Abstract

The protective effect of ginsenoside Re, isolated from ginseng berry, against acute gastric mucosal lesions was examined in rats with a single intraperitoneal injection of compound 48/80 (C48/80). Ginsenoside Re (20 mg/kg or 100 mg/kg) was orally administered 0.5 h prior to C48/80 treatment. Ginsenoside Re dose-dependently prevented gastric mucosal lesion development 3 h after C48/80 treatment. Increases in the activities of myeloperoxidase (MPO; an index of neutrophil infiltration) and xanthine oxidase (XO) and the content of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS; an index of lipid peroxidation) and decreases in the contents of hexosamine (a marker of gastric mucus) and adherent mucus, which occurred in gastric mucosal tissues after C48/80 treatment, were significantly attenuated by ginsenoside Re. The elevation of Bax expression and the decrease in Bcl2 expression after C48/80 treatment were also attenuated by ginsenoside Re. Ginsenoside Re significantly attenuated all these changes 3 h after C48/80 treatment. These results indicate that orally administered ginsenoside Re protects against C48/80-induced acute gastric mucosal lesions in rats, possibly through its stimulatory action on gastric mucus synthesis and secretion, its inhibitory action on neutrophil infiltration, and enhanced lipid peroxidation in the gastric mucosal tissue.

Keywords: gastritis, ginsenoside Re, mucosa, Panax ginseng

1. Introduction

The root of ginseng (Panax ginseng Meyer) has been traditionally used for medicine and food. The primary physiologically-active substances of ginseng are ginsenosides, polyacetylenes, ginseng proteins, polysaccharides, and phenolic compounds. Ginsenosides in particular have been identified as the principal component of ginseng, displaying various biochemical and pharmacological properties. A number of researchers have studied the components of ginseng since the late 1960s, starting with the research of Shibata et al [1], whose research group identified the chemical structures of ginsenosides. Ginsenoside Re (C53H90O22) is the main ingredient of ginseng berries and roots. Notably, the amount of ginsenoside Re in the berries was four to six times more than that in the roots [2]. Research in the area has shown that ginsenoside Re exhibits multiple pharmacological activities via different mechanisms both in vivo and in vitro [3–8]. However, the pharmacological effects of ginsenoside Re on gastritis or gastric ulcer have not yet been studied.

A gastric ulcer is one of the most common diseases in the world, which affects approximately 5–10% of people during their lives. The therapy used to treat gastric ulcers includes control of acid secretion as well as the inflammation reversal to the mucosa. Korea red ginseng can assist in the eradication of Helicobacter pylori and alleviate H. pylori-induced halitosis [9]. A recent pharmacological investigation reports the antihistamine and anticytokine releasing effects of ginsenoside Re isolated from the berries of Panax ginseng [7].

For the common treatment of mild gastritis, antacids in liquid or tablet form are typically used. When antacids do not provide sufficient relief, H2 blocking medications, such as cimetidine, ranitidine, nizatidine, and famotidine, which help reduce the amount of acid are often prescribed [10]. Famotidine, the most potent H2 receptor antagonist, was used as a positive control [11].

The present study examined the protective effect of ginsenoside Re on acute gastric mucosal lesion progression in rats treated with compound 48/80 (C48/80). C48/80 causes degranulation of mast cells in connective tissue with the release of histamine from the cells, and causes the development of acute gastric mucosal lesions with neutrophils infiltrating into the gastric mucosal tissue [12,13]. Injecting C48/80 is consequently suggested as a good model for elucidating the mechanisms of clinical acute gastric lesions [14].

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sample preparation

Ginsenoside Re was prepared according to a previously reported method [7]. In brief, dried ginseng berries (5 kg) were ground to powder and extracted twice with 1 L of 95% ethyl alcohol for 2 h in a water bath (60°C). The extracts were concentrated by a vacuum evaporator (Eyela Co., Tokyo, Japan). The lyophilized extract was dissolved in distilled water, and was rinsed 10 times with diethyl ether to remove unnecessary compounds. The water fraction was suspended in distilled water and was adsorbed in a Diaion HP-20 (Mitsubishi Chemical Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) ion exchange resin column. A 30% MeOH fraction, 50% MeOH fraction, 70% MeOH fraction, and 100% MeOH fraction were eluted in the order named. The 30% MeOH fraction was then subjected to an octadecylsilyl (ODS) gel column by gradient elution with 30–100% MeOH, and resulted in four subfractions (F1–F4). The F3 subfraction was rechromatographed on a silica gel column with a mixture of the solvents (CHCl3:MeOH:H2O = 70:30:4 v/v), and ginsenoside Re was isolated and identified. The authenticity of ginsenoside Re was tested by spectroscopic methods including 1H-NMR, 13C-NMR, and fast atom bombardment-mass spectrometry (FAB-MS).

2.2. Animals and gastric mucosal lesion induction by C48/80

Male Wistar rats of 6 wk of age were purchased from Samtako (Osan, Korea) and housed in controlled temperature (23 ± 2°C), relative humidity (60 ± 5%), and 12 h light/dark cycle (7:00 am–7:00 pm) with free access to water. The experiment was reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Research Ethics Committee of the Semyung University, Jecheon, South Korea (smecae 08-12-03). Rats were divided into five groups (n = 8, respectively): normal (no gastric lesion and administered with distilled water), gastric lesion control (administered with distilled water), gastric lesion positive control (administered with famotidine 4 mg/kg; Nelson Korea Co., Seoul, Korea), and gastric lesion administered with two levels of ginsenoside Re (20 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg). The dosage of 20 mg/kg of ginsenoside Re was chosen from previous published data [15]. The 100 mg/kg dosage was determined to discover the maximum effects of ginsenoside Re. The animals were maintained with free access to rat chow, and famotidine and ginsenoside Re were orally administered with a stomach tube.

After 5 d of sample administration, C48/80 (0.75 mg/kg; Sigma-Aldrich Inc., NY, USA), dissolved in saline, was intraperitoneally injected into the rats fasted for 24 h. The normal group received a saline injection. The animals were sacrificed by decapitation under ether anesthesia 3 h after the C48/80 injection, and blood samples were obtained from the cervical wound.

2.3. Histological Periodic acid Schiff staining

The stomachs were removed, inflated with 10 mL of 0.9% NaCl, and put into 10% formalin for 10 min. The isolated stomachs were cut open along the greater curvature and washed in ice-cold saline. The parts of the mucosa were immediately fixed with 10% formalin solution, and routinely processed for embedding in paraffin wax. The sections were cut 5 μm thick and stained using the Periodic acid Schiff (PAS) method to observe mucus secretion [16].

2.4. Determinations of gastric mucosal adherent mucus and mucosal hexosamine

The measurement of gastric mucosal adherent mucus was assayed using alcian blue staining [17]. In brief, the parts of the stomach mucosa were rinsed with ice-cold 0.25M sucrose. A 50 mm2 (approximately 8 mm-diameter) portion of the glandular region of the stomach was excised with a scalpel, and soaked in 0.1% alcian blue dissolved in 0.16M of sucrose buffered with 0.05M sodium acetate (pH 5.8) for 2 h. The unbound dye was removed using two successive washes with 0.25M sucrose. The dye complex with mucus was extracted using 30% docusate sodium salt (Sigma-Aldrich Inc., NY, USA) for 2 h. After centrifugation at 2,060× g for 10 min, the optimal density of the alcian blue solution was measured at 620 nm, and calculated using the calibration curve. The adherent gastric mucosal mucus was expressed as the percentage of the alcian blue adhering to the gastric mucosal surface of the gastric lesion control group.

The measurement of gastric mucosal hexosamine has been used as another indicator of gastric mucus secretion, and was assayed by the method of Neuhaus and Letzring [18]. In brief, gastric mucosal mucin was extracted with Triton X-100 (Sigma Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) and then hydrolyzed with hydrochloric acid. Hexosamine obtained from the hydrolyzed mucin was assayed using acetylacetone and Ehrlich's reagent.

2.5. Gastric mucosal enzymes and components

The parts of the gastric mucosal tissue were homogenized and centrifuged for 10 min at 9,000× g and the supernatant was used for malondialdehyde (MDA), myeloperoxidase (MPO), and xanthine oxidase (XO) analyses. MDA levels of gastric mucosa were determined by the thiobarbituric acid reactive substance (TBARS) colorimetric assay (Synergy2; BioTek Co., USA). Gastric mucosal MPO activity was used to examine the degree of neutrophil infiltration and inflammation. MPO activity was assayed by the method of Suzuki et al [19], measuring the H2O2-dependent oxidation of tetramethylbenzidine at 37°C. Gastric mucosal XO was assayed according to the method of Hashimoto [20] by measuring the increase in absorbance at 292 nm following the formation of uric acid at 30°C.

2.6. Immunofluorescence analysis

The sections were cut 5 μm thick and mounted on glass slides. The immunofluorescence analysis was performed with mouse monoclonal anti-Bax antibody and rabbit monoclonal anti-Bcl2 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA) and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated antimouse and antirabbit IgG antibodies, respectively (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, USA). The nuclei were counterstained with 1 μg/mL propidium iodide (PI; Sigma Chemical Co.). The fluorescence images were taken with a laser confocal microscope (Fluoview FV1000; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The optical density was measured using Bio1d software (Vilber Lourmat, Marne-la-Vallée Cedex, France).

2.7. Laser microdissection and protein extraction

For laser microdissection (LMD), a 10-μm thick section prepared from the same tissue block was attached onto provided slides (Jungwoo F&B Co., Bucheon, Republic of Korea). Sixteen fragments of gastric tissues were collected in a 0.5-mL tube cap using an ION LMD (Jungwoo F&B Co.). Protein extraction was performed as previously described [21]. Briefly, the tissue fragments were deparaffinized and boiled at 100°C in Tris–HCl buffer solutions of pH 8 containing 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). Protein concentrations were measured using a DC Protein Assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Five μL of standards and protein samples were transferred to a 96-well plate and 25 μL of alkaline copper tartrate solution containing Reagent S was added to each well. Then 200 μL of dilute Folin Reagent was added to each well and the 96-well plate was incubated at room temperature. After 15 min, the protein concentrations were measured at 750 nm using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reader (Synergy2; Biotek, Winooski, VT, USA).

2.8. Western blotting analysis

Each protein was denatured with 5× sample buffer and boiled for 5 min. Each protein was then fractionated by electrophoresis through a 10% SDS polyacrylamide gel at 100 V for 2 h, and the proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes at 100 V for 60 min. Each membrane was blocked with TBST buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20) containing 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h and then incubated with primary antibodies (mouse anti-Bax and rabbit anti-Bcl2 antibodies) in TBST buffer containing 1% BSA at 4°C overnight. The membranes were washed three times with TBST buffer and further incubated with antimouse and anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase for 2 h, respectively. Each membrane was filmed with a chemiluminescent imaging system (Fusion SL2; Vilber Lourmat), and analyzed using Bio1d software (Vilber Lourmat).

2.9. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Duncan's multiple range tests. A p value <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. For all analyses, a commercially available statistical package software was used (SPSS version 19; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Effects of ginsenoside Re on gastric mucosal lesion development

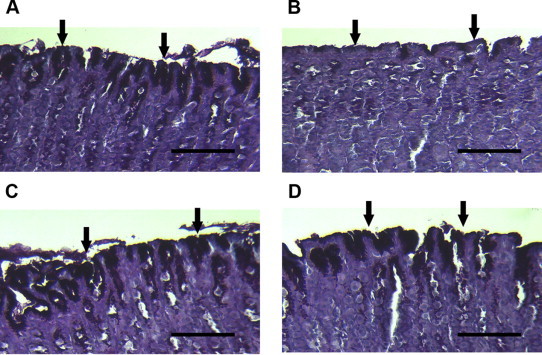

The degree of mucosal damage was examined by histological examination with PAS. The mucus secretion was quantified with alcian blue and hexosamine methods. PAS staining results are shown in Fig. 1. The apical surface of the mucous cells in normal rats was strongly stained with PAS (arrows in Fig. 1A) indicating intact gastric mucosa layer. However, PAS reaction was significantly reduced in surface cells of the control group (arrows in Fig. 1B) showing diffusive erosion of the gastric mucosal cell layer in these rats. PAS reaction increased in famotidine (arrows in Fig. 1C)- and ginsenoside Re (arrows in Fig. 1D)-treated rats compared with the control group, suggesting an increase in mucus secretion and alleviation of the erosion in the gastric mucosal cell layer in these groups.

Fig. 1.

Histological analysis of gastric mucosa of rat stained with PAS. (A) Normal group: surface mucous cells (arrows) were strongly stained with PAS. (B) Gastric lesion control group: the PAS reaction was reduced in surface cells (arrows). (C) Gastric lesion positive control group (famotidine, 4 mg/kg): the PAS reaction remained in surface cells (arrows). (D) Gastric lesion treated with ginsenoside Re (100 mg/kg): the PAS reaction remained in surface cells (arrows). Scale bars = 100 μm. PAS, Periodic acid Schiff.

A significant decrease in adherent gastric mucus content was seen in C48/80-induced gastric lesion control rats compared with normal rats (Table 1). Pre-administration with famotidine and ginsenoside Re significantly attenuated the decrease in adherent gastric mucus content. The effects of ginsenoside Re exhibited dose dependency. Gastric mucosal hexosamine is the best indicator of mucin production, which is the first line of gastric mucosal defense. A significant decrease in mucosal hexosamine content, like in the adherent gastric mucus, was seen in C48/80-induced gastric lesion control rats compared with normal rats (Table 1). Pre-administration with famotidine and ginsenoside Re significantly attenuated the decrease in mucosal hexosamine content. These effects of ginsenoside Re exhibited dose dependency.

Table 1.

Effects of Ginsenoside Re on Adherent Gastric Mucus and Mucosal Hexosamine Content

| Group | Adherent gastric mucus (% alcian blue/g tissue) | Mucosal hexosamine (mg/g tissue) |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | 100.0 ± 4.7** | 3.5 ± 0.1** |

| Control | 38.2 ± 5.0* | 1.6 ± 0.2* |

| Famotidine1) | 68.5 ± 12.3*,** | 2.5 ± 0.4*,** |

| Re 202) | 59.5 ± 8.0*,** | 2.0 ± 0.2*,** |

| Re 1003) | 64.6 ± 9.2*,** | 2.4 ± 0.3*,** |

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD; n = 10).

* p < 0.05 vs. normal.

** p < 0.05 vs. control.

Famotidine: positive control (4 mg/kg).

Re 20: ginsenoside Re treated at 20 mg/kg.

Re 100: ginsenoside Re treated at 100 mg/kg.

3.2. Effects of ginsenoside Re on gastric mucosal lesion development

Gastric mucosal MDA content, MPO, and XO activities significantly increased in C48/80-treated control rats compared to those of the normal group (Table 2). The MDA content, MPO, and XO activities in the C48/80-treated control group were 3.6, 2.3, and 1.4 times higher, respectively, than those in the normal group. Pre-administered ginsenoside Re significantly attenuated these parameters.

Table 2.

Effects of Ginsenoside Re on Gastric Mucosal MDA Contents and MPO and XO Activities

| Group | MDA (μM/mg) | MPO (%) | XO (μU/mg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 1.1 ± 0.3** | 100.0 ± 9.9** | 148.9 ± 24.9** |

| Control | 4.0 ± 0.8* | 144.9 ± 9.0* | 340.2 ± 11.7* |

| Famotidine1) | 1.5 ± 0.3** | 113.3 ± 7.3*,** | 251.6 ± 18.7*,** |

| Re 202) | 2.8 ± 0.5*,** | 135.1 ± 10.4* | 170.9 ± 20.9** |

| Re 1003) | 1.8 ± 0.3*,** | 116.2 ± 8.1*,** | 231.0 ± 22.4*,** |

Data expressed as mean ± SD (n = 10).

* p < 0.05 vs. normal.

** p < 0.05 vs. control.

MDA, malondialdehyde; MPO, myeloperoxidase; SD, standard deviation; XO, xanthine oxidase.

Famotidine: positive control (4 mg/kg).

Re 20: ginsenoside Re treated at 20 mg/kg.

Re 100: ginsenoside Re treated at 100 mg/kg.

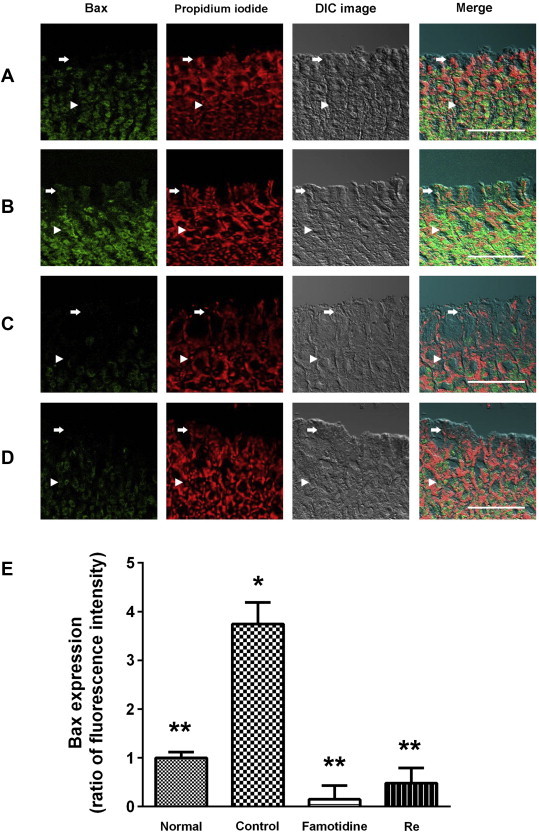

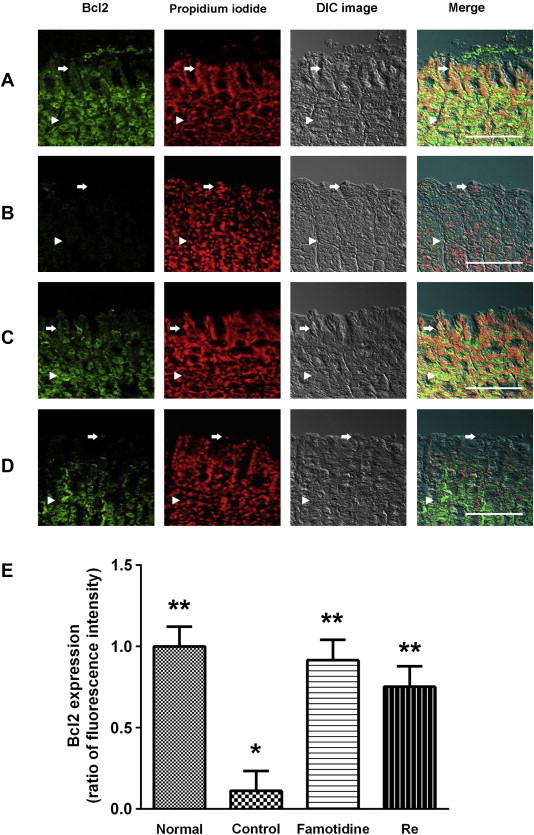

3.3. Bax and Bcl2 expressions in mucosa

Immunofluorescence staining clearly showed that Bax was expressed and limited to the cytosol of the gastric mucosal cells (Fig. 2). Bax positive cells were found predominantly in part of the gastric gland (arrow in Fig. 2B). The Bax staining in submucosa and muscularis externa was very strong (arrowhead in Fig. 2B). Bax staining decreased in famotidine (positive control, arrow in Fig. 2C)- and ginsenoside Re (arrow in Fig. 2D)-treated rats compared with the control group suggesting the alleviation of apoptotic damage in the gastric mucosal cell layer in these groups. By contrast, Bcl2 positive cells were found predominantly in part of the normal gastric gland (arrow in Fig. 3A). Bcl2 staining in submucosa and muscularis externa was extremely strong in the normal group (arrowhead in Fig. 3A). Bcl2 staining became weak in both gastric mucosa and submucosa in the control group (arrow and arrowhead in Fig. 3B). Famotidine and ginsenoside Re attenuated the diminishment of the Bcl2 staining in both gastric mucosa and submucosa (arrow and arrowhead in Fig. 3C and D).

Fig. 2.

Immunofluorescence analysis of Bax in the gastric mucosa of rats. The Bax positive cells were probed with anti-Bax monoclonal antibody in rat gastric mucosa (green color). Nuclear counterstaining was performed with propidium iodide (PI). (A) Normal group: Bax staining of surface mucous cells (arrows) showed up faintly. (B) Gastric lesion control group: Bax staining of surface mucous cells (arrows) showed up brightly. (C) Gastric lesion positive control group (famotidine, 4 mg/kg): Bax staining of surface mucous cells (arrows) was diminished. The Bax staining of submucosa and muscularis externa (arrowheads) was identical to that carried out on the mucosa. (D) Gastric lesion treated with ginsenoside Re (100 mg/kg): Bax staining of surface mucous cells (arrows) was diminished. The Bax staining of submucosa and muscularis externa (arrowheads) was identical to that carried out on the mucosa. Scale bars = 100 μm. * p < 0.05 vs. normal. ** p < 0.05 vs. control. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 3.

Immunofluorescence analysis of Bcl2 in the gastric mucosa of rats. The Bcl2 positive cells were probed with anti-Bcl2 monoclonal antibody in rat gastric mucosa (green color). Nuclear counterstaining was performed with propidium iodide (PI). (A) Normal group: Bcl2 staining of surface mucous cells (arrows) showed up brightly. (B) Gastric lesion control group: Bcl2 staining of surface mucous cells (arrows) showed up faintly. (C) Gastric lesion positive control group (famotidine, 4 mg/kg): Bcl2 staining of surface mucous cells (arrows) was brightened. The Bcl2 staining of submucosa and muscularis externa (arrowheads) was identical to that carried out on the mucosa. (D) Gastric lesion treated with ginsenoside Re (100 mg/kg): Bcl2 staining of surface mucous cells (arrows) was brightened. The Bcl2 staining of submucosa and muscularis externa (arrowheads) was identical to that carried out on the mucosa. Scale bars = 100 μm. * p < 0.05 vs. normal. ** p < 0.05 vs. control. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

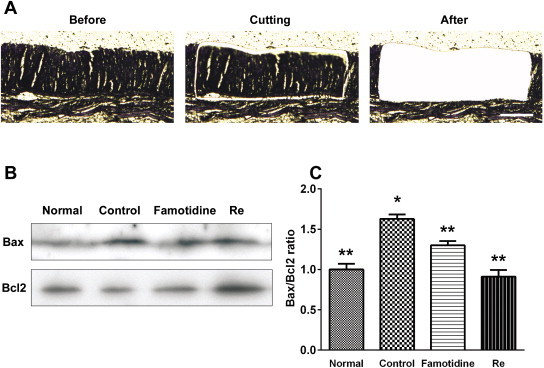

3.4. Bax and Bcl2 western blotting in mucosa

Parts of the gastric gland, submucosa, and muscularis externa were microdissected (Fig. 4A) and the proteins were extracted. Bax protein increased in the C48/80-treated control and decreased in the famotidine- and ginsenoside Re-treated groups. By contrast, Bcl2 protein decreased in the C48/80-treated control and increased in the famotidine- and ginsenoside Re-treated groups (Fig. 4B). The ratio of Bax and Bcl2 significantly increased in the C48/80-treated control group compared with the normal group (Fig. 4C, p < 0.05). The famotidine- and ginsenoside Re-treated groups showed significantly decreased Bax/Bcl2 ratios compared with the C48/80-treated control (p < 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Representative results of Western blotting of Bax and Bcl2. The cells of interest were identified with (A, Prior to) laser microdissection, (A, Cutting) cut away with a near-IR laser, and (A, After) dropped away from the tissue. (B) Western blotting shows changes in the expression levels of Bax and Bcl2 in the microdissected gastric tissue. (C) A histogram of relative changes in the expression levels of the two proteins in the gastric tissues as determined by densitometric analysis. Scale bars = 200 μm. * p < 0.05 vs. normal. ** p < 0.05 vs. control.

4. Discussion

Ginsenoside Re showed multiple pharmacological activities including antidiabetic [3], antiobese [4], antioxidant, anticancer [22], memory-enhancing [23], and anti-inflammatory effects [24], and inhibitory activities on histamine release [7]. Histamine is an organic nitrogen compound involved in regulating physiological function in the digestive system and local immune responses. There are four types of histamine receptors (H1–H4). Among them, the H2 receptor antagonists are used in the treatment of peptic ulcer disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and dyspepsia, as well as in the prevention of stress ulcers [25]. Famotidine, an H2 receptor antagonist with a thiazole nucleus, is approximately 7.5 times more potent than ranitidine and 20 times more potent than cimetidine on an equimolar basis [11]. Famotidine was, therefore, used as a positive control in the present study.

Among the variety of biological activities of ginsenoside Re reported in vitro and in animal models, we have noticed the antihistamine and anti-inflammatory activities [7]. In this study, we attempted to examine the effect of ginsenoside Re on acute gastric lesion progression induced by C48/80. The C48/80 promotes histamine release [26] and causes acute gastric mucosal lesions. The model of acute gastric mucosal lesions in rats treated once with C48/80 has been thought to be important for clarifying the roles of oxidative stress and inflammation in the pathogenesis of gastritis in humans [27].

The results of the present study have clearly shown that ginsenoside Re administered orally to C48/80-treated rats protects gastric mucosal lesion progression, and its potency is similar to famotidine. Pre-administration of ginsenoside Re ameliorated gastric mucosal damage, mucus secretion, MDA content, MPO, and XO activities. Mucus secretion is a crucial factor in the protection of gastric mucosa from gastric lesions and has been regarded as an important defensive factor in the gastric mucus barrier. A decrease in the synthesis of mucus has been implicated in the etiology of gastric ulcers [28]. The mucus layer protects the newly formed cells against the damage caused by acidic pH and the proteolytic potential of gastric secretions [29].

The wide distribution of adherent mucus content in the gastrointestinal tract plays a pivotal role in cytoprotection and repair of the gastric mucosa [30]. The results showed that severity of erosion induced by C48/80 treatment was alleviated by ginsenoside Re administration, and gastric mucosal damage and mucus secretion assessed by alcian blue staining and gastric mucosal hexosamine were dose-dependently improved by ginsenoside Re administration.

Ohta et al [14] suggested that neutrophil infiltration plays a critical role in C48/80-induced acute gastric mucosal lesion formation and progression. In the present study, ginsenoside Re normalized the increased gastric mucosal neutrophil infiltration assessed by MPO activity. The level of MPO activity is directly proportional to numbers of neutrophils, and Krawisz et al [31] suggested that MPO activity can be used to quantitate inflammation. Therefore, the results of the present study suggest the suppressive effect on neutrophil infiltration and anti-inflammatory action of ginsenoside Re.

It has been shown that changes in gastric mucosal reactive oxygen species (ROS) and neutrophil infiltration into gastric mucosal tissues are closely related to the development of gastric mucosal lesions in rats with a single C48/80 treatment [27]. XO generates ROS during the oxidation of hypoxanthine or xanthine [32], and Ohta et al [33] suggested that the xanthine–XO system in the gastric mucosal tissue participates in the progression of gastric mucosal lesion. In the present study, increased MPO activity—an index of neutrophil infiltration—of the gastric lesion control group was reduced, and ROS-related parameters such as MDA content and XO activity were normalized by ginsenoside Re administration. From the present study, it seems likely that administration of ginsenoside Re exerts a preventive effect on the progression of C48/80-induced acute gastric mucosal lesions by protecting the gastric mucosal barrier and tissue against the attack of ROS derived from infiltrated neutrophils and the xanthine–XO system through preservation of gastric mucus.

The protein encoded by the Bcl2 gene is a regulator of programmed cell death and apoptosis. The cell survival-promoting activity of this protein is contrary to the cell death-promoting activity of Bax, a homologous protein that forms heterodimers with Bcl2 and accelerates rates of cell death [34]. The expression of Bax is upregulated by the response of the cell to stress [35]. Bax protein significantly increased 3 h after hypoxic–ischemic brain injury in neonatal brain tissue [36] and it increased in gastric mucosa after ischemia–reperfusion damage [37]. In the present results, the predominant increase of Bax expression was discovered after C48/80-induced acute gastritis. We have observed that the increased Bax expression by C48/80 treatment was attenuated when ginsenoside Re was administered. In contrast to Bax, Bcl2 expression decreased after C48/80 induced acute gastritis and ginsenoside Re attenuated the diminution. In Western blotting analysis, the Bax/Bcl2 ratio result also confirmed the protective effects of ginsenoside Re on C48/80-induced acute gastritis.

In conclusion, the results of the present study indicate that ginsenoside Re exerts a preventive effect on the progression of C48/80-induced acute gastric mucosal lesion in rats, possibly by inducing mucus secretion and attenuating enhanced neutrophil infiltration, inflammation, and oxidative stress in gastric mucosa.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the program of the Kyung Hee University (Seoul, South Korea) for the young medical researcher in 2008 (KHU-20081252).

Footnotes

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Contributor Information

Kang Hyun Leem, Email: lkh@semyung.ac.kr.

Youn-Jung Kim, Email: yj129@khu.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Shibata S., Tanaka O., Ando T., Sado M., Tsushima S., Ohsawa T. Chemical studies on oriental plant drugs. XIV. Protopanaxadiol, a genuine sapogenin of ginseng saponins. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1966;14:595–600. doi: 10.1248/cpb.14.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim Y.K., Yoo D.S., Xu H., Park N.I., Kim H.H., Choi J.E., Park S.U. Ginsenoside content of berries and roots of three typical Korean ginseng (Panax ginseng) cultivars. Nat Prod Commun. 2009;4:903–906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Attele A.S., Zhou Y.P., Xie J.T., Wu J.A., Zhang L., Dey L., Pugh W., Rue P.A., Polonsky K.S., Yuan C.S. Antidiabetic effects of Panax ginseng berry extract and the identification of an effective component. Diabetes. 2002;51:1851–1858. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.6.1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xie J.T., Mehendale S.R., Li X., Quigg R., Wang X., Wang C.Z., Wu J.A., Aung H.H., Rue P.A., Bell G.I. Anti-diabetic effect of ginsenoside Re in ob/ob mice. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1740:319–325. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang C.Y., Wang J., Zhao Y., Shen L., Jiang X., Xie Z.G., Liang N., Zhang L., Chen Z.H. Anti-diabetic effects of Panax notoginseng saponins and its major anti-hyperglycemic components. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;130:231–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee O.H., Lee H.H., Kim J.H., Lee B.Y. Effect of ginsenosides Rg3 and Re on glucose transport in mature 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Phytother Res. 2011;25:768–773. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bae H.M., Cho O.S., Kim S.J., Im B.O., Cho S.H., Lee S., Kim M.G., Kim K.T., Leem K.H., Ko S.K. Inhibitory effects of ginsenoside re isolated from ginseng berry on histamine and cytokine release in human mast cells and human alveolar epithelial cells. J Ginseng Res. 2012;36:369–374. doi: 10.5142/jgr.2012.36.4.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Y.W., Zhu X., Li W., Lu Q., Wang J.Y., Wei Y.Q., Yin X.X. Ginsenoside Re attenuates diabetes-associated cognitive deficits in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2012;101:93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee J.S., Kwon K.A., Jung H.S., Kim J.H., Hahm K.B. Korea red ginseng on Helicobacter pylori-induced halitosis: newer therapeutic strategy and a plausible mechanism. Digestion. 2009;80:192–199. doi: 10.1159/000229997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zajac P., Holbrook A., Super M.E., Vogt M. An overview: current clinical guidelines for the evaluation, diagnosis, treatment, and management of dyspepsia. Osteopathic Family Physician. 2013;5:79–85. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berardi R.R., Tankanow R.M., Nostrant T.T. Comparison of famotidine with cimetidine and ranitidine. Clin Pharm. 1988;7:271–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takeuchi K., Ohtsuki H., Okabe S. Pathogenesis of compound 48/80-induced gastric lesions in rats. Dig Dis Sci. 1986;31:392–400. doi: 10.1007/BF01311675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takeuchi K., Ohtsuki H., Nobuhara Y., Okabe S. Mechanisms of irritative activity of compound 48/80 on rat gastric mucosa. Digestion. 1986;33:34–44. doi: 10.1159/000199272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohta Y., Kobayashi T., Hayashi T., Inui K., Yoshino J., Nakazawa S. Preventive effect of Shigyaku-san on progression of acute gastric mucosal lesions induced by compound 48/80, a mast cell degranulator, in rats. Phytother Res. 2006;20:256–262. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen L.M., Zhou X.M., Cao Y.L., Hu W.X. Neuroprotection of ginsenoside Re in cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 2008;10:439–445. doi: 10.1080/10286020801892292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vacca L.L. Raven Press; New York: 1985. Laboratory manual of histochemistry. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kitagawa H., Takeda F., Kohei H. A simple method for estimation of gastric mucus and effects of antiulcerogenic agents on the decrease in mucus during water-immersion stress in rats. Arzneimittelforschung. 1986;36:1240–1244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neuhaus O.W., Letzring M. Determination of hexosamines in conjunction with electrophoresis on starch. Anal Chem. 1957;29:1230–1233. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suzuki K., Ota H., Sasagawa S., Sakatani T., Fujikura T. Assay method for myeloperoxidase in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Anal Biochem. 1983;132:345–352. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hashimoto S. A new spectrophotometric assay method of xanthine oxidase in crude tissue homogenate. Anal Biochem. 1974;62:426–435. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(74)90175-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi S.R., Liu C., Balgley B.M., Lee C., Taylor C.R. Protein extraction from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections: quality evaluation by mass spectrometry. J Histochem Cytochem. 2006;54:739–743. doi: 10.1369/jhc.5B6851.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamabe N., Kim Y.J., Lee S., Cho E.J., Park S.H., Ham J., Kim H.Y., Kang K.S. Increase in antioxidant and anticancer effects of ginsenoside Re-lysine mixture by Maillard reaction. Food Chem. 2013;138:876–883. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi J., Xue W., Zhao W.J., Li K.X. Pharmacokinetics and dopamine/acetylcholine releasing effects of ginsenoside Re in hippocampus and mPFC of freely moving rats. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2013;34:214–220. doi: 10.1038/aps.2012.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee K.W., Jung S.Y., Choi S.M., Yang E.J. Effects of ginsenoside Re on LPS-induced inflammatory mediators in BV2 microglial cells. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012;12:196. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-12-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marieb E.N. 5th ed. Benjamin Cummings; San Francisco: 2001. Human anatomy and physiology. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rothschild A.M. Mechanisms of histamine release by compound 48-80. Br J Pharmacol. 1970;38:253–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1970.tb10354.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohta Y., Kobayashi T., Nishida K., Ishiguro I. Relationship between changes of active oxygen metabolism and blood flow and formation, progression, and recovery of lesions is gastric mucosa of rats with a single treatment of compound 48/80, a mast cell degranulator. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:1221–1232. doi: 10.1023/a:1018854107623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Younan F., Pearson J., Allen A., Venables C. Changes in the structure of the mucous gel on the mucosal surface of the stomach in association with peptic ulcer disease. Gastroenterology. 1982;82:827–831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tarnawski A., Szabo I.L., Husain S.S., Soreghan B. Regeneration of gastric mucosa during ulcer healing is triggered by growth factors and signal transduction pathways. J Physiol Paris. 2001;95:337–344. doi: 10.1016/s0928-4257(01)00046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanyal A.K., Mitra P.K., Goel R.K. A modified method to estimate dissolved mucosubstances in gastric juice. Indian J Exp Biol. 1983;21:78–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krawisz J.E., Sharon P., Stenson W.F. Quantitative assay for acute intestinal inflammation based on myeloperoxidase activity. Assessment of inflammation in rat and hamster models. Gastroenterology. 1984;87:1344–1350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Follin P., Dahlgren C. Altered O2-/H2O2 production ratio by in vitro and in vivo primed human neutrophils. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;167:970–976. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)90618-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohta Y., Kobayashi T., Ishiguro I. Participation of xanthine-xanthine oxidase system and neutrophils in development of acute gastric mucosal lesions in rats with a single treatment of compound 48/80, a mast cell degranulator. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:1865–1874. doi: 10.1023/a:1018803025043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qiao W.L., Wang G.M., Shi Y., Wu J.X., Qi Y.J., Zhang J.F., Sun H., Yan C.D. Differential expression of Bcl-2 and Bax during gastric ischemia-reperfusion of rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1718–1724. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i13.1718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miyashita T., Reed J.C. Tumor suppressor p53 is a direct transcriptional activator of the human bax gene. Cell. 1995;80:293–299. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90412-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Northington F.J., Ferriero D.M., Flock D.L., Martin L.J. Delayed neurodegeneration in neonatal rat thalamus after hypoxia-ischemia is apoptosis. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1931–1938. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-06-01931.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krajewski S., Krajewska M., Shabaik A., Miyashita T., Wang H.G., Reed J.C. Immunohistochemical determination of in vivo distribution of Bax, a dominant inhibitor of Bcl-2. Am J Pathol. 1994;145:1323–1336. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]