Abstract

Background

Artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) is the recommended first-line therapy for uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria worldwide but decreased artemisinin susceptibility, phenotypically characterized as slow parasite clearance time (PCT), has now been reported in Southeast Asia. This makes it all too important to measure the dynamics of parasite clearance in African patients treated with ACT over time, to understand trends and detect changes early enough to intervene

Methods

Individual patient data from 27 clinical trials of artesunate-amodiaquine (ASAQ) vs comparators conducted between 1999 and 2009 were analysed for parasite clearance on modified intent-to-treat (ITT) basis.

Results

Overall 15,017 patients treated for uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria at 44 sites in 20 sub-Saharan African countries were included in the analysis; 51% (n=7,660) vs 49% (n=7,357) were treated with ASAQ and comparator treatments, respectively. Seventy-seven per cent (77%) were children under six years of age. The proportion of the patients treated with ASAQ with persistent parasitaemia on Day 2 was 8.6%, and 1.5% on Day 3. Risk factor for not clearing parasites on Day 2 and Day 3 calculated by multivariate logistic regression with random effect on site and controlling for treatment were: high parasitaemia before treatment was (adjusted risk ratios (AOR) 2.12, 95% CI 1.91-2.35, AOR 2.43, 95% CI 1.98-3.00, respectively); non-ACT treatment (p=0.001, for all comparisons). Anaemia (p=0.001) was an additional factor for Day 2 and young age (p=0.005) for Day 3.

In patients treated with ASAQ in studies who had complete parasitaemia data every 24 hours up to Day 3 and additionally Day 7, the parasite reduction ratio was 93.9% by Day 1 and 99.9% by Day 2. Using the median parasitaemia before treatment (p0=27,125 μL) and a fitted model, the predicted PCT (pPCT = 3.614*ln (p0) – 6.135, r² = 0.94) in ASAQ recipients was 31 hours.

Conclusion

Within the period covered by these studies, rapid Plasmodium falciparum clearance continues to be achieved in Sub-Saharan African patients treated with ACT, and in particular with ASAQ. The prediction formula for parasite clearance time could be a pragmatic tool for studies with binary outcomes and once-daily sampling, both for research and monitoring purposes.

Background

Delayed Plasmodium falciparum response to artemisinin is reported in Southeast Asia, and may spread to other, more intensely malaria-endemic areas. Artemisinin compounds contribute rapid parasite killing and faster clearance to artemisinin-containing combination therapy (ACT). Artemisinin tolerance/resistance manifests itself with slower parasite clearance, while ACT remain generally effective both clinically and parasitologically [1-4]. Genomic studies are underway, which have generated so far two sets of putative markers of artemisinin resistance - K13-propeller polymorphism [5], and a SNP in the gene encoding a DNA repair protein RAD5 on chromosome 13 (and possibly also on chromosome 10) [6]. An in vitro assay (Ring Stage Assay) has also focused on the very early phases of the ring-stage parasite [7]. However, as of today, in the clinic as well as in the field the parasite clearance time (PCT) and its related clinical phenotype (delayed PCT) remain the best practical surrogates of artemisinin in vivo resistance [8]; the problem is that the frequent sampling (every six or eight hours) required to measure PCT accurately and to estimate the parasite clearance half-life [9] is practically difficult even in research settings. Easier methods are needed for both research and routine purposes. For example, failure to clear by Day 3 (72 hours post-treatment start) is proposed as a simple and accurate predictor of treatment failure [10], requiring a single time-point and thus limiting the workload in resource-limited settings.

Applying these and other measures both retrospectively and prospectively to commonly-used ACT will help understand trends and detect changes early enough to prompt effective responses to contain the spread of resistance. Artesunate-amodiaquine (ASAQ) is the second most commonly used ACT in the world (the first-line treatment in 22 out of 44 sub-Saharan African countries); more than 200 million treatments of ASAQ Winthrop have been distributed in Africa since the medication became available in 2007 [11-13]. While ASAQ is generally effective, the decreasing efficacy of AQ single-agent treatment have been reported in some sub-Saharan African settings [14,15]. Should artemisinin resistance occur there, it is expected to result soon in treatment failures, particularly in subjects with partial immunity, such as children in high-transmission areas, or patients of all ages in low-transmission areas. Monitoring ASAQ efficacy, particularly in these groups, has therefore become all the more important.

Greater understanding of factors influencing parasite clearance is crucial, and requires the analysis of pooled data from individual patient records. Therefore, this study collected and analysed a large sample (over 15,000 patients) of individual patient data (of whom approximately three-quarters were children under six years of age) from clinical trials conducted in sub-Saharan Africa between 1999 and 2009.

Studies such as this will help provide the foundations for further analyses of parasite clearance trends across sub-Saharan malaria-endemic countries.

Methods

Study sites, design and patients

The database was constructed from studies identified through a systematic review of clinical trials and personal contacts. To be included, efficacy or tolerability monitoring studies had to have been conducted in sub-Saharan Africa including any formulation of ASAQ to any other single or combination treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria (non-severe or non hyperparasitaemic) with follow-up of at least 28 days. For the studies meeting these criteria, investigators were contacted to provide individual patient data and the datasets received were examined for inclusion [16].

Study endpoints

Out of the 27 studies included (conducted between 1999 and 2009), three were multi-country studies [17-19], two studies compared ASAQ fixed and loose combination [20-22] and three studies were non-comparative (in Sierra Leone [23] and Senegal [24,25]). Details of the studies can be found elsewhere [26-40]. There was one unpublished study conducted in RDC (Cohuet, unpublished). The analysis of parasite clearance was by modified intent-to-treat (ITT), including all participants who were randomized and received the study medications. The primary endpoint in all the studies included in the analysis was parasitological efficacy, except one study about tolerability [22]. Follow-up ceased at the time of parasitological failure (either primary or recurrence), loss to follow-up, protocol violation and no data were recorded thereafter. Parasitaemia was recorded at enrolment (Day 0) and post-treatment from Day 1 through Day 28, but sampling schedules varied across studies during the first seven days, with Day 1 or Day 2 not recorded in all. Consecutive parasite slide results (Day 0, Day 1, Day 2, Day 3, Day 7) were available at 18 sites from five randomized controlled trials (RCT) [17-19,26,27].

Definitions and analyses

Table 1 summarizes the measures and analyses conducted. The risks of delayed parasite clearance by Day 2 and Day 3 and parasite clearance failure were analysed as binary variables using age (continuous in years), baseline parasitaemia (log transformed) as continuous variables, anaemia (binary variable, haemoglobin < 10 g/dL), study year (continuous) and study (categorical). The parasite reduction ratio on Day (n) was defined as: parasitaemia before treatment/parasitaemia on Day (n).

Table 1.

Definitions

| Measure | Definition | Population | Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parasite clearance |

Patients’ conversion from a positive to a negative parasite slide within 7 days post-treatment start (independent of whether it was sustained throughout the entire duration of follow-up or there was a recurrent episode). |

All studies, whether comparative or not (n = 15,017) |

Observed median time of parasite clearance |

| Delayed parasite clearance |

- Parasitaemia positive on |

Prevalence, risks by multivariate analysis |

|

|

o Day 2 | |||

|

o Day 3 | |||

| Parasite clearance failure |

- Day 2 parasitaemia > pre-treatment parasitaemia |

||

| - Day 3 parasitaemia >25% pre-treatment parasitaemia | |||

| - Consecutive positive slides up to Day 7 | |||

| Parasite reduction ratio |

Relative difference (referent: parasite before treatment) |

ASAQ groups (n = 2,355) where parasite densities were measured once daily from Days 0 to 3 and Day 7 |

Reduction rate |

| Predicted time of parasite clearance | Modelling the time of parasite clearance | Predict the time of parasite clearance using the parasitaemia before treatment and the proportions of positive patients |

The curve of the proportions of patients remaining parasitaemic during follow-up was fitted using logistic regression to give an estimate for clearance time. The fitted model for the logit of the proportion of parasitaemic patients over time and expressed in hours from the logistic regression:

In order to simplify the calculations of the predicted parasite clearance time ((pPCT), for a patient or a group of patients using the median time parasite clearance) the patient population was classed into ten pre-treatment parasite densities categories. A logistic model was fitted for each group and the corresponding predicted PCT was calculated, and once the results of predicted PCT for the ten groups were obtained, a simple logarithmic model was fitted with the aggregated results.

The risks, presented as adjusted risks ratios (AOR), were assessed by logistic multivariate analysis with random effect on the site in an attempt to account for potential statistical heterogeneity while controlling for age (continuous), parasitaemia before treatment (log-transformed), anaemia (binary), and year (continuous). Categorical data were compared using the Chi-square or the Fisher exact test as appropriate. The Spearman test was used to analyse the relationship between clearance reduction and pre-treatment parasitaemia. Confidence intervals (CI) were calculated at 95% and statistical significance was set at p-value <0.05.

Ethical issues

All studies had been approved by the relevant ethics and institution review committees as reported in the individual papers.

ASAQ treatment regimens

The majority of the patients were treated with individually formulated AS and AQ. The target dose was AS 12 mg/kg over three days and AQ 30 mg/kg over three days except in Uganda where AQ was given at 25 mg/kg (Day 0: 10 mg/kg, Day 1: 10 mg/kg, Day 2: 5 mg/kg). The loose combinations of ASAQ were dosed based on body weight, while in four studies the fixed dose combination (FDC) ASAQ was based on age and weight range [19-22]. The FDC was also given either once or twice a day [19].

ASAQ FDC (Coarsucam™ Winthrop® Sanofi Aventis); AS 25 mg/AQ 67.5 mg one tab/day for three days in children 5–8.9 kg; AS 50 mg/AQ 135 mg one tab/day for three days in children 9–17.9 kg; AS 100 mg/AQ 270 mg one tab/day for three days in children 18–35.9 kg.

Comparator treatment regimens

i. ACT: artemether-lumefantrine (AL)(20 mg artemether/120 mg lumefantrine) given according to weight as one (5–14 kg), two (15–24 kg), three (25–34 kg), and four (≥35 kg) tablets given twice daily co-administrated with fat for three days; Coartem™, Novartis); dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine (DP) was given once daily over three days, at the standard dosage of 2.25 mg/kg and 18 mg/kg of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine, respectively, rounded up to the nearest half tablet (two formulations were used: 20 mg dihydroartemisinin + 160 mg piperaquine and 40 mg dihydroartemisinin +20 mg piperaquine, Eurartesim™, Sigma-Tau, and in Rwanda, Artekin™, Holley); AS + sulphadoxine- pyrimethamine (SP)(AS 4 mg/kg/day; SP 25 mg/kg of sulphadoxine and 1.25 mg/kg of pyrimethamine administered in a co-formulated tablet as a single dose);

ii. Non-ACT: AQ + SP (AQ 10 mg/kg/day for three days and SP 25 mg/kg of sulphadoxine and 1.25 mg/kg of pyrimethamine administered in a co-formulated tablet (SP) as a single dose); chloroquine (CQ)(25 mg/kg over three days) and SP; AQ monotherapy (10 mg/kg/day for three days); AS monotherapy (AS 12 mg/kg over five days).

Results

Overall 15,017 patients treated for uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria at 44 sites in 20 sub-Saharan African countries were included in the analysis (Figure 1). The proportion of patients treated with ASAQ was 51% (n = 7,660) vs 49% (n = 7,357) on comparator treatments; 31% (4,848/15,017) of the patients had complete parasitaemia data every 24 hours up to Day 3 and then Day 7 (2,355 in ASAQ and 3,493 in comparator groups). Overall, the proportion of children under six years of age was 77%, and the overall geometric mean parasitaemia pre-treatment was 16,964/μL (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Flow chart, number of patients with parasitaemia results and daily results from Day 0 to Day 3 and Day 7.

Table 2.

Patients at enrolment

|

Year |

Site |

Total |

Under six years old |

Treatment |

Parasitaemia |

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | ASAQ (n) | Comparator (n) | μL | Anaemia (%) | |||

| 2004 |

Angola-Caala 2004 |

137 |

137 |

100 |

69 |

68 |

29,180 |

28 |

| 2003 |

Angola-Kuito 2003 |

187 |

187 |

100 |

97 |

90 |

19,216 |

61 |

| 2008 |

Burkina faso - Nanoro 2008 |

810 |

810 |

100 |

295 |

515 |

20,831 |

83 |

| 2005 |

Burkina Faso Puytenga 2005 |

890 |

824 |

93 |

890 |

NA |

15,210 |

76 |

| 2006 |

Cameroon 2006 |

166 |

79 |

48 |

110 |

56 |

24,627 |

8 |

| 2004 |

Congo-Kindamba 2004 |

298 |

298 |

100 |

101 |

197 |

25,890 |

64 |

| 2008 |

Gabon - 2008 |

226 |

226 |

100 |

80 |

146 |

22,265 |

69 |

| 1999 |

Gabon 1999 |

220 |

119 |

54 |

110 |

110 |

22,537 |

NA |

| 2004 |

Guinee-Dabola 2004 |

220 |

220 |

100 |

110 |

110 |

37,493 |

73 |

| 1999 |

Kenya 1999 |

400 |

346 |

87 |

200 |

200 |

31,095 |

61 |

| 2009 |

Kenya 2009 |

54 |

0 |

0 |

54 |

NA |

12,181 |

2 |

| 2009 |

Liberia 2009 |

1300 |

302 |

23 |

648 |

652 |

1,340 |

11 |

| 2006 |

Madagascar 2006 |

179 |

76 |

42 |

119 |

60 |

9,159 |

19 |

| 2004 |

Mali Bancouna 2004 |

753 |

714 |

95 |

252 |

501 |

15,468 |

44 |

| 2006 |

Mali Bougoula 2006 |

203 |

134 |

66 |

135 |

68 |

22,183 |

51 |

| 2008 |

Mozambique - Manhica 2008 |

420 |

420 |

100 |

210 |

210 |

39,023 |

62 |

| 2008 |

Nigeria - Afokang 2008 |

261 |

261 |

100 |

92 |

169 |

18,361 |

72 |

| 2008 |

Nigeria - Pamol 2008 |

233 |

233 |

100 |

82 |

151 |

18,177 |

73 |

| 2003 |

RDC Boende 2003 |

279 |

279 |

100 |

136 |

143 |

24,170 |

57 |

| 2002 |

Rwanda Mashesha 2002 |

122 |

122 |

100 |

61 |

61 |

14,729 |

45 |

| 2004 |

Rwanda Mashesha 2004 |

269 |

269 |

100 |

89 |

180 |

20,454 |

39 |

| 2002 |

Rwanda Rukara 2002 |

95 |

95 |

100 |

49 |

46 |

25,855 |

40 |

| 2004 |

Rwanda Rukara 2004 |

270 |

269 |

100 |

89 |

181 |

36,868 |

31 |

| 2002 |

Rwanda-Kicukiro 2002 |

91 |

91 |

100 |

48 |

43 |

13,457 |

31 |

| 2004 |

Rwanda-Kicukiro 2004 |

223 |

223 |

100 |

74 |

149 |

36,515 |

28 |

| 2000-5 |

Sen-Djembeye 2000-5 |

137 |

18 |

13 |

137 |

|

25,992 |

8 |

| 1999 |

Senegal 1999 |

321 |

123 |

38 |

160 |

161 |

40,386 |

NA |

| 2006 |

Senegal 2006 |

392 |

11 |

3 |

264 |

128 |

7,991 |

47 |

| 2000-5 |

Sen-Mlomp 2000-5 |

723 |

74 |

10 |

723 |

NA |

46,328 |

3 |

| 2000-5 |

Sen-Oussouye 2000-5 |

208 |

106 |

51 |

208 |

NA |

19,142 |

NA |

| 2004 |

Sierra Leone Kailahun 2004 |

126 |

126 |

100 |

126 |

NA |

27,116 |

56 |

| 2003 |

South Sudan Nuba 2003 |

161 |

161 |

100 |

80 |

81 |

21,964 |

31 |

| 2003 |

Sudan Malakal 2003 |

269 |

269 |

100 |

134 |

135 |

22,881 |

86 |

| 2008 |

Uganda - Mbarara 2008 |

319 |

319 |

100 |

160 |

159 |

23,431 |

51 |

| 2003 |

Uganda Amudat 2003 |

212 |

212 |

100 |

106 |

106 |

18,410 |

49 |

| 2004 |

Uganda Tororo 2004 |

541 |

508 |

94 |

194 |

347 |

18502 |

71% |

| 2005 |

Uganda Tororo 2005 |

408 |

388 |

95 |

204 |

204 |

21,480 |

40 |

| 2004 |

Uganda-Apac-2004 |

542 |

516 |

95 |

174 |

368 |

11,701 |

64 |

| 2004 |

Uganda-Arua-2004 |

534 |

509 |

95 |

174 |

360 |

23,927 |

63 |

| 2003 |

Uganda-Jinja-2003 |

543 |

370 |

68 |

189 |

354 |

34,337 |

40 |

| 2006 |

Uganda-Kampala-2006 |

730 |

358 |

49 |

242 |

488 |

10,581 |

11 |

| 2008 |

Zambia - Ndola 2008 |

245 |

245 |

100 |

85 |

160 |

36,401 |

85 |

| 2002 |

Zanzibar Kivunge 2002 |

297 |

296 |

100 |

148 |

149 |

16,500 |

78 |

| 2002 |

Zanzibar Micheweni 2002 |

105 |

105 |

100 |

54 |

51 |

16,777 |

87 |

| Total | 15017 | 11550 | 77 | 7660 | 7357 | 16,964 | 50 | |

Legend: NA, non-applicable.

Parasitaemia on Day 2 and Day 3

Delayed parasite clearance, defined as the proportion of patients still parasitaemic on Day 2 or Day 3 (analysed as a binary variable) under ASAQ treatment in comparative and non-comparative trials was analysed in 44 sub-Saharan African sites over the period 1999–2009.

The proportion of patients on ASAQ who were still parasitaemic on Day 2 was 8.6% (603/7,020, 95% CI 7.9-9.3%) and ranged from 1.0% in Burkina Faso-Nanoro (2008) and Congo-Kindamba (2004) to 57.1% in DRC-Boende in 2003 (Additional file 1: Table S1). Using multivariate logistic regression with random effect on site and controlling for treatment, the risk factors for a patient to remain positive on Day 2 were higher parasitaemia before treatment (AOR 2.12, 95% CI 1.91-2.35, p = 0.001) and anaemia (AOR 1.22, 95% CI 1.07-1.38, p = 0.001); no significant difference in the risk of being parasitaemic on Day 2 was detected in RCT comparing ASAQ to other ACT: AL (p = 0.245), DP (p = 0.762), AS + SP (p = 0.291), whereas patients treated with non-ACT were at higher risk: AQ + SP (AOR 14.53, 95% CI 11.36-18.59, p = 0.001), CQ + SP (AOR 20.10, 95% CI 15.07-26.82, p = 0.001), or AQ (AOR 21.63, 95% CI 12.73-36.75, p = 0.001).

The proportion of patients treated with ASAQ who were still parasitaemic on Day 3 was 1.5% (116/7,550, 95% CI 1.2-1.8%, of whom 44 in RDC-Boende), ranging from 0% in many various sites across sub-Saharan Africa to 55.9% in DRC-Boende. Using multivariate logistic analysis with random effects on sites, younger patients (AOR 0.94, 95% CI 0.90-0.98, p = 0.005) and patients with higher parasitaemia at enrolment (AOR 2.43, 95% CI 1.98-3.00, p = 0.001) were at higher risk of remaining parasitaemic on Day 3. Compared to ASAQ, the risk of being parasitaemic on Day 3 was higher for patients treated with a non-ACT: AQ + SP (AOR 15.70, 95% CI 7.43-33.16, p = 0.001), AQ (AOR 16.38, 95% CI 7.82-34.34, p = 0.001), CQ + SP (AOR 72.56, 95% CI 33.70-156.23, p = 0.001), while no significant difference was detected with other ACT (AL, p = 0.993; DP, p = 0.525; AS + SP, p = 0.190) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Delayed parasitaemia (Day 3) forest plot, artesunate/amodiaquine vs comparator treatments. AL: artemether-lumefantrine; AOR: adjusted odds ratio using multivariate logistic regression with random effects; AQ: amodiaquine; AS: artesunate; CQ: chloroquine; DP: dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine; fdc: fixed dose combination; na: not applicable; SP: sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine.

Parasite clearance failure

Overall, patients treated with an ACT were at lower risk of parasite clearance failure by Day 7 (AOR 0.03, 95% CI 0.01-0.12, p = 0.001, stratified by site) compared to non-ACT (Table 3). The proportion of patients treated with ASAQ who had a parasite clearance failure was 0.2% (15/7,550, 95% CI 0.1-0.3%), mostly from one site (RDC-Boende). Using multivariate analysis with random effect on site, higher parasitaemia at enrolment (AOR 2.31, 95% CI 1.60-3.35, p = 0.001) was the only risk detected for parasite clearance failure.

Table 3.

Proportion of patients with a parasite clearance failure by Day 7 and by treatment groups

|

Treatment |

Parasite clearance failure (number) |

Total number of patients |

Parasite clearance failure |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion % | 95% CI lower bound | 95% CI upper bound | |||

| ASAQ |

15 |

7,660 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.3 |

| AL |

3 |

2,391 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

0.4 |

| DP |

1 |

1,132 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

0.5 |

| AS + SP |

26 |

1,005 |

2.6 |

1.7 |

3.8 |

| AQ |

23 |

621 |

3.7 |

3.7 |

7.4 |

| AQ + SP |

9 |

1,257 |

0.7 |

0.3 |

1.3 |

| AS |

0 |

252 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

1.5 |

| CQ + SP |

78 |

699 |

11.2 |

8.9 |

13.7 |

| Total | 153 | 15,017 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.2 |

Parasite reduction ratio

Overall, in studies treating with ASAQ and recording daily parasitaemia (n = 2,355), the parasite reduction ratio (parasitaemia before treatment/parasitaemia on day (n)) was 93.9% by Day 1 and 99.9% by Day 2 (Table 4). The parasite reduction ratio ranged on Day 1 from 77.1% in Mozambique to 99.2% in Kenya with a significant correlation between clearance reduction on Day 1 and pre-treatment parasitaemia (r = 0.098, p = 0.001, Spearman test, individual data).

Table 4.

Clearance reduction, artesunate/amodiaquine groups

| Country site |

Parasitaemia, geometric mean |

N |

Parasite reduction ratio (individual data) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d1/d0 | d2/d0 | d3/d0 | d7/d0 | |||

| Burkina faso - Nanoro 2008 |

21,185 |

295 |

97.8% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

| Cameroon 2006 |

24,129 |

110 |

97.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

| Gabon - Fougamou 2008 |

21,117 |

80 |

98.6% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

| Gabon 1999 |

20,867 |

108 |

98.2% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

| Kenya 1999 |

30,040 |

199 |

94.5% |

99.9% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

| Kenya 2009 |

12,193 |

54 |

99.2% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

| Madagascar 2006 |

9,648 |

119 |

98.9% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

| Mali Bougoula 2006 |

23,744 |

135 |

93.8% |

99.9% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

| Mozambique - Manhica 2008 |

35,924 |

210 |

77.1% |

99.8% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

| Nigeria - Afokang 2008 |

20,326 |

92 |

96.3% |

99.7% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

| Nigeria - Pamol 2008 |

17,329 |

82 |

97.9% |

99.8% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

| Senegal 1999 |

41,753 |

160 |

89.5% |

99.8% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

| Senegal 2006 |

20,201 |

264 |

91.4% |

99.7% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

| Uganda - Mbarara 2008 |

27,262 |

160 |

98.4% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

| Zambia - Ndola 2008 |

35,887 |

85 |

91.9% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

| Zanzibar Kivunge 2002 |

20,625 |

148 |

95.7% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

| Zanzibar Micheweni 2002 |

18,236 |

54 |

95.2% |

99.7% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

| Total | 23,596 | 2355 | 93.9% | 99.9% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

Predicted time of parasite clearance

The number of patients included in RCT at 17 sites with complete parasitaemia record (every 24 hours from Day 0 to Day 3 plus Day 7) was 4,848 of whom 2,355 were treated with ASAQ and 2,493 with a comparator drug.

Using logistic regression, the predicted time of parasite clearance was overall ≈ 31 hours for a median baseline parasitaemia of 27,125/μL, ranging from ≈ 19 hours for patients with parasitaemia before treatment <2,500/μL to ≈ 37 hours for patients with parasitaemia >100,000/μL (Table 5).

Table 5.

Predicted parasite clearance time by groups of parasitaemia before treatment and intervals, artesunate/amodiaquine treatment

|

Parasitaemia at enrolment (μL) |

N |

Median |

|

Observed |

|

|

|

pPCT |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 7 | hour | Lower bound | Upper bound | |||

| <2,500 |

110 |

2,030 |

100% |

24% |

2% |

1% |

0% |

19.0 |

NA |

NA |

| 2,500-5,000 |

227 |

3,680 |

100% |

44% |

7% |

1% |

0% |

24.4 |

21.7 |

26.7 |

| 5,000-10,000 |

294 |

7,290 |

100% |

58% |

10% |

1% |

0% |

28.2 |

23.8 |

32.5 |

| 10,000-20,000 |

361 |

14,261 |

100% |

65% |

6% |

1% |

0% |

29.1 |

25.1 |

36.2 |

| 20,000-30,000 |

261 |

25,044 |

100% |

68% |

10% |

0% |

0% |

30.8 |

25.7 |

35.8 |

| 30,000-50,000 |

362 |

39,250 |

100% |

73% |

9% |

1% |

0% |

31.6 |

27.2 |

37.1 |

| 50,000-75,000 |

252 |

61,372 |

100% |

75% |

12% |

2% |

0% |

32.9 |

26.8 |

37.5 |

| 75,000-100,000 |

159 |

86,925 |

100% |

79% |

13% |

0% |

0% |

34.0 |

29.8 |

39.9 |

| >100,000 |

329 |

144,357 |

100% |

84% |

18% |

3% |

1% |

37.3 |

33.1 |

40.7 |

| TOTAL | 2,355 | 27,125 | 100% | 67% | 10% | 1% | 0% | 30.8 | 25.8 | 41.8 |

Legend: pPCT, predicted parasite clearance time.

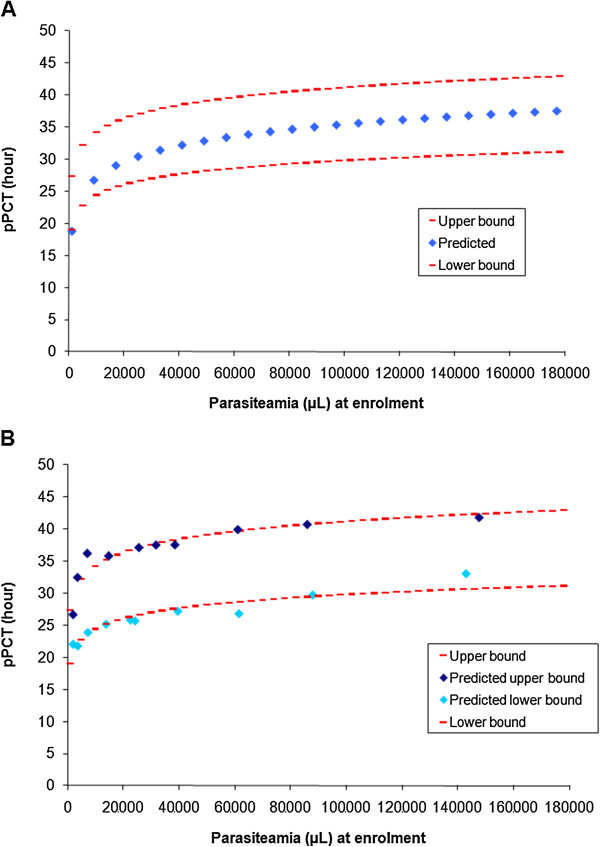

Using the predicted PCT from the ten categories of levels of baseline parasitaemia, a logarithmic relationship was detected between the observed median baseline parasitaemia and the corresponding predicted PCT (Figure 3A). The fitted curve was a logarithmic relationship defined by:

Figure 3.

Fitted curve of parasite clearance and intervals, artesunate/amodiaquine treatment. A: pPCT, predicted parasite clearance time. B: pPCT, predicted parasite clearance time.

The lower and upper bounds of the interval were fitted using sites where the overall proportion of parasitaemic patients were <10% on Day 2 for the lower bound and >10% for the upper bound with a coefficient of determination (r2) of 0.88 for both adjustments (Figure 3B). The 10% threshold was in keeping with WHO recommendations [41].

Discussion

This individual patient data analysis of parasite clearance was conducted on a large sample (n ~15,000) of uncomplicated malaria treatments (predominantly paediatric; three-quarters less than six years old) from 44 sites and 20 sub-Saharan African countries with different levels of endemicity, covering the decade 1999–2009.

This analysis shows that rapid Plasmodium falciparum clearance continues to be achieved in sub-Saharan African patients treated with ACT, and in particular with ASAQ, although direct within-site comparisons are not available; it has therefore benchmarking value as reference for future studies. This study also presents a prediction formula for PCT as a pragmatic tool adapted for studies with binary data (not quantitating parasite densities) and once-daily sampling, such as those that would be done at the typical study site in peripheral settings and in routine surveillance by control programmes. This prediction could apply to groups of patients as well as to the individual patient.

These results confirm the correlation between pre-treatment parasitaemia and PCT [10], and offer an easy way to calculate the typical PCT (in hour) using parasitaemia before treatment (p0) with ASAQ or other equivalent treatments (pPCT = 3.614*ln(p0) – 6.135, r2 = 0.94). There was also a (weaker) correlation between parasitaemia before treatment and the parasite reduction ratio (PRR) at 24 h.

Monitoring treatment response and detecting artemisinin resistance as early as possible have become a major issue in malaria control. The rate at which treatment clears parasites within the first few days is at present the most useful practical test for ACT, as early response to treatment relies predominantly on the parasite response to artemisinin, independent of whether parasites are later cleared for good through the combination of the longer-lived companion drug and the host’s immune response.

The present analysis focused on initial response to ACT treatment, as a proxy for artemisinin resistance and failure, and aimed to identify variables that were independently associated with persistent parasitaemia on Days 2 and 3 in settings where artemisinin resistance has probably not yet emerged.

Within the period covered by these studies, there was no indication of delayed response to ACT. ACT cleared parasites rapidly leaving very few patients with a low parasitaemia on Day 3 (first day after the completion of the three-day ACT regimen). In particular, with ASAQ the parasite reduction ratio was 93.9% by Day 1 and 99.9% by Day 2; only 1.5% of the patients were still positive on Day 3 (against a proposed threshold of 3% indicating delayed response [10]). These data confirm that pre-treatment parasitaemia is a risk factor for failing to clear parasites on Day 2 and 3. They also show a clear contribution of artemisinins to the speed of action: ACT performed significantly better than non-ACT (whether combinations or single-agent treatments); no difference was detected between ACT (whether the artemisinin derivative was artesunate, artemether or dihydroartemisinin).

Anaemia was an additional risk factor for failing to clear parasites by Day 2; younger patient’s age for Day 3. The only exception was the study conducted in DRC-Boende (Cohuet, unpublished) which had a high proportion of parasite clearance failures with both ASAQ and AL. These findings are difficult to explain and should be taken with caution, but one cannot exclude that there might also have been a focus of resistant Plasmodium falciparum in the DRC. No subsequent studies are available to confirm or belie this original study. Understanding the dynamics of parasite clearance could help detect early signs of artemisinin resistance and distinguish biologically meaningful changes in early parasite clearance over time from changes that may be due to the role of effect modifiers like higher pre-treatment parasitaemia, young age and anaemia by applying multivariate analysis.

Consistently with previous results [10] and the first-order process of parasite clearance, there was a logarithmic correlation between patients’ pre-treatment parasitaemia and their pPCT; while developed using ASAQ data, it was applied satisfactorily to other ACT within this database as well as other studies. For example, in a study conducted in Mali [42] where parasitaemia was tested with frequent screenings (every eight hours) in patients treated for uncomplicated P. falciparum with artesunate for seven days and where there was no evidence of delayed parasitaemia, the median parasitaemia at enrolment (P0) was 27,070 μL and the observed median time of parasite clearance was 32 hours. Applying the suggested method using the logarithmic correlation found in the present paper (pPCT = 3.614*ln(P0) – 6.135) gave very similar results (30.8 hours with intervals of 26.8 to 37.3 hours).

This simple method was tested to predict a “typical” PCT in situations when resistance has not emerged. However, this estimation of the predicted time to parasite clearance is not without its limitations. The calculations may lack precision with studies sampling once a day and at variable intervals from treatment intake (as it might be the case for most clinical trials, especially on the first day). It has been suggested that parasite clearance rate can only be accurately estimated if sampling is at least every six hours [43]; it is thus possible that data could have been “over-analysed” in generating predicted time of parasite clearance in this case. Although parasite clearance half-life is the research reference to define slow parasite clearance, sampling patients four times or even twice a day is not feasible in routine monitoring, and might be cumbersome even in research settings. Detecting the first signs of artemisinin resistance in uncomplicated P. falciparum will likely require a combination of more sophisticated studies and routine monitoring. Between parasite clearance estimators [9] and Day 3 persistency [10], simple estimations of PCT based on daily sampling may add elements to facilitate comparisons and detection of trends. It would be useful to compare methods for validation, including databases with delayed responses.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JZ and PO designed the analysis, interpreted the data and prepared the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Proportion by site of patients still parasitaemic on Day 1, Day 2, Day 3, and parasite clearance failure, ASAQ groups.

Contributor Information

Julien Zwang, Email: zwang@free.fr.

Grant Dorsey, Email: gdorsey@medsfgh.ucsf.edu.

Andreas Mårtensson, Email: Andreas.Martensson@ki.se.

Umberto d’Alessandro, Email: udalessandro@mrc.gm.

Jean-Louis Ndiaye, Email: jlndiaye@yahoo.com.

Corine Karema, Email: ckarema@gmail.com.

Abdoulaye Djimde, Email: adjimde@icermali.org.

Philippe Brasseur, Email: brasseur@ird.fr.

Sodiomon B Sirima, Email: s.sirima.cnlp@fasonet.bf.

Piero Olliaro, Email: olliarop@who.int.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the patients and staff at all trial sites who participated in these trials. We would like to thank Epicentre, Paris, France, for sharing the datasets [23,29-32,34-36] and all the principal investigators of the other studies. JZ received a grant from DNDi (Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative) to do this analysis. DNDi sponsored four of the trials [19-22] but had no role in the design and conduct of the analysis, interpretation of results of the manuscript. The Mali study was supported by European and Developing Countries Clinical Trial Partnership (EDCTP) fellowship (Grant to AAD # 2004.2.C.f1) and by Sanofi Aventis (ARTEN-L-00848) who provided the monitoring services, the study insurance, the study drugs, and the biological parameters assessment machines.

Disclaimer

PO is a staff member of the WHO; the authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this publication and they do not necessarily represent the decisions, policy or views of the WHO.

References

- Amaratunga C, Sreng S, Suon S, Phelps ES, Stepniewska K, Lim P, Zhou C, Mao S, Anderson JM, Lindegardh N, Jiang H, Song J, Su XZ, White NJ, Dondorp AM, Anderson TJ, Fay MP, Mu J, Duong S, Fairhurst RM. Artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum in Pursat province, western Cambodia: a parasite clearance rate study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:851–858. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70181-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkowski B, Khim N, Chim P, Kim S, Ke S, Kloeung N, Chy S, Duong S, Leang R, Ringwald P, Dondorp AM, Tripura R, Benoit-Vical F, Berry A, Gorgette O, Ariey F, Barale JC, Mercereau-Puijalon O, Menard D. Reduced artemisinin susceptibility of Plasmodium falciparum ring stages in western Cambodia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:914–923. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01868-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dondorp AM, Nosten F, Yi P, Das D, Phyo AP, Tarning J, Lwin KM, Ariey F, Hanpithakpong W, Lee SJ, Ringwald P, Silamut K, Imwong M, Chotivanich K, Lim P, Herdman T, An SS, Yeung S, Singhasivanon P, Day NP, Lindegardh N, Socheat D, White NJ. Artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:455–467. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrara VI, Zwang J, Ashley EA, Price RN, Stepniewska K, Barends M, Brockman A, Anderson T, McGready R, Phaiphun L, Proux S, van Vugt M, Hutagalung R, Lwin KM, Phyo AP, Preechapornkul P, Imwong M, Pukrittayakamee S, Singhasivanon P, White NJ, Nosten F. Changes in the treatment responses to artesunate-mefloquine on the northwestern border of Thailand during 13 years of continuous deployment. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4551. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariey F, Witkowski B, Amaratunga C, Beghain J, Langlois AC, Khim N, Kim S, Duru V, Bouchier C, Ma L, Lim P, Leang R, Duong S, Sreng S, Suon S, Chuor CM, Bout DM, Ménard S, Rogers WO, Genton B, Fandeur T, Miotto O, Ringwald P, Le Bras J, Berry A, Barale JC, Fairhurst RM, Benoit-Vical F, Mercereau-Puijalon O, Ménard D. A molecular marker of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature. 2014;505:50–55. doi: 10.1038/nature12876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkowski B, Amaratunga C, Khim N, Sreng S, Chim P, Kim S, Lim P, Mao S, Sopha C, Sam B, Anderson JM, Duong S, Chuor CM, Taylor WR, Suon S, Mercereau-Puijalon O, Fairhurst RM, Menard D. Novel phenotypic assays for the detection of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Cambodia: in-vitro and ex-vivo drug-response studies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:1043–9. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70252-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takala-Harrison S, Clark TG, Jacob CG, Cummings MP, Miotto O, Dondorp AM, Fukuda MM, Nosten F, Noedl H, Imwong M, Bethell D, Se Y, Lon C, Tyner SD, Saunders DL, Socheat D, Ariey F, Phyo AP, Starzengruber P, Fuehrer HP, Swoboda P, Stepniewska K, Flegg J, Arze C, Cerqueira GC, Silva JC, Ricklefs SM, Porcella SF, Stephens RM, Adams M. et al. Genetic loci associated with delayed clearance of Plasmodium falciparum following artemisinin treatment in Southeast Asia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:240–245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211205110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das D, Price RN, Bethell D, Guerin PJ, Stepniewska K. Early parasitological response following artemisinin-containing regimens: a critical review of the literature. Malar J. 2013;12:125. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegg JA, Guerin PJ, White NJ, Stepniewska K. Standardizing the measurement of parasite clearance in falciparum malaria: the parasite clearance estimator. Malar J. 2011;10:339. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepniewska K, Ashley E, Lee SJ, Anstey N, Barnes KI, Binh TQ, D’Alessandro U, Day NP, de Vries PJ, Dorsey G, Guthmann JP, Mayxay M, Newton PN, Olliaro P, Osorio L, Price RN, Rowland M, Smithuis F, Taylor WR, Nosten F, White NJ. In vivo parasitological measures of artemisinin susceptibility. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:570–579. doi: 10.1086/650301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanofi and DNDi Celebrate Six Years of Collaboration in Fighting Malaria by Distributing 200 Million Treatments of ASAQ. http://www.dndi.org/media-centre/press-releases/1591-sanofi-dndi-distributed-20-million-treatments-asaq.html.

- WHO African Region. Country Antimalarial Drug Policies. http://www.who.int/malaria/am_drug_policies_by_region_afro/en/index.html.

- Country Antimalarial Drug Policies. http://www.who.int/malaria/am_drug_policies_by_region_emro/en/index.html.

- Zwang J, Olliaro P, Barennes H, Bonnet M, Brasseur P, Bukirwa H, Cohuet S, D’Alessandro U, Djimdé A, Karema C, Guthmann JP, Hamour S, Ndiaye JL, Mårtensson A, Rwagacondo C, Sagara I, Same-Ekobo A, Sirima SB, van den Broek I, Yeka A, Taylor WR, Dorsey G, Randrianarivelojosia M. Efficacy of artesunate-amodiaquine for treating uncomplicated falciparum malaria in sub-Saharan Africa: a multi-centre analysis. Malar J. 2009;8:203. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair D, Zani B, Donegan S, Olliaro P, Garner P. Artemisinin-based combination therapy for treating uncomplicated malaria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;8:CD007483. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007483.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juni B, Altman DG, Egger M. Systematic reviews of healthcare: assessing the quality of controlled clinical trials. BMJ. 2001;323:42–46. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7303.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Four Artemisinin-Based Combinations (4ABC) Study Group. A head-to-head comparison of four artemisinin-based combinations for treating uncomplicated malaria in African children: a randomized trial. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001119. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adjuik M, Agnamey P, Babiker A, Borrmann S, Brasseur P, Cisse M, Cobelens F, Diallo S, Faucher JF, Garner P, Gikunda S, Kremsner PG, Krishna S, Lell B, Loolpapit M, Matsiegui PB, Missinou MA, Mwanza J, Ntoumi F, Olliaro P, Osimbo P, Rezbach P, Some E, Taylor WR. Amodiaquine-artesunate versus amodiaquine for uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in African children: a randomised, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1365–1372. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08348-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ndiaye JL, Randrianarivelojosia M, Sagara I, Brasseur P, Ndiaye I, Faye B, Randrianasolo L, Ratsimbasoa A, Forlemu D, Moor VA, Traore A, Niawanlou Dara YD, Lameyre V, Diallo M, Djimde A, Same-Ekobo A, Gaye O. Randomized, multicentre assessment of the efficacy and safety of ASAQ – a fixed-dose artesunate-amodiaquine combination therapy in the treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Malar J. 2009;8:125. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirima SB, Tiono AB, Gansane A, Diarra A, Ouedraogo A, Konate AT, Kiechel JR, Morgan CC, Olliaro PL, Taylor WR. The efficacy and safety of a new fixed-dose combination of amodiaquine and artesunate in young African children with acute uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum. Malar J. 2009;8:48. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schramm B, Valeh P, Baudin E, Mazinda CS, Smith R, Pinoges L, Dhorda M, Boum Y 2nd, Sundaygar T, Zolia YM, Jones JJ, Comte E, Houzé P, Jullien V, Carn G, Kiechel JR, Ashley EA, Guérin PJ. Efficacy of artesunate-amodiaquine and artemether-lumefantrine fixed-dose combinations for the treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria among children aged six to 59 months in Nimba County, Liberia: an open-label randomized non-inferiority trial. Malar J. 2013;12:251. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schramm B, Valeh P, Baudin E, Mazinda CS, Smith R, Pinoges L, Sundaygar T, Zolia YM, Jones JJ, Comte E, Bruneel A, Branger M, Jullien V, Carn G, Kiechel JR, Ashley EA, Guérin PJ. Tolerability and safety of artesunate-amodiaquine and artemether-lumefantrine fixed dose combinations for the treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria: two open-label, randomized trials in Nimba County, Liberia. Malar J. 2013;12:250. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandesso F, Hagerman A, Kamara K, Lam E, Checchi F, Balkan S, Scollo G, Durand R, Guthmann JP. Low efficacy of the combination artesunate plus amodiaquine for uncomplicated falciparum malaria among children under 5 in Kailahun, Sierra Leone. Trop Med Int Health. 2006;11:1017–1021. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agnamey P, Brasseur P, Cisse M, Gaye O, Dumoulin J, Rigal J, Taylor WR, Olliaro P. Economic evaluation of a policy change from single-agent treatment for suspected malaria to artesunate-amodiaquine for microscopically confirmed uncomplicated falciparum malaria in the Oussouye District of south-western Senegal. Trop Med Int Health. 2005;10:926–933. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brasseur P, Agnamey P, Gaye O, Vaillant M, Taylor WR, Olliaro PL. Efficacy and safety of artesunate plus amodiaquine in routine use for the treatment of uncomplicated malaria in Casamance, southern Senegal. Malar J. 2007;6:150. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-6-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martensson A, Stromberg J, Sisowath C, Msellem MI, Gil JP, Montgomery SM, Olliaro P, Ali AS, Björkman A. Efficacy of artesunate plus amodiaquine versus that of artemether-lumefantrine for the treatment of uncomplicated childhood Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Zanzibar, Tanzania. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1079–86. doi: 10.1086/444460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djimdé AA, Fofana B, Sagara I, Sidibe B, Toure S, Dembele D, Dama S, Ouologuem D, Dicko A, Doumbo OK. Efficacy, safety, and selection of molecular markers of drug resistance by two ACTs in Mali. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;78:455–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey G, Staedke S, Clark TD, Njama-Meya D, Nzarubara B, Maiteki-Sebuguzi C. Combination therapy for uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Ugandan children: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2007;297:2210–2209. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.20.2210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet M, Roper C, Felix M, Coulibaly L, Kankolongo GM, Guthmann JP. Efficacy of anti-malarial treatment in Guinea: in vivo study of two artemisinin combination therapies in Dabola and molecular markers of resistance to sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine in N’Zerekore. Malar J. 2007;6:54. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-6-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swarthout TD, van den Broek IV, Kayembe G, Montgomery J, Pota H, Roper C. Artesunate + amodiaquine and artesunate + sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine for treatment of uncomplicated malaria in Democratic Republic of Congo: a clinical trial with determination of sulphadoxine and pyrimethamine-resistant haplotypes. Trop Med Int Health. 2006;11:1503–1511. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Broek I, Kitz C, Al Attas S, Libama F, Balasegaram M, Guthmann JP. Efficacy of three artemisinin combination therapies for the treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in the Republic of Congo. Malar J. 2006;5:113. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-5-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthmann JP, Cohuet S, Rigutto C, Fortes F, Saraiva N, Kiguli J, Kyomuhendo J, Francis M, Noël F, Mulemba M, Balkan S. High efficacy of two artemisinin-based combinations (artesunate + amodiaquine and artemether + lumefantrine) in Caala, Central Angola. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;75:143–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karema C, Fanello CI, van Overmeir C, van Geertruyden JP, van Doren W, Ngamije D, D’Alessandro U. Safety and efficacy of dihydroartemisinin/piperaquine (Artekin) for the treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Rwandan children. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2006;100:1105–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthmann JP, Ampuero J, Fortes F, van Overmeir C, Gaboulaud V, Tobback S, Dunand J, Saraiva N, Gillet P, Franco J, Denoncin A, van Herp M, Balkan S, Dujardin JC, D’Alessandro U, Legros D. Antimalarial efficacy of chloroquine, amodiaquine, sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine, and the combinations of amodiaquine + artesunate and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine + artesunate in Huambo and Bie provinces, central Angola. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2005;99:485–492. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamour S, Melaku Y, Keus K, Wambugu J, Atkin S, Montgomery J, Ford N, Hook C, Checchi F. Malaria in the Nuba Mountains of Sudan: baseline genotypic resistance and efficacy of the artesunate plus sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine and artesunate plus amodiaquine combinations. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2005;99:548–554. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Broek I, Amsalu R, Balasegaram M, Hepple P, Alemu E, Hussein El B, Al-Faith M, Montgomery J, Checchi F. Efficacy of two artemisinin combination therapies for uncomplicated falciparum malaria in children under 5 years, Malakal, Upper Nile, Sudan. Malar J. 2005;4:14. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-4-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeka A, Banek AK, Bakyaita N, Staedke SG, Kamya MR, Talisuna A, Kironde F, Nsobya SL, Kilian A, Slater M, Reingold A, Rosenthal PJ, Wabwire-Mangen F, Dorsey G. Artemisinin versus nonartemisinin combination therapy for uncomplicated malaria: randomized clinical trials from four sites in Uganda. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e190. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rwagacondo CE, Karema C, Mugisha V, Erhart A, Dujardin JC, Van Overmeir C, Ringwald P, D’Alessandro U. Is amodiaquine failing in Rwanda? Efficacy of amodiaquine alone and combined with artesunate in children with uncomplicated malaria. Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9:1091–1098. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staedke SG, Mpimbaza A, Kamya MR, Nzarubara BK, Dorsey G, Rosenthal PJ. Combination treatments for uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Kampala, Uganda: randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1950–1957. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17478-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukirwa H, Yeka A, Kamya MR, Talisuna A, Banek K, Bakyaita N, Rwakimari JB, Rosenthal PJ, Wabwire-Mangen F, Dorsey G, Staedke SG. Artemisinin combination therapies for treatment of uncomplicated malaria in Uganda. PLoS Clin Trials. 2006;1:e7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pctr.0010007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for the Treatment of Malaria. Second Edition, March 2010 – Section 5.2 Therapeutic Efficacy cut-Offs for Changing Treatment Policy. pp. 8–9. http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/9789241547925/en/index.html.

- Maiga AW, Fofana B, Sagara I, Dembele D, Dara A, Traore OB, Toure S, Sanogo K, Dama S, Sidibe B, Kone A, Thera MA, Plowe CV, Doumbo OK, Djimde AA. No evidence of delayed parasite clearance after oral artesunate treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Mali. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;87:23–28. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.12-0058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White NJ. The parasite clearance curve. Malar J. 2011;10:278. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Proportion by site of patients still parasitaemic on Day 1, Day 2, Day 3, and parasite clearance failure, ASAQ groups.