Abstract

Objective

Delirium is associated with poor outcomes following acute hospitalization. The Geriatric Monitoring Unit (GMU) is a specialized five-bedded unit for acute delirium care. It is modeled after the Delirium Room program, with adoption of core interventions from the Hospital Elder Life Program and use of evening light therapy to consolidate circadian rhythms and improve sleep in older inpatients. This study examined whether the GMU program improved outcomes in delirious patients.

Method

A total of 320 patients, including 47 pre-GMU, 234 GMU, and 39 concurrent control subjects, were studied. Clinical characteristics, cognitive status, functional status (Modified Barthel Index [MBI]), and chemical restraint-use data were obtained. We also looked at in-hospital complications of falls, pressure ulcers, nosocomial infection rate, and discharge destination. Secondary outcomes of family satisfaction (for the GMU subjects) were collected.

Results

There were no significant demographic differences between the three groups. Pre-GMU subjects had longer duration of delirium and length of stay. MBI improvement was most evident in the GMU compared with pre-GMU and control subjects (19.2±18.3, 7.5±11.2, 15.1±18.0, respectively) (P<0.05). The GMU subjects had a zero restraint rate, and pre-GMU subjects had higher antipsychotic dosages. This translated to lower pressure ulcer and nosocomial infection rate in the GMU (4.1% and 10.7%, respectively) and control (1.3% and 7.7%, respectively) subjects compared with the pre-GMU (9.1% and 23.4%, respectively) subjects (P<0.05). No differences were observed in mortality or discharge destination among the three groups. Caregivers of GMU subjects felt the multicomponent intervention to be useful, with scheduled activities voted the most beneficial in patient’s recovery from the delirium episode.

Conclusion

This study shows the benefits of a specialized delirium management unit for older persons. The GMU model is thus a relevant system of care for rapidly “graying” nations with high rates of frail elderly hospital admissions, which can be easily transposed across acute care settings.

Keywords: delirium, function, elderly

Introduction

Delirium is a common and serious condition in older hospitalized patients. The prevalence in hospitalized elderly patients is as high as 50%, being present in 11%–24% of older patients at admission, with another 5%–35% developing delirium during admission.1,2 It is an indicator of severe underlying illness, necessitating early diagnosis and prompt treatment. Delirium is associated with increased need for nursing surveillance, greater hospital costs, and high mortality rates of 25%–33% during hospitalization and 35%–40% at 1 year.3–8

The Geriatric Monitoring Unit (GMU) was developed at the Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore in October 2010, using an evidence-based approach incorporating specific interventions established to be beneficial for delirium care. The details of GMU have been published previously.9 In brief, the GMU incorporated specific measures established in other programs: 1) the Delirium Room model, which provides comprehensive medical care with multidisciplinary team meetings and employs behavioral and appropriate nonpharmacological strategies as first-line management in delirious patients;10 2) the concept of structured core interventions developed in the Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP);11–18 and 3) bright light therapy, to establish a healthy sleep–wake cycle, with appropriate timing to effectively shift an altered circadian sleep–wake cycle to the desired phase.

While there have been many studies looking at delirium prevention in hospitalized older persons, literature examining the impact of combination measures to improve care of hospitalized older persons with acute delirium, and more recently, in the intensive care setting, have been sparse (Table 1).10–13,19–24 The mixed results highlight the heterogeneity of interventions (which commonly includes comprehensive medical input with intensive nursing care and education). The GMU represents a unique model of acute delirium care incorporating evidence-based, widely-accepted management strategies in delirium prevention and/or management, in an elder-friendly design environment, together with a group of skilled nursing professionals trained in acute delirium care.

Table 1.

Summary of studies on delirium management in acute hospitals

| Study | Subjects, n | Interventions | Outcomes | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cole et al19 | 88 | • Geriatric consultation within 24 hours • Daily nursing visits • Nursing intervention protocol |

• SPMSQ (memory, orientation, concentration) • CAM • CGBRS (behavior and ADLs) |

• Improvement in SPMSQ scores at 2 weeks but no difference at 8 weeks • No difference in restraint use, LOS, discharge setting, or survival |

| Cole et al20 | 227 | • Geriatrician consult within 24 hours • Daily nurse visits • Nursing intervention protocol |

• MMSE • Delirium index • Barthel index • LOS • Survival within 8 weeks • Charlson’s |

• No difference in time to improvement • No difference in delirium index, Barthel, LOS, discharge setting, or survival |

| Flaherty et al10 | 196, 69 with delirium | • 24-hour intensive nursing care • Physical restraints-free policy • Comprehensive geriatric care |

• Not applicable (descriptive study) | • No physical restraints used during patient hospital stay • Lower use of pharmacological restraints • LOS equal to expected LOS |

| Lundstrom et al11 | 400, 125 with delirium | • 2-day education course for staff, on Geriatrics • Education for caregiver–patient interaction • Work reorganization (focus on individualized care) • Monthly staff guidance |

• OBS scale • MMSE • Katz ADL • DSM IV for delirium |

• Fewer patients remained delirious on day 7 • LOS lower with intervention • Fewer deaths in subjects in intervention ward |

| Pitkala et al12,13 | 174 | • Comprehensive geriatric assessment • Administering atypical antipsychotics instead of conventional neuroleptics • Orientation • Physiotherapy • Nutritional supplementation • Hip protectors • Cholinesterase inhibitors • Discharge planning |

• Discharge destination and mortality • MMSE • Barthel • MNA • Geriatric depression scale • MDAS • Costs and HRQoL |

• No significant difference in primary outcome (institutionalization and mortality) • Intensity and symptoms of delirium were alleviated faster in treatment group • Improvement in cognition at 6 months • No difference in change of function |

| Michaud et al21 | 200 | • Pharmacologic treatment within 24 hours of first positive screen for delirium, while intubated in mixed ICU | • Number of days spent in physical restraint • Time to extubation after delirium onset • Secondary outcomes of hospital and ICU length of stay and survival to discharge |

• Shorter median time in restraints compared with patients not pharmacologically treated • Shorter median time to extubation • Shorter ICU and hospital length of stay |

| Carrothers et al22 | 4 participating SF Bay Area ICUs | • Implementation of the awakening, breathing, coordination, delirium, and early mobility (ABCDE) bundle in 4 participating SF Bay Area ICUs • ABCDE bundle consisted of spontaneous awakening trials, spontaneous breathing trials, coordination of awakening and breathing trials, choice of sedation, delirium screening and treatment, and early progressive mobilization |

• Evaluating factors that facilitated or hindered implementation of ABCDE bundle • Process data related to bundle compliance and outcome data (average ICU length of stay and average days on mechanical ventilation) were collected |

• Factors related to structural characteristics of ICU, organizational-wide patient safety culture, ICU culture of quality improvement, implementation planning, training/support, and prompts/documentation facilitated bundle implementation. • Excessive turnover, staff morale issues, lack of respect among disciplines, knowledge deficits, and excessive use of registry staff hinder implementation |

| Goldberg et al23 | 700 | • Participants randomized in to a specialist medical unit and mental health unit designed to deliver best practice care for people with delirium or dementia versus standard care | • Number of days spent at home in the 90 days after randomization (composite outcome taking into account death, time spent in hospital, readmissions, inpatient rehabilitation or intermediate care, or new placement in care home). • Quality of life, behavioral and psychological symptoms, physical disability, cognitive impairment, caregiver strain, and caregiver psychological wellbeing • Caregiver satisfaction |

• Improved the patient experience and caregiver satisfaction • No convincing benefits in health status or service use |

| Mudge et al24 | 206 | • Controlled trial in older adults with or at risk of delirium in a medical ward (with implementation of delirium guidelines) compared with control medical ward | • Incidence and duration of delirium • Secondary outcomes of length of stay, mortality, falls, and discharge destination in delirious subgroup |

• Lower incidence of new delirium • Fewer cases of persistent delirium and trends of reduced inpatient mortality and falls • Noted longer medical ward stay |

Abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living; CAM, Confusion Assessment Method; CGBRS, Crichton Geriatric Behavioural Rating Scale; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; MDAS, Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; MNA, Mini Nutritional Assessment; OBS, Organic Brain Syndrome Scale; SF, San Francisco; SPMSQ, Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire.

We published initial data on functional improvement in delirious patients admitted to the GMU, independent of their underlying cognitive status,25 supporting the role of the early mobilization and rehabilitation of older persons admitted for acute delirium regardless of their premorbid cognitive functioning. The benefits of bright light therapy in a multicomponent intervention program on sleep, cognitive, and functional outcomes in GMU patients have also been demonstrated.26 This was a follow-up study that evaluated the outcomes of the GMU program on older persons hospitalized for acute delirium compared with those for the pre-GMU implementation period and concurrent controls.

Methods

Subjects

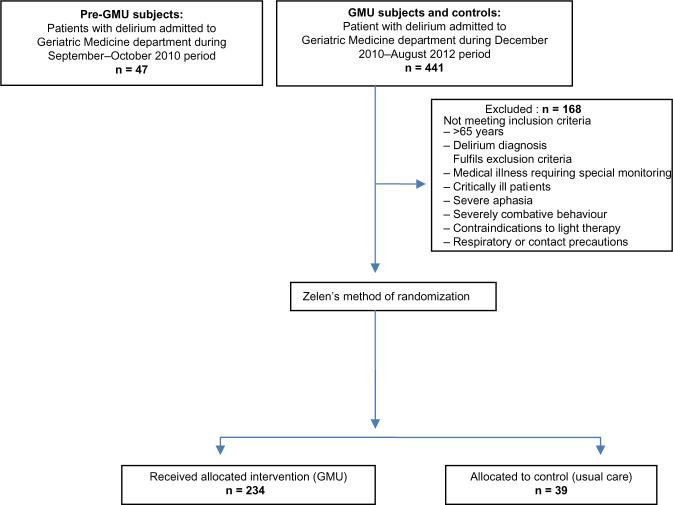

We recruited 320 delirious patients admitted to the Department of Geriatric Medicine, Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore between September 1, 2010 to August 24, 2012. Figure 1 shows the flowchart of the subjects included in the study. We excluded 168 subjects who did not meet inclusion or exclusion criteria for this study.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of older persons with delirium included in the study.

Abbreviation: GMU, Geriatric Monitoring Unit.

Inclusion/exclusion

The admission criteria for admission to the GMU included patients above 65 years old who were admitted to the Geriatric Medicine department and assessed to have delirium (either on admission or incident delirium during the hospital stay), established in accordance with the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM).27 Patients were excluded if: they had medical illnesses that required special monitoring (eg, telemetry for arrhythmias or acute myocardial infarction); they were assessed to be dangerously ill, in coma, or had terminal illness; uncommunicative or with severe aphasia; showing severely combative behavior with high risk of harm; and contraindications to bright light therapy (manic disorders, severe eye disorders, photosensitive skin disorders, or use of photosensitizing medications). Patients with respiratory or contact precautions, and those with verbal refusal of GMU admission by family/patient/physician-in-charge were also excluded. There were no sex differences between the GMU or GMU-refusal groups. Patients who were prematurely transferred out of the GMU (for reasons such as instability of medical conditions requiring intensive monitoring or requirement of contact precautions) were excluded from subsequent analysis.

This study was registered under Current Controlled Trials ISRCTN52323811. Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board. Consent was obtained from the caregiver or legally acceptable representative.

Procedure

The GMU consisted of a five-bed unit with a specific elder-friendly room design and lower staff–patient ratios. In addition, core interventions adopted from HELP program (standardized protocols for managing cognitive impairment, sleep deprivation, immobility, visual impairment, hearing impairment, and dehydration) were systematically administered. Bright light therapy (2,000–3,000 lux) was administered via lights installed in the ceiling and turned on from 6–10 pm daily. Sleep hygiene principles were also practiced during the GMU stay. All interventions were adhered to, via a semistructured protocol, by trained geriatric nurses in GMU, with full (100%) compliance achieved.

For the pre-GMU and concurrent controls group, good geriatric care was provided in the geriatric wards. The rationale for use of both a pre-GMU group and a concurrent control was to compare pre- and post-GMU implementation as well as to study the concurrent control with GMU group to ensure that time-related effects and global changes in nursing and hospital practices were accounted for. Zelen’s method of randomization was used for the GMU and concurrent controls group and was previously highlighted in the original study paper.9

We collected data on patient demographics (age, sex, race, length of hospital stay [LOS], duration of delirium [days]), medical comorbidities and severity of illness (using modified Charlson’s comorbidity index28 and modified Severity of Illness Index),29 and precipitating causes of delirium. Delirium subtypes (hyperactive, hypoactive, and mixed delirium subtypes) were determined by the consultant geriatrician, upon admission to GMU, based on clinical assessment of the patient’s mental state and behavior. Cognitive status was assessed using the locally validated Chinese Mini-Mental State Examination (CMMSE)30 (with a total score of 28), and functional status was scored using the Modified Barthel Index (MBI) (total score of 100),31 both administered by a trained assessor during the initial and predischarge phase of the subject’s admission. The rate and frequency of chemical restraint use was reviewed, and data on the usage of antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, anti-depressants and anticonvulsants collected. Of note, as the GMU had adopted a mechanical restraint-free policy, none of the patients in the GMU had been subjected to physical restraint since the start of the GMU in November 2010. To adjust for the different antipsychotics prescribed, we used chlorpromazine equivalence32 to assess the total antipsychotic usage during the admission.

Cognitive assessment

All patients underwent a detailed cognitive evaluation by the consultant geriatrician (specializing in cognitive and memory disorders) upon admission to the GMU. A family member or other designated caregiver was routinely interviewed to establish the patient’s baseline cognitive functioning prior to the current admission. The medical records of all the patients were reviewed to ascertain whether a diagnosis of dementia had been previously established. In patients yet to be diagnosed, a diagnosis of dementia was made in the current admission if the corroborative history suggested the presence of cognitive symptoms consistent with Diagnostic Statistical Manual, fourth edition (DSM-IV) criteria for dementia,33 in accordance with the standardized process for cognitive evaluation.34

A patient was deemed to have recovered from delirium if the CAM criteria were no longer met, with diagnosis of recovery being supported by improvement in cognitive and or delirium severity scores (based on the Delirium Rating Scale-R98 [DRS-R98]35 and CAM severity scores), as well as inputs from the multidisciplinary team.

Outcomes

We collected data on the rate of falls and injuries sustained while hospitalized, pressure ulcer rate, urinary catheter usage, nosocomial infection, LOS, inpatient mortality, and discharge destination (home or incident institutionalization).

We also obtained information on caregiver satisfaction, for subjects admitted to the GMU, on: level of distress during the subject’s admission; usefulness of the GMU environment to patient recovery; the utility of multicomponent intervention to patient recovery and, in their opinion, the most useful component; and their satisfaction with care and staff competence provided in the GMU.

For GMU subjects whose caregivers consented to follow-up review, we obtained information, via telephone interview, on their functional status, morbidity, and mortality status at 6-months and 12-months follow up.

Statistical analysis

We compared the demographics, clinical characteristics, delirium subtypes, cognitive assessment scores, functional status, and use of pharmacological agents among the pre-GMU, GMU, and concurrent control subjects, using analysis of variance (ANOVA), with Bonferroni correction and chi-square tests for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Short-term outcome results were also compared between the three groups. We performed Spearman correlation between delirium duration and MBI change at 6 months and 12 months, as well as correlation between delirium severity at onset and MBI change at 6 months and 12 months. Subgroup analyses on caregiver satisfaction in GMU care were also performed.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (Version 16.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical significance was taken to be P<0.05.

Results

We included 47 subjects recruited during the pre-GMU implementation period, 234 subjects who were admitted to GMU, and 39 corresponding controls (delirious older persons managed in the general geriatric ward). Details are shown in Figure 1.

There were no significant age, sex, or ethnicity differences between the three groups, although pre-GMU subjects had longer duration of delirium and LOS compared with the GMU and control subjects (15.1±2.3, 6.3±4.7, and 4.4±3.0, respectively, for delirium days; 21.9±13.8, 14.9±9.0, and 12.5±9.1, respectively, for LOS) (P<0.05) (Table 2). When adjusted for Charlson’s comorbidity score, we found the duration of delirium to be 15.1±0.23, 6.3±0.17, and 4.4±0.13 days and LOS to be 21.9±0.8, 15.0±0.55, and 12.5±0.4 for the pre-GMU, GMU, and control subjects, respectively.

Table 2.

Demographics, clinical characteristics, cognitive and functional status, and outcomes in the pre-GMU, GMU and concurrent control subjects (total n=320)

| Pre-GMU subjects (n=47) |

GMU subjects (n=234) |

Controls (n=39) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics (mean ± SD unless stated otherwise) | |||

| Age, years | 84.3±9.2 | 84.1±7.4 | 84.5±8.2 |

| Race (% Chinese ethnicity) | 89.4 | 87.6 | 76.9 |

| Sex (% male) | 19.1 | 43.6 | 35.9* |

| No of days of delirium | 15.1±2.3 | 6.3±4.7 | 4.4±3.0*,# |

| Length of stay | 21.9±13.8 | 14.9±9.0 | 12.5±9.1*,# |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Charlson comorbidity score | 3.6±2.2 | 2.2±1.6 | 2.3±1.3*,# |

| Severity of Illness score | |||

| – Level 1 (%) | 0 | 2.6 | 0 |

| – Level 2 (%) | 76.6 | 89.3 | 87.2* |

| – Level 3 (%) | 23.4 | 8.1 | 12.8 |

| Presence of dementia (%) | Data not available | 73.1 | 53.8* |

| Type of delirium | |||

| – Hyperactive (%) | Data not available | 51.7 | 51.3* |

| – Hypoactive (%) | Data not available | 19.7 | 35.9 |

| – Mixed (%) | Data not available | 28.6 | 12.8 |

| Cognitive and functional status | |||

| CMMSE (on admission) | Data not available | 5.7±5.3 | 4.1±5.3 |

| CMMSE (on discharge) | Data not available | 9.3±6.6 | 8.4±7.6 |

| MBI (on admission) | 39.5±33.6 | 28.8±24.1 | 31.6±28.8*,+ |

| MBI (on discharge) | 45.7±32.9 | 48.0±25.7 | 46.7±28.4 |

| Improvement in MBI | 7.5±11.2 | 19.2±18.3 | 15.1±18.0*,+ |

| Physical and chemical restraint use | |||

| Physical restraint use (%) | 44.7 | 0 | 23.1* |

| Chemical restraint use (%) | 72.3 | 40.3 | 33.3 |

| Total CPZ equivalent | 4.1±8.4 | 0.4±1.2 | 0.4±1.5*,# |

| Benzodiazepine use (%) | 23.4 | 25.6 | 15.4 |

| Antidepressant use (%) | 63.8 | 62.8 | 48.7 |

| Anticonvulsant use (%) | 21.3 | 21.4 | 10.3 |

| Short-term outcomes | |||

| Falls in hospital (%) | 2.1 | 1.3 | 2.6 |

| Urinary catheter use (%) | 31.9 | 29.1 | 25.6 |

| Pressure ulcer rate (%) | 9.1 | 4.1 | 1.3* |

| Nosocomial infection (%) | 23.4 | 10.7 | 7.7* |

| Discharge destination (%) | |||

| – Home | Data not available | 72.3 | 66.7 |

| – Further rehabilitation | Data not available | 9.1 | 12.8 |

| – Nursing home | Data not available | 10.8 | 20.5 |

| – Back to nursing home | Data not available | 6.1 | 0 |

| – Death | Data not available | 1.7 | 0 |

Notes:

P<0.05

between-group differences (pre-GMU vs GMU and pre-GMU vs controls)

between group differences (pre GMU and GMU).

Abbreviations: CMMSE, Chinese Mini-Mental State Examination; CPZ, chlorpromazine; GMU, Geriatric Monitoring Unit; MBI, Modified Barthel Index; SD, standard deviation.

The pre-GMU had significantly more comorbidities and severity of illness compared with the GMU and control subjects. Between GMU and control subjects, there was a higher prevalence of dementia (73.1% versus 53.8%, respectively) (P<0.05), with a higher rate of mixed delirium in GMU subjects and hypoactive delirium in control subjects (Table 2). Improvement in functional status (demonstrated by MBI improvement) was most evident in the GMU subjects compared with the pre-GMU and control subjects (19.2±18.3, 7.5±11.2, 15.1±18.0, respectively) (P<0.05).

Significant differences were noted in the physical restraint rate, where the GMU achieved a 0% restraint rate compared with a pre-GMU rate of 44.7% and the control subjects’ rate of 23.1% (P<0.05). Although there was no difference in overall chemical restraint use, the pre-GMU subjects had higher chlorpromazine-equivalent antipsychotic dosage compared with GMU and control subjects respectively (4.1±8.4, 0.4±1.1, and 0.4±1.5) (P<0.05). There were no significant differences in benzodiazepine, antidepressant, or anticonvulsant usage between the three groups.

Outcomes

There were lower pressure ulcer and nosocomial infection rates in GMU and control subjects compared with pre-GMU subjects (Table 2). No significant difference was observed between the available data for GMU and control subjects in mortality or discharge destination.

Caregiver satisfaction with GMU delirium care

Of the 234 GMU subjects, 160 of their caregivers consented to being interviewed with regard to family satisfaction (Table 3). The majority were distressed that their loved ones were admitted for acute delirium, and the majority (86.6%) felt that the GMU environment was very useful (54.3%) or moderately useful (32.3%) in the patient’s recovery from delirium. A total of 50.6% felt that the multicomponent intervention was very useful and 32.9% found it to be moderately useful in the patient’s recovery from delirium. They prioritized, in descending order, therapeutic activities, reality orientation, thrice-daily mobilization, reminiscence therapy, light therapy, sleep protocol, nutritional intervention, and addressing sensory impairment to be most useful to their loved one’s recovery. The majority were satisfied or very satisfied with care (95.2%), with 53.6% being satisfied with staff competence in care of their loved ones in GMU.

Table 3.

Satisfaction of the caregivers of older persons with delirium admitted to GMU (results in percentage)

| Caregivers of GMU patients (n=160) | |

|---|---|

| How distressed were they during their loved ones admission? | |

| Very distressed | 29.9 |

| Moderately distressed | 42.1 |

| Neutral | 12.2 |

| A little distressed | 11.6 |

| Not distressed at all | 4.2 |

| How useful is the GMU environment in patient’s recovery? | |

| Very useful | 54.3 |

| Moderately useful | 32.3 |

| Neutral | 9.1 |

| A little useful | 3.6 |

| Not useful at all | 0.6 |

| Multicomponent interventions useful to patient recovery? | |

| Very useful | 50.6 |

| Moderately useful | 32.9 |

| Neutral | 13.4 |

| A little useful | 1.8 |

| Not useful at all | 0.6 |

| When asked to grade which of the multicomponent interventions helped most (most to least useful) | – Activity (most useful) – Reality orientation – Thrice-daily mobilization – Reminiscence therapy – Light therapy – Sleep protocols – Nutritional interventions – Addressing sensory impairments (least useful) |

| Satisfaction with overall care? | |

| Very satisfied | 54.3 |

| Satisfied | 40.9 |

| Neutral | 4.9 |

| Dissatisfied | 0 |

| Very dissatisfied | 0 |

| Satisfaction with knowledge and skills of staff in GMU? | |

| Very satisfied | 0.6 |

| Satisfied | 53.0 |

| Neutral | 40.2 |

| Dissatisfied | 5.5 |

| Very dissatisfied | 0.6 |

Abbreviation: GMU, Geriatric Monitoring Unit.

The 6-month and 12-month longitudinal follow-up

In all, 168 out of 234 GMU subjects’ caregivers consented to longitudinal follow up, and two subjects dropped out during the interim 6-month follow up. Of the 166 remaining subjects at the 6-month follow-up visit, 20 subjects (12.0%) passed away, and 49.7% had new illnesses or hospitalization. Functionally, there was only a 2.6±25.9 deterioration in MBI score reported at 6-months (discharge MBI 52.9±25.0 versus 50.3±32.0 MBI at 6 months) (P=0.22). At the 12-month follow-up, another 14 subjects had passed away (with the total 12-month mortality at 20.5%), and 43.2% had new illnesses or hospitalization at the 12-month follow-up. Functionally, there was still only a modest deterioration of MBI score of 3.7±27.9 (discharge MBI 54.2±23.9 versus 50.4±32.0) (P=0.11).

We correlated delirium duration with MBI change at 6 months (Spearman’s correlation r=−0.19, P=0.02) and at 12 months (r=−0.19, P=0.03); and delirium severity (DRS-R98 severity score) at onset with MBI change at 6 months (r=−0.18, P=0.03) and at 12 months (r=−0.11, P=0.193). The modest correlation would suggest that the MBI improvement/stability may be affected by other factors (other than intrinsic delirium parameters of delirium duration and severity) – possibly the GMU intervention program.

Discussion

Delirium is a geriatric syndrome with varying etiologies and causal pathways and hence, varying presentations and treatment strategies. The American Delirium Society has suggested a paradigm shift towards patient-focused models of care in order to more effectively apply current knowledge of delirium risk and presentation (by early delirium detection) to modify the health care delivery environment and decrease the incidence of delirium in hospitalized older adults.36 Additionally, secondary delirium prevention, with the aim of reducing the impact of delirium,37 is of paramount importance, given the high cost of delirium and its sequelae (estimated between $38–$152 billion annually).38

We have developed a model of acute delirium care (GMU) using evidenced-based nonpharmacological approaches incorporating 1) an elder-friendly environment; 2) interventions addressing sensory impairments, dehydration, reality orientation, and early mobilization (to prevent worsening delirium and the complications of immobilization);14,39 3) management of sleep issues with light therapy; and 4) care delivery using staff trained in the person-centered care approach. This would allow judicious use of pharmacological management in the subgroup of patients whose behavior continues to pose a challenge to care despite adequate nonpharmacological measures.40 GMU patients had shorter delirium duration and LOS compared with the pre-GMU implementation group. Importantly, none of the patients were physically restrained despite 80.3% of them having hyperactive and mixed delirium, with no evidence of a higher rate of falls and a significantly lower antipsychotic dose usage. Our study findings clearly debunk the age-old notion that confused patients should be restrained to prevent falls and complications. This multicomponent delirium management model also translated to better short-term outcomes in terms of pressure ulcer rate and functional improvement. Caregivers were also satisfied with the care rendered, whereby the majority concurred with the efficacy of the multicomponent interventions and purpose-built GMU environment. The activity program was voted to have contributed the most to their loved one’s delirium recovery. Of the 71.8% (n=168) of GMU patients for whom caregivers had consented to longer-term follow up, we found an overall mortality rate of 20.5% at 12-months. This is lower than the rates reported in previously published studies on short-term and 1-year delirium mortality.41,42 There was sustained functional maintenance in those GMU patients who survived at the end of 6 months and 12 months (MBI decline of only 2.6–3.7 points at 6 and 12 months, respectively), despite these being frail patients with a mean MBI score of 52.9–54.2.

The short- and intermediate-term functional benefits observed were likely due to 1) the comprehensive, multicomponent delirium management intervention, with the contributions of both nonpharmacological interventions and judicious use of pharmacological agents; 2) prevention of complications as a result of early mobilization, absence of physical restraints, and decreased pharmacologic interventions; 3) improved sleep patterns, with a sleep protocol and evening light therapy;26 and 4) an unbiased approach to rehabilitating persons with delirium regardless of the premorbid dementia status.25 This broad approach is even more translatable to clinical practice in a busy acute care hospital than to the more narrow, carefully selected clinical research population.

There were a few limitations to our study. Firstly, there were significantly fewer patients in the concurrent control study group. This was due to the hospital-wide implementation of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) screening during the interim few months before the start of our research study. This resulted in fewer patients being eligible for the GMU or concurrent control group, and we would be careful with interpretation of the decreased nosocomial infection rate result. Secondly, we did not perform regression analyses to adjust for observed differences between the GMU and control groups because of the small number of subjects in the latter. Consequently, the higher proportion of dementia in the GMU group is likely to result in bias towards worse outcomes compared with the control group. Thirdly, given the small number of subjects randomized to the control group, the possibility of unobserved differences exists, in addition to those observed; however if present, the direction of any bias is difficult to predict. Nevertheless, our focus was on the shorter- and longer-term benefits of the GMU, which is the main thrust of the paper, with definite improvements seen compared with the pre-GMU implementation period.

The GMU represents a change at the system level, which extends beyond the bedside to the boardroom.17 Since the end of the study period in August 2012, the unit has been converted to a full clinical service endorsed by the hospital senior management. The GMU continues to show sustained benefit in terms of shorter delirium duration and hospital cost savings resulting from the lower LOS for older persons with delirium. This innovative acute delirium care model is thus appealing as a system of care for rapidly “graying” nations with high rates of frail elderly hospital admissions, which can be easily transposed across various acute care settings.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Wong Yoke Moi, RN; Joycelyn Zhao, RN; Han Huey Charn, RN; Jasmine Kang, APN; the GMU nurses, and the GMU multidisciplinary team.

This study was funded by FY2010 Ministry of Health Quality Improvement Funding (MOH HQIF) “Optimising Acute Delirium Care in Tan Tock Seng Hospital” (HQIF 2010/17), Singapore. CMS is supported by the National Healthcare Group (NHG), Singapore, and Clinician Scientist Career Scheme (CSCS) 2012/12002, and LT is supported by the NHG CSCS 2013/13001.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Agnostini JV, Inouye Sk. Delirium. In: Hazzard WR, Blass JP, Halter JB, Ouslander JG, Tinetti ME, editors. Principles in Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2003. pp. 1503–1515. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inouye SK. Delirium in hospitalized older patients. Clin Geriatr Med. 1998;14(4):745–764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cole MG, Primeau FJ. Prognosis of delirium in elderly hospital patients. CMAJ. 1993;149(1):41–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moran JA, Dorevitch MI. Delirium in the hospitalized elderly. Australian Journal of Hospital Pharmacy. 2001;31:35–40. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray AM, Levkoff SE, Wetle TT, et al. Acute delirium and functional decline in the hospitalized elderly patient. J Gerontol. 1993;48(5):M181–M186. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.5.m181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inouye SK, Viscoli CM, Horwitz RI, Hurst LD, Tinetti ME. A predictive model for delirium in hospitalized elderly medical patients based on admission characteristics. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(6):474–481. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-6-199309150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McAvay GJ, Van Ness PH, Bogardus ST, et al. Older adults discharged from the hospital with delirium: 1-year outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(8):1245–1250. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leslie DL, Zhang Y, Bogardus ST, Holford TR, Leo-Summers LS, Inouye SK. Consequences of preventing delirium in hospitalized older adults on nursing home costs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(3):405–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chong MS, Chan MP, Kang J, Han HC, Ding YY, Tan TL. A new model of delirium care in the acute geriatric setting: geriatric monitoring unit. BMC Geriatr. 2011;11:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-11-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flaherty JH, Tariq SH, Raghavan S, Bakshi S, Moinuddin A, Morley JE. A model for managing delirious older inpatients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(7):1031–1035. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2389.2003.51320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lunström M, Edlund A, Karlsson S, Brännström B, Bucht G, Gustafson Y. A multifactorial intervention program reduces the duration of delirium, length of hospitalization, and mortality in delirious patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):622–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pitkälä KH, Laurila JV, Strandberg TE, Tilvis RS. Multicomponent geriatric intervention for elderly inpatients with delirium: a randomized, controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(2):176–181. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pitkala KH, Laurila JV, Strandberg TE, Kautiainen H, Sintonen H, Tilvis RS. Multicomponent geriatric intervention for elderly inpatients with delirium: effects on costs and health-related quality of life. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(1):56–61. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inouye SK, Bogardus ST, Charpentier PA, et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(9):669–676. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903043400901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inouye SK, Bogardus ST, Baker DI, Leo-Summers L, Cooney LM. The Hospital Elder Life Program: a model of care to prevent cognitive and functional decline in older hospitalized patients. Hospital Elder Life Program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(12):1697–1706. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inouye SK, Baker DI, Fugal P, Bradley EH, HELP Dissemination Project Dissemination of the hospital elder life program: implementation, adaptation, and successes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(10):1492–1499. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bradley EH, Webster TR, Schlesinger M, Baker D, Inouye SK. Patterns of diffusion of evidence-based clinical programmes: a case study of the Hospital Elder Life Program. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15(5):334–338. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2006.018820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rubin FH, Williams JT, Lescisin DA, Mook WJ, Hassan S, Inouye SK. Replicating the Hospital Elder Life Program in a community hospital and demonstrating effectiveness using quality improvement methodology. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(6):969–974. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cole MG, Primeau FJ, Bailey RF, et al. Systematic intervention for elderly inpatients with delirium: a randomized trial. CMAJ. 1994;151(7):965–970. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cole MG, McCusker J, Bellavance F, et al. Systematic detection and multidisciplinary care of delirium in older medical inpatients: a randomized trial. CMAJ. 2002;167(7):753–759. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michaud CJ, Thomas WL, McAllen KJ. Early pharmacological treatment of delirium may reduce physical restraint use: a retrospective study. Ann Pharmacother. 2013 Nov 18; doi: 10.1177/1060028013513559. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carrothers KM, Barr J, Spurlock B, Ridgely MS, Damberg CL, Ely EW. Contextual issues influencing implementation and outcomes associated with an integrated approach to managing pain, agitation, and delirium in adult ICUs. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(9 Suppl 1):S128–S135. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182a2c2b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldberg SE, Bradshaw LE, Kearney FC, et al. Medical Crises in Older People Study Group Care in specialist medical and mental health unit compared with standard care for older people with cognitive impairment admitted to general hospital: randomized controlled trial (NIHR TEAM Trial) BMJ. 2013;347:f4132. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f4132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mudge AM, Maussen C, Duncan J, Denaro CP. Improving quality of delirium care in a general medical service with established interdisciplinary care: a controlled trial. Intern Med J. 2013;43(3):270–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2012.02840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bee Gek Tay L, Chew Chan MP, Sian Chong M. Potential for functional recovery following delirium in older adults with dementia: impact of a multicomponent delirium management program. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(6):321–327. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chong MS, Tan KT, Tay L, Wong YM, Ancoli-Israel S. Bright light therapy as part of a multicomponent management program improves sleep and functional outcomes in delirious older hospitalized adults. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:565–572. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S44926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI. Clarifying confusion: the Confusion Assessment Method. A new method for detecting delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(12):941–948. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-12-941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong WC, Sahadevan S, Ding YY, Tan HN, Chan SP. Resource consumption in hospitalised, frail older patients. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2010;39(11):830–836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sahadevan S, Lim PP, Tan NJ, Chan SP. Diagnostic performance of two mental status tests in the older Chinese: influence of education and age on cut-off values. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15(3):234–241. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(200003)15:3<234::aid-gps99>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Atkins M, Burgess A, Bottomley C, Massino R. Chlorpromazine equivalents: a consensus of opinion for both clinical and research applications. Psychiatr Bull. 1997;21:224–226. [Google Scholar]

- 33.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV-TR. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. text revision. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chong MS, Sahadevan S. An evidence-based clinical approach to the diagnosis of dementia. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2003;32(6):740–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trzepacz PT, Mittal D, Torres R, Kanary K, Norton J, Jimerson N. Validation of the Delirium Rating Scale-revised-98: comparison with the delirium rating scale and the cognitive test for delirium. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001;13(2):229–242. doi: 10.1176/jnp.13.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rudolph JL, Boustani M, Kamholz B, Shaughnessey M, Shay K, American Delirium Society Delirium: a strategic plan to bring an ancient disease into the 21st century. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(Suppl 2):S237–S240. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lakatos BE, Capasso V, Mitchell MT, et al. Falls in the general hospital: association with delirium, advanced age, and specific surgical procedures. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(3):218–226. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.3.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Keeffe S, Lavan J. The prognostic significance of delirium in older hospital patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45(2):174–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb04503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vidán MT, Sánchez E, Alonso M, Montero B, Ortiz J, Serra JA. An intervention integrated into daily clinical practice reduces the incidence of delirium during hospitalization in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(11):2029–2036. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tropea J, Slee J, Holmes AC, Gorelik A, Brand CA. Use of antipsychotic medications for the management of delirium: an audit of current practice in the acute care setting. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21(1):172–179. doi: 10.1017/S1041610208008028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.González M, Martínez G, Calderón J, et al. Impact of delirium on short-term mortality in elderly inpatients: a prospective cohort study. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(3):234–238. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.3.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kiely DK, Marcantonio ER, Inouye SK, et al. Persistent delirium predicts greater mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(1):55–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02092.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]