Abstract

Kinetics studies of dNTP analogues having pyrophosphate-mimicking β,γ-pCXYp leaving groups with variable X and Y substitution reveal striking differences in the chemical transition-state energy for DNA polymerase β that depend on all aspects of base-pairing configurations, including whether the incoming dNTP is a purine or pyrimidine and if base-pairings are right (T•A and G•C) or wrong (T•G and G•T). Brønsted plots of the catalytic rate constant (log(kpol)) versus pKa4 for the leaving group exhibit linear free energy relationships (LFERs) with negative slopes ranging from −0.6 to −2.0, consistent with chemical rate-determining transition-states in which the active-site adjusts to charge-stabilization demand during chemistry depending on base-pair configuration. The Brønsted slopes as well as the intercepts differ dramatically and provide the first direct evidence that dNTP base recognition by the enzyme–primer–template complex triggers a conformational change in the catalytic region of the active-site that significantly modifies the rate-determining chemical step.

The first chemical model to account for base substitution mutations was proposed by Watson and Crick (W–C), who suggested that the natural bases, in normal amino and keto forms, could occasionally become mispaired as disfavored imino and enol tautomers.1 In the ensuing 60 years, it has been shown, principally by X-ray crystallography, that the active-sites of DNA polymerases accommodate many types of mispaired structures, including wobble mispairs,2 ionized and protonated base pairs,3−5 Hoogsteen mispairs in syn-conformations,6,7 primer–template slipped mispairs,8,9 stacked bases,10 missing bases,11 bulky DNA adducts,12 and, most recently, an originally postulated C•A W–C disfavored tautomer.13 A mechanistic understanding of how different W–C and non-W–C structures are accommodated during DNA replication requires knowing the structure and properties of the transition state (TS) for the rate-determining step (RDS) in the DNA polymerase (pol) active-site.6,14−20 Little is known about pol TS structures apart from some evidence that the TS may be either a chemical step where O–P bond making and/or breaking is rate-determining or a conformational step taking place prior to or perhaps even after chemistry21 involving an essential rate-determining slow change in protein conformation occurring on the reaction pathway.

Among pols believed to have a chemical RDS, DNA polymerase β (pol β) is of particular importance.18,19,22−24 Pol β is a member of the X-family of DNA polymerases and plays a key role in base excision repair (BER), a process that removes simple base lesions from the genome.25 BER plays a role in the development of anticancer drug resistance.26 Additionally, it has been shown that pol β is overexpressed and/or found in variant forms in a significant fraction of malignant tumor cells.27−29

Polymerase fidelity studies typically use rapid-quench and stopped-flow fluorescence kinetics measurements with natural dNTP substrates to try to identify whether a conformational or chemical (kpol) step is rate-determining. For any DNA polymerase, the key question is the relationship of the mechanism to the achievement of fidelity (i.e., discrimination between right (R) and wrong (W) deoxynucleotide incorporation). A current view is that there are distinct check points accessed along the reaction pathway that regulate fidelity.21 In construction of conventional 2D free-energy reaction profiles for DNA polymerase, the insertions of R and W dNTPs follow the same reaction trajectories, each possibly having different barrier heights for dNTP binding, prechemistry conformational changes, and chemistry (reviewed in ref (21)). A tacit assumption in the profiles is that these fidelity check points are uncoupled from chemistry.21 If, for example, chemistry is the polymerase RDS for both R and W,18,19 then pre-RDS conformational changes, albeit different for R and W, would presumably not affect the transition-state energy. In this article, however, we provide evidence for a different concept, namely, dRTP- and dWTP-dependent active-site conformation coupling directly to chemistry.

If a pol has a chemical RDS and the critical chemistry involves P–O bond breaking (i.e., release of pyrophosphate (PPi)to complete incorporation of the incoming dNTP (as dNMP)), then can base-pairing/mispairing in the TS affect the overall TS energy, where the key step occurs distally in the triphosphate moiety of the bound nucleotide? What evidence could be adduced to support such a hypothesis, which might seem counterintuitive, if base-pair/mispair energy changes are postulated to occur earlier than the TS in checkpoints preceding chemistry? Here, we have addressed this question using chemical probes consisting of dNTP analogues having variable pyrophosphate-mimicking leaving groups and different bases (R and W) in both purine (G) and pyrimidine (T) forms.

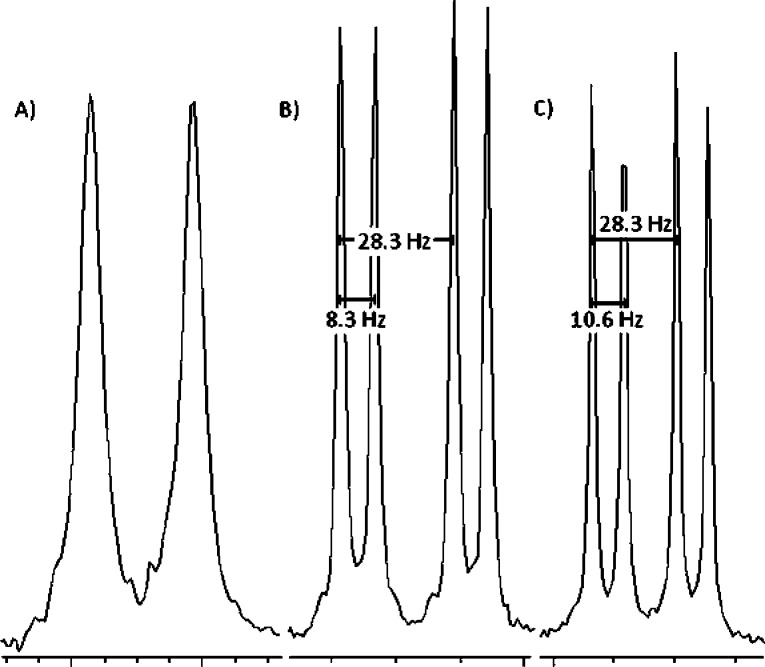

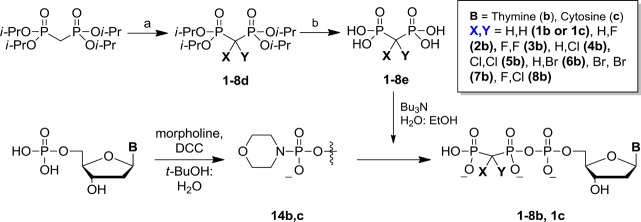

Previous experiments investigating the nature of the RDS for pol catalysis have usually compared incorporation of R and W dNTPs, where the PPi leaving group is the same for R and W. The rates typically differ significantly, but it is not clear whether this reflects a change of mechanism in terms of the role of P–O bond breaking. Recently, we elaborated a series of dNTP pol substrate analogues in which the β,γ-bridging O is replaced by CXY moieties that alter the stereoelectronic properties of the corresponding bisphosphonate (BP) leaving group14,16,18,19,30,31 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

dGTP analogues as probes for pol β in this study.

These β,γ-CXY-dNTP analogues, each having a different leaving group mimicking PPi, can be structurally tuned by varying the X and Y substituents to exhibit a large range of the BP leaving group conjugate acid pKa4 values. In the process of passing through a chemical RDS, a leaving-group effect can thereby be interrogated, with the derivatives acting as sensitive chemical probes of relative P–O charge stabilization in the TS.17−19 In a simplified view, as X and Y are made more electronegative, pKa4 decreases, meaning that the BP leaving-group aptitude increases because it is more stable as an anion. In this case, if chemistry is rate-determining and the P–O bond breaking is slow relative to P–O bond formation (attack of the terminal primer 3′-OH on Pα of the dNTP analogue), then a plot of the log of the catalytic rate constant (kpol) versus pKa4 (Brønsted plot32) is predicted to be linear (linear free energy relationship, LFER33) with a negative slope whose magnitude reflects the sensitivity of the TS to charge stabilization.18,19,34

Two important experimental points in applying such a probe are that (a) it is preferable to utilize homologous X and Y substituents, giving a wide range of pKa4, and (b) it is highly desirable to obtain the structure of the ground-state pol–DNA tertiary complexes of the analogues by X-ray crystallography to verify that within a given series of dNTP analogues each has the same or a highly similar configuration within the active-site of the enzyme.14−16 Both criteria are satisfied by our probes, in which X and Y in the CXY moiety are H, F, Cl, or Br16,18,19 as well as other useful substituents such as CH3 and N330 and for which a range of pol β ternary complex active-site structures have been determined.6,14,16,18−20,30 Furthermore, we have addressed the problem of CXY stereochemistry where X ≠ Y synthetically, analytically, kinetically, and structurally.14,16,17,31

Here, we employ these nucleotide probes to examine dNTP–template H-bonding and base-stacking effects on the TS of pol β using LFER analysis of pre-steady-state kpol data for a series of probes that includes new dTTP analogues (1b–8b), allowing comparison of the following base-pairings in terms of their relative effects on the dNTP leaving-group dependence of pol β kinetics: G•C, G•T, T•A, and T•G. We also provide detailed synthetic procedures and characterization data for the β,γ-CXY analogues of dTTP, where X and Y are H, F, Cl, and Br (1b–8b). These compounds were synthesized utilizing a generalized approach18,19 that was further extended to dCTP (X and Y = H, 1c; see Supporting Information for details).

Materials and Methods

Synthesis of Nucleoside 2′-Deoxy-5′-triphosphate β,γ-CXY Analogues

2′-Deoxy 5′-phosphomorpholidates were prepared from the acid forms of the commercially available dNMPs by DCC activation. Reactions proceeded with better than 90% conversion (as monitored by 31P NMR) and required minimal purification before advancing to the coupling step. To prepare dNTP analogues 1b–8b and 1c, the tri-n-butylammonium salts of the corresponding bisphosphonic acids 1e–8e were reacted with the appropriate nucleoside 5′-phosphoromorpholidate in anhydrous DMSO at rt. The reactions were conveniently monitored by analytical SAX HPLC with the starting material, dNMP side product, and desired triphosphate all being well-separated in the chromatogram (Supporting InformationFigure S4). After 48 h, a typical reaction was approximately 60% complete with <10% thymidine 5′-monophosphate formed. The desired products were purified by dual-pass HPLC with an SAX column eluted with a 0–0.5 N TEAB gradient followed by passage through a RP-C18 column eluted with 0.1 N TEAB 4% acetonitrile buffer. Final products 1b–8b and 1c were obtained on a milligram scale as triethylammonium salts in ∼20% yield, as determined by UV absorbance at λmax.49

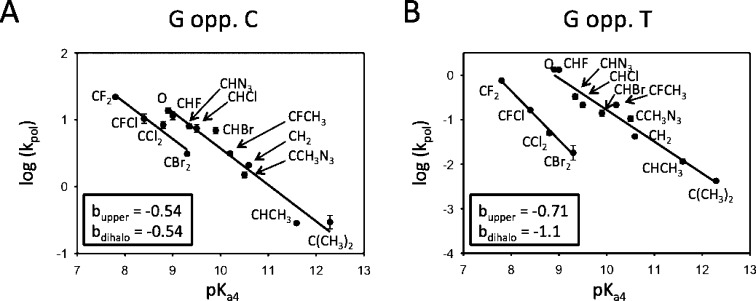

By analytical SAX HPLC analysis, the target compounds account for >99% of the detected UV absorbance (see the Supporting Information). The 31P NMR spectra are free of any significant monophosphate or other nucleotide side-product signals, and the 1H NMR spectra show a clean aromatic region, demonstrating the integrity of the nucleobase. As was the case for dGTP-β,γ-CXN3 analogues,30 under appropriate conditions, the 31P NMR resonances of dTTP β,γ-CXY diastereomers resulting from the chirality of the bisphosphonate moiety when X ≠ Y introduction of a pro-chiral bisphosphonate can be resolved. For example, Chelex treatment of 4b followed by addition of Na2CO3 to raise the pH to 10 narrows the line width of the resonances, revealing two doublets for Pα and two doublets of doublets for Pβ (Figure 2). As a result, the relative concentrations in individual stereoisomers can be monitored in solution. The δ and J assignments were unambiguously confirmed by comparing spectra acquired at different operating frequencies. For detailed experimental procedures and complete characterization of all analogues 1b–8b and 1c, see the Supporting Information.

Figure 2.

31P NMR spectra of the Pα4b resonances: (A) before Chelex treatment at neutral pH (162 MHz), (B) after Chelex treatment at pH > 10 (162 MHz), and (C) after Chelex treatment at pH > 10 at higher operating frequency (202 MHz).

Pre-Steady-State Kinetic Analyses

Radiolabeled 1 nt gapped DNA (100 nM) was incubated with 600 nM pol β in reaction buffer (2× mixture) for 3 min at 37 °C. Equal volumes of the DNA/pol β mixture and a 2× solution of β,γ-CXY-dNTP in reaction buffer at different concentrations were rapidly combined using a KinTek model RQF-3 quench-flow apparatus. After the appropriate reaction time, the reaction was quenched with 0.5 M EDTA (pH 8.0). For times longer than 20 s, reactions were initiated and quenched by manual mixing. Reaction products were separated by 20% denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (39 cm × 33 cm × 0.4 mm). Dehydrated gels were exposed to a phosphor screen and detected by phosphorescence emission. All reactions were carried out in triplicate. For DNA sequences, radiolabeling procedures, and buffer condition, see the Supporting Information.

For each set of reactions, the percentage of primer extended is plotted versus time, and the data for each concentration of analogue is fit to the first-order exponential y = a(1 – e–kt), where a is the maximum percent of primer extension and k is the observed rate constant. The observed rate constant (kobs) is then plotted versus the corresponding analogue concentration, and the data are fit to the rectangular hyperbola kobs = kpol[dNTP]/(Kd + [dNTP]) to give kpol and Kd parameters (Supporting InformationTables S1 and S2). An example of one replicate for the β,γ-CFCl-dTTP analogue is shown in Figure S1 of the Supporting Information. For each analogue, the average log of kpol for the three replicates is determined and averaged, and the standard error is calculated. The average log(kpol) with error bars is plotted versus the pKa4 for each analogue to give the LFER. The data are fit to the linear equation log(kpol) = a + b × pKa4, where a is the y-axis intercept and b is the slope.

Results

dTTP Analogue Synthesis

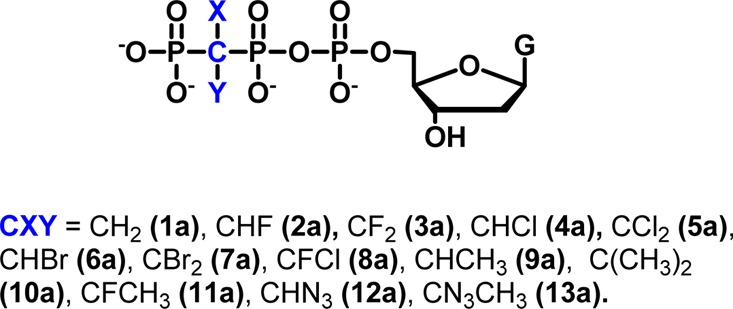

A few β,γ-CXY dTTP derivatives were previously reported using 1,1′-carbonyldiimidazole activation of thymidine 5′-monophosphate35 to prepare 2b, 3b, and 7b in yields of 11–47%.35,36 However, 2b and 3b were characterized solely by 31P NMR,36 and 7b was characterized by 1H and 31P NMR alone,35 with no other indication of purity. Our preferred synthetic approach, as presented here, is to use DCC-mediated morpholidate coupling37,38 of the commercially available 5′-dNMPs with the tributylammonium salt of the appropriate bisphosphonic acid 1e–8e14 (Figure 3), which furnishes the desired products in modest isolated yields but avoids the generation of difficult to remove side products. Dual-pass (SAX then RP-18) HPLC18,19 provided pure dTTP analogues 1b–8b in high purity free of detectable contaminating nucleotides, a sine qua non for reliable kinetics studies of polymerases.

Figure 3.

Synthesis of halogenated β,γ-dTTP and dCTP analogues. (a) 2d–3d: NaH, Selectfluor/THF/DMF, −42 °C; 5d: NaOCl, 0 °C; 4d (from 5d): Na2SO3/H2O/EtOH, 0 °C; 7d: Br2, NaOH/H2O, 0 °C; 6d: (from 7d): SnCl2/H2O/EtOH, 0 °C; 8d (from 4d): NaH, Selectfluor/THF/DMF, −42 °C; (b) 1e–4e and 8e: HCl reflux; 6e and 7e: HBr, reflux.

Brønsted Plots

DNA polymerase catalysis and fidelity studies typically measure the incorporation of R and W dNTPs, where the pyrophosphate leaving group is identical. Replacing the β,γ-bridging O in PPi by CXY16,18,19,31 results in leaving groups with markedly different stereoelectronic properties. By varying leaving group size and basicity (pKa4), we can observe the resulting effect on TS by determining the corresponding kpol rate constant in each case. The familiar Brønsted plot, log kpol = a + b × pKa4 (where a and b are the parameters for linear intercept and slope, respectively), is an example of an LFER that can be derived using modified Marcus theory32 to analyze bond-forming and bond-breaking processes in terms of changes in the TS charge stabilization caused principally by substrate modifications that modify the surrounding array of active-site interactions.33 We have used pre-steady-state rapid-quench kinetics to measure pol β-catalyzed incorporation for β,γ-dRTP and β,γ-dWTP analogues in a 1 nt gapped p/t DNA (Supporting InformationFigure S1 and Tables S1 and S2). The polymerase insertion rate constants (log kpol) were plotted versus the pKa4 value for the corresponding bisphosphonic acid leaving group for two classes of dNTP substrate analogues: β,γ-dGTPs (1a–13a) and β,γ-dTTPs (1b–8b).

Brønsted Plot for β,γ-CXY dGTP Analogues 1a–13a

We constructed Brønsted plots using 13 β,γ-CXY dNTP analogues (1a–13a), with the pKa4 values of the corresponding BP leaving groups 1e–13e spanning a range of 7.8 (CF2, 3e) to 12.3 (CMe2, 13e)19 and with pyrophosphate having a pKa4 of 8.9. For the rate constant to be sensitive to the pKa4 value of the leaving group, the bond forming (associative process) and bond breaking (dissociative process) about Pα must be concerted or dominated by P–O bond breaking.18,19,39 The additional negative charge generated by going from lower to higher pKa4 values at a fixed pH allows the analogues to serve as sensitive chemical probes for the dependence of P–O bond cleavage on electrostatic charge in the TS.17−19

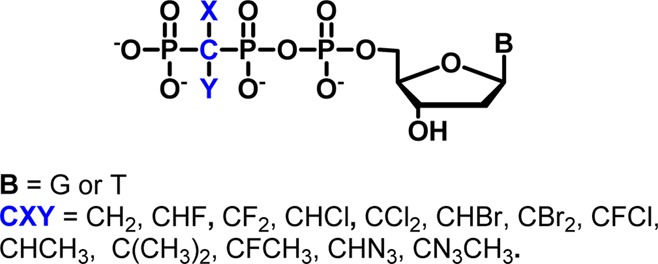

Brønsted plots depicting pol β-catalyzed R incorporations (G•C) and W incorporations (G•T) are observed to fit well to two separate lines (Figure 4), in accord with our previously published data for a subset of eight β,γ-CHX dGTP analogues.18,19

Figure 4.

Brønsted plots correlating log(kpol) and the leaving-group pKa4 P-CXY-P (1e–13e) for an expanded set of β,γ-CXY-dGTP analogues (1a–13a) comparing right (R) G•C (A) and wrong (W) G•T (B). For the correct pairing, the two lines are parallel (b = −0.54), whereas for incorrect pairing, the lines diverge significantly and exhibit nonsimilar slopes (blower = −0.71, bupper = −1.1).

The two LFER lines for R (G•C) are closely spaced and essentially parallel, having about the same negative slopes (Figure 4A, b ∼ −0.54). The upper line, which contains the parent dGTP, is composed of monohalo (2a, 6a, and 4a), azido (12a, and 13a), methylene (1a), and methyl (9a, 10a, and 11a) derivatives, whereas the lower line contains dihalo (3a, 5a, 7a, and 8a) substituents exclusively. The two LFER lines for W (G•T) exhibit markedly greater separation and steeper nonparallel slopes (Figure 4B, bupper ∼ −0.7, blower ∼ −1.1). The location of the CMe2 (10a) and CMeAz (13a) data points on the upper line suggests that segregation of the data into two separate LFER correlations cannot be explained by a unique steric effect based solely on size because these points would lie on the lower line between the CCl2 (5a) and CBr2 (7a) points, yet points 10a and 13a are clearly situated on the upper line for R and W.

The pronounced negative slopes of the linear correlations relating log(kpol) to pKa4 constitute convincing evidence that chemistry is the RDS (chem-RDS) along the reaction trajectories corresponding to the insertion of R and independently for the insertion of W. The observation of two correlations, with steeper negative slopes, indicates that the TS structures for these base-pairing series are more sensitive to stabilization of P–O bond breaking. The data are consistent with an altered active-site environment in the vicinity of the BP analogue leaving group, which is an environment that is less adept in stabilizing a net increase in negative charge generated as the leaving group departs when the bases are mismatched. Perhaps more flexible insertions that include dihalo G•C correct pairs and mono and dihalo G•T mispairs can occur when the pol β thumb and finger domains are in a more relaxed, partially open conformation.40−46

Brønsted Plot for β,γ-CXY dTTP Analogues 1b–8b

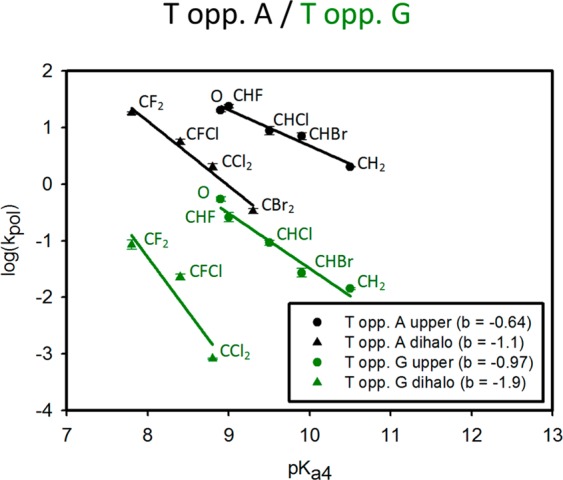

We have addressed whether dNTP substrate-p/t DNA flexibility in the pol β active-site conformation associated with a chemical TS might be detectible in the LFER by comparing Brønsted plots for R and W dT incorporations (Figure 5) with those for dG (Figure 4).

Figure 5.

Brønsted plots correlating log(kpol) and the leaving group pKa4 β,γ-pCXYp (1e–8e) for the β,γ-CXY-dTTP analogues (1b–8b) comparing right (R) T•A (black) and wrong (W) T•G (green). For the correct pairing, the slopes of the two lines have a greater separation than that of correct G•C and also diverge and exhibit nonsimilar slopes (bupper = −0.64, blower = −1.1); for incorrect pairing, the separation is even greater, and the lines diverge significantly and exhibit nonsimilar slopes (bupper = −0.97, blower = −1.9).

A combination of weaker base stacking and H-bonding interactions results in an increase in the flexibility of T•A base-pairs compared to G•C pairs.43,44,47 The Brønsted plots corresponding to incorporation of T opposite A (Figure 5, black lines) exhibit striking differences. There are now two well-separated R correlations in contrast to the plots for G opposite C (Figure 4A), where the upper and lower lines have nonparallel negative slopes (Figure 5, bupper ∼ −0.64, blower ∼ −1.1). The dihalo slopes for R (T•A) and W (G•T) are about the same (Figures 5 and 4B, respectively, b ∼ −1.1). Thus, for the dihalo derivatives (3b, 5b, 7b, and 8b), the chemical step (kpol) in forming W–C T•A pairs is comparable to forming non-W–C G•T mispairs. The difference between the negative slopes is significantly increased for the W lines corresponding to the misincorporation of T opposite G (Figure 5, green lines, bupper ∼ −0.97, blower ∼ −1.9). The pronounced differences in the Brønsted plots comparing R (T•A and G•C) and W (T•G and G•T) pairings suggest that the base mispairs result in a change in the active-site conformation to the detriment of the bonding interactions available in the vicinity of the triphosphate group of the nucleotide that promote catalysis by stabilizing developing charge on the leaving group in the TS.

Discussion

Although it is well-established that base-stacking and H-bonding interactions modulate R and W nucleotide incorporation rates,47,48 our results provide the first direct evidence that this involves significant stabilizing or destabilizing contributions to P–O bond breaking in the TS and thus provides the first evidence that active-site conformational changes resulting from differences in base-pairs and mispairs as well as the chemical structure of the bases (purine vs pyrimidine) can perturb the rate-determining chemical step.

We previously reported18,19 that LFER analysis of pol β kinetics using dGTP analogues (i.e., incoming purine nucleotide) interacting with a dC or dT in template DNA reveals a fidelity-dependent chemical RDS, suggesting that R and W interactions for the incoming dG analogues have different effects on the TS of the active-site. In this article, we examine leaving-group effects on turnovers for an incoming pyrimidine nucleotide analogue (β,γ-CXY-dTTP, 1b–8b). Here, H-bonding and stacking forces will be weaker, presumably resulting in a more flexible active-site ternary complex. The question then is whether this greater flexibility will be manifested in the TS (i.e., in a conformational change affecting the region of the active-site implicated in chemical catalysis and thus detectable by kpol changes). β,γ-CXY-dTTP analogues 1b–8b allow us to investigate this possibility directly. We find that for the dTTP analogues (i.e., incoming pyrimidine nucleotides) the different base-stacking and H-bonding interactions for R (to dA DNA template) and W (to dG DNA template) again affect the TS energy, but not in the same way. In contrast to the previous results for R paired G•C, the Brønsted plots for R paired T•A show that the dihalo series (3b, 5b, 7b, and 8b) have an altered negative slope and distinctly separated correlation line from the other probes. Once again, mismatched bases (T•G) result in large differences in both the slopes and line displacement.

The results demonstrate a fidelity-dependent kpol that also depends dramatically on the amount of base-stacking and base H-bonding energy available. In particular, the dihalo effect is small with G•C, with an R pairing providing the largest base-pairing energy among the possible base-pairs that we examined. With W pairing of G•T, the active-site complex appears to be less constrained, and a second reaction pathway is distinctly used by the dihalo probes. R pairing of T•A, although correct pairwise, provides less stabilizing interaction energy from pairing to the overall complex, resulting in a more flexible active-site complex that produces two distinct LFER correlations that are similar to the W mispairing of G•T. This trend is strongly enhanced in the corresponding W pairing of T•G, which is expected to possess the most flexible active-site in the series. With all analogues and base-pairings, a negative LFER correlation is observed, indicating that P–O bond breaking is implicated in the rate-determining step.

The TS for pol β is hypersensitive to charge stabilization for each mispair, as shown by a dramatic increase in the Brønsted slope (≤−1). Therefore, fidelity (R vs W) as well as the particular partner pair in base stability (G•C vs T•A) affect the active-site environment local to the dNTP leaving group in the TS for the rate-limiting step. Our data show how the Brønsted plots can be used as an exquisitely sensitive method to detect in detail how H-bonding and base-stacking determine kpol. Applying this analysis to other pols should provide a new and powerful method to evaluate and compare base-selection mechanisms taking place in the TS.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BER

base excision repair

- BP

bisphosphonate

- LFER

linear free energy relationship

- pol

DNA polymerase

- PPi

pyrophosphate

- RDS

rate-determining step

- TS

transition state

- W–C

Watson–Crick

Supporting Information Available

Additional kinetics details, including a representative data set, detailed synthetic procedures, and compound characterization data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

K.O. performed and analyzed the kinetics experiments; B.T.C., Y.W., E.F., and B.A.K. synthesized dNTP analogues; W.A.B. and S.H.W. provided DNA polymerase β, provided important suggestions for the experiments, and critiqued the manuscript; and C.E.M. and M.F.G. designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript.

This research was supported by research project nos. Z01-ES050158 and Z01-ES050159 to S.H.W. by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and was in association with National Institutes of Health grant nos. 1U19CA105010 and 1U19CA177547.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Watson J. D.; Crick F. H. (1953) The structure of DNA. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 18, 123–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S. J.; Beese L. S. (2004) Structures of mismatch replication errors observed in a DNA polymerase. Cell 116, 803–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebenek K.; Pedersen L. C.; Kunkel T. A. (2005) Replication infidelity via a mismatch with Watson-Crick geometry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 1862–1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowers L. C.; Eritja R.; Kaplan B.; Goodman M. F.; Fazakerly G. V. (1988) Equilibrium between a wobble and ionized base pair formed between fluorouracil and guanine in DNA as studied by proton and fluorine NMR. J. Biol. Chem. 263, 14794–14801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowers L. C.; Goodman M. F.; Eritja R.; Kaplan B.; Fazakerley G. V. (1989) Ionized and wobble base-pairing for bromouracil-guanine in equilibrium under physiological conditions. A nuclear magnetic resonance study on an oligonucleotide containing a bromouracil-guanine base-pair as a function of pH. J. Mol. Biol. 205, 437–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batra V. K.; Shock D. D.; Beard W. A.; McKenna C. E.; Wilson S. H. (2012) Binary complex crystal structure of DNA polymerase beta reveals multiple conformations of the templating 8-oxoguanine lesion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 113–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu G. W.; Ober M.; Carell T.; Beese L. S. (2004) Error-prone replication of oxidatively damaged DNA by a high-fidelity DNA polymerase. Nature 431, 217–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel T. A.; Bebenek K. (2000) DNA replication fidelity. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69, 497–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tippin B.; Kobayashi S.; Bertram J. G.; Goodman M. F. (2004) To slip or skip, visualizing frameshift mutation dynamics for error-prone DNA polymerases. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 45360–45368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batra V. K.; Beard W. A.; Shock D. D.; Pedersen L. C.; Wilson S. H. (2005) Nucleotide-induced DNA polymerase active site motions accommodating a mutagenic DNA intermediate. Structure 13, 1225–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuniasse P.; Sowers L. C.; Eritja R.; Kaplan B.; Goodman M. F.; Cognet J. A.; Le Bret M.; Guschlbauer W.; Fazakerley G. V. (1989) Abasic frameshift in DNA. Solution conformation determined by proton NMR and molecular mechanics calculations. Biochemistry 28, 2018–2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y.; Liu Z.; Ding S.; Lin C. H.; Cai Y.; Rodriguez F. A.; Sayer J. M.; Jerina D. M.; Amin S.; Broyde S.; Geacintov N. E. (2012) Nuclear magnetic resonance solution structure of an N(2)-guanine DNA adduct derived from the potent tumorigen dibenzo[a,l]pyrene: Intercalation from the minor groove with ruptured Watson-Crick base pairing. Biochemistry 51, 9751–9762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W.; Hellinga H. W.; Beese L. S. (2011) Structural evidence for the rare tautomer hypothesis of spontaneous mutagenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 17644–17648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batra V. K.; Pedersen L. C.; Beard W. A.; Wilson S. H.; Kashemirov B. A.; Upton T. G.; Goodman M. F.; McKenna C. E. (2010) Halogenated beta,gamma-methylene- and ethylidene-dGTP-DNA ternary complexes with DNA polymerase beta: Structural evidence for stereospecific binding of the fluoromethylene analogues. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 7617–7625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain B. T.; Batra V. K.; Beard W. A.; Kadina A. P.; Shock D. D.; Kashemirov B. A.; McKenna C. E.; Goodman M. F.; Wilson S. H. (2012) Stereospecific formation of a ternary complex of (S)-alpha,beta-fluoromethylene-dATP with DNA pol beta. ChemBioChem 13, 528–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna C. E.; Kashemirov B. A.; Upton T. G.; Batra V. K.; Goodman M. F.; Pedersen L. C.; Beard W. A.; Wilson S. H. (2007) (R)-Beta,gamma-fluoromethylene-dGTP-DNA ternary complex with DNA polymerase beta. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 15412–15413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oertell K.; Wu Y.; Zakharova V. M.; Kashemirov B. A.; Shock D. D.; Beard W. A.; Wilson S. H.; McKenna C. E.; Goodman M. F. (2012) Effect of beta,gamma-CHF- and beta,gamma-CHCl-dGTP halogen atom stereochemistry on the transition state of DNA polymerase beta. Biochemistry 51, 8491–8501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sucato C. A.; Upton T. G.; Kashemirov B. A.; Batra V. K.; Martinek V.; Xiang Y.; Beard W. A.; Pedersen L. C.; Wilson S. H.; McKenna C. E.; Florian J.; Warshel A.; Goodman M. F. (2007) Modifying the beta,gamma leaving-group bridging oxygen alters nucleotide incorporation efficiency, fidelity, and the catalytic mechanism of DNA polymerase beta. Biochemistry 46, 461–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sucato C. A.; Upton T. G.; Kashemirov B. A.; Osuna J.; Oertell K.; Beard W. A.; Wilson S. H.; Florian J.; Warshel A.; McKenna C. E.; Goodman M. F. (2008) DNA polymerase beta fidelity: Halomethylene-modified leaving groups in pre-steady-state kinetic analysis reveal differences at the chemical transition state. Biochemistry 47, 870–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upton T. G.; Kashemirov B. A.; McKenna C. E.; Goodman M. F.; Prakash G. K.; Kultyshev R.; Batra V. K.; Shock D. D.; Pedersen L. C.; Beard W. A.; Wilson S. H. (2009) Alpha,beta-difluoromethylene deoxynucleoside 5′-triphosphates: A convenient synthesis of useful probes for DNA polymerase beta structure and function. Org. Lett. 11, 1883–1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce C. M.; Benkovic S. J. (2004) DNA polymerase fidelity: Kinetics, structure, and checkpoints. Biochemistry 43, 14317–14324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakhtina M.; Roettger M. P.; Tsai M. D. (2009) Contribution of the reverse rate of the conformational step to polymerase beta fidelity. Biochemistry 48, 3197–3208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Tsai M. D. (2001) DNA polymerase beta: Pre-steady-state kinetic analyses of dATP alpha S stereoselectivity and alteration of the stereoselectivity by various metal ions and by site-directed mutagenesis. Biochemistry 40, 9014–9022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roettger M. P.; Bakhtina M.; Tsai M. D. (2008) Mismatched and matched dNTP incorporation by DNA polymerase beta proceed via analogous kinetic pathways. Biochemistry 47, 9718–9727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard W. A.; Wilson S. H. (2006) Structure and mechanism of DNA polymerase beta. Chem Rev 106, 361–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canitrot Y.; Frechet M.; Servant L.; Cazaux C.; Hoffmann J. S. (1999) Overexpression of DNA polymerase beta: A genomic instability enhancer process. FASEB J. 13, 1107–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang T.; Maitra M.; Starcevic D.; Li S. X.; Sweasy J. B. (2004) A DNA polymerase beta mutant from colon cancer cells induces mutations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 6074–6079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starcevic D.; Dalal S.; Sweasy J. B. (2004) Is there a link between DNA polymerase beta and cancer?. Cell Cycle 3, 998–1001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L.; Patel U.; Ghosh L.; Banerjee S. (1992) DNA polymerase beta mutations in human colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 52, 4824–4827. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain B. T.; Upton T. G.; Kashemirov B. A.; McKenna C. E. (2011) Alpha-azido bisphosphonates: Synthesis and nucleotide analogues. J. Org. Chem. 76, 5132–5136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y.; Zakharova V. M.; Kashemirov B. A.; Goodman M. F.; Batra V. K.; Wilson S. H.; McKenna C. E. (2012) Beta,gamma-CHF- and beta,gamma-CHCl-dGTP diastereomers: Synthesis, discrete 31P NMR signatures, and absolute configurations of new stereochemical probes for DNA polymerases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 8734–8737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun-Sand S.; Olsson M. H. M.; Warshel A. (2005) Computer modeling of enzyme catalysis and its relationship to concepts in physical organic chemistry. Adv. Phys. Org. Chem. 40, 201–245. [Google Scholar]

- Schweins T.; Geyer M.; Kalbitzer H. R.; Wittinghofer A.; Warshel A. (1996) Linear free energy relationships in the intrinsic and GTPase activating protein-stimulated guanosine 5′-triphosphate hydrolysis of p21ras. Biochemistry 35, 14225–14231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jencks W. P. (1987) Effects of solvation on nucleophilic reactivity in hydroxylic solvents: Decreasing reactivity with increasing basicity. Nucleophilicity 215, 155–167. [Google Scholar]

- Alexandrova L. A.; Skoblov A. Y.; Jasko M. V.; Victorova L. S.; Krayevsky A. A. (1998) 2′-Deoxynucleoside 5′-triphosphates modified at alpha-, beta- and gamma-phosphates as substrates for DNA polymerases. Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 778–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martynov B. I.; Shirokova E. A.; Jasko M. V.; Victorova L. S.; Krayevsky A. A. (1997) Effect of triphosphate modifications in 2′-deoxynucleoside 5′-triphosphates on their specificity towards various DNA polymerases. FEBS Lett. 410, 423–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffatt J. G.; Khorana H. G. (1961) Nucleoside polyphosphates: The synthesis and some reactions of nucleoside 5′-phosphoromorpholidates and related compounds. Improved methods for the preparation of nucleoside 5′-polyphosphates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 83, 649–658. [Google Scholar]

- Moffatt J. G. (1964) General synthesis of nucleoside 5′-triphosphates. Can. J. Chem. 42, 599–604. [Google Scholar]

- Lassila J. K.; Zalatan J. G.; Herschlag D. (2011) Biological phosphoryl-transfer reactions: Understanding mechanism and catalysis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 80, 669–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florian J.; Goodman M. F.; Warshel A. (2005) Computer simulations of protein functions: Searching for the molecular origin of the replication fidelity of DNA polymerases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 6819–6824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier H.; Sawaya M. R.; Kumar A.; Wilson S. H.; Kraut J. (1994) Structures of ternary complexes of rat DNA polymerase beta, a DNA template-primer, and ddCTP. Science 264, 1891–1903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier H.; Sawaya M. R.; Wolfle W.; Wilson S. H.; Kraut J. (1996) Crystal structures of human DNA polymerase beta complexed with DNA: Implications for catalytic mechanism, processivity, and fidelity. Biochemistry 35, 12742–12761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petruska J.; Goodman M. F. (1995) Enthalpy-entropy compensation in DNA melting thermodynamics. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 746–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petruska J.; Sowers L. C.; Goodman M. F. (1986) Comparison of nucleotide interactions in water, proteins, and vacuum: Model for DNA polymerase fidelity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 83, 1559–1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawaya M. R.; Pelletier H.; Kumar A.; Wilson S. H.; Kraut J. (1994) Crystal structure of rat DNA polymerase beta: Evidence for a common polymerase mechanism. Science 264, 1930–1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawaya M. R.; Prasad R.; Wilson S. H.; Kraut J.; Pelletier H. (1997) Crystal structures of human DNA polymerase beta complexed with gapped and nicked DNA: Evidence for an induced fit mechanism. Biochemistry 36, 11205–11215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner D. H. (1996) Thermodynamics of base pairing. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 6, 299–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kool E. T. (2001) Hydrogen bonding, base stacking, and steric effects in dna replication. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 30, 1–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson R. C., Elliott D. C., Elliott W. H., Jones K. M. (1986) Data for Biochemical Research, Clarendon Press, Oxford. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.