Abstract

Leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein-coupled receptor 5 (Lgr5) is expressed in many organs, including female reproductive organs, and is a stem cell marker in the stomach and intestinal epithelium, hair follicles, and ovarian surface epithelium. Despite ongoing studies, the definitive physiological functions of Lgr5 remain unclear. We utilized mice with conditional deletion of Lgr5 (Lgr5d/d) in the female reproductive organs by progesterone receptor-Cre (PgrCre) to determine Lgr5's functions during pregnancy. Only 30% of plugged Lgr5d/d females delivered live pups, and their litter sizes were lower. We found that pregnancy failure in Lgr5d/d females was due to insufficient ovarian progesterone (P4) secretion that compromised decidualization, terminating pregnancy. The drop in P4 levels was reflected in elevated levels of P4-metabolizing enzyme 20α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase in corpora lutea (CL) inactivated of Lgr5. Of interest, P4 supplementation rescued decidualization failure and supported pregnancy to full term in Lgr5d/d females. These results provide strong evidence that Lgr5 is critical to normal CL function, unveiling a new role of LGR5 in the ovary.—Sun, X., Terakawa, J., Clevers, H., Barker, N., Daikoku, T., Dey, S. K. Ovarian LGR5 is critical for successful pregnancy.

Keywords: 20α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, corpus luteum, progesterone

Leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein-coupled receptor-5 (LGR5) is expressed in numerous tissues, including muscle, placenta, spinal cord, and the brain (1), and is structurally similar to other family members, LGR4 and LGR6 (1, 2). LGR5 has been identified as a stem cell marker in intestinal and stomach epithelia, as well as hair follicles (3–5). More recently, Lgr5 was shown to be expressed by ovarian surface epithelial stem cells (6). Although LGR5's identity as a stem cell marker is overwhelming, knowledge regarding its physiological functions is limited. LGR5 had been an orphan receptor until recent discoveries showing that R-spondin 1–4 (RSPO1–4), a group of secreted Wnt agonists, can bind to LGR4, LGR5, and LGR6 (7, 8). LGR5 is a potential target of Wnt signaling, since Lgr5 expression is decreased when transcription factor 4-mediated Wnt signaling is suppressed (9). Lgr5−/− mice show neonatal lethality due to ankyloglossia and intestinal disorder (10, 11). Both LGR5 and LGR4 can physically associate with the Frizzled/lipoprotein receptor-related protein (Lrp) Wnt-receptor complex and facilitate Wnt signaling (7, 8). Conditional deletion of both Lgr4 and Lgr5 in the mouse gut leads to rapid degeneration of intestinal crypts, which are sites for stem cell niche (8).

The ovary and the uterus play major roles in female reproductive success. The ovary is the major source of steroid hormones, estrogen, and progesterone (P4). These hormones are responsible for maturation of the reproductive organs as well as initiation and maintenance of pregnancy (12, 13). During pregnancy, the uterus serves to home and nurture the embryo (14). The corpus luteum (CL) develops from the granulosa cells of newly ovulated follicles. P4 produced by the CL is required for preparing the uterus for implantation and pregnancy maintenance (15). In rodents, the stromal cells surrounding the implantation chamber proliferate and differentiate into specialized decidual cells (decidualization). P4 is indispensable for appropriate decidualization, since P4 withdrawal results in decidualization failure and pregnancy termination (16).

We previously showed that Lgr5 is expressed in uterine epithelia of immature and adult ovariectomized females (17). Surprisingly, its expression in ovariectomized mice was remarkably down-regulated after exogenous administration of estradiol-17β (E2) or P4. Lgr5 expression in immature uteri may suggest that Lgr5 is involved in uterine growth (17). The persistent expression of Lgr5 in the uteri of ovariectomized mice may also suggest its role in maintaining cell survival and integrity in the uterus deprived of growth stimulation. However, Lgr5's function in the mouse uterus remained unknown.

To explore the definitive role of Lgr5 in the uterus, we generated mice with conditional deletion of Lgr5 in the reproductive organs by crossing floxed Lgr5 mice (Lgr5f/f) with progesterone receptor (Pgr)-driven Cre (Pgrcre/+) mice (8, 18). Lgr5 deletion did not affect the development or architecture of the uterus. However, ∼70% of plug-positive Lgr5f/f/Pgrcre/+ (Lgr5d/d) females failed to deliver pups. On further examination, we found an increased number of resorption sites on d 8 of pregnancy with low levels of serum P4 and increased expression of luteal 20α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (20αHSD) in Lgr5d/d females. Notably, Lgr5 is expressed in the corpus luteum (CL), the site of major P4 synthesis. More interestingly, P4 supplementation rescued decidualization failure and advanced pregnancy to full term in Lgr5d/d females. These results suggest that luteal LGR5 is critical for continued production of P4 during pregnancy. Although it cannot be completely ruled out, uterine Lgr5 does not appear to be critical for uterine functions to support implantation and pregnancy establishment in mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Lgr5loxP/loxP mice were originally generated by H.C.'s group (8). Pgrcre/+ mice were obtained from Francesco DeMayo and John Lydon (Baylor College of Medicine, Baylor University, Houston, TX, USA; ref. 18). Mice with ovarian and uterine deletion of Lgr5 were created by breeding Lgr5loxP/loxP mice with Pgrcre/+ mice. Genotyping was performed by PCR analysis of genomic DNA extracted from the tail. For experiments, littermate Lgr5loxP/loxP/Pgr+/+ (Lgr5f/f) and Lgr5loxP/loxP/Pgrcre/+ (Lgr5d/d) females were utilized within the same set of experiments to ensure the validity of our results. To induce pseudopregnancy, wild-type (WT) female mice were mated with vasectomized males. All mice used in this investigation were housed in barrier facilities in the Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center's Animal Care Facility according to U.S. National Institutes of Health and institutional guidelines for the use of laboratory animals. All protocols for the present study were reviewed and approved by the Cincinnati Children's Research Foundation's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice were provided with autoclaved rodent Lab Diet 5010 (Purina, St. Louis, MO, USA) and UV light-sterilized RO/DI constant circulation water ad libitum.

Hormone treatment in immature females

Immature (3-wk-old) female mice were injected i.p. with 5 IU pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (PMSG; Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA, USA) to stimulate follicular growth. After 48 h, the mice were injected i.p. with 5 IU human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG; Pregnyl; Oragnon Special Chemicals, Oss, The Netherlands) to promote ovulation and luteinization. Ovaries were collected on the given days after hCG injection.

Analyses of preimplantation embryo development, implantation, decidualization, and pregnancy outcome

Lgr5f/f or Lgr5d/d females were mated with WT fertile males to induce pregnancy. The day of finding vaginal plug was considered d 1 of pregnancy. To examine preimplantation embryo development and oviductal embryo transport, mice were killed on d 4 of pregnancy, and uteri were flushed with saline to recover blastocysts. To examine implantation, pregnant dams were assessed on d 5 and 6 mornings. Implantation sites were visualized by intravenous injection of a Chicago blue dye solution, and the number of implantation sites, demarcated by distinct blue bands, was recorded. Uteri of mice without blue bands were flushed with saline to recover unimplanted blastocysts. To assess decidualization, the number and wet weights of implantation sites were assessed on d 8. For litter size analysis, pregnant females were monitored daily from d 17 through 21 for parturition timing and litter size.

Exogenous P4 supplement

To see whether P4 supplementation rescues decidualization failure in Lgr5d/d mice, deleted females were mated with WT fertile males and given a daily injection of P4 (1 mg/0.1 ml/mouse, s.c.) from d 3 through 7. Mice were killed on d 8 of pregnancy, and the number and weights of implantation sites were recorded. To determine whether P4 supplementation rescues the infertility phenotype of Lgr5d/d females, they were mated with WT fertile males, and a Silastic implant (4 cm length×0.31 cm diameter; Dow Corning, Midland, MI, USA) containing P4 was placed under the dorsal skin on d 3 of pregnancy. Implants were removed on d 16 to allow parturition to occur successfully (19).

Histological analysis and immunostaining

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded uterine sections (5 μm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for histological analysis or immunostained for Ki67 to assess cell proliferation status. After deparaffinization and hydration, sections were subjected to antigen retrieval by autoclaving in 10 mM sodium citrate solution (pH 6.0) for 10 min. A diaminobenzidine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) solution was used to visualize antigens. Sections were counterstained with eosin or hematoxylin (20).

Measurement of serum E2 and P4 levels

Serum levels of E2 and P4 on d 4 and 8 of pregnancy were measured by EIA kits (Cayman Chemical Co., Ann Arbor, MI, USA).

Semiquantitative and quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR)

Lgr5f/f or Lgr5d/d ovarian and uterine RNA samples were analyzed as described previously (21, 22). In brief, total RNA was extracted with Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. After DNase treatment (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA), 1 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed with Superscript II (Invitrogen). Semiquantitative RT-PCR was performed using primers 5′-CCTTCCCTGTGACTGGGTTA-3′ and 5′-GCCTTCAGGTCTTCCTCAAA-3′ for Lgr5 and 5′-GTGGGCCGCCCTAGGCACCAG-3′ and 5′-CTCTTTGATGTCACGCACGATTTC-3′ for β-actin. Quantitative RT-PCRs were performed with primers 5′-CTCTGAAGCCAGGGAATGAG-3′ and 5′-ATGGCATTCTACCTGGTTGC-3′ for 20αHSD; 5′-GTTGTCATCCACACTGCTGC-3′ and 5′-CAGGCCTCCAATAGGTTCTG-3′ for 3βHSD; 5′-TCACTTGGCTGCTCAGTATTGAC-3′ and 5′-TCTATCTGGGTCTGCGATAGGAC-3′ for steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR); 5′-CGGTACTTGGGCTTTGGCT-3′ and 5′-AGCAGATTGATAAGGAGGATGGTC-3′ for P450 cholesterol side-chain cleavage (P450scc), and 5′-TCCATGACAACTTTGGCATTG-3′ and 5′-CAGTCTTCTGGGTGGCAGTGA-3′ for Gapdh. In a real-time PCR system, Gapdh was used as a normalization standard. Relative quantification data from quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis were statistically analyzed using Student's t tests.

Ovarian genomic DNA extraction and genotyping

Lgr5f/f or Lgr5d/d ovarian genomic DNA samples were prepared with Trizol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Lgr5 genotyping was performed by PCR with primers 5′-TGCCACCTTGATCAACATTT-3′ and 5′- GGAGTGATCGTCTTTGAGCA-3′.

In situ hybridization

The cDNA clone for 20αHSD was generated by RT-PCR with mouse specific primers, 5′-CAGAGCAGTGGCTGAGAATG-3′ and 5′-CCCTTTTCACAGTGCCATCT-3′. Lgr5 partial cDNA fragment generated by RT-PCR was cut with restriction enzymes SacI and DraIII to generate the cDNA clone. Paraformaldehyde-fixed frozen sections were hybridized with 35S-labeled cRNA probes as described previously (23).

Statistical analysis

A χ2 test was used to analyze pregnancy success rates, and Student's t tests were performed for the analysis of other data sets. Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant. All values are shown as means ± sem.

RESULTS

Mice with conditional deletion of Lgr5 in female reproductive tissues show reduced fertility

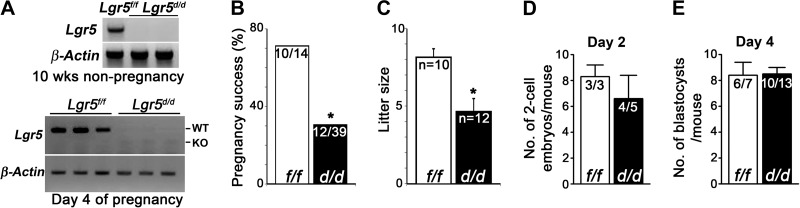

Our first objective was to examine whether Lgr5 deletion influences uterine function. Since systemic deletion of Lgr5 is embryonically lethal, we generated Lgr5d/d and Lgr5f/f as described in Materials and Methods (8, 18). The efficiency of uterine Lgr5 deletion was examined by RT-PCR using RNA collected from Lgr5f/f and Lgr5d/d uteri at 10 wk of age and on d 4 of pregnancy. As expected, Lgr5 mRNA was undetectable in Lgr5d/d uteri (Fig. 1A). To study the role of LGR5 in female reproduction, Lgr5d/d and Lgr5f/f females were mated with WT fertile males. Only ∼30% of plug-positive Lgr5d/d females (12 of 39) successfully delivered pups, whereas >70% plug-positive Lgr5f/f females produced progenies (Fig. 1B). Of the dams producing offspring, litter sizes in Lgr5d/d females (4.7±0.8 pups/litter, n=12) were smaller compared to Lgr5f/f mice (8.2±0.5 pups/litter, n=10) (Fig. 1C). These results indicated that Lgr5d/d females have severely compromised fertility.

Figure 1.

Lgr5 deletion is efficient in Lgr5d/d uteri, and pregnancy outcome is compromised in Lgr5d/d females. A) RT-PCR results show floxed and deleted mRNA levels of Lgr5 in uteri from 10-wk-old and d 4 pregnant females. B) Pregnancy success rate in Lgr5d/d females is much lower than in Lgr5f/f females. *P < 0.05; χ2 test. C) Litter sizes in Lgr5f/f and Lgr5d/d Lgr5d/d mice. *P < 0.05; Student's t test. D) Ovulation and fertilization in Lgr5f/f and Lgr5d/d mice. E) Number of blastocysts recovered from d 4 uteri (no. of pregnant females/total no. of plug-positive females).

Ovulation, fertilization, and preimplantation embryo development are comparable between Lgr5f/f and Lgr5d/d mice

To determine the cause of compromised pregnancy outcome in Lgr5d/d females, we examined the site- and stage-specific effects of Lgr5 deletion during pregnancy. Ovulation and fertilization were examined by flushing the oviducts from both Lgr5f/f and Lgr5d/d mice on d 2 of pregnancy. The number of recovered 2-cell embryos was comparable in Lgr5f/f and Lgr5d/d females (Fig. 1D). Lgr5d/d oviducts were also capable of supporting normal development of preimplantation embryos and their transport from the oviduct to the uterine lumen, as evident from a comparable number of blastocysts retrieved from Lgr5f/f and Lgr5d/d uteri on d 4 of pregnancy (Fig. 1E).

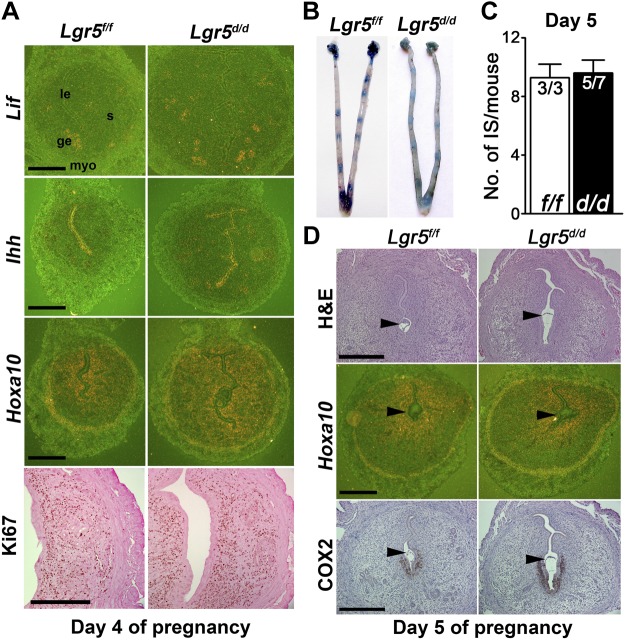

Expression of uterine receptivity marker genes is normal in Lgr5d/d uteri

Successful implantation requires a receptive uterus and an implantation-competent blastocyst. In normal pregnancy, the uterus becomes receptive with spatiotemporal expression of several critical P4- and estrogen-responsive genes, such as homeobox A10 (Hoxa10), Indian hedgehog (Ihh), and leukemia inhibitory factor (Lif), on d 4 of pregnancy. The P4-responsive genes Hoxa10 and Ihh are expressed in the stroma and epithelium, respectively, whereas estrogen-responsive gene Lif is expressed in the glandular epithelium (24–26). The expression pattern of these genes was examined by in situ hybridization in d 4 uterine sections of Lgr5f/f and Lgr5d/d females. The expression patterns of these genes were comparable in Lgr5f/f and Lgr5d/d females (Fig. 2A). During the receptive phase, uterine luminal epithelial cells undergo differentiation and cease proliferation, while stromal cells show extensive proliferation in preparation for implantation and decidualization (12). Cell proliferation status was examined by Ki67 immunostaining. The results show that Lgr5f/f and Lgr5d/d uteri had similar patterns of Ki67 immunostaining (Fig. 2A). Taken together, the results provide evidence that Lgr5d/d uteri are able to acquire uterine receptivity for implantation.

Figure 2.

Uterine receptivity and early implantation are apparently normal in Lgr5d/d females. A) In situ hybridization of Lif, Ihh, and Hoxa10, and immunostaining of Ki67 on d 4 of pregnancy. le, luminal epithelium; s, stroma; ge, glandular epithelium; myo, myometrium. B, C) Representative uteri and number of implantation sites from Lgr5f/f and Lgr5d/d females on d 5 of pregnancy. D) Implantation histological, in situ hybridization, and immunohistochemical analyses of representative uteri from Lgr5f/f and Lgr5d/d females on d 5 of pregnancy. Scale bars = 400 μm. Arrowheads depict the location of blastocysts.

Early implantation events in Lgr5d/d females are normal

The attachment of blastocysts with the uterine luminal epithelium occurs in the evening of d 4 of pregnancy in mice. This is coincident with localized vascular permeability in the stromal bed at the site of attachment. On the morning of d 5 of pregnancy, increased vascular permeability restricted at the implantation site was visualized by an intravenous injection of a blue dye solution as discrete blue bands along the uterus (27). We found that the number of implantation sites and the intensity of blue bands in Lgr5f/f and Lgr5d/d females were comparable (Fig. 2B, C). The histology of implantation sites in Lgr5f/f and Lgr5d/d females also appeared appropriate with blastocysts implanting in the luminal crypts at the antimesometrial pole (Fig. 2D). To further assess the quality of implantation in Lgr5d/d females, we examined the expression of cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2) and Hoxa10, which are known to be critical for implantation (24, 28, 29). The expression pattern of the two genes in Lgr5d/d females was similar to that in floxed females (Fig. 2D). While COX2 was present in both luminal epithelial and stromal cells at the site of the blastocyst, Hoxa10 was expressed in stromal cells around the implantation chamber and in the circular muscle layer. Taken together, these results suggest that initiation of implantation appears normal in Lgr5d/d females.

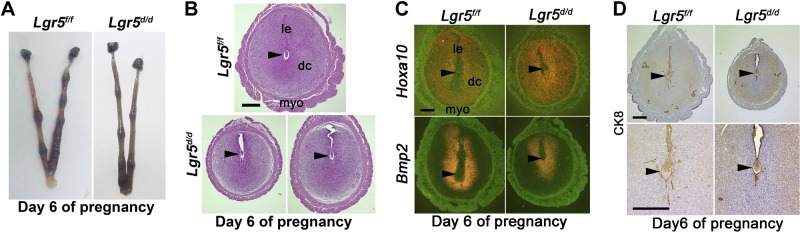

Decidualization is compromised in Lgr5d/d females

We next examined whether Lgr5 deletion affects uterine function following implantation. On d 6 and 7 of pregnancy, the number of implantation sites was comparable between Lgr5f/f and Lgr5d/d females, but the size of implantation sites was little smaller in Lgr5d/d females (Fig. 3A, B and Supplemental Table S1). To assess the status of decidualization in Lgr5d/d, we examined the expression of critical decidualization markers Hoxa10 and Bmp2 on d 6 of pregnancy (24, 30, 31). In Lgr5f/f implantation sites, Hoxa10 was expressed in decidual cells in the secondary decidual zone, but not in cells in the primary decidual zone, whereas Lgr5d/d decidual cells around the embryo were Hoxa10 positive (Fig. 3C), suggesting dysregulated decidualization. The expression domain and level of Bmp2 were also more restricted in Lgr5d/d implantation sites compared to Lgr5f/f (Fig. 3C). Taken together, these results suggest that decidualization in Lgr5d/d is compromised due to delayed and retarded decidual growth.

Figure 3.

Lgr5d/d females show defective decidualization. A) Representative uteri from Lgr5f/f and Lgr5d/d females on d 6 of pregnancy. B) Representative H&E-stained section of implantation sites from Lgr5f/f and Lgr5d/d females on d 6 of pregnancy. C) In situ hybridization of Hoxa10 and Bmp2 in Lgr5f/f and Lgr5d/d uteri on d 6 of pregnancy. le, luminal epithelium; dc, decidua; myo, myometrium. D) Immunostaining of CK8 in Lgr5f/f and Lgr5d/d uteri on d 6 of pregnancy. Scale bars = 400 μm.

In normal pregnancy, the onset of decidualization requires embryonic stimulation. The embryonic signal for decidualization transmits from the embryo through the epithelium to the stroma from d 5 onwards. Stromal cells are in direct contact with trophoblast cells by d 6 of pregnancy when luminal epithelial cells around the implanting embryos had undergone apoptosis (12). In mice with uterine deletion of Kruppel-like factor 5 (Klf5), the luminal epithelial cells around implanting embryos remain intact even on d 6 of pregnancy, precluding direct embryonic contact with the stroma (32). It is possible that the compromised decidualization in Lgr5d/d is due to retention of epithelial cells around the implanting embryo. Therefore, we examined the status of the luminal epithelium by immunostaining of cytokeratin 8 (KRT8), an epithelial cell marker in Lgr5f/f and Lgr5d/d implantation sites on d 6. In both groups, the epithelial cells around the embryos were absent, as evident from the disappearance of honeycomb staining of KRT8 in uterine epithelial cells (Fig. 3D); only embryonic trophoblasts showed positive KRT8 signals. The results suggested that embryos were in direct contact with stromal cells, demonstrating that both Lgr5f/f and Lgr5d/d stromal cells received appropriate signals for decidualization with the loss of the epithelium. The observation confirmed that embryos successfully implant in Lgr5d/d uteri and suggested that compromised decidualization in Lgr5d/d is not due to insufficient signals from the embryo or the epithelium.

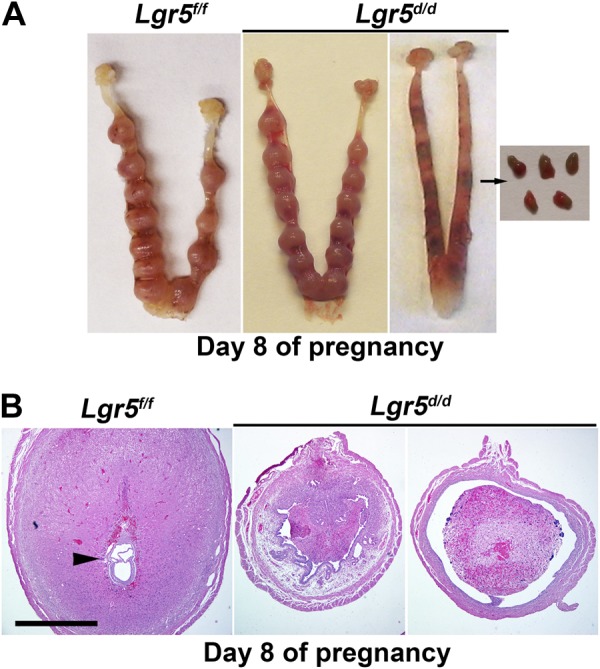

We further examined the implantation sites in Lgr5d/d females on d 8 of pregnancy when decidual growth is maximal. Surprisingly, all implantation sites in 9 of 12 Lgr5d/d females showed resorptions (Table 1 and Fig. 4A). Further histological analysis of the resorption sites showed degenerating decidual cells with the new epithelial layer forming underneath the degenerating decidua (Fig. 4B). Notably, Lgr5 is very low to undetectable at the implantation sites on d 5 and 8 of pregnancy (ref. 17 and Supplemental Fig. S1). These results showed that pregnancy failure occurred at the decidual stage and suggested that compromised decidualization was not the direct effect of uterine deletion of Lgr5.

Table 1.

P4 supplementation rescues decidualization failure in Lgr5d/d mice on d 8 of pregnancy

| Genotype | P4 | Mice examined | Pregnant mice | Mice with resorption | Implantation sites |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lgr5f/f | − | 12 | 8 | 0 | 9.1 ± 1.2 |

| Lgr5d/d | − | 15 | 12 | 9 | 11.7 ± 0.7 |

| Lgr5d/d | + | 5 | 5 | 0 | 8.8 ± 0.6a |

Average of the weight of implantation sites is comparable in Lgr5

mice with P4 supplementation (28.5±2.6 mg) and Lgr5

mice (24.7±1.1 mg).

Figure 4.

Lgr5d/d females show an increased rate of resorptions on d 8 of pregnancy. A) Representative uteri from Lgr5f/f and Lgr5d/d females on d 8 of pregnancy. Mass of degenerating decidual cells is seen within the lumen of Lgr5d/d uteri with resorbing implantation sites. B) Representative H&E-stained section of implantation sites from Lgr5f/f and Lgr5d/d females on d 8 of pregnancy. A section of resorbing implantation sites from Lgr5d/d uterus shows massive infiltration of blood cells. Scale bar = 1 mm.

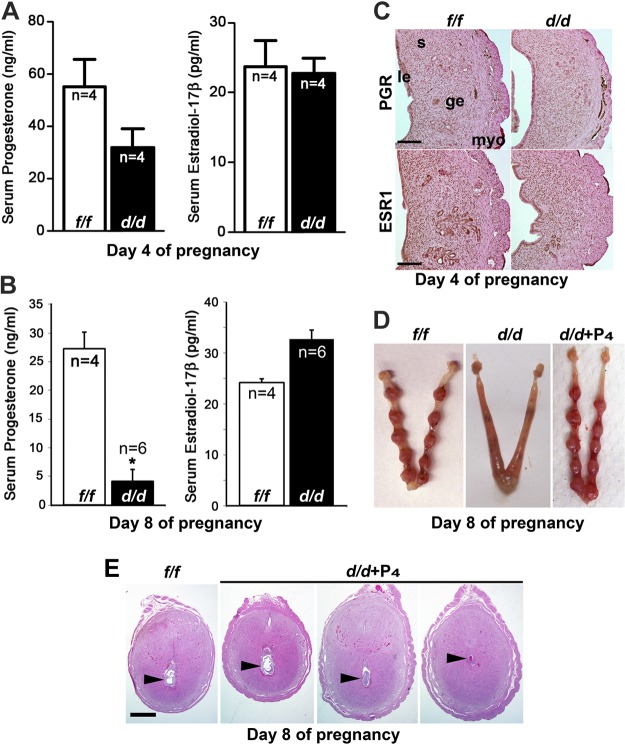

Decidualization failure in Lgr5d/d females is due to reduced serum P4 levels

The phenotype observed in Lgr5d/d mice is reminiscence of the characteristics of postimplantation pregnant mice with insufficient P4 (33). Since both P4 and E2, especially P4, are required to initiate optimal decidualization, we measured serum P4 and E2 levels in Lgr5f/f and Lgr5d/d females during pregnancy. On d 4 of pregnancy, E2 level was comparable between Lgr5f/f and Lgr5d/d females (Fig. 5A). P4 levels were somewhat lower in Lgr5d/d females compared with those in Lgr5f/f females, although the differences were not statistically significant. On d 8, P4 levels dramatically declined in Lgr5d/d females, whereas E2 levels were within the reported range in both Lgr5f/f and Lgr5d/d females (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, among all Lgr5d/d females examined for serum P4 levels, the levels in those deleted females with normal implantation sites were similar to those observed in Lgr5f/f females. We also examined the expression status of the nuclear receptors for progesterone (PGR) and estrogen [estrogen receptor 1(ESR1)] in Lgr5f/f and Lgr5d/d uteri and found the localization patterns of PGR and ESR1 comparable in d 4 uteri of both genotypes (Fig. 5C). These observations provide evidence that a fall in P4 levels led to early resorption of decidua in Lgr5d/d females.

Figure 5.

P4 supplementation rescues decidualization failure in Lgr5d/d females. A,B) Serum levels of P4 and E2 on d 4 (A) and d 8 (B) of pregnancy (means±sem). *P < 0.05; Student's t test. C) Immunostaining of PGR and ESR1 shows a similar expression pattern and intensity in Lgr5f/f and Lgr5d/d on d 4 of pregnancy. le, luminal epithelium; s, stroma; ge, glandular epithelium; myo, myometrium. D) Daily injection of P4 (1 mg/mouse, s.c.) rescues the defects of decidualization in Lgr5d/d females. Sizes of implantation sites are comparable with those of Lgr5f/f. E) Representative H&E-stained section of implantation sites from Lgr5f/f females and Lgr5d/d females with P4 supplementation on d 8 of pregnancy. Scale bars = 200 μm.

P4 supplementation rescues decidualization and pregnancy failure in Lgr5d/d females

To examine whether the decline in P4 levels was the main cause for decidual failure in Lgr5d/d females, we provided P4 supplementation to restore decidualization in Lgr5d/d females. Indeed, daily injection of P4 (1 mg/0.1 ml/mouse, sc) from d 3 through 7 prevented resorption of implantation sites in 100% of Lgr5d/d females. (Table 1 and Fig. 5D). The average weight of implantation sites was comparable between Lgr5d/d females with P4 supplementation and Lgr5f/f females (28.5±2.6 mg, n=5 vs. 24.7±1.1 mg, n=8). Histological analysis showed that P4 supplement greatly improved the decidual response and embryo development in Lgr5d/d females, although some implantation sites had less developed embryos (Fig. 5E).

With rescue of decidual failure in Lgr5d/d dams, we next investigated whether P4 supplement is sufficient to support pregnancy to full term in Lgr5d/d females. For this set of experiments, Silastic implants containing P4 were placed under the back skin of pregnant females from d 3 to 16 of pregnancy; implants were removed on d 16, since P4 withdrawal is necessary to initiate labor (34, 35). Eighty-seven percent (7 of 8) of Lgr5d/d females delivered pups with normal weights although the litter sizes were little smaller than those in Lgr5f/f counterparts (6.4±0.9 vs. 8.2±0.5 pups/litter). These results clearly show that decidual defects and severe subfertility in Lgr5d/d females resulted from impaired P4 production and that P4 supplementation not only rescued the decidual defect but also restored pregnancy to term.

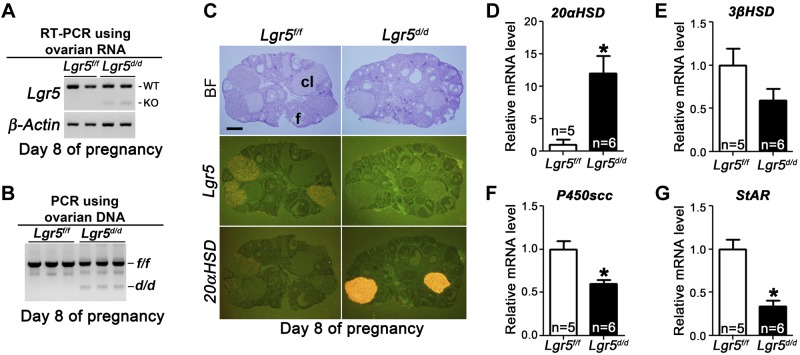

Lgr5 deletion increases 20αHSD expression in the CL and reduces serum P4 levels

Our next objective was to identify the mechanisms by which serum P4 levels were reduced in Lgr5d/d females during pregnancy. In mice, the CL is the main site of P4 biosynthesis during pregnancy, and serum P4 levels are controlled by its biosynthesis and degradation in the CL (36). Therefore, we examined whether Lgr5 was expressed and whether Pgr-Cre deletes Lgr5 in the ovary. RT-PCR results showed that Lgr5 was expressed in the ovary (Fig. 6A), and deletion of Lgr5 by Pgr-Cre was confirmed by PCR analysis of genomic DNA (Fig. 6B) and mRNA (Fig. 6A). Using in situ hybridization, we observed that Lgr5 was primarily localized in the CL and ovarian surface epithelium in Lgr5f/f females. In contrast, much lower Lgr5 signals were noted in the CL of Lgr5d/d females, but the signals on surface epithelium were comparable in both genotypes, suggesting Lgr5 deletion by Pgr-Cre restricted to the CL, but not in the surface epithelium (Fig. 6C). This observation corroborates the previous report that Pgr-Cre can recombine loxP sites in the CL (18, 21).

Figure 6.

Lgr5 deletion is efficient in Lgr5d/d Lgr5d/d CL and increased 20αHSD levels in Lgr5d/d CL. A) RT-PCR results show intact and deleted Lgr5 mRNA levels in Lgr5f/f and Lgr5d/d ovaries on d 8 of pregnancy. B) PCR results show floxed (f/f) and deleted (d/d) Lgr5 genomic DNA in ovaries on d 8 of pregnancy. C) In situ hybridization of Lgr5 and 20αHSD in Lgr5f/f and Lgr5d/d ovaries on d 8 of pregnancy. BF, bright field; CL, corpus luteum; F, follicle. Scale bar = 400 μm. D–G) Quantitative RT-PCR of 20αHSD (D), 3βHSD (E), P450scc (F), and StAR (G) in ovaries on d 8 of pregnancy. *P < 0.05; Student's t test.

P4 is biosynthesized from cholesterol (36). Cholesterol, which is transported into mitochondria by StAR (37), is converted to pregnenolone by P450scc and then to P4 by 3βHSD. In rodents, 20αHSD metabolizes P4 in the CL and decreases serum P4 levels. Although Lgr5 deletion did not alter ovarian histology (Supplemental Fig. S2), its location in the CL overlaps the expression of enzymes involved in P4 synthesis and metabolism, prompting us to examine the expression of those enzymes. As shown in Fig. 6D, qPCR results showed that 20αHSD expression levels were significantly higher in Lgr5d/d ovaries, and this result was correlated with increased levels of 20αHSD in the CL, as detected by in situ hybridization (Fig. 6C). In addition, the expression of enzymes involved in steroidogenesis, P450scc and StAR, significantly decreased in Lgr5d/d ovaries (Fig. 6F, G). The expression of 3βHSD showed a similar trend, although the changes between Lgr5f/f and Lgr5d/d ovaries were not significant (Fig. 6E). In rodents, prolactin secretion from the pituitary gland plays a key role in maintaining CL function. Therefore, we examined whether Lgr5 is expressed in the PR-expressing mouse pituitary (18). In situ hybridization results show that Lgr5 RNA was not detectable in the mouse pituitary (Supplemental Fig. S3). Taken together, these results suggest that inactivation of luteal Lgr5 disrupts normal expression of P4 synthetic and metabolic enzymes, resulting in decreased serum P4 levels during decidualization.

Lgr5 is expressed in the regressing CL

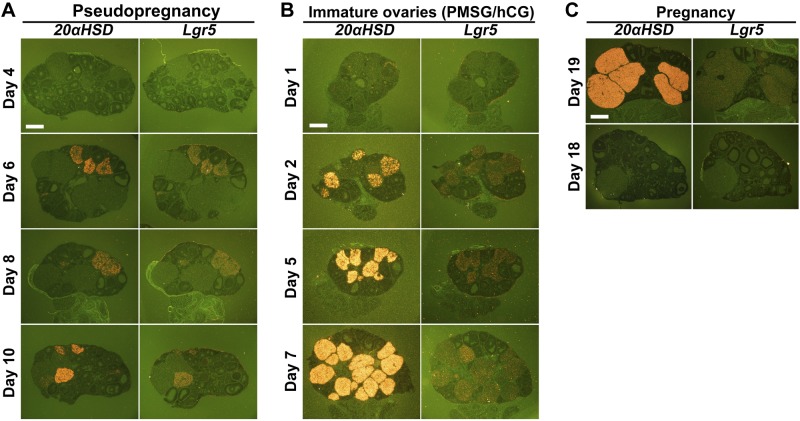

Decreased levels of P4 synthetic enzymes with increases of a primary metabolic enzyme in Lgr5d/d ovaries suggest the CL was undergoing regression. The reduced secretion of P4 resulting from elevated 20αHSD can occur without complete structural regression of the CL (15). The expression of 20αHSD increases in the regressing CL after ovulation in cyclic rodents and just prior to parturition. To study further the relationship between Lgr5 expression and CL regression, we examined the expression of 20αHSD and Lgr5 in ovaries of pseudopregnant females which were generated by mating females with vasectomized males. In the absence of embryos or implantation sites in these mice, CLs start to regress with the expression of 20αHSD on d 6, 8, and 10 of pseudopregnancy. Our in situ hybridization results show that 20αHSD and Lgr5 were colocalized in the CL in pseudopregnant females (Fig. 7A). This observation was confirmed in immature ovaries treated with a superovulation regimen of PMSG and hCG, as well as in ovaries prior to parturition during normal pregnancy. 20αHSD and Lgr5 were colocalized in the CL of ovaries from immature mice on d 1, 2, 5, and 7 after hCG injections and ovaries from d 19 of pregnancy (Fig. 7B, C). The results show that Lgr5 always coexpressed with 20αHSD in the same CL. These results suggest that Lgr5 expression is closely correlated with the CL regression; in the absence of Lgr5, the CL prematurely regresses.

Figure 7.

Lgr5 is expressed in the regressing CL. A) In situ hybridization of Lgr5 and 20αHSD in ovaries of pseudopregnant females. B) In situ hybridization of Lgr5 and 20αHSD in ovaries of females at 3 wk of age. Females were treated with PMSG and hCG as described in Materials and Methods, and ovaries were collected on the given days after hCG injection. C) In situ hybridization of Lgr5 and 20αHSD in ovaries of females on d 18 and 19 of pregnancy. Scale bars = 400 μm.

DISCUSSION

The highlights of the present study are that Lgr5 is dispensable for normal ovulation, fertilization, preimplantation embryo development, and initial blastocyst attachment, and that compromised pregnancy outcome is the result of defective decidualization arising from the decline in serum P4 levels due to up-regulation of 20αHSD and down-regulation of P4 synthetic enzymes in Lgr5-deficient CL. These results suggest that Lgr5 deficiency primarily targets the CL-reducing output of P4, since supplementation of P4 rescues pregnancy defects in Lgr5d/d females, and that uterine inactivation of Lgr5 appears to have minimal, if any, adverse effects on pregnancy outcome. Our results demonstrate for the first time that LGR5 is critical for the maintenance of functional CL.

The main source of P4 during pregnancy is the CL, and P4 is an absolute requirement for successful implantation and pregnancy maintenance in mice. The apparent success in the early stages of implantation in Lgr5d/d females would suggest that P4 output in the Lgr5d/d mice was sufficient for implantation, but was insufficient for optimal decidualization and subsequent pregnancy maintenance when the decline in P4 levels was more conspicuous. Similarly, the differential requirement of P4 levels in implantation and maintenance of pregnancy was also observed in Fkbp52 mutant females with reduced PR signaling in the uterus (19). The absence of Lgr5 in the pituitary suggests that prolactin secretion by the organ perhaps was not altered in Lgr5d/d females to influence ovarian function. However, it is possible that decidual secretion of prolactin-like factors were compromised in the face of declining P4 levels in Lgr5d/d females and exacerbated the decidual demise, as found on d 8. Indeed, there is evidence that decidual prolactin-like proteins suppress the expression of 20αHSD (38).

The mechanism by which deficient luteal Lgr5 disrupts normal expression of P4 synthetic and metabolic enzymes is not clearly understood. Wnt signaling is known to influence both uterine and ovarian functions (39, 40). In this context, Wnt4 and Wnt receptors Frizzled 1 (Fzd1) and Fzd4 are predominantly expressed in ovarian tissues (41, 42). Fzd4-null females are infertile due to implantation failure resulting from decline in P4 levels similar to that also seen in prolactin receptor mutant mice (41, 43). Recent evidence shows that secreted agonists of Wnt-signaling RSPOs can bind to Lgr4/5/6 (44). There is also evidence that LGR5 interacts with Wnt receptors FZD and LRPs to trigger canonical Wnt signaling (45). Further investigation is warranted to see whether Lgr5 interacts with the Wnt-signaling pathway to influence ovarian function.

Apparently normal decidualization and pregnancy success in ∼30% of Lgr5d/d females could be due to inefficient deletion of luteal Lgr5 that is not sufficient to impact ovarian output of P4 by elevating 20αHSD in the CL. This is consistent with our observation of inefficient deletion of luteal Lgr5 in certain females that had normal decidualization and pregnancy outcome. However, it is also possible that another member of the LGR family compensates for the loss of Lgr5 and rescues pregnancy in a small cohort of females, since LGR5 is structurally similar to LGR4 and LGR6, and Lgr4 is found in CL in mouse ovaries (46). Like in the mouse gut, the deletion of both Lgr4 and Lgr5 causes rapid degeneration of intestinal crypts (8). There are other examples of such compensation by members of the same family in rescuing reproductive deficiency (12, 13). In this context, we have recently observed that deletion of Msx1 by Pgr-Cre showed partial implantation failure because Msx2 compensated for the loss of Msx1, but deletion of both members resulted in total infertility (47). Thus, it is possible that other LGR isoforms may compensate for the deletion of Lgr5 in mouse corpora lutea. Nonetheless, LGR5 appears to be a critical primary determinant of the CL function, since its deficiency terminated pregnancy in a majority of pregnant mice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Serenity Curtis for editing the manuscript and Amanda Bartos and Yingju Li for their help in immunostaining. Francesco DeMayo and John B. Lydon (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA) initially provided the Pgr-Cre mouse line.

This work was supported in part by U.S. National Institutes of Health grants (HD068524 and PO1CA7783), grants from March of Dimes to S.K.D., and a Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center Perinatal Institute pilot/feasibility grant to T.D. X.S. was supported by a Lalor Foundation postdoctoral fellowship. J.T. is supported by a Japan Society for the Promotion of Science postdoctoral fellowship sponsored by Kyoto University (Kyoto, Japan) and Cincinnati Children's Hospital.

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

- 20αHSD

- 20α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase

- CL

- corpus luteum

- COX2

- cyclooxygenase 2

- E2

- estradiol-17β

- ESR1

- estrogen receptor 1

- H&E

- hematoxylin and eosin

- hCG

- human chorionic gonadotropin

- Hoxa10

- homeobox A10

- Ihh

- Indian hedgehog

- KRT8

- cytokeratin 8

- Lgr5

- leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor

- Lif

- leukemia inhibitory factor

- Lrp

- lipoprotein receptor-related protein

- P4

- progesterone

- P450scc

- P450 cholesterol side-chain cleavage

- Pgr

- progesterone receptor

- PMSG

- pregnant mare serum gonadotropin

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- RT-PCR

- reverse transcription PCR

- RSPO

- R-spondin

- StAR

- steroidogenic acute regulatory protein

- WT

- wild-type

REFERENCES

- 1. Hsu S. Y., Liang S. G., Hsueh A. J. (1998) Characterization of two LGR genes homologous to gonadotropin and thyrotropin receptors with extracellular leucine-rich repeats and a G protein-coupled, seven-transmembrane region. Mol. Endocrinol. 12, 1830–1845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hsu S. Y., Kudo M., Chen T., Nakabayashi K., Bhalla A., van der Spek P. J., van Duin M., Hsueh A. J. (2000) The three subfamilies of leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptors (LGR): identification of LGR6 and LGR7 and the signaling mechanism for LGR7. Mol. Endocrinol. 14, 1257–1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barker N., Huch M., Kujala P., van de Wetering M., Snippert H. J., van Es J. H., Sato T., Stange D. E., Begthel H., van den Born M., Danenberg E., van den Brink S., Korving J., Abo A., Peters P. J., Wright N., Poulsom R., Clevers H. (2010) Lgr5(+ve) stem cells drive self-renewal in the stomach and build long-lived gastric units in vitro. Cell Stem Cell 6, 25–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jaks V., Barker N., Kasper M., van Es J. H., Snippert H. J., Clevers H., Toftgard R. (2008) Lgr5 marks cycling, yet long-lived, hair follicle stem cells. Nat. Genet. 40, 1291–1299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barker N., van Es J. H., Kuipers J., Kujala P., van den Born M., Cozijnsen M., Haegebarth A., Korving J., Begthel H., Peters P. J., Clevers H. (2007) Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature 449, 1003–1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Flesken-Nikitin A., Hwang C. I., Cheng C. Y., Michurina T. V., Enikolopov G., Nikitin A. Y. (2013) Ovarian surface epithelium at the junction area contains a cancer-prone stem cell niche. Nature 495, 241–245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Carmon K. S., Gong X., Lin Q., Thomas A., Liu Q. (2011) R-spondins function as ligands of the orphan receptors LGR4 and LGR5 to regulate Wnt/{beta}-catenin signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 11452–11457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. De Lau W., Barker N., Low T. Y., Koo B. K., Li V. S., Teunissen H., Kujala P., Haegebarth A., Peters P. J., van de Wetering M., Stange D. E., van Es J. E., Guardavaccaro D., Schasfoort R. B., Mohri Y., Nishimori K., Mohammed S., Heck A. J., Clevers H. (2011) Lgr5 homologues associate with Wnt receptors and mediate R-spondin signalling. Nature 476, 293–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Van de Wetering M., Sancho E., Verweij C., de Lau W., Oving I., Hurlstone A., van der Horn K., Batlle E., Coudreuse D., Haramis A. P., Tjon-Pon-Fong M., Moerer P., van den Born M., Soete G., Pals S., Eilers M., Medema R., Clevers H. (2002) The beta-catenin/TCF-4 complex imposes a crypt progenitor phenotype on colorectal cancer cells. Cell 111, 241–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Morita H., Mazerbourg S., Bouley D. M., Luo C. W., Kawamura K., Kuwabara Y., Baribault H., Tian H., Hsueh A. J. W. (2004) Neonatal lethality of LGR5 null mice is associated with ankyloglossia and gastrointestinal distension. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 9736–9743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Garcia M. I., Ghiani M., Lefort A., Libert F., Strollo S., Vassart G. (2009) LGR5 deficiency deregulates Wnt signaling and leads to precocious Paneth cell differentiation in the fetal intestine. Dev. Biol. 331, 58–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang H., Dey S. K. (2006) Roadmap to embryo implantation: clues from mouse models. Nat. Rev. 7, 185–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cha J., Sun X., Dey S. K. (2012) Mechanisms of implantation: strategies for successful pregnancy. Nat. Med. 18, 1754–1767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hess A. P., Nayak N. R., Giudice L. C. (2005) Oviduct and endometrium: cyclic changes in the primate oviduct. In Knobil and Neill's Physiology of Reproduction (Meill J. D., Richards J. S., eds) pp. 337–382, Academic Press, San Diego, CA, USA [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bachelot A., Binart N. (2005) Corpus luteum development: lessons from genetic models in mice. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 68, 49–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sharma R., Bulmer D. (1983) The effects of ovariectomy and subsequent progesterone replacement on the uterus of the pregnant mouse. J. Anat. 137(Pt. 4), 695–703 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sun X., Jackson L., Dey S. K., Daikoku T. (2009) In pursuit of leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor-5 regulation and function in the uterus. Endocrinology 150, 5065–5073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Soyal S. M., Mukherjee A., Lee K. Y., Li J., Li H., DeMayo F. J., Lydon J. P. (2005) Cre-mediated recombination in cell lineages that express the progesterone receptor. Genesis 41, 58–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tranguch S., Wang H., Daikoku T., Xie H., Smith D. F., Dey S. K. (2007) FKBP52 deficiency-conferred uterine progesterone resistance is genetic background and pregnancy stage specific. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 1824–1834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hirota Y., Daikoku T., Tranguch S., Xie H., Bradshaw H. B., Dey S. K. (2010) Uterine-specific p53 deficiency confers premature uterine senescence and promotes preterm birth in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 120, 803–815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Daikoku T., Yoshie M., Xie H., Sun X., Cha J., Ellenson L. H., Dey S. K. (2013) Conditional deletion of Tsc1 in the female reproductive tract impedes normal oviductal and uterine function by enhancing mTORC1 signaling in mice. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 19, 463–472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Daikoku T., Jackson L., Besnard V., Whitsett J., Ellenson L. H., Dey S. K. (2011) Cell-specific conditional deletion of Pten in the uterus results in differential phenotypes. Gynecol. Oncol. 122, 424–429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Daikoku T., Tranguch S., Trofimova I. N., Dinulescu D. M., Jacks T., Nikitin A. Y., Connolly D. C., Dey S. K. (2006) Cyclooxygenase-1 is overexpressed in multiple genetically engineered mouse models of epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 66, 2527–2531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lim H., Ma L., Ma W. G., Maas R. L., Dey S. K. (1999) Hoxa-10 regulates uterine stromal cell responsiveness to progesterone during implantation and decidualization in the mouse. Mol. Endocrinol. 13, 1005–1017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stewart C. L., Kaspar P., Brunet L. J., Bhatt H., Gadi I., Kontgen F., Abbondanzo S. J. (1992) Blastocyst implantation depends on maternal expression of leukaemia inhibitory factor. Nature 359, 76–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Matsumoto H., Zhao X. M., Das S. K., Hogan B. L. M., Dey S. K. (2002) Indian hedgehog as a progesterone-responsive factor mediating epithelial-mesenchymal interactions in the mouse uterus. Dev. Biol. 245, 280–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang H., Guo Y., Wang D., Kingsley P. J., Marnett L. J., Das S. K., DuBois R. N., Dey S. K. (2004) Aberrant cannabinoid signaling impairs oviductal transport of embryos. Nat. Med. 10, 1074–1080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Song H. S., Lim H. J., Das S. K., Paria B. C., Dey S. K. (2000) Dysregulation of EGF family of growth factors and COX-2 in the uterus during the preattachment and attachment reactions of the blastocyst with the luminal epithelium correlates with implantation failure in LIF-deficient mice. Mol. Endocrinol. 14, 1147–1161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lim H., Paria B. C., Das S. K., Dinchuk J. E., Langenbach R., Trzaskos J. M., Dey S. K. (1997) Multiple female reproductive failures in cyclooxygenase 2-deficient mice. Cell 91, 197–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lee K. Y., Jeong J. W., Wang J., Ma L., Martin J. F., Tsai S. Y., Lydon J. P., DeMayo F. J. (2007) Bmp2 is critical for the murine uterine decidual response. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 5468–5478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Paria B. C., Ma W., Tan J., Raja S., Das S. K., Dey S. K., Hogan B. L. (2001) Cellular and molecular responses of the uterus to embryo implantation can be elicited by locally applied growth factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98, 1047–1052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sun X., Zhang L., Xie H., Wan H., Magella B., Whitsett J. A., Dey S. K. (2012) Kruppel-like factor 5 (KLF5) is critical for conferring uterine receptivity to implantation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109, 1145–1150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Milligan S. R., Finn C. A. (1997) Minimal progesterone support required for the maintenance of pregnancy in mice. Hum. Reprod. 12, 602–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. McCormack J. T., Greenwald G. S. (1974) Progesterone and oestradiol-17beta concentrations in the peripheral plasma during pregnancy in the mouse. J. Endocrinol. 62, 101–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Paria B. C., Huet-Hudson Y. M., Dey S. K. (1993) Blastocyst's state of activity determines the “window” of implantation in the receptive mouse uterus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90, 10159–10162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stocco C., Telleria C., Gibori G. (2007) The molecular control of corpus luteum formation, function, and regression. Endocr. Rev. 28, 117–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Stocco D. M., Clark B. J. (1996) Regulation of the acute production of steroids in steroidogenic cells. Endocr. Rev. 17, 221–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bao L., Tessier C., Prigent-Tessier A., Li F., Buzzio O. L., Callegari E. A., Horseman N. D., Gibori G. (2007) Decidual prolactin silences the expression of genes detrimental to pregnancy. Endocrinology 148, 2326–2334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sonderegger S., Pollheimer J., Knofler M. (2010) Wnt signalling in implantation, decidualisation and placental differentiation: review. Placenta 31, 839–847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pangas S. A. (2007) Growth factors in ovarian development. Semin. Reprod. Med. 25, 225–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hsieh M., Boerboom D., Shimada M., Lo Y., Parlow A. F., Luhmann U. F., Berger W., Richards J. S. (2005) Mice null for Frizzled4 (Fzd4−/−) are infertile and exhibit impaired corpora lutea formation and function. Biol. Reprod. 73, 1135–1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hsieh M., Johnson M. A., Greenberg N. M., Richards J. S. (2002) Regulated expression of Wnts and Frizzleds at specific stages of follicular development in the rodent ovary. Endocrinology 143, 898–908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Grosdemouge I., Bachelot A., Lucas A., Baran N., Kelly P. A., Binart N. (2003) Effects of deletion of the prolactin receptor on ovarian gene expression. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 1, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wang D., Huang B., Zhang S., Yu X., Wu W., Wang X. (2013) Structural basis for R-spondin recognition by LGR4/5/6 receptors. Genes Dev. 27, 1339–1344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Birchmeier W. (2011) Stem cells: orphan receptors find a home. Nature 476, 287–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Van Schoore G., Mendive F., Pochet R., Vassart G. (2005) Expression pattern of the orphan receptor LGR4/GPR48 gene in the mouse. Histochem. Cell Biol. 124, 35–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Daikoku T., Cha J., Sun X., Tranguch S., Xie H., Fujita T., Hirota Y., Lydon J., DeMayo F., Maxson R., Dey S. K. (2011) Conditional deletion of Msx homeobox genes in the uterus inhibits blastocyst implantation by altering uterine receptivity. Dev. Cell 21, 1014–1025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.