Abstract

On the basis of evidence from clinical trials, contraindications to the use of interferon (INF) are pregnancy, epilepsy and depression. Management of multiple sclerosis during pregnancy is a difficult issue because of pregnancy-related complications and fear of congenital anomalies due to exposure to disease-modifying therapy. In different series, INF therapy was withdrawn before or after variable periods of exposure. This case illustrates a 26-year-old woman diagnosed with relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis who was treated with a weekly regimen of intramuscular INF-β 1a (Avonex). She had received this treatment throughout her pregnancy without any further exacerbations of symptoms or any untoward pregnancy-related complications. In contrast to different series, our patient had the longest exposure to INF-β during pregnancy.

Background

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, progressive immune-driven disease and associated with inflammation, demyelination and axonal loss. From adolescence up to the age of 35 years, the risk of MS increases steadily and thereafter decreases gradually. MS is to be suspected with characteristic clinical pattern, waxing and waning and/or progressive course with or without association of focal neurological deficits. MS can influence a woman's reproductive years. The relapse rate is reduced to 70% during the antenatal period and increases by 70% in the first postpartum trimester.1 Though the exact mechanism is unknown but high levels of oestrogen has been implicated.2 Little guidance is available for women who wish to continue their medications during pregnancy or breastfeeding.

Case presentation

A 26-year-old woman presented with a history of insidious onset gradually progressive numbness sensation of left half of the body including the face for 1.5-month duration. One month later, she developed progressive weakness of the left lower limb leading to mild dragging of foot. There was no cranial nerve involvement including vision. She denied bowel or bladder disturbances and her cognition was normal. She was maintaining independent daily activities. She had similar illness 1 year ago, which improved spontaneously within a period of 3 weeks. Family history was unremarkable. She was investigated with neuroimaging, visual evoked potential test, cerebrospinal fluid oligoclonal band, vasculitic profile and routine blood parameters. Her MRI of the brain with T2-weighted sagittal sequence showed small, discrete, oval, >3 mm demyelinating plaques present in the white matter involving the supratentorial, periventricular, juxtacortical regions and the corpus callosum (figure 1, white arrow). Axial sequence of T2-weighted and T1-weighted image revealed demyelinating plaque and black hole in the aforementioned areas, respectively, (figures 2 and 3, white arrow). She was diagnosed with relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) and treated with intravenous methylprednisolone (1 g for 5 days), followed by oral prednisolone (1 mg/kg body weight) for the next 3 weeks. She responded well to steroids. Subsequently, she was treated with daily subcutaneous injection of glatiramer acetate (20 mg). Owing to intolerance, intramuscular interferon (INF)-β-1a (30 µg weekly) was switched over. She was lost to follow-up for around 1 year. The patient was shifted to some rural area of Uttar Pradesh (a state of North India) during the pregnancy where she could not get any neurology service. She was followed-up by a general practitioner. She continued INF therapy (Avonex) throughout her pregnancy. According to the hospital record and history given by the parents, the baby was born of normal vaginal delivery with episiotomy in a private hospital. There was no pregnancy-related complication. Examination of the newborn by a paediatrician showed normal weight (3.2 kg) at birth without any features of congenital anomaly. She was vaccinated according to the national immunisation programme. At present the baby is of 7-month postnatal age with normal milestones. She can sit independently, uttering monosyllables and achieved normal social milestone.

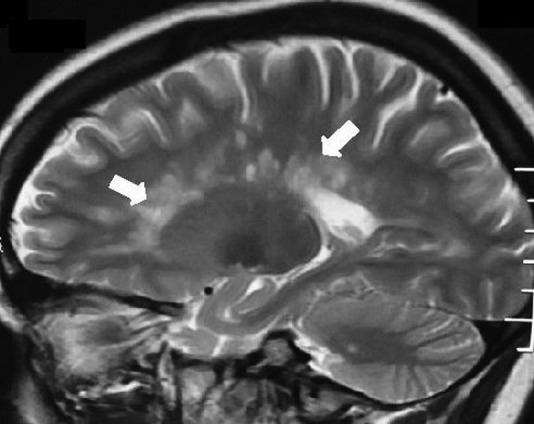

Figure 1.

T2-weighted sagittal sequence of MRI of the brain showing multiple small, discrete, oval, >3 mm demyelinating plaques in the white matter involving the supratentorial and the periventricular regions and the corpus callosum (Dawson's finger; white arrows).

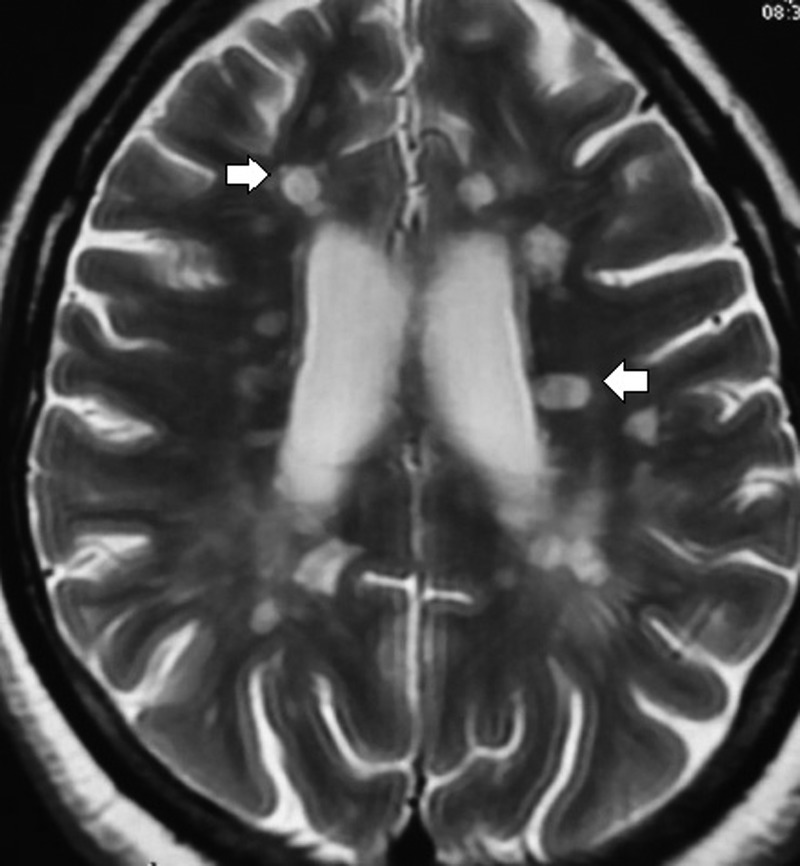

Figure 2.

Axial sequence of T2-weighted image revealed multiple, small discrete, oval, >3 mm hyperintense lesion (demyelinating plaques) in the white matter involving the supratentorial, juxtacortical and periventricular regions and the corpus callosum (white arrows).

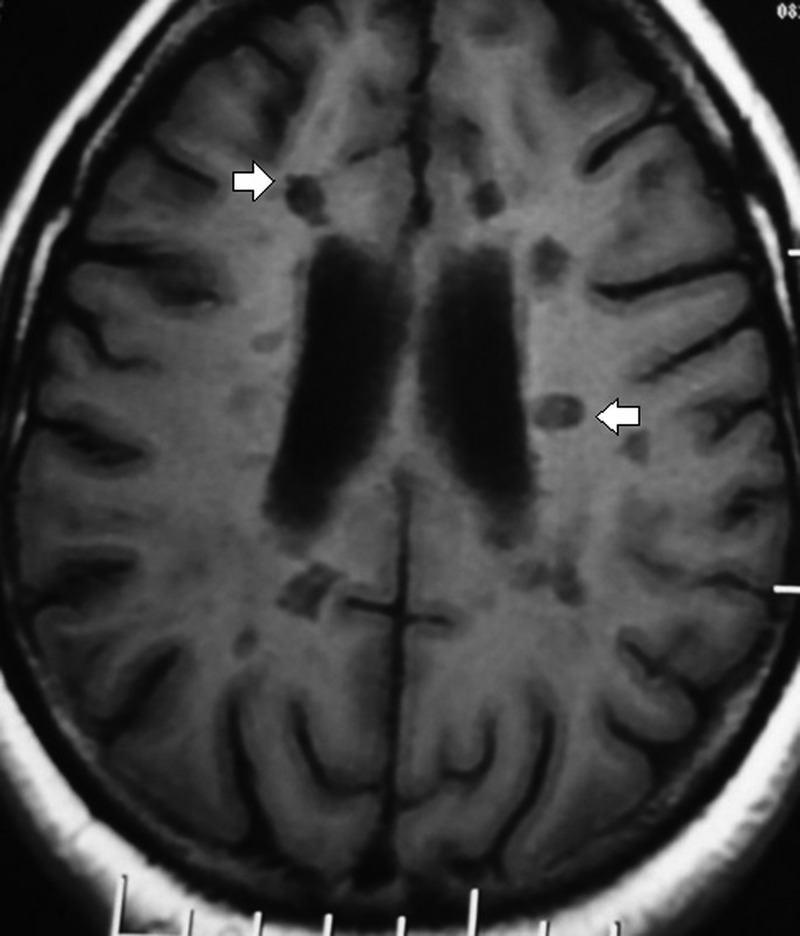

Figure 3.

T1-weighted axial sequence showing the characteristics of hypointense lesion in the periventricular and juxtacortical areas (black hole, white arrows).

Discussion

In the 1990s, US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved INF-β-1a (Avonex), the first disease-modifying therapy (DMT) for RRMS. Subsequently INF-β-1a (Rebif), INF-β-1b (Betaseron), glatiramer acetate, natalizumab and mitoxantrone were recommended, which reduces the relapse rate, time to progress the disability and MRI-related disease burden.3 4 Recently, fingolimod, an oral agent was approved in the USA for the treatment of RRMS.5 6 The newer agent recently approved after phase III clinical trials are BG12, teriflunomide and cladribine. Other immunosuppressive agents such as rituximab, alemtuzumab, daclizumab and cyclophosphamide have shown favourable outcomes in various clinical trials.7

INF-β is teratogenic and abortifacient in primates when used in doses of 2–100 times the corresponding human dose. The FDA includes it as pregnancy category C drug. However, controversies are still ongoing regarding risk and benefit of DMT in pregnancy. According to current concept, DMT should be stopped before conception to avoid pregnancy-related complications and fetal malformations. Based on risk of teratogenicity, the FDA includes INF-β-1a (intramuscular/subcutaneous), INF-β-1b (subcutaneous), natalizumab and fingolimod as class C drugs; glatiramer acetate as class B and mitoxantrone is grouped under class D. Some of the recent approved drugs such as alemtuzumab, daclizumab, rituximab and intravenous immunoglobulin are included as category C drugs; azathioprine, cyclophosphamide and mycophenolate mofetil are category D and methotrexate is category X drug.8 Pregnancy registry study of intramuscular INF-β-1a treatment showed the spontaneous abortion rate in MS was 10.5% as compared with the general population (10–15%) with no increase in the proportion of births with major or serious malformations.8 9 Consistent findings were also reported for subcutaneous INF-β-1a.10 However, several small studies demonstrated that in utero INF-β exposure led to 19.5% spontaneous abortion in MS.10 Boskovic et al11 reported a spontaneous abortion rate of 39% with INF-β exposure versus 5% in healthy non-MS controls. In majority of studies, the in utero exposure of INF therapy was ranging from 1 to 9.1 weeks.12 There are insufficient data regarding the exposure of INF throughout the pregnancy and its outcome. However in our case, the patient was exposed to this therapy throughout pregnancy either due to drug error or due to lack of proper counselling. Though it is difficult to make out any inference regarding safety profile of INF in pregnancy, it needs further studies to explain this unresolved issue.

Learning points.

In contrast to different series, our patient had longest exposure of interferon β-1a during pregnancy without any complications.

The potential risks associated with exposure to disease-modifying therapy (DMT) during pregnancy in patients with multiple sclerosis require further studies.

However discontinuation of DMT before conception is still recommended.

Footnotes

Contributors: AADD participated in the conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and approved the final version published. AKP participated in acquisition of data, drafting the article and final approval of the version to be published.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Vukusic S, Hutchinson M, Hours M, et al. Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis (the PRIMS study): clinical predictors of postpartum relapse. Brain 2004;127:1353–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niino M, Hirotani M, Fukazawa T, et al. Estrogens as potential therapeutic agents in multiple sclerosis. Cent Nerv Syst Agents Med Chem 2009;9:87–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacobs LD, Cookfair DL, Rudick RA, et al. Intramuscular interferon beta-1a for disease progression in relapsing multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 1996;39:285–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.[No authors listed] Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study of interferon beta-1a in relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis. PRISMS (Prevention of Relapses and Disability by Interferon beta-1a Subcutaneously in Multiple Sclerosis) Study Group. Lancet 1998;352:1498–504 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kappos L, Radue EW, O'Connor P, et al. FREEDOMS Study Group . A placebo-controlled trial of oral fingolimod in relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2010;362:387–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen JA, Barkhof F, Comi G, et al. TRANSFORMS Study Group . Oral fingolimod or intramuscular interferon for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2010;362:402–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Río J, Comabella M, Montalban X. Multiple sclerosis: current treatment algorithms. Curr Opin Neurol 2011;24:230–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Houtchens MK, Kolb CM. Multiple sclerosis and pregnancy: therapeutic considerations. J Neurol 2013;260:1202–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ventura SJ, Curtin SC, Abma JC, et al. Estimated pregnancy rates and rates of pregnancy outcomes for the United States, 1990–2008. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2012;60:1–21 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandberg-Wollheim M, Frank D, Goodwin TM, et al. Pregnancy outcomes during treatment with interferon beta-1a in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2005;65:802–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boskovic R, Wide R, Wolpin J, et al. The reproductive effects of beta interferon therapy in pregnancy: a longitudinal cohort. Neurology 2005;65:807–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu E, Wang BW, Guimond C, et al. Disease-modifying drugs for multiple sclerosis in pregnancy: a systematic review. Neurology 2012;79:1130–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]