Abstract

BACKGROUND

Mortality rates from kidney cancer have continued to rise despite increases in the detection of smaller renal tumors and rates of renal operations. To explore factors associated with this treatment-outcome discrepancy, we evaluated how changes in tumor size have affected disease progression in patients following nephrectomy for localized kidney cancer. Furthermore, we sought to identify factors that are associated with disease progression and overall patient survival following resection for localized kidney cancer.

METHODS

We identified 1,618 patients with localized kidney cancer treated by nephrectomy at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) from 1989 to 2004. Patients were categorized by year of operation: 1989–1992, 1993–1996, 1997–2000, and 2001–2004. Tumor size was classified according to the following strata: <2 cm, 2 to 4 cm, 4 to 7 cm, and >7 cm. Progression was defined as the development of local recurrence or distant metastases. Five-year progression-free survival (PFS) was calculated for patients in each tumor size strata, according to year of operation, using the Kaplan-Meier method. Patient, tumor, and surgery related characteristics associated with PFS and overall survival (OS) were explored using univariable analysis and all significant variables were retained in a multivariable Cox regression analysis.

RESULTS

Overall, the number of nephrectomies increased for all tumor size categories from 1989 to 2004. A tumor size migration was evident during this period, as the proportion of patients with tumors <2 cm and 2 to 4 cm increased while those with tumors >7 cm decreased. 179 patients (11%) developed disease progression after nephrectomy. Local recurrence occurred in 16 (1%) and distant metastases in 163 (10%). When 5-year PFS was calculated for each tumor size strata according to 4-year cohorts, trends in PFS did not improve nor differ significantly over time. Compared to historical cohorts, patients in more contemporary cohorts were more likely to undergo partial, as opposed to radical, nephrectomy and less likely to have a concomitant lymph node dissection and adrenalectomy. Multivariable analysis showed that pathologic stage and tumor grade were associated with disease progression while patient age and tumor stage were associated with overall patient survival.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite an increasing number of nephrectomies and a size migration towards smaller tumors, trends in 5-year PFS and OS did not improve nor differ significantly over time. These findings require further research to identify causative mechanisms and argue for a re-evaluation of the current treatment paradigm of surgically removing solid renal masses upon initial detection and consideration of active surveillance for patients with select renal tumors.

Kidney cancer is the third most common genitourinary tumor, with 51,190 new cases and 12,890 deaths estimated for 2007.1 Incidence rates have increased steadily since the 1970’s, owing in part to the widespread use of noninvasive imaging modalities, such as ultrasonography (US), computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).2, 3

Single center, multi-institutional, and national incidence trends have noted a higher proportion of kidney cancers diagnosed at smaller tumor sizes and earlier, pre-symptomatic stages.2, 4–8 Furthermore, the rising incidence of kidney cancer has been found to be largely attributable to an increase in small kidney tumors.9 Despite these findings and the concurrent increases in rates of renal operations for small renal masses that are presumably curable, kidney cancer mortality rates have paradoxically continued to rise.9

To explore factors associated with this treatment-outcome discrepancy, we sought to describe the changes in tumor size of localized kidney cancers presenting to our institution from 1989 to 2004, to evaluate the impact of size migration on progression-free survival (PFS) trends following nephrectomy for localized disease, to describe trends in surgery-related and tumor-related characteristics, and to identify patient demographic and clinical characteristics associated with disease progression and overall survival.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and Variables

From January 1989 to December 2004, we identified 1,618 patients undergoing radical (n=1,050) or partial (n=568) nephrectomy for clinically localized kidney cancer at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC).

Pathologic tumor size was classified according to the following strata: <2 cm, 2 to 4 cm, 4 to 7 cm, and >7 cm. Patients were categorized by year of operation according to the following 4-year cohorts: 1989–1992, 1993–1996, 1997–2000, and 2001–2004. Tumor stage was determined according to the 2002 American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system.10 All pathologic subtypes of renal cell carcinoma were included. Fuhrman tumor grade was defined as the worst grade within a tumor. Data on patient age, gender, race, tumor laterality, histology, year of surgery, type of operation, surgery approach, whether or not a concomitant adrenalectomy was performed and disease progression status were available for all 1,618 patients. Data on surgical margins and whether or not a concomitant lymph node dissection was performed at the time of nephrectomy was unavailable in 24 and 14 patients, respectively, from the 1989–1992 cohort. Progression was defined as the development of local recurrence or distant metastases. Patients with bilateral masses at diagnosis were excluded. Metachronous disease in the contralateral kidney was not considered a recurrence.

Statistical analysis

Summary statistics were described using frequencies and proportions for categorical variables. We used χ2 tests where appropriate to examine whether select demographic or clinical patient characteristics were associated with tumor size. PFS was defined as the time from nephrectomy to disease progression. OS was defined as the time from nephrectomy to the date of death. Patients were censored at the date of the last follow-up if they were free of disease (when determining PFS) or if they were alive (when determining OS). The median follow-up time after surgery was 50.4 months (IQR 61.3 months). Five-year PFS rates were calculated for patients in each tumor size strata, according to the year of surgery, using the Kaplan-Meier method and trends in PFS were compared using the log-rank test. Patient, tumor, and surgery related characteristics associated with PFS and OS were explored first using univariable analysis and all significant variables were retained subsequently in a multivariable Cox regression analysis. P-values were 2-sided and considered statistically significant if < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 8.2 (Stata Corp., College Station, Texas, USA).

RESULTS

Patient, Tumor, and Surgery Related Characteristics at Time of Nephrectomy

Demographic and clinical characteristics of cohort members are shown in Table 1, as a function of tumor size. There were no significant differences among tumor size groups with respect to patient age or tumor laterality. Across all tumor size strata, over 85% of patients were white (p=0.019) and the majority (66% to 73%) had clear cell tumor histology (p=0.002). Larger tumor size was associated with higher Fuhrman grade.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of 1,618 patients with localized kidney cancer undergoing nephrectomy at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center from 1989 to 2004, according to tumor size

| Tumor size |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <2 cm (n=167) |

2 to 4 cm (n=632) |

>4 to 7 cm (n=453) |

>7 cm (n=366) |

||

| % of patients | % of patients | % of patients | % of patients | p-value | |

| Patient related | |||||

| Mean age ± SD (years) | 60.4 ± 12.2 | 61.3 ± 11.8 | 62.1 ± 12.2 | 61.3 ± 12.5 | |

| Gender | 0.548 | ||||

| Male | 60.5 | 64.7 | 64.5 | 66.9 | |

| Female | 39.5 | 35.3 | 35.5 | 33.1 | |

| Race | 0.019 | ||||

| White | 89.8 | 90.0 | 90.0 | 85.3 | |

| Black | 5.4 | 6.0 | 4.9 | 5.2 | |

| Other | 4.8 | 4.0 | 5.1 | 9.5 | |

| Tumor related | |||||

| Tumor laterality | 0.988 | ||||

| Right | 49.1 | 47.6 | 47.9 | 47.5 | |

| Left | 50.9 | 52.4 | 52.1 | 52.5 | |

| Tumor stage | <0.0001 | ||||

| T1 | 92.7 | 89.8 | 74.1 | 0 | |

| T2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 44.8 | |

| T3 | 7.3 | 10.1 | 25.9 | 52.6 | |

| T4 | 0 | 0.1 | 0 | 2.6 | |

| Tumor grade | <0.0001 | ||||

| 1 | 19.4 | 8.9 | 8.5 | 2.5 | |

| 2 | 65.3 | 76.0 | 65.5 | 46.6 | |

| 3 | 15.3 | 14.1 | 24.4 | 39.0 | |

| 4 | 0 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 11.9 | |

| Tumor histology | 0.002 | ||||

| Clear cell | 71.9 | 66.4 | 72.9 | 70.0 | |

| Papillary | 17.3 | 20.0 | 15.5 | 9.5 | |

| Chromophobe | 8.4 | 10.0 | 9.3 | 15.3 | |

| Unclassified | 2.4 | 3.4 | 2.1 | 4.9 | |

| Collecting duct | 0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | |

| Surgery related | |||||

| Surgery year | <0.0001 | ||||

| 1989–1992 | 4.8 | 9.7 | 12.8 | 17.0 | |

| 1993–1996 | 13.8 | 16.5 | 17.4 | 24.3 | |

| 1997–2000 | 28.7 | 28.1 | 31.4 | 25.4 | |

| 2001–2004 | 52.7 | 45.7 | 38.4 | 33.3 | |

| Type of operation | |||||

| Radical Nephrectomy | 18.0 | 45.1 | 83.4 | 97.5 | <0.0001 |

| Partial Nephrectomy | 82.0 | 54.9 | 16.6 | 2.5 | |

| Surgery approach | <0.0001 | ||||

| Open Nephrectomy | 95.8 | 97.2 | 95.6 | 97.5 | |

| Laparoscopic Nephrectomy | 4.2 | 2.8 | 4.4 | 2.5 | |

| Surgical margin status | 0.004 | ||||

| Negative | 94.6 | 91.0 | 95.5 | 89.1 | |

| Positive | 4.2 | 7.4 | 2.7 | 9.3 | |

| Not available | 1.2 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 1.6 | |

| Adrenalectomy | <0.0001 | ||||

| Yes | 10.8 | 26.4 | 50.3 | 75.4 | |

| No | 89.2 | 73.6 | 49.7 | 24.6 | |

| Lymph node dissection | <0.0001 | ||||

| Yes | 7.8 | 16.0 | 34.2 | 59.6 | |

| No | 91.6 | 82.9 | 64.9 | 39.6 | |

| Not available | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.8 | |

Patients with smaller tumors were more likely to undergo partial nephrectomy than those with larger tumors. For instance, among patients with tumors <2 cm and tumors between 2 to 4 cm, 82% and 55%, respectively, underwent a partial nephrectomy (p<0.0001). Patients with larger tumors were more likely to undergo concomitant adrenalectomy and/or lymph node dissection. For example, for those with tumors < 2 cm, 11% and 8% had an adrenalectomy and lymph node dissection, respectively, as compared to 75% and 60% of patients with tumors > 7 cm who had an adrenalectomy (p<0.0001) and lymph node dissection (p<0.0001), respectively.

Trends in Tumor and Surgery Related Characteristics

Tumor Size and Tumor Stage Distributions

Figures 1a and 1b demonstrate the changes in tumor size and tumor stage distributions, respectively, of localized kidney cancers from 1989 to 2004. A tumor size migration was evident during this period (Figure 1a), as the proportion of patients with tumors <2 cm and tumors 2 to 4 cm increased 9% and 11%, respectively while the proportion of patients with tumors between 4 to 7 cm and tumors >7 cm decreased 5% and 15%, respectively, from time periods 1989–1992 to 2001–2004 (p<0.0001). Similarly, a stage migration towards T1a lesions was observed (Figure 1b). For example, the proportion of patients with T1a tumors increased 23% while the proportion of patients with T1b and T2 tumors decreased 3% and 8%, respectively, from periods 1989–1992 to 2001–2004 (p<0.0001). However, the correlation between tumor size and pathologic tumor stage was imperfect. Among patients with tumors < 2 cm and tumors between 2 to 4 cm, 93% and 90%, respectively, were classified as pathologic T1a tumors (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Figure 1a. Tumor size distribution according to surgery year

Figure 1b. Tumor stage distribution according to surgery year

Rates of Renal Operations

Figure 2 demonstrates the changes in the number of radical and partial nephrectomies performed from 1989 to 2004. The number of renal operations (radical and partial nephrectomy) increased with time. For patients with localized tumors presenting for nephrectomy from 1989 to 1992, radical nephrectomy comprised 88% of renal operations, while partial nephrectomy comprised 12%. In the later years, partial nephrectomy became the predominant renal operation performed at our institution for localized kidney tumors. For instance, partial nephrectomy comprised 53% of all renal operations from 2001 to 2004, compared to 47% for radical nephrectomy.

Figure 2.

Renal operations were first performed laparoscopically in 2002. Laparoscopic radical nephrectomies comprised 1.9%, 14.8%, and 6.7%, while laparoscopic partial nephrectomies comprised 0.6%, 2.1%, and 3.3%, of renal operations performed in 2002, 2003, and 2004, respectively (data not shown).

Other Tumor and Surgery Related Characteristics

Tumor histology did not vary significantly with time (Figure 3a). Clear cell tumors predominated in each time era, approximating 70% of all localized tumors, irrespective of year of surgery. Tumors with papillary histology comprised 13% to 19% of all tumors, depending on year of surgery, followed by chromophobe tumors, which comprised 6% to 13% (p=0.099).

Figure 3.

Figure 3a. Tumor histology according to surgery year

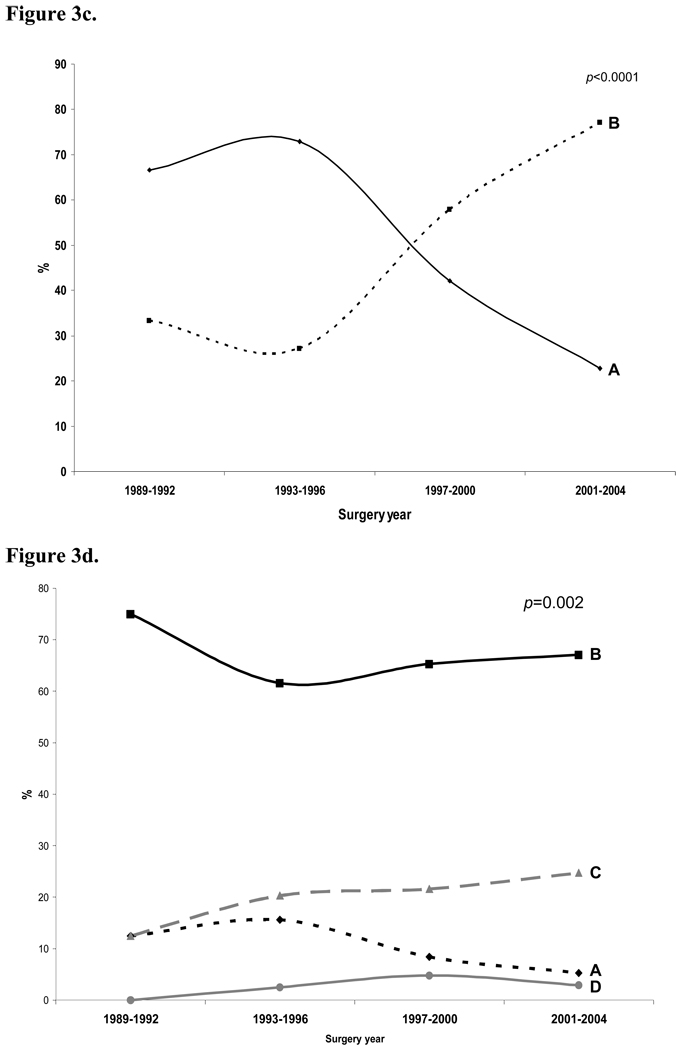

Figure 3b. Proportion of patients receiving a lymphadenectomy according to surgery year

Figure 3c. Proportion of patients receiving an adrenalectomy according to surgery year

Figure 3d. Fuhrman tumor grade according to surgery year

In general, patients undergoing nephrectomy in more contemporary eras were less likely to undergo a concomitant lymph node dissection (Figure 3b) and adrenalectomy (Figure 3c) when compared to cohorts from earlier eras. When excluding historical data with incomplete ascertainment (i.e. 1989–1992 cohort), 37% and 73% of patients from 1993–1996 underwent lymphadenectomy and adrenalectomy, respectively, when compared to 27% and 23% of patients from 2001–2004.

Disease Progression

Overall, 179 patients (11%) developed disease progression following nephrectomy, of which 16 patients (1%) experienced isolated local recurrence while 163 patients (10%) experienced distant metastasis. Among those undergoing radical nephrectomy, 161 (15%) of 1,050 had disease progression compared with 18 (3%) of 568 patients after a partial nephrectomy (p<0.0001)

PFS for the entire cohort of patients presenting with localized renal cortical tumors, stratified by 4-year cohorts, is shown if Figure 4a. The actuarial 5-year PFS rates following nephrectomy (Table 2) was 88%, 84%, 89% and 90% for patients treated during 1989–1992, 1993–1996, 1997–2000, and 2001–2004, respectively (p=0.309).

Figure 4.

Figures 4a. PFS for entire cohort of patients presenting with localized renal cortical tumors; 4b. PFS for patients with renal tumors <2 cm; 4c. PFS for patients with renal tumors ≥2 and ≤4 cm; 4d. PFS for patients with renal tumors >4 and ≤7 cm; 4e. PFS for patients with renal tumors >7 cm

Table 2.

5-year progression-free survival and overall patient survival, according to patient related, tumor related, and surgery related characteristics

| 5-Year PFS |

5-Year OS |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | No. of patients |

No. of events |

% | 95% CI | p-value | No. of events |

% | 95% CI | p-value |

| Patient related | |||||||||

| Age at surgery | 0.8315 | <0.0001 | |||||||

| <40 | 80 | 9 | 91 | 81–96 | 8 | 93 | 83–98 | ||

| 40–49 | 209 | 18 | 91 | 85–95 | 22 | 93 | 88–96 | ||

| 50–59 | 393 | 49 | 87 | 83–90 | 67 | 84 | 80–88 | ||

| 60–69 | 502 | 55 | 88 | 84–91 | 122 | 81 | 77–85 | ||

| 70–79 | 365 | 42 | 87 | 82–91 | 121 | 76 | 70–81 | ||

| >80 | 69 | 6 | 87 | 73–94 | 34 | 60 | 44–73 | ||

| Gender | 0.0562 | 0.6735 | |||||||

| Male | 1047 | 126 | 86 | 83–88 | 235 | 82 | 79–85 | ||

| Female | 571 | 53 | 91 | 88–94 | 139 | 82 | 78–86 | ||

| Race | <0.0001 | 0.7255 | |||||||

| White | 1439 | 143 | 89 | 87–91 | 330 | 82 | 80–85 | ||

| Black | 88 | 5 | 96 | 89–99 | 24 | 76 | 63–85 | ||

| Other | 91 | 31 | 64 | 52–74 | 20 | 83 | 71–91 | ||

| Tumor related | |||||||||

| Tumor laterality | 0.4774 | 0.3447 | |||||||

| Left | 774 | 92 | 87 | 84–90 | 181 | 81 | 78–84 | ||

| Right | 844 | 87 | 89 | 86–91 | 193 | 83 | 80–86 | ||

| Tumor stage | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||||

| T1 | 1049 | 49 | 95 | 93–97 | 188 | 87 | 85–90 | ||

| T2 | 156 | 36 | 74 | 64–82 | 51 | 76 | 67–83 | ||

| T3 | 375 | 68 | 81 | 76–85 | 127 | 72 | 67–77 | ||

| T4 | 10 | 7 | 22 | 3–51 | 8 | 22 | 3–51 | ||

| Tumor grade | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||||

| 1 | 94 | 6 | 93 | 84–97 | 22 | 85 | 75–91 | ||

| 2 | 714 | 54 | 91 | 88–93 | 133 | 84 | 80–87 | ||

| 3 | 247 | 46 | 78 | 71–84 | 63 | 76 | 68–82 | ||

| 4 | 37 | 11 | 60 | 38–76 | 17 | 51 | 31–67 | ||

| Tumor histology | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||||

| Clear cell | 1126 | 143 | 86 | 84–89 | 283 | 81 | 78–83 | ||

| Papillary | 261 | 15 | 95 | 92–98 | 49 | 86 | 80–90 | ||

| Chromophobe | 175 | 7 | 94 | 87–97 | 20 | 90 | 82–94 | ||

| Unclassified | 53 | 13 | 70 | 49–84 | 20 | 74 | 57–85 | ||

| Collecting duct | 3 | 1 | 67 | 5–95 | 2 | 67 | 5–95 | ||

| Surgery related | |||||||||

| Surgery year | 0.309 | 0.0811 | |||||||

| 1989–1992 | 189 | 38 | 88 | 82–92 | 89 | 83 | 77–88 | ||

| 1993–1996 | 295 | 51 | 84 | 79–88 | 119 | 80 | 75–84 | ||

| 1997–2000 | 461 | 49 | 89 | 86–92 | 103 | 84 | 80–87 | ||

| 2001–2004 | 673 | 41 | 90 | 84–93 | 63 | 79 | 73–84 | ||

| Type of operation | <0.0001 | 0.0004 | |||||||

| Radical | 1050 | 161 | 84 | 82–87 | 312 | 80 | 77–82 | ||

| Partial | 568 | 18 | 96 | 93–98 | 62 | 89 | 85–92 | ||

| Surgical margin status |

0.1176 | 0.1403 | |||||||

| Negative | 1492 | 160 | 88 | 86–90 | 333 | 83 | 80–85 | ||

| Positive | 100 | 15 | 84 | 74–91 | 25 | 77 | 65–85 | ||

| Adrenalectomy | <0.0001 | 0.0034 | |||||||

| No | 929 | 49 | 93 | 91–95 | 144 | 86 | 83–89 | ||

| Yes | 689 | 130 | 82 | 79–85 | 230 | 78 | 74–81 | ||

| Lymph node dissection |

<0.0001 | 0.0093 | |||||||

| No | 1116 | 79 | 92 | 90–94 | 235 | 85 | 82–87 | ||

| Yes | 487 | 98 | 78 | 74–82 | 129 | 77 | 72–81 | ||

Figures 4b, 4c, 4d, and 4e show 5-year PFS for patients with renal tumors < 2 cm, 2 to 4 cm, 4 to 7 cm, and >7 cm, respectively. There were no significant differences in 5-year PFS with respect to tumor size over time.

On univariable analysis (Table 2), factors that were associated with disease progression include patient race (p<0.0001), tumor stage (p<0.0001), Fuhrman tumor grade (p<0.0001), tumor histology (p<0.0001), type of operation (p<0.0001), having undergone an adrenalectomy (p<0.0001), and having undergone a lymphadenectomy (p<0.0001). When significant variables were retained in a multivariable Cox regression analysis (Table 3), only tumor stage and Fuhrman tumor grade were associated with disease progression. Patients with T2, T3, and T4 tumors were at 4.5 (95% CI 2.6–7.8, p<0.0001), 2.3 (95% CI 1.4–3.9, p=0.001), and 11.4 (95% CI 3.5–37.2, p<0.0001) odds, respectively, of having disease progression when compared to those with T1 tumors. Those with Fuhrman grade 3 and 4 tumors were at 2.7 (95% CI 1.0–7.1, p=0.043) and 4.0 (95% CI 1.3–12, p=0.015) odds of having disease progression when compared to those with grade 1 tumors. There were no significant differences between the likelihood of disease progression for grade 1 and grade 2 tumors. Figures 5a and 5b show 5-year PFS according to tumor stage and Fuhrman grade, respectively.

Table 3.

Multivariable Cox regression analysis of factors associated with disease progression following surgical resection for patients presenting with localized kidney cancer

| Patient Characteristics | No. of events | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p- value |

|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 179 | ||

| Race | |||

| White | 143 | 1.0 (referent) | |

| Black | 5 | 0.57 (0.18, 1.83) | 0.347 |

| Other | 31 | 1.17 (0.47, 2.92) | 0.736 |

| Tumor stage | |||

| T1 | 49 | 1.0 (referent) | |

| T2 | 36 | 4.49 (2.57, 7.84) | <0.0001 |

| T3 | 68 | 2.34 (1.41, 3.89) | 0.001 |

| T4 | 7 | 11.36 (3.47, 37.19) | <0.0001 |

| Tumor grade | |||

| 1 | 6 | 1.0 (referent) | |

| 2 | 54 | 1.55 (0.61, 3.95) | 0.361 |

| 3 | 46 | 2.71 (1.03, 7.08) | 0.043 |

| 4 | 11 | 3.96 (1.31, 11.95) | 0.015 |

| Tumor histology | |||

| Clear cell | 143 | 1.0 (referent) | |

| Papillary | 15 | 0.29 (0.07, 1.19) | 0.085 |

| Chromophobe | 7 | 0.45 (0.14, 1.44) | 0.178 |

| Unclassified | 13 | 2.51 (1.16, 5.47) | 0.02 |

| Collecting duct | 1 | - | - |

| Type of operation | |||

| Radical nephrectomy | 161 | 1.0 (referent) | |

| Partial nephrectomy | 18 | 0.69 (0.32, 1.47) | 0.337 |

| Adrenalectomy | |||

| No | 49 | 1.0 (referent) | |

| Yes | 130 | 1.17 (0.72, 1.90) | 0.523 |

| Lymph node dissection | |||

| No | 79 | 1.0 (referent) | |

| Yes | 98 | 1.50 (0.97, 2.31) | 0.068 |

Figure 5.

Figure 5a. Progression-free survival according to tumor stage

Figure 5b. Progression-free survival according to tumor grade

Overall Survival

A total of 376 patients (23%) died from any cause following nephrectomy at a median follow-up time of 50.4 months (IQR 61.3 months). The actuarial 5-year OS rates following nephrectomy (Table 2) was 83%, 80%, 84% and 79% for patients treated during 1989–1992, 1993–1996, 1997–2000, and 2001–2004, respectively (p=0.0811).

On univariable analysis (Table 2), factors that were associated with overall survival include patient age (p<0.0001), tumor stage (p<0.0001), Fuhrman tumor grade (p<0.0001), tumor histology (p<0.0001), type of operation (p=0.0004), having undergone an adrenalectomy (p=0.0034), and having undergone a lymphadenectomy (p=0.0093). When significant variables were retained in a multivariable Cox regression analysis (Table 4), only patient age and tumor stage were associated with overall survival. Patients aged 70 years or older were at greater odds of dying from any cause after renal surgery than those younger than 70 years. Patients with T2, T3, and T4 tumors were at 1.7 (95% CI 1.1–2.6, p=0.028), 1.4 (95% CI 1.0–1.9, p=0.037), and 5.3 (95% CI 2.0–14.2, p=0.001) odds, respectively, of dying from any cause when compared to those with T1 tumors. Figures 6a and 6b show 5-year OS according to patient age and tumor stage, respectively.

Table 4.

Multivariable Cox regression analysis of factors associated with overall patient survival following surgical resection for patients presenting with localized kidney cancer

| Patient Characteristics | No. of events | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p- value |

|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 374 | ||

| Patient age (years) | |||

| <40 | 8 | 1.0 (referent) | |

| 40–49 | 22 | 1.00 (0.37, 2.70) | 0.998 |

| 50–59 | 67 | 1.37 (0.57, 3.26) | 0.48 |

| 60–69 | 122 | 2.27 (0.98, 5.26) | 0.057 |

| 70–79 | 121 | 3.66 (1.58, 8.49) | 0.003 |

| >80 | 34 | 5.75 (2.28, 14.47) | <0.0001 |

| Tumor stage | |||

| T1 | 188 | 1.0 (referent) | |

| T2 | 51 | 1.65 (1.06, 2.57) | 0.028 |

| T3 | 127 | 1.39 (1.02, 1.90) | 0.037 |

| T4 | 8 | 5.27 (1.96, 14.18) | 0.001 |

| Tumor grade | |||

| 1 | 22 | 1.0 (referent) | |

| 2 | 133 | 1.08 (0.68, 1.71) | 0.742 |

| 3 | 63 | 1.28 (0.77, 2.13) | 0.338 |

| 4 | 17 | 3.33 (1.69, 6.58) | 0.001 |

| Tumor histology | |||

| Clear cell | 283 | 1.0 (referent) | |

| Papillary | 49 | 0.82 (0.47, 1.44) | 0.493 |

| Chromophobe | 20 | 0.46 (0.19, 1.14) | 0.094 |

| Unclassified | 20 | 1.81 (0.94, 3.48) | 0.075 |

| Collecting duct | 2 | 7.10 (0.95, 53.2) | 0.057 |

| Type of operation | |||

| Radical nephrectomy | 312 | 1.0 (referent) | |

| Partial nephrectomy | 62 | 0.86 (0.55, 1.33) | 0.492 |

| Adrenalectomy | |||

| No | 144 | 1.0 (referent) | |

| Yes | 230 | 1.10 (0.79, 1.52) | 0.58 |

| Lymph node dissection | |||

| No | 235 | 1.0 (referent) | |

| Yes | 129 | 1.03 (0.77, 1.38) | 0.842 |

Figure 6.

Figure 6a. Overall survival according to patient age

Figure 6b. Overall survival according to tumor stage

DISCUSSION

The treatment paradigm of surgically removing solid renal masses upon detection has recently been questioned. Investigators have shown that the rising incidence of kidney cancer in the past two decades is largely attributable to the increased detection of small renal masses and despite parallel increases in surgical treatment, mortality rates for kidney cancer have continued to rise.9 Furthermore, detection of advanced tumors, including those with regional involvement and distant metastasis, also has increased in incidence, calling into question whether incidental detection has positively impacted mortality and whether the increased detection of asymptomatic tumors by imaging procedures can fully explain the rising incidence trends of kidney cancer.2, 11

A prior study reported that the greatest absolute increase in kidney cancer mortality is in patients with lesions > 7 cm. While cancer-specific mortality rates in that study also rose in patients with tumors < 2 cm, 2–4 cm, and > 4 to 7 cm, the increases were not as pronounced as those with lesions > 7 cm.9

However, other investigators have argued that survival rates, when compared with mortality rates, should more accurately reflect the clinical course of patients after cancer diagnosis. Using data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program, these investigators found improved 5-year relative survival rates over time for kidney cancer patients, particularly for patients with small tumors.12

Similar to reported national trends,9 we demonstrate a size migration towards smaller tumors (Figure 1a) and an increasing number of nephrectomies performed from 1989 to 2004 (Figure 2). Presumably, mortality rates from kidney cancer would be even higher if earlier and incidental detection were not so common.2, 11 However, survival rates did not improve nor differ significantly over time at our institution (Figure 4a). To account for these observed trends in PFS, we evaluated changes in tumor-related and surgery-related factors with respect to time. While Fuhrman tumor grade (Figure 3d) and histology (Figure 3a) did not vary significantly over time, we found a stage migration towards T1a lesions (Figure 1b). Coincident with the favorable stage migration, the proportion of patients receiving a concomitant lymphadenectomy and adrenalectomy at the time of nephrectomy decreased significantly over time (Figures 3b and 3c, respectively), when excluding historical data with incomplete ascertainment (i.e. 1989–1992 cohort). The observable trends in tumor and surgery-related characteristics with respect to time could not account for why PFS did not improve nor differ significantly over time despite a favorable size migration and an increase in the number of operations performed.

In contrast to survival data from the SEER program,12 it is conceivable that more advanced or aggressive tumors are being referred to tertiary care centers for management, that patients in more contemporary eras treated at our center have had more stringent follow-up and therefore increased attribution of death to kidney cancer than in the past, or that selection of indolent tumors for observation at tertiary care centers has led to more aggressive tumors presenting for surgery. This could, in part, account for the differences in 5-year survival rates observed in our data when compared to data from the SEER program. Finally, other unidentified factors may be contributory. For example, it is unclear whether certain environmental, metabolic, or epidemiologic factors such as obesity, hypertension, smoking, or race, alone, or in a multivariate setting, may have negatively influenced the biological behavior of kidney cancers in the past 2 decades, and whether patients with more co-morbid conditions are more likely to be treated at tertiary care centers. Previously, we have reported that although body mass index was associated with a greater proportion of clear cell histology, co-morbidity, and surgical morbidity, it did not adversely impact overall or progression-free survival.13

Factors associated with progression of disease following surgical resection include higher tumor stage and higher Fuhrman grade. Patient age, gender, race, tumor laterality, tumor histology, year of surgery, type of nephrectomy (radical versus partial), surgical margin status, or having had a concomitant adrenalectomy or lymph node dissection were not associated with disease progression.

Investigators previously have noted gender differences in kidney cancer-specific survival after treatment.14, 15 On univariable analysis, we found that at five years following nephrectomy for localized disease, men were at no greater risk of developing disease progression than women (5-year PFS 86% for men versus 91% for women, p=0.0562). However, this trend approached statistical significance and with longer follow-up, we may anticipate that men will be more likely to develop disease progression than women. The main factors contributing to a less favorable prognosis in men are the higher proportion of advanced stage disease and the higher proportion of higher grade disease in men when compared to women. For instance, 64%, 9%, 26%, and 1% of men when compared to 70%, 10.6%, 19%, and 0.4% of women, had pathologic stage T1, T2, T3, and T4 disease, respectively (p=0.009). Fuhrman grade 1, 2, 3, and 4 disease was found in 7%, 63%, 26%, and 4% of men compared to 11%, 70%, 17%, and 2% of women, respectively (p<0.0001).

Finally, 5-year overall patient survival did not differ for patients treated in more contemporary eras when compared to historical cohorts (Table 2) and ranged from 79% to 84%. On multivariable analysis, patient age and tumor stage were the only factors associated with overall survival. Though beyond the scope of this particular study, competing-cause mortality rises with increasing patient age for patients with renal masses16 and must be taken into consideration during surgical planning and in the selection of appropriate candidates for active surveillance as the initial therapeutic approach for select tumors. Since co-morbid conditions like chronic kidney disease (CKD) have been shown to be associated with increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality17 and its prevalence in patients with renal cortical tumors has been reported to be higher than previously thought,18 maximal renal functional preservation is essential.

Limitations of our study include selection bias associated with referrals to a tertiary care center, the retrospective nature of the review, and the fact that some patients remain still at risk for a recurrence with a median follow-up of 50 months. Perhaps cancer-specific survival (CSS) would have been a more meaningful clinical endpoint than PFS. However, given the relatively few events (n=68) available to evaluate CSS and the fact that metastatic disease is uniformly deadly in this disease due to the lack of effective systemic therapies, the use of PFS as a proxy for kidney cancer mortality seems reasonable.

Our findings provide clues for further research into the prognosis of surgically treated kidney cancers. Furthermore, the finding that PFS rates did not improve nor differ significantly with time despite a favorable tumor size migration and increased number of nephrectomies performed requires further research to identify causative mechanisms and argues for a re-evaluation of the current treatment paradigm of surgically removing solid renal masses upon initial detection and consideration of active surveillance for select tumors.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the NIH (National Institutes of Health) Ruth Kirchstein National Research Service Award T32 CA 82088-07 (TLJ).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

We declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2007. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57(1):43–66. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chow WH, Devesa SS, Warren JL, Fraumeni JF., Jr Rising incidence of renal cell cancer in the United States. Jama. 1999;281(17):1628–1631. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.17.1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Volpe A, Panzarella T, Rendon RA, Haider MA, Kondylis FI, Jewett MA. The natural history of incidentally detected small renal masses. Cancer. 2004;100(4):738–745. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee CT, Katz J, Shi W, Thaler HT, Reuter VE, Russo P. Surgical management of renal tumors 4 cm. or less in a contemporary cohort. J Urol. 2000;163(3):730–736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsui KH, Shvarts O, Smith RB, Figlin R, de Kernion JB, Belldegrun A. Renal cell carcinoma: prognostic significance of incidentally detected tumors. J Urol. 2000;163(2):426–430. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)67892-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gudbjartsson T, Thoroddsen A, Petursdottir V, Hardarson S, Magnusson J, Einarsson GV. Effect of incidental detection for survival of patients with renal cell carcinoma: results of population-based study of 701 patients. Urology. 2005;66(6):1186–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luciani LG, Cestari R, Tallarigo C. Incidental renal cell carcinoma-age and stage characterization and clinical implications: study of 1092 patients (1982–1997) Urology. 2000;56(1):58–62. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00534-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Homma Y, Kawabe K, Kitamura T, Nishimura Y, Shinohara M, Kondo Y, et al. Increased incidental detection and reduced mortality in renal cancer--recent retrospective analysis at eight institutions. Int J Urol. 1995;2(2):77–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.1995.tb00428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hollingsworth JM, Miller DC, Daignault S, Hollenbeck BK. Rising incidence of small renal masses: a need to reassess treatment effect. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(18):1331–1334. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greene FPD, Fleming I, et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. ed 6. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hock LM, Lynch J, Balaji KC. Increasing incidence of all stages of kidney cancer in the last 2 decades in the United States: an analysis of surveillance, epidemiology and end results program data. J Urol. 2002;167(1):57–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chow WH, Linehan WM, Devesa SS. Re: Rising incidence of small renal masses: a need to reassess treatment effect. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(7):569–570. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk114. author reply 70-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donat SM, Salzhauer EW, Mitra N, Yanke BV, Snyder ME, Russo P. Impact of body mass index on survival of patients with surgically treated renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2006;175(1):46–52. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Onishi TT, Oishi YY, Goto HH, Yanada SS, Abe KK. Gender as a prognostic factor in patients with renal cell carcinoma. BJU international. 2002;90(1):32–36. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2002.02798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beisland CC, Medby PCPC, Beisland HOHO. Renal cell carcinoma: gender difference in incidental detection and cancer-specific survival. Scandinavian journal of urology and nephrology. 2002;36(6):414–418. doi: 10.1080/003655902762467558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hollingsworth JM, Miller DC, Daignault S, Hollenbeck BK. Five-year survival after surgical treatment for kidney cancer: a population-based competing risk analysis. Cancer. 2007;109(9):1763–1768. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu C-y. Chronic Kidney Disease and the Risks of Death, Cardiovascular Events, and Hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1296–1305. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang WC, Levey AS, Serio AM, Snyder M, Vickers AJ, Raj GV, et al. Chronic kidney disease after nephrectomy in patients with renal cortical tumours: a retrospective cohort study. The Lancet Oncology. 2006;7(9):735–740. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70803-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]