Abstract

Background

Dizziness in the elderly is a serious health concern due to the increased morbidity caused by falling. The most common cause of dizziness in the elderly, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), is frequently undiagnosed, and bedside treatment of these patients can be difficult due to neck and back stiffness, which makes repeated and accurate repositioning maneuvers difficult.

Case presentation

After a fall, a 96-year-old woman was referred by a resident neurologist for intractable BPPV. The patient was placed on a motorized turntable and repositioned to remove the calcite particles from the affected posterior semicircular canal. Video monitoring of the eyes allowed confirmation of the diagnosis, as well as an immediate evaluation of the effectiveness of the maneuver.

Conclusion

Every patient with dizziness or imbalance, even in the absence of typical complaints of BPPV, should be tested with provocation maneuvers, because the clinical picture of BPPV is not always typical. Even if elderly patients with dizziness are very frail, the completion of provocation maneuvers is imperative, since the therapeutic maneuvers are extremely effective. A motorized turntable is very helpful to perform the repositioning accurately and safely.

Keywords: vestibulo ocular reflex, nystagmus, vertigo

Introduction

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) causes dizziness, imbalance, and nausea, and is fairly common, especially in the elderly, reaching a cumulative incidence of almost 10% at the age of 80.1 Moreover, unrecognized BPPV is strikingly frequent, with a prevalence of up to 9% in geriatric outpatient clinics.2 Imbalance due to BPPV is a serious health concern, since falling leads, directly or indirectly, to 12% of all deaths in elderly populations.3

BPPV occurs when calcite particles detach from the utricle and enter a semicircular canal of the inner ear.4 The canals are fluid-filled rotational sensors that transduce head rotational acceleration into a neural signal roughly proportional to head velocity. Due to the inertia of the endolymph fluid, head rotation causes a relative fluid flow, which bends the cupula membrane and deflects hair cells.5 When calcite particles enter the canal, the gravitational movement of the particles due to head tilt creates endolymphatic currents that cause cupular displacement, resulting in vertigo attacks accompanied by nystagmus. Head trauma can sometimes precipitate BPPV,6 though age-related degeneration of the otoconia probably contributes to the prevalence of BPPV in the elderly.7

Fortunately, repositioning maneuvers to move the particles out of the canals are highly efficient,8 and can lead to a significant reduction in the number of falls in the elderly.9 The effectiveness of these maneuvers in the elderly is controversial, with some studies suggesting they are less effective10 and others finding no age-related difference in outcome.11 Bedside treatment of the elderly can be difficult due to neck and back stiffness, which makes accurate and repeated maneuvers difficult. This issue can be overcome by treating frail elderly patients on a motorized turntable that safely moves them to displace the particles from the affected canal.8

Case presentation

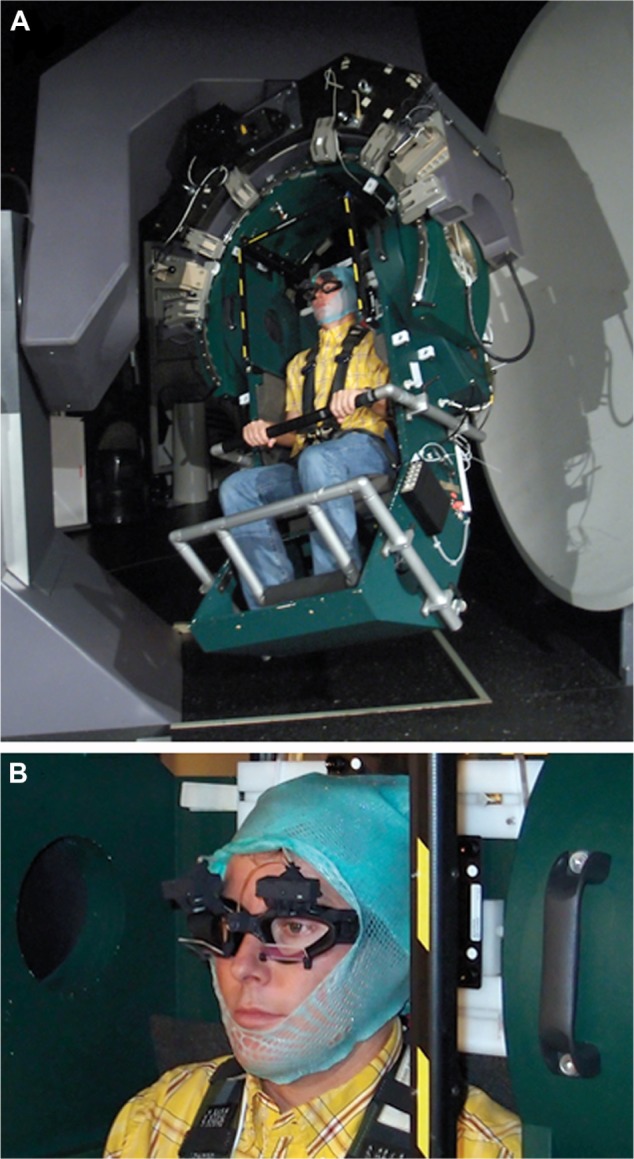

A 96-year-old patient was hospitalized after experiencing a fall that resulted in a broken pubic bone. The patient complained of short-lasting dizziness when stooping, and the resident neurologist diagnosed BPPV of the right posterior canal. Due to the age and frailty of the patient after the fall, manual repositioning treatments were not attempted, and the patient was referred to our dizziness clinic. We performed an Epley repositioning maneuver12 with the patient firmly and safely seated in a motorized turntable (see Figure 1 and Supplementary video). Video monitoring of the eyes allowed us to confirm the diagnosis of the affected canal by the presence and direction of typical vertical-torsional nystagmus, and to immediately evaluate the effectiveness of the liberation maneuver.

Figure 1.

Turntable and eye movement recording setup. (A) The motorized three-dimensional turntable (Acutronic, Bubikon, Switzerland) showing author CJB. Subjects are comfortably padded with pillows and securely fastened to the chair with a five-point pilot harness, while the head is restrained with an individually molded thermoplastic mask. To give a further sense of security, subjects hold a hand bar, while the feet are restrained with a footrest. (B) Video goggles (EyeSeeCam, Munich, Germany), mounted under a thermoplastic mask to minimize head movements, are used to monitor and record eye movements.

Video S1 shows the eye movements of the patient during the treatment. The patient was first slowly rotated backwards by 120° in the plane of the right posterior canal (Dix–Hallpike maneuver),13 eliciting up-beating nystagmus induced by particle movement. There was also a small torsional component that beat counterclockwise (toward the affected right ear), however, this is difficult to appreciate in the video. This nystagmus is expected from canalolithiasis of the right posterior semicircular canal. An Epley repositioning maneuver was then performed, rotating the patient about the body yaw axis until the patient looked downward, 45° from horizontal. Due to the age of the patient, we returned her upright immediately to minimize discomfort. No nystagmus was observed during the Epley maneuver, perhaps because the stimulation was lower due to particle displacement as a result of the previous Dix–Hallpike maneuver. A second Dix–Hallpike maneuver tested the effectiveness of the repositioning, as we occasionally find that residual symptoms persist after a single treatment. No nystagmus was observed after the second backward movement, showing that the single repositioning had successfully displaced the calcite particles from the posterior canal, curing the patient. Follow-up of the patient several months later confirmed that she no longer experienced positional vertigo.

Discussion and conclusion

Treating patients with BPPV on a motorized turntable offers several advantages over bedside treatment,8 including increased precision and the repeatability of maneuvers for both diagnosing the affect canal(s) and treatment. The elderly deserve special consideration because accurate manual repositioning can be difficult due to neck and back stiffness, compounded by hesitancy of the treating physician to move a frail patient. While some patients express reservation upon seeing the turntable, our experience is that the elderly are quite receptive and tolerate the treatments well. In the past year, we have treated over 90 patients on the turntable without adverse consequences, and similar devices have been described and used in even greater numbers of patients,8 demonstrating the safety of using motorized turntables in treating BPPV. Turntable repositioning is suitable for most patients but may not be possible in the presence of claustrophobia, morbid obesity, cervical fractures, or severe respiratory or cardiac insufficiency.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the referring physicians, Drs Walter Waespe and Sarah Marti, and Marco Penner for technical support. This study was supported by the Betty and David Koetser Foundation for Brain Research, Zurich, Switzerland.

Footnotes

Author contributions

CJB collected and analyzed the data and drafted the article. DS was responsible for managing the patient and was involved in writing the article. KPW conceived the idea of the article and was involved in writing the article. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editor of this journal.

Disclosure

KPW acts as an unpaid consultant and has received funding for travel from GN Otometrics. CJB and DS declare no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.von Brevern M, Radtke A, Lezius F, et al. Epidemiology of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a population based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78(7):710–715. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.100420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oghalai JS, Manolidis S, Barth JL, Stewart MG, Jenkins HA. Unrecognized benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in elderly patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122(5):630–634. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(00)70187-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baraff LJ, Della Penna R, Williams N, Sanders A. Practice guideline for the ED management of falls in community-dwelling elderly persons. Kaiser Permanente Medical Group. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;30(4):480–492. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(97)70008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parnes LS, McClure JA. Free-floating endolymph particles: a new operative finding during posterior semicircular canal occlusion. Laryngoscope. 1992;102(9):988–992. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199209000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rabbitt RD, Damiano ER. A hydroelastic model of macromechanics in the endolymphatic vestibular canal. J Fluid Mech. 1992;238:337–369. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katsarkas A. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV): idiopathic versus post-traumatic. Acta Otolaryngol. 1999;119(7):745–749. doi: 10.1080/00016489950180360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jang YS, Hwang CH, Shin JY, Bae WY, Kim LS. Age-related changes on the morphology of the otoconia. Laryngoscope. 2006;116(6):996–1001. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000217238.84401.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakayama M, Epley JM. BPPV and variants: improved treatment results with automated, nystagmus-based repositioning. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;133(1):107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gananca FF, Gazzola JM, Gananca CF, Caovilla HH, Gananca MM, Cruz OL. Elderly falls associated with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;76(1):113–120. doi: 10.1590/S1808-86942010000100019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Batuecas-Caletrio A, Trinidad-Ruiz G, Zschaeck C, et al. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in the elderly. Gerontology. 2013;59(5):408–412. doi: 10.1159/000351204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lea P, Kushnir M, Shpirer Y, Zomer Y, Flechter S. Approach to benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in old age. Isr Med Assoc J. 2005;7(7):447–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Epley JM. The canalith repositioning procedure: for treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;107(3):399–404. doi: 10.1177/019459989210700310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dix MR, Hallpike CS. The pathology symptomatology and diagnosis of certain common disorders of the vestibular system. Proc R Soc Med. 1952;45(6):341–354. doi: 10.1177/003591575204500604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]