Abstract

Aim:

The present study was conducted to evaluate the hepatoprotective activity of Tephrosia purpurea (TP) against sodium arsenite (NaAsO2) induced sub-acute toxicity in rats.

Materials and Methods:

Twenty four wistar albino rats of either sex were randomly divided into three groups. Group II and III were orally administered with sodium arsenite (10 mg/kg) daily in drinking water for 28 days. Additionally Group III was orally treated with hydro-alcoholic extract of Tephrosia purpurea (TP) @ 500 mg/kg daily for the same time period, whereas only deionized water was given to Group I (control). Serum biomarker levels, oxidative stress parameters and arsenic concentration were assessed in liver. Histopathology was also conducted.

Results:

It has been seen that TPE (500 mg/kg) significantly (P < 0.01) reduced serum ALT, AST, ALP activity and increased total protein and reduced necrosis and inflammation in liver of group III compared to group II. A significantly (P < 0.01) higher LPO and lower GSH levels without change in SOD activity in liver was also observed in group II compared to group III, though there was no significant difference in arsenic accumulation between them. The plant extract also protects the animals of group III from significant (P < 0.01) reduction in body weight.

Conclusion:

Our study shows that supplementation of Tephrosia purpurea extract (500 mg/kg) could ameliorate the hepatotoxic action of arsenic.

KEY WORDS: Arsenic, hepatotoxicity, rats, sub-acute toxicity, Tephrosia purpurea

Introduction

Exposure to heavy metals has become a common problem throughout the world due to contaminated drinking water, food and air. Arsenic is one of most important metalloid and persists as organic, inorganic and elemental form in nature. Trivalent arsenic species are most toxic than pentavalent arsenic compounds.[1] Arsenic toxicity results from its ability to interact with sulfhydryl groups of enzymes and disrupt enzymes involved in cellular respiration, that leads to inhibition of glycolysis and Krebs cycle and substitute phosphorus in a variety of biochemical reactions.[2] Recent findings suggested that exposure to arsenic causes oxidative stress through increased generation of Reactive Oxygen Species and inhibition of antioxidants in the body.[3] Generally arsenic undergoes hepatic biomethylation to monomethylarsonic acid and dimethylarsinic acids and are potent inhibitors if GSH reductase and causes hepatotoxicity in human and animals.[4]

Use of medicinal plants possessing potent antioxidant property can help to reduce oxidative stress and hepatotoxicity caused by metals. Tephrosia purpurea is a perennial herb found throughout India and belongs to fabaceae family. Phytochemical investigation revealed the presence of flavonoids, glycosides, rotenoids, isoflavones, flavanones, chalcones, flavanols and sterols.[5] It is commonly used for the treatment of jaundice, dyspepsia, diarrhoea, rheumatism, asthma and urinary disorders.[6] It is one of most effective ingredients of formulations available in Indian market as liver tonics but literatures regarding the effect of Tephrosia purpurea extract against arsenic induced hepatotoxicity are not available. Keeping this in view the present study was designed to evaluate the hepatoprotective activity of this plant against arsenic induced toxicity in wistar albino rats.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Animals

Healthy male and female wistar albino rats (140 to 150 gms) were purchased from Laboratory Animal Research Station, I.V.R.I, Izatnagar, Bareily, U.P, India and housed in propylene cages under standard laboratory conditions (23 ± 2°C, 12 h dark and light cycle, 60% humidity) and allowed for acclimatization for a period of 15 days before starting the experiment. Rats were offered standard diet and water given ad-libitum during period of acclimatisation and experiment. The experimental protocol was approved by Institutional Animal Ethical Committee with approval No. 528/RVC/IAEC/119.

Arsenic Solution

Sodium arsenite (Himedia, Bombay, Maharastra) (10 mg/kg) was dissolved in distilled water and orally administered with oral gavage needle to individual animals. The dose was according to the ¼ of oral LD50 of sodium arsenite in rats.[7]

Plant Material

The aerial parts of Tephrosia purpurea were collected, washed with distilled water, shade dried, pulverisedand freshly prepared powder (25 gms) was immersed in hydro-alcoholic solution (40% distilled water + 60% ethanol) in a flask stoppered and was kept at room temperature for 48 hours at 150 rpm in orbital shaker. The contents were filtered through muslin cloth and filtered through whatman No. 1 filter paper and extract dried in a petridish at room temperature and used along with gum acacia @ 500 mg/kg body weight[8] was given to individual animal with oral gavage needle.

Experimental Design

Twenty four numbers of rats were grouped into three containing eight animals each were assigned for this study. Group I was considered as control group where only deionized water was given. Group II and III were orally administered with sodium arsenite @ 10 mg/kg daily in drinking water for 28 days. Additionally Group III was orally treated with hydro-alcoholic extract of Tephrosia purpurea extract (TPE 500 mg/kg daily) for the same time period.

Body Weight and Sample Collection

Animals from each group were weighed on day 0 and 29. At end of the experiment, all animals were slaughtered on day 29, serum and liver tissues samples were collected and following parameters were estimated.

Serum Enzyme Activity

Blood was collected into plain vials and Serum was separated and AST, ALT, ALP, Serum total protein were estimated on Erba-semi autoanalyzer (ERBA Diagnostics Mannheim GmbH, Mallaustr, 69-73, D-68219, Mannheim/Germany).

Oxidative Stress Analysis

The pieces of liver thus collected after the sacrifice of the experimental animals were washed in ice cold saline and 200 mg of liver tissue sample was weighed and taken in 2 ml of ice-cold saline. For estimation of GSH, 200 mg of liver tissue sample was taken in 0.02 M Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid The homogenate was prepared in Remi-Homogeniser and was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was used for estimation of following oxidative stress indices. Superoxide dismutase was estimated as per the method.[9] The extent of lipid peroxidation was evaluated in terms of MDA production, determined by the thiobarbituric acid method.[10] The reduced glutathione level (GSH) was determined by using 5,5’- dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid (DTNB) method[11] in liver homogenate by using UV-VIS spectrophotometer (ECI, Hyderabad).

Analysis of Arsenic

Total arsenic in liver was quantified by digestion, using tri-acid mixture of nitric acid, perchloric acid and sulphuric acid (10:4:1) following the method.[12] The digested samples were diluted with deionized Millipore water, passed through Whatman filter paper No. 4 (Rankem, India) and made the volume to 10ml. Concentrated hydrochloric acid (5 ml) was added to it and shaken well. Then after 1ml of potassium iodide (5% w/v) and ascorbic acid (5% w/v) mixture was added and the aliquot was incubated for 45 min for transformation of arsenate to arsenite. The final volume was made up to 50ml with Millipore water and arsenic concentration read on Varian AA240 model AAS Atomic Absorption Spectrometer (AAS) equipped with vapour generation accessories. The operating parameters were: lamp, arsenic hollow cathode lamp; wavelength, 193.7 nm; slit width, 0.5 nm; lamp current, 10.0 mA; vapor type, air/acetylene; air flow, 10.00 L/min; inert gas for hydride generation, Argon. Reducing agent (Aqueous solution of 0.6% sodium borohydride was prepared in 0.5% w/v sodium hydroxide) and 40% hydrochloric acid (HCl) were prepared freshly before use. The working standards were 5, 10, 20 and 40μg/L and prepared by same procedure as test sample.

Histopathology

Histopathology of Buffered formalin fixed liver samples were routinely processed, cut at 5μm and stained with H and E stain.[13]

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was done by ANOVA using SPSS software version 17.0. A value P < 0.05 (*) and P < 0.01 (**) were considered significant at 5 and 1% level respectively.

Results

Gain in Bodyweight

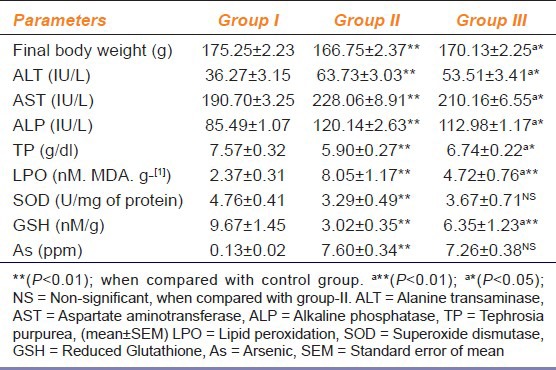

The average body weight of group I, II and III were respectively 145.63 ± 1.40, 146.38 ± 1.43 and 147.38 ± 1.15 g. Animals of all the groups showed gain in their body weight during entire trial period but there was reduced body weight in group II on 29th day as compared with other groups [Table 1].

Table 1.

Effect of sodium arsenite (10 mg/kg day p.o for 28 days) alone and in combination with Tephrosia purpurea extract (500 mg/kg day p.o for 28 days) in rats

Serum Bio-markers

It is evident from Table 1 that serum bio-marker levels of Alanine transaminase (ALT) and Alkaline phosphatase(ALP) were significantly (P < 0.01) higher in both group II and III compared to group I, though the activities of these two enzymes were significantly (P < 0.05) lower in group III compared to group II. Serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) activity was increased significantly in group II, whereas there was no significant change of activity in group III compared to group I. There was significant (P < 0.01) decrease in Serum Total Protein in both group II and III compared to group I, though there was significant (P ≤ 0.05) increase in group III compared to group II.

Oxidative Stress Indices

Table 1 shows that lipid peroxidation in liver tissue was significantly (P < 0.01) higher in only arsenic treated group (group II) whereas Tephrosia purpurea treated animals (group III) showed no significant change in lipid peroxidation compared to the control (group I). Reduced glutathione level in liver was significantly (P < 0.01) lower in both group II and group III compared to group I, though the level was again significantly (P < 0.01) lower in group II compared to group III [Table 1]. There was no significant change in SOD activity in either of the groups [Table 1].

Arsenic Concentration

Arsenic concentration was respectively 0.13 ± 0.02, 7.60 ± 0.34 and 7.26 ± 0.38μg/g in liver of group I, II and III [Table 1].

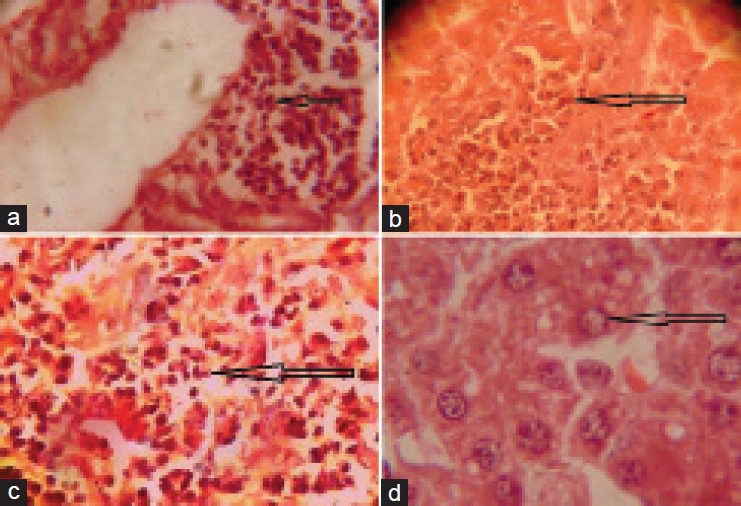

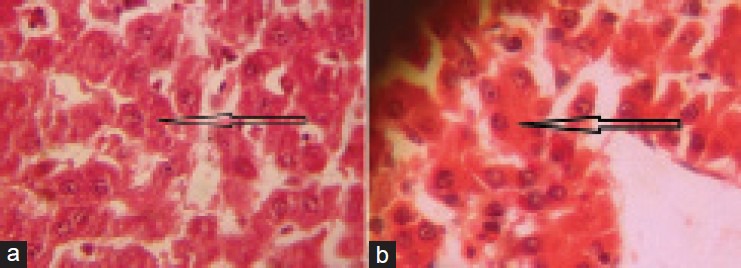

Histopathology

The microscopic section of liver of rats fed with NaAsO2 (10 mg/kg) revealed varying degree of hepatocytic degeneration, characterised by vacuolar degeneration along with inflammation followed by hepatic necrosis. Hepatocytic necrosis depicted features of vacuolation of cytoplasm along with pyknosis and loss of cellular architecture. Multi focal mononuclear cell infiltration was also observed in degenerating parenchyma [Figure 1a–d]. The microscopic section of liver treated with NaAsO2 (10 mg/kg) + TPE (500 mg/kg) in group - III, revealed reduced necrosis of parenchyma [Figure 2a and b].

Figure 1.

(a) Microphotograph showing infiltration of mononuclear cells around central vein in liver of rat treated with Sodium arsenite @ 10 mg/kg (×400). (b) Microphotograph showing necrosis, degenerating parenchyma in of rat treated with Sodium arsenite @ 10 mg/kg. (×400). (c) Microphotograph showing the highly necrosed area, degenerating parenchyma and damaged cellular architecture in liver of rat treated with sodium arsenite @ 10 mg/kg. (×400). (d) Microphotograph showing necrosis and vacuolar degeneration in liver of rat treated with sodium arsenite @ 10 mg/kg (×400)

Figure 2.

(a) Microphotograph showing mild necrosis in liver of rat treated with sodium arsenite @ 10 mg/kg + Tephrosia purpurea extract @ 500 mg/kg. (×400). (b) Microphotograph showing reduced necrosis of hepatocytes in liver of rat treated with sodium arsenite @ 10 mg/kg + Tephrosia purpurea extract @ 500 mg/kg (×400)

Discussion

Arsenic is highly toxic and corrosive to gastrointestinal tract resulting into partial anorexia and gastro-intestinal disturbances followed by loss of body weight[14] in arsenic intoxicated animals, compared to control animals on day 29. Tephrosia purpurea possess a potent antioxidant activity, reduces increased oxidative stress and protects the tissues from the oxidative damage, which may be one of reason for normal increase in body weight in TPE treated group. Arsenic at high doses causes acute hepatic injury and hepatocellular necrosis causing leakage of hepatocellular enzymes into blood and the extent of injury to the hepatocytes is generally detected by the activity of AST, ALT and ALP in serum. Higher level of these enzymes in arsenic exposed animals was due to hepatic injury caused by the metalloid following 28 days of exposure. The increased levels of hepatic serum enzymes can be corroborated with the earlier reports.[15] Lower activity of serum enzymes in Tephrosia purpurea treated group was probably due to the presence of flavonoids[16] that produces hepatocellular membrane stability, prevention of cellular leakage and increasing hepatic regeneration. Liver is the main site of synthesis of proteins, therefore hepatic damage caused by arsenic leads to decrease in the levels of serum total protein in group treated only with NaAsO2.[17] Arsenic toxicity results from its ability to interact with sulfhydryl groups of proteins and enzymes and inhibits electron transport and cellular respiration in mitochondria causing increase in hydrogen peroxide production which forms reactive oxygen species and oxidative stress.[18] This study showed non-significant decrease in SOD levels in both the experimental groups (group II and III) as compared to control group. Superoxide dismutase is an important antioxidant enzyme responsible for the elimination of superoxide radical. The exhausted SOD levels observed in this study might be due to overproduction of free radicals in the body. The present study showed that lipid peroxidation was significantly higher in only arsenic treated group as compared to TPE treated group. The reduced glutathione level (GSH) in liver tissue was significantly (P < 0.01) lower in both the experimental groups (group II and III) as compared to control group, however group treated only with NaAsO2 showed significantly much exhaustion of reduced glutathione level compared to TPE treated group. Reduced glutathione (GSH) is a sulphydryl (-SH) antioxidant in the body. It provides protection to the mitochondria from generated free radicals. The significant decrease in GSH level in liver of rat may be due to binding of arsenic and also might be due to increased ROS in arsenic poisoning.[19] Tephrosia purpurea gives significant protection against oxidative stress induced by arsenic probably due to the presence of poly phenolic compounds and flavonoids in leaves having free radical scavenging activity and hepatoprotective activity.[20] Tissue retention of arsenic increases with the length of exposure due to the lesser rate of excretion of arsenic than exposure which causes accumulation in tissues.[21] Liver being the main workhouse of metabolism, arsenic was accumulated at high concentration in liver of the arsenic exposed groups in the present study. Arsenic concentration is higher in liver of animals in both the experimental groups (group II and III) without any significant (P < 0.01) difference in accumulation between them, that indicates that Tephrosia purpurea may not have any effect in reduction of arsenic accumulation in liver. Histopathological examination revealed necrosis, vacuolar and inflammatory changes in liver of arsenic treated group. Similar results were also reported by earlier workers.[22] Tephrosia purpurea possess potent antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and free radical scavenging activity. Thus it is able to protect hepatic tissue from arsenic induced free radicals and prevent inflammation and necrosis of the hepatic cells in Tephrosia purpurea extract treated group.[23] This was confirmed on the basis of decreased necrosis, vacuolar changes in histological examination.

Conclusion

Tephrosia purpurea possess flavonoids having antioxidant and free radical scavenging property, It reduces the oxidative stress caused by arsenic, by reducing the ROS production, maintaining the antioxidant potential and significantly reducing elevated serum bio-marker levels in the body. Our study shows that supplementation of Tephrosia purpurea extract (500 mg/kg) could ameliorate the hepatotoxic action of arsenic by reducing oxidative stress.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: No

References

- 1.Chowdary R, Dutta A, Chaudari SR, Sharma N, Giri AK, Chaudari K. In vitro and in vivo reduction of sodium arsenite induced toxicity by aqueous garlic extract. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46:740–51. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.09.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patlolla AK, Tchounwou PB. Serum Acetyl Cholinesterase as a Biomarker of Arsenic Induced Neurotoxicity in Sprague-Dawley Rats. Int J Environ Res Pub Heal. 2005;2:80–3. doi: 10.3390/ijerph2005010080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Modi M, Mittal M, Flora SJ. Combined administration of selenium and meso-2, 3-dimercaptosuccinic acid on arsenic mobilization and tissue oxidative stress in chronic arsenic-exposed male rats. Indian J Pharmacol. 2007;39:107–14. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patra PH, Bandyopadhyay S, Kumar R, Datta BK, Maji C, Biswas S, et al. Quantitative imaging of arsenic and its species in goat following long term oral exposure. Food Chem Toxicol. 2012;50:1946–50. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rao VE, Raju RN. Two flavonoids from Tephrosia purpurea. Phytochem. 1984;23:2339–42. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gopalakrishnan S, Vadivel E, Dhanalakshmi K. Phytochemical and pharmacognostical studies of “Tephrosia purpurea” Linn. aerial and root parts. J Herb Med Toxicol. 2009;3:73–8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown JL, Kitchin KT. Arsenite, but not cadmium, induces ornithine decarboxylase and hemeoxygenase activity in rat liver: Relevance to arsenic carcinogenesis. Cancer Lett. 1996;98:227–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khatri A, Garg A, Agrawal SS. Evaluation of hepatoprotective activity of aerial parts of Tephrosia purpurea and stem bark of Tecomella undulate. J Ethnopharm. 2009;122:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Madesh M, Balasubramanian KA. Microtiter plate assay for superoxide dismutase using MTT reduction by superoxide. Indian J Biochem Biophys. 1998;35:184–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rehman SU. Lead induced regional lipid peroxidation in brain. Toxicol Lett. 1984;21:333–7. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(84)90093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sedlak F, Lindsay RH. Estimation of total, protein bound and nonprotein sulfhydryl groups in tissue with ellman's reagent. Anal Biochem. 1968;25:192–205. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(68)90092-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Datta BK, Mishra A, Singh A, Sar TK, Sarkar S, Bhatacharya A, et al. Chronic arsenicosis in cattle with special reference to its metabolism in arsenic endemic village of Nadia district West Bengal India. Sci Total Environ. 2010;409:284–8. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Culling CF. 3rd ed. 88 Kingsway, WC2B 6AB London: Butterworth and Co. (Publishers) ltd; 1974. Hand book of histopathological and histochemical techniques. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dwivedi VK, Arya A, Gupta H, Bhatnagar A, Kumar P, Chaudary M. Chelating ability of sulbactomax drug in arsenic intoxication. Afr J Biochem Res. 2011;5:307–14. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patra PH, Bandyopadhyay S, Kumar R, Datta BK, Maji C, Biswas S, et al. Quantitative imaging of arsenic and its species in goat following long term oral exposure. Food Chem Toxicol. 2010;50:1946–50. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sangeetha B, Krishnakumari S. Tephrosia purpurea (Linn) pers: A folk medicinal plant ameliorates carbon tetrachloride induced hepatic damage in rats. Int J Pharm Biosci. 2010;1:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rana T, Sarkar S, Mandal TK, Batabyal S. Haematobiochemical profiles of affected cattle at arsenic prone zone in Haringhata block of Nadia District of West Bengal in India. Inter J Haematol. 2008;4:1642–57. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stanton CR, Thibodeau R, Lankowski A, Shaw JR, Hamilton JW, Stanton BA. Arsenic inhibits CFTR-mediated chloride secretion by killifish (Fundulusheteroclitus) opercular membrane. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2006;17:269–78. doi: 10.1159/000094139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guarino MP, Afonso RA, Raimundo N, Raposo JF, Macedo MP. Hepatic glutathione and nitric oxide are critical for hepatic insulin-sensitizing substance action. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;284:G588–94. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00423.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel A, Patel A, Patel A, Patel NM. Estimation of flavonoid, polyphenolic content and In-vitro antioxidant capacity of leaves of Tephrosia purpurea Linn. (Leguminosae) Int J Pharma Sci Res. 2010;1:66–77. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nandi D, Patra RC, Ranjan R, Swarup D. Role of co-administration of antioxidants in prevention of oxidative injury following sub-chronic exposure to arsenic in rats. Veteri Arch. 2008;78:113–21. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mazumder DN. Effect of chronic intake of arsenic contaminated water on liver. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;206:169–75. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khatri A, Garg A, Agrawal SS. Evaluation of hepatoprotective activity of aerial parts of Tephrosia purpurea and stem bark of Tecomella undulate. J Ethnopharm. 2009;122:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]