Significance

Recognizing predators and judging the level of threat that they pose is a crucial skill for many wild animals. Human predators present a particularly interesting challenge, as different groups of humans can represent dramatically different levels of danger to animals living around them. We used playbacks of human voice stimuli to show that elephants can make subtle distinctions between language and voice characteristics to correctly identify the most threatening individuals on the basis of their ethnicity, gender, and age. Our study provides the first detailed assessment of human voice discrimination in a wild population of large-brained, long-lived mammals, and highlights the potential benefits of sophisticated mechanisms for distinguishing different subcategories within a single predator species.

Keywords: animal cognition, communication, social behavior, predator recognition, vocalization

Abstract

Animals can accrue direct fitness benefits by accurately classifying predatory threat according to the species of predator and the magnitude of risk associated with an encounter. Human predators present a particularly interesting cognitive challenge, as it is typically the case that different human subgroups pose radically different levels of danger to animals living around them. Although a number of prey species have proved able to discriminate between certain human categories on the basis of visual and olfactory cues, vocalizations potentially provide a much richer source of information. We now use controlled playback experiments to investigate whether family groups of free-ranging African elephants (Loxodonta africana) in Amboseli National Park, Kenya can use acoustic characteristics of speech to make functionally relevant distinctions between human subcategories differing not only in ethnicity but also in sex and age. Our results demonstrate that elephants can reliably discriminate between two different ethnic groups that differ in the level of threat they represent, significantly increasing their probability of defensive bunching and investigative smelling following playbacks of Maasai voices. Moreover, these responses were specific to the sex and age of Maasai presented, with the voices of Maasai women and boys, subcategories that would generally pose little threat, significantly less likely to produce these behavioral responses. Considering the long history and often pervasive predatory threat associated with humans across the globe, it is likely that abilities to precisely identify dangerous subcategories of humans on the basis of subtle voice characteristics could have been selected for in other cognitively advanced animal species.

The ability to recognize predators and assess the level of threat that they pose is a crucial cognitive skill for many wild animals that has very direct and obvious fitness consequences (1–5). Until recently, most research in this area focused on how a range of birds and mammals classify other animal predators, demonstrating complex abilities to differentiate between predators with different hunting styles and respond with appropriate escape tactics (2, 3, 6–8). However, for many wild populations, humans represent a significant predatory threat (5, 9, 10) and this threat is rapidly increasing as areas for wildlife decrease and human–animal conflict grows. Moreover, as it is typically the case that not all humans pose the same risk to prey species, distinguishing between different human subgroups to identify those associated with genuinely threatening situations could present a major cognitive challenge. The extent of behavioral flexibility that different species may exhibit in correctly classifying human predators—and the degree of sophistication possible in such abilities—is therefore of considerable interest.

Most research on the abilities of animals to classify human predators has focused on discrimination through facial features or general differences in behavior and appearance (5, 11–13). This focus has demonstrated that a number of different species are able to use visual cues to distinguish between individual humans that present varying levels of threat (4, 5, 14–16). However, acoustic cues could potentially provide a more effective means of classifying human predators by virtue of enabling categories of particularly dangerous humans to be identified. Such cues have an advantage because they code information on sex and age as well as cultural divisions that may be associated with differing levels of predation risk. Furthermore, these cues are available when the predator is still out of sight, potentially providing an important early warning system. Until now, however, studies of animal responses to human voices have focused on demonstrating skills in recognizing individual humans (17–21) rather than investigating specific abilities to identify particular human subgroups that have functional relevance in the natural environment.

African elephants present an ideal model for a study of this nature, as humans constitute their most significant predator other than lions (1) and different human subgroups present them with different threats. African elephants are also already known to make broad distinctions between human ethnic groups on the basis of visual and olfactory cues (15). In the Amboseli ecosystem in Kenya, Maasai pastoralists periodically come into conflict with elephants over access to water and grazing for their cattle, and this sometimes results in elephants being speared, particularly in retaliation when Maasai lives have been lost (15, 22). In contrast, Kamba men, with more agricultural lifestyles, do not typically pose a significant threat to elephants within the National Park, and where conflict occurs outside over crop raiding, this largely involves male rather than female elephants (see, for example, ref. 23). Previous research has demonstrated that elephant family groups exhibit greater fear-based reactions to the scent of garments previously worn by Maasai men than Kamba men and also show aggression to presentations of the red clothes that Maasai typically wear (15). However, experiments involving presentations of human artifacts are inevitably limited in the level of natural variation that they can realistically simulate, whereas playback of human voice stimuli offers the possibility of investigating abilities to make a much wider range of functionally important distinctions. The extent to which elephants can use human voice cues to determine not only ethnicity, but also finer-scaled differences in sex and age that can dramatically affect predation risk, is highly relevant not only for determining the cognitive abilities that underlie predator recognition but also for understanding the coevolution of humans and arguably their most cognitively advanced prey.

We used controlled playback experiments to investigate whether elephant family groups in Amboseli National Park were able to make subtle distinctions between the varying levels of threat posed by different categories of human. Although the presence of Maasai typically represents the greatest threat, this is specific to Maasai men because Maasai women are not involved in elephant-spearing events (22). We were able to compare behavioral responses of 48 female family groups not only to a large sample of voice stimuli from adult Maasai men versus Kamba men saying “Look, look over there, a group of elephants is coming” in their own language, but also to Maasai men versus Maasai women giving this utterance. In this latter experiment we used both natural stimuli and stimuli that had been resynthesized to mimic sex differences while keeping other acoustic characteristics of the voice unchanged. In a final experiment, we contrasted elephant responses given to the voices of Maasai men versus Maasai boys (see Materials and Methods for details).

Results

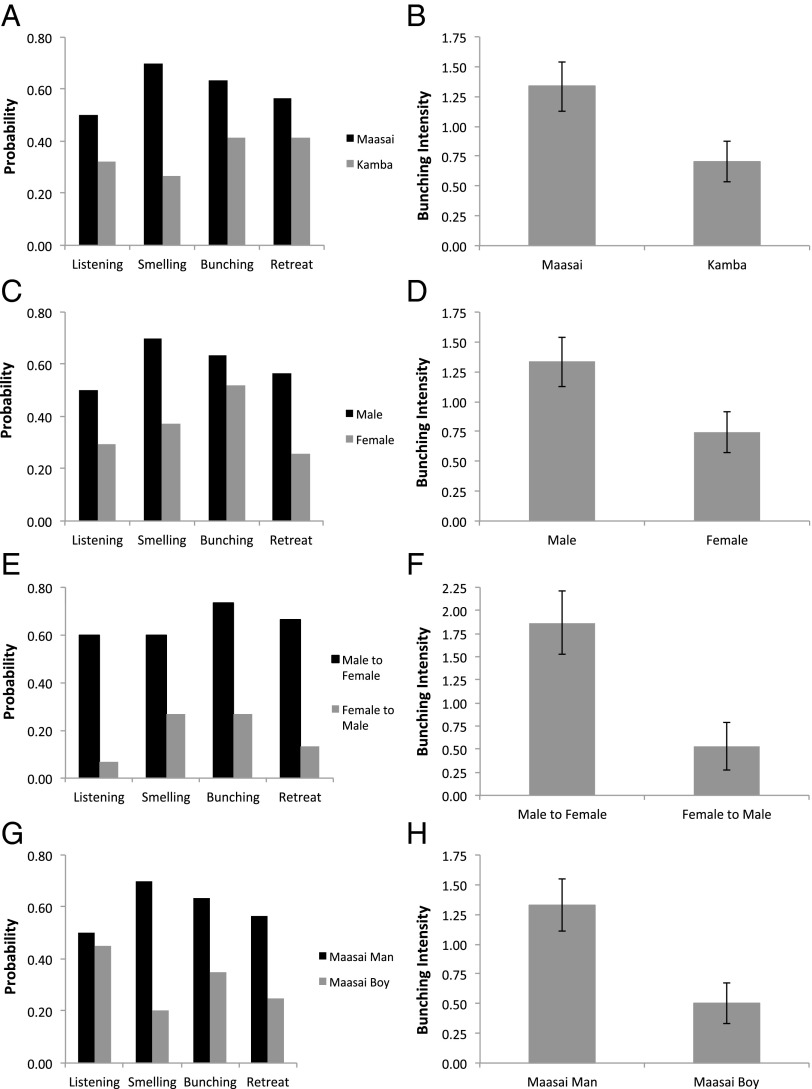

Behavioral responses to playback were classified on the basis of key reactions to threat identified in our previous research (1, 24), including whether listening after playback was prolonged, occurrence of investigative smelling, occurrence and extent of bunching into defensive formation, and occurrence of retreat away from playback (Materials and Methods). Elephant family groups demonstrated pronounced differences in defensive bunching and investigative smelling when presented with playbacks of male Maasai speakers compared with male Kamba speakers, with these behaviors significantly more likely to be observed after Maasai playbacks (Fig. 1A, Table 1, and Table S1) and greater mean bunching intensities occurring in such circumstances (Fig. 1B, Table 1, and Table S1). There were no significant differences in the probability of prolonged listening and retreat after playback. It was very notable that approach behavior, which had been a common response of elephants when they were mobbing playbacks of lions roaring in our previous work (1), was very rarely observed in response to playbacks of human voices (occurring only once during our 32 Maasai male playbacks).

Fig. 1.

Behavioral responses of elephant family groups to playbacks of human voices: Maasai male vs. Kamba male (A and B), Maasai male vs. Maasai female (C and D), resynthesized Maasai male vs. resynthesized Maasai female (E and F), and Maasi male vs. Maasai boy (G and H). Behavioral responses were measured as probability of bunching (A, C, E, and G) and mean (± SEM) bunching intensity (B, D, F, and H).

Table 1.

The relationship between each of the response variables and the model-averaged parameters (β-estimate ± 95% confidence interval)

| Response variables | Human voice | Age of matriarch | Human voice × age of matriarch |

| Maasai vs. Kamba | |||

| Bunch | 1.09 (0.00/2.18) | −0.05 (−0.12/0.02) | 0.00 (−0.14/0.13) |

| Bunch intensity | 0.66 (0.14/1.17) | −0.04 (−0.07/-0.01) | 0.01 (−0.06/0.07) |

| Listening | 0.93 (−0.22/2.08) | −0.05 (−0.13/0.03) | −0.04 (−0.18/0.1) |

| Smelling | 1.88 (0.78/2.98) | 0.05 (−0.02/0.12) | 0.01 (−0.12/0.15) |

| Retreat | 0.78 (−0.29/1.85) | −0.02 (−0.1/0.05) | 0.03 (−0.09/0.16) |

| Male vs. female | |||

| Bunch | 0.67 (−0.54/1.87) | −0.07 (−0.15/0.01) | 0.04 (−0.11/0.19) |

| Bunch intensity | 0.69 (0.11/1.26) | −0.04 (−0.08/-0.01) | 0.01 (−0.06/0.08) |

| Listening | 1.14 (−0.08/2.36) | −0.04 (−0.13/0.04) | −0.09 (−0.25/0.07) |

| Smelling | 1.47 (0.29/2.65) | 0.06 (−0.01/0.14) | 0.00 (−0.15/0.15) |

| Retreat | 1.67 (0.38/2.96) | 0.00 (−0.09/0.09) | −0.05 (−0.21/0.11) |

| Resynthesized | |||

| Bunch | 2.02 (0.40/3.64) | 0.01 (−0.10/0.12) | −0.13 (−0.38/013) |

| Bunch intensity | 1.25 (0.47/2.04) | 0.00 (−0.04/0.04) | −0.03 (−0.16/0.10) |

| Listening | 3.05 (0.77/5.33) | 0.00 (−0.11/0.11) | 0.04 (−0.34/0.43) |

| Smelling | 19.71 (−26.9/66.31) | 0.03 (−3.15/3.22) | 0.65 (−7.86/9.15) |

| Retreat | 22.32 (−45.87/90.51) | −0.01 (−4.95/4.94) | −0.20 (−28.72/28.32) |

| Maasai man vs. boy | |||

| Bunch | 1.25 (0.02/2.47) | −0.05 (−0.12/0.03) | −0.01 (−0.17/0.14) |

| Bunch intensity | 1.09 (0.39/1.79) | −0.04 (−0.08/-0.01) | 0.01 (−0.08/0.10) |

| Listening | 0.26 (−0.91/1.44) | −0.05 (−0.12/0.03) | −0.04 (−0.19/0.11) |

| Smelling | 21.64 (−26.55/6.984) | 0.07 (−2.5/2.64) | 0.18 (−5.22/5.58) |

| Retreat | 1.47 (0.17/2.78) | −0.06 (−0.13/0.02) | 0.20 (−0.03/0.44) |

Bold text denotes β-estimates with 95% confidence interval that do not overlap zero.

We then compared the behavioral responses of elephant family groups to adult male versus adult female Maasai voices using our natural voice stimuli (Materials and Methods). Here elephants exhibited a significantly greater probability of retreat and investigative smelling when responding to male compared with female voices, as well as a higher mean bunching intensity for defensive bunching (Fig. 1 C and D, Table 1, and Table S1). In this case, there was no statistical difference in the probability of bunching occurring. Interestingly, and in contrast to our original predictions, after resynthesizing the Maasai voice stimuli so that males had the acoustic characteristics of females and vice versa (Materials and Methods), the reactions of the family groups to playbacks of the stimuli remained marked and in the same direction as previously. Thus, male resynthesized voices still led to significantly stronger bunching, listening, and retreat responses than female resynthesized voices, despite having the fundamental frequency and formant values of the opposite sex (Fig. 1 E and F, Table 1, and Table S1).

Because the responses to resynthesized stimuli remained true to the sex of the original speaker, we conducted a final experiment to test whether the resynthesis of male to female voices, which generated such strong defensive reactions above, could have been perceived as young Maasai boys that elephants may have feared because of their role as livestock herders. However, in these playbacks the elephants responded more strongly to adult male compared with Maasai boy voices, with a higher probability of bunching, retreat, and greater overall bunching intensity to Maasai men (Fig. 1 G and H, Table 1, and Table S1).

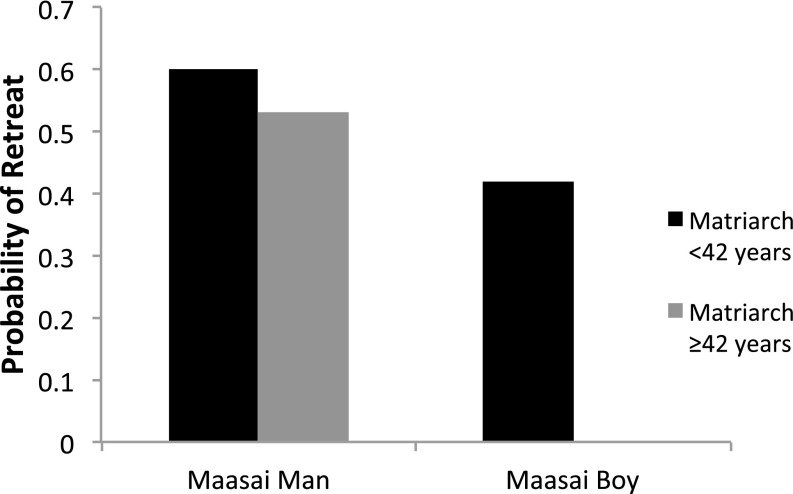

Age of matriarch was a significant variable in some of the models above (Table 1 and Table S1), with families that had older matriarchs being less responsive on our measure of intensity of defensive bunching when faced with the natural vocal stimuli (Table 1). It was also notable that there was an interaction bordering on significance between age of matriarch and response to Maasai men versus boys, such that families with older matriarchs were less likely to retreat to Maasai boys (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The probability of retreat by elephant family groups with different aged matriarchs that received voice playbacks from Maasai men and Maasai boys.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that elephants appear able to make subtle distinctions between voices that are relevant to the level of threat associated with different human subgroups. In our experiments the voices of Maasai men were clearly discriminated from Kamba men, with the former eliciting higher levels of defensive bunching and investigative smelling, responses that would be highly adaptive if Maasai men were actually present. Moreover, male Maasai voices are distinguished from those of Maasai women, with female Maasai voices less likely to generate retreats or investigative smelling and being associated with lower bunching intensities. These findings provide unique evidence that a cognitively advanced social mammal can use language and sex cues in human voices as a basis for assessing predatory threat. Given that humans are undoubtedly the most dangerous and adaptable predator that elephants typically face, such skills are highly adaptive and could prove crucial for survival.

It is important to note that the behavioral reactions that we obtained to human stimuli were markedly different from those generated by playbacks of lion roars in our earlier work (1). Elephants very rarely attempted to approach when faced with human stimuli; instead, reactions involving defensive bunching, retreats and investigative smelling were much more common. Such reactions appear tailored precisely to the type of threat that humans (as opposed to lions) represent. Whereas an aggressive mobbing response can prove very effective in driving off lions (1), it is unlikely to succeed against humans armed with spears and would instead put the family group in great danger. In contrast, adopting defensive reactions, particularly when voices are heard at a distance, may result in the threat being avoided altogether. In addition, it was notable that responses to playback of human stimuli were apparently associated with a greater degree of stealth in that audible vocalizations only occurred in 10% of cases, in comparison with 67% after lion playbacks. It is also of interest that the percentage of retreat responses given to male Maasai voices in our experiments, although high (57%), was lower than the 100% obtained when Bates et al. (15) simulated the presence of Maasai men using scent cues. Again, this finding could suggest tailoring of the response to the nature of the threat involved; talking men may be less likely to hunt than silent men, and further monitoring rather than immediate retreat may be appropriate here.

Human language is rich in acoustic cues that could provide highly relevant and detailed information about human speakers that may be correlated with their potential to act as predators. The ability to distinguish between Maasai and Kamba male speakers delivering the same phrase in their own language suggests that elephants can discriminate between different languages. Although it remains possible that some associated acoustic characteristic of the voice itself—based on morphological differences between speakers from different ethnic groups—may be playing a role, this seems less likely than the more obvious distinction based on language (and dialect). This apparently quite sophisticated skill would have to be learned during development (see also below), although younger individuals could also follow the lead of the matriarch and other older females, taking their cue from more experienced group members.

It is clear from the playbacks of male versus female Maasai speakers that elephants are also able to identify sex cues in natural human voices, and are less likely to interrupt their normal behavior when they hear female Maasai voices. Antipredator responses may involve significant costs in the long term if feeding and other activities are curtailed in situations where nondangerous individuals within a potentially threatening subgroup are encountered (see also ref. 5), so the ability to ameliorate responses to such individuals could have considerable fitness benefits (see also ref. 24). Sex categorization provides an obvious way to distinguish threatening from nonthreatening Maasai voices and elephants are clearly adept at making this distinction.

Interestingly, however, when we altered fundamental frequency and formants in resynthesized voice stimuli to mimic the opposite sex, acoustic features known to be central in human judgements of voice gender, our playbacks revealed that elephants did not appear to be making the sex distinction on the basis of these particular cues. It is important to note that the resynthesis process was not in itself causing the elevated response to the male exemplars that we resynthesized, as we also conducted the matched contrast of resynthesizing female voices to male, and in this case there was clearly no elevation in response. The differences between the genders in human voice production are more extensive than those we manipulated, and such residual acoustic indicators can result in resynthesized voices being perceived as the sex of the original speaker in human sex discriminations (25). In particular, even though fundamental frequency and formants were changed to advertise the opposite sex in our experiments, socio-phonetic cues (differences in the way males and females deliver an utterance) would have remained, women naturally having wider prosodic variation and more “breathy” voices, for example (25, 26). Additional experiments would be required to explore the acoustic characteristics involved, but on the basis of our results it seems that elephants do not appear to base their sex distinction solely on the cues most commonly used by humans to distinguish between the voices of the sexes.

We were able to eliminate one alternative possibility, that male voices resynthesized to female fundamental frequency and formant values were perceived as Maasai boys. In Maasai society young boys typically play the role of livestock guardians and herders (22), and elephants would be likely to encounter them commonly. However, when we contrasted playbacks of the natural voices of Maasai boys with those of Maasai men, it was apparent that Maasai men still generated dramatically stronger responses. It was also interesting that families with older matriarchs appeared more effective in correctly attributing threat in this situation: they were more likely to retreat to the voices of Maasai men than Maasai boys relative to families with younger matriarchs. Overall, however, interactions between matriarch age and ability to correctly discern the most threatening stimuli were generally absent. Instead, in contrast to our previous findings on responses to lion playbacks (1), even families with younger matriarchs appeared able to make most of the relevant distinctions. What did differ was the overall responsiveness to human voice stimuli, and here younger matriarchs proved more reactive overall (particularly on the basis of bunching intensity).

The behavioral plasticity of large-brained mammal species may enable them to respond to novel ecological and social challenges with greater flexibility than smaller-brained species (1, 27). For elephants to successfully coexist with humans, they must use areas where the likelihood of interaction with potential human predators is minimized (15, 28). Indeed, elephants are known to move significantly faster along unprotected “corridors” that link separate parts of their range within protected areas, such as national parks (29), and there are recent reports that they avoid crop raiding during the full moon, a time period associated with greater visibility and elevated human activity (30). Our results illustrate the type of cognitive skill that might underlie such flexibility, here built on sophisticated abilities to discern fine-scaled differences in human voice characteristics. In the Amboseli ecosystem, this has provided them with the means to detect and avoid potentially dangerous Maasai pastoralists that use the same savanna habitats for grazing their cattle.

Complex and context-specific discriminatory abilities of the sort demonstrated here are likely to be strongly influenced by social learning (see also refs. 1 and 7). Such highly specialized cognitive skills are often unique to a particular population and have been shown across a range of social and cognitively advanced species, including a population of wild bottlenose dolphins in Brazil that use unique cultural knowledge and experience of human activities to engage in cooperative hunting with artisanal fisherman (31). The advantages associated with such marked behavioral adaptability are considerable and provide us with important insights into the evolutionary processes that may have selected for larger brain size (27). Nevertheless, it is important to note that cognitively advanced species such as elephants, cetaceans, and primates are susceptible to severe demographic impacts when faced with extreme and rapid environmental change, specifically because of their long generation time and comparatively slow population growth (32).

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that elephant family groups have the propensity to discern fine-scaled differences in human voices associated not only with ethnic group but also sex and age. This detailed knowledge enables them to specifically identify the most dangerous human subgroups, and tailor their behavioral responses accordingly. Antipredator behavior can be energetically costly as a function of reduced foraging, increased locomotion, and elevated physiological stress that could ultimately impact the fitness of individuals within the family group, especially if elicited frequently in situations of comparatively low risk. Having the ability to discriminate real from apparent threat is therefore highly adaptive, particularly in the case of human predators that differ in relatively subtle cues, and where the associated danger is likely to show pronounced spatial and temporal variation across the landscape. Our study provides a unique detailed assessment of human voice discrimination in a wild population of long-lived, large-brained mammals, providing important insights into the potential benefits of sophisticated mechanisms for distinguishing different subcategories within a single predator species. The findings should prompt similar studies in other animal populations that have a long history of coexistence with humans.

Materials and Methods

Study Site.

All playback experiments were conducted on a free-ranging population of elephants in Amboseli National Park, Kenya between March 2010 and December 2011. The elephant population in Amboseli numbered ∼1,500 elephants, including 58 family groups. The Amboseli Elephant Research Project (AERP, www.elephanttrust.org) has long-term demographic and behavioral data on the entire population, including detailed ages for all elephants born after 1971, whereas ages for older individuals were estimated using criteria that are accepted as a standard in studies of African elephants (24). All elephants in the population are habituated to the presence of AERP research vehicles. This work complies with the Association for the Study of Animal Behaviour/Animal Behaviour Society guidelines for the use of animals in research, and received approval from the Ethical Review Committee at the University of Sussex.

Vocal Recordings.

The 35 human voice exemplars used in this study were recorded from volunteers in Amboseli National Park (10 adult male and 10 adult female Maasai speakers, 10 adult male Kamba speakers and 5 Maasai boy speakers), using a Sennheiser MKH 110 microphone linked to a Tascam HD-P2 digital audio recorder. Each of the volunteers was asked to say “Look, look over there, a group of elephants is coming” in a clear and relaxed manner using their first language (either Maasai or Kamba). The mean length of the utterance was 4.1 s for adult male Maasai, 4.0 s for adult male Kamba, 5.2 s for adult female Maasai and 5.1 s for Maasai boys. The age range of the subjects was 10–57 y of age. A sample of these playback stimuli are available in the following audio files: Maasai male (Audio File S1), Kamba male (Audio File S2), Maasai female (Audio File S3), and Maasai boy (Audio File S4).

Resynthesis Protocol.

For the resynthesis playback experiments, five Maasai male and five Maasai female recordings were selected at random. The “change sex” function in PRAAT 5.2.21 was used to generate the appropriate new pitch median and formant frequencies. The values for these calculations were derived from previous studies, which have shown that the morphological development of the vocal folds under the influence of testosterone leads to them producing a fundamental frequency (F0) that is approximately one octave lower (100–120 Hz) (33) than for adult females (200–220 Hz) (33), whereas the lengthening of the male vocal tract associated with the descent of the larynx at puberty and subsequent growth results in formant frequencies in males versus females having a ratio of ∼0.8:1 (34, 35). To confirm this relationship for Maasai and Kamba speakers, we extracted the F0 and frequencies for the first two formants for each of our exemplars in PRAAT 5.2.21 (male mean F0 = 130 Hz, female mean F0 = 210 Hz and female to male formant ratio of 1.16). The spectrograms of the resynthesized calls were viewed in PRAAT 5.2.21 to ensure that the pitch and formant frequencies had been adjusted correctly. Sample resynthesized stimuli are available as the following audio files: male resynthesized to female (Audio File S5) and female resynthesized to male (Audio File S6).

Playback Procedure.

A total of 142 playbacks were conducted on 47 elephant family groups (1–7 playbacks per group) in daylight hours (between 7:00 AM and 6:00 PM). Elephant family groups consist of related adult females and their dependent offspring, led by the oldest female or matriarch, and in our playbacks mean family size was 11(± 5.5 SD) with a mean matriarch age of 38 y (± 8.2 SD). The voices were broadcast through a Mipro MA707 portable loudspeaker connected to a Tascam HD-P2 digital audio recorder, which could be readily deployed in the field and easily camouflaged. The peak sound pressure level at 1 m from the loudspeaker was standardized at 95 dBA for each of the exemplars, comparable to that of moderately loud conservation. Sound pressure levels were measured with a CEL-414/3 sound level meter. The remotely powered loudspeaker, placed behind a camouflaged screen (woven palm leaves), was located 50 m from the family group of elephants for playback. A 2-min delay to playback was incorporated in the sound file for each of the exemplars to enable the observers to position the research vehicle away from the loudspeaker after putting the camouflaged equipment in place.

The first playback exemplars presented to family groups were randomized and subsequent playbacks to the same family group were then systematically presented. A minimum period of 7 d was left between playbacks to the same family to avoid habituation. Playbacks were not given to groups with calves of less than 1 mo (1, 24). The responses of the family group to playback were observed through binoculars and recorded on video using a Canon XM2 camera. Video data were coded by G.S. and K.M. and data sheets were annotated, detailing the occurrence and length of five key behavioral responses: bunching, bunching intensity, prolonged listening, investigative smelling, and retreat.

Bunching.

Bunching is a defensive response to perceived threat by adult females and their young, which resulted in the diameter of the family group decreasing after the broadcast of a playback experiment (calculated in terms of elephant body lengths).

Bunching intensity.

Bunching intensity is the rate at which a defensive bunch of adult females and their young occurred. This measure classifies the overall level of threat response, scoring bunching intensity on a four-point scale as follows: 0, no bunching occurred; 1, subtle reduction in diameter of the group, elephants remained relaxed and continue with preplayback behaviors (>3 min for bunch formation); 2, group formed a coordinated bunch, preplayback behaviors, such as feeding interrupted (1–3 min for bunch formation); 3, fast and sudden reduction in diameter of the group, elephants very alert (<1 min for bunch formation).

Prolonged listening.

Prolonged listening is when adult females continued to exhibit evidence of listening response for more than 3 min after playback, where ears are held in a stiff extended position, often with the head slightly raised.

Investigative smelling.

Investigative smelling is when adult females engaged in either up trunk or down trunk smelling to gather olfactory information on the caller’s identity.

Retreat.

Retreat is when adult females and their young move away from the source of the playback, making a distinct change in direction, often as a coordinated bunch.

An independent observer who did not have access to the live video commentary and was blind to the playback sequence second-coded 15% (25) of the video records; an overall agreement of 95% was achieved on the binary response variables (defensive bunching 100%, prolonged listening 95%, investigative smelling 90%, and retreat 95%) and the Spearman’s ρ correlation on the scores for matriarch bunching intensity was 0.98 (P < 0.0001). A video clip illustrating a strong bunching and retreat response following playback of a Maasai male voice is available in Movie S1 (“Response to Maasai male playback”).

Statistical Analyses.

The playback reactions were analyzed using generalized linear mixed models in the R statistical package (v. 2.15.1; R Core Development Team 2012). Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) adjusted for small sample size (AICc) was used for model selection (36). The appropriate error distribution was fitted according to the nature of the response variable [binomial error structure for binary data (e.g., bunch or no bunch) and Poisson for continuous data (e.g., intensity of bunching response)]. The identity of the elephant group was entered as a random factor in all models, allowing us to account for repeat playbacks to the same family. We also tested the fit of the global model from each analysis (with elephant group as a random effect) against a global model with both elephant group and stimulus exemplar number as random effects, to determine whether repeated use of individual playback stimuli accounted for any observed variance in the data. The AICc scores demonstrated that there was no support for including stimulus exemplar number as a random effect. Five distinct response behaviors (see above for definitions) were the dependent variables for tests of whether matriarchs and their family groups adapted their behavioral responses to human voice playbacks as a function of perceived threat. Null models, which did not include any explanatory variables, were also generated for each behavioral measure, along with more complex models (Table S1) that investigated the additive and interactive effects of matriarch age [a key factor in our previous research (1, 24)]. The AICcmodavg package in R generated AICc scores and model weights for each of the candidate models. To extract parameter estimates and their 95% confidence intervals, model averaging was performed on all top models that accounted for a combined ≥0.95 of the AICc weight. The effect size for each parameter was assessed on using the β-estimates and the 95% confidence intervals. If the confidence intervals overlapped zero, this demonstrated that there was no effect of the parameter in question.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Kenyan Office of the President and Kenya Wildlife Services for permission to conduct the research in Amboseli National Park; Kenya Airways, P. B. Allen, and B & W Loudspeakers for logistical support and provision of equipment; the Amboseli Trust for Elephants for facilitating this study; Joyce Poole, Rob Slotow, and Sarah Durant for valuable discussions on this and contributions to related work; Chris Darwin and David Reby for helpful advice on resynthesizing calls. We are most grateful to Line Cordes for second coding of video records and statistical advice, and to Jen Wathan, Victoria Ratcliffe, and two referees for useful comments on the manuscript. This study was supported by the Leverhulme Trust (Grant F/00 230/AC).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

See Commentary on page 5071.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1321543111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.McComb K, et al. Leadership in elephants: The adaptive value of age. Proc Roy Soc B. 2011;278(1722):3270–3276. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2011.0168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheney DL. How Monkeys See the World: Inside the Mind of Another Species. Chicago: Univ of Chicago Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manser MB, Seyfarth RM, Cheney DL. Suricate alarm calls signal predator class and urgency. Trends Cogn Sci. 2002;6(2):55–57. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01840-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marzluff JM, Walls J, Cornell HN, Withey JC, Craig DP. Lasting recognition of threatening people by wild American crows. Anim Behav. 2010;79(3):699–707. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Papworth S, Milner-Gulland EJ, Slocombe K. Hunted woolly monkeys (Lagothrix poeppigii) show threat-sensitive responses to human presence. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(4):e62000. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zuberbühler K. Causal knowledge of predators’ behaviour in wild Diana monkeys. Anim Behav. 2000;59(1):209–220. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1999.1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deecke VB, Slater PJ, Ford JK. Selective habituation shapes acoustic predator recognition in harbour seals. Nature. 2002;420(6912):171–173. doi: 10.1038/nature01030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ouattara K, Lemasson A, Zuberbühler K. Campbell’s monkeys concatenate vocalizations into context-specific call sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(51):22026–22031. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908118106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell G, Kuehl H, N’Goran Kouamé P, Boesch C. Alarming decline of West African chimpanzees in Côte d’Ivoire. Curr Biol. 2008;18(19):R903–R904. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bouché P, et al. Will elephants soon disappear from West African savannahs? PLoS ONE. 2011;6(6):e20619. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marzluff JM, Miyaoka R, Minoshima S, Cross DJ. Brain imaging reveals neuronal circuitry underlying the crow’s perception of human faces. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(39):15912–15917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206109109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Slobodchikoff CN, Briggs WR, Dennis PA, Hodge A-MC. Size and shape information serve as labels in the alarm calls of Gunnison’s prairie dogs Cynomys gunnisoni. Curr Zool. 2012;58(5):741–748. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slobodchikoff CN, Paseka A, Verdolin JL. Prairie dog alarm calls encode labels about predator colors. Anim Cogn. 2009;12(3):435–439. doi: 10.1007/s10071-008-0203-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levey DJ, et al. Urban mockingbirds quickly learn to identify individual humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(22):8959–8962. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811422106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bates LA, et al. Elephants classify human ethnic groups by odor and garment color. Curr Biol. 2007;17(22):1938–1942. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.09.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee WY, Lee S-I, Choe JC, Jablonski PG. Wild birds recognize individual humans: Experiments on magpies, Pica pica. Anim Cogn. 2011;14(6):817–825. doi: 10.1007/s10071-011-0415-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor AA, Davis H. Individual humans as discriminative stimuli for cattle (Bos taurus) Appl Anim Behav Sci. 1998;58(1):13–21. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sliwa J, Duhamel J-R, Pascalis O, Wirth S. Spontaneous voice-face identity matching by rhesus monkeys for familiar conspecifics and humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(4):1735–1740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008169108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Proops L, McComb K. Cross-modal individual recognition in domestic horses (Equus caballus) extends to familiar humans. Proc Roy Soc B. 2012;279(1741):3131–3138. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.0626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wascher CAF, Szipl G, Boeckle M, Wilkinson A. You sound familiar: Carrion crows can differentiate between the calls of known and unknown heterospecifics. Anim Cogn. 2012;15(5):1015–1019. doi: 10.1007/s10071-012-0508-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saito A, Shinozuka K. Vocal recognition of owners by domestic cats (Felis catus) Anim Cogn. 2013;16(4):685–690. doi: 10.1007/s10071-013-0620-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moss CJ, Croze H, Lee PC. The Amboseli Elephants: A Long-Term Perspective on a Long-Lived Mammal. Chicago: Univ of Chicago Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiyo PI, et al. Using molecular and observational techniques to estimate the number and raiding patterns of crop-raiding elephants. J Appl Ecol. 2011;48(3):788–796. [Google Scholar]

- 24.McComb K, Moss C, Durant SM, Baker L, Sayialel S. Matriarchs as repositories of social knowledge in African elephants. Science. 2001;292(5516):491–494. doi: 10.1126/science.1057895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Assmann PF, Dembling S, Nearey TM (2006) Effects of frequency shifts on perceived naturalness and gender information in speech. Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Spoken Language Processing, Pittsburgh, PA, Sept. 17–21, 2006, pp. 889–892.

- 26.Jannedy S, Hay J. Modelling sociophonetic variation. J Phonetics. 2006;34(4):405–408. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sol D, Bacher S, Reader SM, Lefebvre L. Brain size predicts the success of mammal species introduced into novel environments. Am Nat. 2008;172(Suppl 1):S63–S71. doi: 10.1086/588304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vermeij GJ. The limits of adaptation: Humans and the predator-prey arms race. Evolution. 2012;66(7):2007–2014. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2012.01592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Douglas-Hamilton I, Krink T, Vollrath F. Movements and corridors of African elephants in relation to protected areas. Naturwissenschaften. 2005;92(4):158–163. doi: 10.1007/s00114-004-0606-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gunn J, Hawkins D, Barnes R. The influence of lunar cycles on crop-raiding elephants; Evidence for risk avoidance. Afr J Ecol. 2014 in press. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Daura-Jorge FG, Cantor M, Ingram SN, Lusseau D, Simões-Lopes PC. The structure of a bottlenose dolphin society is coupled to a unique foraging cooperation with artisanal fishermen. Biol Lett. 2012;8(5):702–705. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2012.0174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Schaik CP. The costs and benefits of flexibility as an expression of behavioural plasticity: A primate perspective. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2013;368(1618):20120339. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simpson AP. Phonetic differences between male and female speech. Lang Linguist Compas. 2009;3(2):621–640. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hillenbrand J, Getty LA, Clark MJ, Wheeler K. Acoustic characteristics of American English vowels. J Acoust Soc Am. 1995;97(5 Pt 1):3099–3111. doi: 10.1121/1.411872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fitch WT, Giedd J. Morphology and development of the human vocal tract: A study using magnetic resonance imaging. J Acoust Soc Am. 1999;106(3 Pt 1):1511–1522. doi: 10.1121/1.427148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burnham KP, Anderson DR. Model Selection and Multi-Model Inference: A Practical Information-Theoretic Approach. New York: Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.