Abstract

We report here the initial examination of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emanating from human earwax (cerumen). Recent studies link a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the adenosine triphosphate (ATP) binding cassette, sub-family C, member 11 gene (ABCC11) to the production of different types of axillary odorants and cerumen. ABCC11 encodes an ATP-driven efflux pump protein that plays an important function in ceruminous apocrine glands of the auditory canal and the secretion of axillary odor precursors. The type of cerumen and underarm odor produced by East Asians differ markedly from that produced by non-Asians. In this initial report we find that both groups emit many of the same VOCs but differ significantly in the amounts produced. The principal odorants are volatile organic C2-to-C6 acids. The physical appearance of cerumen from the two groups also matches previously reported ethnic differences, viz., cerumen from East Asians appears dry and white while that from non-Asians is typically wet and yellowish-brown.

Keywords: Cerumen, Volatile organic compounds, Earwax, GC/MS, SPME, Axillary odor

1. Introduction

Ceruminous glands are specialized sweat glands located subcutaneously in the external ear canal. It has been estimated that there are between 1,000 and 2,000 ceruminous glands in the ear. The ceruminous gland is a modified apocrine gland, which together with sebaceous glands, produces cerumen, or earwax [1, 2]. Cerumen keeps the eardrum pliable and lubricates, waterproofs, and cleans the external auditory canal. Cerumen also has antibacterial properties [3–5] and presents a barrier that traps foreign particles (dust, fungal spores, etc.). There are two distinct types of cerumen: wet, yellowish-brown wax, which is found in Caucasians and Africans; and a dry, white wax, which is most common in East Asians (e.g., Chinese, Korean and Japanese) and Native Americans [6–8].

The human adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-binding cassette (ABC) transporter gene ABCC11 encodes an ATP-driven efflux pump protein that plays an important function in ceruminous apocrine glands of the auditory canal [9, 10]. This protein is also expressed in axillary apocrine sweat glands and appears to play a role in regulating the secretion of axillary odor precursors [11, 12]. A simple change in ABCC11 results in the production of different types of axillary odorants and cerumen. Individuals who are homozygous for a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP; 538G>A), which changes amino acid 180 in the resultant protein’s polypeptide chain from glycine (G) to arginine (R; G180R), were found to have significantly less of the characteristic axillary odorants than either those who are heterozygous for this change or those who had the wild type gene [10, 13]. Although many studies have focused on the chemistry of human axillary odorants, to date, there are no data regarding the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) associated with human cerumen. The composition of cerumen has been assessed by several techniques (e.g., gas-chromatography [GC], gas chromatography–mass spectrometry [GC/MS], high performance liquid chromatography, and thin layer chromatography), which have revealed long-chain fatty acids, alcohols, triacylglycerols, cholesterol, and squalene as the major components [14–23]. Herein, we provide the first analysis of the nature and relative abundance of VOCs present in cerumen. We also directly compare volatile cerumen profiles of individuals of East Asian vs. Caucasian descent.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Collection of cerumen

All protocols were approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board (IRB) for Research Involving Human Subjects. For 7–10 days prior to collection, the subjects were instructed to bathe/shower with fragrance-free liquid soap/shampoo (Symrise, Inc., Teterboro, NJ) to reduce the influence of exogenous VOCs from consumer products during analysis. The subjects were also instructed not to use colognes and perfumed sprays during this time.

Cerumen was collected from both ears of 16 healthy males (N = 8 Caucasians, average age = 35 ± 5; and N = 8 East Asians, average age = 28 ± 3). Cerumen was collected on sterile, 6-inch, cotton-tipped wooden applicators (Fisher Scientific). The cotton applicator was inserted approximately 10–15 mm into the subject’s external auditory canal and gently swabbed. The applicator was removed from the ear and cerumen was transferred to a pre-weighed 4 mL clear glass vial (Supelco Corp., Bellefonte, PA) by rotating the cotton tip for 20 seconds on the bottom and sides of the vial. Collections were performed on at least three separate occasions, on nonconsecutive days. The cerumen sample weight was recorded after each collection.

Following cerumen collection, the sample vial was tightly capped with a white silicone/-TFE septum-containing screw cap and incubated in a 37°C water bath for 30 minutes. Solid-phase microextraction (SPME) was performed using a 2 cm, 50/30 μm divinylbenzyene/-carboxen/polydimethylsiloxane ‘Stableflex’ fiber (Supelco Corp., Bellefonte, PA). The fiber was introduced into the vial and the headspace VOCs were collected for an additional 30 min at 37°C. The SPME fiber was then inserted into the injection port of a GC/MS and the VOCs were desorbed for 1 min at 230 °C.

2.2 GC/MS

A Thermo Scientific ISQ single quadrupole GC/MS (Waltham, MA) with Xcalibur software (ThermoElectron Corp.) was used for separation and analysis of the desorbed VOCs. The GC/MS was equipped with a Stabilwax column, 30 m × 0.32 mm with 1.0 μm film thickness (Restek Corp., Bellefonte, PA). The injection port was set at 230°C. The oven temperature was held at 60°C for 4 min, raised to 230°C at 6°C min−1, and maintained at 230°C for 40-min. Helium carrier gas constantly flowed at 2.5 mL min−1.

The mass spectrometer was operated at an ionizing energy of 70 eV with a 2 s−1 scan rate over a scan range of m/z 40–400 and an ion source temperature of 200°C. Identification of structures/compounds was performed using the National Institute of Standards and Technology Library, as well as comparisons with known literature compounds and commercially available standards. All standards were purchased from either Sigma-Aldrich or Alfa Aesar at the highest available purity and used as received. Relative retention times were obtained by comparison of sample VOCs to authentic samples with a series of C2-C16 fatty acid ethyl esters (International Flavors and Fragrances Inc.) to obtain their “ethyl ester retention index” (EERI) [24].

2.3 Data Analysis

The mass spectra of all peaks ~1% above the baseline with a retention time between 5–35 min were examined to eliminate large, exogenous components arising from unwanted sources. These exogenous compounds can be attributed to liquid soap and cosmetic products (e.g., siloxanes, dodecanol), solvents (e.g., traces of acetone and chlorinated solvents), as well as compounds arising from septa and column bleed. The peaks of interest were normalized by both sample weight and an external standard (methyl stearate). Compounds consistently seen in all subjects were subjected to multivariate analyses of variance with IBM SPSS Statistics (v. 20).

3. Results and discussion

The cerumen samples from the Caucasian and East Asian donors exhibited notable differences. While the Caucasian samples were yellow and sticky in nature, cerumen collected from the East Asian donors was consistently drier and colorless. As the pH of cerumen is weakly acidic (~5.4; [25]) we assumed that many of the odoriferous VOCs would be volatile acids. Freshly collected cerumen was qualitatively rated by three odor judges: descriptors used were “acidic/pungent” “fecal” “sweaty feet.” Addition of a small amount (~30μl) of saturated bicarbonate solution to the collected cerumen eliminated the odor, further suggesting an odor profile dominated by organic acids.

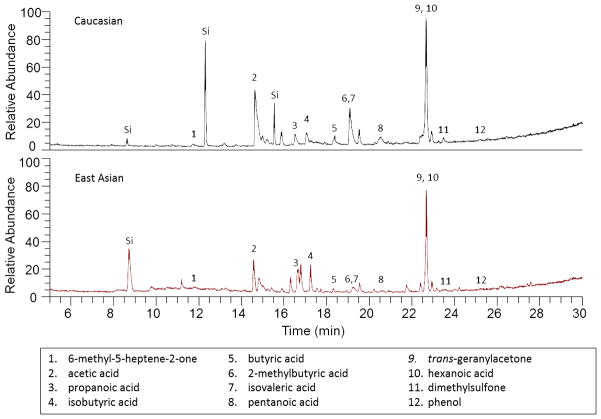

The SPME-collected VOCs were analyzed by GC/MS and representative chromatograms from a Caucasian and East Asian cerumen donor are shown in Fig. 1. A full list of identified compounds with retention times and characteristic ions can be found in Table 1. As noted, a number of the compounds can be attributed to exogenous sources. These compounds include typical organic compounds found in room air, consumer fragrance and flavor products, as well as shampoos and soaps (see reference [26] for an in-depth discussion). The endogenous compounds of interest are denoted in bold. Qualitatively, VOCs were similar across the two ethnic groups with volatile C2–C6 organic acids consistently observed. Ketones (e.g., 6-methyl-5-heptene-2-one, trans-geranylacetone) were also detected and may originate from the oxidation of squalene [27–29], a dominant component of cerumen [20–23]. Most volatile acids, alcohols and aldehydes found in skin secretions originate from interactions between non-odorous sebaceous gland secretions and cutaneous bacteria [30, 31]. Bacteria and yeast living in the hair follicle/sebaceous gland duct use lipases to liberate long-chain acids, hydroxyl-acids and keto-acids from triglycerides, which are further metabolized by aerobic bacteria into shorter, saturated and unsaturated volatile acids as well as volatile aldehydes and alcohols [31]. Cerumen VOCs most likely result from a similar mechanism where volatiles are produced from bacterial modification of cerumen-based compounds in the external auditory canal. We have also identified a homologous series of γ- and δ-lactones present in a small number of subjects, regardless of ethnicity. Lactones are attributed to the action of yeast (e.g., Pityrosporum Ovale) which dwell in the hair follicles and have been previously reported in human sweat and secretions [32–34].

Fig. 1.

Representative total ion chromatograms (TICs) from solid-phase microextraction (SPME) collection of cerumen samples from a Caucasian (top, 2.7 mg sample) and East Asian male (bottom, 2.2 mg sample) with endogenous VOCs labeled. Compounds labeled Si represent exogenous silicon contaminants. See Table 1 for full list of identified compounds.

Table 1.

VOCs emanating from human cerumen samples detected by solid-phase microextraction GC/MS techniques.

| RT (min) | Compound Assignment | Characteristic ions (m/z) | EERIa | Proportion of Subjectsb

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caucasian | East Asian | ||||

| 8.51 | limonene | 68, 93, 136 | |||

| 8.93 | unknown siloxane | 73, 341, 429 | |||

| 11.94 | 6-methyl-5-heptene-2-one | 43, 108, 126 | 7.15 | 7/8c | 8/8 |

| 12.46 | unknown siloxane | 73, 147, 281, 327 | |||

| 13.36 | 2-butoxyethanol | 57, 87 | 7.71 | ||

| 14.00 | unknown siloxane | 281 | |||

| 14.11 | unknown siloxane | 267, 355 | |||

| 14.85 | acetic acid | 43, 60 | 8.38 | 8/8 | 8/8 |

| 15.24 | 2-ethylhexanol | 57, 112 | 8.54 | ||

| 15.45 | unknown silicone impurity | 193, 209 | |||

| 15.60 | unknown siloxane | 73, 147, 281, 355 | |||

| 16.34 | benzaldehyded | 77, 105, 106 | 9.07 | 5/8 | 7/8 |

| 16.72 | propanoic acid | 57, 73, 74 | 9.24 | 8/8 | 8/8 |

| 17.28 | isobutyric acid | 43, 73, 88 | 9.51 | 7/8c | 8/8 |

| 18.18 | γ-pentanolactone | 85 | 9.99 | 1/8 | 0/8 |

| 18.48 | butyric acid | 60, 73 | 10.12 | 8/8 | 8/8 |

| 18.64 | unknown siloxane | 73, 355 | |||

| 19.30 | 2-methyl butyric acid | 74, 87 | 10.50 | 8/8 | 8/8 |

| 19.30 | isovaleric acid | 60, 87 | 10.50 | 8/8 | 8/8 |

| 19.99 | γ-hexanolactone | 85 | 10.85 | 5/8 | 0/8 |

| 20.59 | pentanoic acid | 60, 73 | 11.22 | 8/8 | 8/8 |

| 20.98 | unknown siloxane | 73, 147 | |||

| 21.16 | unknown siloxane | 73, 280 | |||

| 21.32 | unknown glycol | 45 | |||

| 21.75 | δ-hexanolactone | 99 | 11.78 | 2/8 | 0/8 |

| 21.89 | γ-heptanolactone | 85 | 11.85 | 3/8 | 0/8 |

| 22.45 | trans-geranylacetoned | 43, 69, 151 | 12.20 | 7/8c | 8/8 |

| 22.61 | hexanoic acid | 60, 73, 87 | 12.24 | 8/8 | 8/8 |

| 23.16 | δ-heptanolactone | 99 | 12.56 | 2/8 | 0/8 |

| 23.35 | unknown siloxane | 73, 355 | |||

| 23.52 | dimethylsulfone | 79, 94 | 12.82 | 8/8 | 8/8 |

| 23.56 | butylated hydroxytoluene | 205, 220 | 12.84 | ||

| 23.66 | 2,6-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-4-(1-oxopropyl)phenol | 233, 247 | 12.90 | ||

| 23.91 | γ-octanolactone | 85 | 12.99 | 4/8 | 0/8 |

| 24.42 | dodecanol | 55, 140, 168 | 13.24 | ||

| 24.42 | heptanoic acid | 60, 73, 87 | 13.37 | 7/8 | 5/8 |

| 24.63 | benzothiazoled | 108, 135 | 13.42 | 1/8 | 1/8 |

| 24.84 | δ-octanolactone | 99 | 13.51 | 3/8 | 0/8 |

| 25.34 | phenol | 66, 94 | 13.78 | 8/8 | 8/8 |

| 25.82 | γ-nonanolactone | 85 | 14.07 | 3/8 | 0/8 |

| 25.85 | unknown siloxane | 89, 355 | |||

| 26.21 | octanoic acid | 60, 73 | 14.37 | 5/8 | 5/8 |

| 26.59 | p-cresol | 107, 108 | 14.53 | 4/8 | 0/8 |

| 27.60 | 2-phenoxyethanol | 94, 138 | 15.13 | ||

| 27.70 | γ-decanolactone | 85 | 15.20 | 0/8 | 3/8 |

| 29.87 | unknown siloxane | 73, 355 | |||

| 33.82 | unknown siloxane | 73, 355 | |||

RT = retention time. Endogenous compounds denoted in bold.

EERI = ethyl ester retention indices.

Proportion of subjects, per ethnic group, in which the compound was detected.

Where no compound was detected, a conservative value of 1 was used in the statistical analysis.

Possibly exogenous or endogenous: compounds typically used in fragrance/consumer products, but can also result from naturally occurring precursors.

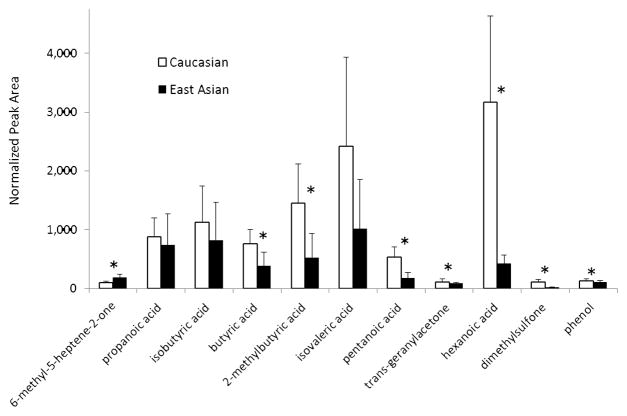

A direct comparison between the endogenous VOCs consistently detected in East Asian and Caucasian males is displayed in Fig. 2. The relative amounts of VOCs, with the exception of 6-methyl-5-heptene-2-one, were found to be greater in the Caucasian cerumen as compared to the East Asian cerumen. The decreased level of VOCs in East Asians mirrors the trend observed for axillary odors between the two ethnic groups. In the axillae, a variety of odiferous branched acids, including isovaleric acid and 2-methyl butyric acid, were significantly reduced in sweat samples from AA homozygotes, commonly found in those of East Asian descent, compared with samples from AG and GG genotypes, most common in Caucasian individuals [11]. The higher levels of 6-methyl-5-heptene-2-one in the Asian subjects may be attributed to higher amounts of sebaceous lipids (e.g., squalene) in Asians as compared to Caucasians [35, 36].

Fig. 2.

Comparison of VOCs sampled from the headspace of cerumen samples of Caucasian (N = 8, white) and East Asian (N = 8, black) donors averaged over three sample collections. Acetic acid (not shown because of scale) was elevated in Caucasians (7,944 ± 5,144 [s.e.]) relative to East Asians (4,547 ± 2,532 [s.e.]), but did not vary significantly between groups. Error bars represent standard error. Asterisks denote compounds that vary significantly (p < 0.05) between ethnic groups.

The VOCs for which sufficient data were available to enter into a MANOVA are listed in Table 2. Using all 12 compounds, the overall model was not statistically significant (Pillai’s Trace, p = 0.093). Two of the 12 VOCs, 6-methyl-5-heptene-2-one (p=0.028) and dimethylsulfone (p = .020), failed Levene’s test of equality of error variance. The overall model also failed because 6-methyl-5-heptene-2-one was significantly elevated in samples from East Asians (189 ± 58 [s.e.]) relative to those from Caucasians (107 ± 23 [s.e.]). However, the remaining 11 VOCs were elevated in Caucasians as compared to East Asians. Therefore, we removed 6-methyl-5-heptene-2-one and reanalyzed the data set with MANOVA. Not surprisingly, Levene’s test once again indicated that dimethylsulfone violated the assumption of equality of error variance. However, the overall model was significant, viz., the resulting Pillai’s Trace = 1.76; F(22,10) = 3.25, p = 0.029, ηp2 = 0.88, π = 0.85. Two measures of correlations among the variables were obtained, viz., the average bivariate correlation and the overall intraclass correlation (0.67 and 0.76, respectively). Ethnic differences among VOCs were also found to be statistically significant (p < 0.05) for 7 of the 12 VOCs, as listed in Table 2 and denoted by asterisks in Fig. 2.

Table 2.

MANOVA Tests of Between-Subjects Effects

| Source | Dependent Variable | df | F | Sig. | Partial η2 | Observed Power (π) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | 6-methyl-5-heptene-2-one | 2 | 11.90 | 0.001a | 0.63 | 0.98 |

| acetic acid | 2 | 2.549 | 0.114 | 0.27 | 0.43 | |

| propanoic acid | 2 | 3.444 | 0.061 | 0.33 | 0.55 | |

| isobutyric acid | 2 | 2.491 | 0.119 | 0.26 | 0.42 | |

| butyric acid | 2 | 6.612 | 0.010 | 0.49 | 0.84 | |

| 2-methylbutyric acid | 2 | 3.885 | 0.045 | 0.36 | 0.60 | |

| isovaleric acid | 2 | 2.298 | 0.137 | 0.25 | 0.39 | |

| pentanoic acid | 2 | 7.861 | 0.005 | 0.53 | 0.90 | |

| trans-geranylacetone | 2 | 5.866 | 0.014 | 0.45 | 0.79 | |

| hexanoic acid | 2 | 4.691 | 0.028 | 0.40 | 0.69 | |

| dimethylsulfone | 2 | 7.772 | 0.005 | 0.53 | 0.89 | |

| phenol | 2 | 15.20 | 0.0003 | 0.69 | 0.99 |

Bold = p < .05.

Only compound found in greater amount in East Asian as compared to Caucasian subjects.

Intercept was not included in overall model, hence df = 2. Partial η2 = proportion of variance explained by ethnicity.

Some have cautioned against the use of MANOVA when the dependent variables are highly correlated (>0.70) while others suggest that statistical power can increase when variables are correlated [37]. Herein, we report two measures of relatedness among the dependent variables. The values of these measures suggest a modest to moderate correlation among the variables in our set of data. We are expanding this work to include additional subjects and future analyses on this expanded data set should clarify our level of confidence to the extent in which our variables do not express significant multicollinearity.

4. Conclusions

We have examined, for the first time, VOCs emanating from human cerumen. The major volatile components, volatile organic C2-to-C6 acids, were found to be qualitatively similar for both the dry and wet cerumen phenotypes, although significant quantitative differences in volatile compounds were noted. Overall, the Caucasian subjects, exhibiting the characteristic wet, yellow cerumen, had much higher levels of VOCs than those measured in the dry cerumen obtained from the East Asian subjects, consistent with previous findings correlating a dry cerumen phenotype with decreased production of axillary odorants [10, 13].

Cerumen is much more easily obtained than are axillary odors, and VOCs from the ear may serve as a surrogate model for investigating human axillary odor type. In addition, cerumen is very lipophilic, and may act as an ideal substrate for retaining organic compounds indicative of physiological, dietary and environmental events and/or exposures, as suggested by a recent study involving the chemical analysis of the earwax from a blue whale. In this mammal, a 25 cm-long earwax plug revealed lifetime patterns of analytes including cortisol (stress hormone), testosterone (developmental hormone), organic contaminants (e.g., pesticides and flame retardants), and mercury [38]. More investigations to gather data addressing the above points warrant further analytical examination of this little-studied human secretion.

Highlights.

We provide the first analysis of VOCs present in human cerumen.

Cerumen emits a complex mixture of VOCs, with the principal odorants being volatile organic C2-C6 acids.

Caucasian and East Asian cerumen contain many of the same VOCs, but differ significantly in the amounts produced.

Cerumen VOCs most likely result from bacterial and oxidative modification of secreted cerumen lipids.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. Jae Kwak for helpful discussions and Jason Eades for technical support. (KAP) acknowledges support from NIH-NIDCD Postdoctoral Training Grant 5T32DC0014 and the Army Research Office through grant #W911NF-11-1-0087 (GP).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Alvord LS, Farmer BL. J Am Acad Audiol. 1997;8:383–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shelley WB, Perry ET. J Invest Dermatol. 1956;26:13–22. doi: 10.1038/jid.1956.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwaab M, Gurr A, Neumann A, Dazert S, Minovi A. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;30:997–1004. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1185-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chai TJ, Chai TC. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1980;18:638–641. doi: 10.1128/aac.18.4.638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoon YJ, Jin Woo Park JW, Lee EJ. Acta Otolaryngol. 2008;128:871–875. doi: 10.1080/00016480701785020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsunaga E. Ann Hum Genet. 1962;25:273–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1962.tb01766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petrakis NL, Molohon KT, Tepper DJ. Science. 1967;158:1192–1193. doi: 10.1126/science.158.3805.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petrakis NL. Nature. 1969;222:1080–1081. doi: 10.1038/2221080a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshiura K, Kinoshita A, Ishida T, Ninokata A, Ishikawa T, Kaname T, Bannai M, Tokunaga K, Sonoda S, Komaki R, Ihara M, Saenko VA, Alipov GK, Sekine I, Komatsu K, Takahashi H, Nakashima M, Sosonkina N, Mapendano CK, Ghadami M, Nomura M, Liang DS, Miwa N, Kim DK, Garidkhuu A, Natsume N, Ohta T, Tomita H, Kaneko A, Kikuchi M, Russomando G, Hirayama K, Ishibashi M, Takahashi A, Saitou N, Murray JC, Saito S, Nakamura Y, Niikawa N. Nat Genet. 2006;38:324–330. doi: 10.1038/ng1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakano M, Miwa N, Hirano A, Yoshiura K, Niikawa N. BMC Genet. 2009;10:42. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-10-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin A, Saathoff M, Kuhn F, Max H, Terstegen L, Natsch A. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:529–540. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Preti G, Leyden JJ. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:344–346. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inoue Y, Mori T, Toyoda Y, Sakurai A, Ishikawa T, Mitani Y, Hayashizaki Y, Yoshimura Y, Kurahashi H, Sakai Y. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63:1369–1374. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2009.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akobjanoff L, Carruthers C, Senturia BH. J Invest Dermatol. 1954;23:43–50. doi: 10.1038/jid.1954.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haahti E, Nikkari T, Koskinen O. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1960;12:249–250. doi: 10.3109/00365516009062431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kataura A, Kataura K. Tohoku J Exp Med. 1967;91:227–237. doi: 10.1620/tjem.91.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aitzetmuller K, Koch J. J Chromatogr. 1978;145:195–202. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)81339-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harvey DJ. Biomed Environ Mass Spectrom. 1989;18:719–723. doi: 10.1002/bms.1200180912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bortz JT, Wertz PW, Downing DT. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23:845–849. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(90)70301-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okuda I, Bingham B, Stoney P, Hawke M. J Otolaryngol. 1991;20:212–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burkhart CN, Kruge MA, Burkhart CG, Black C. Otol Neurotol. 2001;22:715–722. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200111000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kocer M, Guldur T, Akarcay M, Miman MC, Beker G. J Laryngol Otol. 2008;122:881–886. doi: 10.1017/S0022215107000783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stransky K, Valterova I, Kofronova E, Urbanova K, Zarevucka M, Wimmer Z. Lipids. 2011;46:781–788. doi: 10.1007/s11745-011-3564-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vandendool H, Kratz PD. J Chromatogr. 1963;11:463–471. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)80947-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim JK, Cho JH. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2009;118:769–772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gallagher M, Wysocki CJ, Leyden JJ, Spielman AI, Sun X, Preti G. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:780–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08748.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ikeguchi N, Nihira T, Kishimoto A, Yamada Y. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:381–385. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.2.381-385.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wells JR, Morrison GC, Coleman BK. J ASTM Int. 2008;5:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coleman BK, Destaillats H, Hodgson AT, Nazaroff WW. Atmos Environ. 2008;42:642–654. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bernier UR, Kline DL, Barnard DR, Schreck CE, Yost RA. Anal Chem. 2000;72:747–756. doi: 10.1021/ac990963k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goldsmith LA. Physiology, biochemistry, and molecular biology of the skin. 2. Oxford University Press; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Labows JN, McGinley KJ, Leyden JJ, Webster GF. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1979;38:412–415. doi: 10.1128/aem.38.3.412-415.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Labows JN, Preti G, Hoelzle E, Leyden J, Kligman A. Steroids. 1979;34:249–258. doi: 10.1016/0039-128x(79)90077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zeng C, Spielman AI, Vowels BR, Leyden JJ, Biemann K, Preti G. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:6626–6630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pappas A, Fantasia J, Chen T. Dermatoendocrinol. 2013;5:319–324. doi: 10.4161/derm.25366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wesley NO, Maibach HI. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:843–860. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200304120-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cole DA, Maxwell SE, Arvey R, Salas E. Psycol Bull. 1994;115:465–474. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trumble SJ, Robinson EM, Berman-Kowalewski M, Potter CW, Usenko S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:16922–16926. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311418110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]