Abstract

X-ray luminescent nanoparticles (NPs), including lanthanide fluorides, have been evaluated for application to deep tissue in vivo molecular imaging using optical tomography. A combination of high material density, higher atomic number and efficient NIR luminescence from compatible lanthanide dopant ions indicates that particles that consist of ALnF4 (A = alkaline, Ln = lanthanide element) may offer a very attractive class of materials for high resolution, deep tissue imaging with X-ray excitation. NaGdF4:Eu3+ NPs produced an X-ray excited luminescence that was among the most efficient of nanomaterials that have been studied thus far. We have systematically studied factors such as (a) the crystal structure that changes the lattice environment of the doped Eu3+ ions within the unit cell; and extrinsic factors such as (b) a gold coating (with attendant biocompatibility) that couples to a plasmonic excitation, and (c) changes in the NPs surface properties via changes in the pH of the suspending medium—all with a significant impact on the X-ray excited luminescence of NaGdF4:Eu3+NPs. The luminescence from an optimally doped hexagonal phase NaGdF4:Eu3+ nanoparticle was 25% more intense compared to that of a cubic structure. We observed evidence of plasmonic reabsorption of midwavelength emission by a gold coating on hexagonal NaGdF4:Eu3+ NPs; fortunately, the NaGdF4:Eu3+ @Au core–shell NPs retained the efficient 5D0→7F4 NIR (692 nm) luminescence. The NaGdF4:Eu3+ NPs exhibited sensitivity to the ambient pH when excited by X-rays, an effect not seen with UV excitation. The sensitivity to the local environment can be understood in terms of the sensitivity of the excitons that are generated by the high energy X-rays (and not by UV photons) to crystal structure and to the surface state of the particles.

Introduction

Scintillation materials that emit visible photons when irradiated with γ- or X-rays constitute an extreme form of optical down-conversion. Lanthanides as dopants are often a good choice for such materials, as they have high atomic number and suitable electronic energy states to emit photons in the UV, visible, and near-infrared (NIR) region of the electromagnetic spectrum. Elements with a high atomic number in a host matrix generate sufficiently high-energy electrons that can be down-converted in energy by an appropriate choice of lanthanide sensitizers and emitters. Lanthanide-doped nanophosphors, especially up-converting nanophosphors,1−5 are increasingly finding application in in vitro and in vivo imaging. Recently, nanophosphors have been explored as agents in radiological applications, especially in vivo tumor detection.6−9 The combination of insignificant scattering of X-rays in tissues, and the high tissue penetration of NIR optical photons emitted from appropriate phosphors, opens up the possibility of achieving deep tissue optical imaging in vivo with unprecedented spatial resolution. As X-ray scattering in tissues is negligible, optical imaging is only restricted by the width of the X-ray beam. Because the X-ray excitation path is well-defined, an accurate reconstruction of the target region of interest with a high degree of spatial resolution is possible by employing X-ray luminescence optical tomography (XLOT).10 Even with the relatively small number of photons that can be generated from optically emitting nanoparticles following excitation by a standard X-ray source, a good signal-to-noise ratio for reconstruction of the luminescent emission region can be obtained, in which the optical signal is proportional to the X-ray luminescent particle concentration.11 Using this approach, in vitro imaging of nanoparticles in tissue phantoms has already been demonstrated for metal oxides (Gd2O3:Eu)7 and for oxysulfides(Gd2O2S:Eu).12,13

New materials with enhanced luminescence properties are very desirable for XLOT applications. Although it has been shown that low bandgap materials (e.g., ZnS:Ag) offer a greater efficiency as scintillator materials, fluoride materials offer other advantages in terms of high density, mechanical hardness, and radiation hardness.14,15 A fluoride matrix offers efficient transfer pathways for self-trapped excitons (STE) to the activator ions.16 Therefore, selecting a rare-earth activator promotes tuning of the emission upon X-ray excitation, which opens up new possibilities for in vivo applications for nanoparticles using these activated fluoride materials.17 As an example, BaYF5:Eu3+ nanoparticles (15–20 nm) have recently been shown to be efficient markers for in vivo radioluminescence imaging.18

Fluoride-based ALnF4 (A = alkaline; Ln = lanthanide) materials are preferred hosts for optically emitting lanthanide phosphors since they have low phonon energy states.19−21 ALnF4 is the preferred matrix for down-conversion, as it is a wide band gap material with a band gap in the range 9–10 eV.22 The rare-earth dopant causes a contraction of the host material that results in unit-cell densities of as high as 8.44 g/cm3 with attendant increase in X-ray absorption.23 In addition, rare-earth doping can serve as both an activator and sensitizer center. With the combined favorable properties that arise from rare-earth doping, improved materials for XLOT imaging applications may be identified.

Gadolinium serves as an excellent photosensitizer for UV-excited down-converting lanthanide emitters.24,25 The Gd3+–Eu3+ host–dopant combination is the best-studied down-converting system with lower energy UV radiation because the emission energy transitions within Gd3+ can resonantly couple to the excited state of Eu3+ ions. Based on this established science, AGdF4:Eu3+ nanoparticles appear to be a very good choice for XLOT, as this material could provide an efficient means to down-convert high energy electrons generated by X-rays to visible or near-infrared (NIR) wavelengths. The efficiency of scintillators in bulk materials is well-documented,26,27 but a systematic comparison of the efficiency of optical emission by doped fluoride nanoparticles (as well as other doped metal oxide nanoparticles), and their sensitivity to surface states, is not available to the best of our knowledge.

Nanoparticles can be modified by adding coatings to their surfaces to improve the absorption of X-rays. Phosphor materials typically offer maximum densities in the range of 10 g/cm3.27 Metals, on the other hand, have densities of ∼20 g/cm3. Therefore, in order to improve the X-ray stopping power of the phosphor material, a core–shell structure consisting of a phosphor core and metal shell may offer some advantages. The addition of a gold shell to the phosphors can contribute to the biocompatibility to the nanoparticles, as well as potentially improve the efficiency of the X-ray luminescence. We previously developed a synthesis route for the addition of a gold shell to up-converting phosphors, which yields a significant increase in the efficiency of the up-conversion process.28 This core–shell material was chosen as a possibly interesting candidate for clinical applications of the XLOT technology and has been examined in the current study, along with bare phosphor particles.

Most of the efforts over many years in developing phosphors for scintillator applications have been devoted to examining bulk and single crystals. The use of these materials in a nanoparticle form stems from the need for in vitro and in vivo imaging methodologies. Currently, very little information pertaining to intrinsic and extrinsic factors influencing the X-ray excited luminescence is available for X-ray excitable nanophosphors that are less than 100 nm in size. Here, a systematic study of NaGdF4:Eu3+ nanoparticles has been undertaken with the purpose of developing a well controlled nanomaterial platform (in terms of uniformity, size, tunability, and surface modification) for X-ray excited optical imaging with a good understanding of the factors that control the luminescence. The comparison of X-ray excited luminescence of NaGdF4:Eu3+ with other reported materials of a similar size show that NaGdF4:Eu3+ nanoparticles exhibit the greatest X-ray excited luminescence. Therefore, in addition to their potential as an efficient magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agent and up-converting phosphor, this class of nanomaterial holds the great promise as a new XLOT imaging agent.

Experimental Section

Synthesis of NaGdF4-doped with Eu3+

Nanoparticles of NaGdF4-doped with Eu3+ and Ce3+ were synthesized by the citrate method.28 A transparent aqueous solution containing 4 mL of 0.2 M lanthanide chlorides (Sigma Aldrich, MO) and 8 mL of 0.2 M sodium citrate (Sigma Aldrich, MO) was heated to 90 °C. Sodium fluoride (16 mL of 1 M) (Fischer Scientific, PA) solution was added to the solution, upon which the solution turned whitish. The nanoparticles were heated for 2 h. The nanoparticles were centrifuged and washed twice before further measurements were carried out. As-synthesized particles were heated in a Teflon-lined autoclave (Cole-Parmer, IL) at 210 °C for 1 h to obtain hexagonal phase of the nanoparticles. The pH studies were carried out by suspending 6 mg, 2.5 mg, and 2 mg of the nanoparticles obtained from three different batches in 1 mL of phosphate buffer silane with pH values ranging from 2.5 to 7.2. pH buffers below 7.4 were prepared by adding small amounts of 10 mM solution of HCl was used and the pH monitored by ORION 5 STAR (Thermo Scientific, MA) pH meter.

Synthesis of BaYF5:Eu3+ in Hydrothermal Method

Water-soluble and polyethyll glycol (PEG)-coated BaGdF5:Eu3+ nanoparticles were synthesized following a reported one-pot hydrothermal method.29 Then, 0.90 mmol of GdCl3.6H2O and 0.10 mmol of EuCl3.6H2O were added to 20 mL ethylene glycol (EG). Then, 1 mmol BaCl2.2H20 was added to above solution and stirred for 30 min. PEG (1 g) (Mw = 2000) was added and sonicated (Branson 2510, Bransonic Ultrasonic Cleaner) the solution for 15 min. After that, 10 mL of EG containing 5.5 mmol NH4F was added to above mixture. The mixture solutions were stirred and sonicated for another 30 min and then transferred into a 50 mL stainless Teflon-lined autoclave and kept at 200 °C for 24 h. After that, the autoclave was allowed to cool down to room temperature. The reaction mixture was washed and centrifuged several times with ethanol and deionized (DI) water to remove other residual solvents and then suspended in DI water for further use.

Synthesis of BaYF5:Eu3+ by the Thermal Decomposition Method

Hydrophobic nanocrystals were synthesized via a thermal decomposition method.18 YCl3·6H2O (0.90 mml), 0.10 mmol of EuCl3·6H2O, and 1 mmol of barium acetylacetonate were dissolved in 15 mL oleic acid and 15 mL of 1-octadecene at 120 °C under vacuum for 2 h. The mixture was then cooled to room temperature, and a second solution containing 5.5 mmol of NHF4 in 10 mL methanol was added. The mixture was stirred for 30 min and the methanol was slowly removed at 70 °C. Once the methanol was removed the reaction mixture was raised to 310 °C and heated for 1 h. The solution was cooled to room temperature and washed with ethanol and oleate capped nanoparticles were then dispersed in chloroform. The hydrophobic nanoparticles were rendered water-dispersible by intercalating with PEG-mono oleate ligands (Sigma, Mn ∼860) using a method described elsewhere.30 The PEG-modified nanoparticles then were dispersed in DI water for further use.

Synthesis of Gd2O3:Eu3+

Gd2O3:Eu3+ nanoparticles were synthesized using an ultrasonic flame spray pyrolysis technique similar to the forced jet atomizer method reported by our group earlier.31 Briefly, 35.5 mM of Gd(NO3)3·6H2O and 6.3 mM of Eu(NO3)3·6H2O salts were dissolved in ethanol and used as the liquid precursor. The precursor was atomized at 50 mL/h flow using a tunable an ultrasonic spray nozzle (Sono-Tek Corporation, NY, U.S.A.) operating at 1.9 W with a nitrogen carrying gas (3 L/min) into a hydrogen (2 L/min)–air flame. The precursor droplets were pyrolyzed to form nanoparticles in the high temperature environment. Particles were collected on a 200 nm PTFE membrane filter; the collected powder was washed in Milli-Qultrapure (MQ, 18.3 MΩ-cm) water to remove any unreacted precursor from the nanoparticles. The nanoparticles were dispersed in DI water for further characterization.

Powder X-ray Diffraction

The phases of the calcined powders of coated and uncoated NPs were characterized by Sintag XDS 2000 fitted with a copper Kα source, operating at −45KV and 40 mA. Powdered samples were spread on a low background glass slide and scanned in a 2θ–2θ geometry from 10 to 60 degrees (See Supporting Information).

Transmission Electron Microscopy

The nanoparticles were deposited on a Formvar/carbon coated copper grids from a water solution and dried before taking the bright field transmission electron micrographs from Phillips CM-12 operating at 100–120 KeV and 10–15 μA.

Dynamic Light Scattering Experiments

A 0.1% solution of these core–shell nanoparticles was prepared in water. The dynamic light scattering experiments were performed with the Brookhaven ZetaPlus instrument. A single run was of 2 min duration and the data was averaged over five runs for each sample (See Supporting Information).

Absorbance

The optical absorbance of nanoparticle solutions was obtained from a Spectramax M2 (Molecular Devices, CA) in a quartz cuvette. The concentration of the nanoparticle solution was 1.5 mg/mL.

UV-Excited Photoluminescence

A UV lamp (Spectroline, Fischer Scientific, PA) with a long (365 nm) and short wavelength (254 nm) source was used for UV-excited photoluminescence from the nanoparticles. The emission was directed into an Acton SpectraPro 300i series spectrometer, fitted with a PI-MAX camera (Princeton Instruments, NJ). The spectra were collected by Win32 software from Princeton Instruments. The concentration of the solution was 3 mg/mL. The intensity ratios were based on peak area analysis obtained by multicurve Gaussian profile fitting using Igor Pro 6.3 (Wavemetrics Inc., Oregon) software.

X-ray Luminescence

X-ray luminescence was measured using an X-ray tube (SB80250, Oxford Instruments, Scott’s Valley, CA), controlled with commercial software developed by Source-ray, Inc. (Bohemia, NY). The X-ray tube generates X-ray photons with an energy up to 80 kVp and a maximum X-ray tube current of 0.25 mA. In this study, the X-ray tube was set at 75 kVp and 0.24 mA. An EMCCD camera (C91003, Hamamatsu) was used to measure the X-ray activated optical luminescence. The EMCCD camera was set at maximum EM gain and analog gain with photon mode 1. The EMCCD camera was cooled to −92 °C (see Supporting Information for a schematic diagram of the imaging and spectroscopic system). X-ray excited luminescence spectra were obtained with a spectrograph (Imspector V10E, Specim, Oulu, Finland).

A suspension of nanoparticles in a polymer cuvette was used for evaluation of X-ray excited luminescence intensity and spectra. The concentration of the nanoparticle solution was between 3 to 10 mg/mL. In the case of gold-coated nanoparticles, the additional mass of the nanoparticles was taken into account with the knowledge that the molar mass of the phosphor was roughly 3 orders of magnitude greater than gold; that is, the addition of the gold coating did not affect the mass of the particles. Comparisons of the different types of particles were therefore performed on the basis of a constant mass concentration. The intensity ratios were based on peak area analysis obtained by multicurve fitting using Igor Pro 6.3 (Wavemetrics Inc., Oregon) software.

Cytotoxicity Study

Primary Human Aortic Endothelial Cells (HAEC) were purchased from Lifeline Cell Technologies (FC-0014) and cultured in Vasculife VEGF cell culture medium containing 2% FBS, 10 mM l-glutamine, 0.75 U/ml heparin sulfate, 1.0 μg/mL hydrocortisone hemisuccinate, 50 μg/mL ascorbic acid, 15 ng/mL rh IGF-1, 5 ng/mL rh FGF Basic, and 5 ng/mL rh EGF at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. Calcein and propidium iodide assays (Invitrogen Part #C3100MP and P3566, respectively) were performed on the cells. P5 cells were plated on collagen-coated 50 mm glass bottom culture dishes (MatTek Part # P50G-1.5-39-F), grown to ∼95% confluency, and then incubated for 20 h with NaGdF4:Eu or NaGdF4:Eu@Au nanoparticles suspended in VEGF cell culture medium at 50 μg/mL and 250 μg/mL. The culture medium was then gently aspirated out, replaced with 3 μM Calcein AM in DPBS and incubated for 15 min, the last 5 of which propidium iodide nucleic acid stain was added to a final concentration of 4 μM. The culture dishes were placed on an inverted Olympus IX81 Confocal Microscope and imaged using Fluoview 1000. Image J analysis was performed on the images by setting a threshold to convert them to a black and white format. Particle analysis was used to count the number of apparent particles and the total surface area covered by particles. Particles smaller than 200 × 200 pixels were excluded.

X-ray Luminescence-Animal Study

A stock solution of the particles at 30 mg/mL concentration was prepared. Each sample was sonicated and 25 μL of it was mixed with 25 μL matrigel in a cuvette cooled in an ice tank to produce a final particle concentration of 15 mg/mL. For the control case, 25 μL of saline was mixed with 25 μL of matrigel. A syringe, cooled in an ice tank, was used to inject the 50 μL nanoparticle-matrigel solution under the mouse skin. The mouse was euthanized just prior to injection. The mouse was placed in a light-tight box and irradiated by X-rays (75 kVp, 0.24 mA, 331 mm X-ray tube to mouse distance, 30 s exposure). The X-ray excited luminescence was imaged by the EMCCD camera (using a mirror to reduce direct detection of scattered X-rays in the EMCCD camera, 30 s exposure) and overlaid on a white light photograph of the mouse.

Results and Discussion

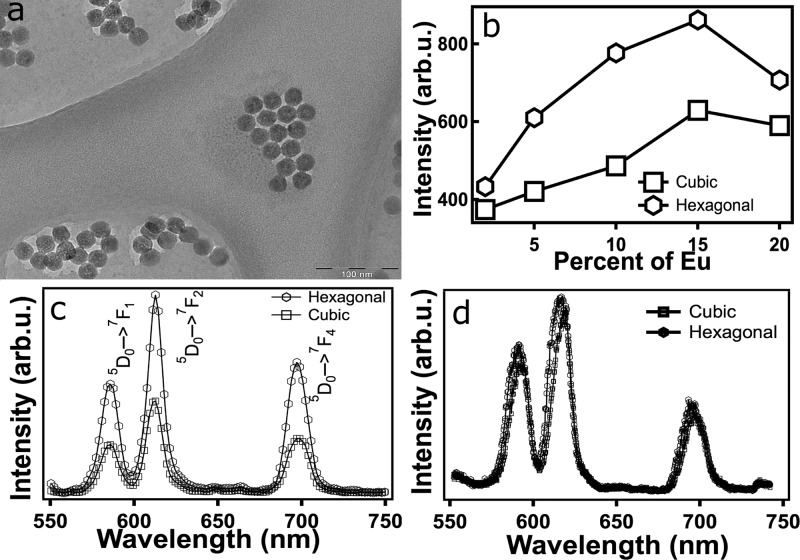

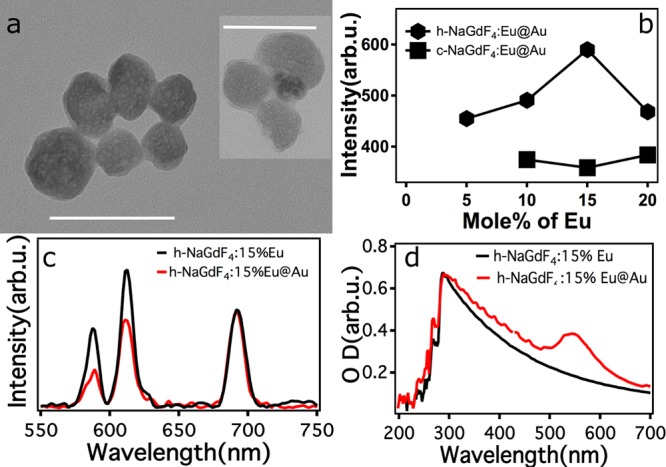

The typical particle size of the hexagonal NaGdF4:Eu3+ nanoparticles was approximately 30 nm (Figure 1a). In Figure 1b, the integrated intensities of the three major 5D0→7FJ emissions of Eu3+ are plotted against the molar percentage of the Eu3+ in the nanoparticles. The intensities increased with Eu3+ concentration and reached a maximum at about 15 molar percent concentration of Eu3+ in hexagonal NaGdF4 nanoparticles. A similar concentration trend was observed for cubic NaGdF4 nanoparticles, albeit with half the intensities. Spectra of the emissions under X-ray excitation are shown in Figure 1c. The X-ray luminescence optical spectrum was obtained from a solution of nanoparticles with a concentration of 3 mg/mL. As XLOT requires bright luminescent particles, optimization of the dopant concentration is critical for efficient imaging. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no extant reports with respect to the optimized doping concentration of Eu3+ for X-ray luminescence. A comparison of X-ray activated optical luminescence spectra from hexagonal and cubic NaGdF4:Eu3+ reveals that the emission peaks are identical in the 300–1100 nm region (Figure 1c). There was no change in the ratio of intensities of the emission peaks that arise from the magnetic dipole and electric dipole transitions, 5D0→7F1 (587 nm) and 5D0→7F2 (612 nm), respectively. The ratio of 5D0→7F2/5D0→7F1 was 1.6 and 1.7 for cubic and hexagonal crystals. This indicates the X-ray luminescence was from a highly asymmetric Eu3+ for both the structures under X-ray excitation.32

Figure 1.

(a) TEM micrograph of hexagonal NaGdF4:15%Eu3+ nanoparticles. (b) Eu concentration dependence of X-ray luminescence of NaGdF4:Eu3+ nanoparticles. Intensities correspond to integrated intensities of all the 5D0→7FJ transitions observed. (c) X-ray luminescence spectra of cubic and hexagonal NaGdF4:15%Eu3+ nanoparticles. (d) Photoluminescence spectra of cubic and hexagonal NaGdF4:15%Eu3+. Nanoparticle concentration in all the luminescence measurements was 3 mg/mL.

The trend of the X-ray luminescence from the two crystal phases resembles that of up-converted luminescence observed from the same host matrix following NIR excitation (i.e., hexagonal crystal emits stronger than the cubic crystal).33 However, down-conversion photoluminescence of nanoparticles under near UV excitation (365 nm) showed no appreciable difference in the luminescence intensities from two different phases (Figure 1d). A comparison to the X-ray excited luminescence shows that the crystal symmetry surrounding the Eu3+ ion under X-ray excitation was predominantly from a low symmetry site. The 5D0→7F2/5D0→7F1 ratio indicates that the local crystal structure surrounding the doped Eu3+ ions remains the same in the cubic and the hexagonal NaGdF4 phases. Since the UV-excited luminescence intensity for 5D0→7F2 and 5D0→7F1 remains the same for both structures, albeit smaller at 1.3, it can be deduced that the degree of randomness associated with cations (Na+, Gd3+, and Eu3+) was similar within these crystal structures. The order–disorder of the cations in ALnF4 structures are known to be associated with the kinetics of heating.34 Since the hexagonal NaGdF4:Eu3+ NPs were synthesized by a rapid hydrothermal method, a high degree of randomness in the cation distribution is to be expected.

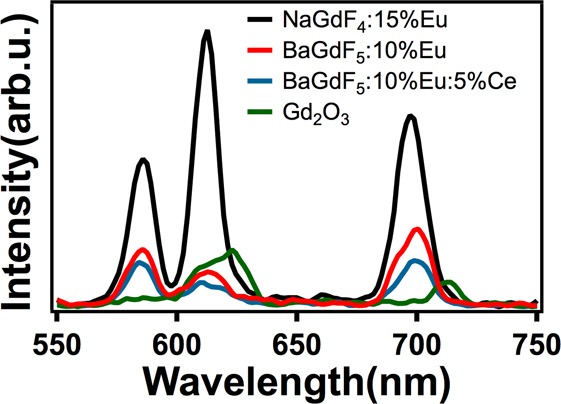

In order to further understand the effect of crystal structure and compare the luminescence efficiencies, we compared the emission intensities of NaGdF4:Eu3+ with other types of X-ray luminescent NPs reported in the literature (i.e., BaYF5:Eu,18 Gd2O3:Eu7,35). To make a systematic comparison, similar sizes of the NPs were studied (i.e., in the range of 20–40 nm) with the same mass concentration. The concentration of the Eu3+ dopant was similar to the reported methods.18 BaYF5:10%Eu3+ was synthesized both by the previously reported thermal decomposition method18 and a hydrothermal method29 (Figure S1 Supporting Information). A high temperature monoclinic phase of Gd2O3:18%Eu3+ was synthesized with a flame spray pyrolysis developed by our group.31 The luminescence intensities of BaYF5:Eu3+ were lower by more than a factor of 2 when compared with hexagonal NaGdF4:Eu3+ (Figure 2). There was no significant improvement in the luminescence from BaYF5:10%Eu3+ upon doping with 5–20% Ce3+ sensitizer ions. In addition, flame-synthesized Gd2O3:18%Eu3+ NPs that showed the brightest photoluminescence under near UV excitation also had low X-ray luminescence (Figure 2). Therefore, the results suggest that the luminescence obtained with near UV excitation may not be a good guide to the efficiency of luminescence that arises from X-ray excitation.

Figure 2.

Comparison of X-ray excited luminescence intensities from Eu doped into different nanoparticle matrices. All particles were measured at a concentration of 10 mg/mL.

The X-ray luminescence from Eu3+ doped into hexagonal NaGdF4 NPs was the brightest among the NPs that we studied. Our measurements indicated that the cubic crystal structure resulted in lower X-ray luminescence intensities in comparison to hexagonal structure, regardless of the host matrix and synthesis protocol. When cubic NaGdF4:15%Eu3+ was compared with BaYF5:10%Eu3+ and BaYF5:10%Eu3+:5%Ce, the X-ray luminescent intensity of the NaGdF4:15%Eu3+ was the highest. In contrast to NaGdF4:15%Eu3+ nanoparticles, X-ray luminescence from BaYF5:10%Eu3+ and BaYF5:10%Eu3+:5%Ce appeared to be from Eu3+ in a more symmetric environment, as the ratio of 5D0→7F2/5D0→7F1 intensities were <1 (0.8), and a higher intensity of the 5D0→7F4 transition was observed.

X-ray luminescence from phosphors involves formation of (a) excitons (electron–hole pairs); (b) their thermalization; (c) transfer of exciton energy to the luminescent center; (d) photon emission following the relaxation of the excited electron on the luminescent center; (e) heat generation. The X-ray excitation leads to the formation of electron–hole pairs with energy greater than or equal to the band gap of the material. The relaxation process proceeds either through a radiative pathway or by heat dissipation.36 X-ray excited luminescence is influenced by the activator ion,17,37 interstitial fluorides ions,38 and the dynamics of the electron–hole pairs in the presence of such impurity centers.39,40 The UV excited luminescence of cubic and hexagonal NaGdF4:Eu3+ suggests that the efficiencies of the phosphors are similar. If the phonon density of state was an important factor that affected the emission, higher emission intensities from hexagonal nanoparticles would be expected.41

It has been suggested that Ln3+ ions provide an effective mechanism for radiative emission by excitons generated by X-ray irradiation in a fluoride matrix.37 To constitute an efficient pathway of emission through rare-earth ions, these excitons must be stable and STE emission should be absent.37 The presence of Ln3+ ions in a fluoride matrix fulfills these two criteria.17 For ALnF4 structures, cross-luminescence from the valence band to the core band is not a major radiative pathway; the results suggest that visible luminescence is possible through migration of excitons to the doped ion.42 Therefore, the radiative decay of the conduction band electron through the activator ion in NaGdF4 can be expected. The direct relaxation of the STE from the conduction band to the valence band is suppressed by the broadening of the valence band that is formed by the 2p electrons of the fluorine,38 transferring the holes to the Eu3+ ions that trap the excitons sequentially. This is followed by a radiative f–f transition that is promoted by the broadening of the valence band in hexagonal NaGdF4—broadening of the valence band is expected in hexagonal NaGdF4 in comparison to cubic NaGdF4 as there are two different sites of fluorine in the unit-cell.34 It must be noted that the cubic NaGdF4 has eight coordinated holes that trap electrons and contribute to nonradiative quenching23 through reduced migration of the exciton energy to the Eu3+ ion. In the case of BaYF5 nanoparticles, the nonradiative quenching of the excitons by LnF3 in BaF2 solids is well-documented.39,43

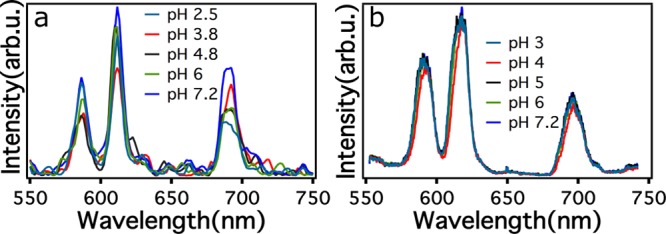

Because X-ray luminescence was sensitive to the impurity state, the nature of the nanoparticle surface can also be expected to influence the X-ray luminescence. The pH of the suspending medium can influence surface states on particles and can possibly influence the X-ray luminescence. It is well-known from the quantum dot literature that the local environment affects the exciton emission and can be controlled by introducing quenching centers such as thiols44 that diminish emission. The NaGdF4 particles studied in this work were prepared by a citrate method giving the particles a surface coating of citrate ions. Protonation/deprotonation of the carboxylic acids on the citric acid that occurs between pH 2–7 with pKa values of 3.13, 4.76, and 6.445 changes the nature of the surface groups, influencing surface defects. We observed that the X-ray luminescence of hexagonal NaGdF4:15%Eu3+ decreased with a corresponding decrease in the pH of the solution (Figure 3) with the intensities of the 5D0→7FJ transitions of Eu3+ showing particular sensitivity to the pH. The modulation of the X-ray luminescence with changing pH was consistent—regardless of the particle concentration (see Supporting Information Figure S2). Furthermore, the 5D0→7F2/5D0→7F1 ratio remained unchanged (approximately 1.6–1.7) for all the pH values that were studied. On the other hand, UV-excited photoluminescence (excitation at 254 and at 365 nm) did not show a significant change due to variation of the pH. Hence, in combination, the UV and X-ray data rule out the possibility that the effect could be due to the crystal field changes around the Eu3+ ion. The UV-excited photoluminescence results suggest that the excited 4f electrons within the lanthanide are less sensitive to the environment. Thus, the results strongly suggest that the excitons generated by X-ray excitation are highly sensitive to adsorbed surface groups, defects, and defect-like features (such as broadening of the valence band) in NaGdF4 nanoparticles. The pH sensitivity of the emission following X-ray excitation could, in principle, be used an indicator of the local intracellular environment surrounding the particles, for example, distinguishing between the contrast agent that is present in lysosomes and cytoplasm.

Figure 3.

Effect of pH on luminescence of hexagonal NaGdF4:15%Eu3+ nanoparticles. (a) Under X-ray excitation and (b) UV-excitation (365 nm excitation).

Recently, Chen et al.12 demonstrated the monitoring of pH through X-ray luminescence based on pH-induced changes in the concentration of a material that has its optical absorption overlapping the luminescence of Gd2O3S:Tb core–shell nanoparticles. In this case, the optically active material was released in a controlled manner following changes in the pH of the solution, increasing the X-ray luminescence. On the other hand, our results showed that the pH of the solution could directly affect the X-ray excited luminescence (and not the UV excited luminescence), presumably through alteration of the electron–hole stability within the nanoparticle.

Gold nanoparticles offer high contrast in X-ray tomography.46,47 Gold nanoparticles conjugated to near-infrared fluorescent dyes have been shown to be excellent markers for dual-mode imaging that combines X-ray computed tomography and fluorescence. Metals may introduce plasmonic effects. It is known that the emission from lanthanides is affected not just by the lanthanide ion crystal symmetry or size,33,48,49 surface quenchers,50,51 enhanced energy migration,52 and sensitization53 but also by plasmonic perturbations that can be produced by metals such as silver and gold.28,54,55 In addition to possible plasmonic enhancement of emission, gold can also provide desirable biocompatibility. Given the high density of gold (19.3 g/cm3), we hypothesized that the use of an inorganic scintillator core with a metal shell to increase the stopping power of X-rays, in combination with the possible plasmonic enhancement and biocompatibility, should make a phosphor with a gold shell a good candidate for in vivo imaging. However, little is known about of the impact of gold on the X-ray luminescence from lanthanide ions. Previously, we have demonstrated a facile one-pot technique to coat gold on NaLnF4 nanoparticles.28 In this work, we employed the same protocol to coat the gold on NaGdF4 nanoparticles. Figure 4a shows a sample transmission electron microscopy image of the as-prepared gold-coated nanoparticles. In order to understand the effect of gold coating on the X-ray excited luminescence, various doping concentrations of Eu3+ in both hexagonal and cubic NaGdF4 nanoparticles that were coated with gold were studied. The concentration of the particles in suspension was held constant in all cases to within a very small tolerance.

Figure 4.

(a) TEM micrographs of as-synthesized NaGdF4:15%Eu3+@Au. (b) X-ray excited luminescence of gold coated hexagonal and cubic NaGdF4:Eu3+ for different Eu concentrations (3 mg/mL). (c) Comparison of X-ray excited luminescence spectra of gold-coated and uncoated hexagonal NaGdF4:15%Eu3+ (d) Absorbance spectrum of gold-coated and uncoated hexagonal NaGdF4:15%Eu3+ (1.5 mg/mL). Scale bars correspond to 100 nm.

The cubic NaGdF4:Eu3+ did not exhibit any significant dependence on the concentration of Eu3+ in the gold-coated particles (Figure 4b). For the hexagonal NaGdF4:Eu3+, the dependence of X-ray luminescence on Eu3+ concentration was similar to that of uncoated nanoparticles. A Eu3+ doping concentration of 15% showed the highest luminescent intensity. However, in contrast to the up-converting nanoparticles, where it is known that a gold shell can enhance the up-converted luminescence,28 the ∼5–8 nm thick gold shell (Figure 4a) in this case was found to reduce the X-ray excited luminescence. The total luminescence from NaGdF4:15%Eu3+@Au was 75% of the uncoated material, with 5D0→7F1 and 5D0→7F2 transitions being 51% and 73% of the uncoated nanoparticle. Surprisingly, the 5D0→7F4 emission at around 700 nm wavelength in NaGdF4:15%Eu3+@Au was fortuitously unaffected (given its relatively low absorbance in tissues) (Figure 4c).

The trend in the X-ray luminescence data can be explained by the taking into consideration the plasmonic absorption of the gold. Figure 4d shows the absorbance spectra of hexagonal NaGdF4:15%Eu3+ and NaGdF4:15%Eu3+@Au. The gold shell had a plasmonic peak around 530 nm. The plasmonic absorption decreased in the 550–700 nm region with increasing wavelength and the observed luminescence intensities from NaGdF4:15%Eu3+@Au correlated with the plasmonic reabsorption. It should be noted that the experiments were performed in a cuvette with a defined width of 1 cm. It is therefore expected that the plasmonic reabsorption occurred not only from the gold coated on a given nanoparticle but also from the surrounding gold-coated nanoparticles as an inner filter effect.

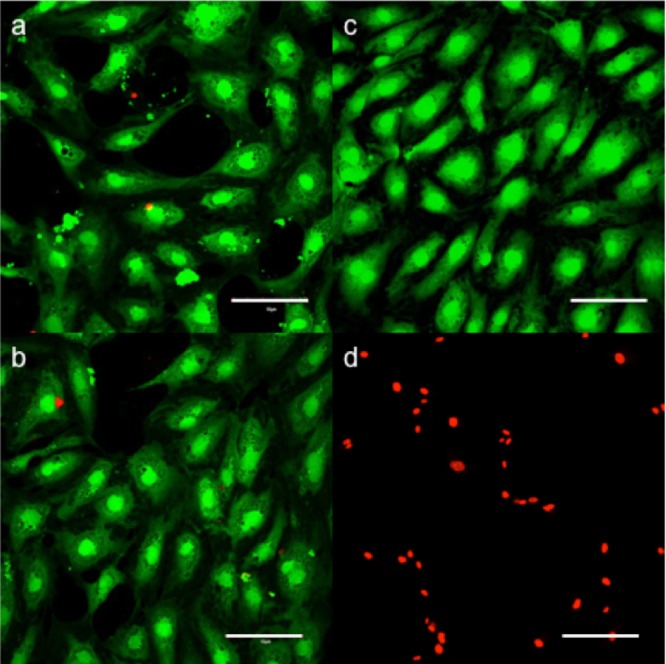

To further understand the possible applicability of gold-coated and uncoated NaGdF4:Eu3+ nanoparticles for in vitro imaging with human cells, cell viability studies were conducted. Primary human aortic endothelial cells were chosen as typical of endothelial cells that might be exposed to nanoparticles upon injection, as they line the inside of the blood vessels. Calcein AM is a nonfluorescent membrane permeant dye that is hydrolyzed by intracellular acetoxylmethyl ester to a fluorescent Calcein conjugate, which then accumulates inside the cell and can be used to indicate membrane integrity and cellular viability (false colored green). Propidium iodide is a membrane impermeant nucleic acid stain that binds the DNA of dead cells and is normally excluded from viable cells (false colored red). A 20 h in vitro comparison of NaGdF4:15%Eu3+ and NaGdF4:15%Eu3+@Au showed that at the 50 μg/mL concentration there were no visible toxicity or viability changes associated with nanoparticle exposure to the cells, as can be seen by the minimal increase in propidium iodide signal and almost constant cell surface coverage observable through fluorescent Calcein (See Supporting Information Figure S3). At 250 μg/mL, it was found that the viability decreased for both gold-coated and uncoated particles (Figure 5a)—the gold-coated particles elicited less response (Figure 5b). Image J analysis was performed on previously shown Calcein images, in which total cell count and % surface area coverage were used as a means of quantifying cellular viability (See Supporting Information Figure S4). Using either cell count or % surface area, an analysis showed that gold-coated particles had a slightly less toxic effect on the cells compared to their corresponding noncapped particles. Human aortic endothelial cells exposed to 250 μg/mL NaGdF4:15%Eu3+ had 34 viable cells covering 14.9% of the surface area (a) and NaGdF4:15%Eu3+ @Au had 41 viable cells covering 16.8% of the surface area (b) and the Calcein control had 49 viable cells covering 26.6% of the surface area (c). While the Calcein signal decreased, the propidium iodide signal did not increase proportionally, due to the inherently adherent nature of the cells. Following death, the cells ball-up and eventually detach from the surface, becoming freely suspended in the medium and thus out of the plane of imaging. As a result, the propidium iodide stain is not as effective a measure of viability as Calcein; we drew our conclusions from the Calcein images.

Figure 5.

Fluorescent microscope images of human endothelial cells exposed to (a) 250 μg/mL hexagonal NaGdF4:15%Eu3+; (b) gold-coated hexagonal NaGdF4:15%Eu3+. (c) Calcein/PI control and (d) Calcein/PI Triton control are shown for comparison. The scale bars are 10 μm.

It is not presumed that this assay is conclusive with regard to the relative cytotoxicity of bare vs gold-coated particles. However, for the purpose of this study, this experiment serves as a proof of concept that the addition of a gold coating has the potential to decrease cytotoxicity. A more in-depth cytotoxicity study will include additional types of cytotoxicity assays such as MTT, LDH, and MTS.

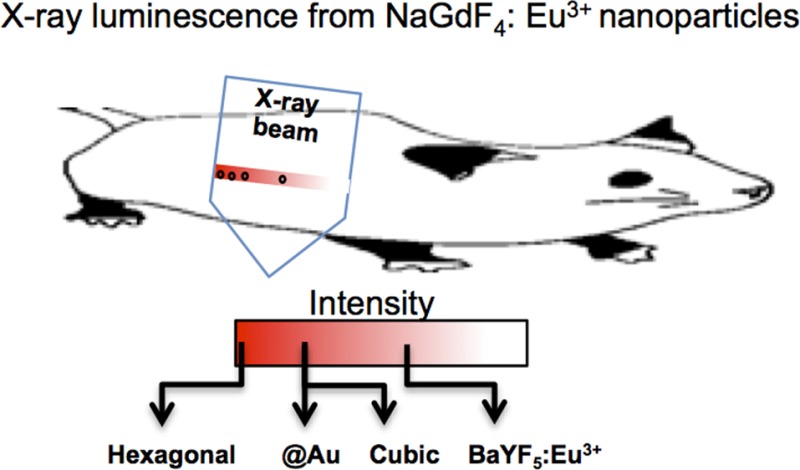

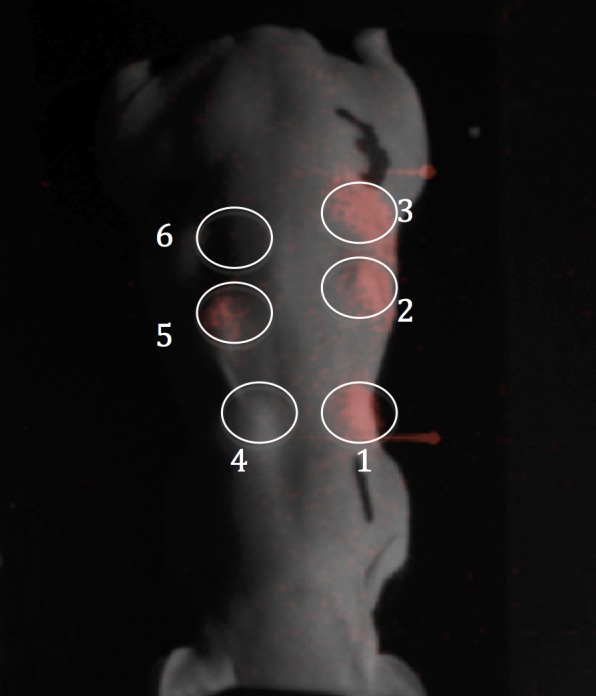

The suitability of NaGdF4:Eu3+ particles in X-ray luminescence optical tomography was examined using a mouse model (Figure 6). The luminescence from the NaGdF4:15% Eu3+ nanoparticles was bright in comparison to the BaYF5:10%Eu3+ that has been used in the past for in vivo X-ray luminescence.18 The gold-coated phosphor also showed excellent brightness due to reduced interparticle absorption. Our results show that hexagonal NaGdF4:Eu3+ nanoparticles are excellent candidates for applications that utilize X-ray activated luminescence and could have a future role for in vivo molecular imaging studies.

Figure 6.

X-ray luminescence imaging of (1) hexagonal NaGdF4:15%Eu3+; (2) NaGdF4:15%Eu3+@Au; (3) hexagonal NaGdF4:15%Eu3+; (4) BaYF5:10%Eu3+:5%Ce3+; (5) BaYF5:10%Eu3+; (6) saline control with no particles. The luminescence image was overlaid on a white light image of the mouse. The final concentration of the nanoparticle solution in the matrigel solution was 15 mg/mL. The exposure time for X-ray luminescence imaging was 30 s.

Conclusions

X-ray excited luminescence and photoluminescence of hexagonal and cubic NaGdF4:Eu3+ nanophosphors in aqueous medium were studied. X-ray excited luminescence from the hexagonal phase was twice as strong as that from the cubic phase. Surprisingly, the emission intensity was found to be pH dependent. The UV-excited photoluminescence intensities, on the other hand, from these two phases were identical, indicating that the radiative emission of electron–hole pairs generated by X-ray excitation is influenced by the crystal structure and the local environment. Coating of the particles with a gold shell affected the overall emission of light but the most important NIR line near 700 nm was fortunately not affected, preserving the usefulness of the gold-coated particles for XLOT while improving their biocompatibility. Hexagonal NaGdF4:Eu3+ nanoparticles with an optimal doping concentration of lanthanide ions are an excellent choice for X-ray luminescence optical imaging.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by Award Number P42ES004699 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and by grant R21 EB013828 from the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, or the National Institutes of Health. We acknowledge the support of the W. M. Keck Foundation for a research grant in science and engineering.

Supporting Information Available

Additional figures as mentioned in the text, characterization (X-ray, DLS, TEM), luminescence, absorbance spectra and schematic of experiments. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Author Contributions

∥ L.S. and G.K.D. contributed equally.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Yang Y.; Shao Q.; Deng R.; Wang C.; Teng X.; Cheng K.; Cheng Z.; Huang L.; Liu Z.; Liu X.; Xing B. In vitro and in vivo uncaging and bioluminescence imaging by using photocaged upconversion nanoparticles. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51133125–3129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F.; Banerjee D.; Liu Y.; Chen X.; Liu X. Upconversion nanoparticles in biological labeling, imaging, and therapy. Analyst 2010, 13581839–1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayakumar M. K. G.; Idris N. M.; Zhang Y. Remote activation of biomolecules in deep tissues using near-infrared-to-UV upconversion nanotransducers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012, 10.1073/pnas.1114551109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyk M.; Kumar R.; Ohulchanskyy T. Y.; Bergey E. J.; Prasad P. N. High contrast in vitro and in vivo photoluminescence bioimaging using near infrared to near infrared up-conversion in Tm3+ and Yb3+ doped fluoride nanophosphors. Nano Lett. 2008, 8113834–3838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilderbrand S. A.; Shao F.; Salthouse C.; Mahmood U.; Weissleder R. Upconverting luminescent nanomaterials: Application to in vivo bioimaging. Chem. Commun. 2009, 28, 4188–4190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H.; Rogalski M. M.; Anker J. N. Advances in functional X-ray imaging techniques and contrast agents. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 143913469–13486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H.; Colvin D. C.; Qi B.; Moore T.; He J.; Mefford O. T.; Alexis F.; Gore J. C.; Anker J. N. Magnetic and optical properties of multifunctional core–shell radioluminescence nanoparticles. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 222512802–12809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H.; Longfield D. E.; Varahagiri V. S.; Nguyen K. T.; Patrick A. L.; Qian H.; VanDerveer D. G.; Anker J. N. Optical imaging in tissue with X-ray excited luminescent sensors. Analyst 2011, 136173438–3445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton I. N.; Ayres J. A.; Therien M. J. Dual energy converting nano-phosphors: Upconversion luminescence and X-ray excited scintillation from a single composition of lanthanide-doped yttrium oxide. Dalton Trans. 2012, 413811576–11578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C. Q.; Di K.; Bec J.; Cherry S. R. X-ray luminescence optical tomography imaging: Experimental studies. Opt. Lett. 2013, 38132339–2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter C. M.; Sun C.; Pratx G.; Rao R.; Xing L. Hybrid X-ray/optical luminescence imaging: Characterization of experimental conditions. Med. Phys. 2010, 3784011–4018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H.; Moore T.; Qi B.; Colvin D. C.; Jelen E. K.; Hitchcock D. A.; He J.; Mefford O. T.; Gore J. C.; Alexis F.; Anker J. N. Monitoring pH-Triggered drug release from radioluminescent nanocapsules with X-ray excited optical luminescence. ACS Nano 2013, 721178–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratx G.; Carpenter C. M.; Sun C.; Rao R. P.; Xing L. Tomographic molecular imaging of X-ray-excitable nanoparticles. Opt. Lett. 2010, 35203345–3347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilchenko V. G.; Kobayashi M. In Multicomponent Crystals based on Heavy Metal Fluorides for Radiation Detectors; Sobolev B. P., Ed.; Institute d’Estudis Catalans: Barcelona, Spain, 1994; Ch. 3, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Sobolev B. P.; Krivandina E. A.; Derenzo S. E.; Moses W. W.; West A. C. Suppression of BaF2 slow component of X-ray luminescence in non-stoichiometric Ba0.9R0.1F2.1 crystals (R = rare earth element). MRS Online Proc. Library 1994, 348, 277–283. [Google Scholar]

- Pack D. W.; Manthey W. J.; McClure D. S. Cê3+:Nâ+ pairs in CaF2 and SrF2: Absorption and laser-excitation spectroscopy, and the observation of hole burning. Phys. Rev. B 1989, 40149930–9944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojtowicz A. J. Rare-earth-activated wide bandgap materials for scintillators. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A 2002, 4861–2201–207. [Google Scholar]

- Sun C.; Pratx G.; Carpenter C. M.; Liu H.; Cheng Z.; Gambhir S. S.; Xing L. Synthesis and radioluminescence of PEGylated Eu3+-doped nanophosphors as bioimaging probes. Adv. Mater. 2011, 2324H195–H199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guggenheim H. J.; Johnson L. F. New fluoride compounds for efficient infrared-to-visible conversion. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1969, 15251–52. [Google Scholar]

- Sommerdijk J. L. On the excitation mechanisms of the infrared-excited visible luminescence in Yb3+, Er3+-doped fluorides. J. Lumin. 1971, 44441–449. [Google Scholar]

- Auzel F. Upconversion and anti-stokes processes with f and d ions in solids. Chem. Rev. 2003, 1041139–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegh R. T.; Donker H.; Oskam K. D.; Meijerink A. Visible quantum cutting in LiGdF4:Eu3+ through downconversion. Science 1999, 2835402663–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoma R. E.; Insley H.; Hebert G. M. The sodium fluoride–lanthanide trifluoride systems. Inorg. Chem. 1966, 571222–1229. [Google Scholar]

- Wegh R. T.; Donker H.; Oskam K. D.; Meijerink A. Visible quantum cutting in Eu3+-doped gadolinium fluorides via downconversion. J. Lumin. 1999, 82293–104. [Google Scholar]

- Ye S.; Zhu B.; Chen J.; Luo J.; Qiu J. R. Infrared quantum cutting in Tb3+,Yb3+ codoped transparent glass ceramics containing CaF2 nanocrystals. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008, 9214141112–3. [Google Scholar]

- Derenzo S. E.; Weber M. J.; Bourret-Courchesne E.; Klintenberg M. K. The quest for the ideal inorganic scintillator. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A 2003, 5051–2111–117. [Google Scholar]

- Weber M. J. Inorganic scintillators: Today and tomorrow. J. Lumin. 2002, 1001–435–45. [Google Scholar]

- Sudheendra L.; Ortalan V.; Dey S.; Browning N. D.; Kennedy I. M. Plasmonic enhanced emissions from cubic NaYF4:Yb:Er/Tm nanophosphors. Chem. Mater. 2011, 23112987–2993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng S.; Tsang M.-K.; Chan C.-F.; Wong K.-L.; Hao J. PEG modified BaGdF5:Yb/Er nanoprobes for multi-modal upconversion fluorescent, in vivo X-ray computed tomography and biomagnetic imaging. Biomaterials 2012, 33369232–9238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das G. K.; Johnson N. J. J.; Cramen J.; Blasiak B.; Latta P.; Tomanek B.; van Veggel F. C. J. M. NaDyF4 nanoparticles as T2 contrast agents for ultrahigh field magnetic resonance imaging. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2012, 34524–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abid A. D.; Anderson D. S.; Das G. K.; Van Winkle L. S.; Kennedy I. M. Novel lanthanide-labeled metal oxide nanoparticles improve the measurement of in vivo clearance and translocation. Particle Fibre Toxicol. 2013, 1011–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorller-Walrand C.; Binnemans K.. Rationalization of crystal-field parametrization. In Handbook on the Physics and Chemistry of Rare Earths; Gschneidner K. A. Jr.; Eyring L., Eds.; North-Holland: Amsterdam, 1996; Vol. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer J.-C.; van Veggel F. C. J. M. Absolute quantum yield measurements of colloidal NaYF4:Er3+,Yb3+ upconverting nanoparticles. Nanoscale 2010, 281417–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns J. H. Crystal structure of hexagonal sodium neodymium fluoride and related compounds. Inorg. Chem. 1965, 46881–886. [Google Scholar]

- Paik T.; Gordon T. R.; Prantner A. M.; Yun H.; Murray C. B. Designing tripodal and triangular gadolinium oxide nanoplates and self-assembled nanofibrils as potential multimodal bioimaging probes. ACS Nano 2013, 732850–2859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y.; Vasil’ev A. N.; Mikhailin V. V. Theory of X-ray photoacoustic spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. A: Mater. Sci. Process. 1995, 603333–341. [Google Scholar]

- Wojtowicz A. J.; Glodo J.; Wisniewski D.; Lempicki A. Scintillation mechanism in RE-activated fluorides. J. Lumin. 1997, 72–740731–733. [Google Scholar]

- Nepomnyashchikh A. I.; Radzhabov E. A.; Egranov A. V.; Ivashechkin V. F. Luminescence of BaF2–LaF3. Radiat. Meas. 2001, 335759–762. [Google Scholar]

- Radzhabov E.; Istomin A.; Nepomnyashikh A.; Egranov A.; Ivashechkin V. Exciton interaction with impurity in barium fluoride crystals. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A 2005, 5371–271–75. [Google Scholar]

- Weber M. J.; Derenzo S. E.; Moses W. W. Measurements of ultrafast scintillation rise times: Evidence of energy transfer mechanisms. J. Lumin. 2000, 87–890830–832. [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer H.; Ptacek P.; Eickmeier H.; Haase M. Synthesis of hexagonal Yb3+,Er3+-doped NaYF4 nanocrystals at low temperature. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2009, 19193091–3097. [Google Scholar]

- Dorenbos P.; Visser R.; Andriessen J.; van Eijk C. W. E.; Valbis J.; Khaidukov N. M. Scintillation properties of possible cross-luminescence materials. Nucl. Tracks Radiat. Meas. 1993, 211101–103. [Google Scholar]

- Visser R.; Dorenbos P.; Eijk C. W. E. v.; Hartog H. W. d. Energy transfer processes observed in the scintillation decay of BaF2:La. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 1992, 4458801. [Google Scholar]

- Wuister S. F.; Donega C. D.; Meijerink A. Influence of thiol capping on the exciton luminescence and decay kinetics of CdTe and CdSe quantum. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 1084517393–17397. [Google Scholar]

- Martell A. E.; Smith R. M.. Critical Stability Constants; Plenum Press: New York, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.; Chen W.; Wang S.; Joly A. G.; Westcott S.; Woo B. K. X-ray luminescence of LaF3:Tb3+ and LaF3:Ce3+,Tb3+ water-soluble nanoparticles. J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 1036063105–7. [Google Scholar]

- Chen W.; Westcott S. L.; Wang S.; Liu Y. Dose dependent X-ray luminescence in MgF2:Eu2+, Mn2+ phosphors. J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 10311113103–5. [Google Scholar]

- Sommerdijk J. L.; Wanmaker W. L.; Verriet J. G. Influence of host lattice on the infrared-excited visible luminescence in Yb3+, Er3+-doped oxides. J. Lumin. 1972, 54297–307. [Google Scholar]

- Krämer K. W.; Biner D.; Frei G.; Güdel H. U.; Hehlen M. P.; Lüthi S. R. Hexagonal sodium yttrium fluoride based green and blue emitting upconversion phosphors. Chem. Mater. 2004, 1671244–1251. [Google Scholar]

- Yi G.-S.; Chow G.-M. Water-soluble NaYF4:Yb,Er(Tm)/NaYF4/polymer core/shell/shell nanoparticles with significant enhancement of upconversion fluorescence. Chem. Mater. 2006, 193341–343. [Google Scholar]

- Chen G.; Shen J.; Ohulchanskyy T. Y.; Patel N. J.; Kutikov A.; Li Z.; Song J.; Pandey R. K.; Ågren H.; Prasad P. N.; Han G. (α-NaYbF4:Tm3+)/CaF2 core/shell nanoparticles with efficient near-infrared to near-infrared upconversion for high-contrast deep tissue bioimaging. ACS Nano 2012, 698280–8287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F.; Deng R. R.; Wang J.; Wang Q. X.; Han Y.; Zhu H. M.; Chen X. Y.; Liu X. G. Tuning upconversion through energy migration in core-shell nanoparticles. Nat. Mater. 2011, 1012968–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou W. Q.; Visser C.; Maduro J. A.; Pshenichnikov M. S.; Hummelen J. C. Broadband dye-sensitized upconversion of near-infrared light. Nat. Photonics 2012, 68560–564. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F.; Braun G. B.; Shi Y.; Zhang Y.; Sun X.; Reich N. O.; Zhao D.; Stucky G. Fabrication of Ag@SiO2@Y2O3:Er nanostructures for bioimaging: Tuning of the upconversion fluorescence with silver nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 13292850–2851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H.; Li Y.; Ivanov I. A.; Qu Y.; Huang Y.; Duan X. Plasmonic modulation of the upconversion fluorescence in NaYF4:Yb/Tm hexaplate nanocrystals using gold nanoparticles or nanoshells. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49162865–2868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.