Abstract

Although more than 109 years have passed since the existence of the last universal common ancestor, proteins have yet to reach the limits of divergence. As a result, metabolic complexity is ever expanding. Identifying and understanding the mechanisms that drive and limit the divergence of protein sequence space impact not only evolutionary biologists investigating molecular evolution but also synthetic biologists seeking to design useful catalysts and engineer novel metabolic pathways. Investigations over the past 50 years indicate that the recruitment of enzymes for new functions is a key event in the acquisition of new metabolic capacity. In this review, we outline the genetic mechanisms that enable recruitment and summarize the present state of knowledge regarding the functional characteristics of extant catalysts that facilitate recruitment. We also highlight recent examples of enzyme recruitment, both from the historical record provided by phylogenetics and from enzyme evolution experiments. We conclude with a look to the future, which promises fruitful consequences from the convergence of molecular evolutionary theory, laboratory-directed evolution, and synthetic biology.

Enzyme recruitment is the process whereby an extant catalyst is enlisted to perform a new function that provides a selective advantage to a host organism. The new function can be comparable to, or distinct from, the enzyme’s ancestral purpose. Recruitment requires a random genetic change that affords realization of the new function and subsequent fixation of the gene encoding the new catalyst within a given population. In many instances, enzyme recruitment represents the initial molecular genetic event upon which the acquisition of new metabolic potential relies.1

Although enzyme recruitment was long proposed to be a driving force in metabolic evolution,1,2 conclusive evidence of recruitment required advances in comparative phylogenetics and high-throughput structural biology. The enormous number of protein primary structure data resulting from genomic sequencing efforts of the past 25 years provide compelling evidence that enzyme recruitment is pervasive in extant metabolic pathways. Structural and functional studies have revealed surprising evolutionary relationships between enzymes that catalyze seemingly disparate transformations.3,4 This information is leading to a more detailed appreciation of the interrelatedness within, and between, primary and secondary metabolism. Moreover, recent experimental work suggests that recruitment likely contributed to the earliest stages of evolution, including the templated synthesis of polypeptides.5−7

Investigating the molecular mechanisms of enzyme recruitment is not simply an exercise in understanding the past. Recruitment also plays a central role in important contemporary biological processes. It facilitates the appearance of drug resistance in microorganisms,8 as well as the emergence of bioremediation pathways for anthropogenic toxins.9 Our understanding of enzyme recruitment is now sufficiently advanced that protein engineers and synthetic biologists are beginning to utilize this knowledge for the discovery of new catalysts and the design of novel metabolic pathways. For these reasons, a review of enzyme recruitment is particularly timely.

Mechanisms That Facilitate Enzyme Recruitment

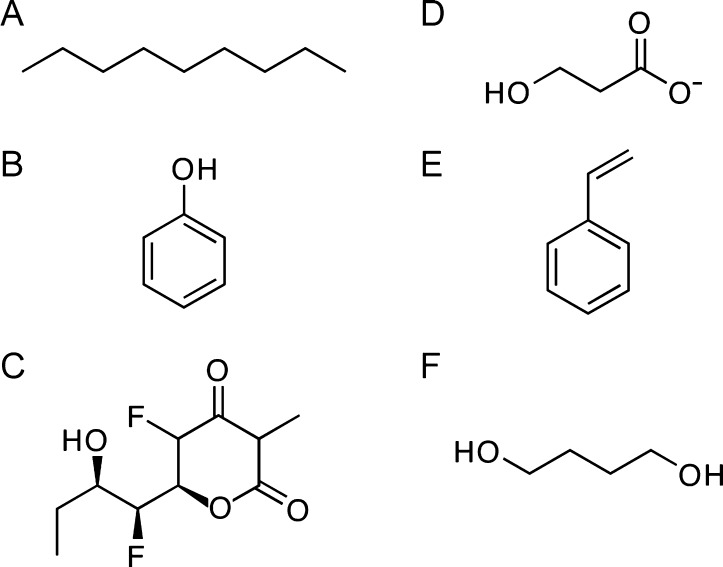

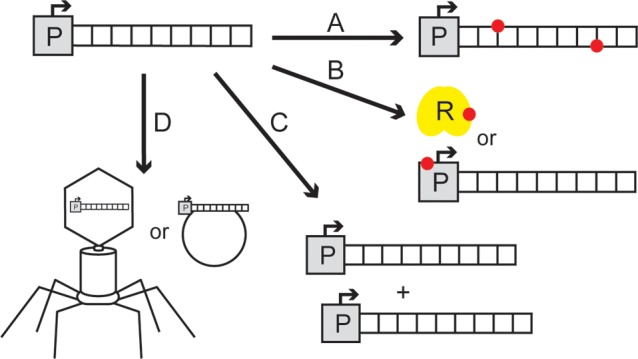

All mechanisms that drive enzyme recruitment involve genetic change. The simplest of these is the accumulation of point mutations. A point mutation can facilitate enzyme recruitment by enhancing a latent activity or by installing a new function onto a preexisting catalyst (Figure 1A). Point mutations appear at an average rate of 0.0033 nucleotide change per genome per DNA replication in microorganisms.10 However, a vast majority of these mutations do not become fixed, because they are either neutral or deleterious.11,12 Most instances of recruitment are not driven by a gain-of-function point mutation but instead involve a beneficial mutation that causes a loss of regulatory control leading to overproduction of an enzyme possessing hidden activity.1,13 For example, the transcriptional level of a coding region can be elevated by mutations that inactivate a repressor protein or by promoter mutations that disrupt the binding site for a repressor (Figure 1B). Similarly, the translational level of an enzyme can be increased by mutations that alter codon usage efficiency, mRNA stability, or ribosome binding strength. Hence, enzyme recruitment can be facilitated by any mutation that amplifies the cellular concentration of a catalyst to an extent such that a latent function rises to a physiologically relevant level.

Figure 1.

Genetic mechanisms that facilitate enzyme recruitment. (A) Gain-of-function point mutations (red) that endow new activity to an extant gene. (B) Beneficial point mutations (red) that afford enzyme overproduction by inactivating a repressor protein (R, yellow) or by disrupting the binding site of the repressor in the promoter (P) region. (C) Gene duplication. (D) Horizontal gene transfer by virtue of a phage or an extrachromosomal plasmid.

A more substantial change at the genomic level that can facilitate recruitment is gene duplication (Figure 1C). Gene duplication events occur frequently during the normal course of cell division.14,15 Under normal environmental conditions, the estimated frequency of gene duplication in Salmonella typhimurium is 10–2 to 10–4 per genome per DNA replication.16,17 This level increases under extreme environmental conditions15,18 but can rapidly return to normal levels within a few generations after the selective pressure disappears.19 It is estimated that at least 10% of all prokaryotic cells contain at least one duplicated gene.20,21 Gene duplication provides another mechanism for the overproduction of a gene product with latent activity.22−26 Duplication also removes constraints associated with the retention of a gene’s ancestral function, as one copy of the gene continues to fulfill its intended metabolic task, while the second copy can be subjected to more intense diversification.27,28

Horizontal gene transfer is another genetic alteration that promotes enzyme recruitment by providing new genetic material to a host organism (Figure 1D). Short DNA sequences, as well as complete coding fragments, can be transferred via conjugation and plasmid exchange or directly acquired from the environment.29−31 Importantly, this exchange of genetic material can occur within or between species.32−34 Genome sizes can increase by 10–80% as a result of gene transfer or gene duplication, providing a wealth of new genetic material for subsequent diversification.17 Duplication and horizontal gene transfer also allow for shuffling of partial coding regions, which can lead to the generation of new multifunctional proteins. Although gene duplications and horizontal transfer events are less genetically stable than point mutations, their natural frequency exceeds the rate of beneficial point mutation by several orders of magnitude.17 For this reason, the duplication and transfer of genes are particularly effective in promoting enzyme recruitment.

Properties of Enzymes That Facilitate Their Recruitment

Genetic variation is constantly occurring within organisms, providing ample opportunities to recruit enzymes for new biological purposes. What makes one recruitment event successful while others are only transient in nature? The answer to this question depends, in part, upon the environmental context in which recruitment takes place. However, specific characteristics of the catalyst appear to contribute to the long-term success of the recruitment process. In general, the more evolvable an enzyme, the more likely that it will become permanently recruited to perform a new task.35

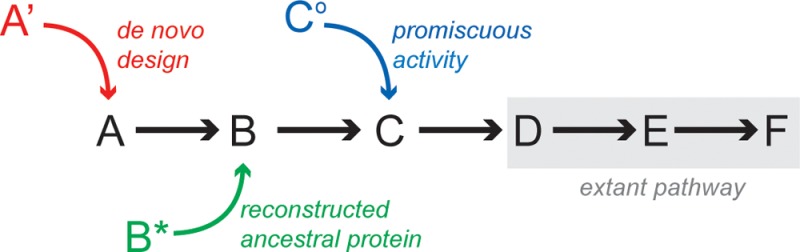

As with other proteins, the evolvability of an enzyme is determined by its stability and its potential for functional innovation.36−38 Stability promotes mutational robustness,39−41 as newly introduced mutations are often destabilizing in nature.36,42 Thus, a highly stable enzyme can tolerate the accumulation of a larger number of destabilizing mutations. Because the acquisition and optimization of new function often require the accumulation of multiple mutations, stability is beneficial for evolvability.43,44 Stability often correlates with reduced conformational flexibility,45−47 however, and biochemists now appreciate that structural plasticity and dynamism can empower the evolution of function by providing access to different conformational states and unique arrangements of active site residues (Figure 2A).48 In nature, the apparent conflict between the benefits of stability (i.e., mutational robustness) and the benefits of flexibility (i.e., functional plasticity) is addressed by specific features of the polypeptide scaffold. For many proteins, an apparent correlation exists between the thermal stability of the folded state and the physiological temperature that provides optimal growth for the host organism.49 This correlation indicates that proteins are, in general, only marginally stable at the specific environmental conditions under which selective pressures operate.50 Marginal stability provides a balance between maintaining a well-folded structure and retaining sufficient flexibility to promote evolvability.49 Protein scaffolds are equipped with discrete structural elements that confer flexibility and stability. For example, the (β/α)8-barrel scaffold appears to be highly evolvable.51,52 It represents a common enzymatic fold that is present in more than 120 enzyme families.38 The (β/α)8-barrel fold is built from a stable core of repeating α-helix−β-strand units, which are linked together by a series of intervening loops. The loops cap the active site, which is located near the C-terminal end of the β-strands. In this scaffold, the core provides mutational robustness while the loops provide flexibility. A similar segregation of protein structural elements is apparent in other polypeptide folds.35

Figure 2.

Properties that facilitate enzyme recruitment. (A) Trade-off between stability, which affords mutational robustness, and flexibility, which affords functional plasticity. (B) Substrate ambiguity (left) allows a single enzyme to transform multiple structurally distinct compounds, and catalytic promiscuity (right) allows a single enzyme to catalyze multiple chemically distinct transformations. (C) Epistasis constrains the evolutionary trajectories of ancestral enzyme sequences (black arrows represent mutations) into functionally discrete pools (blue, orange, and violet). Epistasis prevents the interconversion of contemporary functions without retracing past trajectories (red sign). Figure adapted from ref (61).

The potential for future functional innovation is another contributor to enzyme evolvability.53−55 Enzymes have long been depicted as highly specialized catalysts with finely tuned functionalities.56 However, recent experiments demonstrate that such a picture is oversimplified. We now recognize that contemporary enzymes can be both promiscuous in the reactions they catalyze and ambiguous in their choice of substrates (Figure 2B).57−59 Catalytic promiscuity is defined as the ability of an enzyme to promote distinct chemical transformations that are often related by a common half-reaction or involve a common intermediate.55 Substrate ambiguity is a related but conceptually distinct attribute, which describes an enzyme’s ability to catalyze the same chemical transformation on a series of structurally distinct reactants. Although catalytic promiscuity and substrate ambiguity were most likely more pronounced in ancestral proteins, they continue to facilitate enzyme recruitment by contributing to evolvability.60 Promiscuity and ambiguity provide flexibility to modern metabolism and endow multifunctionality to catalysts. As such, finding new ways to detect and characterize promiscuous or ambiguous catalysts is likely to be advantageous to protein engineers seeking to repurpose extant enzymes.

Studies of molecular evolution have demonstrated that the trajectory of natural protein evolution is highly context-dependent.42,61 In many cases, a particular amino acid substitution that proves to be beneficial in one genetic context can be deleterious in another. Epistasis is the term used to describe such a situation, in which the positive or negative fitness impact of a mutational event is contingent upon the genetic background, and thus the past evolutionary history, of a protein.62,63 In this situation, interactions between mutations can produce nonadditive effects on phenotype and fitness. Multiple-sequence alignment analyses indicate that epistatic constraints are a dominant factor in dictating both the rate and scope of natural protein evolution.64,65 From an evolvability perspective, epistasis appears to be a key limiting factor in the ability to generate new molecular function, as it limits sampling of many distinct evolutionary trajectories (Figure 2C). Epistasis can also constrain the end point of an evolutionary trajectory, as it can lead to a rugged fitness landscape containing many local minima into which evolving species can become trapped.66 In some instances, epistasis stems from the multifaceted nature of a protein’s biophysical properties. This is because the impact of a mutation is not solely limited to its effect upon activity. It can also impact the stability, solubility, and interaction network of a protein. These features act in concert to determine the fitness outcome of specific amino acid substitutions.67 In one experimental evolution study, Hartl and co-workers demonstrated that epistasis resulting from such “biophysical pleiotropy” is so strong that the trajectory of evolution is limited to a very narrow ridge along the adaptive landscape.68 From a total of 120 potential evolutionary trajectories available for the evolution of a highly active β-lactamase from a progenitor catalyst, more than 100 were inaccessible because of epistasis. Identifying methods to overcome epistatic constraints upon the evolutionary process could be useful in future efforts to expand the functionality of biological catalysts.

Evidence of Natural Enzyme Recruitment

Instances of enzyme recruitment have been detected in multiple primary metabolic pathways.69−72 In general, past recruitment events are most easily identified by searching for similar chemical transformations within unrelated branches of metabolism. Subsequent comparative sequence and structural analyses of the associated enzymes reveal potential homology. Several excellent reviews describing specific recruitment events are available.1,73−81 Below we highlight only a few examples for illustrative purposes.

An interesting example of recent enzyme recruitment has been discovered in the pentachlorophenol catabolism pathway of Sphingobium chlorophenolicum.81 Pentachlorophenol is a halogenated aromatic pollutant found in several pesticides and disinfectants.82 Pentachlorophenol hydroxylase (PcpB) is a flavin monooxygenase that catalyzes the first step in pentachlorophenol bioremediation.83 Sequence analysis reveals that PcpB was likely recruited from a pathway involving hydroxylation of natural products.81 The dehalogenation reaction catalyzed by PcpB results in the formation of the highly reactive intermediate tetrachlorobenzoquinone.84 To protect against modification of cellular constituents by tetrachlorobenzoquinone, PcpB has evolved the ability to form a transient interaction with tetrachlorobenzoquinone reductase, which catalyzes the second step of pentachlorophenol degradation.81 This protein–protein interaction prevents release of the PcpB reaction product. In this example, the recruited PcpB appears to have emerged from evolutionary alteration of the progenitor’s substrate specificity, as well as optimization of an interaction surface on the protein.

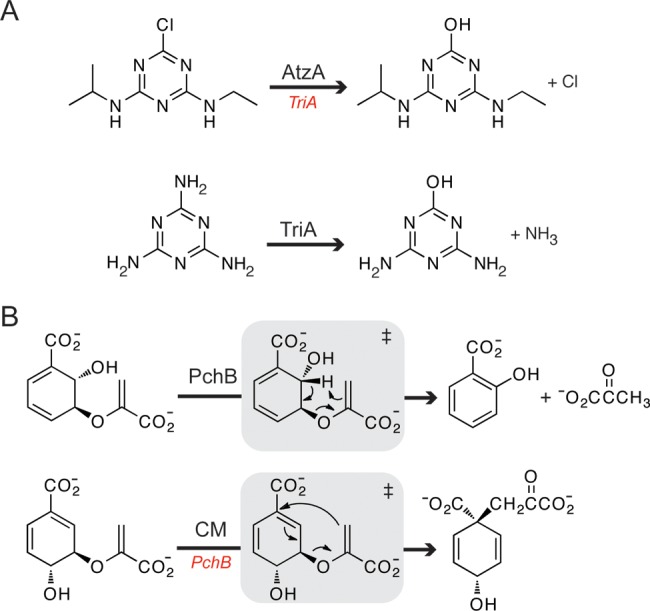

Melamine deaminase and atrazine chlorohydrolase are two enzymes that have nearly identical structures and perform similar chemistry, but have been recruited into distinct degradative pathways.85 Atrazine (2-chloro-4-N-ethylamino-6-N-isopropylamino-triazine) and melamine (2,4,6-triamino-triazine) are intensively used in the industrial synthesis of herbicides and pesticides.86 Microbial degradation of both compounds begins with the hydrolytic removal of the C2 substituent (Figure 3A). Melamine deaminase and atrazine chlorohydrolase have 98% identical sequences.85 Despite the fact that these two enzymes differ by only nine amino acid residues that are distributed throughout the scaffold, atrazine chlorohydrolase does not catalyze the deamination of melamine and melamine deaminase possesses exceedingly low chlorohydrolase activity. The lack of substantial cross-reactivity within these two highly homologous enzymes provides strong support for epistasis, leading to a very narrow evolutionary trajectory from the progenitor catalyst to the present-day enzymes.

Figure 3.

(A) Reactions catalyzed by atrazine chlorohydrolase (AtzA) and melamine deaminase (TriA), two enzymes that have 98% identical sequences. TriA possesses low levels of chlorohydrolase activity (red), but AtzA cannot catalyze the deaminase reaction. (B) Pericyclic reactions catalyzed by the highly homologous enzymes isochorismate pyruvate lyase (PchB) and chorismate mutase (CM). PchB catalyzes the chorismate mutase reaction at a low level (red), but CM is incapable of performing the PchB transformation.

A similar situation is observed by comparing the isochorismate pyruvate lyase (PchB) from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli chorismate mutase (CM). These enzymes have 20% identical sequences, adopt similar tertiary structures, and catalyze comparable pericyclic reactions.87−89 PchB catalyzes the conversion of isochorismate to salicylate and pyruvate in bacterial siderophore biosynthesis (Figure 3B). PchB can also complement a chorismate mutase deficient bacterial strain,87 by catalyzing the conversion of chorismate to prephenate with respectable efficiency (kcat/Km = 2200 M–1 s–1).90 In contrast, chorismate mutase from E. coli displays no detectable isochorismate pyruvate lyase activity.91 These findings suggest that an ancestral protein was recruited to perform both transformations, but that the subsequent evolutionary trajectory of the chorismate mutase was incompatible with retention of PchB activity. In contrast, the epistatic constraints encountered during PchB divergence allowed for the persistence of a promiscuous chorismate mutase function. Whether the ancestral polypeptide possessed both activities remains unknown; however, ancestral protein reconstruction could shed light on this issue.

In some cases, only single enzymes are recruited, whereas in other instances, entire metabolic pathways appear to have been co-opted for new function. Sequence comparisons reveal an evolutionary relationship between enzymes in the microbial arginine biosynthetic pathway and the enzymes that constitute the mammalian urea cycle.92 Four of the first five enzymes in the urea cycle catalyze reactions identical to those involved in arginine biosynthesis. The fifth enzyme, arginase, transforms arginine into ornithine and urea. Arginase is homologous to two enzymes, agmatine ureohydrolase and formiminoglutamate hydrolase, which participate in arginine and histidine degradation, respectively.93 Thus, it appears that the urea cycle of terrestrial animals was assembled from a combination of anabolic and catabolic pathways of amino acid metabolism after the transition from ocean- to land-dwelling organisms. Presumably, this recruitment process was advantageous, as it provided a mechanism for detoxifying ammonia produced by amino acid recycling. A similar example of pathway recruitment can be found in the Krebs cycle, which is postulated to have evolved from a combination of glutamate and aspartate biosynthetic enzymes.71

Experimentally Facilitated Enzyme Recruitment

Several experimental approaches have been developed to foster recruitment of enzymes for altered metabolic function. These studies highlight the scope of latent activities harbored within existing genomes and provide insight into the flexibility of modern metabolism. A powerful tool for experimental enzyme recruitment is the ASKA library, a collection of more than 4000 plasmid-borne open reading frames from E. coli.94 The ASKA collection allows controlled overproduction of each protein encoded within the E. coli genome via the powerful, IPTG-inducible T5 promoter. This collection can be used to identify proteins with latent activities capable of altering normal cellular metabolism. For example, the ASKA library was used to detect proteins whose overproduction allowed resistance to bromoacetate, a compound that mimics electrophilic toxins.95 Nine genes were identified whose overexpression resulted in bromoacetate resistance. Eight of the recruited genes encode transporters, while the ninth gene encodes UDP-N-acetylglucosamine enolpyruvoyl transferase (MurA), an essential cell wall biosynthetic enzyme. MurA was found to be the primary target of bromoacetate and overproduction restored growth by outcompeting the toxic effects of this halogenated compound.95 In a related set of experiments, bacteria harboring the ASKA collection were challenged for growth in the presence of 237 toxic compounds, including many antibacterial agents.96 In total, 61 open reading frames were identified that increased the fitness in 86 of the 237 toxic environments. The encoded proteins possessed a variety of defined and putative functions, with many postulated to possess latent enzymatic activity arising from catalytic promiscuity or substrate ambiguity. These genome-wide overproduction studies demonstrate a surprising degree of metabolic flexibility that can result from enzyme recruitment as driven by multicopy suppression.

Another genomic tool that has proven to be beneficial in experimental investigations of enzyme recruitment is the Keio collection, which constitutes ∼4000 nonessential single-gene knockout strains of E. coli K-12.97 This collection has been used to analyze the consequences associated with the loss of a single gene under different environmental conditions.98−100 Screening of the Keio collection identified 63 strains that were hypersensitive to growth in media supplemented with bromoacetate.95 The hypersensitive strains contained deletions in a variety of gene functions, one of which encoded a previously uncharacterized glutathione transferase, GstB. Biochemical investigations revealed that GstB functions as a reasonably efficient bromoacetate dehalogenase (kcat/Km = 5000 M–1 s–1). On the basis of these findings, one can predict that GstB represents a future candidate for recruitment to detoxify electrophilic small molecules. Merging the Keio collection with the ASKA library can identify intracellular enzymes with promiscuous functions. Patrick and co-workers found that growth of 20% of all Keio knockout strains can be rescued for growth on glucose minimal medium by overproduction of at least one nonidentical gene.101 In 35 of the 41 cases identified, the deleted genes and multicopy suppressors were not homologous. The authors proposed several putative mechanisms for phenotypic reversion, including isozyme overexpression, substrate ambiguity, reaction promiscuity, and metabolic bypasses, which could yield alternate sources of downstream intermediates.

The use of single-gene knockout strains in combination with the ASKA collection has also provided new insights into the plasticity of modern metabolism. In an attempt to uncover enzymes with latent triosephosphate isomerase (TIM) activity, Desai and Miller provided a TIM knockout strain with the ASKA collection and selected for genes whose overproduction restored growth on glycerol minimal medium.102 Rather than identifying a promiscuous isomerase, the investigators discovered a putative aldo-keto reductase gene that provided conditional growth. Characterization of the gene product revealed that the enzyme catalyzes the efficient, stereospecific reduction of l-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate, the enantiomer of the natural TIM substrate. The reaction provides an alternate route to the formation of dihydroxyacetone, thereby allowing a metabolic bypass of the disrupted pathway. In similar work, Copley and co-workers utilized an E. coli strain lacking 4-phosphoerythronate hydroxylase, which catalyzes the second step in pyridoxal phosphate (PLP) biosynthesis, to uncover three latent pathways for PLP production.103 Overexpression of the ASKA library in a 4-phosphoerythronate hydroxylase knockout strain identified seven genes that complemented the metabolic deficiency. Only two of the seven gene products appeared to recapitulate 4-phosphoerythronate hydroxylase activity. The other genes encode putative or established dehydratases, kinases, or hydrolases. Detailed investigation of these unexpected results demonstrated that the selected enzymes are capable of generating functional intermediates of PLP biosynthesis that lie downstream of the disrupted gene. Increasing the cellular concentration of these inefficient catalysts allows improved metabolic flux, which is sufficient for survival under the selective conditions. These experiments demonstrate that enzyme recruitment is a powerful tool for adapting to new environmental challenges and for generating altered metabolism.

Applying Enzyme Recruitment

The catalytic repertoire of contemporary enzymes is enormous. Multiple combinations of different enzymatic functions have produced complex metabolic pathways for the synthesis or degradation of structurally diverse compounds. In principle, it should be possible to design new metabolic pathways by recruiting functionally distinct enzymes to build new molecules. Indeed, modifying or extending existing pathways for the production of value-added compounds is already possible (Figure 4). Choi and co-workers have engineered a bacterium that produces short chain alkanes for gasoline production (Figure 4A).104 This was achieved by first altering the endogenous fatty acid metabolism of E. coli and then recruiting the fatty acyl CoA reductase from Clostridium acetobutylicum and the fatty aldehyde decarbonylase from Arabidopsis thaliana. The strain was further modified to produce high yields of free fatty acids and short chain fatty esters by recruiting the wax ester synthase from Acetinobacter sp. ADP1. In related work, enzyme recruitment played a key role in engineering a Pseudomonas putida strain to produce high yields of phenol (Figure 4B), an important starting material for pharmaceutical production.105 Phenol production was achieved by recruiting the tyrosine phenol lyase from Pantoea agglomerans in combination with overproducing the endogenous P. putida enzyme that catalyzes the first step of tyrosine biosynthesis.

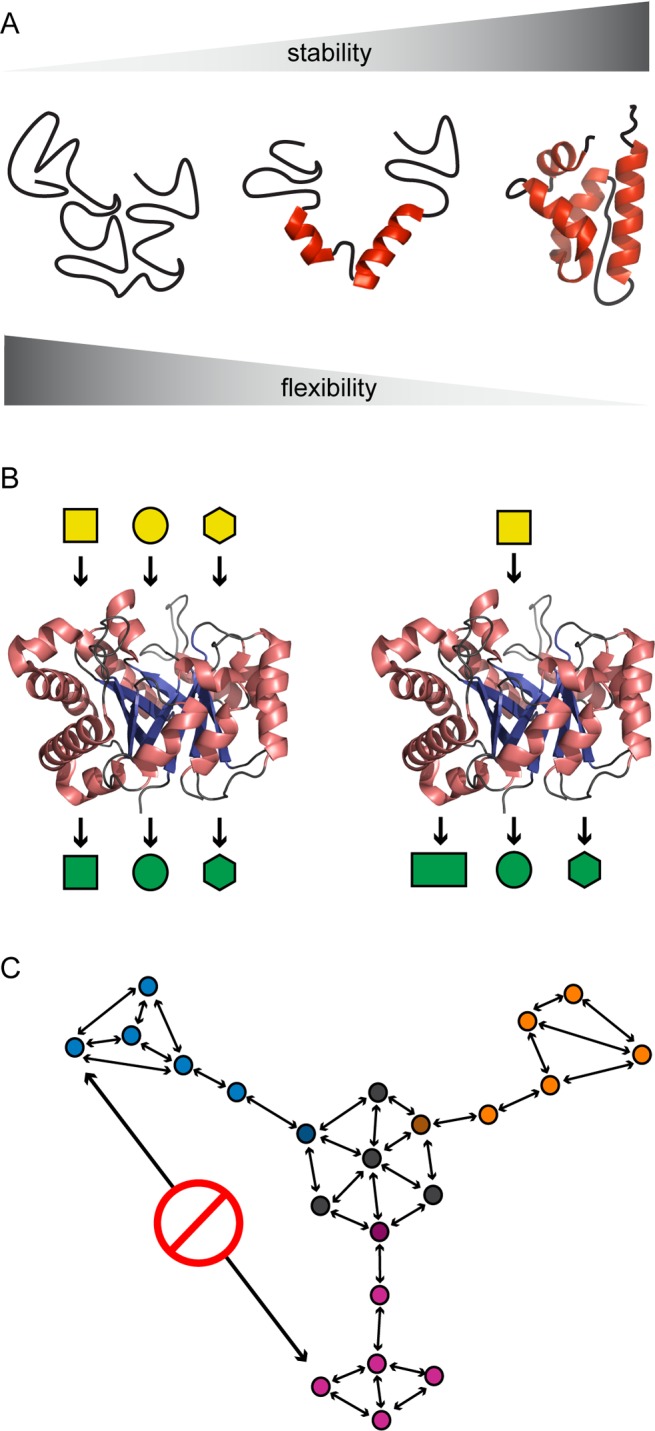

Figure 4.

Structures of representative molecules for which in vivo synthetic pathways have been successfully designed using enzyme recruitment: (A) nonane, (B) phenol, (C) the fluorinated triketide 5-fluoro-6-(1-fluoro-2-hydroxybutyl)-3-methyldihydro-2H-pyran-2,4(3H)-dione, (D) 3-hydroxypropionate, (E) styrene, and (F) 1,4-butanediol.

Many FDA-approved pharmaceutical agents contain fluorine substituents.106 Recently, the natural fluoroacetate pathway of Streptomyces cattleya was exploited to allow synthesis of structurally diverse fluorinated compounds in vitro.(107) By engineering the specificity of endogenous enzymes and recruiting the acetoacetyl CoA synthase from Streptomyces, the authors developed a new metabolic pathway for the incorporation of monomeric fluoroacetate building blocks into diverse polyketide scaffolds. The authors also succeeded in producing fluorinated triketide lactones (Figure 4C) in vivo from a fluoromalonate precursor, using a designed pathway built from a recruited ketosynthase and a modified 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase–thioesterase module.

More extensive enzyme recruitment has been utilized to convert carbon dioxide into useful compounds. The 3-hydroxypropionate/4-hydroxybutyrate pathway allows multiple thermoacidophilic archaea to assimilate carbon dioxide, in the form of bicarbonate, to generate acetyl-CoA.108 The recruitment of five consecutive enzymes from this pathway into Pyrococcus furiosus, a hyperthermophile that cannot use carbon dioxide naturally, allowed the production of 3-hydroxyproprionate in high yields (Figure 4D).109 Together, these successes demonstrate the power of using distinct recruitment strategies for the production of non-natural or non-native compounds.

Enzyme recruitment also facilitates the expansion of the degradative potential of existing pathways. Several classes of microorganisms have the ability to combat environmental contaminants such as oil spills, because they can metabolize unbranched alkanes.110,111 Although it is difficult to degrade β-methyl-branched alkanes via the β-oxidation pathway,112 multiple Pseudomonas strains can degrade short chain alkanes via the citronellol pathway.113 To expand the chain length specificity of the citronellol pathway of Pseudomonas citronellolis, this microorganism was provided with a P. putida plasmid harboring a gene cluster encoding enzymes that oxidize C6–C10n-alkanes.114 The resulting strain was able to grow on multiple n-alkane substrates. After whole genome mutagenesis of P. citronellolis and selection on n-decane medium, this pathway was further expanded to allow degradation of the multibranched alkane 2,6-dimethyl-2-octene.114

The construction of simple de novo pathways is now possible using enzyme recruitment. For example, the production of the common industrial monomeric building block styrene (Figure 4E) has been achieved in an engineered strain of E. coli.115 This required a phenylalanine ammonia lyase for the conversion of l-phenylalanine into trans-cinnamate, and a cinnamate decarboxylase to catalyze the subsequent decarboxylation of trans-cinnamate to styrene. Multiple isoenzymes from bacteria, yeast, and plants were tested for potential recruitment. The largest yield of styrene was produced by combining the phenylalanine ammonia lyase from A. thaliana with the phenylacrylate decarboxylase from Saccharomyces cerevisae in a strain of E. coli that overproduces phenylalanine. A more complex de novo pathway has been designed with the assistance of computational methods that identify suitable candidates for recruitment based on the nature of the endogenous function of the catalyst. Computational approaches predict more than 10000 potential metabolic pathways for the production of 1,4-butanediol, a useful polymer building block (Figure 4F). A single pathway was chosen from this pool on the basis of minimizing the length of the pathway, minimizing the number of unknown enzymatic steps, and predicting the thermodynamic likelihood of each reaction.116 The resulting pathway combines five heterologous enzymatic conversions integrated into natural E. coli metabolic pathways and results in the production of 18 g/L 1,4-butanediol.

A de novo-designed remediation pathway for paraoxon, a powerful insecticide and an efficient acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, has been developed via enzyme recruitment. A synthetic operon assembled from genes of multiple organisms in combination with a natural operon from Pseudomonas sp. allows P. putida to efficiently degrade large amounts of paraoxon.117 The synthetic operon encodes the organophosphate hydrolase gene from Flavobacterium sp., which hydrolyzes paraoxon into p-nitrophenol and diethyl phosphate. Diethyl phosphate is then converted to ethyl phosphate and subsequently to orthophosphate by the sequential action of two additional operon components, the phosphodiesterase from Delftia acidovorans and the alkaline phosphatase from P. aeruginosa. p-Nitrophenol is processed by the natural pnp operon from Pseudomonas sp., which encodes five enzymes catalyzing the transformation of p-nitrophenol to β-ketoadipate. This intermediate is further processed to succinyl-CoA and acetyl-CoA by the natural tricarbonic acid cycle of the host strain P. putida.

Future Perspectives

The study of enzyme recruitment has illuminated our understanding of the natural processes that drive the evolution of molecular function. It has also empowered the application of such knowledge to engineer new catalysts and new metabolic pathways. Where does the future lie? A major stumbling block in applying enzyme recruitment for useful new purposes remains the initial identification of the desired catalytic activity. Several computational approaches currently under development may help overcome this limitation. One promising area is computational protein design, which offers the possibility of creating enzymes for both natural and non-natural chemical transformations.118−121 Although the enzymes designed to date generally possess activities that are low compared to those of natural enzymes,118,122 these scaffolds serve as attractive starting points for further directed evolution123−125 that could lead to optimized performance in vitro and in vivo. Bioinformatics methods that facilitate the organization of enzymes into superfamilies based on common tertiary structure and a fully or partially shared mechanism have also emerged.126−128 While this information has been largely used to assign activities to genes of unknown function,129,130 it also provides a database of homologous proteins that can be searched for candidate enzymes with the potential to be recruited for a specific type of chemical transformation.

The computational approaches described above are complemented by experimental methods to identify potential candidates for enzyme recruitment. The use of the aforementioned E. coli ASKA collection, in a high-throughput format, provides one source for discovering latent enzyme activities. An extension of the ASKA library can also be envisioned. Developing new open reading frame libraries that include genes from the more than 1000 organisms whose genomes have been sequenced would substantially expand the search landscape.131 A further expansion of the search zone could be achieved by creating robust environmental DNA libraries using methods established in the past decade.132,133 These approaches, while potentially powerful, require important advances in developing universal plasmid systems and host organisms to afford efficient heterologous production of library-encoded gene products in vivo.

Loosening the epistatic constraints inherent in modern enzymes as a result of their evolutionary history offers another approach that may facilitate the identification of latent activities. Ancestral proteins are thought to have possessed greater functional plasticity than their modern counterparts.134 Ancestral sequence reconstruction, using weighted parsimony and maximum likelihood methods, allows one to resurrect plausible models of extinct protein sequences in the laboratory.135−137 The extent to which ancestral reconstruction of ancient proteins increases the likelihood of revealing latent functions within a protein superfamily remains to be determined. At the very least, however, such a procedure promises to restore evolvability within a scaffold. Targeted ancestral sequence reconstructions within a specific protein superfamily could yield polypeptides that share potential mechanistic capabilities found within the modern superfamily. To widen the catalytic repertoire, ancestrally reconstructed sequences from multiple, mechanistically distinct protein superfamilies could be pooled to generate a more complex library.

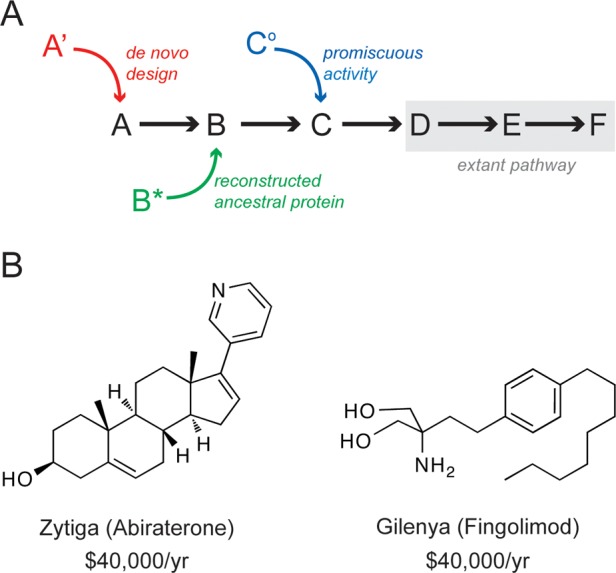

The strategies outlined above could yield a variety of low-activity enzymes that may be assembled into a new pathway (Figure 5A). To date, successes in novel metabolic pathway development have largely centered on short pathways115−117 and/or the recruitment of enzymes that promote transformations currently found in nature.104,105,107,109,114 To generate more complex pathways, however, the recruitment of enzymes that catalyze non-natural chemical reactions will likely be necessary. Examples of such reactions include metal-catalyzed cross coupling transformations and olefin metathesis, reactions for which efficient protein catalysts are not presently available.138−141 The identification of enzymes for these reactions, which are heavily used in pharmaceutical development, could facilitate the design of metabolic pathways for the microbial production of drugs. Two potentially attractive candidates are Zytiga and Gilenya (Figure 5B), both of which bear structural resemblance to natural metabolites and are prohibitively expensive, with an estimated annual cost of $40000 per patient.142,143

Figure 5.

(A) Pathway design using enzymes recruited as a result of de novo design (red) that arise from ancestral reconstruction (green) or that possess promiscuous activities (blue). These catalysts can be installed into preexisting metabolic pathways (gray). (B) Structures of two pharmaceutical agents, Zytiga (Abiraterone) and Gilenya (Fingolimod), that represent attractive targets for future metabolic pathway design efforts with their annual treatment cost indicated.

The study of enzyme recruitment has a long history, which includes both experimental and phylogenetic approaches. This field is sufficiently mature such that applications of enzyme recruitment for new catalyst discovery and pathway development are now routine. Further progress is likely to be stimulated by the convergence of molecular evolutionary theory, directed enzyme evolution strategies, and computational protein and pathway design. From this effort, it is reasonable to expect impressive advances over the next decade culminating in the emergence of new organisms with genomes tailored for specific metabolic purposes.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Kevin Desai, Christoph Giese, Donald Hilvert, and Darin Rokyta for support and helpful discussions during the preparation of this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Work in the Miller laboratory is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (DK081358), an Innovation Award from the American Diabetes Association (1-12-IN-30), and Florida State University. C.S. is supported by an ETH postdoctoral fellowship and a research grant from the Swiss National Foundation (310030B-138654).

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

References

- Jensen R. A. (1976) Enzyme recruitment in evolution of new function. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 30, 409–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano-Anolles G.; Yafremava L. S.; Gee H.; Caetano-Anolles D.; Kim H. S.; Mittenthal J. E. (2009) The origin and evolution of modern metabolism. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 41, 285–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlt J. A.; Babbitt P. C. (2001) Divergent evolution of enzymatic function: Mechanistically diverse superfamilies and functionally distinct suprafamilies. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70, 209–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almonacid D. E.; Babbitt P. C. (2011) Toward mechanistic classification of enzyme functions. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 15, 435–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.; Francklyn C.; Carter C. W. Jr. (2013) Aminoacylating urzymes challenge the RNA world hypothesis. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 26856–26863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham Y.; Kuhlman B.; Butterfoss G. L.; Hu H.; Weinreb V.; Carter C. W. Jr. (2010) Tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase Urzyme: A model to recapitulate molecular evolution and investigate intramolecular complementation. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 38590–38601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.; Weinreb V.; Francklyn C.; Carter C. W. Jr. (2011) Histidyl-tRNA synthetase urzymes: Class I and II aminoacyl tRNA synthetase urzymes have comparable catalytic activities for cognate amino acid activation. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 10387–10395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebert D. W.; Dieter M. Z. (2000) The evolution of drug metabolism. Pharmacology 61, 124–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copley S. D. (2009) Evolution of efficient pathways for degradation of anthropogenic chemicals. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 559–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake J. W. (1991) A constant rate of spontaneous mutation in DNA-based microbes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 7160–7164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock M. C., and Bürger R. (2004) Fixation of New Mutations in Small Populations, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K. [Google Scholar]

- Keightley P. D.; Lynch M. (2003) Toward a realistic model of mutations affecting fitness. Evolution 57, 683–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood W. A. (1966) Carbohydrate metabolism. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 35, 521–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson R. P.; Roth J. R. (1977) Tandem genetic duplications in phage and bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 31, 473–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondrashov F. A. (2012) Gene duplication as a mechanism of genomic adaptation to a changing environment. Proc. Biol. Sci. 279, 5048–5057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P.; Roth J. (1981) Spontaneous tandem genetic duplications in Salmonella typhimurium arise by unequal recombination between rRNA (rrn) cistrons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 78, 3113–3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson D. I.; Hughes D. (2009) Gene amplification and adaptive evolution in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Genet. 43, 167–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott K. T.; Cuff L. E.; Neidle E. L. (2013) Copy number change: Evolving views on gene amplification. Future Microbiol. 8, 887–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersson M. E.; Sun S.; Andersson D. I.; Berg O. G. (2009) Evolution of new gene functions: Simulation and analysis of the amplification model. Genetica 135, 309–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S.; Ke R.; Hughes D.; Nilsson M.; Andersson D. I. (2012) Genome-wide detection of spontaneous chromosomal rearrangements in bacteria. PLoS One 7, e42639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth J. R., Benson N., Galitski T., Haack K., Lawrence J. G., and Miesel L. (1996) Rearrangements of the Bacterial Chromosome: Formation and Applications, 2nd ed., American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Edlund T.; Grundstrom T.; Normark S. (1979) Isolation and characterization of DNA repetitions carrying the chromosomal β-lactamase gene of Escherichia coli K-12. Mol. Gen. Genet. 173, 115–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C. J.; Todd K. M.; Rosenzweig R. F. (1998) Multiple duplications of yeast hexose transport genes in response to selection in a glucose-limited environment. Mol. Biol. Evol. 15, 931–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z.; Cheng C. H.; Zhang J.; Cao L.; Chen L.; Zhou L.; Jin Y.; Ye H.; Deng C.; Dai Z.; Xu Q.; Hu P.; Sun S.; Shen Y. (2008) Transcriptomic and genomic evolution under constant cold in Antarctic notothenioid fish. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 12944–12949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F.; Pecina D. A.; Kelly S. D.; Kim S. H.; Kemner K. M.; Long D. T.; Marsh T. L. (2010) Biosequestration via cooperative binding of copper by Ralstonia pickettii. Environ. Technol. 31, 1045–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster-Bockler B.; Conrad D.; Bateman A. (2010) Dosage sensitivity shapes the evolution of copy-number varied regions. PLoS One 5, e9474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins A. R.; Lamb H. K.; Radford A.; Moore J. D. (1994) Evolution of transcription-regulating proteins by enzyme recruitment: Molecular models for nitrogen metabolite repression and ethanol utilisation in eukaryotes. Gene 146, 145–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigby P. W.; Burleigh B. D. Jr.; Hartley B. S. (1974) Gene duplication in experimental enzyme evolution. Nature 251, 200–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. M. (1992) Analyzing the mosaic structure of genes. J. Mol. Evol. 34, 126–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughter J. P.; Stewart G. J. (1989) Genetic exchange in the environment. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 55, 15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overballe-Petersen S.; Harms K.; Orlando L. A.; Mayar J. V.; Rasmussen S.; Dahl T. W.; Rosing M. T.; Poole A. M.; Sicheritz-Ponten T.; Brunak S.; Inselmann S.; de Vries J.; Wackernagel W.; Pybus O. G.; Nielsen R.; Johnsen P. J.; Nielsen K. M.; Willerslev E. (2013) Bacterial natural transformation by highly fragmented and damaged DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 19860–19865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. W.; Feng D. F.; Doolittle R. F. (1992) Evolution by acquisition: The case for horizontal gene transfers. Trends Biochem. Sci. 17, 489–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprague G. F. Jr. (1991) Genetic exchange between kingdoms. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1, 530–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doolittle R. F.; Feng D. F.; Anderson K. L.; Alberro M. R. (1990) A naturally occurring horizontal gene transfer from a eukaryote to a prokaryote. J. Mol. Evol. 31, 383–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokuriki N.; Tawfik D. S. (2009) Protein dynamism and evolvability. Science 324, 203–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokuriki N.; Stricher F.; Serrano L.; Tawfik D. S. (2008) How protein stability and new functions trade off. PLoS Comput. Biol. 4, e1000002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal C.; Papp B.; Lercher M. J. (2006) An integrated view of protein evolution. Nat. Rev. Genet. 7, 337–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellus-Gur E.; Toth-Petroczy A.; Elias M.; Tawfik D. S. (2013) What makes a protein fold amenable to functional innovation? Fold polarity and stability trade-offs. J. Mol. Biol. 425, 2609–2621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom J. D.; Silberg J. J.; Wilke C. O.; Drummond D. A.; Adami C.; Arnold F. H. (2005) Thermodynamic prediction of protein neutrality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 606–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokuriki N.; Tawfik D. S. (2009) Stability effects of mutations and protein evolvability. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 19, 596–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePristo M. A.; Weinreich D. M.; Hartl D. L. (2005) Missense meanderings in sequence space: A biophysical view of protein evolution. Nat. Rev. Genet. 6, 678–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camps M.; Herman A.; Loh E.; Loeb L. A. (2007) Genetic constraints on protein evolution. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 42, 313–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom J. D.; Labthavikul S. T.; Otey C. R.; Arnold F. H. (2006) Protein stability promotes evolvability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 5869–5874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorick M. M.; Wagner G. P. (2011) Protein structural modularity and robustness are associated with evolvability. Genome Biol. Evol. 3, 456–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields P. A. (2001) Review: Protein function at thermal extremes: Balancing stability and flexibility. Comp. Biochem. Physiol., Part A: Mol. Integr. Physiol. 129, 17–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang K. E.; Dill K. A. (1998) Native protein fluctuations: The conformational-motion temperature and the inverse correlation of protein flexibility with protein stability. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 16, 397–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vihinen M. (1987) Relationship of protein flexibility to thermostability. Protein Eng. 1, 477–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh J. A.; Teichmann S. A. (2014) Parallel dynamics and evolution: Protein conformational fluctuations and assembly reflect evolutionary changes in sequence and structure. BioEssays 36, 209–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams P. D.; Pollock D. D.; Goldstein R. A. (2006) Functionality and the evolution of marginal stability in proteins: Inferences from lattice simulations. Evol. Bioinf. Online 2, 91–101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taverna D. M.; Goldstein R. A. (2002) Why are proteins marginally stable?. Proteins 46, 105–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagano N.; Orengo C. A.; Thornton J. M. (2002) One fold with many functions: The evolutionary relationships between TIM barrel families based on their sequences, structures and functions. J. Mol. Biol. 321, 741–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlt J. A.; Raushel F. M. (2003) Evolution of function in (β/α)8-barrel enzymes. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 7, 252–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khersonsky O.; Roodveldt C.; Tawfik D. S. (2006) Enzyme promiscuity: Evolutionary and mechanistic aspects. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 10, 498–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khersonsky O.; Tawfik D. S. (2010) Enzyme promiscuity: A mechanistic and evolutionary perspective. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 79, 471–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien P. J.; Herschlag D. (1999) Catalytic promiscuity and the evolution of new enzymatic activities. Chem. Biol. 6, 91–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshland D. E. (1958) Application of a Theory of Enzyme Specificity to Protein Synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 44, 98–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegeman G. D.; Rosenberg S. L. (1970) The evolution of bacterial enzyme systems. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 24, 429–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip S. H.; Matsumura I. (2013) Substrate Ambiguous Enzymes within the Escherichia coli Proteome Offer Different Evolutionary Solutions to the Same Problem. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2001–2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia B.; Cheong G. W.; Zhang S. (2013) Multifunctional enzymes in archaea: Promiscuity and moonlight. Extremophiles 17, 193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khersonsky O.; Malitsky S.; Rogachev I.; Tawfik D. S. (2011) Role of chemistry versus substrate binding in recruiting promiscuous enzyme functions. Biochemistry 50, 2683–2690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harms M. J.; Thornton J. W. (2013) Evolutionary biochemistry: Revealing the historical and physical causes of protein properties. Nat. Rev. Genet. 14, 559–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bershtein S.; Segal M.; Bekerman R.; Tokuriki N.; Tawfik D. S. (2006) Robustness-epistasis link shapes the fitness landscape of a randomly drifting protein. Nature 444, 929–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehner B. (2011) Molecular mechanisms of epistasis within and between genes. Trends Genet. 27, 323–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen M. S.; Kemena C.; Vlasov P. K.; Notredame C.; Kondrashov F. A. (2012) Epistasis as the primary factor in molecular evolution. Nature 490, 535–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong L. I.; Suchard M. A.; Bloom J. D. (2013) Stability-mediated epistasis constrains the evolution of an influenza protein. Elife 2, e00631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunzer M.; Miller S. P.; Felsheim R.; Dean A. M. (2005) The biochemical architecture of an ancient adaptive landscape. Science 310, 499–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Y.; Gu X. (2010) Genome factor and gene pleiotropy hypotheses in protein evolution. Biol. Direct 5, 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinreich D. M.; Delaney N. F.; Depristo M. A.; Hartl D. L. (2006) Darwinian evolution can follow only very few mutational paths to fitter proteins. Science 312, 111–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford I. P. (1975) Gene rearrangements in the evolution of the tryptophan synthetic pathway. Bacteriol. Rev. 39, 87–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane J. F.; Holmes W. M.; Jensen R. A. (1972) Metabolic interlock. The dual function of a folate pathway gene as an extra-operonic gene of tryptophan biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 247, 1587–1596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melendez-Hevia E.; Waddell T. G.; Cascante M. (1996) The puzzle of the Krebs citric acid cycle: Assembling the pieces of chemically feasible reactions, and opportunism in the design of metabolic pathways during evolution. J. Mol. Evol. 43, 293–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fondi M.; Brilli M.; Emiliani G.; Paffetti D.; Fani R. (2007) The primordial metabolism: An ancestral interconnection between leucine, arginine, and lysine biosynthesis. BMC Evol. Biol. 7, 3–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wistow G. (1993) Lens crystallins: Gene recruitment and evolutionary dynamism. Trends Biochem. Sci. 18, 301–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunaway-Mariano D.; Babbitt P. C. (1994) On the origins and functions of the enzymes of the 4-chlorobenzoate to 4-hydroxybenzoate converting pathway. Biodegradation 5, 259–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piatigorsky J.; Kantorow M.; Gopal-Srivastava R.; Tomarev S. I. (1994) Recruitment of enzymes and stress proteins as lens crystallins. EXS 71, 241–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wackett L. P. (1995) Recruitment of co-metabolic enzymes for environmental detoxification of organohalides. Environ. Health Perspect. 103, 45–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen R. A.; Gu W. (1996) Evolutionary recruitment of biochemically specialized subdivisions of Family I within the protein superfamily of aminotransferases. J. Bacteriol. 178, 2161–2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copley S. D. (1998) Microbial dehalogenases: Enzymes recruited to convert xenobiotic substrates. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2, 613–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd A. E.; Orengo C. A.; Thornton J. M. (1999) Evolution of protein function, from a structural perspective. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 3, 548–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd A. E.; Orengo C. A.; Thornton J. M. (2001) Evolution of function in protein superfamilies, from a structural perspective. J. Mol. Biol. 307, 1113–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadid I.; Rudolph J.; Hlouchova K.; Copley S. D. (2013) Sequestration of a highly reactive intermediate in an evolving pathway for degradation of pentachlorophenol. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 2182–2190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baader E. W.; Bauer H. J. (1951) Industrial intoxication due to pentachlorophenol. Ind. Med. Surg. 20, 286–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hlouchova K.; Rudolph J.; Pietari J. M.; Behlen L. S.; Copley S. D. (2012) Pentachlorophenol hydroxylase, a poorly functioning enzyme required for degradation of pentachlorophenol by Sphingobium chlorophenolicum. Biochemistry 51, 3848–3860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai M.; Rogers J. B.; Warner J. R.; Copley S. D. (2003) A previously unrecognized step in pentachlorophenol degradation in Sphingobium chlorophenolicum is catalyzed by tetrachlorobenzoquinone reductase (PcpD). J. Bacteriol. 185, 302–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seffernick J. L.; de Souza M. L.; Sadowsky M. J.; Wackett L. P. (2001) Melamine deaminase and atrazine chlorohydrolase: 98% identical but functionally different. J. Bacteriol. 183, 2405–2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wackett L. P.; Sadowsky M. J.; Martinez B.; Shapir N. (2002) Biodegradation of atrazine and related s-triazine compounds: From enzymes to field studies. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 58, 39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaille C.; Kast P.; Haas D. (2002) Salicylate biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Purification and characterization of PchB, a novel bifunctional enzyme displaying isochorismate pyruvate-lyase and chorismate mutase activities. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 21768–21775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacBeath G.; Kast P.; Hilvert D. (1998) A small, thermostable, and monofunctional chorismate mutase from the archaeon Methanococcus jannaschii. Biochemistry 37, 10062–10073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu W.; Williams D. S.; Aldrich H. C.; Xie G.; Gabriel D. W.; Jensen R. A. (1997) The aroQ and pheA domains of the bifunctional P-protein from Xanthomonas campestris in a context of genomic comparison. Microb. Comp. Genomics 2, 141–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Künzler D. E.; Sasso S.; Gamper M.; Hilvert D.; Kast P. (2005) Mechanistic insights into the isochorismate pyruvate lyase activity of the catalytically promiscuous PchB from combinatorial mutagenesis and selection. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 32827–32834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Künzler D. E. (2006) Taking Advantage of the Catalytic Promiscuity of Isochorismate Pyruvate Lyase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Mechanistic Studies and Evolution into an Efficient Chorismate Mutase, pp 1–148, Department of Chemistry and Applied Biosciences, ETH Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Takiguchi M.; Matsubasa T.; Amaya Y.; Mori M. (1989) Evolutionary aspects of urea cycle enzyme genes. BioEssays 10, 163–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouzounis C. A.; Kyrpides N. C. (1994) On the evolution of arginases and related enzymes. J. Mol. Evol. 39, 101–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa M.; Ara T.; Arifuzzaman M.; Ioka-Nakamichi T.; Inamoto E.; Toyonaga H.; Mori H. (2005) Complete set of ORF clones of Escherichia coli ASKA library (a complete set of E. coli K-12 ORF archive): Unique resources for biological research. DNA Res. 12, 291–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai K. K.; Miller B. G. (2010) Recruitment of genes and enzymes conferring resistance to the nonnatural toxin bromoacetate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 17968–17973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soo V. W.; Hanson-Manful P.; Patrick W. M. (2011) Artificial gene amplification reveals an abundance of promiscuous resistance determinants in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 1484–1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba T.; Ara T.; Hasegawa M.; Takai Y.; Okumura Y.; Baba M.; Datsenko K. A.; Tomita M.; Wanner B. L.; Mori H. (2006) Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: The Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2, 2006.0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black S. L.; Dawson A.; Ward F. B.; Allen R. J. (2013) Genes Required for Growth at High Hydrostatic Pressure in Escherichia coli K-12 Identified by Genome-Wide Screening. PLoS One 8, e73995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayashiki T.; Mori H. (2013) Genome-wide screening with hydroxyurea reveals a link between nonessential ribosomal proteins and reactive oxygen species production. J. Bacteriol. 195, 1226–1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baisa G.; Stabo N. J.; Welch R. A. (2013) Characterization of Escherichia colid-cycloserine transport and resistant mutants. J. Bacteriol. 195, 1389–1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick W. M.; Quandt E. M.; Swartzlander D. B.; Matsumura I. (2007) Multicopy suppression underpins metabolic evolvability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 2716–2722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai K. K.; Miller B. G. (2008) A metabolic bypass of the triosephosphate isomerase reaction. Biochemistry 47, 7983–7985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.; Kershner J. P.; Novikov Y.; Shoemaker R. K.; Copley S. D. (2010) Three serendipitous pathways in E. coli can bypass a block in pyridoxal-5′-phosphate synthesis. Mol. Syst. Biol. 6, 436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y. J.; Lee S. Y. (2013) Microbial production of short-chain alkanes. Nature 502, 571–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wierckx N. J.; Ballerstedt H.; de Bont J. A.; Wery J. (2005) Engineering of solvent-tolerant Pseudomonas putida S12 for bioproduction of phenol from glucose. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 8221–8227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller K.; Faeh C.; Diederich F. (2007) Fluorine in pharmaceuticals: Looking beyond intuition. Science 317, 1881–1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker M. C.; Thuronyi B. W.; Charkoudian L. K.; Lowry B.; Khosla C.; Chang M. C. (2013) Expanding the fluorine chemistry of living systems using engineered polyketide synthase pathways. Science 341, 1089–1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg I. A.; Kockelkorn D.; Buckel W.; Fuchs G. (2007) A 3-hydroxypropionate/4-hydroxybutyrate autotrophic carbon dioxide assimilation pathway in Archaea. Science 318, 1782–1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller M. W.; Schut G. J.; Lipscomb G. L.; Menon A. L.; Iwuchukwu I. J.; Leuko T. T.; Thorgersen M. P.; Nixon W. J.; Hawkins A. S.; Kelly R. M.; Adams M. W. (2013) Exploiting microbial hyperthermophilicity to produce an industrial chemical, using hydrogen and carbon dioxide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 5840–5845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zobell C. E. (1946) Action of microorganisms on hydrocarbons. Bacteriol. Rev. 10, 1–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atlas R. M. (1988) Biodegradation of hydrocarbons in the environment. Basic Life Sci. 45, 211–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirnik M. P. (1977) Microbial oxidation of methyl branched alkanes. CRC Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 5, 413–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantwell S. G.; Lau E. P.; Watt D. S.; Fall R. R. (1978) Biodegradation of acyclic isoprenoids by Pseudomonas species. J. Bacteriol. 135, 324–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fall R. R.; Brown J. L.; Schaeffer T. L. (1979) Enzyme recruitment allows the biodegradation of recalcitrant branched hydrocarbons by Pseudomonas citronellolis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 38, 715–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna R.; Nielsen D. R. (2011) Styrene biosynthesis from glucose by engineered E. coli. Metab. Eng. 13, 544–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yim H.; Haselbeck R.; Niu W.; Pujol-Baxley C.; Burgard A.; Boldt J.; Khandurina J.; Trawick J. D.; Osterhout R. E.; Stephen R.; Estadilla J.; Teisan S.; Schreyer H. B.; Andrae S.; Yang T. H.; Lee S. Y.; Burk M. J.; Van Dien S. (2011) Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for direct production of 1,4-butanediol. Nat. Chem. Biol. 7, 445–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Pena Mattozzi M.; Tehara S. K.; Hong T.; Keasling J. D. (2006) Mineralization of paraoxon and its use as a sole C and P source by a rationally designed catabolic pathway in Pseudomonas putida. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 6699–6706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilvert D. (2013) Design of protein catalysts. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 82, 447–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kries H.; Blomberg R.; Hilvert D. (2013) De novo enzymes by computational design. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 17, 221–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss G.; Celebi-Olcum N.; Moretti R.; Baker D.; Houk K. N. (2013) Computational enzyme design. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 52, 5700–5725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker D. (2010) An exciting but challenging road ahead for computational enzyme design. Protein Sci. 19, 1817–1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woycechowsky K. J.; Vamvaca K.; Hilvert D. (2007) Novel enzymes through design and evolution. Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas Mol. Biol. 75, 241–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomberg R.; Kries H.; Pinkas D. M.; Mittl P. R.; Grutter M. G.; Privett H. K.; Mayo S. L.; Hilvert D. (2013) Precision is essential for efficient catalysis in an evolved Kemp eliminase. Nature 503, 418–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giger L.; Caner S.; Obexer R.; Kast P.; Baker D.; Ban N.; Hilvert D. (2013) Evolution of a designed retro-aldolase leads to complete active site remodeling. Nat. Chem. Biol. 9, 494–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khersonsky O.; Rothlisberger D.; Wollacott A. M.; Murphy P.; Dym O.; Albeck S.; Kiss G.; Houk K. N.; Baker D.; Tawfik D. S. (2011) Optimization of the in-silico-designed kemp eliminase KE70 by computational design and directed evolution. J. Mol. Biol. 407, 391–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chothia C.; Finkelstein A. V. (1990) The classification and origins of protein folding patterns. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 59, 1007–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murzin A. G.; Brenner S. E.; Hubbard T.; Chothia C. (1995) SCOP: A structural classification of proteins database for the investigation of sequences and structures. J. Mol. Biol. 247, 536–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlt J. A.; Allen K. N.; Almo S. C.; Armstrong R. N.; Babbitt P. C.; Cronan J. E.; Dunaway-Mariano D.; Imker H. J.; Jacobson M. P.; Minor W.; Poulter C. D.; Raushel F. M.; Sali A.; Shoichet B. K.; Sweedler J. V. (2011) The Enzyme Function Initiative. Biochemistry 50, 9950–9962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlt J. A.; Babbitt P. C.; Jacobson M. P.; Almo S. C. (2012) Divergent evolution in enolase superfamily: Strategies for assigning functions. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 29–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S.; Kumar R.; Sakai A.; Vetting M. W.; Wood B. M.; Brown S.; Bonanno J. B.; Hillerich B. S.; Seidel R. D.; Babbitt P. C.; Almo S. C.; Sweedler J. V.; Gerlt J. A.; Cronan J. E.; Jacobson M. P. (2013) Discovery of new enzymes and metabolic pathways by using structure and genome context. Nature 502, 698–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koonin E. V.; Wolf Y. I. (2008) Genomics of bacteria and archaea: The emerging dynamic view of the prokaryotic world. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 6688–6719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady S. F. (2007) Construction of soil environmental DNA cosmid libraries and screening for clones that produce biologically active small molecules. Nat. Protoc. 2, 1297–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabree Z. L., Rondon M. R., and Handelsman J. (2009) Metagenomics, 3rd ed., Academic Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Ycas M. (1974) On earlier states of the biochemical system. J. Theor. Biol. 44, 145–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. M.; Xu S. (2005) A penalized maximum likelihood method for estimating epistatic effects of QTL. Heredity 95, 96–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshi J. M.; Goldstein R. A. (1996) Probabilistic reconstruction of ancestral protein sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 42, 313–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K.; Peterson D.; Peterson N.; Stecher G.; Nei M.; Kumar S. (2011) MEGA5: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 2731–2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer C.; Gillingham D. G.; Ward T. R.; Hilvert D. (2011) An artificial metalloenzyme for olefin metathesis. Chem. Commun. 47, 12068–12070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo C.; Ringenberg M. R.; Gnandt D.; Wilson Y.; Ward T. R. (2011) Artificial metalloenzymes for olefin metathesis based on the biotin-(strept)avidin technology. Chem. Commun. 47, 12065–12067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J. C. (2013) Artificial Metalloenzymes and Metallopeptide Catalysts for Organic Synthesis. ACS Catal. 3, 2954–2975. [Google Scholar]

- Kohler V.; Wilson Y. M.; Durrenberger M.; Ghislieri D.; Churakova E.; Quinto T.; Knorr L.; Haussinger D.; Hollmann F.; Turner N. J.; Ward T. R. (2013) Synthetic cascades are enabled by combining biocatalysts with artificial metalloenzymes. Nat. Chem. 5, 93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford E. D.; Rove K. O. (2012) Advanced prostate cancer: Therapeutic sequencing, outcomes, and cost implications. Am. J. of Manag. Care 18, 250–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo C.; Izquierdo G.; Garcia-Ruiz A.; Granell M.; Brosa M. (2013) Cost minimisation analysis of fingolimod vs natalizumab as a second line of treatment for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Neurologia 13, DOI 10.1016/j.nrl.2013.1004.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]