Abstract

Bendamustine has efficacy in multiple myeloma with a toxicity profile limited to myelosuppression. We hypothesized that adding bendamustine to autologous stem cell transplant conditioning in myeloma would enhance response without significant additional toxicity. We conducted a phase 1 trial adding escalating doses of bendamustine to the current standard conditioning of melphalan 200mg/m2. Twenty-five subjects were enrolled onto 6 cohorts. A maximum tolerated dose was not encountered and the highest dose level cohort of bendamustine 225mg/m2 + melphalan 200mg/m2 was expanded to further evaluate safety. Overall, there was no transplant related mortality and only 1 grade 4 dose-limiting toxicity was observed. Median number of days to neutrophil and platelet engraftment was 11 (9-14) and 13 (10-21), respectively. Disease responses at day +100 post-transplant were: progression in 5 (21%), partial response in 1 (4%), very good partial response in 7 (33%), complete response in 1 (4%), and stringent complete response in 9 (38%). Six patients (24%) with preexisting high-risk disease died from progressive myeloma during study follow-up, all at or beyond 100 days after ASCT. Bendamustine up to a dose of 225mg/m2 added to autologous stem cell transplant conditioning with high dose melphalan in multiple myeloma did not exacerbate expected toxicities.

Introduction

High dose chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) has been a mainstay of therapy for the treatment of multiple myeloma (MM) since randomized trials in the 1990s showed superiority to conventional chemotherapy.1,2 The role and timing of ASCT have become more controversial since the advent of the highly effective novel therapies thalidomide, lenalidomide, and bortezomib; however, several randomized trials have shown that ASCT can further improve response rates and clinical outcomes for eligible MM patients whether induction is performed with either conventional or novel therapies.3-5 Multiple analyses show that complete response (CR) in multiple myeloma is a surrogate for extended progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS), and ASCT remains a useful tool to increase CR rate.6-8 Initial conditioning regimens evolved quickly early in the development of ASCT in MM, starting with combinations of total body irradiation (TBI) and high-dose melphalan with eventual abandonment of the TBI after a randomized study by the Intergroupe Francophone du Myelome (IFM) showed no advantage of the TBI+melphalan 140mg/m2 compared to a less toxic conditioning regimen of melphalan 200 mg/m2 (MEL200).1 Since the establishment of MEL200 as the standard of care, several studies have been undertaken to attempt to improve on the clinical outcomes of ASCT by altering conditioning. Strategies including increasing the total melphalan dose in a second planned tandem transplant and adding the monoclonal anti-interleukin-6 have thus far not convincingly shown superiority to the standard MEL200 regimen, although a subset of patients achieving less than VGPR may benefit from more chemotherapy.9 The addition of oral busulfan to melphalan has been explored and demonstrated an approximately 10 month PFS advantage; however, the regimen was abandoned due to an unacceptable rate of veno-occlusive disease.10 As of yet, there are no other large randomized studies comparing the MEL200 to a more intensive cytotoxic regimen in MM.

Bendamustine is a synthetic chemotherapeutic agent that combines the alkylating properties of a mustard group with the antimetabolic activity of a purine analog. It can induce responses in disease resistant to other alkylating agents via direct induction of apoptosis, inhibition of mitosis, and activation of an alternative DNA repair pathway distinct from standard alkylator mechanisms of action.11 Bendamustine has proven activity in both newly diagnosed and in relapsed or refractory MM. In newly diagnosed MM, the combination of bendamustine and prednisone was shown to be superior to melphalan and prednisone, with a longer time to treatment failure (14 vs. 10 months) and a higher CR rate (32 vs. 13%).12 For relapsed or refractory MM, bendamustine in combination with thalidomide and dexamethasone was shown to have an overall response rate of 26% in a group of heavily pretreated patients (median 5 prior lines of therapy).13 A French compassionate use program summary on the efficacy of single-agent bendamustine in a similar group of MM patients after relapse from multiple prior therapies, (including alkylators, steroids, IMiDs, and bortezomib), reported an overall response rate of 30%, with a median overall survival of 12.4 months.14 A recent phase 1/2 study of the bendamustine + lenalidomide + dexamethasone (BLD) combination in relapsed or refractory MM showed encouraging activity with an overall response rate of 76% in a patient population that had a median of three prior therapies.15 Bendamustine also has demonstrated activity in MM after relapse from prior autologous stem cell transplant, with an overall response rate of 55% and PFS of 26 weeks, again intimating at a non-cross resistance with alkylating therapy.16 The primary side effects of bendamustine encountered in the mentioned studies were due to bone marrow suppression; extramedullary toxicity of is infrequent and usually mild.

We hypothesized that the addition of bendamustine to autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) conditioning in MM would enhance response without significant increase in toxicity. Bendamustine has already been shown to be a feasible part of a modified BeEAM (bendamustine, etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan) autologous stem cell transplant conditioning regimen for non-Hodgkin lymphoma with acceptable safety and promising efficacy.17 We now report the results of a phase 1 study adding escalating doses of bendamustine to the melphalan 200mg/m2.

Methods

Eligibility

Patients were eligible to participate if they had pathologically confirmed active MM, received prior induction therapy, age > 18 years, life expectancy > 12 weeks, and had at least 2 × 106 CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells (HPCs) mobilized in preparation for ASCT. Eligibility for ASCT included Karnofsky performance status ≥ 70%, left ventricular ejection fraction > 40%, lung diffusion capacity (DLCO) > 45%, creatinine clearance > 60cc/min, and otherwise no other active infections, pregnancy, or other major health concerns. Additional eligibility criteria included serum aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase less than 5x the upper limit of normal and serum total bilirubin less than 3x the upper limit of normal. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Weill Medical College of Cornell University, New York Presbyterian Hospital-Cornell Medical Center, in accordance with federal regulations and the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients signed written informed consent prior to study enrollment. This trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, identifier:NCT00916058.

Conditioning Regimen and Supportive Care

Increasing doses of bendamustine were added to high-dose melphalan (melphalan 100mg/m2 daily on Day -2 and Day -1) according to a modified Fibonacci schedule in a 3+3 phase 1 study design until onset of dose limiting toxicity (DLT). Dose escalation of bendamustine was performed according to a modified Fibonacci scheme. The following bendamustine cohorts were studied: 1) 30 mg/m2 given on day -1; 2) 60 mg/m2 on day - 1; 3) 90 mg/m2 on day -1; 4) 60mg/m2 on days -2 and -1 (total dose 120mg/m2); 5) 90 mg/m2 on day -2 and 60mg/m2 on day -1 (total dose 150mg/m2); 6) 125 mg/m2 on day -2 and 100mg/m2 on day -1 (total dose 225mg/m2). Dose escalation of bendamustine was limited to a maximum of 225mg/m2 due to a prior report of cardiac toxicity in patients receiving bendamustine at a dose of 280mg/m2 once every 3 weeks as a single agent to treat solid tumors.18 Three subjects were enrolled in each cohort; if a dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) was encountered at a particular dose level, the cohort at this dose level was expanded to 6 patients. If two DLTs occurred in the same dose level, the prior dose level was defined as the maximum tolerated dose (MTD). If no MTD was found at any dose level, the plan to was to expand the highest dose level (cohort 6) to reach a study total of 25 patients to further evaluate safety.

Patients were followed for prospectively for adverse events from the start of conditioning (Day -2) through Day+100 from ASCT. Toxicities were assessed on a daily basis starting from the beginning of conditioning chemotherapy until hospital discharge; thereafter, toxicities were assessed on a monthly basis. All adverse events were first documented by the study transplant physicians (Tomer Mark, MD/MSc, Usama Gergis MD, Roger Pearse MD/PhD, Sebastian Mayer MD, Koen Van Besien MD/PhD, and Tsiporah Shore MD) and thereafter collated and graded by two independent reviewers, (Tomer Mark MD/MSc and Whitney Reid BA) according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Averse Events version 4.0 (CTCAEv4). DLT in a cohort was defined as any grade 3 CTCAEv4 non-hematologic adverse event that did not resolve within 72 hours, or any occurrence of a grade 4 CTCAEv4 non-hematologic adverse event. In addition, failure to engraft with an absolute neutrophil count of 500/μl and platelet count of 20,000/μl untransfused by day 35 were considered dose limiting toxicities.

Oral cryotherapy with ice chips was offered to each subject during melphalan infusion. Stem cell infusion of at least 2 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg was performed at 24-48 hours after the last dose of melphalan. All patients received G-CSF support starting day +1 until absolute neutrophil count (ANC) exceeded 1000 cells/μl for 48 hours. Patients received levofloxacin, acyclovir, and fluconazole antimicrobial prophylaxis starting day +1, red blood cell and platelet transfusions as needed, and other supportive care as an inpatient from the first dose of chemotherapy until wbc engraftment, defined as ANC > 1000/μl.

Response Determination

Serum and urine protein electrophoresis with immunofixation as well as free light chain determinations were done prior to transplant, day +30, day +60, and thereafter every 6 months to assess disease response as per International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) criteria.19 Bone marrow biopsy and skeletal imaging, either by skeletal survey or PET-CT scan, were performed prior to and 100 days after stem cell infusion to further assess baseline and post-ASCT disease status. Karyotyping and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) were performed on each bone marrow aspirate sample. Progression-free survival was defined as time elapsed between the stem cell infusion (Day 0) and disease progression. Overall survival was defined as time elapsed between Day 0 and death from any cause.

Study Design and Statistical Analysis

The primary endpoint of this study was to determine the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of bendamustine added to high-dose melphalan via standard 3+3 phase 1 design. Secondary endpoints included overall response rate (ORR), progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS). ORR was determined for each enrolled subject on the intent-to-treat principle. PFS and OS were estimated according to the Kaplan-Meier method. A Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to evaluate the impact of tumor and patient characteristics on survival outcomes. All P values are 2-sided with statistical significance evaluated at the 0.05 α level. All analyses were performed in Stata version 10.1 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX).

Results

Study Population

A total of 25 transplant-eligible patients who had received prior induction therapy for MM were enrolled and constituted the treatment population. All patients were followed for toxicity, stem cell engraftment, and treatment response. Patient baseline demographics and disease characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Briefly, patients had a median age of 56 (range 37–65). Intermediate (stage II) or high-risk (stage III) disease was present in 75% of patients by Durie-Salmon criteria, and 55% of patients as defined by the International Staging System (ISS). The isotype distribution of M-proteins reflected the typical MM population (IgG: 64%, IgA: 24%, free light chain-only: 12%). Karyotype and FISH analyses were performed in all patients. High risk cytogenetic abnormalities, defined as the presence of any one or more of the following: del(17p), t(4;14), t(14;16), amp(1q), del(1p), complex karyotype, del(13q) karyotype, were detected in 28% of the patients. Extramedullary myeloma was present in 20% of patients. When possible, a Ki67 score was generated by immunohistochemical co-staining of CD138 and Ki67.20 A high Ki67 score or ≥10% was detected by immunohistochemistry in 32% of patients, indicating particularly high-risk disease. Treatment history prior to transplant was collected for each patient. A prior line of therapy was defined as a predetermined course of treatment according to IMWG criteria.19 Median number of prior lines of therapy was 1, (range 1-3). All patients had received a novel agent at some point during induction therapy, either lenalidomide (68%) or bortezomib (64%) alone or in combination, while fewer had regimens including thalidomide (20%), liposomal doxorubicin (16%), or an alkylating agent, such as cyclophosphamide (24%). Patient response to induction therapy just prior to transplant ranged from progression of disease (POD) 4%, partial response (PR) 24%, very good partial response (VGPR) 32%, CR 20%, stringent complete response (SCR) 20%.

Table 1.

Patient and disease characteristics (N=25)

| Median age, y (range) | 56 (37-65) |

| Sex, N (%) | |

| Male | 14 (56) |

| Female | 11 (44) |

| Durie-Salmon classification, N=24, (%) | |

| Stage Ia | 6 (25) |

| Stage IIa | 7 (29) |

| Stage IIIa | 8 (33) |

| Stage IIIb | 3 (13) |

| International Staging System Classification, N=20, (%) | |

| Stage 1 | 9 (45) |

| Stage 2 | 7 (35) |

| Stage 3 | 4 (20) |

| Immunoglobulin Isotype, N (%) | |

| IgG-κ | 12 (48) |

| IgG-λ | 4 (16) |

| IgA-κ | 3 (12) |

| IgA-λ | 3 (12) |

| Free κ | 2 (8) |

| Free λ | 1 (4) |

| Karnofsky Performance Status prior to ASCT, N (%) | |

| 100 | 6 (24) |

| 90 | 12 (48) |

| 80 | 5 (20) |

| 70 | 1 (4) |

| 60 | 1 (4) |

| Cytogenetic Risk Category, N (%)* | |

| Low Risk | 18 (72) |

| High Risk | 7 (28) |

| Ki67 score, N=22, N (%)** | |

| ≥10% | 7 (32) |

| < 10% | 15 (68) |

| Presence of Extramedullary Disease, N (%) | |

| Yes | 4 (16) |

| No | 21 (84) |

| Lines of Prior Therapy, N (%) | |

| 1 | 19 (76) |

| 2 | 2 (8) |

| 3 | 4 (16) |

| Therapy Exposure History, N (%) | |

| Thalidomide | 5 (20) |

| Lenalidomide | 17 (68) |

| Bortezomib | 16 (64) |

| Alkylating Agent | 6 (24) |

| Liposomal Doxorubicin | 4 (16) |

| Maximum disease response prior to ASCT, N (%) | |

| Progression of disease | 1 (4) |

| Partial response | 6 (24) |

| Very good partial response | 8 (32) |

| Complete response | 5 (20) |

| Stringent complete response | 5 (20) |

High risk cytogenetics, [number of patients]: del 13q karyotype, [5]; del 17p, [1]; t(14;16),[1]; amp 1q or del 1p,[4]; complex karyotype, [5].

Ki67 score is the ratio of Ki67 positive cells to CD138 cells on immunohistochemical staining of the bone marrow aspirate.

Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation

Stem cell collection and engraftment data are listed in Table 2. All 25 patients received peripheral blood hematopoietic stem cells, with the choice of mobilization regimen at the discretion of the transplant physician. All patients successfully engrafted. Median number of days to neutrophil and platelet engraftment was 11 (9-14) and 13 (11-21), respectively. Median number of days on G-CSF was 12 (9-15). Patients stayed in the hospital for a median of 14 days (range 11–22) after stem cell infusion. The engraftment kinetics seen for escalating bendamustine and melphalan conditioning in this study are similar to those reported previously with a MEL200 conditioning regimen.21,22

Table 2.

Stem cell collection and engraftment

| Mobilization regimen, n(%) | |

| G-CSF alone | 4 (16) |

| G-CSF + Plerixafor | 14 (56) |

| G-CSF + Alkylating chemotherapy | 7 (28) |

| Median number of CD34+ cells reinfused, n (range) | 4.22 (2.68-12.66) |

| Median days until ANC > 1000/μl, n (range) | 11 (9-14) |

| Median days of G-CSF, n (range) | 12 (9-15) |

| Median days until platelets > 20 × 103/μl, n (range) | 13 (10-21) |

| Median days to hospital discharge, n (range) | 14 (11-22) |

ANC: absolute neutrophil count

Non-Hematologic Toxicity

All subjects were followed from Day 0 through Day 100 for non-hematologic toxicity, with adverse events listed in Table 3. All grade 4 events occurred in one subject in cohort 2 (bendamustine dose of 60mg/m2 on Day -1) and comprised the single DLT in this study. The DLT seen was grade 4 respiratory compromise, which required ventilator support for 24 hours in the setting of culture-negative neutropenic sepsis. The same subject also experienced grade 3 paroxysmal atrial arrhythmia during the septic episode. The DLT was not considered to be directly related to bendamustine. All other grade 3 non-infectious toxicities listed in Table 3 occurred in one subject who experienced a hypersensitivity reaction to platelet transfusion, resulting in transient hypotension, hypoxia, and delirium which resolved in 24 hours and was not considered to be a DLT.

Table 3.

Non-hematologic Averse Events (N=25)*

| Adverse Event | Grade 1 n (%) | Grade 2 n (%) | Grade 3 n (%) | Grade 4 n (%) | Total n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal | |||||

| Oral Mucositis | 13 (52) | 8 (32) | 2 (8) | 23 (92) | |

| Diarrhea | 17 (68) | 4 (16) | 1 (4) | 22 (88) | |

| Nausea or Vomiting | 20 (80) | 2 (8) | 22 (88) | ||

| Anorexia | 11 (44) | 5 (20) | 16 (64) | ||

| Dyspepsia | 11 (44) | 11 (44) | |||

| Constipation | 5 (20) | 1 (4) | 6 (24) | ||

| Reflux | 3 (12) | 1 (4) | 4 (16) | ||

| Xerostomia | 4 (16) | 1 (4) | 5 (20) | ||

| Dysgeusia | 3 (12) | 2 (8) | 5 (20) | ||

| Rectal bleeding | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | |||

| Infectious | |||||

| Fever | 10 (40) | 3 (12) | 13 (52) | ||

| Sepsis | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | |||

| Upper Respiratory Infection | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | |||

| Pneumonia | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | |||

| Oral thrush | 2 (8) | 2 (8) | |||

| C. difficile colitis | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | |||

| Streptococcus mitus bacteremia | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | |||

| Staphylococcus haemolytica bacteremia, line related | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | |||

| Microsporidia enteritis | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | |||

| Rotavirus enterocolitis | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | |||

| E. coli bacteremia | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | |||

| Blepharitis | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | |||

| Tinea cruris | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | |||

| Tinea pedis | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | |||

| Sinusitis | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | |||

| Respiratory | 1 (4) | ||||

| Dyspnea | 4 (16) | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 6 (24) | |

| Cough | 2 (8) | 2 (8) | 4 (16) | ||

| Hypoxia | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | |||

| Pleural effusion | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | |||

| Renal | |||||

| Pre-renal Acute Kidney Injury | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | |||

| Dysuria | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | |||

| Cardiac | |||||

| Palpitations | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | |||

| Peripheral edema | 7 (28) | 7 (28) | |||

| Hypotension | 2 (8) | 1 (4) | 3 (12) | ||

| Hypertension | 3 (12) | 3 (12) | |||

| Atrial Fibrillation | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 2 (8) | ||

| Sinus tachycardia | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | |||

| Chest pain | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | |||

| Constitutional | |||||

| Insomnia | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | |||

| Fatigue | 6 (32) | 10 (40) | 16 (72) | ||

| Pruritis | 4 (16) | 1 (1) | 5 (20) | ||

| Neurologic and Psychologic | |||||

| Headache | 6 (24) | 1 (4) | 7 (28) | ||

| Dizzyness | 3 (12) | 3 (12) | |||

| Steroid Psychosis | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | |||

| Delirium | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 2 (8) | ||

| Peripheral Neuropathy | 5 (20) | 2 (8) | 7 (28) | ||

| Anxiety | 4 (16) | 4 (16) | |||

| Musculoskeletal | |||||

| Myalgia | 8 (36) | 8 (36) | |||

| Arthralgia | 5 (20) | 4 (16) | 9 (36) | ||

| Generalized weakness | 2 (8) | 2 (8) | |||

| Other | |||||

| Nipple sensitivity | 2 (8) | 2 (8) | |||

| Rash | 4 (16) | 2 (8) | 6 (24) | ||

| Flushing | 2 (8) | 2 (8) | |||

| Blurred vision | 2 (8) | 2 (8) |

Patients were followed for adverse events from the start of conditioning (Day -2) through Day+100 from ASCT. All adverse events were graded by two independent reviewers according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Averse Events version 4.0 (CTCAEv4).

Nearly all patients experienced mild nausea or vomiting (88%), however there were no Grade 3/4 events. Mucositis and gastrointestinal upset were mild in most patients; only two out of twenty-five subjects (8%) experienced Grade 3 mucositis and there was single case of Grade 3 diarrhea (4%). With the exceptions of the Grade 4 atrial fibrillation seen in the instance of neutropenic sepsis, and a Grade 3 hypotension associated with a hypersensitivity reaction to platelet transfusion, there were no other Grade 3 or 4 cardiac events. No cardiac events were directly attributable to the bendamustine infusion. There were no cases of veno-occlusive liver disease.

Thirteen patients (52%) had grade 1 or 2 fever and a causative organism was identified in 6 (24%), including 1 with S. mitis bacteremia, 1 with E. coli bacteremia, 1 with line-related S. haemolyticus infection, 1 with microsporidia enterocolitis, and 1 with rotavirus enterocolitis, all of which resolved with antibiotic therapy or supportive care alone. There was one case of C. dificile colitis. There was no transplant-related mortality.

Response Assessment

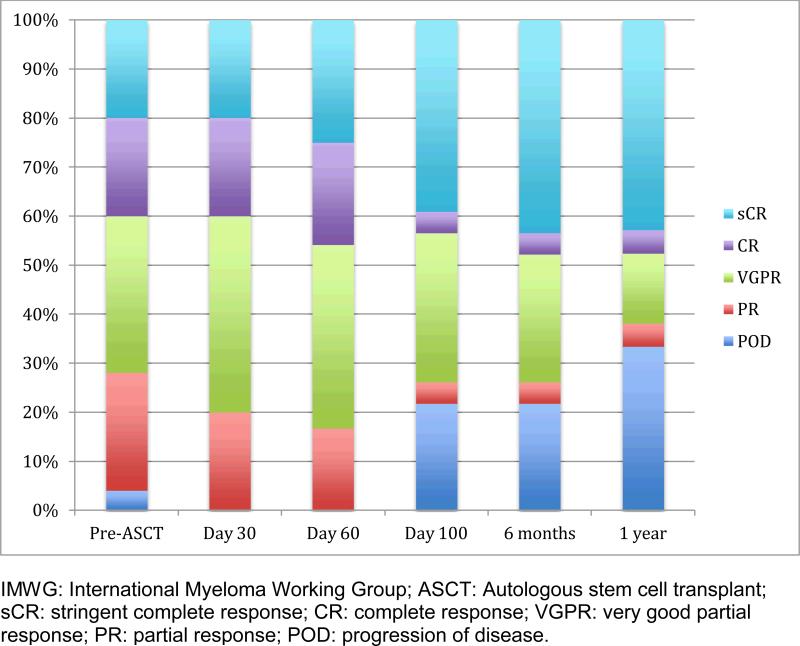

Responses by IMWG criteria to induction therapy prior to transplant and at days 30, 60, 100, 6 months, and 1-year post-ASCT are shown in Figure 1. Prior to transplant, 40% of the patients had achieved CR or better with induction therapy. Following transplant, the CR and better rate improved through one year of follow-up: 40% were in CR or better at day 30; 46% at day 60; 42% at day 100; 47% at day 180, and 48% at 1 year. Overall response rate was 79% at day 100 after ASCT.

Figure 1.

Myeloma Response (IMWG Criteria)

There were five subjects with progression of myeloma detected at day 100, all with high risk prognostic factors. Two progressing patients initially presented with extramedullary myeloma; one subject had ISS Stage III disease with complex karyotypic abnormalities and plasmablastic morphology with a Ki67 immunohistochemical positivity in 19.4% of plasma cells on initial bone marrow biopsy; and the remaining two subjects were heavily pretreated (3 prior lines of therapy) after becoming refractory to both lenalidomide and bortezomib. Two of the patients with early progression of disease were in Cohort 1, and Cohorts 2, 4, 5 had one patient each. Two patients, also with high-risk disease features, had progression of disease after day 100 but prior to 1 year follow-up. One patient in Cohort 2 who progressed had Durie Salmon Stage 3b IgA-kappa myeloma and a Ki67% on initial bone marrow biopsy of 42%. The second patient, who was in Cohort 6, had IgA-lambda myeloma, Durie Salmon Stage IIa, ISS stage 3, with t(14;16) detectable on FISH testing, and a Ki67% on initial bone marrow biopsy of 13%.

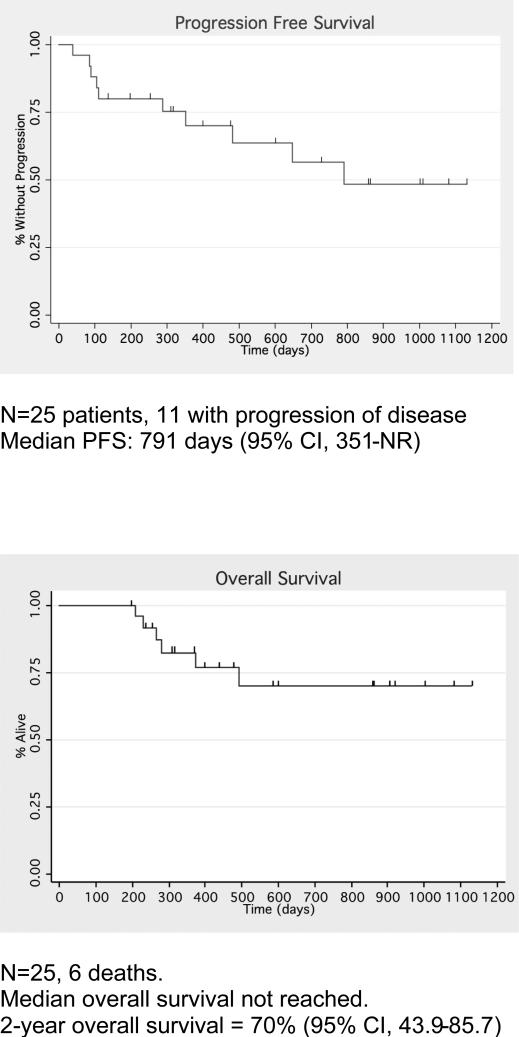

Clinical Outcomes

After a median of 473 days (range 279-1128) of follow up post-ASCT, 10 patients had progressed. Median progression-free survival (PFS) was 791 days (95% CI, 351-NR). (Figure 2). Six patients have died over the course of the study, all from progressive myeloma and resulting complications. All deaths occurred beyond 100 days post-transplant. Median overall survival was not reached. Actuarial 2-year overall survival was 70% (95% CI, 43.9-85.7) (Figure 2). Maintenance therapy was given at the discretion of the referring physician. Seven out of the 20 patients without progression at Day 100 subsequently started maintenance therapy: six with lenalidomide 10-15mg daily and one with weekly bortezomib maintenance. None of the 7 patients who received post-ASCT maintenance had disease progression during the follow-up period.

Figure 2.

Progression-free and Overall survival

A multivariate Cox proportional hazards model evaluated the effect of multiple prognostic patient and tumor characteristics on PFS and OS. The only risk factor with significant impact of risk of progression was the presence of high-risk cytogenetics (HR 4.81, p = 0.025), while no one factor made a significant impact on overall survival.

Discussion

High dose chemotherapy followed by stem cell rescue was shown to be superior to conventional chemotherapy in a number of randomized clinical trials.1 Although several attempts have been made to optimize the conditioning regimen for autologous stem cell transplant in multiple myeloma since the standard MEL200 gained widespread acceptance, no one regimen has thus far shown clear superiority to this standard without adding to toxicity. Yet, there is suggestive evidence that more intense chemotherapy may be useful for prolonging PFS and OS in myeloma. The IFM 9502 randomized study comparing TBI+melphalan 140mg/m2 to melphalan 200 mg/m2 provides compelling evidence that the increased dose of melphalan leads to superior overall survival (45.6% vs. 65% survival at 45-months) despite equivalent treatment-related mortality.1 The IFM 99-04 protocol showed a superior outcome in the tandem MEL200 group in those patients who failed to achieve a VGPR or better after a single transplant.23 Amifostine has been used to safely increase total melphalan dose up to 300mg/m2 in B-cell lymphoma with acceptable toxicities.24 The initial report of a randomized phase I/II study comparing MEL200 vs. MEL280 + amifostine as conditioning for first ASCT in MM demonstrates higher rates of CR and near CR, albeit with more regimen-related gastrointestinal toxicity in the MEL280 arm.25 It remains to be seen whether the higher rate of major response with MEL280+amifostine will translate into longer PFS and OS.

Bendamustine has been shown to overcome resistance to alkylating chemotherapy in lymphoma refractory to alkylating agents.11,26 Bendamustine also has documented activity in multiple myeloma in a number of settings, including combination therapy with novel agents, in refractory disease, and after relapse from prior stem cell transplant.13,16 A recent phase 1/2 study reported favorable results for the substitution of bendamustine in place of BCNU in the BEAM conditioning regimen for relapsed or refractory lymphoma, showing an 81% CR rate at 18 months and a toxicity profile that is not significantly worse compared to BEAM.17

We explored whether the bendamustine could be safely added to a high-dose melphalan regimen in this phase 1 study. Escalating doses of bendamustine were added through six cohorts to split-dose melphalan at 200mg/m2 without encountering a maximum tolerated dose. The choice to split the melphalan into two subsequent daily doses of 100mg/m2 each was done to reduce the risk of synergistic toxicity between the melphalan and bendamustine. A sole dose-limiting toxicity occurred, an episode of sepsis with rapid atrial fibrillation, which was not directly attributable to the use of bendamustine. Toxicities were not significantly different than those expected with MEL200, consisting primarily of mild mucositis, nausea, and fatigue. The historically reported rates of all grades of oral mucositis in subjects receiving high dose melphalanhave varied widely from 40-90%.21,27,28 In a recent study comparing palifermin vs. placebo for use in high dose melphalan therapy the overall incidence of WHO grades 1-4 mucositis in the placebo arm (n = 57) was 75%, with the rate of Grades 3 and 4 mucositis at 19% and 18% respectively.29 In another recent phase 1 study evaluating dose escalation of palifermin in subjects receiving MEL200 conditioning, the rate of grade 3 mucositis was 44%.30 Avivi et al., in a study of mucosal and salivary gland integrity in 25 consecutive subjects treated with MEL200, report an overall oral mucositis rate of 96%.31 In our study, oral mucositis occurred in 92% of subjects, yet the rate of severe mucositis was only 8%. Given this data, bendamustine does not appear to significantly elevate mucositis risk from MEL200. Bendamustine-induced serious cardiotoxicity was not seen and treatment-related mortality was 0% at 100 days post-transplantation. Engraftment kinetics did not significantly differ from those expected after MEL200; there were no cases of prolonged or failed engraftment.

This is a phase 1 study, involving a heterogeneous group of patients with MM presenting for first transplant and was not designed to evaluate regimen efficacy or the added contribution of bendamustine. All patients had received at least one of the novel agents during induction, but a variety of induction regimens were used and approximately 25% had received multiple lines of therapy prior to transplant, thereby obfuscating response and PFS results. It is too early to draw definitive conclusions regarding the efficacy of bendamustine in ASCT for MM, or a dose-response relationship based on this study. We have reported an overall response rate of 80% at day 100 and a ≥CR rate of approximately 45% at 1 year post-ASCT. The median progression free survival of 791 days (26 months) is on par with what is expected with MEL200, as is the overall survival rate of 70% at two years post-transplant. The six subjects who expired on study all died after 100 days post-ASCT of progressive MM. Each patient who died had features delineating particularly aggressive MM, such as high-risk cytogenetics or extramedullary disease. Of all analyzed prognostic factors, only high-risk cytogenetics predicted higher risk of disease progression.

In conclusion, the addition of bendamustine to a high-dose melphalan regimen at a total dose of 225mg/m2 does not increase transplant risk or toxicity in multiple myeloma. This regimen is currently being explored for efficacy in a phase 2 study.

Ackowledgements

The authors would like to thank Drs. Barry Kaplan, Alan Dosik, Bruce Raphael, Jonathan Goldberg, and Stanley Ostrow for patient care and referral.

This work was supported by a Clinical and Translational Science Center grant (CTSC GRANT UL1-RR024996).

Financial Disclosure Statement:

TMM: Celgene: honoraria for speakers bureau activities, advisory board membership, research funding; Onyx Inc: honoraria for speakers bureau activities and research funding; Millenium Inc, Sanofi-Aventis Inc.: honoraria for speakers bureau activities; RN: Celgene Inc., Millenium Inc., Onyx Inc.: honoraria for speakers bureau activities, advisory board membership, research funding; MC: Celgene Inc. Millennium Inc.: honoraria for speakers bureau activities, advisory board membership, research funding; WR, UG, RNP, SM, JG, TS, and KVB have no conflicts of interest to disclose. This is an investigator initiated study that was conducted without any industry financial support.

References

- 1.Attal M, Harousseau JL, Stoppa AM, et al. A prospective, randomized trial of autologous bone marrow transplantation and chemotherapy in multiple myeloma. Intergroupe Francais du Myelome. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:91–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199607113350204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Child JA, Morgan GJ, Davies FE, et al. High-dose chemotherapy with hematopoietic stem-cell rescue for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1875–1883. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moreau P, Avet-Loiseau H, Harousseau JL, Attal M. Current trends in autologous stem-cell transplantation for myeloma in the era of novel therapies. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1898–1906. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.5878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lahuerta JJ, Mateos MV, Martinez-Lopez J, et al. Influence of pre- and post-transplantation responses on outcome of patients with multiple myeloma: sequential improvement of response and achievement of complete response are associated with longer survival. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5775–5782. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.9721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harousseau JL, Attal M, Avet-Loiseau H, et al. Bortezomib plus dexamethasone is superior to vincristine plus doxorubicin plus dexamethasone as induction treatment prior to autologous stem-cell transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: results of the IFM 2005-01 phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4621–4629. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.9158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harousseau JL, Attal M, Avet-Loiseau H. The role of complete response in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2009;114:3139–3146. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-201053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chanan-Khan AA, Giralt S. Importance of Achieving a Complete Response in Multiple Myeloma, and the Impact of Novel Agents. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2612–2624. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barlogie B, Anaissie E, Haessler J, et al. Complete remission sustained 3 years from treatment initiation is a powerful surrogate for extended survival in multiple myeloma. Cancer. 2008;113:355–359. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moreau P, Hullin C, Garban F, et al. Tandem autologous stem cell transplantation in high-risk de novo multiple myeloma: final results of the prospective and randomized IFM 99-04 protocol. Blood. 2006;107:397–403. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lahuerta JJ, Mateos MV, Martinez-Lopez J, et al. Busulfan 12 mg/kg plus melphalan 140 mg/m2 versus melphalan 200 mg/m2 as conditioning regimens for autologous transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients included in the PETHEMA/GEM2000 study. Haematologica. 2010;95:1913–1920. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.028027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leoni LM, Bailey B, Reifert J, et al. Bendamustine (Treanda) displays a distinct pattern of cytotoxicity and unique mechanistic features compared with other alkylating agents. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:309–317. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ponisch W, Mitrou PS, Merkle K, et al. Treatment of bendamustine and prednisone in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma results in superior complete response rate, prolonged time to treatment failure and improved quality of life compared to treatment with melphalan and prednisone--a randomized phase III study of the East German Study Group of Hematology and Oncology (OSHO). J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2006;132:205–212. doi: 10.1007/s00432-005-0074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grey-Davies E, Bosworth JL, Boyd KD, et al. Bendamustine, Thalidomide and Dexamethasone is an effective salvage regimen for advanced stage multiple myeloma. [letter]. Br J Haematol. 2012;156:552–555. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Damaj G, Malard F, Hulin C, et al. Efficacy of bendamustine in relapsed/refractory myeloma patients: results from the French compassionate use program. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53:632–634. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2011.622422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lentzsch S, O'Sullivan A, Kennedy RC, et al. Combination of bendamustine, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (BLD) in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma is feasible and highly effective: results of phase I/II open-label, dose escalation study. Blood. 2012;119:408–4613. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-395715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knop S, Straka C, Haen M, Schwedes R, Hebart H, Einsele H. The efficacy and toxicity of bendamustine in recurrent multiple myeloma after high-dose chemotherapy. Haematologica. 2005;90:1287–1288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Visani G, Malerba L, Stefani PM, et al. BeEAM (bendamustine, etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan) before autologous stem cell transplantation is safe and effective for resistant/relapsed lymphoma patients. Blood. 2011;118:3419–3425. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-351924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rasschaert M, Schrijvers D, Van den Brande J, et al. A phase I study of bendamustine hydrochloride administered once every 3 weeks in patients with solid tumors. Anticancer Drugs. 2007;18:587–595. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e3280149eb1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rajkumar SV, Harousseau JL, Durie B, et al. Consensus recommendations for the uniform reporting of clinical trials: report of the International Myeloma Workshop Consensus Panel 1. Blood. 2011;117:4691–4695. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-299487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mark T, Ounsafi I, Christos P, et al. The Association of Ki67 Percent Positivity and Clinical Outcomes in the Upfront Treatment of Multiple Myeloma.. Haematologica; 13th International Myeloma Workshop; 2011. p. 96. [abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moreau P, Facon T, Attal M, et al. Comparison of 200 mg/m(2) melphalan and 8 Gy total body irradiation plus 140 mg/m(2) melphalan as conditioning regimens for peripheral blood stem cell transplantation in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: final analysis of the Intergroupe Francophone du Myelome 9502 randomized trial. Blood. 2002;99:731–735. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.3.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Desikan KR, Barlogie B, Jagannath S, et al. Comparable engraftment kinetics following peripheral-blood stem-cell infusion mobilized with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor with or without cyclophosphamide in multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1547–1553. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.4.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Attal M, Harousseau JL, Facon T, et al. Single versus double autologous stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2495–2502. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phillips GL, Meisenberg BR, Reece DE, et al. Activity of single-agent melphalan 220-300 mg/m2 with amifostine cytoprotection and autologous hematopoietic stem cell support in non-Hodgkin and Hodgkin lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2004;33:781–787. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bensinger WI, Becker PS, Gooley TA, et al. Randomized Comparison of Melphalan 200 Mg/m2 v. 280 Mg/m2 As a Preparative Regimen for Patients with Multiple Myeloma Undergoing Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation. Blood. 2012;120:2009. [abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leoni LM, Bailey B, Niemeyer CC, et al. In vitro and ex vivo activity of SDX-105 (bendamustine) in drug-resistant lymphoma cells. AACR Meeting Abstracts. 2004:278. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blijlevens N, Schwenkglenks M, Bacon P, et al. Prospective oral mucositis audit: oral mucositis in patients receiving high-dose melphalan or BEAM conditioning chemotherapy--European Blood and Marrow Transplantation Mucositis Advisory Group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1519–1525. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.6028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grazziutti ML, Dong L, Miceli MH, et al. Oral mucositis in myeloma patients undergoing melphalan-based autologous stem cell transplantation: incidence, risk factors and a severity predictive model. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;38:501–506. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blijlevens N, de Chateau M, Krivan G, et al. In a high-dose melphalan setting, palifermin compared with placebo had no effect on oral mucositis or related patient's burden. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012 Dec 17; doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.257. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.257. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abidi MH, Agarwal R, Tageja N, et al. A Phase I Dose-Escalation Trial of High-Dose Melphalan with Palifermin for Cytoprotection Followed by Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation for Patients with Multiple Myeloma with Normal Renal Function. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;19:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Avivi I, Avraham S, Koren-Michowitz M, et al. Oral integrity and salivary profile in myeloma patients undergoing high-dose therapy followed by autologous SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009;43:801–806. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]