Introduction

The development of acute myocarditis in the postoperative period of cardiac surgery is a challenge for the doctor who treats this type of patient. In most cases, myocarditis can be only a consequence of procedural-related inflammation. However, differential diagnoses must be observed. Among them, rheumatic fever must be considered as an important mechanism. Although its cardiac manifestation is predominantly related to the involvement of the valvular apparatus, its diagnosis is essentially clinical and it can acutely impair the myocardium. In this context, the occurrence of acute rheumatic myocarditis is rare and its immunosuppressive treatment remains uncertain.

Case Report

The patient was a 23-year-old Caucasian female, born and raised in São Paulo, who came to the emergency department complaining of dyspnea at rest (functional class IV of the New York Heart Association), palpitations, nausea, unmeasured fever and increased abdominal volume for six days. She reported a personal history of rheumatic fever, with two mitral and tricuspid valve plastic surgeries, in 1996 and 2011, and subsequent mitral valve replacement with a biological prosthesis four months before, in 2012. She also had chronic atrial fibrillation on anticoagulation. She denied other symptoms and comorbidities. She was an irregular user of warfarin, furosemide 40 mg / day, spironolactone 50 mg/day, captopril 37.5 mg/day, diltiazem 180 mg/day and sulfadiazine 1 g/day (due to allergy to penicillin).

In February 2012, the patient started to have dyspnea at rest due to symptomatic mitral valve regurgitation and remained hospitalized until heart surgery for mitral valve replacement with a biological prosthesis. At this time she was submitted to preoperative myocardial scintigraphy with gallium-67, which was negative for myocardial inflammatory process. The surgery had no complications and the postoperative transthoracic echocardiography showed left atrium (LA) with 50 mm in diameter, left ventricle (LV) of 56 x 39 mm, ejection fraction (EF) of 57% and unchanged mitral bioprosthesis structure. She was discharged receiving the medications listed above.

On physical examination, the patient was in good general health status, afebrile, tachycardic (heart rate = 180 beats per minute), blood pressure of 90 x 60 mmHg, tachydyspneic (respiratory rate = 25 breaths per minute), arterial oxygen saturation in ambient air was 93% and she had intercostal retraction. Apex beat was visible and palpable in the fifth intercostal space on the left midclavicular line; presence of arrhythmic heart sounds with a loud B2 sound, holosystolic mitral regurgitation murmur of 2 +/6+ intensity, breath sounds present with fine rales in the lung bases bilaterally, hardened liver that was palpable about 7 cm from the right costal margin and bilateral and symmetric 2+/ 4+ lower limb edema.

At this time, a diagnosis of heart failure due to probable infective endocarditis or active rheumatic fever was attained, considering the presence of fever and clinical signs of pulmonary and systemic congestion, after which three pairs of blood cultures were collected, an echocardiogram was requested and empirical antibiotic therapy with intravenous ceftriaxone and oxacillin was initiated.

The electrocardiogram initially showed atrial fibrillation with high ventricular response. Chest X-ray showed interstitial infiltrates in the lower two-thirds of both hemithoraxes, as well as cardiomegaly.

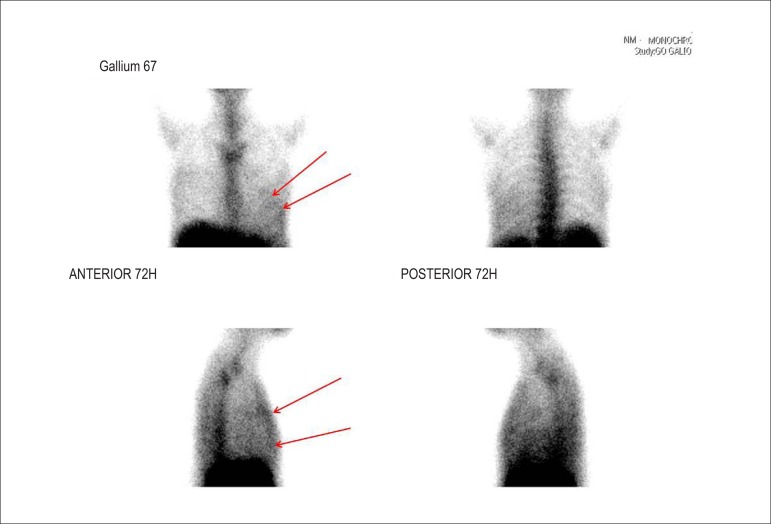

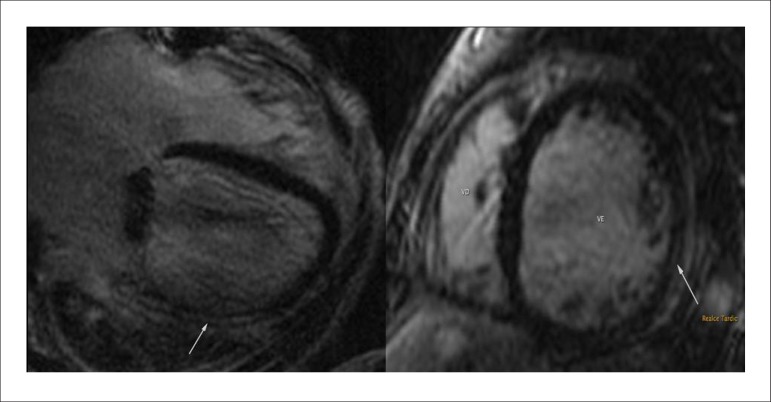

Transesophageal echocardiography showed LA = 56 mm, LV = 71 x 62 mm, EF 20% with diffuse hypokinesis of LV and bioprosthetic mitral valve with no signs dysfunction or evidence of vegetation. Blood cultures were negative. At this time, we chose to maintain adequate control of heart rate and administration of intravenous furosemide. To confirm the rheumatic myocarditis, myocardial scintigraphy with gallium-67 was requested, which showed positive for ongoing inflammatory process (Figure 1). Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging was performed, which showed significant diffuse biventricular dysfunction and presence of myocardial inflammatory process (Figure 2). Laboratory assessment showed C-reactive protein of 89.3 mg/L, brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) of 2,553 pg/mL, ASLO = 693 IU/mL, erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 50 mm and alpha-1-acid glycoprotein = 136 mg/dL.

Figure 1.

Gallium-67 myocardial scintigraphy showing inflammatory activity compatible with myocarditis (red arrows).

Figure 2.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showing the presence of intramyocardial late enhancement in the left ventricle (white arrows).

Due to the diagnosis of myocarditis, Prednisone 2 mg/kg/day was started. Two hypotheses were then considered: postoperative myocarditis (procedure-related) and acute attack of rheumatic fever. The patient showed significant symptom improvement and was discharged on the 14th day after admission using prednisone 1 mg/kg/day, captopril, furosemide, spironolactone, carvedilol, digoxin and warfarin. In addition, she was referred to immunology for desensitization to penicillin and started to receive a dose of benzathine penicillin of 1.200.000 IU every 15 days without complications.

Discussion

The occurrence of postoperative myocarditis is underdiagnosed. Most of the time, it is not associated with ventricular dysfunction. It usually occurs on the days following the procedure and, in rare cases, remains for a long time. The diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever attack was established by the Jones criteria of the American Heart Association. The presence of myocarditis associated with elevation in inflammatory markers, fever, previous valvular sequelae and high ASLO levels are enough for the diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever attack, which makes this the main hypothesis in the case1-3.

In literature, and in classic rheumatic fever, the three leaflets (pericardium, myocardium and endocardium) are simultaneously affected, although in unequal proportions, with usually subclinical myocardial lesion only. In most cases in which there is a picture of heart failure during an acute attack of rheumatic fever, it is due to a mechanical cause, due to valvular dysfunction, and clinically manifest myocarditis is uncommon4. In this case, the patient met the criteria for acute rheumatic fever; however, the echocardiogram showed no biological valve prosthesis dysfunction and showed significant biventricular myocardial dysfunction. Myocardial scintigraphy and cardiac MRI confirmed the diagnosis, by demonstrating the presence of myocardial inflammation.

In the diagnosis of myocarditis, clinical, electrocardiographic, laboratory and radiographic findings have low sensitivity and specificity. Troponin I is increased in only 34% of cases of myocarditis. Sinus tachycardia, changes in the ST segment or T wave, as well as bundle branch blocks, can be found, but they are not specific and infrequent5.

The gold standard for the diagnosis of myocarditis would be the endomyocardial biopsy of the right ventricle, but its sensitivity is questionable due to its focal nature, in addition to being an invasive test. Scintigraphy and MRI have emerged as important tools in the diagnosis of myocarditis. Recent studies have demonstrated the usefulness of scintigraphy, not only in the diagnosis but also the prognosis of myocarditis, with a sensitivity of 91-100% and negative predictive value ranging from 93-100%6.

Sun et al7 found a good association between the degree of perfusion reduction at the scintigraphy and elevated markers of myocardial necrosis and ST-T changes related to myocarditis. Regarding the role of magnetic resonance imaging, Abdel Aty et al stuyding 25 patients with suspected myocarditis and 23 controls, found a sensitivity of 84% and specificity of 74%5,8,9. However, specifically in rheumatic myocarditis, the literature is scarce and there is no clear radiological evidence of this event, as shown in this case. This fact makes this report unique due to image capture in cardiac MRI, demonstrating myocardial inflammation during a probable attack of acute rheumatic fever.

As for treatment, most patients with acute myocarditis respond very well to the general measures used in acute heart failure, such as neurohumoral blocking5. In acute attacks of rheumatic fever with myocardial impairment, the dose used in immunosuppression and how it should be performed are yet to be determined. Due to the rarity of cases, the best therapeutic method is based on case reports, only. In our case there was clinical improvement after the use of prednisone at a dose of 2 mg/kg/day for 14 days, which was reduced to 1 mg/kg/day thereafter. The treatment time is also unknown and must be based on ventricular function recovery associated with the reduction in inflammatory markers10.

Despite all the advances in Medicine, the higher cost-effectiveness intervention in rheumatic fever is still secondary prevention, preventing acute attacks and, thus, early and more severe valve sequelae. Intramuscular injections of benzyl penicillin every three weeks were able to reduce hospital admissions and are preferred to the use of oral medication, due to its proven efficacy3, which justified the conduct of attempting desensitization to penicillin in this case.

Furthermore, it is noteworthy, based on this case report, the importance of maintaining secondary prophylaxis even after the occurrence of valve replacement, as the acute attack can manifest in other organs or in the heart itself, but in another segment.

Conclusion

The demonstration of probable rheumatic myocarditis in cardiac MRI makes this case unique. The presence of an acute attack of rheumatic fever should always be considered in young patients with a previous diagnosis and who are not receiving adequate secondary prophylaxis. Its treatment is still uncertain, but it is based on immunosuppression and recurrence prevention, maintaining the prophylaxis even in patients who have already undergone valve replacement.

Footnotes

Potential Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Sources of Funding

There were no external funding sources for this study.

Study Association

This study is not associated with any post-graduation program.

Author contributions

Conception and design of the research: Xavier Jr. JL, Soeiro AM, Lopes ASSA, Oliveira Jr. MT. Acquisition of data: Xavier Jr. JL, Soeiro AM, Lopes ASSA, Oliveira Jr. MT. Analysis and interpretation of the data: Xavier Jr. JL, Soeiro AM, Serrano Jr. CV. Writing of the manuscript: Xavier Jr. JL, Soeiro AM. Critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content: Soeiro AM, Lopes ASSA, Spina GS, Serrano Jr. CV, Oliveira Jr. MT.

References

- 1.Azevedo PM, Pereira RR, Guilherme L. Understanding rheumatic fever. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32(5):1113–1120. doi: 10.1007/s00296-011-2152-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cunningham MW. Streptococcus and rheumatic fever. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2012;24(4):408–416. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32835461d3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization (WHO) Rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease: report of a WHO expert consultation on rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. Geneva: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamblock J, Payot L, Iung B, Costes P, Gillet T, Le Goanvic C, et al. Does rheumatic myocarditis really exists? Systematic study with echocardiography and cardiac troponin I blood levels. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:855–862. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(02)00825-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sagar S, Liu PP, Cooper LT., Jr Myocarditis. Lancet. 2012;379(9817):738–747. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60648-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Javadi H, Jallalat S, Pourbehi G, Semnani S, Mogharrabi M, Nabipour I, et al. The role of gated myocardial perfusion scintigraphy (GMPS) in myocarditis: a case report and review of the literature. Nucl Med Med RevCent East Eur. 2011;14(2):112–115. doi: 10.5603/nmr.2011.00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun Y, Ma P, Bax JJ, Blom N, Yu Y, Wang Y, et al. 99mTc-MIBI myocardial perfusion imaging in myocarditis. Nucl Med Commun. 2003;24(7):779–783. doi: 10.1097/01.mnm.0000080254.50447.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abdel-Aty H, Boye P, Zagrosek A, Wassmuth R, Kumar A, Messroghli D, et al. Diagnostic performance of cardiovascular magnetic resonance in patients with suspected acute myocarditis: comparison of different approaches. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(11):1815–1822. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.11.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu PP, Yan AT. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance for the diagnosis of acute myocarditis: prospects for detecting myocardial inflammation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(11):1823–1825. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mason JW, O'Connell JB, Herskowitz A, Rose NR, McManus BM, Billingham ME, et al. A clinical trial of immunosuppressive therapy for myocarditis: The Myocarditis Treatment Trial Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(5):269–275. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199508033330501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]