Abstract

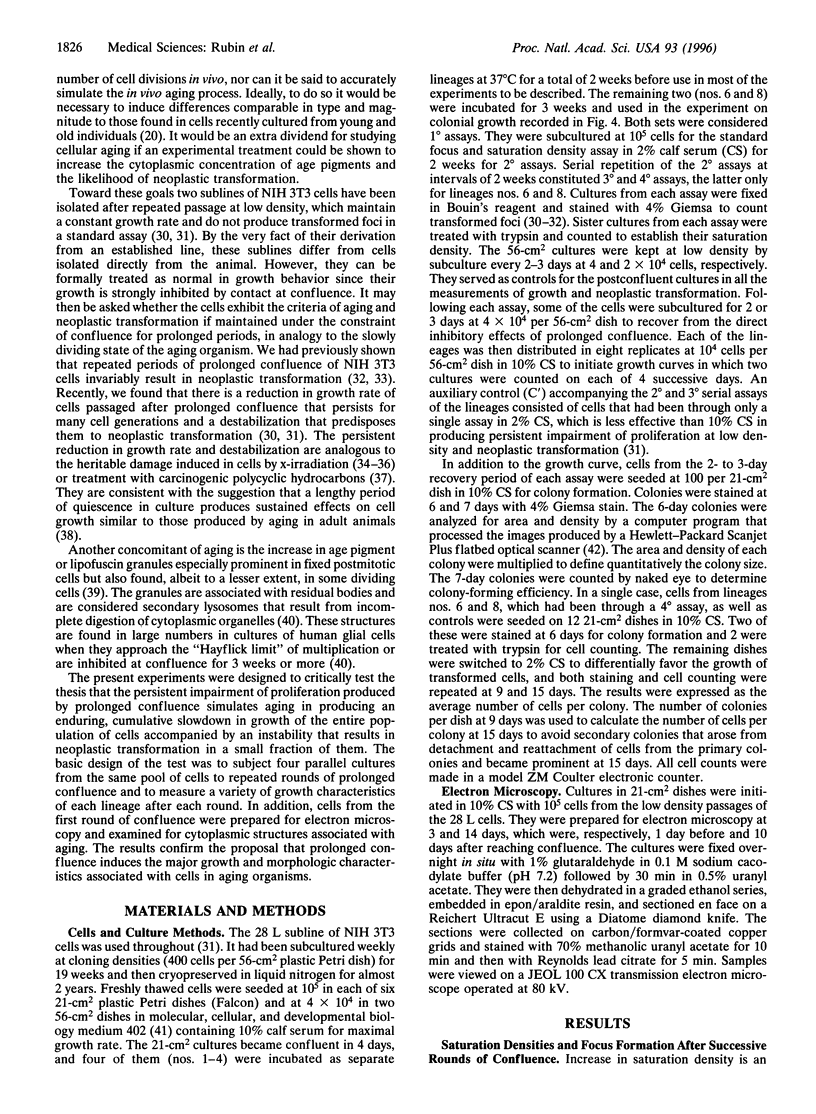

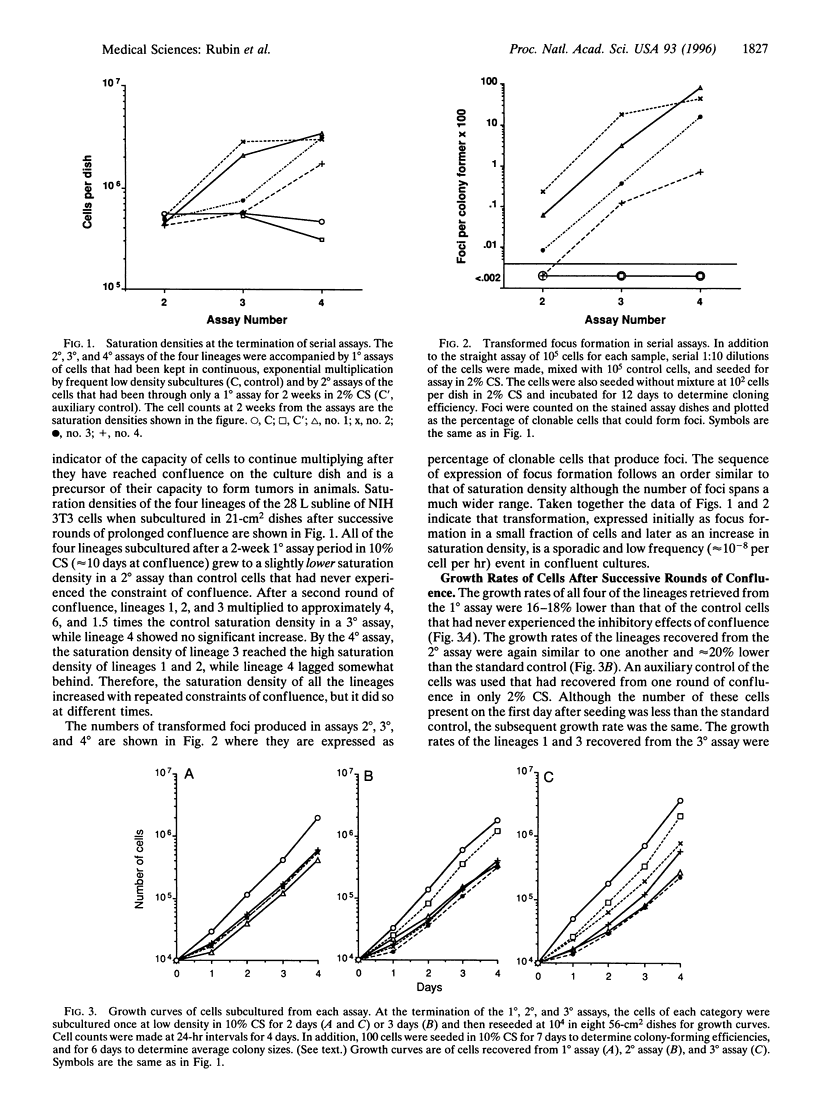

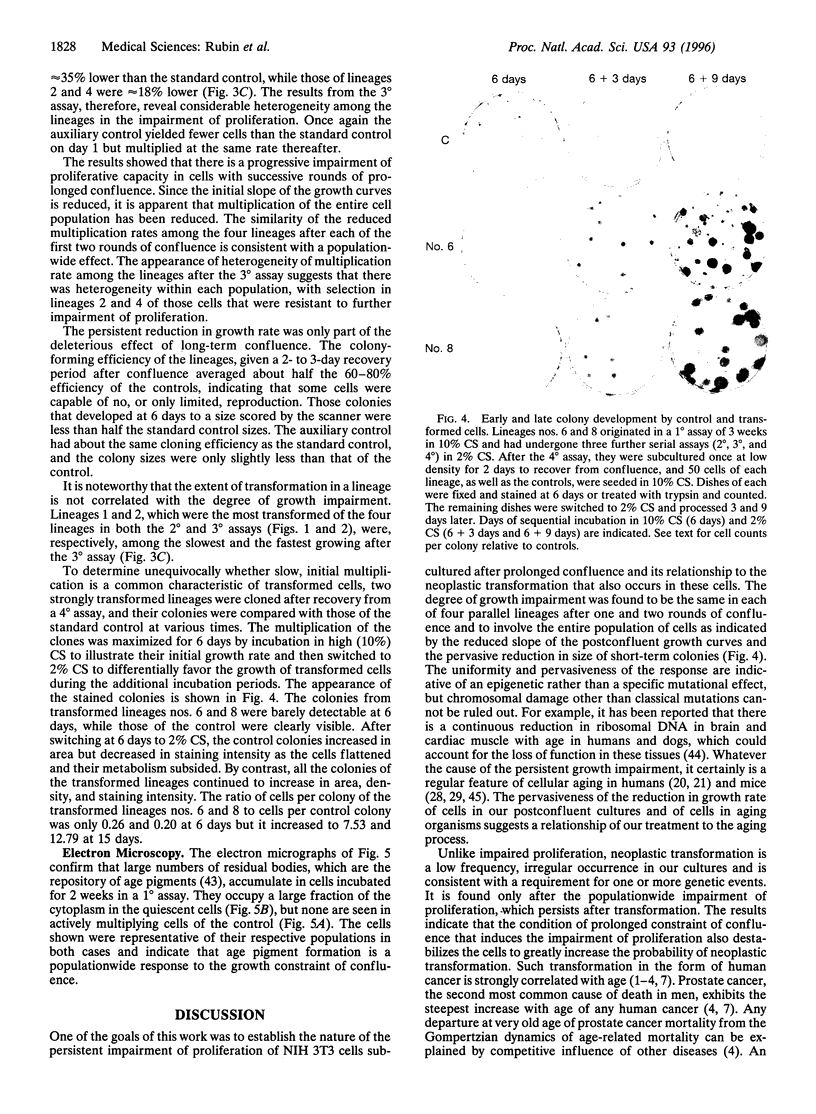

Three major characteristics of aging in animals are a slowdown of cell proliferation, an increase in residual bodies associated with age pigments, and a marked increase in the likelihood of neoplastic transformation. The 28 L subline of the NIH 3T3 line of mouse embryo fibroblasts exhibits all these characteristics when held at confluence for extended periods. The impairment of proliferation is the first behavioral characteristic detected in low density subcultures from the confluent cultures, and it persists through many cell generations of exponential multiplication. There is an equal degree of growth impairment among replicate cultures (lineages) recovered after each of 2 successive rounds of confluence, although heterogeneity appears after the third round. The growth impairment pervades the entire cell population of each lineage. The degree and duration of impairment increase with repeated rounds of confluence. A marked increase of residual bodies characteristic of age pigments occurs in the cytoplasm of all the cells kept under prolonged confluence. Neoplastic transformation first appears as foci of multilayered cells on a monolayered background of nontransformed cells. The transformed cells arise at different times in the lineages and originate from a very small fraction of the population. The transformed cells selectively overgrow the entire population in successive rounds of confluence leading to an increase in saturation density of each lineage at different times. Under cloning conditions, isolated colonies of transformed cells develop more slowly than colonies of nontransformed cells but eventually reach a higher population density. The regularity of persistent growth impairment among the lineages and the appearance of large numbers of residual bodies in all the cells of each population are more characteristic of an epigenetic process than of specific local mutations. although random chromosomal lesions cannot be ruled out. By contrast, the low frequency and stochastic character of neoplastic transformation are consistent with a conventional genetic origin. The advent in long-term confluent NIH 3T3 cultures of three cardinal characteristics of cellular aging in vivo recommends it as a model for aging cells.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- ARMITAGE P., DOLL R. The age distribution of cancer and a multi-stage theory of carcinogenesis. Br J Cancer. 1954 Mar;8(1):1–12. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1954.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aaronson S. A., Todaro G. J. Basis for the acquisition of malignant potential by mouse cells cultivated in vitro. Science. 1968 Nov 29;162(3857):1024–1026. doi: 10.1126/science.162.3857.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunk U., Ericsson J. L., Ponten J., Westermark B. Residual bodies and "aging" in cultured human glia cells. Effect of entrance into phase 3 and prolonged periods of confluence. Exp Cell Res. 1973 Apr;79(1):1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron I. L. Cell proliferation and renewal in aging mice. J Gerontol. 1972 Apr;27(2):162–172. doi: 10.1093/geronj/27.2.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron I. L. Minimum number of cell doublings in an epithelial cell population during the life-span of the mouse. J Gerontol. 1972 Apr;27(2):157–161. doi: 10.1093/geronj/27.2.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang W. P., Little J. B. Delayed reproductive death in X-irradiated Chinese hamster ovary cells. Int J Radiat Biol. 1991 Sep;60(3):483–496. doi: 10.1080/09553009114552331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clive J. M., Spencer R. P. Analysis of mortality rate from carcinoma of prostate. Mech Ageing Dev. 1995 Aug 31;83(1):31–41. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(95)01608-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley C., Curtis H. J. THE DEVELOPMENT OF SOMATIC MUTATIONS IN MICE WITH AGE. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1963 May;49(5):626–628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.49.5.626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis H. J., Leith J., Tilley J. Chromosome aberrations in liver cells of dogs of different ages. J Gerontol. 1966 Apr;21(2):268–270. doi: 10.1093/geronj/21.2.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebbesen P. Cancer and normal ageing. Mech Ageing Dev. 1984 Jun;25(3):269–283. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(84)90001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein S., Littlefield J. W., Soeldner J. S. Diabetes mellitus and aging: diminished planting efficiency of cultured human fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1969 Sep;64(1):155–160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.64.1.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay R. J., Menzies R. A., Morgan H. P., Strehler B. L. The division potential of cells in continuous growth as compared to cells subcultivated after maintenance in stationary phase. Exp Gerontol. 1968 Mar;3(1):35–44. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(68)90054-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D. T. Cytogenetical polymorphism and evolution in mammalian somatic cell populations in vivo and vitro. Nature. 1968 Feb 10;217(5128):518–523. doi: 10.1038/217518a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JACOBS P. A., BRUNTON M., COURT BROWN W. M., DOLL R., GOLDSTEIN H. Change of human chromosome count distribution with age: evidence for a sex differences. Nature. 1963 Mar 16;197:1080–1081. doi: 10.1038/1971080a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JONES H. B. Demographic consideration of the cancer problem. Trans N Y Acad Sci. 1956 Feb;18(4):298–333. doi: 10.1111/j.2164-0947.1956.tb00453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jainchill J. L., Aaronson S. A., Todaro G. J. Murine sarcoma and leukemia viruses: assay using clonal lines of contact-inhibited mouse cells. J Virol. 1969 Nov;4(5):549–553. doi: 10.1128/jvi.4.5.549-553.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn R. R. Aging and cell division. Science. 1975 Apr 18;188(4185):203–204. doi: 10.1126/science.188.4185.203-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisco H., Lisco E., Adelstein S. J., Banks H. H. Cytogenetic studies on blood lymphocytes of four patients with fracture of the femur injected with tritiated thymidine (3HTdR). Int J Radiat Biol Relat Stud Phys Chem Med. 1973 Jul;24(1):45–57. doi: 10.1080/09553007314550811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin G. M., Smith A. C., Ketterer D. J., Ogburn C. E., Disteche C. M. Increased chromosomal aberrations in first metaphases of cells isolated from the kidneys of aged mice. Isr J Med Sci. 1985 Mar;21(3):296–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin G. M., Sprague C. A., Epstein C. J. Replicative life-span of cultivated human cells. Effects of donor's age, tissue, and genotype. Lab Invest. 1970 Jul;23(1):86–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müntzing J., Nilsson T. Lipofuscin in malignant and non-malignant human prostatic tissue. Z Krebsforsch Klin Onkol Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1972;77(2):166–170. doi: 10.1007/BF00304055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pendergrass W. R., Li Y., Jiang D., Fei R. G., Wolf N. S. Caloric restriction: conservation of cellular replicative capacity in vitro accompanies life-span extension in mice. Exp Cell Res. 1995 Apr;217(2):309–316. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROTHFELS K. H., KUPELWIESER E. B., PARKER R. C. EFFECTS OF X-IRRADIATED FEEDER LAYERS ON MITOTIC ACTIVITY AND DEVELOPMENT OF ANEUPLOIDY IN MOUSE-EMBRYO CELLS IN VITRO. Proc Can Cancer Conf. 1963;5:191–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reznikoff C. A., Bertram J. S., Brankow D. W., Heidelberger C. Quantitative and qualitative studies of chemical transformation of cloned C3H mouse embryo cells sensitive to postconfluence inhibition of cell division. Cancer Res. 1973 Dec;33(12):3239–3249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs J. E. Longitudinal Gompertzian analysis of lung cancer mortality in the U.S., 1968-1986. Rising lung cancer mortality is the natural consequence of competitive deterministic mortality dynamics. Mech Ageing Dev. 1991 Jun 14;59(1-2):79–93. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(91)90075-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs J. E. Longitudinal Gompertzian analysis of prostate cancer mortality in the U.S., 1962-1987: a method of demonstrating relative environmental, genetic and competitive influences upon mortality. Mech Ageing Dev. 1991 Nov 1;60(3):243–253. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(91)90037-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowley J. D. Biological implications of consistent chromosome rearrangements in leukemia and lymphoma. Cancer Res. 1984 Aug;44(8):3159–3168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin H. Experimental control of neoplastic progression in cell populations: Foulds' rules revisited. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994 Jul 5;91(14):6619–6623. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin H., Xu K. Evidence for the progressive and adaptive nature of spontaneous transformation in the NIH 3T3 cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989 Mar;86(6):1860–1864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.6.1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin H., Yao A., Chow M. Heritable, population-wide damage to cells as the driving force of neoplastic transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995 May 23;92(11):4843–4847. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.4843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin H., Yao A., Chow M. Neoplastic development: paradoxical relation between impaired cell growth at low population density and excessive growth at high density. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995 Aug 15;92(17):7734–7738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SINCLAIR W. K. X-RAY-INDUCED HERITABLE DAMAGE (SMALL-COLONY FORMATION) IN CULTURED MAMMALIAN CELLS. Radiat Res. 1964 Apr;21:584–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider E. L., Mitsui Y. The relationship between in vitro cellular aging and in vivo human age. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1976 Oct;73(10):3584–3588. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.10.3584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipley G. D., Ham R. G. Improved medium and culture conditions for clonal growth with minimal serum protein and for enhanced serum-free survival of Swiss 3T3 cells. In Vitro. 1981 Aug;17(8):656–670. doi: 10.1007/BF02628401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. R., Pereira-Smith O. M., Schneider E. L. Colony size distributions as a measure of in vivo and in vitro aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978 Mar;75(3):1353–1356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.3.1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strehler B. L. Genetic instability as the primary cause of human aging. Exp Gerontol. 1986;21(4-5):283–319. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(86)90038-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summerhayes I. C., Franks L. M. Effects of donor age on neoplastic transformation of adult mouse bladder epithelium in vitro. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1979 Apr;62(4):1017–1023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TODARO G. J., GREEN H. Quantitative studies of the growth of mouse embryo cells in culture and their development into established lines. J Cell Biol. 1963 May;17:299–313. doi: 10.1083/jcb.17.2.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelstein B., Fearon E. R., Hamilton S. R., Kern S. E., Preisinger A. C., Leppert M., Nakamura Y., White R., Smits A. M., Bos J. L. Genetic alterations during colorectal-tumor development. N Engl J Med. 1988 Sep 1;319(9):525–532. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198809013190901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf N. S., Penn P. E., Jiang D., Fei R. G., Pendergrass W. R. Caloric restriction: conservation of in vivo cellular replicative capacity accompanies life-span extension in mice. Exp Cell Res. 1995 Apr;217(2):317–323. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao A., Rubin H. Automatic enumeration and characterization of heterogeneous clonal progression in cell transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993 Nov 15;90(22):10524–10528. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]