Abstract

Study Objectives:

Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep is considered critical to the consolidation of procedural memory – the memory of skills and habits. Many antidepressants strongly suppress REM sleep, however, and procedural memory consolidation has been shown to be impaired in depressed patients on antidepressant therapy. As a result, it is important to determine whether antidepressive therapy can lead to amnestic impairment. We thus investigated the effects of the anticholinergic antidepressant amitriptyline on sleep-dependent memory consolidation.

Design:

Double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, parallel-group study.

Setting:

Sleep laboratory.

Participants:

Twenty-five healthy men (mean age: 26.8 ± 5.6 y).

Interventions:

75 mg amitriptyline versus placebo.

Measurements/Results:

To test memory consolidation, a visual discrimination task, a finger-tapping task, the Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test, and the Rey Auditory-Verbal Learning Test were performed. Sleep was measured using polysomnography. Our findings show that amitriptyline profoundly suppressed REM sleep and impaired perceptual skill learning, but not motor skill or declarative learning.

Conclusions:

Our study is the first to demonstrate that an antidepressant can affect procedural memory consolidation in healthy subjects. Moreover, considering the results of a recent study, in which selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors were shown not to impair procedural memory consolidation, our findings suggest that procedural memory consolidation is not facilitated by the characteristics of REM sleep captured by visual sleep scoring, but rather by the high cholinergic tone associated with REM sleep. Our study contributes to the understanding of potentially undesirable behavioral effects of amitriptyline.

Citation:

Goerke M, Cohrs S, Rodenbeck A, Kunz D. Differential effect of an anticholinergic antidepressant on sleep-dependent memory consolidation. SLEEP 2014;37(5):977-985.

Keywords: amitriptyline, anticholinergic drug, antidepressant, memory consolidation, sleep

INTRODUCTION

Growing evidence suggests that there is a close association between sleep and memory consolidation.1–3 Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep is thought to play a role in the memory consolidation process, particularly with regard to procedural memory—the memory of skills and habits.4–6 Many antidepressants, however, strongly suppress REM sleep,7 and procedural memory consolidation has been shown to be impaired in depressed patients who are undergoing antidepressant therapy.8,9 In light of these findings, it seems reasonable to ask whether antidepressive therapy can lead to amnestic impairment, especially considering that antidepressants have become the most commonly prescribed class of medications in the United States.10

Suppressing REM sleep with the selective serotonin reup-take inhibitor (SSRI) fluvoxamine or the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) reboxetine did not impair overnight consolidation of a REM sleep-dependent procedural memory task (mirror tracing) in healthy young subjects.11 Correspondingly, the SSRI citalopram or the SNRI reboxetine did not affect overnight consolidation of a REM sleep-dependent procedural memory task in depressed patients.12 When interpreting this finding it is important to consider that SSRIs and SNRIs suppress only those characteristics of REM sleep that are captured by visual sleep stage scoring; both classes of compounds allow the high cholinergic brain activity naturally associated with REM sleep to persist. However, the alternation between high levels of acetylcholine during wakefulness and REM sleep and low levels of acetylcholine during slow wave sleep (SWS) are thought to be critical to the memory consolidation process.13–15

In contrast with SSRIs and SNRIs, anticholinergic antidepressants suppress both REM sleep and high cholinergic brain activity, and may thus affect memory consolidation. Indeed, blocking cholinergic transmission with scopolamine during the REM sleep window impaired REM sleep-dependent procedural learning in rats.16 By the same token, enhancing cholinergic tone by administering the acetylcholine esterase inhibitor done-pezil improved procedural memory performance in healthy older humans.17

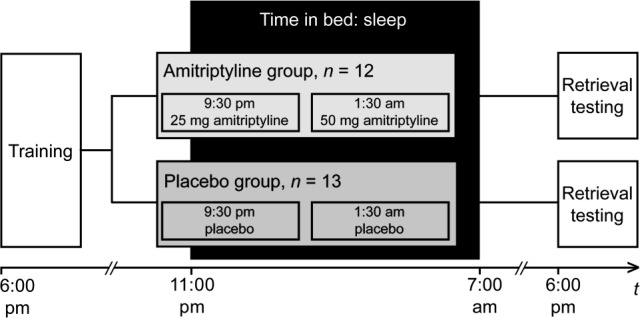

We thus investigated the effects of the anticholinergic anti-depressant amitriptyline in a double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study of 32 healthy young subjects. The subjects performed two procedural memory tasks (a visual discrimination task measuring perceptual skill learning, and a finger-tapping task measuring motor skill learning) and two declarative memory tasks (Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test, Rey Auditory-Verbal Learning Test). After the training session, subjects received either amitriptyline or placebo and spent the night in a sleep laboratory for polysomnographic recording. Retrieval testing took place 24 h after the training session (Figure 1). Whereas improvement on the visual discrimination task is known to depend on posttraining REM sleep,4,5 performance gains on the other tasks performed in our study are thought to be linked to stage 2 sleep or SWS only.18,19 We hypothesized that the amitriptyline and placebo groups would differ in their performance on the REM sleep-dependent visual discrimination task but not on the other REM sleep-independent tasks.

Figure 1.

Experimental procedure. In a double-blind, parallel-group design, we investigated the effects of amitriptyline (n = 12) versus placebo (n = 13) on sleep-dependent memory consolidation. Memory was tested using visual discrimination task, finger tapping, the Rey Auditory-Verbal Learning Test, and the Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test. Medication was administered on two separate occasions after training. Retrieval testing took place 24 h after training.

METHODS

Subjects

Subjects were recruited through bulletin board announcements and a subject recruitment registry maintained by the Institute of Psychology at Humboldt University in Berlin, Germany. Inclusion criteria were (1) male sex, (2) age 18 through 40 y, and (3) ability to communicate effectively in German. Exclusion criteria were (1) shift work within the past 24 mo, (2) any sleep disorder as measured by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index,20 (3) irregular sleep/wake patterns or extreme chronotype as measured by the Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire,21,22 (4) history of any neurologic or psychiatric disorders, (5) regular medication intake within the past 4 w, (6) contraindications for amitriptyline, or (7) an abnormal electrocardiogram (ECG).

Approximately 500 men were screened by telephone interview, but most were excluded because of irregular sleep-wake patterns or extreme chronotype. Thirty-two healthy subjects aged 18 through 39 y with normal or corrected-to-normal vision were included in the study. The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee and the German Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (EudraCT 2007-003546-14). After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained. Prior to the study, all subjects underwent physical and mental health examinations.

Experimental Design and Procedure

The study took place at the sleep laboratory of the Department of Physiology CBF, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, from August 2008 to May 2009. Subjects participated in the study for 11 days. During the first 8 days, they maintained regular sleep schedules as confirmed by sleep logs and actigraphy (Acti-watch, Cambridge Neurotechnology Ltd., Cambridge, United Kingdom). On the ninth day, subjects spent an adaptation night in the sleep laboratory to acclimate them to sleeping under laboratory conditions. The next morning (day 10), subjects left the sleep laboratory and pursued their usual daily activities. They returned to the sleep laboratory that evening for the training session, which started at 18:00 and entailed performing two procedural memory tasks (a visual discrimination task measuring perceptual skill learning and a finger-tapping task measuring motor skill learning) and two declarative memory tasks (the Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test and the Rey Auditory-Verbal Learning Test). Subsequently, subjects were randomized in a double-blind manner to an amitriptyline group or a placebo group, receiving amitriptyline 25 mg at 21:30 and 50 mg at 01:30 or placebo while remaining in bed between 23:00 and 07:00 for polysomnographic recording (the atypical medication regimen was used, since a single dose of amitriptyline in the evening would not have suppressed REM sleep in the later part of the night). The next morning (day 11), subjects were required to fill out a morning protocol23 by answering questions about their current physical and mental state, and about the restorative value of their sleep (i.e., on a five-point scale ranging from “very restorative” to “not restorative at all”). After completing the morning protocol, subjects left the sleep laboratory and proceeded with their daily activities. They were not allowed to nap until they had completed retrieval testing, which was controlled by actigraphy. Retrieval testing took place at 18:00 and was conducted in the same manner as during the training session 24 h earlier (Figure 1).

Active Agent (Amitriptyline), Placebo

Amitriptyline (CT-Arzneimittel GmbH, Berlin, Germany) and placebo (Winthrop-Arzneimittel GmbH, Berlin, Germany) were administered orally. Plasma levels of amitriptyline reach a maximum 1 to 5 h after oral administration, the plasma half-life ranges from 10 to 28 h.24

Randomization, Allocation

Independent pharmacists dispensed either amitriptyline or placebo according to a computer-generated randomization list created using www.randomization.com. The dispensers were numbered consecutively from 1 to 32. Each participant was assigned a number according to the order of the enrollment and received the medication in the corresponding prepacked dispensers. By doing so, subjects, outcome assessors, and data analysts were kept blinded to the allocation. Different investigators analyzed the performance in the memory tasks (MG) and the sleep data (AR).

Memory Tasks

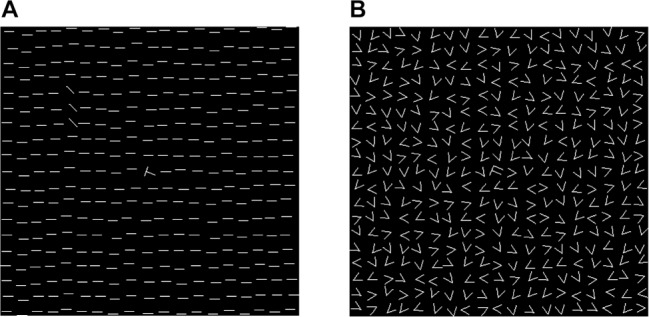

In the visual discrimination task, introduced by Karni and Sagi to measure perceptual skill learning,25 the perception threshold was measured by identifying the orientation of a target texture. The task was presented on a standard personal computer with a 17-inch monitor (75 Hz) using Presentation® 12.1 software (Neurobehavioral Systems Inc., Berkeley, United States). Subjects reacted by pressing keys on a standard German QWERTZ keyboard. They were instructed to fixate on the center of the screen throughout the trial. A centered cross was displayed first. Subjects began the first trial of the task by pressing the space bar, after which a sequence of screens was presented: a blank screen (300 ms), a stimulus pattern (10 ms; Figure 2A), a blank screen (stimulus-to-mask interval of 460–60 ms according to block number), a mask pattern to erase the retinal image of the stimulus (100 ms; Figure 2B), and a response screen (without time limit). Subjects had to answer whether the letter at the center of the stimulus pattern was a “T” or an “L”, and whether the diagonal bars were aligned horizontally or vertically. Immediate auditory feedback was given only for letter identification, which served as a fixation control task, and the only trials ultimately included in the analysis were those in which the letter had been identified correctly. Subjects' ability to discriminate visual textures was assessed using the orientation of the bars. Visual discrimination difficulty was increased systematically by decreasing the stimulus-to-mask interval (stimulus onset asynchrony; SOA). All subjects completed 25 blocks of 50 trials, with one block each at SOAs of 460, 360, 260, and 220 ms, and three blocks each at SOAs of 180, 160, 140, 120, 100, 80, and 60 ms, leading to a total of 1,250 trials in the training session and 1,250 trials in the retrieval testing session. Before the training session, subjects completed a block of 50 trials with an SOA of 460 ms in the presence of the investigator. Performance was measured as the percentage of correct responses at each SOA. The perception threshold was estimated by interpolating the point at which the rate of correct responses was 80%. Improvement in this task was defined as a decrease in the perception threshold between training and retrieval testing. Subjects needed approximately 50 to 75 min to complete the task, depending on their response speed and the time they had for a break between the blocks.

Figure 2.

Stimulus and mask patterns in the visual discrimination task. (A) Stimulus pattern: display was 14° of visual angle in size, containing a field of 19 × 19 horizontal bars with a rotated “T” or “L” at its center. The target texture, which consisted of three horizontally or vertically aligned diagonal bars, varied randomly from trial to trial but always in the same quadrant and at a distance of 3° to 5° of visual angle from the center of the display. (B) Mask pattern: consisted of randomly oriented “V” and a central “T-L” mix.

In the finger-tapping task,19 which tests motor skill learning, the five-element sequence 4-1-3-2-4 had to be tapped on a keyboard with the fingers of the nondominant hand as quickly and as accurately as possible for a period of 30 sec. Subjects performed this trial a total of 12 times with 30-sec breaks between each trial. The numeric sequence was displayed on the screen to reduce working-memory demands, and each key press resulted in a white rectangle being displayed. Every trial was scored for speed (i.e., the number of correctly completed sequences) and accuracy (i.e., the number of errors made). The average scores for speed and accuracy on the last two trials were used as a measure of training performance. During retrieval testing, only two trials were performed, and average scores were generated. Changes in performance were calculated as differences in speed and accuracy between training and retrieval testing. Subjects needed approximately 15 min in the training and 2 min in the retrieval testing to complete this task.

The Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test is a widely used neuropsychological test for evaluating visual declarative memory.26 Subjects were given a card that showed a line drawing (i.e., the so-called stimulus figure) and asked to copy this drawing by hand using a piece of paper and a pencil. When the drawing was completed, both the stimulus figure and the subjects' reproduction of it were removed, and without prior warning the subjects were asked to reproduce the figure again, but from memory. During retrieval testing, subjects had to draw the figure yet again from memory. Memory performance was scored using criteria related to location, accuracy, and organization. Changes in performance were calculated as differences in the scores obtained during training and retrieval testing. Subjects needed approximately 10 min in the training and 5 min in the retrieval testing to complete the task.

The Rey Auditory-Verbal Learning Test is used to assess verbal declarative memory.26 The test consists of 15 unrelated nouns (list A) that are read aloud to the subject at a rate of one noun per sec, followed by a free-recall test. This was done five times (trials 1–5). After completing the fifth trial, subjects were presented with an interference list of 15 words (list B) and subsequently asked to reproduce these words in a free-recall test (trial 6). Accordingly, subjects were asked to recall list A again (trial 7). Retrieval testing consisted of a free-recall test of list A (i.e., without this list having been presented again in the meantime). The difference between the numbers of words remembered in the last training trial (trial 7) and during retrieval testing served as an indicator of a change in performance. To complete this task, subjects needed approximately 20 min in the training and 5 min in the retrieval testing.

Overall, subjects needed approximately 90 to 120 min in the training and 65 to 90 min in the retrieval testing to complete all four memory tasks. Both training and retrieval testing were started with the visual discrimination task to ensure subjects being as fresh as possible. The other three tasks were presented in a counterbalanced order to avoid order effects. The tasks were performed in a silent environment with one subject in each room. For the visual discrimination task, the room was darkened. All memory tasks were administered and evaluated by the same neuropsychologist (MG).

Polysomnographic Recording and Sleep Data Analysis

Sleep was polygraphically recorded for 2 consecutive nights using Sagura Polysomnograph 2000 (Dr. Sagura Royal Medical Systems AG, Mühlheim, Germany). The recordings were performed using standard filter settings and included six electroencephalogram (EEG) channels (F3-A2, F4-A1, C3-A2, C4-A1, O1-A2, O2-A1), two electrooculogram (EOG) channels, a mental electromyograph (EMG) channel, an EMG channel for the tibialis anterior muscle of each leg, and electrocardiography (ECG). In addition, nasal air flow, thoracic and abdominal excursion, peripheral oxygen saturation, and rectal (core body) temperature were measured. Sleep was scored according to the standardized criteria of Rechtschaffen and Kales in 30-sec epochs by two experienced scorers who were blind to the treatment and to the results of the memory tasks.27

For the time in bed (TIB; i.e., time from lights off to lights on), every epoch was scored as (1) wake, (2) non-REM sleep stage 1, 2, 3, or 4, or (3) REM sleep. Time spent in non-REM stages 3 and 4 was defined as SWS. Sleep onset was defined as the first epoch of stage 2 sleep; end of sleep as the first epoch of wake without a subsequent epoch of sleep; sleep latency as the time from lights off to sleep onset; REM latency as the time from sleep onset to the first epoch of REM sleep; sleep period time (SPT) as the time from sleep onset to the end of sleep; total sleep time (TST) as SPT minus wake after sleep onset; percentage of a sleep stage as the percentage of SPT; sleep efficiency as the ratio of TST to TIB; awakenings as the sum of periods with at least one epoch awake during SPT; latency after awakening as min needed to reach sleep stage 2, 3, 4, or REM sleep again after being awakened for medication administration; wake without latency after awakening as min spent awake during SPT minus latency after awakening. Sleep spindles were counted visually in epochs scored as stage 2 sleep from the C4 channel. For sleep spindle detection, we used the following criteria: sleep spindles had to be in the 11-16 Hz frequency range, they had to be at least 0.5 sec in duration, and they had to resemble the typical waxing and waning spindle morphology. All sleep spindles were counted by the same person (MG). Sleep spindle density was calculated as the ratio of the number of sleep spindles to the number of min spent in stage 2 sleep. For a spectral analysis (C4-A1), the fast Fourier transform algorithm was used. Only artifact-free epochs of 30-sec duration were analyzed. The spectral power values of the delta range (differentiated into 0.5-2 Hz and 2-4 Hz), theta range (4-7 Hz), alpha range (8-12 Hz), and sigma range (11-16 Hz) of SPT, non-REM sleep, and REM sleep were used for further analysis.

Statistical Analysis

The primary endpoint was the change in the visual discrimination task's perception threshold, which was assessed before sleep (day 10 at 18:00) and after sleep (day 11 at 18:00). Secondary endpoints included changes in the other memory tasks and the amount of REM sleep during the intervention night. To detect a group difference in the primary endpoint with a one-sided 2.5% significance level and a power of 90%, a sample size of 14 subjects per group was necessary; to account for dropouts we included 16 subjects per group. Data analysis was performed using datasets from 25 subjects, 12 of whom were in the amitriptyline group (mean age: 25.2 ± 3.6 y) and 13 of whom were in the placebo group (mean age: 28.3 ± 6.8 y), because seven subjects were excluded from the analysis: one because of an abnormal electroencephalogram (epileptic potentials), one because of technical difficulties with polysomnography, two because of a mix-up of the drug dispensers, and three because of poor sleep during the posttraining night. Poor posttraining sleep means that the subjects (1) slept less than 80% of their habitual sleep time as measured by sleep logs in the 7 nights before the experiment and (2) had rated their sleep as being “not very restorative” or “not restorative at all” in the morning protocol after the posttraining night. Sleep spindle data are based on 22 subjects (10 amitriptyline, 12 placebo) and spectral power values on 20 subjects (9 amitriptyline, 11 placebo) because of EEG artifacts. Because of right-handedness, data from an uneven number of subjects (11 amitriptyline, 13 placebo) were included in the analysis for the finger-tapping task. Data were analyzed using PASW Statistics 18 (IBM Corp., Armonk, United States). Repeated-measures analyses of variance were carried out to assess whether the two groups differed in their memory performance change from training to the retrieval session. Comparative analyses of the sleep data were performed using independent t tests if the data were normally distributed; otherwise, exact Mann-Whitney U tests were conducted. For correlative analyses, Pearson correlation coefficient (in case of normally distributed data) or Spearman rank correlation coefficient (in case of not normally distributed data) were used. A two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Sleep Data

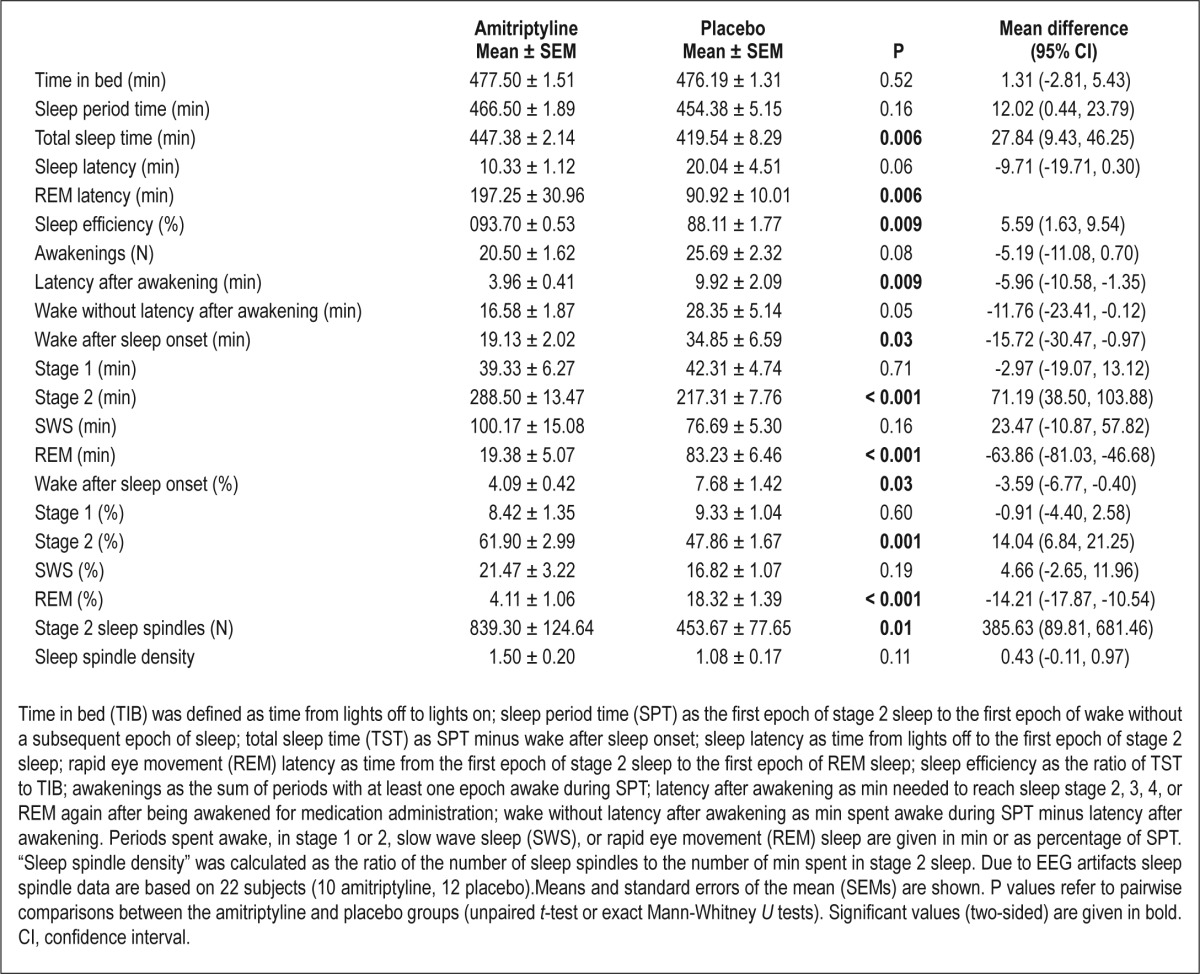

In concordance with the findings of other studies, amitripty-line increased REM sleep latency [t(23) = 3.27, P = 0.006] and markedly reduced the percentage of time spent in REM sleep [t(23) = -8.02, P < 0.001]. Furthermore, subjects in the amitriptyline group spent more time in stage 2 sleep [t(23) = 4.11, P = 0.001]. In contrast, subjects in the placebo group spent significantly more time awake (U = 37, P = 0.03), which led to a lower TST and thus also to a reduced sleep efficiency [t(23) = 3.25, P = 0.006 and t(23) = 3.03, P = 0.009, respectively]. The increased time spent awake in the placebo group can be attributed to subjects needing significantly longer to fall back asleep after being awakened for medication administration (U = 31, P = 0.009). Even if we ignore the length of time that subjects needed to fall back asleep after being awakened, the placebo group spent more time awake, had a greater number of awakenings during the night, and showed higher sleep latency, although these differences failed to reach statistical significance (all P > 0.05). It would thus seem that the placebo group was negatively affected by the nocturnal awakening, whereas the amitriptyline group benefitted from the sedative effect of amitriptyline, resulting in quantitative differences in sleep. The percentage of time spent in stage 1 sleep or in SWS did not differ between the two groups (both P > 0.19; see Table 1 for details).

Table 1.

Sleep parameters after administration of 75 mg amitriptyline or placebo

In the amitriptyline group a significantly higher number of stage 2 sleep spindles was found than in the placebo group [t(20) = 2.72, P = 0.01]. This is not surprising because, as shown previously, subjects in the amitriptyline group spent more time in stage 2 sleep and the number of stage 2 sleep spindles was positively correlated with the time spent in stage 2 sleep (r = 0.53, P = 0.01). However, sleep spindle density did not differ between subjects who received amitriptyline and subjects who received placebo (P = 0.11; see Table 1 for details).

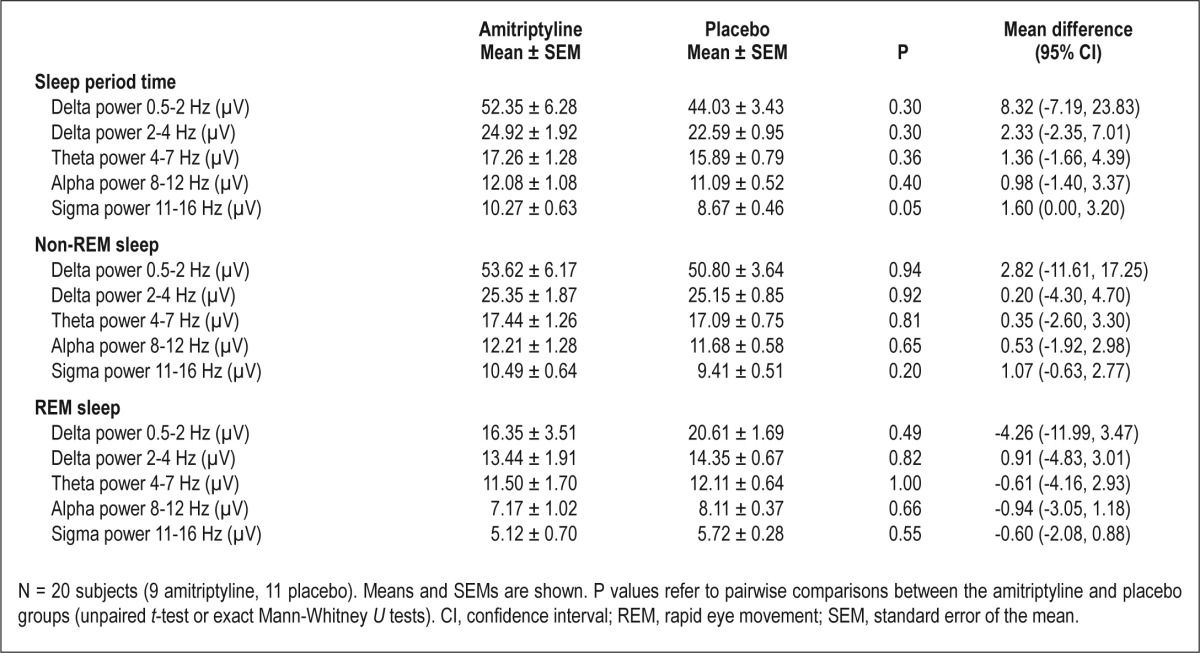

The spectral power values of the delta range, theta range, alpha range, and sigma range of SPT, non-REM sleep, and REM sleep did not differ significantly between the two groups (all P > 0.05; see Table 2 for details). Spectral power value of the delta range of SPT and non-REM sleep was positively correlated with the time spent in SWS [0.5-2 Hz range of SPT: r(18) = 0.79, P < 0.001; 2-4 Hz range of SPT: r(18) = 0.70, P = 0.001; 0.5-2 Hz range of non-REM sleep: r(18) = 0.76, P < 0.001; 2-4 Hz range of non-REM sleep: r(18) = 0.64, P = 0.002]. Spectral power value of the sigma range of SPT was positively correlated with the time spent in stage 2 sleep [r(18) = 0.50, P = 0.02] and the number of stage 2 sleep spindles (r(18) = 0.52, P = 0.02].

Table 2.

Spectral power values after administration of 75 mg amitriptyline or placebo

Memory Performance

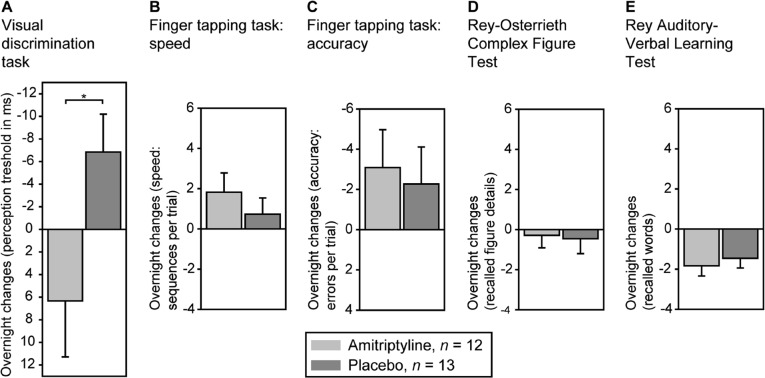

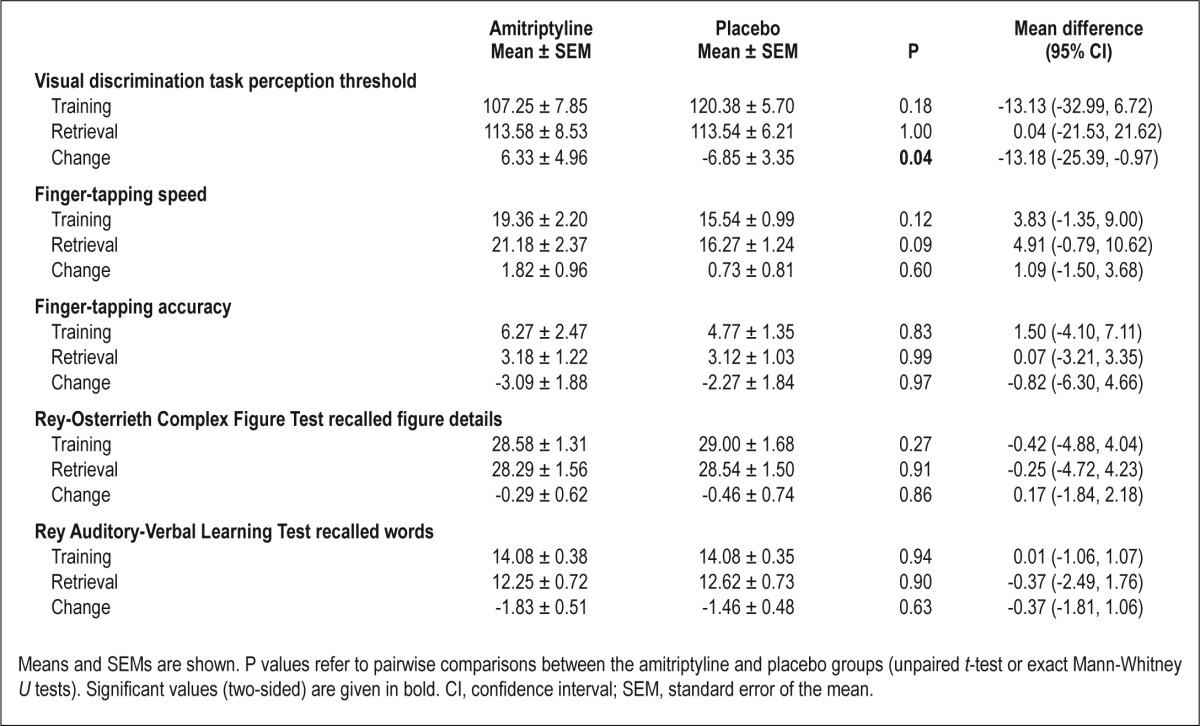

Analysis of variance showed a significant interaction effect between performance on the visual discrimination task and treatment [F(1, 23) = 4.99, P = 0.04]. Performance decreased under amitriptyline (i.e., the perception threshold increased from training to retrieval) and improved under placebo (Figure 3A). On the finger-tapping task, the amitriptyline group showed larger gains in the number of correctly tapped sequences (Figure 3B) and a greater reduction in error rates (Figure 3C); interaction effects between performance and treatment, however, failed to reach statistical significance (both P > 0.39). On the two declarative memory tasks, overnight changes in performance in both groups were comparable (Figure 3, D and E; Table 3). Performance during training did not differ significantly between the two groups on any of the memory tests (all P > 0.12).

Figure 3.

Main results. (A) Analysis of variance revealed a significant interaction between performance in the visual discrimination task and treatment (amitriptyline vs. placebo; *P = 0.04). Performance decreased in the amitriptyline group but improved in the placebo group. In contrast, no significant differences were observed in the performance of the two groups on (B and C) the finger-tapping task (D), the Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test, or (E) the Rey Auditory-Verbal Learning Test. Means and standard errors of the mean are shown.

Table 3.

Memory performance during training and retrieval testing 24 h later

Memory Performance and Sleep

There was no significant correlation observed between the overnight change in visual discrimination task performance and the time spent in REM sleep (P = 0.21). Because overnight improvement in the visual discrimination task was shown before to benefit from a multistep process containing of both REM sleep and REM sleep-preceding SWS,5,28 partial correlations controlled for REM sleep-preceding SWS were carried out. However, we found neither a significant correlation between the overnight change in visual discrimination task performance and the amount of REM sleep controlled for the amount of SWS, nor a significant correlation between the overnight change in visual discrimination task performance and the amount of REM sleep in the second half of the night controlled for the amount of SWS in the first half of the night, nor a significant correlation between the overnight change in visual discrimination task performance and the amount of REM sleep in the last quarter of the night controlled for the amount of SWS in the first quarter of the night (all P > 0.51). Moreover, there was no significant correlation observed between the overnight change in visual discrimination task performance and REM spectral power of any range (all P > 0.11).

On the finger-tapping task, no significant correlation between overnight change in the number of correctly tapped sequences or overnight change in error rates and time spent in stage 2 sleep, the number of stage 2 sleep spindles, sleep spindle density, or non-REM sigma power was found (all P > 0.25).

In addition, we repeated all analyses within the placebo group. As it was shown within all subjects, no significant correlation was observed (all P > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to show that the tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline impairs REM sleep-dependent procedural memory consolidation in healthy young subjects. This impairment cannot be attributed to a hangover effect during retrieval testing because REM sleep-independent procedural and declarative memory consolidation were unaffected. Our findings support the hypothesis that REM sleep-dependent procedural memory consolidation is impaired by suppressing REM sleep with an anticholinergic antidepressant, but not by doing so with an SSRI or SNRI. It would thus seem that REM sleep-dependent procedural memory consolidation is not facilitated by the characteristics of REM sleep captured by visual sleep stage scoring, but rather by the high cholinergic tone associated with REM sleep. The notion that intact cholinergic transmission is a prerequisite for memory consolidation during REM sleep is consistent with recent findings: Blocking cholinergic transmission with scopolamine during the REM sleep window impaired REM sleep-dependent procedural learning in rats.16 Similarly, cholinergic stimulation with an acetylcholine esterase inhibitor in another study improved REM sleep-dependent procedural memory consolidation in healthy older adults.17

Furthermore, one study showed improvements in REM sleep-independent finger-tapping accuracy after REM sleep was suppressed with the SSRI fluvoxamine or the SNRI reboxetine.11 Here, accuracy gains were associated to fast (> 13 Hz) sleep spindles. However, we neither found a significant improvement in finger-tapping accuracy after administration of amitriptyline, nor did we find an association between the performance change and the number of stage 2 sleep spindles or sleep spindle density. These diverging findings may be attributed to differences in sleep spindle detection: Although in our study spindles were counted visually in epochs scored as stage 2 sleep, Rasch and colleagues11 applied an automatic sleep spindle detection procedure which counted sleep spindles, differentiated into slow and fast sleep spindles, in epochs scored as non-REM sleep. Another explanation could be that different types of antidepressants could have different effects on finger-tapping performance. Considering that the receptor profile of amitriptyline has several affinities (i.e., in addition to a strong affinity for cholinergic receptors, there are also affinities for serotonin and norepinephrine receptors), the lack of a significant accuracy gain after amitriptyline in our study may reflect an interaction between the motor skill impairment resulting from the anticholinergic effect of amitriptyline and the motor skill enhancement resulting from this agent's action on serotonin and norepinephrine receptors.

Amitriptyline did not affect REM sleep-independent declarative memory consolidation in our study. This is in line with the finding that blocking muscarinic and nicotinic cholinergic receptors (or muscarinic cholinergic receptors alone) has no effect on declarative memory consolidation in healthy subjects.29,30 Our finding that the anticholinergic antidepressant amitriptyline does not impair declarative memory consolidation is important considering that a recent study has suggested that depression may double the risk of developing Alzheimer disease31 and that Alzheimer disease has been associated with cholinergic deficiency32 and a decline in memory function, particularly in declarative memory. However, because sleep disturbances seem to stress the role of REM sleep in sleep-dependent declarative memory consolidation33,34 and depression is often accompanied by sleep disturbances, an effect of amitriptyline on declarative memory consolidation in depressive patients could be conceivable.

Although amitriptyline dramatically reduced the amount of REM sleep and increased the amount of stage 2 sleep and thereby the number of stage 2 sleep spindles compared with placebo, no treatment effect concerning spectral power values were found. Overnight changes in the memory tasks, however, did not correlate with any of the sleep parameters in our study. This lack of associations could probably be attributed to an amitriptyline effect. Because amitriptyline has a receptor profile with several affinities, we cannot exclude interaction effects on various sleep parameters.

Our study has several limitations. First, our subjects were awakened in order to receive their second dose of amitriptyline or placebo. Although neither SWS nor REM sleep awakenings have been shown to affect sleep-dependent memory consolidation,35 we cannot exclude the possibility that waking subjects during stage 2 sleep may have had an effect on our findings. Second, whereas the amitriptyline group benefited from the sedative effect of amitriptyline, the placebo group was negatively affected by the nocturnal awakening, leading to a higher amount of time awake, lower TST, and reduced sleep efficiency likely because of the laboratory condition. As a result, the improvement in the memory tasks seen in the placebo group during retrieval testing might have been higher in the absence of a nocturnal awakening. Third, amitriptyline was administered for only 1 night. Although studies that observed sleep during a 5-w treatment of amitripty-line found REM sleep suppression to persist,36,37 sleep architecture and thus memory consolidation may differ with long-term antidepressant use. Fourth, because retrieval testing took part 16.5 h after the last administration of amitriptyline, due to the long half-life of amitriptyline (up to 28 h) it is possible that the drug was still active during retrieval testing. So it remains unclear whether amitriptyline and its possibly continuously existing anticholinergic effect might have affected performance during retrieval testing. The cholinergic system has been implicated in modulating attention and memory processes. Because the amitriptyline group performed worse than the placebo group during retrieval testing only in the visual discrimination task, a general negative anticholinergic effect on attention, which should have affected performance in all tasks in a similar manner, seems to be unlikely. In contrast, according to memory processes, acetylcholine is thought to play a role particularly in perceptual skill learning. Therefore, by comparing the amitriptyline group's performance in the different memory tasks we cannot rule out a negative anticholinergic effect on performance during memory retrieval. To differentiate anticholinergic effects on the consolidation from those on the retrieval process, a second retrieval testing 24 h after the first retrieval testing should have been included. In addition, sleep in the night between the retrieval testings should have been recorded to control for a REM sleep rebound. Further research should take this into account, because studies on the effects of cholinergic modulation in perceptual skill memory that clearly distinguish memory stages are lacking. Furthermore, given that acetylcholine plays a role in perceptual skill memory irrespective of whether the modality is visual,38,39 auditory,40 or olfactory,41 possible effects of anticholinergic medication might have a great importance for everyday life; therefore, further research is urgently needed. Fifth, to detect a group difference in the overnight change in the visual discrimination task's perception threshold with a one-sided 2.5% significance level (which is similar to a two-sided 5% significance level) and a power of 90%, a sample size of 14 subjects per group was necessary. Because there were subjects who had to be excluded, data analysis was performed using datasets from 12 subjects in the amitriptyline group and 13 subjects in the placebo group only and, unfortunately, because it was a clinical trial we were not able to add the missing subjects. Despite this fact, we found a significant group difference in the overnight change in the visual discrimination task's perception threshold. Furthermore, we checked the effect size (Cohen's d = 0.89) as well as the confidence intervals, neither of which point to a problem of the current study being underpowered. However, because the group difference can be mainly attributed to a numeric (but nonsignificant) difference in the visual discrimination task's perception threshold assessed during the training session, our results need to be confirmed by further studies with bigger sample sizes. Sixth, because our subjects were healthy and young, results cannot be generalized to depressed patients, particularly to those belonging to different age groups. Whereas one study has shown that REM sleep-independent procedural memory consolidation was not affected by an SSRI or an SNRI in healthy young subjects,11 it has been found to be impaired in depressive patients on various antidepressive agents.8,9 Moreover, memory consolidation has been found to be preserved in young patients but was severely impaired in older ones.9,12 Further research on the possible side effects of antidepressants should thus take into account different age groups. Finally, because only men were included in our study to avoid an effect of the menstrual cycle on sleep and sleep-dependent memory consolidation,42 results cannot easily be generalized to woman.

In conclusion, our results show that the anticholinergic anti-depressant amitriptyline impaired the REM sleep-dependent procedural memory consolidation in healthy young subjects, whereas the REM sleep-independent procedural and declarative memory consolidation remained unaffected. This is the first study to show that an anticholinergic antidepressant can have this negative effect, at least in healthy men. Because antidepressants are the most commonly prescribed class of medication in the United States and depression is associated with a twofold risk of developing dementia, prospective studies are needed to determine whether antidepressants have a negative impact on various memory systems and, if so, under which circumstances.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. Dr. Kunz has received lecture fees from AIT, Astra Zeneca, BMS, Knauf, Lundbeck, Medical Tribune, PBV, Schwarz, Servier, Sanofi-Synthelabo, Trilux, and Zumtobel; he has received advisory panel payments from Astra Zeneca, BMS, European Space Agency, European Commission, Lundbeck, Philips Respironics, and Pfizer; and received research support from Acte-lion, DIN, Fraunhofer, Knauf, MSD, Osram and Uwe Braun GmbH. Dr. Cohrs has received lecture fees from Astra Zeneca, Servier, GSK, Sanofi-Aventis, and Lundbeck. The other authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest. Drug use: Amitriptyline was used in an investigational manner (ClinicalTrials.gov: The Influence of Amitriptyline on Learning in a Visual Discrimination Task; http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01566825?term=NCT01566825; NCT01566825.). Please note that further information about the clinical trial (CONSORT statement) is provided as supplemental material.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Jan Born and his research group for providing the software for running the visual discrimination task, and Matthew Gaskins for editing this manuscript.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

CONSORT 2010 checklist of information to include when reporting a randomized trial*

CONSORT 2010 Flow Diagram.

REFERENCES

- 1.Maquet P. The role of sleep in learning and memory. Science. 2001;294:1048–52. doi: 10.1126/science.1062856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Born J, Rasch B, Gais S. Sleep to remember. Neuroscientist. 2006;12:410–24. doi: 10.1177/1073858406292647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diekelmann S, Born J. The memory function of sleep. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:114–26. doi: 10.1038/nrn2762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karni A, Tanne D, Rubenstein BS, Askenasy JJ, Sagi D. Dependence on REM sleep of overnight improvement of a perceptual skill. Science. 1994;265:679–82. doi: 10.1126/science.8036518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stickgold R, Whidbee D, Schirmer B, Patel V, Hobson JA. Visual discrimination task improvement: A multi-step process occurring during sleep. J Cogn Neurosci. 2000;12:246–54. doi: 10.1162/089892900562075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mednick S, Nakayama K, Stickgold R. Sleep-dependent learning: a nap is as good as a night. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:697–8. doi: 10.1038/nn1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mayers AG, Baldwin DS. Antidepressants and their effect on sleep. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2005;20:533–59. doi: 10.1002/hup.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Genzel L, Ali E, Dresler M, Steiger A, Tesfaye M. Sleep-dependent memory consolidation of a new task is inhibited in psychiatric patients. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45:555–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dresler M, Kluge M, Genzel L, Schüssler P, Steiger A. Impaired off-line memory consolidation in depression. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;20:553–61. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olfson M, Marcus SC. National patterns in antidepressant medication treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:848–56. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rasch B, Pommer J, Diekelmann S, Born J. Pharmacological REM sleep suppression paradoxically improves rather than impairs skill memory. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:396–7. doi: 10.1038/nn.2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Göder R, Seeck-Hirschner M, Stingele K, et al. Sleep and cognition at baseline and the effects of REM sleep diminution after 1 week of antidepressive treatment in patients with depression. J Sleep Res. 2011;20:544–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2011.00914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buzsaki G. The hippocampo-neocortical dialogue. Cereb Cortex. 1996;6:81–92. doi: 10.1093/cercor/6.2.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buzsaki G. Memory consolidation during sleep: a neurophysiological perspective. J Sleep Res. 1998;7:17–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.7.s1.3.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hasselmo ME. Neuromodulation: acetylcholine and memory consolidation. Trends Cogn Sci. 1999;3:351–9. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(99)01365-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Legault G, Smith CT, Beninger RJ. Scopolamine during the paradoxical sleep window impairs radial arm maze learning in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;79:715–21. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hornung OP, Regen F, Danker-Hopfe H, Schredl M, Heuser I. The relationship between REM sleep and memory consolidation in old age and effects of cholinergic medication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:750–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Plihal W, Born J. Effects of early and late nocturnal sleep on declarative and procedural memory. J Cogn Neurosci. 1997;9:534–47. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1997.9.4.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walker MP, Brakefield T, Morgan A, Hobson JA, Stickgold R. Practice with sleep makes perfect: sleep-dependent motor skill learning. Neuron. 2002;35:205–11. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00746-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horne JA, Ostberg O. A self-assessment questionnaire to determine morningness-eveningness in human circadian rhythms. Int J Chronobiol. 1976;4:97–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Griefahn B, Künemund C, Brode P, Mehnert P. Zur Validität der deutschen Übersetzung des Morningness-Eveningness-Questionnaires von Horne und Östberg. Somnologie. 2001;5:71–80. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoffmann RM, Müller T, Hajak G, Cassel W. Abend-Morgenprotokolle in Schlafforschung und Schlafmedizin - Ein Standardinstrument für den deutschsprachigen Raum. Somnologie. 1997;1:103–9. [Google Scholar]

- 24.CT-Arzneimittel GmbH. Berlin: CT-Arzneimittel GmbH; 2004. CT-Arzneimittel Amitriptylin-CT 25 mg/-75 mg Fachinformation (Zusammenfassung der Merkmale des Arzneimittels/ SPC) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karni A, Sagi D. Where practice makes perfect in texture discrimination: evidence for primary visual cortex plasticity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:4966–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.11.4966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spreen O, Strauss E. A compendium of neuropsychological tests. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rechtschaffen A, Kales A. A manual of standardized terminology, techniques and scoring system for sleep stages of human subjects. Washington: US Government Printing Office; 1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gais S, Plihal W, Wagner U, Born J. Early sleep triggers memory for early visual discrimination skills. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:1335–9. doi: 10.1038/81881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rasch B, Gais S, Born J. Impaired off-line consolidation of motor memories after combined blockade of cholinergic receptors during REM sleep-rich sleep. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:1843–53. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nissen C, Power AE, Nofzinger EA, et al. M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor agonism alters sleep without affecting memory consolidation. J Cogn Neurosci. 2006;18:1799–807. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2006.18.11.1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saczynski JS, Beiser A, Seshadri S, Auerbach S, Wolf PA, Au R. Depressive symptoms and risk of dementia: the Framingham Heart Study. Neurology. 2010;75:35–41. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e62138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whitehouse PJ, Price DL, Struble RG, Clark AW, Coyle JT, Delon MR. Alzheimer's disease and senile dementia: loss of neurons in the basal forebrain. Science. 1982;215:1237–9. doi: 10.1126/science.7058341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goerke M, Cohrs S, Rodenbeck A, Grittner U, Sommer W, Kunz D. Declarative memory consolidation during the first night in a sleep lab: The role of REM sleep and cortisol. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38:1102–11. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Backhaus J, Junghanns K, Born J, Hohaus K, Faasch F, Hohagen F. Impaired declarative memory consolidation during sleep in patients with primary insomnia: Influence of sleep architecture and nocturnal cortisol release. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:1324–30. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Genzel L, Dresler M, Wehrle R, Grozinger M, Steiger A. Slow wave sleep and REM sleep awakenings do not affect sleep dependent memory consolidation. Sleep. 2009;32:302–10. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.3.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gillin JC, Wyatt RJ, Fram D, Snyder F. The relationship between changes in REM sleep and clinical improvement in depressed patients treated with amitriptyline. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1978;59:267–72. doi: 10.1007/BF00426633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Staner L, Kerkhofs M, Detroux D, Leyman S, Linkowski P, Mendlewicz J. Acute, subchronic and withdrawal sleep EEG changes during treatment with paroxetine and amitriptyline: a double-blind randomized trial in major depression. Sleep. 1995;18:470–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rokem A, Silver MA. Cholinergic enhancement augments magnitude and specificity of visual perceptual learning in healthy humans. Curr Biol. 2010;20:1723–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beer AL, Vartak D, Greenlee MW. Nicotine facilitates memory consolidation in perceptual learning. Neuropharmacology. 2013;64:443–51. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Butt AE, Chavez CM, Flesher MM, et al. Association learning-dependent increases in acetylcholine release in the rat auditory cortex during auditory classical conditioning. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2009;92:400–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilson DA, Fletcher ML, Sullivan RM. Acetylcholine and olfactory perceptual learning. Learn Mem. 2004;11:28–34. doi: 10.1101/lm.66404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Genzel L, Kiefer T, Renner L, et al. Sex and modulatory menstrual cycle effects on sleep related memory consolidation. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37:987–98. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

CONSORT 2010 checklist of information to include when reporting a randomized trial*

CONSORT 2010 Flow Diagram.