Abstract

The anthrax protective antigen (PA) is an 83 kDa protein that is one of three protein components of the anthrax toxin, an AB toxin secreted by Bacillus anthracis. PA is capable of undergoing several structural changes, including oligomerization to either a heptameric or octameric structure called the prepore, and at acidic pH a major conformational change to form a membrane-spanning pore. To follow these structural changes at a residue-specific level, we have conducted initial studies in which we have biosynthetically incorporated 5-fluorotryptophan (5-FTrp) into PA, and we have studied the influence of 5-FTrp labeling on the structural stability of PA and on binding to the host receptor capillary morphogenesis protein 2 (CMG2) using 19F nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). There are seven tryptophans in PA, but of the four domains in PA, only two contain tryptophans: domain 1 (Trp65, -90, -136, -206, and -226) and domain 2 (Trp346 and -477). Trp346 is of particular interest because of its proximity to the CMG2 binding interface, and because it forms part of the membrane-spanning pore. We show that the 19F resonance of Trp346 is sensitive to changes in pH, consistent with crystallographic studies, and that receptor binding significantly stabilizes Trp346 to both pH and temperature. In addition, we provide evidence that suggests that resonances from tryptophans distant from the binding interface are also stabilized by the receptor. Our studies highlight the positive impact of receptor binding on protein stability and the use of 19F NMR in gaining insight into structural changes in a high-molecular weight protein.

The anthrax protective antigen (PA) is one of three protein components of the anthrax toxin, an AB toxin secreted by Bacillus anthracis. PA is a four-domain protein that binds to host cellular receptors,1−3 and the proteolytic cleavage of domain 1 by a cell-surface furin-like protease4 generates a 63 kDa fragment, which then oligomerizes into a heptameric5 or octameric6 doughnut-shaped structure called the prepore. Formation of the prepore creates binding sites for the two enzymatic components of the anthrax toxin, edema factor (EF) and lethal factor (LF). The complex is endocytosed into the cell, and within an acidified late endosomal compartment, the prepore undergoes a major conformational change, forming a membrane-spanning β-barrel pore.7,8 The pore provides a conduit for entry of EF and LF into the cell cytosol.9

The structures of the 83 kDa form of PA, in the unbound form or bound to host cellular receptor capillary morphogenesis protein 2 (CMG2), have been determined.5,10,11 The latter structure published by Santelli and co-workers showed that the binding interface is largely comprised of domain 4, but that a small loop within domain 2 (domain 2β3–2β4 loop, residues 340–348) binds within a groove on the surface of CMG2. From biochemical experiments by Benson and Nassi,8,12 this loop is projected to form part of the long β-barrel pore, and because of its interaction with the receptor, it was postulated that the receptor sterically inhibits the process of pore formation. Therefore, this loop must dissociate from the receptor to allow pore formation to occur.5,13 Early crystallographic evidence suggested that in the monomeric form of PA, this loop becomes disordered at low pH,10 and biochemical experiments have also suggested that interactions with this loop dictate the pH threshold for pore formation, that the loss of contacts (via mutagenesis) between PA and this loop increases the pH requisite for pore formation.14 In addition, recent saturation transfer experiments monitoring resonances in CMG2 that contact the domain 2 loop in the heptameric form of PA suggest that these contacts are weakened as the pH is lowered, supporting the view that this loop is sensitive to pH.15

Here, we have labeled PA with 5-fluorotryptophan (5-FTrp) and have studied the impact of labeling on structure and stability, using tryptophan fluorescence, circular dichroism, X-ray crystallography, and 19F nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). We also determined the effect of receptor binding on the stability to pH and temperature using 19F NMR. There are seven tryptophans located in two of the four domains of PA: domain 1 (residues 1–258), which includes the 20 kDa PA20 domain formed after cleavage by furin C-terminal to Arg16716 and includes Trp65, -90, -136, -206, and -226; and domain 2 (residues 259–487), which includes Trp346 and Trp477. Trp346 is part of the domain 2β3–2β4 loop and is closest to the CMG2 binding interface.

19F NMR is a powerful tool for studying the structure and function of proteins, as it provides residue-specific information about environmental perturbations around each fluorine nucleus.17,18 On the basis of our 19F NMR studies, we show that the Trp346 resonance undergoes conformational exchange at low pH, with very little change in the other 19F resonances, providing further support that the domain 2β3–2β4 loop is particularly sensitive to pH. In addition, we show that receptor binding stabilizes the Trp346 resonance to variations in pH and temperature along with other tryptophan residues that are more distant from the binding interface. Finally, we have determined the structure of 5-FTrp-labeled PA to 1.7 Å resolution, which exhibits nearly identical structural properties as the WT protein. Our studies highlight the use of 19F NMR to follow structural changes at a residue-specific level in a relatively high molecular weight protein and the positive impact of receptor binding on global protein stabilization.

Experimental Procedures

Materials

Urea (electrophoresis grade) and 5-fluorotryptophan were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). The urea concentration was determined by the refractive index at room temperature, and the urea was stored at −80 °C until the day of the experiment. All other chemicals prepared were reagent grade. Escherichia coli strain DL41 was obtained as a gift from the Yale E. coli genetic stock center.

Plasmid Construction and Mutagenesis

Plasmid pQE80-PA83 was used for generating mutations within the pa sequence.19 We used the following forward primers (SigmaGenosys, purified via high-performance liquid chromatography) to create the mutants Trp206Tyr (CGGTTGATGTCAAAAATAAAAGAACTTTTCTTTCACCATACATTTCTAATATTCATGAAAAGAAAGG), Trp226Phe (TCTCCTGAAAAATTCAGCACGGCTTCTGATCCGTACAGTGATTTCG), Trp346Tyr (CATTCACTATCTCTAGCAGGGGAAAGAACTTACGCTGAAACAATGGG), and Trp477Phe (GAGTGAGGGTGGATACAGGCTCGAACTTTAGTGAAGTGTTACCGC) and the corresponding reverse strands using the Quickchange mutagenesis kit from Stratagene. Sequences were confirmed at the Protein Nucleic Acid Laboratory (PNACL) at Washington University in St. Louis (St. Louis, MO).

Protein Production

The pQE80-PA83 plasmid was transformed into E. coli tryptophan auxotrophic strain DL41 grown in the presence of 100 μg/mL ampicillin. Cells were grown in a defined medium that is identical to ECPM1, but substituting the casamino acids for defined amino acids.18 The tryptophan concentration was 0.25 mM. Cells were grown to an optical density (OD600) of 3.0 at 32 °C. The cells then were washed twice with 0.9% NaCl; then the same medium containing 0.25 mM 5-FTrp in place of tryptophan was added to the cells, and the cells were resuspended. The cells were then incubated for 10 min prior to the addition of IPTG to a final concentration of 1 mM at 26 °C, and grown for an additional 2–3 hours prior to harvesting.

Protein Purification

For the preparation of PA, after the OD had reached 6.0, bacterial cells were centrifuged and resuspended in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 20% sucrose, and 1 mM EDTA for 15 min at room temperature. The cells were centrifuged for 15 min at 8000g and 4 °C, and the pellet was resuspended in ice-cold 5 mM MgSO4. Before centrifugation, 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) was added to a final concentration of 20 mM, and cells were again centrifuged at 4 °C (8000g). The supernatant was filtered (0.2 μM, Millipore) and applied to a Hi-Trap Q anion exchange column pre-equilibrated in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) at 4 °C. PA was eluted with a NaCl gradient on an Aktä Prime LC system. Fractions were concentrated using an Amicon Ultra-15 10 kDa centrifugal filter (Millipore) and then applied to a Sephadex S-200 gel filtration column pre-equilibrated in 20 mM Tris-HCl and 150 mM NaCl (pH 8.0) at 4 °C. Pure protein fractions were identified using sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), pooled, and concentrated. CMG2 was prepared and purified as described previously.20 Purification of PA20 was conducted using a trypsin nicking protocol, whereby 10 mg of PA or 5-FTrpPA was digested with 10 μg of Trypzean (Sigma) for 30 min at room temperature, followed by the addition of an excess of soybean trypsin inhibitor (100 μg) on ice. The PA20 was purified over a H-Trap Q column equilibrated in 20 mM Tris (pH 8.5) and 1 mM CaCl2, eluting with a NaCl gradient.

Fluorescence

Data were recorded on a Cary Eclipse spectrofluorimeter equipped with a Peltier cooling system, using an excitation wavelength of 280 or 295 nm with slit widths set at 5 nm for both excitation and emission. All measurements were taken at 20 °C in a 50 mM Tris/25 mM MES/25 mM acetic acid buffer system, using 1 μM for pH experiments and 0.8 μM for the urea denaturation experiments. For the pH and urea experiments, only 295 nm excitation was used, recording emission data for the WT at 330 or 333 nm for the 5-FTrp-labeled PA or PA20 proteins, and the data are an average of five scans from 300 to 600 nm. All samples were incubated overnight at the respective pH or urea concentrations to allow for adequate equilibration. For the pH experiments, the solid lines through the data points are nonlinear least-squares fits of the data to the Henderson–Hasselbalch equation to give an apparent pKa for the pH transition. For the urea denaturation experiments, in the case of the full-length PA proteins, the data were fit to a three-state transition as described previously.19 For the PA20 urea denaturation experiments, the denaturation curves were fit to a two-state model with sloping baselines according to the model described by Clarke and Fersht.21 The curves were fit using Kaleidagraph version 3.6 (Synergy Software, Reading, PA).

Circular Dichroism (far UV)

Measurements were performed using a Jasco J810 spectropolarimeter. Spectra were measured in 10 mM HEPES (pH 8.0) at a concentration of 8 μM, using a 0.1 cm path length cell. The response time was 2 s, and the scan rate was 20 nm/min.

19F NMR Spectroscopy

Spectra were acquired on a Varian INOVA 400 MHz spectrometer equipped with a tunable inverse detection probe. Spectra were recorded at 20 °C unless otherwise indicated, and sample concentrations were typically in the 200 μM range in 50 Tris/25 mM Mes/25 mM AcOH buffer (pH 8.0) with 10% D2O added for a field frequency lock. Spectra were acquired using a 90° pulse width and a recycle delay of 5 s and were referenced to an internal standard of 4-fluorophenylalanine as described previously.22 Spectra typically required >10000 transients for adequate peak visualization and were processed with 10 Hz of line broadening.

MTSL Spin-Labeling

The 5-FTrpPA Glu712Cys protein was expressed and purified as described previously.11 We added 1 mM DTT to the final MgSO4/Tris (pH 8.0) step in the isolation of periplasm, and column buffers for purification included 1 mM DTT. The 5-FTrpPA was purified and the DTT removed by loading the protein solution onto a PD-10 column equilibrated with buffer containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.25) and 150 mM NaCl and then eluted using the same buffer. Immediately after purification, a 10-fold molar excess of MTSL [S-(2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-2,5-dihydro-1H-pyrrol-3-yl)methyl methanesulfonothioate] in methanol was added for 30 min at room temperature; then an additional 10-fold molar excess of MTSL was added, and this solution was incubated overnight at 4 °C. The next day, MTSL was removed using an S-200 gel filtration column equilibrated in 50 mM Tris/25 mM Mes/25 mM AcOH buffer (pH 8.0) at 4 °C. The sample was split into two aliquots, each containing 207 μL of PA, 50 μL of D2O, 1 μL of 10 mM p-fluorophenylalanine, and 217 μL of 50 mM Tris/25 mM Mes/25 mM acetic acid buffer. To one tube was added 25 μL of water, and to the other was added 25 μL of 100 mM TCEP. The final PA concentration in each tube was 150 μM.

Crystallization and Data Collection

5-FTrpPA was concentrated to 10 mg/mL in 150 mM NaCl and 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0) for crystallization. Screeing was conducted in Compact Jr. (Emerald biosystems) sitting drop vapor diffusion plates at 20 °C using equal volumes of protein and crystallization solution. Plate-shaped crystals (∼200 μm × 100 μm) were obtained in 1 day from the Index HT screen (Hampton Research) condition E8 [35% (v/v) pentaerythritol propoxylate (5/4 PO/OH), 0.05 M HEPES (pH 7.5), and 0.2 M potassium chloride] equilibrated against 100 μL of the crystallization solution at 20 °C. Single crystals were transferred to a fresh drop of the crystallization solution (Index E8), which served as the cryoprotectant, and frozen in liquid nitrogen prior to the collection of data. Initial X-ray diffraction data were collected in house using a Bruker Microstar microfocus rotating anode generator equipped with Helios MX multilayer optics and a Platinum-135 CCD detector. Data were processed using the Proteum2 software package (Bruker-AXS). High-resolution data were collected at the Advanced Photon Source IMCA-CAT beamline 17ID using a Dectris Pilatus 6M pixel array detector.

Structure Solution and Refinement

Intensities were integrated using XDS,23 and Laue class analysis and data scaling were performed with Aimless,24 which suggested that the highest-probability Laue class was mmm and space group P212121. The structure was determined by molecular replacement with Molrep25 using a previously determined structure of the protective antigen as the search model [Protein Data Bank (PDB) entry 3MHZ)] as the search model. The in-house X-ray diffraction data, processed to 2.2 Å resolution, were used for the initial structure solution and refinement, and the higher-resolution synchrotron data were used for refinement of the final model. Structure refinement using and manual model building were conducted with Phenix26 and Coot,27 respectively. TLS refinement28 was incorporated in the final stages to model anisotropic motion. Structure validation was conducted with Molprobity,29 and figures were prepared using the CCP4MG package.30 Coordinates and structure factors for 5-FTrpPA were deposited to the Protein Databank with the accession code 4NAM.

Results

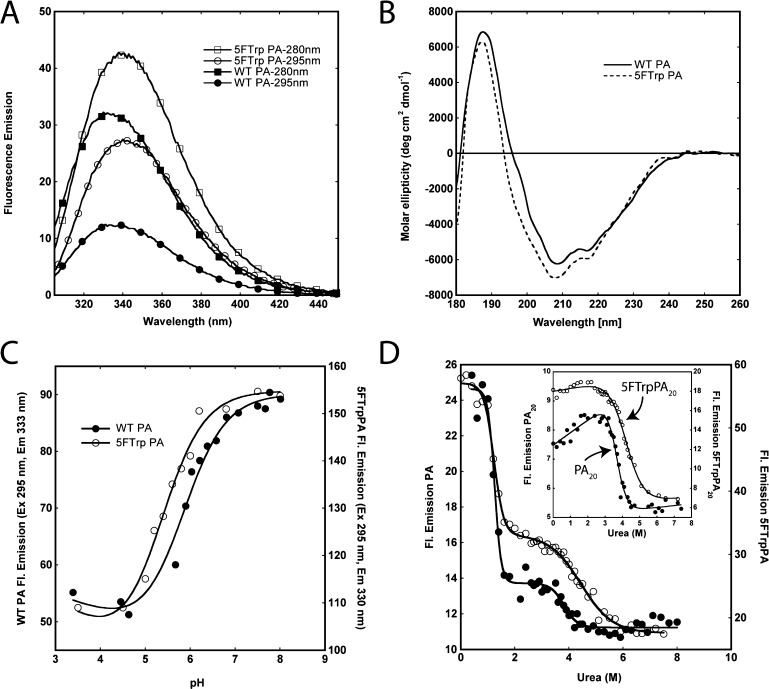

PA was labeled with commercially available 5-FTrp using the tryptophan auxotroph DL41, and proteins were >95% labeled as determined by electrospray mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) (Table S1 and Figure S1 of the Supporting Information). To determine the effect of labeling on the structure and stability of PA, we compared labeled and unlabeled proteins by far-UV circular dichroism (CD) to compare secondary structural content and measured the stability of the proteins to urea and pH using fluorescence. The fluorescence emission spectrum (excitation at 280 or 295 nm) is shown in Figure 1A. The spectrum of the 5-FTrp-labeled PA (5-FTrpPA) is red-shifted relative to that of the unlabeled WT by ∼8 nm, with excitation at either 280 or 295 nm. We also observe an increase in the amplitude of the emission spectrum of 5-FTrpPA via excitation at 280 or 295 nm compared to that of the unlabeled WT protein, with an increase that is somewhat smaller than those observed in other studies labeling with this amino acid.31 The CD spectra of the WT and labeled proteins were similar (Figure 1B), except for the absence of a small shoulder in the 5-FTrpPA spectrum at 198 nm.

Figure 1.

Effect of 5-FTrp labeling on the spectroscopic properties and stability to urea and pH of PA. (A) Emission spectra (excitation at 280 or 295 nm) of WT PA and 5-FTrpPA at 1 μM in 50 mM Tris/25 mM Mes/25 mM AcOH buffer (pH 8.0) at 20 °C. (B) Circular dichroism spectra of WT (―) and 5-FTrpPA (---) at 8 μM in 10 mM Hepes/OH (pH 8.0) at 20 °C. (C) Unfolding of WT and 5-FTrpPA as a function of pH at 0.8 μM in 50 mM Tris/25 mM Mes/25 mM AcOH buffer at 20 °C. Fluorescence data were acquired using an excitation wavelength of 295 nm, and solid lines through the data are fits to the Henderson–Hasselbalch equation. (D) Unfolding of WT (●) and 5-FTrpPA (○) as a function of urea concentration. The inset shows unfolding of PA20 and 5-FTrpPA20. Data were collected in 50 mM Tris/25 mM Mes/25 mM AcOH buffer (pH 8.0) at 20 °C, via excitation at 295 nm and collection of the emission intensity at 330 nm (unlabeled) and 333 nm (5-FTrp-labeled). The concentration of all proteins was 0.8 μM. Solid lines represent nonlinear least-squares fits to the data.

We used fluorescence to determine if the stability of PA to pH and urea was affected by the incorporation of 5-FTrp (Figure 1C,D). The unfolding of 5-FTrpPA as a function of pH is similar to that of the WT protein, with a pKapp of 5.3 compared to a pKapp of 5.8 for the WT protein. In contrast to pH unfolding, which exhibits a single transition, the unfolding of PA and 5-FTrpPA by urea at 20 °C and pH 8.0 exhibits two transitions, one with a midpoint (CM) at ∼1 M urea and a second that occurs at a CM of ∼4 M urea.19 The results from the pH and urea studies are summarized in Table 1. The isolated PA20 (residues 1–167) (see below) domain exhibits an unfolding transition that matches the second transition observed in the fluorescence unfolding of PA (inset of Figure 1D), and thus, we assign the unfolding of the PA63 region comprising domains 1′ to domain 4 (residues 168–734; domain 1′ includes residues from the furin cleavage site to the beginning of domain 2) to the first transition at 1 M urea and the unfolding of PA20 to the second, smaller amplitude transition that occurs at ∼4 M urea.

Table 1. Equilibrium Unfolding Thermodynamic Parameters of WT and 5-FTrp-Labeled PA and PA20.

| experimenta | pKapp | ΔG°N↔I (kcal mol–1) | ΔG°I↔U (kcal mol–1) | mN↔I (kcal mol–1 M–1) | mI↔U (kcal mol–1 M–1) | CM,N↔I (M) | CM,I↔U (M) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT PA | 5.8 ± 0.06b | 6.2 ± 0.9c | 9.1 ± 3.4 | 4.8 ± 0.7 | 2.4 ± 0.9 | 1.3 ± 0.02 | 3.8 ± 0.1 |

| 5-FTrpPA | 5.3 ± 0.05 | 3.8 ± 0.4 | 4.4 ± 0.5 | 3.2 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.02 | 4.4 ± 0.2 |

| ΔG°N↔Ud (kcal mol–1) | mN↔U (kcal mol–1 M–1) | CM,N↔U (M) | |||||

| PA20 | ND | 7.4 ± 1.1 | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 3.7 ± 0.05 | |||

| 5-FTrpPA20 | ND | 5.0 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 4.2 ± 0.08 |

All data were recorded at 20 °C using a Cary Eclipse spectrofluorimeter.

Errors in pKapp were determined by best fit to the Henderson–Hasselbalch equation, and errors in m and CM were obtained from nonlinear least-squares fitting of the data to a three-state model in Kaleidagraph.19

Errors in ΔG° were determined using the relationship [m2(seCM2) + CM2(sem2)]1/2, where seCM2 and sem2 are the standard errors in CM and m, respectively.

PA20 ΔG° values were determined for a single two-state N ↔ U transition with sloping baselines.21

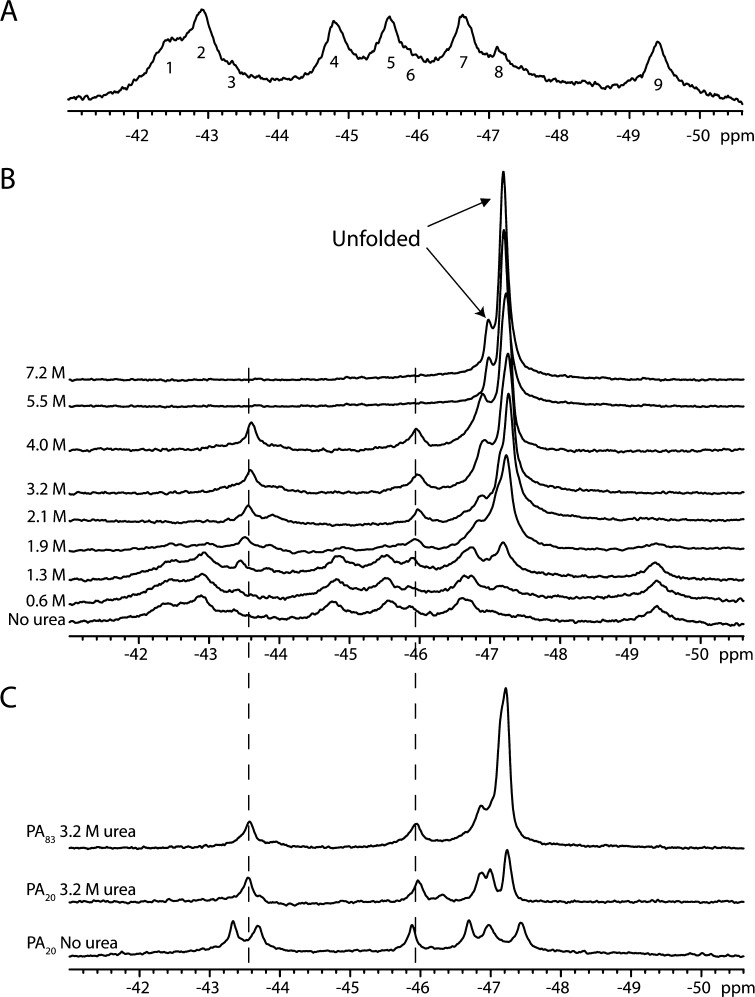

Urea Unfolding of 5-FTrp-Labeled PA by NMR and Assignment of the PA20 Resonances

Figure 2A shows the 400 MHz 19F NMR spectrum of 5-FTrpPA at pH 8.0 and 20 °C. The spectrum shows at least nine separate resonances with varying amplitudes and line widths over an ∼8 ppm range. To make initial resonance assignments, we took advantage of the fact that urea denaturation occurs with two separate transitions and postulated that we may be able to identify those resonances that arise from PA20 by following the resonances as a function of urea concentration (Figure 2B). The amplitudes of resonances at −42.3, −42.9, −44.8, −45.6, and −49.4 ppm decrease, and those resonances disappear at ∼1.9 M urea. However, the amplitudes of the small resonances at −43.4 and −45.8 ppm increase up to ∼4 M urea, and then disappear at 5.5 M urea, consistent with the second transition observed in the fluorescence experiments. The amplitude of the resonance at −46.6 ppm increases, and the resonance shifts upfield to −46.8 ppm up to 4 M urea; then a second shift to −47 ppm is observed at 5.5 M urea. Because these latter resonances persist at higher denaturant concentrations and generally follow the second transition observed by fluorescence, we tentatively assigned these resonances to the PA20 domain. The resonance at −47.2 ppm, the magnitude of which increases as the denaturant concentration is increased, was assigned to denatured resonances, because it resonates close to the frequency for free 5-FTrp (−47 ppm). Because the spectrum is not proton-decoupled, we could not distinguish individual resonances in the unfolded state at high urea concentrations, and therefore, this resonance likely encompasses the sum denatured states of a majority of the labeled tryptophans.

Figure 2.

(A) 19F NMR spectrum of 5-FTrpPA (230 μM). This spectrum represents 12000 transients in 50 mM Tris/25 mM Mes/25 mM AcOH buffer (pH 8.0) with 10% D2O. Data were referenced to an internal standard of 0.02 mM pF-Phe and processed with 10 Hz line broadening. (B) Urea denaturation of 5-FTrpPA as measured using 19F NMR. Each spectrum represents 7000 transients recorded at 20 °C at 300 μM in 50 mM Tris/25 mM Mes/25 mM AcOH (pH 8.0) with 10% D2O. (C) Comparison of 19F NMR spectra of 5-FTrp PA20 to that of full-length PA (PA83) at 3.2 M urea. The PA20 spectrum was recorded at 150 μM and represents 16000 transients recorded at 20 °C. Note that the resonances in PA83 at −43.5, −46, and −46.8 ppm are at positions identical to those of PA20. Data were referenced to an internal standard of 0.02 mM pF-Phe.

On the basis of these observations, we assigned the resonances that disappear at ∼2 M urea to that of the PA63 region and the remaining folded resonances that persist up to 4 M urea to the PA20 domain. To confirm this assignment, we conducted limited proteolysis of the labeled PA with trypsin, which can be used in lieu of furin to cleave PA20 from PA83, isolated PA20, and compared the resonances at 0 and 3.2 M urea to that of the WT protein (Figure 2C). First, the isolated PA20 without urea exhibits six resonances for three tryptophans, suggesting these tryptophans are in slow chemical exchange. Although these resonances show differences in the number of peaks and chemical shifts relative to those of PA, the resonances observed at 3.2 M urea are nearly identical in chemical shift and intensity to that observed in the full-length protein. On the basis of this comparison, we assign the resonances from the native spectrum of PA (−43.4, −45.9, and −46.6 ppm) to that of PA20.

Mutagenesis To Assign Resonances in the PA63 Region

At this point, we decided not to pursue assignment of the PA20 resonances by mutagenesis but rather focus on those resonances that would be found in the heptameric prepore state. To assign the resonances in the PA63 region, we introduced relatively conserved mutations (Trp → Phe or Tyr) that in theory would not disrupt stability or folding and thus not perturb the 19F NMR spectrum; the mutation would result only in a loss of one of the resonance peaks.32 The following mutants were made: Trp206Tyr, Trp226Phe, Trp346Tyr, and Trp477Phe. We could not produce the labeled Trp226Phe and Trp477Phe proteins, probably because of an effect on the stability of the protein. Trp226 is relatively solvent exposed but is located ∼5 Å from the two calcium ions in the structure, and the carbonyl of Trp226 forms a hydrogen bond with the amide hydrogen of Asp235, which coordinates one of the calcium ions. Thus, a tryptophan at position 226 may provide a necessary conformational constraint for calcium binding that cannot be achieved if this residue is a phenylalanine. Trp477 is near the N-terminus of the domain 2α3 helix that bridges interactions with domain 3, and local contacts around Trp477 include Pro232 and Tyr233 (domain 1′) and Pro260, Pro373, and Ileu459 (domain 2), forming a hydrophobic pocket. A phenylalanine at this position may disrupt the local van der Waals contacts, potentially destabilizing contacts that span a range of ∼200 residues.

We could produce the labeled Trp346Tyr, but only at very low levels. In initial experiments, we tried labeling the Trp346Phe mutant for which we have a three-dimensional crystal structure;11 however, this labeled protein proved to be too unstable, and we could not accumulate enough pure protein for a spectrum. We were able to obtain enough labeled protein for a spectrum of Trp346Tyr (Figure 3A), but this mutant was also unstable and showed significant chemical shift changes in the native spectrum that made assignment of this resonance difficult. We note that the resonance at −49.5 ppm is missing; however, this may have shifted downfield to the new resonance that appears at −48 ppm.

Figure 3.

19F NMR peak assignment through mutagenesis. (A) 19F NMR spectra of WT PA, Trp206Tyr PA, and Trp346Tyr PA. Data were recorded at 20 °C and 230 μM (WT), 250 μM (Trp206Tyr), or 200 μM (Trp346Tyr) in 50 mM Tris/25 mM Mes/25 mM AcOH buffer (pH 8.0) with 10% D2O. Spectra represent 12000, 11000, and 14000 transients, respectively, with a 5 s relaxation delay. (B) Comparison of WT and Trp206Tyr at 3.2 M urea. Both are at 150 μM and 16000 transients. Data were referenced to an internal standard of 0.02 mM pF-Phe.

The Trp206Tyr protein exhibits a spectrum that is nearly identical to that of the WT labeled protein, and the only loss in intensity that we observe is the loss of the small peak at −47.2 ppm (Figure 3A). We had initially assigned this resonance to a partially denatured form of PA that exists in the absence of denaturant (Figure 3A) but may be due to the Trp206 resonance. In any case, the lack of resonance intensity for this tryptophan suggests that Trp206 may be undergoing moderately fast chemical exchange, which could result in significant line broadening. Consistent with this notion, the B factors in this region are typically high across crystal structures of PA determined to date, suggesting that this residue may be able to sample multiple conformational environments.

To determine whether the line broadening of Trp206 was due to factors that depended on the protein conformation, we purified both the labeled PA and Trp206Tyr proteins and partially denatured these at 3.2 M urea, which is at the midpoint between the two identified transitions. The addition of denaturant to the approximate midpoint of the transition should lead to unfolded resonances corresponding to Trp206, -226, -346, and -477, while the resonances corresponding to PA20 should remain largely folded. For Trp206Tyr, the unfolded resonance should exhibit a smaller amplitude, corresponding to the loss of a single fluorine. At 3.2 M urea, we observe a major resonance at −47.2 ppm, and three smaller resonances (−43.6, −46, and −47 ppm) (Figure 3B). The three smaller resonances we attribute to the PA20 domain (see Figure 3B for comparison). Importantly, at 3.2 M urea, we observe a loss in the unfolded resonance intensity, likely due to the loss of a fluorine resonance from the Trp206Tyr mutation.

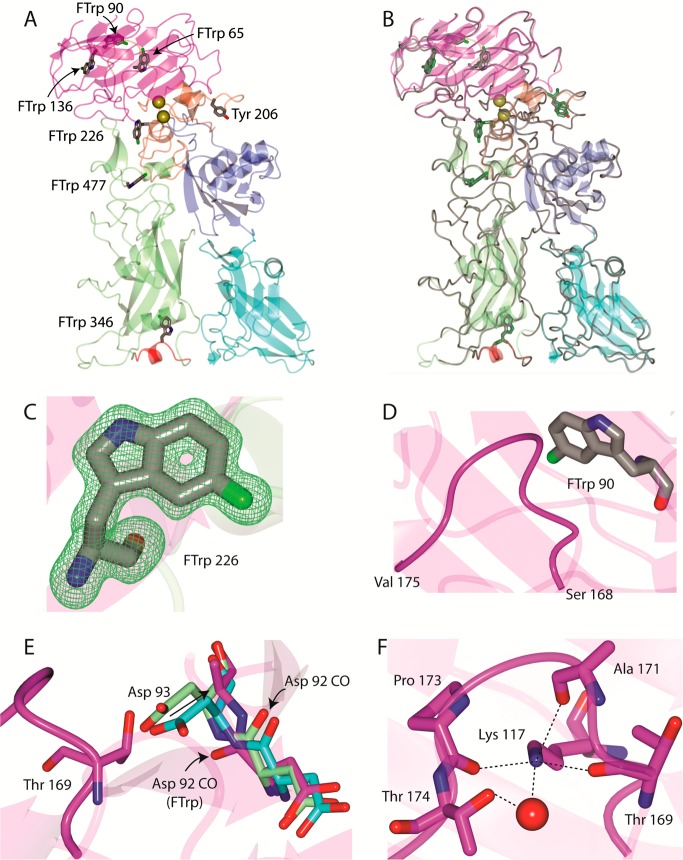

Crystallization of the 5-FTrp-Labeled W206Y Mutant

To further determine if there are structural changes upon labeling, we crystallized the W206Y mutant, the structure of which was determined to 1.7 Å resolution. The structure is shown in Figure 4, and data collection and refinement statistics are listed in Table 2. The structure overlays well with those of the WT and 2-FHis-labeled protein (PDB entries 3Q8B and 3MHZ, respectively), again indicating that 5-FTrp labeling only minimally perturbs the structure of the protein. However, there are some subtle structural changes and new contacts to the fluorine atoms that are formed, in particular within the PA20 domain.

Figure 4.

(A) X-ray crystal structure of 5-FTrpPA (Trp206Tyr) refined to 1.7 Å resolution. The positions of the 5-fluorotryptophan (FTrp) (gray) and Tyr206 residue are represented as cylinders. PA is colored as follows: magenta for the PA20 portion of domain 1, orange for domain 1′, green for domain 2, blue for domain 3, and cyan for domain 4. The domain 2β2–2β4 loop that contacts the receptor is colored red, and Ca2+ ions are shown as gold spheres. (B) Superposition of WT PA (PDB entry 3Q8B) drawn in worm style (gray). The Trp residues in WT PA are colored green. (C) Representative electron density map (Fo – Fc omit) for residue FTrp 226 contoured at 3σ. (D) Loop spanning Ser168–Val175 that could be traced to the electron density in the current structure. (E) Thr169 in the PA 5-FTrp structure (magenta) would clash with Asp93 as shown for PDB entries 3MHZ (green) and 3Q8B (cyan). Therefore, Asp93 in PA 5-FTrp is moved away from the Ser168–Val175 loop as indicated by the arrow. Note that the side chain was disordered for Asp93 in the PA 5-FTrp structure. This results in a change in the backbone carbonyl conformation of Asp92 as indicated by the asterisks. (F) Contacts between Lys117 and the Ser168–Val175 loop. A water-mediated contact is formed with Thr174.

Table 2. Crystallographic Data for Protective Antigen 5-FTrp (W206Y).

| Data Collection | |

| unit cell parameters (Å) | a = 71.30, b = 93.95, c = 117.70 |

| space group | P212121 |

| resolution (Å)a | 46.98–1.70 (1.73–1.70) |

| wavelength (Å) | 1.0000 |

| temperature (K) | 100 |

| no. of observed reflections | 348394 |

| no. of unique reflections | 86339 |

| ⟨I/σ(I)⟩a | 12.4 (1.8) |

| completeness (%)a | 99.8 (99.0) |

| multiplicitya | 4.0 (4.1) |

| Rmerge (%)a,b | 6.6 (71.7) |

| Rmeas (%)a,d | 7.6 (83.5) |

| Rpim (%)a,d | 3.7 (39.8) |

| CC1/2a,e | 0.998 (0.792) |

| Refinement | |

| resolution (Å)a | 46.98–1.70 |

| no. of reflections (working/test)a | 78632/4149 |

| Rfactor/Rfree (%)a,c | 17.9/20.9 |

| no. of atoms (protein/Ca2+/water) | 5351/2/400 |

| Model Quality | |

| rmsd | |

| bond lengths (Å) | 0.009 |

| bond angles (deg) | 1.108 |

| average B factor (Å2) | |

| all atoms | 27.4 |

| protein | 27.2 |

| Ca2+ | 13.5 |

| water | 29.6 |

| coordinate error (maximum likelihood) (Å) | 0.15 |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | |

| most favored | 96.9 |

| additionally allowed | 3.1 |

Values in parentheses are for the highest-resolution shell.

Rmerge = ∑hkl∑i|Ii(hkl) – ⟨I(hkl)⟩|/∑hkl∑iIi(hkl), where Ii(hkl) is the intensity measured for the ith reflection and ⟨I(hkl)⟩ is the average intensity of all reflections with indices hkl.

Rfactor = ∑hkl||Fobs(hkl)| – |Fcalc(hkl)||/∑hkl|Fobs(hkl)|; Rfree is calculated in an identical manner using 5% of the randomly selected reflections that were not included in the refinement.

For example, when comparing the structure of 5-FTrp to those of the WT (PDB entry 3Q8B) and 2-fluorohistidine-labeled (PDB entry 3MHZ) forms,33,34 we noticed that particular regions could be traced to the electron density maps in the former that were disordered in the latter two structures. This includes the Lys72-Lys73 backbone, Glu51–Glu54, and the Ser168–Val175 loop. The Ser168–Val175 loop is in the proximity (3.5–4.0 Å) of Trp90 (Figure 4D). This results in a conformational change in the nearby loop spanning Trp90–Gln94 relative to PDB entries 3Q8B and 3MHZ. Specifically, Asp93 moves away from the Ser168–Val175 loop as it would clash with Thr169, which results in a change in the backbone conformation at Asp92 (Figure 4E). This permits the formation of a water-mediated contact to the backbone carbonyl of Gln115. Stabilization of the Ser168–Val175 loop occurs by interactions with Lys117 as shown in Figure 4F.

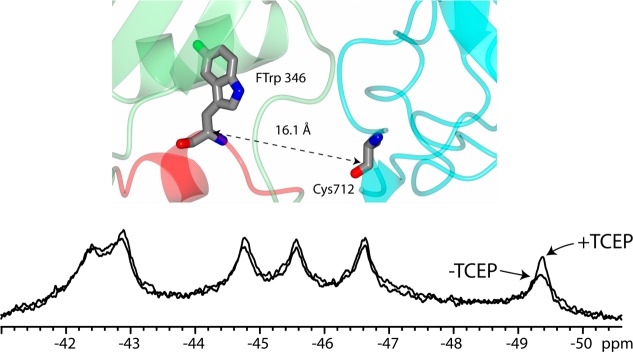

Assignment of the Trp346 Resonance Using PRE

Because of the instability of the Trp346Tyr mutant, we could not conclusively assign this resonance (Figure 3) and thus used paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE) to aid us in assigning this resonance. We did this by generating a cysteine mutant of a nearby residue located in domain 4, Glu712Cys. There are no cysteines naturally in PA, and thus the Glu712Cys mutant is the only residue available for labeling and does not affect the function of PA.11,35 The Cα–Cα distance between Glu712Cys and Trp346 is ∼16 Å (Figure 5), within the range for which PRE can be observed.36

Figure 5.

19F NMR peak assignment through paramagnetic relaxation enhancement. Glu712Cys PA was labeled with the nitroxide spin-label MTSL. Cys712 is the only cysteine present in PA. The closest tryptophan to Cys712 is Trp346, and the Cα–Cα distance is 16.1 Å (top). Spectra with or without the reducing agent TCEP are shown. Data were recorded at 20 °C and 150 μM in 50 mM Tris/25 mM Mes/25 mM AcOH buffer (pH 8.0) with 10% D2O. Spectra represent 8800 transients, with a 5 s relaxation delay. Data were referenced to an internal standard of 0.02 mM pF-Phe.

We labeled Glu712Cys with MTSL [S-(2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-2,5-dihydro-1H-pyrrol-3-yl)methyl methanesulfonothioate] and compared the spectrum of MTSL-labeled PA to that of MTSL-labeled PA treated with TCEP, which reduces the paramagnetic nitroxide spin-label to a diamagnetic species.37 The 19F NMR spectrum of MTSL-labeled PA, in the absence and presence of TCEP, is shown in Figure 5. The resonance at −49.5 ppm exhibited the largest increase in amplitude in the presence of TCEP, and thus, we assigned this resonance to Trp346. Assignment of this tryptophan was also corroborated by measurements of pH sensitivity and receptor binding (see below).

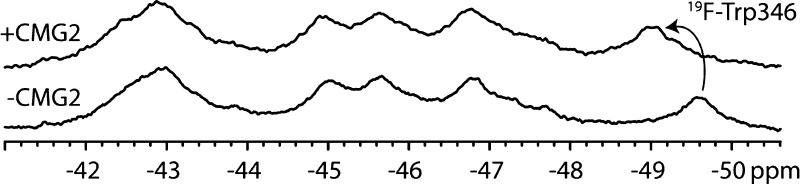

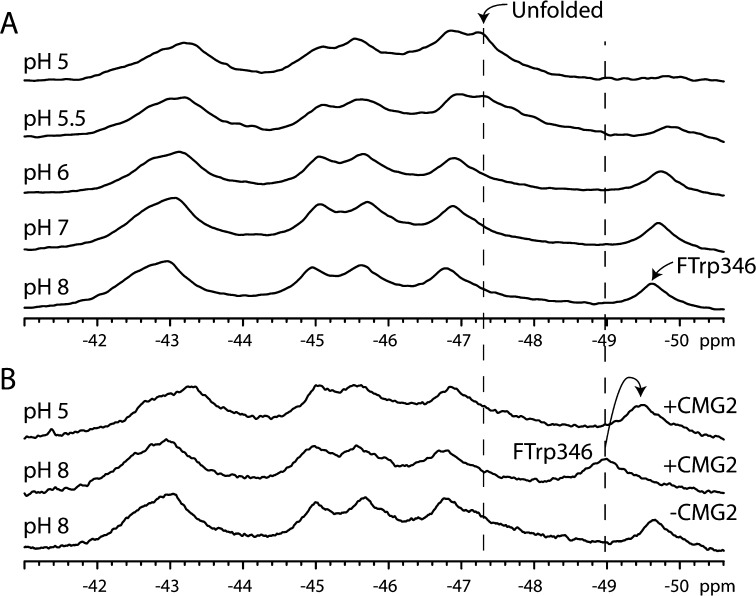

19F NMR Experiments as a Function of pH

Figure 6A shows the effect of pH on the resonances of PA. The most dramatic change is the loss of the Trp346 resonance at low pH (pH 5), and this is most likely due to an increase in the level of chemical exchange. We did not observe a significant loss of the other remaining resonances, suggesting that this resonance alone was sensitive to pH. We also note that the intensity of the unfolded resonance at −47.2 ppm increases as the pH is lowered, which is concomitant with the decrease in intensity observed for the folded Trp346 resonance. We reasoned that, because the domain 2β3–2β4 loop binds in a groove on the receptor surface, receptor binding should result in an environmental change in Trp346. Furthermore, receptor binding results in stabilizing contacts to the domain 2β3–2β4 loop13 and is known to stabilize the prepore against variations in pH that result in pore formation (pH 5–6),14 and thus, the Trp346 should be less prone to undergoing chemical exchange when it is bound to the receptor. In Figure 6B, we compare spectra of PA and PA with a 2-fold excess of CMG2 at pH 8.0 and 5.0. There is a substantial chemical shift change in the Trp346 resonance (from −49.6 to −49 ppm) at pH 8.0, but very little change in the other resonances, again indicating that the resonance at −49.6 ppm is the Trp346 resonance. At pH 5, the resonance has moved to −49.4 ppm but remains visible, and there is a lack of a discernible unfolded resonance. This indicates that receptor binding has stabilized the protein to variations in pH.

Figure 6.

19F NMR spectra of 5-FTrpPA alone (A) and in the presence of the host receptor capillary morphogenesis protein 2 (CMG2) (B) as a function of pH. Spectra in panel A represent 12000 transients and were recorded at 5 °C and 250 μM in 50 mM Tris/25 mM Mes/25 mM AcOH buffer with 10% D2O and referenced to an internal standard of pF-Phe (0.02 mM). In panel B, spectra represent 16000 transients and were recorded as described for panel A but with 150 μM 5-FTrpPA and 300 μM CMG2.

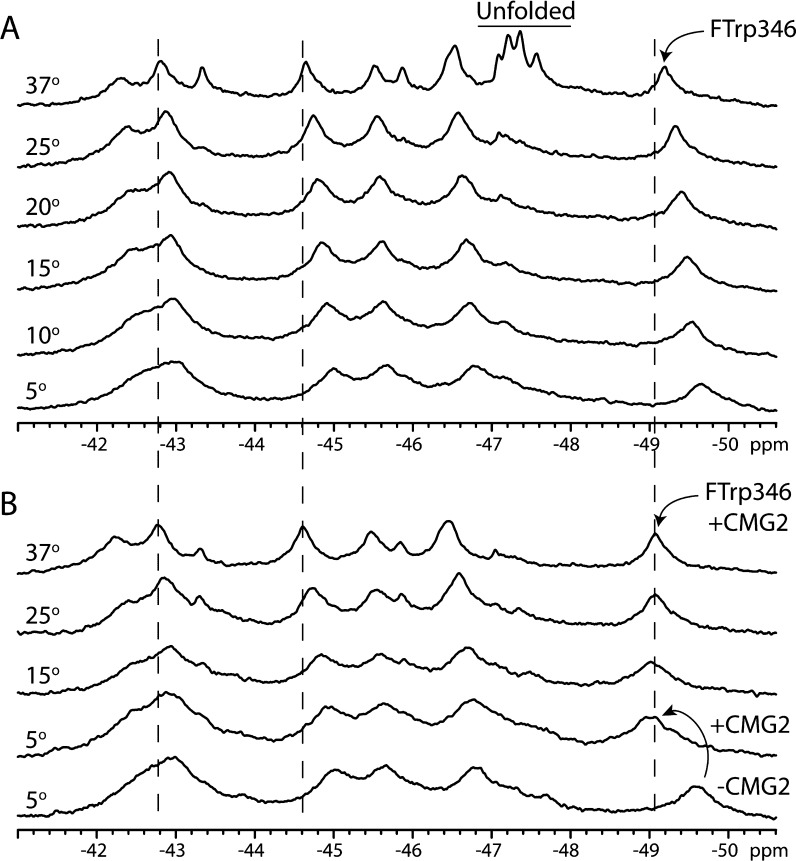

19F NMR Experiments as a Function of Temperature

We wanted to further explore the effect of receptor binding on the structure of the protein, focusing on the temperature dependence of the resonances. Our expectation was that the Trp346 resonance would experience an increase in the level of chemical exchange as the temperature increased, reducing the resonance amplitude. The results of our temperature experiments in the absence of receptor are shown in Figure 7A and in the presence of receptor in Figure 7B. In Figure 7A, the amplitudes of two of the resonances that correspond to PA20 (−43.4 and −45.9 ppm) undergo a sharp increase at 37 °C. Also, at 37 °C, the unfolded resonance (−47.2 to −47.6 ppm) appears as a broad peak with four distinct resonances. These are likely the unfolded resonances within the PA63 region. For Trp346, this resonance experienced the largest chemical shift change, moving from −49.6 ppm at 5 °C to −49.2 ppm at 37 °C. With the exception of the PA20 resonances, the amplitude of the resonances decreased as the temperature increased, and by the same degree. Thus, Trp346 seemed to be as sensitive to temperature as the remaining PA63 resonances.

Figure 7.

19F NMR spectra of 5-FTrpPA alone (A) and in the presence of the host receptor capillary morphogenesis protein 2 (CMG2) (B) as a function of temperature. Spectra in panel A represent 12000 transients at 250 μM in 50 mM Tris/25 mM Mes/25 mM AcOH buffer with 10% D2O. In panel B, spectra represent 9000 transients and were recorded as described for A but with 300 μM 5-FTrpPA and 600 μM CMG2. Note the lack of an unfolded resonance at 37 °C in panel B compared to panel A. Data were referenced to an internal standard of 0.1 mM pF-Phe.

In Figure 7B, we added a 2-fold excess of the receptor CMG2 and conducted sets of experiments identical to that described in 7A. Again we observe the downfield shift in the Trp346 resonance when the receptor is bound, but as the temperature is increased, the Trp346 resonance does not shift any further. The major difference we observe is the significantly reduced amplitude of the unfolded resonances. Furthermore, while there is a small increase in the amplitudes of the two PA20 resonances (−43.4 and −45.9 ppm), the increase is smaller than that observed in the absence of the receptor, suggesting that the effect of receptor binding is not simply a local effect but can be transmitted to residues within domain 1.

Discussion

PA undergoes several structural changes during the course of anthrax toxin pathogenesis, including receptor binding followed by oligomerization and endocytosis, and at acidic pH the formation of a membrane-spanning pore.38 In an effort to improve our understanding of these structural changes at a residue-specific level, we have conducted an initial study whereby we have biosynthetically incorporated 5-FTrp into the monomeric, 83 kDa form of PA and have used 19F NMR to probe the structure of the protein under a variety of conditions.

To determine the effect of fluorine labeling on the stability of the protein, we conducted pH and urea denaturation experiments, following unfolding by monitoring the changes in tryptophan fluorescence. The results of these experiments, which again are summarized in Table 1, suggest that while 5-FTrpPA is slightly more stable to acidic pH than the WT, the 5-FTrp-labeled PA or PA20 domain exhibits a small decrease in the ΔG° of unfolding to urea, which seems mainly attributable to differences in the m values. However, an important caveat in the interpretation of these differences is the fact that the fluorescence properties of the 5-FTrp and Trp are different31 (see Figure 1A), and the pre- and post-transition baselines are not well-defined. Clearly, further work is needed to elucidate the potential thermodynamic differences between the fluorine-labeled and unlabeled proteins.

We also report the 1.7 Å crystal structure of the 5-FTrp-labeled PA Trp206Tyr, and the structure shows some small differences in comparison to that of the WT protein, most notably the fact that we are able to observe regions of electron density that are missing in the WT structure. Importantly, both structures overlay well with one another (Figure 4B), indicating that 5-FTrp labeling is minimally perturbing to the structure. Because the native state structures of the labeled and unlabeled proteins are similar, this lends strong support to the conclusions we draw with the 5-FTrp-labeled PA, that the effects that we observe by NMR (pH sensitivity and effects of CMG2 binding, for instance) are likely to be similar to that of the WT protein.

The ability to assign the Trp346 resonance, which lies near the interface between PA and CMG2,13 allowed us to probe how this resonance changes in the presence of the receptor and whether the Trp346 resonance is sensitive to variations in pH. The first crystal structure of PA10 postulated that the domain 2β3–2β4 loop was sensitive to pH and that at lower pH values the electron density within this region became disordered. We have also crystallized PA and compared structures a low and high pH; in some structures, we could observe an increase in the level of disorder at low pH (∼5), whereas the WT protein, surprisingly, showed no increase in the level of disorder.11 We find that the resonance intensity of Trp346 specifically decreases as the pH is lowered, providing strong evidence that the domain 2β3–2β4 loop undergoes conformational exchange at low pH. The mechanism of the structural change that occurs in this loop as the pH is lowered has yet to be determined.

Receptor binding clearly has a stabilizing influence on the structure of the protein. While Trp346 undergoes a substantial chemical shift change (∼0.6 ppm) upon receptor binding, we did not observe the same loss of intensity of this resonance either at low pH or at higher temperatures. Also, the unfolded resonance intensity is attenuated (low pH or higher temperatures) when the receptor is bound. The effects that we observe on the temperature dependence of the resonances suggest that the receptor stabilization is not only local to the binding interface but also more long-range. This effect is consistent with studies following histidine hydrogen–deuterium exchange kinetics,11 in which the rates of histidine hydrogen–deuterium exchange were slowed upon receptor binding, even for residues >40 Å from the binding interface.

The studies presented here provide an initial step toward following the conformational changes that occur in the anthrax toxin at low pH. On the basis of the experiments reported here, the feasibility of using 19F NMR to follow structural changes in PA is warranted. One important question we wish to address using this method is the order of events leading to the formation of a pore. It has been proposed38 that an initial step in the formation of the pore from the prepore state is the closure of the φ-clamp, a ring of phenylalanines (Phe427) located within the lumen of the pore that clamps down on its substrate (either edema factor or lethal factor) and is required for protein translocation.9 In initial experiments, we have used mutagenesis to replace this phenylalanine with a tryptophan and have labeled the protein with 5-FTrp, and we are able to observe this resonance (F-Trp427) in the prepore and pore states. Therefore, in the future, we should be able to follow this resonance during the process of pore formation in real time.22,39 In any case, 19F NMR opens the possibility of exploring structural changes in this protein at a residue-specific level.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AcOH

acetic acid

- CM

concentration of urea at the midpoint of the transition

- CMG2

capillary morphogenesis protein 2

- MTSL

S-(2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-2,5-dihydro-1H-pyrrol-3-yl)methyl methanesulfonothioate

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- PA

protective antigen

- TCEP

tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine

- 5-FTrp

5-fluorotryptophan

- 5-FTrpPA

83 kDa form of 5-FTrp-labeled PA

- vWA

von Willebrand factor A domain

- WT

wild-type.

Supporting Information Available

Representative liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry analysis of F-TrpPA and a table of labeling yields for different isolated peptide fragments. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Use of the University of Kansas Protein Structure Laboratory was supported by grants from National Center for Research Resources (5P20RR017708-10) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (8P20GM103420-10). Use of IMCA-CAT beamline 17-ID at the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the companies of the Industrial Macromolecular Crystallography Association through a contract with Hauptman-Woodward Medical Research Institute. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Bradley K. A.; Mogridge J.; Mourez M.; Collier R. J.; Young J. A. (2001) Identification of the cellular receptor for anthrax toxin. Nature 414, 225–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scobie H. M.; Rainey G. J.; Bradley K. A.; Young J. A. (2003) Human capillary morphogenesis protein 2 functions as an anthrax toxin receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 5170–5174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martchenko M.; Jeong S. Y.; Cohen S. N. (2010) Heterodimeric integrin complexes containing β1-integrin promote internalization and lethality of anthrax toxin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 15583–15588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauregard K. E.; Collier R. J.; Swanson J. A. (2000) Proteolytic activation of receptor-bound anthrax protective antigen on macrophages promotes its internalization. Cell. Microbiol. 2, 251–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacy D. B.; Wigelsworth D. J.; Melnyk R. A.; Harrison S. C.; Collier R. J. (2004) Structure of heptameric protective antigen bound to an anthrax toxin receptor: A role for receptor in pH-dependent pore formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 13147–13151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kintzer A. F.; Thoren K. L.; Sterling H. J.; Dong K. C.; Feld G. K.; Tang I. I.; Zhang T. T.; Williams E. R.; Berger J. M.; Krantz B. A. (2009) The protective antigen component of anthrax toxin forms functional octameric complexes. J. Mol. Biol. 392, 614–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayama H.; Wang J.; Tama F.; Chollet L.; Gogol E. P.; Collier R. J.; Fisher M. T. (2010) Three-dimensional structure of the anthrax toxin pore inserted into lipid nanodiscs and lipid vesicles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 3453–3457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassi S.; Collier R. J.; Finkelstein A. (2002) PA63 channel of anthrax toxin: An extended β-barrel. Biochemistry 41, 1445–1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krantz B. A.; Melnyk R. A.; Zhang S.; Juris S. J.; Lacy D. B.; Wu Z.; Finkelstein A.; Collier R. J. (2005) A phenylalanine clamp catalyzes protein translocation through the anthrax toxin pore. Science 309, 777–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petosa C.; Collier R. J.; Klimpel K. R.; Leppla S. H.; Liddington R. C. (1997) Crystal structure of the anthrax toxin protective antigen. Nature 385, 833–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajapaksha M.; Lovell S.; Janowiak B. E.; Andra K. K.; Battaile K. P.; Bann J. G. (2012) pH effects on binding between the anthrax protective antigen and the host cellular receptor CMG2. Protein Sci. 21, 1467–1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson E. L.; Huynh P. D.; Finkelstein A.; Collier R. J. (1998) Identification of residues lining the anthrax protective antigen channel. Biochemistry 37, 3941–3948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santelli E.; Bankston L. A.; Leppla S. H.; Liddington R. C. (2004) Crystal structure of a complex between anthrax toxin and its host cell receptor. Nature 430, 905–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scobie H. M.; Marlett J. M.; Rainey G. J.; Lacy D. B.; Collier R. J.; Young J. A. (2007) Anthrax toxin receptor 2 determinants that dictate the pH threshold of toxin pore formation. PLoS One 2, e329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilpa R. M.; Bayrhuber M.; Marlett J. M.; Riek R.; Young J. A. (2011) A receptor-based switch that regulates anthrax toxin pore formation. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen K. A.; Krantz B. A.; Melnyk R. A.; Collier R. J. (2005) Interaction of the 20 kDa and 63 kDa fragments of anthrax protective antigen: Kinetics and thermodynamics. Biochemistry 44, 1047–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frieden C. (2003) The kinetics of side chain stabilization during protein folding. Biochemistry 42, 12439–12446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frieden C.; Hoeltzli S. D.; Bann J. G. (2004) The preparation of 19F-labeled proteins for NMR studies. Methods Enzymol. 380, 400–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimalasena D. S.; Cramer J. C.; Janowiak B. E.; Juris S. J.; Melnyk R. A.; Anderson D. E.; Kirk K. L.; Collier R. J.; Bann J. G. (2007) Effect of 2-fluorohistidine labeling of the anthrax protective antigen on stability, pore formation, and translocation. Biochemistry 46, 14928–14936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajapaksha M.; Eichler J. F.; Hajduch J.; Anderson D. E.; Kirk K. L.; Bann J. G. (2009) Monitoring anthrax toxin receptor dissociation from the protective antigen by NMR. Protein Sci. 18, 17–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke J.; Fersht A. R. (1993) Engineered disulfide bonds as probes of the folding pathway of barnase: Increasing the stability of proteins against the rate of denaturation. Biochemistry 32, 4322–4329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bann J. G.; Pinkner J.; Hultgren S. J.; Frieden C. (2002) Real-time and equilibrium 19F-NMR studies reveal the role of domain-domain interactions in the folding of the chaperone PapD. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 709–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch W. (1988) Automatic indexing of rotation diffraction patterns. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 21, 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Evans P. R. (2011) An introduction to data reduction: Space-group determination, scaling and intensity statistics. Acta Crystallogr. D67, 282–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagin A.; Teplyakov A. (2010) Molecular replacement with MOLREP. Acta Crystallogr. D66, 22–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams P. D.; Afonine P. V.; Bunkoczi G.; Chen V. B.; Davis I. W.; Echols N.; Headd J. J.; Hung L. W.; Kapral G. J.; Grosse-Kunstleve R. W.; McCoy A. J.; Moriarty N. W.; Oeffner R.; Read R. J.; Richardson D. C.; Richardson J. S.; Terwilliger T. C.; Zwart P. H. (2010) PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D66, 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P.; Lohkamp B.; Scott W. G.; Cowtan K. (2010) Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Painter J.; Merritt E. A. (2006) Optimal description of a protein structure in terms of multiple groups undergoing TLS motion. Acta Crystallogr. D62, 439–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen V. B.; Arendall W. B. III; Headd J. J.; Keedy D. A.; Immormino R. M.; Kapral G. J.; Murray L. W.; Richardson J. S.; Richardson D. C. (2010) MolProbity: All-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D66, 12–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potterton L.; McNicholas S.; Krissinel E.; Gruber J.; Cowtan K.; Emsley P.; Murshudov G. N.; Cohen S.; Perrakis A.; Noble M. (2004) Developments in the CCP4 molecular-graphics project. Acta Crystallogr. D60, 2288–2294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minks C.; Huber R.; Moroder L.; Budisa N. (1999) Atomic mutations at the single tryptophan residue of human recombinant annexin V: Effects on structure, stability, and activity. Biochemistry 38, 10649–10659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeltzli S. D.; Frieden C. (1994) 19F NMR spectroscopy of [6-19F]tryptophan-labeled Escherichia coli dihydrofolate reductase: Equilibrium folding and ligand binding studies. Biochemistry 33, 5502–5509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajapaksha M.; Lovell S.; Janowiak B. E.; Andra K. K.; Battaile K. P.; Bann J. G. (2012) pH effects on binding between the anthrax protective antigen and the host cellular receptor CMG2. Protein Sci. 21, 1467–1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimalasena D. S.; Janowiak B. E.; Lovell S.; Miyagi M.; Sun J.; Zhou H.; Hajduch J.; Pooput C.; Kirk K. L.; Battaile K. P.; Bann J. G. (2010) Evidence that histidine protonation of receptor-bound anthrax protective antigen is a trigger for pore formation. Biochemistry 49, 6973–6983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourez M.; Yan M.; Lacy D. B.; Dillon L.; Bentsen L.; Marpoe A.; Maurin C.; Hotze E.; Wigelsworth D.; Pimental R. A.; Ballard J. D.; Collier R. J.; Tweten R. K. (2003) Mapping dominant-negative mutations of anthrax protective antigen by scanning mutagenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 13803–13808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang B.; Bushweller J. H.; Tamm L. K. (2006) Site-directed parallel spin-labeling and paramagnetic relaxation enhancement in structure determination of membrane proteins by solution NMR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 4389–4397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng W.; Luan B.; Lyle N.; Pappu R. V.; Raleigh D. P. (2013) The denatured state ensemble contains significant local and long-range structure under native conditions: Analysis of the N-terminal domain of ribosomal protein L9. Biochemistry 52, 2662–2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bann J. G. (2012) Anthrax toxin protective antigen: Insights into molecular switching from prepore to pore. Protein Sci. 21, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bann J. G.; Frieden C. (2004) Folding and domain-domain interactions of the chaperone PapD measured by 19F NMR. Biochemistry 43, 13775–13786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans P. (2006) Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta Crystallogr. D62, 72–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diederichs K.; Karplus P. A. (1997) Improved R-factors for diffraction data analysis in macromolecular crystallography. Nat. Struct. Biol. 4, 269–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss M. S. (2001) Global indicators of X-ray data quality. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 34, 130–135. [Google Scholar]

- Karplus P. A.; Diederichs K. (2012) Linking crystallographic model and data quality. Science 336, 1030–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans P. (2012) Biochemistry. Resolving some old problems in protein crystallography. Science 336, 986–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.