Abstract

Diabetes Mellitus is a common metabolic disorder presenting increased amounts of serum glucose and will cover 5.4% of population by year 2025. Accordingly, this review was performed to gather and discuss the stand points on diagnosis, pathophysiology, non-pharmacological therapy and drug management of diabetes this disorder as described in medieval Persian medicine. To this, reports on diabetes were collected and analyzed from selected medical and pharmaceutical textbooks of Traditional Persian Medicine. A search on databases as Pubmed, Sciencedirect, Scopus and Google scholar was also performed to reconfirm the Anti diabetic activities of reported herbs. The term, Ziabites, was used to describe what is now spoken as diabetes. It was reported that Ziabites, is highly associated with kidney function. Etiologically, Ziabites was characterized as kidney hot or cold dystemperament as well as diffusion of fluid from other organs such as liver and intestines into the kidneys. This disorder was categorized into main types as hot (Ziabites-e-har) and cold (Ziabites-e-barid) as well as sweet urine (Bole-e-shirin). Most medieval cite signs of Ziabites were remarked as unusual and excessive thirst, frequent urination and polydipsia. On the management, life style modification and observing the essential rules of prevention in Persian medicine as well as herbal therapy and special simple manipulations were recommended. Current investigation was done to clarify the knowledge of medieval scientists on diabetes and related interventions. Reported remedies which are based on centuries of experience might be of beneficial for- further studies to the management of diabetes.

Keywords: Diabetes, herbal medicine, medieval persia, traditional medicine, Ziabites

INTRODUCTION

With reference to the findings of contemporary medicine, Diabetes Mellitus is a common metabolic disorder. This complication which is resulted from insulin insufficiency or dysfunction may cover over 5.4% of population or 57.2 million people by the year 2025.[1,2] Although the pathophysiology of diabetes is not yet well understood, evidences have suggested the impact of free radicals in the pathogenesis and development of diabetes.[3,4] Most common cited symptoms of diabetes Mellitus are increased serum glucose, unusual thirst, frequent urination, blurred vision, hyperphagia, nausea and vomiting as well as loss of weight.[5] On the treatment pathway, a number of medicaments are administered in addition to the insulin therapy.[6] Other than the current pharmacotherapy of diabetes, interventions concerned to the complementary and alternative medicine are also considerable. Accordingly, extensive information would be obtained from the beliefs of folk medicine and practices by local healers as well as remained manuscripts of traditional medical systems.[7] With respect to the findings of integrative medical systems, it is remarkable that Traditional Persian Medicine (TPM) plays a considerable role in the development of treatment approaches during the medieval era.[8] During the 8th to 12th century AD, Persian physicians and scholars such as Rhazes and Avicenna gathered the medical information of traditional remedies from China, Egypt, Greece and India and also supplemented it by their own findings and experiences.[9,10] In this regard, remained medical and pharmaceutical manuscripts authored by early Persian practitioners encompass large and remarkable information on various categories of ailment. Among those, considering the nutritional aspects and pharmacological of diabetes and related complications would be of beneficial. Accordingly, current study has been carried out to gather the most cited medieval Persian information on diabetes as well as those management approaches.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

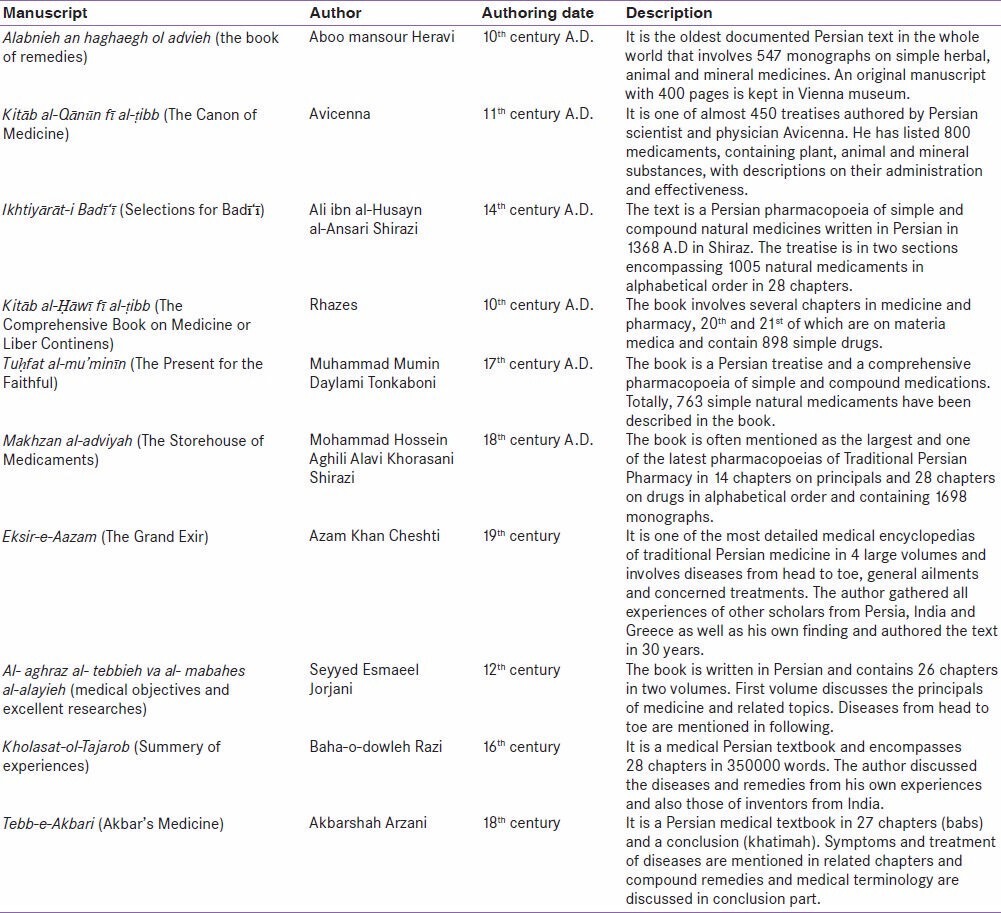

Medieval reports encompassing the profile of definition and terminology, classification and etiology, as well as sign and symptoms of diabetes were collected and analyzed from selected medical textbooks of TPM. The concerned collection was based on the analysis of remaining manuscripts of medieval Persia from 9th to 18th centuries AD involving medical and pharmaceutical textbooks of this period. In this regard, manuscripts namely Canon of Medicine (11th century), Al- aghraz al- tebbieh va al- mabahes al-alayieh (12th century), Kholasat-ol-Tajarob (16th century), Tebb-e-Akbari (18th century) and Eksir-e-Aazam (19th century) were considered for the medical points.[11,12,13,14,15] On the other hand, pharmacological treatment aspects of diabetes in medieval period were also gathered from main Persian pharmaceutical manuscripts containing The Liber Continents by Rhazes (9th and 10th centuries), The Canon of Medicine by Avicenna (11th centuries), Alabnie an haghaegh-ol-advieh by Aboo mansour Heravi (10th century), Ikhtiyarat-e-Badiyee by Zein al-Din Attar Ansari Shirazi (14th century), Tohfat ol Moemenin by Mohammad Tonkaboni (17th century) and Makhzan ol Advieh by Aghili-Shirazi (18th century).[16,17,18,19,20] These texts are considered as most important sources among medical and pharmaceutical manuscripts of Persian medicine.[21] Other textbooks such as “Matching the Old Medicinal Plant Names with Scientific Terminology”,[22]“Dictionary of Medicinal Plants”,[23] “Dictionary of Iranian Plant Names”,[24] “Popular Medicinal Plants of Iran”[25] and “Indian Medicinal Plants”[26] were also used to check and reconfirm the plants scientific names. Table 1 represented brief information on employed manuscripts of medieval Persian medicine.

Table 1.

Medieval manuscripts which were reviewed for the survey

It is also considerable, that an extensive search on most popular databases as Pubmed, Sciencedirect, Scopus and Google scholar was performed to reconfirm the Anti diabetic activities of reported herbs as well as concerned pharmacological actions.

RESULTS

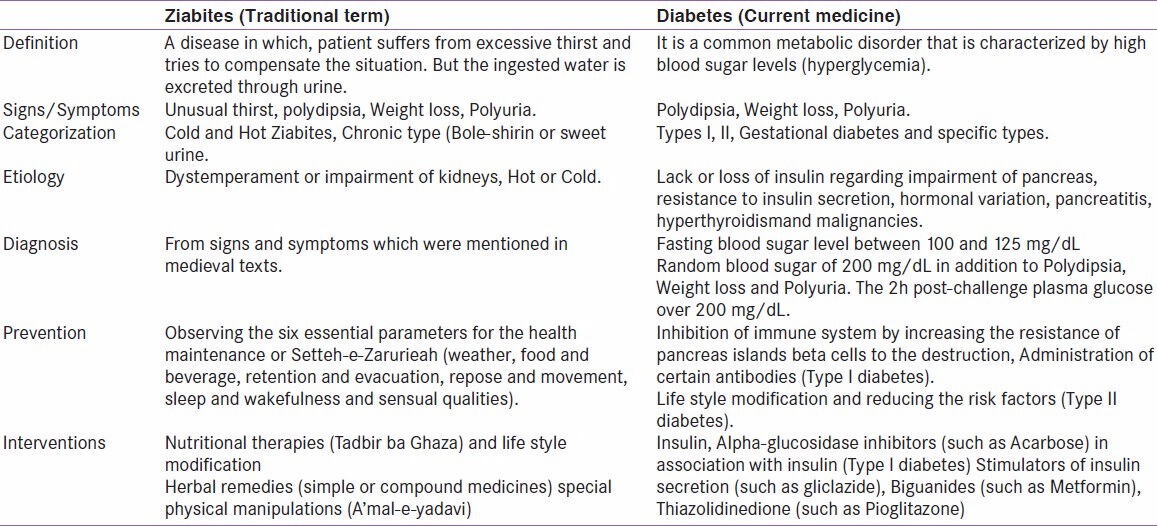

Diabetes, current medicine

As a metabolic disorder, diabetes is characterized in that of unexpected serum glucose elevation. General manifestation of diabetes is known as polyuria, polydipsia and polyphagia as well as weight loss. Generally, diabetes is divided into two main types, 1 and 2. Type 1 is resulted from loss of insulin secretion and the most prevalent of type 2 is reported as obesity and unusual weight gain. In addition to these main groups, gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is also present as the commonest metabolic disorder during pregnancy. Other specific diabetes types also need to be mentioned. Of those, genetic defects of beta cell function, insulin genetic dysfunction, exocrine pancreatic disorders and endocrinopathies such as hyperthyroidism and glucagonoma may cause diabetes. Also a kind of diabetes namely diabetes insipidus is reported in medical textbooks which is related to impaired angiotensin-vasopressin secretion.[27] Main clinical approaches in diabetes mellitus include life style modification, drug therapy to control glycemia and prevention/management of associated complication.[27]

Ziabites, Medieval definition, etiology, categories and clinical manifestation

The term, Ziabites, or Doolab (water wheel) in Persian, was used by early Persian scholars to define and describe what is currently spoken as diabetes. Since, Ziabites is a Greek word; it was mentioned by Greek physicians well before the entrance to Persian manuscripts. Concerning the definition, it was remarked that the disorder of Ziabites, which in that patient suffers from excessive thirst, is highly associated with kidney function. It was said that retentive force of kidney is impaired and hence can be distinguished by excessive urine output. Furthermore, the diffusion of fluid from other organs such as liver and intestines into the kidneys was noted as another etiological symptom that Persian scholars believed in.[11,13,14]

Similar to the fundamental mechanisms of humoral medicine,[28] the disorder was said that may be resulted from an imbalance in the kidney temperament as well as whole body. Hence, treatment was based on the modification of temperament and humors to reach to an optimum or balanced state.[29]

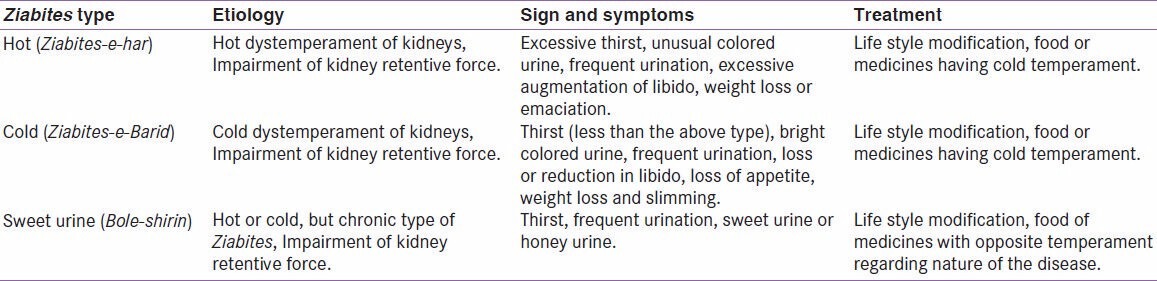

Regarding the mentioned dystemperament, the disorder was categorized into two main types as hot (Ziabites-e-har) and cold (Ziabites-e-barid). The hot type was reported to be accompanied by unusual and excessive thirst, unusual colored urine and frequent urination as well as excessive augmentation of libido and weight loss or emaciation. On the other hand, in cold type, thirst but less than the above type, bright colored urine, loss or reduction in libido, loss of appetite and also weight loss and slimming. According to the medieval reports, the hot type of Ziabites was more prevalent.[11,13,14]

In a resulted version of Ziabites, Persian scholars remarked that ants and other insects may be attracted to the patient's urine. Also it was mentioned by Avicenna that by standing the urine of a diabetic patient under surrounding air, a residue is leaved with sticky and sweet tastes as honey.[30] Ziabites, in this case was named as Bole-e-shirin or sweet urine. This type was reported that may be occurred in case of chronicity of Ziabites. It was also assumed that the kidney function may be impaired in this condition. Therefore, all medications and management strategies which were considered for the impaired kidneys should also be applied for this disorder, as it was mentioned by early Persian practitioners.[11] Table 2 represented the classification of diabetes according to Persian medicine. Also a brief overview and comparison between modern aspects of diabetes and medieval description of Ziabites is represented in Table 3.

Table 2.

Medieval classification of Ziabites

Table 3.

Ziabites and Diabetes, the comparison

Clinical interventions

Concerning the management strategies as well as preventive approaches for Ziabites, there are lots of recommendations in reviewed manuscripts. The six essential schemes for health maintenance which were called Setteh-e-Zarurieah (involving observation and optimization of six main parameters as weather, food and beverage, retention and release, repose and movement, sleep and wakefulness as well as sensual and mental states) were considered as main preventive approaches. These parameters were being observed prior medication and are considered as life styles in current medicine.[31]

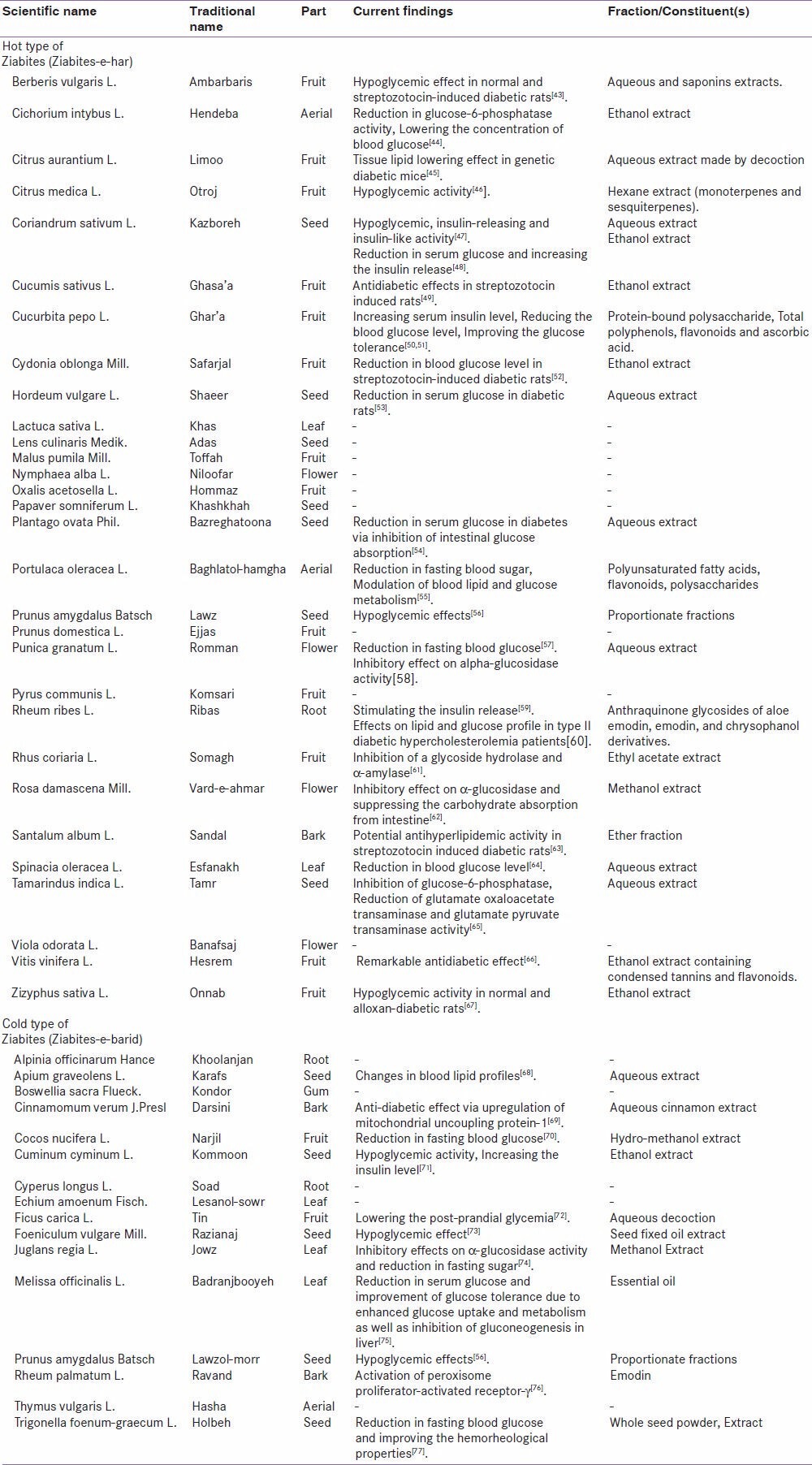

Pharmaceutical manuscripts of Persian medicine offer plenty of natural remedies for the management of Ziabites. Natural medicines were applied solely (mono-ingredient) or in combination to other medicaments (multi-ingredients). Early practitioners applied three main categories of medicaments. First approach was based on nutritional therapy (Tadbir ba Ghaza) and life style modification. In this condition, natural agent with opposite temperament compared to the type of Ziabites was administered. In the other word, foods or beverages such as beer, milk, barely soap, Plum and courgette khoresht, yogurt and verjuice which possess cold temperament were applied for hot type of Ziabites.[32] On the other hand, medicinal herbs in form of simple or compound dosage forms were administered to manage the disorder. Most cited natural medicaments concerned to either hot or cold Ziabites are shown in Table 4. Other than the natural pharmacotherapy, special physical manipulations (A'mal-e-yadavi) have also being applied by early Persian physicians. These approaches were usually involved venesection (Fasd), cupping (Hijamat) and massaging (Dalk). Regarding the type of Ziabites and also patient's dystemperament, these interventions were applied before or after herbal therapy.[11] In addition to physical manipulation, other approaches were also considered. As an example, sitting in water was recommended by Rhazes. He believed that this procedure tightens the muscles of bladder and suppresses thirst.[33]

Table 4.

Most prevalent medicinal plant for the management of Ziabites

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Before mid of the nineteenth century, it was believed that diabetes is a disease related to kidney function.[34] However, in 1922, the isolation of insulin from animal pancreas confirmed the diabetes as an endocrine disorder.[35] Findings from main manuscripts of Persian medicine revealed that there are some similarities between the disorder of Ziabites and what is currently accepted as diabetes mellitus. Unusual thirst, polyuria and weight loss are some of the main similarities. On the other hand, Ziabites may also be closed to diabetes insipidus. But it should be noted that polyuria would not be stopped in this type of diabetes even if no fluid is ingested.[32] In the type II of diabetes, a large group of affected patients may have no notification about their disorder and serum glucose evaluation should be carried out to confirm the disorder. It seems that in medieval time, also a large number of patient with this type of diabetes were left uncured in due to lack of paraclinical examinations. With reference to the management of Ziabites, many instructions regarding health maintenance were recommended by Persian scholars. Considering the six essential parameters (Setteh-e-Zarurieah) were highly emphasized by early Persian practitioners. Similar to these rules, current medicine has also rendered considerable recommendation. Avoidance of environmental pollution,[36] scheduled and adequate exercise and sport,[37] appropriate sleep and awareness (sleep less than six hours is mentioned as a main predisposing factor for diabetes),[38] eluding stress and psychological tensions[39] as well as proper nutritional regimen and rich fiber foods have high impact on diabetes.[40] Concerning the treatment of different types of Ziabites, medicinal plants having specific temperament which was related to either hot or cold Ziabites were used for the treatment. Totally 46 different medicinal herbs were found as cure for hot or cold types of Ziabites. A search through considered databases revealed that almost 70% of reported medicaments were active for anti diabetic effects. Most considered mechanisms for medieval herbs were as reduction in serum glucose level or fasting blood sugar, increasing serum insulin level or stimulating the insulin release and inhibition of intestinal glucose absorption [Table 2].

It was believed that there are differences between various types of temperaments in different patients. In this regard, Persian practitioners differentiated Ziabites regarding the patient's temperament and used the relevant medication. This fact can be corresponding with what is accepted as pharmacogenetic in current medicine.[41] However, differences in temperament are also evaluated regarding the endocrine and immune system.[42] Therefore, according to the temperament, administration of similar medication for patients suffering from a disease should be avoided.

As Ziabites is composed of hot and cold types in TPM, different treatments have been recommended for each individual types of the disease and patients. However, this approach is not yet considered by contemporary medicine. Current research was a survey to clarify the knowledge of medieval Persian scientists on disorder of diabetes and related pharmacological intervention strategies. Reported remedies are based on centuries of experience and thus might be of beneficial for further studies to the management of diabetes and related unwanted effects.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Modak M, Dixit P, Londhe J, Ghaskadbi S, Paul AD. Indian herbs and herbal drugs used for the treatment of diabetes. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2007;40:163–73. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.40.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramachandran A, Snehalatha C, Viswanathan V. Burden of type 2 diabetes and its complications: The Indian scenario. Curr Sci Assoc. 2002;83:1471–6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matteucci E, Giampietro O. Oxidative stress in families of type 1 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:1182–6. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.8.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Niedowicz DM, Daleke DL. The role of oxidative stress in diabetic complications. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2005;43:289–330. doi: 10.1385/CBB:43:2:289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeFronzo RA. Pharmacologic therapy for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:281–303. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-4-199908170-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nathan DM, Buse JB, Davidson MB, Ferrannini E, Holman RR, Sherwin R, et al. Medical Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes: A Consensus Algorithm for the Initiation and Adjustment of Therapy: A consensus statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:193–203. doi: 10.2337/dc08-9025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shankar K, Liao LP. Traditional systems of medicine. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2004;15:725–47. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamedi A, Zarshenas MM, Sohrabpour M, Zargaran A. Herbal medicinal oils in traditional Persian medicine. Pharm Biol. 2013;51:1208–18. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2013.777462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zargaran A, Mehdizadeh A, Zarshenas MM, Mohagheghzadeh A. Avicenna (980-1037 AD) J Neurol. 2012;259:389–90. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-6219-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zargaran A, Zarshenas MM, Mehdizadeh A, Mohagheghzadeh A. Management of tremor in medieval Persia. J Histol Neurosci. 2013;22:53–61. doi: 10.1080/0964704X.2012.670475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan MA. Eksir-e-azam (The grand exir) Dehli: Nami Monshi Nolkshur (Litograph in Persian); 1869. pp. 446–54. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Avicenna . Kitab al-Qanun fial-tibb (Canon of Medicine Tehran) Vol. 3. Soroosh Press; 1988. pp. 1093–5. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jorjani SI. Al-Aghraz al-Tibbia val Mabahessat al-Alaiia (Medical Objectives and Excellent Research) Tehran University Press; 2005. p. 794. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noorbakhsh B. Kholasat ol-tajarob (Summary of Experiences) Tehran: Iran University Press; 2004. p. 347. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shah-Arzani MA. Tibb-e-Akbari (Akbar's medicine) Qom: Jalal-ed-Din; 2008. p. 840. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tonekaboni HM. Tohfat ol momenin (A Gift for the Faithful) In: Shams Ardekani MR, Rahimi RF, editors. Tehran: Research Center of Traditional Medicine. Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. Nashre Shahr Press; 2007. pp. 112–346. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aghili Khorasani Shirazi MH. Makhzan ol Advieh (The Storehouse of Medicaments) Tehran: Tehran University of Medical Sciences. Sahba Press; 1992. pp. 198–882. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shirazi ZA. Rewrited by Mir MT. Tehran: Pakhsh Razi Press; 1992. Ikhtiyarat-e-Badiyee (Selections for Badii) pp. 22–141. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rhazes . Al Havi (Liber Continent) Tehran: Academy of Medical Sciences; 2005. pp. 1016–17. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heravi AM. Alabnie an Haghaegh ol Advieh (The book of remedies) Tehran: Tehran University Press; 1992. pp. 12–43. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zarshenas MM, Petramfar P, Firoozabadi A, Moein MR, Mohagheghzadeh A. Types of headache and those remedies in traditional persian medicine. Pharmacogn Rev. 2013;7:17–26. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.112835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghahraman A, Okhovvat A. Matching the Old Medicinal Plant Names with Scientific Terminology. Tehran: Tehran University Press; 2004. pp. 32–134. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soltani A. Dictionary of Medicinal Plants. Tehran: Arjmand Press; 2004. pp. 30–179. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mozaffarian V. Dictionary of Iranian Plant Names. Tehran: Farhang Moaser Press; 2006. pp. 66–212. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amin G. Popular Medicinal Plants of Iran. Tehran: Tehran University Press; 2005. pp. 22–104. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khare C. Indian Medicinal Plants. US: Springer; 2007. pp. 70–133. [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:62–9. doi: 10.2337/dc10-S062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jackson WA. A short guide to humoral medicine. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001;22:487–9. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01804-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rezaeizadeh H, Alizadeh M, Naseri M, Ardakani MS. The traditional Iranian medicine point of view on health and disease. Iran J Public Health. 2009;38:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eknoyan G, Nagy J. A history of diabetes mellitus or how a disease of the kidneys evolved into a kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2005;12:223–9. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naseri M. The school of traditional Iranian medicine: The definition, origin and advantages. Iran J Pharm Res. 2004;3:20–3. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Asghari M, Sabet Z, Davati A, Kamalinejad M, Soltaninejad H, Naseri M. Investigation and comparison of Ziabites disease, in Iranian Traditional Medicine and diabetes disease, in classical medicine. Med Hist. 2012;3:11–37. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zaid H, Said O, Hadieh B, Saad AK, Bashar Diabetes prevention and treatment with Greco-Arab And Islamic-based natural products. Jamia. 2011;4:19–38. [Google Scholar]

- 34.King KM, Rubin G. A history of diabetes: From antiquity to discovering insulin. Br J Nurs. 2003;12:1091–5. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2003.12.18.11775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Macleod JJ. History of the researches leading to the discovery of insulin: With an introduction by Lloyd G. Stevenson. Bull Hist Med. 1978;52:295–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sun Q, Yue P, Deiuliis JA, Lumeng CN, Kampfrath T, Mikolaj MB, et al. Ambient air pollution exaggerates adipose inflammation and insulin resistance in a mouse model of diet-induced obesity. Circulation. 2009;119:538–46. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.799015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferrara CM, Goldberg AP, Ortmeyer HK, Ryan AS. Effects of aerobic and resistive exercise training on glucose disposal and skeletal muscle metabolism in older men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:480–7. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.5.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chao CY, Wu JS, Yang YC, Shih CC, Wang RH, Lu FH, et al. Sleep duration is a potential risk factor for newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism. 2011;60:799–804. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2010.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramasubbu R. Insulin resistance: A metabolic link between depressive disorder and atherosclerotic vascular diseases. Med Hypotheses. 2002;59:537–51. doi: 10.1016/s0306-9877(02)00244-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Henry CJ, Lightowler HJ, Strik CM, Storey M. Glycaemic index values for commercially available potatoes in Great Britain. Br J Nutr. 2005;94:917–21. doi: 10.1079/bjn20051571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shastry BS. Pharmacogenetics and the concept of individualized medicine. Pharmacogenomics J. 2006;6:16–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shahabi S, Hassan ZM, Mahdavi M, Dezfouli M, Rahvar MT, Naseri M, et al. Hot and Cold Natures and some parameters of neuroendocrine and immune systems in traditional Iranian medicine: A preliminary study. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14:147–56. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.0693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meliani N, Dib ME, Allali H, Tabti B. Hypoglycaemic effect of Berberis vulgaris L. in normal and streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2011;1:468–71. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(11)60102-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pushparaj PN, Low HK, Manikandan J, Tan BK, Tan CH. Anti-diabetic effects of Cichorium intybus in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;111:430–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Campbell JI, Mortensen A, Molgaard P. Tissue lipid lowering-effect of a traditional Nigerian anti-diabetic infusion of Rauwolfia vomitoria foilage and Citrus aurantium fruit. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;104:379–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Conforti F, Statti GA, Tundis R, Loizzo MR, Menichini F. In vitro activities of Citrus medica L. cv. Diamante (Diamante citron) relevant to treatment of diabetes and Alzheimer's disease. Phytother Res. 2007;21:427–33. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gray MA, Flatt RP. Insulin-releasing and insulin-like activity of the traditional anti-diabetic plant Coriandrum sativum (coriander) Br J Nutr. 1999;81:203–9. doi: 10.1017/s0007114599000392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eidi M, Eidi A, Saeidi A, Molanaei S, Sadeghipour A, Bahar M, et al. Effect of coriander seed (Coriandrum sativum L.) ethanol extract on insulin release from pancreatic beta cells in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Phytother Res. 2009;23:404–6. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karthiyayini T, Rajesh K, Kumar KL, Sahu RK, Amit R. Evaluation of antidiabetic and hypolipidemic effect of Cucumis sativus fruit in streptozotocin-induced-diabetic rats. Biomed Pharmacol J. 2009;2:351–5. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Quanhong LI, Caili F, Yukui R, Guanghui H, Tongyi C. Effects of protein-bound polysaccharide isolated from pumpkin on insulin in diabetic rats. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2005;60:13–6. doi: 10.1007/s11130-005-2536-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dixit Y, Kar A. Protective role of three vegetable peels in alloxan induced diabetes mellitus in male mice. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2010;65:284–9. doi: 10.1007/s11130-010-0175-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aslan M, Orhan N, Orhan DD, Ergun F. Hypoglycemic activity and antioxidant potential of some medicinal plants traditionally used in Turkey for diabetes. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;128:384–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Naseri M, Ghavami B, Kamalinezhad M, Naderi GH, Faghihzadeh S. Effect of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) Seed extract on fasting serum glucose level in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. J Med Plants. 2010;9:57–66. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hannan JM, Ali L, Khaleque J, Akhter M, Flatt PR, Abdel-Wahab YH. Aqueous extracts of husks of Plantago ovata reduce hyperglycaemia in type 1 and type 2 diabetes by inhibition of intestinal glucose absorption. Br J Nutr. 2006;96:131–7. doi: 10.1079/bjn20061819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.El-Sayed MI. Effects of Portulaca oleracea L. seeds in treatment of type-2 diabetes mellitus patients as adjunctive and alternative therapy. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;137:643–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Teotia S, Singh M. Hypoglycemic effect of Prunus amygdalus seeds in albino rabbits. Indian J Exp Biol. 1997;35:295–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bagri P, Ali M, Aeri V, Bhowmik M, Sultana S. Antidiabetic effect of Punica granatum flowers: Effect on hyperlipidemia, pancreatic cells lipid peroxidation and antioxidant enzymes in experimental diabetes. Food Chem Toxicol. 2009;47:50–4. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2008.09.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li Y, Wen S, Kota BP, Peng G, Li GQ, Yamahara J, et al. Punica granatum flower extract, a potent alpha-glucosidase inhibitor, improves postprandial hyperglycemia in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;99:239–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Naqishbandi AM, Josefsen K, Pedersen ME, Jäger AK. Hypoglycemic activity of Iraqi Rheum ribes root extract. Pharm Biol. 2009;47:380–3. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Falah Hosseini H, Heshmat R, Mohseni F, Jamshidi AH, Alavi S, Ahvazi M, et al. The efficacy of rheum ribes L. stalk extract on lipid profile in hypercholesterolemic type II diabetic patients: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, clinical trial. J Med Plants. 2008;7:92–7. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Giancarlo S, Rosa LM, Nadjafi F, Francesco M. Hypoglycaemic activity of two spices extracts: Rhus coriaria L. and Bunium persicum Boiss. Nat Prod Res. 2006;20:882–6. doi: 10.1080/14786410500520186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gholamhoseinian A, Fallah H, Sharifi far F. Inhibitory effect of methanol extract of Rosa damascena Mill. flowers on α-glucosidase activity and postprandial hyperglycemia in normal and diabetic rats. Phytomedicine. 2009;16:935–41. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2009.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kulkarni CR, Joglekar MM, Patil SB, Arvindekar AU. Antihyperglycemic and antihyperlipidemic effect of Santalum album in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Pharm Biol. 2012;50:360–5. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2011.604677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Njai K, Loganathan P. Hypoglycemic effect of spinacia oleracea in alloxan induced diabetic rat. Glob J Biotechnol Biochem. 2010;5:87–91. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Maiti R, Jana D, Das UK, Ghosh D. Antidiabetic effect of aqueous extract of seed of Tamarindus indica in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;92:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Şendogdu N, Aslan M, Orhan DD, Ergun F, Yesilada E. Antidiabetic and antioxidant effects of Vitis vinifera L. leaves in streptozotocin-diabetic rats. Turk J Pharm Sci. 2006;3:7–18. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Anand KK, Singh B, Grand D, Chandan BK, Gupta VN. Effect of Zizyphus sativa leaves on blood glucose levels in normal and alloxan-diabetic rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 1989;27:121–7. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(89)90084-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Roughani M, Amin A. The effect of administration of apium graveolens aqueous extract on the serum levels of glucose and lipids of diabetic rats. Iran J Endocrinol Metabol (IJEM) 2007;9:177–81. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shen Y, Fukushima M, Ito Y, Muraki E, Hosono T, Seki T, et al. Verification of the antidiabetic effects of cinnamon (Cinnamomum zeylanicum) using insulin-uncontrolled type 1 diabetic rats and cultured adipocytes. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2010;74:2418–25. doi: 10.1271/bbb.100453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Naskar S, Mazumder UK, Pramanik G, Gupta M, Kumar RB, Bala A, et al. Evaluation of antihyperglycemic activity of Cocos nucifera Linn. on streptozotocin induced type 2 diabetic rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;138:769–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Roman-Ramos R, Flores-Saenz JL, Alarcon-Aguilar FJ. Anti-hyperglycemic effect of some edible plants. J Ethnopharmacol. 1995;48:25–32. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(95)01279-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Serraclara A, Hawkins F, Pérez C, Domýnguez E, Campillo JE, Torres MD. Hypoglycemic action of an oral fig-leaf decoction in type-I diabetic patients. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1998;39:19–22. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(97)00112-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Özbek H, Öztürk M, Bayram Ý, Uðraþ S, Çitoðlu GS. Hypoglycemic and hepatoprotective effects of foeniculum vulgare miller seed fixed oil extract in mice and rats. East J Med. 2013;8:35–40. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Teymouri M, Montaser S, Ghafarzadegan R, Haji AR. Study of hypoglycemic effect of Juglans regia leaves and its mechanism. J Med Plants. 2010;9:57–65. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chung MJ, Cho SY, Bhuiyan MJ, Kim KH, Lee SJ. Anti-diabetic effects of lemon balm (Melissa officinalis) essential oil on glucose- and lipid-regulating enzymes in type 2 diabetic mice. Br J Nutr. 2010;104:180–8. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510001765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Xue J, Ding W, Liu Y. Anti-diabetic effects of emodin involved in the activation of PPARγ on high-fat diet-fed and low dose of streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Fitoterapia. 2010;81:173–7. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Raju J, Gupta D, Rao AR, Yadava PK, Baquer NZ. Trigonellafoenum graecum (fenugreek) seed powder improves glucose homeostasis in alloxan diabetic rat tissues by reversing the altered glycolytic, gluconeogenic and lipogenic enzymes. Mol Cell Biochem. 2001;224:45–51. doi: 10.1023/a:1011974630828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]