Abstract

Studies examining serotonin-1B (5-HT1B) receptor manipulations on cocaine self-administration and cocaine-seeking behavior initially seemed discrepant. However, we recently suggested based on viral-mediated 5-HT1B-receptor gene transfer that the discrepancies are likely due to differences in the length of abstinence from cocaine prior to testing. To further validate our findings pharmacologically, we examined the effects of the selective 5-HT1B receptor agonist CP 94,253 (5.6 mg/kg, s.c.) on cocaine self-administration during maintenance and after a period of protracted abstinence with or without daily extinction training. We also examined agonist effects on cocaine-seeking behavior at different time points during abstinence. During maintenance, CP 94,253 shifted the cocaine self-administration dose–effect function on an FR5 schedule of reinforcement to the left, whereas following 21 days of abstinence CP 94,253 downshifted the function and also decreased responding on a progressive ratio schedule of reinforcement regardless of extinction history. CP 94,253 also attenuated cue-elicited and cocaine-primed drug-seeking behavior following 5 days, but not 1 day, of forced abstinence. The attenuating effects of CP 94,253 on the descending limb of the cocaine dose–effect function were blocked by the selective 5-HT1B receptor antagonist SB 224289 (5 mg/kg, i.p.) at both time points, indicating 5-HT1B receptor mediation. The results support a switch in 5-HT1B receptor modulation of cocaine reinforcement from facilitatory during self-administration maintenance to inhibitory during protracted abstinence. These findings suggest that the 5-HT1B receptor may be a novel target for developing medication for treating cocaine dependence.

Keywords: Addiction, serotonin, reinforcement, reinstatement, relapse, reward

Serotonin-1B (5-HT1B) receptors are located on axon terminals throughout the central nervous system where they function as auto- and heteroreceptors exerting inhibitory control over neuronal activity through negative coupling with adenylate cyclase.1,2 Polymorphisms in the 5-HT1B receptor gene are linked to substance abuse.3−7 5-HT1B receptors are involved in the behavioral effects of cocaine; however, the nature of their modulatory effects on cocaine abuse-related behaviors has been inconclusive due to discrepancies across studies investigating their role in the reinforcing, rewarding, and incentive motivational effects of cocaine (for review, see refs (8 and 9)). For instance, 5-HT1B receptor knockout mice self-administer more cocaine on a progressive ratio (PR) schedule than controls, suggesting that 5-HT1B receptors inhibit cocaine reinforcement and/or motivation for cocaine.10,11 In contrast, in rats, 5-HT1B receptor agonists shift the cocaine dose–effect function to the left on a fixed ratio (FR) schedule and increase cocaine intake on a PR schedule, suggesting that 5-HT1B receptors enhance cocaine reinforcement and motivation for cocaine.12−14 Additionally, 5-HT1B receptor knockout mice do not display cocaine-conditioned place preference (CPP),15 whereas in rats 5-HT1B receptor agonists enhance cocaine-CPP but produce conditioned place aversion when administered alone.16 5-HT1B receptor agonists also elevate intracranial self-stimulation thresholds and prevent cocaine-induced decreases in intracranial self-stimulation thresholds, suggesting that these receptors inhibit cocaine reward.17 Finally, 5-HT1B receptor agonists decrease cue-elicited and cocaine-primed reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior, suggesting that these receptors attenuate incentive motivation for cocaine.14,18,19

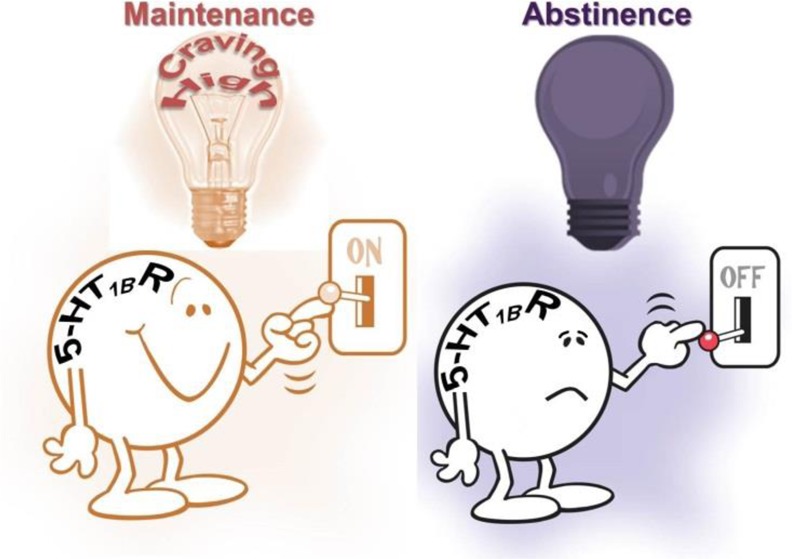

The amount of cocaine exposure and subsequent abstinence varies across studies examining the effects of 5-HT1B receptors on cocaine abuse-related behaviors, which may account for the discrepant findings. Indeed, using viral-mediated 5-HT1B-receptor gene transfer into the medial nucleus accumbens shell, we recently reported differential effects of increased 5-HT1B receptor expression on cocaine abuse-related behaviors that varied depending on the stage of the addiction cycle. Specifically, during ongoing maintenance of self-administration, viral-mediated 5-HT1B-receptor gene transfer shifts the cocaine dose–effect function upward and to the left on a FR5 schedule, and increases breakpoints and cocaine intake on a PR schedule.20 In contrast, following 21 days of forced abstinence viral-mediated 5-HT1B-receptor gene transfer attenuates cue-elicited and cocaine-primed reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior, and decreases cocaine intake and breakpoints on a PR schedule. These unique patterns of effects suggest that the role of 5-HT1B receptors in the behavioral effects of cocaine vary depending on the stage of the addiction cycle, with a facilitatory role during periods of ongoing drug use (i.e., maintenance phase) and an inhibitory role during extended abstinence.

The present study sought to further test our hypothesis that extended abstinence from chronic cocaine self-administration switches the functional effects of 5-HT1B receptor stimulation from facilitation to inhibition of both the reinforcing and incentive motivational effects of cocaine. Rats were tested for the effects of the selective 5-HT1B receptor agonist CP 94,253 (5.6 mg/kg, s.c.) on drug intake during ongoing maintenance of cocaine self-administration across a range of cocaine doses (0.0–0.75 mg/kg, i.v.), and a separate cohort was tested for CP 94,253 (5.6 mg/kg, s.c.) effects on drug intake after 21 days of forced abstinence with a dose of cocaine available on either the ascending limb of the dose–effect function (0.075 mg/kg, i.v.) or on the descending limb of the function (0.75 mg/kg, i.v.). Subsequently, we examined whether the effects of CP 94,253 on cocaine self-administration (0.75 mg/kg, i.v.) observed during maintenance and protracted abstinence are blocked by the selective 5-HT1B receptor antagonist SB 224289 (5 mg/kg, i.p.). Additionally, we examined the effects of CP 94,253 (5.6 mg/kg, s.c.) on breakpoints and cocaine intake (0.375 mg/kg, i.v.) on an exponential PR schedule of reinforcement in rats that underwent 21 days of extinction training or forced abstinence. Finally, we investigated the effects of CP 94,253 on cue-elicited and cocaine-primed drug-seeking behavior during either acute (1 day) or protracted (5 days) abstinence. We hypothesized that CP 94,253 would enhance incentive motivation for cocaine and the reinforcing value of cocaine when examined within 24 h of a self-administration session, resulting in a leftward shift of the cocaine self-administration dose–effect function, and an increase in cue-elicited and cocaine-primed drug-seeking behavior. In contrast, we hypothesized a functional switch in 5-HT1B receptor effects after 5 or more days of abstinence, resulting in decreases in cocaine self-administration on both the FR5 and PR schedules of reinforcement, and decreases in cue-elicited and cocaine-primed drug-seeking behavior.

Results and Discussion

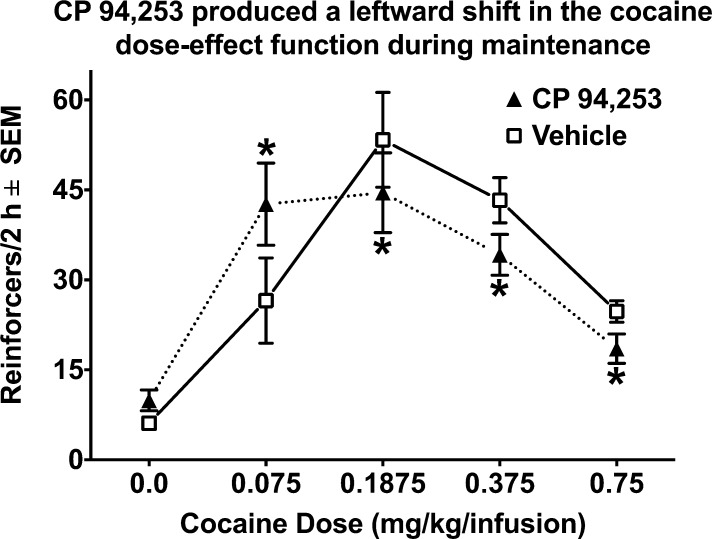

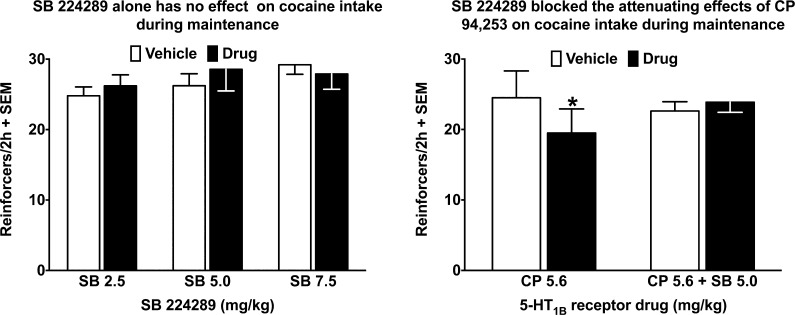

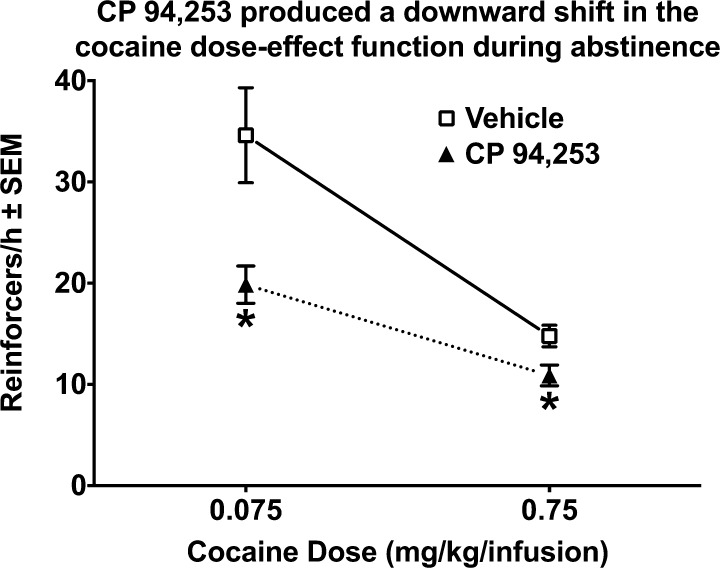

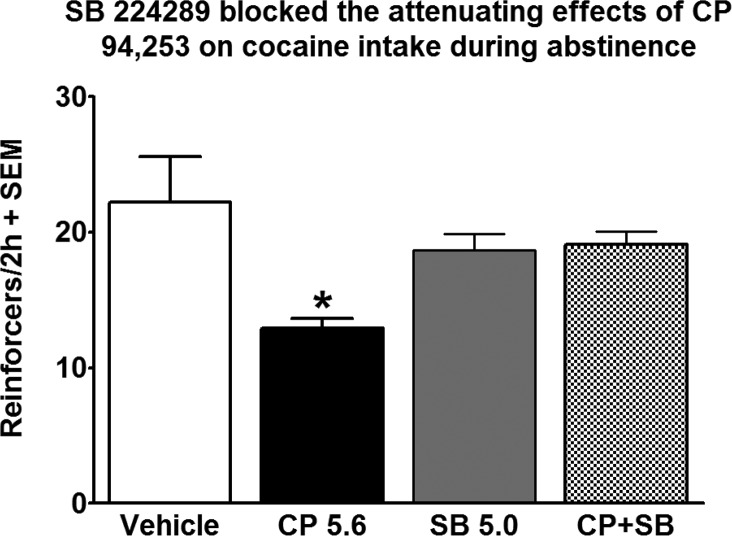

The present results provide convincing pharmacological support for the hypothesis that cocaine reinforcement is facilitated by stimulation of 5-HT1B receptors during maintenance of self-administration and inhibited following periods of protracted abstinence. Similar to previous research,12−14 we found that the selective 5-HT1B receptor agonist CP 94,253 (5.6 mg/kg, s.c.) produced a leftward shift in the cocaine self-administration dose–effect function during maintenance (Figure 1), effects similar to increasing the unit dose of cocaine. The effects of CP 94,253 on the descending limb of the cocaine dose–effect function were blocked by the selective 5-HT1B receptor antagonist SB 224289 (5.0 mg/kg, i.p.), which produced no discernible effects on its own (Figure 3), suggesting that stimulation of 5-HT1B receptors enhances the reinforcing effects of cocaine during maintenance. In striking contrast, following 21 days of forced abstinence, CP 94,253 (5.6 mg/kg, s.c.) decreased cocaine intake on both the ascending (0.075 mg/kg, i.v.) and descending (0.75 mg/kg, i.v.) limbs of the cocaine dose–effect function (Figure 2), with the latter effect blocked by the 5-HT1B receptor antagonist SB 224289 (5.0 mg/kg, i.p.; Figure 4). The decrease in cocaine intake at both doses tested during protracted abstinence suggests that CP 94,253 flattens the cocaine dose–effect function rather than producing a shift to the left or right. The finding that best highlights a switch in the functional effects of 5-HT1B receptors is that during maintenance CP 94,253 pretreatment enhances intake of 0.075 mg/kg, i.v. cocaine relative to vehicle pretreatment, whereas after 21 days of abstinence this same CP 94,253 pretreatment attenuates intake of 0.075 mg/kg, i.v. cocaine relative to vehicle pretreatment.

Figure 1.

Effects of the 5-HT1B receptor agonist CP 94,253 on cocaine self-administration under a fixed ratio (FR) 5 schedule of reinforcement during maintenance. Data are expressed as the number of reinforcers obtained (±SEM) at each dose on the cocaine dose–effect function (0.0–0.75 mg/kg, i.v.). For each cocaine dose, rats (n = 12) were pretreated with vehicle (1 mL/kg, s.c.; open squares) or CP 94,253 (5.6 mg/kg, s.c.; closed triangles) 15 min before FR5 testing using a within-subjects design, with order of pretreatment (i.e., vehicle or CP 94,253) counterbalanced. Under the vehicle pretreatment condition, varying the unit dose of cocaine produced a characteristic inverted U-shaped cocaine dose–effect function, with a main effect of cocaine dose [F(4,40) = 15.13, p < 0.0000001]. Increasing the unit dose of cocaine reliably increased (ascending limb) or decreased (descending limb) cocaine intake at each dose relative to the previous dose (p < 0.05 in each case). There was a cocaine dose by CP 94,253 pretreatment interaction [F(4,40) = 13.38, p < 0.000001]. Compared to vehicle pretreatment, CP 94,253 shifted the cocaine dose–effect function to the left, increasing cocaine intake on the ascending limb (0.075 mg/kg, i.v.) and decreasing cocaine intake on the descending limb (0.1875, 0.375, and 0.75 mg/kg, i.v.; p < 0.05 in each case), similar to the effect of increasing the unit dose of cocaine. When saline was substituted for cocaine, CP 94,253 failed to alter self-administration rates (i.e., 0.0 mg/kg, i.v.). Asterisk (*) represents a difference from vehicle pretreatment (Newman-Keuls, p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Effects of the 5-HT1B receptor antagonist SB 224289 administered alone (left) or in combination with CP 94,253 (right) on cocaine self-administration under a fixed ratio (FR) 5 schedule of reinforcement during maintenance. Data are expressed as the number of reinforcers obtained (±SEM) at a dose previously found to be on the descending (0.75 mg/kg/0.1 mL, i.v.) limb of the cocaine dose–effect function (see Figure 1). Prior to testing, there were no differences between SB 224289 and CP 94,253 groups in the number of cocaine reinforcers (0.75 mg/kg/0.1 mL, i.v.) obtained during cocaine self-administration training (data not shown). Rats (n = 8–10/5-HT1B receptor ligand group) were pretreated with vehicle (1 mL/kg, s.c.; white bars) on one test day and their assigned 5-HT1B receptor drug(s; black bars) [SB 224289 (2.5, 5.0, or 7.5 mg/kg, i.p.); CP 94,253 (5.6 mg/kg, s.c.); or CP 94,253 (5.6 mg/kg, s.c.) + SB 224289 (5 mg/kg, i.p.)] on the other test day, with order of pretreatment (i.e., vehicle or 5-HT1B receptor ligand) counterbalanced. Each rat received two injections prior to the test: SB 224289 or vehicle 60 min prior to the test and CP 94,253 or vehicle 15 min prior to the test. There was a significant effect of 5-HT1B receptor ligand pretreatment on cocaine intake [F(4, 40) = 3.45, p < 0.05]. Compared to vehicle pretreatment, CP 94,253 attenuated cocaine intake (p < 0.05). SB 224289 administered alone failed to alter cocaine intake, but blocked the attenuating effect of CP 94,253. Asterisk (*) represents a difference from vehicle pretreatment (Newman-Keuls, p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Effects of the 5-HT1B receptor agonist CP 94,253 on cocaine self-administration under a fixed ratio (FR) 5 schedule of reinforcement following 21 days of forced abstinence. Data are expressed as the number of cocaine reinforcers obtained (±SEM) at doses previously found to be on the ascending (0.075 mg/kg/0.1 mL, i.v.) and descending (0.75 mg/kg/0.1 mL, i.v.) limbs of the cocaine dose–effect function (see Figure 1). Prior to testing, there were no differences between vehicle and CP 94,253 groups in the number of cocaine reinforcers (0.75 mg/kg/0.1 mL, i.v.) obtained during cocaine self-administration training (data not shown). Rats (n = 7–9/group) were pretreated with vehicle (1 mL/kg, s.c.; open squares) or CP 94,253 (5.6 mg/kg, s.c.; closed triangles) 15 min before FR5 testing. There was a cocaine dose by CP 94,253 pretreatment interaction [F(1, 29) = 4.56, p < 0.05], with subsequent analysis indicating that CP 94,253 attenuated cocaine intake on both the ascending [t (13) = 2.77, p < 0.05] and descending [t (16) = 2.62, p < 0.05] limbs of the cocaine dose–effect function compared to vehicle treated rats. Asterisk (*) represents a difference from vehicle, independent sample t tests.

Figure 4.

Effects of the 5-HT1B receptor antagonist SB 224289 administered alone or in combination with CP 94,253 on cocaine self-administration under a fixed ratio (FR) 5 schedule of reinforcement following 21 days of forced abstinence. Data are expressed as the number of reinforcers obtained (±SEM) at a dose previously found to be on the descending (0.75 mg/kg/0.1 mL, i.v.) limb of the cocaine dose–effect function (see Figure 1). Prior to testing, there were no differences between vehicle, SB 224289 and CP 94,253 groups in the number of cocaine reinforcers (0.75 mg/kg/0.1 mL, i.v.) obtained during cocaine self-administration training (data not shown). Each rat received two injections prior to the test: SB 224289 or vehicle 60 min prior to the test and CP 94,253 or vehicle 15 min prior to the test. The design resulted in four groups (n = 10–12/group) designated as vehicle (white bar), SB 224289 (5.0 mg/kg, i.p.; gray bar), CP 94,253 (5.6 mg/kg, s.c.; black bar), or CP 94,253 (5.6 mg/kg, s.c.) + SB 224289 (5 mg/kg, i.p.; hatched bar). There was a significant effect of 5-HT1B receptor ligand on cocaine intake [F(3, 38) = 4.29, p < 0.05]. Compared to vehicle controls, CP 94,253 attenuated cocaine intake (p < 0.05). SB 224289 administered alone failed to alter cocaine intake, but blocked the attenuating effect of CP 94,253. Asterisk (*) represents a difference from all other groups (Newman-Keuls, p < 0.05).

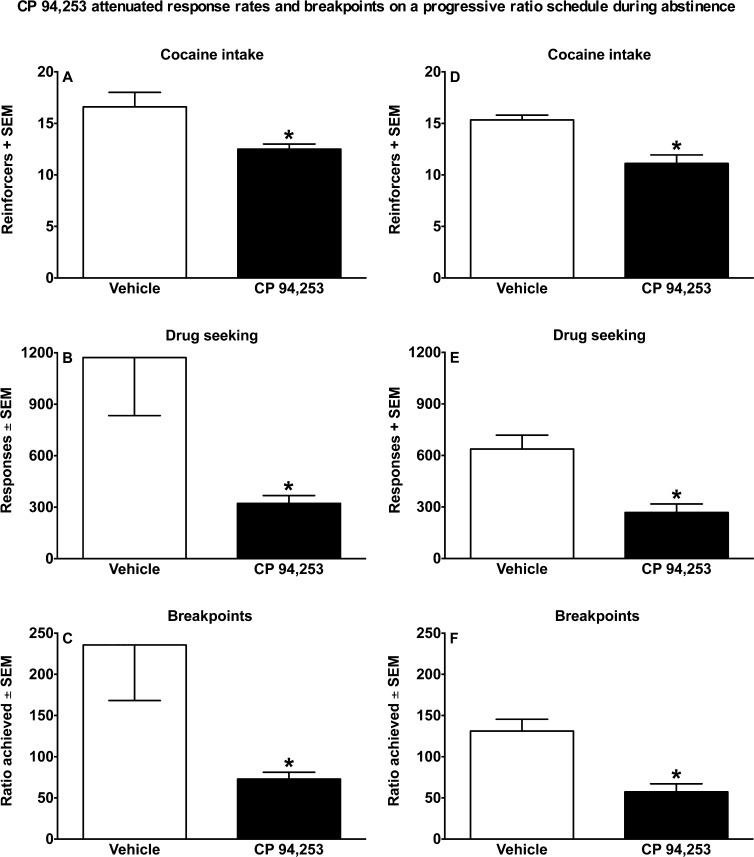

The attenuating effects of CP 94,253 on cocaine self-administration during protracted abstinence were independent of reinforcement schedule since reductions in cocaine intake, active lever responding, and the highest ratio achieved (i.e., breakpoints) were also detected on a PR schedule of reinforcement following 21 days of forced abstinence (Figure 5). The attenuating effects of CP 94,253 on PR responding for cocaine are opposite of those reported by Parsons et al.12 who tested rats without a period of prolonged abstinence. The attenuating effects of CP 94,253 on PR responding in the present study were independent of extinction as cocaine intake was reduced in rats with (Figure 5A) or without (Figure 5D) a history of extinction training. Thus, the agonist attenuation effect is not likely related to facilitation of extinction learning. The agonist attenuation effect is consistent with our previous research showing that rats with increased expression of 5-HT1B receptors in terminals of the medial nucleus accumbens shell exhibit an increase in cocaine intake on a PR schedule when tested during maintenance of cocaine self-administration and a decrease when tested during protracted abstinence.20 Collectively, the findings on the role of 5-HT1B receptors on cocaine self-administration strongly support the idea that there is a functional switch from a facilitatory role during maintenance of self-administration to an inhibitory role during protracted abstinence.

Figure 5.

Effects of the 5-HT1B receptor agonist CP 94,253 on cocaine self-administration under an exponential progressive ratio (PR) schedule of reinforcement following extinction training (A, B and C; 17 sessions across 21 days) or forced abstinence (D, E, and F; 21 days). Data are expressed as the number of cocaine reinforcers (0.375 mg/kg/0.1 mL, i.v.) obtained (A and D), the number of active lever responses emitted (B and E), and the highest ratios achieved (C and F) during the 3 h PR test session (±SEM). Prior to testing, there were no differences between vehicle and CP 94,253 pretreatment groups in the number of cocaine reinforcers obtained on their training dose (0.75 mg/kg/i.v.) or on their PR test dose (0.375 mg/kg, i.v.) during self-administration training (data not shown), or response rates during extinction training (data not shown). Rats (n = 9–10/group) were pretreated with vehicle (1 mL/kg, s.c.; white bars) or CP 94,253 (5.6 mg/kg, s.c.; black bars) 15 min before PR testing. There were significant effects of CP 94,253 on cocaine intake [F(1, 34) = 20.98, p < 0.001], active lever pressing [F(1, 34) = 10.75, p < 0.005], and the highest ratio achieved [F(1, 34) = 10.31, p < 0.005]. Subsequent analyses indicated that regardless of extinction history, CP 94,253 attenuated cocaine intake [Extinction: t (18) = 2.74, p < 0.05; Abstinence: t (16) = 4.45, p < 0.001], active lever pressing [Extinction: t (18) = 2.49, p < 0.05; Abstinence: t (16) = 3.91, p < 0.005], and the highest ratio achieved [Extinction: t (18) = 2.40, p < 0.05; Abstinence: t (16) = 4.28, p < 0.005] compared to vehicle-treated rats. Asterisk (*) represents a difference from vehicle, independent sample t tests.

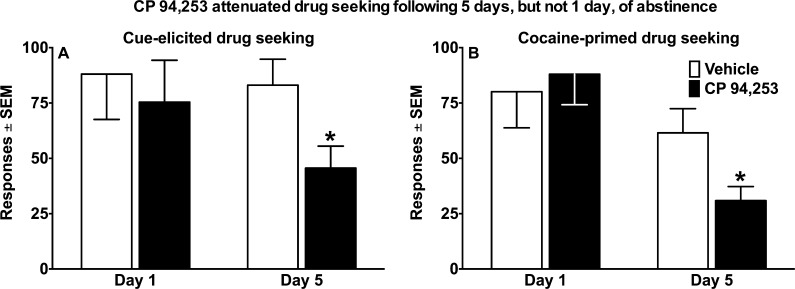

Stimulation of 5-HT1B receptors also attenuated cocaine-seeking behavior in a manner dependent on the length of abstinence from cocaine self-administration. Indeed, CP 94,253 attenuated both cue-elicited and cocaine-primed drug-seeking behavior following 5 days, but not 1 day, of forced abstinence (Figure 6). These effects are consistent with previous reports indicating that following 10–21 days of extinction training (i.e., abstinence), systemic 5-HT1B receptor agonist administration14,18,19 or increased 5-HT1B receptor expression using viral-mediated gene transfer (20) attenuates cue-elicited and cocaine-primed reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior. The present findings suggest that the 5-HT1B receptor agonist-induced attenuation of cocaine-seeking behavior emerges during the course of abstinence, effects that may result from abstinence-induced changes in 5-HT1B receptor expression.21 Contrary to our prediction, CP 94,253 did not increase drug seeking following acute (i.e., 24 h) abstinence. Several possible explanations for this lack of effect include (1) 1 h test sessions for the seeking experiments were too short compared to 2 h (present report) and 3 h12−14 self-administration test sessions; (2) differential effects of 5-HT1B receptor stimulation on cocaine reinforcement versus cocaine-seeking behavior during acute (1 day) but not protracted (≥5 days) abstinence; and/or (3) acute abstinence effects may depend on the amount of cocaine history, which varied across studies. Further research is needed to fully delineate the role of 5-HT1B receptors in cocaine-seeking behavior during acute abstinence.

Figure 6.

Effects of the 5-HT1B receptor agonist CP 94,253 on cocaine-seeking behavior following 1 or 5 days of forced abstinence. Data are expressed as the number of active lever responses emitted (±SEM) during tests for cue-elicited (A) and cocaine-primed (B) drug seeking. On both test days, rats first received a 2 h extinction session, then they received their assigned drug treatments, and 15 min later were returned to the self-administration chambers for a 1 h cue-elicited (A) or cocaine-primed (B) drug-seeking test. Rats (n = 10/test modality) were pretreated with vehicle (1 mL/kg, s.c.; white bars) or CP 94,253 (5.6 mg/kg, s.c.; black bars) 15 min before testing on abstinence day 1. On abstinence day 5, the rats that received vehicle on day 1 were pretreated with CP 94,253 (5.6 mg/kg, s.c.; black bars), whereas those that received CP 94,253 on day 1 received vehicle (white bars). The groups and the order in which the testing occurred were counterbalanced for the number of cocaine reinforcers (0.75 mg/kg/0.1 mL, i.v.) obtained during cocaine self-administration training (data not shown). For the cue-elicited seeking phase, cues were available response-contingently during the 1 h test sessions on a fixed ratio (FR) 1 schedule of reinforcement. For the cocaine-primed seeking phase, the cocaine prime (10 mg/kg, i.p.) was administered immediately before testing and no cues were presented during the 1 h test sessions. Compared to vehicle pretreatment, CP 94,253 attenuated cue-elicited [t (18) = 2.45, p < 0.05] and cocaine-primed [t (15) = 2.49, p < 0.05] cocaine-seeking behavior following 5 days, but not 1 day, of forced abstinence. Asterisk (*) represents a difference from vehicle pretreatment, independent sample t tests.

A previous report suggested that the effects of CP 94,253 on cocaine-seeking behavior (i.e., cue-elicited and cocaine-primed reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior) may not be 5-HT1B-receptor mediated because the inhibitory effects of CP 94,253 are not blocked by the 5-HT1B receptor antagonists SB 216641 or GR 127935, and these antagonists administered alone attenuate cue-elicited and cocaine-primed reinstatement.19 The nonspecific effects observed in the previous study are surprising given that (1) SB 216641 blocks the attenuating effects of CP 94,253 on food-seeking behavior;19 (2) GR 127935 blocks the attenuating effects of the 5-HT1B/1A receptor agonist RU 24969 on cue-elicited and cocaine-primed reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior;18 (3) both GR 12793512 and SB 21664113 block the inhibitory effects of CP 94,253 on cocaine self-administration; and (4) SB 216641 blocks CP 94,253-induced reductions in amphetamine self-administration.22 CP 94,253 is a potent, selective 5-HT1B receptor agonist with a Ki (nM) of 2 at 5-HT1B receptors compared to values of 89 and 49 at 5-HT1A and 5-HT1D receptors, respectively, and CP 94,253 has little or no affinity for 5-HT1E, 5-HT1F, 5-HT2, 5-HT3, D1, D2, α1, α2, β-adrenergic, muscarinic, GABAergic, histamine, or opiate receptors.23 Importantly, the present results indicate that the selective 5-HT1B receptor antagonist SB 224289 blocked the inhibitory effects of CP 94,253 on cocaine intake during both maintenance and protracted abstinence without altering self-administration at either time point when administered alone (Figures 3 and 4). SB 224289 is a selective 5-HT1B receptor antagonist with negative intrinsic activity.24 Indeed, SB 224289 has a high affinity for 5-HT1B receptors (pKi = 8.2) and displays over 75 fold selectivity for 5-HT1B receptors compared to all other 5-HT receptors (pKi < 6.2 for each receptor). Furthermore, increasing the expression of 5-HT1B receptors in terminals of nucleus accumbens shell projection neurons produces similar patterns of effects on cocaine intake and cocaine-seeking behaviors following protracted abstinence,20 providing converging evidence for 5-HT1B-receptor mediation.

5-HT1B receptor agonists have some effects on locomotor activity. For instance, the nonselective 5-HT1B/1A receptor agonist RU 24969 initially decreases spontaneous locomotion during acute abstinence (24 h) from cocaine self-administration, but enhances locomotion across 14 days of forced abstinence.25 Although we cannot rule out the possibility that CP 94,253 produced nonspecific effects on motor function that may have influenced operant responding, this idea is mitigated by our findings that there were no differences in inactive lever pressing between vehicle and CP 94,253 groups during maintenance or following protracted abstinence (data not shown). Furthermore, although we did not directly test the effects of CP 94,253 on locomotor activity in the present report, previously we examined CP 94,253 dose-dependent effects on locomotor activity following sucrose self-administration and we failed to detect any effect within the CP 94,253 dose range used in the present study.14 Finally, if CP 94,253 had increased locomotor activity during the course of protracted abstinence similar to the effects of RU 24969 observed previously, then we likely would have detected an increase in response rates on both the active and inactive levers rather than a selective decrease in active lever responding.

The present results suggest that 5-HT1B receptors may provide a novel pharmacological target for developing treatments for cocaine addiction. A significant challenge in treating cocaine addiction is the propensity for relapse,26,27 which can occur following extended periods of abstinence.28 Factors contributing to relapse include sampling cocaine and/or exposure to cocaine-related cues that elicit incentive motivational effects in drug abusers leading to drug craving and relapse.29−32 A troubling characteristic of drug craving is that it becomes more pronounced over the course of abstinence,33−35 a phenomenon referred to as the incubation effect.36 The present findings revealed a parallel time-dependent change in the functional effects of 5-HT1B receptors, suggesting that the incubation effect may involve compensatory changes in these receptors. The time-dependent nature of the ability of the 5-HT1B receptor agonist CP 94,253 to attenuate cocaine seeking (Figure 6) suggests that the agonist may reverse the incubation effect. Therefore, it might be possible to utilize 5-HT1B receptor agonists to time-dependently decrease the incentive motivational effects of stimuli that induce drug craving (Figure 6(14,18,19)), thereby reducing the incidence of relapse, while simultaneously reducing cocaine intake if a lapse occurs (i.e., reduced intake on FR and PR schedules during protracted abstinence; Figures 2–5).

Another challenge in developing pharmacological treatments for cocaine addiction is polydrug use.37,38 Cocaine-dependent patients frequently exhibit comorbidity for opiate and/or alcohol addiction.39−41 Interestingly, 5-HT1B receptor gene polymorphisms have been associated with substance abuse for cocaine, opiates, and alcohol.3−7 Importantly, 5-HT1B receptor agonists reduce ethanol,42,43 amphetamine,22 and cocaine12−14 intake in rodents, particularly at doses on the descending limb of the dose–effect function. Taken together, these data indicate that 5-HT1B receptors are capable of regulating intake of a variety of abused drugs and strongly suggest that 5-HT1B receptors represent a promising target for medication development for substance abuse/dependence.

Conclusions

The present findings, together with previous research, reveal a dynamic pattern of 5-HT1B-receptor modulation of cocaine abuse-related behaviors (i.e., cocaine intake and motivation for drug), with a facilitatory influence during periods of active drug use12−14,20 in striking contrast to an inhibitory influence during protracted,14,18−20 but not acute (Figure 6), abstinence. The time-dependent attenuating effects of CP 94,253 on cocaine abuse-related behaviors suggest that 5-HT1B receptors may be critical in the development of craving that emerges during the course of abstinence.33,34 Collectively, these findings suggest that 5-HT1B receptors may provide a novel target for developing treatments for cocaine addiction and that the therapeutic efficacy of these treatments likely depends on the stage of the addiction cycle.

Methods

Subjects

Adult male Sprague–Dawley rats weighing 263–355 g prior to surgery were singly housed in a climate-controlled facility with a reversed 10 h light/14 h dark cycle (lights off at 7:00 AM). All husbandry and experimentation adhered to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (2011), and all experimental procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Arizona State University. Separate groups of rats were used for each specific experiment and were naïve to all experimental manipulations.

Surgery

Catheters were implanted into jugular veins under isoflurane (2–3%) anesthesia as detailed previously.44 Rats were given 6–7 days of recovery prior to the start of cocaine self-administration training. Catheters were flushed daily with 0.1 mL saline containing heparin sodium (70 U/ml; APP Pharmaceuticals, Schaumburg, IL), and Timentin (66.7 mg/mL; GlaxoSmithKline, Research Triangle Park, NC) for 5 days following surgery. Thereafter, catheters were flushed daily with heparinized saline and Timentin to maintain catheter patency. Catheters were tested for patency periodically by administering methohexital sodium (16.7 mg/mL; Jones Pharma Inc., St. Louis, MO), which produces brief anesthetic effects only when administered i.v.

Drugs

Cocaine hydrochloride (RTI International, Research Triangle Park, NC) was dissolved in 0.9% bacteriostatic saline (Hospira Inc., Lake Forest, IL) and filtered through 0.2 μm membrane Acrodisc Syringe Filters (PALL Life Sciences, Ann Arbor, MI). CP 94,253 was dissolved in 0.9% bacteriostatic saline (pH 7.2). The dose of CP 94,253 (5.6 mg/kg, s.c.) utilized in the present experiments was based on previous research indicating that this is the minimally effective dose capable of altering both cocaine self-administration and cocaine-seeking behavior (i.e., cue- and cocaine-primed reinstatement testing).13,14,19 SB 224289 was dissolved in 0.9% bacteriostatic saline containing 10% 2-hydroxypropyl β-cyclodextrin (pH 7.2; Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The doses of SB 224289 (2.5–7.5 mg/kg, i.p.) utilized in the present experiments were based on previous research indicating that SB 224289 (5 mg/kg, i.p.) blocked cocaine-induced locomotor activity.45

General Self-Administration Training

Self-administration training occurred in operant conditioning chambers (30 × 25 × 25 cm3; Med Associates, St. Albans, VT) as detailed previously.46 Briefly, rats were trained to self-administer cocaine (0.75 mg/kg/0.1 mL, i.v.), progressing from a FR1 to a FR5 schedule of reinforcement 6 days per week during 2 h sessions. Completion of the reinforcement schedule on the active lever produced the simultaneous activation of a cue light and tone generator followed 1 s later by a 6 s cocaine infusion; immediately after each infusion, a house light was activated signaling a 20 s timeout period. Throughout each session, inactive lever pressing was recorded but produced no consequences. To facilitate exploration, rats were initially restricted to 16 g of food/day beginning 2 days prior to self-administration training.47 Food restriction (16–22 g) was maintained until the final FR5 schedule was achieved for 2 consecutive days, after which rats were given ad libitum access to food for the duration of each experiment. All rats were trained on a schedule that progressed from an FR1 to an FR5 to make direct comparisons with previous reports examining the effects of CP 94,253 on cocaine self-administration and drug-seeking behavior.12−14,19 Prior to the start of each specific experiment, self-administration training continued until infusion rates stabilized, defined as less than 15% variability per session across three consecutive days with no upward or downward trends (a minimum of 11–16 sessions).

Experiment 1: Effects of CP 94,253 on FR5 Responding during Maintenance

Self-administration sessions were conducted daily, 6 days/week throughout this experiment. Rats (n = 12) were first stabilized on their training dose of cocaine (0.75 mg/kg/0.1 mL, i.v.; 17–25 sessions) and then were tested for the effects of CP 94,253 on the cocaine self-administration dose–effect function. Cocaine doses of 0.0, 0.075, 0.1875, 0.375, or 0.75 mg/kg/0.1 mL infusion, i.v. were available on an FR5 schedule of reinforcement during 2 h sessions. Rats were tested twice at each cocaine dose, and doses were presented in pseudorandom order using a within-subjects design; rats were tested first on their training dose of cocaine, and the remaining cocaine doses were tested subsequently in random order. For the two tests at a given dose of cocaine, rats received pretreatment with vehicle (1 mL/kg, s.c.) 15 min before one test and CP 94,253 (5.6 mg/kg, s.c.) 15 min before the other test, with order of pretreatment (i.e., vehicle or CP 94,253) counterbalanced. Between each test session, stable response rates were re-established using the criterion of three consecutive self-administration sessions with less than 15% variation in the total number of reinforcers earned for each cocaine dose [including the 0 dose (saline)], with no upward or downward trends.

Experiment 2: Effects of CP 94,253 on FR5 Responding during Protracted Abstinence

In this experiment, rats were tested only once for the effects of CP 94,253 on cocaine self-administration following 21 days of forced abstinence. The dose of cocaine available on the test day was either on the ascending limb (0.075 mg/kg, i.v.) or the descending limb (0.75 mg/kg, i.v.) of the cocaine dose–effect function. First, cocaine intake for all rats was stabilized on the 0.75 mg/kg, i.v. training dose across 15 training sessions. Then rats to be tested with the 0.075 mg/kg/0.1 mL, i.v. dose were given six additional training sessions with this lower dose available while the other rats continued to have the 0.75 mg/kg/0.1 mL, i.v. training dose available during these six sessions. All rats were then placed into forced abstinence for 21 days, during which they were handled and flushed daily for catheter maintenance but otherwise remained in their home cages. Rats within each cocaine test dose condition were further assigned to groups that received pretreatment with either CP 94,253 or vehicle on the test day (4 groups; n = 7–9/group). Assignment to both the cocaine dose and pretreatment conditions was counterbalanced for previous total cocaine intake. On the test day, rats received their pretreatment of vehicle (1 mL/kg, s.c.) or CP 94,253 (5.6 mg/kg, s.c.) 15 min prior to the 1 h self-administration test session. The assigned cocaine dose (0.075 or 0.75 mg/kg, i.v.) was available on an FR5 schedule of reinforcement in a manner identical to that used during self-administration training. To minimize stress of the pretreatment injection on responding during FR5 testing, rats received a vehicle injection in their home cages on days 20 and 21 of forced abstinence.

Experiment 3: Effects of SB 224289 Administered Alone or in Combination with CP 94,253 on FR5 Responding during Maintenance and Protracted Abstinence

This experiment examined the ability of the selective 5-HT1B receptor antagonist SB 224289 to block the effects of CP 94,253 on self-administration of the cocaine training dose (0.75 mg/kg) during both maintenance and protracted abstinence. Rats were first stabilized on their training dose of cocaine (0.75 mg/kg/0.1 mL, i.v.; 14–22 sessions) and then were assigned to groups tested for the effects of CP 94,253 (5.6 mg/kg, s.c.), SB 224289 (2.5, 5.0, or 7.5 mg/kg, i.p.), or CP 94,253 (5.6 mg/kg, s.c.) + SB 224289 (5.0 mg/kg, i.p.) on cocaine intake during both maintenance and protracted abstinence. Prior to testing, there were no differences between groups in the number of cocaine reinforcers (0.75 mg/kg/0.1 mL, i.v.) obtained during cocaine self-administration training (data not shown). During maintenance testing, all rats were tested twice using a within-subjects design, receiving vehicle prior to one test and their assigned 5-HT1B receptor drug(s) prior to the other test, with order of pretreatment counterbalanced. Rats (n = 8–10/5-HT1B receptor drug group) received the SB 224289 pretreatment 60 min before the test and the CP 94,253 pretreatment 15 min before the other test; matched vehicle injections (1 mL/kg, s.c. and i.p.) were administered at 15 and 60 min where appropriate. Between each test session, stable response rates were established using the criterion of three consecutive self-administration sessions with less than 15% variation in the total number of reinforcers earned, with no upward or downward trends. Following both vehicle and 5-HT1B receptor ligand tests, subjects were restabilized for cocaine infusion rates (0.75 mg/kg) and then were placed into forced abstinence.

Following 21 days of forced abstinence, rats were reassigned to either a vehicle or a 5-HT1B receptor ligand drug group [SB 224289 (5.0 mg/kg, i.p.); CP 94,253 (5.6 mg/kg, s.c.); or CP 94,253 + SB 224289]. During protracted abstinence testing, rats (n = 10–12/group) were tested once using a between subjects design, receiving CP 94,253 15 min before the test and/or SB 224289 pretreatment 60 min before the test; matched vehicle injections (1 mL/kg, s.c. and i.p.) were administered at 15 and 60 min where appropriate. Group assignments for the vehicle and 5-HT1B receptor ligand groups during protracted abstinence were counterbalanced for cocaine and 5-HT1B receptor ligand history during maintenance training and testing, respectively.

Experiment 4: Effects of CP 94,253 on PR Responding during Protracted Abstinence

Rats first underwent self-administration training at the 0.75 mg/kg, i.v. dose of cocaine on an FR5 schedule of reinforcement as described in the general methods. They then continued daily training on a PR schedule that progressed exponentially from an FR1 according to the formula 5 × exp(0.2n) – 5,48 with n reflecting the number of reinforcers the rat received during the session. The dose of cocaine available during the PR sessions was lowered to 0.375 mg/kg, i.v. because individual differences, which are presumably due to the reinforcer efficacy needed to maintain responding under higher response demands, are magnified at lower cocaine doses.49,50 PR sessions continued until rats reached their breakpoint, which was defined as the highest ratio attained once rats failed to receive a cocaine infusion during a 1 h period. All rats received a minimum of three PR sessions (15–20 total training sessions) during which stable cocaine intake was achieved. Following their last PR self-administration training session, rats were assigned to groups that underwent either extinction training (6 sessions/week for a total of 17 sessions across 21 days of abstinence; n = 22) or forced abstinence (21 days of abstinence; n = 22). Group assignment was counterbalanced for previous cocaine intake. Throughout extinction, rats were connected to the tethers and lever responses were recorded but produced no consequences (i.e., the cocaine infusion pump was not activated, and the light and tone cues were withheld). Active lever responding in the absence of cocaine and/or cue reinforcement is our operational definition of cocaine-seeking behavior. Rats within the abstinence and extinction conditions were further assigned to drug pretreatment groups (i.e., CP 94,253 or vehicle) counterbalanced for previous total cocaine intake. Parameters for PR testing were identical to those described above for PR self-administration training. On the test day, rats received their pretreatment of either vehicle (1 mL/kg, s.c.) or CP 94,253 (5.6 mg/kg, s.c.) 15 min prior to PR self-administration testing. To control for injection stress effects on responding during PR testing, rats received a vehicle injection 15 min before their last two extinction sessions or in the home cages on days 20 and 21 of forced abstinence. Test sessions were capped at 3 h in order to prevent CP 94,253 washout during PR test sessions.

Experiment 5: Effects of CP 94,253 on Cue-Elicited and Cocaine-Primed Drug-Seeking Behavior during Acute or Protracted Abstinence

The effects of CP 94,253 on cue-elicited and cocaine-primed drug-seeking behavior were assessed following acute (1 day) and protracted abstinence (5 days). Rats (n = 40) were first trained to self-administer cocaine (0.75 mg/kg/0.1 mL, i.v.) until responding stabilized (17–20 sessions). Then rats were assigned to groups that were tested for either cue-elicited (n = 20) or cocaine-primed (n = 20) drug seeking, and within each of these groups, rats were tested on days 1 and 5 of abstinence (i.e., 24 and 120 h following the last cocaine self-administration training session). Each test began with a 2 h extinction session after which the rats received their assigned drug injection and were returned to the self-administration chambers 15 min later for a 1 h drug-seeking test. For the first test on day 1 of abstinence, half of the rats received vehicle (1 mL/kg, s.c.) and half received CP 94,253 (5.6 mg/kg, s.c.). For the second test on day 5 of abstinence, the rats that had received vehicle prior to the first test received CP 94,253 (5.6 mg/kg, s.c.) and the rats that received CP 94,253 prior to the first test received vehicle. During the cue-elicited test sessions, rats were placed into the self-administration chamber connected to the tethers for a 1 h test session during which active lever responses on an FR1 schedule of reinforcement resulted in response-contingent presentations of the same stimulus complex that had been previously paired with cocaine infusions. Rats that failed to respond within the first 5 min were presented with a noncontingent cue. During the cocaine-primed test sessions, rats received a cocaine-priming injection (10 mg/kg, i.p.) immediately before they were placed into the operant conditioning chambers for a 1 h test session, during which responses produced no consequences. In order to control for possible injection stress effects on responding during tests for cue-elicited and cocaine-primed drug seeking, rats received a vehicle injection 15 min before their last two self-administration training sessions and before the extinction sessions on both test days.

Data Analyses

Cocaine infusions and inactive and active lever response rates during self-administration and extinction training were analyzed using independent-sample t tests. For experiment 1, cocaine dose and CP 94,253 pretreatment were used as repeated measures in a two-way ANOVA. For experiment 2, the total number of cocaine infusions were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA with cocaine dose (0.075 mg/kg or 0.75 mg/kg) and CP 94,253 pretreatment (vehicle or 5.6 mg/kg) doses as between-subjects factors. For experiment 3 examining the specificity of CP 94,253 effects during maintenance of cocaine self-administration, a mixed factor ANOVA was used with 5-HT1B receptor ligand type (i.e., SB 224289, CP 94,253, or SB 224289 + CP 94,253) as the between-subjects factor and dose (i.e., vehicle or drug) as the repeated measure. For experiment 3 examining specificity of CP 94,253 effects during protracted abstinence, a one-way ANOVA was used with 5-HT1B receptor ligand type (i.e., vehicle, SB 224289, CP 94,253, or SB 224289 + CP 94,253) as the between-subjects factor. For experiment 4, the total number of infusions, active lever responses, and the highest ratios achieved were analyzed using separate two-way ANOVAs with abstinence history (abstinence or extinction) and CP 94,253 pretreatment (vehicle or 5.6 mg/kg) as between-subjects factors. For experiment 5, planned comparisons examining lever response rates during cue-elicited and cocaine-primed drug seeking tests were conducted using independent-sample t tests at both time points. ANOVA significant interactions were followed by Newman-Keuls tests or by tests of simple effects using independent sample t tests. All statistics were conducted using SPSS, version 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY); α was set at 0.05 for all comparisons.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kenny J. Thiel, Lara A. Pockros, Jose Alba, Ben Engelhardt, and Suzanne M. Weber for their technical assistance.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- analysis of variance

ANOVA

- conditioned place preference

CPP

- fixed ratio

FR

- progressive ratio

PR

- serotonin

5-HT

- serotonin-1B

5-HT1B

Author Contributions

N.S.P., B.G.H., S.J.B., K.Y., R.M.B., N.A.P., T.D.G., and M.D.A. conducted the in vivo behavioral pharmacology. N.S.P., R.M.B., N.A.P. and J.L.N. interpreted the data. N.S.P. directed the behavioral experiments. N.S.P. and J.L.N. conceived of the project and wrote the paper. All authors edited and approved the final version of the manuscript.

A National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant to J.L.N. (DA11064) supported this research; National Institute on Drug Abuse Individual National Research Service Awards supported N.S.P. (DA025413), R.M.B. (DA035069), and N.A.P. (DA033805).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

References

- Morikawa H.; Manzoni O. J.; Crabbe J. C.; Williams J. T. (2000) Regulation of central synaptic transmission by 5-HT(1B) auto- and heteroreceptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 58, 1271–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sari Y. (2004) Serotonin1B receptors: from protein to physiological function and behavior. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 28, 565–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proudnikov D.; LaForge K. S.; Hofflich H.; Levenstien M.; Gordon D.; Barral S.; Ott J.; Kreek M. J. (2006) Association analysis of polymorphisms in serotonin 1B receptor (HTR1B) gene with heroin addiction: a comparison of molecular and statistically estimated haplotypes. Pharmacogenet. Genomics 16, 25–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H. F.; Chang Y. T.; Fann C. S.; Chang C. J.; Chen Y. H.; Hsu Y. P.; Yu W. Y.; Cheng A. T. (2002) Association study of novel human serotonin 5-HT(1B) polymorphisms with alcohol dependence in Taiwanese Han. Biol. Psychiatry 51, 896–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y. Y.; Oquendo M. A.; Friedman J. M.; Greenhill L. L.; Brodsky B.; Malone K. M.; Khait V.; Mann J. J. (2003) Substance abuse disorder and major depression are associated with the human 5-HT1B receptor gene (HTR1B) G861C polymorphism. Neuropsychopharmacology 28, 163–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. Y.; Lin W. W.; Huang S. Y.; Kuo P. H.; Wang C. L.; Wu P. L.; Chen S. L.; Wu J. Y.; Ko H. C.; Lu R. B. (2009) The relationship between serotonin receptor 1B polymorphisms A-161T and alcohol dependence. Alcohol.: Clin. Exp. Res. 33, 1589–1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J. X.; Hu J.; Ye X. M.; Xia Y.; Haile C. A.; Kosten T. R.; Zhang X. Y. (2011) Association between the 5-HTR1B gene polymorphisms and alcohol dependence in a Han Chinese population. Brain Res. 1376, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miszkiel J.; Filip M.; Przegalinski E. (2011) Role of serotonin (5-HT)1B receptors in psychostimulant addiction. Pharmacol. Rep. 63, 1310–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neisewander J. L.; Cheung T. H.; Pentkowski N. S. (2013) Dopamine D3 and 5-HT1B receptor dysregulation as a result of psychostimulant intake and forced abstinence: Implications for medications development. Neuropharmacology 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castanon N.; Scearce-Levie K.; Lucas J. J.; Rocha B.; Hen R. (2000) Modulation of the effects of cocaine by 5-HT1B receptors: a comparison of knockouts and antagonists. Pharmacol., Biochem. Behav. 67, 559–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha B. A.; Scearce-Levie K.; Lucas J. J.; Hiroi N.; Castanon N.; Crabbe J. C.; Nestler E. J.; Hen R. (1998) Increased vulnerability to cocaine in mice lacking the serotonin-1B receptor. Nature 393, 175–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons L. H.; Weiss F.; Koob G. F. (1998) Serotonin1B receptor stimulation enhances cocaine reinforcement. J. Neurosci. 18, 10078–10089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przegalinski E.; Golda A.; Frankowska M.; Zaniewska M.; Filip M. (2007) Effects of serotonin 5-HT1B receptor ligands on the cocaine- and food-maintained self-administration in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 559, 165–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pentkowski N. S.; Acosta J. I.; Browning J. R.; Hamilton E. C.; Neisewander J. L. (2009) Stimulation of 5-HT(1B) receptors enhances cocaine reinforcement yet reduces cocaine-seeking behavior. Addict. Biol. 14, 419–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belzung C.; Scearce-Levie K.; Barreau S.; Hen R. (2000) Absence of cocaine-induced place conditioning in serotonin 1B receptor knock-out mice. Pharmacol., Biochem. Behav. 66, 221–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervo L.; Rozio M.; Ekalle-Soppo C. B.; Carnovali F.; Santangelo E.; Samanin R. (2002) Stimulation of serotonin1B receptors induces conditioned place aversion and facilitates cocaine place conditioning in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berlin, Ger.) 163, 142–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison A. A.; Parsons L. H.; Koob G. F.; Markou A. (1999) RU 24969, a 5-HT1A/1B agonist, elevates brain stimulation reward thresholds: an effect reversed by GR 127935, a 5-HT1B/1D antagonist. Psychopharmacology (Berlin, Ger.) 141, 242–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acosta J. I.; Boynton F. A.; Kirschner K. F.; Neisewander J. L. (2005) Stimulation of 5-HT1B receptors decreases cocaine- and sucrose-seeking behavior. Pharmacol., Biochem. Behav. 80, 297–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przegalinski E.; Golda A.; Filip M. (2008) Effects of serotonin (5-HT)(1B) receptor ligands on cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Pharmacol. Rep. 60, 798–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pentkowski N. S.; Cheung T. H.; Toy W. A.; Adams M. D.; Neumaier J. F.; Neisewander J. L. (2012) Protracted Withdrawal from Cocaine Self-Administration Flips the Switch on 5-HT(1B) Receptor Modulation of Cocaine Abuse-Related Behaviors. Biol. Psychiatry 72, 396–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumaier J. F.; McDevitt R. A.; Polis I. Y.; Parsons L. H. (2009) Acquisition of and withdrawal from cocaine self-administration regulates 5-HT mRNA expression in rat striatum. J. Neurochem. 111, 217–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miszkiel J.; Adamczyk P.; Filip M.; Przegalinski E. (2012) The effect of serotonin 5HT(1B) receptor ligands on amphetamine self-administration in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 677, 111–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koe B. K.; Nielsen J. A.; Macor J. E.; Heym J. (1992) Biochemical and Behavioral-Studies of the 5-Ht(1b) Receptor Agonist, Cp-94,253. Drug Dev. Res. 26, 241–250. [Google Scholar]

- Selkirk J. V.; Scott C.; Ho M.; Burton M. J.; Watson J.; Gaster L. M.; Collin L.; Jones B. J.; Middlemiss D. N.; Price G. W. (1998) SB-224289--a novel selective (human) 5-HT1B receptor antagonist with negative intrinsic activity. Br. J. Pharmacol. 125, 202–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Dell L. E.; Manzardo A. M.; Polis I.; Stouffer D. G.; Parsons L. H. (2006) Biphasic alterations in serotonin-1B (5-HT1B) receptor function during abstinence from extended cocaine self-administration. J. Neurochem. 99, 1363–1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace B. C. (1992) Treating crack cocaine dependence: the critical role of relapse prevention. J. Psychoact. Drugs 24, 213–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien C. P. (2005) Anticraving medications for relapse prevention: a possible new class of psychoactive medications. Am. J. Psychiatry 162, 1423–1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt W. A.; Barnett L. W.; Branch L. G. (1971) Relapse rates in addiction programs. J. Clin. Psychol. 27, 455–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrman R. N.; Robbins S. J.; Childress A. R.; O’Brien C. P. (1992) Conditioned responses to cocaine-related stimuli in cocaine abuse patients. Psychopharmacology (Berlin, Ger.) 107, 523–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis W. M.; Smith S. G. (1976) Role of conditioned reinforcers in the initiation, maintenance and extinction of drug-seeking behavior. Pavlovian J. Biol. Sci. 11, 222–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H.; Stewart J. (1981) Reinstatement of cocaine-reinforced responding in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berlin, Ger.) 75, 134–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien C. P.; Childress A. R.; McLellan A. T.; Ehrman R. (1992) Classical conditioning in drug-dependent humans. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 654, 400–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawin F. H.; Kleber H. D. (1986) Abstinence symptomatology and psychiatric diagnosis in cocaine abusers. Clinical observations. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 43, 107–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran-Nguyen L. T.; Fuchs R. A.; Coffey G. P.; Baker D. A.; O’Dell L. E.; Neisewander J. L. (1998) Time-dependent changes in cocaine-seeking behavior and extracellular dopamine levels in the amygdala during cocaine withdrawal. Neuropsychopharmacology 19, 48–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neisewander J. L.; Baker D. A.; Fuchs R. A.; Tran-Nguyen L. T.; Palmer A.; Marshall J. F. (2000) Fos protein expression and cocaine-seeking behavior in rats after exposure to a cocaine self-administration environment. J. Neurosci. 20, 798–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm J. W.; Hope B. T.; Wise R. A.; Shaham Y. (2001) Neuroadaptation. Incubation of cocaine craving after withdrawal. Nature 412, 141–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preti A. (2007) New developments in the pharmacotherapy of cocaine abuse. Addict. Biol. 12, 133–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowan-Szal G. A.; Chatham L. R.; Simpson D. D. (2000) Importance of identifying cocaine and alcohol dependent methadone clients. Am. J. Addict. 9, 38–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leri F.; Bruneau J.; Stewart J. (2003) Understanding polydrug use: review of heroin and cocaine co-use. Addiction 98, 7–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinzleve M.; Haasen C.; Zurhold H.; Matali J. L.; Bruguera E.; Gerevich J.; Bacskai E.; Ryder N.; Butler S.; Manning V.; Gossop M.; Pezous A. M.; Verster A.; Camposeragna A.; Andersson P.; Olsson B.; Primorac A.; Fischer G.; Guttinger F.; Rehm J.; Krausz M. (2004) Cocaine use in Europe - a multi-centre study: patterns of use in different groups. Eur. Addict. Res. 10, 147–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller N. S.; Summers G. L.; Gold M. S. (1993) Cocaine dependence: alcohol and other drug dependence and withdrawal characteristics. J. Addict. Dis. 12, 25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomkins D. M.; O’Neill M. F. (2000) Effect of 5-HT(1B) receptor ligands on self-administration of ethanol in an operant procedure in rats. Pharmacol., Biochem. Behav. 66, 129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson A. W.; Costall B.; Neill J. C. (2000) Manipulation of operant responding for an ethanol-paired conditioned stimulus in the rat by pharmacological alteration of the serotonergic system. J. Psychopharmacol. 14, 340–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pockros L. A.; Pentkowski N. S.; Swinford S. E.; Neisewander J. L. (2011) Blockade of 5-HT2A receptors in the medial prefrontal cortex attenuates reinstatement of cue-elicited cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berlin, Ger.) 213, 307–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoplight B. J.; Vincow E. S.; Neumaier J. F. (2005) The effects of SB 224289 on anxiety and cocaine-related behaviors in a novel object task. Physiol. Behav. 84, 707–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pentkowski N. S.; Duke F. D.; Weber S. M.; Pockros L. A.; Teer A. P.; Hamilton E. C.; Thiel K. J.; Neisewander J. L. (2010) Stimulation of medial prefrontal cortex serotonin 2C (5-HT(2C)) receptors attenuates cocaine-seeking behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology 35, 2037–2048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll M. E.; France C. P.; Meisch R. A. (1981) Intravenous self-administration of etonitazene, cocaine and phencyclidine in rats during food deprivation and satiation. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 217, 241–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson N. R.; Roberts D. C. (1996) Progressive ratio schedules in drug self-administration studies in rats: a method to evaluate reinforcing efficacy. J. Neurosci. Methods 66, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covington H. E. 3rd; Miczek K. A. (2005) Intense cocaine self-administration after episodic social defeat stress, but not after aggressive behavior: dissociation from corticosterone activation. Psychopharmacology (Berlin, Ger.) 183, 331–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covington H. E. 3rd; Tropea T. F.; Rajadhyaksha A. M.; Kosofsky B. E.; Miczek K. A. (2008) NMDA receptors in the rat VTA: a critical site for social stress to intensify cocaine taking. Psychopharmacology (Berlin, Ger.) 197, 203–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]