Significance

Within-population genetic diversity is an essential evolutionary prerequisite for processes ranging from antibiotic resistance to niche adaptation, but its generation is poorly understood, with most studies focusing on fixed substitutions at the end point of long-term evolution. Using deep sequencing, we analyzed short-term, within-population genetic diversification occurring during biofilm formation of the model bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa. We discovered extensive parallel evolution between biological replicates at the level of pathways, genes, and even individual nucleotides. Short-term diversification featured positive selection of relatively few nonsynonymous mutations, with the majority of the genome being conserved by negative selection. This result is broadly consistent with observations of long-term evolution and suggests diversifying selection may underlie genetic diversification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms.

Keywords: dispersal, prophage, haplotypes

Abstract

Generation of genetic diversity is a prerequisite for bacterial evolution and adaptation. Short-term diversification and selection within populations is, however, largely uncharacterised, as existing studies typically focus on fixed substitutions. Here, we use whole-genome deep-sequencing to capture the spectrum of mutations arising during biofilm development for two Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains. This approach identified single nucleotide variants with frequencies from 0.5% to 98.0% and showed that the clinical strain 18A exhibits greater genetic diversification than the type strain PA01, despite its lower per base mutation rate. Mutations were found to be strain specific: the mucoid strain 18A experienced mutations in alginate production genes and a c-di-GMP regulator gene; while PA01 acquired mutations in PilT and PilY1, possibly in response to a rapid expansion of a lytic Pf4 bacteriophage, which may use type IV pili for infection. The Pf4 population diversified with an evolutionary rate of 2.43 × 10−3 substitutions per site per day, which is comparable to single-stranded RNA viruses. Extensive within-strain parallel evolution, often involving identical nucleotides, was also observed indicating that mutation supply is not limiting, which was contrasted by an almost complete lack of noncoding and synonymous mutations. Taken together, these results suggest that the majority of the P. aeruginosa genome is constrained by negative selection, with strong positive selection acting on an accessory subset of genes that facilitate adaptation to the biofilm lifecycle. Long-term bacterial evolution is known to proceed via few, nonsynonymous, positively selected mutations, and here we show that similar dynamics govern short-term, within-population bacterial diversification.

Diversifying selection within bacterial populations underpins a range of ecological and clinical phenomena, for example niche adaptation (1–3) and antibiotic resistance (4). During diversifying selection, a single population explores multiple fitness peaks, resulting in subpopulations with different adaptive mutations. This kind of within-population genetic diversity can provide the raw material on which long-term evolution acts. However, diversifying selection of bacterial populations is still poorly understood, because previous experimental evolution and epidemiological studies typically have focused on fixed substitutions at the end point of evolution (5), ignoring short-term or within-population effects.

Laboratory-grown Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms provide an ideal model for investigating within-population diversification. The bacterium P. aeruginosa is a widespread, Gram-negative generalist and can have either a planktonic, motile lifestyle or exist as a biofilm (i.e., a surface-attached cells embedded within an extracellular polymeric matrix). P. aeruginosa has been the focus of extensive research, because of both its status as a model organism and its ability to form opportunistic, chronic, often lethal biofilm-based infections in the lungs of cystic fibrosis patients (6), where it rapidly acquires antibiotic resistance (7).

Both clinical isolates and the dispersal populations of laboratory-grown P. aeruginosa biofilms are known to exhibit high numbers of heritable phenotypic variants (8, 9), indicating within-population genetic diversification during biofilm growth. Genetic diversification during biofilm development has been proposed as a mechanism underlying P. aeruginosa’s propensity for swift adaptation to antibiotics. Similarly, genetic diversification may determine the potential for adaptive responses to stress, as indicated by the almost complete eradication of P. aeruginosa recA mutants (which do not produce morphotypic variants) in the presence of oxidative stress, whereas wild-type biofilms show significant survival (10).

Diversifying selection may underlie the genetic diversification of P. aeruginosa biofilms. For instance, the unique biofilm lifecycle [which progresses through initial reversible surface attachment, irreversible attachment, microcolony formation, maturation and localized cell death, and cell dispersal (11)] may lead to the presence of multiple ecological niches during biofilm development. A related theory suggests that the spatial structuring of biofilms, in particular microcolony formation, may promote diversification (12). Alternatively, diversification may be neutral, involving mechanisms such as elevated mutation rates (i.e., hypermutator strains) and DNA damage caused by toxic levels of reactive oxygen and nitrogen molecules (12, 13).

Unraveling the contributions of selective and/or neutral mechanisms to diversification within a bacterial population requires the full spectrum of variants to be cataloged. With the advent of deep-sequencing protocols, this cataloging is now technically feasible. Deep sequencing harnesses the high coverage afforded by next-generation sequencing to provide a cross-section of within-population genetic diversity. Deep sequencing has been used extensively to track the evolution of viral infections (14). For instance, a longitudinal deep-sequencing study of early acute hepatitis C virus revealed that within each subject two sequential bottlenecks shaped the course of infection (15). To date, however, deep sequencing of bacterial populations has been limited. One study based on Sanger sequencing used the population sample concept to show the coexistence of several Leptospirillum group II substrains in an acid mine drainage biofilm (16). Although sample depth in this study was limited by the technology available at the time, the authors successfully confirmed within-population genetic diversity of an environmental biofilm. More recently, next-generation sequencing demonstrated the presence of two closely related Citrobacter UC1CIT strains within the gut microbiota of a premature infant (17). The success of these relatively low-coverage studies encourages a more detailed, deep-sequencing-based analysis of genetic diversity within evolving bacterial populations.

Here, longitudinal, genome-wide deep sequencing was used to reveal the underlying genetic structure of P. aeruginosa biofilms for both the type strain (PA01) and a clinical isolate (18A). Adaptive variation was identified as the prevalent source of genetic diversification during P. aeruginosa biofilm growth. This study also represents a whole-genome analysis of short-term bacterial genetic diversification, with sufficient sample depth to resolve within-population evolutionary dynamics.

Results

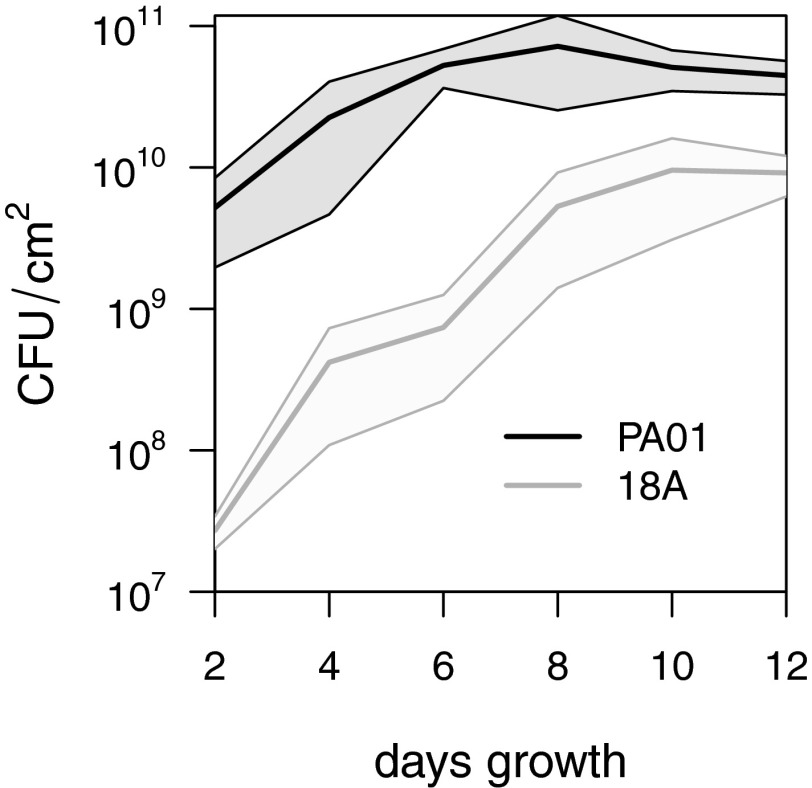

To analyze short-term within-population diversification in bacterial biofilms, we studied the P. aeruginosa model strain PA01 and the clinical isolate 18A. Biofilms were grown under defined laboratory conditions known to generate reproducible morphological variants (9). The initial inoculum, the mature and developed biofilm after 4 d of growth, and the dispersal population after 11 d of biofilm growth were sequenced to an average depth between 680 and 7,330 (Table S1). Biofilm growth curves for both strains (Fig. 1) demonstrate the extremely short time scale used in this study; 11 d of growth equates to ∼5.3 generations for P. aeruginosa PA01 and 10.3 generations for P. aeruginosa 18A. To assess the potential for parallel evolution and reproducibility of results, independent duplicate experiments for both strains (hereafter referred to as “exp1” and “exp2”) were performed.

Fig. 1.

Growth of P. aeruginosa PA01 and 18A biofilms. Bold lines give the mean number of cfus per square centimeter of surface area at each time point across nine independent replicate biofilms for each strain. Shaded areas represent the 95% CIs. Note the logarithmic scale for the y-axis.

Distinguishing low-frequency true variants from sequencing errors is central to a sound analysis of deep-sequencing data. Error correction by probabilistic clustering, such as that used by Bull et al. (15), currently is not feasible for bacterial deep sequencing because of the computational intensity of analyzing larger bacterial genomes and the need for variants to co-occur within a read length (such co-occurrence is less likely for bacterial genomes than for viral genomes) (18). Instead, we accounted for sequencing errors by using a matched samples approach developed for deep sequencing of cancer tissue samples (19). This approach statistically compares potential variant frequencies at each genomic position between an experimental sample and a control, using correlation between sequencing errors within an individual sequencing run. When this method is applied to cancer tissue samples, tumor cells are compared with a somatic control. Here, overnight cultures of the relevant P. aeruginosa strain were used as controls and were compared with both the 4-d biofilm and the dispersal population at 11 d. The analysis of both P. aeruginosa strains revealed genetically heterogeneous biofilm and dispersal populations, characterized by single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small deletions within genomic coding regions (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Variants in P. aeruginosa 18A biofilm (day 4) and dispersal populations (day 11)

| Gene | Variant | Function | Effect | 18Aexp1 day 4 | 18Aexp1 day 11 | 18Aexp2 day 4 | 18Aexp2 day 11 | ||||

| % | s | % | s | % | s | % | s | ||||

| c553 | c.512C > A | Electron transport | p.(P171H) | 8.4 | (0.72) | 7.8 | −0.02 | 4.0 | (0.58) | — | |

| #mreD | c.48A > G | Cell shape | p.(=) | 88.2 | (1.38) | 76.4 | −0.19 | 91.7 | (1.44) | 98.0 | 0.33 |

| #yrbE | c.9A > G | ABC transport | p.(=) | 45.8 | (1.06) | 51.3 | 0.05 | 44.6 | (1.05) | 36.9 | −0.07 |

| amrZ | c.104C > T | Alginate/Flagella | p.(A35V) | — | — | 10.2 | (0.81) | 7.5 | −0.07 | ||

| algC | c.1938_1943del | Alginate | p.(D647_G648del) | — | 3.8 | (0.83) | — | 17.6 | (1.19) | ||

| algC | c.1945G > T | Alginate | p.(D649Y) | — | — | — | 4.2 | (0.84) | |||

| algC | c.2060del | Alginate | p.(F687*) | — | 5.2 | (0.89) | — | — | |||

| clpX | c.251del | Alginate | p.(A85Pfs*7) | — | — | 2.7 | (0.55) | 3.0 | 0.03 | ||

| algB | c.854_863del | Alginate | p.(N288Wfs*20) | — | — | — | 14.3 | 1.04 | |||

| algT | c.136G > A | Alginate | p.(E46K) | — | — | 5.1 | (0.67) | — | |||

| wspF | c.47T > C | c-di-GMP metabolism | p.(L16P) | — | 11.1 | (1.03) | — | — | |||

| wspF | c.720C > A | c-di-GMP metabolism | p.(Y240*) | — | — | — | 8.1 | (0.90) | |||

| wspF | c.837C > A | c-di-GMP metabolism | p.(D279E) | — | 26.2 | (1.24) | — | — | |||

“Gene” and “Function” refer to the name and the general function of the homologous gene in the P18A reference genome. For variants, either the nucleotide mutation or the deletion length is given relative to the start of the relevant gene. The effect of the variant on the amino acid sequence is also specified. Variant frequencies are given relative to a control for 18Aexp1 day 4 (biofilm), 18Aexp1 day 11 (dispersal), 18Aexp2 day 4 (biofilm), and 18Aexp2 day 11 (dispersal) samples. Malthusian selection coefficients (s) are also given, relative to the number of bacterial generations since the last time point. Parentheses indicate the variant was not present in any reads in the previous time point; in such cases the calculation of s is based on an inferred maximum variant frequency at the previous time point (1/read depth). A dash indicates the variant was not detected within the respective sample (limit of detection ∼1.2%). SNVs with frequencies given in bold were also detected when reads were subsampled to an average depth of 680.

Changes codon from a rarely used to a commonly used codon, possibly increasing translation.

Table 2.

Variants in P. aeruginosa PA01 biofilm (day 4) and dispersal (day 11) populations

| Gene | Variant | Function | Effect | PA01exp1 day 4 | PA01exp1 day11 | PA01exp2 day 4 | PA01exp2 day11 | ||||

| % | s | % | s | % | s | % | s | ||||

| pilT | c.570_581del | Type IV pili | p.(S191_R194del) | — | — | 7.4 | (3.52) | — | — | 3.6 | (3.45) |

| pilT | c.959del | Type IV pili | p.(L320Pfs*9) | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.8 | (2.40) |

| pilT | c.970_984del | Type IV pili | p.(V324_L328del) | — | — | 1.0 | (2.24) | — | — | 0.8 | (2.40) |

| pilY1 | c.3274C > T | Type IV pili | p.(Q1092*) | — | — | — | — | — | — | 4.2 | 3.15 |

| wzy | c.620del | Lipopoly-saccharide | p.(V209Sfs*17) | — | — | 0.5 | 1.65 | — | — | — | — |

“Gene” and “Function” refer to the name and the general function of the homologous gene in the PA01 reference genome. For variants, either the nucleotide mutation or the deletion length is given relative to the start of the relevant gene. The effect of the variant on the amino acid sequence is also specified. Variant frequencies are given relative to a control for PA01exp1 day 4 (biofilm), PA01exp1 day 11 (dispersal), PA01exp2 day 4 (biofilm), and PA01exp2 day 11 (dispersal) samples. Malthusian selection coefficients (s) are also given, relative to the number of bacterial generations since the last time point. Parentheses indicate the variant was not present in any reads in the previous time point; in such cases the calculation of s is based on an inferred maximum variant frequency at the previous time point (1/read depth). A dash indicates the variant was not detected within the respective sample (limit of detection ∼0.2%). SNVs with frequencies given in bold were also detected when reads were subsampled to an average depth of 680.

Genetic Diversity in P. aeruginosa 18A.

Independently grown biofilms of P. aeruginosa 18A experienced parallel evolution, with mutations in the same genes and pathways detected at similar frequencies in both experiments (Table 1). In both samples, diversity increased between days 4 and 11 with seven (five SNVs and two deletions) and eight (five SNVs and three deletions) variants observed in the P. aeruginosa 18Aexp1 and 18Aexp2 dispersal populations, respectively.

Three SNVs (one in each of the genes c553, mreD, and yrbE) were detected at similar frequencies at both day 4 and day 11 for both experiments, at frequencies of 4–8%, 76–98%, and 37–51%, respectively. SNVs in mreD and yrbE were synonymous and hence are predicted to be silent. However, analysis of codon-use bias indicated that the relative synonymous codon use (RSCU) changed from 0.07 to 4.01 for mreD and from 0.04 to 0.16 for yrb. In both cases, the wild-type codon was the only instance of the rare codon within the gene and thus is likely to be a limiting factor in translation (20). In addition, a number of SNVs that altered the coded amino acid were found in genes involved in alginate production (amrZ, algC, clpX, algB, and algT) and in genes involved in intracellular signaling and motility (wspF and amrZ) (Table 1).

Genetic Diversity of P. aeruginosa PA01.

Populations of P. aeruginosa PA01 exhibited less genetic diversity than those of P. aeruginosa 18A (Table 2). Mutation rates measured using Luria–Delbrück fluctuation tests indicated that the higher diversity in P. aeruginosa 18A was not the result of this strain being a hypermutator (Table 3), because its experimentally determined mutation rate per base pair of 2.50 × 10−10 [95% confidence interval (CI): 1.42 × 10−10, 3.80 × 10−10] was actually lower than that of P. aeruginosa PA01 (10.38 × 10−10; 95% CI: 6.54 × 10−10, 14.85 × 10−10) and was also within the range of nonhypermutator Escherichia coli (18, 21).

Table 3.

Mutation rates from literature and Luria–Delbrück fluctuation tests

| Strain | Target | Mutation rate per bp (95% CI) | Source |

| P. aeruginosa PA01 | RpoB | 10.38 × 10−10 (6.54 × 10−10, 14.85 × 10−10) | This study |

| P. aeruginosa 18A | RpoB | 2.50 × 10−10 (1.42 × 10−10, 3.80 × 10−10) | This study |

| E. coli K12 | RpoB | 6.24 × 10−10 (3.94 × 10−10, 8.91 × 10−10) | This study |

| E. coli | LacI | 6.93 × 10−10 | (18) |

| E. coli | His | 5.06 × 10−10 | (18) |

| E. coli REL606 | NA | 1.60 × 10−10 | (21) |

Values contained in the first three rows of this table were determined experimentally using Luria–Delbrück fluctuation tests. E. coli was included as a control, allowing comparison with other estimates of mutation rates in the literature.

No nucleotide changes within the PA01 chromosome were observed after 4 d of biofilm growth. By 11 d, two (PA01exp1) and three (PA01exp2) deletions and one SNV (PA01exp2) were detected in genes involved in motility (pilT and pilY1) (Table 2). These mutations are predicted to result in amino acid deletions, frameshifts, or stop codons and therefore are likely to result in impairment or loss of function. Additionally, one low-frequency SNV within the lipopolysaccharide pathway gene wzy was detected in P. aeruginosa PA01exp1. The absence of SNVs in the PA01 population on day 4 and their subsequent increase also correlated with the presence of small-colony variants (SCV) in the biofilm effluent, which were absent early on but reached a frequency of >20% after 11 d (Fig. 2). Although the total number of variants identified was low compared with P. aeruginosa 18A biofilms, Malthusian selection coefficients (s) indicated that the strength of selection acting on the PA01 variants was stronger than that acting on 18A variants (Tables 1 and 2).

Fig. 2.

Percentage of SCVs in biofilm effluent from P. aeruginosa PA01.

Although limited variants were detected within the bacterial portion of the P. aeruginosa PA01 genome, a substantial number of SNVs were found in reads derived from the Pf4 bacteriophage, with diversity increasing during P. aeruginosa PA01 biofilm growth (Table 4). Pf4 exists in multiple forms within P. aeruginosa PA01 populations, as a prophage integrated within the P. aeruginosa PA01 genome, as a circular replicating form within individual cells, and as a linear ssDNA free phage (22). Only the former two forms would be sequenced by the protocol used here. To sequence the genomes of the ssDNA Pf4 particles, phage DNA was isolated from the dispersal sample, converted to dsDNA, and then sequenced separately from the genomic DNA (Material and Methods).

Table 4.

Pf4 variants from PA01 biofilms and dispersal populations for both prophage/replicative and free forms

| Variant | Gene | Effect | PA01exp1 (%) | PA01exp2 (%) | |||

| Day 4 | Day 11 | Day 4 | Day 11 | Free | |||

| c.310G > T | PA0716 | p.(D104 > Y) | — | — | — | 3.0 | 8.3 |

| c.-60G > T | up. c | NA | — | — | — | — | 0.3 |

| c.-59G > T | up. c | NA | — | — | — | — | 0.3 |

| c.-57G > A | up. c | NA | — | — | — | 0.5 | 1.6 |

| c.-57G > T | up. c | NA | — | 18.3 | — | 1.1 | 1.3 |

| c.-49T > C | up. c | NA | 16.8 | 69.4 | — | 21.6 | 19.8 |

| c.-46C > A | up. c | NA | — | — | — | 2.7 | 5.5 |

| c.-44C > A | up. c | NA | — | — | — | 12.8 | 20.1 |

| c.-31G > A | up. c | NA | — | 17.4 | — | — | — |

| c.-29G > T | up. c | NA | 12.7 | — | — | 70.3 | 79.5 |

| c.-29G > A | up. c | — | 16.0 | — | — | — | |

| c.-24T > C | up. c | NA | 1.4 | 1.2 | — | — | — |

| c.-19C > T | up. c | NA | 1.9 | 45.0 | — | 0.8 | 1.1 |

| c.-18C > A | up. c | NA | — | 5.7 | — | — | — |

| c.-17C > G | up. c | NA | — | — | — | 12.5 | 12.6 |

| c.-15G > T | up. c | NA | 15.5 | — | — | — | — |

| c.3G > A | c | p.Met1? | — | — | — | 16.9 | 16.4 |

| c.10T > C | c | p.(S4 > P) | — | 20.1 | — | 6.4 | 2.8 |

| c.23C > A | c | p.(A8 > E) | — | 49.9 | — | 0.3 | — |

| c.47G > A | c | p.(G16 > D) | — | 0.3 | — | — | — |

| c.49C > A | c | p.(P17 > T) | — | — | — | 0.2 | — |

| c.70del | c | p.(E28 > Rfs*13) | — | 24.9 | — | — | — |

| c.82G > A | c | p.(G24 > R) | — | — | — | 0.7 | 0.5 |

| c.95G > T | c | p.(S32 > I) | — | — | — | 32.9 | 20.1 |

| c.103A > G | c | p.(K35 > E) | — | 1.0 | — | — | — |

| c.110C > A | c | p.(A37 > E) | — | — | — | 32.0 | 52.3 |

“Gene” and “Function” refer to the name and the general function of the homologous gene in the PA01 reference genome. The predicted effect of the variant on the amino acid sequence is also specified. Variant frequencies are given relative to a control for the combined prophage and replicative form in PA01exp1 day 4 (biofilm), PA01exp1 day 11 (dispersal), PA01exp2 day 4 (biofilm), and PA01exp2 day 11 (dispersal). Additionally, variant frequencies in the free phage harvested at day 11 from PA01exp2 are given. A dash indicates the variant was not detected within the respective sample (limit of detection ∼0.2). c, repressor c gene; up. c, upstream region of the c repressor gene; NA, not applicable.

In the PA01exp2 day 11 and free-phage samples, a SNV within the hypothetical ABC transport-related gene PA0716 (unique to the Pf4 phage genome) was observed. No SNVs were detected from the core Pf4 genome (consisting of replication and assembly genes of the Pf4 phage) or from Pf4’s toxin–antitoxin module and integrase gene. All other Pf4 mutations in both PA01 experiments at day 4 and day 11 were either within or upstream of the c repressor gene (Table 4).

Although it is not possible to distinguish whether Pf4 variant reads from the dispersal samples originated from the integrated prophage or the replicative form, the relative ratio can be established by counting reads covering either the junction of the prophage with the bacterial chromosome or the junction between the two ends of the circular replicative form. Although some replicative form existed in the inoculum and the day 4 biofilm samples for both P. aeruginosa PA01 experiments, there were more than two replicons for each prophage at day 11, indicating active Pf4 genome replication (Table S2). This induction of Pf4 replication also correlated with the free phage particle titer, because phage particles were not detected after 4 d but reached 1010 –1011 pfu/mL by 11 d (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Number of pfus per milliliter of biofilm effluent from P. aeruginosa PA01. Pfus correspond to free phage particles. Note the logarithmic scale for the y-axis.

The longer read lengths used for P. aeruginosa PA01exp2, combined with the colocalization of mutations within or upstream of the c repressor gene made it possible to reconstruct haplotypes for the variable Pf4 region. Haplotype diversity increased dramatically between day 4 and day 11, with the wild-type phage becoming a minor variant (Fig. 4). However, no single clear, mutated haplotype replaced the wild type; rather, a mixture of alternative phage haplotypes coexisted within the population. Most haplotypes from the free phage were also present in similar frequencies in cellular forms of Pf4 at dispersal (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

(Left) Pf4 variable region haplotypes for the P. aeruginosa PA01exp2 samples. Horizontal gray lines represent the Pf4 variable region, 5′ to 3′ on the forward strand. Small colored vertical lines indicate SNVs: red represents T, green represents A, blue represents C, and orange represents G. (Right) A neighbor-joining tree showing pairwise relationships between haplotypes. Frequencies of each haplotype within the relevant sample are given as percentages on the tree leaves. Samples are indicated by color: yellow corresponds to the inoculum, orange to the day 4 biofilm sample, red to the day 11 dispersal sample, and brown to the day 11 free phage sample.

Coalescent analysis of reconstructed phage haplotypes indicated a tree height (last common ancestor) 12 d in the past, consistent with the creation of the overnight culture used for biofilm inoculation. Model comparison using Bayes’ factors (implemented in Tracer v1.5, http://beast.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/tracer/) and Bayesian Monte-Carlo Markov Chain parameter estimation suggested that rapid population growth (exponential expanding growth was selected by model comparison) combined with a fast evolutionary rate of 2.43 × 10−3 (95% CI: 4.37 × 10−4 to 5.42 × 10−3) substitutions per site per day gave rise to the observed haplotypes.

Discussion

Through deep sequencing, we show that short-term diversification (i.e., over ∼5–10 generations) in laboratory-grown bacterial biofilms is driven by selection for a small number of nonsynonymous mutations within key genes involved in biofilm-related pathways. In particular, genes involved in alginate synthesis, cyclic diguanylate (c-di-GMP) signaling, and pili formation exhibited mutations with population frequencies ranging from 0.5 to 98.0%. These findings are consistent with previous work on P. aeruginosa PA01 biofilms, in which dispersal populations featured heritable variants with a wide range of morphological attachment, biofilm formation, and metabolism phenotypes (9).

Variation in Genes for Alginate Synthesis.

Overproduction of alginate (mucoid phenotype) is a signature of isolates from patients with cystic fibrosis (23–26). For the clinical strain P. aeruginosa 18A, reproducible variants were observed targeting genes within the alginate pathway (27–30). These variants are predicted to result in substitutions, deletions, and premature stop codons induced by frameshifts. Changes in the amino acid sequence usually compromise protein function, for instance by altering folding or the active site, and therefore, these variants most likely have impaired alginate production.

P. aeruginosa 18A constitutively produces alginate because of a 1-bp deletion in mucA (31). In the lung, mucoidy facilitates immune evasion and hinders the diffusion of antibiotics (32, 33). However, nonmucoid motile cells within dispersal populations have been observed in laboratory models of lung infection (24) and also in the 18A clinical isolate used here (9). It has been proposed that such variants (which phenotypically resemble attachment-stage cells) facilitate acute infections (9). It also is possible that in the laboratory environment, where resistance to antibiotics and immune attack is unnecessary, mutations in alginate production genes compensate for the mucA mutation. In Pseudomonas fluorescens, a mucoid phenotype arising through phage-driven selection also is lost when selective pressure is removed, indicating alginate production has an associated cost (34).

Variation in Genes for Motility and Attachment.

Mutations in genes affecting motility were also detected in biofilms from both P. aeruginosa strains. AmrZ, in addition to promoting alginate production, also inhibits flagellum synthesis. AmrZ mutants may aid motility and surface attachment by allowing flagellum production (23). P. aeruginosa 18A dispersal populations also displayed mutations in wspF, which encodes a negative regulator of the signaling molecule c-di-GMP. Of the two wspF mutations observed in the dispersal population of 18Aexp1, the first lies within the N-terminal response regulator receiver domain (35), and the second directly affects a site homologous to the CheB methylesterase active site Asp268 (36). The predicted stop codon induced by a wspF mutation in the dispersal population of 18Aexp2 also effectively deletes this active site. Elevated c-di-GMP resulting from wspF deletion has been shown to affect the expression of at least 560 other genes (37), promoting type IV pili and twitching motility, attachment, aggregation, biofilm formation, and wrinkly spreader phenotype (38, 39). Thus, mutations in regulatory genes such as wspF may explain previously observed phenotypes in the dispersal population of P. aeruginosa 18A (31). Wsp operon mutants also have been found in evolving Burkholderia cenocepacia biofilms (40), suggesting that mutations affecting c-di-GMP regulation might be common within biofilm populations.

Genes affecting type IV pili, namely pilT and pilY1, were also disrupted in P. aeruginosa PA01 biofilms, potentially compromising twitching motility. However, the emergence of these variants may be related not only to motility but also to selection caused by phage attack. Between days 4 and 11 of biofilm development, P. aeruginosa PA01's lysogenic phage Pf4 undergoes rapid population growth characterized by multiple mutations within its c repressor gene. In other phages, the c repressor protein maintains the lysogenic lifecycle, with mutations in the c repressor acting as switches leading to the alternative lytic lifecycle (41). It is likely that the mutations observed in the c repressor gene of PA01 also result in a loss of lysogenic control and the induction of lytic growth.

Although not definitively established for Pf4, many filamentous phages, including those associated with P. aeruginosa, use type IV pili for attachment and subsequent infection (42–44). Intriguingly, loss of surface structures such as flagella and pili has been associated with loss of cell death within biofilms; this effect was attributed to failed bacteriophage infection (45). Cells with defective type IV pili therefore may be able to resist lytic phage infection. Interestingly, overexpression of type IV pili has been associated with P. aeruginosa SCVs (46), and SCVs first emerge in P. aeruginosa PA01 biofilms during lytic Pf4 attack, with the biofilm matrix containing high densities of Pf4 phage particles (47). We also observed rising levels of SCVs and Pf4 phage particles between 4 and 11 d of growth, coincident with the increase in type IV pili variants. PilT is involved directly in retraction of pili (48), whereas PilY1 is less well characterized. If the pilT mutations observed here prevent pili retraction, then the phenotype would resemble pili overexpression, with many unretractable pili. Phages may attempt to use these pili, but without their retraction phage particles cannot infect the cell, resulting in selection for unretractable pili as a mode of phage resistance. Finally, Pf4-mediated selection for unretractable pili could explain the phage’s contribution to P. aeruginosa PA01’s virulence (47); such cells are known to be sticky, easily attaching to surfaces and forming dense biofilms (49).

Although P. aeruginosa 18A contains a phage resembling Pf4, no increases in phage population or c repressor mutants were observed. Inspection of the P. aeruginosa 18A genome revealed that the c repressor gene of its phage is truncated, explaining the lack of c repressor mutants in this strain.

Pf4 Bacteriophage Evolution.

Our study revealed very rapid evolution of the ssDNA bacteriophage Pf4. Between inoculation and biofilm dispersal, multiple c repressor haplotypes emerged, often featuring multiple mutations within each haplotype. The inferred rate of 2.43 × 10−3 substitutions per site per day is difficult to compare with published rates, because it is measured over a time course of days rather than years. Also, no SNVs reached fixation. Therefore, this measurement really is a hybrid between the mutation rate and the substitution rate, best thought of as an indication of evolutionary rate in response to an individual selective event. The value observed here thus represents a lower boundary for the mutation rate and an upper boundary for the substitution rate. However, this rate is comparable with the hepatitis C virus evolutionary rate of 9.69 × 10−4 established by Bull et al. (15). RNA viruses are well known for their high mutation and substitution rates and their ability to evolve rapidly under selective pressures. The ssDNA Pf4 bacteriophage appears to have the potential for equally rapid or even faster evolution. This finding is consistent with emerging evidence suggesting ssDNA viruses may evolve at rates approaching rapidly mutating RNA viruses (50).

Genetic Diversification in Biofilms.

It has been suggested that diversification of clinical P. aeruginosa isolates results from elevated mutation rates, i.e., hypermutation (13). Although hypermutable P. aeruginosa strains do exist (51), the 18A clinical strain is not a hypermutator. Its mutation rate as measured by fluctuation tests is equivalent to or even lower than that of PA01. Both strains also lack known hypermutator-inducing mutations.

Biofilm diversification has also been suggested to result from the spatial microcolony structure of the biofilm. Specific hypothesized mechanisms include selection for mutations that are advantageous for microcolony formation, local elevated mutation rates within individual microcolonies, or nonselective expansion of individual microcolony-founding clones (12). For the latter two hypotheses, a large number of low-frequency variants are expected that are not evident in our results. It is possible that such variation still exists but occurs at a frequency below our detection limit. As deep sequencing improves, it will be interesting to see if large quantities of very-low-frequency variants exist. Nonetheless, actual observations support the former hypothesis, indicating short-term biofilm diversification results from diversifying selection, with adaptive processes acting on a small number of biofilm-related pathways and regulatory genes.

Adaptive Processes and Parallel Evolution.

In their review of whole-genome sequencing as applied to microbial experimental evolution, Dettman et al. (5) stress the need to sequence entire populations over short time spans to reveal details of the adaptive process. Our analysis of developing biofilms meets this need, providing insights into the incidence and nature of parallel evolution; the type, number, and time scale of mutations underlying adaptive evolution; and the types of genes or pathways able to respond to selection.

Parallel evolution was observed at the level of pathways, genes, and individual point mutations for both the clinical P. aeruginosa strain 18A and the laboratory type strain PA01. Parallel evolution also was observed in P. aeruginosa PA01’s bacteriophage Pf4, often involving identical nucleotides. Parallel evolution at the nucleotide level is a striking finding of this study, because the literature to date suggests that this is a rare event, at least for bacteria (5).

Parallel evolution is a hallmark of positive selection, indicating that positive selection is the predominant evolutionary force shaping genetic diversity during biofilm formation. A conspicuous lack of silent mutations supports this hypothesis. In general, the targeted pathways for each strain reflect its natural history and current selective pressures: For 18A, constitutive production of alginate previously provided a competitive advantage within the harsh lung environment, but mutations inhibiting production of this potentially costly secreted compound are selected for in the laboratory. In contrast, PA01 responds to strong selective pressure exerted by phage attack by rapidly changing its surface attachment structures, possibly decreasing superinfection.

This finding of positive selection is consistent with previous analyses of P. aeruginosa evolution during chronic infection, which is characterized by a high proportion of nonsynonymous mutations in specific virulence-related genes (52). Interestingly, the opposite result was found in a recent analysis of Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage. Within-host evolution during asymptomatic infection was characterized by negative selection, with an abundance of synonymous mutations (53). The differing evolutionary trajectories between P. aeruginosa and S. aureus may result from different levels of adaptation to the host; S. aureus presumably is well adapted to the nasal cavity during asymptomatic carriage and transmission. In contrast, P. aeruginosa strains initiating new opportunistic infections are not necessarily preadapted to the lung environment. Previous adaptation to an existing niche was shown to limit selective diversification in experimental P. fluorescens populations (54), lending weight to this explanation.

Different levels of preadaptation to the laboratory environment also may explain the greater number of variants observed in P. aeruginosa 18A than in PA01. PA01 is the type strain and thus has undergone extensive passaging within laboratories. In contrast, 18A is a clinical isolate adapted to the human lung environment. The larger population size for PA01 after attachment and during biofilm development (Fig. 1) may also reflect better adaptation to the laboratory environment. This possibility also is suggested by the most strongly selected 18A mutation (mreD 48A > G) matching the wild-type PA01 variant. Therefore, diversifying selection may be limited by a lack of potential adaptive mutations for PA01.

Remarkably, most mutations caused large increases in fitness, as indicated by large Malthusian selection coefficients. The mean selection coefficient for positively selected variants in our study was 0.83 for 18A and 2.69 for PA01, which is high compared with experimental findings from Escherichia coli [in which the mean selection coefficient was 0.02 (55)]. However, the E. coli experiment involved serial passaging in rich LB medium; thus the population already may have been close to its fitness peak. In this scenario, the fitness effects of individual mutations can only be small. It also is true that the small number of generations observed in our study limits our ability to identify adaptive mutations of small effect, because their population frequencies change slowly. Nevertheless, our results conclusively show that when selection is strong enough, mutations with large fitness effects can occur.

The absence of detectable mutations in noncoding regions and the low number of synonymous mutations detected is a striking finding of our study. The observed time scale may be too short to allow neutral mutations to drift to detectable frequencies. Alternatively, truly neutral mutations may be rare. Of the two synonymous mutations identified in the bacterial chromosome of P. aeruginosa 18A, the one in mreD is highly unlikely to be silent, because in both replicates it rapidly rises to a population frequency of more than 80% within 4 d of biofilm growth. Codon use analysis indicated this mutation may lead to increased translation efficiency. In E. coli, MreD is a cell membrane-associated protein required for rod shape formation (56). In Streptococcus pneumoniae, depletion of MreD results in cell rounding and lysis (57). Elevated MreD therefore may alter cell-surface properties, possibly aiding attachment in the early stages of biofilm formation. If so, the rapid rise of this variant could be explained by a strong selective sweep resulting from the initial surface attachment of a subset of cells following inoculation. The other potentially neutral mutation in yrbE may have hitchhiked to its population frequency of around 40% because of its relatively close proximity (23,201 bp) to mreD. However, it is surprising that there is only one potential example in our data of a neutral mutation hitchhiking to a detectable frequency by being in linkage disequilibrium with a neighboring, positively selected mutation. This observation could result from conserved genes having lower mutation rates, limiting the supply of neutral mutations. Although the examples of nucleotide-level parallel evolution observed here suggest that mutation supply is unlikely to be a limiting factor, highly conserved E. coli genes have mutation rates up to an order of magnitude lower than those of other genes (58). In any case, whether purifying selection is driving the evolution of lower mutation rates in conserved genes or simply purging most mutations from the genome, the majority of the P. aeruginosa genome appears to be conserved by negative selection during biofilm growth.

In summary, our findings indicate that P. aeruginosa features a subset of genes able to evolve quickly in response to environmental change within an otherwise conserved genome. Predictably, these genes facilitate interaction with the environment, for example through the production of alginate, surface-associated motility proteins, or regulatory proteins. Adaptation within these genes proceeds via a few nonsynonymous mutations under strong selection, possibly by controlling genes and/or pathways in a switch-like fashion, leading to diversifying selection. It has been shown previously that few, positively selected, nonsynonymous mutations typify the end point of long-term experimental evolution in bacteria (5); our results show that similar dynamics govern adaptation over a time course of days.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Design and Sequencing.

Samples from the 4-d-old biofilm and from the dispersal population at day 11 were harvested, and bacterial and phage DNA was extracted (further details are given in SI Materials and Methods). Samples from two independent biofilms of P. aeruginosa PA01 (PA01exp1 and PA01exp2) and two independent biofilms of P. aeruginosa 18A (18Aexp1 and 18Aexp2) were sequenced. The inoculum cultures for both P. aeruginosa PA01 biofilms also were sequenced as controls. For the P. aeruginosa 18A biofilms, an overnight planktonic culture was sequenced as a control. Data from the planktonic P. aeruginosa 18A samples were also used to generate a draft genome assembly (European Molecular Biology Laboratory accession nos. CAQZ01000001–CAQZ01000179) (31). All sequencing was performed by the Ramaciotti Centre for Functional Gene Analysis (University of New South Wales, Sydney) using Illumina sequencing technology. Table S1 details all the samples and sequencing performed in this study.

The colony-forming unit counts from serial dilutions of nine independent biofilms were used to construct biofilm growth curves for each strain. Initial population sizes after inoculation were inferred by fitting an exponential growth model to the first three time points. See SI Materials and Methods for full details.

Variant Analysis.

To identify variants, sequencing reads were first aligned to a reference genome (see SI Materials and Methods for details on reference genomes) using Novocraft V2.07.06 default parameters with the following exceptions: Penalties associated with initiating and extending gaps were reduced to 35 and 10, respectively, to allow discovery of small indels; and full Needleman–Wunsch alignment along the length of the read was enabled (disabling soft clipping).

SNVs were called using the R package deepSNV v1.2.3 (19) with default parameters, which performs a statistical test for each potential SNV position, comparing the frequency of each potential SNV in the sample of interest with the frequency of the SNV in a control sample. Biofilm inoculum cultures were used as controls for the PA01 experiments. For the 18A experiments, an overnight culture generated from the same stocks and under the same conditions as the inoculation cultures was used as a control. SNVs with frequencies that are significantly different from the control frequency and that are identified in at least 10 reads are considered to be true by deepSNV. Initial results suggested that P values assigned by deepSNV may be too conservative, possibly because of the correction for multiple testing, given the very large number of sites contained within a bacterial genome. Therefore, all potential SNVs with a P value less than one were retained and were then checked manually. For an SNV to be retained during manual checks, it must be covered by at least one read in each direction. The fraction of forward reads harboring the SNV must also be within 10% of the overall fraction of forward reads at the SNV position (i.e., the SNV must not show a strand bias).

More variants were observed in P. aeruginosa 18A samples than in P. aeruginosa PA01 samples. To ensure that this difference was not the result of spurious calls caused by the lower read depth for 18A, we subsampled all data sets to an average read depth of 680× using Samtool, and then reran the deepSNV analysis. Although, as expected, SNVs with very low frequencies were not retained for either strain, P. aeruginosa 18A still displayed greater genetic diversity than PA01. Furthermore, no additional SNVs were identified for P. aeruginosa PA01, suggesting that lower coverage does not result in false-positive SNV calls.

The percentage of small-colony morphotypic variants in PA01exp1 and PA01exp2 biofilm effluent was also determined experimentally by plating serially diluted cultures onto LB10 agar (see SI Materials and Methods for further details).

Variants in Tables 1, 2, and 4 and Tables S3 and S4 are given according to the nomenclature of the Human Genome Variation Society (HGVS). Malthusian selection coefficients were calculated with respect to the number of bacterial generations according to the method in ref. 55. See SI Materials and Methods for further information.

Phage Analysis and Haplotype Construction.

Free phage DNA was subjected to paired-end sequencing (Table S1), with an average fragment size of 230 bp and a read length of 150 nt. Forward and reverse reads were merged using FLASH v1.0.2 (59). Simulation with GemSIM v1.5 (60) indicated that, with a minimum overlap of 50 nt and allowing no errors to occur within the overlap, 70% of reads matched the reference sequence exactly (i.e., contained no errors), and 99.9% of reads were reconstructed accurately in terms of fragment length (inspection of reconstructed fragments with deviations from the known fragment length indicated that repeat regions were responsible for those few fragments with incorrect reassembly). Therefore, these parameters were chosen for fragment reconstruction, resulting in the recovery of 10,085,099 reconstructed reads. Because Novoalign does not handle reads with lengths greater than 150 nt, reconstructed reads were aligned against the prophage region of the reference PA01 genome using Burrows–Wheeler Aligner v. 0.6.1-r104 (61), with the bwasw command and default settings. SNVs were called as described above, with PA01exp2 inoculum reads aligned to the prophage used as a control.

PA01exp2 prophage haplotypes corresponding to positions 788,784–788,955 in the P. aeruginosa reference genome and haplotypes for the free phage sample were reconstructed using ShoRAH v0.6 (62). For the bacterial population samples, a window size of 144 nt was used, whereas for the free phage samples, the merged reads allowed the use of a window size of 218 nt. For all samples, coverage was limited to 10,000; α and σ were set to 0.01; with the number of window shifts set to three. To account for stochastic variation, three ShoRAH runs were performed for each sample. Only haplotypes occurring in all three runs with average frequency greater than 1% were reported. Visualization of haplotypes, including construction of a neighbor-joining tree, was performed using Highlighter v2.1.1 (www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/sequence/HIGHLIGHT/HIGHLIGHT_XYPLOT/highlighter.html).

The ratio of replicative phage to prophage in inoculum, biofilm, and dispersal samples was calculated by counting the number of occurrences of the sequences CACCCAACACCGCTGACGGCGCTAGCGGCGGT (replicative phage) and CACCCAACACCGCTGAATGAAGGCGAAACAGC (prophage) in the forward reads for the P. aeruginosa samples. These sequences correspond to the 16 nt before and after either the circularization junction (replicative phage) or the 5′ prophage integration junction on the forward strand of the published P. aeruginosa PA01 reference.

The titer of free phage was also determined experimentally using a modified version of the top-layer agar method previously described in ref. 63 (see SI Materials and Methods for further details).

Coalescent Analysis.

Coalescent analysis of aligned sequences was performed with Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees (BEAST), which employs Bayesian Monte-Carlo Markov Chain analysis to calculate parameters such as the substitution rate and the time since the last common ancestor, facilitating comparison of evolutionary hypotheses (64). Several analyses were performed using BEAST v1.7.2, testing various hypotheses including exponential, exponential expanding, and logarithmic population growth. A skyline analysis also was performed, in which the shape of population growth is inferred from the data. Haplotype reconstruction using ShoRAH essentially collapses identical sequences into one haplotype; because this practice can induce BEAST to estimate inflated population sizes, we included multiple copies of each haplotype, with the copy number equal to the estimated population frequency of the haplotype (for example, a haplotype estimated to be present in 30% of the population, would have a copy number of 30). The number of iterations for each BEAST run was set to 100,000,000 with parameter values reported every 10,000 iterations. Analysis of BEAST log files and comparison of models was performed in Tracer v1.5 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/tracer/).

Fluctuation Tests.

To establish whether P. aeruginosa 18A is a hypermutator, Luria–Delbrück fluctuation tests were performed (65). An experimental design process as previously outlined was followed (66). Initial tests indicated 15 parallel cultures would be sufficient when combined with the Ma–Sandri–Sarkar maximum-likelihood estimator method. Dilutions from 15 overnight cultures of P. aeruginosa 18A, P. aeruginosa PA01, and E. coli K12 (a control to compare with published mutation rates) were plated onto LB plates both with and without rifampicin. Counts were used to establish the rate of rifampicin-resistance mutation using the FALCOR software (67). Rifampicin resistance is conferred by mutations in the rpoB gene; the individual point mutations leading to resistance have been cataloged extensively (68). This information was used to convert the rifampicin resistance rate to a per base mutation rate.

Gene Analyses.

To identify P. aeruginosa 18A genes featuring variants and to compare them with PA01 versions of each gene, the relevant ORFs were searched with BLAST against the published P. aeruginosa PA01 genome using the Pseudomonas genome database (69). The 18A mucA and mutS genes were also compared with the PA01 version to screen for known alginate and hypermutator mutations, respectively. For silent mutations, RSCU analysis was undertaken. RSCU is defined as the ratio of the observed codon frequency to the expected codon frequency, if synonymous codons are used equally. Codon use for individual genes was calculated using the Sequence Manipulation Suite (www.bioinformatics.org/sms2/codon_usage.html). RSCU for P. aeruginosa PA01 was taken from the literature (70).

Data Access.

Sequence reads have been deposited in the BioSample database under accession numbers SAMN02191672– SAMN02191683.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Fabio Luciani for discussions regarding the BEAST analysis. This work was supported by the Australian Cystic Fibrosis Research Trust.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The sequence reads reported in this paper have been deposited in the BioSample database (accession nos. SAMN02191672–SAMN02191683).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1314340111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Shea PR, et al. Distinct signatures of diversifying selection revealed by genome analysis of respiratory tract and invasive bacterial populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(12):5039–5044. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016282108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rainey PB, Travisano M. Adaptive radiation in a heterogeneous environment. Nature. 1998;394(6688):69–72. doi: 10.1038/27900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koh KS, et al. Minimal increase in genetic diversity enhances predation resistance. Mol Ecol. 2012;21(7):1741–1753. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osório NS, et al. Evidence for diversifying selection in a set of Mycobacterium tuberculosis genes in response to antibiotic- and nonantibiotic-related pressure. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(6):1326–1336. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dettman JR, et al. Evolutionary insight from whole-genome sequencing of experimentally evolved microbes. Mol Ecol. 2012;21(9):2058–2077. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rybtke MT, et al. The implication of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms in infections. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2011;10(2):141–157. doi: 10.2174/187152811794776222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Høiby N, Bjarnsholt T, Givskov M, Molin S, Ciofu O. Antibiotic resistance of bacterial biofilms. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010;35(4):322–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drenkard E, Ausubel FM. Pseudomonas biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance are linked to phenotypic variation. Nature. 2002;416(6882):740–743. doi: 10.1038/416740a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woo JK, Webb JS, Kirov SM, Kjelleberg S, Rice SA. Biofilm dispersal cells of a cystic fibrosis Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolate exhibit variability in functional traits likely to contribute to persistent infection. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2012;66(2):251–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2012.01006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boles BR, Thoendel M, Singh PK. Self-generated diversity produces “insurance effects” in biofilm communities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(47):16630–16635. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407460101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall-Stoodley L, Costerton JW, Stoodley P. Bacterial biofilms: From the natural environment to infectious diseases. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2(2):95–108. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conibear TC, Collins SL, Webb JS. Role of mutation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(7):e6289. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oliver A, Mena A. Bacterial hypermutation in cystic fibrosis, not only for antibiotic resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16(7):798–808. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beerenwinkel N, Günthard HF, Roth V, Metzner KJ. Challenges and opportunities in estimating viral genetic diversity from next-generation sequencing data. Front Microbiol. 2012;3:329. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bull RA, et al. Sequential bottlenecks drive viral evolution in early acute hepatitis C virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(9):e1002243. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tyson GW, et al. Community structure and metabolism through reconstruction of microbial genomes from the environment. Nature. 2004;428(6978):37–43. doi: 10.1038/nature02340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morowitz MJ, et al. Strain-resolved community genomic analysis of gut microbial colonization in a premature infant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(3):1128–1133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010992108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drake JW. A constant rate of spontaneous mutation in DNA-based microbes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88(16):7160–7164. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerstung M, et al. Reliable detection of subclonal single-nucleotide variants in tumour cell populations. Nat Commun. 2012;3:811. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sørensen MA, Kurland CG, Pedersen S. Codon usage determines translation rate in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1989;207(2):365–377. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90260-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barrick JE, et al. Genome evolution and adaptation in a long-term experiment with Escherichia coli. Nature. 2009;461(7268):1243–1247. doi: 10.1038/nature08480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Webb JS, Lau M, Kjelleberg S. Bacteriophage and phenotypic variation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. J Bacteriol. 2004;186(23):8066–8073. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.23.8066-8073.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Toole GA, Kolter R. Flagellar and twitching motility are necessary for Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30(2):295–304. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sauer K, Camper AK, Ehrlich GD, Costerton JW, Davies DG. Pseudomonas aeruginosa displays multiple phenotypes during development as a biofilm. J Bacteriol. 2002;184(4):1140–1154. doi: 10.1128/jb.184.4.1140-1154.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harmsen M, Yang L, Pamp SJ, Tolker-Nielsen T. An update on Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation, tolerance, and dispersal. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2010;59(3):253–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2010.00690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramsey DM, Wozniak DJ. Understanding the control of Pseudomonas aeruginosa alginate synthesis and the prospects for management of chronic infections in cystic fibrosis. Mol Microbiol. 2005;56(2):309–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wozniak DJ, Ohman DE. Pseudomonas aeruginosa AlgB, a two-component response regulator of the NtrC family, is required for algD transcription. J Bacteriol. 1991;173(4):1406–1413. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.4.1406-1413.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wozniak DJ, Sprinkle AB, Baynham PJ. Control of Pseudomonas aeruginosa algZ expression by the alternative sigma factor AlgT. J Bacteriol. 2003;185(24):7297–7300. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.24.7297-7300.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garrett ES, Perlegas D, Wozniak DJ. Negative control of flagellum synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is modulated by the alternative sigma factor AlgT (AlgU) J Bacteriol. 1999;181(23):7401–7404. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.23.7401-7404.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qiu D, Eisinger VM, Head NE, Pier GB, Yu HD. ClpXP proteases positively regulate alginate overexpression and mucoid conversion in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology. 2008;154(Pt 7):2119–2130. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/017368-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woo JK, et al. Draft genome sequence of the chronic, nonclonal cystic fibrosis isolate Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain 18A. Genome Announc. 2013;1(2):e0000113. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00001-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kharazmi A. Mechanisms involved in the evasion of the host defence by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Immunol Lett. 1991;30(2):201–205. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(91)90026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leid JG, et al. The exopolysaccharide alginate protects Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm bacteria from IFN-gamma-mediated macrophage killing. J Immunol. 2005;175(11):7512–7518. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scanlan PD, Buckling A. Co-evolution with lytic phage selects for the mucoid phenotype of Pseudomonas fluorescens SBW25. ISME J. 2012;6(6):1148–1158. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Djordjevic S, Goudreau PN, Xu Q, Stock AM, West AH. Structural basis for methylesterase CheB regulation by a phosphorylation-activated domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(4):1381–1386. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Falke JJ, Bass RB, Butler SL, Chervitz SA, Danielson MA. The two-component signaling pathway of bacterial chemotaxis: A molecular view of signal transduction by receptors, kinases, and adaptation enzymes. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:457–512. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hickman JW, Tifrea DF, Harwood CS. A chemosensory system that regulates biofilm formation through modulation of cyclic diguanylate levels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(40):14422–14427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507170102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bantinaki E, et al. Adaptive divergence in experimental populations of Pseudomonas fluorescens. III. Mutational origins of wrinkly spreader diversity. Genetics. 2007;176(1):441–453. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.069906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jain R, Behrens AJ, Kaever V, Kazmierczak BI. Type IV pilus assembly in Pseudomonas aeruginosa over a broad range of cyclic di-GMP concentrations. J Bacteriol. 2012;194(16):4285–4294. doi: 10.1128/JB.00803-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Traverse CC, Mayo-Smith LM, Poltak SR, Cooper VS. Tangled bank of experimentally evolved Burkholderia biofilms reflects selection during chronic infections. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(3):E250–E259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207025110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salmon KA, Freedman O, Ritchings BW, DuBow MS. Characterization of the lysogenic repressor (c) gene of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa transposable bacteriophage D3112. Virology. 2000;272(1):85–97. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roncero C, Darzins A, Casadaban MJ. Pseudomonas aeruginosa transposable bacteriophages D3112 and B3 require pili and surface growth for adsorption. J Bacteriol. 1990;172(4):1899–1904. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.4.1899-1904.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chibeu A, et al. The adsorption of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteriophage phiKMV is dependent on expression regulation of type IV pili genes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2009;296(2):210–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim S, Rahman M, Kim J. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa lytic bacteriophage PA1O which resembles temperate bacteriophage D3112. J Virol. 2012;86(6):3400–3401. doi: 10.1128/JVI.07191-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Webb JS, et al. Cell death in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. J Bacteriol. 2003;185(15):4585–4592. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.15.4585-4592.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Häussler S, et al. Highly adherent small-colony variants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis lung infection. J Med Microbiol. 2003;52(Pt 4):295–301. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.05069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rice SA, et al. The biofilm life cycle and virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa are dependent on a filamentous prophage. ISME J. 2009;3(3):271–282. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2008.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mattick JS. Type IV pili and twitching motility. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2002;56:289–314. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.56.012302.160938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chiang P, Burrows LL. Biofilm formation by hyperpiliated mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 2003;185(7):2374–2378. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.7.2374-2378.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Duffy S, Shackelton LA, Holmes EC. Rates of evolutionary change in viruses: Patterns and determinants. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9(4):267–276. doi: 10.1038/nrg2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mena A, et al. Genetic adaptation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to the airways of cystic fibrosis patients is catalyzed by hypermutation. J Bacteriol. 2008;190(24):7910–7917. doi: 10.1128/JB.01147-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith EE, et al. Genetic adaptation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa to the airways of cystic fibrosis patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(22):8487–8492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602138103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Golubchik T, et al. Within-host evolution of Staphylococcus aureus during asymptomatic carriage. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5):e61319. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Buckling A, Wills MA, Colegrave N. Adaptation limits diversification of experimental bacterial populations. Science. 2003;302(5653):2107–2109. doi: 10.1126/science.1088848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Imhof M, Schlotterer C. Fitness effects of advantageous mutations in evolving Escherichia coli populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(3):1113–1117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.3.1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kruse T, Bork-Jensen J, Gerdes K. The morphogenetic MreBCD proteins of Escherichia coli form an essential membrane-bound complex. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55(1):78–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Land AD, Winkler ME. The requirement for pneumococcal MreC and MreD is relieved by inactivation of the gene encoding PBP1a. J Bacteriol. 2011;193(16):4166–4179. doi: 10.1128/JB.05245-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martincorena I, Seshasayee AS, Luscombe NM. Evidence of non-random mutation rates suggests an evolutionary risk management strategy. Nature. 2012;485(7396):95–98. doi: 10.1038/nature10995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Magoč T, Salzberg SL. FLASH: Fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(21):2957–2963. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McElroy KE, Luciani F, Thomas T. GemSIM: General, error-model based simulator of next-generation sequencing data. BMC Genomics. 2012;13(74):74. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(5):589–595. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zagordi O, Bhattacharya A, Eriksson N, Beerenwinkel N. ShoRAH: Estimating the genetic diversity of a mixed sample from next-generation sequencing data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Eisenstark A. Bacteriophage Techniques: Methods in Virology. New York: Academic; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Drummond AJ, Suchard MA, Xie D, Rambaut A. Bayesian phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST 1.7. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29(8):1969–1973. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Luria SE, Delbrück M. Mutations of Bacteria from Virus Sensitivity to Virus Resistance. Genetics. 1943;28(6):491–511. doi: 10.1093/genetics/28.6.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rosche WA, Foster PL. Determining mutation rates in bacterial populations. Methods. 2000;20(1):4–17. doi: 10.1006/meth.1999.0901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hall BM, Ma CX, Liang P, Singh KK. Fluctuation analysis CalculatOR: A web tool for the determination of mutation rate using Luria-Delbruck fluctuation analysis. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(12):1564–1565. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jin DJ, Gross CA. Mapping and sequencing of mutations in the Escherichia coli rpoB gene that lead to rifampicin resistance. J Mol Biol. 1988;202(1):45–58. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90517-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Winsor GL, et al. Pseudomonas Genome Database: Improved comparative analysis and population genomics capability for Pseudomonas genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(Database issue):D596–D600. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Grocock RJ, Sharp PM. Synonymous codon usage in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01. Gene. 2002;289(1-2):131–139. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)00503-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.