Abstract

Inflammation-mediated reactive molecules can result in an array of oxidized and halogenated DNA damage products including 5-chlorocytosine (ClC). Previous studies have shown that ClC can mimic 5-methylcytosine (mC) and act as a fraudulent epigenetic signal, promoting the methylation of previously unmethylated DNA sequences. Although the 5-halouracils are good substrates for base excision repair, no repair activity has yet been identified for ClC. Due to the apparent biochemical similarities of mC and ClC, we have investigated the effects of mC and ClC substitution on oligonucleotide structure and dynamics. In this study, we have constructed oligonucleotide duplexes containing C, ClC and mC within a CpG dinucleotide. The thermal and thermodynamic stability of these duplexes are found to be experimentally indistinguishable. Crystallographic structures of duplex oligonucleotides containing mC and ClC were determined to 1.2 and 1.9 Å, respectively. Both duplexes are B-form and are superimposable on a previously determined structure of a cytosine-containing duplex with RMSD of approximately 0.25 Å. NMR solution studies indicate that all duplexes containing cytosine or the cytosine analogs are normal B-form, and no structural perturbations are observed surrounding the site of each substitution. The magnitude of the base-stacking induced upfield shifts for non-exchangeable base proton resonances are similar for each of the duplexes examined, indicating that neither mC nor ClC significantly alter base stacking interactions. The ClC analog is paired with G in an apparently normal geometry; however the G-imino proton of the ClC-G base pair resonates to higher field relative to mC-G or C-G, indicating a weaker imino hydrogen bond. Using selective 15N-enrichment and isotope-edited NMR, we observe that the amino group of ClC rotates at roughly half the rate of the corresponding amino groups of the C-G or mC-G base pairs. The altered chemical shifts of hydrogen bonding proton resonances for the ClC-G base pair, as well as the slower rotation of the ClC amino group can be attributed to the electron-withdrawing inductive property of the 5-chloro substituent. The apparent similarity of duplexes containing mC and ClC demonstrated here is in accord with results of previous biochemical studies and further suggests that ClC is likely to be an unusually persistent form of DNA damage.

Keywords: 5-chlorocytosine, 5-methylcytosine, amino group rotation, NMR, crystallography, duplex stability, epigenetics

The development of cancer is driven by both genetic mutations and epigenetic dysregulation (1-3). While an extensive body of work has established mechanisms by which DNA damage can induce genetic mutations, substantially less is known about the relationship between DNA damage and epigenetic changes. In higher eukaryotes, the primary epigenetic mark in DNA is 5-methylcytosine (mC) which modulates the transcriptional activity of key genes primarily by altering DNA-protein interactions (4,5). In cancer cells, cytosine methylation patterns are corrupted, and frequently important tumor suppressor genes become silenced by aberrant promoter methylation (6-8). Currently, there are few clear mechanisms to explain how aberrant promoter hypermethylation occurs.

Emerging evidence indicates that inflammation-mediated reactive molecules can modify DNA, creating an additional type of endogenous DNA damage (9-11). Among the inflammation-mediated DNA adducts identified to date are the 5-halocytosines, 5-chlorocytosine (ClC) and 5-bromocytosine (BrC), and both adducts have been identified in DNA from human tissues exposed to inflammation (12-17). While most types of DNA damage have been show to interfere with enzymatic DNA methylation and with DNA-binding proteins containing a methyl-binding domain, the 5-halocytosine analogs BrC and ClC have been shown to mimic mC with respect to both DNA-binding proteins and methyltransferases (18-21). Therefore, BrC and ClC could act as fraudulent epigenetic signals, in part explaining how inflammation-mediated DNA damage could drive aberrant promoter methylation. Studies in eukaryotic cells have established that ClC in DNA can result in heritable changes in promoter methylation (22). While BrC paired with G can be repaired slowly by both MBD4 (18) and hTDG (23) glycosylases, no repair activities have yet been identified for ClC, and therefore, ClC could be a persistent form of DNA damage that would accumulate with increasing inflammation damage.

Previous studies have shown that the 5-halouracils can mimic thymine in DNA protein interactions as the sizes of the 5-Cl, Br and methyl substituents are similar (24, 25). However, as the inductive properties of the methyl substituent of thymine is electron donating and the 5-halo substituents are electron withdrawing, 5-halouracil analogs in DNA are rapidly repaired by multiple glycosylases (26, 27). We were therefore interested in understanding the impact of ClC on oligonucleotide structure and dynamics in order to reveal how ClC could serve as an excellent mimic for mC in several important biological interactions, as well as avoid surveillance and detection by DNA repair systems. In this study, we have constructed oligonucleotide duplexes containing cytosine, mC and ClC in the self-complementary Dickerson dodecamer sequence (28) within a CpG dinucleotide in one or both strands. We have studied these self-complementary duplexes in thermal melting studies, x-ray crystallography, and by 1H-NMR spectroscopy in solution to determine how mC and ClC might differentially influence duplex structure and dynamics.

Materials and methods

Synthesis and purification of oligonucleotides

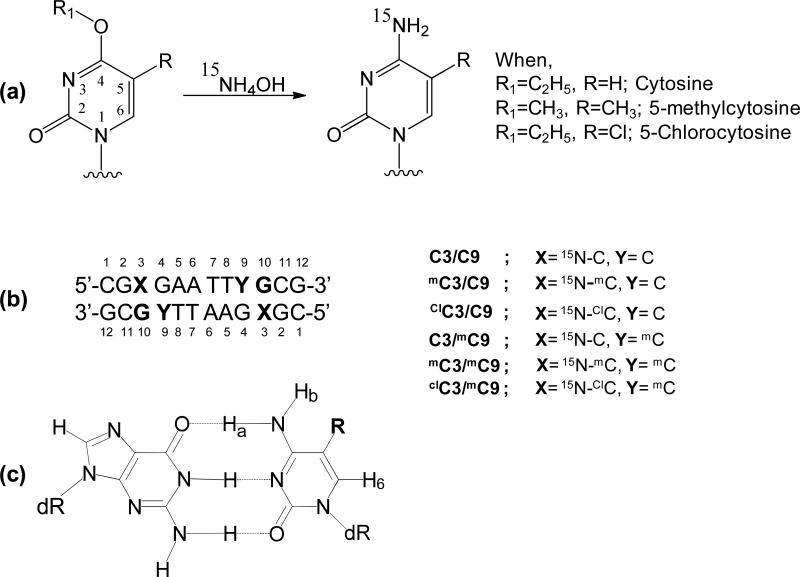

Oligonucleotides used in this study were synthesized by standard phosphoramidite solid phase methods. To prepare oligonucleotides with 5-chlorocytosine, a phosphoramidite was prepared from O4-ethyl, 5-chloro-2’-deoxyuridine as previously described (29). To prepare oligonucleotides containing 15N-enriched 4-amino groups, phosphoramidites containing O4-methyluracil (Glen research, Sterling, VA), O4-methylthymine (Glen research) and O4-ethyl-5-chlorouracil were coupled at the desired sequence position as shown in Figure 1. Oligonucleotides were then deprotected with 15N-enriched aqueous ammonia (6 N, 98%, Cambridge Isotope Labs, Andover, MA) at room temperature for 36 h as previously describe for oligonucleotides containing 5-fluorocytosine (30).

Figure 1.

(a) Reaction scheme for the synthesis of 15N labeled oligonucleotide. (b) The 12mer sequence and the oligonucleotides synthesized in this study. (c) The chemical structure of the G-C base pair. Ha is the Watson-Crick hydrogen and Hb is non-Watson-Crick hydrogen.

Oligonucleotides containing a dimethoxytrityl (DMT) group were purified by reverse phase HPLC, using a PRP column (Hamilton, Reno, NV), detritylated in 80% acetic acid at room temperature for 30 min and then repurified by HPLC using a reverse phase column. Following purification, oligonucleotides were characterized by MALDI-ToF-MS (31) and the base composition of each was examined following formic acid hydrolysis and silylation by GC/MS (Supporting Information Figure S1).

Oligonucleotide UV Melting studies

The melting temperature (Tm) and thermodynamic values of the self-complementary oligonucleotides were measured as previously described (32, 33) using a Varian Bio 300 Cary UV Vis spectrophotometer (Palo Alto, CA). Oligonucleotides at selected total-strand concentrations from 2 μM to 60 μM were dissolved in a buffer containing 100 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 10 mM sodium phosphate at pH 7. The Tm values are reported at 28 μM total strand concentration.

Crystallography

Dodecamer self-complimentary duplex oligos containing either mC or ClC at position 3 (mC3/C9 or ClC3/C9) were crystallized in solutions containing 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.0, 35-40-2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol (MPD), 5-10 mM spermine and 5-10 mM MgCl2 at 17 °C. The crystals were directly frozen in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data were collected at 100 Kelvin at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory (Argonne, IL) using synchrotron radiation. Data were processed with the HKL3000 package (HKL Research, Inc., Charlottesville, VA), and structures were determined and refined using the PHENIX program (34).

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (NMR)

Solution NMR spectra were recorder with Bruker 500 or 300 MHz NMR systems (Billerica, MA). Proton NMR spectra were obtained in solution containing 10% D2O/90% H2O 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM sodium phosphate and 0.2 mM EDTA at pH 7.0. To ensure duplex formation, oligonucleotides (200 A260 OD units, 2.5 mM) were heated at 86 °C for 2 min and slowly cooled to room temperature prior to acquisition of NMR spectra. Each spectrum was calibrated using DSS (4,4-dimetyl-4-silapentane-1-sulphonate) as an internal standard reference. Proton NMR spectra in aqueous solution were acquired with a water suppression double gradient echo WATERGATE W5 pulse program (35). The temperature of the sample was controlled by a variable temperature monitor (Eurotherm, BVT 3000). Proton resonances were assigned from 2D NOE spectra (36, 37). The 15N edited proton NMR spectra were obtained using an HSQC pulse sequence (38).

Rotational dynamics

The 15N edited proton NMR experiments were used to study the dynamics of cytosine amino group (NH2) rotation by observing the transfer of magnetization from one amino proton of the amino group to the other (39, 40). The resonance of each amino proton was selectively inverted by a rectangular soft pulse and the effect of magnetization transfer from the inverted amino proton to the other was studied. The signal intensity of both amino protons was monitored as a function of the delay time after the inversion pulse, ranging from 5 μsec to 4 sec. In the experiments described here, the magnetization of a particular amino proton at a particular time will be according to the equation 1,

| (1) |

where λ1 and λ2 are

| (2) |

and

| (3) |

M0 is the equilibrium magnetization, C and F are constant coefficients depending on the relaxation rates of the two protons. R1A and R1B are the longitudinal relaxation rates, kr is the rate of rotation, and σ is the cross relaxation rate. Values for λ1 and λ2 are obtained from the nonlinear fit of the plot of the intensity of the amino proton resonance versus delay time using equation 1. Rotation rates are obtained from λ1 and λ2 using equations 2 and 3. The cross relaxation rate (σ) is determined from the initial NOE buildup rate at lower mixing times (5-40 msec).

Quantum mechanical studies of 5-chlorocytosine

Quantum mechanical calculations (41,42) were performed with the Gaussian 03 program (Gaussian, Inc. Wallingford, CT) on a Pentium pro quad processor. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed with the 6-31G basis set (B3LYP) within the Gaussian software. The template structure of 2’-deoxycytidine (dC) was used as the initial structure. The template structure of dC was edited to create the corresponding 5-methyl and 5-chloro-2’-deoxynucleosides. Bond lengths for each molecule were obtained from the energy-minimized structures.

Results

The synthetic approach presented here yields oligonucleotides containing selected 15N-enriched cytosine amino groups. The 15N-amino groups are introduced during the final deprotection of the oligonucleotides. Therefore this is an efficient method for inserting one or more labels site-specifically in either cytosine or cytosine analogs (Figure 1). Previously, 15N-enriched cytosine amino groups have been introduced into oligonucleotides by synthesis of the 15N-enriched phosphoramidite, or by introduction of a 4-triazole phosphoramidite (43-45). As precursors for the introduction of the 5-fluorocytosine or 5-chlorocytosine, we find the O4-ethyl analogs to be suitably stable during phosphoramidite and oligonucleotide synthesis and to be quantitatively displaced by ammonia during oligonucleotide deprotection with minimal hydrolysis to the corresponding uracil analogs. Base and isotopic composition of the oligonucleotides listed in Table 1 were verified by both MALDI-ToF MS and GC/MS (Supporting Information Figure S1).

Table 1.

Tm and thermodynamic parameters for 5’-CGXGAATTYGCG-3’ in 10 mM sodium phosphate, 100 mM sodium chloride and 0.1 mM EDTA at pH 7.0. Tm values are at 28 μM total strand concentration.

| duplex | Tm (°C) | ΔH° (kcal mol−1) | ΔS° (cal mol−1K−1) | ΔG° (25 °C) (kcal mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mC3/C9 | 58.5 ± 0.5 | −61.5 ± 5.8 | −165 ± 18 | −10.8 ± 0.5 |

| mC3/mC9 | 58.7 ± 0.8 | −61.9 ± 6.1 | −166 ± 18 | −10.8 ± 0.5 |

| C3/C9 | 59.2 ± 0.1 | −58.3 ± 9.0 | −154 ± 27 | −10.7 ± 0.8 |

| C3/mC9 | 59.9 ± 0.8 | −59.3 ± 8.9 | −157 ± 27 | −10.9 ± 0.8 |

| ClC3/C9 | 58.2 ± 0.2 | −62.4 ± 10 | −168 ± 31 | −10.7 ± 0.7 |

| ClC3/mC9 | 58.9 ± 0.7 | −60.5 ± 11 | −162 ± 33 | −10.6 ± 0.7 |

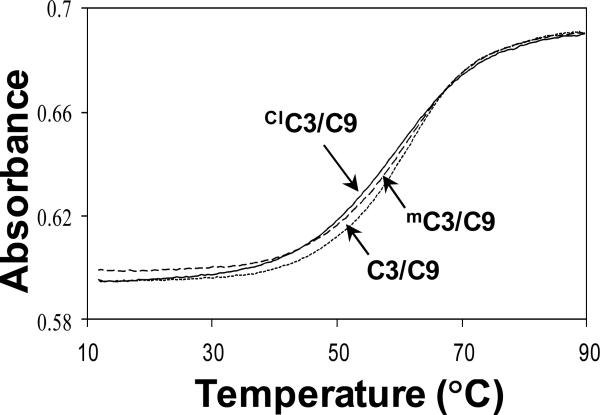

As a first approach to identify potential perturbations in oligonucleotide structure and dynamics, the thermal and thermodynamic properties of a series of oligonucleotides containing C, ClC or mC were investigated by examining duplex dissociation as a function of temperature (Figure 2). Thermodynamic parameters were obtained by fitting the experimental melting curves or from a plot of 1/Tm versus lnCt obtained at different oligonucleotide concentrations (Ct) as described previously (32, 33; Supporting Information Figure S2). The experimental values obtained in this study for the oligonucleotides shown in Figure 1 are listed in Table 1. The experimental Tm values obtained in this study are close to the value of 59 °C predicted for the cytosine-containing duplex based upon the nearest-neighbor model of SantaLucia et al. (46). In thermal melting studies, Tm's can be measured reproducibly to within 0.5 ° C. In the sequences studied here containing one modified cytosine analog and either cytosine or mC in the opposing strand of the CpG dinucleotide, observed melting temperatures for the ClC and mC duplexes are experimentally indistinguishable (Figure 2). Therefore, in the sequences studied here, both mC and ClC have no measurable impact on duplex thermal stability.

Figure 2.

Normalized melting profiles at 260 nm of 28 μM oligonucleotides in presence of 10 mM sodium phosphate, 100 mM sodium chloride, 0.1 mM EDTA at pH 7.0.

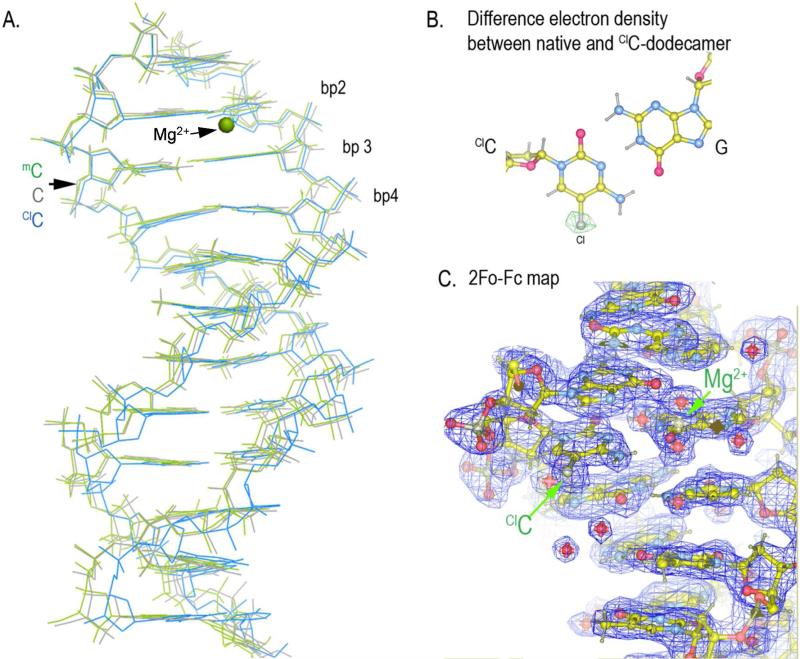

In order to determine the comparative impact of C, mC and ClC on duplex structure, oligonucleotide duplexes were studied by x-ray crystallography and by NMR spectroscopy in aqueous solution. The crystal structure of a duplex containing mC was determined to 1.2 Å and refined to an R-factor of 0.249 (Rfree = 0.278) by the molecular replacement method using an unmodified Dickerson-Drew dodecamer (pdb accession number: 1FQ2). The structure of the ClC-containing duplex was determined using the same method to 1.9 Å, and refined to an R-factor of 0.195 (Rfree=0.262) (Supporting Information Table S1). The mC and ClC structures closely resemble each other, with an RMSD 0.25 Å. Both duplexes adopt a B-form DNA configuration, with RMSD 0.22 and 0.23 Å relative to the Dickerson-Drew duplex containing cytosine (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Structure of the Dickerson-Drew dodecamer with a modified base at position 3. A) Superposition of mC (green) and ClC (blue) containing duplex with native C dodecamer (gray). B) Difference map between the ClC and C dodecamers (FoClC-FcC, ΦClC ) revealing electron density around Cl on ClC at position 3. C) Electron density (2Fo-Fc) for the ClC-containing dodecamer. Fo is the observed electron density map and Fc is the calculated electron density map. The structure factors and coordinates of the ClC and mC-containing dodecamers are deposited to Protein Data Bank with accession number 4MGW and 4MKW, respectively.

A more detailed comparative structural analysis was performed on each duplex examined here using the program CURVES+ (47) and the corresponding crystallographic PDB files as input. The CURVES+ program can reveal more subtle differences in the orientation of the base pair axis (BP-axis), base rotation and translation as well as other helical parameters. Data obtained with the CURVES+ program is tabulated in Supplementary Table S2 in which values for each modified base pair as well as average values for all base pairs in each duplex. Differences among the cytosine, ClC and mC duplexes are modest, and usually the values for the ClC and mC duplexes are more similar to one another that to the cytosine-containing oligonucleotide.

NMR studies in aqueous solution were performed to examine potential dynamic influences of each substitution. The aromatic base and H1’ sugar residues for each duplex were observed and assigned by standard two-dimensional NMR methods (Supporting Information Figure S3). Chemical shifts are tabulated in Supporting Information Table S3 and Table S4. The observed NOE connectivities are consistent with a predominantly B-form helix in which all of the bases are intrahelical (Supporting Information Figure S4). Significant differences are noted for the chemical shifts of the H6 protons for C, mC and ClC in each of the duplexes examined. In order to determine the effect of the 5-substituent on the chemical shift of the H6 proton, NMR spectra were also recorded for the corresponding free 2’-deoxynucleosides in D2O (Supporting Information Table S5).

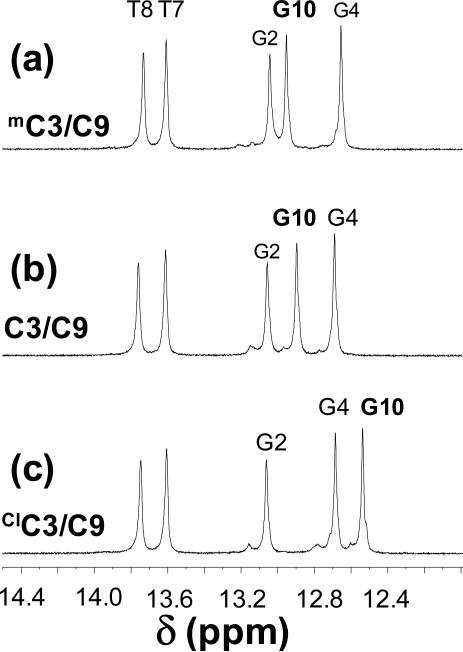

The proton NMR spectrum of the exchangeable proton region for each duplex at 300 K showed five imino proton resonances for these symmetric 12-base duplexes (Figure 4). The imino protons of the terminal base pairs are exchange-broadened under these conditions and are not observable. However, the terminal imino protons are observed at lower temperature (Supporting Information Figure S5). For the three duplexes containing C, mC or ClC at position 3, the imino region is essentially the same, with one exception. The chemical shift of the imino proton of G10, paired with the C or substituted C at position 3 is different in each spectrum, ranging from 12.95 ppm when paired with mC to 12.54 ppm when paired with ClC. A similar trend was observed in duplexes containing mC in the opposing strand (Supporting Information Table S6).

Figure 4.

1H NMR spectra in the imino region of the [4-15N] labeled (X3 position, Figure 1) oligonucleotides (a) mC3/C9, (b) C3/C9 and (c) ClC3/C9 in the presence of 10% D2O, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM sodium phosphate and 0.2 mM EDTA at pH 7 and 300K.

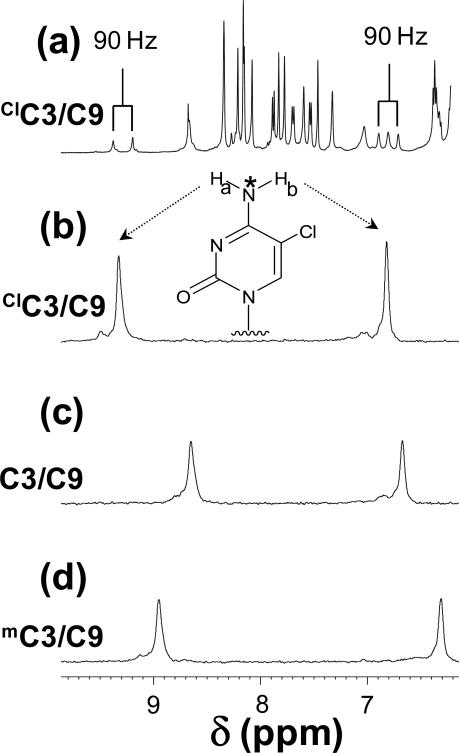

The amino protons of the cytosine residues are observed in a spectrally crowded region between 6 and 9.5 ppm (Figure 5). The amino proton hydrogen-bonded to the G residue is shifted downfield relative to the non-hydrogen bonded amino proton. In order to directly observe the amino protons of the cytosine residue at oligonucleotide position 3, the nitrogen of the amino groups was 15N enriched. Selective enrichment permits direct observation of the J-coupled amino protons as shown in Figure 5a. The amino resonances observed in 15N-decoupled spectra are shown in Figure 5b-d. The observed imino and amino proton resonances indicate that G pairs with mC and ClC in a hydrogen-bonding pattern similar to the Watson-Crick C-G base pair.

Figure 5.

(a) 1H NMR spectrum (unedited) of the [4-15N] ClC3/C9 oligo. (b-d) 15N edited proton spectrum of 15N labelled oligonucleotides in the presence of 10% D2O, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM sodium phosphate and 0.2 mM EDTA at pH 7 and 300K. 15N label is indicated in the structure by the asterisk.

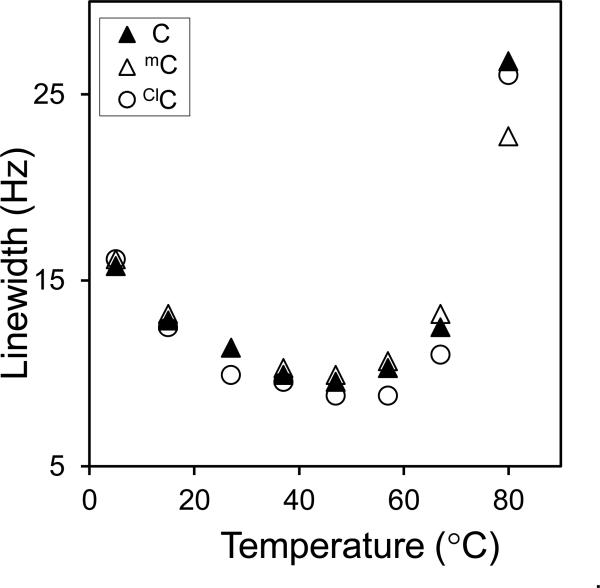

In order to examine the dynamics of the target cytosine residue at position 3, the rotation rate of the amino group was measured by the saturation-transfer method described in the Experimental Section and shown in Supporting Information Figures S6 and S7. The rotational rates of C, mC and ClC in the corresponding oligonucleotides are 32.9, 33.4 and 12.7 sec−1 respectively (Table 2). The placement of a mC residue in the opposing strand had minimal impact on the amino group rotation rate (Table 2), and in both sequence contexts, the amino group of the ClC residue rotates at approximately half the rate of the corresponding mC residue. The linewidth of the G-imino proton of the X3-G10 bases pair was also measured as a function of temperature. For the three duplexes examined here, the temperature dependence of the G-imino proton resonance linewidth overlapped substantially as shown in Figure 6.

Table 2.

Amino proton chemical shifts, rate of rotation of amino protons and line widths amino resonances of the 3rd base of the oligonucleotide (Figure 1) at 300 K and pH 7. Rate of rotation (kr) determined by 15N edited magnetization transfer experiments and line widths (half height width) using 15N edited experiments. Δδa = Ha-monomer Ha and Δδb =Hb-monomer Hb.

| duplex | kr (sec−1) | Chemical shifts of C3 amino protons in oligos | Line width (Hz) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NH2 Ha | NH2 Hb | Δδ (Ha-Hb) | Δδa | Δδb | Ha | Hb | ||

| mC3/C9 | 33.4 | 8.95 | 6.31 | 2.64 | 2.06 | −0.58 | 31.9 | 26.8 |

| mC3/mC9 | 36.9 | 9.00 | 6.23 | 2.77 | 2.11 | −0.66 | 34.1 | 28.6 |

| C3/C9 | 32.9 | 8.65 | 6.68 | 1.97 | 1.89 | −0.56 | 33.0 | 25.7 |

| C3/mC9 | 33.8 | 8.68 | 6.59 | 2.09 | 1.92 | −0.65 | 33.7 | 28.6 |

| ClC3/C9 | 12.7 | 9.31 | 6.81 | 2.50 | 1.95 | −0.43 | 26.8 | 21.6 |

| ClC3/mC9 | 14.1 | 9.38 | 6.74 | 2.64 | 2.02 | −0.50 | 25.3 | 22.4 |

Figure 6.

Temperature dependent line width studies of G10 imino protons of C3/C9, mC3/C9 and ClC3/C9 oligonucleotide in the presence of 10% D2O, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM sodium phosphate and 0.2 mM EDTA at pH 7 and 300K.

Discussion

A. Substitution with ClC does not alter duplex stability as measured in thermal melting studies

In this study, a total of six symmetric oligonucleotides forming six duplexes were studied. Each oligonucleotide contained mC, C or ClC at position X3 (Figure 1b). Three of the duplexes contained C at position Y9 (Figure 1b), while three contained mC at position Y9. In eukaryotic DNA, mC is usually found in symmetrically methylated mCpG dinucleotides, however, mC can also be found in hemimethylated CpG dinucleotides following DNA replication prior to maintenance methylation (20). Oligonucleotide melting temperatures are measured by observing optical absorbance as a function of temperature (Figure 2). Thermodynamic parameters are extracted from the melting studies either by curve-fitting or by measuring melting temperature as a function of oligonucleotide concentration (32,33) and differences obtained with each method were at or below experimental error. The thermal and thermodynamic parameters for duplex dissociation are given in Table 1. In the duplexes examined here, changes in duplex melting temperature resulting from the replacement of C by mC or ClC were at or below the experimental error. Similarly, thermodynamic differences were at or below experimental error. Therefore, the replacement of mC by ClC has little or no observable impact on the thermal or thermodynamic stability of an oligonucleotide duplex, at least within the sequence examined here. Previous studies have shown that cytosine methylation generally increases oligonucleotide melting temperatures, however, the increase is modest and sequence-dependent (48, 49).

B. The crystal structures of the C, mC and ClC duplexes are superimposable

The duplex structures of the ClC3/C9 and mC3/C9 oligonucleotides were examined by crystallography and compared with the native Dickerson dodecamer (C3/C9). All the duplexes form typical B-form geometry. The ClC or mC substitution in position 3 of the sequence had negligible effect upon the structures (Figure 3). Consistent with our findings, previous studies have shown that the 5-bromocytosine within the same sequence context is also B-form and is isomorphous to the native structure (28). Oligonucleotides containing 5-methylcytosine or 5-bromocytosine have been shown to promote alternative A or Z forms depending on the sequence context (50), however, these alternative forms require unusual DNA sequences.

C. Examination of non-exchangeable protons reveals the similarity of the ClC and mC duplexes

Upon duplex formation, the solution 1H-NMR chemical shifts of non-exchangeable protons are observed to move upfield relative to monomer chemical shifts due to base-base stacking interactions. In the duplex, the non-exchangeable resonances can be assigned by sequential NOE connectivities (36, 37) as shown and tabulated in Supporting Information (Table S3 and S4). The observed non-exchangeable base proton-H1’ connectivities indicate that all duplexes studied here are predominantly B-form and that all bases are intrahelical.

The magnitudes of the upfield shifts of the non-exchangeable resonances are proportional to the degree of base-stacking interactions and are sensitive indicators of base geometry within the duplex. With one exception, the chemical shifts of the non-exchangeable aromatic proton resonances are invariant among the duplexes containing mC, C and ClC at position X3 when Y9 is C or mC (Supporting Information Figure S3). The single exception in each case is the chemical shift of the H6 proton of the mC, C or ClC residue at position X3 where these resonances are observed at 7.04, 7.25 and 7.54-7.55 ppm, respectively where Y9 is either C or mC. The observed chemical shift of the H6 resonance in a duplex is dependent upon both the intrinsic chemical shift of the proton resonance and the base-stacking change resulting from duplex formation. In pyrimidine analogs, a 5-substituent can significantly alter the chemical shift of H6, with electron donating substituents such as CH3 moving the chemical shift to higher field, and electron withdrawing substituents shifting in the opposing direction. The chemical shifts of the H6 proton for the corresponding 2’-deoxynucleosides in water at 300K are 7.64, 7.81 and 8.11 ppm, for mdC, dC and CldC, respectively. The stacking-induced shifts in the sequence examined here are observed to be 0.60, 0.56 and 0.56 for mC, C and ClC, respectively, and therefore the observed H6 chemical shift differences among the duplexes examined are dominated by the 5-substituent effect on the intrinsic chemical shift of the corresponding H6 proton. The similarity in the base-stacking induced change in the H6 chemical shift across the duplexes examined here is consistent with a negligible effect of ClC substitution on duplex stability or conformation.

D. Examination of exchangeable protons resonances reveals differences between the duplexes

Upon duplex formation, the resonances of exchangeable amino and imino protons become narrower and shift downfield due to the formation of hydrogen bonds with bases in the complementary strand. The imino proton regions of duplexes containing mC, C and ClC with C at position Y9 are shown in Figure 4. With the exception of the chemical shift of the G10 resonance of the X3-G10 base pair, the spectra are largely indistinguishable. The G10 imino proton from the ClC-G base pair is to high field of the other G imino protons, but well within the range expected for a normal Watson-Crick base pair.

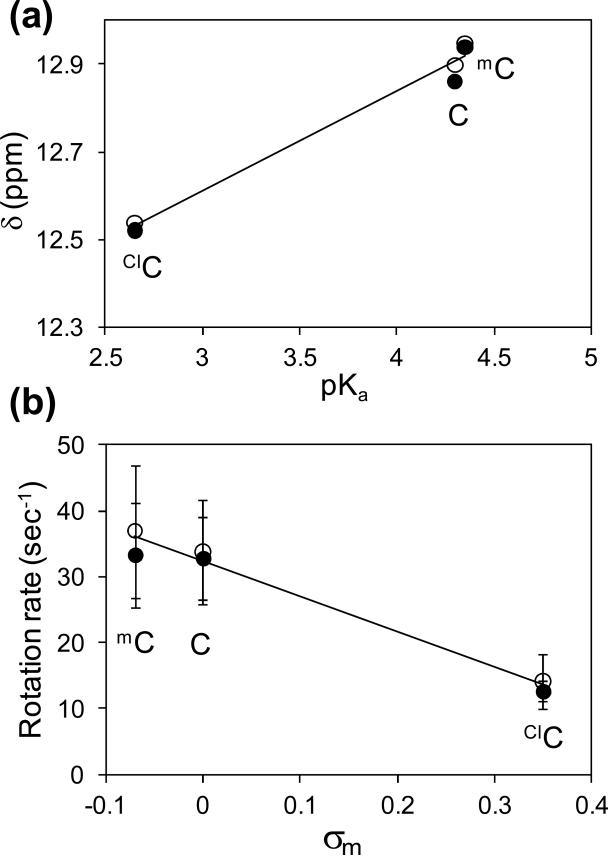

A substituent in the 5-position of the cytosine ring can influence the basicity of the N3 position which is the hydrogen bond acceptor for the G10 imino proton. The pKa of the N3 position of dC is 4.2, and an electron donating CH3 substituent in the 5-position increases the pKa to 4.3 (30). In contrast, an electron withdrawing Cl substituent decreases the pKa of CldC to 2.7 (30). In Figure 7a, the G10 chemical shift is plotted versus the pKa of the paired cytosine or cytosine analog, and a linear relationship is observed. The presence of a cytosine 5-substituent has an observable effect upon the G-C imino hydrogen bond which is proportional to the substituent effect on the corresponding N3 pKa value.

Figure 7.

(a) Proton chemical shifts of the G imino protons of the X3-G10 base pair of the oligonucleotide versus the pKa of the corresponding nucleoside at pH 7, where X3 is mC, C or ClC. (b) Amino group rotation rate as a function of the Hammett σm parameter of the 5-substituent. Closed circles are for the X3/C9 oligo whereas open circles are for the X3/mC9 oligo.

The dynamics of the base pair formed between X3 and G10 can also be investigated by examining the linewidth of the G10 imino resonance as a function of temperature. The G10 imino proton linewidths for duplexes containing mC, C and ClC are shown in Figure 6. As the temperature is increased from 5°C, the linewidth for each duplex decreases and then increases due to enhanced base pair opening and proton exchange with solvent. However, the linewidths for the three duplexes are very similar and appear to converge around physiological temperature. These data suggest that although the presence of ClC decreases the strength of the imino hydrogen bond with G10, the ClC-G base pair is held intact by base-stacking interactions and does not open with greater frequency than the corresponding base pairs with C or mC, consistent with the thermodynamic results presented above.

The strength of the hydrogen bond can also be estimated by the downfield shift of the imino proton within the oligonucleotide relative to its monomer value. The intrinsic chemical shift of the imino proton of the 2’-deoxyguanosine nucleoside is 10.59 ppm (in DMSO) whereas the chemical shifts of guanine imino protons (G10) in C-G, mC-G and in ClC-G base pairs are 12.90, 12.95 and 12.54 ppm respectively for the C3/C9, mC3/C9, ClC3/C9 oligonucleotides. The difference in chemical shift between the oligo and corresponding nucleoside are 2.31, 2.36 and 1.95 ppm for the C3/C9, mC3/C9 and ClC3/C9 oligonucleotides which indicates that the mC3-G10 base pair has the strongest hydrogen bond whereas the ClC3-G10 base pair has the weakest. Similar relative magnitudes of base-pairing induced shifts were observed for oligonucleotides in which mC was placed in the opposing strand.

The dynamics of the base pairs formed between G10 and mC, C and ClC can also be examined by observation of the amino protons of the paired cytosine or cytosine analog. The amino protons of cytosine analogs rotate at a relatively slow rate on the NMR time scale and can be observed as separate resonances. With monomeric 2’-deoxycytidine (dC) in solution, the hydrogen-bonding Ha or Watson-Crick (WC) proton is exchange-broadened and to high field of the non-hydrogen bonding, non-Watson Crick (nWC) proton, Hb (Figure 1c). With mdC, both amino protons are coincident, however, with CldC, the WC proton Ha is to low field of the nWC proton Hb (Supporting Information Table S5). Within the dC series, a 5-substituent has a much greater effect upon the chemical shift of the nWC proton. When comparing the linewidth of the Ha and Hb protons of dC and CldC at 5°C, the Ha proton is broader than Hb in all cases. The linewidths of the Ha protons for dC and CldC are 33.4 Hz versus 29.2 Hz, respectively, however, the linewidth of CldC Hb is only 13.1 Hz whereas Hb for dC is 23.0 Hz. The line widths for the mdC (monomer) amino protons couldn't be determined because of resonance overlap. The observed linewidth is a function of both chemical exchange with solvent and rotational line broadening. The data reported here suggest that in the monomers, dC and CldC, the rates of chemical exchange are similar (Ha). However, the narrower linewidth of Hb for CldC indicates that the amino group is rotating more slowly relative to dC.

The amino resonances of 15N-isotope-enriched mC, C and ClC within duplex oligonucleotides were edited from a crowded spectral region and assigned as shown in Figure 5. In each duplex, the Ha proton moves considerably downfield due to hydrogen bond formation with the O6 position of G10 and becomes substantially narrower whereas the Hb proton moves slightly upfield due to base-stacking interactions. The magnitude of the hydrogen-bonding induced change in Ha chemical shift for mC, C and ClC are 2.06, 1.89 and 1.95 ppm whereas the corresponding changes for the mC9 oligos are 2.11, 1.92 and 2.02 ppm. These data confirm the formation of a base pair between ClC and G10 that approximates Watson-Crick geometry.

The rate of rotation of an amino group can be studied by using magnetization transfer as demonstrated previously by Russu and coworkers (39, 40), and values obtained with these methods are given in Table 2. The rotation rate of the mC amino group (X3 = mC) is approximately 33 sec−1, when Y9 is C and 37 sec−1 when Y9 is mC. In the C-containing duplex (X3 = C) the amino group rotation rate is approximately 33 sec−1 when Y9 is either C or mC. In contrast, the apparent rate of the ClC amino group (X3 = ClC) is 12.7 sec−1 (Y9 = C) but increases to 14.1 sec−1 when mC is in the opposing strand (Y9 = mC). The temperature-dependent linewidth analysis shows that the labeled amino resonance of the ClC3/C9 oligonucleotide broadens slower than those in the C3/C9 or mC3/C9 oligonucleotides which indicates that the ClC amino group rotates more slowly (Supporting Information Figure S8).

The reduced rate of rotation of the amino group of ClC relative to C or mC could be attributed to a reduced rate of base pair opening or to a slower intrinsic rotation rate resulting from the 5-chloro substituent. A previous study has shown that the C4-N4 bond of cytosine and its analogs have considerable double-bond character (41), consistent with its slow amino group rotation rate relative to adenine and guanine analogs. We investigated the geometry of the mdC, dC and CldC monomers through DFT calculations performed with the 6-31G basis set (B3LYP). The C4-N4 bond lengths of mdC, dC, CldC are found to be 1.363, 1.364 and 1.355 Å respectively. The reduced C4-N4 bond length of CldC is consistent with more double bond character, and would result in a reduced rate of amino group rotation, as observed in studies with the monomers discussed above.

Consistent with the computational results discussed above, the rate of rotation of the cytosine amino group in the duplexes examined here is related to the electronic inductive property of the 5-substituent. A linear relationship (Figure 7b) is obtained when the amino group rotation rate is plotted versus the Hammett parameter (σm) for mC, C and ClC. The Hammett parameters for the selected substituents are obtained from Hansch et al. (51). The methyl group of mC is electron donating whereas the Cl substituent of ClC is electron withdrawing. Therefore, the slower rotation rate of the ClC amino group in the duplex can be attributed primarily to the electronic-inductive effect of the 5-Cl substituent.

E. Summary and conclusions

A series of oligonucleotide duplexes were constructed containing mC, C, and ClC with either C or mC in the opposing strand within a CpG dinucleotide. Optical melting studies indicate that the replacement of C or mC with ClC does not alter observably duplex thermal or thermodynamic stability. Results of crystallographic and 1H-NMR studies establish that the overall geometries of the ClC-containing duplexes are normal, B-form and that the base pair formed between ClC and G approximates Watson-Crick geometry. A correlation is observed between the chemical shift of the imino proton of the G residue and the pKa of the N3 position of the paired cytosine analog for the series mC, C and ClC, suggesting that the electron-withdrawing 5-chloro substituent, which reduces the pKa of the N3 position, proportionately decreases the strength of the G-ClC imino hydrogen bond. Despite an apparently reduced imino hydrogen bond strength, the G imino proton of the G-ClC base pair is not unusually broadened with increasing temperature, suggesting that the local base-stacking, which is unchanged by ClC substitution, is sufficient to maintain the base pair in a predominantly closed state. The Ha amino proton of ClC forms a hydrogen bond with the O6 position of the paired G residue, and the ClC amino group rotates at approximately half the rate of the C or mC amino groups. The reduced rate of amino group rotation is attributed to the 5-chloro substituent increasing the double-bond character of the C4-N4 bond of ClC as opposed to slowing the rate of base pair opening. These results are in accord with previous biochemical findings that ClC is a very good mimic for mC and that it can act as a fraudulent epigenetic signal. Prior studies on DNA damage recognition have shown that glycosylases of the base-excision repair pathway can exploit structural and thermodynamic perturbations of damaged base pairs in distinguishing modified and normal bases in DNA (27, 52, 53). The apparent structural and dynamic similarities between ClC and mC oligonucleotides shown here are in accord with the reported inability of glycosylases to recognize and remove ClC from DNA. Therefore, the formation of ClC in DNA poses a significant challenge for base excision repair and ClC is likely to accumulate in DNA over time as a function of inflammation exposure and might in part explain the established relationship between inflammation and cancer development (54, 55).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by grant CA50351 from National Cancer Institute; GM083703 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and Welch Foundation (H-1592). We are grateful to the generous endowment from the Sealy and Smith Foundation to Sealy Center for Structural Biology at University of Texas Medical Branch. We thank Christie Shumate for crystallization of the DNA duplexes, as well as the support of staff of SBC ID19 at APS, Argonne National Laboratory. The structure factors and coordinates of the ClC and mC-containing dodecamers are deposited to Protein Data Bank with accession number 4MGW and 4MKW, respectively. We thank Christopher Perry and Jonathan Neidigh (Loma Linda University) for helps in quantum mechanical calculations and NMR experiments respectively.

Abbreviations

- mC

5-methylcystosine

- ClC

5-chlorocytosine

- BrC

5-bromocytosine

- HOCl

hypochlorous acid

- Tm

melting temperature

- MALDI-ToF-MS

Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization -Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry

- GC/MS

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- NOE

Nuclear Overhauser effect

Footnotes

This work was supported by grant CA50351 from National Cancer Institute; GM083703 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the Welch Foundation (H-1592).

Dedication: “This manuscript is dedicated to the fond memory of Victor Fung, Ph.D., a former Program Officer at NCI and former Scientific Review Officer of the Cancer Etiology study section of CSR, NIH, for his wisdom, compassion, integrity, his love of sciences and the arts, his incredible culinary skills, and above all, his contributions to the career development of so many investigators during his own distinguished career.”

Supporting Information Available: Crystallographic data collection and refinement statistics of the oligonucleotide mC3/C9 and ClC3/C9 (Table S1); Helicoid analyses of Dickerson-Drew dodecamers containing mC or ClC at position 3 (mC3/C9 and ClC3/C9) (Table S2); Chemical shifts of the selected non exchangeable protons of the oligonucleotides (Table S3 and Table S4); Chemical shifts and line width of amino protons of the nucleosides in 10% D2O and 5 °C (Table S5); Chemical shift of imino protons of the oligonucleotides (Table S6); Characterization of the ClC3/C9 oligonucleotide by GC-MS and MALDI ToF (Figure S1); 1/Tm versus ln(Ct) plot for the mC3/C9 oligonucleotide (Figure S2); 1D proton spectra of the aromatic region of the oligonucleotides (Figure S3); 2D NOE of ClC3/C9 oligonucleotide with H6-H1’ connectivity (Figure S4); Temperature dependent proton spectra in the imino region of ClC3/C9 oligonucleotide (Figure S5); Magnetization transfer experiment of amino protons ClC3/C9 oligo (Figure S6); Nonlinear curve fitting from magnetization transfer experiments of ClC3/C9 oligo (Figure S7); Line widths of amino protons of C3/C9, mC3/C9 and ClC3/C9 oligonucleotide as a function of temperature(Figure S8); This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Sandoval J, Esteller M. Cancer epigenomics: beyond genomics. Curr. Opin. Dev. 2012;22:50–55. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.You JS, Jones PA. Cancer genetics and epigenetics: two sides of the same coin. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shen H, Laird PW. Interplay between the cancer genome and epigenome. Cell. 2013;153:38–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bird AP, Wolffe AP. Methylation-induced repression—belts, braces, and chromatin. Cell. 1999;99:451–454. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81532-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valinluck V, Tsai HH, Rogstad DK, Burdzy A, Bird A, Sowers LC. Oxidative damage to methyl-CpG sequences inhibits the binding of the methyl-CpG binding domain (MBD) of methyl-CpG binding protein 2 (MECP2) Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:4100–4108. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones PA, Baylin SB. The epigenomics of cancer. Cell. 2007;128:683–692. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCabe MT, Brandes JC, Vertino PM. Cancer DNA methylation: molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009;15:3927–3937. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kanwal R, Gupta S. Epigenetic modifications in cancer. Clin. Genet. 2012;81:303–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01809.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis JG, Adams DO. Inflammation, oxidative DNA damage, and Carcinogenesis. Environ. Health Perspect. 1987;76:19–27. doi: 10.1289/ehp.877619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ames BN, Gold LS, Willett WC. The causes and prevention of cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1995;92:5258–5265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lonkar P, Dedon PC. Reactive species and DNA damage in chronic inflammation: reconciling chemical mechanisms and biological fates. Int. J. Cancer. 2011;128:1999–2009. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whiteman M, Jenner A, Halliwell B. Hypochlorous acid-induced base modifications in isolated calf thymus DNA. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1997;10:1240–1246. doi: 10.1021/tx970086i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winterbourn CC, Kettle AJ. Biomarkers of myeloperoxidase-derived hypochlorous acid. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2000;29:403–409. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00204-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Badouard C, Masuda M, Nishino H, Cadet J, Favier A, Ravanat JL. Detection of chlorinated DNA and RNA nucleosides by HPLC coupled to tandem mass spectrometry as potential biomarkers of inflammation. J. Chromatogr B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2005;827:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2005.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang JI, Sowers LC. Examination of hypochlorous acid-induced damage to cytosine residues in a CpG dinucleotide in DNA. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2008;21:1211–1218. doi: 10.1021/tx800037h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mangerich A, Knutson CG, Parry NM, Muthupalani S, Ye W, Prestwich E, Cui L, McFaline JL, Mobley M, Ge Z, Taghizadeh K, Wishnok JS, Wogan GN, Fox JG, Tannenbaum SR, Dedon PC. Infection-induced colitis in mice causes dynamic and tissue-specific changes in stress response and DNA damage leading to colon cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2012;109:E1820–1829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207829109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seiberling KA, Chruch CA, Herring J, Sowers LC. Epigenetics of chronic rhinosinusitis and the role of the eosinophil. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2012;2:80–84. doi: 10.1002/alr.20090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valinluck V, Liu P, Kang JI, Jr., Burdzy A, Sowers LC. 5-halogenated pyrimidine lesions within a CpG sequence context mimic 5-methylcytosine by enhancing the binding of the methyl-CpG-binding domain of methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MeCP2) Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:3057–3064. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lao VV, Darwanto A, Sowers LC. Impact of base analogues within a CpG dinucleotide on the binding of DNA by the methyl-binding domain of MeCP2 and methylation by DNMT1. Biochemistry. 2010;49:10228–10236. doi: 10.1021/bi1011942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valinluck V, Sowers LC. Endogenous cytosine damage products alter the site selectivity of human DNA maintenance methyltransferase DNMT1. Cancer Res. 2007;67:946–950. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valinluck V, Sowers LC. Inflammation-mediated cytosine damage: a mechanistic link between inflammation and the epigenetic alterations in human cancers. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5583–5586. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lao VV, Herring JL, Kim CH, Darwanto A, Soto U, Sowers LC. Incorporation of 5-chlorocytosine into mammalian DNA results in heritable gene silencing and altered cytosine methylation patterns. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:886–893. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bennett MT, Rodgers MT, Hebert AS, Ruslander LE, Eisele L, Drohat AC. Specificity of human thymine DNA glycosylase depends on N-glycosidic bond stability. J. Am .Chem. Soc. 2006;128:12510–12519. doi: 10.1021/ja0634829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brennan CA, Van Cleve MD, Gumport RI. The effects of base analog substitutions on the cleavage by the EcoR1 restriction endonuclease of octadeoxyribonucleotides containing modified Eco R1 recognition sequences. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:7270–7278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brennan CA, Van Cleve MD, Gumport RI. The effects of base analog substitutions on the methylation by the EcoR1 modification methylase of octadeoxyribonucleotides containing modified Eco R1 recognition sequences. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:7279–7286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu P, Burdzy A, Sowers LC. Substrate Recognition by a Family of Uracil-DNA Glycosylases: UNG, MUG, and TDG. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2002;15:1001–1009. doi: 10.1021/tx020030a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Darwanto A, Theruvathu JA, Sowers JL, Pascal T, Goddard W, 3rd, Sowers LC. Mechanism of base selection by human single-stranded selective monofunctional uracil-DNA glycosylase. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:15835–15846. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807846200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fratini AV, Kopka ML, Drew HR, Dickerson RE. Reversible bending and helix geometry in a B-DNA dodecamer: CGCGAATTBrCGCG. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:14686–14707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kang JI, Jr., Burdzy A, Liu P, Sowers LC. Synthesis and characterization of oligonucleotides containing 5-chlorocytosine. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2004;17:1236–1244. doi: 10.1021/tx0498962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sowers LC. 15N-enriched 5-fluorocytosine as a probe for examining unusual DNA structures. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2000;17:713–723. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2000.10506561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cui Z, Theruvathu JA, Farrel A, Burdzy A, Sowers LC. Characterization of synthetic oligonucleotides containing biologically important modified bases by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Anal. Biochem. 2008;379:196–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2008.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Theruvathu JA, Kim CH, Rogstad DK, Neidigh JW, Sowers LC. Base pairing configuration and stability of an oligonucleotide duplex containing a 5-chlorouracil-adenine base pair. Biochemistry. 2009;48:7539–7546. doi: 10.1021/bi9007947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Theruvathu JA, Kim CH, Darwanto A, Neidigh JW, Sowers LC. pH-Dependent configurations of a 5-chlorouracil-guanine base pair. Biochemistry. 2009;48:11312–11318. doi: 10.1021/bi901154t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkóczi GV, Chen B, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung L-W, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner RJ, Read, Richardson DD, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Cryst. 2010;D66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu M, Mao X, Ye C, Huang H, Nicholson JK, Lindon JC. Improved WATERGATE Pulse Sequences for Solvent Suppression in NMR Spectroscopy. J. Magn. Reson. 1998;132:125–129. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hare DR, Wemmer DE, Chou SH, Drobny G, Reid BR. Assignment of the non-exchangeable proton resonances of d(C-G-C-G-A-A-T-T-C-G-C-G) using two-dimensional nuclear magnetic resonance methods. J. Mol. Biol. 1983;171:319–336. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(83)90096-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weiss MA, Patel DJ, Sauer RT, Karplus M. Two-dimensional 1H NMR study of the lambda operator site OL1: a sequential assignment strategy and its application. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1984;81:130–134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.1.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grzesiek S, Bax A. The importance of not saturating water in protein NMR. Application to sensitivity enhancement and NOE measurements. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:12593–12594. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Michalczyk R, Russu IM. Rotational dynamics of adenine amino groups in a DNA double helix. Biophys. J. 1999;76:2679–2686. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77420-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiang L, Russu IM. Internal dynamics in a DNA triple helix probed by (1)H-(15)N-NMR spectroscopy. Biophys. J. 2002;82:3181–3185. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75660-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moser A, Guza R, Tretyakova N, York DM. Density Functional Study of the Influence of C5 Cytosine Substitution in Base Pairs with Guanine. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2009;122:179–188. doi: 10.1007/s00214-008-0497-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Montgomery JA, Jr., Vreven T, Kudin KN, Burant JC, Millam JM, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Barone V, Mennucci B, Cossi M, Scalmani G, Rega N, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Klene M, Li X, Knox JE, Hratchian HP, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Ayala PY, Morokuma K, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Zakrzewski VG, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Strain MC, Farkas O, Malick DK, Rabuck AD, Raghavachari K, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cui Q, Baboul AG, Clifford S, Cioslowski J, Stefanov BB, Liu G, Liashenko A, Piskorz P, Komaromi I, Martin RL, Fox DJ, Keith T, Al-Laham MA, Peng CY, Nanayakkara A, Challacombe M, Gill PMW, Johnson B, Chen W, Wong MW, Gonzalez C, Pople JA. Gaussian 03, revision A.1 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kupferschmitt G, Schmidt J, Schmidt T, Fera B, Buck F, Ruterjans H. 15N labeling of oligodeoxynucleotides for NMR studies of DNA-ligand interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:6225–6241. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.15.6225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramesh V, Xu YZ, Roberts GC. Site-specific 15N-labelling of oligonucleotides for NMR: the trp operator and its interaction with the trp repressor. FEBS Lett. 1995;363:61–64. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00226-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Acedo M, Fabrega C, Avino A, Goodman M, Fagan P, Wemmer D, Eritja R. A simple method for N-15 labeling of exocyclic amino groups in synthetic oligodeoxynucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:2982–2989. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.15.2982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.SantaLucia J, Jr., Allawi HT, Seneviratne PA. Improved nearest-neighbor parameters for predicting DNA duplex stability. Biochemistry. 1996;35:3555–3562. doi: 10.1021/bi951907q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lavery R, Moakher M, Maddocks JH, Petkeviciute D, Zakrzewska K. Conformational analysis of nucleic acids revisited: Curves+. Nucleic Acids Research. 2009;37:5917–5929. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sowers LC, Shaw BR, Sedwick WD. Base Stacking and Molecular Polarizability: Effect of a Methyl Group in the 5-Position of Pyrimidines. Biochem. Biophys. Research Commun. 1987;148:790–794. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)90945-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lefebvre A, Mauffret O, el Antri S, Monnot M, Lescot E, Fermandjian S. Sequence dependent effects of CpG cytosine methylation. A joint 1H-NMR and 31P-NMR study. Eur. J. Biochem. 1995;229:445–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.0445k.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fujii S, Wang AH, van der Marel G, van Boom JH, Rich A. Molecular structure of (m5 dC-dG)3: the role of the methyl group on 5-methyl cytosine in stabilizing Z-DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1982;10:7879–7892. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.23.7879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hansch C, Leo A, Taft RW. A Survey of Hammett substituent constants and resonance and field parameters. Chem. Rev. 1991;91:165–195. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Petruska JP, Sowers LC, Goodman MF. Comparison of Nucleotide Interactions in Water, Proteins and Vacuum: Model for DNA polymerase Fidelity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1986;83:1559–1562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.6.1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zheng H, Cai Y, Ding S, Tang Y, Kropachev K, Zhou Y, Wang L, Wang S, Geacintov NE, Zhang Y, Broyde S. Base flipping free energy profiles for damaged and undamaged DNA. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2010;23:1868–1870. doi: 10.1021/tx1003613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet. 2001;357:539–545. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schmidt A, Weber OF. In memoriam of Rudolf Virchow: A historical retrospective including aspects of inflammation, infection and neoplasia. Contrib. Microbiol. 2006;13:1–15. doi: 10.1159/000092961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.