Abstract

The mechanisms of forward masking are not clearly understood. The temporal window model (TWM) proposes that masking occurs via a neural mechanism that integrates within a temporal window. The medial olivocochlear reflex (MOCR), a sound-evoked reflex that reduces cochlear amplifier gain, may also contribute to forward masking if the preceding sound reduces gain for the signal. Psychophysical evidence of gain reduction can be observed using a growth of masking (GOM) paradigm with an off-frequency forward masker and a precursor. The basilar membrane input/output (I/O) function is estimated from the GOM function, and the I/O function gain is reduced by the precursor. In this study, the effect of precursor duration on this gain reduction effect was examined for on- and off-frequency precursors. With on-frequency precursors, thresholds increased with increasing precursor duration, then decreased (rolled over) for longer durations. Thresholds with off-frequency precursors continued to increase with increasing precursor duration. These results are not consistent with solely neural masking, but may reflect gain reduction that selectively affects on-frequency stimuli. The TWM was modified to include history-dependent gain reduction to simulate the MOCR, called the temporal window model-gain reduction (TWM-GR). The TWM-GR predicted rollover and the differences with on- and off-frequency precursors whereas the TWM did not.

INTRODUCTION

Forward masking refers to the elevation (or worsening) of threshold for a signal when it follows a temporally non-overlapping sound (called the masker). The mechanisms responsible for forward masking in the auditory system are not fully known. This issue has been explored in a number of previous studies using analytical and computational models. In the temporal window model (TWM), forward masking is modeled by a processing stage that integrates the masker and signal within a temporal window (Oxenham and Moore, 1994; Plack and Oxenham, 1998; Oxenham, 2001). The TWM has also been used to account for the improvement in threshold with increasing signal duration (Oxenham, 2001) and the limitation in temporal acuity of the auditory system (Moore et al., 1988; Plack and Moore, 1990; Oxenham and Moore, 1994). The physiological processes underlying this integration, or the levels of the auditory system at which it occurs, are not known. It has been suggested, however, that the temporal window may characterize the persistence of activity of central neurons with long time constants (Oxenham, 2001; Oxenham and Bacon, 2004).

Neural adaptation has also been proposed as a mechanism of forward masking (Kidd and Feth, 1982). Neural adaptation refers to the decrease in a nerve fiber's response to a steady-state stimulus over the course of stimulation. Additionally, for a period of time following stimulus offset, there is a decrease in the fiber's spontaneous rate and response to subsequent stimuli (Smith, 1977). Thus, as a result of adaptation, a preceding stimulus (masker) can lead to a reduction in auditory nerve fiber response to a subsequent stimulus (signal). Prior studies have indicated that the magnitude of adaptation at the level of the auditory nerve may be insufficient to account for all of psychophysical forward masking (Harris and Dallos, 1979; Relkin and Turner, 1988). However, this account does not consider that adaptation in a population of auditory nerve fibers rather than a single fiber may contribute to psychophysical threshold shifts (Meddis and O'Mard, 2005), nor does it consider that adaptation at higher levels of the auditory pathway may also play a role (Oxenham, 2001). In a model by Dau et al. (1996a), the effects of adaptation have been simulated using a series of feedback loops with different time constants. In this model, after a peripheral processing stage, the inputs to each loop are fed back to form the divisor element, which determines the attenuation applied to subsequent inputs.

Reasonable predictions of psychophysical data have been achieved with both the TWM (Oxenham and Moore, 1994; Plack and Oxenham, 1998; Oxenham, 2001) and adaptation-loop model (Dau et al., 1996b). A few studies have directly compared the predictions of integration and adaptation processes. Oxenham (2001) showed that models of integration and adaptation were approximately equally effective in accounting for the effects of signal duration on threshold. However, Plack and Oxenham (1998) argued that their measurements of growth-of-masking with various masker-signal delays were not consistent with neural adaptation. Ewert et al. (2007) reported that the TWM and the adaptation-loop models were nearly equivalent in terms of predicting forward masking data with a noise masker. Thus, it remains unclear whether integration or adaptation contributes more as a mechanism of forward masking. It appears for the data modeled thus far that both mechanisms are not necessary, at least computationally, to account for psychophysical results.

The medial olivocochlear reflex (MOCR), which involves a neural feedback loop between cochlear nerve fibers and the medial olivary complex (Guinan, 2006), may be another mechanism involved in forward masking. The MOCR is evoked by sound and reduces the gain of the cochlear amplifier by inhibiting the mechanical amplification provided by outer hair cell electromotility (Cooper and Guinan, 2006). In the absence of MOCR stimulation, the cochlear amplifier provides gain to low-level sounds at or near the characteristic frequency (CF) of a region of the basilar membrane (on-frequency sounds) (Ruggero, 1992). Frequencies well below the characteristic frequency (off-frequency sounds), however, are not processed with cochlear amplifier gain. As a result, stimulation of the MOCR and consequent reduction in cochlear amplifier gain affects on-frequency stimuli but not off-frequency stimuli (Cooper and Guinan, 2006). Cooper and Guinan (2006) showed that at an 18-kHz CF place on the chinchilla basilar membrane, MOCR stimulation reduced the low-level response to an 18-kHz tone, but not to a 15-kHz tone which grew linearly.

The time course of the MOCR has been outlined in studies measuring sound-evoked suppression of otoacoustic emissions (OAEs). The MOCR has a fairly sluggish time course with an approximately 25-ms delay from the onset/offset of an eliciting stimulus to the onset/offset of gain reduction (James et al., 2005; Backus and Guinan, 2006). In addition to the onset and offset delays, MOCR effects build and decay gradually with a time constant of around 70 ms (Bassim et al., 2003; Backus and Guinan, 2006). Thus, in contrast to an integration process that limits the temporal acuity of the auditory system, the MOCR adapts the peripheral auditory system to incoming sound over a longer time course. Relative to a neural adaptation process, the MOCR has a more sluggish onset and affects cochlear gain. In the context of forward masking, it is possible that the masker may evoke the MOCR and reduce cochlear amplifier gain for the signal, provided that the signal onset occurs after the MOCR onset delay. As a result, the response of the auditory system to the signal would be reduced. If the effective signal-to-masker ratio is reduced, then signal threshold would be poorer.

Forward masking must reflect some form of the integration or neural adaptation processes mentioned earlier—what will be called “neural processes”—because forward masking occurs for masker durations/stimulus delays that would be too short for the MOCR to be evoked. What is a matter of debate is whether the MOCR-evoked gain reduction effects combine with the neural processes and contribute to forward masking. In previous studies from this laboratory, a forward masking paradigm has been used to isolate possible gain reduction effects when a precursor is added (Krull and Strickland, 2008; Jennings et al., 2009; Roverud and Strickland, 2010). In this paradigm, growth-of-masking (GOM) is measured with a short, off-frequency masker. The combined masker and signal durations fall within the MOCR delay and, thus, forward masking should reflect solely neural processes. The GOM function is fitted with an input/output (I/O) function to estimate gain, thought to correspond to cochlear amplifier gain (Jennings et al., 2009). When an on-frequency precursor tone is introduced, the lower leg of the GOM function shifts to the right (i.e., to higher input levels) and the estimated gain of the I/O function is reduced (Krull and Strickland, 2008). Additionally, Jennings et al. (2009) and Jennings and Strickland (2012a) demonstrated that a 100- or 160-ms, 40- to 60-dB, on-frequency precursor decreased threshold in the lower-frequency tail of a psychophysical tuning curve much more than the tip, resulting in broader PTCs.

The unique temporal and frequency characteristics of the MOCR may make it possible to isolate its role in forward masking. In Roverud and Strickland (2010), the time course of the forward masking gain reduction effect was examined by manipulating precursor duration and delay. In that study, in some listeners, gain reduction increased with increasing precursor duration up to approximately 50 ms, but then decreased or rolled over with a 100-ms precursor. This result was consistent with earlier findings from Krull and Strickland (2008), which showed that in some listeners, a 40-ms precursor resulted in a larger reduction in gain than a 160-ms precursor of the same level.

A previous study by Oxenham and Plack (2000) with a single forward masker showed evidence of rollover, as well. In some listeners, signal thresholds decreased (rolled over) when the duration of a noise forward masker was increased from 30 to 200 ms. Rollover only occurred when there was a 20-ms delay between the masker offset and signal onset, a condition that is similar to the conditions in Krull and Strickland (2008) and Roverud and Strickland (2010) where a 20-ms masker was present between the precursor and signal. The rollover in each of these studies was small (only a few dB in some subjects), and could possibly be due to random variability in thresholds. However, it could also be consistent with gain reduction by the MOCR. If the precursor is long enough, the later portions of the precursor occurring beyond the MOCR delay could be influenced by the gain reduction that the earlier portions elicited. Thus, with a sufficiently long duration, the on-frequency precursor representation would be reduced in the signal frequency channel, rendering it a less effective forward masker and gain reduction elicitor. If this is the case, signal thresholds with longer on-frequency precursors may decrease (improve) relative to thresholds with shorter precursors.

These previous studies showing rollover (Oxenham and Plack, 2000; Krull and Strickland, 2008; Roverud and Strickland, 2010) have all used maskers or precursors with on-frequency components. However, if rollover is a result of MOCR-induced gain reduction, a different effect may be seen with an off-frequency precursor. An off-frequency precursor of sufficient intensity could still elicit gain reduction at the signal frequency. Specifically, if the off-frequency precursor produces sufficient excitation in the signal frequency channel, it could elicit gain reduction there. What is relevant is whether this gain reduction elicited by the off-frequency precursor affects the stimulus representations within the signal frequency channel. Assuming the off-frequency precursor has no gain at the signal frequency and grows linearly, it would not be affected by the gain reduction in the signal frequency channel, regardless of its duration. This idea is supported by physiological studies. Stimulus frequencies far enough below CF can grow linearly, have no cochlear amplifier gain at CF and therefore not be influenced by MOCR elicitation at CF (see Fig. 2 in Cooper and Guinan, 2006). Thus, thresholds with an off-frequency precursor may continue to increase with increasing precursor duration and show no rollover. If forward masking is solely the result of neural mechanisms of masking (as represented by the TWM), rollover may be due to random variability in thresholds, and should be seen regardless of precursor frequency.

In this study, the effect of precursor duration for on- and off-frequency precursors was compared. This allowed us to test the hypothesis that the MOCR is another mechanism of forward masking and is responsible for the rollover effect. Instead of using precursor durations from 10 to 100 ms as was done with an on-frequency precursor in the Roverud and Strickland (2010) study, precursor durations from 10 to 150 ms in finer duration steps were used. Precursors were also presented at three different levels. Additionally, the TWM was modified to include a module simulating history-dependent gain variation by the MOCR. The data were fitted with the TWM, simulating only neural processes, and again with the TWM with gain reduction.

METHODS

Participants

Five listeners (age range 22–27; 4 female) with prior experience in psychoacoustic tasks participated in the study. All were within normal limits bilaterally on measures of acoustic immittance, distortion-product otoacoustic emissions, and pure-tone audiometry (thresholds ≤15 dB HL for octave frequencies from 250 to 8000 Hz). Except for S3, the first author, all listeners were compensated monetarily for their participation.

Stimuli

All stimulus conditions, with the exception of quiet threshold, consisted of a precursor, masker, and signal presented sequentially. There was no delay between the precursor, masker, and signal at the zero voltage points. The precursor and masker had 5-ms cos2 onset and offset ramps. The precursor was a 0.8-kHz (control), 2.4-kHz (off-frequency), or 4-kHz (on-frequency) sinusoid. The durations and levels of the precursors are described in the experiments below. The masker was a 2.4-kHz, 20-ms sinusoid. The signal was a 4-kHz, 6-ms sinusoid with 3-ms cos2 ramps. The basilar membrane response to the 2.4-kHz masker was assumed to be approximately linear at the place with a CF corresponding to the 4-kHz signal frequency. This assumption is supported by previous psychophysical studies with short maskers (Jennings and Strickland, 2012b; Yasin et al., 2013). It was also assumed that the masker produced little-to-no gain reduction for the signal because the total duration of the 20-ms masker and the 6-ms signal fell approximately within the 25-ms MOCR onset delay and the MOCR effect builds gradually. Thus, any significant MOCR effect elicited by the masker at the signal frequency place should not have occurred until after the signal offset. To restrict off-frequency listening, high-pass noise (cutoff frequency = 1.2 × signal frequency) was present in all conditions except for quiet signal threshold. The high-pass noise had 5-ms cos2 onset and offset ramps. It began 50 ms before precursor onset and ended 50 ms after signal offset. The spectrum level of the noise was 50 dB below the signal level on any given trial (Nelson et al., 2001).

The stimuli were generated digitally and passed through four separate D/A channels (TDT DA 3-4). The stimuli were then low-pass filtered at 10 kHz (TDT FT5 and TDT FT6-2), adjusted with programmable attenuators (TDT PA4), mixed together (TDT SM3), and delivered through a headphone buffer (TDT HB6). The stimuli were presented to each listener's right ear through an ER-2 insert earphone, which has a flat frequency response from 250 to 8000 Hz.

Growth-of-masking (GOM) experiment

GOM data were collected in order to determine the fixed masker level to be used in the precursor duration experiment and because the I/O function estimates from the fitted GOM functions were used in the modeling section (discussed later). GOM functions were measured with the masker and a 40-dB SPL, 100-ms control (0.8-kHz) precursor. The control precursor was used to maintain similar temporal characteristics across experimental conditions without producing additional masking or eliciting gain reduction. Additionally, this precursor served as a control for attention-related or central cuing effects (Jennings et al., 2009). Using a similar stimulus paradigm, Jennings et al. (2009) demonstrated that thresholds with a 160-ms control precursor and masker were comparable to thresholds with the masker alone, while Roverud and Strickland (2010) demonstrated that thresholds did not vary with the duration of this 0.8-kHz precursor. In the present study, to further demonstrate that the control precursor does not produce masking, for S3 signal threshold was measured in the presence of the control precursor followed by a 20-ms delay in place of the masker. Additionally for S3, signal threshold was measured in the presence of a forward masker without the control precursor.

GOM functions were used to estimate the I/O function at the signal frequency. Oxenham and Plack (1997) showed that the I/O function could be derived by comparing GOM with a short, off-frequency masker to GOM with an on-frequency masker. With no masker-signal delay, however, the on-frequency GOM function has a slope of one (Oxenham and Plack, 2000) which means the I/O function can be estimated directly from the off-frequency GOM function alone (Oxenham and Bacon, 2004). Therefore, in the present study, only off-frequency GOM was measured.

For each participant, a masker level was selected based on the GOM function results and fixed for the precursor duration experiment. Where possible, the masker level was selected to produce a signal threshold as high on the lower leg of the GOM function as possible—that is, below the breakpoint estimate from the fitted I/O function (fitting procedure described in results section below). This was done to replicate the conditions in Roverud and Strickland (2010) that aimed to more efficiently estimate the change in gain caused by the precursor. Previous studies have shown that an on-frequency precursor reduces the estimated gain of the fitted I/O function (Krull and Strickland, 2008; Jennings et al., 2009). In Roverud and Strickland (2010), the difference between gain estimated from the function with the control precursor and the gain estimated from the function with the on-frequency precursor was termed the temporal effect. That study demonstrated that, if the masker level was fixed on the lower leg of the GOM function, the difference between masked threshold with an on-frequency precursor and masked threshold with a control precursor closely approximated the size of the temporal effect. In other words, the masked threshold shift with the on-frequency precursor closely approximated the estimated change in gain, making it unnecessary to measure a full GOM function for each precursor condition.

Precursor duration experiment

The effect of precursor duration on masked signal threshold with the fixed masker was compared for on- (4-kHz) and off-frequency (2.4-kHz) precursors. The durations of these precursors were 10, 20, 50, 80, 100, 120, and 150 ms. For both on- and off-frequency precursors, three levels were used. The on-frequency precursors were 40, 50, and 60 dB SPL. These levels were based on the precursor levels used in Roverud and Strickland (2010) and Krull and Strickland (2008) (40- and 60-dB SPL, respectively), where rollover was observed. The off-frequency precursors in the current study were 85, 90, and 95 dB SPL. It was an aim in this study for the on- and off-frequency precursor thresholds to match as closely as possible for at least one duration to rule out the possibility that differences with duration between the frequencies were due to unequal effectiveness of the precursors. Preliminary data collected with S3 showed that these off-frequency precursor levels produced equal thresholds to those with the on-frequency precursors for at least one out of the seven precursor durations tested. An 80 dB SPL precursor also tested for S3 (not shown) was found to not be effective enough to produce a matched threshold at any duration to the on-frequency precursors.

Procedures

Listeners were seated in front of a computer screen in a double-walled, sound-attenuating booth. Each listener's right ear was tested. Thresholds were measured using a three-alternative forced-choice procedure. The three intervals were marked by numbers flashed on the computer screen and were separated by 500 ms of silence. One of the three intervals contained the signal, and listeners selected this interval via a keystroke. Listeners were then provided with visual feedback indicating whether the response was correct or incorrect.

In the GOM experiment, for some blocks the masker was fixed (signal varied), and for other blocks the signal was fixed (masker varied) to find threshold. This was done to better define the GOM function. In the precursor duration experiment, the masker was fixed and the signal varied. During masker-vary tracking, masker level was decreased following an incorrect response and increased following two consecutive correct responses. During signal-vary tracking, signal level was increased following an incorrect response and decreased following two consecutive correct responses. These tracking rules converge on 70.7% correct (Levitt, 1971). Levels were increased or decreased with a step size of 5 dB until there were 2 reversals, after which step size was reduced to 2 dB. The run was completed after 50 presentations, and threshold was the average of the last even number of reversals at the smaller step size. Between two and six (and in most cases four) thresholds were averaged to give the final threshold for each condition. Any run with a standard deviation greater than 5 dB was discarded and that run was repeated.

There were no formal training sessions in this study, as each listener had participated in prior similar psychoacoustic tasks in this laboratory. In a few cases, initial thresholds in the first session differed from thresholds collected in later sessions. Initial thresholds that differed by 5 dB or more from the average of subsequent thresholds were discarded, and that condition was rerun. In the precursor duration experiment, for a particular precursor level and frequency, thresholds for all durations (10–150 ms) were collected within an experimental session. Precursor duration thresholds were collected in ascending order (increasing duration) in one session and in descending order (decreasing duration) in a separate session to control for order effects. There was no apparent variation in thresholds based on order of collection.

RESULTS

GOM experiment

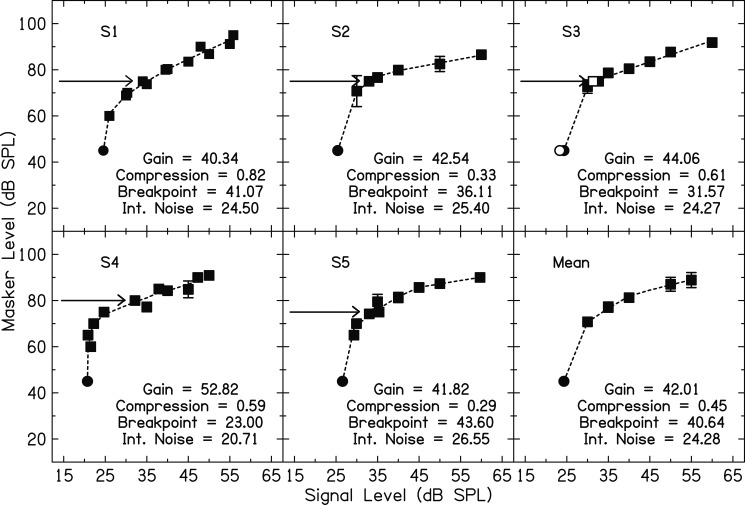

Each participant's GOM function is shown in Fig. 1. In the panel for S3, the open circle shows signal threshold with the control precursor followed by a 20-ms delay. This threshold is within 1 dB of signal threshold in quiet. The open square shows threshold with the masker and no control precursor. It is also within approximately 1 dB of threshold with the control precursor and masker. For all listeners, filled squares in Fig. 1 show signal thresholds with the masker and control precursor. Masker thresholds for the range of fixed signal levels used were averaged across participants, and the resulting averaged GOM function is shown in the bottom right panel of Fig. 1. Each GOM function, including quiet threshold, was fitted with a piecewise linear function described by Yasin and Plack (2003). The equations for this piecewise function are

| (1) |

| (2) |

where Lin is input signal level, Lout is masker level, G is gain, B is a breakpoint, and c is the slope of the compression above B. Jennings and Strickland (2010) modified these equations to include an internal noise parameter, α, to represent low-level physiological noise. The intensity level of α is subtracted from the intensity level of Lin and B as they are entered into Eqs. 1, 2. The parameter estimates of the fits are presented within Fig. 1. In previous studies, a second breakpoint, above which the function grows linearly, has been set at 100 dB (Jennings et al., 2009; Roverud and Strickland, 2010). However, because there were no levels greater than 95 dB SPL in this study, no specification for a second breakpoint was included. The masker level fixed for the precursor duration experiment is indicated in each panel of Fig. 1 with an arrow. For all participants except S4, the masker level chosen produced a signal threshold at or below the breakpoint estimate and, therefore, at or below compression. For S4, the breakpoint estimate was near to the estimate of internal noise and the masker level chosen was in the region of compression.

Figure 1.

Growth-of-masking thresholds with the control precursor and masker (filled squares) for each subject are shown in each panel. Averaged data are shown in the bottom-right panel. The filled circle represents quiet threshold plotted at an arbitrary masker level of 45 dB SPL. In the panel for S3, the open circle shows threshold with a control precursor and a 20-ms delay. The open square shows threshold with just the masker and no control precursor. The masker level (and corresponding signal threshold) fixed in Expt 2 for each subject is indicated by an arrow. The dashed lines show the I/O function fits to the data, and the parameter estimates of these fits are shown within each panel.

Precursor duration experiment

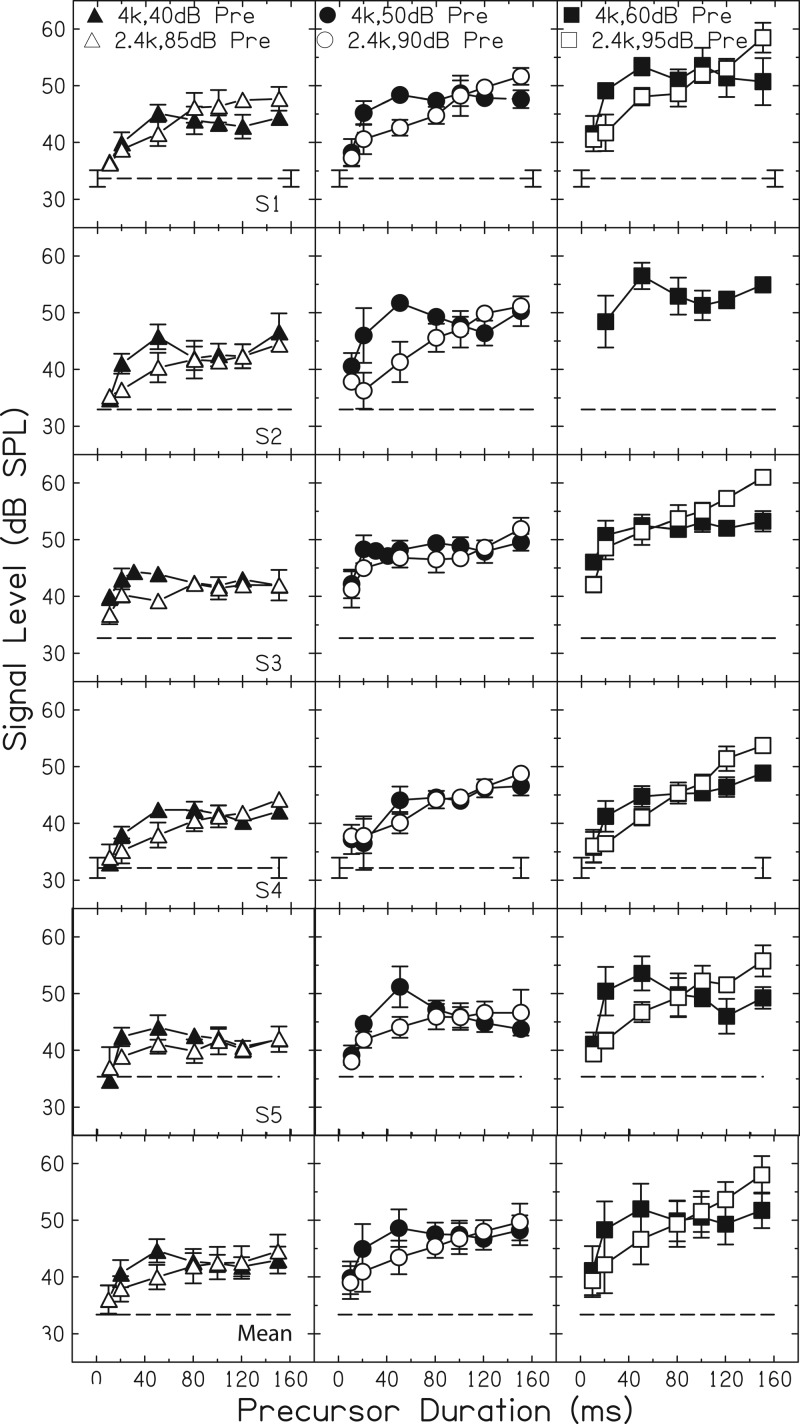

With an on-frequency precursor, thresholds increased with increasing precursor duration up to 50 ms (filled symbols in each panel, Fig. 2). In most cases, beyond 50 ms, thresholds with an on-frequency precursor decreased (rolled over) with further increases in precursor duration (i.e., S1 at 40 and 60 dB; S2 at 40, 50, and 60 dB; S3 at 40 dB; S4 at 40 dB; S5 at 40, 50 and 60 dB). In some cases displaying rollover, thresholds at 150 ms increased (e.g., S2 at all three precursor levels). However, in other cases, on-frequency precursor thresholds reached a plateau beyond 50 ms (e.g., S3 with 50- and 60-dB precursors). The nonmonotonic rollover effect, when present, occurred consistently at the same precursor duration for each listener. For example, in S2's data, thresholds rolled over beyond the 50-ms precursor duration and increased with a 150-ms precursor for all three precursor levels. The uniformity of this effect suggests that it was not due to random threshold variability. The averaged results (last row, Fig. 2) also show a small amount of rollover for the on-frequency precursors at each level.

Figure 2.

Signal threshold as a function of precursor duration. Closed symbols are thresholds with an on-frequency precursor and fixed masker and open symbols are thresholds with an off-frequency precursor and fixed masker. Each row shows data for a different participant (indicated within the first panel of each row). Each column shows data for different precursor levels (indicated at the top of each column). For comparison, the dashed line is the threshold with the fixed masker and control precursor.

Threshold trends with an off-frequency precursor were different from threshold trends with an on-frequency precursor. With the off-frequency precursor (open symbols, Fig, 2), thresholds generally increased with increasing precursor duration for all listeners at all precursor levels. This is also apparent in the averaged data in Fig. 2. There were essentially no nonmonotonic threshold trends with increasing off-frequency precursor duration.

Within each panel of Fig. 2 it is apparent that, although on- and off-frequency precursors resulted in equal thresholds at some durations, thresholds diverged at other durations. This was the case even for participants who showed slight to no rollover, although the apparent difference between on- and off-frequency precursors was largest for subjects with more extreme rollover effects. A repeated-measures mixed-model analysis of variance was performed to evaluate effects of precursor frequency, level (embedded within frequency), and duration on the dependent variable, threshold. Subjects served as a random effect in the model. The main effects were highly significant: precursor frequency, F(1, 717) = 22.66, p < 0.0001; level, F(4, 717) = 331.02, p < 0.0001; and duration, F(6, 717) = 226.08, p < 0.0001. All two-way interactions were also significant: frequency × duration, F(6, 717) = 27.19, p < 0.0001; level × duration, F(24, 717) = 5.75, p < 0.0001; subject × frequency, F(4, 717) = 5.25, p = 0.0004; and subject × duration, F(24, 717) = 6.43, p < 0.0001. Finally, a three-way interaction of subject × frequency × duration was not significant, F(24, 717) = 1.14, p = 0.295. The significant interaction of precursor frequency and duration indicates that the effect of duration differs for the two precursor frequencies. This finding is consistent with the gain reduction hypothesis stated earlier, which assumed gain reduction would affect on-frequency but not off-frequency stimuli and would lead to different precursor duration trends for the two frequencies. Tukey HSD post hoc tests were performed for all significant factors and interactions. Relevant to the hypothesis stated in the introduction, pairwise comparisons for the frequency × duration interaction revealed that the on-frequency, 50-ms precursor threshold (collapsed across level and subject) was statistically significantly different (p < 0.05) from on-frequency thresholds for 10-, 20-, 80-, 100-, and 120-ms precursors, but not from the 150-ms on-frequency precursor (p = 0.9485). This result is consistent with the qualitative description that on-frequency precursor results peaked at 50 ms, rolled over, then increased at 150 ms. In contrast, threshold for the off-frequency 50-ms precursor (collapsed across level and subject) was statistically significantly different from off-frequency thresholds for all other precursor durations (p < 0.05). Additionally, post hoc comparisons for the frequency × duration interaction showed that on-frequency and off-frequency precursor thresholds at like durations were statistically significantly different (p < 0.0001) at 20, 50, 120, and 150 ms, but not at 10, 80, and 100 ms. This result supports the statement that on- and off-frequency precursor thresholds were matched at some durations, but deviated at other durations.

MODELING

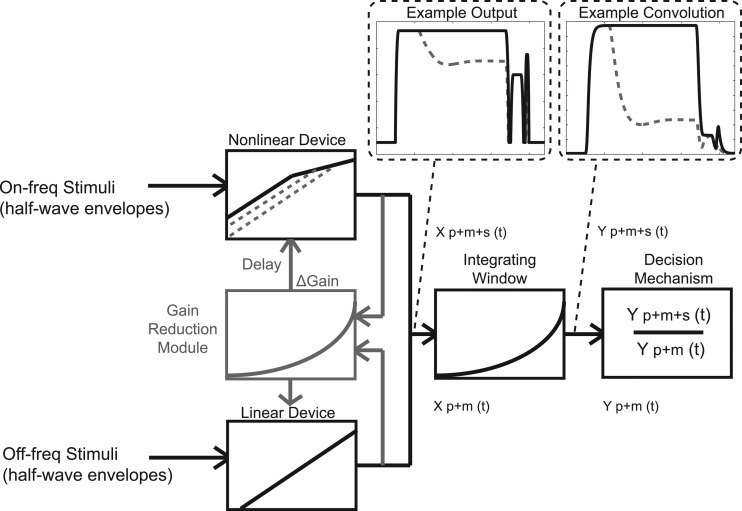

Two models were used in order to obtain quantitative predictions of the data and to gain insight into the potential peripheral auditory mechanisms underlying the results. The temporal window model (TWM) was constructed based on the descriptions from Oxenham and Moore (1994) and Oxenham (2001) using matlab (MathWorks, Natick, MA) software. In a separate version, a module of history-dependent gain variation was added to the TWM to incorporate the MOCR time course. The TWM with this additional gain reduction module is called the TWM-GR. A schematic of these two models is shown in Fig. 3. The solid black portions represent the TWM, and the gray portions represent the additional gain reduction module. The gray and black portions together represent the TWM-GR.

Figure 3.

A schematic of the models used. The TWM is shown as the black lines. The gain reduction module is represented by the gray lines. The TWM-GR is the combination of the gray and black lines. The “Example Output” dashed box shows an example condition processed through the model. The stimuli in this example are a 150-ms, 50-dB SPL on-frequency precursor followed by a 75-dB SPL masker and signal. The solid black line shows the stimuli processed with the TWM, and the dashed gray line shows the stimuli when processed by the TWM-GR. The “Example Convolution” box shows the stimuli after convolution with the integrating window [Eq. 3].

The TWM in its standard form is made up of four modules (Oxenham and Moore, 1994; Oxenham, 2001). The first is peripheral filtering to account for ringing in filters. However, because effects of ringing in filters do not play much role at frequencies above 1 kHz, a filtering module is not always included (Oxenham and Moore, 1994). The second is a compressive nonlinearity module representing the basilar membrane I/O function, followed by half-wave rectification. Third is a sliding integrating window. The window for forward masking is described by

| (3) |

where W is the weighting function describing window shape, t is time relative to the window center (negative in the case of forward masking), T1 and T2 are time constants for forward masking, and w is a weighting factor of the relative contribution of T1 and T2. The fourth module is a decision mechanism where the time yielding the maximum ratio of masker-plus-signal to masker-alone outputs (SNR) is determined. A criterion SNR is assumed to remain constant across conditions (Oxenham, 2001).

In the TWM used for this study, there was a simplified filtering module. Stimuli were classified as either on- or off-frequency relative to the 4-kHz signal, and were represented as ramped, half-wave rectified amplitude envelopes. These envelopes were expressed in dB SPL in order to determine output levels from I/O functions on a sample-by-sample basis. The sampling rate was 10 kHz. Output levels of off-frequency stimuli were determined from a linear function (output = input – I), where the intercept term, I, was a free parameter. This assumption of linear representation of off-frequency stimuli at a particular characteristic frequency is supported by physiological data (Ruggero, 1992). Output levels of on-frequency stimuli were determined by inputting level at each sample point, t, as Lin in Eqs. 1, 2 with no internal noise (no α). G, c, and B parameters for these equations remained fixed at the estimates shown in Fig. 1 for each participant. Internal noise was present as a limit in the output minimum of all stimuli. This minimum was obtained by inputting the internal noise estimate for each participant (see Fig. 1) as Lin in Eqs. 1, 2 without an internal noise component. The on- and off-frequency stimuli (precursor and masker) were concatenated with the signal and again without the signal, converted to amplitude units, squared, and then convolved with the forward masking window described by Eq. 3. The convolved outputs with the signal and without the signal were compared to yield signal-to-noise ratios. The point in time with the maximum signal-to-noise ratio defined the SNR for that condition. For each stimulus condition (each precursor frequency, level, and duration), each stage of the model was repeated for a range of signal levels to determine the relationship between signal level and SNR at the output of the temporal window. Threshold predictions were obtained by minimizing RMS error on I, T1, T2, w, and SNR, and all data for a given subject were fitted at once. Initially, the upper limit of T2 in the model was set at 50 ms to contain the T2 estimates obtained in Oxenham and Moore (1994) and Oxenham (2001), 16.6 and 46 ms, respectively. However, this upper limit was reached for four out of the six data sets. The T2 upper limit was systematically extended to determine the reduction in RMS error. For S1 and S4, extending the upper limit beyond 10 000 ms (far outside the range of previously reported T2 values) did not result in a fully minimized model fit, but led to reductions in RMS errors of less than 0.001. The fits with the upper limit of T2 in the model set at 10 000 ms are shown as solid, black lines in the first two columns of Fig. 4. The parameter estimates and RMS errors for each subject's fit with the TWM are presented in the top half of Table TABLE I.. For comments regarding the possible basis for these long T2 estimates, see Sec. 5B.

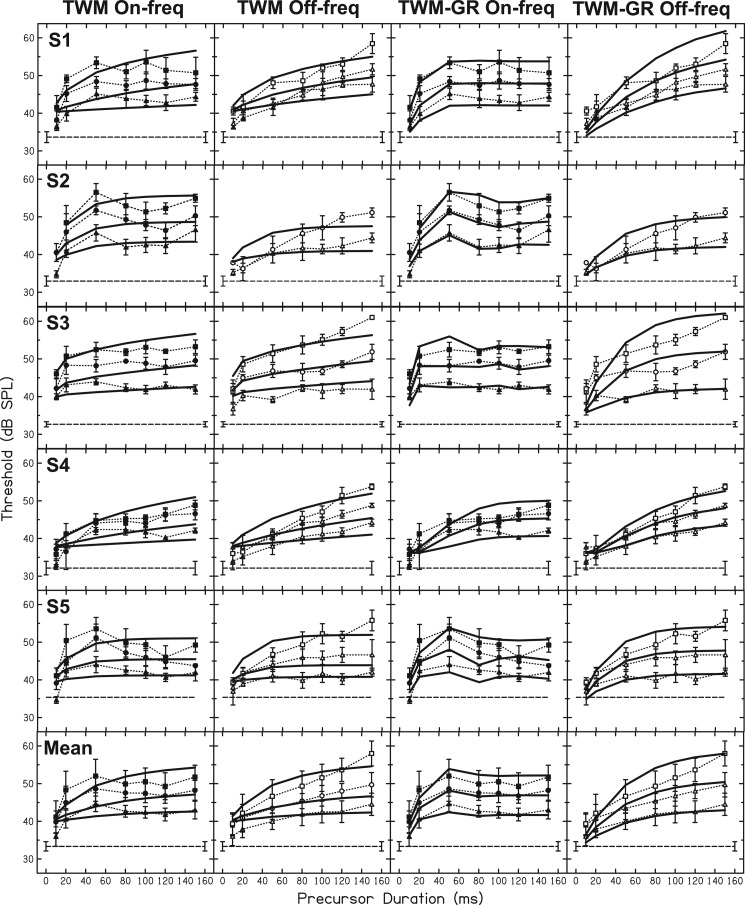

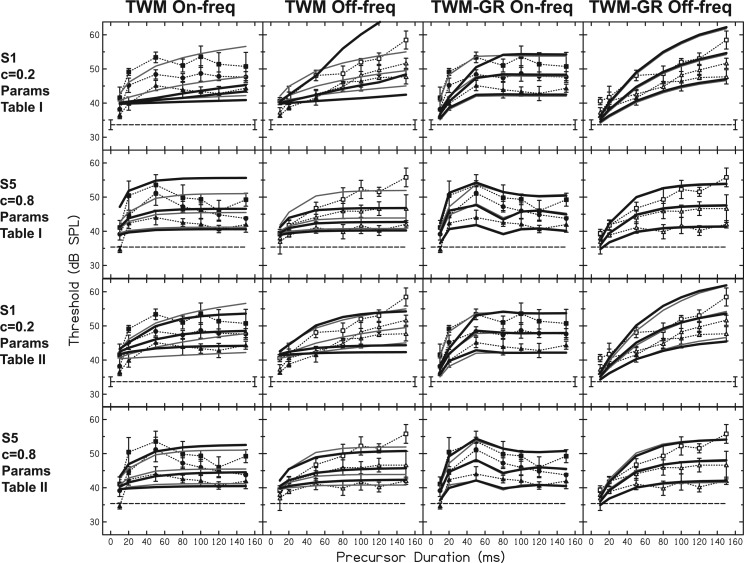

Figure 4.

TWM fits (first and second columns) and TWM-GR fits (third and fourth columns) are shown as solid lines for all data. On-frequency precursor data are plotted as filled symbols and dotted lines in the first column and again in the third column. Off-frequency precursor data are plotted as open symbols and dotted lines in the second and fourth columns. The different symbols represent precursor level (see Fig. 2). As in Fig. 2, the horizontal dashed line in each panel is threshold with the fixed masker and control precursor.

TABLE I.

Parameter estimates and RMS errors from the fits with the TWM and TWM-GR. MaxGR in the bottom half of the table was not a parameter, but was determined from each subject's data.

| TWM | T1 (ms) | T2 (ms) | w | I | SNR | RMS error | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 1.46 | 10 000 a | 1.68 × 10−4 | −0.52 | 14.26 | 2.66 | |

| S2 | 0.30 | 29.63 | 1.55 × 10−3 | 7.26 | 10.50 | 2.58 | |

| S3 | 6.91 | 7000 | 2.07 × 10−3 | 2.18 | 6.41 | 2.04 | |

| S4 | 2.16 | 10 000 a | 4.51 × 10−4 | −3.24 | 8.47 | 2.56 | |

| S5 | 3.93 | 22.55 | 2.12 × 10−2 | 4.21 | 8.93 | 2.49 | |

| Mean | 0.06 | 79.07 | 3.52 × 10−5 | 3.47 | 15.18 | 2.22 | |

| TWM-GR | T1 (ms) | τdel (ms) | τwin (ms) | MaxGR (data) | I | SNR | RMS error |

| S1 | 4.03 | 15 | 75.95 | 28.42 | 11.02 | 5.97 | 2.64 |

| S2 | 6.47 | 18 | 45.41 | 23.54 | 12.05 | 5.17 | 1.74 |

| S3 | 0.001 | 15 | 36.30 | 28.33 | 12.56 | 9.87 | 2.54 |

| S4 | 2.88 | 15 | 70.34 | 21.57 | −1.91 | 6.95 | 1.84 |

| S5 | 0.006 | 21 | 28.10 | 20.40 | 10.31 | 7.51 | 1.90 |

| Mean | 0.002 | 15 | 45.89 | 24.63 | 12.30 | 9.35 | 1.95 |

Estimate reached upper limit in the model.

In the TWM-GR, rather than determining outputs with a fixed I/O function, the I/O function was recalculated with each sample. Gadapt and Badapt, calculated in Eqs. 4, 5, and 6 below at each sample, t, replaced G and B in Eqs. 1, 2. These equations, modified from Jennings and Strickland (2010) to include a temporal component, are

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

where G, B, and c are the original gain, breakpoint, and compression estimates shown in Fig. 1, t is time, τdel is MOCR delay, and ΔG is the output of the gain reduction module processing described below. According to Backus and Guinan (2006), the MOCR delay may range from 15 to 40 ms in humans. Thus, τdel in the TWM-GR was a constrained parameter (allowed to vary between 15 and 40 ms). Off-frequency stimuli were still processed through a linear function (output = input – I). However, because there is no gain in this function, ΔG has no influence on off-frequency stimuli. As in the TWM, the estimate of internal noise was used to limit the output minimum of all stimuli.

The gain reduction module in the TWM-GR consisted of a set of equations that take into account both the level and duration of the stimulus output with each additional sample to determine the amount of gain reduction (or ΔG) to apply in Eq. 5. The maximum possible gain reduction (called MaxGR) was a fixed value determined from each participant's data by subtracting the control precursor threshold (dashed line in Fig. 2) from the maximum signal threshold in the precursor duration experiment. As mentioned earlier, the difference between the precursor threshold and the control precursor threshold was assumed to reflect the amount of gain reduction. In almost all cases, the maximum precursor threshold was obtained with a 150-ms, 95 dB SPL off-frequency precursor (see Fig. 2). In the gain reduction module of the TWM-GR, this condition was used as a referent for a stimulus capable of eliciting MaxGR for the peak of the signal. Specifically, it was assumed that the most important part of the signal for threshold was the peak of the signal (i.e., 3 ms from signal onset). Thus, the stimulus capable of eliciting MaxGR was the output of the 150-ms, 95 dB SPL off-frequency precursor and the subsequent fixed off-frequency masker processed up to the point where the peak of the signal would occur τdel later. The output of this stimulus was determined from the linear I/O function (because it is off-frequency) and this output vector was called maxref. With this definition, maxref always contained the beginning of the precursor and the duration of maxref was dependent on τdel. For example, if τdel was 23 ms, then maxref was the output of the full 150-ms precursor but contained none of the masker (the peak of the signal occurs 23 ms later). If τdel was 15 ms, maxref contained the full 150-ms precursor precursor and the first 8 ms of the masker (the peak of the signal occurs 15 ms later). Once the maxref vector was determined, ΔG with each sample was calculated by

| (7) |

| (8) |

where t is time or samples and Lwin is the length of the analysis window (the maximum number of samples considered in calculating ΔG), which was set to the length of maxref. The term stim was the output vector of on- and off-frequency stimuli once they were scaled by their respective I/O functions. Once the stim length exceeded Lwin, Eq. 8 was used which disregards earlier samples so that the considered stim length is equal to Lwin. IN served as a “floor” and was the output of the internal noise parameter in Fig. 1 passed through Eqs. 1, 2 without internal noise. Because, as mentioned previously, internal noise limited the output minimum of all stimuli, subtracting IN in Eqs. 7, 8 results in a minimum value of zero. WGR was defined by

| (9) |

where t is time and τwin specifies the time constant, which was a free parameter. In Eqs. 7, 8, multiplication by WGR [Eq. 9] places greater weight on more recently processed samples and de-weights earlier samples prior to the summation.

Equations 7, 8, quite literally, calculate a proportion of MaxGR at each sample t. If stim is equal to maxref, ΔG equals MaxGR because the bracketed portion of Eq. 7 is equal to 1. A stimulus lower in output level and/or shorter in duration than maxref would elicit a proportion of MaxGR. The ΔG determined from Eqs. 7, 8 was used to determine the new I/O function that later sample points are processed through after a delay [applied in Eqs. 4, 5, and 6]. The result of this gain reduction module is that, although both on- and off-frequency stimuli are capable of eliciting gain reduction, only on-frequency stimuli, which are processed through an I/O function with gain, can be influenced by gain reduction after a delay. This approximates known processes of the MOCR. Figure 3 shows an example stimulus after this processing in the “Example Output” box. The black solid line shows a 150-ms, on-frequency precursor with a 20-ms masker, and signal processed by the TWM. The dashed gray line shows the stimuli processed through the TWM-GR.

After this processing, the stimuli (precursor and masker) with the signal and without the signal were then separately convolved with the forward masking temporal window described by Eq. 3. However, in Eq. 3, w was fixed at 0 (only one time constant) because it was assumed that the second time constant was replaced by τwin in the gain reduction module. The parameters for the TWM-GR model are T1, I, τdel, τwin, and SNR. For each subject, all data were fitted at once. The parameter estimates and RMS error for each subject are shown in Table TABLE I..

The fits for all participants and averaged data are plotted as solid lines in Fig, 4. The TWM fits did not predict any nonmonotonic threshold trends with precursor duration. Rather, predicted thresholds increased with increasing duration for both on- and off-frequency precursors. In contrast, the TWM-GR predicted a slight rollover in thresholds beyond 50 ms for some participants in the on-frequency precursor data but no nonmonotonic results in the off-frequency precursor data. The added module in the TWM-GR was necessary to account for this difference in trends for on- and off-frequency precursors. It is able to do so because, with the gain reduction feedback loop, on-frequency stimuli are influenced by gain reduction while off-frequency stimuli are not. The result is a difference between on- and off-frequency results as a function of duration. The parameter estimates of these fits with the TWM-GR in Table TABLE I. reveal fairly short MOCR delays, which means the initial ramped portion of the fixed masker was considered in calculating ΔG for the signal. However, parameter I was fairly large for most participants, as well, indicating that the off-frequency stimuli were scaled down in effectiveness in the TWM-GR. Thus, the ramped portion of the lower-level fixed off-frequency masker would have contributed little to ΔG compared to the precursor. It is possible that other permutations of the gain reduction module, perhaps which limit the analysis window in a different manner, would yield different estimates of MOCR delay. Comparing the RMS errors of the fits with the TWM and the TWM-GR, the TWM-GR model resulted in lower RMS errors for all subjects except S3.

DISCUSSION

Interpretation

Summary of findings

The primary aim of this study was to test the hypothesis that cochlear gain reduction, possibly via the MOCR, contributes to forward masking. The effect of precursor duration with on- and off-frequency precursors was compared to determine if rollover occurred in both conditions. In the introduction, it was theorized that if rollover was a manifestation of gain reduction affecting the precursor at the signal frequency place, it should not occur with an off-frequency precursor because it was assumed to have no gain at the signal frequency place. The results showed that threshold trends with duration were significantly different for the two precursor frequencies, even though thresholds were equal at some durations in the two conditions. Off-frequency precursor thresholds increased with increasing precursor duration. For some subjects, on-frequency precursor thresholds rolled over or reached a plateau beyond 50 ms. In the majority of data sets, thresholds were better predicted by a model incorporating temporal integration and gain reduction (TWM-GR) than one with just integration (TWM). These results are consistent with the hypothesis stated in the introduction that the precursor reduces gain of the cochlear amplifier through the MOCR.

The nonmonotonic effect with on-frequency precursor duration is contrary to any established neural mechanism of masking, which would predict either an increase or no change in threshold with increasing precursor duration. Indeed, the modeling results showed that the TWM, which simulates neural mechanisms, could only predict that thresholds increase or plateau with increasing duration. If the rollover were due to random variability, it might be expected that the duration at which threshold decreased would be random in nature, both within and across subjects. Instead, within subjects, threshold trends with each precursor were consistent across level, only scaled up with level. Across subjects, a peak in on-frequency precursor thresholds tended to occur at a 50-ms precursor duration. Because of the 20-ms masker, this corresponds to a delay between precursor onset and signal onset of 70-ms. Roverud and Strickland (2010) reported a similar finding—that the maximum in the temporal effect occurred at 70–75 ms delay from precursor onset to signal onset for precursors of varying durations and delays. The comparison of these on-frequency trends with off-frequency precursor results in the present study is also an argument against a threshold variability explanation—rollover was not present with the off-frequency precursor.

Possible sources of individual differences

Although there was not a statistically significant interaction of subject × frequency × duration, it can be seen in Fig. 2 that there was variability in the existence and size of rollover across subjects. Three subjects showed rollover with on-frequency precursors that remained with increasing precursor level (S1, S2, and S5). These participants also displayed the clearest difference in precursor duration trend between on- and off-frequency precursors. S3 and S4 displayed slight rollover at the lowest precursor level and a plateau beyond 50 ms with higher precursor levels in the on-frequency results.

One difference between these two groups of subjects was the location of the selected fixed masker level relative to the estimate of the breakpoint and compression in the fitted I/O functions. The breakpoint estimate from the fitted I/O functions was lowest for S3 and S4 (see Fig. 1), and the fixed masker levels selected for the precursor duration experiment (indicated by the arrows in Fig. 1) produced signal thresholds at or above the breakpoint estimate for these two listeners. The masker level selected for S4 corresponded to the compressive part of the fitted I/O function, and the masker level selected for S3 produced a signal threshold at the level of the breakpoint of the function. In contrast, the fixed masker levels for S1, S2, and S5 were well below the estimated onset of compression. This may explain why S3 and S4 did not display more obvious rollover in their results. Changes in gain act to shift the lower leg of the I/O function (Cooper and Guinan, 2006). If most of the thresholds obtained for S3 and S4 were in the region of compression, then small changes in gain below the breakpoint by the precursor may have had less of an impact on the signal.

All MOCR delays predicted in the TWM-GR were shorter than the average 25 ms onset delay reported by Backus and Guinan (2006). However, the TWM-GR predicted slightly longer MOCR delays closer to 25 ms for S2 and S5 (18 and 21, respectively), two listeners with clear rollover in their on-frequency data. Thus, it is also possible that variability in the existence and size of rollover may partly be explained by variability in certain characteristics of each listener's MOCR.

Potential influence of other factors

Middle ear muscle reflex

In this study, it was necessary to use high level off-frequency precursors so that on- and off-frequency precursor thresholds could be matched at some durations. Given the intensities used, 85, 90, and 95 dB SPL, it is possible that the middle ear muscle reflex (MEMR) was activated by the off-frequency precursors. When activated, the MEMR decreases the transmission of sound through the middle ear due to increased impedance. Woodford et al. (1975) demonstrated that a 500-ms, 2-kHz tone activated the MEMR at around 92 dB SPL. It should be noted that this reflex threshold was determined by an impedance change measured by standard immittance equipment; smaller impedance changes not detected by the equipment may have occurred at even lower elicitor levels.

MEMR threshold has been shown to vary considerably with stimulus duration. Specifically, MEMR thresholds can increase by up to 30 dB as elicitor duration is decreased from 500 ms to 10 ms (Woodford et al., 1975). This means that the shorter precursors in this study likely did not activate the MEMR, whereas the longer precursors may have activated the MEMR at the highest off-frequency precursor levels (90 and 95 dB SPL). The timing of the MEMR is considerably more sluggish than the MOCR, but also depends on elicitor level. The onset latency of the MEMR at 10 dB above reflex threshold is approximately 130 ms (Norris et al., 1974). The decay of the MEMR is quite long—over 300 ms (Norris et al., 1974). This means that with the precursor levels used in this study, signals following the longer precursors (120 and 150 ms) could be affected by the MEMR because they occur after the onset delay. Even so, the MEMR tends to affect transmission of lower frequencies more than the transmission of higher frequency sounds. Borg (1968) reported very slight to no attenuation (0 to 6 dB) for frequencies above 2000 Hz. Thus, even if the MEMR was activated by the longer, higher-level off-frequency precursors in the listeners in this study, it may not have impacted the transmission of sounds in the frequency region of our stimuli. Only if the transmission of 4-kHz is attenuated more than the transmission of the 2.4-kHz precursor and masker would the MEMR result in poorer signal threshold. Further exploration of this issue with more sensitive measures of the MEMR is needed to make a definitive conclusion about its influence in these results.

I/O function compression slope

The compression slopes (Fig. 1) were generally higher than have been reported in some previous psychophysical studies using GOM (Oxenham and Plack, 1997; Nelson et al., 2001). The source of this discrepancy may partly be due to the lower signal frequency in the present study (4-kHz) than in these previous studies (6-kHz). Oxenham and Plack (1997) and Nelson et al. (2001) also used maskers longer than the MOCR delay. This may have led to gain reduction for the signal that increased with increasing masker level. That is, the GOM functions with longer maskers could be reflecting an underlying I/O function that has changed across conditions. Another potential source of the high compression slopes in the present study is off-frequency listening. Because off-frequency listening plays a greater role at higher signal levels, GOM functions measured with this cue available become more linear (Nelson et al., 2001). This ultimately would lead to a higher estimate of compression slope in the fitted I/O functions. Although high-pass noise was used in the present study, the effects of off-frequency listening cannot be completely ruled out.

In order to determine what effect the compression estimates may have had on the precursor duration results and fits shown in Fig. 4, the TWM and TWM-GR were refit to the data of S1 and S5 using different estimates of compression slope. S1 showed the highest estimate of compression slope from the fitted I/O function in Fig. 1 (0.82), and S5 showed the lowest estimate of compression slope (0.29). For the refits with the models, S1's compression slope was changed to 0.2, and S5's compression slope was changed to 0.8. All other I/O function parameters (gain, breakpoint, internal noise) remained fixed at the values shown in Fig. 1.

The TWM and TWM-GR were first rerun with the same parameter estimates shown in Table TABLE I. and only the I/O function compression slope changed. These resulting refits are shown as the thick, solid black lines in the first and second rows of Fig. 5 for S1 and S5, respectively. The original fits from Fig. 4 are plotted for comparison as the light gray lines. It is apparent in the first and second rows of Fig. 5 that the TWM (first and second columns) is more sensitive to the change in compression slope than the TWM-GR (third and fourth columns). That is, the black and gray lines of TWM fits show little similarity with the change in compression slope, whereas the black and gray lines display more overlap in the TWM-GR fits. This is likely due to the fact that in the TWM-GR, the shifting lower leg of the I/O function with gain change means that more signal thresholds remain below the compressive region and are relatively unaffected by differences in compression slope. Thresholds occurring far above the breakpoint in conditions with little gain reduction would be most influenced by compression. In contrast, the I/O function in the TWM remains static, so any thresholds above the breakpoint would be influenced by compression. For the TWM-GR, the main difference for fits with the lower compression slope (black lines for S1 and gray lines for S5), was that the higher level, short on-frequency precursors were predicted to have less of an effect than with the higher compression slope. For S5, fits with both compression slopes display rollover. The fact that rollover remains and there is little change in the TWM-GR predictions suggests that compression plays a smaller role in a system with gain reduction (as simulated by the TWM-GR).

Figure 5.

TWM fits (first and second columns) and TWM-GR fits (third and fourth columns) after the I/O function compression slope had been changed are shown as solid, black lines. The data from Fig. 2 are replotted and the original model fits from Fig. 4 are replotted for comparison as light gray lines. For S1 (first and third rows), compression slope in the model was changed from 0.82 to 0.2. For S5 (second and fourth rows), compression was changed from 0.29 to 0.8. The solid black lines in the first and second rows show the fits to S1 and S5 with the same parameters as in Table TABLE I., only the compression slope was changed. The solid black lines in the third and fourth rows show the refits with compression slope value changed and new parameter estimates shown in Table TABLE II..

Next, the TWM and TWM-GR were refit to the data with parameters in these models adjusted to minimize RMS error with the different compression slope values. These resulting refits are shown as the thick, black lines in the third (S1) and fourth (S5) rows of Fig. 5. The trend of these new fits is fairly similar to the original fits (gray lines). The TWM and TWM-GR parameter estimates of these refits are shown in Table TABLE II.. For the TWM, the lower compression slope estimate used for the fits of each subject (Table TABLE I. for S5 and Table TABLE II. for S1) resulted in higher estimates of T1, I, and lower estimates of T2. The lower compression slope for S1 not only resulted in a lower T2 estimate, but also an estimate that was more consistent with previous TWM studies (Oxenham and Moore, 1994; Oxenham, 2001). This suggests that the very long T2 estimates from the original fits (Table TABLE I.) were related to the more linear I/O functions estimated in the present study. Specifically, Oxenham (2001) used compression slopes of 0.16 and 0.25, whereas the original compression estimate for S1 was 0.82 (Fig. 1). In fact, in the present study there was a strong positive correlation between compression slope shown in Fig. 1 and T2 in Table TABLE I. (r = 0.89, p = 0.017).

TABLE II.

Parameter estimates and RMS errors from the TWM and TWM-GR for S1 and S5 when the I/O function compression estimates used in these models were changed.

| TWM | T1 | T2 | w | I | SNR | RMS error | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 (c = 0.2) | 3.80 | 40.09 | 2.77 × 10−3 | 9.36 | 12.82 | 3.12 | |

| S5 (c = 0.8) | 2.44 | 41.01 | 2.15 × 10−3 | −2.02 | 9.84 | 2.74 | |

| TWM-GR | T1 | τdel (ms) | τwin (ms) | MaxGR (data) | I | SNR | RMS error |

| S1 (c = 0.2) | 3.98 | 15 | 60.96 | 28.42 | 12.71 | 6.22 | 2.99 |

| S5 (c = 0.8) | 0.001 | 21 | 32.36 | 20.40 | 9.68 | 7.49 | 1.81 |

For the TWM-GR, using a function with a lower compression slope led to higher estimates of I and lower estimates of τwin for S1 and S5. For both subjects, a slightly higher RMS error from the TWM-GR occurred when an I/O function with a lower compression slope was used (Table TABLE II. for S1, Table TABLE I. for S5). For the TWM, a lower compression slope led to a lower RMS error for S5 but a higher RMS error for S1. For either compression slope value, however, the RMS error was lower for the TWM-GR than the TWM, and the TWM-GR was still able to predict rollover. Altering the compression slope value in the TWM did not allow it to capture the difference in precursor duration trends for on- and off-frequency precursors. Overall, these results suggest that compression slope would not alter or explain the rollover effect or the difference in precursor duration trends for on- and off-frequency precursors.

2.4-kHz as a linear referent for 4-kHz

Some previous studies have suggested that a 2.4-kHz masker is not an entirely linear referent for a 4-kHz signal (e.g., Lopez-Poveda and Alves-Pinto, 2008). In contrast, other studies support the assumption that the 2.4-kHz stimuli used in this study are represented linearly at a 4-kHz CF (Jennings and Strickland, 2012b; Yasin et al., 2013). The primary difference between these studies is the masking method used. Lopez-Poveda and Alves-Pinto (2008) used the temporal masking curve (TMC) method, with relatively long maskers and masker-signal delays. Long maskers and masker-signal delays could evoke the MOCR for the signal, which could change the underlying I/O function being measured. Even if the 2.4-kHz stimuli used in this study were not entirely linear at the 4-kHz CF, the effect on the data in Fig. 1 would be a decreased estimate of the I/O function compression slope. As was shown in the previous section, this was not predicted to influence the conclusion drawn from the modeling that gain reduction is important to explain the difference in trends between on- and off-frequency precursors. One other possible consequence of the 2.4-kHz stimuli not being linear at 4-kHz (and perhaps being processed with some gain there), is the off-frequency precursor may have been influenced by the gain reduction at the 4-kHz place, albeit to a lesser extent than the on-frequency stimuli. This idea is not supported by the data, where no nonomontonic effects were seen with off-frequency precursor duration.

Relationship to previous results and caveats

The MOCR is not a mechanism typically included in models of forward masking. Some models have incorporated a process of adaptation (Dau et al., 1996a; Oxenham, 2001; Ewert et al., 2007); however, this adaptation is placed beyond the level of the cochlea and thus would be expected to produce similar effects as a function of time for on- and off-frequency stimuli. The TWM, using a process of integration, has been able to predict forward masking results with on-frequency maskers without a gain adaptation module (Oxenham and Moore, 1994; Oxenham, 2001). However, no TWM studies directly compare duration results with on-frequency and off-frequency maskers, where effects of the MOCR may be evident. In the TWM-GR in this study, a gain adaptation process modeled after the sluggish time course of the MOCR occurred at the level of the cochlea. Because this gain adaptation affected on-frequency stimuli but not off-frequency stimuli, the TWM-GR was able predict rollover with on-frequency precursors and a different result with off-frequency precursors. The models used in this study were designed to analyze the specific stimulus conditions in this study. In order to examine conditions with more complex stimuli, a more computational approach may be necessary. Although this study provides evidence that the MOCR may be responsible for the frequency-specific rollover effect observed, only two peripheral mechanisms were compared and other possibly more central auditory processes cannot be ruled out. The requirement for an alternative account is that it must be able to explain the different trend with precursor frequency over time.

The maximum amount of estimated gain reduction in the present study was between 20 and 28 dB with the highest-level precursor (Table TABLE I.). It is unclear whether tonal elicitors are effective enough to elicit gain reduction of the magnitude observed here. Lilaonitkul and Guinan (2009) demonstrated in their human SFOAE study that contralateral tonal elicitors were nearly as effective as narrowband noise elicitors in terms of the measured MOC effect. However, the relationship between magnitude of MOC effect measured with OAE suppression and magnitude of gain reduction is not known. Tones have been demonstrated to elicit an MOC effect in the cat as measured by contralateral suppression of auditory nerve fiber responses (Warren and Liberman, 1989a,b) and of compound action potentials (Liberman, 1989). Warren and Liberman (1989b) reported as much as a 12-dB shift in the auditory neuron rate level function with contralateral tones. However, as the ipsilateral effect of the MOCR may be either equal to or stronger than the contralateral effect (Lilaonitkul and Guinan, 2009), more gain reduction might be expected with an ipsilateral elicitor. Recent modeling work has enabled the quantification of previous physiological data in the cat in terms of amount of gain reduction in response to ipsilateral noise (Chintanpalli et al., 2012; Smalt et al., 2013). Those results are consistent with over 20 dB of gain reduction in the data sets modeled. Overall, the precise magnitude of possible gain reduction in dB by tones in the ipsilateral ear is not known. However, physiological and modeling studies indicate that tones can elicit the MOCR and suggest that the present gain reduction estimates are not unreasonable.

The conditions tested in this study are not comparable to everyday listening scenarios typically involving acoustically complex, temporally overlapping sounds such as speech. However, in this study and others from this laboratory, forward masking is used primarily as a tool to examine mechanisms of sound interaction without additional effects of suppression. One mechanism implicated in these results, the MOCR, is predicted to lead to poorer thresholds in forward masking, but may be beneficial to listeners in more complex acoustic environments. The MOCR has been suggested to play a role in protecting the ear against damage from sound overexposure (Maison and Liberman, 2000) and in enhancing the perception of speech in noisy environments (Giraud et al., 1997; Kumar and Vanaja, 2004). The results of this study suggest that the MOCR should be considered in psychophysical results with more basic stimuli, as well.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded by a grant to the second author: NIH (NIDCD) Grant No. R01-DC008327, and by a fellowship grant to the first author: NIH(NIDCD): T32DC000030-21.

Portions of this research and earlier versions of the model were presented at the 16th International Symposium on Hearing, Cambridge, UK, July 2012, and at the joint 165th meeting of the Acoustical Society of America, Montreal, Quebec, June 2013.

References

- Backus, B. C., and Guinan, J. J., Jr. (2006). “ Time-course of the human medial olivocochlear reflex,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 119, 2889–2904. 10.1121/1.2169918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassim, M. K., Miller, R. L., Buss, E., and Smith, D. W. (2003). “ Rapid adaptation of the 2f1-f2 DPOAE in humans: Binaural and contralateral stimulation effects,” Hear. Res. 182, 140–152. 10.1016/S0378-5955(03)00190-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borg, E. (1968). “ A quantitative study of the effect of the acoustic stapedius reflex on sound transmission through the middle ear of man,” Acta Oto-Laryngol. 66, 461–472. 10.3109/00016486809126311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chintanpalli, A., Jennings, S. G., Heinz, M. G., and Strickland, E. A. (2012). “ Modeling the anti- masking effects of the olivocochlear reflex in auditory nerve responses to tones in sustained noise,” J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 13, 219–235. 10.1007/s10162-011-0310-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, N. P., and Guinan, J. J., Jr. (2006). “ Efferent-mediated control of basilar membrane motion,” J. Physiol. (London) 576, 49–54. 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.114991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dau, T., Puschel, D., and Kohlrausch, A. (1996a). “ A quantitative model of the “effective” signal processing in the auditory system. I. Model structure,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 99(6), 3615–3622. 10.1121/1.414959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dau, T., Puschel, D., and Kohlrausch, A. (1996b). “ A quantitative model of the “effective” signal processing in the auditory system. II. Simulations and measurements,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 99(6), 3623–3631. 10.1121/1.414960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewert, S. D., Hau, O., and Dau, T. (2007). “ Forward masking: Temporal integration or adaptation?,” in Hearing–From Sensory Processing to Perception, edited by Kollmeier B., Klump G., Hohmann V., Langemann U., Mauermann M., Uppenkamp S., and Verhey J. (Springer-Verlag, Berlin: ), pp. 165–174. [Google Scholar]

- Giraud, A. L., Garnier, S., Micheyl, C., Lina, G., Chays, A., and Chery-Croze, S. (1997). “ Auditory efferents involved in speech-in-noise intelligibility,” NeuroReport 8, 1779–1783. 10.1097/00001756-199705060-00042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinan, J. J., Jr. (2006). “ Olivocochlear efferents: Anatomy, physiology, function, and the measurement of efferent effects in humans,” Ear. Hear. 27, 589–607. 10.1097/01.aud.0000240507.83072.e7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, D. M., and Dallos, P. (1979). “ Forward masking of auditory nerve fiber responses,” J. Neurophysiol. 42(4), 1083–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James, A. L., Harrison, R. V., Pienkowski, M., Dajani, H. R., and Mount, R. J. (2005). “ Dynamics of real time DPOAE contralateral suppression in chinchillas and humans,” Int. J. Audiol. 44, 118–129. 10.1080/14992020400029996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, S. G., and Strickland, E. A. (2010). “ The frequency selectivity of gain reduction masking: Analysis using two equally effective maskers,” in Advances in Auditory Physiology, Psychophysics and Models, edited by Lopez-Poveda E. A., Palmer A. R., and Meddis R. (Springer, New York: ), pp. 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, S. G., and Strickland, E. A. (2012a). “ Evaluating the effects of olivocochlear feedback on psychophysical measures of frequency selectivity,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 132(4), 2483–2496. 10.1121/1.4742723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, S. G., and Strickland, E. A. (2012b). “ Auditory filter tuning inferred with short sinusoidal and notched-noise maskers,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 132(4), 2497–2513. 10.1121/1.4746029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, S. G., Strickland, E. A., and Heinz, M. G. (2009). “ Precursor effects on behavioral estimates of frequency selectivity and gain in forward masking,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 125, 2172–2181. 10.1121/1.3081383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd, G., Jr., and Feth, L. L. (1982). “ Effects of masker duration in pure-tone forward masking,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 72(5), 1384–1386. 10.1121/1.388443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krull, V., and Strickland, E. A. (2008). “ The effect of a precursor on growth of forward masking,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 123, 4352–4357. 10.1121/1.2912440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, U. A., and Vanaja, C. S. (2004). “ Functioning of olivocochlear bundle and speech perception in noise,” Ear. Hear. 25(2), 142–146. 10.1097/01.AUD.0000120363.56591.E6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt, H. (1971). “ Transformed up-down methods in psychoacoustics,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 49, 467–477. 10.1121/1.1912375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman, M. C. (1989). “ Rapid assessment of sound-evoked olivocochlear feedback: Suppression of compound action potentials by contralateral sound,” Hear. Res. 38, 47–56. 10.1016/0378-5955(89)90127-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilaonitkul, W., and Guinan, J. J., Jr. (2009). “ Reflex control of the human inner ear: A half- octave offset in medial efferent feedback that is consistent with an efferent role in the control of masking,” J. Neurophysiol. 101, 1394–1406. 10.1152/jn.90925.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Poveda, E., and Alves-Pinto, A. (2008). “ A variant temporal-masking-curve method for inferring peripheral auditory compression,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 123(3), 1544–1554. 10.1121/1.2835418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maison, S. F., and Liberman, M. C. (2000). “ Predicting vulnerability to acoustic injury with a noninvasive assay of olivocochlear reflex strength,” J. Neurosci. 20(12), 4701–4707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meddis, R., and O'Mard, L. (2005). “ A computer model of the auditory-nerve response to forward-masking stimuli,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 117(6), 3787–3798. 10.1121/1.1893426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore, B. C. J., Glasberg, B. R., Plack, C. J., and Biswas, A. K. (1988). “ The shape of the ear's temporal window,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 83(3), 1102–1116. 10.1121/1.396055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, D. A., Schroder, A. C., and Wojtczak, M. (2001). “ A new procedure for measuring peripheral compression in normal-hearing and hearing-impaired listeners,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 110(4), 2045–2064. 10.1121/1.1404439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris, T. W., Stelmachowicz, P., Bowling, C., and Taylor, D. (1974). “ Latency measures of the acoustic reflex: Normal versus Sensorineural,” Audiology 13, 464–469. 10.3109/00206097409071709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxenham, A. J. (2001). “ Forward masking: Adaptation or integration?,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 109(2), 732–741. 10.1121/1.1336501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxenham, A. J., and Bacon, S. P. (2004). “ Psychophysical manifestations of compression: Normal-hearing listeners,” in Compression: From Cochlea to Cochlear Implants, edited by Bacon S. P., Fay R. R., and Popper A. N. (Springer-Verlag, New York: ), pp. 62–105. [Google Scholar]

- Oxenham, A. J., and Moore, B. C. J. (1994) “ Modeling the additivity of nonsimultaneous masking,” Hear. Res. 80, 105–118. 10.1016/0378-5955(94)90014-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxenham, A. J., and Plack, C. J. (1997). “ A behavioral measure of basilar-membrane nonlinearity in listeners with normal and impaired hearing,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 101(6), 3666–3675. 10.1121/1.418327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxenham, A. J., and Plack, C. J. (2000). “ Effects of masker frequency and duration in forward masking: further evidence for the influence of peripheral nonlinearity,” Hear. Res. 150, 258–266. 10.1016/S0378-5955(00)00206-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plack, C. J. and Moore, B. C. J. (1990). “ Temporal window shape as a function of frequency and level,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 87(5), 2178–2187. 10.1121/1.399185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plack, C. J., and Oxenham, A. J. (1998). “ Basilar-membrane nonlinearity and the growth of forward masking,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 103(3), 1598–1608. 10.1121/1.421294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relkin, E. M., and Turner, C. W. (1988). “ A reexamination of forward masking in the auditory nerve,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 84, 584–591. 10.1121/1.396836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roverud, E., and Strickland, E. A. (2010). “ The time course of cochlear gain reduction measured using a more efficient psychophysical technique,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 128(3), 1203–1214. 10.1121/1.3473695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggero, M. A. (1992). “ Responses to sound of the basilar membrane of the mammalian cochlea,” Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2, 449–456. 10.1016/0959-4388(92)90179-O [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smalt, C. J., Heinz, M. G., and Strickland, E. A. (2013). “Modeling the time-varying and level- dependent effects of the medial olivocochlear reflex in auditory nerve response,” J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol, DOI: 10.1007/s10162-013-0430-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Smith, R. L. (1977). “ Short-term adaptation in single auditory nerve fibers: Some poststimulatory effects,” J. Neurophysiol. 40, 1098–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren, E. H., and Liberman, M. C. (1989a). “ Effects of contralateral sound on auditory-nerve responses. I. Contributions of cochlear efferents,” Hear. Res. 37, 89–104. 10.1016/0378-5955(89)90032-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren, E. H., and Liberman, M. C. (1989b). “ Effects of contralateral sound on auditory-nerve responses. II. Dependence on stimulus variables,” Hear. Res. 37, 105–122. 10.1016/0378-5955(89)90033-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodford, C., Henderson, D., Hamernik, R., and Feldman, A. (1975). “ Threshold-duration function of the acoustic reflex in man,” Audiology 14, 53–62. 10.3109/00206097509071723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasin, I., Drga, V., and Plack, C. (2013). “ Estimating peripheral gain and compression using fixed-duration masking curves,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 133(6), 4145–4155. 10.1121/1.4802827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasin, I., and Plack, C. J. (2003). “ The effects of a high-frequency suppressor on tuning curves and derived basilar-membrane response functions,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 114, 322–332. 10.1121/1.1579003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]