M., Fraser R., Halperin S. A., Wang J. (2013) CD4(+)CD25(+)Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells promote Th17 responses and genital tract inflammation upon intracellular Chlamydia muridarum infection. J. Immunol. 191, 3430–3439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Pandiyan P., Conti H. R., Zheng L., Peterson A. C., Mathern D. R., Hernandez-Santos N., Edgerton M., Gaffen S. L., Lenardo M. J. (2011) CD4(+)CD25(+)Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells promote Th17 cells in vitro and enhance host resistance in mouse Candida albicans Th17 cell infection model. Immunity 34, 422–434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Griseri T., Asquith M., Thompson C., Powrie F. (2010) OX40 is required for regulatory T cell-mediated control of colitis. J. Exp. Med. 207, 699–709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Chen X., Wu X., Zhou Q., Howard O. M., Netea M. G., Oppenheim J. J. (2013) TNFR2 is critical for the stabilization of the CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cell phenotype in the inflammatory environment. J. Immunol. 190, 1076–1084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Sujino T., Kanai T., Ono Y., Mikami Y., Hayashi A., Doi T., Matsuoka K., Hisamatsu T., Takaishi H., Ogata H., Yoshimura A., Littman D. R., Hibi T. (2011) Regulatory T cells suppress development of colitis, blocking differentiation of T-helper 17 into alternative T-helper 1 cells. Gastroenterology 141, 1014–1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Lohr J., Knoechel B., Wang J. J., Villarino A. V., Abbas A. K. (2006) Role of IL-17 and regulatory T lymphocytes in a systemic autoimmune disease. J. Exp. Med. 203, 2785–2791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. O'Connor W., Jr., Kamanaka M., Booth C. J., Town T., Nakae S., Iwakura Y., Kolls J. K., Flavell R. A. (2009) A protective function for interleukin 17A in T cell-mediated intestinal inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 10, 603–609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Yang X. O., Chang S. H., Park H., Nurieva R., Shah B., Acero L., Wang Y. H., Schluns K. S., Broaddus R. R., Zhu Z., Dong C. (2008) Regulation of inflammatory responses by IL-17F. J. Exp. Med. 205, 1063–1075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Cao A. T., Yao S., Gong B., Elson C. O., Cong Y. (2012) Th17 cells upregulate polymeric Ig receptor and intestinal IgA and contribute to intestinal homeostasis. J. Immunol. 189, 4666–4673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Hirota K., Turner J. E., Villa M., Duarte J. H., Demengeot J., Steinmetz O. M., Stockinger B. (2013) Plasticity of Th17 cells in Peyer's patches is responsible for the induction of T cell-dependent IgA responses. Nat. Immunol. 14, 372–379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Zenewicz L. A., Yancopoulos G. D., Valenzuela D. M., Murphy A. J., Stevens S., Flavell R. A. (2008) Innate and adaptive interleukin-22 protects mice from inflammatory bowel disease. Immunity 29, 947–957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Chen Y., Haines C. J., Gutcher I., Hochweller K., Blumenschein W. M., McClanahan T., Hammerling G., Li M. O., Cua D. J., McGeachy M. J. (2011) Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells promote T helper 17 cell development in vivo through regulation of interleukin-2. Immunity 34, 409–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Setoguchi R., Hori S., Takahashi T., Sakaguchi S. (2005) Homeostatic maintenance of natural Foxp3(+) CD25(+) CD4(+) regulatory T cells by interleukin (IL)-2 and induction of autoimmune disease by IL-2 neutralization. J. Exp. Med. 201, 723–735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Laurence A., Tato C. M., Davidson T. S., Kanno Y., Chen Z., Yao Z., Blank R. B., Meylan F., Siegel R., Hennighausen L., Shevach E. M., O'Shea J, J. (2007) Interleukin-2 signaling via STAT5 constrains T helper 17 cell generation. Immunity 26, 371–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Conti H. R., Shen F., Nayyar N., Stocum E., Sun J. N., Lindemann M. J., Ho A. W., Hai J. H., Yu J. J., Jung J. W., Filler S. G., Masso-Welch P., Edgerton M., Gaffen S. L. (2009) Th17 cells and IL-17 receptor signaling are essential for mucosal host defense against oral candidiasis. J. Exp. Med. 206, 299–311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Milner J. D., Brenchley J. M., Laurence A., Freeman A. F., Hill B. J., Elias K. M., Kanno Y., Spalding C., Elloumi H. Z., Paulson M. L., Davis J., Hsu A., Asher A. I., O'Shea J., Holland S. M., Paul W. E., Douek D. C. (2008) Impaired T(H)17 cell differentiation in subjects with autosomal dominant hyper-IgE syndrome. Nature 452, 773–776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Kekalainen E., Tuovinen H., Joensuu J., Gylling M., Franssila R., Pontynen N., Talvensaari K., Perheentupa J., Miettinen A., Arstila T. P. (2007) A defect of regulatory T cells in patients with autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy. J. Immunol. 178, 1208–1215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Lanteri M. C., O'Brien K. M., Purtha W. E., Cameron M. J., Lund J. M., Owen R. E., Heitman J. W., Custer B., Hirschkorn D. F., Tobler L. H., Kiely N., Prince H. E., Ndhlovu L. C., Nixon D. F., Kamel H. T., Kelvin D. J., Busch M. P., Rudensky A. Y., Diamond M. S., Norris P. J. (2009) Tregs control the development of symptomatic West Nile virus infection in humans and mice. J. Clin. Invest. 119, 3266–3277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Lund J. M., Hsing L., Pham T. T., Rudensky A. Y. (2008) Coordination of early protective immunity to viral infection by regulatory T cells. Science 320, 1220–1224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Vokaer B., Van Rompaey N., Lemaitre P. H., Lhomme F., Kubjak C., Benghiat F. S., Iwakura Y., Petein M., Field K. A., Goldman M., Le Moine A., Charbonnier L. M. (2010) Critical role of regulatory T cells in Th17-mediated minor antigen-disparate rejection. J. Immunol. 185, 3417–3425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Song L., Weng D., Liu F., Chen Y., Li C., Dong L., Tang W., Chen J. (2012) Tregs promote the differentiation of Th17 cells in silica-induced lung fibrosis in mice. PLoS One 7, e37286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Sakaguchi S., Sakaguchi N., Asano M., Itoh M., Toda M. (1995) Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by activated T cells expressing IL-2 receptor α-chains (CD25). Breakdown of a single mechanism of self-tolerance causes various autoimmune diseases. J. Immunol. 155, 1151–1164 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Suri-Payer E., Amar A. Z., Thornton A. M., Shevach E. M. (1998) CD4+CD25+ T cells inhibit both the induction and effector function of autoreactive T cells and represent a unique lineage of immunoregulatory cells. J. Immunol. 160, 1212–1218 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Chen X., Baumel M., Mannel D. N., Howard O. M., Oppenheim J. J. (2007) Interaction of TNF with TNF receptor type 2 promotes expansion and function of mouse CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells. J. Immunol. 179, 154–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Chen X., Subleski J. J., Kopf H., Howard O. M., Mannel D. N., Oppenheim J. J. (2008) Cutting edge: expression of TNFR2 defines a maximally suppressive subset of mouse CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ T regulatory cells: applicability to tumor-infiltrating T regulatory cells. J. Immunol. 180, 6467–6471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Chen X., Subleski J. J., Hamano R., Howard O. M., Wiltrout R. H., Oppenheim J. J. (2010) Co-expression of TNFR2 and CD25 identifies more of the functional CD4+FOXP3+ regulatory T cells in human peripheral blood. Eur. J. Immunol. 40, 1099–1106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Thornton A. M., Donovan E. E., Piccirillo C. A., Shevach E. M. (2004) Cutting edge: IL-2 is critically required for the in vitro activation of CD4+CD25+ T cell suppressor function. J. Immunol. 172, 6519–6523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Curotto de Lafaille M. A., Lino A. C., Kutchukhidze N., Lafaille J. J. (2004) CD25− T cells generate CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells by peripheral expansion. J. Immunol. 173, 7259–7268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Furtado G. C., Curotto de Lafaille M. A., Kutchukhidze N., Lafaille J. J. (2002) Interleukin 2 signaling is required for CD4(+) regulatory T cell function. J. Exp. Med. 196, 851–857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Chen X., Winkler-Pickett R. T., Carbonetti N. H., Ortaldo J. R., Oppenheim J. J., Howard O. M. (2006) Pertussis toxin as an adjuvant suppresses the number and function of CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 36, 671–680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Cassan C., Piaggio E., Zappulla J. P., Mars L. T., Couturier N., Bucciarelli F., Desbois S., Bauer J., Gonzalez-Dunia D., Liblau R. S. (2006) Pertussis toxin reduces the number of splenic Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. 177, 1552–1560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Chen X., Howard O. M., Oppenheim J. J. (2007) Pertussis toxin by inducing IL-6 promotes the generation of IL-17-producing CD4 cells. J. Immunol. 178, 6123–6129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Hamano R., Huang J., Yoshimura T., Oppenheim J. J., Chen X. (2011) TNF optimally activatives regulatory T cells by inducing TNF receptor superfamily members TNFR2, 4-1BB and OX40. Eur. J. Immunol. 41, 2010–2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Valencia X., Stephens G., Goldbach-Mansky R., Wilson M., Shevach E. M., Lipsky P. E. (2006) TNF down-modulates the function of human CD4+CD25hi T regulatory cells. Blood 108, 253–261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Okubo Y., Mera T., Wang L., Faustman D. L. (2013) Homogeneous expansion of human T-regulatory cells via tumor necrosis factor receptor 2. Sci. Rep. 3, 3153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Govindaraj C., Scalzo-Inguanti K., Madondo M., Hallo J., Flanagan K., Quinn M., Plebanski M. (2013) Impaired Th1 immunity in ovarian cancer patients is mediated by TNFR2+ Tregs within the tumor microenvironment. Clin. Immunol. 149, 97–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Wammes L. J., Wiria A. E., Toenhake C. G., Hamid F., Liu K. Y., Suryani H., Kaisar M. M., Verweij J. J., Sartono E., Supali T., Smits H. H., Luty A. J., Yazdanbakhsh M. (2013) Asymptomatic plasmodial infection is associated with increased tumor necrosis factor receptor II-expressing regulatory T cells and suppressed type 2 immune responses. J. Infect. Dis. 207, 1590–1599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Chopra M., Riedel S. S., Biehl M., Krieger S., von Krosigk V., Bauerlein C. A., Brede C., Jordan Garrote A. L., Kraus S., Schafer V., Ritz M., Mattenheimer K., Degla A., Mottok A., Einsele H., Wajant H., Beilhack A. (2013) Tumor necrosis factor receptor 2-dependent homeostasis of regulatory T cells as a player in TNF-induced experimental metastasis. Carcinogenesis 34, 1296–1303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Grinberg-Bleyer Y., Saadoun D., Baeyens A., Billiard F., Goldstein J. D., Gregoire S., Martin G. H., Elhage R., Derian N., Carpentier W., Marodon G., Klatzmann D., Piaggio E., Salomon B. L. (2010) Pathogenic T cells have a paradoxical protective effect in murine autoimmune diabetes by boosting Tregs. J. Clin. Invest. 120, 4558–4568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Zhou Q., Hu Y., Howard O. M., Oppenheim J. J., Chen X. (2014) In vitro generated Th17 cells support the expansion and phenotypic stability of CD4Foxp3 regulatory T cells in vivo. Cytokine 65, 56–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Langrish C. L., Chen Y., Blumenschein W. M., Mattson J., Basham B., Sedgwick J. D., McClanahan T., Kastelein R. A., Cua D. J. (2005) IL-23 drives a pathogenic T cell population that induces autoimmune inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 201, 233–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Van Hamburg J. P., Asmawidjaja P. S., Davelaar N., Mus A. M., Colin E. M., Hazes J. M., Dolhain R. J., Lubberts E. (2011) Th17 cells, but not Th1 cells, from patients with early rheumatoid arthritis are potent inducers of matrix metalloproteinases and proinflammatory cytokines upon synovial fibroblast interaction, including autocrine interleukin-17A production. Arthritis Rheum. 63, 73–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Kim C. J., McKinnon L. R., Kovacs C., Kandel G., Huibner S., Chege D., Shahabi K., Benko E., Loutfy M., Ostrowski M., Kaul R. (2013) Mucosal Th17 cell function is altered during HIV infection and is an independent predictor of systemic immune activation. J. Immunol. 191, 2164–2173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Li C. R., Mueller E. E., Bradley L. M. (2014) Islet antigen-specific Th17 cells can induce TNF-α-dependent autoimmune diabetes. J. Immunol. 192, 1425–1432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Quintana F. J., Jin H., Burns E. J., Nadeau M., Yeste A., Kumar D., Rangachari M., Zhu C., Xiao S., Seavitt J., Georgopoulos K., Kuchroo V. K. (2012) Aiolos promotes TH17 differentiation by directly silencing IL2 expression. Nat. Immunol. 13, 770–777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Kryczek I., Zhao E., Liu Y., Wang Y., Vatan L., Szeliga W., Moyer J., Klimczak A., Lange A., Zou W. (2011) Human TH17 cells are long-lived effector memory cells. Sci. Transl. Med. 3, 104ra100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Shi G., Ramaswamy M., Vistica B. P., Cox C. A., Tan C., Wawrousek E. F., Siegel R. M., Gery I. (2009) Unlike Th1, Th17 cells mediate sustained autoimmune inflammation and are highly resistant to restimulation-induced cell death. J. Immunol. 183, 7547–7556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Jovanovic D. V., Di Battista J. A., Martel-Pelletier J., Jolicoeur F. C., He Y., Zhang M., Mineau F., Pelletier J. P. (1998) IL-17 stimulates the production and expression of proinflammatory cytokines, IL-β and TNF-α, by human macrophages. J. Immunol. 160, 3513–3521 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Pelletier M., Maggi L., Micheletti A., Lazzeri E., Tamassia N., Costantini C., Cosmi L., Lunardi C., Annunziato F., Romagnani S., Cassatella M. A. (2010) Evidence for a cross-talk between human neutrophils and Th17 cells. Blood 115, 335–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Lewkowicz P., Lewkowicz N., Sasiak A., Tchorzewski H. (2006) Lipopolysaccharide-activated CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells inhibit neutrophil function and promote their apoptosis and death. J. Immunol. 177, 7155–7163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Tran D. Q., Shevach E. M. (2009) Therapeutic potential of FOXP3(+) regulatory T cells and their interactions with dendritic cells. Hum. Immunol. 70, 294–299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Brunstein C. G., Miller J. S., Cao Q., McKenna D. H., Hippen K. L., Curtsinger J., Defor T., Levine B. L., June C. H., Rubinstein P., McGlave P. B., Blazar B. R., Wagner J. E. (2011) Infusion of ex vivo expanded T regulatory cells in adults transplanted with umbilical cord blood: safety profile and detection kinetics. Blood 117, 1061–1070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Issa F., Hester J., Milward K., Wood K. J. (2012) Homing of regulatory T cells to human skin is important for the prevention of alloimmune-mediated pathology in an in vivo cellular therapy model. PLoS One 7, e53331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Shimizu J., Yamazaki S., Sakaguchi S. (1999) Induction of tumor immunity by removing CD25+CD4+ T cells: a common basis between tumor immunity and autoimmunity. J. Immunol. 163, 5211–5218 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Shin H. J., Baker J., Leveson-Gower D. B., Smith A. T., Sega E. I., Negrin R. S. (2011) Rapamycin and IL-2 reduce lethal acute graft-versus-host disease associated with increased expansion of donor type CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Blood 118, 2342–2350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Matsuoka K., Koreth J., Kim H. T., Bascug G., McDonough S., Kawano Y., Murase K., Cutler C., Ho V. T., Alyea E. P., Armand P., Blazar B. R., Antin J. H., Soiffer R. J., Ritz J. (2013) Low-dose interleukin-2 therapy restores regulatory T cell homeostasis in patients with chronic graft-versus-host disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 5, 179ra43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Koreth J., Matsuoka K., Kim H. T., McDonough S. M., Bindra B., Alyea E. P., 3rd, Armand P., Cutler C., Ho V. T., Treister N. S., Bienfang D. C., Prasad S., Tzachanis D., Joyce R. M., Avigan D. E., Antin J. H., Ritz J., Soiffer R. J. (2011) Interleukin-2 and regulatory T cells in graft-versus-host disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 365, 2055–2066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Kopf H., de la Rosa G. M., Howard O. M., Chen X. (2007) Rapamycin inhibits differentiation of Th17 cells and promotes generation of FoxP3+ T regulatory cells. Int. Immunopharmacol. 7, 1819–1824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Esplugues E., Huber S., Gagliani N., Hauser A. E., Town T., Wan Y. Y., O'Connor W., Jr., Rongvaux A., Van Rooijen N., Haberman A. M., Iwakura Y., Kuchroo V. K., Kolls J. K., Bluestone J. A., Herold K. C., Flavell R. A. (2011) Control of TH17 cells occurs in the small intestine. Nature 475, 514–518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Marwaha A. K., Leung N. J., McMurchy A. N., Levings M. K. (2012) TH17 cells in autoimmunity and immunodeficiency: protective or pathogenic? Front. Immunol. 3, 129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Pesenacker A. M., Bending D., Ursu S., Wu Q., Nistala K., Wedderburn L. R. (2013) CD161 defines the subset of FoxP3+ T cells capable of producing proinflammatory cytokines. Blood 121, 2647–2658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Maldonado R. A., von Andrian U. H. (2010) How tolerogenic dendritic cells induce regulatory T cells. Adv. Immunol. 108, 111–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Yamazaki S., Inaba K., Tarbell K. V., Steinman R. M. (2006) Dendritic cells expand antigen-specific Foxp3+ CD25+ CD4+ regulatory T cells including suppressors of alloreactivity. Immunol. Rev. 212, 314–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Segura E., Touzot M., Bohineust A., Cappuccio A., Chiocchia G., Hosmalin A., Dalod M., Soumelis V., Amigorena S. (2013) Human inflammatory dendritic cells induce Th17 cell differentiation. Immunity 38, 336–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Yu C. F., Peng W. M., Oldenburg J., Hoch J., Bieber T., Limmer A., Hartmann G., Barchet W., Eis-Hubinger A. M., Novak N. (2010) Human plasmacytoid dendritic cells support Th17 cell effector function in response to TLR7 ligation. J. Immunol. 184, 1159–1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]