Abstract

Significance: Postnatal wounds heal with characteristic scar formation. In contrast, the mid-gestational fetus is capable of regenerative healing, which results in wound repair that is indistinguishable from uninjured skin. However, the underlying mechanisms of fetal regenerative phenotype are unknown.

Recent Advances: The potent anti-inflammatory cytokine, interleukin-10 (IL-10), plays an essential role in the ability of the fetus to heal regeneratively and has been shown to recapitulate scarless healing in postnatal tissue. IL-10's ability to facilitate regenerative healing is likely a result of pleiotropic effects, through regulation of the inflammatory response, as well as novel roles as a regulator of the extracellular matrix, fibroblast cellular function, and endothelial progenitor cells. Overexpression of IL-10 using a variety of methods has been demonstrated to recapitulate the fetal regenerative phenotype in post-natal tissue, in conjunction with promising results of Phase II clinical trials using recombinant IL-10.

Critical Issues: Successful wound healing is a complex process that requires coordination of multiple growth factors, cell types, and extracellular cellular matrix components. IL-10 has been demonstrated to be critical in the fetus' intrinsic ability to heal without scars, and, further, can induce scarless healing in postnatal tissue. The mechanisms through which IL-10 facilitates this regeneration are likely the result of IL-10's pleiotropic effects. Efforts to develop IL-10 as an anti-scarring agent have demonstrated promising results.

Future Directions: Further studies on the delivery, including dose, route, and timing, are required in order to successfully translate these promising findings from in vitro studies and animal models into clinical practice. IL-10 holds significant potential as an anti-scarring therapeutic.

Sundeep G. Keswani, MD

Scope and Significance

Wound healing is a complex process that requires coordinated production and influx of growth factors, extracellular matrix components, and various cell types. In contrast to postnatal tissue, fetal skin has an intrinsic ability to heal without a scar, with regeneration of the dermal and epidermal layers, including dermal appendages.1 Fetal cutaneous wound repair is known to have an attenuated inflammatory response. The anti-inflammatory cytokine, interleukin-10 (IL-10), has been demonstrated to be essential to fetal regenerative wound repair. Further, overexpression of IL-10 recapitulates the fetal-like regenerative phenotype in postnatal tissue through pleiotropic effects: attenuation of the inflammatory response,2,3 regulation of the extracellular matrix,4 optimization of fibroblast function and differentiation,5 and increase in endothelial progenitor cell (EPC).6 This review summarizes the role of IL-10 in fetal wound healing and its ability to recapitulate this type of repair in post-natal skin.

Translational Relevance

Several groups have reported IL-10 results in fetal-like regenerative healing in postnatal tissue in a dose-dependent manner. The implications of this finding for cutaneous wound healing are significant. However, much work still needs to be done in order to translate these findings from bench to bedside. IL-10 holds promise as an anti-scarring therapeutic agent with potential application in multiple modalities. These include intradermal injection, topical applications, and incorporation into biological dressings.

Clinical Relevance

Each year, more than 100 million patients acquire scars, some of which cause considerable morbidity.7 Scarless healing in postnatal skin will have significant implications for surgeons, dermatologists, and patients. Unfortunately, while there are many products in the market, none have been proved effective. In contrast to postnatal wound healing, mid-gestation fetal skin is known to heal wounds without scar formation.8 It is well established that IL-10 has an essential role in the fetus' ability to heal regeneratively. Further investigations are underway to develop novel strategies in order to fully develop IL-10 as an anti-scarring therapeutic agent.

Discussion

Comparison of the fetal regenerative phenotype to postnatal scar formation

Wound healing is a complex process that is initiated by the body immediately after injury. Successful wound closure occurs in well-orchestrated overlapping phases of hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling.9 Hemostasis occurs within minutes to hours of injury with the formation of a provisional matrix and initiation of the inflammatory phase.10 The inflammatory phase in adult wound healing is exuberant and characterized by a substantial influx of neutrophilic granulocytes and macrophages into the wound bed after injury.11 The proliferative phase overlaps with inflammation, with formation of granulation tissue followed by immigration of fibroblasts into the wound bed and re-epithelialization by keratinocytes. Once re-epithelialized, the wound continues to remodel for months with eventual formation of a characteristic scar. Histologically, the scar comprises thick, parallel collagen bundles with the notable absence of dermal appendages, such as hair follicles and sweat glands.

In contrast, mid-gestation fetal skin can heal with restoration of normal skin architecture without scars and with minimal inflammation.8 This regenerative ability is gestational age dependent and corresponds to the second trimester in humans. As the fetus continues to develop, regenerative healing progresses to a transitional phase, which is defined by cutaneous wounds that heal without a scar, but with the absence of dermal appendages.12 Regenerative healing has been shown to occur in multiple mammalian models, including rats, mice, sheep, and monkeys.1 Multiple studies suggest that the ability to regenerate is an intrinsic property of fetal skin and not a result of the sterile in utero environment. Wounding experiments conducted in adult sheep skin transplanted to a fetal sheep and returned to the in utero environment resulted in scar formation.13 Conversely, wounds in human fetal skin transplanted to adult-immunosuppressed (severe combined immunodeficiency) mice retain the ability to heal scarlessly.14 These data support the fact that the in utero environment and amniotic fluid exposure are neither necessary nor sufficient to permit scarless fetal wound healing and imply that regenerative healing is an intrinsic property to fetal skin.

Cytokine hypothesis

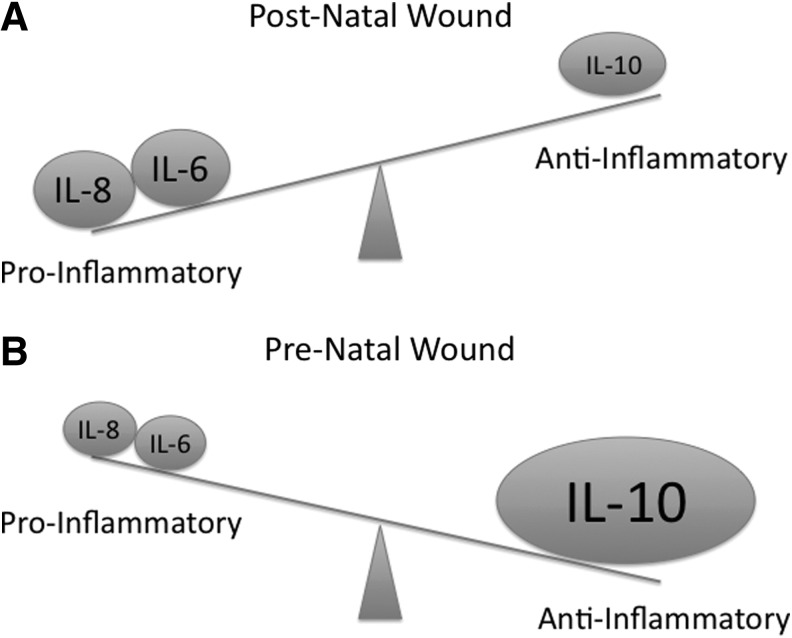

The anti-inflammatory nature of the fetal wound is striking with diminished cellular infiltrate compared with postnatal wounds.15,16 When fetal neutrophils and macrophages were isolated and stimulated in vitro, they were found to respond appropriately to inflammatory stimuli. These data suggest that the attenuated fetal inflammatory response is not a result of immaturity or deficiency inherent to the immune cells, but rather a paucity or innate suppression of chemo-attractant signals in the fetal wound.17 Taken together, these findings have led to the “cytokine hypothesis” which posits that fetal tissue is permissive of regenerative healing due to relatively elevated levels of anti-inflammatory cytokine expression compared with pro-inflammatory cytokines, leading to an anti-inflammatory wound milieu (Fig. 1). Supporting this hypothesis, fetal wounds are noted to have decreased levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-6 and IL-8 compared with adults.18,19 In this murine model, both fetal skin and adult skin respond to injury with an initial increase in pro-inflammatory cytokine production. However, at 12 h post injury, transcription of these pro-inflammatory mediators is undetectable in the fetus. In contrast, adult transcription persists for at least 72 h.18,19 Further evidence is provided by the formation of scar with addition of IL-6 in the fetus at a gestational age that should heal scarlessly.18 Further investigation has demonstrated that fetal skin has decreased levels of other pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-2, IL-12, interferon-gamma, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha.18,19 along with elevated levels of the potent anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10, a potent anti-inflammatory mediator.2

Figure 1.

The “cytokine hypothesis” posits that in the postnatal wound environment, the cytokine milieu results in a pro-inflammatory profile (A); whereas in the pre-natal wound environment, there is a relative decrease in pro-inflammatory cytokines and an increase in anti-inflammatory cytokines, resulting in an overall anti-inflammatory profile (B).

Interleukin-10

IL-10 is a 35-kDa homodimeric cytokine that is produced by a variety of cell types, including T cells, monocytes, and macrophages. In the skin, keratinocytes have been shown to be capable of producing IL-10 after injury.20 IL-10 was originally described as a cytokine synthesis inhibitory factor, for its ability to profoundly activate macrophage/monocyte functions and decrease pro-inflammatory cytokine production.21,22 In addition to its potent anti-inflammatory effects, IL-10 has been shown to regulate fibrogenic cytokines, such as transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) as a part of its role in the regulation of tissue remodeling.23

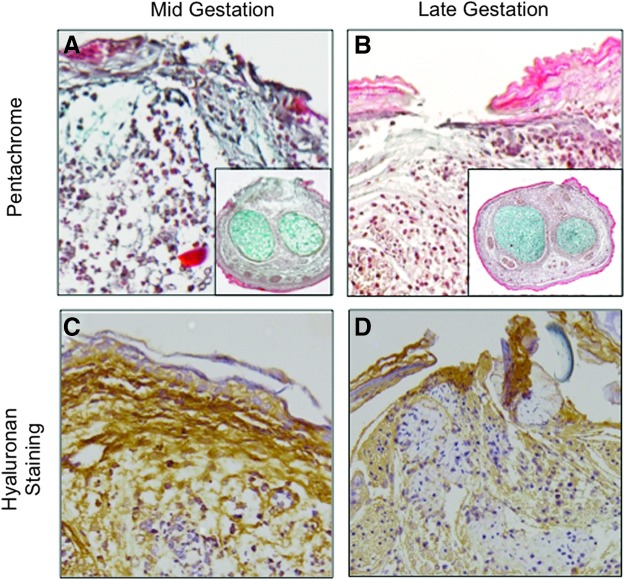

IL-10's signaling pathway has been primarily elucidated in monocytes. IL-10 dimerizes to bind to a tetramer receptor complex that comprises two molecules of IL-10R1 and two molecules of IL-10R2, which permits phosphorylation and dimerization of STAT3. Phosphorylated-STAT3 translocates to the nucleus to activate the downstream target genes (Fig. 2). Of note, IL-6 has also been shown to signal through STAT3. IL-6 is a known pro-inflammatory cytokine that exerts multiple effects in direct opposition to the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, such as increasing inflammatory cell infiltration.24 The opposing downstream actions via a shared transcription factor may be the result of regulation via the SOCS protein family. The SOCS proteins comprise eight proteins and regulate the cellular response to cytokines through multiple actions, including competitive inhibition of STAT recruitment to receptors, targeted polyubiquitination, and proteosomal degradation.24,25 The exact role of the SOCS protein family in regulating the actions of anti-inflammatory IL-10 and pro-inflammatory IL-6 in the regenerative phenotype remain unknown. SOCS3 has been shown to serve as a negative feedback regulator of both anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory cytokines, depending on cell type and local environment.25,26 Additional studies that investigate the role of the SOCS protein family in wound healing are needed to better understand the complicated signaling cascade initiated by tissue injury.

Figure 2.

IL-10 signals primarily through a tetramer complex of IL-10R1 and IL-10R2, resulting in the activation of the JAK/STAT3. This leads to the phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of STAT3, where downstream target genes, such as hyaluronan synthase, are activated. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/wound

Role of interleukin-10

Fetal development

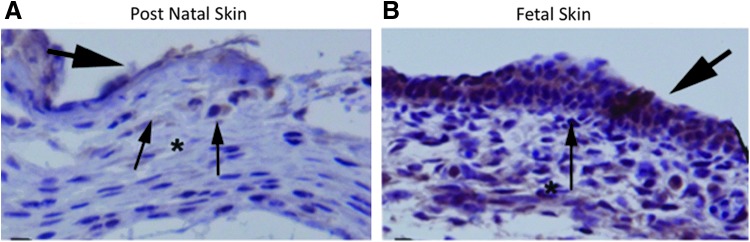

It has been suggested that IL-10 plays an important role in fetal development as a potent anti-inflammatory cytokine, preventing the maternal immune system from mounting a response to the fetus and its “foreign” antigens. Supporting this hypothesis, immunohistochemistry of intact murine skin demonstrated elevated levels of IL-10 in both dermal and epidermal layers of fetal skin, as well as the amniotic fluid through mid-gestation (Fig. 3B). As gestation progresses, the level of IL-10 decreases with minimal expression noted in neonatal skin (Fig. 3A). IL-10 has also been shown to normalize blood pressure and endothelial function in a pregnancy-induced hypertensive rodent model and presents a potential therapeutic target for women with pre-eclampsia.27

Figure 3.

Postnatal murine skin (A) has relatively lower levels of IL-10 (brown) compared with prenatal skin (B) throughout both epidermal and dermal layers (immunohistochemistry, 20×). To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/wound

Regulator of the extracellular matrix

Along with the markedly attenuated inflammatory response, fetal regenerative wound healing has been characterized by a unique extracellular matrix. Collagen constitutes a substantial component of skin. In fetal regenerative healing, collagen is deposited in the wound in a fine reticular pattern, resulting in an extracellular matrix that is indistinguishable from surrounding tissue. This is in stark contrast to postnatal scars, which deposit collagen in thick bundles that are organized in parallel arrays along lines of tension. In addition, although type I collagen is the predominant form in both fetal and postnatal wounds, the ratio of type III collagen to type I collagen is much higher in fetal wounds. After injury and remodeling, type III collagen accounts for 10–20% of total collagen in adult wounds, whereas it accounts for more than 30–60% in fetal wounds.28,29 Type III collagen bundles are smaller than type I and are found in more elastic tissue types. This difference in composition may permit for a more reticular deposition and fetal-like phenotype. Pathologic scarring such as keloids are characterized by excess deposition of both type I and type III collagen. IL-10 has recently been demonstrated to have a protective effect against the excessive deposition of collagen associated with scar formation when stimulated with pro-fibrotic agents.30

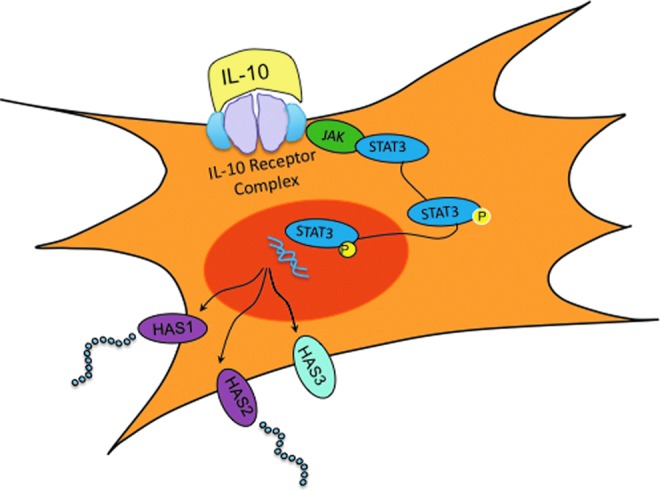

Fetal regenerative healing is also characterized by high levels of glycosaminoglycans, such as hyaluronan.4 Hyaluronan is a hydrophilic glycosaminoglycan that enables the extracellular matrix to expand and may permit for the rapid migration of cells, such as fibroblasts.5,31 Mid-gestation fetal wounds that are capable of scarless wound healing have increased levels of hyaluronan and ground substance (Fig. 4A, C) compared with scar-forming late-gestation fetal wounds (Fig. 4B, D) when hyaluronan content is evaluated with immunohistochemistry in an ex vivo organ culture model. Following these regenerative fetal wounds through the healing process, they have elevated and persistent levels of hyaluronan in contrast to the transient increase in hyaluronan observed post-natal tissue, which quickly returns to baseline.32 We have demonstrated the ability for IL-10 to maintain elevated fetal hyaluronan, as well as to induce postnatal hyaluronan production.33 Hyaluronan is suggested to be an important component in early phases of regenerative wound healing with biological properties dependent on its molecular size.34 High-molecular-weight hyaluronan has been shown to promote a fetal-like environment with elevated type III collagen and TGF-β3 expression, while low-molecular-weight hyaluronan favors scar formation with stimulation of type I collagen.28

Figure 4.

Mid-gestation murine fetal incisional wounds have elevated ground substance (A, blue) and hyaluronan (C, brown) compared with late-gestation fetal wounds (B, D) in an ex vivo organ culture model (pentachrome, hyaluronan staining). To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/wound

Fibroblast function

Fibroblasts are key effector cells in wound healing. In postnatal wounds, fibroblasts infiltrate the wound bed and form the provisional matrix composed of ground substance, where hyaluronan is an important component. Within the granulation tissue, the fibroblasts secrete numerous growth factors, which stimulate and permit keratinocyte growth and migration. The regenerative effects of IL-10 on the epithelium may be mediated through an interaction between fibroblasts and keratinocytes. Although keratinocytes can be stimulated to produce IL-10, they lack specific binding of IL-10 with and do not express IL-10 receptors.35 In contrast, fetal fibroblasts respond readily to IL-10 and have been found to have superior migration and invasion through provisional matrices compared with adult fibroblasts.5 It remains to be determined whether this increased migration is due to increased chemotactic signals within the matrix or increased production of proteolytic enzymes that allow this rapid movement. However, we have recently found evidence that IL-10-mediated hyaluronan is necessary for this enhanced function.5 Interestingly, supplementation of IL-10 to postnatal fibroblasts effectively increases both migration and invasion, but when hyaluronan synthesis is inhibited, this enhanced fibroblast movement is decreased back to baseline.5 In addition, fetal fibroblasts have a two- to fourfold greater expression of hyaluronan receptors.36 These data suggest that IL-10-mediated effects on the extracellular matrix, in particular, through increased hyaluronan production, permit enhanced fibroblast function and may, in part, account for the fetal regenerative phenotype.5

Myofibroblast differentiation

During the early phases of wound healing, a subset of fibroblasts differentiate to myofibroblasts with stress fibers containing alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA).37 This differentiated population facilitates extracellular matrix deposition and generates the mechanical forces seen in wound contracture. After successful re-epithelialization, these fibroblasts undergo apoptosis or de-differentiate. Persistence of this population has been identified in pathologic tissues that are characterized by excess fibrosis, such as hypertrophic scarring and fibromatosis disease.37,38 Mid-gestational incisional wounds that heal regeneratively have a notable absence of myofibroblasts.39 IL-10 has been demonstrated to protect against the formation of α-SMA when stimulated by pro-fibrotic agents and may, in part, account for the regenerative healing seen in the fetus.30

Endothelial progenitor cells

IL-10 has also been shown to play a role in modulating EPC survival and function in a different model of tissue injury, the injured myocardium. EPCs are bone marrow-derived cells that contribute to postnatal angiogenesis through production of growth factors and, to a lesser extent, differentiation into endothelial cells. Myocardial infarction has many similarities to cutaneous wound healing, including an induced inflammatory response and the requirement of neo-vascularization to repair injured tissue.40 In IL-10−/− mice, there is a deficiency in EPC recruitment.6 Further, treatment with IL-10 results in increased EPC survival and angiogenesis,6 as well as an attenuated inflammatory response, decreased fibrosis, and preservation of cardiac function.40 Recent results from our murine wound-healing studies have suggested a similar effect of IL-10 on EPCs in cutaneous wound healing. Overexpression of IL-10 results in an increase in the number of EPCs in the wound, as well as in circulation, after injury in postnatal tissue.6

IL-10 is essential to regenerative fetal wound healing

To further examine the role of IL-10 in regenerative wound healing, incisional wounds have been created in mid-gestation fetal skin from transgenic IL-10 knockout mice. Absence of IL-10 results in an exaggerated inflammatory response with increased monocyte infiltration of the wound bed. As a potent anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10 deactivates monocytes and macrophages, and decreases production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Fetal skin at a gestational age that usually heals regeneratively results in scar formation with loss of IL-10 with increased and abnormal collagen deposition.41 These observations suggest that the attenuated inflammatory response observed in regenerative fetal wound healing may be regulated by IL-10, and also suggest that IL-10 is essential for the scarless fetal phenotype.

IL-10 is essential for mechanical integrity in postnatal wound healing

To investigate the role of IL-10 in postnatal healing, a loss of function experiment was conducted by creating incisional wounds in transgenic IL-10 knockout (IL-10−/−) skin. Murine wounds deficient in IL-10 have enhanced wound contraction and increased inflammatory response, with an increased number of macrophages infiltrating the wound bed.41,42 The wound was found to have higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and IL-8, in the absence of IL-10.43 Excisional wounds made in this transgenic strain demonstrated accelerated re-epithelialization; however, the wounds had compromised mechanical strength.42 The loss of biomechanical strength suggests that the matrix deposition and maturation is not improved but impeded by the loss of IL-10.42 The IL-10−/− transgenic wounds had more deposition of collagen, with altered organization with deposition of thick, densely packed parallel layers compared with control scars. Taken together, these results support the role of IL-10 as an important regulator of the postnatal wound inflammatory response, and also suggest that IL-10 affects the organization and maturation of the extracellular matrix in the wound.

IL-10 overexpression in mice permits regenerative healing in postnatal tissue

Multiple investigators have evaluated the effects of IL-10 overexpression in postnatal wound healing, with the goal of inducing regenerative wound healing by recapitulating the higher levels of IL-10 seen in fetal skin. Using viral vectors to facilitate local and sustained release of IL-10 in the dermis, IL-10 overexpression has been shown to successfully decrease the postnatal inflammatory response to injury.2,3 There were fewer neutrophils, lymphocytes, and macrophages recruited to the wound during the inflammatory phase. IL-10 facilitates a more organized pattern of extracellular matrix deposition with no change in biomechanical strength between IL-10 treated wounds and unwounded skin. This suggests that addition of IL-10 permits wound repair with normal physiologic integrity. At ninety days after wounding, IL-10 overexpression has been shown to reduce scar formation in murine incisional wounds in a dose-dependent manner, with the resultant wound indistinguishable from unwounded skin.2

Interestingly, with the use of an adenoviral vector to facilitate IL-10 overexpression, thereby limiting the expression to seven to ten days, the differences seen in scar formation are noted several weeks to months after injury, long after the vector ceases to produce IL-10.2 This suggests that IL-10 plays an early role in the tissue response to injury and is only necessary for a brief period to initiate a cascade of events, ultimately permitting reduction of scar formation and regenerative healing.

Role of IL-10 in tissue repair beyond cutaneous wound healing

IL-10 has been shown to play an important role in a variety of other models of tissue repair beyond cutaneous wound healing. The importance of IL-10 in re-establishing tissue integrity has been demonstrated in a tendon injury model. This model demonstrates that healing of postnatal tendons benefits from lenti-viral mediated overexpression of IL-10, which results in superior biomechanical properties compared with control tendon injury.44 IL-10 has also been shown to be beneficial at low concentrations after nerve repair in a murine sciatic injury model. In this model, low doses of recombinant IL-10 were injected immediately preceding nerve transection. The IL-10 pre-treated nerve repairs demonstrated increased myelinated fiber regeneration across repair sites compared with controls at six weeks after injury. Interestingly, high doses of IL-10 were found to be ineffective.45 In addition, IL-10 has been found to play an important role in muscle growth and regeneration. In a murine model of muscle adaption, utilizing hindlimb unloading and reloading, IL-10 knockout mice demonstrated delayed muscle regeneration and growth compared with control mice.46 Studies in murine cardiac tissue have demonstrated that IL-10 plays an important role after injury in an induced cardiac hypertrophy model. IL-10 knockout mice were found to have increased left ventricular function and hypertrophic remodeling compared with controls. Supplementation with IL-10 was found to be cardio-protective and improved cardiac function with prevention of pathologic remodeling.40 In addition, IL-10 has been demonstrated to be beneficial in a murine pulmonary fibrosis model, where plasmid-mediated IL-10 gene delivery suppresses the development of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis with inhibition of alveolar macrophages and fibrosis.47

Interestingly, IL-10 has been shown to play the opposite role in hepatic tissue and negatively regulates liver regeneration and hepatocyte proliferation. In a murine model evaluating liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy, the pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, are suggested to play a critical role in the initiation and progression of liver regeneration. IL-10 knockout mice demonstrate enhanced hepatocyte regeneration and proliferation compared with control mice.48

IL-10 as a therapeutic agent

Promising results have been shown in multiple animal models, demonstrating successful induction of regenerative healing through IL-10 overexpression, facilitated through viral vector constructs.2,3 Although these studies demonstrate the proof of concept, IL-10 creates a wound environment permissive of regeneration, there are legitimate concerns of clinical translation using a viral construct with concerns for oncogenicity. However, these studies suggest that wounds require only a brief period of exposure to elevated levels of IL-10 to reduce in scar formation. This brief exposure has led to the development of clinical trials to further investigate recombinant IL-10 as a potential therapeutic agent, thereby eliminating delivery of viral components.49 Although there have been promising results with decreased scar formation noted at twelve months in a randomized, double-blinded, placebo controlled trial, further studies are needed before a clinically relevant product will be available.1,49

Take-Home Messages.

• The fetus is capable of regenerative wound healing and is characterized by an anti-inflammatory cytokine milieu with decreased levels of IL-6 and IL-8 and elevated levels of IL-10.

• IL-10 is essential to the fetal regenerative phenotype and is capable of recapitulating fetal-like scarless wound healing in postnatal tissue.

• IL-10 is important in re-establishing tissue integrity after injury in multiple models, including skin, tendon, and myocardium.

• IL-10 has pleiotropic effects, including regulation of the extracellular matrix, modulation of fibroblast function, and differentiation and increased presence of EPCs.

• Clinical trials of IL-10 have demonstrated promising results with decreased scar formation. The therapeutic applications of IL-10 as an anti-scarring agent may be beneficial to any pathology that is characterized by excess fibrosis, including renal fibrosis, intra-abdominal adhesions, hypertrophic scarring, or pulmonary fibrosis.

Implications of IL-10 in wound healing

Each year in the developed world, 100 million patients acquire scars with an estimated 11 million keloid scars and 4 million burn scars.7 These scars may lead to considerable functional and psychosocial morbidity. Although we have known that the fetus is capable of healing cutaneous wounds without scars, the underlying mechanisms are incompletely understood. We now have the molecular tools to further elucidate the mechanisms of the fetal regenerative response, suggesting a critical role for the cytokine IL-10. Overexpression of IL-10 is able to recapitulate the fetal scarless phenotype in postnatal tissue through its wide-ranging pleiotropic effects, attenuating the inflammatory response, enhancing fibroblast function, regulating the extracellular matrix, and modulating stem cell function. The potential therapeutic benefits of IL-10 extend far beyond cosmetic benefit, but may apply to a broad range of diseases that are characterized by excessive fibroplasia, including hypertrophic scarring, intra-abdominal adhesions, and pulmonary and renal fibrosis.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- IL-10

interleukin-10

- IL-10R1

interleukin-10 receptor 1

- IL-10R2

interleukin-10 receptor 2

- EPC

endothelial progenitor cell

- α-SMA

alpha-smooth muscle actin

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor-β

Acknowledgments and Funding Sources

This work was supported by grants from The National Institutes of General Medical Sciences K08 GM098831-02 and the Wound Healing Society Foundation 3M Award to S.G. Keswani.

Author Disclosure and Ghostwriting

There are no competing financial interests for any author. The content of this article is expressly written by the authors listed. No ghostwriters were used to write this article.

About the Authors

Alice King is a University of Cincinnati General Surgery Resident who has completed a two-year postdoctoral research fellowship in the laboratory for regenerative wound healing at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC). Swathi Balaji received her PhD in Biomedical Engineering from University of Cincinnati. She is a postdoctoral research fellow in the Laboratory for Regenerative Wound Healing at CCHMC specializing in mechanisms underlying fetal regenerative wound healing. Louis D. Le is currently working as a trauma fellow at CCHMC. He is a board certified General Surgeon, who has completed general surgery residency from Louisiana State University with a two-year postdoctoral research fellowship in the Laboratory for Regenerative Wound Healing. Timothy M. Crombleholme is the Surgeon-in-Chief at Children's Hospital, Colorado and he has had extensive NIH funding to study the role of EPCs in wound healing and neovascularization. Sundeep G. Keswani is a pediatric and fetal surgeon at CCHMC. He is the Principle Investigator of the Laboratory for Regenerative Wound Healing at CCHMC focused on elucidating the mechanisms underlying the fetal regenerative phenomenon, and is also the director of Pediatric Wound Care Center at CCHMC.

References

- 1.Leung A, Crombleholme TM, and Keswani SG: Fetal wound healing: implications for minimal scar formation. Curr Opin Pediatr 2012; 24:371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gordon A, Kozin ED, Keswani SG, et al. : Permissive environment in postnatal wounds induced by adenoviral-mediated overexpression of the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-10 prevents scar formation. Wound Repair Regen 2008; 16:70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peranteau WH, Zhang L, Muvarak N, et al. : IL-10 overexpression decreases inflammatory mediators and promotes regenerative healing in an adult model of scar formation. J Invest Dermatol 2008; 128:1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.King A, Balaji S, Marsh E, et al. : Interleukin-10 regulates the fetal hyaluronan-rich extracellular matrix via a STAT3-dependent mechanism. J Surg Res, 2013; 184:671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leung A, Balaji S, Le L, et al. : Interleukin-10 and hyaluronan are essential to the fetal fibroblast functional phenotype. J Surg Res 2013; 179:257 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krishnamurthy P, Thal M, Verma S, et al. : Interleukin-10 deficiency impairs bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cell survival and function in ischemic myocardium. Circ Res 2011; 109:1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bayat A, McGrouther DA, and Ferguson MW: Skin scarring. BMJ 2003; 326:88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rowlatt U: Intrauterine wound healing in a 20 week human fetus. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol 1979; 381:353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reinke JM, and Sorg H: Wound repair and regeneration. Eur Surg Res; Europaische chirurgische Forschung Recherches chirurgicales europeennes 2012; 49:35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Satterly S, Nelson D, Zwintscher N, et al. : Hemostasis in a noncompressible hemorrhage model: an end-user evaluation of hemostatic agents in a proximal arterial injury. J Surg Educ 2013; 70:206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin P: Wound healing—aiming for perfect skin regeneration. Science 1997; 276:75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Longaker MT, Whitby DJ, Adzick NS, et al. : Studies in fetal wound healing, VI. Second and early third trimester fetal wounds demonstrate rapid collagen deposition without scar formation. J Pediatr Surg 1990; 25:63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Longaker MT, Whitby DJ, Ferguson MW, et al. : Adult skin wounds in the fetal environment heal with scar formation. Ann Surg 1994; 219:65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lorenz HP, Longaker MT, Perkocha LA, et al. : Scarless wound repair: a human fetal skin model. Development 1992; 114:253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adzick NS, Harrison MR, Glick PL, et al. : Comparison of fetal, newborn, and adult wound healing by histologic, enzyme-histochemical, and hydroxyproline determinations. J Pediatr Surg 1985; 20:315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mast BA, Haynes JH, Krummel TM, et al. : In vivo degradation of fetal wound hyaluronic acid results in increased fibroplasia, collagen deposition, and neovascularization. Plast Reconstr Surg 1992; 89:503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mast BA, Albanese CT, and Kapadia S: Tissue repair in the fetal intestinal tract occurs with adhesions, fibrosis, and neovascularization. Ann Plast Surg 1998; 41:140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liechty KW, Adzick NS, and Crombleholme TM: Diminished interleukin 6 (IL-6) production during scarless human fetal wound repair. Cytokine 2000; 12:671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liechty KW, Crombleholme TM, Cass DL, et al. : Diminished interleukin-8 (IL-8) production in the fetal wound healing response. J Surg Res 1998; 77:80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.An L, Dong GQ, Gao Q, et al. : Effects of UVA on TNF-alpha, IL-1beta, and IL-10 expression levels in human keratinocytes and intervention studies with an antioxidant and a JNK inhibitor. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed 2010; 26:28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fortunato SJ, Menon R, and Lombardi SJ: The effect of transforming growth factor and interleukin-10 on interleukin-8 release by human amniochorion may regulate histologic chorioamnionitis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1998; 179:794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moore KW, de Waal Malefyt R, Coffman RL, et al. : Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu Rev Immunol 2001; 19:683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamamoto T, Eckes B, and Krieg T: Effect of interleukin-10 on the gene expression of type I collagen, fibronectin, and decorin in human skin fibroblasts: differential regulation by transforming growth factor-beta and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2001; 281:200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang C, Li Y, Wu Y, et al. : Interleukin-6/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) pathway is essential for macrophage infiltration and myoblast proliferation during muscle regeneration. J Biol Chem 2013; 288:1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Croker BA, Krebs DL, Zhang JG, et al. : SOCS3 negatively regulates IL-6 signaling in vivo. Nat Immunol 2003; 4:540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hokenson MA, Wang Y, Hawwa RL, et al. : Reduced IL-10 production in fetal type II epithelial cells exposed to mechanical stretch is mediated via activation of IL-6-SOCS3 signaling pathway. PLoS One 2013; 8:e59598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tinsley JH, South S, Chiasson VL, et al. : Interleukin-10 reduces inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and blood pressure in hypertensive pregnant rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2010; 298:R713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.David-Raoudi M, Tranchepain F, Deschrevel B, et al. : Differential effects of hyaluronan and its fragments on fibroblasts: relation to wound healing. Wound Repair Regen 2008; 16:274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Merkel JR, DiPaolo BR, Hallock GG, et al. : Type I and type III collagen content of healing wounds in fetal and adult rats. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1988; 187:493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi JH, Guan H, Shi S, et al. : Protection against TGF-beta1-induced fibrosis effects of IL-10 on dermal fibroblasts and its potential therapeutics for the reduction of skin scarring. Arch Dermatol Res, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ellis I, Banyard J, and Schor SL: Differential response of fetal and adult fibroblasts to cytokines: cell migration and hyaluronan synthesis. Development 1997; 124:1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Estes JM, Adzick NS, Harrison MR, et al. : Hyaluronate metabolism undergoes an ontogenic transition during fetal development: implications for scar-free wound healing. J Pediatr Surg 1993; 28:1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leung A, Balaji S, Le LD, et al. : An in vitro and ex vivo study of fetal wound healing: a novel role for Il-10 as a regulator of the extracellular matrix. Wound Repair Regen 2012; 20:A29 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang C, Cao M, Liu H, et al. : The high and low molecular weight forms of hyaluronan have distinct effects on CD44 clustering. J Biol Chem 2012; 287:43094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seifert M, Gruenberg BH, Sabat R, et al. : Keratinocyte unresponsiveness towards interleukin-10: lack of specific binding due to deficient IL-10 receptor 1 expression. Exp Dermatol 2003; 12:137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alaish SM, Yager D, Diegelmann RF, et al. : Biology of fetal wound healing: hyaluronate receptor expression in fetal fibroblasts. J Pediatr Surg 1994; 29:1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Phan SH: Biology of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2008; 5:334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Desmouliere A, Chaponnier C, and Gabbiani G: Tissue repair, contraction, and the myofibroblast. Wound Repair Regen 2005; 13:7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cass DL, Sylvester KG, Yang EY, et al. : Myofibroblast persistence in fetal sheep wounds is associated with scar formation. J Pediatr Surg 1997; 32:1017; discussion 1021–1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verma SK, Krishnamurthy P, Barefield D, et al. : Interleukin-10 treatment attenuates pressure overload-induced hypertrophic remodeling and improves heart function via signal transducers and activators of transcription 3-dependent inhibition of nuclear factor-kappaB. Circulation 2012; 126:418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liechty KW, Kim HB, Adzick NS, et al. : Fetal wound repair results in scar formation in interleukin-10-deficient mice in a syngeneic murine model of scarless fetal wound repair. J Pediatr Surg 2000; 35:866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eming SA, Werner S, Bugnon P, et al. : Accelerated wound closure in mice deficient for interleukin-10. Am J Pathol 2007; 170:188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sato Y, Ohshima T, and Kondo T: Regulatory role of endogenous interleukin-10 in cutaneous inflammatory response of murine wound healing. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1999; 265:194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ricchetti ET, Reddy SC, Ansorge HL, et al. : Effect of interleukin-10 overexpression on the properties of healing tendon in a murine patellar tendon model. J Hand Surg [Am] 2008; 33:1843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Atkins S, Loescher AR, Boissonade FM, et al. : Interleukin-10 reduces scarring and enhances regeneration at a site of sciatic nerve repair. J Peripher Nerv Syst 2007; 12:269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Deng B, Wehling-Henricks M, Villalta SA, et al. : IL-10 triggers changes in macrophage phenotype that promote muscle growth and regeneration. J Immunol 2012; 189:3669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakagome K, Dohi M, Okunishi K, et al. : In vivo IL-10 gene delivery attenuates bleomycin induced pulmonary fibrosis by inhibiting the production and activation of TGF-beta in the lung. Thorax 2006; 61:886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yin S, Wang H, Park O, et al. : Enhanced liver regeneration in IL-10-deficient mice after partial hepatectomy via stimulating inflammatory response and activating hepatocyte STAT3. Am J Pathol 2011; 178:1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kieran I, Knock A, Bush J, et al. : Interleukin-10 reduces scar formation in both animal and human cutaneous wounds: results of two preclinical and phase II randomized control studies. Wound Repair Regen 2013; 21:428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]