Abstract

The aim of this article is to clarify diagnostic pitfalls of pancreatic serous cystic neoplasm (SCN) that may result in erroneous characterization. Usual and unusual imaging findings of SCN as well as potential SCN mimickers are presented. The diagnostic key of SCN is to look for a cluster of microcysts (honeycomb pattern), which may not be always found in the center. Fibrosis in SCN may be mistaken for a mural nodule of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN). The absence of cyst wall enhancement may be helpful to distinguish SCN from mucinous cystic neoplasm. However, oligocystic SCN and branch duct type IPMN may morphologically overlap. In addition, solid serous adenoma, an extremely rare variant of SCN, is difficult to distinguish from neuroendocrine tumor.

Keywords: Serous cystic neoplasm, Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm, Mucinous cystic neoplasm, Computed tomography, Magnetic resonance imaging

Core tip: Most serous cystic neoplasm (SCN) consist of a combination of microcystic, macrocystic, and solid-appearing components. The imaging appearance of each component simply reflects the different sizes of cysts that comprise the SCN. The diagnostic key of SCN is to look for a cluster of microcysts (honeycomb pattern). However, differentiation between oligocystic SCN and branch duct type intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm, and between neuroendocrine tumor and extremely rare solid serous adenoma, may be difficult.

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic serous cystic neoplasm (SCN) is almost always benign[1-3]. Surgical resection may be indicated when it is large or symptomatic (e.g., recurring pancreatitis), or when it is difficult to distinguish from potentially malignant mucin-producing pancreatic cystic neoplasms, such as intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) and mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN)[4-8]. However, unusual imaging findings of SCN may result in mischaracterization and lead to unnecessary surgical resection. Therefore, it is important to be aware of unusual imaging findings of SCN and possible causes of mischaracterization. The aim of this manuscript is to clarify unusual imaging findings and diagnostic pitfalls of SCN that may result in erroneous characterization. Surgically resected SCN cases were reviewed and compared to the imaging findings of MCN and IPMN. Additionally, imaging findings of SCN mimickers are presented.

SCN

Between 2001 and 2011, 16 cases of pancreatic SCN were surgically resected. On preoperative imaging, seven of 16 (43.8%) were correctly characterized as SCN (no other differential diagnoses or most likely diagnosis). However, nine of 16 (56.2%) were not correctly diagnosed as SCN. Two were diagnosed as less likely for SCN (SCN was included in the differential diagnoses, but it was not the most likely diagnosis), and seven were mischaracterized as unlikely for SCN (SCN was not included in the differential diagnoses). Of these nine mischaracterized cases, the most likely imaging diagnoses were IPMN (n = 5), MCN (n = 3), and neuroendocrine tumor (NET) (n = 1).

There were 6 male and 10 female patients. The ages ranged from 27 to 75 years old (mean 57 years old). Six of the SCNs were found in the pancreatic head and 10 were in the pancreatic body/tail. The sizes ranged from 2.1 to 7.4 cm (mean 4.5 cm).

Because SCN is not usually surgically resected, there were a substantial number of mischaracterized SCN cases in this patient population. We retrospectively reviewed these 16 cases and clarified the potential causes for mischaracterization.

CONTROL GROUPS

MCN

Between 2001 and 2011, there were 23 surgically resected pancreatic MCN cases. There was one male patient and 22 female patients. The ages ranged from 17 to 76 years old (mean 42 years old). All but one case were found in the body/tail. The sizes ranged from 2.5 to 13.7 cm (mean 5.7 cm).

IPMN

Between 2007 and 2011, there were 72 IPMN cases that were further evaluated by multidetector-row CT (MDCT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)/MR cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) for preoperative planning. In the clinical setting, many IPMNs are easily diagnosed if the communication with the main pancreatic duct (MPD) and prominent downstream MPD are evident. To focus on diagnostically problematic cases, we selected IPMN cases based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) branch duct type IPMN; (2) no communication with the pancreatic duct on MRCP; (3) no downstream MPD dilatation; and (4) no large solid component occupying the cystic space.

There were seven branch duct type IPMN cases that fit the inclusion criteria. All seven cases were surgically proven. There was one male patient and six female patients. The ages ranged from 45 to 72 years old (mean 62 years old). All were found in the pancreatic body/tail. The sizes ranged from 3.4 to 4.6 cm (mean 3.8 cm).

IMAGING REVIEW

Imaging classification of SCN

MRCP and contrast-enhanced dynamic MDCT or MRI studies of SCN were reviewed, and components of the SCN were classified into three types: microcystic, macrocystic, and solid-appearing. A microcystic component referred to a cluster of microcysts that displayed a honeycomb pattern (high signal on MRCP, Figure 1)[9-14]. A macrocystic component was defined as a cyst larger than 2 cm (Figure 2)[15-17]. A solid-appearing component was defined as having no high signal on MRCP with iso to high attenuation/signal intensity on the pancreatic parenchymal phase (radiologically solid regardless of whether it was histologically solid or microcystic, Figure 3).

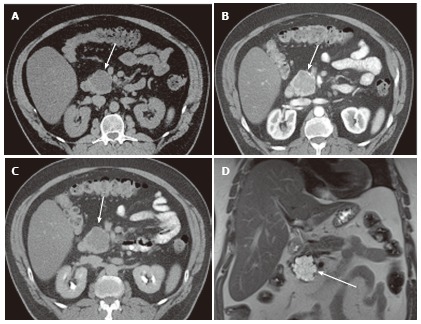

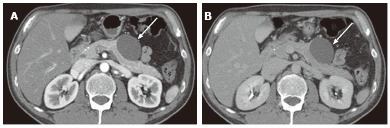

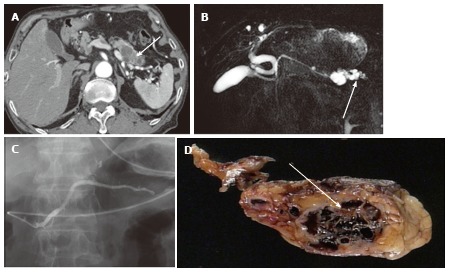

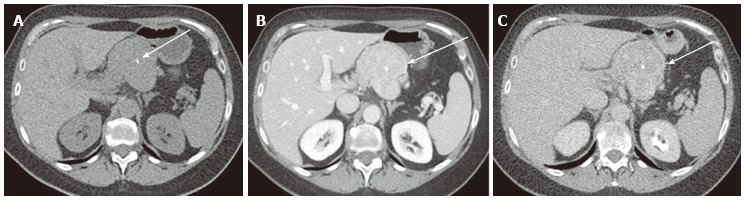

Figure 1.

A 65-year-old male with clinically diagnosed typical microcystic serous cystic neoplasm. A: Unenhanced axial computed tomography (CT) shows a low density mass (arrow) relative to the pancreatic head; B: The pancreatic parenchymal phase of a contrast-enhanced CT shows mild patchy tumor enhancement (arrow); C: The equilibrium phase shows the mass to be low density (arrow); D: Coronal T2-weighted single-shot fat saturation-echo magnetic resonance image clearly demonstrate the mass (arrow) consisting of a cluster of microcysts (honeycomb pattern).

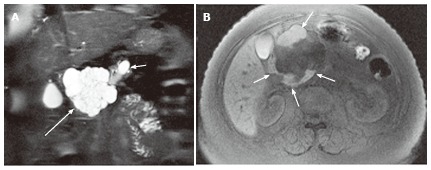

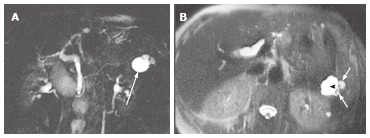

Figure 2.

A 57-year-old female with mixed microcystic and macrocystic serous cystic neoplasm. A: Coronal T2-weighted single-shot fast spin-echo magnetic resonance (MR) image with fat saturation shows a cystic mass (large arrow) in the pancreatic head consisting of central microcysts and peripheral macrocysts. The small arrow indicates dilatation of the upstream main pancreatic duct. B: Axial T1-weighted gradient-echo MR image with fat saturation shows high intensity fluid in the macrocysts (arrows), representing hemorrhage. Hemorrhage may be seen in macrocysts, although it is uncommon.

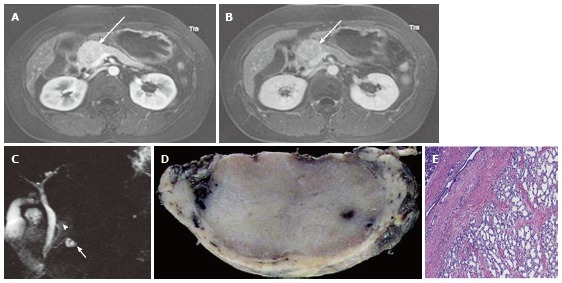

Figure 3.

A 43-year-old female with solid-appearing serous cystic neoplasm in the pancreatic head. A: The arterial phase of an axial contrast enhanced (CE) T1-weighted gradient-echo (GRE) magnetic resonance (MR) image with fat saturation shows an enhancing mass in the pancreatic head (arrow); B: The equilibrium phase of an axial CE T1-weighted GRE MR imaging shows the tumor (arrow) to be low intensity (wash-out); C: The pancreatic head mass (arrowhead) is not clearly demonstrated on MR cholangiopancreatography. The pancreatic head mass appears radiologically solid (solid-appearing). An arrow shows a concomitant small intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm; D: Macroscopic view of the resected specimen shows the mass appears solid; E: Microscopic view shows the tumor consisting of small cystic structures with intervening fibrous stroma.

Based on the SCN components, SCN were classified as: (1) microcystic type; (2) oligocystic type (consisting of a macrocyst and a few small cysts without a honeycomb pattern)[15-17]; (3) solid-appearing type; and (4) mixed type (combination of at least two different components, Figure 2).

Based on the imaging classification of SCN, nine mischaracterized cases were reviewed and potential causes of mischaracterization were clarified.

Wall enhancement and wall thickness

Presence or absence of cyst wall enhancement and wall thickness were compared between macrocysts in SCN and control groups (branch duct type IPMN and MCN). Cyst wall enhancement was evaluated on the axial images of the equilibrium phase of contrast-enhanced CT (4 min after initiation of the intravenous contrast). For this evaluation, the portions where lesions abutted the pancreatic parenchyma or adjacent organs were avoided.

If wall enhancement was appreciated, wall thickness was measured. Cyst wall thickness was classified as follows: (1) wall thickness was 2 mm or more; (2) wall enhancement was perceptible but wall thickness was less than 2 mm; and (3) no wall enhancement. Cyst wall thickness was compared between macrocysts in SCN and control groups (IPMN and MCN).

ADDITIONAL CASE PRESENTATION

To better illustrate imaging findings of SCN, additional cases of usual and unusual SCN and SCN mimickers are presented.

OUTCOME

Of the surgically resected pancreatic SCN, there were six microcystic, five oligocystic, four mixed, and one solid-appearing type (Figure 3). Of the four mixed types, three were mixed microcystic and macrocystic, and one was mixed microcystic and solid (Figure 4). Therefore, ten of 16 (62.5%) had microcystic and eight of 16 (50%) had macrocystic components. Eight cases were further evaluated for the presence or absence of cyst wall enhancement and wall thickness.

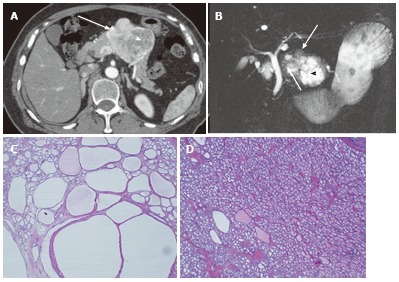

Figure 4.

A 64-year-old female with mixed microcystic and solid-appearing serous cystic neoplasm. A: The pancreatic parenchymal phase of an axial contrast enhanced-computed tomography (CT) shows a large enhancing mass in the pancreatic body. The right side of the tumor shows avid arterial enhancement (arrow), and the left side is low density (arrowheads); B: Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography shows a microcystic component at the left side of the tumor (arrowhead) that corresponds to the low density area on CT. In contrast, the right side of the tumor is radiologically solid-appearing (arrow); C: Microscopic view of the left side of the tumor [microcystic component (arrowheads in A and B)] consists of various sizes of small cystic spaces; D: Microscopic view of the right side of the tumor [solid-appearing component (arrows in A and B)] consists of smaller sized microcysts. It is radiologically solid-appearing but histologically microcystic.

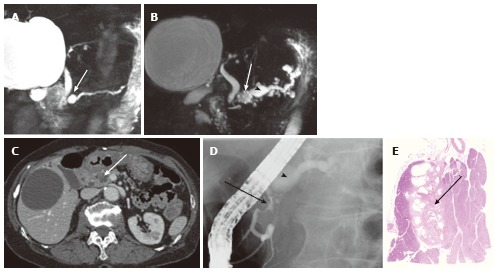

Of the nine mischaracterized SCN cases, there were five oligocystic (Figures 5 and 6), two microcystic, one mixed micro and macrocystic, and one solid-appearing type. All five oligocystic SCN were mischaracterized as either IPMN (Figure 7) or MCN. In two microcystic SCNs, fibrosis in the cystic lesion was erroneously characterized as a mural nodule of IPMN (Figures 8 and 9). In two of three mixed micro and macrocystic SCN, a cluster of microcysts was noted at the peripheral portion (not centrally located) (Figure 10), and one was mischaracterized as a branch duct type IPMN. One solid-appearing SCN was mischaracterized as a neuroendocrine tumor (Figure 3).

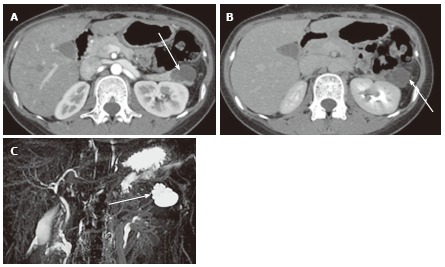

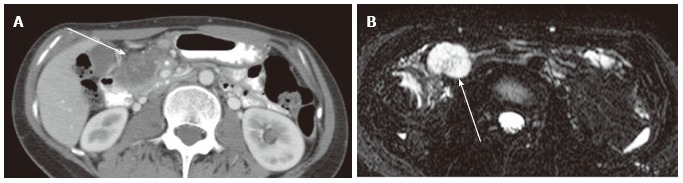

Figure 5.

A 40-year-old female with oligocystic serous cystic neoplasm (unilocular). A: The pancreatic parenchymal phase of an axial contrast enhanced-computed tomography shows a unilocular cystic mass arising from the pancreatic body (arrow); B: The equilibrium phase shows no cyst wall enhancement (arrow).

Figure 6.

A 61-year-old female with oligocystic serous cystic neoplasm showing a cyst-by-cyst pattern. A: Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography demonstrates a cystic mass (arrow) in the pancreatic tail consisting of a macrocyst and two adjacent smaller cysts; B: Axial T2-weighted single-shot fast spin-echo magnetic resonance image shows a lobulated macrocyst (arrowhead) with adjacent smaller cysts (small arrows) in the pancreatic tail (cyst-by-cyst pattern).

Figure 7.

A 45-year-old female with branch duct type intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm mimicking oligocystic serous cystic neoplasm (also see Figure 6). A: Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography shows a cystic mass (arrow) in the body of the pancreas. The communication with the main pancreatic duct (MPD) is not apparent even with the source images (not shown). There is no downstream MPD dilatation; B: Axial T2-weighted single-shot fast spin-echo magnetic resonance image with fat saturation demonstrates a mass showing a cyst-by-cyst pattern (arrow); C: Endoscopic retrograde pancreatography shows the cystic lesion to be opacified (arrow), representing communication with the pancreatic duct.

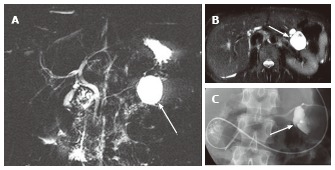

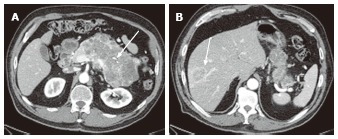

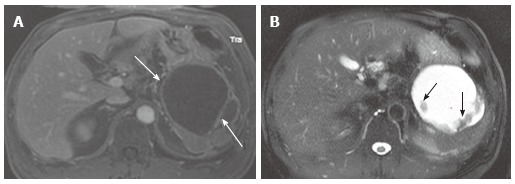

Figure 8.

A 74-year-old female with microcystic serous cystic neoplasm and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. A: Magnetic resonance cholangiopancr -eatography (MRCP) shows a cystic mass (arrow) in the pancreatic head with mild upstream main pancreatic duct (MPD) dilatation; B: Follow-up MRCP 5 years after Figure 8A shows interval increase in size of the cystic lesion (arrow) with fusiform dilatation of the upstream MPD (arrowhaed) and cystic dilatation of multiple branch ducts. In retrospect, the cystic lesion in the pancreatic head appears microcystic without downstream MPD dilatation; C: The portal venous phase of an axial contrast enhanced-computed tomography shows an enhancing component (arrow) within the cystic lesion. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) with solid component was suspected; D: Endoscopic retrograde pancreatography shows extrinsic compression of the MPD due to the cystic lesion in the pancreatic head (arrow) without cyst opacification, although fusiform dilatation of the upstream MPD (arrowhead) is demonstrated; E: Resected specimen shows the cystic mass in the pancreatic head consisting of microcysts. The enhancing component eventually represented fibrosis (arrow) within microcystic serous cystic neoplasm. In addition, the fusiform dilatation of the MPD turned out to be IPMN.

Figure 9.

A 74-year-old male with microcystic serous cystic neoplasm mischaracterized as intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm with a solid component. A: The pancreatic parenchymal phase of an axial contrast enhanced-computed tomography shows a cystic lesion with an enhancing component (arrow) in the pancreatic tail; B: Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) shows the cystic lesion to be elongated, and the upstream main pancreatic duct (MPD) appears to be dilated (arrow). There is no dilatation of the downstream MPD. The extrahepatic bile duct is tortuous, likely due to distal gastrectomy (Billroth I reconstruction); C: Endoscopic retrograde pancreatography shows the cystic lesion to be unopacified. There is no communication with the pancreatic duct or upstream MPD dilatation. MRCP findings eventually represented a part of the cystic lesion along the course of the pancreas rather than MPD dilatation (arrow, B); D: Macroscopic view of the resected specimen (short axis cut section) shows the cystic lesion consisting of microcysts and fibrosis (arrow).

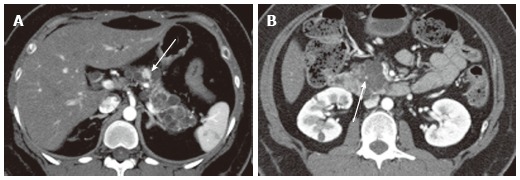

Figure 10.

A 27-year-old female with mixed microcystic and macrocystic serous cystic neoplasm. A: The pancreatic parenchymal phase of an axial contrast enhanced- computed tomography shows a lobulated cystic mass (arrow) in the pancreatic tail; B: The equilibrium phase shows no cyst wall enhancement (arrow); C: Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography clearly shows a cluster of microcysts (honeycomb pattern) in the peripheral portion of this cystic lesion (arrow).

The presence or absence of cyst wall enhancement and wall thickness is shown in Table 1. In SCN, seven of eight showed no wall enhancement (Figures 5 and 10). In contrast, all of the MCN cases (n = 23) showed wall enhancement and 15 (65.2%) showed 2 mm or more wall thickness. Of the branch duct type IPMN cases (n =7), four showed wall enhancement but three did not. There was a significant difference with respect to wall enhancement and wall thickening between SCN and MCN (P < 0.01, Kruskal-Wallis test), although there was no significant difference between SCN and branch duct type IPMN.

Table 1.

Cyst wall enhancement and wall thickness n (%)

| No wall enhancement | Wall thickness < 2 mm | Wall thickness ≥ 2 mm | |

| SCNb | 7 (87.5) | 1 (12.5) | 0 |

| MCNb | 0 | 8 (34.8) | 15 (65.2) |

| IPMN | 3 (42.9) | 3 (42.9) | 1 (14.3) |

SCN: Serous cystic neoplasm; MCN: Mucinous cystic neoplasm; IPMN: Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. Typically, macrocysts in SCN show no wall enhancement and MCNs show wall enhancement. IPMN may or may not show wall enhancement. There is a significant difference between SCN and MCN (bP < 0.01, Kruskal-Wallis test), although no significant difference is shown between SCN and IPMN. The presence or absence of wall enhancement is helpful for differentiating SCN vs MCN, but it is not for SCN vs IPMN. In addition, MCN may present as a relatively thin-walled cyst (< 2 mm).

DISCUSSION

Pancreatic SCN is almost always benign (> 98%)[1,2]. The American College of Radiology[18] recommends consideration of surgical resection for SCN larger than 4 cm. However, most previously reported malignant SCNs with evidence of metastatic disease were larger than 10 cm[1,2] (Figure 11). Therefore, a threshold of 4 cm potentially includes many benign SCNs. As long as it is not symptomatic, this size criterion alone may not warrant surgical resection. Moreover, to avoid unnecessary surgical resection, it is important, not only to be familiar with typical imaging findings of SCN, but to also understand unusual imaging findings and diagnostic pitfalls.

Figure 11.

A 78-year-old female with a large serous cystic neoplasm with liver metastasis. A: The pancreatic parenchymal phase of an axial contrast enhanced- computed tomography (CT) demonstrates a large low density mass with patchy enhancement in the body and tail of the pancreas. Central calcification is noted (arrow); B: Axial CT cranial to Figure 11A shows a low density liver mass with peripheral and patchy enhancement in segment VIII (arrow). The appearance is similar to the pancreatic mass.

Typical imaging findings of SCN are well known. Microcystic SCN consists of a cluster of microcysts; the so-called “honeycomb pattern”[10-14] (Figure 1). Microcystic SCN can be hypervascular and may appear solid on contrast-enhanced computed tomography. MRI and MRCP can clearly demonstrate the microcystic nature of the lesion[9]. A macrocyst is defined as a cyst measuring more than 2 cm (or 1 cm) in diameter[1,15-17]. The mixed type most commonly consists of microcystic and macrocystic components[10,11,19]. Typically, microcysts are noted in the center and macrocysts are located peripherally[10,11,19]. In addition, fibrosis with or without calcification may be seen in the center[10,11,19].

In our series, two microcystic SCNs were mischaracterized as IPMN with mural nodule because fibrosis in the SCN mimicked a mural nodule. One case showed interval growth (Figure 8) with dilatation of the MPD. Dilatation of the MPD turned out to be a concomitant IPMN. In spite of benignancy, it has been reported that SCN may show interval growth on imaging follow-up[19-21]. Another case demonstrated an elongated shape along the course of the pancreatic tail (Figure 9), and part of the cystic lesion was erroneously considered MPD dilatation. In retrospect, neither case demonstrated downstream MPD dilatation, nor did endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography (ERCP) demonstrate communication between the cystic lesions and the MPD.

When diagnosing mixed micro and macrocystic SCN, the diagnostic key is to look for a honeycomb pattern. It should be emphasized that the honeycomb pattern may not always be in the central portion. The honeycomb pattern may be seen peripherally (Figure 10), and MRI/MRCP can better characterize and demonstrate a cluster of microcysts than CT. In addition, it may be helpful to understand the imaging spectrum of SCN by explaining that most SCNs consist of the combination of microcystic, macrocystic, and solid-appearing components. The imaging appearance of each component simply reflects the different sizes of cysts that comprise the SCN.

Solid variant SCN (solid serous adenoma) is extremely rare[22-24]. Even though imaging findings often appear solid (not very bright on MRCP with hypervascularity), it may be histologically microcystic (Figure 3). That is why we call such imaging findings “solid-appearing”. Solid-appearing components may be seen in mixed type SCNs (Figure 4). The differential diagnosis of solid serous adenoma (histologically solid) and solid-appearing SCN is neuroendocrine tumor (NET). Hayashi et al[25] reported that the Hounsfield units of SCN on unenhanced CT were lower than those of NET, and the relative wash-out ratio was higher in SCN than in NET. According to Hayashi et al[25], unenhanced CT showed all three SCNs to be low density and only one of 14 NETs to be low density. The delayed phase showed two of three SCNs to be low density (wash-out) but NET did not show wash-out. These criteria may be useful for the differential diagnosis between solid-appearing (histologically microcystic) SCN and NET because no contrast stasis is expected in the microcystic spaces of SCN. However, for solid serous adenoma (histologically solid), it is uncertain if this criteria is helpful for the differential diagnosis because fibrosis in solid serous adenoma may cause delayed enhancement of the lesion (Figure 12). Additionally, the enhancement pattern of NET is variable, and NET can be low density in the delayed phase (Figure 13). If imaging findings do not suggest a microcystic nature, endoscopic ultrasound-guided biopsy should be considered to exclude NET.

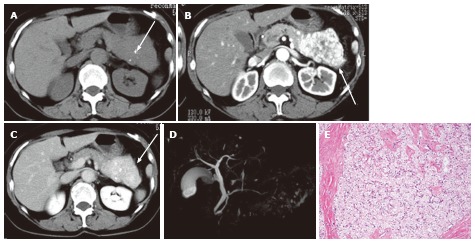

Figure 12.

A 65-year-old female with solid serous adenoma. A: Unenhanced axial computed tomography shows a large mass with central calcification (arrow) in the tail and body of the pancreas. The lesion is isodense to the normal pancreatic parenchyma; B: The pancreatic parenchymal phase shows avid tumor enhancement (arrow); C: The equilibrium phase shows the mass to be high density (arrow) relative to the normal pancreatic parenchyma, representing persistent enhancement (no wash-out); D: Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography does not show the mass or cystic spaces; E: Microscopic view of the resected specimen shows a solid nest of tumor cells with abundant fibrous stroma.

Figure 13.

A 65-year-old male with neuroendocrine tumor (well-differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma). A: Unenhanced axial computed tomography shows a large mass with central calcification (arrow) in the pancreatic body; B: The venous phase shows moderate and relatively homogeneous tumor enhancement (arrow). (The arterial phase was not available for this case); C: The delayed phase shows the tumor to be low density (arrow). Wash-out may not always be suggestive of serous cystic neoplasm (also see Figure 12).

Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) associated SCN is another variant of SCN (Figure 14)[26]. VHL-associated SCN is usually multifocal, and it may present as diffuse pancreatic involvement[26]. In patients with VHL disease, concomitant NET may be encountered[26,27]. In addition, cases of SCN concomitant NET and mixed SCN and NET have been reported in patients with and without VHL disease[28-30]. Similar to solid serous adenoma, prospective imaging diagnosis of mixed SCN and NET is difficult.

Figure 14.

A 43-year-old female with von Hippel-Lindau disease. A: The arterial phase of an axial contrast enhanced-computed tomography demonstrates numerous cystic lesions in the body and tail of the pancreas. There is a solid hypervascular lesion in the pancreatic body (arrow), representing neuroendocrine tumor; B: A multilocular cystic lesion in the pancreatic head consists of a punctate central calcification (arrow) with microcystic (right side) and macrocystic (left side) components, representing serous cystic neoplasm.

Oligocystic SCN consists of a macrocyst and a few small cysts showing a “cyst-by-cyst” pattern[15-17]. In our series, the cyst wall of the macrocyst was thin, and wall enhancement was not typically seen. Owing to a common capsule, wall enhancement is seen in MCN[31,32]. We evaluated cyst wall enhancement in the equilibrium phase CT because we hypothesized that the contrast enhancement of fibrosis in the capsule would be more conspicuous in equilibrium than in the arterial or portal venous phases. The presence or absence of cyst wall enhancement may be helpful for the differential diagnosis between oligocystic SCN and MCN (Figure 5), although the cyst wall of MCN may be thin (< 2 mm) in some cases. On the other hand, distinguishing oligocystic SCN from branch duct type IPMN may be difficult[33,34], especially when MDCT or MRI/MRCP fails to demonstrate the communication with the pancreatic duct (Figure 7). Because the presence or absence of cyst wall enhancement is not helpful, and oligocystic SCN lacks a honeycomb pattern, imaging findings of oligocystic SCN and IPMN may overlap (Figures 6 and 7). Even though it is morphologically suspicious for an oligocystic SCN, branch duct type IPMN cannot be excluded because branch duct type IPMN is more common than oligocystic SCN. In such cases, ERCP (to evaluate the communication with the MPD) or EUS-guided cyst aspiration may be necessary to differentiate the two[35-40].

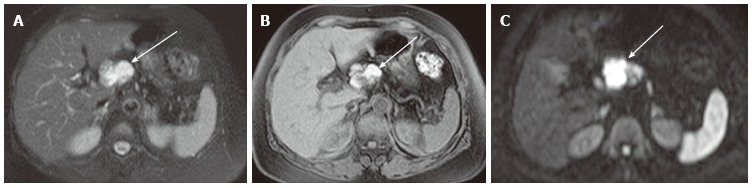

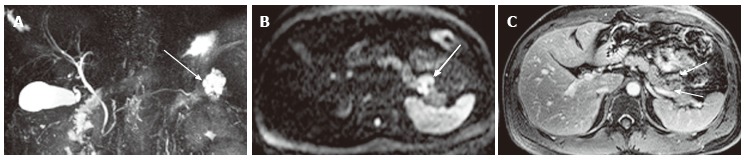

Other than IPMN and MCN, non-neoplastic pancreatic cysts such as lymphoepithelial cyst (LEC)[41,42] (Figure 15) and extensively necrotic/hemorrhagic pancreatic tumors such as solid pseudopapillary neoplasm (SPN) (Figure 16) may mimic SCN[43-46]. Both LEC and SPN may present as high intensity masses on T2-weighted images and MRCP. Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) is helpful for the differential diagnosis because LEC and SPN may show high intensity on DWI owing to high proteinaceous fluid and hemorrhage/solid components, respectively. In contrast, it is unusual for SCN to contain proteinaceous or hemorrhagic fluid although SCN can be partially hemorrhagic (Figure 2)[19]. In addition, care should be taken to exclude extrapancreatic masses such as peripancreatic lymphadenopathy. Necrotic lymph nodes or metastasis from mucinous adenocarcinoma may mimic pancreatic cystic neoplasms (Figure 17).

Figure 15.

A 72-year-old female with pancreatic lymphoepithelial cyst. A: Axial T2-weighted fast spin-echo magnetic resonance (MR) image with fat saturation shows a high intensity mass (arrow), which is exophytic from the neck of the pancreas (not shown); B: Axial T1-weighted gradient-echo (GRE) MR image with fat saturation shows the mass to be high intensity (arrow). Findings on T2-weighted image (Figure 14A) may mimic microcystic serous cystic neoplasm (SCN). However, the widespread distribution of high signal is somewhat unlikely for hemorrhage within microcysts of SCN because each locule should be separated by multiple septations; C: Axial diffusion-weighted MR image (b-factor = 1000) shows the mass to be high intensity (arrow), unlikely for SCN.

Figure 16.

A 39-year-old male with solid pseudopapillary neoplasm. A: Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography shows a high intensity pancreatic tail mass (arrow) that appears as a cluster of microcysts, mimicking microcystic serous cystic neoplasm (SCN); B: Axial diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) image (b-factor = 1000) shows the mass to be high intensity (arrow), unlikely for microcystic SCN; C: The equilibrium phase of an axial contrast enhanced T1-weighted gradient-echo MR image shows peripheral solid enhancing component within the tumor (arrows).

Figure 17.

A 32-year-old female with lymph node metastasis from mucinous adenocarcinoma of the transverse colon (not shown). A: The portal venous phase of an axial computed tomography shows a low density mass (arrow) adjacent to the pancreatic head (asterisk); B: Axial magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography shows the mass to be high intensity, mimicking microcystic serous cystic neoplasm (SCN). However, the presence of primary tumor and the lesion location (transverse mesocolon) are suggestive of lymph node metastasis rather than microcystic SCN.

Pancreatic pseudocyst is a common non-neoplastic cystic lesion occurring after pancreatitis or trauma[47-49]. Pancreatic pseudocyst typically presents as a unilocular cyst. The thickness of cyst wall varies depending on the ages of pseudocysts. Cyst wall enhancement may not be seen or may be barely seen at an earlier age. However, differentiating acute pseudocysts from SCN may not be problematic because recent episodes of pancreatitis or trauma should be documented. In chronic pseudocyst, a thickened enhancing cyst wall can be seen (Figure 18). For chronic pseudocyst without documented history of pancreatitis, the distinction from MCN may be more difficult. Additionally, cases of SCN with subtotal cystic degeneration have been reported[50], which may be difficult to distinguish from pseudocyst.

Figure 18.

A 56-year-old male with chronic pancreatic pseudocyst. A: The venous phase of an axial contrast enhanced T1-weighted gradient-echo magnetic resonance image demonstrates a cystic lesion with thick cyst wall and septation (arrows) arising from the pancreatic tail. Although this is a male patient, making mucinous cystic neoplasm unlikely, imaging findings of chronic pseudocyst may still mimic mucinous cystic neoplasm; B: The axial fast spin-echo T2-weighted magnetic resonance image with fat saturation shows non-enhancing debris (A) attached to the cyst wall and the septum (arrows).

CONCLUSION

The diagnostic key of microcystic or mixed micro and macrocystic SCN is to look for a honeycomb pattern, which may not always be located in the center. Care should be taken not to erroneously characterize fibrosis in SCN as a mural nodule of IPMN. Although the presence or absence of cyst wall enhancement in the equilibrium phase may be helpful for the differential diagnosis between SCN with macrocysts and MCN, it is not helpful for SCN versus branch duct type IPMN. Differentiation between oligocystic SCN and branch duct type IPMN, and between NET and extremely rare solid serous adenoma, may be difficult.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author would like to thank Nichole Jenkins, MA, Department of Radiology University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics for her assistance in editing this manuscript.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers: Ding MX, Karatag O S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

References

- 1.Kimura W, Moriya T, Hirai I, Hanada K, Abe H, Yanagisawa A, Fukushima N, Ohike N, Shimizu M, Hatori T, et al. Multicenter study of serous cystic neoplasm of the Japan pancreas society. Pancreas. 2012;41:380–387. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31822a27db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khashab MA, Shin EJ, Amateau S, Canto MI, Hruban RH, Fishman EK, Cameron JL, Edil BH, Wolfgang CL, Schulick RD, et al. Tumor size and location correlate with behavior of pancreatic serous cystic neoplasms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1521–1526. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galanis C, Zamani A, Cameron JL, Campbell KA, Lillemoe KD, Caparrelli D, Chang D, Hruban RH, Yeo CJ. Resected serous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas: a review of 158 patients with recommendations for treatment. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:820–826. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0157-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanaka M, Fernández-del Castillo C, Adsay V, Chari S, Falconi M, Jang JY, Kimura W, Levy P, Pitman MB, Schmidt CM, et al. International consensus guidelines 2012 for the management of IPMN and MCN of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2012;12:183–197. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Talukdar R, Nageshwar Reddy D. Treatment of pancreatic cystic neoplasm: surgery or conservative? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farrell JJ, Fernández-del Castillo C. Pancreatic cystic neoplasms: management and unanswered questions. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1303–1315. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.01.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malleo G, Bassi C, Salvia R. Appraisal of the surgical management for pancreatic serous cystic neoplasms. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:2646–2647. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2783-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zanini N, Fantini L, Casadei R, Pezzilli R, Santini D, Calculli L, Minni F. Serous cystic tumors of the pancreas: when to observe and when to operate: a single-center experience. Dig Surg. 2008;25:233–239; discussion 240. doi: 10.1159/000142947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gabata T, Terayama N, Yamashiro M, Takamatsu S, Yoshida K, Matsui O, Usukura M, Takeshita M, Minato H. Solid serous cystadenoma of the pancreas: MR imaging with pathologic correlation. Abdom Imaging. 2005;30:605–609. doi: 10.1007/s00261-004-0286-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalb B, Sarmiento JM, Kooby DA, Adsay NV, Martin DR. MR imaging of cystic lesions of the pancreas. Radiographics. 2009;29:1749–1765. doi: 10.1148/rg.296095506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun HY, Kim SH, Kim MA, Lee JY, Han JK, Choi BI. CT imaging spectrum of pancreatic serous tumors: based on new pathologic classification. Eur J Radiol. 2010;75:e45–e55. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee SE, Kwon Y, Jang JY, Kim YH, Hwang DW, Kim MA, Kim SH, Kim SW. The morphological classification of a serous cystic tumor (SCT) of the pancreas and evaluation of the preoperative diagnostic accuracy of computed tomography. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:2089–2095. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-9959-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kucera JN, Kucera S, Perrin SD, Caracciolo JT, Schmulewitz N, Kedar RP. Cystic lesions of the pancreas: radiologic-endosonographic correlation. Radiographics. 2012;32:E283–E301. doi: 10.1148/rg.327125019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sahani DV, Kambadakone A, Macari M, Takahashi N, Chari S, Fernandez-del Castillo C. Diagnosis and management of cystic pancreatic lesions. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;200:343–354. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.8862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goh BK, Tan YM, Yap WM, Cheow PC, Chow PK, Chung YF, Wong WK, Ooi LL. Pancreatic serous oligocystic adenomas: clinicopathologic features and a comparison with serous microcystic adenomas and mucinous cystic neoplasms. World J Surg. 2006;30:1553–1559. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0749-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santos LD, Chow C, Henderson CJ, Blomberg DN, Merrett ND, Kennerson AR, Killingsworth MC. Serous oligocystic adenoma of the pancreas: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of three cases with ultrastructural findings. Pathology. 2002;34:148–156. doi: 10.1080/003130201201117963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee JH, Kim JK, Kim TH, Park MS, Yu JS, Choi JY, Kim JH, Kim YB, Kim KW. MRI features of serous oligocystic adenoma of the pancreas: differentiation from mucinous cystic neoplasm of the pancreas. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:571–576. doi: 10.1259/bjr/42007785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berland LL, Silverman SG, Gore RM, Mayo-Smith WW, Megibow AJ, Yee J, Brink JA, Baker ME, Federle MP, Foley WD, et al. Managing incidental findings on abdominal CT: white paper of the ACR incidental findings committee. J Am Coll Radiol. 2010;7:754–773. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2010.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi JY, Kim MJ, Lee JY, Lim JS, Chung JJ, Kim KW, Yoo HS. Typical and atypical manifestations of serous cystadenoma of the pancreas: imaging findings with pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:136–142. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Hayek KM, Brown N, O’Rourke C, Falk G, Morris-Stiff G, Walsh RM. Rate of growth of pancreatic serous cystadenoma as an indication for resection. Surgery. 2013;154:794–800; discussion 800-802. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fukasawa M, Maguchi H, Takahashi K, Katanuma A, Osanai M, Kurita A, Ichiya T, Tsuchiya T, Kin T. Clinical features and natural history of serous cystic neoplasm of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2010;10:695–701. doi: 10.1159/000320694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Machado MC, Machado MA. Solid serous adenoma of the pancreas: an uncommon but important entity. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:730–733. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stern JR, Frankel WL, Ellison EC, Bloomston M. Solid serous microcystic adenoma of the pancreas. World J Surg Oncol. 2007;5:26. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-5-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reese SA, Traverso LW, Jacobs TW, Longnecker DS. Solid serous adenoma of the pancreas: a rare variant within the family of pancreatic serous cystic neoplasms. Pancreas. 2006;33:96–99. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000226890.63451.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayashi K, Fujimitsu R, Ida M, Sakamoto K, Higashihara H, Hamada Y, Yoshimitsu K. CT differentiation of solid serous cystadenoma vs endocrine tumor of the pancreas. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:e203–e208. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.01.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pająk J, Liszka Ł, Mrowiec S, Zielińska-Pająk E, Gołka D, Lampe P. Serous neoplasms of the pancreas constitute a continuous spectrum of morphological patterns rather than distinct clinico-pathological variants. A study of 40 cases. Pol J Pathol. 2011;62:206–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsubayashi H, Uesaka K, Kanemoto H, Sugiura T, Mizuno T, Sasaki K, Ono H, Hruban R. Multiple endocrine neoplasms and serous cysts of the pancreas in a patient with von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2010;41:197–202. doi: 10.1007/s12029-010-9134-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blandamura S, Parenti A, Famengo B, Canesso A, Moschino P, Pasquali C, Pizzi S, Guzzardo V, Ninfo V. Three cases of pancreatic serous cystadenoma and endocrine tumour. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:278–282. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2006.036954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agarwal N, Kumar S, Dass J, Arora VK, Rathi V. Diffuse pancreatic serous cystadenoma associated with neuroendocrine carcinoma: a case report and review of literature. JOP. 2009;10:55–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mohan H, Garg S, Punia RP, Dalal A. Combined serous cystadenoma and pancreatic endocrine neoplasm. A case report with a brief review of the literature. JOP. 2007;8:453–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamaguchi H, Ishigami K, Inoue T, Eguchi T, Nagata S, Kuroda Y, Nishihara Y, Yamaguchi K, Tanaka M, Tsuneyoshi M. Three cases of serous oligocystic adenomas of the pancreas; evaluation of cyst wall thickness for preoperative differentiation from mucinous cystic neoplasms. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2007;38:52–58. doi: 10.1007/s12029-008-9017-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim SH, Lim JH, Lee WJ, Lim HK. Macrocystic pancreatic lesions: differentiation of benign from premalignant and malignant cysts by CT. Eur J Radiol. 2009;71:122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berman L, Mitchell KA, Israel G, Salem RR. Serous cystadenoma in communication with the pancreatic duct: an unusual radiologic and pathologic entity. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:e133–e135. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181d3458d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kobayashi T, Shimura T, Araki K, Mochida Y, Suzuki H, Suehiro T, Kuwano H. Macrocystic serous cystadenoma mimicking branch duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. Int Surg. 2009;94:176–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khashab MA, Kim K, Lennon AM, Shin EJ, Tignor AS, Amateau SK, Singh VK, Wolfgang CL, Hruban RH, Canto MI. Should we do EUS/FNA on patients with pancreatic cysts? The incremental diagnostic yield of EUS over CT/MRI for prediction of cystic neoplasms. Pancreas. 2013;42:717–721. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3182883a91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Del Chiaro M, Verbeke C, Salvia R, Klöppel G, Werner J, McKay C, Friess H, Manfredi R, Van Cutsem E, Löhr M, et al. European experts consensus statement on cystic tumours of the pancreas. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:703–711. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thornton GD, McPhail MJ, Nayagam S, Hewitt MJ, Vlavianos P, Monahan KJ. Endoscopic ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration for the diagnosis of pancreatic cystic neoplasms: a meta-analysis. Pancreatology. 2013;13:48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2012.11.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cizginer S, Turner BG, Bilge AR, Karaca C, Pitman MB, Brugge WR. Cyst fluid carcinoembryonic antigen is an accurate diagnostic marker of pancreatic mucinous cysts. Pancreas. 2011;40:1024–1028. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31821bd62f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bhutani MS, Gupta V, Guha S, Gheonea DI, Saftoiu A. Pancreatic cyst fluid analysis--a review. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2011;20:175–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sakorafas GH, Smyrniotis V, Reid-Lombardo KM, Sarr MG. Primary pancreatic cystic neoplasms revisited. Part I: serous cystic neoplasms. Surg Oncol. 2011;20:e84–e92. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adsay NV, Hasteh F, Cheng JD, Bejarano PA, Lauwers GY, Batts KP, Klöppel G, Klimstra DS. Lymphoepithelial cysts of the pancreas: a report of 12 cases and a review of the literature. Mod Pathol. 2002;15:492–501. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Adsay NV, Hasteh F, Cheng JD, Klimstra DS. Squamous-lined cysts of the pancreas: lymphoepithelial cysts, dermoid cysts (teratomas), and accessory-splenic epidermoid cysts. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2000;17:56–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yao X, Ji Y, Zeng M, Rao S, Yang B. Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: cross-sectional imaging and pathologic correlation. Pancreas. 2010;39:486–491. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181bd6839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sakorafas GH, Smyrniotis V, Reid-Lombardo KM, Sarr MG. Primary pancreatic cystic neoplasms of the pancreas revisited. Part IV: rare cystic neoplasms. Surg Oncol. 2012;21:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim SY, Park SH, Hong N, Kim JH, Hong SM. Primary solid pancreatic tumors: recent imaging findings updates with pathology correlation. Abdom Imaging. 2013;38:1091–1105. doi: 10.1007/s00261-013-0004-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hammond NA, Miller FH, Day K, Nikolaidis P. Imaging features of the less common pancreatic masses. Abdom Imaging. 2013;38:561–572. doi: 10.1007/s00261-012-9922-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Buerke B, Domagk D, Heindel W, Wessling J. Diagnostic and radiological management of cystic pancreatic lesions: important features for radiologists. Clin Radiol. 2012;67:727–737. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ellis CT, Barbour JR, Shary TM, Adams DB. Pancreatic cyst: pseudocyst or neoplasm? Pitfalls in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography diagnosis. Am Surg. 2010;76:725–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Takahashi N, Papachristou GI, Schmit GD, Chahal P, LeRoy AJ, Sarr MG, Vege SS, Mandrekar JN, Baron TH. CT findings of walled-off pancreatic necrosis (WOPN): differentiation from pseudocyst and prediction of outcome after endoscopic therapy. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:2522–2529. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-1039-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Panarelli NC, Park KJ, Hruban RH, Klimstra DS. Microcystic serous cystadenoma of the pancreas with subtotal cystic degeneration: another neoplastic mimic of pancreatic pseudocyst. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:726–731. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31824cf879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]