Abstract

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) is an important therapy for heart failure patients with widened electrocardiographic QRS complexes and depressed ejection fractions, however, approximately one-third do not respond. This article presents a practical contemporary approach to the utility of echocardiography to improve CRT patient response by assessing mechanical dyssynchrony, optimizing left ventricular lead positioning, and performing appropriate echo-Doppler optimization, along with future potential roles. Specifically, recent long-term outcome data are presented that demonstrates that baseline dyssynchrony is a powerful marker associated with CRT response, in particular for patients with narrower QRS duration or non left bundle branch block morphology. Advances in speckle tracking echocardiography to tailor delivery of CRT by guiding LV lead position is discussed, including data from randomized clinical trials supporting targeting the LV lead toward the site of latest activation. In addition, an update on the current role of Doppler echocardiographic device optimization after CRT implantation is reviewed.

Keywords: echocardiography, heart failure, pacemaker, Doppler

Introduction

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) has become established as an important therapy for heart failure (HF) patients with a widened electrocardiographic QRS complex and depressed ejection fraction (EF).[1–3] The majority of patients who meet current guidelines for implantation receive benefit in terms of morbidity and mortality, however, approximately one-third of patients do not appear to respond. [4, 5] Echocardiography has played a variety of roles in attempting to improve the care of CRT recipients, including patient selection, guiding lead placement and device optimization after implantation. This article will present a practical contemporary approach of the utility of echocardiography to improve CRT patient response by assessing mechanical dyssynchrony, optimizing left ventricular (LV) lead positioning, performing appropriate echo-Doppler device optimization, and introduce future potential roles.

Echocardiographic Evaluation of Dyssynchrony

Current CRT guidelines use electrocardiographic QRS widening as a marker for abnormalities in the timing of regional cardiac contraction, known as dyssynchrony. However, there is increasing evidence that mechanical dyssynchrony is the major pathologic entity that is associated with deleterious biological processes affecting myocardial function in HF patients, and the therapeutic effect of CRT is closely linked to improvement in dyssynchrony. Although there is an association of QRS widening with cardiac mechanical dyssynchrony, several studies have demonstrated that the surface 12 lead electrocardiogram (ECG) lacks the sensitivity and specificity to precisely quantify mechanical dyssynchrony, and that imaging approaches are superior. [6–14] Unfortunately, the field of echocardiographic dyssynchrony has been criticized largely because of a multi-center observational study, known as PROSPECT, which examined several baseline dyssynchrony measurements and determined CRT response at 6 months. [15] Although some interpreted PROSPECT as a completely negative study, routine pulsed Doppler measures predicted CRT response. Specifically, the pre-ejection interval ≥ 140 ms (n=239) predicted both clinical composite score response (p=0.013) and LV end-systolic volume reduction ≥ 15% response (p=0.012). Also, the interventricular mechanical delay (IVMD) ≥ 40 ms predicted both clinical composite score response (p=0.045) and LV end-systolic volume reduction ≥ 15% response (p=0.016) (Figure 1). In addition, the tissue Doppler longitudinal velocity delay from the septum to the lateral wall ≥ 60 ms was highly statistically associated with LV end-systolic volume response (p=0.005) (Figure 2). Legitimate criticisms of PROSPECT included an unusually low yield of high quality echo data available, for example only 50% of patients had 12-site standard deviation (Yu Index) tissue Doppler data that could be analyzed. Furthermore, the follow-up duration was short at 6 months and multiple vendors' software and three different echo core labs contributed as confounding variables. [16, 17]

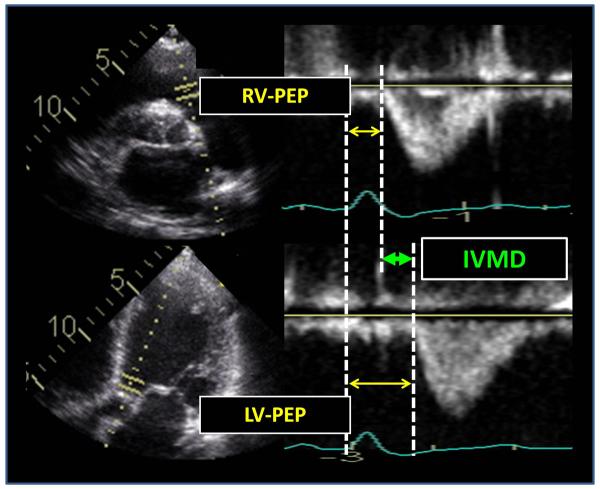

Figure 1.

Routine pulsed Doppler examples from the right ventricular (RV) outflow track (top panels) and left ventricular (LV) outflow track (bottom panels) from a patient with dyssynchrony before cardiac resynchronization therapy. The calculation of interventricular mechanical delay (IVMD) is the difference from between LV pre-ejection period (PEP) and RV PEP (arrows).

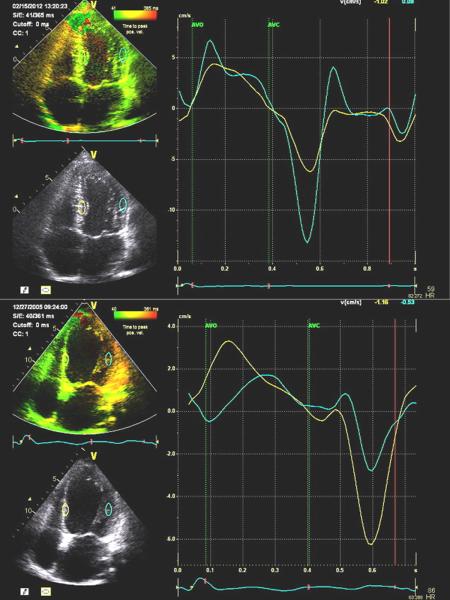

Figure 2.

Examples of color-coded tissue Doppler images from the 4-chamber views (left) and corresponding septal and lateral time-velocity plots (right). The top panels are from a normal subject with similar septal and lateral time-velocity curves. The bottom panels are from a patient with left bundle branch block dyssynchrony before cardiac resynchronization therapy, demonstrating early septal and late lateral wall peak systolic velocities.

More recently, echocardiographic dyssynchrony has been shown to be convincingly associated with important long term clinical outcome and survival after CRT. One study of 229 patients with routine CRT indications showed that echocardiographic dyssynchrony before CRT was associated with a more favorable survival free from death, heart transplant or left ventricular assist device (LVAD). [10] Specific associations with favorable outcome over 4 years were IVMD ≥ 40 ms (p=0.019), Yu Index ≥32ms (p=0.003), and speckle tracking radial strain anteroseptal to posterior wall delay ≥130ms (p=0.003) (Figure 3). When adjusted for confounding baseline variables of ischemic etiology and QRS duration, Yu Index and radial strain dyssynchrony remained independently associated with outcome (p<0.05). Lack of radial dyssynchrony was particularly associated with unfavorable outcome in those with a QRS duration of 120–150 ms (p=0.002). The STAR (Speckle Tracking and Resynchronization) used a prospective multi-center design on 132 consecutive CRT patients with class III and IV heart failure, ejection fraction (EF) ≤ 35% and QRS ≥ 120ms with similar primary end-points of death, transplant, or LVAD. [18] Baseline radial strain dyssynchrony, defined as ≥ 130 ms, had the highest sensitivity at 86% for predicting EF response with a specificity of 67% over 3.5 years. (Figure 4). Patients who lacked both radial and transverse dyssynchrony had unfavorable clinical events of death, transplant or LVAD occur in 53%, in contrast to events occurring in 12% of patients where baseline dyssynchrony was present (p<0.01). A third study by Delgado et al. examined speckle tracking radial dyssynchrony in 397 CRT patients with ischemic disease. [19] They observed that radial dyssynchrony ≥ 130 ms at baseline was an independent predictor of superior long-term survival after CRT over 3 years. (p=0.001). These three studies combine to 758 patients with similar results that echocardiographic dyssynchrony is favorably associated with long-term survival after CRT. Despite these cumulative supportive data, echocardiographic dyssynchrony has not yet been adopted by panels of experts for selecting patients for routine CRT.

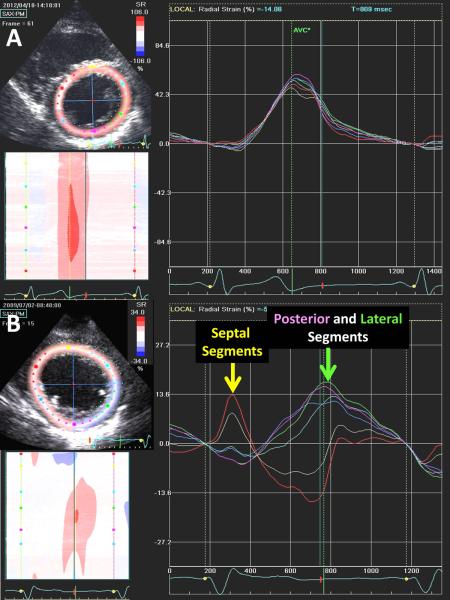

Figure 3.

Examples of speckle tracking radial strain images from the mid-ventricular short axis plane with corresponding time-strain plots from 6 segments. The top panels are from a normal subject with 6 synchronous time-strain curves. The bottom panels are from a patient with left bundle branch block dyssynchrony before cardiac resynchronization therapy, demonstrating early septal and late posterior and lateral wall peak strain.

Figure 4.

Kaplan Meier plots of probability of event free survival free from heart transplant or left ventricular assist device in cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) patients with and without radial dyssynchrony by speckle tracking radial strain from the STAR study. The cut-off defined as significant dyssynchrony was a septal to posterior wall delay of at least 130 ms. Significant radial dyssynchrony before CRT was associated with a more favorable clinical outcome.

Echocardiographic Dyssynchrony and Narrower QRS width or Non-LBBB Patients

Recent updated guidelines have summarized that the evidence of benefit from CRT is most convincing in patients whom have QRS duration > 150 ms and/or LBBB morphology, and is less convincing in patients with narrower QRS width < 150 ms when using electrocardiographic criteria alone. [4, 5, 20] Accordingly, it appears that the opportunity for echocardiographic dyssynchrony to play a potential adjunct role in refining patient selection for CRT is in subgroups where QRS width is < 150 ms or QRS morphology is not LBBB. Evidence exists of the additive value of echocardiographic dyssynchrony in improving patient selection with narrower QRS width in the CARE-HF trial where patients with a QRS interval of 120 to 149 ms were required to meet two of three echocardiographic criteria for dyssynchrony: an aortic preejection delay > 140 ms, an IVMD > 40 ms, or delayed activation of the posterolateral left ventricular wall. [3] In the pre-defined subgroup of patients with QRS width < 160 ms, CRT conferred a benefit in reducing death or cardiovascular hospitalizations compared to control with a hazard ratio of 0.74 (95% confidence interval of 0.54–1.02). This beneficial result of CRT in patients with narrower QRS from CARE-HF where echocardiographic dyssynchrony was required is in contrast to other clinical trials that did not require an assessment of mechanical dyssynchrony. [20]

Other more recent data have suggested that a potential application of echocardiographic dyssynchrony to assist in patient selection for CRT is in those with non-LBBB QRS morphology. The MADIT-CRT trial randomized New York Heart Association Class I–II HF patients with depressed EF to CRT with a defibrillator versus a defibrillator alone. [21] CRT afforded a significant reduction in heart failure hospitalizations or deaths as the primary endpoint overall, but important subgroup analysis revealed that patients with LBBB morphology received the greatest benefit. [22] Accordingly, only New York Heart Association Class I–II HF patients with LBBB are currently considered candidates for CRT. [4, 5] The impact of echocardiographic dyssynchrony for predicting response to CRT in class III–IV HF patients with widened QRS but non-LBBB morphology was recently studied in 248 CRT patients with QRS ≥120ms and EF ≤35%. [23] Of these patients 124 with LBBB were compared to 80 who had intraventricular conduction delay and 44 with right bundle branch block (RBBB). LBBB patients had a more favorable long-term survival free from transplant or LVAD, than either intraventricular conduction delay or RBBB patients. However, when stratifying patients by the presence or absence of dyssynchrony, non-LBBB patients with radial dyssynchrony had a more favorable long term survival than those without dyssynchrony (hazard ratio 2.6; 95% confidence interval 1.47–4.53, p=0.0008). (Figure 5) Using routine pulsed Doppler as a less technically demanding dyssynchrony measure, non-LBBB patients with IVMD ≥ 40 ms had a much more favorable long term survival after CRT than those with lesser IVMD (hazard ratio (HR) 4.9; 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.60– 9.16, p=0.0007). Using either method, RBBB patients who lacked dyssynchrony had the least favorable outcome. Accordingly, dyssynchrony appears to be a promising potential adjunct to improve patient selection for CRT with non-LBBB QRS morphologies.

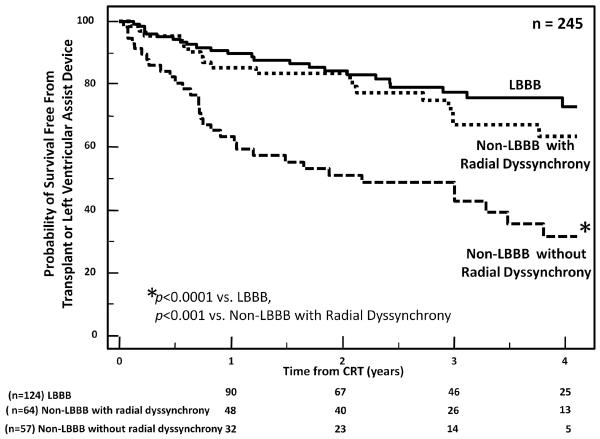

Figure 5.

Kaplan Meier plots of probability of event free survival free from heart transplant or left ventricular assist device in cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) patients grouped by those with left bundle branch block (LBBB) and those non-LBBB and with and without radial dyssynchrony. The cut-off defined as significant dyssynchrony was a septal to posterior wall delay of at least 130 ms. Non-LBBB patients with significant radial dyssynchrony before CRT had a more favorable clinical outcome, similar to those with LBBB.

Echocardiographic Dyssynchrony in Patients with Narrow QRS

Fundamental to current patient selection for CRT is QRS widening. An intriguing hypothesis is that mechanical dyssynchrony exists in a subset of HF patients with truly narrow QRS width (usually defined as < 130 ms). In other words, the concept is that abnormalities of regional mechanical activation in HF patients may not be evident by the 12-lead surface ECG, and that they may benefit from CRT. Accordingly, cardiac imaging is essential to detect mechanical dyssynchrony in patients with narrow QRS. There was one completed randomized clinical trial known as ReThinQ that tested this hypothesis in CRT patients with QRS width < 130 ms with echocardiographic dyssynchrony by tissue Doppler or M-mode. [24] This study examined peak oxygen consumption at 6 months after CRT as the primary end point and showed no significant difference between treatment and control groups. However, significant improvements in HF functional class as a secondary end-point was observed in patients randomized to CRT. Furthermore, peak oxygen consumption significantly increased with CRT in a prespecified subgroup with a QRS interval of 120–129 ms (p=0.02). Although reported as negative, this trial may be considered inconclusive because of a relatively small sample of 156 randomized patients and a follow-up duration limited to 6 months. Accordingly, a much larger randomized clinical trial, known as EchoCRT, is underway to test the hypothesis that HF patients with reduced EF and QRS width < 130 ms may be helped by CRT if they have dyssynchrony detected by echocardiography. [25] This study defines dyssynchrony as a speckle tracking radial strain septal to posterior wall delay ≥ 130 ms and/or tissue Doppler longitudinal velocity opposing wall delay ≥ 80 ms. EchoCRT proposes to randomize approximately 1,200 patients with a primary end-point as time to first HF hospitalization or death, with a follow-up duration of 2 years. This currently on-going study will likely make a major contribution to our understanding of the potential of echocardiographic dyssynchrony to influence patient selection for CRT.

Echocardiographic Guided Left Ventricular Lead Positioning

The potential role of echocardiography in assisting placement of the LV lead for CRT was introduced several years ago [26–28], and recent emerging data have increased interest. The routine clinical approach currently to CRT is to place two pacemaker leads, one in the right ventricular apex and a second LV lead retrograde through the coronary sinus directing the tip into a posterior or lateral epicardial coronary vein. This is typically done with coronary venography under fluoroscopic guidance by selecting a coronary vein that is most accessible or that can offer a stable pacing position. Previous observational studies have shown that patients in whom the LV lead was at the site of latest mechanical activation may result in a greater resynchronization effect and clinical benefit. For example, Murphy et al. used color-coded tissue Doppler longitudinal velocities latest time to peak tissue velocity in the first half of the ejection phase to determine site of latest activation. [27] They observed in 54 patients that those with LV lead placement concurrent with the site of latest activation had significantly greater reverse remodeling 6 months after CRT than those with remote LV lead locations. Suffeletto et al. introduced speckle tracking radial strain echocardiography to identify the site of latest mechanical activation before CRT and also observed that patients with concordant LV lead placement had more favorable LV EF response. [28] Similar to Suffoletto, Ypenburg et al analyzed site of latest activation by speckle tracking radial strain in a larger cohort of 244 CRT patients. [29] Echocardiography was performed before CRT implantation and 6 months after. In 153 CRT patients with concordant LV lead position, they observed significant LV reverse remodeling at 6 months as well as greater improvements in long term all-cause mortality and HF hospitalizations, in comparison to patients with discordant LV leads. In the study by Delgado et al of 397 patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy,[19] speckle tracking radial strain was used to demonstrate independent and additive favorable effects of CRT associated with baseline dyssynchrony and lack of scar at lead position. They found lead concordance with site of latest activation to be associated with improved long-term survival and reduced HF hospitalizations.

Most recently, two independent randomized controlled clinical trials strengthened support for improving clinical response to CRT using an echocardiographic guided LV lead strategy. The TARGET trial (Targeted Left Ventricular Lead Placement to Guide Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy) randomized 220 patients with routine CRT indications to either LV Lead targeted to site of latest activation determined by speckle tracking radial strain or routine LV lead positioning. [30] (Figure 6) In addition, speckle tracking radial strain amplitude data was used to avoid free-wall regions with less than 10% wall thickening felt representative of scar. They reported a more favorable effect of targeted LV lead placement in patients after 6 months of CRT on their primary end-points of LV volumes and EF. Favorable effects of targeted LV lead placement were also observed in the secondary endpoints of HF functional class, 6-min walk test, and HF hospitalizations combined with death. They used multivariate regression analyses to demonstrate important related effects on LV reverse remodeling at 6 months as follows: lack of scar at LV pacing site HR 3.06, 95% CI 1.01–9.26, p=0.048, concordant LV lead location with site of latest activation HR 4.43, 95% CI 2.09–9.40, p=0.009 and radial strain dyssynchrony HR 5.95, 95% CI of 2.78–12.7 p=0.009. The Speckle Tracking Assisted Resynchronization Therapy for Electrode Region (STARTER) trial was a similar but independent study that randomized 187 CRT patients to CRT to speckle-tracking echo guided vs. routine LV lead placement. [31] Basal and mid-LV short axis planes were analyzed by speckle tracking radial strain to determine the latest time to peak strain in 8 free-wall segments. Preliminary results were that patients with echo-guided LV lead position had significantly better outcome in the primary endpoint of death or HF hospitalization, as well as improvements in reverse remodeling. (Figure 7). STARTER also demonstrated that echoguided lead placement was associated with a comparatively better reduction of mechanical dyssynchrony as compared to routine lead placement and that reduction in mechanical dyssynchrony was strongly associated with long-term survival free from heart failure hospitalization. Although the STARTER results were only presented in preliminary abstract form at the time this was written, these two randomized controlled clinical trials combine with the previous body of observational data to provide evidence to support adopting an echo guided lead strategy to improve patient outcomes for CRT.

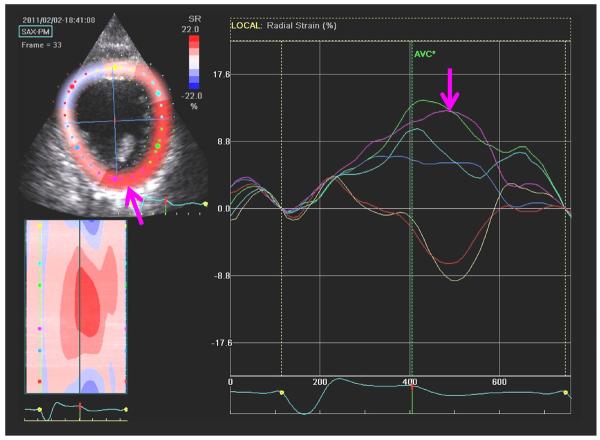

Figure 6.

An example of a speckle tracking radial strain image from the mid-ventricular short axis plane with corresponding time-strain plots from 6 segments. The right arrow indicates the posterior wall segment having the latest time to peak strain. The left arrow indicates the corresponding anatomical segment with the latest peak strain for LV lead targeting.

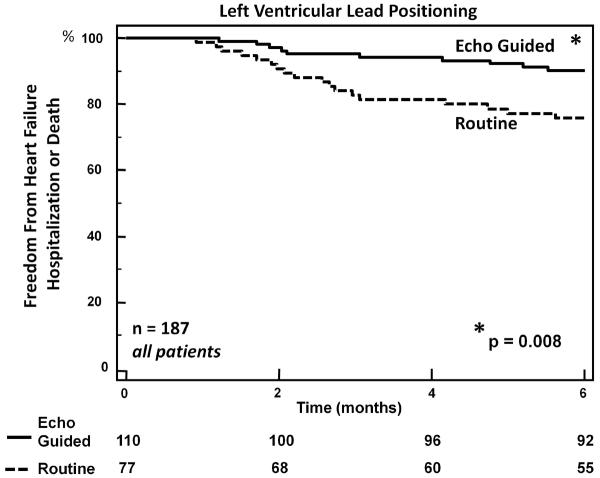

Figure 7.

Kaplan Meier plots of freedom from heart failure hospitalization or death from the STARTER trial showing 6 month data extracted as preliminary results. Cardiac resynchronization therapy patients were randomized to either LV lead positioning toward the site of latest activation by speckle tracking radial strain, or routine empiric lead placement as a control. The echo-guided strategy was associated with a significant reduction in heart failure hospitalizations or death.

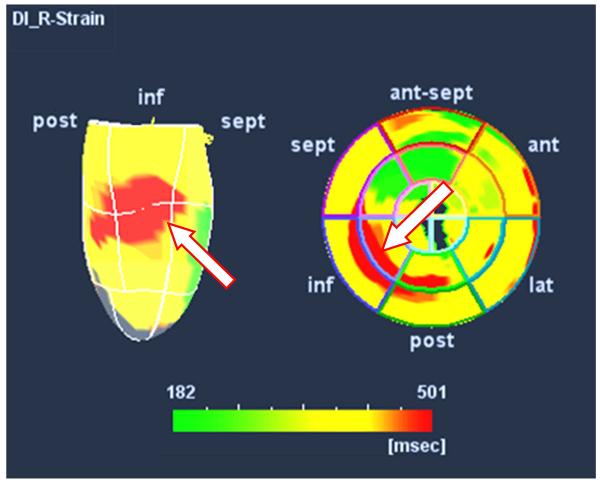

There have been technological advancements in three-dimensional (3D) speckle tracking echocardiography that has improved our understanding of mechanical dyssychrony. [32, 33] Tanaka et al. showed in a pilot series of 54 HF patients for CRT that the distribution of site of latest activation may be plotted in a 3D format that enhanced our understanding of the spatial relationship of regional LV mechanics. This approach has promise to improve LV lead guidance and further study is underway, currently. (Figure 8)

Figure 8.

An example of color-coded three-dimensional speckle tracking strain in a patient with widened QRS who was referred for cardiac resynchronization therapy. The apex down three-dimensional map is on the left and the polar map is on the right. The latest site of peak radial strain, color- coded as red, appears in the mid ventricular inferior-posterior region. This representation has potential to assist in guiding left ventricular lead positioning.

LV lead placement in Relation to Scar

Complementary to guiding the LV lead to the site of latest mechanical activation is using imaging to guide LV leads to avoid scar. Bleeker et al originally demonstrated that LV lead position in a region of myocardial scar results in less favorable results in a pilot of 40 patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy undergoing CRT. [34] They used late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging to define the location and transmurality of scar (defined as extending >50% of LV wall thickness). They observed that patients with transmural scar in the posterolateral region had less improvements in LV remodeling compared to patients with LV leads positioned in regions without scar. Interestingly, they reported that posterior lateral scar was associated with non-response, regardless of dyssynchrony by tissue Doppler. Leyva et al reported a large investigation of scar characterization in CRT patients using LGE by CMR, comparing 209 patients where LV lead position was attempted to avoid scarred segments to 350 patients where LV lead placement was routine. [35] Among the CMR guided patients, those with successful LV lead placement away from scar had a more favorable clinical outcome after CRT than those where the implanter was unsuccessful and the LV lead was placed in a scared region. LV lead in scar was associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular death (HR: 6.34), cardiovascular death or HF hospitalizations (HR: 5.57), death from pump failure (HR: 5.40), compared to patients with LV lead not in scar (all p < 0.0001). Patients without LV guiding in whose scar and lead interaction was not reported, had intermediate outcome, with HRs of 1.51 (p = 0.0726), 1.61 (p = 0.0169) and 1.87 (p = 0.0005), respectively.

Although the majority of literature supports using CMR LGE for quantifying scar, echocardiography remains a more readily accessible imaging modality in most clinical environments and recent interest has emerged to use speckle tracking strain as a marker for scar. In the above mentioned seminal paper, Delgado et al used a <16.5% radial strain cutoff to relate LV lead position in scar as having a less favorable outcome in ischemic cardiomyopathy patients, which was of additive prognostic value to dyssynchrony and LV lead at site of latest activation. [19] Khan et al also used radial strain in a group of 140 CRT patients and observed that reverse remodeling response was significantly lower in those patients where low amplitude radial strain was < 9.8% at site of LV lead placement (62.7% vs. 31.3%, p <0.05) with 92% specificity and 39% sensitivity. [36] These investigators went on to apply the combination of targeting LV lead position to avoiding scared regions (radial strain <9.8%) while seeking the site of latest activation in the TARGET randomized trail previously discussed. [30] The targeted LV strategy was associated with more favorable LV reverse remodeling and superior clinical outcomes. In summary, there is growing evidence that avoiding scar is highly advisable when placing LV lead for CRT. A larger experience supports assessing transmural scar by CMR LGE, however, speckle tracking radial strain appears to be able to play a role in determine regions of likely scar. Further study is required to establish the radial strain cut-off most clinically useful in its association with scar.

Doppler Echocardiographic Device Optimization

The initial proposal of echocardiography for playing a role in improving response to CRT began with Doppler atrioventricular (AV) and ventricular-ventricular (VV) optimization. [37, 38] However, several subsequent studies have suggested that routine Doppler optimization may not be as important as originally thought. Kedia et al reported a large clinical experience of Doppler optimization using mitral inflow and LV outflow velocities in 215 CRT patients. [39] They reported a significant difference between AV delay pre- and post-optimization (120 ± 25 and 135 ± 40 ms, respectively, p = 0.0001). However, optimization achieved improvement in diastolic filling patterns by at least one stage in only 9%, and when comparing patients with AV delay < or > 140 ms, no significant differences in clinical outcomes were observed. The FREEDOM trial randomized patients to a device-based AV and VV optimization algorithm (QuickOpt) employed frequently at 3 month intervals versus a routine clinical approach. [40] Of 1,647 patients enrolled, there were no differences after 1 year of CRT in the pre-specified clinical composite score between the treatment arms (p=0.86). Furthermore, there was no difference between frequent device-based optimization and standard care based on physicians discretion (p = 0.8 vs. standard care with AV/VV optimization and p = 0.65 vs. standard care with empirical settings).

Another large controlled trial (SMART-AV) randomized 980 patients to three AV optimization strategies: a device-based electrocardiogram algorithm (SmartDelay), echo-Doppler optimization, or empiric “out of the box” settings with AV delay = 120 ms, and VV delay = 0. [42] This was uniquely important because it included comparing echo-Doppler optimization to a control strategy of no optimization at all. Overall, no significant differences between 3 treatment arms were observed in the primary end point of LV end-systolic volume reduction or secondary clinical end points at 6 months. Interestingly, echocardiographic AV optimization was similar to the empiric AV delay of 120 ms. An unexpected finding from sub-group analysis was that female CRT patients benefited from optimization by either device-based or echo-Doppler approaches, compared to empiric control, even after adjusting for covariates of age, QRS width or baseline LV end-systolic volume index. [42] Beneficial effects of optimization appeared to be entirely concentrated in women with nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Interestingly, optimization in females with nonischemic cardiomyopathy resulted in a shorter median programmed AV delay of 100 ms for both the SmartDelay and echo-optimized groups (p < 0.003 vs. the empiric AV delay of 120 ms). This observation suggests that females with nonischemic cardiomyopathy may be a subgroup of individuals who may benefit from routine optimization after CRT, or at least that an empiric AV delay setting of 120 ms is too long in these individuals. Further prospective study is needed to draw a definitive conclusion.

Although not yet directly tested in a randomized clinical trial, Mullens et al reported the important utility of echo Doppler optimization in the subgroup of patients deemed as CRT nonresponders. [43] After 75 CRT patients underwent a comprehensive protocol-driven evaluation to determine the potential reasons for non-response, 47% appeared to benefit from echo-Doppler AV optimization. Overall, multidisciplinary recommendations led to changes in device settings and/or other therapeutic modifications in 74% of patients and were associated with fewer adverse events (13% vs. 50%, odds ratio: 0.2 [95% confidence interval: 0.07 to 0.56], p = 0.002) compared with those in which no recommendation could be made. Patients with a favorable outcome of intervention had more often changes in device settings including AV timing reprogramming (20% vs. 69%, p < 0.001). These data suggest that a comprehensive evaluation of non-response, including echo-Doppler optimization is appropriate in the subgroup of HF patients who do not seem to be benefiting from CRT.

Conclusion

CRT has been a major clinical advance in the treatment of HF patients. A high level of interest in the utility of echocardiographic approaches to improve patient benefit remains. (Table 1) Long-term outcome data have emerged demonstrating that baseline echocardiographic dyssynchrony is a powerful marker associated with response. Because response rates are much higher in patients with QRS duration > 150 ms or LBBB morphology, the opportunity for echocardiographic dyssynchrony to positively influence CRT patient selection appears to be in those with narrower QRS and with non-LBBB morphology, where the ECG is a less robust surrogate for dyssynchrony. One of the most exciting recent advances for echocardiography to tailor delivery of CRT has been in guiding LV lead position. Two randomized clinical trials have supported the use of positioning the LV lead toward speckle tracking radial strain site of latest activation to improve clinical outcomes after CRT. In addition, data are emerging that diminished radial strain indicating a likely scarred segment may be used to avoid LV lead positioning. Finally, the sum of existing data suggest that routine echo-Doppler device optimization is not required in all patients after CRT, but the subgroups of non-responders and possibly females with nonischemic cardiomyopathy are those who may benefit the most from optimization. This is an exciting and evolving field where new indications and refinements in the utility of echocardiography for improving patient response to CRT are advancing.

Table 1.

Potential Roles of Echocardiography to Improve Patient Response to CRT

| Methods most Widely Supported | Evidence for Clinical Applications | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Echocardiographic Dyssynchrony at Baseline | • Pre-Ejection Delay ≥ 140 ms | • Prognostic Value for all with routine CRT indications |

| • IVMD ≥ 40 ms | • Borderline QRS width (110–130 ms) as adjunct | |

| • TDI Opposing Wall Delay ≥ 80 ms | • Non-LBBB QRS morphology as adjunct | |

| • TDI Yu Index ≥ 32 ms | • Narrow QRS width (< 130 ms): further studies on-going. | |

| • Radial strain delay ≥ 130 ms | ||

|

| ||

| Echo Guided Lead Positioning to Site of Latest Activation | Speckle Tracking Radial Strain site of latest activation | Patients with routine CRT indications |

|

| ||

| Echo Guided Lead Positioning to Avoid Sites of Regional Scar | Avoid segments with < 10% radial strain amplitude | Patients with ischemic disease: emerging support, further studies on-going. |

|

| ||

| Atrioventricular and Ventricular-Ventricular Optimization | • Mitral inflow velocity analysis | • Non-Responders |

| • LV Outflow tract time velocity integral | • Female patients with non-ischemic disease | |

CRT = cardiac resynchronization therapy, IVMD = interventricular mechanical delay, TDI = tissue Doppler imaging, LBBB = left bundle branch block, LV = left ventricular.

Footnotes

Disclosure J. Gorcsan: consultant to Medtronic, Biotronik, and St. Jude Medical; J. J. Marek: none; T. Onishi: none.

References

- 1.Abraham WT, Fisher WG, Smith AL, Delurgio DB, Leon AR, Loh E, et al. Cardiac resynchronization in chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(24):1845–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bristow MR, Saxon LA, Boehmer J, Krueger S, Kass DA, De Marco T, et al. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy with or without an implantable defibrillator in advanced chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(21):2140–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cleland JG, Daubert JC, Erdmann E, Freemantle N, Gras D, Kappenberger L, et al. The effect of cardiac resynchronization on morbidity and mortality in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(15):1539–49. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dickstein K, Vardas PE, Auricchio A, Daubert JC, Linde C, McMurray J, et al. 2010 Focused Update of ESC Guidelines on device therapy in heart failure: an update of the 2008 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure and the 2007 ESC guidelines for cardiac and resynchronization therapy. Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association and the European Heart Rhythm Association. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(21):2677–87. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stevenson WG, Hernandez AF, Carson PE, Fang JC, Katz SD, Spertus JA, et al. Indications for cardiac resynchronization therapy: 2011 update from the Heart Failure Society of America Guideline Committee. J Card Fail. 2012;18(2):94–106. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bax JJ, Bleeker GB, Marwick TH, Molhoek SG, Boersma E, Steendijk P, et al. Left ventricular dyssynchrony predicts response and prognosis after cardiac resynchronization therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(9):1834–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birnie DH, Tang AS. The problem of non-response to cardiac resynchronization therapy. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2006;21(1):20–6. doi: 10.1097/01.hco.0000198983.93755.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gorcsan J., 3rd Finding pieces of the puzzle of nonresponse to cardiac resynchronization therapy. Circulation. 2011;123(1):10–2. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.001297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gorcsan J, 3rd, Kanzaki H, Bazaz R, Dohi K, Schwartzman D. Usefulness of echocardiographic tissue synchronization imaging to predict acute response to cardiac resynchronization therapy. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93(9):1178–81. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ** 10.Gorcsan J, 3rd, Oyenuga O, Habib PJ, Tanaka H, Adelstein EC, Hara H, et al. Relationship of echocardiographic dyssynchrony to long-term survival after cardiac resynchronization therapy. Circulation. 2010;122(19):1910–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.954768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This was the first study to demonstrate the important association of baseline echocardiographic measures of dyssynchrony on long-term survival after cardiac resynchronization therapy.

- 11.Gorcsan J, 3rd, Tanabe M, Bleeker GB, Suffoletto MS, Thomas NC, Saba S, et al. Combined longitudinal and radial dyssynchrony predicts ventricular response after resynchronization therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(15):1476–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sogaard P, Egeblad H, Kim WY, Jensen HK, Pedersen AK, Kristensen BO, et al. Tissue Doppler imaging predicts improved systolic performance and reversed left ventricular remodeling during long-term cardiac resynchronization therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40(4):723–30. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu CM, Chau E, Sanderson JE, Fan K, Tang MO, Fung WH, et al. Tissue Doppler echocardiographic evidence of reverse remodeling and improved synchronicity by simultaneously delaying regional contraction after biventricular pacing therapy in heart failure. Circulation. 2002;105(4):438–45. doi: 10.1161/hc0402.102623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu CM, Fung WH, Lin H, Zhang Q, Sanderson JE, Lau CP. Predictors of left ventricular reverse remodeling after cardiac resynchronization therapy for heart failure secondary to idiopathic dilated or ischemic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91(6):684–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)03404-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chung ES, Leon AR, Tavazzi L, Sun JP, Nihoyannopoulos P, Merlino J, et al. Results of the Predictors of Response to CRT (PROSPECT) trial. Circulation. 2008;117(20):2608–16. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.743120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bax JJ, Gorcsan J., 3rd Echocardiography and noninvasive imaging in cardiac resynchronization therapy: results of the PROSPECT (Predictors of Response to Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy) study in perspective. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(21):1933–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu CM, Bax JJ, Gorcsan J., 3rd Critical appraisal of methods to assess mechanical dyssynchrony. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2009;24(1):18–28. doi: 10.1097/hco.0b013e32831bc34e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanaka H, Nesser HJ, Buck T, Oyenuga O, Janosi RA, Winter S, et al. Dyssynchrony by speckle-tracking echocardiography and response to cardiac resynchronization therapy: results of the Speckle Tracking and Resynchronization (STAR) study. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(14):1690–700. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * 19.Delgado V, van Bommel RJ, Bertini M, Borleffs CJ, Marsan NA, Arnold CT, et al. Relative merits of left ventricular dyssynchrony, left ventricular lead position, and myocardial scar to predict long-term survival of ischemic heart failure patients undergoing cardiac resynchronization therapy. Circulation. 2011;123(1):70–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.945345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The first study to demonstrate independent predictive values of baseline echocardiographic dyssynchrony, left ventricular lead placement in scar and concordance of left ventricular lead with site of latest mechanical activation on long term outcome.

- 20.Sipahi I, Chou JC, Hyden M, Rowland DY, Simon DI, Fang JC. Effect of QRS morphology on clinical event reduction with cardiac resynchronization therapy: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am Heart J. 2012;163(2):260–7. e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moss AJ, Hall WJ, Cannom DS, Klein H, Brown MW, Daubert JP, et al. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy for the prevention of heart-failure events. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(14):1329–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zareba W, Klein H, Cygankiewicz I, Hall WJ, McNitt S, Brown M, et al. Effectiveness of Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy by QRS Morphology in the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial-Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy (MADIT-CRT) Circulation. 2011;123(10):1061–72. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.960898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * 23.Hara H, Oyenuga OA, Tanaka H, Adelstein EC, Onishi T, McNamara DM, et al. The relationship of QRS morphology and mechanical dyssynchrony to long-term outcome following cardiac resynchronization therapy. Eur Heart J. 2012 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs013. Epub 2012 Feb 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study demonstrated the significant association of speckle tracking radial strain dyssynchrony and interventricular mechanical delay on long term survival in cardiac resynchronization patients with non-left bundle branch morphologies.

- 24.Beshai JF, Grimm RA, Nagueh SF, Baker JH, 2nd, Beau SL, Greenberg SM, et al. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy in heart failure with narrow QRS complexes. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(24):2461–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holzmeister J, Hurlimann D, Steffel J, Ruschitzka F. Cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients with a narrow QRS. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2009;6(1):49–56. doi: 10.1007/s11897-009-0009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ansalone G, Giannantoni P, Ricci R, Trambaiolo P, Fedele F, Santini M. Doppler myocardial imaging to evaluate the effectiveness of pacing sites in patients receiving biventricular pacing. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39(3):489–99. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01772-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murphy RT, Sigurdsson G, Mulamalla S, Agler D, Popovic ZB, Starling RC, et al. Tissue synchronization imaging and optimal left ventricular pacing site in cardiac resynchronization therapy. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97(11):1615–21. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suffoletto MS, Dohi K, Cannesson M, Saba S, Gorcsan J., 3rd Novel speckle-tracking radial strain from routine black-and-white echocardiographic images to quantify dyssynchrony and predict response to cardiac resynchronization therapy. Circulation. 2006;113(7):960–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.571455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ypenburg C, van Bommel RJ, Delgado V, Mollema SA, Bleeker GB, Boersma E, et al. Optimal left ventricular lead position predicts reverse remodeling and survival after cardiac resynchronization therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(17):1402–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ** 30.Khan FZ, Virdee MS, Palmer CR, Pugh PJ, O'Halloran D, Elsik M, et al. Targeted Left Ventricular Lead Placement to Guide Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy: The TARGET Study: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(17):1509–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The first randomized clinical trial to demonstrate the benefit of targeted left ventricular lead placement toward non-scared site of latest activation on primary endpoint of reverse remodeling in cardiac resyncrhonization patients. In addition, improvements were observed in clinical status as secondary enpoints.

- 31.Saba S, Schwartzman D, Jain S, Adelstein D, Marek J, White P, et al. A Prospective Randomized Controlled Study Of Echocardiographic-Guided Lead Placement For Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy: Results Of The STARTER Trial. (Abstract) Heart Rhythm. 2012 Sep; In press. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tanaka H, Hara H, Saba S, Gorcsan J., 3rd Usefulness of three-dimensional speckle tracking strain to quantify dyssynchrony and the site of latest mechanical activation. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105(2):235–42. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanaka H, Tanabe M, Simon MA, Starling RC, Markham D, Thohan V, et al. Left ventricular mechanical dyssynchrony in acute onset cardiomyopathy: association of its resolution with improvements in ventricular function. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4(5):445–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bleeker GB, Kaandorp TA, Lamb HJ, Boersma E, Steendijk P, de Roos A, et al. Effect of posterolateral scar tissue on clinical and echocardiographic improvement after cardiac resynchronization therapy. Circulation. 2006;113(7):969–76. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.543678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * 35.Leyva F, Foley PW, Chalil S, Ratib K, Smith RE, Prinzen F, et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy guided by late gadolinium-enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2011;13:29. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-13-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A large group of patinets studied by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging utilizing guided left ventricualr lead implanting to avoid scarred regions and observing benefits on long term outcome.

- 36.Khan FZ, Virdee MS, Read PA, Pugh PJ, O'Halloran D, Fahey M, et al. Effect of low-amplitude two-dimensional radial strain at left ventricular pacing sites on response to cardiac resynchronization therapy. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2010;23(11):1168–76. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2010.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ** 37.Gorcsan J, 3rd, Abraham T, Agler DA, Bax JJ, Derumeaux G, Grimm RA, et al. Echocardiography for cardiac resynchronization therapy: recommendations for performance and reporting--a report from the American Society of Echocardiography Dyssynchrony Writing Group endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2008;21(3):191–213. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A review of of the technical approach and recommendations fot assesing dyssynchrony by echocardiography.

- 38.Ritter P, Padeletti L, Gillio-Meina L, Gaggini G. Determination of the optimal atrioventricular delay in DDD pacing. Comparison between echo and peak endocardial acceleration measurements. Europace. 1999;1(2):126–30. doi: 10.1053/eupc.1998.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kedia N, Ng K, Apperson-Hansen C, Wang C, Tchou P, Wilkoff BL, et al. Usefulness of atrioventricular delay optimization using Doppler assessment of mitral inflow in patients undergoing cardiac resynchronization therapy. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98(6):780–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abraham WT, Gras D, Yu CM, Guzzo L, Gupta MS. Rationale and design of a randomized clinical trial to assess the safety and efficacy of frequent optimization of cardiac resynchronization therapy: the Frequent Optimization Study Using the QuickOpt Method (FREEDOM) trial. Am Heart J. 2010;159(6):944–8. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * 41.Ellenbogen KA, Gold MR, Meyer TE, Fernndez Lozano I, Mittal S, Waggoner AD, et al. Primary results from the SmartDelay determined AV optimization: a comparison to other AV delay methods used in cardiac resynchronization therapy (SMART-AV) trial: a randomized trial comparing empirical, echocardiography-guided, and algorithmic atrioventricular delay programming in cardiac resynchronization therapy. Circulation. 2010;122(25):2660–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.992552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A randomized clinical trial demonstrating similar results of AV optimization by echocardiography, a device based algorithm, or empiric settings. Subgroup analysis revealed that only females seemed to benefit from device based or echocardiographic optimization.

- 42.Cheng A, Gold MR, Waggoner AD, Meyer TE, Seth M, Rapkin J, et al. Potential mechanisms underlying the effect of gender on response to cardiac resynchronization therapy: insights from the SMART-AV multicenter trial. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9(5):736–41. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mullens W, Grimm RA, Verga T, Dresing T, Starling RC, Wilkoff BL, et al. Insights from a cardiac resynchronization optimization clinic as part of a heart failure disease management program. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(9):765–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]