Significance

Loss of pancreatic islet β cells occurs in both major forms of diabetes, and strategies for restoring β cells are needed. The homeobox transcription factor NK6 homeobox 1 (Nkx6.1) activates β-cell proliferation and insulin secretion when overexpressed in pancreatic islets, but the molecular pathway involved in the proliferative response is unknown. We show that Nkx6.1 induces expression of orphan nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, members 1 and 3 (Nr4a1 and Nr4a3), which stimulate proliferation via two mechanisms: (i) increased expression of the cell cycle inducers E2F transcription factor 1 and cyclin E1; and (ii) induction of anaphase-promoting complex elements, and degradation of the cell cycle inhibitor p21. These studies reveal a new bipartite pathway for activation of β-cell proliferation that could guide development of therapeutic strategies for diabetes.

Abstract

Loss of functional β-cell mass is a hallmark of type 1 and type 2 diabetes, and methods for restoring these cells are needed. We have previously reported that overexpression of the homeodomain transcription factor NK6 homeobox 1 (Nkx6.1) in rat pancreatic islets induces β-cell proliferation and enhances glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, but the pathway by which Nkx6.1 activates β-cell expansion has not been defined. Here, we demonstrate that Nkx6.1 induces expression of the nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, members 1 and 3 (Nr4a1 and Nr4a3) orphan nuclear receptors, and that these factors are both necessary and sufficient for Nkx6.1-mediated β-cell proliferation. Consistent with this finding, global knockout of Nr4a1 results in a decrease in β-cell area in neonatal and young mice. Overexpression of Nkx6.1 and the Nr4a receptors results in increased expression of key cell cycle inducers E2F transcription factor 1 and cyclin E1. Furthermore, Nkx6.1 and Nr4a receptors induce components of the anaphase-promoting complex, including ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2C, resulting in degradation of the cell cycle inhibitor p21. These studies identify a unique bipartite pathway for activation of β-cell proliferation, suggesting several unique targets for expansion of functional β-cell mass.

Type 1 diabetes is characterized by the autoimmune destruction of β cells, whereas type 2 diabetes is linked to a gradual loss of β-cell mass and function driven by metabolic and stress-related factors (1, 2). Adult β cells have a low intrinsic replicative rate but retain some capacity for expansion in response to physiological perturbations such as pregnancy and obesity (3, 4). A better understanding of molecular pathways that activate β-cell proliferation may help to define strategies for replacement of functional β-cell mass in both major forms of diabetes.

The homeobox transcription factor NK6 homeobox 1 (Nkx6.1) is essential for β-cell development (5). Nkx6.1 is actively expressed during the secondary transition, a period in which β cells grow and differentiate (5). This suggests that Nkx6.1 expression may play a role in expansion of functional β-cell mass. Consistent with this idea, overexpression of Nkx6.1 in mature islets results in improved glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) and enhanced β-cell proliferation (6). However, the molecular pathway by which Nkx6.1 induces islet β-cell proliferation has yet to be elucidated.

The nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A (Nr4a) orphan nuclear receptor family consists of three members, Nr4a1/Nur77, Nr4a2/Nurr1, and Nr4a3/NOR1 (7), which have been implicated in control of diverse biological functions (8–11), with the nature of the biological effect(s) being dependent on expression level and tissue context. Here, we show that Nr4a1 and Nr4a3 are strongly up-regulated by Nkx6.1 overexpression in rat islets and that either factor is necessary and sufficient to induce β-cell proliferation. Consistent with these findings, global knockout of Nr4a1 significantly reduces β-cell mass in neonatal and young mice. In addition, we demonstrate that Nkx6.1, Nr4a1, and Nr4a3 all induce expression of E2F transcription factor 1 (E2F1) and cyclin E1, genes that gate cell cycle entry, while also up-regulating key components of the anaphase-promoting complex (APC), leading to degradation of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1a (p21).

Results

Up-Regulation of Nr4a1 and Nr4a3 in Response to Nkx6.1 Overexpression in Rat Islets.

Rat islets treated with AdCMV-Nkx6.1 adenovirus exhibit an increase in Nkx6.1 protein within 24 h of viral treatment, but significant β-cell proliferation is first observed at 72 h (6), suggesting that Nkx6.1 acts through target genes that ultimately serve as the direct mediators of the proliferative response. To investigate earlier effects of Nkx6.1, we performed microarray analysis on five independent sets of rat islets cultured for 48 h after treatment with AdCMV-Nkx6.1 or AdCMV-βGal adenoviruses or with no viral treatment; 748 genes were increased by ≥50%, and 240 were decreased by ≥50% in islets with Nkx6.1 overexpression relative to control islets [P < 0.05; the gene lists have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database].

Gene set enrichment analysis revealed that core cell cycle networks were changed in response to Nkx6.1 expression (Fig. S1). Among 26 transcription factors that were affected (Table S1), the orphan nuclear receptors Nr4a1 and Nr4a3 were those most tightly associated with the cell cycle modules. Consistent with the microarray results, RT-PCR analysis revealed 3.1- and 7.8-fold increases in Nr4a1 and Nr4a3 mRNA levels, respectively, at 48 h after AdCMV-Nkx6.1 treatment relative to control islets (Fig. 1 A and B). Titration studies revealed that proliferation was observed in response to a range of 2.6- to 14.4-fold increases in Nkx6.1 protein levels (Fig. S2), and Nr4a1 and Nr4a3 mRNA levels were increased similarly and consistently over this range. Nr4a1 and Nr4a3 protein levels were also clearly elevated in response to Nkx6.1 expression (Fig. 1C). Finally, we found binding of endogenous Nkx6.1 to the Nr4a1 and Nr4a3 genes by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis in the 832/13 insulinoma cell line. This binding was significant both when normalized to a nonbound amplicon (Fig. 1 D and E) or when expressed as fold-enrichment relative to control IgG.

Fig. 1.

Overexpression of Nkx6.1 induces expression of Nr4a1 and Nr4a3. Rat islets were treated with AdCMV-GFP or AdCMV-Nkx6.1. (A and B) Nr4a1 (A) and Nr4a3 (B) mRNA levels. (C) Immunoblot analysis of whole-islet lysates 48 h after viral transduction. Data in A--C represent the means ± SEM of three independent experiments. (D and E) ChIP analysis of endogenous Nkx6.1 binding to the Nr4a1 (D) and Nr4a3 (E) promoter regions relative to a nonbound amplicon in INS-1–derived 832/13 cells. Data represent means ± SEM of six independent experiments. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001. P values represent the comparison between Nkx6.1- and GFP-treated islets for RT-PCR and immunoblots and the comparison between anti-Nkx6.1 and IgG-precipitated samples in ChIP analyses.

Nr4a1 and Nr4a3 Are Sufficient to Induce β-Cell Proliferation.

Adenovirus-mediated overexpression of Nr4a1 or Nr4a3 in rat islets resulted in 14- and 10-fold increases in protein levels, respectively, by 48 h after viral treatment (Fig. 2A). AdCMV-Nkx6.1-treated islets exhibited a significant increase in [3H]thymidine incorporation by 72 h, whereas increases were observed by 48 h in islets treated with either AdCMV-Nr4a1 or AdCMV-Nr4a3 (Fig. 2B). At 96 h, Nkx6.1 caused a sixfold induction in [3H]thymidine incorporation, similar to the effects of treatment with AdCMV-Nr4a1 (fourfold induction) or AdCMV-Nr4a3 (near sixfold induction) at 48 h. Combined overexpression of Nr4a1 and Nr4a3 had no additive effect on proliferation (Fig. S3A), suggesting that the two factors activate similar downstream molecular pathways. These data are consistent with a model in which Nkx6.1 overexpression serves to activate islet cell proliferation by first activating expression of Nr4a1 and Nr4a3.

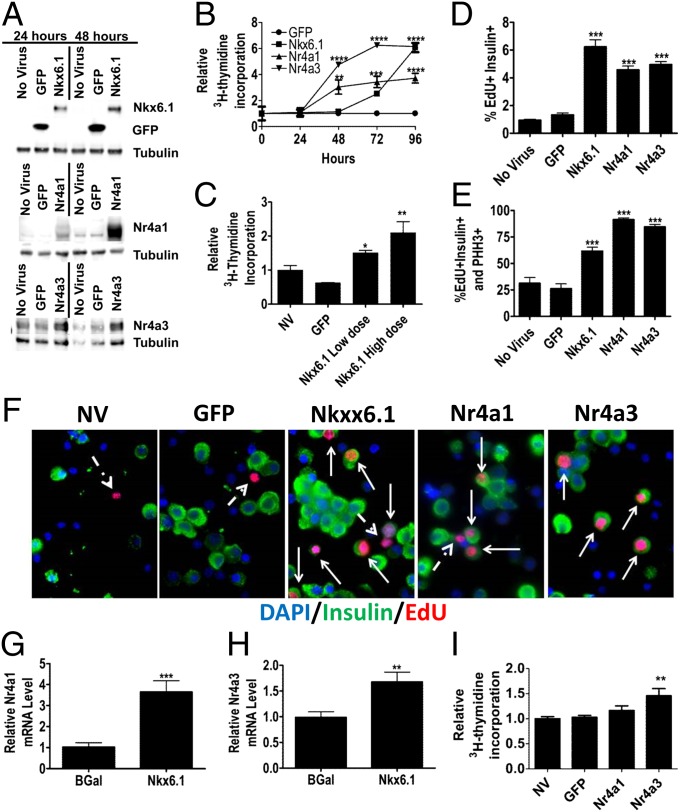

Fig. 2.

Overexpression of Nr4a1 or Nr4a3 is sufficient to induce β-cell proliferation. (A) Immunoblot analysis demonstrating adenovirus-mediated overexpression of Nkx6.1, Nr4a1, or Nr4a3. (B) Incorporation of [3H-methyl]thymidine in rat islets. (C) Islets were treated with lentiviruses expressing GFP or Nkx6.1 or left untreated, and [3H-methyl]thymidine incorporation was measured after 136 h. (D) Percentage of EdU+insulin+ islet cells cultured with EdU for 96 h. (E) Percentage of EdU+insulin+ islet cells that are also PHH3+. (F) Representative images (100× magnification) of islets labeled with EdU. Solid arrows indicate insulin+EdU+ nuclei, and broken arrows indicate insulin−EdU+ nuclei. DAPI is blue, insulin is green, and EdU is pink. (G and H) Treatment of human islets with AdCMV-Nkx6.1 increases Nr4a1 (G) and Nr4a3 (H) mRNA levels. (I) [3H-methyl]thymidine incorporation into human islets measured 96 h after indicated treatments. Data represent means ± SEM of a minimum of three independent experiments; human islet data represent eight independent experiments. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001. All comparisons with AdCMV-GFP–treated islets.

A recent study reported that conditional overexpression of Nkx6.1 in transgenic mouse islets does not activate β-cell proliferation (12), in contrast to our consistent observations of induction of proliferation by adenovirus-mediated Nkx6.1 overexpression in rat islets (refs. 6 and 13 and this study). To test the possibility that adenovirus-encoded genes are involved in the proliferative effect, we expressed Nkx6.1 from an alternate viral (lentivirus) vector. Treatment of rat islets with two different doses of a lentivirus encoding Nkx6.1 caused 3.9- and 5.4-fold increases in Nkx6.1 mRNA levels, with attendant 2.4-fold and 3.3-fold increases in [3H]thymidine incorporation relative to green florescent protein (GFP) lentivirus (Fig. 2C). Thus Nkx6.1-mediated islet cell proliferation is not dependent on adenovirus-specific gene products.

Based on 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) staining and insulin costaining, AdCMV-Nkx6.1 treatment resulted in replication of 6.2% of β cells, whereas treatment with AdCMV-Nr4a1 or AdCMV-Nr4a3 resulted in replication of 4.6% or 5.0% of β cells, respectively, relative to only 1.3% of β cells replicating in untreated or AdCMV-GFP–transduced islets (Fig. 2 D and F). For all treatment conditions, <2.5% of non-β cells were found to be replicating, and overexpression of Nr4a1 or Nr4a3 had no effect on this basal level.

Staining for PHH3 identifies cells that have moved past the G2 checkpoint and into mitosis. Of the EdU+insulin+ cells in Nkx6.1-, Nr4a1-, and Nr4a3-overexpressing islets at 96 h, 62%, 91%, and 84% of the cells were also positive for PHH3, respectively (Fig. 2E). The larger fraction of PHH3-positive β cells in the AdCMV-Nr4a1 and AdCMV-Nr4a3-treated islets is anticipated given the time lag in Nkx6.1-mediated replication described above. Expression of cell cycle activators such as cyclin D and Cdk6 in islets can result in DNA damage, as indicated by γH2a histone family, member x (γ-H2AX) staining (14). Overexpression of Nkx6.1 induces a large increase in EdU-positive cells in rat islets, but only a small percentage of these cells costain with γ-H2AX, suggesting that Nkx6.1 induces a “non-damaging” proliferative response (Fig. S4). Moreover, large induction of PHH3 by Nkx6.1, Nr4a1, or Nr4a3 expression is indicative of complete activation of the cell cycle, rather than cell cycle arrest as observed in response to cyclin D and Cdk6 expression (14). Taken together, these data demonstrate that similar to Nkx6.1 (6, 13), Nr4a1 and Nr4a3 preferentially induce replication in β cells, with a high percentage of these cells successfully progressing through the cell cycle to M phase.

We next investigated the impact of Nr4a1 or Nr4a3 on human islet replication, using islets from eight different donors ranging in age from 14 to 61 y (average, 33.8 y), and with a body mass index of 21.8–35.9 kg/m2 (average, 30.1 kg/m2). Human islets with overexpressed Nkx6.1 had increased expression of both Nr4a1 and Nr4a3 (Fig. 2 G and H). Furthermore, overexpression of Nr4a3 but not Nr4a1 in human islets caused an increase of 46% (P = 0.005) in [3H]thymidine incorporation relative to control islets (Fig. 2I). We have previously reported that Nkx6.1 has a lesser impact on human compared with rat islet proliferation (6); this is consistent with the lesser potency of overexpressed Nr4a receptors in human compared with rat islets shown here.

Finally, overexpression of Nkx6.1 in rat islets results in enhanced GSIS (6) and this effect is mediated by induction of an islet prohormone, VGF (15). Treatment of rat islets with either AdCMV-Nr4a1 or AdCMV-Nr4a3 had no impact on GSIS (Fig. S3B). Consistent with this finding, overexpression of Nkx6.1 causes a strong induction of VGF (15), whereas Nr4a1 or Nr4a3 overexpression did not impact VGF expression (Fig. S3C).

Nr4a1 and Nr4a3 Are Necessary for Nkx6.1-Mediated Proliferation.

We next used siRNA and dominant-negative constructs to determine if Nr4a1 and Nr4a3 are required for Nkx6.1-induced β-cell proliferation. Treatment of rat islets with Ad-siNr4a1 caused a 45% decrease in Nr4a1 mRNA levels, whereas Ad-siNr4a3 treatment caused a 50% decrease in Nr4a3 levels (Fig. 3A). Islets treated with AdCMV-Nkx6.1 alone or the combination of AdCMV-Nkx6.1 plus Ad-siControl exhibited an eightfold induction in [3H]thymidine incorporation compared with untreated islets, whereas islets treated with AdCMV-Nkx6.1 plus Ad-siNr4a1 or AdCMV-Nkx6.1 plus Ad-siNr4a3 had 50% and 60% less [3H]thymidine incorporation relative to control islets, respectively (Fig. 3B). A dominant-negative Nr4a1 mutant known as Nr4a1-M1 has a deletion in the AF1 transactivation domain that impairs its activity, and its overexpression interferes with the function of all endogenous Nr4a receptors (16). Islets transduced with AdCMV-Nkx6.1 plus AdCMV-Nr4a1-M1 exhibited a 40% decrease in [3H]thymidine incorporation compared with islets treated with AdCMV-Nkx6.1 plus AdCMV-GFP (Fig. 3 C and D). In sum, Nr4a1 and Nr4a3 are necessary for Nkx6.1-mediated islet cell proliferation.

Fig. 3.

Nr4a1 and Nr4a3 are necessary for Nkx6.1-mediated proliferation. Rat islets were treated with AdCMV-Nkx6.1 and either Ad-siNr4a1, Ad-siNr4a3, or Ad-siControl (siCTRL) for 96 h. (A) Immunoblot assay of whole-islet lysates. (B) [3H-methyl]thymidine incorporation. Rat islets were treated with adenoviruses expressing GFP, Nkx6.1, or the dominant-negative Nr4a construct Nr4a1-M1 (M1), followed by immunoblot assay of whole-islet lysates (C). (D) [3H-methyl]thymidine incorporation. Data represent means ± SEM of a minimum of three independent experiments. **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001 compared with AdCMV-Nkx6.1 plus Ad-siControl (B) or Nkx6.1-treated islets (D).

Neonatal and Young Nr4a1 Knockout Mice Have Decreased β-Cell Area.

To investigate whether loss of N4a family members curtails β-cell expansion in vivo, we measured total islet area in global Nr4a1 knockout mice (8) compared with wild-type mice. Mice deficient for Nr4a1 are known to have perturbations in metabolic fuel homeostasis (8, 16–18), but the impact of manipulation of the Nr4a factors on islet mass has not been reported. At postnatal day 11, wild-type mice had a β-cell area of 22% relative to total pancreas area, whereas the Nr4a1 knockout had a β-cell area of 11% (Fig. 4 A and C). At two months of age, wild-type mice had β-cell area of 1.8%, compared with 1.1% in Nr4a1 knockout mice (Fig. 4B). Blood glucose levels were not different in wild-type and Nr4a1 knockout mice at 11 d or 2 mo of age (Fig. S5). We found that 10.9% of β cells in 11-d-old wild-type mice were Ki-67–positive (antigen identified by monoclonal antibody ki-67), versus 7.8% in Nr4a1 knockout mice (Fig. 4D). Furthermore, 8% of β cells were PHH3+insulin+ in 11-d-old wild-type mice, compared with 5.2% in Nr4a1 knockout mice (Fig. 4E). These data demonstrate that loss of Nr4a1 results in a significant decrease in actively cycling β cells in islets of young mice.

Fig. 4.

Mice deficient for Nr4a1 have decreased β-cell area and replication. (A) β-Cell area in pancreas sections from 11-d-old wild-type (WT) and Nr4a1 knockout (KO) mice, expressed as β-cell area relative to total pancreas area. (B) β-Cell area in pancreas sections from 2-mo-old WT or Nr4a1 KO mice. (C) Representative images at 20× magnification of pancreata from WT or Nr4a1 KO mice at 11 d of age. Insulin is red, amylase is green, and DAPI is blue. The percentage of Ki-67+insulin+ (D) and PHH3+insulin+ (E) cells was calculated at 11 d of age. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.005.

Nr4a1 and Nr4a3 Up-Regulate a Subset of Genes Induced by Nkx6.1.

We next used microarray analysis to investigate β-cell proliferative pathways activated by the Nr4a receptors. Using a cutoff of genes that were induced or repressed by ≥50%, with P < 0.05 (n = 5 independent sets of islets), Nr4a1 overexpression up-regulated 503 genes, and repressed 323 genes, whereas Nr4a3 overexpression induced 246 genes and repressed 111 genes compared with controls (Fig. S1). There were 54 genes up-regulated in common in response to overexpression of Nkx6.1, Nr4a1, or Nr4a3, which comprised three clusters linked to cell cycle progression (20 genes), chromosome condensation and segregation (9 genes), and components of the APC (4 genes) (Table S2). Using these genes to build a transcriptional network, we observe a strong enrichment of E2F1 target genes (P = 1.2 × 10−63), such as cyclin E1, cyclin A, and cyclin B, and an equally strong link to APC activation (P = 2.4 × 10−30).

Nkx6.1-Mediated Induction of E2F1 and Cyclin E1 Are Dependent on Nr4a1 and Nr4a3.

Previous studies have demonstrated that Nr4a family members bind to and directly induce expression of the E2F1 gene (10). Treatment of rat islets with AdCMV-Nr4a1 or Ad-CMV-Nr4a3 induced E2F1 expression within 48 h, whereas AdCMV-Nkx6.1 treatment had no effect at this time point (Fig. S6A). In contrast, 96 h after treatment with AdCMV-Nkx6.1, a similar up-regulation of E2F1 is observed as for Nr4a1 or Nr4a3 overexpression at 48 h (Fig. S6B). Knockdown of Nr4a1 or Nr4a3 expression by 80% and 90%, respectively, resulted in 54% and 68% decreases in E2F1 mRNA levels in response to Nkx6.1 overexpression at 96 h (Fig. S6B). E2F1 is known to orchestrate cell cycle progression by inducing cell cycle genes (19), including cyclin E1, and overexpression of cyclin E1 is sufficient to induce rat islet β-cell proliferation (6). At 48 h, cyclin E1 is up-regulated in Nr4a1- and Nr4a3-overexpressing, but not Nkx6.1-overexpressing, islets, whereas cyclin E1 is induced by Nkx6.1 at 96 h. The effect of Nkx6.1 to increase cyclin E1 at 96 h is partially blocked by cotreatment of islets with Ad-siNr4a1 or Ad-siNr4a3 (Fig. S6 C and D). These results demonstrate that Nkx6.1-mediated control of cell cycle entry is dependent upon Nr4a-driven up-regulation of E2F1 and its downstream targets, including cyclin E1.

Nkx6.1-Mediated Expression of Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzyme E2C Is Dependent on Nr4a1 and Nr4a3.

The ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2C (Ube2c) is a critical component of the APC. Overexpression of Nr4a1 or Nr4a3 is sufficient to induce expression of Ube2c by 48 h after virus transduction compared with control islets, whereas Nkx6.1 overexpression has no effect at this time point (Fig. 5A). At 96 h, Nkx6.1 overexpression induces Ube2c to a similar degree as Nr4a1 or Nr4a3 expression, and knockdown of either Nr4a1 or Nr4a3 impairs Nkx6.1-mediated induction of Ube2c expression at 96 h (Fig. 5B). These data demonstrate that Nkx6.1-stimulated expression of Ube2c is dependent upon up-regulation of Nr4a1 and Nr4a3.

Fig. 5.

Nkx6.1 up-regulates APC components, leading to degradation of p21. (A) Overexpression of Nr4a1 or Nr4a3 up-regulates expression of Ube2c mRNA at 48 h. (B) Nkx6.1-mediated up-regulation of Ube2c at 96 h is dependent on the expression of Nr4a1 and Nr4a3. (C) Overexpression of Nkx6.1 induces expression of p21 mRNA. (D) Immunoblot analyses demonstrate that p21 protein levels decrease between 48 and 72 h after Nkx6.1 overexpression. Data represent means ± SEM of three independent experiments. For A and D, P values represent the comparison with GFP-treated islets. For B, P values represent comparison with AdCMV-Nkx6.1 plus Ad-siControl islets. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001.

Nkx6.1 Up-Regulation of APC Components Through Nr4a1 and Nr4a3 Results in p21 Degradation.

Treatment of rat islets with AdCMV-Nkx6.1 induces a significant increase in p21 mRNA, beginning at 24 h and sustained to 96 h after viral treatment (Fig. 5C). Interestingly, although p21 protein levels initially increase in parallel with the increase in mRNA through 48 h, by 72 h, a decrease in p21 protein levels is observed (Fig. 5D). Furthermore, at 48 h, islets exposed to AdCMV-Nr4a1 or AdCMV-Nr4a3 have p21 protein levels that are indistinguishable from AdCMV-GFP–treated or untreated islets. (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Loss of p21 stimulates β-cell proliferation (A–E) and summary model (F). (A) p21 protein levels are maintained at baseline levels 48 h after Nr4a1 or Nr4a3 overexpression. (B) Overexpression of Ube2c for 72 h in INS-1 832/13 cells decreases p21 protein levels. (C) Treatment of islets with Ad-siUbe2c decreases [3H-methyl]thymidine incorporation in response to Nkx6.1 overexpression. (D) Percentage of insulin+Edu+ and insulin−Edu+ islet cells in the presence and absence of p21 knockdown. (E) Percentage of EdU+insulin+ cells that are also PHH3+. Data represent means ± SEM of a minimum of three independent experiments. For A, B, and E, P values represent comparison with GFP-treated islets. For C, the P value is for the comparison with AdCMV-Nkx6.1 plus Ad-siControl islets. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001. (F) Schematic summary of bipartite mechanism of Nkx6.1-activated β-cell proliferation.

Given recent evidence of regulation of p21 levels by the APC (20), we investigated the effect of manipulation of Ube2c on p21 protein levels in islet cells. Overexpression of Ube2c in the 832/13 cell line resulted in dramatic lowering of p21 protein levels (Fig. 6B). In addition, knockdown of Ube2c mRNA in rat islets by 87% resulted in a 56% suppression of Nkx6.1-mediated β-cell proliferation (Fig. 6C). Ad-sip21–mediated knockdown of p21 mRNA and protein levels by 60% (Fig. S7 A, D, and E) resulted in a fourfold induction in [3H]thymidine incorporation compared with a sevenfold induction by Nkx6.1 in the same experiment (Fig. S7G). Ad-sip21 treatment also caused a significant decrease in cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1b (p27) mRNA and protein (Fig. S7 B, D, and E) levels and an increase in cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1c (p57) mRNA levels (Fig. S7C). Interestingly, the types of cells that are induced to replicate by Nkx6.1/Nr4a overexpression versus p21 knockdown are different (Fig. 6 D and E). Thus, knockdown of p21 results in replication of 2.7% of insulin-positive cells and 2.4% of insulin-negative cells, whereas the effects of Nkx6.1, Nr4a1, and Nr4a3 are much more β cell-restricted, despite the use of constitutive promoters in all of the viral constructs. Thus, the effect of Nkx6.1, Nr4a1, and Nr4a3 to induce the APC and lower p21 levels occurs in a β cell-selective manner.

Discussion

A hallmark of both major forms of diabetes is the loss of functional β-cell mass. Whereas β-cell proliferation is thought to occur slowly in adult mammals (21, 22), it can be increased by certain physiologic and pathophysiologic conditions such as pregnancy and obesity (3, 23).

We have previously demonstrated that overexpression of Nkx6.1 is among the very rare manipulations that can simultaneously stimulate β-cell proliferation and GSIS in adult islets (6). Nkx6.1-mediated activation of β-cell proliferation occurs 72–96 h after overexpression, implicating Nkx6.1 target genes in this response. The current study identifies Nr4a1 and Nr4a3 as Nkx6.1-regulated genes that control β-cell proliferation. The Nr4a orphan nuclear receptors were originally described as immediate early genes induced by nerve growth factors in PC12 cells (24) and are now recognized to be induced by growth factors, cytokines, fatty acids, and phorbol esters (25). The Nr4a family has been associated with cell survival, proliferation, and induction of apoptosis, with responses depending on cell type and context (26). Importantly, Nkx6.1, Nr4a1, and Nr4a3 do not induce genes associated with cell stress or apoptosis in our microarray studies, suggesting that these factors function mainly to stimulate proliferation when activated in the context of islet β cells.

Our study shows that in islets, Nr4a1 and Nr4a3 induce proliferation through up-regulation of genes that activate the cell cycle, as well as other genes that cause degradation of the cell cycle inhibitor p21 (Fig. 6F). Key members of the first class of genes are E2F1 and cyclin E1. E2F1 has been shown to be a direct Nr4a1 and Nr4a3 target gene, and E2F1 is known to directly up-regulate expression of cyclin E1 (10, 27). Once induced, cyclin E1 binds to cdk2 and phosphorylates Rb, thus allowing E2F1 to induce expression of other cell cycle genes and drive cellular proliferation (27). Key genes involved in the second major arm of the Nkx6.1/Nr4a pathway include Cdc20, Ube2c, and Ube2s, which are critical components of the APC (28). Our data demonstrate that APC-mediated degradation of p21 is essential for Nkx6.1-mediated β-cell proliferation. Our finding that loss of p21 alone is sufficient to induce β-cell proliferation without overexpression of Nkx6.1, Nr4a1, or Nr4a3 suggests that a subpopulation of rat islet β cells are primed to reenter the cell cycle even without up-regulation of positive regulators. These results are consistent with recent data demonstrating the critical importance of cell cycle inhibitors such as p27 and p16 in control of mouse and human islet replication (29). In contrast, mice deficient for p21 exhibit no discernable increase in islet mass (30). The apparent discrepancy between that study and ours may be explained by the absence of p21 through development in knockout mice, leading to compensation due to increased p57 expression (30), whereas our experiments involving acute, siRNA-mediated knockdown of p21 in adult rat islets also resulted in decreased expression of another cell cycle repressor, p27. These issues notwithstanding, our experiments demonstrate that Nr4a1 and Nr4a3 activate the APC, resulting in degradation of p21, removal of the G1 checkpoint, and stimulation of β-cell proliferation.

We also demonstrate that Nr4a1 knockout mice have reduced islet cell mass and β-cell proliferation at postnatal day 11 and at 2 mo of age. Nr4a1 has been shown to regulate gluconeogenic gene expression in the liver, and the loss of Nr4a1 decreases hepatic glucose production (16). It is not possible to determine at this time whether the decreased islet area accompanied by normoglycemia in young Nr4a1 knockout mice is attributable to a β-cell intrinsic effect or to reduced hepatic glucose production or other metabolic effects of peripheral Nr4a1 deficiency. However, our findings are consistent with a report linking polymorphisms in the human Nr4a3 gene with circulating insulin levels (9).

A recent study suggests that adenovirus-mediated overexpression of Nr4a1 in a transformed β-cell line caused impairment of GSIS (31). This is in contrast to the current study, where overexpression of either Nr4a1 or Nr4a3 in primary rat islets had no effect on GSIS. Overexpression of Nkx6.1 in rat islets actually enhances GSIS (6). The insulinotropic effect of Nkx6.1 is explained by its induction of the gene encoding the VGF prohormone and a 21-aa peptide, TLQP-21, that is processed from VGF in islets (15). We find that overexpression of Nr4a1 or Nr4a3 in rat islets has no effect on VGF expression. We have also overexpressed Nr4a1 and Nr4a3 in 832/13 insulinoma cells and failed to observe inhibitory effects on GSIS. We conclude that the pathway by which Nkx6.1 enhances GSIS involves induction of VGF independent of Nr4a1 or Nr4a3. In contrast, the pathway by which Nkx6.1 activates β-cell replication involves induction of Nr4a1 and Nr4a3 independent of VGF.

Our current and previous (6, 13) results describing proliferative effects of Nkx6.1 overexpression in rat islets differ from those reported by another laboratory (12). In that paper, conditional, transgenic overexpression of Nkx6.1 in adult mouse islet β cells had no discernable effect on β-cell proliferation. Several explanations are possible for this apparent discrepancy. (i) The extent of overexpression of Nkx6.1 might have been different in the two studies. (ii) Our studies used adenovirus vectors to deliver Nkx6.1, as opposed to a germ line-integrated transgene (12). To exclude the possibility that adenovirus-encoded genes may have contributed to proliferative effects (32), we expressed Nkx6.1 with an alternate viral (lentivirus) vector and still found Nkx6.1-mediated islet cell proliferation (Fig. 2C). (iii) Finally, in a recent study, the same group that reported no effect of Nkx6.1 overexpression in transgenic mice reported a loss of normal β-cell mass and replication in islet-specific Nkx6.1 knockout mice (33), consistent with the current observations. The identification of specific molecular mediators of the Nkx6.1-proliferative effect, such as Nr4a1, Nr4a3, APC components, and p21, and the demonstration that their regulation is required for the Nkx6.1 effect substantiates our earlier findings, as do our studies showing that knockout of Nr4a1 impairs development of normal islet β-cell mass.

It remains to be determined how our findings might translate to human β cells. We show herein that Nr4a3 overexpression in human islets causes a small but significant increase in [3H]thymidine incorporation, a clearly modest effect compared with the impact of Nkx6.1 or the Nr4a receptors on rat islet proliferation. One possibility is that human islets, which tend to be procured from adult donors, may have high levels of expression of cell cycle repressors in addition to p21, such as p27 and p16, or the absence of other signaling pathways that are permissive for replication. A recent study shows that human and rodent islets lose expression of the platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) with age, and restoration of PDGFR expression in islets from aged mice restores replicative activity while suppressing p16 function (34). Further studies will be required to determine whether Nkx6.1 engages all of the same steps in human islets as it does in rat islets and to define the potential inhibitory roles of cell cycle repressors in adult human islets.

Methods

Cell Culture and Reagents.

Male Wistar rats were purchased from Harlan and maintained on standard chow diet (Teklad 7001; Harlan). Rat pancreatic islets were isolated as previously described (35). Rat studies were approved by the Duke University Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee. Wild-type and Nr4a1 knockout mice were fed ad libitum and maintained on a 12-h light–dark cycle. Mouse studies were approved by the University of California, Los Angeles Animal Research Committee. Deidentified human islets were obtained from the Integrated Islet Distribution Program (http://iidp.coh.org). Construction and use of adenovirus and lentivirus vectors is described in SI Methods.

cDNA Microarray Analysis.

Five replicate groups of rat islets were cultured overnight in the absence or presence of AdCMV-GFP, AdCMV-βGal, AdCMV-Nkx6.1, AdCMV-Nr4a1, or AdCMV-Nr4a3 adenoviruses, followed by 48 h of cell culture and preparation of total RNA (6). cDNA microarray analysis was performed on the Affymetrix Rat Genome 230 2.0 Array GeneChip (Affymetrix). Data analysis was performed as described in SI Methods.

ChIP Assays.

ChIP assays were performed using 832/13 cells as detailed previously (6), using anti-Nkx6.1 antiserum or normal rabbit serum. Primer sequences are provided in SI Methods.

DNA Synthesis Measured by [3H]Thymidine Incorporation.

DNA synthesis rates were measured as previously described (6). Details are provided in SI Methods.

Glucose-Stimulated Insulin Secretion.

Insulin secretion was measured at 2.5 and 16.7 mM glucose in triplicate groups of 20 islets per condition as previously described (6). Data were normalized against total protein determined by binchoninic acid assay (Pierce), and insulin content was measured as described (6).

Immunoblot Analyses.

Immunoblot analysis methods are described in SI Methods.

Quantitative RT-PCR.

Rat Nr4a1, Nr4a3, E2F1, cyclin E1, p21, and Ube2c mRNA levels were measured by quantitative RT-PCR as previously described (15). All primer sequences are available upon request.

Histology and Immunofluorescence.

Pancreata were fixed in neutral-buffered formalin followed by paraffin embedding and stained for insulin, Ki-67, γH2AX, and PHH3, as described in SI Methods.

EdU Incorporation and Cell Cycle Progression.

Islets were cultured with 10 µM EdU, with daily medium changes, for 96 h. Islets were dispersed on poly-d-lysine–coated coverslips (BD). EdU was detected using the AlexaFluor 555 EdU cell proliferation kit (Invitrogen). Five sections containing ≥400 nuclei were evaluated for EdU and PHH3 signals using ImageJ software for each condition.

Statistical Analysis.

Data are presented as means ± SEM. Data were analyzed by the paired Student t test or by ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc analysis for multiple group comparisons.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Duke Microarray Core facility for assistance with microarray experiments. This work was supported by Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Grant 17-2011-15 and National Institutes of Health/Beta Cell Biology Consortium Grant U01 DK-089538 (to C.B.N.), a postdoctoral fellowship from the American Diabetes Association (to J.S.T.), and a generous gift from Mr. Robert Mercer and family.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (accession no. GSE55079).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1320953111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Weir GC, Bonner-Weir S. Five stages of evolving beta-cell dysfunction during progression to diabetes. Diabetes. 2004;53(Suppl 3):S16–S21. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.suppl_3.s16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muoio DM, Newgard CB. Mechanisms of disease: Molecular and metabolic mechanisms of insulin resistance and beta-cell failure in type 2 diabetes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9(3):193–205. doi: 10.1038/nrm2327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butler AE, et al. Adaptive changes in pancreatic beta cell fractional area and beta cell turnover in human pregnancy. Diabetologia. 2010;53(10):2167–2176. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1809-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tarabra E, Pelengaris S, Khan M. A simple matter of life and death-the trials of postnatal Beta-cell mass regulation. Int J Endocrinol. 2012;2012:516718. doi: 10.1155/2012/516718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sander M, et al. Homeobox gene Nkx6.1 lies downstream of Nkx2.2 in the major pathway of beta-cell formation in the pancreas. Development. 2000;127(24):5533–5540. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.24.5533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schisler JC, et al. Stimulation of human and rat islet beta-cell proliferation with retention of function by the homeodomain transcription factor Nkx6.1. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28(10):3465–3476. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01791-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maxwell MA, Muscat GE. The NR4A subgroup: Immediate early response genes with pleiotropic physiological roles. Nucl Recept Signal. 2006;4:e002. doi: 10.1621/nrs.04002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chao LC, et al. Insulin resistance and altered systemic glucose metabolism in mice lacking Nur77. Diabetes. 2009;58(12):2788–2796. doi: 10.2337/db09-0763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weyrich P, et al. Common polymorphisms within the NR4A3 locus, encoding the orphan nuclear receptor Nor-1, are associated with enhanced beta-cell function in non-diabetic subjects. BMC Med Genet. 2009;10:77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-10-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nomiyama T, et al. The NR4A orphan nuclear receptor NOR1 is induced by platelet-derived growth factor and mediates vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(44):33467–33476. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603436200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hallstrom TC, Mori S, Nevins JR. An E2F1-dependent gene expression program that determines the balance between proliferation and cell death. Cancer Cell. 2008;13(1):11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schaffer AE, Yang AJ, Thorel F, Herrera PL, Sander M. Transgenic overexpression of the transcription factor Nkx6.1 in β-cells of mice does not increase β-cell proliferation, β-cell mass, or improve glucose clearance. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25(11):1904–1914. doi: 10.1210/me.2011-1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayes HL, et al. Pdx-1 activates islet α- and β-cell proliferation via a mechanism regulated by transient receptor potential cation channels 3 and 6 and extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33(20):4017–4029. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00469-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rieck S, et al. Overexpression of hepatocyte nuclear factor-4α initiates cell cycle entry, but is not sufficient to promote β-cell expansion in human islets. Mol Endocrinol. 2012;26(9):1590–1602. doi: 10.1210/me.2012-1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stephens SB, et al. A VGF-derived peptide attenuates development of type 2 diabetes via enhancement of islet β-cell survival and function. Cell Metab. 2012;16(1):33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pei L, et al. NR4A orphan nuclear receptors are transcriptional regulators of hepatic glucose metabolism. Nat Med. 2006;12(9):1048–1055. doi: 10.1038/nm1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chao LC, et al. Nur77 coordinately regulates expression of genes linked to glucose metabolism in skeletal muscle. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21(9):2152–2163. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chao LC, et al. Skeletal muscle Nur77 expression enhances oxidative metabolism and substrate utilization. J Lipid Res. 2012;53(12):2610–2619. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M029355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tessem JS, et al. Critical roles for macrophages in islet angiogenesis and maintenance during pancreatic degeneration. Diabetes. 2008;57(6):1605–1617. doi: 10.2337/db07-1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amador V, Ge S, Santamaría PG, Guardavaccaro D, Pagano M. APC/C(Cdc20) controls the ubiquitin-mediated degradation of p21 in prometaphase. Mol Cell. 2007;27(3):462–473. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ackermann AM, Gannon M. Molecular regulation of pancreatic beta-cell mass development, maintenance, and expansion. J Mol Endocrinol. 2007;38(1-2):193–206. doi: 10.1677/JME-06-0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perl S, et al. Significant human beta-cell turnover is limited to the first three decades of life as determined by in vivo thymidine analog incorporation and radiocarbon dating. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(10):E234–E239. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferrannini E, et al. beta-cell function in obesity: Effects of weight loss. Diabetes. 2004;53(Suppl 3):S26–S33. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.suppl_3.s26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Milbrandt J. Nerve growth factor induces a gene homologous to the glucocorticoid receptor gene. Neuron. 1988;1(3):183–188. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90138-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pearen MA, Muscat GE. Minireview: Nuclear hormone receptor 4A signaling: Implications for metabolic disease. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24(10):1891–1903. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li QX, Ke N, Sundaram R, Wong-Staal F. NR4A1, 2, 3—an orphan nuclear hormone receptor family involved in cell apoptosis and carcinogenesis. Histol Histopathol. 2006;21(5):533–540. doi: 10.14670/HH-21.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohtani K, DeGregori J, Nevins JR. Regulation of the cyclin E gene by transcription factor E2F1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92(26):12146–12150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lipkowitz S, Weissman AM. RINGs of good and evil: RING finger ubiquitin ligases at the crossroads of tumour suppression and oncogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(9):629–643. doi: 10.1038/nrc3120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tschen SI, Georgia S, Dhawan S, Bhushan A. Skp2 is required for incretin hormone-mediated β-cell proliferation. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25(12):2134–2143. doi: 10.1210/me.2011-1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cozar-Castellano I, Haught M, Stewart AF. The cell cycle inhibitory protein p21cip is not essential for maintaining beta-cell cycle arrest or beta-cell function in vivo. Diabetes. 2006;55(12):3271–3278. doi: 10.2337/db06-0627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Briand O, et al. The nuclear orphan receptor Nur77 is a lipotoxicity sensor regulating glucose-induced insulin secretion in pancreatic β-cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2012;26(3):399–413. doi: 10.1210/me.2011-1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCaffrey AP, et al. The host response to adenovirus, helper-dependent adenovirus, and adeno-associated virus in mouse liver. Mol Ther. 2008;16(5):931–941. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor BL, Liu F, Sander M. Nkx6.1 is essential for maintaining the functional state of pancreatic beta cells. Cell Rep. 2013;4(6):1262–1275. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen H, et al. PDGF signalling controls age-dependent proliferation in pancreatic β-cells. Nature. 2011;478(7369):349–355. doi: 10.1038/nature10502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bain JR, Schisler JC, Takeuchi K, Newgard CB, Becker TC. An adenovirus vector for efficient RNA interference-mediated suppression of target genes in insulinoma cells and pancreatic islets of langerhans. Diabetes. 2004;53(9):2190–2194. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.9.2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.